History of liberalism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Isolated strands of liberal thought had existed in

Isolated strands of liberal thought had existed in

Isolated strands of liberal thought that had existed in

Isolated strands of liberal thought that had existed in

A prominent example of a monarch who took the Enlightenment project seriously was

A prominent example of a monarch who took the Enlightenment project seriously was

In contrast to England, the French experience in the 18th century was characterized by the perpetuation of

In contrast to England, the French experience in the 18th century was characterized by the perpetuation of

Political tension between England and its

Political tension between England and its

Historians widely regard the French Revolution as one of the most important events in history.Frey, Foreword. The Revolution is often seen as marking the "dawn of the modern era",Frey, Preface. and its convulsions are widely associated with "the triumph of liberalism".Ros, p. 11.

Four years into the French Revolution, German writer

Historians widely regard the French Revolution as one of the most important events in history.Frey, Foreword. The Revolution is often seen as marking the "dawn of the modern era",Frey, Preface. and its convulsions are widely associated with "the triumph of liberalism".Ros, p. 11.

Four years into the French Revolution, German writer  During the

During the

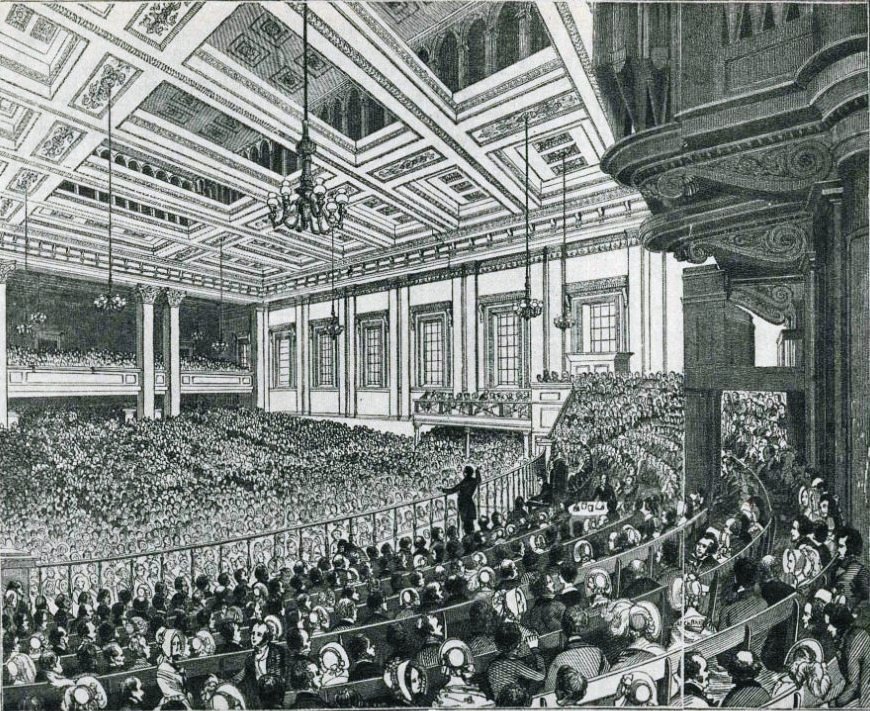

The radical liberal movement began in the 1790s in England and concentrated on parliamentary and electoral reform, emphasizing

The radical liberal movement began in the 1790s in England and concentrated on parliamentary and electoral reform, emphasizing

Commitment to ''

Commitment to ''

The primary intellectual influences on 19th century liberal trends were those of

The primary intellectual influences on 19th century liberal trends were those of  By the end of the 19th century, the principles of classical liberalism were being increasingly challenged by downturns in economic growth, a growing perception of the evils of poverty, unemployment and relative deprivation present within modern industrial cities and the agitation of

By the end of the 19th century, the principles of classical liberalism were being increasingly challenged by downturns in economic growth, a growing perception of the evils of poverty, unemployment and relative deprivation present within modern industrial cities and the agitation of

Green's definition of

Green's definition of

The worldwide

The worldwide  Meanwhile, the definitive liberal response to the Great Depression was given by the British economist

Meanwhile, the definitive liberal response to the Great Depression was given by the British economist

In the Middle East and the Ottoman Empire the effect of liberalism was significant. During the 19th century, Arab, Ottoman, and Persian intellectuals visited Europe to study and learn about Western literature, science and liberal ideas. This led them to ask themselves about their countries' underdevelopment and concluded that they needed to promote constitutionalism, development, and liberal values to modernize their societies. At the same time, the increasing European presence in the Middle East and the stagnation of the region encouraged some Middle Eastern leaders, including

In the Middle East and the Ottoman Empire the effect of liberalism was significant. During the 19th century, Arab, Ottoman, and Persian intellectuals visited Europe to study and learn about Western literature, science and liberal ideas. This led them to ask themselves about their countries' underdevelopment and concluded that they needed to promote constitutionalism, development, and liberal values to modernize their societies. At the same time, the increasing European presence in the Middle East and the stagnation of the region encouraged some Middle Eastern leaders, including  The emerging internal financial and diplomatic crises of 1875–1876 allowed the Young Ottomans their defining moment, when Sultan Abdülhamid II appointed liberal-minded

The emerging internal financial and diplomatic crises of 1875–1876 allowed the Young Ottomans their defining moment, when Sultan Abdülhamid II appointed liberal-minded  In 1949, the

In 1949, the

The liberal and conservative struggles in Spain also replicated themselves in

The liberal and conservative struggles in Spain also replicated themselves in

In the United States, modern liberalism traces its history to the popular presidency of

In the United States, modern liberalism traces its history to the popular presidency of  In the late 20th century, a conservative backlash against the kind of liberalism championed by Roosevelt and Kennedy developed in the

In the late 20th century, a conservative backlash against the kind of liberalism championed by Roosevelt and Kennedy developed in the

In Spain, the '' Liberales'', the first group to use the ''liberal'' label in a political context, fought for the implementation of the 1812 Constitution for decades—overthrowing the monarchy in 1820 as part of the '' Trienio Liberal'' and defeating the conservative

In Spain, the '' Liberales'', the first group to use the ''liberal'' label in a political context, fought for the implementation of the 1812 Constitution for decades—overthrowing the monarchy in 1820 as part of the '' Trienio Liberal'' and defeating the conservative  In the United Kingdom, the repeal of the

In the United Kingdom, the repeal of the  The

The

online

* Coker, Christopher. ''Twilight of the West''. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998. . * Colomer, Josep Maria. ''Great Empires, Small Nations''. New York: Routledge, 2007. . * Colton, Joel and Robert Roswell Palmer, Palmer, R.R. ''A History of the Modern World''. New York: McGraw Hill, Inc., 1995. . * Copleston, Frederick. ''A History of Philosophy: Volume V''. New York: Doubleday, 1959. . * Delaney, Tim. ''The march of unreason: science, democracy, and the new fundamentalism''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. . * Diamond, Larry. ''The Spirit of Democracy''. New York: Macmillan, 2008. . * Dobson, John. ''Bulls, Bears, Boom, and Bust''. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2006. . * * Dorrien, Gary. ''The making of American liberal theology''. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. . * Fawcett, Edmund. ''Liberalism: The Life of an Idea'' (2014). * Flamm, Michael and Steigerwald, David. ''Debating the 1960s: liberal, conservative, and radical perspectives''. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. . * Gallagher, Michael et al. ''Representative government in modern Europe''. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001. . * Godwin, Kenneth et al. ''School choice tradeoffs: liberty, equity, and diversity''. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002. . * Gould, Andrew. ''Origins of liberal dominance''. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999. . * Gray, John. ''Liberalism''. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995. . * Grigsby, Ellen. ''Analyzing Politics: An Introduction to Political Science''. Florence: Cengage Learning, 2008. . * Louis Hartz, Hartz, Louis. ''The liberal tradition in America''. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1955.

online

* Hafner, Danica and Ramet, Sabrina. ''Democratic transition in Slovenia: value transformation, education, and media''. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2006. . * Handelsman, Michael. ''Culture and Customs of Ecuador''. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2000. . * Heywood, Andrew. ''Political Ideologies: An Introduction''. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. . * Hodge, Carl. ''Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800–1944''. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. . * Jensen, Pamela Grande. ''Finding a new feminism: rethinking the woman question for liberal democracy''. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1996. . * Karatnycky, Adrian et al. ''Nations in transit, 2001''. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2001. . * Karatnycky, Adrian. ''Freedom in the World''. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2000. . * Linda K. Kerber, Kerber, Linda. ''The Republican Mother''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976. * Kirchner, Emil. ''Liberal parties in Western Europe''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. . * Knoop, Todd. ''Recessions and Depressions'' Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004. . * Lightfoot, Simon. ''Europeanizing social democracy?: the rise of the Party of European Socialists. New York: Routledge, 2005. . * Mackenzie, G. Calvin and Weisbrot, Robert. ''The liberal hour: Washington and the politics of change in the 1960s''. New York: Penguin Group, 2008. . * Manent, Pierre and Seigel, Jerrold. ''An Intellectual History of Liberalism''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996. . * Mazower, Mark. ''Dark Continent''. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. . * Monsma, Stephen and Soper, J. Christopher. ''The Challenge of Pluralism: Church and State in Five Democracies''. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. . * Peerenboom, Randall. ''China modernizes''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. . * Perry, Marvin et al. ''Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society''. Florence, KY: Cengage Learning, 2008. . * Pierson, Paul. ''The New Politics of the Welfare State''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. . * Riff, Michael. ''Dictionary of modern political ideologies''. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990. . * John Roberts (historian), Roberts, J.M. ''The Penguin History of the World''. New York: Penguin Group, 1992. . * Ros, Agustin. ''Profits for all?: the cost and benefits of employee ownership''. New York: Nova Publishers, 2001. . * Ryan, Alan. ''The Making of Modern Liberalism'' (Princeton UP, 2012). * * Shaw, G. K. ''Keynesian Economics: The Permanent Revolution''. Aldershot, England: Edward Elgar Publishing Company, 1988. . * Sinclair, Timothy. ''Global governance: critical concepts in political science''. Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 2004. . * Song, Robert. ''Christianity and Liberal Society''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. . * Stacy, Lee. ''Mexico and the United States''. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2002. . * Steindl, Frank. ''Understanding Economic Recovery in the 1930s''. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004. . * Susser, Bernard. ''Political ideology in the modern world''. Upper Saddle River: Allyn and Bacon, 1995. . * Van Schie, P. G. C. and Voermann, Gerrit. ''The dividing line between success and failure: a comparison of Liberalism in the Netherlands and Germany in the 19th and 20th Centuries''. Berlin: LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2006. . * Various authors. ''Countries of the World & Their Leaders Yearbook 08, Volume 2''. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2007. . * * Alan Wolfe, Wolfe, Alan. ''The Future of Liberalism''. New York: Random House, Inc., 2009. . * Worell, Judith. ''Encyclopedia of women and gender, Volume I''. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001. . * Young, Shaun. ''Beyond Rawls: an analysis of the concept of political liberalism''. Lanham: University Press of America, 2002. . * Zvesper, John. ''Nature and liberty''. New York: Routledge, 1993. .

online

. * Wempe, Ben. ''T. H. Green's theory of positive freedom: from metaphysics to political theory''. Exeter: Imprint Academic, 2004. .

Liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

, the belief in freedom

Freedom is understood as either having the ability to act or change without constraint or to possess the power and resources to fulfill one's purposes unhindered. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving one ...

, equality, democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

and human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

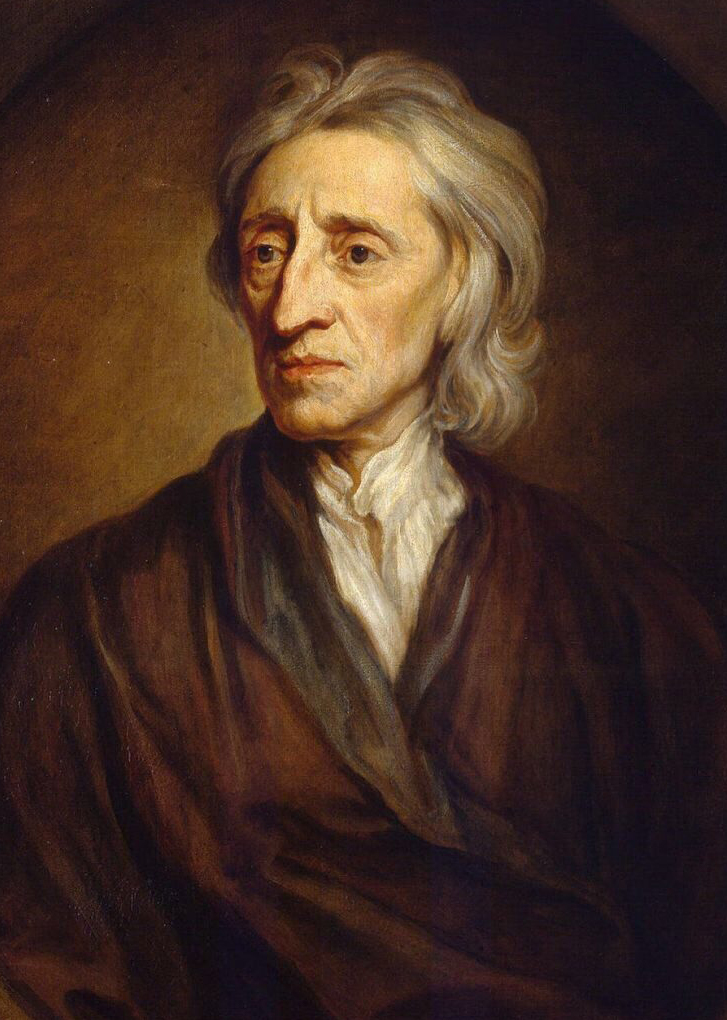

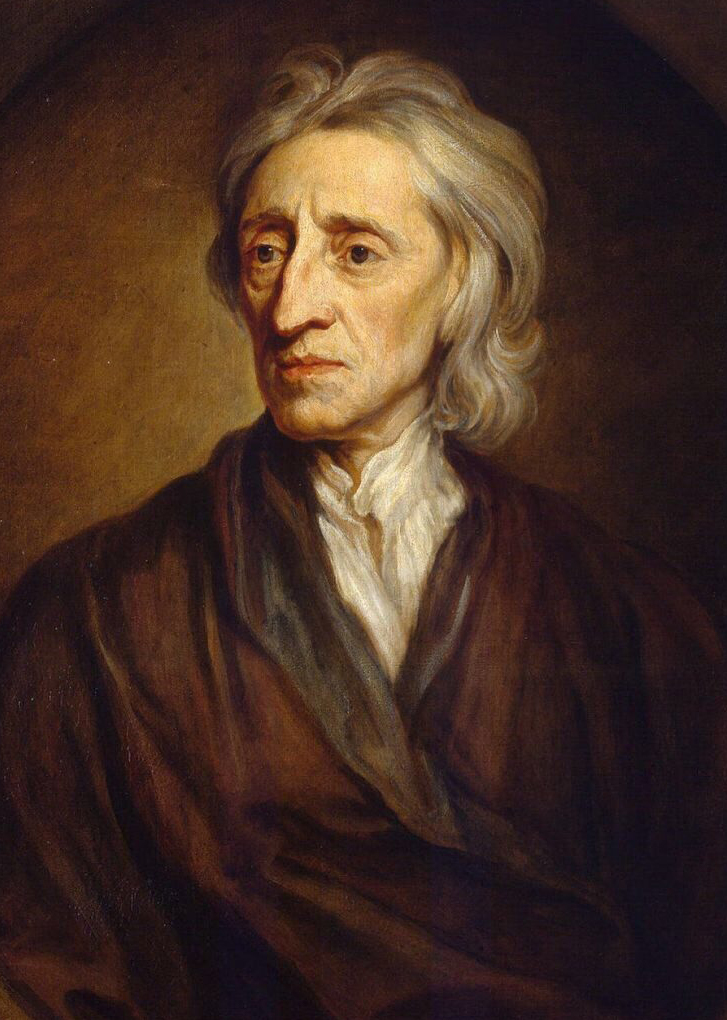

, is historically associated with thinkers such as John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

and Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

, and with constitutionally limiting the power of the monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

, affirming parliamentary supremacy, passing the Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pr ...

and establishing the principle of "consent of the governed

In political philosophy, the phrase consent of the governed refers to the idea that a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society over which that political pow ...

". The 1776 Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

founded the nascent republic on liberal principles without the encumbrance of hereditary aristocracy—the declaration stated that "all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, among these life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness". A few years later, the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

overthrew the hereditary aristocracy, with the slogan "liberty, equality, fraternity" and was the first state in history to grant universal male suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slo ...

. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

, first codified in 1789 in France, is a foundational document of both liberalism and human rights, itself based on the U.S. Declaration of Independence written in 1776. The intellectual progress of the Enlightenment, which questioned old traditions about societies and governments, eventually coalesced into powerful revolutionary movements that toppled what the French called the Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

, the belief in absolute monarchy and established religion, especially in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

.

William Henry of Orange in the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

and Lafayette in the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

used liberal philosophy to justify the armed overthrow of what they saw as tyrannical

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to r ...

rule. The 19th century saw liberal governments established in nations across Europe, South America and North America. In this period, the dominant ideological opponent of classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, e ...

was conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

, but liberalism later survived major ideological challenges from new opponents, such as fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and t ...

and communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

. Liberal government often adopted the economic beliefs espoused by Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

, John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

and others, which broadly emphasized the importance of free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

s and ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' governance, with a minimum of interference in trade.

During 19th and early 20th century in the Ottoman Empire and Middle East, liberalism influenced periods of reform such as the Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 187 ...

and Nahda

The Nahda ( ar, النهضة, translit=an-nahḍa, meaning "the Awakening"), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in Arabic-speaking regions of the Ottoman Empire, notably in Egypt, Leb ...

and the rise of secularism, constitutionalism and nationalism. These changes, along with other factors, helped to create a sense of crisis within Islam which continues to this day—this led to Islamic revivalism. During the 20th century, liberal ideas spread even further as liberal democracies

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

found themselves on the winning side in both world wars. In Europe and North America, the establishment of social liberalism

Social liberalism (german: Sozialliberalismus, es, socioliberalismo, nl, Sociaalliberalisme), also known as new liberalism in the United Kingdom, modern liberalism, or simply liberalism in the contemporary United States, left-liberalism ...

(often called simply "liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

" in the United States) became a key component in the expansion of the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

. Today, liberal parties

This article gives information on liberalism worldwide. It is an overview of parties that adhere to some form of liberalism and is therefore a list of liberal parties around the world.

Introduction

The definition of liberal party is highly deb ...

continue to wield power, control and influence throughout the world, but it still has challenges to overcome in Latin America, Africa and Asia. Later waves of modern liberal thought and struggle were strongly influenced by the need to expand civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

.Worell, p. 470. Liberals have advocated for gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing d ...

, marriage equality

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

and racial equality

Racial equality is a situation in which people of all races and ethnicities are treated in an egalitarian/equal manner. Racial equality occurs when institutions give individuals legal, moral, and political rights. In present-day Western societ ...

and a global social movement for civil rights in the 20th century achieved several objectives towards those goals.

Early history

Isolated strands of liberal thought had existed in

Isolated strands of liberal thought had existed in Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophy, philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre-Socratic p ...

since the Ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

and in Eastern philosophy

Eastern philosophy or Asian philosophy includes the various philosophies that originated in East and South Asia, including Chinese philosophy, Japanese philosophy, Korean philosophy, and Vietnamese philosophy; which are dominant in East Asia ...

since the Song

A song is a musical composition intended to be performed by the human voice. This is often done at distinct and fixed pitches (melodies) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs contain various forms, such as those including the repetiti ...

and Ming

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han pe ...

period, but the first major signs of liberal politics emerged in modern times. Many of the liberal concepts of Locke were foreshadowed in the radical ideas that were freely aired at the time. The pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a ...

eer Richard Overton wrote: "To every Individuall in nature, is given an individual property by nature, not to be invaded or usurped by any...; no man hath power over my rights and liberties, and I over no mans". These ideas were first unified as a distinct ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

by the English philosopher John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

, generally regarded as the father of modern liberalism. Locke developed the radical notion that government acquires consent from the governed, which has to be constantly present for a government to remain legitimate. His influential '' Two Treatises'' (1690), the foundational text of liberal ideology, outlined his major ideas. His insistence that lawful government did not have a supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

basis was a sharp break from previous theories of governance. Locke also defined the concept of the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular s ...

.Feldman, Noah (2005). ''Divided by God''. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 29. "It took John Locke to translate the demand for liberty of conscience into a systematic argument for distinguishing the realm of government from the realm of religion". Based on the social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is a theory or model that originated during the Age of Enlightenment and usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual.

Social ...

principle, Locke argued that there was a natural right to the liberty of conscience, which he argued must therefore remain protected from any government authority. He also formulated a general defence for religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

in his ''Letters Concerning Toleration''. Locke was influenced by the liberal ideas of John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and politica ...

, who was a staunch advocate of freedom in all its forms.

Milton argued for disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular s ...

as the only effective way of achieving broad toleration

Toleration is the allowing, permitting, or acceptance of an action, idea, object, or person which one dislikes or disagrees with. Political scientist Andrew R. Murphy explains that "We can improve our understanding by defining "toleration" as ...

. In his ''Areopagitica

''Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc'd Printing, to the Parlament of England'' is a 1644 prose polemic by the English poet, scholar, and polemical author John Milton opposing licensing and censorship. ''Areop ...

'', Milton provided one of the first arguments for the importance of freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

—"the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties". Algernon Sidney

Algernon Sidney or Sydney (15 January 1623 – 7 December 1683) was an English politician, republican political theorist and colonel. A member of the middle part of the Long Parliament and commissioner of the trial of King Charles I of Englan ...

was second only to John Locke in his influence on liberal political thought in eighteenth-century Britain and Colonial America, and was widely read and quoted by the Whig opposition during the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

. Sidney's argument that "free men always have the right to resist tyrannical government" was widely quoted by the Patriots at the time of American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

considered Sidney to have been one of the two primary sources for the Founding Fathers

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

' view of liberty. Sidney believed that absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

was a great political evil and his major work, ''Discourses Concerning Government'', was written during the Exclusion Crisis

The Exclusion Crisis ran from 1679 until 1681 in the reign of King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland. Three Exclusion bills sought to exclude the King's brother and heir presumptive, James, Duke of York, from the thrones of England, Sco ...

, as a response to Robert Filmer

Sir Robert Filmer (c. 1588 – 26 May 1653) was an English political theorist who defended the divine right of kings. His best known work, '' Patriarcha'', published posthumously in 1680, was the target of numerous Whig attempts at rebuttal ...

's ''Patriarcha'', a defence of divine right monarchy. Sidney firmly rejected the Filmer's reactionary principles and argued that the subjects of the monarch were entitled by right to share in the government through advice and counsel.

Glorious Revolution

Isolated strands of liberal thought that had existed in

Isolated strands of liberal thought that had existed in Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophy, philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre-Socratic p ...

since the Ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

began to coalesce at the time of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

. Disputes between the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

and King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

over political supremacy sparked a massive civil war in the 1640s, which culminated in Charles' execution and the establishment of a Republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

. In particular, the Levellers, a radical political movement of the period, published their manifesto ''Agreement of the People Agreement may refer to:

Agreements between people and organizations

* Gentlemen's agreement, not enforceable by law

* Trade agreement, between countries

* Consensus, a decision-making process

* Contract, enforceable in a court of law

** Meeting ...

'' which advocated popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

, an extended voting suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

, religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

and equality before the law

Equality before the law, also known as equality under the law, equality in the eyes of the law, legal equality, or legal egalitarianism, is the principle that all people must be equally protected by the law. The principle requires a systematic r ...

. The impact of liberal ideas steadily increased during the 17th century in England, culminating in the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688, which enshrined parliamentary sovereignty

Parliamentary sovereignty, also called parliamentary supremacy or legislative supremacy, is a concept in the constitutional law of some parliamentary democracies. It holds that the legislative body has absolute sovereignty and is supreme over ...

and the right of revolution, and led to the establishment of what many consider the first modern, liberal state. Significant legislative milestones in this period included the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, which strengthened the convention that forbade detention lacking sufficient cause or evidence. The Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pr ...

formally established the supremacy of the law and of parliament over the monarch and laid down basic rights for all Englishmen. The Bill made royal interference with the law and with elections to parliament illegal, made the agreement of parliament necessary for the implementation of any new taxes and outlawed the maintenance of a standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or ...

during peacetime without parliament's consent. The right to petition the monarch was granted to everyone and "cruel and unusual punishment

Cruel and unusual punishment is a phrase in common law describing punishment that is considered unacceptable due to the suffering, pain, or humiliation it inflicts on the person subjected to the sanction. The precise definition varies by jurisd ...

s" were made illegal under all circumstances. This was followed a year later with the Act of Toleration, which drew its ideological content from John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

's four letters advocating religious toleration. The Act allowed freedom of worship to Nonconformists who pledged oaths of Allegiance and Supremacy to the Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

. In 1695, the Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons c ...

refused to renew the Licensing of the Press Act 1662

The Licensing of the Press Act 1662 was an Act of the Parliament of England (14 Car. II. c. 33) with the long title "An Act for preventing the frequent Abuses in printing seditious treasonable and unlicensed Books and Pamphlets and for regulati ...

, leading to a continuous period of unprecedented freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

.

Age of Enlightenment

The development of liberalism continued throughout the 18th century with the burgeoning Enlightenment ideals of the era. This was a period of profound intellectual vitality that questioned old traditions and influenced several European monarchies throughout the 18th century. In contrast to England, the French experience in the 18th century was characterised by the perpetuation of feudal payments and rights andabsolutism

Absolutism may refer to:

Government

* Absolute monarchy, in which a monarch rules free of laws or legally organized opposition

* Absolutism (European history), period c. 1610 – c. 1789 in Europe

** Enlightened absolutism, influenced by the En ...

. Ideas that challenged the status quo were often harshly repressed. Most of the philosophes

The ''philosophes'' () were the intellectuals of the 18th-century Enlightenment.Kishlansky, Mark, ''et al.'' ''A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, volume II: Since 1555.'' (5th ed. 2007). Few were primarily philosophe ...

of the French Enlightenment

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

were progressive in the liberal sense and advocated the reform of the French system of government along more constitutional and liberal lines. The American Enlightenment

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual ferment in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution, and the creation of the United States of America. The American Enlightenment was ...

is a period of intellectual ferment in the thirteen American colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

in the period 1714–1818, which led to the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

and the creation of the American Republic. Influenced by the 18th-century European Enlightenment and its own native American Philosophy

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the United States. The '' Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' notes that while it lacks a "core of defining features, American Philosophy can never ...

, the American Enlightenment applied scientific reasoning to politics, science and religion, promoted religious tolerance, and restored literature, the arts, and music as important disciplines and professions worthy of study in colleges.

A prominent example of a monarch who took the Enlightenment project seriously was

A prominent example of a monarch who took the Enlightenment project seriously was Joseph II of Austria

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 un ...

, who ruled from 1780 to 1790 and implemented a wide array of radical reforms, such as the complete abolition of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, the imposition of equal taxation policies between the aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

and the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

ry, the institution of religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

, including equal civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

for Jews and the suppression of Catholic religious authority throughout his empire, creating a more secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

nation. Besides the Enlightenment, a rising tide of industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly th ...

in Western Europe during the 18th century also contributed to the growth of liberal society by spurring commercial and entrepreneurial activity.

In the early 18th century, the Commonwealth men

The Commonwealth men, Commonwealth's men, or Commonwealth Party were highly outspoken British Protestant religious, political, and economic reformers during the early 18th century. They were active in the movement called the Country Party. They ...

and the Country Party in England, promoted republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

and condemned the perceived widespread corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

and lack of morality during the Walpole era, theorizing that only civic virtue

Civic virtue is the harvesting of habits important for the success of a society. Closely linked to the concept of citizenship, civic virtue is often conceived as the dedication of citizens to the common welfare of each other even at the cost of ...

could protect a country from despotism and ruin. A series of essays, known as Cato's Letters

''Cato's Letters'' were essays by British writers John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, first published from 1720 to 1723 under the pseudonym of Cato (95–46 BC), the implacable foe of Julius Caesar and a famously stalwart champion of Roman trad ...

, published in the ''London Journal

James Boswell's ''London Journal'' is a published version of the daily journal he kept between the years 1762 and 1763 while in London. Along with many more of his private papers, it was found in the 1920s at Malahide Castle in Ireland, and was ...

'' during the 1720s and written by John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, condemned tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

and advanced principles of freedom of conscience

Freedom of thought (also called freedom of conscience) is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency ...

and freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

. They were an important influence on the development of Republicanism in the United States

The values, ideals and concept of republicanism have been discussed and celebrated throughout the history of the United States. As the United States has no formal hereditary ruling class, ''republicanism'' in this context does not refer to a ...

.

In the 1760s, the "Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

radicals", led by the politician John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he ...

who was expelled from the House of Commons for seditious libel

Sedition and seditious libel were criminal offences under English common law, and are still criminal offences in Canada. Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection ...

, founded the Society for the Defence of the Bill of Rights and developed the belief that every man had the right to vote and "natural reason" enabled him to properly judge political issues. Liberty consisted in frequent elections. This was to begin a long tradition of British radicalism.

French Enlightenment

In contrast to England, the French experience in the 18th century was characterized by the perpetuation of

In contrast to England, the French experience in the 18th century was characterized by the perpetuation of feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

and absolutism

Absolutism may refer to:

Government

* Absolute monarchy, in which a monarch rules free of laws or legally organized opposition

* Absolutism (European history), period c. 1610 – c. 1789 in Europe

** Enlightened absolutism, influenced by the En ...

. Ideas that challenged the status quo were often harshly repressed. Most of the philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

s of the French Enlightenment

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

were progressive in the liberal sense and advocated the reform of the French system of government along more constitutional and liberal lines.

Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

wrote a series of highly influential works in the early 18th century, including ''Persian letters

''Persian Letters'' (french: Lettres persanes) is a literary work, published in 1721, by Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu, recounting the experiences of two fictional Persian noblemen, Usbek and Rica, who spend several years in France ...

'' (1717) and '' The Spirit of the Laws'' (1748). The latter exerted tremendous influence, both inside and outside France. Montesquieu pleaded in favor of a constitutional system of government, the preservation of civil liberties and the law and the idea that political institutions ought to reflect the social and geographical aspects of each community. In particular, he argued that political liberty required the separation of the powers of government. Building on John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

's ''Second Treatise of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (or ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, ...

'', he advocated that the executive, legislative and judicial functions of government should be assigned to different bodies, so that attempts by one branch of government to infringe on political liberty might be restrained by the other branches. In a lengthy discussion of the English political system, which he greatly admired, he tried to show how this might be achieved and liberty secured, even in a monarchy. He also notes that liberty cannot be secure where there is no separation of powers, even in a republic. He also emphasized the importance of a robust due process in law, including the right to a fair trial

A fair trial is a trial which is "conducted fairly, justly, and with procedural regularity by an impartial judge". Various rights associated with a fair trial are explicitly proclaimed in Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, th ...

, the presumption of innocence

The presumption of innocence is a legal principle that every person accused of any crime is considered innocent until proven guilty. Under the presumption of innocence, the legal burden of proof is thus on the prosecution, which must presen ...

and proportionality in the severity of punishment.

Another important figure of the French Enlightenment was Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

. Initially believing in the constructive role an enlightened monarch could play in improving the welfare of the people, he eventually came to a new conclusion: "It is up to us to cultivate our garden". His most polemical and ferocious attacks on intolerance and religious persecutions indeed began to appear a few years later. Despite much persecution, Voltaire remained a courageous polemicist who indefatigably fought for civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

—the right to a fair trial

A fair trial is a trial which is "conducted fairly, justly, and with procedural regularity by an impartial judge". Various rights associated with a fair trial are explicitly proclaimed in Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, th ...

and freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedo ...

—and who denounced the hypocrisies and injustices of the ''Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

''.

Era of revolution

American revolution

Political tension between England and its

Political tension between England and its American colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

grew after 1765 and the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

over the issue of taxation without representation, culminating in the 1776 Declaration of Independence of a new republic, and the successful American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

to defend the United States.

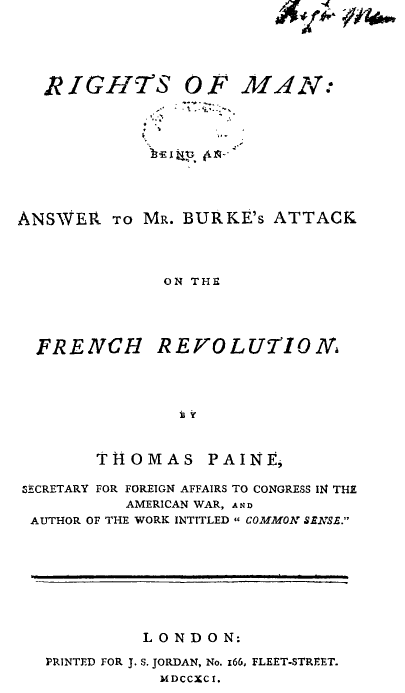

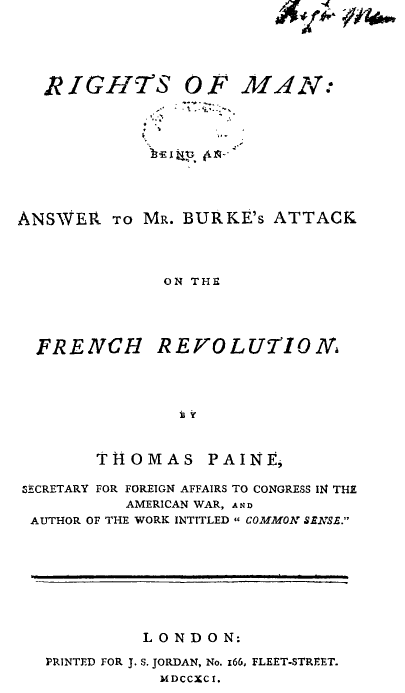

The intellectual underpinnings for independence were provided by the pamphleteer Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

. His ''Common Sense

''Common Sense'' is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political arg ...

'' pro-independence pamphlet was anonymously published on January 10, 1776 and became an immediate success. It was read aloud everywhere, including the Army. He pioneered a style of political writing that rendered complex ideas easily intelligible.

The Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

, written in committee largely by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, echoed Locke. After the war, the leaders debated about how to move forward. The Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

, written in 1776, now appeared inadequate to provide security, or even a functional government. The Confederation Congress called a Constitutional Convention in 1787, which resulted in the writing of a new Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nati ...

establishing a federal government. In the context of the times, the Constitution was a republican and liberal document.Roberts, p. 701. It remains the oldest liberal governing document in effect worldwide.

The American theorists and politicians strongly believe in the sovereignty of the people rather than in the sovereignty of the King. As one historian writes: "The American adoption of a democratic theory that all governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, as it had been put as early as the Declaration of Independence, was epoch-marking".

The American Revolution had its impact on the French Revolution and later movements in Europe. Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (; 21 December 1795 – 23 May 1886) was a German historian and a founder of modern source-based history. He was able to implement the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and the analysis ...

, a leading German historian, in 1848 argued that American republicanism played a crucial role in the development of European liberalism:

:By abandoning English constitutionalism and creating a new republic based on the rights of the individual, the North Americans introduced a new force in the world. Ideas spread most rapidly when they have found adequate concrete expression. Thus republicanism entered our Romanic/Germanic world.... Up to this point, the conviction had prevailed in Europe that monarchy best served the interests of the nation. Now the idea spread that the nation should govern itself. But only after a state had actually been formed on the basis of the theory of representation did the full significance of this idea become clear. All later revolutionary movements have this same goal.... This was the complete reversal of a principle. Until then, a king who ruled by the grace of God had been the center around which everything turned. Now the idea emerged that power should come from below.... These two principles are like two opposite poles, and it is the conflict between them that determines the course of the modern world. In Europe the conflict between them had not yet taken on concrete form; with the French Revolution it did.

French Revolution

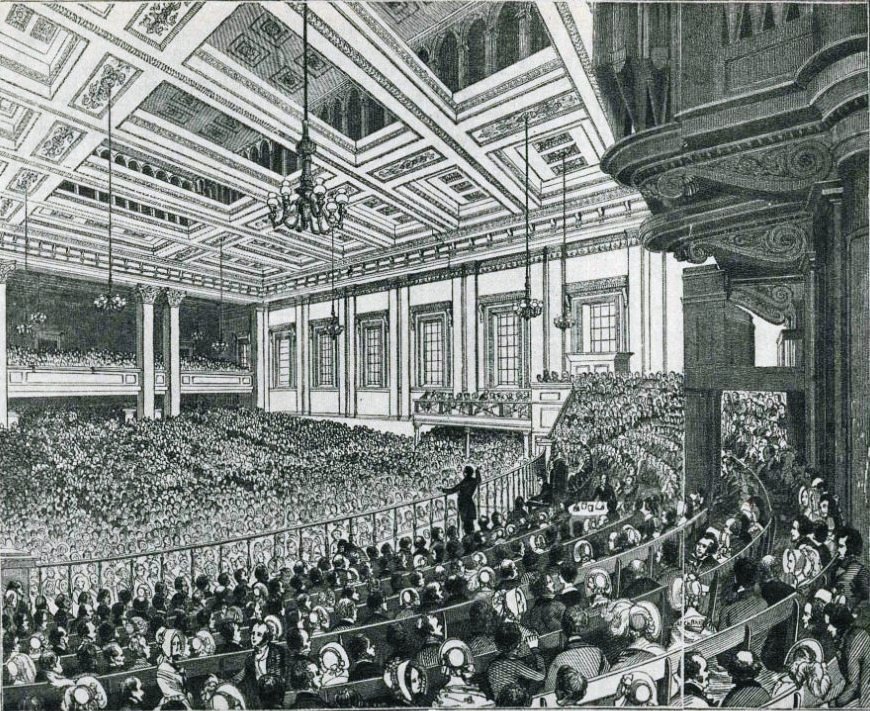

Historians widely regard the French Revolution as one of the most important events in history.Frey, Foreword. The Revolution is often seen as marking the "dawn of the modern era",Frey, Preface. and its convulsions are widely associated with "the triumph of liberalism".Ros, p. 11.

Four years into the French Revolution, German writer

Historians widely regard the French Revolution as one of the most important events in history.Frey, Foreword. The Revolution is often seen as marking the "dawn of the modern era",Frey, Preface. and its convulsions are widely associated with "the triumph of liberalism".Ros, p. 11.

Four years into the French Revolution, German writer Johann von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as treat ...

reportedly told the defeated Prussian soldiers after the Battle of Valmy

The Battle of Valmy, also known as the Cannonade of Valmy, was the first major victory by the army of France during the Revolutionary Wars that followed the French Revolution. The battle took place on 20 September 1792 as Prussian troops co ...

that "from this place and from this time forth commences a new era in world history, and you can all say that you were present at its birth". Describing the participatory politics of the French Revolution, one historian commented that "thousands of men and even many women gained firsthand experience in the political arena: they talked, read, and listened in new ways; they voted; they joined new organizations; and they marched for their political goals. Revolution became a tradition, and republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

an enduring option". For liberals, the Revolution was their defining moment, and later liberals approved of the French Revolution almost entirely—"not only its results but the act itself," as two historians noted.

The French Revolution began in 1789 with the convocation of the Estates-General in May. The first year of the Revolution witnessed members of the Third Estate proclaiming the Tennis Court Oath in June, the Storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille (french: Prise de la Bastille ) occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, when revolutionary insurgents stormed and seized control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison known as the Bastille. At ...

in July. The two key events that marked the triumph of liberalism were the Abolition of feudalism in France

One of the central events of the French Revolution was to abolish feudalism, and the old rules, taxes and privileges left over from the age of feudalism. The National Constituent Assembly, acting on the night of 4 August 1789, announced, "The Na ...

on the night of 4 August 1789, which marked the collapse of feudal and old traditional rights and privileges and restrictions, and the passage of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

in August. Jefferson, the American minister to France, was consulted in its drafting and there are striking similarities with the American ''Declaration of Independence.''

The next few years were dominated by tensions between various liberal assemblies and a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

monarchy intent on thwarting major reforms. A republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

was proclaimed in September 1792 and King Louis XVI was executed the following year. However, conflict between rival political factions, the Girondins

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnard ...

and the Jacobins

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

, culminated in the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

, that was marked by mass executions of "enemies of the revolution", with the death toll reaching into the tens of thousands. Finally Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

came to power in 1799, ended any form of democracy with his dictatorship, ended internal civil wars, made peace with the Catholic Church, and conquered much of Europe until he went too far and was finally defeated in 1815. The rise of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

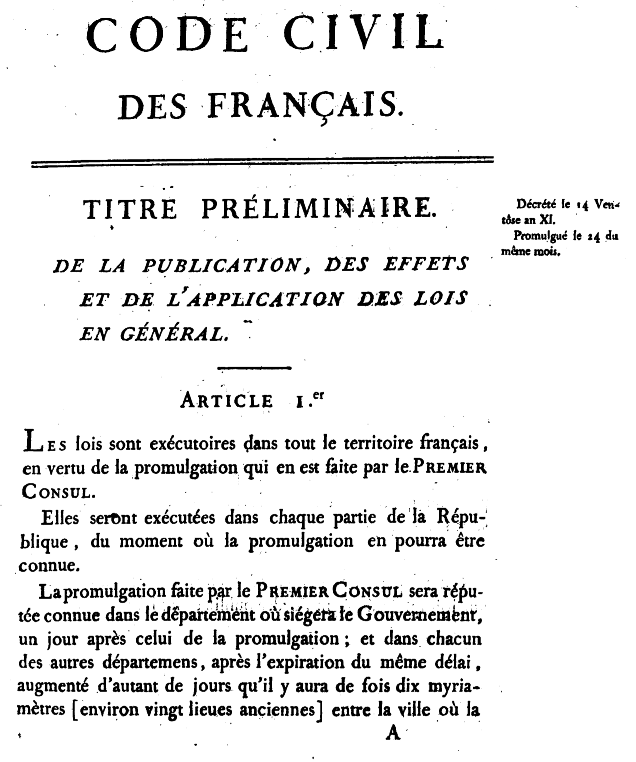

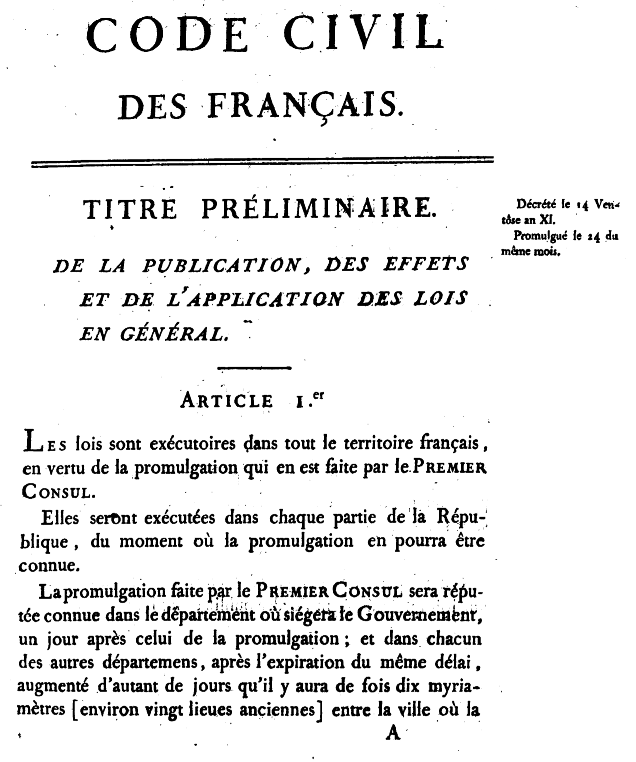

as dictator in 1799, heralded a reverse of many of the republican and democratic gains. However Napoleon did not restore the Ancien Régime, rather, he maintained much of the liberal reforms and imposed a liberal legal code, the Code Napoleon.

During the

During the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

, the French brought to Western Europe the liquidation of the feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

, the liberalization of property law

Property law is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property (land) and personal property. Property refers to legally protected claims to resources, such as land and personal property, including intellectual pro ...

s, the end of seigneurial dues, the abolition of guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

s, the legalization of divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving th ...

, the disintegration of Jewish ghettos, the collapse of the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

, the final end of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, the elimination of church courts and religious authority, the establishment of the metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that succeeded the decimalised system based on the metre that had been introduced in France in the 1790s. The historical development of these systems culminated in the definition of the Intern ...

, and equality under the law

Equality before the law, also known as equality under the law, equality in the eyes of the law, legal equality, or legal egalitarianism, is the principle that all people must be equally protected by the law. The principle requires a systematic ru ...

for all men. Napoleon wrote that "the peoples of Germany, as of France, Italy and Spain, want equality and liberal ideas,"Colton and Palmer, p. 428. with some historians suggesting that he may have been the first person ever to use the word "liberal" in a political sense. He also governed through a method that one historian described as "civilian dictatorship", which "drew its legitimacy from direct consultation with the people, in the form of a plebiscite". Napoleon, however, did not always live up to the liberal ideals he espoused.

Outside France the Revolution had a major impact and its ideas became widespread. Furthermore, the French armies in the 1790s and 1800s directly overthrew feudal remains in much of western Europe. They liberalised property law

Property law is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property (land) and personal property. Property refers to legally protected claims to resources, such as land and personal property, including intellectual pro ...

s, ended seigneurial dues, abolished the guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

of merchants and craftsmen to facilitate entrepreneurship, legalised divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving th ...

, and closed the Jewish ghettos. The Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

ended as did the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

. The power of church courts and religious authority was sharply reduced, and equality under the law

Equality before the law, also known as equality under the law, equality in the eyes of the law, legal equality, or legal egalitarianism, is the principle that all people must be equally protected by the law. The principle requires a systematic ru ...

was proclaimed for all men.

Artz emphasises the benefits the Italians gained from the French Revolution:

:For nearly two decades the Italians had the excellent codes of law, a fair system of taxation, a better economic situation, and more religious and intellectual toleration than they had known for centuries ... Everywhere old physical, economic, and intellectual barriers had been thrown down and the Italians had begun to be aware of a common nationality.

Likewise in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

the long-term impact of the French Revolution has been assessed by Martin:

:It proclaimed the equality of citizens before the law, equality of languages, freedom of thought and faith; it created a Swiss citizenship, basis of our modern nationality, and the separation of powers, of which the old regime had no conception; it suppressed internal tariffs and other economic restraints; it unified weights and measures, reformed civil and penal law, authorised mixed marriages (between Catholics and Protestants), suppressed torture and improved justice; it developed education and public works.

His most lasting achievement, the Civil Code

A civil code is a codification of private law relating to property, family, and obligations.

A jurisdiction that has a civil code generally also has a code of civil procedure. In some jurisdictions with a civil code, a number of the core ar ...

, served as "an object of emulation all over the globe," but it also perpetuated further discrimination against women under the banner of the "natural order". This unprecedented period of chaos and revolution had irreversibly introduced the world to a new movement and ideology that would soon criss-cross the globe. For France, however, the defeat of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

brought about the restoration of the monarchy