History of the Irish language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the

It is believed that Irish remained the majority tongue as late as 1800 but became a minority language during the 19th century. It is an important part of

It is believed that Irish remained the majority tongue as late as 1800 but became a minority language during the 19th century. It is an important part of

/ref> and in the absence of an authorised Irish Catholic bible (An Biobla Naofa) before 1981, resulting in instruction primarily in English, or Latin. The National Schools run by the

Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

begins with the period from the arrival of speakers of Celtic languages

The Celtic languages (usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward ...

in Ireland to Ireland's earliest known form of Irish, Primitive Irish

Primitive Irish or Archaic Irish ( ga, Gaeilge Ársa), also called Proto-Goidelic, is the oldest known form of the Goidelic languages. It is known only from fragments, mostly personal names, inscribed on stone in the ogham alphabet in Ireland ...

, which is found in Ogham

Ogham ( Modern Irish: ; mga, ogum, ogom, later mga, ogam, label=none ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish langu ...

inscriptions dating from the 3rd or 4th century AD. After the conversion to Christianity in the 5th century, Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writte ...

begins to appear as glosses and other marginalia

Marginalia (or apostils) are marks made in the margins of a book or other document. They may be scribbles, comments, glosses (annotations), critiques, doodles, drolleries, or illuminations.

Biblical manuscripts

Biblical manuscripts h ...

in manuscripts

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

written in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, beginning in the 6th century. It evolved in the 10th century to Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engl ...

. Early Modern Irish

Early Modern Irish ( ga, Gaeilge Chlasaiceach, , Classical Irish) represented a transition between Middle Irish and Modern Irish. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century.

External ...

represented a transition between Middle and Modern Irish. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic or Classical Irish () was a shared literary form of Gaelic that was in use by poets in Scotland and Ireland from the 13th century to the 18th century.

Although the first written signs of Scottish Gaelic having diverged from Ir ...

, was used by writers in both Ireland and Scotland until the 18th century, in the course of which slowly but surely writers began writing in the vernacular dialects, Ulster Irish

Ulster Irish ( ga, Gaeilig Uladh, IPA=, IPA ga=ˈɡeːlʲɪc ˌʊlˠuː) is the variety of Irish spoken in the province of Ulster. It "occupies a central position in the Gaelic world made up of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man". Ulster Ir ...

, Connacht Irish

Connacht Irish () is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Connacht. Gaeltacht regions in Connacht are found in Counties Mayo (notably Tourmakeady, Achill Island and Erris) and Galway (notably in parts of Connemara and o ...

, Munster Irish

Munster Irish () is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Munster. Gaeltacht regions in Munster are found in the Gaeltachtaí of the Dingle Peninsula in west County Kerry, in the Iveragh Peninsula in south Kerry, in Cap ...

and Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

. As the number of hereditary poets and scribes dwindled under British rule in the early 19th century, Irish became a mostly spoken tongue with little written literature appearing in the language until the Gaelic Revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

of the late 19th century. The number of speakers was also declining in this period with monoglot and bilingual speakers of Irish increasingly adopting only English: while Irish never died out, by the time of the Revival it was largely confined to the less Anglicised regions of the island, which were often also the more rural and remote areas. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Irish has continued to survive in Gaeltacht

( , , ) are the districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The ''Gaeltacht'' districts were first officially reco ...

regions and among a minority in other regions. It has once again come to be considered an important part of the island's culture and heritage, with efforts being made to preserve and promote it.

Early history

Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, D ...

may have arrived in Ireland between 2,400 BC and 2,000 BC with the spread of the Bell Beaker

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell beaker drinking vessel used at the very beginning of the European Bronze Age. Arising from ar ...

culture when around 90% of the contemporary Neolithic population was replaced by lineages related to the Yamnaya culture

The Yamnaya culture or the Yamna culture (russian: Ямная культура, ua, Ямна культура lit. 'culture of pits'), also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, was a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archa ...

from the Pontic steppe. The Beaker culture has been suggested as a candidate for an early Indo-European culture

Proto-Indo-European society is the reconstructed culture of Proto-Indo-Europeans, the ancient speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, ancestor of all modern Indo-European languages.

Scientific approaches

Many of the modern ideas in this ...

, specifically, as ancestral to proto-Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method. Proto-Celt ...

."Almagro-Gorbea – La lengua de los Celtas y otros pueblos indoeuropeos de la península ibérica", 2001 p.95. In Almagro-Gorbea, M., Mariné, M. and Álvarez-Sanchís, J. R. (eds) ''Celtas y Vettones'', pp. 115–121. Ávila: Diputación Provincial de Ávila. Mallory proposed in 2013 that the Beaker culture was associated with a European branch of Indo-European dialects, termed "North-west Indo-European", ancestral to not only Celtic but also Italic, Germanic, and Balto-Slavic.J.P. Mallory, 'The Indo-Europeanization of Atlantic Europe', in ''Celtic From the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo–European in Atlantic Europe'', eds J. T. Koch and B. Cunliffe (Oxford, 2013), p.17–40

Primitive Irish

The earliest written form of the Irish language is known to linguists asPrimitive Irish

Primitive Irish or Archaic Irish ( ga, Gaeilge Ársa), also called Proto-Goidelic, is the oldest known form of the Goidelic languages. It is known only from fragments, mostly personal names, inscribed on stone in the ogham alphabet in Ireland ...

. Primitive Irish is known only from fragments, mostly personal names, inscribed on stone in the Ogham

Ogham ( Modern Irish: ; mga, ogum, ogom, later mga, ogam, label=none ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish langu ...

alphabet. The earliest of such inscriptions probably date from the 3rd or 4th century. Ogham inscriptions are found primarily in the south of Ireland as well as in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

, Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

, where it was brought by settlers from Ireland to sub-Roman Britain

Sub-Roman Britain is the period of late antiquity in Great Britain between the end of Roman rule and the Anglo-Saxon settlement. The term was originally used to describe archaeological remains found in 5th- and 6th-century AD sites that hin ...

, and in the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

.

Old Irish

Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writte ...

first appears in the margins of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

s as early as the 6th century. A large number of early Irish literary texts, though recorded in manuscripts of the Middle Irish period (such as '' Lebor na hUidre'' and the Book of Leinster

The Book of Leinster ( mga, Lebor Laignech , LL) is a medieval Irish manuscript compiled c. 1160 and now kept in Trinity College, Dublin, under the shelfmark MS H 2.18 (cat. 1339). It was formerly known as the ''Lebor na Nuachongbála'' "Book ...

), are essentially Old Irish in character.

Middle Irish

Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engl ...

is the form of Irish used from the 10th to 12th centuries; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

and early Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old Englis ...

. It is the language of a large amount of literature, including the entire Ulster Cycle

The Ulster Cycle ( ga, an Rúraíocht), formerly known as the Red Branch Cycle, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the Ulaid. It is set far in the past, in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly coun ...

.

Early Modern Irish

Early Modern Irish represents a transition betweenMiddle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engl ...

and Modern Irish. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic or Classical Irish () was a shared literary form of Gaelic that was in use by poets in Scotland and Ireland from the 13th century to the 18th century.

Although the first written signs of Scottish Gaelic having diverged from Ir ...

, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century. The grammar of Early Modern Irish is laid out in a series of grammatical tracts written by native speakers and intended to teach the most cultivated form of the language to student bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise ...

s, lawyers, doctors, administrators, monks, and so on in Ireland and Scotland.

Nineteenth and twentieth centuries

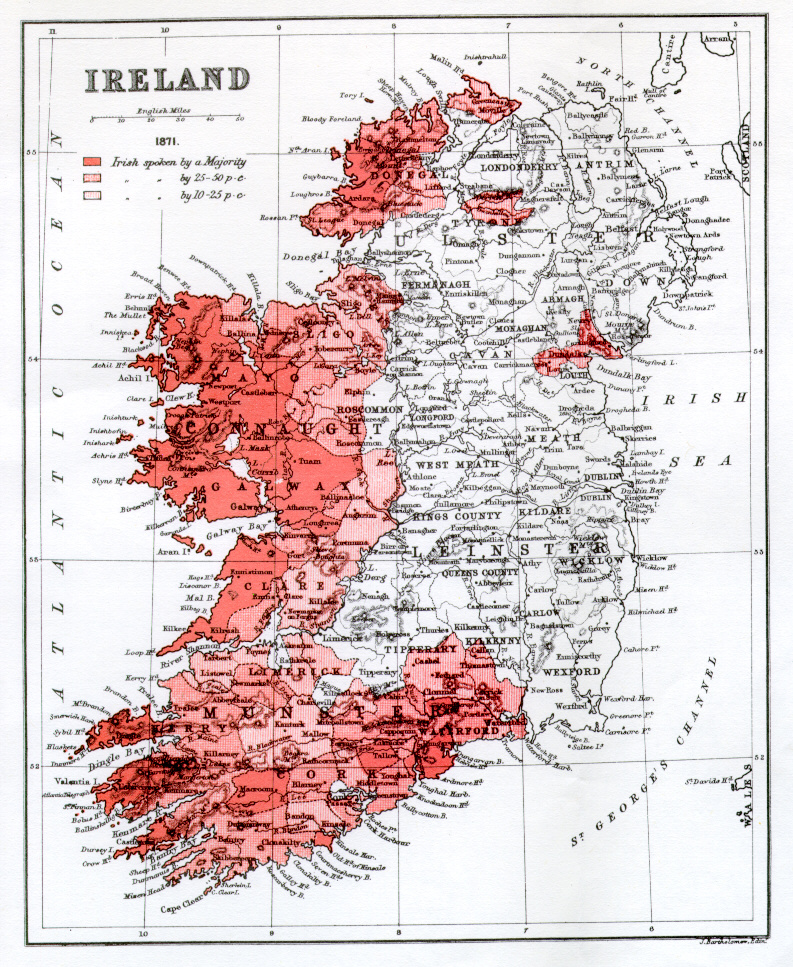

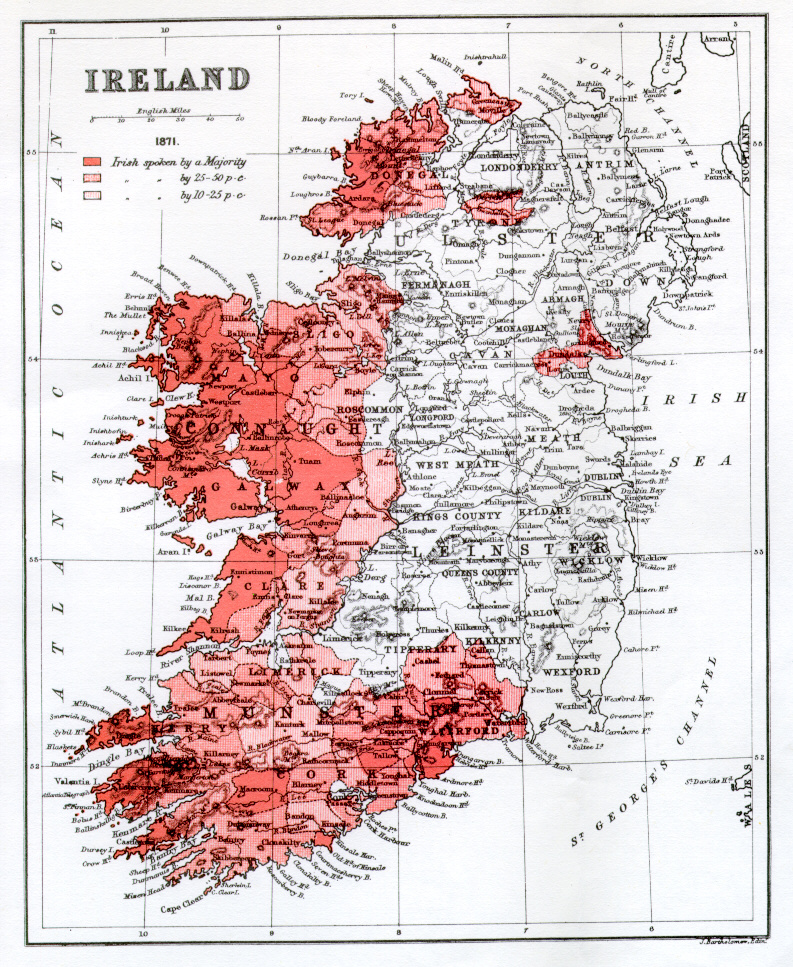

It is believed that Irish remained the majority tongue as late as 1800 but became a minority language during the 19th century. It is an important part of

It is believed that Irish remained the majority tongue as late as 1800 but became a minority language during the 19th century. It is an important part of Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of c ...

identity, marking a cultural distance between Irish people and the English.

A combination of the introduction of state funded, though predominantly denominationally Church delivered, primary education (the ' National Schools'), from 1831, in which Irish was omitted from the curriculum till 1878, and only then added as a curiosity, to be learnt after English, Latin, Greek and French,Erick Falc’Her-Poyroux. ’The Great Famine in Ireland: a Linguistic and Cultural Disruption. Yann Bévant. La Grande Famine en Irlande 1845-1850, PUR, 2014. halshs-01147770/ref> and in the absence of an authorised Irish Catholic bible (An Biobla Naofa) before 1981, resulting in instruction primarily in English, or Latin. The National Schools run by the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

discouraged its use until about 1890.

The Great Famine () hit a disproportionately high number of Irish speakers (who lived in the poorer areas heavily hit by famine deaths and emigration), translated into its rapid decline.

Irish political leaders, such as Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

(, himself a native speaker), were also critical of the language, seeing it as 'backward', with English the language of the future.

Add economic opportunities for most Irish people arose at that time within the Industrialising United States of America, and the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, which both used English. Contemporary reports spoke of Irish-speaking parents actively discouraging their children from speaking the language, and encouraging the use of English instead. This practice continued long after independence, as the stigma of speaking Irish remained very strong.

It has been argued, however, that the sheer number of Irish speakers in the nineteenth century and their social diversity meant that both religious and secular authorities had to engage with them. This meant that Irish, rather than being marginalised, was an essential element in the modernization of Ireland, especially before the Great Famine of the 1840s. Irish speakers insisted on using the language in the law courts (even when they knew English), and it was common to employ interpreters. It was not unusual for magistrates, lawyers and jurors to employ their own knowledge of Irish. Fluency in Irish was often necessary in commercial matters. Political candidates and political leaders found the language invaluable. Irish was an integral part of the "devotional revolution" which marked the standardisation of Catholic religious practice, and the Catholic bishops (often partly blamed for the decline of the language) went to great lengths to ensure there was an adequate supply of Irish-speaking priests. Irish was widely and unofficially used as a language of instruction both in the local pay-schools (often called hedge schools) and in the National Schools. Down to the 1840s and even afterwards, Irish speakers could be found in all occupations and professions.

The initial moves to reverse the decline of the language were championed by Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

Protestants

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, such as the linguist and clergyman William Neilson, towards the end of the 18th century, and Samuel Ferguson; the major push occurred with the foundation by Douglas Hyde

Douglas Ross Hyde ( ga, Dubhghlas de hÍde; 17 January 1860 – 12 July 1949), known as (), was an Irish academic, linguist, scholar of the Irish language, politician and diplomat who served as the first President of Ireland from June 1938 t ...

, the son of a Church of Ireland rector, of the Gaelic League

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it emer ...

(known in Irish as ) in 1893, which was a factor in launching the Irish Revival movement. The Gaelic league managed to reach 50,000 members by 1904 and also successfully pressured the government into allowing the Irish language as a language of instruction the same year. Leading supporters of Conradh included Pádraig Pearse

Patrick Henry Pearse (also known as Pádraig or Pádraic Pearse; ga, Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish teacher, barrister, poet, writer, nationalist, republican political activist and revolutionary who ...

and Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of govern ...

. The revival of interest in the language coincided with other cultural revivals, such as the foundation of the Gaelic Athletic Association

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA; ga, Cumann Lúthchleas Gael ; CLG) is an Irish international amateur sporting and cultural organisation, focused primarily on promoting indigenous Gaelic games and pastimes, which include the traditional ...

and the growth in the performance of plays about Ireland in English, by playwrights including W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, J. M. Synge

Edmund John Millington Synge (; 16 April 1871 – 24 March 1909) was an Irish playwright, poet, writer, collector of folklore, and a key figure in the Irish Literary Revival. His best known play ''The Playboy of the Western World'' was poorly r ...

, Seán O'Casey

Seán O'Casey ( ga, Seán Ó Cathasaigh ; born John Casey; 30 March 1880 – 18 September 1964) was an Irish dramatist and memoirist. A committed socialist, he was the first Irish playwright of note to write about the Dublin working classes.

...

and Lady Gregory

Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory (''née'' Persse; 15 March 1852 – 22 May 1932) was an Irish dramatist, folklorist and theatre manager. With William Butler Yeats and Edward Martyn, she co-founded the Irish Literary Theatre and the Abbey Theatre, ...

, with their launch of the Abbey Theatre

The Abbey Theatre ( ga, Amharclann na Mainistreach), also known as the National Theatre of Ireland ( ga, Amharclann Náisiúnta na hÉireann), in Dublin, Ireland, is one of the country's leading cultural institutions. First opening to the p ...

. By 1901 only approximately 641,000 people spoke Irish with only just 20,953 of those speakers being monolingual Irish speakers; how many had emigrated is unknown, but it is probably safe to say that a larger number of speakers lived elsewhere This change in demographics can be attributed to the Great Famine as well as the increasing social pressure to speak English.

Even though the Abbey Theatre playwrights wrote in English (and indeed some disliked Irish) the Irish language affected them, as it did all Irish English speakers. The version of English spoken in Ireland, known as Hiberno-English

Hiberno-English (from Latin '' Hibernia'': "Ireland"), and in ga, Béarla na hÉireann. or Irish English, also formerly Anglo-Irish, is the set of English dialects native to the island of Ireland (including both the Republic of Ireland ...

bears similarities in some grammatical idioms with Irish. Writers who have used Hiberno-English include J.M. Synge, Yeats, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

and more recently in the writings of Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.

, Paul Durcan, and Dermot Bolger

Dermot Bolger (born 1959) is an Irish novelist, playwright, poet and editor from Dublin, Ireland. Born in the Finglas suburb of Dublin in 1959, his older sister is the writer June Considine. Bolger's novels include ''Night Shift'' (1982), '' ...

.

This national cultural revival of the late 19th century and early 20th century matched the growing Irish radicalism in Irish politics. Many of those, such as Pearse, de Valera, W. T. Cosgrave

William Thomas Cosgrave (5 June 1880 – 16 November 1965) was an Irish Fine Gael politician who served as the president of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1932, leader of the Opposition in both the Free State and Ir ...

(Liam Mac Cosguir) and Ernest Blythe

Ernest Blythe (; 13 April 1889 – 23 February 1975) was an Irish journalist, managing director of the Abbey Theatre, and politician who served as Minister for Finance from 1923 to 1932, Minister for Posts and Telegraphs and Vice-President of ...

(Earnán de Blaghd), who fought to achieve Irish independence and came to govern the independent Irish Free State, first became politically aware through Conradh na Gaeilge. Douglas Hyde had mentioned the necessity of "de-anglicizing" Ireland, as a cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.T ...

goal that was not overtly political. Hyde resigned from its presidency in 1915 in protest when the movement voted to affiliate with the separatist cause; it had been infiltrated by members of the secretive Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

, and had changed from being a purely cultural group to one with radical nationalist aims.

A Church of Ireland campaign to promote worship and religion in Irish was started in 1914 with the founding of Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise (the Irish Guild of the Church). The Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

Church also replaced its liturgies in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

with Irish and English following the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions), each lasting between 8 and ...

in the 1960s, and its first Bible was published in 1981. The hit song Theme from Harry's Game

"Theme from ''Harry's Game''" is a 1982 song by Clannad commissioned as the theme for '' Harry's Game'', a Yorkshire Television miniseries adapted from a 1975 novel set in The Troubles in Northern Ireland. It was released as a single in Octob ...

by County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ga, Contae Dhún na nGall) is a county of Ireland in the province of Ulster and in the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Donegal in the south of the county. It has also been known as County Tyrcon ...

music group Clannad

Clannad () is an Irish band formed in 1970 in Gweedore, County Donegal by siblings Ciarán, Pól, and Moya Brennan and their twin uncles Noel and Pádraig Duggan. They have adopted various musical styles throughout their history, including ...

, became the first song to appear on Britain's ''Top of the Pops

''Top of the Pops'' (''TOTP'') is a British Record chart, music chart television programme, made by the BBC and originally broadcast weekly between 1January 1964 and 30 July 2006. The programme was the world's longest-running weekly music show ...

'' with Irish lyrics in 1982.

It has been estimated that there were around 800,000 monoglot Irish speakers in 1800, which dropped to 320,000 by the end of the famine

The Famine was an American death metal band formed in Arlington, Texas in 2007. They were signed to Solid State Records.

History

Formation and three-song EP

The band initially formed with three of the original members of Embodyment in ...

, and under 17,000 by 1911. Seán Ó hEinirí

Seán Ó hEinirí (Seán Ó hInnéirghe, 26 March 1915 – 26 July 1998), known in English as John Henry, was an Irish seanchaí and a native of Cill Ghallagáin, County Mayo. He is known for his storytelling. Notably, Seán was a monoling ...

of Cill Ghallagáin

Cill Ghallagáin (anglicised as Kilgalligan) is a small Gaeltacht coastal townland and village in the northwest corner of Kilcommon Parish, County Mayo, Republic of Ireland, an area of in size. Off the northern coast of this townland li ...

, County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the yew trees") is a county in Ireland. In the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, now generally known as Mayo Abbey. Mayo County Counci ...

, who died in 1998, was almost certainly the last monolingual

Monoglottism (Greek μόνος ''monos'', "alone, solitary", + γλῶττα , "tongue, language") or, more commonly, monolingualism or unilingualism, is the condition of being able to speak only a single language, as opposed to multilingualism. ...

Irish speaker.

Twenty-first century

In July 2003, the Official Languages Act was signed, declaring Irish anofficial language

An official language is a language given supreme status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically the term "official language" does not refer to the language used by a people or country, but by its government (e.g. judiciary, ...

, requiring public service providers to make services available in the language, which affected advertising, signage, announcements, public reports, and more.

In 2007, Irish became an official working language of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

.

Independent Ireland and the language

The independent Irish state was established in 1922 (Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

1922–37; Ireland (Éire) from 1937, also described since 1949 as the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. ...

). Although some Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

leaders had been committed language enthusiasts, the new state continued to use English as the language of administration, even in areas where over 80% of the population spoke Irish. There was some initial enthusiasm – a Dáil decree of March 1922 required that the Irish versions of names on all birth, death and marriage certificates would have to be used from July 1923. While the decree was passed unanimously, it was never implemented, probably because of the outbreak of the Irish civil war

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

. Those areas of the state where Irish had remained widespread were officially designated as Gaeltachtaí, where the language would initially be preserved and then ideally be expanded from across the whole island.

The government refused to implement the 1926 recommendations of the Gaeltacht Commission, which included restoring Irish as the language of administration in such areas. As the role of the state grew, it therefore exerted tremendous pressure on Irish speakers to use English. This was only partly offset by measures which were supposed to support the Irish language. For instance, the state was by far the largest employer. A qualification in Irish was required to apply for state jobs. However, this did not require a high level of fluency, and few public employees were ever required to use Irish in the course of their work. On the other hand, state employees had to have perfect command of English and had to use it constantly. Because most public employees had a poor command of Irish, it was impossible to deal with them in Irish. If an Irish speaker wanted to apply for a grant, obtain electricity, or complain about being over-taxed, they would typically have had to do so in English. As late as 1986, a Bord na Gaeilge report noted "...the administrative agencies of the state have been among the strongest forces for Anglicisation in Gaeltacht areas".

The new state also attempted to promote Irish through the school system. Some politicians claimed that the state would become predominantly Irish-speaking within a generation. In 1928, Irish was made a compulsory subject for the Intermediate Certificate exams, and for the Leaving Certificate

A secondary school leaving qualification is a document signifying that the holder has fulfilled any secondary education requirements of their locality, often including the passage of a final qualification examination.

For each leaving certifica ...

in 1934. However, it is generally agreed that the compulsory policy was clumsily implemented. The principal ideologue was Professor Timothy Corcoran of University College Dublin

University College Dublin (commonly referred to as UCD) ( ga, Coláiste na hOllscoile, Baile Átha Cliath) is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a member institution of the National University of Ireland. With 33,284 student ...

, who "did not trouble to acquire the language himself". From the mid-1940s onward the policy of teaching all subjects to English-speaking children through Irish was abandoned. In the following decades, support for the language was progressively reduced. Irish has undergone spelling and script reforms since the 1940s to simplify the language. The orthographic system was changed and the traditional Irish script fell into disuse. These reforms were met with a negative reaction and many people argued that these changes marked a loss of the Irish identity in order to appease language learners. Another reason for this backlash was that the reforms forced the current Irish speakers to relearn how to read Irish in order to adapt to the new system.

It is disputed to what extent such professed language revival

Language revitalization, also referred to as language revival or reversing language shift, is an attempt to halt or reverse the decline of a language or to revive an extinct one. Those involved can include linguists, cultural or community groups, o ...

ists as de Valera genuinely tried to Gaelicise political life. Even in the first Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland rea ...

, few speeches were delivered in Irish, with the exception of formal proceedings. In the 1950s, An Caighdeán Oifigiúil

(, "The Official Standard"), often shortened to , is the variety of the Irish language that is used as the standard or state norm for the spelling and grammar of the language and is used in official publications and taught in most schools in th ...

("The Official Standard") was introduced to simplify spellings and allow easier communication by different dialect speakers. By 1965 speakers in the Dáil regretted that those taught Irish in the traditional Irish script (the ''Cló Gaedhealach'') over the previous decades were not helped by the recent change to the Latin script, the ''Cló Romhánach''. An ad-hoc " Language Freedom Movement" that was opposed to the compulsory teaching of Irish was started in 1966, but it had largely faded away within a decade.

Overall, the percentage of people speaking Irish as a first language has decreased since independence, while the number of second-language speakers has increased.

There have been some modern success stories in language preservation and promotion such as Gaelscoileanna the education movement, Official Languages Act 2003, TG4, RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta and Foinse.

In 2005, Enda Kenny

Enda Kenny (born 24 April 1951) is an Irish former Fine Gael politician who served as Taoiseach from 2011 to 2017, Leader of Fine Gael from 2002 to 2017, Minister for Defence from May to July 2014 and 2016 to 2017, Leader of the Opposition fro ...

, formerly an Irish teacher, called for compulsory Irish to end at the Junior Certificate

Junior Cycle ( ga, An tSraith Shóisearach ) is the first stage of the education programme for post-primary education within the Republic of Ireland. It is overseen by the State Examinations Commission of the Department of Education, the Stat ...

level, and for the language to be an optional subject for Leaving Certificate

A secondary school leaving qualification is a document signifying that the holder has fulfilled any secondary education requirements of their locality, often including the passage of a final qualification examination.

For each leaving certifica ...

students. This provoked considerable comment, and Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legislature) and the of ...

Bertie Ahern

Bartholomew Patrick "Bertie" Ahern (born 12 September 1951) is an Irish former Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1997 to 2008, Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1994 to 2008, Leader of the Opposition from 1994 to 1997, Tánaiste a ...

argued that it should remain compulsory.

Today, estimates of fully native speakers range from 40,000 to 80,000 people. In the republic, there are just over 72,000 people who use Irish as a daily language outside education, as well as a larger minority of the population who are fluent but do not use it on a daily basis. (While census figures indicate that 1.66 million people in the republic have some knowledge of the language, a significant percentage of these know only a little.) Smaller numbers of Irish speakers exist in Britain, Canada (particularly in Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

), the United States of America and other countries.

The most significant development in recent decades has been a rise in the number of urban Irish speakers. This community, which has been described as well-educated and mostly upper-class, is largely based on an independent school system (called gaelscoil

A Gaelscoil (; plural: ''Gaelscoileanna'') is an Irish language-medium school in Ireland: the term refers especially to Irish-medium schools outside the Irish-speaking regions or Gaeltacht. Over 50,000 students attend Gaelscoileanna at primary an ...

eanna at primary level) which teaches entirely through Irish. These schools perform exceptionally well academically. An analysis of "feeder" schools (which supply students to tertiary level institutions) has shown that 22% of the Irish-medium schools sent all their students on to tertiary level, compared to 7% of English-medium schools. Given the rapid decline in the number of traditional speakers in the Gaeltacht

( , , ) are the districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The ''Gaeltacht'' districts were first officially reco ...

it seems likely that the future of the language is in urban areas. It has been suggested that fluency in Irish, with its social and occupational advantages, may now be the mark of an urban elite. Others have argued, on the contrary, that the advantage lies with a middle-class elite which is simply more likely to speak Irish. It has been estimated that the active Irish-language scene (mostly urban) may comprise as much as 10 per cent of Ireland's population.

Northern Ireland and the language

Since thepartition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. ...

, the language communities in the Republic and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

have taken radically different trajectories. While Irish is officially the first language of the Republic, in Northern Ireland the language has little legal status at all. Irish in Northern Ireland has declined rapidly, with its traditional Irish speaking-communities being replaced by learners and Gaelscoileanna. A recent development has been the interest shown by some Protestants in East Belfast who found out Irish was not an exclusively Catholic language and had been spoken by Protestants, mainly Presbyterians, in Ulster. In the 19th century fluency in Irish was at times a prerequisite to become a Presbyterian minister.

References

{{Language histories