This article addresses the history of lesbianism in the United States. Unless otherwise noted, the members of same-sex female couples discussed here are not known to be lesbian (rather than, for example, bisexual), but they are mentioned as part of discussing the practice of lesbianism—that is, same-sex female sexual and romantic behavior.

1600–1899

Laws against

lesbian sexual activity were suggested but usually not created or enforced in early American history. In 1636,

John Cotton proposed a law for Massachusetts Bay making sex between two women (or two men) a capital offense, but the law was not enacted.

It would have read, "Unnatural filthiness, to be punished with death, whether sodomy, which is carnal fellowship of man with man, or woman with woman, or buggery, which is carnal fellowship of man or woman with beasts or fowls."

In 1655, the

Connecticut Colony passed a law against sodomy between women (as well as between men), but nothing came of this either.

[Foster, Thomas (2007). Long Before Stonewall: Histories of Same-Sex Sexuality in Early America. New York University Press.] In 1779,

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

proposed a law stating that, "Whosoever shall be guilty of rape, polygamy, or sodomy with man or woman shall be punished, if a man, by castration. If a woman, by cutting thro' the cartilage of her nose a hole of one half inch diameter at the least,

" but this also did not become law. However, in 1649 in

Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the passengers on the ...

,

Sarah White Norman Sarah White Norman (ca. 1623-1654) and Mary Vincent Hammon (1633-1705) were prosecuted in 1648 for "lewd behavior with each other upon a bed"; their trial documents are the only known record of sex between female English colonists in North America i ...

and

Mary Vincent Hammon were prosecuted for "lewd behavior with each other upon a bed"; their trial documents are the only known record of sex between female English colonists in North America during the 17th century.

Hammon was only admonished, perhaps because she was younger than sixteen,

but in 1650 Norman was convicted and required to acknowledge publicly her "unchaste behavior" with Hammon, as well as warned against future offenses. This may be the only conviction for lesbianism in American history.

In the 19th century, lesbians were only accepted if they hid their

sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generall ...

and were presumed to be merely friends with their partners. For example, the term "

Boston marriage

A "Boston marriage" was, historically, the cohabitation of two wealthy women, independent of financial support from a man. The term is said to have been in use in New England in the late 19th/early 20th century. Some of these relationships were ...

" was used to describe a committed relationship between two unmarried women who were usually financially independent and often shared a house;

these relationships were presumed to be asexual, and hence the women were respected as "spinsters" by their communities.

Notable women in Boston marriages included

Sarah Jewett and

Annie Adams Fields

Annie Adams Fields (June 6, 1834 – January 5, 1915) was an American writer. Among her writings are collections of poetry and essays as well as several memoirs and biographies of her literary acquaintances. She was also interested in philanthro ...

,

as well as

Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

and Mary Rozet Smith.

Some American lesbians in the arts moved in the 19th century from the United States to Rome, including the actress

Charlotte Cushman

Charlotte Saunders Cushman (July 23, 1816 – February 18, 1876) was an American stage actress. Her voice was noted for its full contralto register, and she was able to play both male and female parts. She lived intermittently in Rome, in an expa ...

, and sculptors

Emma Stubbins and

Harriet Hosmer. Around 1890, former acting First Lady

Rose Cleveland started a lesbian relationship with

Evangeline Marrs Simpson, with explicitly erotic correspondence; this cooled when Evangeline married

Henry Benjamin Whipple

Henry Benjamin Whipple (February 15, 1822 – September 16, 1901) was the first Episcopal bishop of Minnesota, who gained a reputation as a humanitarian and an advocate for Native Americans.

Summary of his life

Born in Adams, New York, he was ...

, but after his death in 1901 the two rekindled their relationship and in 1910 moved to Italy together.

Lillian Faderman

Lillian Faderman (born July 18, 1940) is an American historian whose books on lesbian history and LGBT history have earned critical praise and awards. ''The New York Times'' named three of her books on its "Notable Books of the Year" list. In add ...

, ''Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America'', Penguin Books Ltd, 1991, page 32

1900–1949

Studies on lesbian activity in prisons

The earliest published studies of lesbian activity were written in the early 20th century, and many were based on observations of, and data gathered from,

incarcerated women. Margaret Otis published "A Perversion Not Commonly Noted" in the 1913 ''Journal of Psychology'', coupling a decidedly

Puritanical moral foundation with an almost revolutionary sympathy for lesbian relationships; her focus revolved more around her revulsion for sexual contact between those of different ethnic backgrounds, yet offered an almost radical tolerance of the lesbian relations themselves, as Otis noted, "Sometimes the love (of one young woman for another) is very real and seems almost ennobling".

This document provided a rare view from a tightly controlled setting monitored by a

corrections

In criminal justice, particularly in North America, correction, corrections, and correctional, are umbrella terms describing a variety of functions typically carried out by government agencies, and involving the punishment, treatment, and s ...

supervisor.

Kate Richards O'Hare

Carrie Katherine "Kate" Richards O'Hare (March 26, 1876 – January 10, 1948) was an American Socialist Party activist, editor, and orator best known for her controversial imprisonment during World War I.

Biography

Early years

Carrie Katherin ...

, imprisoned in 1917 for five years under the

Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (War ...

, published a firsthand account of incarcerated women ''In Prison''

complete with frightening accounts of lesbian

sexual abuse

Sexual abuse or sex abuse, also referred to as molestation, is abusive sexual behavior by one person upon another. It is often perpetrated using force or by taking advantage of another. Molestation often refers to an instance of sexual assa ...

among inmates. So wrote O'Hare: "...A thorough education in sex perversions is part of the educational system of most prisons, and for the most part the underkeepers

icand the stool pigeons are very efficient teachers..." O'Hare then recounted a systematic induction of women into a cycle of

forced prostitution

Forced prostitution, also known as involuntary prostitution or compulsory prostitution, is prostitution or sexual slavery that takes place as a result of coercion by a third party. The terms "forced prostitution" or "enforced prostitution" appea ...

to which authorities turned a blind eye: "...there seems to be considerable ground for the commonly accepted belief of the prison inmates that much of its graft and profits may percolate upward to the under officials...the...stool pigeon...handled the vices so rampant in the prison...she, in fact, held the power of life and death over us, by being able to secure endless punishments in the blind, she could and did compel indulgence in this vice in order that its profits might be secured".

Lesbian community

Early academic study of lesbian community include lesbian

Mildred Berryman's 1930's groundbreaking

''The Psychological Phenomena of the Homosexual''

on 23 lesbian women, whom she met through the Salt Lake City Bohemian Club.

In the study most of the subjects (many of whom had Mormon background)

reported experiencing erotic interest in others of the same sex since childhood,

and exhibited self-identity and community identity as sexual minorities.

During the 1920s lesbian subcultures were beginning to become more established in several larger US cities. However, police raids happened on lesbian places, resulting in their closure, such as the

Eve's Hangout

Eve's Hangout was a New York City lesbian nightclub established by Polish feminist Eva Kotchever in Greenwich Village, Lower Manhattan, in 1925. The establishment was also known as "Eve Adams' Tearoom", a pun on the names Eve and Adam.

History

...

in Greenwich Village, after the deportation of

Eva Kotchever for

obscenity.

Lesbians in literature

Lesbians also became somewhat more prominent in literature at this time. In the early 20th century, Paris became a haven for many lesbian writers who set up salons there and were able to live their lives in relative openness. The most famous Americans of these were

Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris ...

and

Alice B. Toklas, who lived together there as a couple for many years. In 1922, Gertrude Stein published "Miss Furr and Miss Skeene", a story based on the American couple

Maud Hunt Squire

Maud Hunt Squire (January 30, 1873 – October 25, 1954) was an American painter and printmaker. She had a lifelong relationship with artist Ethel Mars, with whom she traveled and lived in the United States and France.

Early life and education

...

and

Ethel Mars, artists who visited Stein and Toklas in Paris at Stein's salon.

In 1933, Stein published The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, a modernist memoir of her Paris years written in the voice of Toklas, which became a literary bestseller.

Another significant early 20th century writer about lesbian themes was

Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes (, June 12, 1892 – June 18, 1982) was an American artist, illustrator, journalist, and writer who is perhaps best known for her novel ''Nightwood'' (1936), a cult classic of lesbian fiction and an important work of modernist liter ...

, who wrote the book

Nightwood

''Nightwood'' is a 1936 novel by American author Djuna Barnes that was first published by publishing house Faber and Faber. It is one of the early prominent novels to portray explicit homosexuality between women, and as such can be considered ...

. Both Barnes and Gertrude Stein were visitors to another influential Parisian salon hosted by American expatriate

Nathalie Barney

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American writer who hosted a salon (gathering), literary salon at her home in Paris that brought together French and international writers. She influenced other authors throu ...

, as was sculptor

Thelma Wood, photographer

Berenice Abbott and painter

Romaine Brooks

Romaine Brooks (born Beatrice Romaine Goddard; May 1, 1874 – December 7, 1970) was an American painter who worked mostly in Paris and Capri. She specialized in portrait painting, portraiture and used a subdued tonal Palette (painting), palette ...

. In 1923, lesbian

Elsa Gidlow

Elsa Gidlow (29 December 1898 – 8 June 1986) was a British-born, Canadian-American poet, freelance journalist, philosopher and humanitarian. She is best known for writing ''On a Grey Thread'' (1923), the first volume of openly lesbian love ...

, born in England, published the first volume of openly

lesbian love poetry in the United States, ''On A Grey Thread''.

Yet, openly lesbian literature was still subject to censorship. In 1928, British lesbian author

Radclyffe Hall

Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943) was an English poet and author, best known for the novel ''The Well of Loneliness'', a groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. In adulthood, Hall often went by the name Jo ...

wrote a tragic novel of lesbian love, ''

The Well of Loneliness

''The Well of Loneliness'' is a lesbian novel by British author Radclyffe Hall that was first published in 1928 by Jonathan Cape. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose " sexual inversion" (hom ...

''. After the book was banned in England, Hall lost her first American publisher.

In New York, John Saxton Sumner of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and several police detectives seized 865 copies of ''The Well'' from her second American publisher's offices, and Donald Friede was charged with selling an obscene publication. But Friede and his publishing partner Pascal Covici had already moved the printing plates out of New York in order to continue publishing the book. By the time the case came to trial, it had already been reprinted six times. Despite its price of $5 — twice the cost of an average novel — it would sell over 100,000 copies in its first year.

[Taylor, "I Made Up My Mind", ''passim''.]

In the United States, as in the United Kingdom, the Hicklin test of obscenity applied, but New York

case law had established that books should be judged by their effects on adults rather than on children and that literary merit was relevant.

Morris Ernst, co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, obtained statements from authors, including Dreiser,

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century f ...

,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

,

Edna St. Vincent Millay,

Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

,

Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

,

H. L. Mencken

Henry Louis Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956) was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, ...

,

Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

,

Ellen Glasgow

Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow (April 22, 1873 – November 21, 1945) was an American novelist who won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1942 for her novel ''In This Our Life''. She published 20 novels, as well as short stories, to critical ac ...

, and

John Dos Passos

John Roderigo Dos Passos (; January 14, 1896 – September 28, 1970) was an American novelist, most notable for his ''U.S.A.'' trilogy.

Born in Chicago, Dos Passos graduated from Harvard College in 1916. He traveled widely as a young man, visit ...

.

[Cline, 271.] To make sure these supporters did not go unheard, he incorporated their opinions into his

brief

Brief, briefs, or briefing may refer to:

Documents

* A letter

* A briefing note

* Papal brief, a papal letter less formal than a bull, sealed with the pope's signet ring or stamped with the device borne on this ring

* Design brief, a type of ed ...

. His argument relied on a comparison with ''Mademoiselle de Maupin'' by

Théophile Gautier

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier ( , ; 30 August 1811 – 23 October 1872) was a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, and art and literary critic.

While an ardent defender of Romanticism, Gautier's work is difficult to classify and rema ...

, which had been cleared of obscenity in the 1922 case ''Halsey v. New York''. ''Mademoiselle de Maupin'' described a lesbian relationship in more explicit terms than ''The Well'' did. According to Ernst, ''The Well'' had greater social value because it was more serious in tone and made a case against misunderstanding and intolerance.

In an opinion issued on February 19, 1929, Magistrate Hyman Bushel declined to take the book's literary qualities into account and said ''The Well'' was "calculated to deprave and corrupt minds open to its immoral influences". Under New York law, however, Bushel was not a

trier of fact

A trier of fact or finder of fact is a person or group who determines which facts are available in a legal proceeding (usually a trial) and how relevant they are to deciding its outcome. To determine a fact is to decide, from the evidence present ...

; he could only remand the case to the New York Court of Special Sessions for judgment. On 19 April, that court issued a three-paragraph decision stating that ''The Wells theme — a "delicate social problem" — did not violate the law unless written in such a way as to make it obscene. After "a careful reading of the entire book", they cleared it of all charges.

Covici-Friede then imported a copy of the Pegasus Press edition from France as a further test case and to solidify the book's U.S. copyright.

Customs barred the book from entering the country, which might also have prevented it from being shipped from

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

to state.

The

United States Customs Court

The United States Court of International Trade (case citations: Int'l Trade or Intl. Trade) is a U.S. federal court that adjudicates civil actions arising out of U.S. customs and international trade laws. Seated in New York City, it exercises ...

, however, ruled that the book did not contain "one word, phrase, sentence or paragraph which could be truthfully pointed out as offensive to modesty".

Most literature of the 1930s, '40s, and early '50s presented lesbian life as tragedy, ending with either the suicide of the lesbian character or her conversion to heterosexuality.

This was required so that the authorities did not declare the literature obscene.

[Gallo, p. 67] For example, ''The Stone Wall'', a lesbian autobiography with an unhappy ending, was published in 1930 under the pseudonym Mary Casal.

It was one of the first lesbian autobiographies. Yet as early as 1939,

Frances V. Rummell

Frances V. Rummell (November 14, 1907 - May 11, 1969) was an educator and columnist who is known posthumously as the author and publisher of the first explicitly lesbian autobiography in the United States.

Early life

Frances Virginia Rummell ...

, an educator and a teacher of French at Stephens College, published the first explicitly lesbian autobiography in which two women end up happily together, titled ''Diana: A Strange Autobiography''.

This autobiography was published with a note saying, "The publishers wish it expressly understood that this is a true story, the first of its kind ever offered to the general reading public"

The first American magazine written for lesbians, ''

Vice Versa: America's Gayest Magazine'', was published from 1947–1948. It was written by a lesbian secretary named

Edith Eyde

Edythe D. Eyde (November 7, 1921 – December 22, 2015) better known by her pen name Lisa Ben, was an American editor, author, active fantasy-fiction fan and fanzine contributor (often using the name Tigrina in these activities), and songwrite ...

, writing under the pen name Lisa Ben, an anagram for lesbian.

She produced only nine issues of ''Vice Versa'', typing two originals of each with carbons.

She learned that she could not mail them due to possible obscenity charges, and even had difficulty distributing them by hand in lesbian bars such as the If Club.

Furthermore, the

Hays Code

The Motion Picture Production Code was a set of industry guidelines for the self-censorship of content that was applied to most motion pictures released by major studios in the United States from 1934 to 1968. It is also popularly known as the ...

, which was in operation from 1930 until 1967, prohibited the depiction of homosexuality in all Hollywood films.

Lesbians in the military

Many lesbians found solace in the all-female environment of the United States

Women's Army Corps

The Women's Army Corps (WAC) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) on 15 May 1942 and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the United States ...

(WAC), but this demanded secrecy, as lesbians were not allowed to serve openly in the U.S. military.

[Frances Ann Da]

Lesbian and gay voices: an annotated bibliography and guide to literature for children and young adults

Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000 p. 116[Craig A. Rimmerma]

Gay rights, military wrongs: political perspectives on lesbians and gays in the military

Garland Pub., 1996 p. 76 Over the years the military not only dismissed women who announced their lesbianism, but sometimes went on "witch hunts" for lesbians in the ranks.

1950–1999

1950s: Lesbianism in literature

It was not until the mid-1950s that obscenity regulations began to relax and happy endings to lesbian romances became possible.

However, publications addressing homosexuality were officially deemed obscene under the

Comstock Act

The Comstock laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.Dennett p.9 The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression of ...

until 1958.

[Murdoch and Price, p. 47]

''

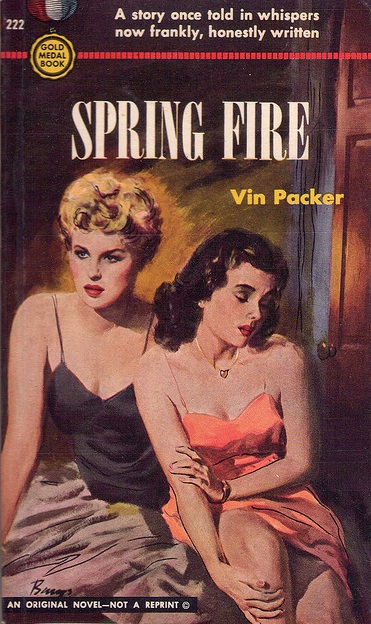

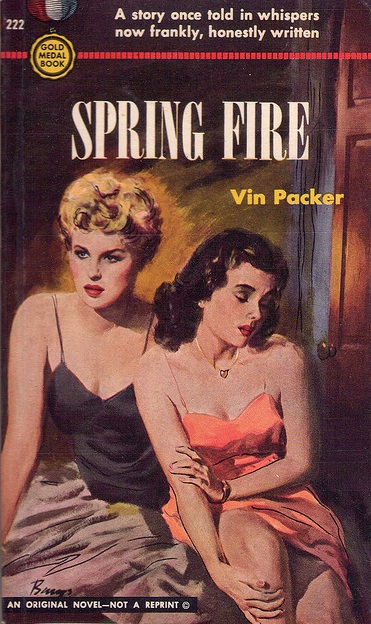

Spring Fire

''Spring Fire'', is a 1952 paperback novel written by Marijane Meaker, under the pseudonym "Vin Packer". It is the first lesbian paperback novel, and the beginning of the lesbian pulp fiction genre; it also addresses issues of conformity in 195 ...

'', the first lesbian paperback novel, and considered the beginning of the

lesbian pulp fiction

Lesbian pulp fiction is a genre of lesbian literature that refers to any mid-20th century paperback novel or pulp magazine with overtly lesbian themes and content. Lesbian pulp fiction was published in the 1950s and 60s by many of the same pa ...

genre, was published in 1952 and sold 1.5 million copies.

[Spring Fire (Lesbian Pulp Fiction) (9781573441872): Vin Packer: Books](_blank)

Amazon.com. Retrieved on 2010-11-30. It was written by lesbian author

Marijane Meaker

Marijane Agnes Meaker (May 27, 1927 – November 21, 2022) was an American writer who, along with Tereska Torres, was credited with launching the lesbian pulp fiction genre, the only accessible novels on that theme in the 1950s.

Under the name ...

under the

pen name "Vin Packer",

and ended unhappily.

1952 also saw the publication of lesbian classic ''

The Price of Salt'' by lesbian author

Patricia Highsmith

Patricia Highsmith (January 19, 1921 – February 4, 1995) was an American novelist and short story writer widely known for her psychological thrillers, including her series of five novels featuring the character Tom Ripley.

She wrote 22 novel ...

, published under the pseudonym "Claire Morgan", in which the women break up but are implied to get back together in the end (the novel was republished as ''Carol'' in 1990 under Highsmith's name).

In her 2003 memoir, Marijane Meaker said that, for many years, ''The Price of Salt'' was "the only lesbian novel, in either hard or soft cover, with a happy ending".

1950s: The Kinsey Report

In 1953,

Alfred Kinsey

Alfred Charles Kinsey (; June 23, 1894 – August 25, 1956) was an American sexologist, biologist, and professor of entomology and zoology who, in 1947, founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, now known as the Kinsey Insti ...

published "Sexual Behavior in the Human Female," in which he noted that 13% of the women he studied had at least one homosexual experience to orgasm (vs. 37% for men), while including homosexual experience that did not lead to orgasm raised the figure for women to 20%.

In addition, Kinsey noted that somewhere between 1% and 2% of the women he studied were exclusively homosexual (vs. 4% of the men).

1950s: Legal restrictions on gays and lesbians

On April 27, 1953, President Eisenhower issued

Executive Order 10450, which banned gay men and lesbians from working for any agency of the federal government. It was not until 1973 that a federal judge ruled that a person's sexual orientation alone could not be the sole reason for termination from federal employment,

and not until 1975 that the

United States Civil Service Commission

The United States Civil Service Commission was a government agency of the federal government of the United States and was created to select employees of federal government on merit rather than relationships. In 1979, it was dissolved as part of t ...

announced that they would consider applications by gays and lesbians on a case by case basis.

1950s–70s Rise of the

LGBT

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term ...

rights movement

In the 1950s the lesbian rights movement began in America. The

Daughters of Bilitis

The Daughters of Bilitis , also called the DOB or the Daughters, was the first lesbian civil and political rights organization in the United States. The organization, formed in San Francisco in 1955, was conceived as a social alternative to le ...

(DOB) was founded in San Francisco in 1955 by four female couples (including

Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon) and was the first national lesbian political and social organization in the United States.

The group's name came from "

The Songs of Bilitis

''The Songs of Bilitis'' (; french: Les Chansons de Bilitis) is a collection of erotic, essentially lesbian, poetry by Pierre Louÿs published in Paris in 1894. Since Louÿs claimed that he had translated the original poetry from Ancient Greek, ...

," a lesbian-themed song cycle by French poet

Pierre Louÿs

Pierre Louÿs (; 10 December 1870 – 4 June 1925) was a French poet and writer, most renowned for lesbian and classical themes in some of his writings. He is known as a writer who sought to "express pagan sensuality with stylistic perfection". ...

, which described the fictional Bilitis as a resident of the Isle of

Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Asia Minor by the nar ...

alongside

Sappho.

DOB's activities included hosting public forums on homosexuality, offering support to isolated, married, and mothering lesbians, and participating in research activities.

Del Martin became DOB's first president, and Phyllis Lyon became the editor of the organization's monthly lesbian magazine, ''

The Ladder'', which was launched in October 1956 and continued until 1972, having reached print runs of almost 3,800 copies.

The show ''Confidential File'' on the station

KTTV

KTTV (channel 11) is a television station in Los Angeles, California, United States, serving as the West Coast flagship of the Fox network. It is owned and operated by the network's Fox Television Stations division alongside MyNetworkTV ou ...

covered the 1962 convention of DOB and aired after ''Confidential File'' became syndicated nationally; this was probably the first American national broadcast that specifically covered lesbianism.

Kay Lahusen

Katherine Lahusen (also known as Kay Tobin; January 5, 1930 – May 26, 2021) was an American photographer, writer and gay rights activist. She was the first openly lesbian American photojournalist.Riordan, Kevin (Fall 2001). "Together they spar ...

, the first openly gay or lesbian photojournalist of the gay rights movement,

[Riordan, Kevin (Fall 2001)] photographed lesbians for several of the covers of ''The Ladder'' from 1964 to 1966 while her partner,

Barbara Gittings

Barbara Gittings (July 31, 1932 – February 18, 2007) was a prominent American activist for LGBT equality. She organized the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) from 1958 to 1963, edited the national DOB magazine ''The Ladd ...

, was the editor; previously there had been drawings of people and cats and such on the covers.

The first photograph of lesbians on the cover was done in September 1964, showing two women from the back, on a beach looking out to sea.

The first lesbian to appear on the cover with her face showing was

Lilli Vincenz

Lilli Vincenz is a lesbian activist and the first lesbian member of the gay political activist effort, the Mattachine Society of Washington (MSW).

She served as the editor of the organization's newsletter and in 1969 along with Nancy Tucker created ...

in January 1966.

Daughters of Bilitis ended in 1970.

The

Cooper Do-nuts Riot

The Cooper Do-nuts Riot was a small uprising in response to police harassment of LGBT people at the 24-hour Cooper Do-nuts cafe in Los Angeles in May 1959. This occurred 10 years prior to the better-known Stonewall riots in New York City and is ...

was a May 1959 incident in Los Angeles, in which lesbians, transgender women, drag queens, and gay men rioted, one of the first

LGBT

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term ...

uprisings in the US.

The incident was sparked by police harassment of LGBT people at a 24-hour cafe called "Cooper Do-nuts".

The first public protests for equal rights for gay and lesbian people were staged at governmental offices and historic landmarks in New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. between 1965 and 1969.

[LGBT Civil Rights, UW Madison](_blank)

. Housing.wisc.edu (1969-06-28). Retrieved on 2010-11-30. In DC, protesters picketed in front of the White House, Pentagon, and the U.S. Civil Service Commission.

Lilli Vincenz

Lilli Vincenz is a lesbian activist and the first lesbian member of the gay political activist effort, the Mattachine Society of Washington (MSW).

She served as the editor of the organization's newsletter and in 1969 along with Nancy Tucker created ...

was the only self-identified lesbian to participate in the second White House picket.

The other two women at that picket were heterosexually married, though one, J.D., identified herself as a bisexual.

Lesbian activist

Barbara Gittings

Barbara Gittings (July 31, 1932 – February 18, 2007) was a prominent American activist for LGBT equality. She organized the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) from 1958 to 1963, edited the national DOB magazine ''The Ladd ...

was also among the picketers of the White House at some protests, and often among the annual picketers outside Independence Hall.

In 1965, Gittings marched in the first gay

picket line

A picket line is a horizontal rope along which horses are tied at intervals. The rope can be on the ground, at chest height (above the knees, below the neck) or overhead. The overhead form is usually called a high line.

A variant of a high l ...

s at the White House, the US

State Department, and at

Independence Hall

Independence Hall is a historic civic building in Philadelphia, where both the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted by America's Founding Fathers. The structure forms the centerpi ...

to protest the federal government's policy on discrimination against gay people, holding a sign that read "Sexual preference is irrelevant to federal employment."

[ Glbt History Month; October 14, 2006; retrieved November 4, 2007.][ (Press Release). New York Public Library; retrieved November 4, 2007.] Gittings and

Frank Kameny led the

Annual Reminder The Annual Reminders were a series of early pickets organized by gay organizations, held yearly from 1965 through 1969. The Reminder took place each July 4 at Independence Hall in Philadelphia and were among the earliest LGBT demonstrations in the ...

, the first pickets organized by homophile organizations specifically to demand equality for gays and lesbians, which included activists from New York, Washington D.C., and Philadelphia and took place each Fourth of July from 1965 to 1969 in front of Independence Hall.

Political lesbianism

Political lesbianism is a phenomenon within feminism, primarily second-wave feminism and radical feminism; it includes, but is not limited to, lesbian separatism. Political lesbianism asserts that sexual orientation is a political and feminist ...

, which embraces the theory that sexual orientation is a political and feminist choice, and advocates lesbianism as a positive alternative to heterosexuality for women as part of the struggle against sexism, originated in the late 1960s among

second wave radical feminists

Radical feminism is a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical re-ordering of society in which male supremacy is eliminated in all social and economic contexts, while recognizing that women's experiences are also affected by other ...

.

Ti-Grace Atkinson

Grace Atkinson (born November 9, 1938), better known as Ti-Grace Atkinson, is an American radical feminist activist, writer and philosopher.

Life and career

Atkinson was born into a prominent Louisiana family. Named after her grandmother, Gra ...

, a lesbian and radical feminist who helped to found the group

The Feminists, is attributed with the phrase that embodies the movement: "Feminism is the theory; lesbianism is the practice." The Feminists, also known as Feminists—A Political Organization to Annihilate Sex Roles, was a radical feminist group active in New York City from 1968 to 1973. They at first advocated that women practice celibacy, and later came to advocate political lesbianism.

The modern LGBT civil rights movement began in 1969 with the

Stonewall Riots, when police raided a gay bar called the Stonewall Inn. A scuffle broke out when a woman in handcuffs was escorted from the door of the bar to the waiting police wagon several times. She escaped repeatedly and fought with four of the police, swearing and shouting, for about ten minutes. Described as "a typical New York butch" and "a dyke–stone butch", she had been hit on the head by an officer with a

baton for, as one witness claimed, complaining that her handcuffs were too tight.

[Duberman, Martin (1993). ''Stonewall'', Penguin Books. , p. 196.] Bystanders recalled that the woman, whose identity remains unknown (

Stormé DeLarverie

Stormé DeLarverie (December 24, 1920 – May 24, 2014) was an American woman known as the butch lesbian whose scuffle with police was, according to Stormé and many eyewitnesses, the spark that ignited the Stonewall uprising, spurring the cro ...

, who was a lesbian, has been identified by some, including herself, as the woman, but accounts vary

[Accounts of people who witnessed the scene, including letters and news reports of the woman who fought with police, conflicted. Where witnesses claim one woman who fought her treatment at the hands of the police caused the crowd to become angry, some also remembered several "butch lesbians" had begun to fight back while still in the bar. At least one was already bleeding when taken out of the bar (Carter, David (2004). ''Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution'', St. Martin's Press. , pp. 152–153). Craig Rodwell (in Duberman, p. 197) claims the arrest of the woman was not the primary event that triggered the violence, but one of several simultaneous occurrences: "there was just ... a flash of group—of mass—anger."]), sparked the crowd to fight when she looked at bystanders and shouted, "Why don't you guys do something?" After an officer picked her up and heaved her into the back of the wagon,

[Carter, p. 152.] the crowd became a mob and went "berserk": "It was at that moment that the scene became explosive."

[Carter, p. 151.] Lesbian

Martha Shelley

Martha Shelley (born December 27, 1943) is an American activist, writer, and poet best known for her involvement in lesbian feminist activism.

Life and early work

Martha Altman was born on December 27, 1943, in Brooklyn, New York, to parents of ...

was also in Greenwich Village the night of the Stonewall Riot with women who were starting a Daughters of Bilitis chapter in Boston.

Recognizing the significance of the event and being politically aware

she proposed a protest march and as a result DOB and Mattachine sponsored a demonstration.

According to an article in the program for the first San Francisco pride march, she was one of the first four members of the

Gay Liberation Front

Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was the name of several gay liberation groups, the first of which was formed in New York City in 1969, immediately after the Stonewall riots. Similar organizations also formed in the UK and Canada. The GLF provided a ...

, the others being Michael Brown, Jerry Hoose, and Jim Owles.

1970s: Lesbians and feminism

Lesbians were also active in the feminist movement. The first time lesbian concerns were introduced into the

National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

came in 1969, when

Ivy Bottini

Ivy Bottini (August 15, 1926 – February 25, 2021) was an American activist for women's and LGBT rights, and a visual artist.

Personal life and career

Bottini was born in New York in August 1926. From 1944 until 1947, she attended Pratt Institu ...

, an open lesbian who was then president of the New York NOW chapter, held a public forum titled "Is Lesbianism a Feminist Issue?".

[ Love, Barbara J.br>Feminists Who Changed America, 1963-1975]

/ref> However, the national president, Betty Friedan

Betty Friedan ( February 4, 1921 – February 4, 2006) was an American feminist writer and activist. A leading figure in the women's movement in the United States, her 1963 book ''The Feminine Mystique'' is often credited with sparking the se ...

, was against lesbian participation in the movement. In 1969 she referred to growing lesbian visibility as a "lavender menace" and fired openly lesbian newsletter editor Rita Mae Brown

Rita Mae Brown (born November 28, 1944) is an American feminist writer, best known for her coming-of-age autobiographical novel, ''Rubyfruit Jungle''. Brown was active in a number of civil rights campaigns and criticized the marginalization of le ...

, and in 1970 she engineered the expulsion of lesbians, including Bottini, from the New York chapter.[Bonnie Zimmerma]

Lesbian histories and cultures: an encyclopedia

Garland Pub., 2000 p. 134[Vicki Lynn Eaklo]

Queer America: a GLBT history of the 20th century

ABC-CLIO, 2008 p. 145

At the 1970 Congress to Unite Women, on the first evening when all 400 feminists were assembled in the auditorium, twenty women wearing t-shirts that read "Lavender Menace" came to the front of the room and faced the audience.[Flora Davi]

Moving the mountain: the women's movement in America since 1960

University of Illinois Press, 1999 p. 264 One of the women then read their group's paper, "The Woman-Identified Woman

"The Woman-Identified Woman" was a ten-paragraph manifesto, written by the Radicalesbians in 1970. It was first distributed during the Lavender Menace protest at the Second Congress to Unite Women, on May 1, 1970, in New York City. It is now co ...

", which was the first major lesbian feminist statement.[Cheshire Calhou]

Feminism, the Family, and the Politics of the Closet: Lesbian and Gay Displacement

Oxford University Press, 2003 p. 27 The group, who later named themselves Radicalesbians, were among the first to challenge the heterosexism

Heterosexism is a system of attitudes, bias, and discrimination in favor of female–male sexuality and relationships. According to Elizabeth Cramer, it can include the belief that all people are or should be heterosexual and that heterosexua ...

of heterosexual feminists and to describe lesbian experience in positive terms.[Carolyn Zerbe Enn]

Feminist theories and feminist psychotherapies: origins, themes, and diversity

Routledge, 2004 p. 105 In 1971 NOW passed a resolution declaring "that a woman's right to her own person includes the right to define and express her own sexuality and to choose her own lifestyle," as well as a conference resolution stating that forcing lesbian mothers to stay in marriages or to live a secret existence in an effort to keep their children was unjust.[Leading the Fight , National Organization for Women](_blank)

NOW. Retrieved on 2014-07-25. That year NOW also committed to offering legal and moral support in a test case involving child custody rights of lesbian mothers.[Friedan, Betty. ''Life So Far'', op. cit. Page 222.] She refused to wear a purple armband or self-identify as a lesbian as an act of political solidarity, considering it not part of the mainstream issues of abortion and child care.[Friedan, Betty. ''Life So Far'', op. cit. Pp. 248–249.] She later wrote, "The women's movement was not about sex, but about equal opportunity in jobs and all the rest of it. Yes, I suppose you have to say that freedom of sexual choice is part of that, but it shouldn't be the main issue ...."[Friedan, Betty. ''Life So Far'', op. cit. Page 223.] Friedan eventually admitted that "the whole idea of homosexuality made me profoundly uneasy." At the 1977 National Women's Conference, Friedan seconded the lesbian rights resolution "which everyone thought I would oppose" in order to "preempt any debate" and move on to other issues she believed were more important and less divisive in the effort to add the Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution.

At the 1977 National Women's Conference, Friedan seconded the lesbian rights resolution "which everyone thought I would oppose" in order to "preempt any debate" and move on to other issues she believed were more important and less divisive in the effort to add the Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution.[Friedan, Betty. ''Life So Far'', op. cit. Page 295.] The lesbian rights resolution passed.National Women's Conference

The National Women's Conference of 1977 was a four-day event during November 18–21, 1977, as organized by the National Commission on the Observance of International Women's Year. The conference drew around, 2,000 delegates along with 15,000-20, ...

issued th

National Plan of Action

which stated in part, "Congress, State, and local legislatures should enact legislation to eliminate discrimination on the basis of sexual and affectional preference in areas including, but not limited to, employment, housing, public accommodations, credit, public facilities, government funding, and the military. State legislatures should reform their penal codes or repeal State laws that restrict private sexual behavior between consenting adults. State legislatures should enact legislation that would prohibit consideration of sexual or affectional orientation as a factor in any judicial determination of child custody or visitation rights. Rather, child custody cases should be evaluated solely on the merits of which party is the better parent, without regard to that person's sexual and affectional orientation."

Lindagriffith.com (1978-01-15). Retrieved on 2014-07-25.Del Martin

Dorothy Louise Taliaferro "Del" Martin (May 5, 1921 – August 27, 2008) and Phyllis Ann Lyon (November 10, 1924 – April 9, 2020) were an American lesbian couple known as feminist and gay-rights activists.

Martin and Lyon met in 1950 ...

was the first open lesbian elected to NOW's board of directors, and Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon were the first lesbian couple to join NOW.Charlotte Bunch

Charlotte Bunch (born October 13, 1944) is an American feminist author and organizer in women's rights and human rights movements. Bunch is currently the founding director and senior scholar at the Center for Women's Global Leadership at Rutger ...

, Rita Mae Brown

Rita Mae Brown (born November 28, 1944) is an American feminist writer, best known for her coming-of-age autobiographical novel, ''Rubyfruit Jungle''. Brown was active in a number of civil rights campaigns and criticized the marginalization of le ...

, Adrienne Rich

Adrienne Cecile Rich ( ; May 16, 1929 – March 27, 2012) was an American poet, essayist and feminist. She was called "one of the most widely read and influential poets of the second half of the 20th century", and was credited with bringing "the ...

, Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde (; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde; February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was an American writer, womanist, radical feminist, professor, and civil rights activist. She was a self-described "black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet," wh ...

, Marilyn Frye, and Mary Daly.

Lesbian separatism

Feminist separatism is the theory that feminist opposition to patriarchy can be achieved through women's separation from men.Christine Skelton, Becky Francis, ''Feminism and the Schooling Scandal'', Taylor & Francis, 2009 ,p. 104 Because much of ...

, a subset of lesbian feminism, became popular in the 1970s as some lesbians doubted whether mainstream society or even the LGBT movement had anything to offer them. In 1970, seven women (including Del Martin) confronted the North Conference of Homophile eaning homosexualOrganizations about the relevance of the gay rights movement to the women within it. The delegates passed a resolution in favor of women's liberation, but Del Martin felt they had not done enough, and wrote "If That's All There Is", an influential 1970 essay in which she decried gay rights organizations as sexist.[Mark Blasius, Shane Phela]

We are everywhere: a historical sourcebook in gay and lesbian politics

Routledge, 1997 p. 352[Vern L. Bulloug]

Before Stonewall: activists for gay and lesbian rights in historical context

Routledge, 2002 p. 160 In the summer of 1971, a lesbian group calling themselves "The Furies

The Erinyes ( ; sing. Erinys ; grc, Ἐρινύες, pl. of ), also known as the Furies, and the Eumenides, were female chthonic deities of vengeance in ancient Greek religion and mythology. A formulaic oath in the ''Iliad'' invokes ...

" formed a commune open to lesbians only, where they put out a monthly newspaper. "The Furies" consisted of twelve women, aged eighteen to twenty-eight, all feminists, all lesbians, all white, with three children among them.[Dudley Clendinen, Adam Nagourne]

Out for Good: The Struggle to Build a Gay Rights Movement in America

Simon & Schuster, 2001 , p. 104 They shared chores and clothes, lived together, held some of their money in common, and slept on mattresses on a common floor.[Bonnie Zimmerma]

Lesbian histories and cultures: an encyclopedia

Garland Pub., 2000 , p. 322 the commune itself ended in 1972.[ Penny A. Weiss, Marilyn Friedma]

Feminism and community

Temple University Press, 1995 p. 131 In 1973, lesbian separatist and cultural critic Jill Johnston published '' Lesbian Nation'', after scandalizing Norman Mailer and others in attendance at a 1971 New York debate on feminism by kissing and rolling around the floor with another woman and announcing, "All women are lesbians, except those who don't know it yet."

Olivia Records

Olivia Records is a women's music record label founded in 1973 by lesbian members of the Washington D.C. area. It was founded by Ginny Berson, Cris Williamson, Meg Christian, Judy Dlugacz, and six other women. Olivia Records sold more than one m ...

was a collective founded in 1973 to record and market women's music

Women's music is music by women, for women, and about women. The genre emerged as a musical expression of the second-wave feminist movement as well as the labor, civil rights, and peace movements. The movement (in the USA) was started by lesbia ...

. Olivia Records, named after the heroine of a 1949 pulp novel

Pulp magazines (also referred to as "the pulps") were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 to the late 1950s. The term "pulp" derives from the cheap wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed. In contrast, magazine ...

by Dorothy Bussy

Dorothy Bussy ( Strachey; 24 July 1865 – 1 May 1960) was an English novelist and translator, close to the Bloomsbury Group.

Family background and childhood

Dorothy Bussy was a member of the Strachey family, one of ten children of Jane St ...

who fell in love with her headmistress at French boarding school (the heroine and the novel both being named ''Olivia''), was the brainchild of ten lesbian feminists (the Furies and Radicalesbians

This article addresses the history of lesbianism in the United States. Unless otherwise noted, the members of same-sex female couples discussed here are not known to be lesbian (rather than, for example, bisexual), but they are mentioned as part ...

) living in Washington, D.C. who wanted to create a feminist organization with an economic base. The Lesbian Herstory Archives

The Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA) is a New York City-based archive, community center, and museum dedicated to preserving lesbian history, located in Park Slope, Brooklyn. The Archives contain the world's largest collection of materials by and a ...

, a New York City-based archive, community center, and museum dedicated to preserving lesbian history, located in Park Slope, Brooklyn, was founded in 1974. It was founded by lesbian members of the Gay Academic Union who had organized a group to discuss sexism within that organization, specifically Joan Nestle

Joan Nestle (born May 12, 1940) is a Lambda Award winning writer and editor and a founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, which holds, among other things, everything she has ever written. She is openly lesbian and sees her work of archiving hi ...

, Deborah Edel, Sahli Cavallo, Pamela Oline, and Julia Stanley.

Lesbian activist Barbara Gittings

Barbara Gittings (July 31, 1932 – February 18, 2007) was a prominent American activist for LGBT equality. She organized the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) from 1958 to 1963, edited the national DOB magazine ''The Ladd ...

remained in the LGBT movement in the 1970s. In that decade, Gittings was most involved in the American Library Association

The American Library Association (ALA) is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that promotes libraries and library education internationally. It is the oldest and largest library association in the world, with 49,727 members ...

, especially its gay caucus, the first such in a professional organization, in order to promote positive literature about homosexuality in libraries. She was also involved in getting homosexuality accepted by psychiatry, and was a discussion leader for the American Psychiatric Association panel on "Life Styles of Non-Patient Homosexuals," which included Del Martin as one of six panelists.[Gallo, p. 176] In 1972, she organized the appearance of "Dr. H. Anonymous," a gay psychiatrist who appeared wearing a mask to conceal his identity and joined a panel that she and others participated in titled "Psychiatry: Friend or Foe to Homosexuals? A Dialogue".[Nancy D. Polikof]

Beyond straight and gay marriage: valuing all families under the law

Beacon Press, 2008 p. 38 Also in 1972, and again in 1976 and 1978, Barbara organized and staffed exhibits on homosexuality at yearly APA conferences.sex segregated

Sex segregation, sex separation, gender segregation or gender separation is the physical, legal, or cultural separation of people according to their biological sex. Sex segregation can refer simply to the physical and spatial separation by sex w ...

womyn's land communities,Michigan Womyn's Music Festival

The Michigan Womyn's Music Festival, often referred to as MWMF or Michfest, was a feminist women's music festival held annually from 1976 to 2015 in Oceana County, Michigan, on privately owned woodland near Hart Township referred to as "The L ...

.

1970s Political action

In the 1970s open lesbians also began their first forays into American politics. In 1972,

In the 1970s open lesbians also began their first forays into American politics. In 1972, Nancy Wechsler

Nancy Wechsler is an activist, writer, and former member of the Ann Arbor, Michigan#Law and government, Ann Arbor City Council, where she came out as a lesbian while serving her term.

Elected to the City Council alongside fellow Human Rights Part ...

became the first openly gay or lesbian person in political office in America; she was elected to the Ann Arbor City Council in 1972 as a member of the Human Rights Party and came out as a lesbian during her first and only term there.[Gay Politicians](_blank)

eQualityGiving. Retrieved on 2010-11-30. That same year, Madeline Davis became the first openly lesbian delegate elected to a major political convention when she was elected to the Democratic National Convention in Miami, Florida

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

. She addressed the convention in support of the inclusion of a gay rights plank in the Democratic Party platform. In 1974, Elaine Noble became the first openly gay or lesbian candidate ever elected to a state-level office in America when she was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives.Kathy Kozachenko

Kathy Kozachenko (born 1953) is an American politician who was List of the first LGBT holders of political offices, the first Coming out, openly lesbian or gay candidate to run successfully for political office in the United States.{{cite news, las ...

, who was elected to the Ann Arbor City Council in April 1974. In 1977, Anne Kronenberg

Anne Kronenberg is an American political administrator and LGBT rights activist. She is best known for being Harvey Milk's campaign manager during his historic San Francisco Board of Supervisors campaign in 1977 and his aide as he held that office ...

was Harvey Milk's campaign manager during his San Francisco Board of Supervisors campaign, and she later worked as his aide while he held that office. (While Kronenberg identified as a lesbian at that time, she later fell in love with and married a man she met in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

in the 1980s.[ ]) In 1978, lesbian Sally Miller Gearhart fought alongside Harvey Milk

Harvey Bernard Milk (May 22, 1930 – November 27, 1978) was an American politician and the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Milk was born and raised in ...

to defeat Proposition 6 (also known as the " Briggs Initiative" because it was sponsored by John Briggs), which would have banned gays and lesbians from teaching in public schools in California.[The Resurrection of Harvey Milk , People](_blank)

. The Advocate. Retrieved on 2010-11-30. Gearhart debated John Briggs about the initiative, which was defeated.The Times of Harvey Milk

''The Times of Harvey Milk'' is a 1984 American documentary film that premiered at the Telluride Film Festival, the New York Film Festival, and then on November 1, 1984, at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco. The film was directed by Rob Epstein, ...

'', which also included Gearhart talking about working with Milk against Proposition 6, and appearances by Kronenberg.

In 1979, the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights

The first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights was a large political rally that took place in Washington, D.C. on October 14, 1979. The first such march on Washington, it drew between 75,000 and 125,000Ghaziani, Amin. 2008. ''T ...

was held, in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

on October 14. It drew between 75,000 and 125,000[Ghaziani, Amin. 2008. "The Dividends of Dissent: How Conflict and Culture Work in Lesbian and Gay Marches on Washington". The University of Chicago Press.] people together to demand equal civil rights and urge the passage of protective civil rights legislation.Charlotte Bunch

Charlotte Bunch (born October 13, 1944) is an American feminist author and organizer in women's rights and human rights movements. Bunch is currently the founding director and senior scholar at the Center for Women's Global Leadership at Rutger ...

and Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde (; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde; February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was an American writer, womanist, radical feminist, professor, and civil rights activist. She was a self-described "black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet," wh ...

were the only out lesbians who spoke at the main rally.

San Francisco lesbian bar Peg's Placevice squad

A vice is a practice, behaviour, or habit generally considered immoral, sinful, criminal, rude, taboo, depraved, degrading, deviant or perverted in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refer to a fault, a negative character tr ...

, an event which drew national attention to other incidents of anti-gay violence and police harassment of the LGBT community and helped propel a (unsuccessful) citywide proposition to ban the city's vice squad altogether. Historians have written about the incident when describing the tension that existed between the police and the LGBT community during the late 1970s.

1970s Conflict between some lesbian feminists and transgender women

The 1970s also saw conflict between the transgender and lesbian communities in America. A dispute began in 1973, when the West Coast Lesbian Conference split over a scheduled performance by the lesbian transgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through ...

folk-singer Beth Elliott

Beth Elliott (born 1950) is an American trans lesbian folk singer, activist, and writer. In the early 1970s Elliot was involved with the Daughters of Bilitis and the West Coast Lesbian Conference in California. She became the centre of a controv ...

, who had helped to create the conference and was on its organization committee as well as having been asked to perform as a singer in the conference's entertainment program.Robin Morgan

Robin Morgan (born January 29, 1941) is an American poet, writer, activist, journalist, lecturer and former child actor. Since the early 1960s, she has been a key radical feminist member of the American Women's Movement, and a leader in the ...

gave her address, which she had altered after the events of the previous night.Daughters of Bilitis

The Daughters of Bilitis , also called the DOB or the Daughters, was the first lesbian civil and political rights organization in the United States. The organization, formed in San Francisco in 1955, was conceived as a social alternative to le ...

, and edited the chapter's newsletter, ''Sisters'', but was expelled from the DOB in 1973 because she was transgender, as were all transgender women.Del Martin

Dorothy Louise Taliaferro "Del" Martin (May 5, 1921 – August 27, 2008) and Phyllis Ann Lyon (November 10, 1924 – April 9, 2020) were an American lesbian couple known as feminist and gay-rights activists.

Martin and Lyon met in 1950 ...

announced the vote against transgender women in the DOB, the editorial staff of ''Sisters'' walked out, leaving the group over the decision.Olivia Records

Olivia Records is a women's music record label founded in 1973 by lesbian members of the Washington D.C. area. It was founded by Ginny Berson, Cris Williamson, Meg Christian, Judy Dlugacz, and six other women. Olivia Records sold more than one m ...

as Olivia's sound engineer

An audio engineer (also known as a sound engineer or recording engineer) helps to produce a recording or a live performance, balancing and adjusting sound sources using equalization, dynamics processing and audio effects, mixing, reproductio ...

from ca. 1974-1978, recording and mixing all Olivia product during this period. In 1979, lesbian radical feminist activist Janice Raymond released the book '' The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male'', which was a critique of a patriarchal medical and psychiatric establishment, and which maintained that transsexualism is based on the "patriarchal myths" of "male mothering," and "making of woman according to man's image." Raymond argued that this was done in order "to colonize feminist identification, culture, politics and sexuality," adding: "All transsexuals rape women's bodies by reducing the real female form to an artifact, appropriating this body for themselves .... Transsexuals merely cut off the most obvious means of invading women, so that they seem non-invasive." For example, in '' The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male''.[Raymond, Janice (1979). ''The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male.'' Teachers College Press, ] Raymond asserted that Sandy Stone was working to destroy the Olivia Records

Olivia Records is a women's music record label founded in 1973 by lesbian members of the Washington D.C. area. It was founded by Ginny Berson, Cris Williamson, Meg Christian, Judy Dlugacz, and six other women. Olivia Records sold more than one m ...

collective and womanhood in general with "male energy." In 1976, prior to publication, Raymond sent a draft of the chapter addressing Stone to the Olivia collective "for comment", possibly with the intention of outing Stone. However, Stone had informed the collective of her transgender status before joining. The collective replied that they disagreed with Raymond's description of transgender identity and that they felt differently about Stone's place in and effect on the collective. Raymond responded to this in the published version of her manuscript:

Masculine behavior is notably obtrusive. It is significant that transsexually constructed lesbian feminists have inserted themselves into positions of importance and/or performance in the feminist community. Sandy Stone, the transsexual engineer with Olivia Records, an "all-women" recording company, illustrates this well. Stone is not only crucial to the Olivia enterprise but plays a very dominant role there. The...visibility he achieved in the aftermath of the Olivia controversy...only serves to enhance his previously dominant role and to divide women, as men frequently do, when they make their presence necessary and vital to women. As one woman wrote: "I feel raped when Olivia passes off Sandy...as a real woman. After all his male privilege, is he going to cash in on lesbian feminist culture too?"

Members of the collective responded in turn by defending Stone in various publications. Stone remained a member of the women's collective and continued to record Olivia artists until political dissension over transgender topics, culminating in 1979 with the threat of a boycott of Olivia products. Finally, Stone resigned.

1970s–80s Lesbian/feminist sex wars

The lesbian sex wars

The feminist sex wars, also known as the lesbian sex wars, or simply the sex wars or porn wars, are terms used to refer to collective debates amongst feminists regarding a number of issues broadly relating to sexuality and sexual activity. Dif ...

, also known as the feminist sex wars, or simply the sex wars or porn wars, are debates amongst feminists regarding a number of issues broadly relating to sexuality and sexual activity, which polarized into two sides during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the aftermath of this polarization of feminist views during the sex wars continues to this day. The sides were characterized by anti-porn feminist and sex-positive feminist groups with disagreements regarding sexuality, including the role of trans women in the lesbian community, lesbian sexual practices, erotica

Erotica is literature or art that deals substantively with subject matter that is erotic, sexually stimulating or sexually arousing. Some critics regard pornography as a type of erotica, but many consider it to be different. Erotic art may use ...

, prostitution, sadomasochism and other sexual issues. The feminist movement was deeply divided as a result of these debates.Andrea Dworkin

Andrea Rita Dworkin (September 26, 1946 – April 9, 2005) was an American radical feminist writer and activist best known for her analysis of pornography. Her feminist writings, beginning in 1974, span 30 years. They are found in a dozen solo ...

gained national fame as a spokeswoman for the feminist anti-pornography movement, and for her writing on pornography and sexuality, particularly in ''Pornography: Men Possessing Women'' (1981) and ''Intercourse'' (1987), which remain her two most widely known books.

1970s–80s: Challenge to white feminists by lesbians of color

In 1977, a Bostonian

In 1977, a Bostonian Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ...

lesbian feminist organization called the Combahee River Collective

The Combahee River Collective ( ) was a Black feminist lesbian socialist organization active in Boston from 1974 to 1980. Marable, Manning; Leith Mullings (eds), ''Let Nobody Turn Us Around: Voices of Resistance, Reform, and Renewal'', Combahee ...

published their statement which is an important artifact for Black and/or lesbian feminism and the development of identity politics. The Combahee River Collective Statement made legible the concerns of Black women-loving women who felt as though they were being ignored by mainstream feminists and the civil rights movement. Their attention to overlapping oppressions and refusal to accept essentialist, universalizing feminist ideologies has helped to shape third-wave and contemporary feminism.

Another important feminist work published in the 1980s was '' This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color'', a feminist anthology edited by American lesbians Cherríe Moraga

Cherríe Moraga (born September 25, 1952) is a Chicana writer, feminist activist, poet, essayist, and playwright. She is part of the faculty at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the Department of English. Moraga is also a founding m ...

and Gloria E. Anzaldúa

Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa (September 26, 1942 – May 15, 2004) was an American scholar of Chicana feminism, cultural theory, and queer theory. She loosely based her best-known book, '' Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza'', on her li ...

. The anthology was first published in 1981 by Persephone Press, and the second edition was published in 1983 by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. The book was out in its third edition, published by Third Woman Press, until 2008, when its contract with Third Woman Press expired and it went out of print. ''This Bridge'' centered the experiences of women of color, offering a serious challenge to white feminists who made claims to solidarity based on sisterhood. Writings in the anthology, along with works by other prominent feminists of color, call for a greater prominence within feminism for race-related subjectivities, and ultimately laid the foundation for third wave feminism. ''This Bridge'' has become one of the most cited books in feminist theorizing. Another important event for lesbians of color was that " Becoming Visible: The First Black Lesbian Conference" was held at the Women's Building, from October 17 to 19, 1980. It has been credited as the first conference for African-American lesbian women.[Kyper, John. "Black Lesbians Meet in October." ''Coming Up: A Calendar of Events'' 1 (Oct. 1980): 1. Web.]

1980s: Lesbians and religion

Lesbians had some success in being integrated into religious life in the 1980s. In 1984 Reconstructionist Judaism became the first Jewish denomination to allow openly lesbian rabbis and cantors.Stacy Offner

Stacy Offner is an openly lesbian American rabbi.Alpert, R.T.Like Bread on the Seder Plate: Jewish Lesbians and the Transformation of Tradition Columbia University Press, 1998. became the first openly lesbian rabbi hired by a mainstream Jewish congregation, Shir Tikvah Congregation of Minneapolis (a Reform Jewish congregation).[Dana Evan Kapla]

Contemporary American Judaism: transformation and renewal

Columbia University Press, 2009 , p. 255[Our Roots](_blank)

Shir Tikvah. Retrieved on 2010-11-30. Years of debate in the 1980s also led to Reform Judaism deciding to allow openly lesbian rabbis and cantors in 1990.[Kress, Michae]

The Changing Face of the Rabbinate: Exclusively the territory of young men for so long, rabbinical schools today in the non-Orthodox movements are welcoming women and gay students

1990s: Victories and political power

'' In re Guardianship of Kowalski'', 478 N.W.2d 790 (Minn. Ct. App. 1991), was a Minnesota Court of Appeals case that established a lesbian's partner as her legal guardian after she (Sharon Kowalski) became incapacitated following an automobile accident. Because the case was contested by Kowalski's parents and family and initially resulted in the partner (Karen Thompson) being excluded for several years from visiting Kowalski, the gay community celebrated the final resolution in favor of the partner as a victory for gay rights.

The Lesbian Avengers

The Lesbian Avengers were founded in 1992 in New York City, the direct action group was formed with the intent to create an organization that focuses on lesbian issues and visibility through humorous and untraditional activism. The group was foun ...

began in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

in 1992 as "a direct action group focused on issues vital to lesbian survival and visibility."[Lesbian Avenger Organizing Handbook](_blank)

Retrieved 2009-3-4.[ Editors Janet Baus, Su Friedrich. (1993)] Dozens of other chapters quickly emerged worldwide, a few expanding their mission to include questions of gender, race, and class. Newsweek reporter Eloise Salholz, covering the 1993 LGBT March on Washington, believed the Lesbian Avengers were so popular because they were founded at a moment when lesbians were increasingly tired of working on issues, like AIDS and abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

, while their own problems went unsolved.[1993, Eloise Salholz, ''Newsweek'', "The Power and the Pride."] Most importantly, lesbians were frustrated with invisibility in society at large, and invisibility and misogyny

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women. It is a form of sexism that is used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practice ...

in the LGBT community.[Cohen, Ruth-Ellen]

Dale McCormick finds job as Treasurer challenging, rewarding

/ref> In 1991, Sherry Harris was elected to the City Council in Seattle, Washington, making her the first openly lesbian African-American elected official. In 1993, Roberta Achtenberg

Roberta Achtenberg (born July 20, 1950) is an American attorney who served as a commissioner on the United States Commission on Civil Rights. She was previously assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, becoming ...

became the first openly gay or lesbian person to be nominated by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate when she was appointed to the position of Assistant Secretary for Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity by President Bill Clinton.Deborah Batts

Deborah Anne Batts (April 13, 1947 – February 3, 2020) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. During Gay Pride Week in June 1994, Batts was sworn in as a United States distr ...

became the first openly gay or lesbian federal judge in 1994; she was appointed to the U.S. District Court in New York.[Batts, Deborah A. (b. 1947)](_blank)

'' glbtq.com''

[Deborah Batts: Online Resources](_blank)

. ''queertheory.com.'' In 1998 Tammy Baldwin

Tammy Suzanne Green Baldwin (born February 11, 1962) is an American lawyer and politician who has served as the junior United States senator from Wisconsin since 2013. A member of the Democratic Party, she served three terms in the Wisconsin St ...

became the first openly gay or lesbian non-incumbent ever elected to Congress, and the first open lesbian ever elected to Congress, winning Wisconsin's 2nd congressional district seat over

Josephine Musser.[NOW Calls Lesbian Rights Supporters to Unite in Strategy](_blank)

. Now.org (1999-02-04). Retrieved on 2010-11-30.

1990s: Lesbianism in the media

Entertainment also began to show more lesbian stories and openly lesbian performers. In 1991, the first lesbian kiss on television occurred on ''L.A. Law'' between the fictional characters of C.J. Lamb (played by Amanda Donohoe) and Abby (Michele Greene).

Entertainment also began to show more lesbian stories and openly lesbian performers. In 1991, the first lesbian kiss on television occurred on ''L.A. Law'' between the fictional characters of C.J. Lamb (played by Amanda Donohoe) and Abby (Michele Greene).[Fox Plans Sapphic Smooch for Party of Five ... Steve O'Donnell of Lateline Lets It All Out , The New York Observer](_blank)

. Observer.com (1999-01-31). Retrieved on 2010-11-30. Singer Melissa Etheridge

Melissa Lou Etheridge (born May 29, 1961) is an American singer, songwriter, musician, and guitarist. Her eponymous debut album was released in 1988 and became an underground success. It peaked at No. 22 on the ''Billboard'' 200 and its lead ...

came out as a lesbian in 1993, during the Triangle Ball, the first inaugural ball to ever be held in honor of gays and lesbians.[Back in the Day: Melissa Etheridge Comes Out](_blank)