History of genetics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of genetics dates from the

The most influential early theories of heredity were that of

The most influential early theories of heredity were that of

The preformation theory is a developmental biological theory, which was represented in antiquity by the Greek philosopher

The preformation theory is a developmental biological theory, which was represented in antiquity by the Greek philosopher

Between 1856 and 1865,

Between 1856 and 1865,  Mendel's work was published in 1866 as ''"Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden" (

Mendel's work was published in 1866 as ''"Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden" (

In 1883 August Weismann conducted experiments involving breeding mice whose tails had been surgically removed. His results — that surgically removing a mouse's tail had no effect on the tail of its offspring — challenged the theories of pangenesis and Lamarckism, which held that changes to an organism during its lifetime could be inherited by its descendants. Weismann proposed the germ plasm theory of inheritance, which held that hereditary information was carried only in sperm and egg cells.Siddhartha Mukherjee, Mukherjee, Siddartha (2016) The Gene:An intimate history Chapter 5.

In 1883 August Weismann conducted experiments involving breeding mice whose tails had been surgically removed. His results — that surgically removing a mouse's tail had no effect on the tail of its offspring — challenged the theories of pangenesis and Lamarckism, which held that changes to an organism during its lifetime could be inherited by its descendants. Weismann proposed the germ plasm theory of inheritance, which held that hereditary information was carried only in sperm and egg cells.Siddhartha Mukherjee, Mukherjee, Siddartha (2016) The Gene:An intimate history Chapter 5.

In 1910,

In 1910,

Olby's "Mendel, Mendelism, and Genetics," at MendelWeb""Experiments in Plant Hybridization" (1866), by Johann Gregor Mendel," by A. Andrei at the Embryo Project Encyclopedia

* http://www.accessexcellence.org/AE/AEPC/WWC/1994/geneticstln.html * http://www.sysbioeng.com/index/cta94-11s.jpg * http://www.esp.org/books/sturt/history/ * http://cogweb.ucla.edu/ep/DNA_history.html * http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/sci_tech/2000/human_genome/749026.stm * https://web.archive.org/web/20120323085256/http://www.hchs.hunter.cuny.edu/wiki/index.php?title=Modern_Science&printable=yes * http://jem.rupress.org/content/79/2/137.full.pdf * http://www.nature.com/physics/looking-back/crick/Crick_Watson.pdf * * http://www.genomenewsnetwork.org/resources/timeline/1960_mRNA.php *https://web.archive.org/web/20120403041525/http://www.molecularstation.com/molecular-biology-images/data/503/MRNA-structure.png *http://www.genomenewsnetwork.org/resources/timeline/1973_Boyer.php *http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/180/2/709 * * * * http://www.cnn.com/TECH/9702/24/cloning.explainer/index.html * http://www.genome.gov/11006943 {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Genetics History of genetics, Genetics, * History of biology by subdiscipline, Genetics Gregor Mendel History of science by discipline, Genetics

classical era

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

with contributions by Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His poli ...

, Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influence ...

, and others. Modern genetics began with the work of the Augustinian friar Gregor Johann Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brünn (''Brno''), Margraviate of Moravia. Mendel was ...

. His work

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, in ...

on pea plants, published in 1866, provided the initial evidence that, on its rediscovery in 1900, helped to establish the theory of Mendelian inheritance

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularize ...

.

In ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

, Hippocrates suggested that all organs of the body of a parent gave off invisible “seeds,” miniaturized components, that were transmitted during sexual intercourse and combined in the mother’s womb to form a baby. In the Early Modern times, William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions in anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, the systemic circulation and propert ...

's

book ''On Animal Generation'' contradicted Aristotle's theories of genetics and embryology.

The 1900 rediscovery of Mendel's work by Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware o ...

, Carl Correns

Carl Erich Correns (19 September 1864 – 14 February 1933) was a German botanist and geneticist notable primarily for his independent discovery of the principles of heredity, which he achieved simultaneously but independently of the botanist ...

and Erich von Tschermak Erich Tschermak, Edler von Seysenegg (15 November 1871 – 11 October 1962) was an Austrian agronomist who developed several new disease-resistant crops, including wheat-rye and oat hybrids. He was a son of the Moravia-born mineralogist Gusta ...

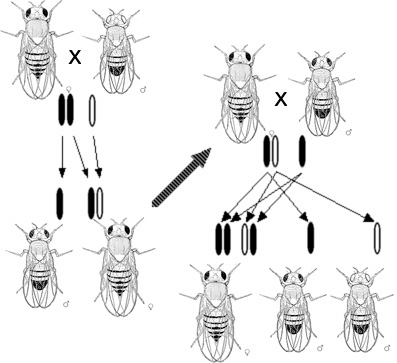

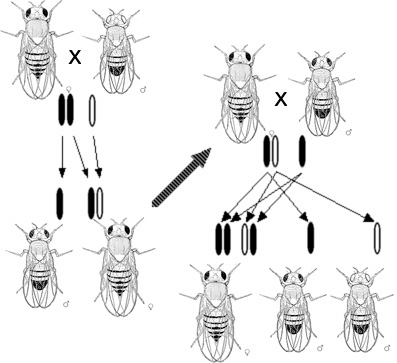

led to rapid advances in genetics. By 1915 the basic principles of Mendelian genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

had been studied in a wide variety of organisms — most notably the fruit fly ''Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (the taxonomic order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the " vinegar fly" or "pomace fly". Starting with ...

''. Led by Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role that ...

and his fellow "drosophilists", geneticists developed the Mendelian

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularize ...

model, which was widely accepted by 1925. Alongside experimental work, mathematicians developed the statistical framework of population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and po ...

, bringing genetic explanations into the study of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

.

With the basic patterns of genetic inheritance established, many biologists turned to investigations of the physical nature of the gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

. In the 1940s and early 1950s, experiments pointed to DNA as the portion of chromosomes (and perhaps other nucleoproteins) that held genes. A focus on new model organisms such as viruses and bacteria, along with the discovery of the double helical structure of DNA in 1953, marked the transition to the era of molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

.

In the following years, chemists developed techniques for sequencing both nucleic acids and proteins, while many others worked out the relationship between these two forms of biological molecules and discovered the genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

. The regulation of gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. T ...

became a central issue in the 1960s; by the 1970s gene expression could be controlled and manipulated through genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including ...

. In the last decades of the 20th century, many biologists focused on large-scale genetics projects, such as sequencing entire genomes.

Pre-Mendelian ideas on heredity

Ancient theories

The most influential early theories of heredity were that of

The most influential early theories of heredity were that of Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

. Hippocrates' theory (possibly based on the teachings of Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

) was similar to Darwin's later ideas on pangenesis

Pangenesis was Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity, in which he proposed that each part of the body continually emitted its own type of small organic particles called gemmules that aggregated in the gonads, contributing herita ...

, involving heredity material that collects from throughout the body. Aristotle suggested instead that the (nonphysical) form-giving principle of an organism was transmitted through semen (which he considered to be a purified form of blood) and the mother's menstrual blood, which interacted in the womb to direct an organism's early development. For both Hippocrates and Aristotle—and nearly all Western scholars through to the late 19th century—the inheritance of acquired characters

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

was a supposedly well-established fact that any adequate theory of heredity had to explain. At the same time, individual species were taken to have a fixed essence; such inherited changes were merely superficial. The Athenian philosopher Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influence ...

observed families and proposed the contribution of both males and females of hereditary characters ("sperm atoms"), noticed dominant and recessive types of inheritance and described segregation and independent assortment of "sperm atoms".

In the 9th century CE, the Afro-Arab

Afro-Arabs are Arabs of full or partial Black African descent. These include populations within mainly the Sudanese, Emiratis, Yemenis, Saudis, Omanis, Sahrawis, Mauritanians, Algerians, Egyptians and Moroccans, with considerably long est ...

writer Al-Jahiz

Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو عثمان عمرو بن بحر الكناني البصري), commonly known as al-Jāḥiẓ ( ar, links=no, الجاحظ, ''The Bug Eyed'', born 776 – died December 868/Jan ...

considered the effects of the environment

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, all living and non-living things occurring naturally

* Biophysical environment, the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism or ...

on the likelihood of an animal to survive. In 1000 CE, the Arab physician, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was ...

(known as Albucasis in the West) was the first physician to describe clearly the hereditary nature of haemophilia

Haemophilia, or hemophilia (), is a mostly inherited genetic disorder that impairs the body's ability to make blood clots, a process needed to stop bleeding. This results in people bleeding for a longer time after an injury, easy bruisin ...

in his ''Al-Tasrif

The ''Kitāb al-Taṣrīf'' ( ar, كتاب التصريف لمن عجز عن التأليف, lit=The Arrangement of Medical Knowledge for One Who is Not Able to Compile a Book for Himself), known in English as The Method of Medicine, is a 30-volume ...

''. In 1140 CE, Judah HaLevi

Judah Halevi (also Yehuda Halevi or ha-Levi; he, יהודה הלוי and Judah ben Shmuel Halevi ; ar, يهوذا اللاوي ''Yahuḏa al-Lāwī''; 1075 – 1141) was a Spanish Jewish physician, poet and philosopher. He was born in Spain, ...

described dominant and recessive genetic traits in The Kuzari.

Preformation theory

Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

. It reappeared in modern times in the 17th century and then prevailed until the 19th century. Another common term at that time was the theory of evolution, although "evolution" (in the sense of development as a pure growth process) had a completely different meaning than today. The preformists assumed that the entire organism was preformed in the sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, ...

(animalkulism) or in the egg (ovism or ovulism) and only had to unfold and grow. This was contrasted by the theory of epigenesis, according to which the structures and organs of an organism only develop in the course of individual development (Ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the s ...

). Epigenesis had been the dominant opinion since antiquity and into the 17th century, but was then replaced by preformist ideas. Since the 19th century epigenesis was again able to establish itself as a view valid to this day.

Plant systematics and hybridization

In the 18th century, with increased knowledge of plant and animal diversity and the accompanying increased focus ontaxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

, new ideas about heredity began to appear. Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

and others (among them Joseph Gottlieb Kölreuter

Joseph Gottlieb Kölreuter (27 April 1733 – 11 November 1806), also spelled ''Koelreuter'' or ''Kohlreuter'', was a German botanist who pioneered the study of plant fertilization, hybridization and was the first to detect self-incompatibility. ...

, Carl Friedrich von Gärtner, and Charles Naudin

Charles Victor Naudin (14 August 1815 in Autun – 19 March 1899 in Antibes) was a French naturalist and botanist.

Biography

Naudin studied at Bailleul-sur-Thérain in 1825, at Limoux, and at the University of Montpellier from which he grad ...

) conducted extensive experiments with hybridisation, especially hybrids between species. Species hybridizers described a wide variety of inheritance phenomena, include hybrid sterility and the high variability of back-crosses.

Plant breeders were also developing an array of stable varieties

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

in many important plant species. In the early 19th century, Augustin Sageret established the concept of dominance, recognizing that when some plant varieties are crossed, certain characteristics (present in one parent) usually appear in the offspring; he also found that some ancestral characteristics found in neither parent may appear in offspring. However, plant breeders made little attempt to establish a theoretical foundation for their work or to share their knowledge with current work of physiology, although Gartons Agricultural Plant Breeders

Dr John Garton, of the firm of Garton Brothers of Newton-le-Willows in the United Kingdom was the Originator of Scientific Farm Plant Breeding. He is credited as the first scientist to show that the common grain crops and many other plants are ...

in England explained their system.

Mendel

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brünn (''Brno''), Margraviate of Moravia. Mendel was ...

conducted breeding experiments using the pea plant ''Pisum sativum'' and traced the inheritance patterns of certain traits. Through these experiments, Mendel saw that the genotypes and phenotypes of the progeny were predictable and that some traits were dominant over others. These patterns of Mendelian inheritance

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularize ...

demonstrated the usefulness of applying statistics to inheritance. They also contradicted 19th-century theories of blending inheritance

Blending may refer to:

* The process of mixing in process engineering

* Mixing paints to achieve a greater range of colors

* Blending (alcohol production), a technique to produce alcoholic beverages by mixing different brews

* Blending (linguisti ...

, showing, rather, that genes remain discrete through multiple generations of hybridization.

From his statistical analysis, Mendel defined a concept that he described as a character (which in his mind holds also for "determinant of that character"). In only one sentence of his historical paper, he used the term "factors" to designate the "material creating" the character: " So far as experience goes, we find it in every case confirmed that constant progeny can only be formed when the egg cells and the fertilizing pollen are off like the character so that both are provided with the material for creating quite similar individuals, as is the case with the normal fertilization of pure species. We must, therefore, regard it as certain that exactly similar factors must be at work also in the production of the constant forms in the hybrid plants."(Mendel, 1866).

Experiments on Plant Hybridization

"Experiments on Plant Hybridization" (German: "Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden") is a seminal paper written in 1865 and published in 1866 by Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian friar considered to be the founder of modern genetics. The paper was the r ...

)'' in the ''Verhandlungen des Naturforschenden Vereins zu Brünn (Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn)'', following two lectures he gave on the work in early 1865.

Post-Mendel, pre-rediscovery

Pangenesis

Mendel's work was published in a relatively obscure scientific journal, and it was not given any attention in the scientific community. Instead, discussions about modes of heredity were galvanized by Darwin's theory ofevolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

by natural selection, in which mechanisms of non-Lamarckian

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

heredity seemed to be required. Darwin's own theory of heredity, pangenesis

Pangenesis was Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity, in which he proposed that each part of the body continually emitted its own type of small organic particles called gemmules that aggregated in the gonads, contributing herita ...

, did not meet with any large degree of acceptance. A more mathematical version of pangenesis, one which dropped much of Darwin's Lamarckian holdovers, was developed as the "biometrical" school of heredity by Darwin's cousin, Francis Galton.

Germ plasm

Rediscovery of Mendel

Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware o ...

wondered what the nature of germ plasm might be, and in particular he wondered whether or not germ plasm was mixed like paint or whether the information was carried in discrete packets that remained unbroken. In the 1890s he was conducting breeding experiments with a variety of plant species and in 1897 he published a paper on his results that stated that each inherited trait was governed by two discrete particles of information, one from each parent, and that these particles were passed along intact to the next generation. In 1900 he was preparing another paper on his further results when he was shown a copy of Mendel's 1866 paper by a friend who thought it might be relevant to de Vries's work. He went ahead and published his 1900 paper without mentioning Mendel's priority. Later that same year another botanist, Carl Correns

Carl Erich Correns (19 September 1864 – 14 February 1933) was a German botanist and geneticist notable primarily for his independent discovery of the principles of heredity, which he achieved simultaneously but independently of the botanist ...

, who had been conducting hybridization experiments with maize and peas, was searching the literature for related experiments prior to publishing his own results when he came across Mendel's paper, which had results similar to his own. Correns accused de Vries of appropriating terminology from Mendel's paper without crediting him or recognizing his priority. At the same time another botanist, Erich von Tschermak Erich Tschermak, Edler von Seysenegg (15 November 1871 – 11 October 1962) was an Austrian agronomist who developed several new disease-resistant crops, including wheat-rye and oat hybrids. He was a son of the Moravia-born mineralogist Gusta ...

was experimenting with pea breeding and producing results like Mendel's. He too discovered Mendel's paper while searching the literature for relevant work. In a subsequent paper de Vries praised Mendel and acknowledged that he had only extended his earlier work.

Emergence of molecular genetics

After the rediscovery of Mendel's work there was a feud between William Bateson and Karl Pearson, Pearson over the hereditary mechanism, solved by Ronald Fisher in his work "The Correlation Between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance". In 1910,

In 1910, Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role that ...

showed that genes reside on specific chromosomes. He later showed that genes occupy specific locations on the chromosome. With this knowledge, Alfred Sturtevant, a member of Morgan's famous fly room, using ''Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (the taxonomic order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the " vinegar fly" or "pomace fly". Starting with ...

,'' provided the first chromosomal map of any biological organism. In 1928, Frederick Griffith showed that genes could be transferred. In what is now known as Griffith's experiment, injections into a mouse of a deadly strain of bacteria that had been heat-killed transferred genetic information to a safe strain of the same bacteria, killing the mouse.

A series of subsequent discoveries led to the realization decades later that the genetic material is made of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and not, as was widely believed until then, of proteins. In 1941, George Wells Beadle and Edward Lawrie Tatum showed that mutations in genes caused errors in specific steps of metabolic pathways. This showed that specific genes code for specific proteins, leading to the "one gene, one enzyme" hypothesis. Oswald Avery, Colin Munro MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty Avery-MacLeod-McCarty experiment, showed in 1944 that DNA holds the gene's information. In 1952, Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling produced a strikingly clear x-ray diffraction pattern indicating a helical form. Using these x-rays and information already known about the chemistry of DNA, James D. Watson and Francis Crick demonstrated the molecular structure of DNA in 1953. Together, these discoveries established the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that proteins are translated from RNA which is transcribed by DNA. This dogma has since been shown to have exceptions, such as reverse transcription in retroviruses.

In 1972, Walter Fiers and his team at the University of Ghent were the first to determine the sequence of a gene: the gene for bacteriophage MS2 coat protein. Richard J. Roberts and Phillip Sharp discovered in 1977 that genes can be split into segments. This led to the idea that one gene can make several proteins. The successful sequencing of many organisms' genomes has complicated the molecular definition of the gene. In particular, genes do not always sit side by side on DNA like discrete beads. Instead, regions of the DNA producing distinct proteins may overlap, so that the idea emerges that "genes are one long Continuum (theory), continuum". It was first hypothesized in 1986 by Walter Gilbert that neither DNA nor protein would be required in such a primitive system as that of a very early stage of the earth if RNA could serve both as a catalyst and as genetic information storage processor.

The modern study of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

at the level of DNA is known as molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

and the synthesis of molecular genetics with traditional Charles Darwin, Darwinian evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

is known as the Modern synthesis (20th century), modern evolutionary synthesis.

See also

* List of sequenced eukaryotic genomes * History of molecular biology * History of RNA biology, History of RNA Biology * History of evolutionary thought * One gene-one enzyme hypothesis * Phage groupReferences

Further reading

* Elof Axel Carlson, ''Mendel's Legacy: The Origin of Classical Genetics'' (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2004.)External links

Olby's "Mendel, Mendelism, and Genetics," at MendelWeb

* http://www.accessexcellence.org/AE/AEPC/WWC/1994/geneticstln.html * http://www.sysbioeng.com/index/cta94-11s.jpg * http://www.esp.org/books/sturt/history/ * http://cogweb.ucla.edu/ep/DNA_history.html * http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/sci_tech/2000/human_genome/749026.stm * https://web.archive.org/web/20120323085256/http://www.hchs.hunter.cuny.edu/wiki/index.php?title=Modern_Science&printable=yes * http://jem.rupress.org/content/79/2/137.full.pdf * http://www.nature.com/physics/looking-back/crick/Crick_Watson.pdf * * http://www.genomenewsnetwork.org/resources/timeline/1960_mRNA.php *https://web.archive.org/web/20120403041525/http://www.molecularstation.com/molecular-biology-images/data/503/MRNA-structure.png *http://www.genomenewsnetwork.org/resources/timeline/1973_Boyer.php *http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/180/2/709 * * * * http://www.cnn.com/TECH/9702/24/cloning.explainer/index.html * http://www.genome.gov/11006943 {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Genetics History of genetics, Genetics, * History of biology by subdiscipline, Genetics Gregor Mendel History of science by discipline, Genetics