History of geometry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Geometry

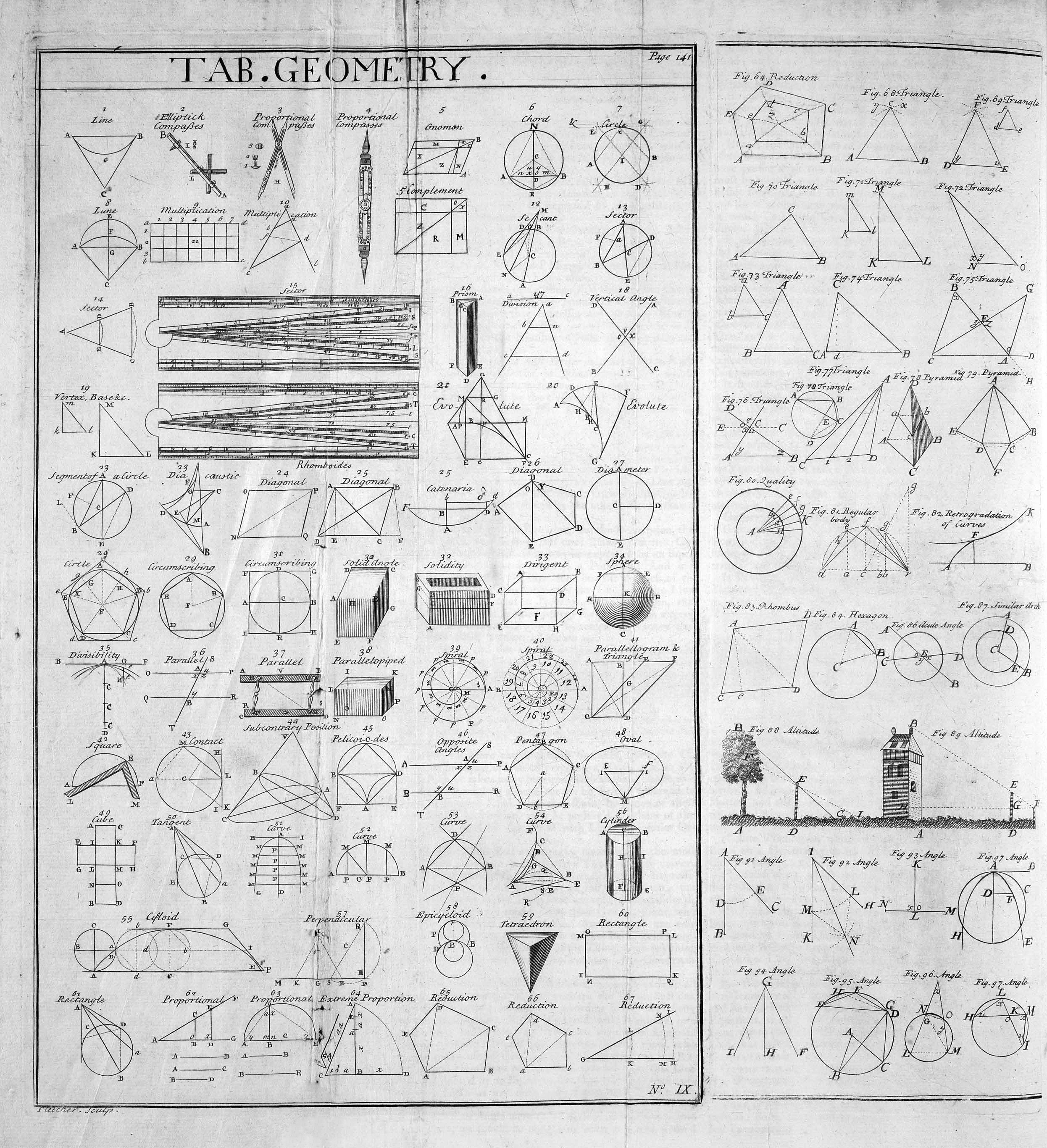

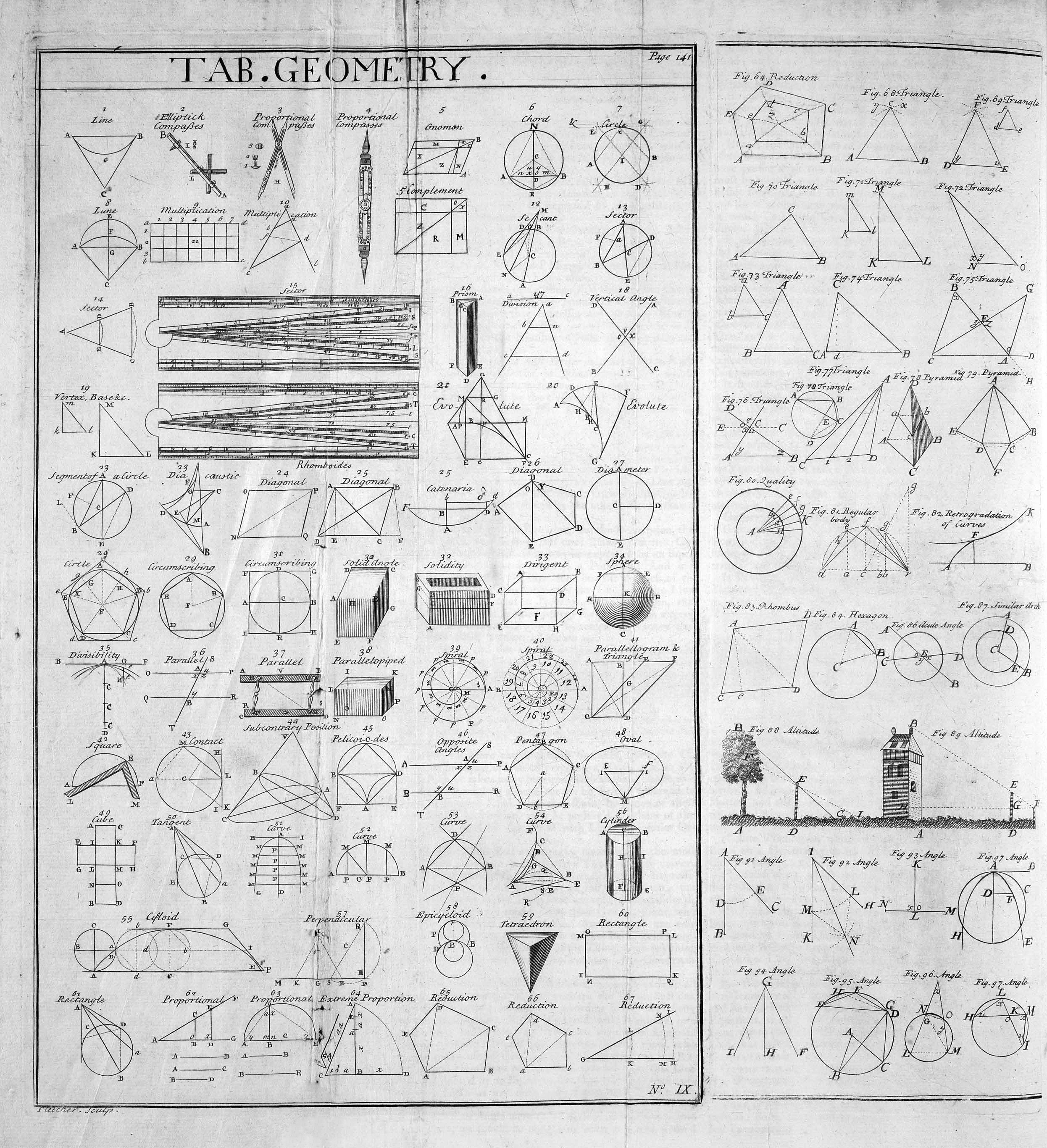

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

(from the grc, γεωμετρία; '' geo-'' "earth", '' -metron'' "measurement") arose as the field of knowledge dealing with spatial relationships. Geometry was one of the two fields of pre-modern mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, the other being the study of numbers (arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers— addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th ...

).

Classic geometry was focused in compass and straightedge constructions

In geometry, straightedge-and-compass construction – also known as ruler-and-compass construction, Euclidean construction, or classical construction – is the construction of lengths, angles, and other geometric figures using only an ideali ...

. Geometry was revolutionized by Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

, who introduced mathematical rigor and the axiomatic method

In mathematics and logic, an axiomatic system is any set of axioms from which some or all axioms can be used in conjunction to logically derive theorems. A theory is a consistent, relatively-self-contained body of knowledge which usually contai ...

still in use today. His book, '' The Elements'' is widely considered the most influential textbook of all time, and was known to all educated people in the West until the middle of the 20th century.

In modern times, geometric concepts have been generalized to a high level of abstraction and complexity, and have been subjected to the methods of calculus and abstract algebra, so that many modern branches of the field are barely recognizable as the descendants of early geometry. (See Areas of mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

and Algebraic geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics, classically studying zeros of multivariate polynomials. Modern algebraic geometry is based on the use of abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, for solving geometrical ...

.)

Early geometry

The earliest recorded beginnings of geometry can be traced to early peoples, such as the ancient Indus Valley (see Harappan mathematics) and ancientBabylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c ...

(see Babylonian mathematics) from around 3000 BC. Early geometry was a collection of empirically discovered principles concerning lengths, angles, areas, and volumes, which were developed to meet some practical need in surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

, construction

Construction is a general term meaning the art and science to form objects, systems, or organizations,"Construction" def. 1.a. 1.b. and 1.c. ''Oxford English Dictionary'' Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) Oxford University Press 2009 and ...

, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

, and various crafts. Among these were some surprisingly sophisticated principles, and a modern mathematician might be hard put to derive some of them without the use of calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizati ...

and algebra. For example, both the Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

and the Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

ians were aware of versions of the Pythagorean theorem about 1500 years before Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His poli ...

and the Indian Sulba Sutras around 800 BC contained the first statements of the theorem; the Egyptians had a correct formula for the volume of a frustum of a square pyramid.

Egyptian geometry

The ancient Egyptians knew that they could approximate the area of a circle as follows:Ray C. Jurgensen, Alfred J. Donnelly, and Mary P. Dolciani. Editorial Advisors Andrew M. Gleason, Albert E. Meder, Jr. ''Modern School Mathematics: Geometry'' (Student's Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1972, p. 52. . Teachers Edition . ::::Area of Circle ≈ (Diameter) x 8/9 sup>2. Problem 50 of theAhmes

Ahmes ( egy, jꜥḥ-ms “, a common Egyptian name also transliterated Ahmose) was an ancient Egyptian scribe who lived towards the end of the Fifteenth Dynasty (and of the Second Intermediate Period) and the beginning of the Eighteenth Dyna ...

papyrus uses these methods to calculate the area of a circle, according to a rule that the area is equal to the square of 8/9 of the circle's diameter. This assumes that is 4×(8/9)2 (or 3.160493...), with an error of slightly over 0.63 percent. This value was slightly less accurate than the calculations of the Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c ...

ns (25/8 = 3.125, within 0.53 percent), but was not otherwise surpassed until Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientis ...

' approximation of 211875/67441 = 3.14163, which had an error of just over 1 in 10,000.

Ahmes knew of the modern 22/7 as an approximation for , and used it to split a hekat, hekat x 22/x x 7/22 = hekat; however, Ahmes continued to use the traditional 256/81 value for for computing his hekat volume found in a cylinder.

Problem 48 involved using a square with side 9 units. This square was cut into a 3x3 grid. The diagonal of the corner squares were used to make an irregular octagon with an area of 63 units. This gave a second value for of 3.111...

The two problems together indicate a range of values for between 3.11 and 3.16.

Problem 14 in the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus gives the only ancient example finding the volume of a frustum of a pyramid, describing the correct formula:

:

where ''a'' and ''b'' are the base and top side lengths of the truncated pyramid and ''h'' is the height.

Babylonian geometry

The Babylonians may have known the general rules for measuring areas and volumes. They measured the circumference of a circle as three times the diameter and the area as one-twelfth the square of the circumference, which would be correct if '' π'' is estimated as 3. The volume of a cylinder was taken as the product of the base and the height, however, the volume of the frustum of a cone or a square pyramid was incorrectly taken as the product of the height and half the sum of the bases. The Pythagorean theorem was also known to the Babylonians. Also, there was a recent discovery in which a tablet used ''π'' as 3 and 1/8. The Babylonians are also known for the Babylonian mile, which was a measure of distance equal to about seven miles today. This measurement for distances eventually was converted to a time-mile used for measuring the travel of the Sun, therefore, representing time. There have been recent discoveries showing that ancient Babylonians may have discovered astronomical geometry nearly 1400 years before Europeans did.Vedic India geometry

The IndianVedic period

The Vedic period, or the Vedic age (), is the period in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of the history of India when the Vedic literature, including the Vedas (ca. 1300–900 BCE), was composed in the northern Indian subcontinent, betwe ...

had a tradition of geometry, mostly expressed in the construction of elaborate altars.

Early Indian texts (1st millennium BC) on this topic include the '' Satapatha Brahmana'' and the '' Śulba Sūtras''.

According to , the ''Śulba Sūtras'' contain "the earliest extant verbal expression of the Pythagorean Theorem in the world, although it had already been known to the Old Babylonians." The diagonal rope (') of an oblong (rectangle) produces both which the flank (''pārśvamāni'') and the horizontal (')They contain lists of Pythagorean triples, which are particular cases of Diophantine equations.: "The arithmetic content of the ''Śulva Sūtras'' consists of rules for finding Pythagorean triples such as (3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), (8, 15, 17), and (12, 35, 37). It is not certain what practical use these arithmetic rules had. The best conjecture is that they were part of religious ritual. A Hindu home was required to have three fires burning at three different altars. The three altars were to be of different shapes, but all three were to have the same area. These conditions led to certain "Diophantine" problems, a particular case of which is the generation of Pythagorean triples, so as to make one square integer equal to the sum of two others." They also contain statements (that with hindsight we know to be approximate) aboutproduce separately."

squaring the circle

Squaring the circle is a problem in geometry first proposed in Greek mathematics. It is the challenge of constructing a square with the area of a circle by using only a finite number of steps with a compass and straightedge. The difficul ...

and "circling the square.": "The requirement of three altars of equal areas but different shapes would explain the interest in transformation of areas. Among other transformation of area problems the Hindus considered in particular the problem of squaring the circle. The ''Bodhayana Sutra'' states the converse problem of constructing a circle equal to a given square. The following approximate construction is given as the solution.... this result is only approximate. The authors, however, made no distinction between the two results. In terms that we can appreciate, this construction gives a value for π of 18 (3 − 2), which is about 3.088."

The ''Baudhayana Sulba Sutra'', the best-known and oldest of the ''Sulba Sutras'' (dated to the 8th or 7th century BC) contains examples of simple Pythagorean triples, such as: , , , , and as well as a statement of the Pythagorean theorem for the sides of a square: "The rope which is stretched across the diagonal of a square produces an area double the size of the original square." It also contains the general statement of the Pythagorean theorem (for the sides of a rectangle): "The rope stretched along the length of the diagonal of a rectangle makes an area which the vertical and horizontal sides make together."

According to mathematician S. G. Dani, the Babylonian cuneiform tablet Plimpton 322 written c. 1850 BC "contains fifteen Pythagorean triples with quite large entries, including (13500, 12709, 18541) which is a primitive triple, indicating, in particular, that there was sophisticated understanding on the topic" in Mesopotamia in 1850 BC. "Since these tablets predate the Sulbasutras period by several centuries, taking into account the contextual appearance of some of the triples, it is reasonable to expect that similar understanding would have been there in India." Dani goes on to say:

"As the main objective of the ''Sulvasutras'' was to describe the constructions of altars and the geometric principles involved in them, the subject of Pythagorean triples, even if it had been well understood may still not have featured in the ''Sulvasutras''. The occurrence of the triples in the ''Sulvasutras'' is comparable to mathematics that one may encounter in an introductory book on architecture or another similar applied area, and would not correspond directly to the overall knowledge on the topic at that time. Since, unfortunately, no other contemporaneous sources have been found it may never be possible to settle this issue satisfactorily."In all, three ''Sulba Sutras'' were composed. The remaining two, the ''Manava Sulba Sutra'' composed by Manava (

fl.

''Floruit'' (; abbreviated fl. or occasionally flor.; from Latin for "they flourished") denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the unabbreviated word may also be used as a noun indicatin ...

750-650 BC) and the ''Apastamba Sulba Sutra'', composed by Apastamba (c. 600 BC), contained results similar to the ''Baudhayana Sulba Sutra''.

Greek geometry

Classical Greek geometry

For the ancient Greek mathematicians, geometry was the crown jewel of their sciences, reaching a completeness and perfection of methodology that no other branch of their knowledge had attained. They expanded the range of geometry to many new kinds of figures, curves, surfaces, and solids; they changed its methodology from trial-and-error to logical deduction; they recognized that geometry studies "eternal forms", or abstractions, of which physical objects are only approximations; and they developed the idea of the "axiomatic method", still in use today.Thales and Pythagoras

Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

(635-543 BC) of Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' ( exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in ...

(now in southwestern Turkey), was the first to whom deduction in mathematics is attributed. There are five geometric propositions for which he wrote deductive proofs, though his proofs have not survived. Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His poli ...

(582-496 BC) of Ionia, and later, Italy, then colonized by Greeks, may have been a student of Thales, and traveled to Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

. The theorem that bears his name may not have been his discovery, but he was probably one of the first to give a deductive proof of it. He gathered a group of students around him to study mathematics, music, and philosophy, and together they discovered most of what high school students learn today in their geometry courses. In addition, they made the profound discovery of incommensurable lengths and irrational numbers.

Plato

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

(427-347 BC) was a philosopher, highly esteemed by the Greeks. There is a story that he had inscribed above the entrance to his famous school, "Let none ignorant of geometry enter here." However, the story is considered to be untrue. Though he was not a mathematician himself, his views on mathematics had great influence. Mathematicians thus accepted his belief that geometry should use no tools but compass and straightedge – never measuring instruments such as a marked ruler or a protractor

A protractor is a measuring instrument, typically made of transparent plastic or glass, for measuring angles.

Some protractors are simple half-discs or full circles. More advanced protractors, such as the bevel protractor, have one or two sw ...

, because these were a workman's tools, not worthy of a scholar. This dictum led to a deep study of possible compass and straightedge

In geometry, straightedge-and-compass construction – also known as ruler-and-compass construction, Euclidean construction, or classical construction – is the construction of lengths, angles, and other geometric figures using only an ideali ...

constructions, and three classic construction problems: how to use these tools to trisect an angle

Angle trisection is a classical problem of straightedge and compass construction of ancient Greek mathematics. It concerns construction of an angle equal to one third of a given arbitrary angle, using only two tools: an unmarked straightedge an ...

, to construct a cube twice the volume of a given cube, and to construct a square equal in area to a given circle. The proofs of the impossibility of these constructions, finally achieved in the 19th century, led to important principles regarding the deep structure of the real number system. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

(384-322 BC), Plato's greatest pupil, wrote a treatise on methods of reasoning used in deductive proofs (see Logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

) which was not substantially improved upon until the 19th century.

Hellenistic geometry

Euclid

Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

(c. 325-265 BC), of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, probably a student at the Academy founded by Plato, wrote a treatise in 13 books (chapters), titled '' The Elements of Geometry'', in which he presented geometry in an ideal axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

atic form, which came to be known as Euclidean geometry. The treatise is not a compendium of all that the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

mathematicians knew at the time about geometry; Euclid himself wrote eight more advanced books on geometry. We know from other references that Euclid's was not the first elementary geometry textbook, but it was so much superior that the others fell into disuse and were lost. He was brought to the university at Alexandria by Ptolemy I

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedo ...

, King of Egypt.

''The Elements'' began with definitions of terms, fundamental geometric principles (called ''axioms'' or ''postulates''), and general quantitative principles (called ''common notions'') from which all the rest of geometry could be logically deduced. Following are his five axioms, somewhat paraphrased to make the English easier to read.

# Any two points can be joined by a straight line.

# Any finite straight line can be extended in a straight line.

# A circle can be drawn with any center and any radius.

# All right angles are equal to each other.

# If two straight lines in a plane are crossed by another straight line (called the transversal), and the interior angles between the two lines and the transversal lying on one side of the transversal add up to less than two right angles, then on that side of the transversal, the two lines extended will intersect (also called the parallel postulate).

Concepts, that are now understood as algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

, were expressed geometrically by Euclid, a method referred to as Greek geometric algebra.

Archimedes

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientis ...

(287-212 BC), of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, when it was a Greek city-state

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

, is often considered to be the greatest of the Greek mathematicians, and occasionally even named as one of the three greatest of all time (along with Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

and Carl Friedrich Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; german: Gauß ; la, Carolus Fridericus Gauss; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and science. Sometimes refer ...

). Had he not been a mathematician, he would still be remembered as a great physicist, engineer, and inventor. In his mathematics, he developed methods very similar to the coordinate systems of analytic geometry, and the limiting process of integral calculus. The only element lacking for the creation of these fields was an efficient algebraic notation in which to express his concepts.

After Archimedes

After Archimedes, Hellenistic mathematics began to decline. There were a few minor stars yet to come, but the golden age of geometry was over.Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor ( grc-gre, Πρόκλος ὁ Διάδοχος, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophe ...

(410-485), author of ''Commentary on the First Book of Euclid'', was one of the last important players in Hellenistic geometry. He was a competent geometer, but more importantly, he was a superb commentator on the works that preceded him. Much of that work did not survive to modern times, and is known to us only through his commentary. The Roman Republic and Empire that succeeded and absorbed the Greek city-states produced excellent engineers, but no mathematicians of note.

The great Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, t ...

was later burned. There is a growing consensus among historians that the Library of Alexandria likely suffered from several destructive events, but that the destruction of Alexandria's pagan temples in the late 4th century was probably the most severe and final one. The evidence for that destruction is the most definitive and secure. Caesar's invasion may well have led to the loss of some 40,000-70,000 scrolls in a warehouse adjacent to the port (as Luciano Canfora argues, they were likely copies produced by the Library intended for export), but it is unlikely to have affected the Library or Museum, given that there is ample evidence that both existed later.

Civil wars, decreasing investments in maintenance and acquisition of new scrolls and generally declining interest in non-religious pursuits likely contributed to a reduction in the body of material available in the Library, especially in the 4th century. The Serapeum was certainly destroyed by Theophilus in 391, and the Museum and Library may have fallen victim to the same campaign.

Classical Indian geometry

In the Bakhshali manuscript, there is a handful of geometric problems (including problems about volumes of irregular solids). The Bakhshali manuscript also "employs a decimal place value system with a dot for zero." Aryabhata's ''Aryabhatiya

''Aryabhatiya'' (IAST: ') or ''Aryabhatiyam'' ('), a Sanskrit astronomical treatise, is the '' magnum opus'' and only known surviving work of the 5th century Indian mathematician Aryabhata. Philosopher of astronomy Roger Billard estimates that ...

'' (499) includes the computation of areas and volumes.

Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the '' Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established doctrine of Brahma", dated 628), a theoretical tr ...

wrote his astronomical work '' '' in 628. Chapter 12, containing 66 Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

verses, was divided into two sections: "basic operations" (including cube roots, fractions, ratio and proportion, and barter) and "practical mathematics" (including mixture, mathematical series, plane figures, stacking bricks, sawing of timber, and piling of grain). In the latter section, he stated his famous theorem on the diagonals of a cyclic quadrilateral:

Brahmagupta's theorem: If a cyclic quadrilateral has diagonals that are perpendicular

In elementary geometry, two geometric objects are perpendicular if they intersect at a right angle (90 degrees or π/2 radians). The condition of perpendicularity may be represented graphically using the '' perpendicular symbol'', ⟂. It c ...

to each other, then the perpendicular line drawn from the point of intersection of the diagonals to any side of the quadrilateral always bisects the opposite side.

Chapter 12 also included a formula for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral (a generalization of Heron's formula), as well as a complete description of rational triangle

An integer triangle or integral triangle is a triangle all of whose sides have lengths that are integers. A rational triangle can be defined as one having all sides with rational length; any such rational triangle can be integrally rescaled (ca ...

s (''i.e.'' triangles with rational sides and rational areas).

Brahmagupta's formula: The area, ''A'', of a cyclic quadrilateral with sides of lengths ''a'', ''b'', ''c'', ''d'', respectively, is given by

:

where ''s'', the semiperimeter

In geometry, the semiperimeter of a polygon is half its perimeter. Although it has such a simple derivation from the perimeter, the semiperimeter appears frequently enough in formulas for triangles and other figures that it is given a separate ...

, given by:

Brahmagupta's Theorem on rational triangles: A triangle with rational sides and rational area is of the form:

:

for some rational numbers and .

Chinese geometry

The first definitive work (or at least oldest existent) on geometry in China was the '' Mo Jing'', theMohist

Mohism or Moism (, ) was an ancient Chinese philosophy of ethics and logic, rational thought, and science developed by the academic scholars who studied under the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 BC – c. 391 BC), embodied in an eponym ...

canon of the early philosopher Mozi

Mozi (; ; Latinized as Micius ; – ), original name Mo Di (), was a Chinese philosopher who founded the school of Mohism during the Hundred Schools of Thought period (the early portion of the Warring States period, –221 BCE). The ancie ...

(470-390 BC). It was compiled years after his death by his followers around the year 330 BC. Although the ''Mo Jing'' is the oldest existent book on geometry in China, there is the possibility that even older written material existed. However, due to the infamous Burning of the Books in a political maneuver by the Qin Dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

ruler Qin Shihuang (r. 221-210 BC), multitudes of written literature created before his time were purged. In addition, the ''Mo Jing'' presents geometrical concepts in mathematics that are perhaps too advanced not to have had a previous geometrical base or mathematic background to work upon.

The ''Mo Jing'' described various aspects of many fields associated with physical science, and provided a small wealth of information on mathematics as well. It provided an 'atomic' definition of the geometric point, stating that a line is separated into parts, and the part which has no remaining parts (i.e. cannot be divided into smaller parts) and thus forms the extreme end of a line is a point.Needham, Volume 3, 91. Much like Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

's first and third definitions and Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's 'beginning of a line', the ''Mo Jing'' stated that "a point may stand at the end (of a line) or at its beginning like a head-presentation in childbirth. (As to its invisibility) there is nothing similar to it."Needham, Volume 3, 92. Similar to the atomists of Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

, the ''Mo Jing'' stated that a point is the smallest unit, and cannot be cut in half, since 'nothing' cannot be halved. It stated that two lines of equal length will always finish at the same place, while providing definitions for the ''comparison of lengths'' and for ''parallels'',Needham, Volume 3, 92-93. along with principles of space and bounded space.Needham, Volume 3, 93. It also described the fact that planes without the quality of thickness cannot be piled up since they cannot mutually touch.Needham, Volume 3, 93-94. The book provided definitions for circumference, diameter, and radius, along with the definition of volume.Needham, Volume 3, 94.

The Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

(202 BC-220 AD) period of China witnessed a new flourishing of mathematics. One of the oldest Chinese mathematical texts to present geometric progressions was the '' Suàn shù shū'' of 186 BC, during the Western Han era. The mathematician, inventor, and astronomer Zhang Heng

Zhang Heng (; AD 78–139), formerly romanized as Chang Heng, was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman who lived during the Han dynasty. Educated in the capital cities of Luoyang and Chang'an, he achieved success as an astronomer, mat ...

(78-139 AD) used geometrical formulas to solve mathematical problems. Although rough estimates for pi ( π) were given in the ''Zhou Li

The ''Rites of Zhou'' (), originally known as "Officers of Zhou" () is a work on bureaucracy and organizational theory. It was renamed by Liu Xin to differentiate it from a chapter in the '' Book of History'' by the same name. To replace a lost ...

'' (compiled in the 2nd century BC),Needham, Volume 3, 99. it was Zhang Heng who was the first to make a concerted effort at creating a more accurate formula for pi. Zhang Heng approximated pi as 730/232 (or approx 3.1466), although he used another formula of pi in finding a spherical volume, using the square root of 10 (or approx 3.162) instead. Zu Chongzhi (429-500 AD) improved the accuracy of the approximation of pi to between 3.1415926 and 3.1415927, with 355⁄113 (密率, Milü, detailed approximation) and 22⁄7 (约率, Yuelü, rough approximation) being the other notable approximation.Needham, Volume 3, 101. In comparison to later works, the formula for pi given by the French mathematician Franciscus Vieta (1540-1603) fell halfway between Zu's approximations.

''The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art''

'' The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art'', the title of which first appeared by 179 AD on a bronze inscription, was edited and commented on by the 3rd century mathematicianLiu Hui

Liu Hui () was a Chinese mathematician who published a commentary in 263 CE on ''Jiu Zhang Suan Shu ( The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art).'' He was a descendant of the Marquis of Zixiang of the Eastern Han dynasty and lived in the state ...

from the Kingdom of Cao Wei

Wei ( Hanzi: 魏; pinyin: ''Wèi'' < : *''ŋjweiC'' < Pythagorean theorem. The book provided illustrated proof for the Pythagorean theorem,Needham, Volume 3, 22. contained a written dialogue between of the earlier

Islamic Geometry

Geometry in the 19th Century

at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

{{History of science

Duke of Zhou

Dan, Duke Wen of Zhou (), commonly known as the Duke of Zhou (), was a member of the royal family of the early Zhou dynasty who played a major role in consolidating the kingdom established by his elder brother King Wu. He was renowned for actin ...

and Shang Gao on the properties of the right angle triangle and the Pythagorean theorem, while also referring to the astronomical gnomon

A gnomon (; ) is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

History

A painted stick dating from 2300 BC that was excavated at the astronomical site of Taosi is the ...

, the circle and square, as well as measurements of heights and distances.Needham, Volume 3, 21. The editor Liu Hui listed pi as 3.141014 by using a 192 sided polygon

In geometry, a polygon () is a plane figure that is described by a finite number of straight line segments connected to form a closed '' polygonal chain'' (or ''polygonal circuit''). The bounded plane region, the bounding circuit, or the two ...

, and then calculated pi as 3.14159 using a 3072 sided polygon. This was more accurate than Liu Hui's contemporary Wang Fan, a mathematician and astronomer from Eastern Wu

Wu (Chinese: 吳; pinyin: ''Wú''; Middle Chinese *''ŋuo'' < : ''*ŋuɑ''), known in hi ...

, would render pi as 3.1555 by using 142⁄45.Needham, Volume 3, 100. Liu Hui also wrote of mathematical surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

to calculate distance measurements of depth, height, width, and surface area. In terms of solid geometry, he figured out that a wedge with rectangular base and both sides sloping could be broken down into a pyramid and a tetrahedral wedge.Needham, Volume 3, 98–99. He also figured out that a wedge with trapezoid

A quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides is called a trapezoid () in American and Canadian English. In British and other forms of English, it is called a trapezium ().

A trapezoid is necessarily a convex quadrilateral in Eu ...

base and both sides sloping could be made to give two tetrahedral wedges separated by a pyramid. Furthermore, Liu Hui described Cavalieri's principle

In geometry, Cavalieri's principle, a modern implementation of the method of indivisibles, named after Bonaventura Cavalieri, is as follows:

* 2-dimensional case: Suppose two regions in a plane are included between two parallel lines in that pl ...

on volume, as well as Gaussian elimination

In mathematics, Gaussian elimination, also known as row reduction, is an algorithm for solving systems of linear equations. It consists of a sequence of operations performed on the corresponding matrix of coefficients. This method can also be used ...

. From the ''Nine Chapters'', it listed the following geometrical formulas that were known by the time of the Former Han Dynasty (202 BCE–9 CE).

Areas for theNeedham, Volume 3, 98.

*Square

*Rectangle

*Circle

*Isosceles triangle

In geometry, an isosceles triangle () is a triangle that has two sides of equal length. Sometimes it is specified as having ''exactly'' two sides of equal length, and sometimes as having ''at least'' two sides of equal length, the latter versio ...

* Rhomboid

*Trapezoid

A quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides is called a trapezoid () in American and Canadian English. In British and other forms of English, it is called a trapezium ().

A trapezoid is necessarily a convex quadrilateral in Eu ...

*Double trapezium

*Segment of a circle

*Annulus ('ring' between two concentric circles)

Volumes for the

*Parallelepiped with two square surfaces

*Parallelepiped with no square surfaces

*Pyramid

* Frustum of pyramid with square base

*Frustum of pyramid with rectangular base of unequal sides

*Cube

* Prism

*Wedge with rectangular base and both sides sloping

*Wedge with trapezoid base and both sides sloping

* Tetrahedral wedge

*Frustum of a wedge of the second type (used for applications in engineering)

*Cylinder

*Cone with circular base

*Frustum of a cone

*Sphere

Continuing the geometrical legacy of ancient China, there were many later figures to come, including the famed astronomer and mathematician Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

(1031-1095 CE), Yang Hui

Yang Hui (, ca. 1238–1298), courtesy name Qianguang (), was a Chinese mathematician and writer during the Song dynasty. Originally, from Qiantang (modern Hangzhou, Zhejiang), Yang worked on magic squares, magic circles and the binomial theo ...

(1238-1298) who discovered Pascal's Triangle, Xu Guangqi (1562-1633), and many others.

Islamic Golden Age

By the beginning of the 9th century, the "Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

" flourished, the establishment of the House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, بيت الحكمة, Bayt al-Ḥikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

marking a separate tradition of science in the medieval Islamic world

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids in Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate ...

, building not only Hellenistic but also on Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

sources.

Although the Islamic mathematicians are most famed for their work on algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

, number theory

Number theory (or arithmetic or higher arithmetic in older usage) is a branch of pure mathematics devoted primarily to the study of the integers and integer-valued functions. German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) said, "Ma ...

and number systems, they also made considerable contributions to geometry, trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

and mathematical astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

, and were responsible for the development of algebraic geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics, classically studying zeros of multivariate polynomials. Modern algebraic geometry is based on the use of abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, for solving geometrical ...

.

Al-Mahani (born 820) conceived the idea of reducing geometrical problems such as duplicating the cube to problems in algebra. Al-Karaji

( fa, ابو بکر محمد بن الحسن الکرجی; c. 953 – c. 1029) was a 10th-century Persian mathematician and engineer who flourished at Baghdad. He was born in Karaj, a city near Tehran. His three principal surviving works a ...

(born 953) completely freed algebra from geometrical operations and replaced them with the arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers— addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th ...

al type of operations which are at the core of algebra today.

Thābit ibn Qurra (known as Thebit in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

) (born 836) contributed to a number of areas in mathematics, where he played an important role in preparing the way for such important mathematical discoveries as the extension of the concept of number to ( positive) real number

In mathematics, a real number is a number that can be used to measure a ''continuous'' one-dimensional quantity such as a distance, duration or temperature. Here, ''continuous'' means that values can have arbitrarily small variations. Every ...

s, integral calculus, theorems in spherical trigonometry, analytic geometry

In classical mathematics, analytic geometry, also known as coordinate geometry or Cartesian geometry, is the study of geometry using a coordinate system. This contrasts with synthetic geometry.

Analytic geometry is used in physics and enginee ...

, and non-Euclidean geometry. In astronomy Thabit was one of the first reformers of the Ptolemaic system, and in mechanics he was a founder of statics

Statics is the branch of classical mechanics that is concerned with the analysis of force and torque (also called moment) acting on physical systems that do not experience an acceleration (''a''=0), but rather, are in static equilibrium with ...

. An important geometrical aspect of Thabit's work was his book on the composition of ratios. In this book, Thabit deals with arithmetical operations applied to ratios of geometrical quantities. The Greeks had dealt with geometric quantities but had not thought of them in the same way as numbers to which the usual rules of arithmetic could be applied. By introducing arithmetical operations on quantities previously regarded as geometric and non-numerical, Thabit started a trend which led eventually to the generalisation of the number concept.

In some respects, Thabit is critical of the ideas of Plato and Aristotle, particularly regarding motion. It would seem that here his ideas are based on an acceptance of using arguments concerning motion in his geometrical arguments. Another important contribution Thabit made to geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

was his generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, which he extended from special right triangles to all triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, any three points, when non- colline ...

s in general, along with a general proof

Proof most often refers to:

* Proof (truth), argument or sufficient evidence for the truth of a proposition

* Alcohol proof, a measure of an alcoholic drink's strength

Proof may also refer to:

Mathematics and formal logic

* Formal proof, a c ...

.

Ibrahim ibn Sinan ibn Thabit (born 908), who introduced a method of integration more general than that of Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientis ...

, and al-Quhi (born 940) were leading figures in a revival and continuation of Greek higher geometry in the Islamic world. These mathematicians, and in particular Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

, studied optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

and investigated the optical properties of mirrors made from conic section

In mathematics, a conic section, quadratic curve or conic is a curve obtained as the intersection of the surface of a cone with a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a ...

s.

Astronomy, time-keeping and geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

provided other motivations for geometrical and trigonometrical research. For example, Ibrahim ibn Sinan and his grandfather Thabit ibn Qurra both studied curves required in the construction of sundials. Abu'l-Wafa and Abu Nasr Mansur both applied spherical geometry

300px, A sphere with a spherical triangle on it.

Spherical geometry is the geometry of the two-dimensional surface of a sphere. In this context the word "sphere" refers only to the 2-dimensional surface and other terms like "ball" or "solid sp ...

to astronomy.

A 2007 paper in the journal ''Science'' suggested that girih tiles possessed properties consistent with self-similar

__NOTOC__

In mathematics, a self-similar object is exactly or approximately similar to a part of itself (i.e., the whole has the same shape as one or more of the parts). Many objects in the real world, such as coastlines, are statistically se ...

fractal

In mathematics, a fractal is a geometric shape containing detailed structure at arbitrarily small scales, usually having a fractal dimension strictly exceeding the topological dimension. Many fractals appear similar at various scales, as ill ...

quasicrystalline tilings such as the Penrose tilings.

Renaissance

The transmission of the Greek Classics to medieval Europe via theArabic literature

Arabic literature ( ar, الأدب العربي / ALA-LC: ''al-Adab al-‘Arabī'') is the writing, both as prose and poetry, produced by writers in the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is '' Adab'', which is derived from ...

of the 9th to 10th century "Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

" began in the 10th century and culminated in the Latin translations of the 12th century

Latin translations of the 12th century were spurred by a major search by European scholars for new learning unavailable in western Europe at the time; their search led them to areas of southern Europe, particularly in central Spain and Sicily, ...

.

A copy of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it can ...

'' was brought back to Sicily by Henry Aristippus (d. 1162), as a gift from the Emperor to King William I (r. 1154–1166). An anonymous student at Salerno travelled to Sicily and translated the ''Almagest'' as well as several works by Euclid from Greek to Latin. Although the Sicilians generally translated directly from the Greek, when Greek texts were not available, they would translate from Arabic. Eugenius of Palermo Eugenius of Palermo (also Eugene) ( la, Eugenius Siculus, el, Εὐγενἠς Εὐγένιος ὁ τῆς Πανόρμου, it, Eugenio da Palermo; 1130 – 1202) was an '' amiratus'' (admiral) of the Kingdom of Sicily in the late twelfth cent ...

(d. 1202) translated Ptolemy's ''Optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

'' into Latin, drawing on his knowledge of all three languages in the task.

The rigorous deductive methods of geometry found in Euclid's ''Elements of Geometry'' were relearned, and further development of geometry in the styles of both Euclid ( Euclidean geometry) and Khayyam (algebraic geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics, classically studying zeros of multivariate polynomials. Modern algebraic geometry is based on the use of abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, for solving geometrical ...

) continued, resulting in an abundance of new theorems and concepts, many of them very profound and elegant.

Advances in the treatment of perspective were made in Renaissance art

Renaissance art (1350 – 1620 AD) is the painting, sculpture, and decorative arts of the period of European history known as the Renaissance, which emerged as a distinct style in Italy in about AD 1400, in parallel with developments which occ ...

of the 14th to 15th century which went beyond what had been achieved in antiquity.

In Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of ancient Greek and Roman thought ...

of the '' Quattrocento'', concepts of architectural order were explored and rules were formulated. A prime example of is the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

by Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo Brunelleschi ( , , also known as Pippo; 1377 – 15 April 1446), considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture, was an Italian architect, designer, and sculptor, and is now recognized to be the first modern engineer, p ...

(1377–1446).

In c. 1413 Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo Brunelleschi ( , , also known as Pippo; 1377 – 15 April 1446), considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture, was an Italian architect, designer, and sculptor, and is now recognized to be the first modern engineer, p ...

demonstrated the geometrical method of perspective, used today by artists, by painting the outlines of various Florentine buildings onto a mirror.

Soon after, nearly every artist in Florence and in Italy used geometrical perspective in their paintings, notably Masolino da Panicale and Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello ( ), was a Florentine sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used this to develop a complete Renaissance st ...

. Melozzo da Forlì first used the technique of upward foreshortening (in Rome, Loreto, Forlì

Forlì ( , ; rgn, Furlè ; la, Forum Livii) is a '' comune'' (municipality) and city in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, and is the capital of the province of Forlì-Cesena. It is the central city of Romagna.

The city is situated along the Vi ...

and others), and was celebrated for that. Not only was perspective a way of showing depth, it was also a new method of composing a painting. Paintings began to show a single, unified scene, rather than a combination of several.

As shown by the quick proliferation of accurate perspective paintings in Florence, Brunelleschi likely understood (with help from his friend the mathematician Toscanelli

Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (1397 – 10 May 1482) was an Italian mathematician, astronomer,, pp. 333–335 and cosmographer.

Life

Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli was born in Florence, the son of the physician Domenico Toscanelli. There is no ...

), but did not publish, the mathematics behind perspective. Decades later, his friend Leon Battista Alberti wrote '' De pictura'' (1435/1436), a treatise on proper methods of showing distance in painting based on Euclidean geometry. Alberti was also trained in the science of optics through the school of Padua and under the influence of Biagio Pelacani da Parma

Blasius of Parma (Biagio Pelacani da Parma) (c. 13501416) was an Italian philosopher, mathematician and astrologer.

He popularised English and French philosophical work in Italy, where he associated both with scholastics and with early Renaissance ...

who studied Alhazen's ''Optics'.

Piero della Francesca elaborated on Della Pittura in his '' De Prospectiva Pingendi'' in the 1470s. Alberti had limited himself to figures on the ground plane and giving an overall basis for perspective. Della Francesca fleshed it out, explicitly covering solids in any area of the picture plane. Della Francesca also started the now common practice of using illustrated figures to explain the mathematical concepts, making his treatise easier to understand than Alberti's. Della Francesca was also the first to accurately draw the Platonic solids as they would appear in perspective.

Perspective remained, for a while, the domain of Florence. Jan van Eyck

Jan van Eyck ( , ; – July 9, 1441) was a painter active in Bruges who was one of the early innovators of what became known as Early Netherlandish painting, and one of the most significant representatives of Early Northern Renaissance art. A ...

, among others, was unable to create a consistent structure for the converging lines in paintings, as in London's The Arnolfini Portrait, because he was unaware of the theoretical breakthrough just then occurring in Italy. However he achieved very subtle effects by manipulations of scale in his interiors. Gradually, and partly through the movement of academies of the arts, the Italian techniques became part of the training of artists across Europe, and later other parts of the world.

The culmination of these Renaissance traditions finds its ultimate synthesis in the research of the architect, geometer, and optician Girard Desargues on perspective, optics and projective geometry.

The '' Vitruvian Man'' by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

(c. 1490)The Secret Language of the Renaissance - Richard Stemp depicts a man in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart and inscribed in a circle and square. The drawing is based on the correlations of ideal human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

in Book III of his treatise ''De Architectura

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide ...

''.

Modern geometry

The 17th century

In the early 17th century, there were two important developments in geometry. The first and most important was the creation ofanalytic geometry

In classical mathematics, analytic geometry, also known as coordinate geometry or Cartesian geometry, is the study of geometry using a coordinate system. This contrasts with synthetic geometry.

Analytic geometry is used in physics and enginee ...

, or geometry with coordinates

In geometry, a coordinate system is a system that uses one or more numbers, or coordinates, to uniquely determine the position of the points or other geometric elements on a manifold such as Euclidean space. The order of the coordinates is sig ...

and equation

In mathematics, an equation is a formula that expresses the equality of two expressions, by connecting them with the equals sign . The word ''equation'' and its cognates in other languages may have subtly different meanings; for example, in F ...

s, by René Descartes (1596–1650) and Pierre de Fermat

Pierre de Fermat (; between 31 October and 6 December 1607 – 12 January 1665) was a French mathematician who is given credit for early developments that led to infinitesimal calculus, including his technique of adequality. In particular, he ...

(1601–1665). This was a necessary precursor to the development of calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizati ...

and a precise quantitative science of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

. The second geometric development of this period was the systematic study of projective geometry by Girard Desargues (1591–1661). Projective geometry is the study of geometry without measurement, just the study of how points align with each other. There had been some early work in this area by Hellenistic geometers, notably Pappus (c. 340). The greatest flowering of the field occurred with Jean-Victor Poncelet

Jean-Victor Poncelet (; 1 July 1788 – 22 December 1867) was a French engineer and mathematician who served most notably as the Commanding General of the École Polytechnique. He is considered a reviver of projective geometry, and his work '' ...

(1788–1867).

In the late 17th century, calculus was developed independently and almost simultaneously by Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

(1642–1727) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of ...

(1646–1716). This was the beginning of a new field of mathematics now called analysis

Analysis ( : analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (3 ...

. Though not itself a branch of geometry, it is applicable to geometry, and it solved two families of problems that had long been almost intractable: finding tangent lines to odd curves, and finding areas enclosed by those curves. The methods of calculus reduced these problems mostly to straightforward matters of computation.

The 18th and 19th centuries

Non-Euclidean geometry

The very old problem of proving Euclid's Fifth Postulate, the " Parallel Postulate", from his first four postulates had never been forgotten. Beginning not long after Euclid, many attempted demonstrations were given, but all were later found to be faulty, through allowing into the reasoning some principle which itself had not been proved from the first four postulates. Though Omar Khayyám was also unsuccessful in proving the parallel postulate, his criticisms of Euclid's theories of parallels and his proof of properties of figures in non-Euclidean geometries contributed to the eventual development of non-Euclidean geometry. By 1700 a great deal had been discovered about what can be proved from the first four, and what the pitfalls were in attempting to prove the fifth. Saccheri, Lambert, and Legendre each did excellent work on the problem in the 18th century, but still fell short of success. In the early 19th century, Gauss, Johann Bolyai, and Lobachevsky, each independently, took a different approach. Beginning to suspect that it was impossible to prove the Parallel Postulate, they set out to develop a self-consistent geometry in which that postulate was false. In this they were successful, thus creating the first non-Euclidean geometry. By 1854,Bernhard Riemann

Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann (; 17 September 1826 – 20 July 1866) was a German mathematician who made contributions to analysis, number theory, and differential geometry. In the field of real analysis, he is mostly known for the first ...

, a student of Gauss, had applied methods of calculus in a ground-breaking study of the intrinsic (self-contained) geometry of all smooth surfaces, and thereby found a different non-Euclidean geometry. This work of Riemann later became fundamental for Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for d ...

's theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical phenomena in ...

.

It remained to be proved mathematically that the non-Euclidean geometry was just as self-consistent as Euclidean geometry, and this was first accomplished by Beltrami in 1868. With this, non-Euclidean geometry was established on an equal mathematical footing with Euclidean geometry.

While it was now known that different geometric theories were mathematically possible, the question remained, "Which one of these theories is correct for our physical space?" The mathematical work revealed that this question must be answered by physical experimentation, not mathematical reasoning, and uncovered the reason why the experimentation must involve immense (interstellar, not earth-bound) distances. With the development of relativity theory in physics, this question became vastly more complicated.

Introduction of mathematical rigor

All the work related to the Parallel Postulate revealed that it was quite difficult for a geometer to separate his logical reasoning from his intuitive understanding of physical space, and, moreover, revealed the critical importance of doing so. Careful examination had uncovered some logical inadequacies in Euclid's reasoning, and some unstated geometric principles to which Euclid sometimes appealed. This critique paralleled the crisis occurring in calculus and analysis regarding the meaning of infinite processes such as convergence and continuity. In geometry, there was a clear need for a new set of axioms, which would be complete, and which in no way relied on pictures we draw or on our intuition of space. Such axioms, now known as Hilbert's axioms, were given byDavid Hilbert

David Hilbert (; ; 23 January 1862 – 14 February 1943) was a German mathematician, one of the most influential mathematicians of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Hilbert discovered and developed a broad range of fundamental ideas in many ...

in 1894 in his dissertation ''Grundlagen der Geometrie'' (''Foundations of Geometry''). Some other complete sets of axioms had been given a few years earlier, but did not match Hilbert's in economy, elegance, and similarity to Euclid's axioms.

Analysis situs, or topology

In the mid-18th century, it became apparent that certain progressions of mathematical reasoning recurred when similar ideas were studied on the number line, in two dimensions, and in three dimensions. Thus the general concept of a metric space was created so that the reasoning could be done in more generality, and then applied to special cases. This method of studying calculus- and analysis-related concepts came to be known as analysis situs, and later astopology

In mathematics, topology (from the Greek words , and ) is concerned with the properties of a geometric object that are preserved under continuous deformations, such as stretching, twisting, crumpling, and bending; that is, without closing ...

. The important topics in this field were properties of more general figures, such as connectedness and boundaries, rather than properties like straightness, and precise equality of length and angle measurements, which had been the focus of Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry. Topology soon became a separate field of major importance, rather than a sub-field of geometry or analysis.

The 20th century

Developments inalgebraic geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics, classically studying zeros of multivariate polynomials. Modern algebraic geometry is based on the use of abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, for solving geometrical ...

included the study of curves and surfaces over finite field

In mathematics, a finite field or Galois field (so-named in honor of Évariste Galois) is a field that contains a finite number of elements. As with any field, a finite field is a set on which the operations of multiplication, addition, subtr ...

s as demonstrated by the works of among others André Weil

André Weil (; ; 6 May 1906 – 6 August 1998) was a French mathematician, known for his foundational work in number theory and algebraic geometry. He was a founding member and the ''de facto'' early leader of the mathematical Bourbaki group. Th ...

, Alexander Grothendieck, and Jean-Pierre Serre as well as over the real or complex numbers. Finite geometry itself, the study of spaces with only finitely many points, found applications in coding theory and cryptography

Cryptography, or cryptology (from grc, , translit=kryptós "hidden, secret"; and ''graphein'', "to write", or '' -logia'', "study", respectively), is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of adv ...

. With the advent of the computer, new disciplines such as computational geometry

Computational geometry is a branch of computer science devoted to the study of algorithms which can be stated in terms of geometry. Some purely geometrical problems arise out of the study of computational geometric algorithms, and such problems ar ...

or digital geometry

Digital geometry deals with discrete sets (usually discrete point sets) considered to be digitized models or images of objects of the 2D or 3D Euclidean space.

Simply put, digitizing is replacing an object by a discrete set of its points. Th ...

deal with geometric algorithms, discrete representations of geometric data, and so forth.

Timeline

See also

* '' Flatland'', a book by "A. Square" about two– andthree-dimensional space

Three-dimensional space (also: 3D space, 3-space or, rarely, tri-dimensional space) is a geometric setting in which three values (called ''parameters'') are required to determine the position of an element (i.e., point). This is the informa ...

, to understand the concept of four dimensions

* History of mathematics

*History of measurement

The earliest recorded systems of weights and measures originate in the 3rd or 4th millennium BC. Even the very earliest civilizations needed measurement for purposes of agriculture, construction and trade. Early standard units might only have ap ...

* Important publications in geometry

*Interactive geometry software

Interactive geometry software (IGS) or dynamic geometry environments (DGEs) are computer programs which allow one to create and then manipulate geometric constructions, primarily in plane geometry. In most IGS, one starts construction by putting ...

* List of geometry topics

* Modern triangle geometry

Notes

References

* * * * * *Needham, Joseph

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, i ...

(1986), ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth'', Taipei

Taipei (), officially Taipei City, is the capital and a special municipality of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Located in Northern Taiwan, Taipei City is an enclave of the municipality of New Taipei City that sits about southwest of the ...

: Caves Books Ltd

*

*

External links

Islamic Geometry

Geometry in the 19th Century

at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

{{History of science