The history of rail transport began in the BCE times. It can be divided into several discrete periods defined by the principal means of track material and motive power used.

Ancient systems

The

Post Track

The Post Track is an ancient causeway in the valley of the River Brue on the Somerset Levels, England. It dates from around 3838 BCE, making it some 30 years older than the Sweet Track in the same area. Various sections have been scheduled as a ...

, a prehistoric

causeway in the valley of the

River Brue

The River Brue originates in the parish of Brewham in Somerset, England, and reaches the sea some west at Burnham-on-Sea. It originally took a different route from Glastonbury to the sea, but this was changed by Glastonbury Abbey in the twelft ...

in the

Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south a ...

, England, is one of the oldest known constructed trackways and dates from around 3838 BC, making it some 30 years older than the

Sweet Track

The Sweet Track is an ancient trackway, or causeway, in the Somerset Levels, England, named after its finder, Ray Sweet. It was built in 3807 BC (determined using dendrochronology) and is the second-oldest timber trackway discovered in ...

from the same area.

Various sections have been designated as

scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

s.

Evidence indicates that there was a 6 to 8.5 km long ''

Diolkos'' paved trackway, which transported boats across the

Isthmus of Corinth in

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

from around 600 BC.

[Cook, R. M.: "Archaic Greek Trade: Three Conjectures 1. The Diolkos", ''The Journal of Hellenic Studies'', vol. 99 (1979), pp. 152–155 (152)][Lewis, M. J. T.]

"Railways in the Greek and Roman world"

, in Guy, A. / Rees, J. (eds), ''Early Railways. A Selection of Papers from the First International Early Railways Conference'' (2001), pp. 8–19 (11) Wheeled vehicles pulled by men and animals ran in grooves in

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

, which provided the track element, preventing the wagons from leaving the intended route. The Diolkos was in use for over 650 years, until at least the 1st century AD.

Paved trackways were also later built in

Roman Egypt.

In China, a railway has been discovered in south west

Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is al ...

province near Nanyang city. It was carbon dated to be about 2200 years old from the Qin dynasty. The rails are made from hard wood and treated against corrosion while the sleepers or railway ties are made from wood that was not treated and therefore has rotted. Qin railway sleepers were designed to allow horses to gallop through to the next rail station where they would be swapped for a fresh horse. The railway is theorized to have been used for transportation of goods to front line troops and to fix the Great Wall.

Pre-steam

Wooden rails introduced

In 1515,

Cardinal Matthäus Lang wrote a description of the

Reisszug

The Reisszug (also spelt Reißzug or Reiszug) is a private cable railway providing goods access to the Hohensalzburg Castle at Salzburg in Austria. It is notable for its extreme age, as it is believed to date back to either 1495 or 1504.

The Reis ...

, a

funicular

A funicular (, , ) is a type of cable railway system that connects points along a railway track laid on a steep slope. The system is characterized by two counterbalanced carriages (also called cars or trains) permanently attached to opposite e ...

railway at the

Hohensalzburg Fortress

Hohensalzburg Fortress (german: Festung Hohensalzburg, lit=High Salzburg Fortress) is a large medieval fortress in the city of Salzburg, Austria. It sits atop the Festungsberg at an altitude of 506 m. It was erected at the behest of the Prince-Arc ...

in Austria. The line originally used wooden rails and a

hemp haulage rope and was operated by human or animal power, through a

treadwheel

A treadwheel, or treadmill, is a form of engine typically powered by humans. It may resemble a water wheel in appearance, and can be worked either by a human treading paddles set into its circumference (treadmill), or by a human or animal standing ...

.

The line still exists and remains operational, although in updated form. It may be the oldest operational railway.

Wagonway

Wagonways (also spelt Waggonways), also known as horse-drawn railways and horse-drawn railroad consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam-powered railways. The terms plateway, tramway, dramway ...

s (or

tramways), with wooden rails and horse-drawn traffic, are known to have been used in the 1550s to facilitate transportation of ore tubs to and from mines. They soon became popular in Europe and an example of their operation was illustrated by

Georgius Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Pawer or Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman Empire ...

(see image) in his 1556 work ''

De re metallica''.

[Georgius Agricola (trans Hoover), '' De re metallica'' (1913), p. 156.] This line used "Hund" carts with unflanged wheels running on wooden planks and a vertical pin on the truck fitting into the gap between the planks to keep it going the right way. The miners called the wagons ''Hunde'' ("dogs") from the noise they made on the tracks.

There are many references to wagonways in central Europe in the 16th century.

A wagonway was introduced to England by

German miners at

Caldbeck

Caldbeck is a village in Cumbria, England, historically within Cumberland, it is situated within the Lake District National Park. The village had 714 inhabitants according to the census of 2001.

Caldbeck is closely associated with neighbouring ...

,

Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. C ...

, possibly in the 1560s.

[Warren Allison, Samuel Murphy and Richard Smith, ''An Early Railway in the German Mines of Caldbeck'' in G. Boyes (ed.), ''Early Railways 4: Papers from the 4th International Early Railways Conference 2008'' (Six Martlets, Sudbury, 2010), pp. 52–69.] A wagonway was built at

Prescot

Prescot is a town and civil parish within the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley in Merseyside, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, it lies about to the east of Liverpool city centre. At the 2001 Census, the c ...

, near

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

, sometime around 1600, possibly as early as 1594. Owned by Philip Layton, the line carried coal from a pit near Prescot Hall to a terminus about half a mile away.

A funicular railway was made at

Broseley

Broseley is a market town in Shropshire, England, with a population of 4,929 at the 2011 Census and an estimate of 5,022 in 2019. The River Severn flows to its north and east. The first The Iron Bridge, iron bridge in the world was built in 17 ...

in

Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

some time before 1604. This carried coal for James Clifford from his mines down to the

river Severn

, name_etymology =

, image = SevernFromCastleCB.JPG

, image_size = 288

, image_caption = The river seen from Shrewsbury Castle

, map = RiverSevernMap.jpg

, map_size = 288

, map_c ...

to be loaded onto barges and carried to riverside towns. The

Wollaton Wagonway

The Wollaton Wagonway (or Waggonway), built between October 1603 and 1604 in the East Midlands of England by Huntingdon Beaumont in partnership with Sir Percival Willoughby, has sometimes been credited as the world's first ''overground'' wagon ...

, completed in 1604 by

Huntingdon Beaumont

Huntingdon Beaumont (c.1560–1624) was an English coal mining entrepreneur who built two of the earliest wagonways in England for trans-shipment of coal. He was less successful as a businessman and died having been imprisoned for debt.

Beaum ...

, has sometimes erroneously been cited as the earliest British railway. It ran from

Strelley

Strelley is a village and civil parish in the Borough of Broxtowe and City of Nottingham in Nottinghamshire, England. It is to the west of Nottingham. The population of the civil parish taken at the 2011 census was 653. It is also the name of t ...

to

Wollaton

Wollaton is a suburb and former parish in the western part of Nottingham, England. Wollaton has two Wards in the City of Nottingham (''Wollaton East and Lenton Abbey'' and ''Wollaton West'') with a total population as at the 2011 census of 24,69 ...

near

Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

.

The

Middleton Railway

The Middleton Railway is the world's oldest continuously working railway, situated in the English city of Leeds. It was founded in 1758 and is now a heritage railway, run by volunteers from The Middleton Railway Trust Ltd. since 1960.

The rail ...

in

Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

, which was built in 1758, later became the world's oldest operational railway (other than funiculars), albeit now in an upgraded form. In 1764, the first railway in America was built in

Lewiston, New York

Lewiston is a town in Niagara County, New York, United States. The population was 15,944 at the 2020 census. The town and its contained village are named after Morgan Lewis, a governor of New York.

The Town of Lewiston is on the western bord ...

.

Metal rails introduced

The introduction of steam engines for powering blast air to

blast furnaces led to a large increase in British iron production after the mid 1750s.

In the late 1760s, the

Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

This is where iron ore was first s ...

Company began to fix plates of

cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impur ...

to the upper surface of wooden rails, which increased their durability and load-bearing ability. At first only

balloon loop

A balloon loop, turning loop, or reversing loop ( North American Terminology) allows a rail vehicle or train to reverse direction without having to shunt or stop. Balloon loops can be useful for passenger trains and unit freight trains.

Bal ...

s could be used for turning wagons, but later, movable points were introduced that allowed

passing loop

A passing loop (UK usage) or passing siding (North America) (also called a crossing loop, crossing place, refuge loop or, colloquially, a hole) is a place on a single line railway or tramway, often located at or near a station, where trains or ...

s to be created.

A system was introduced in which unflanged wheels ran on L-shaped metal plates these became known as

plateway

A plateway is an early kind of railway, tramway or wagonway, where the rails are made from cast iron. They were mainly used for about 50 years up to 1830, though some continued later.

Plateways consisted of "L"-shaped rails, where the flange ...

s.

John Curr

John Curr (c. 1756 – 27 January 1823) was the manager or viewer of the Duke of Norfolk's collieries in Sheffield, England from 1781 to 1801. During this time he made a number of innovations that contributed significantly to the development of t ...

, a Sheffield colliery manager, invented this flanged rail in 1787, though the exact date of this is disputed. The plate rail was taken up by

Benjamin Outram

Benjamin Outram (1 April 1764 – 22 May 1805) was an English civil engineer, surveyor and industrialist. He was a pioneer in the building of canals and tramways.

Life

Born at Alfreton in Derbyshire, he began his career assisting his father J ...

for wagonways serving his canals, manufacturing them at his

Butterley ironworks. In 1803,

William Jessop

William Jessop (23 January 1745 – 18 November 1814) was an English civil engineer, best known for his work on canals, harbours and early railways in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early life

Jessop was born in Devonport, Devon, the ...

opened the

Surrey Iron Railway

The Surrey Iron Railway (SIR) was a horse-drawn plateway that linked Wandsworth and Croydon via Mitcham, all then in Surrey but now suburbs of south London, in England. It was established by Act of Parliament in 1801, and opened partly in 1802 ...

, a double track plateway, sometimes erroneously cited as world's first public railway, in south London.

In 1789,

William Jessop

William Jessop (23 January 1745 – 18 November 1814) was an English civil engineer, best known for his work on canals, harbours and early railways in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early life

Jessop was born in Devonport, Devon, the ...

had introduced a form of all-iron

edge rail

Wagonways (also spelt Waggonways), also known as horse-drawn railways and horse-drawn railroad consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam-powered railways. The terms plateway, tramway, dramway ...

and flanged wheels for an extension to the

Charnwood Forest Canal

The Charnwood Forest Canal, sometimes known as the "Forest Line of the Leicester Navigation", was opened between Thringstone and Nanpantan, with a further connection to Barrow Hill, near Worthington, in 1794

It marks the beginning of a period ...

at

Nanpantan

Nanpantan is a suburb in the Charnwood borough of Leicestershire, England. It is located in the south-west of the town of Loughborough, but the village is slightly separated from the main built-up area of Loughborough. It is also the site of ...

,

Loughborough

Loughborough ( ) is a market town in the Charnwood borough of Leicestershire, England, the seat of Charnwood Borough Council and Loughborough University. At the 2011 census the town's built-up area had a population of 59,932 , the second large ...

,

Leicestershire. In 1790, Jessop and his partner Outram began to manufacture edge-rails. Jessop became a partner in the Butterley Company in 1790. The first public edgeway (thus also first public railway) built was the

Lake Lock Rail Road

The Lake Lock Rail Road was an early, approximately long, horse drawn narrow gauge railway built near Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. The railway is recognised as the world's first public railway, though other railway schemes around the same ...

in 1796. Although the primary purpose of the line was to carry coal, it also carried passengers.

These two systems of constructing iron railways, the "L" plate-rail and the smooth edge-rail, continued to exist side by side into the early 19th century. The flanged wheel and edge-rail eventually proved its superiority and became the standard for railways.

Cast iron was not a satisfactory material for rails because it was brittle and broke under heavy loads. The wrought iron rail, invented by

John Birkinshaw

John Birkinshaw (1777-1842) was a 19th-century railway engineer from Bedlington, Northumberland noted for his invention of wrought iron rails in 1820 (patented on October 23, 1820).

Up to this point, rail systems had used either wooden rails, w ...

in 1820, solved these problems.

Wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

(usually simply referred to as "iron") was a

ductile

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile stres ...

material that could undergo considerable deformation before breaking, making it more suitable for iron rails. But wrought iron was expensive to produce until

Henry Cort

Henry Cort (c. 1740 – 23 May 1800) was an English ironware producer although formerly a Navy pay agent. During the Industrial Revolution in England, Cort began refining iron from pig iron to wrought iron (or bar iron) using innovative producti ...

patented the

puddling process in 1784. In 1783, Cort also patented the

rolling process, which was 15 times faster at consolidating and shaping iron than hammering. These processes greatly lowered the cost of producing iron and iron rails. The next important development in iron production was

hot blast

Hot blast refers to the preheating of air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. As this considerably reduced the fuel consumed, hot blast was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution. ...

developed by

James Beaumont Neilson

James Beaumont Neilson (22 June 1792 – 18 January 1865) was a Scottish inventor whose hot-blast process greatly increased the efficiency of smelting iron.

Life

He was the son of the engineer Walter Neilson, a millwright and later engin ...

(patented 1828), which considerably reduced the amount of

coke (fuel) or charcoal needed to produce

pig iron. Wrought iron was a soft material that contained slag or ''dross''. The softness and dross tended to make iron rails distort and delaminate and they typically lasted less than 10 years in use, and sometimes as little as one year under high traffic. All these developments in the production of iron eventually led to replacement of composite wood/iron rails with superior all-iron rails.

The introduction of the

Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation ...

, enabling steel to be made inexpensively, led to the era of great expansion of railways that began in the late 1860s. Steel rails lasted several times longer than iron.

Steel rails made heavier locomotives possible, allowing for longer trains and improving the productivity of railroads. The Bessemer process introduced nitrogen into the steel, which caused the steel to become brittle with age. The

open hearth furnace

An open-hearth furnace or open hearth furnace is any of several kinds of industrial Industrial furnace, furnace in which excess carbon and other impurities are burnt out of pig iron to Steelmaking, produce steel. Because steel is difficult to ma ...

began to replace the Bessemer process near the end of 19th century, improving the quality of steel and further reducing costs. Steel completely replaced the use of iron in rails, becoming standard for all railways.

Steam power introduced

James Watt, a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer, greatly improved the

steam engine of

Thomas Newcomen

Thomas Newcomen (; February 1664 – 5 August 1729) was an English inventor who created the atmospheric engine, the first practical fuel-burning engine in 1712. He was an ironmonger by trade and a Baptist lay preacher by calling.

He ...

, hitherto used to pump water out of mines. Watt developed a

reciprocating engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common fea ...

in 1769, capable of powering a wheel. Although the Watt engine powered cotton mills and a variety of machinery, it was a large

stationary engine. It could not be otherwise: the state of boiler technology necessitated the use of low pressure steam acting upon a vacuum in the cylinder; this required a separate

condenser and an

air pump

An air pump is a pump for pushing air. Examples include a bicycle pump, pumps that are used to aerate an aquarium or a pond via an airstone; a gas compressor used to power a pneumatic tool, air horn or pipe organ; a bellows used to encoura ...

. Nevertheless, as the construction of boilers improved, Watt investigated the use of high-pressure steam acting directly upon a piston. This raised the possibility of a smaller engine, that might be used to power a vehicle and he patented a design for a

steam locomotive in 1784. His employee

William Murdoch

William Murdoch (sometimes spelled Murdock) (21 August 1754 – 15 November 1839) was a Scottish engineer and inventor.

Murdoch was employed by the firm of Boulton & Watt and worked for them in Cornwall, as a steam engine erector for ten yea ...

produced a working model of a self-propelled steam carriage in that year.

The first full-scale working railway

steam locomotive was built in the United Kingdom in 1804 by

Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He w ...

, a British engineer born in

Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

. This used high-pressure steam to drive the engine by one power stroke. The transmission system employed a large

flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device which uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy; a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, as ...

to even out the action of the piston rod. On 21 February 1804, the world's first steam-powered railway journey took place when Trevithick's unnamed steam locomotive hauled a train along the tramway of the

Penydarren

: ''For Trevithick's Pen-y-darren locomotive, see Richard Trevithick.''

Penydarren is a community and electoral ward in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough in Wales.

Description

The area is most notable for being the site of a 1st-century Roman fort, ...

ironworks, near

Merthyr Tydfil in

South Wales. Trevithick later demonstrated a locomotive operating upon a piece of circular rail track in

Bloomsbury, London, the ''

Catch Me Who Can

''Catch Me Who Can'' was the fourth and last steam locomotive, steam railway locomotive created by the inventor and mining engineer Richard Trevithick. It was an evolution of three earlier locomotives which had been built for Coalbrookdale, Pe ...

'', but never got beyond the experimental stage with railway locomotives, not least because his engines were too heavy for the cast-iron plateway track then in use.

The first commercially successful steam locomotive was

Matthew Murray

Matthew Murray (1765 – 20 February 1826) was an English steam engine and machine tool manufacturer, who designed and built the first commercially viable steam locomotive, the twin cylinder ''Salamanca'' in 1812. He was an innovative design ...

's

rack

Rack or racks may refer to:

Storage and installation

* Amp rack, short for amplifier rack, a piece of furniture in which amplifiers are mounted

* Bicycle rack, a frame for storing bicycles when not in use

* Bustle rack, a type of storage bi ...

locomotive ''

Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

'' built for the

Middleton Railway

The Middleton Railway is the world's oldest continuously working railway, situated in the English city of Leeds. It was founded in 1758 and is now a heritage railway, run by volunteers from The Middleton Railway Trust Ltd. since 1960.

The rail ...

in

Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

in 1812. This twin-cylinder locomotive was not heavy enough to break the

edge-rails track and solved the problem of

adhesion

Adhesion is the tendency of dissimilar particles or surfaces to cling to one another ( cohesion refers to the tendency of similar or identical particles/surfaces to cling to one another).

The forces that cause adhesion and cohesion can b ...

by a

cog-wheel

A gear is a rotating circular machine part having cut teeth or, in the case of a cogwheel or gearwheel, inserted teeth (called ''cogs''), which mesh with another (compatible) toothed part to transmit (convert) torque and speed. The basic p ...

using teeth cast on the side of one of the rails. Thus it was also the first

rack railway

A rack railway (also rack-and-pinion railway, cog railway, or cogwheel railway) is a steep grade railway with a toothed rack rail, usually between the running rails. The trains are fitted with one or more cog wheels or pinions that mesh with th ...

.

This was followed in 1813 by the locomotive ''

Puffing Billy'' built by

Christopher Blackett

Christopher Blackett (1751 – 25 January 1829) owned the Northumberland colliery at Wylam that built ''Puffing Billy'', the first commercial adhesion steam locomotive. He was also the founding owner of ''The Globe'' newspaper in 1803.

Lif ...

and

William Hedley

William Hedley (13 July 1779 – 9 January 1843) was born in Newburn, near Newcastle upon Tyne. He was one of the leading industrial engineers of the early 19th century, and was instrumental in several major innovations in early railway devel ...

for the

Wylam

Wylam is a village and civil parish in the county of Northumberland. It is located about west of Newcastle upon Tyne.

It is famous for the being the birthplace of George Stephenson, one of the early railway pioneers. George Stephenson's Bir ...

Colliery Railway, the first successful locomotive running by

adhesion

Adhesion is the tendency of dissimilar particles or surfaces to cling to one another ( cohesion refers to the tendency of similar or identical particles/surfaces to cling to one another).

The forces that cause adhesion and cohesion can b ...

only. This was accomplished by the distribution of weight between a number of wheels. ''Puffing Billy'' is now on display in the

Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, industry and industrial machinery, etc. Modern trends in ...

in London, making it the oldest locomotive in existence.

In 1814,

George Stephenson

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was a British civil engineer and mechanical engineer. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians

In the history of the United Kingdom and the ...

, inspired by the early locomotives of Trevithick, Murray and Hedley, persuaded the manager of the

Killingworth

Killingworth, formerly Killingworth Township, is a town in North Tyneside, England.

Killingworth was built as a planned town in the 1960s, next to Killingworth Village, which existed for centuries before the Township. Other nearby towns an ...

colliery

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

where he worked to allow him to build a

steam-powered

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tr ...

machine. Stephenson played a pivotal role in the development and widespread adoption of the steam locomotive. His designs considerably improved on the work of the earlier pioneers. He built the locomotive ''

Blücher'', also a successful

flange

A flange is a protruded ridge, lip or rim, either external or internal, that serves to increase strength (as the flange of an iron beam such as an I-beam or a T-beam); for easy attachment/transfer of contact force with another object (as the f ...

d-wheel adhesion locomotive. In 1825, he built the locomotive ''

Locomotion

Locomotion means the act or ability of something to transport or move itself from place to place.

Locomotion may refer to:

Motion

* Motion (physics)

* Robot locomotion, of man-made devices

By environment

* Aquatic locomotion

* Flight

* Locomo ...

'' for the

Stockton and Darlington Railway in the north east of England, which became the first public steam railway in the world, although it used both horse power and steam power on different runs. In 1829, he built the locomotive ''

Rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

'', which entered in and won the

Rainhill Trials. This success led to Stephenson establishing his company as the pre-eminent builder of steam locomotives for railways in Great Britain and Ireland, the United States, and much of Europe.

The first public railway which used only steam locomotives, all the time, was

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) was the first inter-city railway in the world. It opened on 15 September 1830 between the Lancashire towns of Liverpool and Manchester in England. It was also the first railway to rely exclusively ...

, built in 1830.

Steam power continued to be the dominant power system in railways around the world for more than a century.

Electric power introduced

The first known electric locomotive was built in 1837 by chemist

Robert Davidson of

Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

in Scotland, and it was powered by

galvanic cell

A galvanic cell or voltaic cell, named after the scientists Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta, respectively, is an electrochemical cell in which an electric current is generated from spontaneous Oxidation-Reduction reactions. A common apparatus ...

s (batteries). Thus it was also the earliest battery electric locomotive. Davidson later built a larger locomotive named ''Galvani'', exhibited at the

Royal Scottish Society of Arts

The Royal Scottish Society of Arts is a learned society in Scotland, dedicated to the study of science and technology. It was founded as The Society for the Encouragement of the Useful Arts in Scotland by Sir David Brewster in 1821 and dedicated ...

Exhibition in 1841. The seven-ton vehicle had two

direct-drive

A direct-drive mechanism is a mechanism design where the force or torque from a prime mover is transmitted directly to the effector device (such as the drive wheels of a vehicle) without involving any intermediate couplings such as a gear train o ...

reluctance motor

A reluctance motor is a type of electric motor that induces non-permanent magnetic poles on the ferromagnetic rotor. The rotor does not have any windings. It generates torque through magnetic reluctance.

Reluctance motor subtypes include synchr ...

s, with fixed electromagnets acting on iron bars attached to a wooden cylinder on each axle, and simple

commutators. It hauled a load of six tons at four miles per hour (6 kilometers per hour) for a distance of . It was tested on the

Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway

The Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway was authorised by Act of Parliament on 4 July 1838. It was opened to passenger traffic on 21 February 1842, between its Glasgow Queen Street railway station (sometimes referred to at first as Dundas Street) and ...

in September of the following year, but the limited power from batteries prevented its general use. It was destroyed by railway workers, who saw it as a threat to their job security.

[Renzo Pocaterra, ''Treni'', De Agostini, 2003]

Early experimentation with railway electrification was undertaken by the Ukrainian engineer

Fyodor Pirotsky

Fyodor Apollonovich Pirotsky or Fedir Apollonovych Pirotskyy ( ukr, Федір Аполлонович Піроцький; russian: Фёдор Аполлонович Пироцкий; -) was a Ukrainian engineer and inventor of the world's first ra ...

. In 1875, he had electrically-powered railway cars run on

Miller's line, between

Sestroretsk

Sestroretsk (russian: Сестроре́цк; fi, Siestarjoki; sv, Systerbäck) is a municipal town in Kurortny District of the federal city of St. Petersburg, Russia, located on the shores of the Gulf of Finland, the Sestra River ...

and

Beloostrov

Beloostrov (russian: Белоо́стров; fi, Valkeasaari; ), from 1922 to World War II Krasnoostrov (russian: Красноо́стров, lit=Red Island, link=no), is a municipal settlement in Kurortny District of the federal city of St ...

. During September 1880, in St. Petersburg, Pirotsky put into operation an electric tram he had converted from a double-decker

horse tramway

A horsecar, horse-drawn tram, horse-drawn streetcar (U.S.), or horse-drawn railway (historical), is an animal-powered (usually horse) tram or streetcar.

Summary

The horse-drawn tram (horsecar) was an early form of public rail transport, wh ...

. Although Pirotsky's own tram project was taken no further, his experiment and work in the field did stimulate interest in electric trams globally.

Carl von Siemens met with Pirotsky and studied exhibits of his work carefully. The Siemens brothers (Carl and Werner) began commercial production of their own design of electric trams soon after, in 1881.

Werner von Siemens

Ernst Werner Siemens (von Siemens from 1888; ; ; 13 December 1816 – 6 December 1892) was a German electrical engineer, inventor and industrialist. Siemens's name has been adopted as the SI unit of electrical conductance, the siemens. He foun ...

demonstrated an electric railway in 1879 in Berlin. One of the world's first electric tram lines,

Gross-Lichterfelde Tramway

The Gross Lichterfelde Tramway was one of the world's first electric tramways ( Miller's line was electrified in 1875). It was built by the Siemens & Halske company in Lichterfelde, a suburb of Berlin, and went in service on 16 May 1881.

Ove ...

, opened in

Lichterfelde near

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, Germany, in 1881. It was built by Siemens. The tram ran on 180 Volt DC, which was supplied by running rails. In 1891 the track was equipped with an

overhead wire

An overhead line or overhead wire is an electrical cable that is used to transmit electrical energy to electric locomotives, trolleybuses or trams. It is known variously as:

* Overhead catenary

* Overhead contact system (OCS)

* Overhead equipm ...

and the line was extended to

Berlin-Lichterfelde West station

Berlin-Lichterfelde West (in German Bahnhof Berlin-Lichterfelde West) is a railway station in Lichterfelde West, within the district of Lichterfelde ( Steglitz-Zehlendorf) in Berlin, Germany. It is served by the Berlin S-Bahn and several local bus ...

. The

Volk's Electric Railway

Volk's Electric Railway (VER) is a narrow gauge heritage railway that runs along a length of the seafront of the English seaside resort of Brighton. It was built by Magnus Volk, the first section being completed in August 1883, and is the old ...

opened in 1883 in

Brighton, England. The railway is still operational, thus making it the oldest operational electric railway in the world. Also in 1883,

Mödling and Hinterbrühl Tram

Mödling and Hinterbrühl Tram or ''Mödling and Hinterbrühl Local Railway'' (German: ''Lokalbahn Mödling–Hinterbrühl'') was an electric tramway in Austria, running 4.5 km (2.8 mi) from Mödling to Hinterbrühl, in the southwest ...

opened near Vienna in Austria. It was the first tram line in the world in regular service powered from an overhead line. Five years later, in the

US electric

trolleys were pioneered in 1888 on the

Richmond Union Passenger Railway

The Richmond Union Passenger Railway, in Richmond, Virginia, was the first practical electric trolley (tram) system, and set the pattern for most subsequent electric trolley systems around the world. It is an IEEE milestone in engineering.

Th ...

, using equipment designed by

Frank J. Sprague

Frank Julian Sprague (July 25, 1857 in Milford, Connecticut – October 25, 1934) was an American inventor who contributed to the development of the electric motor, electric railways, and electric elevators. His contributions were especially ...

.

The first use of electrification on a main line was on a four-mile stretch of the

Baltimore Belt Line

The Baltimore Belt Line was constructed by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) in the early 1890s to connect the railroad's newly constructed line to Philadelphia and New York City/Jersey City with the rest of the railroad at Baltimore, Marylan ...

of the

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) in 1895 connecting the main portion of the B&O to the new line to

New York through a series of tunnels around the edges of Baltimore's downtown.

Electricity quickly became the power supply of choice for subways, abetted by the Sprague's invention of multiple-unit train control in 1897. By the early 1900s, most street railways were electrified.

The first practical

AC electric locomotive was designed by

Charles Brown, then working for

Oerlikon, Zürich. In 1891, Brown had demonstrated long-distance power transmission, using

three-phase AC, between a

hydro-electric plant

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and ...

at

Lauffen am Neckar

Lauffen am Neckar () or simply Lauffen is a town in the district of Heilbronn, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is on the river Neckar, southwest of Heilbronn. The town is famous as the birthplace of the poet Friedrich Hölderlin and for its qu ...

and

Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

West, a distance of 280 km. Using experience he had gained while working for

Jean Heilmann on steam-electric locomotive designs, Brown observed that

three-phase motors had a higher power-to-weight ratio than

DC motors and, because of the absence of a

commutator, were simpler to manufacture and maintain. However, they were much larger than the DC motors of the time and could not be mounted in underfloor

bogies: they could only be carried within locomotive bodies.

In 1894, Hungarian engineer

Kálmán Kandó

Kálmán Kandó de Egerfarmos et Sztregova (''egerfarmosi és sztregovai Kandó Kálmán''; 10 July 1869 – 13 January 1931) was a Hungarian engineer, the inventor of phase converter and a pioneer in the development of AC electric railway tract ...

developed a new type 3-phase asynchronous electric drive motors and generators for electric locomotives. Kandó's early 1894 designs were first applied in a short three-phase AC tramway in Evian-les-Bains (France), which was constructed between 1896 and 1898.

In 1896, Oerlikon installed the first commercial example of the system on the

Lugano Tramway. Each 30-tonne locomotive had two motors run by three-phase 750 V 40 Hz fed from double overhead lines. Three-phase motors run at constant speed and provide

regenerative braking

Regenerative braking is an energy recovery mechanism that slows down a moving vehicle or object by converting its kinetic energy into a form that can be either used immediately or stored until needed. In this mechanism, the electric traction mo ...

, and are well suited to steeply graded routes, and the first main-line three-phase locomotives were supplied by Brown (by then in partnership with

Walter Boveri

Walter Boveri (born 21 February 1865 in Bamberg, Bavaria, died 28 October 1924 in Baden, Switzerland) was a Swiss-German industrialist and co-founder of the global electrical engineering group Brown, Boveri & Cie. (BBC).

Biography

Boveri's anc ...

) in 1899 on the 40 km

Burgdorf–Thun line, Switzerland.

Italian railways were the first in the world to introduce electric traction for the entire length of a main line rather than just a short stretch. The 106 km

Valtellina

Valtellina or the Valtelline (occasionally spelled as two words in English: Val Telline; rm, Vuclina (); lmo, Valtelina or ; german: Veltlin; it, Valtellina) is a valley in the Lombardy region of northern Italy, bordering Switzerland. Toda ...

line was opened on 4 September 1902, designed by Kandó and a team from the Ganz works.

The electrical system was three-phase at 3 kV 15 Hz. In 1918, Kandó invented and developed the

rotary phase converter

A rotary phase converter, abbreviated RPC, is an electrical machine that converts power from one polyphase system to another, converting through rotary motion. Typically, single-phase electric power is used to produce three-phase electric power ...

, enabling electric locomotives to use three-phase motors whilst supplied via a single overhead wire, carrying the simple industrial frequency (50 Hz) single phase AC of the high voltage national networks.

An important contribution to the wider adoption of AC traction came from SNCF of France after World War II. The company conducted trials at 50 Hz, and established it as a standard. Following SNCF's successful trials, 50 Hz (now also called industrial frequency) was adopted as standard for main lines across the world.

Diesel power introduced

Earliest recorded examples of an internal combustion engine for railway use included a prototype designed by

William Dent Priestman

William Dent Priestman (23 August 1847 7 September 1936), born near Kingston upon Hull was a Quaker and engineering pioneer, inventor of the Priestman Oil Engine, and co-founder with his brother Samuel of the Priestman Brothers engineering com ...

, which was examined by

Sir William Thomson

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow for 53 years, he did important ...

in 1888 who described it as a "

riestmans' petroleum engine.. mounted upon a truck which is worked on a temporary line of rails to show the adaptation of a petroleum engine for locomotive purposes.". In 1894, a two axle machine built by

Priestman Brothers

Priestman Brothers was an engineering company based in Kingston upon Hull, England that manufactured diggers, dredgers, cranes and other industrial machinery. In the later 1800s the company also produced the Priestman Oil Engine, an early desi ...

was used on the

Hull Docks

The Port of Hull is a port at the confluence of the River Hull and the Humber Estuary in Kingston upon Hull, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

Seaborne trade at the port can be traced to at least the 13th century, originally con ...

.

In 1906,

Rudolf Diesel

Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel (, ; 18 March 1858 – 29 September 1913) was a German inventor and mechanical engineer who is famous for having invented the diesel engine, which burns diesel fuel; both are named after him.

Early life and educat ...

,

Adolf Klose

Adolf Klose (21 May 1844 – 2 September 1923) was the chief engineer of the Royal Württemberg State Railways in southern Germany from June 1885 to 1896.

Klose was born in Bernstadt auf dem Eigen, in Saxony. Before his taking up his post in St ...

and the steam and diesel engine manufacturer

Gebrüder Sulzer founded Diesel-Sulzer-Klose GmbH to manufacture diesel-powered locomotives. Sulzer had been manufacturing diesel engines since 1898. The Prussian State Railways ordered a diesel locomotive from the company in 1909. The world's first diesel-powered locomotive was operated in the summer of 1912 on the

Winterthur–Romanshorn railway

The Winterthur–Romanshorn railway, also known in German as the ''Thurtallinie'' ("Thur valley line"), is a Swiss railway line and was built as part of the railway between Zürich and Lake Constance (Bodensee). It connects Winterthur with Romans ...

in Switzerland, but was not a commercial success. The locomotive weight was 95 tonnes and the power was 883 kW with a maximum speed of 100 km/h. Small numbers of prototype diesel locomotives were produced in a number of countries through the mid-1920s.

A significant breakthrough occurred in 1914, when

Hermann Lemp, a

General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable en ...

electrical engineer, developed and patented a reliable

direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or eve ...

electrical control system (subsequent improvements were also patented by Lemp). Lemp's design used a single lever to control both engine and generator in a coordinated fashion, and was the

prototype for all

diesel–electric locomotive

A diesel locomotive is a type of railway locomotive in which the prime mover is a diesel engine. Several types of diesel locomotives have been developed, differing mainly in the means by which mechanical power is conveyed to the driving wheels ...

control systems. In 1914, world's first functional diesel–electric railcars were produced for the ''Königlich-Sächsische Staatseisenbahnen'' (

Royal Saxon State Railways

The Royal Saxon State Railways (german: Königlich Sächsische Staatseisenbahnen) were the state-owned railways operating in the Kingdom of Saxony from 1869 to 1918. From 1918 until their merger into the Deutsche Reichsbahn the title 'Royal' was ...

) by

Waggonfabrik Rastatt

( en, Rastatt Coach Factory) is a German public-limited company based in Rastatt in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwestern Germany. Its chief products are tramway vehicles and railway coaches and wagons. The firm was founded in and b ...

with electric equipment from

Brown, Boveri & Cie

Brown, Boveri & Cie. (Brown, Boveri & Company; BBC) was a Swiss group of electrical engineering companies.

It was founded in Zürich, in 1891 by Charles Eugene Lancelot Brown and Walter Boveri who worked at the Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon. In 1 ...

and diesel engines from

Swiss Sulzer AG

Sulzer Ltd. is a Swiss industrial engineering and manufacturing firm, founded by Salomon Sulzer-Bernet in 1775 and established as Sulzer Brothers Ltd. (Gebrüder Sulzer) in 1834 in Winterthur, Switzerland. Today it is a publicly traded company w ...

. They were classified as . The first regular use of diesel–electric locomotives was in

switching (shunter) applications. General Electric produced several small switching locomotives in the 1930s (the famous "

44-tonner" switcher was introduced in 1940) Westinghouse Electric and Baldwin collaborated to build switching locomotives starting in 1929.

In 1929, the

Canadian National Railways became the first North American railway to use diesels in mainline service with two units, 9000 and 9001, from Westinghouse.

High-speed rail

The first electrified

high-speed rail Tōkaidō Shinkansen (series 0) was introduced in 1964 between

Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

and

Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of ...

in Japan. Since then

high-speed rail transport, functioning at speeds up and above 300 km/h(186.4 m/h), has been built in Japan, Spain, France, Germany, Italy,

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

, the People's Republic of China, the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

,

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eas ...

,

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

and the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. The construction of many of these lines has resulted in the dramatic decline of short haul flights and automotive traffic between connected cities, such as the London–Paris–Brussels corridor, Madrid–Barcelona, Milan–Rome–Naples, as well as many other major lines.

High-speed trains normally operate on

standard gauge tracks of

continuously welded rail

A railway track (British English and UIC terminology) or railroad track (American English), also known as permanent way or simply track, is the structure on a railway or railroad consisting of the rails, fasteners, railroad ties (sleepers, ...

on

grade-separated right-of-way

Right of way is the legal right, established by grant from a landowner or long usage (i.e. by prescription), to pass along a specific route through property belonging to another.

A similar ''right of access'' also exists on land held by a gov ...

that incorporates a large

turning radius

The turning diameter of a vehicle is the minimum diameter (or "width") of available space required for that vehicle to make a circular turn (i.e. U-turn). The term thus refers to a theoretical minimal circle in which for example an aeroplane, a g ...

in its design. While high-speed rail is most often designed for passenger travel, some high-speed systems also offer freight service.

Hydrogen power introduced

Alstom Coradia Lint

The Alstom Coradia LINT is an articulated railcar manufactured by Alstom since 1999, offered in diesel and hydrogen fuel models.

The acronym ''LINT'' is short for the German ''"leichter innovativer Nahverkehrstriebwagen"'' (light innovative local ...

hydrogen-powered train entered service in

Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony (german: Niedersachsen ; nds, Neddersassen; stq, Läichsaksen) is a German state (') in northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with , and fourth-largest in population (8 million in 2021) among the 16 ...

,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

in 2018.

History by country

Europe

In recent years deregulation has been a major topic across Europe.

Belgium

Belgium took the lead in the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

on the Continent starting in the 1820s. It provided an ideal model for showing the value of the railways for speeding the industrial revolution. After splitting from the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

in 1830, the new country decided to stimulate industry. It planned and funded a simple cross-shaped system that connected the major cities, ports and mining areas and linked to neighboring countries. Unusually, the Belgian state became a major contributor to early rail development and championed the creation of a national network with no duplication of lines. Belgium thus became the railway center of the region.

The system was built along British lines, often with British engineers doing the planning. Profits were low but the infrastructure necessary for rapid industrial growth was put in place. The first railway in Belgium, running from northern

Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

to

Mechelen, was completed in May 1835.

Britain

= Early developments

=

The earliest railway in Britain was a

wagonway

Wagonways (also spelt Waggonways), also known as horse-drawn railways and horse-drawn railroad consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam-powered railways. The terms plateway, tramway, dramway ...

system, a horse drawn wooden rail system, used by German miners at

Caldbeck

Caldbeck is a village in Cumbria, England, historically within Cumberland, it is situated within the Lake District National Park. The village had 714 inhabitants according to the census of 2001.

Caldbeck is closely associated with neighbouring ...

,

Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. C ...

, England, perhaps from the 1560s.

A wagonway was built at

Prescot

Prescot is a town and civil parish within the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley in Merseyside, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, it lies about to the east of Liverpool city centre. At the 2001 Census, the c ...

, near

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

, sometime around 1600, possibly as early as 1594. Owned by Philip Layton, the line carried coal from a pit near Prescot Hall to a terminus about half a mile away.

On 26 July 1803, Jessop opened the

Surrey Iron Railway

The Surrey Iron Railway (SIR) was a horse-drawn plateway that linked Wandsworth and Croydon via Mitcham, all then in Surrey but now suburbs of south London, in England. It was established by Act of Parliament in 1801, and opened partly in 1802 ...

, south of London erroneously considered first railway in Britain, also a horse-drawn one. It was not a railway in the modern sense of the word, as it functioned like a

turnpike road. There were no official services, as anyone could bring a vehicle on the railway by paying a toll.

The oldest railway in continuous use is the

Tanfield Railway

The Tanfield Railway is a heritage railway in Gateshead and County Durham, England. Running on part of a former horse-drawn colliery wooden waggonway, later rope & horse, lastly rope & loco railway. It operates preserved industrial stea ...

in County Durham, England. This began life in 1725 as a wooden waggonway worked with horse power and developed by private coal owners and included the construction of the

Causey Arch

The Causey Arch is a bridge near Stanley in County Durham, northern England. It is the oldest surviving single-arch railway bridge in the world, and a key element of the industrial heritage of England. It carried an early wagonway (horse-draw ...

, the world's oldest purpose built railway bridge. By the mid 19th century it had converted to standard gauge track and steam locomotive power. It continues in operation as a heritage line. The

Middleton Railway

The Middleton Railway is the world's oldest continuously working railway, situated in the English city of Leeds. It was founded in 1758 and is now a heritage railway, run by volunteers from The Middleton Railway Trust Ltd. since 1960.

The rail ...

in

Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

, opened in 1758, is also still in use as a heritage line and began using steam locomotive power in 1812 before reverting to horsepower and then upgrading to standard gauge. In 1764, the first railway in the Americas was built in

Lewiston, New York

Lewiston is a town in Niagara County, New York, United States. The population was 15,944 at the 2020 census. The town and its contained village are named after Morgan Lewis, a governor of New York.

The Town of Lewiston is on the western bord ...

.

[

The first passenger ]Horsecar

A horsecar, horse-drawn tram, horse-drawn streetcar (U.S.), or horse-drawn railway (historical), is an animal-powered (usually horse) tram or streetcar.

Summary

The horse-drawn tram (horsecar) was an early form of public rail transport, w ...

or tram

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport are ...

, Swansea and Mumbles Railway

The Swansea and Mumbles Railway was the venue for the world's first passenger horsecar railway service, located in Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom.

Originally built under an Act of Parliament of 1804 to move limestone from the quarries of Mum ...

was opened between Swansea and Mumbles

Mumbles ( cy, Mwmbwls) is a headland sited on the western edge of Swansea Bay on the southern coast of Wales.

Toponym

Mumbles has been noted for its unusual place name. The headland is thought by some to have been named by French sailors, ...

in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

in 1807.Oliver Evans

Oliver Evans (September 13, 1755 – April 15, 1819) was an American inventor, engineer and businessman born in rural Delaware and later rooted commercially in Philadelphia. He was one of the first Americans building steam engines and an advoca ...

, an American engineer and inventor, published his vision of what steam railways could become, with cities and towns linked by a network of long distance railways plied by speedy locomotives, greatly speeding up personal travel and goods transport. Evans specified that there should be separate sets of parallel tracks for trains going in different directions. However, conditions in the infant United States did not enable his vision to take hold. This vision had its counterpart in Britain, where it proved to be far more influential. William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

, a rich and influential surveyor and land agent, was inspired by the development of the steam locomotive to suggest a national network of railways. It seems likelyRichard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He w ...

's steam locomotive ''Catch me who can

''Catch Me Who Can'' was the fourth and last steam locomotive, steam railway locomotive created by the inventor and mining engineer Richard Trevithick. It was an evolution of three earlier locomotives which had been built for Coalbrookdale, Pe ...

'' in London; certainly at this time he began to consider the long-term development of this means of transport. He proposed a number of projects that later came to fruition and is credited with carrying out a survey of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) was the first inter-city railway in the world. It opened on 15 September 1830 between the Lancashire towns of Liverpool and Manchester in England. It was also the first railway to rely exclusively ...

. Unfortunately he became bankrupt and his schemes were taken over by George Stephenson and others. However, he is credited by many historians with the title of "Father of the Railway".rolled

Rolling is a Motion (physics)#Types of motion, type of motion that combines rotation (commonly, of an Axial symmetry, axially symmetric object) and Translation (geometry), translation of that object with respect to a surface (either one or the ot ...

wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

, produced at Bedlington Ironworks

Bedlington Ironworks, in Blyth Dene, Northumberland, England, operated between 1736 and 1867. It is most remembered as the place where wrought iron rails were invented by John Birkinshaw in 1820, which triggered the railway age, with their fir ...

in Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

. Such rails were stronger. This railway linked the coal field of Durham with the towns of Darlington and the port of Stockton-on-Tees and was intended to enable local collieries (which were connected to the line by short branches) to transport their coal to the docks. As this would constitute the bulk of the traffic, the company took the important step of offering to haul the colliery wagons or chaldrons by locomotive power, something that required a scheduled or timetabled service of trains. However, the line also functioned as a toll railway, on which private horse-drawn wagons could be carried. This hybrid of a system (which also included, at one stage, a horse-drawn passenger traffic when sufficient locomotives weren't available) could not last and within a few years, traffic was restricted to timetabled trains. (However, the tradition of private owned wagons continued on railways in Britain until the 1960s.). The S&DRs chief engineer Timothy Hackworth

Timothy Hackworth (22 December 1786 – 7 July 1850) was an English steam locomotive engineer who lived in Shildon, County Durham, England and was the first locomotive superintendent of the Stockton and Darlington Railway.

Youth and early wor ...

under the guidance of its principal funder Edward Pease, hosted visiting engineers from the USA, Prussia and France and shared experience and learning on how to build and run a railway so that by 1830 railways were being built in several locations across the UK, USA and Europe. Trained engineers and workers from the S&DR went on to help develop several other lines elsewhere including the Liverpool and Manchester of 1830, the next step forward in railway development.

The success of the Stockton and Darlington encouraged the rich investors in the rapidly industrialising

The success of the Stockton and Darlington encouraged the rich investors in the rapidly industrialising North West of England

North West England is one of nine official regions of England and consists of the ceremonial counties of England, administrative counties of Cheshire, Cumbria, Greater Manchester, Lancashire and Merseyside. The North West had a population of ...

to embark upon a project to link the rich cotton manufacturing town of Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

with the thriving port of Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) was the first inter-city railway in the world. It opened on 15 September 1830 between the Lancashire towns of Liverpool and Manchester in England. It was also the first railway to rely exclusively ...

was the first modern railway, in that both the goods and passenger traffic were operated by scheduled or timetabled locomotive hauled trains. When it was built, there was serious doubt that locomotives could maintain a regular service over the distance involved. A widely reported competition was held in 1829 called the Rainhill Trials, to find the most suitable steam engine to haul the trains. A number of locomotives were entered, including ''Novelty

Novelty (derived from Latin word ''novus'' for "new") is the quality of being new, or following from that, of being striking, original or unusual. Novelty may be the shared experience of a new cultural phenomenon or the subjective perception of an ...

'', ''Perseverance

Perseverance may refer to:

Behaviour

* Psychological resilience

* Perseverance of the saints, a Protestant Christian teaching

* Assurance (theology)

Geography

* Perseverance, Queensland, a locality in Australia

* Perseverance Island, Seychelles

...

'' and ''Sans Pareil

''Sans Pareil'' is a steam locomotive built by Timothy Hackworth which took part in the 1829 Rainhill Trials on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, held to select a builder of locomotives. The name is French and means 'peerless' or 'with ...

''. The winner was Stephenson's Rocket, which steamed better because of its multi-tubular boiler (suggested by Henry Booth

Henry Booth (4 April 1788 – 28 March 1869) was a British corn merchant, businessman and engineer particularly known as one of the key people behind the construction and management of the pioneering Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&M), the ...

, a director of the railway company).

The promoters were mainly interested in goods traffic, but after the line opened on 15 September 1830, they were surprised to find that passenger traffic was just as remunerative. The success of the Liverpool and Manchester railway added to the influence of the S&DR in the development of railways elsewhere in Britain and abroad. The company hosted many visiting deputations from other railway projects and many railwaymen received their early training and experience upon this line. The Liverpool and Manchester line was, however, only long. The world's first trunk line can be said to be the Grand Junction Railway

The Grand Junction Railway (GJR) was an early railway company in the United Kingdom, which existed between 1833 and 1846 when it was amalgamated with other railways to form the London and North Western Railway. The line built by the company w ...

, opening in 1837 and linking a midpoint on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway with Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

, via Crewe, Stafford and Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunians ...

.

= Further development

=

The earliest locomotives in revenue service were small four-wheeled ones similar to the Rocket. However, the inclined cylinders caused the engine to rock, so they first became horizontal and then, in his "Planet" design, were mounted inside the frames. While this improved stability, the "crank axles" were extremely prone to breakage. Greater speed was achieved by larger driving wheels at expense of a tendency for wheel slip when starting. Greater tractive effort was obtained by smaller wheels coupled together, but speed was limited by the fragility of the cast iron connecting rods. Hence, from the beginning, there was a distinction between the light fast passenger locomotive and the slower more powerful goods engine. Edward Bury

Edward Bury (22 October 1794 – 25 November 1858) was an English locomotive manufacturer. Born in Salford, Lancashire, he was the son of a timber merchant and was educated at Chester.

Career

By 1823 he was a partner in Gregson and Bury's ste ...

, in particular, refined this design and the so-called "Bury Pattern" was popular for a number of years, particularly on the London and Birmingham.

Meanwhile, by 1840, Stephenson had produced larger, more stable, engines in the form of the 2-2-2

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 2-2-2 represents the wheel arrangement of two leading wheels on one axle, two powered driving wheels on one axle, and two trailing wheels on one axle. The wheel arrangement bo ...

"Patentee" and six-coupled goods engines. Locomotives were travelling longer distances and being worked more extensively. The North Midland Railway

The North Midland Railway was a British railway company, which opened its line from Derby to Rotherham (Masbrough) and Leeds in 1840.

At Derby, it connected with the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway and the Midland Counties Railway at wha ...

expressed their concern to Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS HFRSE FRSA DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of his father ...

who was, at that time, their general manager, about the effect of heat on their fireboxes. After some experiments, he patented his so-called Long Boiler design. These became a new standard and similar designs were produced by other manufacturers, particularly Sharp Brothers whose engines became known affectionately as "Sharpies".

The longer wheelbase for the longer boiler produced problems in cornering. For his six-coupled engines, Stephenson removed the flanges from the centre pair of wheels. For his express engines, he shifted the trailing wheel to the front in the 4-2-0

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, represents the wheel arrangement of four leading wheels on two axles, two powered driving wheels on one axle and no trailing wheels. This type of locomotive is often called a ...

formation, as in his "Great A". There were other problems: the firebox was restricted in size or had to be mounted behind the wheels; and for improved stability most engineers believed that the centre of gravity should be kept low.

The most extreme outcome of this was the Crampton locomotive

A Crampton locomotive is a type of steam locomotive designed by Thomas Russell Crampton and built by various firms from 1846. The main British builders were Tulk and Ley and Robert Stephenson and Company.

Notable features were a low boiler and l ...

which mounted the driving wheels behind the firebox and could be made very large in diameter. These achieved the hitherto unheard of speed of but were very prone to wheelslip. With their long wheelbase, they were unsuccessful on Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

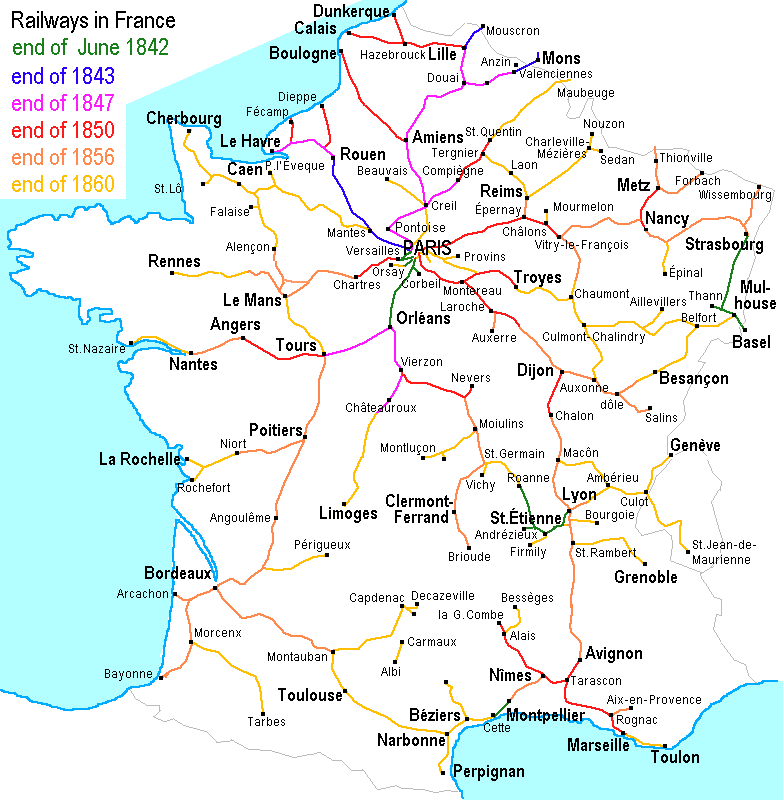

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...