History of rockets on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The first

The dating of the invention of the first rocket, otherwise known as the gunpowder propelled fire arrow, is disputed. The '' History of Song'' attributes the invention to two different people at different times,

The dating of the invention of the first rocket, otherwise known as the gunpowder propelled fire arrow, is disputed. The '' History of Song'' attributes the invention to two different people at different times,

Lagari Hasan Çelebi was a legendary Ottoman aviator who, according to an account written by

Lagari Hasan Çelebi was a legendary Ottoman aviator who, according to an account written by

Rocket warfare.jpg, A painting showing the Mysorean army fighting the British forces with

In 1792, iron-cased rockets were successfully used by

William Congreve (1772-1828), son of the Comptroller of the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, London, became a major figure in the field. From 1801 Congreve researched the original design of Mysore rockets and started a vigorous development program at the Arsenal's laboratory. Congreve prepared a new propellant mixture, and developed a rocket motor with a strong iron tube with conical nose. This early

William Congreve (1772-1828), son of the Comptroller of the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, London, became a major figure in the field. From 1801 Congreve researched the original design of Mysore rockets and started a vigorous development program at the Arsenal's laboratory. Congreve prepared a new propellant mixture, and developed a rocket motor with a strong iron tube with conical nose. This early

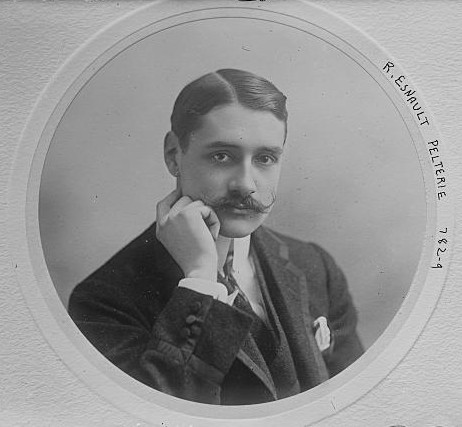

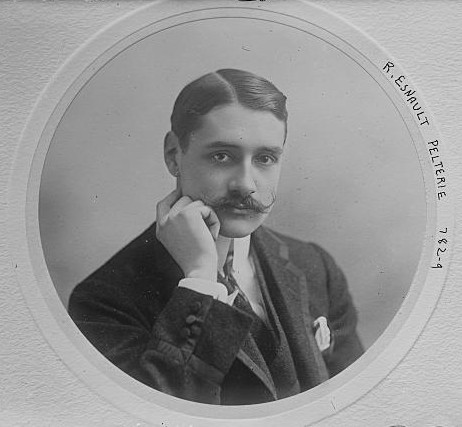

In 1912, Robert Esnault-Pelterie published a lecture on rocket theory and interplanetary travel. He independently derived Tsiolkovsky's rocket equation, did basic calculations about the energy required to make round trips to the Moon and planets, and he proposed the use of atomic power (i.e. radium) to power a jet drive.

In 1912, Robert Esnault-Pelterie published a lecture on rocket theory and interplanetary travel. He independently derived Tsiolkovsky's rocket equation, did basic calculations about the energy required to make round trips to the Moon and planets, and he proposed the use of atomic power (i.e. radium) to power a jet drive.

In 1912 Robert Goddard, inspired from an early age by H.G. Wells and by his personal interest in science, began a serious analysis of rockets, concluding that conventional solid-fuel rockets needed to be improved in three ways. First, fuel should be burned in a small combustion chamber, instead of building the entire propellant container to withstand the high pressures. Second, rockets could be arranged in stages. Finally, the exhaust speed (and thus the efficiency) could be greatly increased to beyond the speed of sound by using a

In 1912 Robert Goddard, inspired from an early age by H.G. Wells and by his personal interest in science, began a serious analysis of rockets, concluding that conventional solid-fuel rockets needed to be improved in three ways. First, fuel should be burned in a small combustion chamber, instead of building the entire propellant container to withstand the high pressures. Second, rockets could be arranged in stages. Finally, the exhaust speed (and thus the efficiency) could be greatly increased to beyond the speed of sound by using a

''Hermann Oberth, pǎrintele zborului cosmic''

("Hermann Oberth, Father of Cosmic Flight") (in Romanian), pp. 3, 11, 13, 15. In 1929, he published a book, ''Wege zur Raumschiffahrt ("Ways to Spaceflight")'', and static-fired an uncooled liquid-fueled rocket engine for a brief time. In 1924, Tsiolkovsky also wrote about multi-stage rockets, in 'Cosmic Rocket Trains'.

Modern rockets originated in the US when Robert Goddard attached a supersonic (

Modern rockets originated in the US when Robert Goddard attached a supersonic ( In 1927 the German car manufacturer

In 1927 the German car manufacturer  The Opel-RAK program and the spectacular public demonstrations of ground and air vehicles drew large crowds and caused global public excitement known as "rocket rumble", and had a large long-lasting impact on later spaceflight pioneers, in particular Wernher von Braun. Sixteen-year old von Braun was so enthusiastic about the public Opel-RAK demonstrations, that he constructed his own homemade rocket car, nearly killing himself in the process, and causing a major disruption in a crowded street by detonating the toy wagon to which he had attached fireworks. He was taken into custody by the local police until his father came to get him. The

The Opel-RAK program and the spectacular public demonstrations of ground and air vehicles drew large crowds and caused global public excitement known as "rocket rumble", and had a large long-lasting impact on later spaceflight pioneers, in particular Wernher von Braun. Sixteen-year old von Braun was so enthusiastic about the public Opel-RAK demonstrations, that he constructed his own homemade rocket car, nearly killing himself in the process, and causing a major disruption in a crowded street by detonating the toy wagon to which he had attached fireworks. He was taken into custody by the local police until his father came to get him. The  In Germany, engineers and scientists became enthralled with liquid propulsion, building and testing them in the late 1920s within Opel RAK in Rüsselsheim. According to Max Valier's account, Opel RAK rocket designer, Friedrich Wilhelm Sander launched two liquid-fuel rockets at Opel Rennbahn in Rüsselsheim on April 10 and April 12, 1929. These Opel RAK rockets have been the first European, and after Goddard the world's second, liquid-fuel rockets in history. In his book “Raketenfahrt” Valier describes the size of the rockets as in diameter and long, weighing empty and fueled. The maximum thrust was , with a total burning time of 132 seconds. These properties indicate a gas pressure pumping. The first missile rose so quickly that Sander lost sight of it. Two days later, a second unit was ready to go. Sander tied a rope to the rocket. After half the rope had been unwound, the line broke and this rocket also was lost, probably near the Opel proving ground and racetrack in Rüsselsheim, the "Rennbahn". The main purpose of these tests was to develop an aircraft propulsion system for crossing the English channel. Also, spaceflight historian

In Germany, engineers and scientists became enthralled with liquid propulsion, building and testing them in the late 1920s within Opel RAK in Rüsselsheim. According to Max Valier's account, Opel RAK rocket designer, Friedrich Wilhelm Sander launched two liquid-fuel rockets at Opel Rennbahn in Rüsselsheim on April 10 and April 12, 1929. These Opel RAK rockets have been the first European, and after Goddard the world's second, liquid-fuel rockets in history. In his book “Raketenfahrt” Valier describes the size of the rockets as in diameter and long, weighing empty and fueled. The maximum thrust was , with a total burning time of 132 seconds. These properties indicate a gas pressure pumping. The first missile rose so quickly that Sander lost sight of it. Two days later, a second unit was ready to go. Sander tied a rope to the rocket. After half the rope had been unwound, the line broke and this rocket also was lost, probably near the Opel proving ground and racetrack in Rüsselsheim, the "Rennbahn". The main purpose of these tests was to develop an aircraft propulsion system for crossing the English channel. Also, spaceflight historian

At the start of the war, the British had equipped their warships with unrotated projectile unguided anti-aircraft rockets, and by 1940, the Germans had developed a surface-to-surface

At the start of the war, the British had equipped their warships with unrotated projectile unguided anti-aircraft rockets, and by 1940, the Germans had developed a surface-to-surface

''World War 2 Planes''. Retrieved: 22 March 2009. etc.). During the war Germany also developed several guided and unguided air-to-air, ground-to-air and ground-to-ground missiles (see

Dornberger-Axter-von Braun.jpg, Dornberger and Von Braun after being captured by the Allies.

Semyorka Rocket R7 by Sergei Korolyov in VDNH Ostankino RAF0540.jpg, R-7 8K72 " Vostok" permanently displayed at the Moscow Trade Fair at Ostankino; the rocket is held in place by its railway carrier, which is mounted on four diagonal beams that constitute the display pedestal. Here the railway carrier has tilted the rocket upright as it would do so into its launch pad structure—which is missing for this display.

Mk 2.jpg, Prototype of the

At the end of World War II, competing Russian, British, and US military and scientific crews raced to capture technology and trained personnel from the German rocket program at Peenemünde. Russia and Britain had some success, but the

Rockets became extremely important militarily as modern intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) when it was realized that

Rockets became extremely important militarily as modern intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) when it was realized that  Fueled partly by the

Fueled partly by the

"Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys."

Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the

rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entir ...

s were used as propulsion systems for arrow

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers ...

s, and may have appeared as early as the 10th century in Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

. However more solid documentary evidence does not appear until the 13th century. The technology probably spread across Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

in the wake of the Mongol invasions

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastation ...

of the mid-13th century. Usage of rockets as weapons before modern rocketry is attested to in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. One of the first recorded rocket launcher

A rocket launcher is a weapon that launches an unguided, rocket-propelled projectile.

History

The earliest rocket launchers documented in imperial China consisted of arrows modified by the attachment of a rocket motor to the shaft a few ...

s is the "wasp nest" fire arrow launcher produced by the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

in 1380. In Europe rockets were also used in the same year at the Battle of Chioggia. The Joseon

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and re ...

kingdom of Korea used a type of mobile multiple rocket launcher

A multiple rocket launcher (MRL) or multiple launch rocket system (MLRS) is a type of rocket artillery system that contains multiple launchers which are fixed to a single platform, and shoots its rocket ordnance in a fashion similar to a vo ...

known as the "Munjong Hwacha

The ''hwacha'' or ''hwach'a'' ( ko, 화차; Hanja: ; literally "fire cart") was a multiple rocket launcher and an organ gun of similar design which were developed in fifteenth century Korea. The former variant fired one or two hundred rocket- ...

" by 1451.

The use of rockets in war became outdated by 15th century. The use of rockets in wars was revived with the creation of iron-cased rockets, which were used by Kingdom of Mysore

The Kingdom of Mysore was a realm in South India, southern India, traditionally believed to have been founded in 1399 in the vicinity of the modern city of Mysore. From 1799 until 1950, it was a princely state, until 1947 in a subsidiary allia ...

(Mysorean rockets

Mysorean rockets were an Indian military weapon, the iron-cased rockets were successfully deployed for military use. The Mysorean army, under Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan, used the rockets effectively against the British East India Compa ...

) and by Marathas during the mid 18th century, and were later copied by the British. The later models and improvements were known as the Congreve rocket

The Congreve rocket was a type of rocket artillery designed by British inventor Sir William Congreve in 1808.

The design was based upon the rockets deployed by the Kingdom of Mysore against the East India Company during the Second, Third, ...

and used in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

.

China

The dating of the invention of the first rocket, otherwise known as the gunpowder propelled fire arrow, is disputed. The '' History of Song'' attributes the invention to two different people at different times,

The dating of the invention of the first rocket, otherwise known as the gunpowder propelled fire arrow, is disputed. The '' History of Song'' attributes the invention to two different people at different times, Feng Zhisheng Feng may refer to:

*Feng (surname), one of several Chinese surnames in Mandarin:

**Féng (surname) ( wikt:冯 féng 2nd tone "gallop"), very common Chinese surname

**Fèng (surname) ( wikt:鳳 fèng 4th tone "phoenix"), relatively common Chinese fa ...

in 969 and Tang Fu Tang Fu (唐福) was a Chinese inventor, military engineer, and naval captain who lived during the Song dynasty. Although he did not invent the fire arrow, an early form of gunpowder rocket, he is credited as having invented "a rocket of a new style ...

in 1000. However Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, i ...

argues that rockets could not have existed before the 12th century, since the gunpowder formulas listed in the Wujing Zongyao

The ''Wujing Zongyao'' (), sometimes rendered in English as the ''Complete Essentials for the Military Classics'', is a Chinese military compendium written from around 1040 to 1044.

The book was compiled during the Northern Song dynasty by Z ...

are not suitable as rocket propellant.

Rockets may have been used as early as 1232, when reports appeared describing fire arrows and 'iron pots' that could be heard for 5 leagues (25 km, or 15 miles) when they exploded upon impact, causing devastation for a radius of , apparently due to shrapnel. A "flying fire-lance" that had re-usable barrels was also mentioned to have been used by the Jin dynasty (1115–1234)

The Jin dynasty (,

; ) or Jin State (; Jurchen: Anchun Gurun), officially known as the Great Jin (), was an imperial dynasty of China that existed between 1115 and 1234. Its name is sometimes written as Kin, Jurchen Jin, Jinn, or Chin

in ...

. Rockets are recorded to have been used by the Song navy in a military exercise dated to 1245. Internal-combustion rocket propulsion is mentioned in a reference to 1264, recording that the 'ground-rat,' a type of firework

Fireworks are a class of low explosive pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. They are most commonly used in fireworks displays (also called a fireworks show or pyrotechnics), combining a large number of devices in ...

, had frightened the Empress-Mother Gongsheng at a feast held in her honor by her son the Emperor Lizong.

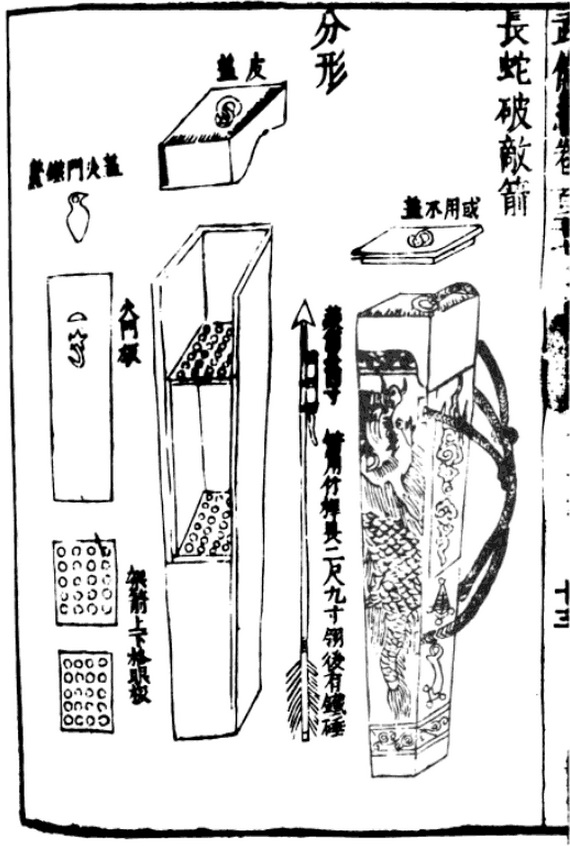

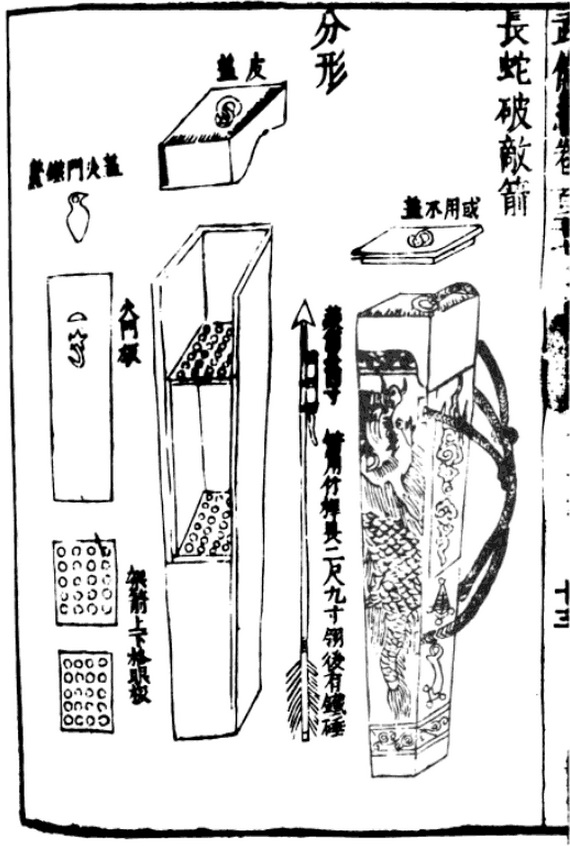

Subsequently, rockets are included in the military treatise '' Huolongjing'', also known as the Fire Drake Manual, written by the Chinese artillery officer Jiao Yu

Jiao Yu () was a Chinese military general, philosopher, and writer of the Yuan dynasty and early Ming dynasty under Zhu Yuanzhang, who founded the dynasty and became known as the Hongwu Emperor. He was entrusted by Zhu as a leading artillery ...

in the mid-14th century. This text mentions the first known multistage rocket

A multistage rocket or step rocket is a launch vehicle that uses two or more rocket ''stages'', each of which contains its own engines and propellant. A ''tandem'' or ''serial'' stage is mounted on top of another stage; a ''parallel'' stage i ...

, the 'fire-dragon issuing from the water' (huo long chu shui), thought to have been used by the Chinese navy.Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 510.

Rocket launchers known as "wasp nests" were ordered by the Ming army in 1380. In 1400, the Ming loyalist Li Jinglong used rocket launchers against the army of Zhu Di (Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (; pronounced ; 2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), personal name Zhu Di (), was the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dyn ...

).

The American historian Frank H. Winter

Frank H. Winter (born 1942) is an American historian and writer. He is the retired Curator of Rocketry of the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) of the Smithsonian Institution of Washington, D.C. Winter is also an internationally recognized hist ...

proposed in ''The Proceedings of the Twentieth and Twenty-First History Symposia of the International Academy of Astronautics'' that southern China and the Laotian community rocket festivals might have been key in the subsequent spread of rocketry in the Orient.

Spread of rocket technology

Mongols

The Chinese fire arrow was adopted by the Mongols in northern China, who employed Chinese rocketry experts asmercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes Pseudonym, also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a memb ...

in the Mongol army. Rockets are thought to have spread via the Mongol invasions

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastation ...

to other areas of Eurasia in the mid 13th century.

Rocket-like weapons are reported to have been used at the Battle of Mohi

The Battle of Mohi (11 April 1241), also known as Battle of the Sajó River''A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East'', Vol. I, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 279; "Although Mongol losses in t ...

in the year 1241.

Middle East

Between 1270 and 1280, Hasan al-Rammah wrote his ''al-furusiyyah wa al-manasib al-harbiyya'' (''The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices''), which included 107 gunpowder recipes, 22 of which are for rockets. According to Ahmad Y Hassan, al-Rammah's recipes were more explosive than rockets used in China at the time. The terminology used by al-Rammah indicates a Chinese origin for the gunpowder weapons he wrote about, such as rockets and fire lances. Ibn al-Baitar, an Arab from Spain who had immigrated to Egypt, described saltpeter as "snow of China" ( ar, ثلج الصين ). Al-Baytar died in 1248. The earlier Arab historians called saltpeter "Chinese snow" and " Chinese salt." The Arabs used the name "Chinese arrows" to refer to rockets. The Arabs called fireworks "Chinese flowers". While saltpeter was called "Chinese Snow" by Arabs, it was called "Chinese salt" ( fa, نمک چینی ''namak-i čīnī'') by the Iranians, or "salt from the Chinese marshes" ( fa, نمک شوره چيني).India

Mercenaries are recorded to have used hand held rockets in India in 1300. By the mid-14th centuryIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

ns were also using rockets in warfare.

The Kingdom of Mysore

The Kingdom of Mysore was a realm in South India, southern India, traditionally believed to have been founded in 1399 in the vicinity of the modern city of Mysore. From 1799 until 1950, it was a princely state, until 1947 in a subsidiary allia ...

used rockets during the 18th century during the Anglo-Mysore Wars

The Anglo-Mysore Wars were a series of four wars fought during the last three decades of the 18th century between the Sultanate of Mysore on the one hand, and the British East India Company (represented chiefly by the neighbouring Madras Pres ...

and wars against British. According to James Forbes Marathas also used iron-encased rockets in their battles.

Korea

The Korean kingdom of Joseon started producing gunpowder in 1374 and was producing cannons and rockets by 1377. However the multiple rocket launching carts known as the "Munjonghwacha

The ''hwacha'' or ''hwach'a'' ( ko, 화차; Hanja: ; literally "fire cart") was a multiple rocket launcher and an organ gun of similar design which were developed in fifteenth century Korea. The former variant fired one or two hundred rocket- ...

" did not appear until 1451.

Europe

In Europe,Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through emp ...

mentions gunpowder in his '' Opus Majus'' of 1267.

However rockets do not feature in European warfare until the 1380 Battle of Chioggia.

Konrad Kyeser described rockets in his famous military treatise Bellifortis around 1405."Rockets and Missiles: The Life Story of a Technology", A. Bowdoin Van Riper, p.10

Jean Froissart (c. 1337 – c. 1405) had the idea of launching rockets through tubes, so that they could make more accurate flights. Froissart's idea is a forerunner of the modern bazooka

Bazooka () is the common name for a man-portable recoilless anti-tank rocket launcher weapon, widely deployed by the United States Army, especially during World War II. Also referred to as the "stovepipe", the innovative bazooka was among the ...

.

Adoption in Renaissance-era Europe

According to the 18th-century historianLudovico Antonio Muratori

Lodovico Antonio Muratori (21 October 1672 – 23 January 1750) was an Italian historian, notable as a leading scholar of his age, and for his discovery of the Muratorian fragment, the earliest known list of New Testament books.

Biography

Bor ...

, rockets were used in the war between the Republics of Genoa and Venice at Chioggia in 1380. It is uncertain whether Muratori was correct in his interpretation, as the reference might also have been to bombard, but

Muratori is the source for the widespread claim that the earliest recorded European use of rocket artillery dates to 1380.

Konrad Kyeser described rockets in his famous military treatise Bellifortis around 1405.

Kyeser describes three types of rockets, swimming, free flying and captive.

Joanes de Fontana in ''Bellicorum instrumentorum liber'' (c. 1420) described flying rockets in the shape of doves, running rockets in the shape of hares, and a large car driven by three rockets, as well as a large rocket torpedo with the head of a sea monster.

In the mid-16th century, Conrad Haas wrote a book that described rocket technology that combined fireworks

Fireworks are a class of low explosive pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. They are most commonly used in fireworks displays (also called a fireworks show or pyrotechnics), combining a large number of devices ...

and weapons technologies. This manuscript was discovered in 1961, in the Sibiu

Sibiu ( , , german: link=no, Hermannstadt , la, Cibinium, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Härmeschtat'', hu, Nagyszeben ) is a city in Romania, in the historical region of Transylvania. Located some north-west of Bucharest, the city straddles the Ci ...

public records (Sibiu public records ''Varia II 374''). His work dealt with the theory of motion of multi-stage rockets, different fuel mixtures using liquid fuel, and introduced delta-shape fins and bell-shaped nozzle

A nozzle is a device designed to control the direction or characteristics of a fluid flow (specially to increase velocity) as it exits (or enters) an enclosed chamber or pipe.

A nozzle is often a pipe or tube of varying cross sectional area, ...

s.

The name ''Rocket'' comes from the Italian ''rocchetta'', meaning "bobbin" or "little spindle", given due to the similarity in shape to the bobbin or spool used to hold the thread to be fed to a spinning wheel. The Italian term was adopted into German in the mid 16th century, by Leonhard Fronsperger Leonhard Fronsperger (c. 1520–1575) was a Bavarian German soldier and author. He received the citizenship of Ulm in 1548 and served in the imperial army during 1553–1573, under Charles V, Ferdinand I and Maximilian II.

He retired ...

in a book on rocket artillery published in 1557, using the spelling ''rogete'', and by Conrad Haas as ''rackette''; adoption into English dates to ca. 1610. Johann Schmidlap, a German fireworks maker, is believed to have experimented with staging in 1590.

Early modern history

Lagari Hasan Çelebi was a legendary Ottoman aviator who, according to an account written by

Lagari Hasan Çelebi was a legendary Ottoman aviator who, according to an account written by Evliya Çelebi

Derviş Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi ( ota, اوليا چلبى), was an Ottoman explorer who travelled through the territory of the Ottoman Empire and neighboring lands over a period of forty years, recording ...

, made a successful manned rocket flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

. Evliya Çelebi purported that in 1633 Lagari launched in a 7-winged rocket using 50 okka (63.5 kg, or 140 lbs) of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

from Sarayburnu, the point below Topkapı Palace

The Topkapı Palace ( tr, Topkapı Sarayı; ota, طوپقپو سرايى, ṭopḳapu sarāyı, lit=cannon gate palace), or the Seraglio, is a large museum in the east of the Fatih district of Istanbul in Turkey. From the 1460s to the compl ...

in Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

.

Siemienowicz

"''Artis Magnae Artilleriae pars prima''" ("Great Art of Artillery, the First Part", also known as "The Complete Art of Artillery"), first printed inAmsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

in 1650, was translated to French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

in 1651, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

in 1676, English and Dutch in 1729 and Polish in 1963. For over two centuries, this work of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteris ...

Kazimierz Siemienowicz

Kazimierz Siemienowicz ( la, Casimirus Siemienowicz, lt, Kazimieras Simonavičius; born 1600 – 1651) was a general of artillery, gunsmith, military engineer, and one of pioneers of rocketry. Born in the Raseiniai region of the Grand Duchy o ...

Tadeusz Nowak "''Kazimierz Siemienowicz, ca.1600-ca.1651''", MON Press, Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

1969, p.182 was used in Europe as a basic artillery manual. The book provided the standard designs for creating rockets, fireballs, and other pyrotechnic devices. It contained a large chapter on caliber, construction, production and properties of rockets (for both military and civil purposes), including multi-stage rockets, batteries of rockets, and rockets with delta wing

A delta wing is a wing shaped in the form of a triangle. It is named for its similarity in shape to the Greek uppercase letter delta (Δ).

Although long studied, it did not find significant applications until the Jet Age, when it proved suita ...

stabilizers (instead of the common guiding rods).

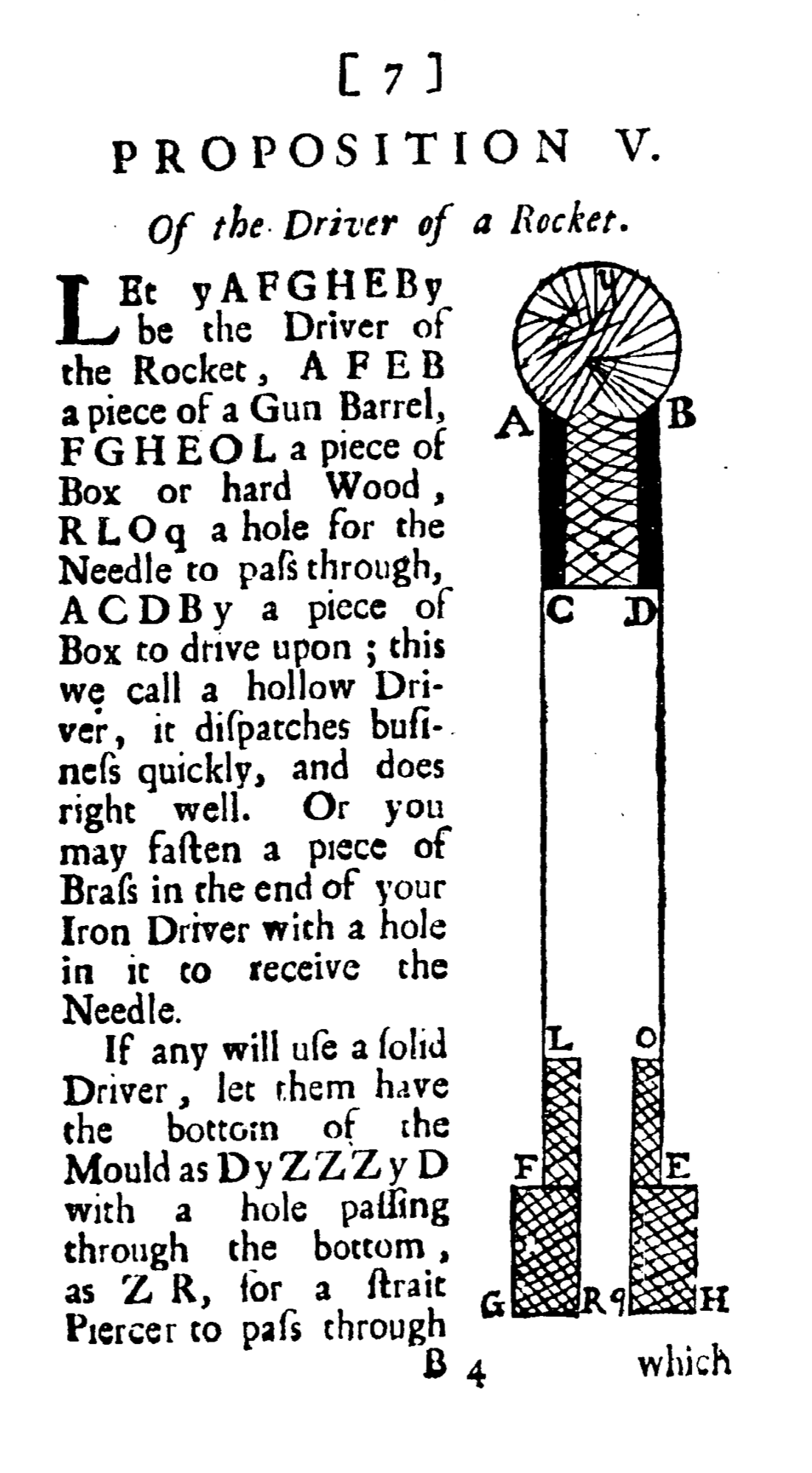

Anderson

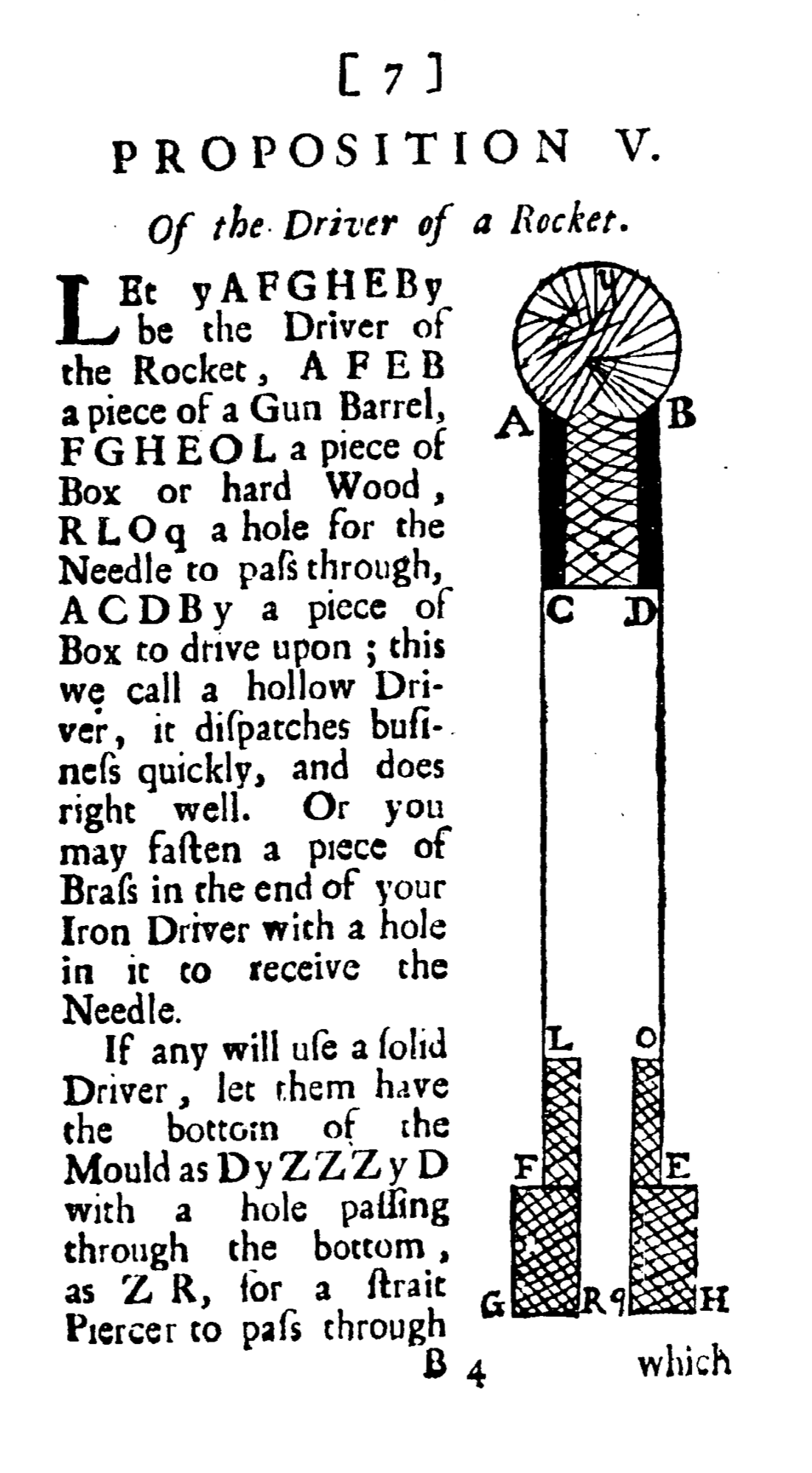

In his 1696 work, ‘The Making of Rockets. In two Parts. The First containing the Making of Rockets for the meanest Capacity. The other to make Rockets by a Duplicate Proposition, to 1,000 pound Weight or higher,’ Robert Anderson proposed constructing rockets out of "a piece of a Gun Barrel" whose metal casing is much stronger than pasteboard or wood.Indian Mysorean rockets

Mysorean rockets

Mysorean rockets were an Indian military weapon, the iron-cased rockets were successfully deployed for military use. The Mysorean army, under Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan, used the rockets effectively against the British East India Compa ...

.

Indian soldier of Tipu Sultan's army.jpg, A Mysorean soldier from India, using his Mysorean rocket as a flagstaff (Robert Home

Robert Home (1752–1834) was a British oil portrait painter who travelled to the Indian subcontinent in 1791. During his travels he also painted historic scenes and landscapes.

Life and work

Born in Hull in the United Kingdom as the son of ...

, 1793/4).

NL-HaNA 1.11.01.01 1276 1R Brief van J.G. van Angelbeek, gouverneur van Ceylon, uit Cochin, aan de heer Decker, berichtend over de strijd tussen Tipoe en de vorst van Travancone. 1790 januari 14 (cropped).jpg, Use of rockets in an assault by Mysorean troops on Travancore Line fortification (29 December 1789)

Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He i ...

- the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore

The Kingdom of Mysore was a realm in South India, southern India, traditionally believed to have been founded in 1399 in the vicinity of the modern city of Mysore. From 1799 until 1950, it was a princely state, until 1947 in a subsidiary allia ...

(in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

) against the larger British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

forces during the Anglo-Mysore Wars

The Anglo-Mysore Wars were a series of four wars fought during the last three decades of the 18th century between the Sultanate of Mysore on the one hand, and the British East India Company (represented chiefly by the neighbouring Madras Pres ...

. The British then took an active interest in the technology and developed it further during the 19th century. Use of iron tubes for holding propellant enabled higher thrust and longer range for the missile (up to 2 km range).

After Tipu's defeat in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War and the capture of the Mysore iron rockets, they were influential in British rocket development, inspiring the Congreve rocket

The Congreve rocket was a type of rocket artillery designed by British inventor Sir William Congreve in 1808.

The design was based upon the rockets deployed by the Kingdom of Mysore against the East India Company during the Second, Third, ...

, which was soon put into use in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

.

19th-century gunpowder-rocket artillery

William Congreve (1772-1828), son of the Comptroller of the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, London, became a major figure in the field. From 1801 Congreve researched the original design of Mysore rockets and started a vigorous development program at the Arsenal's laboratory. Congreve prepared a new propellant mixture, and developed a rocket motor with a strong iron tube with conical nose. This early

William Congreve (1772-1828), son of the Comptroller of the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, London, became a major figure in the field. From 1801 Congreve researched the original design of Mysore rockets and started a vigorous development program at the Arsenal's laboratory. Congreve prepared a new propellant mixture, and developed a rocket motor with a strong iron tube with conical nose. This early Congreve rocket

The Congreve rocket was a type of rocket artillery designed by British inventor Sir William Congreve in 1808.

The design was based upon the rockets deployed by the Kingdom of Mysore against the East India Company during the Second, Third, ...

weighed about 32 pounds (14.5 kilograms). The Royal Arsenal's first demonstration of solid-fuel rockets took place in 1805. The rockets were effectively used during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

and the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

. Congreve published three books on rocketry.

Subsequently, the use of military rockets spread throughout the western world. At the Battle of Baltimore in 1814, the rockets fired on Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attac ...

by the rocket vessel

A rocket vessel was a ship equipped with rockets as a weapon. The most famous ship of this type was HMS ''Erebus'', which at the Battle of Baltimore in 1814 provided the "rockets' red glare" that was memorialized by Francis Scott Key in The Sta ...

HMS ''Erebus'' were the source of the ''rockets' red glare'' described by Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet from Frederick, Maryland, who wrote the lyrics for the American national anthem "The Star-Spangled Banner". Key observed the British bombardment ...

in "The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the ...

". Rockets were also used in the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

in 1815.

Early rockets were very inaccurate. Without the use of spinning or any controlling feedback-loop, they had a strong tendency to veer sharply away from their intended course. The early Mysorean rockets

Mysorean rockets were an Indian military weapon, the iron-cased rockets were successfully deployed for military use. The Mysorean army, under Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan, used the rockets effectively against the British East India Compa ...

and their successor British Congreve rocket

The Congreve rocket was a type of rocket artillery designed by British inventor Sir William Congreve in 1808.

The design was based upon the rockets deployed by the Kingdom of Mysore against the East India Company during the Second, Third, ...

s reduced veer somewhat by attaching a long stick to the end of a rocket (similar to modern bottle rocket

''Bottle Rocket'' is a 1996 American crime comedy film directed by Wes Anderson in his feature film directorial debut. The film is written by Anderson and Owen Wilson and is based on Anderson's 1994 short film of the same name. ''Bottle Rocket ...

s) to make it harder for the rocket to change course. The largest of the Congreve rockets was the 32-pound (14.5 kg) Carcass, which had a 15-foot (4.6 m) stick. Originally, sticks were mounted on the side, but this was later changed to mounting them in the center of the rocket, reducing drag and enabling the rocket to be more accurately fired from a segment of pipe.

In 1815 Alexander Dmitrievich Zasyadko Alexander Dmitrievich Zasyadko (russian: Александр Дмитриевич Засядко; 1779 – ), was artillery engineer of the Russian Imperial Army, of Ukrainian origin, lieutenant general of artillery. Designer and specialist in mi ...

(1779-1837) began his work on developing military gunpowder-rockets. He constructed rocket-launching platforms (which allowed firing of rockets in salvos - 6 rockets at a time) and gun-laying devices. Zasyadko elaborated a tactic for military use of rocket weaponry. In 1820 Zasyadko was appointed head of the Petersburg Armory, Okhtensky Powder Factory, pyrotechnic laboratory and the first Highest Artillery School in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

. He organized rocket production in a special rocket workshop and formed the first rocket sub-unit in the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

.

Artillery captain Józef Bem (1794-1850) of the Kingdom of Poland started experiments with what was then called in Polish ''raca kongrewska''. These culminated in his 1819 report ''Notes sur les fusees incendiares'' (German edition: ''Erfahrungen über die Congrevischen Brand-Raketen bis zum Jahre 1819 in der Königlichen Polnischen Artillerie gesammelt'', Weimar 1820). The research took place in the Warsaw Arsenal, where captain Józef Kosiński also developed multiple-rocket launchers adapted from horse artillery

Horse artillery was a type of light, fast-moving, and fast-firing artillery which provided highly mobile fire support, especially to cavalry units. Horse artillery units existed in armies in Europe, the Americas, and Asia, from the early 17th to ...

gun carriage

A gun carriage is a frame and mount that supports the gun barrel of an artillery piece, allowing it to be maneuvered and fired. These platforms often had wheels so that the artillery pieces could be moved more easily. Gun carriages are also use ...

. The 1st Rocketeer Corps formed in 1822; it first saw combat during the Polish–Russian War 1830–31.

Accuracy greatly improved in 1844 when William Hale modified the rocket design so that thrust was slightly vectored, causing the rocket to spin along its axis-of-travel like a bullet. The Hale rocket removed the need for a rocket stick, travelled further due to reduced air-resistance, and was far more accurate.

In 1865 the British Colonel Edward Mounier Boxer built an improved version of the Congreve rocket by placing two rockets in one tube, one behind the other.

Early 20th-century rocket pioneers

At the beginning of the 20th century, there was a burst of scientific investigation into interplanetary travel, fueled by the creativity of fiction writers such asJules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the '' Voyages extra ...

and H. G. Wells as well as philosophical movements like Russian cosmism. Scientists seized on the rocket as a technology that was able to achieve this in real life, a possibility first recognized in 1861 by William Leitch.

In 1903, high school mathematics teacher Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935), inspired by Verne and Cosmism Cosmism may refer to:

* A religious philosophical position from the writings of Hugo de Garis

* Russian cosmism, a philosophical and cultural movement in Russia in the early 20th century

See also

* Cosmicism, a literary philosophy by H. P. Lovecr ...

, published ''The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices'' (''The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices''), the first serious scientific work on space travel. The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (russian: Константи́н Эдуа́рдович Циолко́вский , , p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin ɪdʊˈardəvʲɪtɕ tsɨɐlˈkofskʲɪj , a=Ru-Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.oga; – 19 September 1935) ...

—the principle that governs rocket propulsion—is named in his honor (although it had been discovered previously, Tsiolkovsky is honored as being the first to apply it to the question of whether rockets could achieve speeds necessary for space travel). He also advocated the use of liquid hydrogen and oxygen for propellant, calculating their maximum exhaust velocity. His work was essentially unknown outside the Soviet Union, but inside the country it inspired further research, experimentation and the formation of the Society for Studies of Interplanetary Travel in 1924.

In 1912, Robert Esnault-Pelterie published a lecture on rocket theory and interplanetary travel. He independently derived Tsiolkovsky's rocket equation, did basic calculations about the energy required to make round trips to the Moon and planets, and he proposed the use of atomic power (i.e. radium) to power a jet drive.

In 1912, Robert Esnault-Pelterie published a lecture on rocket theory and interplanetary travel. He independently derived Tsiolkovsky's rocket equation, did basic calculations about the energy required to make round trips to the Moon and planets, and he proposed the use of atomic power (i.e. radium) to power a jet drive.

In 1912 Robert Goddard, inspired from an early age by H.G. Wells and by his personal interest in science, began a serious analysis of rockets, concluding that conventional solid-fuel rockets needed to be improved in three ways. First, fuel should be burned in a small combustion chamber, instead of building the entire propellant container to withstand the high pressures. Second, rockets could be arranged in stages. Finally, the exhaust speed (and thus the efficiency) could be greatly increased to beyond the speed of sound by using a

In 1912 Robert Goddard, inspired from an early age by H.G. Wells and by his personal interest in science, began a serious analysis of rockets, concluding that conventional solid-fuel rockets needed to be improved in three ways. First, fuel should be burned in a small combustion chamber, instead of building the entire propellant container to withstand the high pressures. Second, rockets could be arranged in stages. Finally, the exhaust speed (and thus the efficiency) could be greatly increased to beyond the speed of sound by using a De Laval nozzle

A de Laval nozzle (or convergent-divergent nozzle, CD nozzle or con-di nozzle) is a tube which is pinched in the middle, making a carefully balanced, asymmetric hourglass shape. It is used to accelerate a compressible fluid to supersonic speeds ...

. He patented these concepts in 1914. He also independently developed the mathematics of rocket flight.

Goddard worked on developing solid-propellant rocket

A solid-propellant rocket or solid rocket is a rocket with a rocket engine that uses solid propellants ( fuel/oxidizer). The earliest rockets were solid-fuel rockets powered by gunpowder; they were used in warfare by the Arabs, Chinese, Pe ...

s since 1914, and demonstrated a light battlefield rocket to the US Army Signal Corps only five days before the signing of the armistice that ended World War I. He also started developing liquid-propellant rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket utilizes a rocket engine that uses liquid propellants. Liquids are desirable because they have a reasonably high density and high specific impulse (''I''sp). This allows the volume of the propellant ta ...

s in 1921, yet he had not been taken seriously by the public. Nevertheless, Goddard reclusively developed and flew a small liquid-fueled rocket. He developed the technology for 214 patents, 212 of which his wife published after his death.

During World War I Yves Le Prieur, a French naval officer and inventor, later to create a pioneering scuba diving

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for " Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chr ...

apparatus, developed air-to-air solid-fuel rockets. The aim was to destroy observation captive balloons (called saucisses or Drachens) used by German artillery. These rather crude black powder, steel-tipped incendiary rockets (made by Ruggieri Ruggieri is an Italian surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Claude Ruggieri (1777–1841), fireworks producer and designer

* Gaetano Ruggieri, fireworks producer and designer, famous for his involvement in the fireworks in London in ...

) were first tested from a Voisin aircraft Voisin (French for "neighbour") may refer to:

Companies

*Avions Voisin, the French automobile company

:* Voisin Laboratoire, a car manufactured by Avions Voisin

*Voisin (aircraft), the French aircraft manufacturer

* Voisin, a Lyon-based chocola ...

, wing-bolted on a fast Picard Pictet sports car and then used in battle on real aircraft. A typical layout was eight electrically fired Le Prieur rockets fitted on the interpane struts of a Nieuport

Nieuport, later Nieuport-Delage, was a French aeroplane company that primarily built racing aircraft before World War I and fighter aircraft during World War I and between the wars.

History

Beginnings

Originally formed as Nieuport-Duplex in ...

aircraft. If fired at sufficiently short distance, a spread of Le Prieur rockets proved to be quite deadly. Belgian ace Willy Coppens claimed dozens of Drachen kills during World War I.

In 1920, Goddard published his ideas and experimental results in '' A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes''. The work included remarks about sending a solid-fuel rocket to the Moon, which attracted worldwide attention and was both praised and ridiculed. A ''New York Times'' editorial suggested, referring to Newton's Third Law.

In reality, in terms of Newton's third law, a rocket "pushes against" its exhaust gases, so the lack of surrounding air is not relevant.

In 1923, German Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Konstantin ...

(1894–1989) published ''Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen'' ("The Rocket into Planetary Space"), a version of his doctoral thesis, after the University of Munich had rejected it.Jürgen Heinz Ianzer''Hermann Oberth, pǎrintele zborului cosmic''

("Hermann Oberth, Father of Cosmic Flight") (in Romanian), pp. 3, 11, 13, 15. In 1929, he published a book, ''Wege zur Raumschiffahrt ("Ways to Spaceflight")'', and static-fired an uncooled liquid-fueled rocket engine for a brief time. In 1924, Tsiolkovsky also wrote about multi-stage rockets, in 'Cosmic Rocket Trains'.

Modern rocketry

Pre-World War II

Modern rockets originated in the US when Robert Goddard attached a supersonic (

Modern rockets originated in the US when Robert Goddard attached a supersonic (de Laval

Karl Gustaf Patrik de Laval (; 9 May 1845 – 2 February 1913) was a Swedish engineer and inventor who made important contributions to the design of steam turbines and centrifugal separation machinery for dairy.

Life

Gustaf de Laval was born a ...

) nozzle to the combustion chamber of a liquid-fueled rocket engine. This turned the hot combustion chamber gas into a cooler, highly directed hypersonic

In aerodynamics, a hypersonic speed is one that exceeds 5 times the speed of sound, often stated as starting at speeds of Mach 5 and above.

The precise Mach number at which a craft can be said to be flying at hypersonic speed varies, since ind ...

jet of gas, more than doubling the thrust and raising the engine efficiency from 2% to 64%. On 16 March 1926, Goddard launched the world's first liquid-fueled rocket in Auburn, Massachusetts.

During the 1920s, a number of rocket research organizations appeared worldwide. Rocketry in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

began in 1921 with extensive work at the Gas Dynamics Laboratory (GDL), where the first test-firing of a solid fuel rocket was carried out in March 1928, which flew for about 1,300 meters In 1931 the world's first successful use of rockets to assist take-off of aircraft were carried out on a U-1, the Soviet designation for a Avro 504 trainer, which achieved about one hundred successful assisted takeoffs. Further developments in the early 1930s included firing rockets from aircraft and the ground. In 1932 in-air test firings of RS-82 missiles from an Tupolev I-4 aircraft armed with six launchers successfully took place. In September 1931 the Group for the Study of Reactive Motion

The Moscow-based Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (also 'Group for the Investigation of Reactive Engines and Reactive Flight' and 'Jet Propulsion Study Group') (russian: Группа изучения реактивного движения, ...

(GIRD) was formed and was responsible for the first Soviet liquid propelled rocket launch, the GIRD-9, on 17 August 1933, which reached an altitude of .

In 1933 GDL and GIRD were merged to form the Reactive Scientific Research Institute

Reactive Scientific Research Institute (commonly known by the joint initialism RNII; russian: Реактивный научно-исследовательский институт, Reaktivnyy nauchno-issledovatel’skiy institut) was one of the ...

(RNII) and developments were continued, including designing several variations for ground-to-air, ground-to-ground, air-to-ground and air-to-air combat. The RS-82 rockets were carried by Polikarpov I-15

The Polikarpov I-15 (russian: И-15) was a Soviet biplane fighter aircraft of the 1930s. Nicknamed ''Chaika'' (''russian: Чайка'', "Seagull") because of its gulled upper wings,Gunston 1995, p. 299.Green and Swanborough 1979, p. 10. it was ...

, I-16 I16 may refer to:

* Interstate 16, an interstate highway in the U.S. state of Georgia

* Polikarpov I-16, a Soviet fighter aircraft introduced in the 1930s

* Halland Regiment

* , a Japanese Type C submarine

* i16, a name for the 16-bit signed integ ...

and I-153

The Polikarpov I-153 ''Chaika'' (Russian ''Чайка'', "Seagull") was a late 1930s Soviet biplane fighter. Developed as an advanced version of the I-15 with a retractable undercarriage, the I-153 fought in the Soviet-Japanese combats in Mon ...

fighter planes, the Polikarpov R-5

The Polikarpov R-5 (russian: Р-5) was a Soviet reconnaissance bomber aircraft of the 1930s. It was the standard light bomber and reconnaissance aircraft of the Soviet Air Force for much of the 1930s, while also being used heavily as a civilian ...

reconnaissance plane and the Ilyushin Il-2 close air support plane, while the heavier RS-132 rockets could be carried by bombers. Many small ships of the Soviet Navy were also fitted with the RS-82 rocket, including the MO-class small guard ship. The earliest known use by the Soviet Air Force

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

of aircraft-launched unguided anti-aircraft rockets in combat against heavier-than-air aircraft took place in August 1939, during the Battle of Khalkhin Gol. A group of Polikarpov I-16

The Polikarpov I-16 (russian: Поликарпов И-16) is a Soviet single-engine single-seat fighter aircraft of revolutionary design; it was the world's first low-wing cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear to attain o ...

fighters under command of Captain N. Zvonarev were using RS-82 rockets against Japanese aircraft, shooting down 16 fighters and 3 bombers in total. Six Tupolev SB bombers also used RS-132 for ground attack during the Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

. RNII also built over 100 experimental rocket engines under the direction of Valentin Glushko

Valentin Petrovich Glushko (russian: Валенти́н Петро́вич Глушко́; uk, Валентин Петрович Глушко, Valentyn Petrovych Hlushko; born 2 September 1908 – 10 January 1989) was a Soviet engineer and the m ...

. Design work included regenerative cooling, hypergolic propellant

A hypergolic propellant is a rocket propellant combination used in a rocket engine, whose components spontaneously ignite when they come into contact with each other.

The two propellant components usually consist of a fuel and an oxidizer. The ...

ignition, and swirling and bi-propellant mixing fuel injector

Fuel injection is the introduction of fuel in an internal combustion engine, most commonly automotive engines, by the means of an injector. This article focuses on fuel injection in reciprocating piston and Wankel rotary engines.

All compr ...

s. However, Glushko's arrest during Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

in 1938 curtailed the developments.

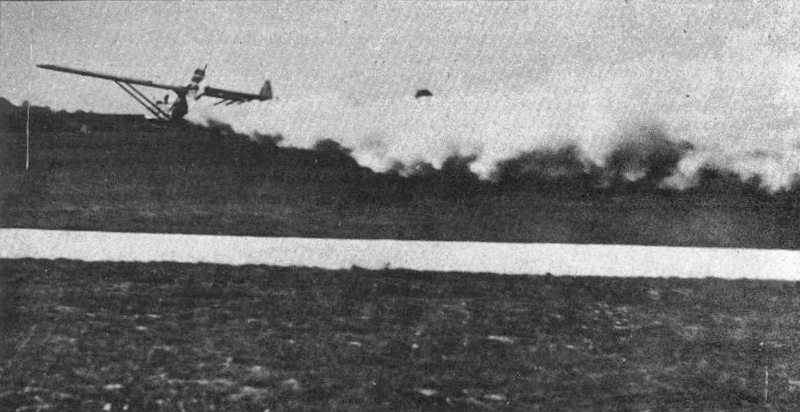

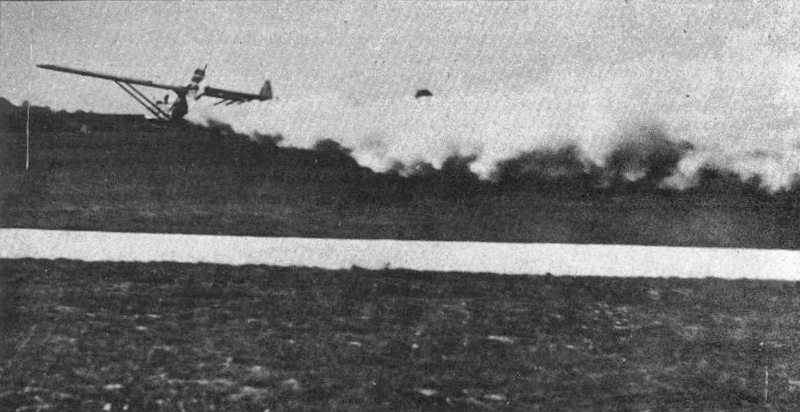

In 1927 the German car manufacturer

In 1927 the German car manufacturer Opel

Opel Automobile GmbH (), usually shortened to Opel, is a German automobile manufacturer which has been a subsidiary of Stellantis since 16 January 2021. It was owned by the American automaker General Motors from 1929 until 2017 and the PSA Grou ...

began to research rocket vehicles together with Max Valier and the solid-fuel rocket builder Friedrich Wilhelm Sander. These activities are generally considered the world's first large-scale experimental rocket program, Opel-RAK under the leadership of Fritz von Opel, leading to the first rocket cars and rocket planes, which paved the way for the German V2 program and US and Soviet activities from 1950 onwards. In 1928, Fritz von Opel drove a rocket car Opel RAK.1 on the Opel raceway in Rüsselsheim, Germany, and later the dedicated RAK2 rocket car at the AVUS speedway in Berlin. In 1928, Opel, Valier and Sander equipped the Lippisch Ente glider, which Opel had purchased, with rocket power and launched the manned glider. The "Ente" was destroyed on its second flight. Eventually glider pioneer Julius Hatry was tasked by von Opel to construct a dedicated glider, again called Opel-RAK.1, for his rocket program. On September 30, 1929 von Opel himself piloted the RAK.1, the world's first public manned rocket-powered flight from the Frankfurt-Rebstock airport, but experienced a hard landing.  The Opel-RAK program and the spectacular public demonstrations of ground and air vehicles drew large crowds and caused global public excitement known as "rocket rumble", and had a large long-lasting impact on later spaceflight pioneers, in particular Wernher von Braun. Sixteen-year old von Braun was so enthusiastic about the public Opel-RAK demonstrations, that he constructed his own homemade rocket car, nearly killing himself in the process, and causing a major disruption in a crowded street by detonating the toy wagon to which he had attached fireworks. He was taken into custody by the local police until his father came to get him. The

The Opel-RAK program and the spectacular public demonstrations of ground and air vehicles drew large crowds and caused global public excitement known as "rocket rumble", and had a large long-lasting impact on later spaceflight pioneers, in particular Wernher von Braun. Sixteen-year old von Braun was so enthusiastic about the public Opel-RAK demonstrations, that he constructed his own homemade rocket car, nearly killing himself in the process, and causing a major disruption in a crowded street by detonating the toy wagon to which he had attached fireworks. He was taken into custody by the local police until his father came to get him. The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

put an end to the Opel-RAK program and von Opel left Germany in 1930, emigrating first to the US, later to France and Switzerland. After the break-up of the Opel-RAK program, Valier eventually was killed while experimenting with liquid-fueled rockets in May 1930, and is considered the first fatality of the dawning space age.

In Germany, engineers and scientists became enthralled with liquid propulsion, building and testing them in the late 1920s within Opel RAK in Rüsselsheim. According to Max Valier's account, Opel RAK rocket designer, Friedrich Wilhelm Sander launched two liquid-fuel rockets at Opel Rennbahn in Rüsselsheim on April 10 and April 12, 1929. These Opel RAK rockets have been the first European, and after Goddard the world's second, liquid-fuel rockets in history. In his book “Raketenfahrt” Valier describes the size of the rockets as in diameter and long, weighing empty and fueled. The maximum thrust was , with a total burning time of 132 seconds. These properties indicate a gas pressure pumping. The first missile rose so quickly that Sander lost sight of it. Two days later, a second unit was ready to go. Sander tied a rope to the rocket. After half the rope had been unwound, the line broke and this rocket also was lost, probably near the Opel proving ground and racetrack in Rüsselsheim, the "Rennbahn". The main purpose of these tests was to develop an aircraft propulsion system for crossing the English channel. Also, spaceflight historian

In Germany, engineers and scientists became enthralled with liquid propulsion, building and testing them in the late 1920s within Opel RAK in Rüsselsheim. According to Max Valier's account, Opel RAK rocket designer, Friedrich Wilhelm Sander launched two liquid-fuel rockets at Opel Rennbahn in Rüsselsheim on April 10 and April 12, 1929. These Opel RAK rockets have been the first European, and after Goddard the world's second, liquid-fuel rockets in history. In his book “Raketenfahrt” Valier describes the size of the rockets as in diameter and long, weighing empty and fueled. The maximum thrust was , with a total burning time of 132 seconds. These properties indicate a gas pressure pumping. The first missile rose so quickly that Sander lost sight of it. Two days later, a second unit was ready to go. Sander tied a rope to the rocket. After half the rope had been unwound, the line broke and this rocket also was lost, probably near the Opel proving ground and racetrack in Rüsselsheim, the "Rennbahn". The main purpose of these tests was to develop an aircraft propulsion system for crossing the English channel. Also, spaceflight historian Frank H. Winter

Frank H. Winter (born 1942) is an American historian and writer. He is the retired Curator of Rocketry of the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) of the Smithsonian Institution of Washington, D.C. Winter is also an internationally recognized hist ...

, curator at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, confirms that in addition to solid-fuel rockets used for land-speed records and the world's first manned rocket-plane flights, the Opel group was working on liquid-fuel rockets (SPACEFLIGHT, Vol. 21,2, Feb. 1979): In a cabled exclusive to The New York Times on 30 September 1929, von Opel is quoted as saying: "Sander and I now want to transfer the liquid rocket from the laboratory to practical use. With the liquid rocket I hope to be the first man to thus fly across the English Channel. I will not rest until I have accomplished that." At a speech on the donation of a RAK 2 replica to the Deutsches Museum, von Opel mentioned engineer Josef Schaberger as a key collaborator. "He belonged," von Opel said, "with the same enthusiasm as Sander to our small secret group, one of the tasks of which was to hide all the preparations from my father, because his paternal apprehensions led him to believe that I was cut out for something better than being a rocket researchist. Schaberger supervised all the details involved in construction and assembly (of rocket cars), and every time I sat behind the wheel with a few hundred pounds of explosives in my rear, and made the first contact, I did so with a feeling of total security ..As early as 1928, Mr. Schaberger and I developed a liquid rocket, which was definitely the first permanently operating rocket in which the explosive was injected into the combustion chamber and simultaneously cooled using pumps. ..We used benzol as the fuel," von Opel continued, "and nitrogen tetroxide as the oxidizer. This rocket was installed in a Mueller-Griessheim aircraft and developed a thrust of ." By May 1929, the engine produced a thrust of 200 kg (440 lb.) "for longer than fifteen minutes and in July 1929, the Opel RAK collaborators were able to attain powered phases of more than thirty minutes for thrusts of . at Opel's works in Rüsselsheim," again according to Max Valier's account. The Great Depression brought an end to the Opel RAK activities. The work of Sander and Valier, who died while experimenting in 1930, was confiscated by the Heereswaffenamt

''Waffenamt'' (WaA) was the German Army Weapons Agency. It was the centre for research and development of the Weimar Republic and later the Third Reich for weapons, ammunition and army equipment to the German Reichswehr and then Wehrmacht

...

and integrated into the activities under General Walter Dornberger

Major-General Dr. Walter Robert Dornberger (6 September 1895 – 26 June 1980) was a German Army artillery officer whose career spanned World War I and World War II. He was a leader of Nazi Germany's V-2 rocket programme and other projects a ...

in the early and mid-1930s in a field near Berlin.

An amateur rocket group, the VfR, co-founded by Max Valier, included Wernher von Braun, who eventually became the head of the army research station that designed the V-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develop ...

weapon for the Nazis. When private rocket-engineering became forbidden in Germany, Sander was arrested by Gestapo in 1935, convicted of treason, sentenced to 5 years in prison, and forced to sell his company. He died in 1938.

Lieutenant Colonel Karl Emil Becker, head of the German Army's Ballistics and Munitions Branch, gathered a small team of engineers that included Walter Dornberger

Major-General Dr. Walter Robert Dornberger (6 September 1895 – 26 June 1980) was a German Army artillery officer whose career spanned World War I and World War II. He was a leader of Nazi Germany's V-2 rocket programme and other projects a ...

and Leo Zanssen, to figure out how to use rockets as long-range artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

in order to get around the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

' ban on research and development of long-range cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s. Wernher von Braun, a young engineering prodigy who as an eighteen-year-old student helped Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Konstantin ...

build his liquid rocket engine, was recruited by Becker and Dornberger to join their secret army program at Kummersdorf-West in 1932. Von Braun dreamed of conquering outer space with rockets and did not initially see the military value in missile technology.

In 1927 a team of German rocket engineers, including Opel RAK's Max Valier, had formed the '' Verein für Raumschiffahrt'' (Society for Space Travel, or VfR), and in 1931 launched a liquid propellant rocket (using oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

and gasoline

Gasoline (; ) or petrol (; ) (see ) is a transparent, petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines (also known as petrol engines). It consists mostly of organic c ...

).

Similar work was done from 1932 onwards by the Austrian professor Eugen Sänger, who migrated to Germany in 1936 and worked on rocket-powered spaceplanes such as Silbervogel (sometimes called the "antipodal" bomber).

On November 12, 1932 at a farm in Stockton NJ, the American Interplanetary Society's attempt to static-fire their first rocket (based on German Rocket Society designs) failed in a fire.

In 1936, a British research programme based at Fort Halstead in Kent under the direction of Dr. Alwyn Crow started work on a series of unguided solid-fuel rocket

A solid-propellant rocket or solid rocket is a rocket with a rocket engine that uses solid propellants (fuel/oxidizer). The earliest rockets were solid-fuel rockets powered by gunpowder; they were used in warfare by the Arabs, Chinese, Persia ...

s that could be used as anti-aircraft weapons. In 1939, a number of test firings were carried out in the British colony

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom. They are the last remnants of the former Bri ...

of Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

, on a specially built range.

In the 1930s, the German ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshape ...

'' (which in 1935 became the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

'') began to take an interest in rocketry. Artillery restrictions imposed by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

limited Germany's access to long-distance weaponry. Seeing the possibility of using rockets as long-range artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

fire, the Wehrmacht initially funded the VfR team, but because their focus was strictly scientific, created its own research team. At the behest of military leaders, Wernher von Braun, at the time a young aspiring rocket scientist, joined the military (followed by two former VfR members) and developed long-range weapons for use in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

.

In June 1938, the Soviet Reactive Scientific Research Institute

Reactive Scientific Research Institute (commonly known by the joint initialism RNII; russian: Реактивный научно-исследовательский институт, Reaktivnyy nauchno-issledovatel’skiy institut) was one of the ...

(RNII) began developing a multiple rocket launcher based on the RS-132 rocket. In August 1939, the completed rocket was the BM-13 / Katyusha rocket launcher (BM stands for ''боевая машина'' (translit. ''boyevaya mashina''), 'combat vehicle' for M-13 rockets). Towards the end of 1938 the first significant large scale testing of the rocket launchers took place, 233 rockets of various types were used. A salvo of rockets could completely straddle a target at a range of . Various rocket tests were conducted through 1940, and the BM-13-16 with launch rails for sixteen rockets was authorized for production. Only forty launchers were built before Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941.

World War II

multiple rocket launcher

A multiple rocket launcher (MRL) or multiple launch rocket system (MLRS) is a type of rocket artillery system that contains multiple launchers which are fixed to a single platform, and shoots its rocket ordnance in a fashion similar to a vo ...

, the '' Nebelwerfer''.

The Soviet Katyusha rocket launchers

The Katyusha ( rus, Катю́ша, p=kɐˈtʲuʂə, a=Ru-Катюша.ogg) is a type of rocket artillery first built and fielded by the Soviet Union in World War II. Multiple rocket launchers such as these deliver explosives to a target area ...

were top secret in the beginning of World War II. A special unit of the NKVD troops was raised to operate them. On July 14, 1941, an experimental artillery battery of seven launchers was first used in battle at Rudnya in Smolensk Oblast

Smolensk Oblast (russian: Смоле́нская о́бласть, ''Smolenskaya oblast''; informal name — ''Smolenschina'' (russian: Смоле́нщина)) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative centre is the city o ...

of Russia, under the command of Captain Ivan Flyorov

Ivan Andreyevich Flyorov (russian: Иван Андреевич Флёров; 24 April 1905 – 7 October 1941), was a captain in the Red Army in command of the first battery of 8 '' Katyushas'' (BM-8), which was formed in Lipetsk and on 14 July 1 ...

, destroying a concentration of German troops with tanks, armored vehicles and trucks at the marketplace, causing massive German Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

casualties and its retreat from the town in panic. After their success in the first month of the war, mass production was ordered and the development of other models proceeded. The Katyusha was inexpensive and could be manufactured in light industrial installations which did not have the heavy equipment to build conventional artillery gun barrels. By the end of 1942, 3,237 Katyusha launchers of all types had been built, and by the end of the war total production reached about 10,000. with 12 million rockets of the RS type produced for the Soviet armed forces.

During the Second World War, Major-General Dornberger was the military head of the army's rocket program, Zanssen became the commandant of the Peenemünde army rocket center, and von Braun was the technical director of the ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within t ...

program. They led the team that built the Aggregat-4 (A-4) rocket, which became the first vehicle to reach outer space