History of fluorine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

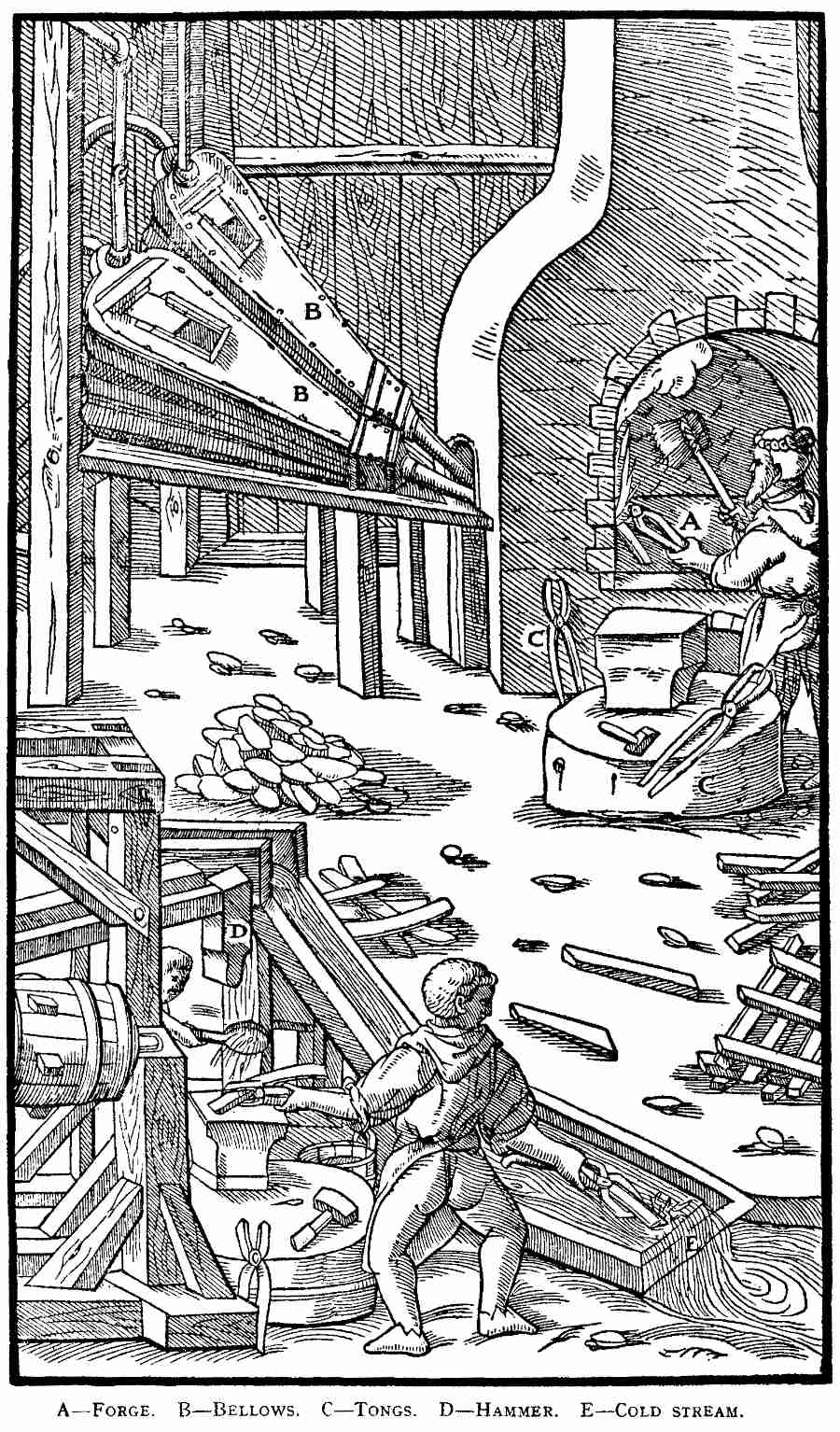

Fluorine is a relatively new element in human applications. In ancient times, only minor uses of fluorine-containing minerals existed. The industrial use of fluorite, fluorine's source mineral, was first described by early scientist Georgius Agricola in the 16th century, in the context of smelting. The name "fluorite" (and later "fluorine") derives from Agricola's invented Latin terminology. In the late 18th century,

Some instances of ancient use of fluorite, main source mineral of fluorine, for ornamental use carvings exist. However, archeological finds are rare, perhaps in part because of the stone's softness. Two Roman cups made of Persian fluorite have been discovered and are currently exhibited at the British museum. Pliny the Elder described a soft stone from Persia used in cups that may have been fluorite. Fluorite carvings from about 1000 AD have been discovered in the Americas in Indian burial grounds.

Some instances of ancient use of fluorite, main source mineral of fluorine, for ornamental use carvings exist. However, archeological finds are rare, perhaps in part because of the stone's softness. Two Roman cups made of Persian fluorite have been discovered and are currently exhibited at the British museum. Pliny the Elder described a soft stone from Persia used in cups that may have been fluorite. Fluorite carvings from about 1000 AD have been discovered in the Americas in Indian burial grounds.

The word "fluorine" derives from the Latin stem of the main source mineral, fluorite, which was first mentioned in 1529 by Georgius Agricola, the "father of mineralogy". He described fluorite as a

The word "fluorine" derives from the Latin stem of the main source mineral, fluorite, which was first mentioned in 1529 by Georgius Agricola, the "father of mineralogy". He described fluorite as a

Some sources claim that the first production of hydrofluoric acid was by Heinrich Schwanhard, a German glass cutter, in 1670. A peer-reviewed study of Schwanhard's writings, though, showed no specific mention of fluorite and only discussion of an extremely strong acid. It was hypothesized that this was probably nitric acid or aqua regia, both capable of etching soft glass.

Andreas Sigismund Marggraf made the first definite preparation of hydrofluoric acid in 1764 when he heated fluorite with sulfuric acid in glass, which was greatly corroded by the product. In 1771, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele repeated this reaction. Scheele recognized the product of the reaction as an acid, which he called "fluss-spats-syran" (fluor-spar-acid); in English, it was known as "fluoric acid".

Some sources claim that the first production of hydrofluoric acid was by Heinrich Schwanhard, a German glass cutter, in 1670. A peer-reviewed study of Schwanhard's writings, though, showed no specific mention of fluorite and only discussion of an extremely strong acid. It was hypothesized that this was probably nitric acid or aqua regia, both capable of etching soft glass.

Andreas Sigismund Marggraf made the first definite preparation of hydrofluoric acid in 1764 when he heated fluorite with sulfuric acid in glass, which was greatly corroded by the product. In 1771, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele repeated this reaction. Scheele recognized the product of the reaction as an acid, which he called "fluss-spats-syran" (fluor-spar-acid); in English, it was known as "fluoric acid".

In 1810, French physicist

In 1810, French physicist

French chemist Henri Moissan, formerly one of Frémy's students, continued the search. After trying many different approaches, he built on Frémy and Gore's earlier attempts by combining potassium bifluoride and hydrogen fluoride. The resultant solution conducted electricity. Moissan also constructed especially corrosion-resistant equipment: containers crafted from a mixture of platinum and iridium (more chemically resistant than pure platinum) with fluorite stoppers.

After 74 years of effort by many chemists, on 26 June 1886, Moissan isolated elemental fluorine. Moissan's report to the French Academy of making fluorine showed appreciation for the feat: "One can indeed make various hypotheses on the nature of the liberated gas; the simplest would be that ''we are in the presence of fluorine''."

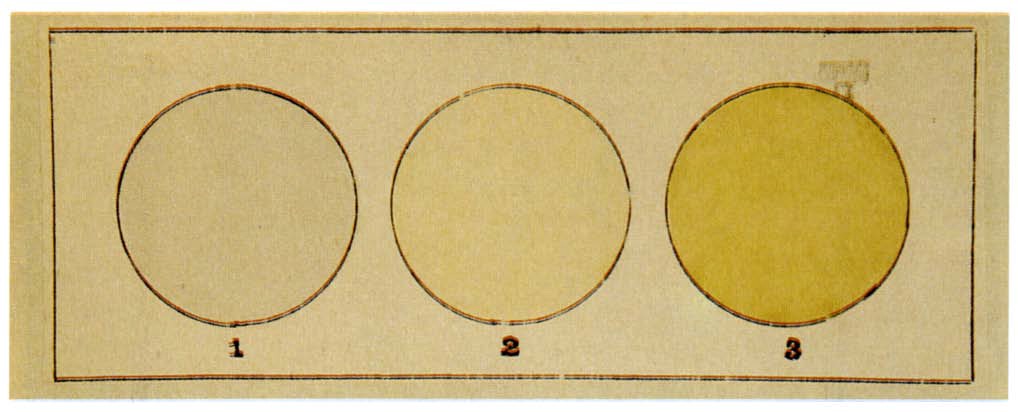

Moissan's 1887 publication documents reaction attempts of fluorine gas with several substances: sulfur (flames), hydrogen (explosion), carbon (no reaction), etc. Later, Moissan devised a less expensive apparatus for making fluorine: copper equipment coated with copper fluoride.

Moissan also constructed special apparatus—5m long platinum tubes with fluorite windows—to determine the slight yellow color of fluorine gas. (The gas appears transparent in small tubes or when allowed to escape. The color observation was not repeated until the 1980s, when his result was confirmed.)

French chemist Henri Moissan, formerly one of Frémy's students, continued the search. After trying many different approaches, he built on Frémy and Gore's earlier attempts by combining potassium bifluoride and hydrogen fluoride. The resultant solution conducted electricity. Moissan also constructed especially corrosion-resistant equipment: containers crafted from a mixture of platinum and iridium (more chemically resistant than pure platinum) with fluorite stoppers.

After 74 years of effort by many chemists, on 26 June 1886, Moissan isolated elemental fluorine. Moissan's report to the French Academy of making fluorine showed appreciation for the feat: "One can indeed make various hypotheses on the nature of the liberated gas; the simplest would be that ''we are in the presence of fluorine''."

Moissan's 1887 publication documents reaction attempts of fluorine gas with several substances: sulfur (flames), hydrogen (explosion), carbon (no reaction), etc. Later, Moissan devised a less expensive apparatus for making fluorine: copper equipment coated with copper fluoride.

Moissan also constructed special apparatus—5m long platinum tubes with fluorite windows—to determine the slight yellow color of fluorine gas. (The gas appears transparent in small tubes or when allowed to escape. The color observation was not repeated until the 1980s, when his result was confirmed.)

In 1906, two months before his death, Moissan received the Nobel Prize in chemistry. The citation:

In 1906, two months before his death, Moissan received the Nobel Prize in chemistry. The citation:

During the 1930s and 1940s, the

During the 1930s and 1940s, the

Research in the isolation of Fluorine

1887 report by Moissan with drawings, on the French Wikisource. {{History of chemistry Fluorine History of chemistry Articles containing video clips

hydrofluoric acid

Hydrofluoric acid is a Solution (chemistry), solution of hydrogen fluoride (HF) in water. Solutions of HF are colourless, acidic and highly Corrosive substance, corrosive. It is used to make most fluorine-containing compounds; examples include th ...

was discovered. By the early 19th century, it was recognized that fluorine was a bound element within compounds, similar to chlorine. Fluorite was determined to be calcium fluoride.

Because of fluorine's tight bonding as well as the toxicity of hydrogen fluoride

Hydrogen fluoride (fluorane) is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . This colorless gas or liquid is the principal industrial source of fluorine, often as an aqueous solution called hydrofluoric acid. It is an important feedstock i ...

, the element resisted many attempts to isolate it. In 1886, French chemist Henri Moissan, later a Nobel Prize winner, succeeded in making elemental fluorine by electrolyzing a mixture of potassium fluoride and hydrogen fluoride. Large-scale production and use of fluorine began during World War 2 as part of the Manhattan Project. Earlier in the century, the main fluorochemicals were commercialized by the DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

company: refrigerant gases ( Freon) and polytetrafluoroethylene plastic ( Teflon).

Ancient use

Early metallurgy

The word "fluorine" derives from the Latin stem of the main source mineral, fluorite, which was first mentioned in 1529 by Georgius Agricola, the "father of mineralogy". He described fluorite as a

The word "fluorine" derives from the Latin stem of the main source mineral, fluorite, which was first mentioned in 1529 by Georgius Agricola, the "father of mineralogy". He described fluorite as a flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport ph ...

—an additive that helps melt ores and slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-prod ...

s during smelting. Fluorite stones were called ''schone flusse'' in the German of the time. Agricola, writing in Latin but describing 16th century industry, invented several hundred new Latin terms. For the ''schone flusse'' stones, he used the Latin noun ''fluores'', "fluxes", because they made metal ores flow when in a fire. After Agricola, the name for the mineral evolved to fluorspar

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

The Mohs scal ...

(still commonly used) and then to fluorite.

Fluorite mineral was also described in the writings of alchemist Basilius Valentinus

Basil Valentine is the Anglicised version of the name Basilius Valentinus, ostensibly a 15th-century alchemist, possibly Canon of the Benedictine Priory of Saint Peter in Erfurt, Germany but more likely a pseudonym used by one or several 16th-ce ...

, supposedly in the late 15th century. However, it is alleged that "Valentinus" was a hoax as his writings were not known until about 1600.

Hydrofluoric acid

Some sources claim that the first production of hydrofluoric acid was by Heinrich Schwanhard, a German glass cutter, in 1670. A peer-reviewed study of Schwanhard's writings, though, showed no specific mention of fluorite and only discussion of an extremely strong acid. It was hypothesized that this was probably nitric acid or aqua regia, both capable of etching soft glass.

Andreas Sigismund Marggraf made the first definite preparation of hydrofluoric acid in 1764 when he heated fluorite with sulfuric acid in glass, which was greatly corroded by the product. In 1771, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele repeated this reaction. Scheele recognized the product of the reaction as an acid, which he called "fluss-spats-syran" (fluor-spar-acid); in English, it was known as "fluoric acid".

Some sources claim that the first production of hydrofluoric acid was by Heinrich Schwanhard, a German glass cutter, in 1670. A peer-reviewed study of Schwanhard's writings, though, showed no specific mention of fluorite and only discussion of an extremely strong acid. It was hypothesized that this was probably nitric acid or aqua regia, both capable of etching soft glass.

Andreas Sigismund Marggraf made the first definite preparation of hydrofluoric acid in 1764 when he heated fluorite with sulfuric acid in glass, which was greatly corroded by the product. In 1771, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele repeated this reaction. Scheele recognized the product of the reaction as an acid, which he called "fluss-spats-syran" (fluor-spar-acid); in English, it was known as "fluoric acid".

Recognition of the element

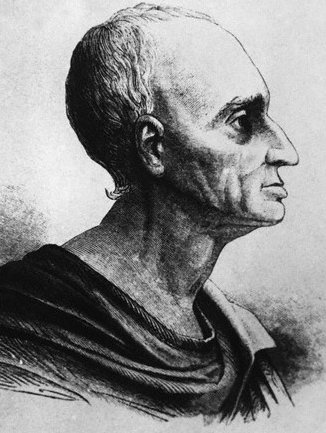

In 1810, French physicist

In 1810, French physicist André-Marie Ampère

André-Marie Ampère (, ; ; 20 January 177510 June 1836) was a French physicist and mathematician who was one of the founders of the science of classical electromagnetism, which he referred to as "electrodynamics". He is also the inventor of nu ...

suggested that hydrofluoric acid was a compound of hydrogen with an unknown element, analogous to chlorine. Fluorite was then shown to be mostly composed of calcium fluoride.

Sir Humphry Davy originally suggested the name ''fluorine'', taking the root from the name of "fluoric acid" and the -ine suffix, similarly to other halogens. This name, with modifications, came to most European languages. (Greek, Russian, and several other languages use the name ''ftor'' or derivatives, which was suggested by Ampère and comes from the Greek φθόριος (''phthorios''), meaning "destructive".) The New Latin name (''fluorum'') gave the element its current symbol, F, although the symbol Fl has been used in early papers. The symbol Fl is now used for the super-heavy element

The transuranium elements (also known as transuranic elements) are the chemical elements with atomic numbers greater than 92, which is the atomic number of uranium. All of these elements are unstable and decay radioactively into other elements. ...

flerovium.

Early isolation attempts

Progress in isolating the element was slowed by the exceptional dangers of generating fluorine: several 19th century experimenters, the "fluorine martyrs", were killed or blinded. Humphry Davy, as well as the notable French chemists Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac andLouis Jacques Thénard

Louis Jacques Thénard (4 May 177721 June 1857) was a French chemist.

Life

He was born in a farm cottage near Nogent-sur-Seine in the Champagne district

the son of a farm worker. In the post-Revolution French educational system , most boys rec ...

, experienced severe pains from inhaling hydrogen fluoride gas; Davy's eyes were damaged. Irish chemists Thomas and George Knox developed fluorite apparatus for working with hydrogen fluoride, but nonetheless were severely poisoned. Thomas nearly died and George was disabled for three years. French chemist Henri Moissan was poisoned several times, which shortened his life. Belgian chemist Paulin Louyet and French chemist tried to follow the Knox work, but they died from HF poisoning even though they were aware of the dangers.

Initial attempts to isolate the element were also hindered by material difficulties: the extreme corrosiveness and reactivity of hydrogen fluoride (and of fluorine gas) as well as problems getting a suitable conducting liquid for electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of elements from n ...

. Davy tried to electrolyze HF but had to stop because the electrodes were damaged. He then shifted to (unsuccessful) chemical reactions.

Edmond Frémy thought that passing electric current through pure hydrofluoric acid (dry HF) might work. Previously, hydrogen fluoride was only available in a water solution. Frémy therefore devised a method for producing dry hydrogen fluoride by acidifying potassium bifluoride (KHF2). Unfortunately, pure hydrogen fluoride did not pass an electric current. Frémy also tried electrolyzing molten calcium fluoride and probably produced some fluorine (since he made calcium metal at the other electrode), but he was unable to collect the gas.

English chemist George Gore also tried electrolyzing dry HF and may have made small quantities of fluorine gas in 1860. He reported an explosion after running his cell (hydrogen and fluorine recombine dramatically), but he recognized that an oxygen leak could have also caused the reaction.

Moissan

French chemist Henri Moissan, formerly one of Frémy's students, continued the search. After trying many different approaches, he built on Frémy and Gore's earlier attempts by combining potassium bifluoride and hydrogen fluoride. The resultant solution conducted electricity. Moissan also constructed especially corrosion-resistant equipment: containers crafted from a mixture of platinum and iridium (more chemically resistant than pure platinum) with fluorite stoppers.

After 74 years of effort by many chemists, on 26 June 1886, Moissan isolated elemental fluorine. Moissan's report to the French Academy of making fluorine showed appreciation for the feat: "One can indeed make various hypotheses on the nature of the liberated gas; the simplest would be that ''we are in the presence of fluorine''."

Moissan's 1887 publication documents reaction attempts of fluorine gas with several substances: sulfur (flames), hydrogen (explosion), carbon (no reaction), etc. Later, Moissan devised a less expensive apparatus for making fluorine: copper equipment coated with copper fluoride.

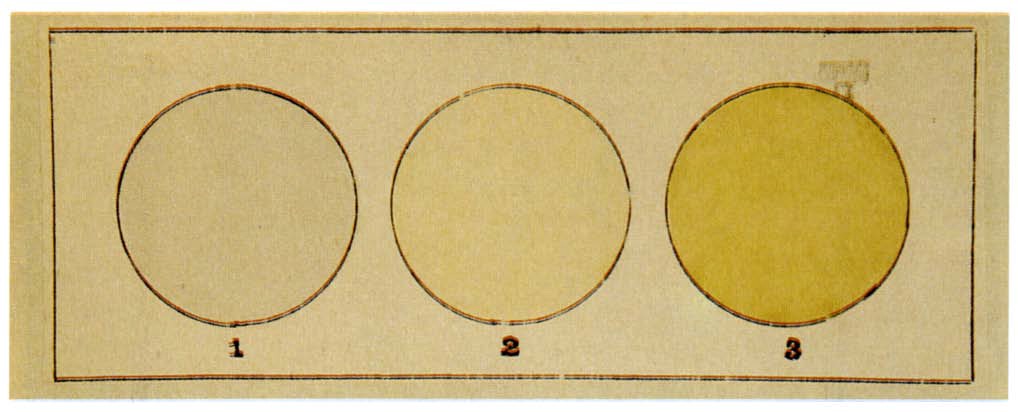

Moissan also constructed special apparatus—5m long platinum tubes with fluorite windows—to determine the slight yellow color of fluorine gas. (The gas appears transparent in small tubes or when allowed to escape. The color observation was not repeated until the 1980s, when his result was confirmed.)

French chemist Henri Moissan, formerly one of Frémy's students, continued the search. After trying many different approaches, he built on Frémy and Gore's earlier attempts by combining potassium bifluoride and hydrogen fluoride. The resultant solution conducted electricity. Moissan also constructed especially corrosion-resistant equipment: containers crafted from a mixture of platinum and iridium (more chemically resistant than pure platinum) with fluorite stoppers.

After 74 years of effort by many chemists, on 26 June 1886, Moissan isolated elemental fluorine. Moissan's report to the French Academy of making fluorine showed appreciation for the feat: "One can indeed make various hypotheses on the nature of the liberated gas; the simplest would be that ''we are in the presence of fluorine''."

Moissan's 1887 publication documents reaction attempts of fluorine gas with several substances: sulfur (flames), hydrogen (explosion), carbon (no reaction), etc. Later, Moissan devised a less expensive apparatus for making fluorine: copper equipment coated with copper fluoride.

Moissan also constructed special apparatus—5m long platinum tubes with fluorite windows—to determine the slight yellow color of fluorine gas. (The gas appears transparent in small tubes or when allowed to escape. The color observation was not repeated until the 1980s, when his result was confirmed.)

In 1906, two months before his death, Moissan received the Nobel Prize in chemistry. The citation:

In 1906, two months before his death, Moissan received the Nobel Prize in chemistry. The citation:

...in recognition of the great services rendered by him in his investigation and isolation of the element fluorine...The whole world has admired the great experimental skill with which you have studied that savage beast among the elements.

Development

During the 1930s and 1940s, the

During the 1930s and 1940s, the DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

company commercialized organofluorine compounds at large scales. Following trials of chlorofluorocarbons as refrigerants by researchers at General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

, DuPont developed large-scale production of Freon-12

Dichlorodifluoromethane (R-12) is a colorless gas usually sold under the brand name Freon-12, and a chlorofluorocarbon halomethane (CFC) used as a refrigerant and aerosol spray propellant. Complying with the Montreal Protocol, its manufacture w ...

. The work was carried out by DuPont scientist Dr. Thomas Midgley Jr. DuPont and GM formed a joint venture in 1930 to market the new product; in 1949 DuPont took over the business. Freon proved to be a marketplace hit, rapidly replacing earlier, more toxic, refrigerants and growing the overall market for kitchen refrigerators.

In 1938, polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) was discovered by accident by a recently hired DuPont PhD, Roy J. Plunkett

Roy J. Plunkett (June 26, 1910 – May 12, 1994) was an American chemist. He discovered polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), better known as Teflon, in 1938.

Personal life and education

Plunkett was born in New Carlisle, Ohio and attended Newton Hig ...

. While working with a cylinder of tetrafluoroethylene, he was unable to release the gas, although the weight had not changed. Scraping down the container, he found white flakes of a polymer new to the world. Tests showed the substance was resistant to corrosion from most substances and had better high temperature stability than any other plastic. By early 1941, a crash program was making commercial quantities.

Large-scale productions of elemental fluorine began during World War II. Germany used high-temperature electrolysis to produce tons of chlorine trifluoride, a compound planned to be used as an incendiary. The Manhattan project in the United States produced even more fluorine for use in uranium separation. Gaseous uranium hexafluoride

Uranium hexafluoride (), (sometimes called "hex") is an inorganic compound with the formula UF6. Uranium hexafluoride is a volatile white solid that reacts with water, releasing corrosive hydrofluoric acid. The compound reacts mildly with alumin ...

was used to separate uranium-235, an important nuclear explosive, from the heavier uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However, it ...

in diffusion plants. Because uranium hexafluoride releases small quantities of corrosive fluorine, the separation plants were built with special materials. All pipes were coated with nickel; joints and flexible parts were fabricated from Teflon.

In 1958, a DuPont research manager in the Teflon business, Bill Gore, left the company because of its unwillingness to develop Teflon as wire-coating insulation. Gore's son Robert found a method for solving the wire-coating problem and the company W. L. Gore and Associates

W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc. is an American multinational manufacturing company specializing in products derived from fluoropolymers. It is a privately held corporation headquartered in Newark, Delaware. It is best known as the developer of wat ...

was born. In 1969, Robert Gore developed an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is a synthetic fluoropolymer of tetrafluoroethylene that has numerous applications. It is one of the best-known and widely applied PFAS. The commonly known brand name of PTFE-based composition is Teflon by Chemour ...

(ePTFE) membrane which led to the large Gore-Tex business in breathable rainwear. The company developed many other uses of PTFE.

In the 1970s and 1980s, concerns developed over the role chlorofluorocarbons play in damaging the ozone layer

The ozone layer or ozone shield is a region of Earth's stratosphere that absorbs most of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation. It contains a high concentration of ozone (O3) in relation to other parts of the atmosphere, although still small in rela ...

. By 1996, almost all nations had banned chlorofluorocarbon refrigerants and commercial production ceased. Fluorine continued to play a role in refrigeration though: hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are man-made organic compounds that contain fluorine and hydrogen atoms, and are the most common type of organofluorine compounds. Most are gases at room temperature and pressure. They are frequently used in air conditi ...

(HFCs) were developed as replacement refrigerants.

See also

* History of aluminiumNotes

Citations

Indexed references

* *External links

*Research in the isolation of Fluorine

1887 report by Moissan with drawings, on the French Wikisource. {{History of chemistry Fluorine History of chemistry Articles containing video clips