History of electrical engineering on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This article details the history of

This article details the history of

Hauksbee continued to experiment with electricity, making numerous observations and developing machines to generate and demonstrate various electrical phenomena. In 1709 he published ''Physico-Mechanical Experiments on Various Subjects'' which summarized much of his scientific work.

Stephen Gray discovered the importance of insulators and conductors. C. F. du Fay seeing his work, developed a "two-fluid" theory of electricity.

In the 18th century,

Hauksbee continued to experiment with electricity, making numerous observations and developing machines to generate and demonstrate various electrical phenomena. In 1709 he published ''Physico-Mechanical Experiments on Various Subjects'' which summarized much of his scientific work.

Stephen Gray discovered the importance of insulators and conductors. C. F. du Fay seeing his work, developed a "two-fluid" theory of electricity.

In the 18th century,

Electrical engineering became a profession in the late 19th century. Practitioners had created a global

Electrical engineering became a profession in the late 19th century. Practitioners had created a global  Development of the scientific basis for electrical engineering, with the tools of modern research techniques, intensified during the 19th century. Notable developments early in this century include the work of Georg Ohm, who in 1827 quantified the relationship between the

Development of the scientific basis for electrical engineering, with the tools of modern research techniques, intensified during the 19th century. Notable developments early in this century include the work of Georg Ohm, who in 1827 quantified the relationship between the  "By the mid-1890s the four "Maxwell equations" were recognized as the foundation of one of the strongest and most successful theories in all of physics; they had taken their place as companions, even rivals, to Newton's laws of mechanics. The equations were by then also being put to practical use, most dramatically in the emerging new technology of radio communications, but also in the telegraph, telephone, and electric power industries." By the end of the 19th century, figures in the progress of electrical engineering were beginning to emerge.

"By the mid-1890s the four "Maxwell equations" were recognized as the foundation of one of the strongest and most successful theories in all of physics; they had taken their place as companions, even rivals, to Newton's laws of mechanics. The equations were by then also being put to practical use, most dramatically in the emerging new technology of radio communications, but also in the telegraph, telephone, and electric power industries." By the end of the 19th century, figures in the progress of electrical engineering were beginning to emerge.

During the development of radio, many scientists and inventors contributed to

During the development of radio, many scientists and inventors contributed to

Antentop

', Vol. 2, No.3, pp. 87–96. when he patented the radio

The first working transistor was a point-contact transistor invented by John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brattain while working under William Shockley at the Bell Telephone Laboratories (BTL) in 1947. They then invented the bipolar junction transistor in 1948. While early junction transistors were relatively bulky devices that were difficult to manufacture on a mass-production basis, they opened the door for more compact devices.

The first integrated circuits were the hybrid integrated circuit invented by Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments in 1958 and the monolithic integrated circuit chip invented by Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959.

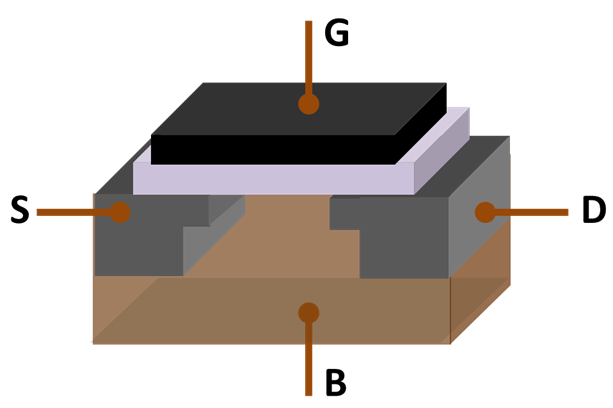

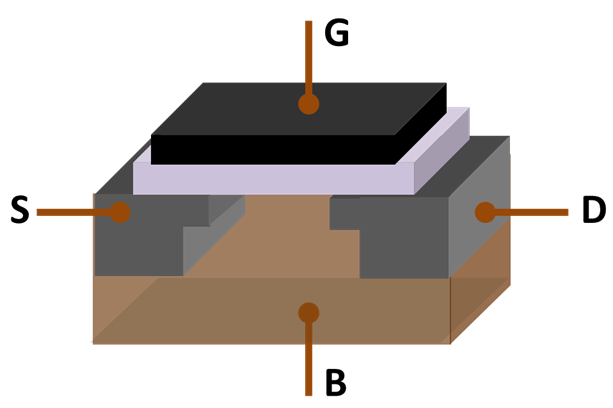

The MOSFET (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor, or MOS transistor) was invented by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at BTL in 1959. It was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturised and mass-produced for a wide range of uses. It revolutionized the electronics industry, becoming the most widely used electronic device in the world.

The first working transistor was a point-contact transistor invented by John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brattain while working under William Shockley at the Bell Telephone Laboratories (BTL) in 1947. They then invented the bipolar junction transistor in 1948. While early junction transistors were relatively bulky devices that were difficult to manufacture on a mass-production basis, they opened the door for more compact devices.

The first integrated circuits were the hybrid integrated circuit invented by Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments in 1958 and the monolithic integrated circuit chip invented by Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959.

The MOSFET (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor, or MOS transistor) was invented by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at BTL in 1959. It was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturised and mass-produced for a wide range of uses. It revolutionized the electronics industry, becoming the most widely used electronic device in the world.

File:Bardeen Shockley Brattain 1948.JPG, John Bardeen, William Shockley, Walter Brattain transistor (1947)

File:Atalla1963.png, Mohamed M. Atalla silicon surface passivation, passivation (1957) and MOSFET transistor (1959)

File:Robert Noyce with Motherboard 1959.png, Robert Noyce monolithic integrated circuit chip (1959)

File:Dawon Kahng.jpg, Dawon Kahng MOSFET transistor (1959)

File:Gordon Moore.jpg, Gordon Moore

Moore's law (1965) File:Federico Faggin (cropped).jpg, Federico Faggin silicon-gate MOSFET (1968) and microprocessor (1971) File:Marcian Ted Hoff.jpg, Marcian Hoff microprocessor (1971) File:Shima and Mazor.jpg, Masatoshi Shima, Stanley Mazor microprocessor (1971)

The MOSFET made it possible to build very large-scale integration, high-density integrated circuit chips. The earliest experimental MOS IC chip to be fabricated was built by Fred Heiman and Steven Hofstein at RCA Laboratories in 1962. MOS technology enabled Moore's law, the transistor count, doubling of transistors on an IC chip every two years, predicted by Gordon Moore in 1965. Silicon-gate MOS technology was developed by Federico Faggin at Fairchild in 1968. Since then, the MOSFET has been the basic building block of modern electronics. The mass-production of silicon MOSFETs and MOS integrated circuit chips, along with continuous MOSFET scaling miniaturization at an exponential pace (as predicted by Moore's law), has since led to revolutionary changes in technology, economy, culture and thinking.

The Apollo program which culminated in Moon landing, landing astronauts on the Moon with Apollo 11 in 1969 was enabled by NASA's adoption of advances in

The Making of the First Microprocessor

''IEEE Solid-State Circuits Magazine'', Winter 2009, IEEE Xplore This ignited the development of the personal computer. The 4004, a 4-bit computing, 4-bit processor, was followed in 1973 by the Intel 8080, an 8-bit computing, 8-bit processor, which made possible the building of the first personal computer, the Altair 8800.

Nobel Prize Awards Related to Electrical Engineering

(relevant patents included)

Shock and Awe: The Story of Electricity – Jim Al-Khalili BBC HorizonElectrickery

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Simon Schaffer, Patricia Fara & Iwan Morus (''In Our Time'', November 4, 2004) {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Electrical Engineering History of electrical engineering, de:Elektrotechnik#Geschichte, Entwicklungen und Personen der Elektrotechnik

This article details the history of

This article details the history of electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

.

Ancient developments

Long before any knowledge of electricity existed, people were aware of shocks fromelectric fish

An electric fish is any fish that can generate electric fields. Most electric fish are also electroreceptive, meaning that they can sense electric fields. The only exception is the stargazer family. Electric fish, although a small minority, inc ...

. Ancient Egyptian texts dating from 2750 BCE referred to these fish as the "Thunderer of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

", and described them as the "protectors" of all other fish. Electric fish were again reported millennia later by ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

, Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

and Arabic naturalists and physicians

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

. Several ancient writers, such as Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

and Scribonius Largus, attested to the numbing effect of electric shock

Electrical injury is a physiological reaction caused by electric current passing through the body. The injury depends on the density of the current, tissue resistance and duration of contact. Very small currents may be imperceptible or produce a ...

s delivered by electric catfish

Electric catfish or Malapteruridae is a family of catfishes (order Siluriformes). This family includes two genera, '' Malapterurus'' and '' Paradoxoglanis'', with 21 species. Several species of this family have the ability to generate electricit ...

and electric ray

The electric rays are a group of rays, flattened cartilaginous fish with enlarged pectoral fins, composing the order Torpediniformes . They are known for being capable of producing an electric discharge, ranging from 8 to 220 volts, depending ...

s, and knew that such shocks could travel along conducting objects.

Patients with ailments such as gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

or headache were directed to touch electric fish in the hope that the powerful jolt might cure them.

Possibly the earliest and nearest approach to the discovery of the identity of lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

, and electricity from any other source, is to be attributed to the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, who before the 15th century had the Arabic word for lightning ''ra‘ad'' () applied to the electric ray

The electric rays are a group of rays, flattened cartilaginous fish with enlarged pectoral fins, composing the order Torpediniformes . They are known for being capable of producing an electric discharge, ranging from 8 to 220 volts, depending ...

.''The Encyclopedia Americana

''Encyclopedia Americana'' is a general encyclopedia written in American English. It was the first major multivolume encyclopedia that was published in the United States. With ''Collier's Encyclopedia'' and ''Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclo ...

; a library of universal knowledge'' (1918), New York City: Encyclopedia Americana Corp

Ancient cultures around the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

knew that certain objects, such as rods of amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In M ...

, could be rubbed with cat's fur to attract light objects like feathers. Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

, an ancient Greek philosopher, writing at around 600 BCE, described a form of static electricity

Static electricity is an imbalance of electric charges within or on the surface of a material or between materials. The charge remains until it is able to move away by means of an electric current or electrical discharge. Static electricity is na ...

, noting that rubbing fur on various substances, such as amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In M ...

, would cause a particular attraction between the two. He noted that the amber buttons could attract light objects such as hair and that if they rubbed the amber for long enough they could even get a spark

Spark commonly refers to:

* Spark (fire), a small glowing particle or ember

* Electric spark, a form of electrical discharge

Spark may also refer to:

Places

* Spark Point, a rocky point in the South Shetland Islands

People

* Spark (surname)

* ...

to jump.

At around 450 BCE Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

, a later Greek philosopher, developed an atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. Atomic theory traces its origins to an ancient philosophical tradition known as atomism. According to this idea, if one were to take a lump of matter ...

that was similar to modern atomic theory. His mentor, Leucippus, is credited with this same theory. The hypothesis of Leucippus and Democritus held everything to be composed of atoms

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas ...

. But these ''atoms'', called "atomos", were indivisible, and indestructible. He presciently stated that between atoms lies empty space, and that atoms are constantly in motion. He was incorrect only in stating that atoms come in different sizes and shapes, and that each object had its own shaped and sized atom.Russell, Bertrand (1972). ''A History of Western Philosophy'', Simon & Schuster. pp.64–65.Barnes, Jonathan.(1987). Early Greek Philosophy, Penguin.

An object found in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

in 1938, dated to about 250 BCE and called the Baghdad Battery

The Baghdad Battery is the name given to a set of three artifacts which were found together: a ceramic pot, a tube of copper, and a rod of iron. It was discovered in present-day Khujut Rabu, Iraq in 1936, close to the metropolis of Ctesiphon, the ...

, resembles a galvanic cell

A galvanic cell or voltaic cell, named after the scientists Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta, respectively, is an electrochemical cell in which an electric current is generated from spontaneous Oxidation-Reduction reactions. A common apparatus ...

and is claimed by some to have been used for electroplating

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct electric current. The part to be ...

in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, although there is no evidence for this.

17th-century developments

Electricity would remain little more than an intellectual curiosity for millennia. In 1600, the English scientist, William Gilbert extended the study of Cardano on electricity and magnetism, distinguishing thelodestone

Lodestones are naturally magnetized pieces of the mineral magnetite. They are naturally occurring magnets, which can attract iron. The property of magnetism was first discovered in antiquity through lodestones. Pieces of lodestone, suspen ...

effect from static electricity produced by rubbing amber. He coined the New Latin

New Latin (also called Neo-Latin or Modern Latin) is the revival of Literary Latin used in original, scholarly, and scientific works since about 1500. Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy ...

word ''electricus'' ("of amber" or "like amber", from ''ήλεκτρον'' 'elektron'' the Greek word for "amber") to refer to the property of attracting small objects after being rubbed. This association gave rise to the English words "electric" and "electricity", which made their first appearance in print in Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne (; 19 October 160519 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a deep curi ...

's ''Pseudodoxia Epidemica

''Pseudodoxia Epidemica or Enquiries into very many received tenents and commonly presumed truths'', also known simply as ''Pseudodoxia Epidemica'' or ''Vulgar Errors'', is a work by Thomas Browne challenging and refuting the "vulgar" or common ...

'' of 1646.

Further work was conducted by Otto von Guericke

Otto von Guericke ( , , ; spelled Gericke until 1666; November 20, 1602 – May 11, 1686 ; November 30, 1602 – May 21, 1686 ) was a German scientist, inventor, and politician. His pioneering scientific work, the development of experimental me ...

who showed electrostatic repulsion. Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders ...

also published work.

18th-century developments

Though electrical phenomena had been known for centuries, in the 18th century, the systematic study of electricity became known as "the youngest of the sciences", and the public became electrified by the newest discoveries in the field. By 1705,Francis Hauksbee

Francis Hauksbee the Elder FRS (1660–1713), also known as Francis Hawksbee, was an 18th-century English scientist best known for his work on electricity and electrostatic repulsion.

Biography

Francis Hauksbee was the son of draper and common c ...

had discovered that if he placed a small amount of mercury in the glass of his modified version of Otto von Guericke

Otto von Guericke ( , , ; spelled Gericke until 1666; November 20, 1602 – May 11, 1686 ; November 30, 1602 – May 21, 1686 ) was a German scientist, inventor, and politician. His pioneering scientific work, the development of experimental me ...

's generator, evacuated the air from it to create a mild vacuum and rubbed the ball to build up a charge, a glow was visible if he placed his hand on the outside of the ball. This glow was bright enough to read by. It seemed to be similar to St. Elmo's Fire

St. Elmo's fire — also called Witchfire or Witch's Fire — is a weather phenomenon in which luminous plasma is created by a corona discharge from a rod-like object such as a mast, spire, chimney, or animal hornHeidorn, K., Weather Element ...

. This effect later became the basis of the gas-discharge lamp

Gas-discharge lamps are a family of artificial light sources that generate light by sending an electric discharge through an ionized gas, a plasma.

Typically, such lamps use a

noble gas (argon, neon, krypton, and xenon) or a mixture of t ...

, which led to neon lighting and mercury vapor lamps. In 1706 he produced an 'Influence machine' to generate this effect. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

the same year.

Hauksbee continued to experiment with electricity, making numerous observations and developing machines to generate and demonstrate various electrical phenomena. In 1709 he published ''Physico-Mechanical Experiments on Various Subjects'' which summarized much of his scientific work.

Stephen Gray discovered the importance of insulators and conductors. C. F. du Fay seeing his work, developed a "two-fluid" theory of electricity.

In the 18th century,

Hauksbee continued to experiment with electricity, making numerous observations and developing machines to generate and demonstrate various electrical phenomena. In 1709 he published ''Physico-Mechanical Experiments on Various Subjects'' which summarized much of his scientific work.

Stephen Gray discovered the importance of insulators and conductors. C. F. du Fay seeing his work, developed a "two-fluid" theory of electricity.

In the 18th century, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

conducted extensive research in electricity, selling his possessions to fund his work. In June 1752 he is reputed to have attached a metal key to the bottom of a dampened kite string and flown the kite in a storm-threatened sky. A succession of sparks jumping from the key to the back of his hand showed that lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

was indeed electrical in nature. He also explained the apparently paradoxical behavior of the Leyden jar

A Leyden jar (or Leiden jar, or archaically, sometimes Kleistian jar) is an electrical component that stores a high-voltage electric charge (from an external source) between electrical conductors on the inside and outside of a glass jar. It ty ...

as a device for storing large amounts of electrical charge, by coming up with the single fluid, two states theory of electricity.

In 1791, Italian Luigi Galvani

Luigi Galvani (, also ; ; la, Aloysius Galvanus; 9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, physicist, biologist and philosopher, who studied animal electricity. In 1780, he discovered that the muscles of dead frogs' legs ...

published his discovery of bioelectricity

In developmental biology, bioelectricity refers to the regulation of cell, tissue, and organ-level patterning and behavior as the result of endogenous electrically mediated signaling. Cells and tissues of all types use ion fluxes to communicate e ...

, demonstrating that electricity was the medium by which nerve cell

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. No ...

s passed signals to the muscles.

Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (, ; 18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827) was an Italian physicist, chemist and lay Catholic who was a pioneer of electricity and power who is credited as the inventor of the electric battery and th ...

's battery, or voltaic pile

upright=1.2, Schematic diagram of a copper–zinc voltaic pile. The copper and zinc discs were separated by cardboard or felt spacers soaked in salt water (the electrolyte). Volta's original piles contained an additional zinc disk at the bottom, ...

, of 1800, made from alternating layers of zinc and copper, provided scientists with a more reliable source of electrical energy than the electrostatic machines previously used.

19th-century developments

Electrical engineering became a profession in the late 19th century. Practitioners had created a global

Electrical engineering became a profession in the late 19th century. Practitioners had created a global electric telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

network and the first electrical engineering institutions to support the new discipline were founded in the UK and US. Although it is impossible to precisely pinpoint a first electrical engineer, Francis Ronalds

Sir Francis Ronalds FRS (21 February 17888 August 1873) was an English scientist and inventor, and arguably the first electrical engineer. He was knighted for creating the first working electric telegraph over a substantial distance. In 1816 ...

stands ahead of the field, who created a working electric telegraph system in 1816 and documented his vision of how the world could be transformed by electricity. Over 50 years later, he joined the new Society of Telegraph Engineers (soon to be renamed the Institution of Electrical Engineers

The Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) was a British professional organisation of electronics, electrical, manufacturing, and Information Technology professionals, especially electrical engineers. It began in 1871 as the Society of T ...

) where he was regarded by other members as the first of their cohort. The donation of his extensive electrical library was a considerable boon for the fledgling Society.

Development of the scientific basis for electrical engineering, with the tools of modern research techniques, intensified during the 19th century. Notable developments early in this century include the work of Georg Ohm, who in 1827 quantified the relationship between the

Development of the scientific basis for electrical engineering, with the tools of modern research techniques, intensified during the 19th century. Notable developments early in this century include the work of Georg Ohm, who in 1827 quantified the relationship between the electric current

An electric current is a stream of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is measured as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface or into a control volume. The movi ...

and potential difference

Voltage, also known as electric pressure, electric tension, or (electric) potential difference, is the difference in electric potential between two points. In a static electric field, it corresponds to the work needed per unit of charge to m ...

in a conductor, Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

, the discoverer of electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1831, and James Cle ...

in 1831. In the 1830s, Georg Ohm also constructed an early electrostatic machine. The homopolar generator

A homopolar generator is a DC electrical generator comprising an electrically conductive disc or cylinder rotating in a plane perpendicular to a uniform static magnetic field. A potential difference is created between the center of the disc and t ...

was developed first by Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

during his memorable experiments in 1831. It was the beginning of modern dynamos – that is, electrical generators which operate using a magnetic field. The invention of the industrial generator in 1866 by Werner von Siemens

Ernst Werner Siemens (von Siemens from 1888; ; ; 13 December 1816 – 6 December 1892) was a German electrical engineer, inventor and industrialist. Siemens's name has been adopted as the SI unit of electrical conductance, the siemens. He foun ...

– which did not need external magnetic power – made a large series of other inventions in the wake possible.

In 1873, James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and ligh ...

published a unified treatment of electricity and magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

in A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism

''A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism'' is a two-volume treatise on electromagnetism written by James Clerk Maxwell in 1873. Maxwell was revising the ''Treatise'' for a second edition when he died in 1879. The revision was completed by Wil ...

which stimulated several theorists to think in terms of fields described by Maxwell's equations

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, and electric circuits ...

. In 1878, the British inventor James Wimshurst

James Wimshurst (13 April 1832 – 3 January 1903) was an English inventor, engineer and shipwright. Though Wimshurst did not patent his machines and the various improvements that he made to them, his refinements to the electrostatic generator led ...

developed an apparatus that had two glass disks mounted on two shafts. It was not until 1883 that the Wimshurst machine

The Wimshurst influence machine is an electrostatic generator, a machine for generating high voltages developed between 1880 and 1883 by British inventor James Wimshurst (1832–1903).

It has a distinctive appearance with two large contra-ro ...

was more fully reported to the scientific community.

During the latter part of the 1800s, the study of electricity was largely considered to be a subfield of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

. It was not until the late 19th century that universities started to offer degrees in electrical engineering.

In 1882, Darmstadt University of Technology founded the first chair and the first faculty of electrical engineering worldwide. In the same year, under Professor Charles Cross, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

began offering the first option of Electrical Engineering within a physics department. In 1883, Darmstadt University of Technology and Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

introduced the world's first courses of study in electrical engineering and in 1885 the University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

founded the first chair of electrical engineering in the United Kingdom. The University of Missouri

The University of Missouri (Mizzou, MU, or Missouri) is a public land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus University of Missouri System. MU was founded in ...

subsequently established the first department of electrical engineering in the United States in 1886.

During this period commercial use of electricity increased dramatically. Starting in the late 1870s cities started installing large scale electric street lighting systems based on arc lamp

An arc lamp or arc light is a lamp that produces light by an electric arc (also called a voltaic arc).

The carbon arc light, which consists of an arc between carbon electrodes in air, invented by Humphry Davy in the first decade of the 1800s, ...

s. After the development of a practical incandescent lamp

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a wire filament heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb with a vacuum or inert gas to protect the filament from oxida ...

for indoor lighting, Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventi ...

switched on the world's first public electric supply utility in 1882, using what was considered a relatively safe 110 volts direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or ev ...

system to supply customers. Engineering advances in the 1880s, including the invention of the transformer

A transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces a varying magnetic flux in the transformer' ...

, led to electric utilities starting to adopting alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current which periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time in contrast to direct current (DC) which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in whic ...

, up until then used primarily in arc lighting systems, as a distribution standard for outdoor and indoor lighting (eventually replacing direct current for such purposes). In the US there was a rivalry, primarily between a Westinghouse AC and the Edison DC system known as the "war of the currents

The war of the currents was a series of events surrounding the introduction of competing electric power transmission systems in the late 1880s and early 1890s. It grew out of two lighting systems developed in the late 1870s and early 1880s; arc ...

".

"By the mid-1890s the four "Maxwell equations" were recognized as the foundation of one of the strongest and most successful theories in all of physics; they had taken their place as companions, even rivals, to Newton's laws of mechanics. The equations were by then also being put to practical use, most dramatically in the emerging new technology of radio communications, but also in the telegraph, telephone, and electric power industries." By the end of the 19th century, figures in the progress of electrical engineering were beginning to emerge.

"By the mid-1890s the four "Maxwell equations" were recognized as the foundation of one of the strongest and most successful theories in all of physics; they had taken their place as companions, even rivals, to Newton's laws of mechanics. The equations were by then also being put to practical use, most dramatically in the emerging new technology of radio communications, but also in the telegraph, telephone, and electric power industries." By the end of the 19th century, figures in the progress of electrical engineering were beginning to emerge.

Charles Proteus Steinmetz

Charles Proteus Steinmetz (born Karl August Rudolph Steinmetz, April 9, 1865 – October 26, 1923) was a German-born American mathematician and electrical engineer and professor at Union College. He fostered the development of alternati ...

helped foster the development of alternating current that made possible the expansion of the electric power industry in the United States, formulating mathematical theories for engineers.

Emergence of radio and electronics

During the development of radio, many scientists and inventors contributed to

During the development of radio, many scientists and inventors contributed to radio technology

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmi ...

and electronics. In his classic UHF

Ultra high frequency (UHF) is the ITU designation for radio frequencies in the range between 300 megahertz (MHz) and 3 gigahertz (GHz), also known as the decimetre band as the wavelengths range from one meter to one tenth of a meter (on ...

experiments of 1888, Heinrich Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz ( ; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism. The uni ...

demonstrated the existence of electromagnetic waves (radio waves

Radio waves are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies of 300 gigahertz ( GHz) and below. At 300 GHz, the corresponding wavelength is 1 mm (s ...

) leading many inventors and scientists to try to adapt them to commercial applications, such as Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi (; 25 April 187420 July 1937) was an Italian inventor and electrical engineer, known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based wireless telegraph system. This led to Marconi ...

(1895) and Alexander Popov (1896).

Millimetre wave

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the electromagnetic spectrum, measured by the metre and its derived scales. The microwave is between 1 meter to 1 millimeter.

The millimetre (American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, ...

communication was first investigated by Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose

(;, ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a biologist, physicist, botanist and an early writer of science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contribution ...

during 18941896, when he reached an extremely high frequency

Extremely high frequency (EHF) is the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) designation for the band of radio frequencies in the electromagnetic spectrum from 30 to 300 gigahertz (GHz). It lies between the super high frequency band and t ...

of up to 60GHz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose expression in terms of SI base units is s−1, meaning that one he ...

in his experiments. He also introduced the use of semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical conductivity value falling between that of a conductor, such as copper, and an insulator, such as glass. Its resistivity falls as its temperature rises; metals behave in the opposite way ...

junctions to detect radio waves, reprinted in Igor Grigorov, Ed., Antentop

', Vol. 2, No.3, pp. 87–96. when he patented the radio

crystal detector

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component used in some early 20th century radio receivers that consists of a piece of crystalline mineral which rectifies the alternating current radio signal. It was employed as a detector (dem ...

in 1901.

20th-century developments

John Fleming invented the first radio tube, thediode

A diode is a two-terminal electronic component that conducts current primarily in one direction (asymmetric conductance); it has low (ideally zero) resistance in one direction, and high (ideally infinite) resistance in the other.

A diod ...

, in 1904.

Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-born inventor, who did a majority of his work in the United States and also claimed U.S. citizenship through his American-born father. During his life he received hundre ...

recognized that a continuous wave needed to be generated to make speech transmission possible, and by the end of 1906 he sent the first radio broadcast of voice. Also in 1906, Robert von Lieben

Robert von Lieben (September 5, 1878, in Vienna – February 20, 1913, in Vienna) was an Austrian entrepreneur, and self-taught physicist and inventor. Lieben and his associates Eugen Reisz and Siegmund Strauss invented and produced a ga ...

and Lee De Forest

Lee de Forest (August 26, 1873 – June 30, 1961) was an American inventor and a fundamentally important early pioneer in electronics. He invented the first electronic device for controlling current flow; the three-element " Audion" triode v ...

independently developed the amplifier tube, called the triode

A triode is an electronic amplifying vacuum tube (or ''valve'' in British English) consisting of three electrodes inside an evacuated glass envelope: a heated filament or cathode, a grid, and a plate (anode). Developed from Lee De Forest's ...

. Edwin Howard Armstrong

Edwin Howard Armstrong (December 18, 1890 – February 1, 1954) was an American electrical engineer and inventor, who developed FM (frequency modulation) radio and the superheterodyne receiver system. He held 42 patents and received numerous awa ...

enabling technology for electronic television, in 1931.

In the early 1920s, there was a growing interest in the development of domestic applications for electricity. Public interest led to exhibitions such featuring "homes of the future" and in the UK, the Electrical Association for Women was established with Caroline Haslett

Dame Caroline Harriet Haslett DBE, JP (17 August 1895 – 4 January 1957) was an English electrical engineer, electricity industry administrator and champion of women's rights.

She was the first secretary of the Women's Engineering Society a ...

as its director in 1924 to encourage women to become involved in electrical engineering.

World War II years

The second world war saw tremendous advances in the field of electronics; especially inradar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

and with the invention of the magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field while ...

by Randall Randall may refer to the following:

Places

United States

*Randall, California, former name of White Hall, California, an unincorporated community

* Randall, Indiana, a former town

*Randall, Iowa, a city

*Randall, Kansas, a city

*Randall, Minnesot ...

and Harry Boot, Boot at the University of Birmingham in 1940. Radio location, radio communication and radio guidance of aircraft were all developed at this time. An early electronic computing device, Colossus computer, Colossus was built by Tommy Flowers of the General Post Office, GPO to decipher the coded messages of the German Lorenz SZ 40/42, Lorenz cipher machine. Also developed at this time were advanced clandestine radio transmitters and receivers for use by secret agents.

An American invention at the time was a device to scramble the telephone calls between Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt. This was called the SIGSALY, Green Hornet system and worked by inserting noise into the signal. The noise was then extracted at the receiving end. This system was never broken by the Germans.

A great amount of work was undertaken in the United States as part of the War Training Program in the areas of radio direction finding, pulsed linear networks, frequency modulation, vacuum tube circuits, transmission line theory and fundamentals of electromagnetic engineering. These studies were published shortly after the war in what became known as the 'Radio Communication Series' published by McGraw-Hill in 1946.

In 1941 Konrad Zuse presented the Z3 (computer), Z3, the world's first fully functional and programmable computer.

Post-war years

Prior to the Second world war, the subject was commonly known as 'radio engineering' and was primarily restricted to aspects of communications and radar, commercial radio and early television. At this time, the study of radio engineering at universities could only be undertaken as part of a physics degree. Later, in post war years, as consumer devices began to be developed, the field broadened to include modern TV, audio systems, Hi-Fi and latterly computers and microprocessors. In 1946 the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) of John Presper Eckert and John Mauchly followed, beginning the computing era. The arithmetic performance of these machines allowed engineers to develop completely new technologies and achieve new objectives, including the Project Apollo, Apollo missions and the moon landing, NASA moon landing. In the mid-to-late 1950s, the term radio engineering gradually gave way to the name electronics engineering, which then became a stand-alone university degree subject, usually taught alongside electrical engineering with which it had become associated due to some similarities.Solid-state electronics

The first working transistor was a point-contact transistor invented by John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brattain while working under William Shockley at the Bell Telephone Laboratories (BTL) in 1947. They then invented the bipolar junction transistor in 1948. While early junction transistors were relatively bulky devices that were difficult to manufacture on a mass-production basis, they opened the door for more compact devices.

The first integrated circuits were the hybrid integrated circuit invented by Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments in 1958 and the monolithic integrated circuit chip invented by Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959.

The MOSFET (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor, or MOS transistor) was invented by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at BTL in 1959. It was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturised and mass-produced for a wide range of uses. It revolutionized the electronics industry, becoming the most widely used electronic device in the world.

The first working transistor was a point-contact transistor invented by John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brattain while working under William Shockley at the Bell Telephone Laboratories (BTL) in 1947. They then invented the bipolar junction transistor in 1948. While early junction transistors were relatively bulky devices that were difficult to manufacture on a mass-production basis, they opened the door for more compact devices.

The first integrated circuits were the hybrid integrated circuit invented by Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments in 1958 and the monolithic integrated circuit chip invented by Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959.

The MOSFET (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor, or MOS transistor) was invented by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at BTL in 1959. It was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturised and mass-produced for a wide range of uses. It revolutionized the electronics industry, becoming the most widely used electronic device in the world.

Moore's law (1965) File:Federico Faggin (cropped).jpg, Federico Faggin silicon-gate MOSFET (1968) and microprocessor (1971) File:Marcian Ted Hoff.jpg, Marcian Hoff microprocessor (1971) File:Shima and Mazor.jpg, Masatoshi Shima, Stanley Mazor microprocessor (1971)

semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical conductivity value falling between that of a conductor, such as copper, and an insulator, such as glass. Its resistivity falls as its temperature rises; metals behave in the opposite way ...

electronic technology, including MOSFETs in the Interplanetary Monitoring Platform (IMP) and silicon integrated circuit chips in the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC).

The development of MOS integrated circuit technology in the 1960s led to the invention of the microprocessor in the early 1970s. The first single-chip microprocessor was the Intel 4004, released in 1971. The Intel 4004 was designed and realized by Federico Faggin at Intel with his silicon-gate MOS technology, along with Intel's Marcian Hoff and Stanley Mazor and Busicom's Masatoshi Shima.Federico FagginThe Making of the First Microprocessor

''IEEE Solid-State Circuits Magazine'', Winter 2009, IEEE Xplore This ignited the development of the personal computer. The 4004, a 4-bit computing, 4-bit processor, was followed in 1973 by the Intel 8080, an 8-bit computing, 8-bit processor, which made possible the building of the first personal computer, the Altair 8800.

See also

* History of electronic engineering * History of electromagnetic theory * History of radioReferences

External links

Nobel Prize Awards Related to Electrical Engineering

(relevant patents included)

Shock and Awe: The Story of Electricity – Jim Al-Khalili BBC Horizon

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Simon Schaffer, Patricia Fara & Iwan Morus (''In Our Time'', November 4, 2004) {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Electrical Engineering History of electrical engineering, de:Elektrotechnik#Geschichte, Entwicklungen und Personen der Elektrotechnik