History of atheism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

"atheism"

) first list one of the more narrow definitions. * – entry by

Atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

is in the broadest sense a rejection of any belief

A belief is an attitude that something is the case, or that some proposition is true. In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false. To believe something is to tak ...

in the existence of deities

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater ...

. in : "The terms ''ATHEISM'' and ''AGNOSTICISM'' lend themselves to two different definitions. The first takes the privative ''a'' both before the Greek ''theos'' (divinity) and ''gnosis'' (to know) to mean that atheism is simply the absence of belief in the gods and agnosticism is simply lack of knowledge of some specified subject matter. The second definition takes atheism to mean the explicit denial of the existence of gods and agnosticism as the position of someone who, because the existence of gods is unknowable, suspends judgment regarding them ... The first is the more inclusive and recognizes only two alternatives: Either one believes in the gods or one does not. Consequently, there is no third alternative, as those who call themselves agnostics sometimes claim. Insofar as they lack belief, they are really atheists. Moreover, since the absence of belief is the cognitive position in which everyone is born, the burden of proof falls on those who advocate religious belief. The proponents of the second definition, by contrast, regard the first definition as too broad because it includes uninformed children along with aggressive and explicit atheists. Consequently, it is unlikely that the public will adopt it."Most dictionaries (see the OneLook query fo"atheism"

) first list one of the more narrow definitions. * – entry by

Vergilius Ferm

Vergilius Ture Anselm Ferm (January 6, 1896, Sioux City, Iowa – February 4, 1974, Wooster, Ohio): "As commonly understood, atheism is the position that affirms the nonexistence of God. So an atheist is someone who disbelieves in God, whereas a theist is someone who believes in God. Another meaning of 'atheism' is simply nonbelief in the existence of God, rather than positive belief in the nonexistence of God. ... an atheist, in the broader sense of the term, is someone who disbelieves in every form of deity, not just the God of traditional Western theology." The English term 'atheist' was used at least as early as the sixteenth century and atheistic ideas and their influence have a longer history.

In the East, a contemplative life not centered on the idea of deities began in the sixth century BCE with the rise of

It has been claimed that the school died out sometime around the fifteenth century. In the oldest of the

In Western

In Western

Inquisition from Its Establishment to the Great Schism: An Introductory Study

''. . When Christianity became the Roman state religion under

The roots of

The roots of

The History of Freethought and Atheism

". ''An Anthology of Atheism and Rationalism''. New York: Prometheus. Retrieved 2007-APR-03.

According to

According to

While not gaining converts from large portions of the population, versions of deism became influential in certain intellectual circles. Jean Jacques Rousseau challenged the Christian notion that human beings had been tainted by sin since the Garden of Eden, and instead proposed that humans were originally good, only later to be corrupted by civilization. The influential figure of

While not gaining converts from large portions of the population, versions of deism became influential in certain intellectual circles. Jean Jacques Rousseau challenged the Christian notion that human beings had been tainted by sin since the Garden of Eden, and instead proposed that humans were originally good, only later to be corrupted by civilization. The influential figure of  The ''culte de la Raison'' developed during the uncertain period 1792–94 (Years I and III of the Revolution), following the

The ''culte de la Raison'' developed during the uncertain period 1792–94 (Years I and III of the Revolution), following the  Blainey wrote that "atheism seized the pedestal in revolutionary France in the 1790s. The secular symbols replaced the cross. In the cathedral of Notre Dame the altar, the holy place, was converted into a monument to Reason..." During the Terror of 1792–93, France's Christian calendar was abolished, monasteries, convents and church properties were seized and monks and nuns expelled. Historic churches were dismantled. The

Blainey wrote that "atheism seized the pedestal in revolutionary France in the 1790s. The secular symbols replaced the cross. In the cathedral of Notre Dame the altar, the holy place, was converted into a monument to Reason..." During the Terror of 1792–93, France's Christian calendar was abolished, monasteries, convents and church properties were seized and monks and nuns expelled. Historic churches were dismantled. The

In 1844, Karl Marx (1818–1883), an atheistic political economist, wrote in his ''Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right'': "Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people." Marx believed that people turn to religion in order to dull the pain caused by the reality of social situations; that is, Marx suggests religion is an attempt at transcending the material state of affairs in a society—the pain of class oppression—by effectively creating a dream world, rendering the religious believer amenable to social control and exploitation in this world while they hope for relief and justice in life after death. In the same essay, Marx states, " n creates religion, religion does not create man".

In 1844, Karl Marx (1818–1883), an atheistic political economist, wrote in his ''Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right'': "Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people." Marx believed that people turn to religion in order to dull the pain caused by the reality of social situations; that is, Marx suggests religion is an attempt at transcending the material state of affairs in a society—the pain of class oppression—by effectively creating a dream world, rendering the religious believer amenable to social control and exploitation in this world while they hope for relief and justice in life after death. In the same essay, Marx states, " n creates religion, religion does not create man".

Although revolutionary France had taken steps in the direction of state atheism, it was left to Communist and Fascist regimes in the twentieth century to embed atheism as an integral element of national policy.

Although revolutionary France had taken steps in the direction of state atheism, it was left to Communist and Fascist regimes in the twentieth century to embed atheism as an integral element of national policy.

Derek R. Hall, ''The Geographical Journal'', Vol. 165, No. 2, The Changing Meaning of Place in Post-Socialist Eastern Europe: Commodification, Perception and Environment (Jul., 1999), pp. 161–172, Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) "the perception that religion symbolized foreign (Italian, Greek and Turkish) predation was used to justify the communists' stance of state atheism (1967-1991)." going far beyond what most other countries had attempted—completely prohibiting religious observance and systematically repressing and persecuting adherents. Article 37 of the Albanian Constitution of 1976 stipulated, "The state recognizes no religion, and supports atheistic propaganda in order to implant a scientific materialistic world outlook in people." The right to religious practice was restored with the fall of communism in 1991. Further post-war communist victories in the East saw religion purged by atheist regimes across China, North Korea and much of Indo-China. In 1949, mainland China became a Communist state under the leadership of

In India, E. V. Ramasami (Periyar), a prominent atheist leader, fought against

In India, E. V. Ramasami (Periyar), a prominent atheist leader, fought against

The early twenty-first century has continued to see

The early twenty-first century has continued to see  Atheist feminism has also become more prominent in the 2010s. In 2012 the first "Women in Secularism" conference was held. Also, Secular Woman was founded on 28 June 2012 as the first national American organization focused on non-religious women. The mission of Secular Woman is to amplify the voice, presence, and influence of non-religious women. The atheist feminist movement has also become increasingly focused on fighting

Atheist feminism has also become more prominent in the 2010s. In 2012 the first "Women in Secularism" conference was held. Also, Secular Woman was founded on 28 June 2012 as the first national American organization focused on non-religious women. The mission of Secular Woman is to amplify the voice, presence, and influence of non-religious women. The atheist feminist movement has also become increasingly focused on fighting

The History of Freethought and Atheism

at positiveatheism.org. *Dag Herbjørnsrud,

The untold history of India's vital atheist philosophy

at the Blog of the American Philosophical Association (APA), June 2020. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Atheism Atheism

Indian religions

Indian religions, sometimes also termed Dharmic religions or Indic religions, are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent. These religions, which include Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism,Adams, C. J."Classification of ...

such as Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle bein ...

, Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, and various sects of Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

in ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by ...

, and of Taoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Ta ...

in ancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapt ...

. Within the astika ("orthodox") schools of Hindu philosophy

Hindu philosophy encompasses the philosophies, world views and teachings of Hinduism that emerged in Ancient India which include six systems ('' shad-darśana'') – Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimamsa and Vedanta.Andrew Nicholson ( ...

, the Samkhya

''Samkhya'' or ''Sankya'' (; Sanskrit सांख्य), IAST: ') is a dualistic school of Indian philosophy. It views reality as composed of two independent principles, '' puruṣa'' ('consciousness' or spirit); and ''prakṛti'', (nature ...

and the early Mimamsa school did not accept a creator deity

A creator deity or creator god (often called the Creator) is a deity responsible for the creation of the Earth, world, and universe in human religion and mythology. In monotheism, the single God is often also the creator. A number of monolatr ...

in their respective systems.

Philosophical atheist thought began to appear in Europe and Asia in the sixth or fifth century BCE. Will Durant, in his '' The Story of Civilization'', explained that certain pygmy tribes found in Africa were observed to have no identifiable cults or rites. There were no totem

A totem (from oj, ᑑᑌᒼ, italics=no or '' doodem'') is a spirit being, sacred object, or symbol that serves as an emblem of a group of people, such as a family, clan, lineage, or tribe, such as in the Anishinaabe clan system.

While ''the ...

s, no deities, and no spirits. Their dead were buried without special ceremonies or accompanying items and received no further attention. They even appeared to lack simple superstitions, according to travelers' reports.

The Reformation and the Enlightenment fueled skepticism and secularism against religion in Europe.

Etymology

''Atheism '' is derived from theAncient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

ἄθεος ''atheos'' meaning "without gods; godless; secular; refuting or repudiating the existence of gods, especially officially sanctioned gods".

Indian philosophy

In the East, a contemplative life not centered on the idea of deities began in the sixth century BCE with the rise ofJainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle bein ...

, Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, and various sects of Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

in India, and of Taoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Ta ...

in China. These religions offered a philosophic and salvific path not involving deity worship. Deities are not seen as necessary to the salvific goal of the early Buddhist tradition; their reality is explicitly questioned and often rejected. There is a fundamental incompatibility between the notion of gods and basic Buddhist principles, at least in some interpretations. Some Buddhist philosophers assert that belief in an eternal creator god is a distraction from the central task of the religious life.

Within the astika ("orthodox") schools of Hindu philosophy

Hindu philosophy encompasses the philosophies, world views and teachings of Hinduism that emerged in Ancient India which include six systems ('' shad-darśana'') – Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimamsa and Vedanta.Andrew Nicholson ( ...

, the Samkhya

''Samkhya'' or ''Sankya'' (; Sanskrit सांख्य), IAST: ') is a dualistic school of Indian philosophy. It views reality as composed of two independent principles, '' puruṣa'' ('consciousness' or spirit); and ''prakṛti'', (nature ...

and the early Mimamsa school did not accept a creator-deity in their respective systems.

The principal text of the Samkhya

''Samkhya'' or ''Sankya'' (; Sanskrit सांख्य), IAST: ') is a dualistic school of Indian philosophy. It views reality as composed of two independent principles, '' puruṣa'' ('consciousness' or spirit); and ''prakṛti'', (nature ...

school, the ''Samkhya Karika

The Samkhyakarika ( sa, सांख्यकारिका, ) is the earliest surviving text of the Samkhya school of Indian philosophy.Gerald James Larson (1998), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, Motilal Banar ...

'', was written by Ishvara Krishna

''Ishvara'' () is a concept in Hinduism, with a wide range of meanings that depend on the era and the school of Hinduism. Monier Monier Williams, Sanskrit-English dictionarySearch for Izvara University of Cologne, Germany In ancient texts of ...

in the fourth century CE, by which time it was already a dominant Hindu school. The origins of the school are much older and are lost in legend. The school was both dualistic and atheistic. They believed in a dual existence of Prakriti ("nature") and Purusha ("consciousness") and had no place for an Ishvara

''Ishvara'' () is a concept in Hinduism, with a wide range of meanings that depend on the era and the school of Hinduism. Monier Monier Williams, Sanskrit-English dictionarySearch for Izvara University of Cologne, Germany In ancient texts of ...

("God") in its system, arguing that the existence of Ishvara cannot be proved and hence cannot be admitted to exist. The school dominated Hindu philosophy in its day, but declined after the tenth century, although commentaries were still being written as late as the sixteenth century.

The foundational text for the Mimamsa school is the ''Purva Mimamsa Sutras

The Mimamsa Sutra ( sa, मीमांसा सूत्र, ) or the Purva Mimamsa Sutras (ca. 300–200 BCE), written by Rishi Jaimini is one of the most important ancient Hindu philosophical texts. It forms the basis of Mimamsa, the earlies ...

'' of Jaimini

Sage Jaimini was an ancient Indian scholar who founded the Mīmāṃsā school of Hindu philosophy. He is considered to be a disciple of Rishi/Sage Veda Vyasa, the son of Parāśara Rishi. Traditionally attributed to be the author of the ''Mi ...

(c. third to first century BCE). The school reached its height c. 700 CE, and for some time in the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

exerted near-dominant influence on learned Hindu thought. The Mimamsa school saw their primary enquiry was into the nature of dharma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for '' ...

based on close interpretation of the Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute th ...

. Its core tenets were ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized ...

ism ( orthopraxy), antiasceticism and antimysticism. The early Mimamsakas believed in an '' adrishta'' ("unseen") that is the result of performing karmas

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptivel ...

("works") and saw no need for an Ishvara

''Ishvara'' () is a concept in Hinduism, with a wide range of meanings that depend on the era and the school of Hinduism. Monier Monier Williams, Sanskrit-English dictionarySearch for Izvara University of Cologne, Germany In ancient texts of ...

("God") in their system. Mimamsa persists in some subschools of Hinduism today.

Cārvāka

The thoroughly materialistic and antireligious philosophicalCārvāka

Charvaka ( sa, चार्वाक; IAST: ''Cārvāka''), also known as ''Lokāyata'', is an ancient school of Indian materialism. Charvaka holds direct perception, empiricism, and conditional inference as proper sources of knowledge, embra ...

(also known as Lokayata) school that originated in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

with the Bārhaspatya-sūtras (final centuries BCE) is probably the most explicitly atheist school of philosophy in the region, if not the world. These ancient schools of generic skepticism had started to develop far earlier than the Mauryan period

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 1 ...

. Already in the sixth century BCE Ajita Kesakambalin was quoted in Pali scriptures by the Buddhists with whom he was debating, teaching that "with the break-up of the body, the wise and the foolish alike are annihilated, destroyed. They do not exist after death."

Cārvākan philosophy is now known principally from its Astika and Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

opponents. The proper aim of a Cārvākan, according to these sources, was to live a prosperous, happy, productive life in this world. In the book ''More Studies on the Cārvāka/Lokāyata'' (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020) Ramkrishna Bhattacharya

Ramkrishna Bhattacharya was an academic author and exponent of an ancient school of Indian materialism called Carvaka/Lokayata.

He authored 27 books and more than 175 research papers on Indian and European literature, textual criticism (Bangla ...

argues that there have been many varieties of materialist thought in India; and that there is no foundation to the accusations of hedonism nor to the claim that these schools reject inference (''anumāna'') per se as a way of knowledge (''pramāṇas'').

The ''Tattvopaplavasimha'' of Jayarashi Bhatta (c. 8th century) is sometimes cited as a surviving Carvaka text, as Ethan Mills does in ''Three Pillars of Skepticism in Classical India: Nagarjuna, Jayarasi, and Sri Harsa'' (2018It has been claimed that the school died out sometime around the fifteenth century. In the oldest of the

Upanishads

The Upanishads (; sa, उपनिषद् ) are late Vedic Sanskrit texts that supplied the basis of later Hindu philosophy.Wendy Doniger (1990), ''Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism'', 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, , ...

, in chapter 2 of the ''Brhadāranyaka'' (ca. 700 BCE), the leading theorist Yājnavalkya states in a passage often referred to by the irreligious: "so I say, after death there is no awareness." In the main work by the "father of linguistics", Panini (ca. 4th c. BCE), the main (Kasika) commentary on his affix regarding ''nastika'' explains: "an atheist" is one "whose belief is that there is no Hereafter" (4.4.60). Cārvāka arguments are also present in the oldest Sanskrit epic, ''Ramayana

The ''Rāmāyana'' (; sa, रामायणम्, ) is a Sanskrit epic composed over a period of nearly a millennium, with scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text ranging from the 8th to 4th centuries BCE, and later stages ...

'' (early parts from 3rd c. BCE), in which the hero Rama is lectured by the sage Javali – who states that the worship of gods is "laid down in the Shastras by clever people, just to rule over other people and make them submissive and disposed to charity."

The Veda philosopher Adi Shankara

Adi Shankara ("first Shankara," to distinguish him from other Shankaras)(8th cent. CE), also called Adi Shankaracharya ( sa, आदि शङ्कर, आदि शङ्कराचार्य, Ādi Śaṅkarācāryaḥ, lit=First Shanka ...

(ca 790–820), who consolidated the non-dualist ''Advaita Vedanta'' tradition, spends several pages trying to refute the non-religious schools, as he argues against "Unlearned people, and the Lokayatikas (…)"

According to the global historian of ideas Dag Herbjørnsrud

Dag Herbjørnsrud (born 1971) is a historian of ideas, author, a former editor-in-chief, and a founder of Center for Global and Comparative History of Ideas ( Senter for global og komparativ idéhistorie, SGOKI) in Oslo. His writings have been publ ...

, the atheist Carvaka schools were present at the court of the Muslim-born Mughal ruler, Akbar

Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar (25 October 1542 – 27 October 1605), popularly known as Akbar the Great ( fa, ), and also as Akbar I (), was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Hum ...

(1542–1605), an inquiring skeptic who believed in "the pursuit of reason" over "reliance on tradition". When he invited philosophers and representatives of the different religions to his new "House of Worship" (''Ibadat Khana'') in Fatehpur Sikri, Carvakas were present as well. According to the chronicler Abul Fazl (1551–1602), those discussing religious and existential matters at Akbar's court included the atheists:

Herbjørnsrud argues that the Carvaka schools never disappeared in India, and that the atheist traditions of India influenced Europe from the late 16th century: "The Europeans were surprised by the openness and rational doubts of Akbar and the Indians. In Pierre De Jarric

Pierre de Jarric (1566 – 2 March 1617), also known as Pierre du Jarric, was a French people, French Catholic missionary writer from Toulouse.

Jarric entered the Society of Jesus on 8 December 1582 and taught philosophy and moral theology at Bord ...

's ''Histoire'' (1610), based on the Jesuit reports, the Mughal emperor is actually compared to an atheist himself: “Thus we see in this Prince the common fault of the atheist, who refuses to make reason subservient to faith (…)”

Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski

Hannah or Hanna may refer to:

People, biblical figures, and fictional characters

* Hannah (name), a female given name of Hebrew origin

* Hanna (Arabic name), a family and a male given name of Christian Arab origin

* Hanna (Irish surname), a fam ...

concludes as follows concerning the Jesuit descriptions in her paper “East-West Swerves: Cārvāka Materialism and Akbar's Religious Debates at Fatehpur Sikri” (2015):

The Jesuit Roberto De Nobili wrote in 1613 that the “Logaidas” (Lokayatas) "hold the view that the elements themselves are god". Some decades later, Heinrich Roth, who studied Sanskrit in Agra ca. 1654–60, translated the ''Vedantasara'' by the influential Vedantic commentator Sadananda (14th), a text that depicts four different schools of the Carvaka philosophies. Wojciehowski notes: "Rather than proclaiming a Cārvāka renaissance in Akbar's court, it would be safer to suggest that the ancient school of materialism never really went away."

Buddhism

The nonadherence to the notion of a supreme deity or aprime mover

Prime mover may refer to:

Philosophy

*Unmoved mover, a concept in Aristotle's writings

Engineering

* Prime mover (engine), motor, a machine that converts various other forms of energy (chemical, electrical, fluid pressure/flow, etc) into energy ...

is seen by many as a key distinction between Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

and other religions. While Buddhist traditions do not deny the existence of supernatural beings (many are discussed in Buddhist scripture), it does not ascribe powers, in the typical Western sense, for creation, salvation or judgement, to the "gods"; however, praying to enlightened deities is sometimes seen as leading to some degree of spiritual merit.

Buddhists accept the existence of beings in higher realms, known as ''devas'', but they, like humans, are said to be suffering in '' samsara'', and not particularly wiser than we are. In fact the Buddha is often portrayed as a teacher of the deities, and superior to them. Despite this they do have some enlightened Devas in the path of buddhahood.

Jainism

Jains see their tradition as eternal. OrganizedJainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle bein ...

can be dated back to Parshva who lived in the ninth century BCE, and, more reliably, to Mahavira

Mahavira (Sanskrit: महावीर) also known as Vardhaman, was the 24th ''tirthankara'' (supreme preacher) of Jainism. He was the spiritual successor of the 23rd ''tirthankara'' Parshvanatha. Mahavira was born in the early part of the 6 ...

, a teacher of the sixth century BCE, and a contemporary of the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

. Jainism is a dualistic religion with the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the univers ...

made up of matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic part ...

and souls. The universe, and the matter and souls within it, is eternal and uncreated, and there is no omnipotent creator deity in Jainism. There are, however, "gods" and other spirits who exist within the universe and Jains believe that the soul can attain "godhood"; however, none of these supernatural beings exercise any sort of creative activity or have the capacity or ability to intervene in answers to prayers.

Classical Greece and Rome

In Western

In Western Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, theism was the fundamental belief that supported the legitimacy

Legitimacy, from the Latin ''legitimare'' meaning "to make lawful", may refer to:

* Legitimacy (criminal law)

* Legitimacy (family law)

* Legitimacy (political)

See also

* Bastard (law of England and Wales)

* Illegitimacy in fiction

* Legit (d ...

of the state (the ''polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

'', later the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

). Historically, any person who did not believe in any deity supported by the state was fair game to accusations of atheism, a capital crime

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

. Charges of atheism (meaning any subversion of religion) were often used similarly to charges of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

and impiety

Impiety is a perceived lack of proper respect for something considered sacred. Impiety is often closely associated with sacrilege, though it is not necessarily a physical action. Impiety cannot be associated with a cult, as it implies a larger be ...

as a political tool to eliminate enemies. Early Christians

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewis ...

were widely reviled as atheists because they did not participate in the cults of the Greco-Roman gods. During the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, Christians were executed for their rejection of the pagan deities in general and the Imperial cult of ancient Rome in particular.Maycock, A.L. and Ronald Knox (2003). Inquisition from Its Establishment to the Great Schism: An Introductory Study

''. . When Christianity became the Roman state religion under

Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

in 381, heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

became a punishable offense.

Poets and playwrights

Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his ...

(c. 448–380 BCE), known for his satirical style, wrote in his play the ''Knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

'':

"Shrines! Shrines! Surely you don't believe in the gods. What's your argument? Where's your proof?"

Euhemerus

Euhemerus

Euhemerus (; also spelled Euemeros or Evemerus; grc, Εὐήμερος ''Euhēmeros'', "happy; prosperous"; late fourth century BC) was a Greek mythographer at the court of Cassander, the king of Macedon. Euhemerus' birthplace is disputed, with ...

(c. 330–260 BCE) published his view that the gods were only the deified rulers, conquerors, and founders of the past, and that their cults and religions were in essence the continuation of vanished kingdoms and earlier political structures. Although Euhemerus was later criticized for having "spread atheism over the whole inhabited earth by obliterating the gods", his worldview was not atheist in a strict and theoretical sense, because he differentiated them from the primordial deities, holding that they were "eternal and imperishable". Some historians have argued that he merely aimed at reinventing the old religions in the light of the beginning of deification of political rulers such as Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

. Euhemerus' work was translated into Latin by Ennius

Quintus Ennius (; c. 239 – c. 169 BC) was a writer and poet who lived during the Roman Republic. He is often considered the father of Roman poetry. He was born in the small town of Rudiae, located near modern Lecce, Apulia, (Ancient Calabri ...

, possibly to mythographically pave the way for the planned divinization of Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–183 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the best military co ...

in Rome.

Philosophy

The roots of

The roots of Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophy, philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre-Socratic p ...

began in the Greek world in the sixth century BCE. The first Hellenic philosophers were not atheists, but they attempted to explain the world in terms of the processes of nature instead of by mythological accounts. Thus lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

was the result of "wind breaking out and parting the clouds", and earthquakes occurred when "the earth is considerably altered by heating and cooling". The early philosophers often criticized traditional religious notions. Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon (; grc, Ξενοφάνης ὁ Κολοφώνιος ; c. 570 – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer from Ionia who travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early Classica ...

(6th century BCE) famously said that if cows and horses had hands, "then horses would draw the forms of gods like horses, and cows like cows". Another philosopher, Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

(5th century BCE), claimed that the Sun was "a fiery mass, larger than the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

"; a charge of impiety was brought against him, and he was forced to flee Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

.

The first fully materialistic philosophy was produced by the atomists

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms a ...

Leucippus

Leucippus (; el, Λεύκιππος, ''Leúkippos''; fl. 5th century BCE) is a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who has been credited as the first philosopher to develop a theory of atomism.

Leucippus' reputation, even in antiquity, was obscured ...

and Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

(5th century BCE), who attempted to explain the formation and development of the world in terms of the chance movements of atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, a ...

s moving in infinite space.

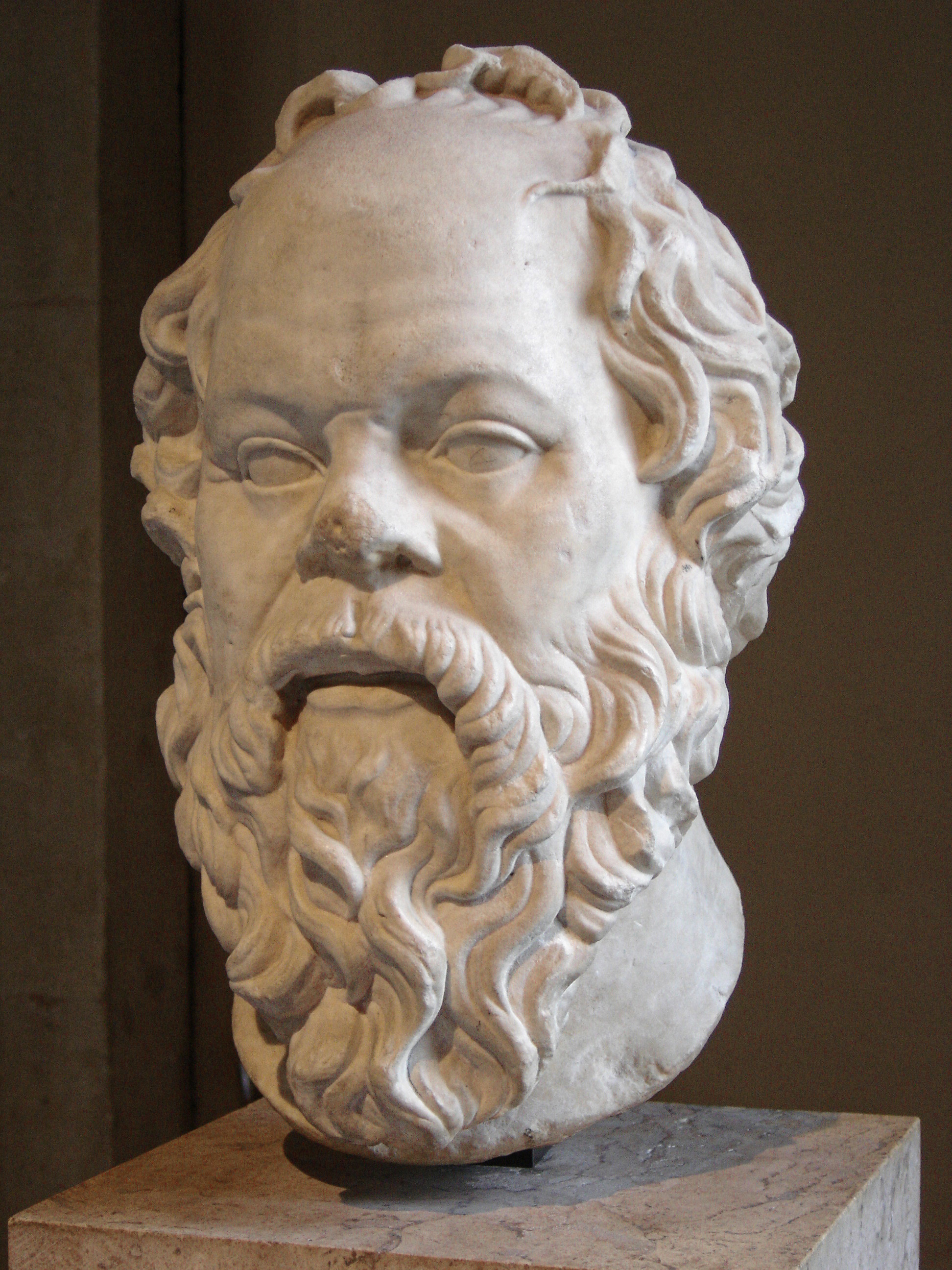

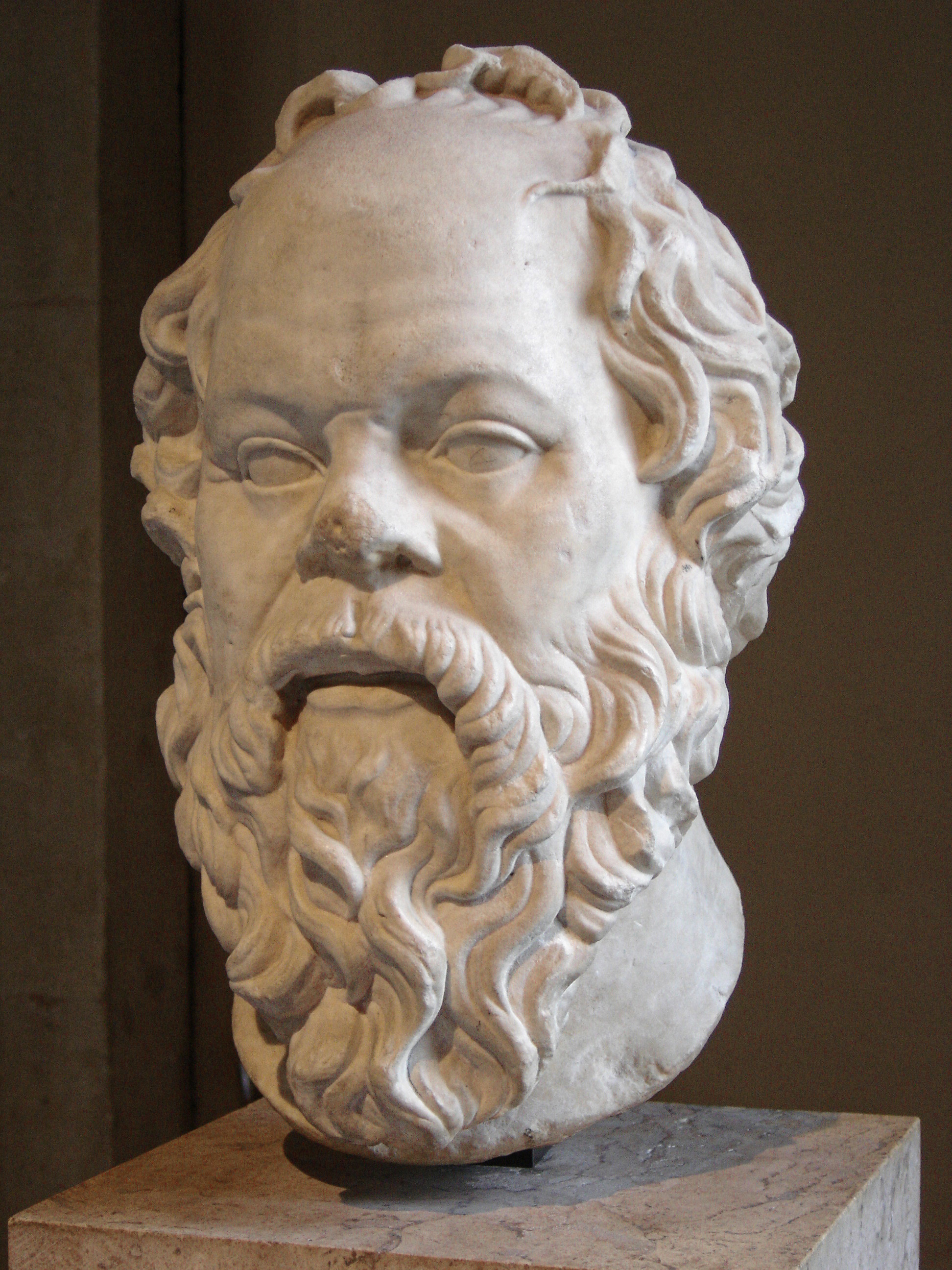

For political reasons, Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

was accused of being ''atheos'' ("refusing to acknowledge the gods recognized by the state"). The Athenian public associated Socrates (c. 470–399 BCE) with the trends in pre-Socratic philosophy towards naturalistic inquiry and the rejection of divine explanations for phenomena. Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his ...

' comic play ''The Clouds

''The Clouds'' ( grc, Νεφέλαι ''Nephelai'') is a Greek comedy play written by the playwright Aristophanes. A lampooning of intellectual fashions in classical Athens, it was originally produced at the City Dionysia in 423BC and was not ...

'' (performed 423 BCE) portrayed Socrates as teaching his students that the traditional Greek deities did not exist. Socrates was later tried and executed under the charge of not believing in the gods of the state and instead worshipping foreign gods. Socrates himself vehemently denied the charges of atheism at his trial. in All the surviving sources about him indicate that he was a very devout man, who prayed to the rising sun and believed that the oracle at Delphi

Pythia (; grc, Πυθία ) was the name of the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. She specifically served as its oracle and was known as the Oracle of Delphi. Her title was also historically glossed in English as the Pythoness ...

spoke the word of Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

.

While only a few of the ancient Greco-Roman schools of philosophy were subject to accusations of atheism, there were some individual philosophers who espoused atheist views. The Peripatetic

Peripatetic may refer to:

*Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BC), and ''peripatetic'' is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

...

philosopher Strato of Lampsacus did not believe in the existence of gods. The Cyrenaic

The Cyrenaics or Kyrenaics ( grc, Κυρηναϊκοί, Kyrēnaïkoí), were a sensual hedonist Greek school of philosophy founded in the 4th century BCE, supposedly by Aristippus of Cyrene, although many of the principles of the school are bel ...

philosopher Theodorus the Atheist

Theodorus the Atheist ( el, Θεόδωρος ὁ ἄθεος; c. 340 – c. 250 BCE), of Cyrene, was a Greek philosopher of the Cyrenaic school. He lived in both Greece and Alexandria, before ending his days in his native city of Cyrene. As a C ...

(c. 300 BCE) is supposed to have denied that gods exist and wrote a book ''On the Gods'' expounding his views.

The Sophists

In the fifth century BCE theSophists

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ' ...

began to question many of the traditional assumptions of Greek culture. Prodicus of Ceos was said to have believed that "it was the things which were serviceable to human life that had been regarded as gods", and Protagoras

Protagoras (; el, Πρωταγόρας; )Guthrie, p. 262–263. was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and rhetorical theorist. He is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue '' Protagoras'', Plato credits him with inventing t ...

stated at the beginning of a book that "With regard to the gods I am unable to say either that they exist or do not exist". Diagoras of Melos

Diagoras "the Atheist" of Melos ( el, Διαγόρας ὁ Μήλιος) was a Greek poet and sophist of the 5th century BC. Throughout antiquity, he was regarded as an atheist, but very little is known for certain about what he actually believed ...

allegedly chopped up a wooden statue of Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptiv ...

and used it to roast his lentils and revealed the secrets of the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries ( el, Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια, Eleusínia Mystḗria) were initiations held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Elefsina in ancient Greece. They are t ...

. The Athenians accused him of impiety

Impiety is a perceived lack of proper respect for something considered sacred. Impiety is often closely associated with sacrilege, though it is not necessarily a physical action. Impiety cannot be associated with a cult, as it implies a larger be ...

and banished him from their city. Critias was said as well to deny that the gods existed.

Epicureanism

The most important Greek thinker in the development of atheism wasEpicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influence ...

( 300 BCE). Drawing on the ideas of Democritus and the Atomists, he espoused a materialistic philosophy according to which the universe was governed by the laws of chance without the need for divine intervention (see scientific determinism). Although Epicurus still maintained that the gods existed, he believed that they were uninterested in human affairs. The aim of the Epicureans was to attain ''ataraxia

''Ataraxia'' (Greek: ἀταραξία, from ("a-", negation) and ''tarachē'' "disturbance, trouble"; hence, "unperturbedness", generally translated as "imperturbability", " equanimity", or "tranquility") is a Greek term first used in Ancient ...

'' (a mental state of being untroubled). One important way of doing this was by exposing fear of divine wrath as irrational. The Epicureans also denied the existence of an afterlife and the need to fear divine punishment after death.

One of the most eloquent expressions of Epicurean thought is Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem '' De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

' ''On the Nature of Things

''De rerum natura'' (; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius ( – c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some ...

'' (1st century BCE) in which he held that gods exist but argued that religious fear was one of the chief causes of human unhappiness and that the gods did not involve themselves in the world. The Epicureans also denied the existence of an afterlife and hence dismissed the fear of death.

Epicureans denied being atheists but their critics insisted they were. One explanation for this alleged crypto-atheism is that they feared persecution, and while they avoided this their teachings were controversial and harshly attacked by some of the other schools, particularly Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting tha ...

and Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ...

.

Pyrrhonism

Similar to the Epicureans, thePyrrhonists

Pyrrho of Elis (; grc, Πύρρων ὁ Ἠλεῖος, Pyrrhо̄n ho Ēleios; ), born in Elis, Greece, was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek skeptic philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism.

Life

...

employed a tactic to avoid persecution for atheism in which they, in conformity with ancestral customs and laws, declared that the gods exist, and performed everything which contributes to their worship and veneration, but, with regard to philosophy, declined to commit themselves to the gods' existence. The Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman Pyrrhonism, and ...

compiled a large number of ancient arguments against the existence of gods, recommending that one should suspend judgment regarding the matter. His large volume of surviving works had a lasting influence on later philosophers.Stein, Gordon (Ed.) (1980).The History of Freethought and Atheism

". ''An Anthology of Atheism and Rationalism''. New York: Prometheus. Retrieved 2007-APR-03.

Medicine

In pre-Hippocratic times, Greeks believed that gods controlled all aspects of human existence, including health and disease. One of the earliest works that challenged the religious view was '' On the Sacred Disease'', written about 400 B.C. The anonymous author argued that the "sacred disease" ofepilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of non-communicable neurological disorders characterized by recurrent epileptic seizures. Epileptic seizures can vary from brief and nearly undetectable periods to long periods of vigorous shaking due to abnormal electrica ...

has a natural cause, and that the idea of its supposed divine origin is based on human inexperience.

The Middle Ages

Islamic world

In the early history of Islam, Muslim scholars recognized the idea of atheism and frequently attacked unbelievers, although they were unable to name any atheists. When individuals were accused of atheism, they were usually viewed as heretics rather than proponents of atheism. However, there werefreethinkers

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and that beliefs should instead be reached by other methods ...

and outspoken critics of the Islamic religion such as deists, philosophers

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, rationalists

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosoph ...

, and atheists in the medieval Islamic world, one notable figure being the 9th-century scholar Ibn al-Rawandi, who criticized the notion of religious prophecy

In religion, a prophecy is a message that has been communicated to a person (typically called a ''prophet'') by a supernatural entity. Prophecies are a feature of many cultures and belief systems and usually contain divine will or law, or p ...

, including that of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

, and maintained that religious dogmas were not acceptable to reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, lang ...

and must be rejected. Other critics of religion in the Islamic world include the poet Al-Maʿarri

Abū al-ʿAlāʾ al-Maʿarrī ( ar, أبو العلاء المعري, full name , also known under his Latin name Abulola Moarrensis; December 973 – May 1057) was an Arab philosopher, poet, and writer. Despite holding a controversially irreli ...

(973–1057), the scholar Abu Isa al-Warraq

Abu Isa al-Warraq, full name ''Abū ʿĪsā Muḥammad ibn Hārūn al-Warrāq'' ( ar, أبو عيسى محمد بن هارون الوراق, died 861-2 AD/247 AH), was a 9th-century Arab skeptic scholar and critic of Islam and religion in gener ...

(fl. 9th century), and the physician and philosopher Abu Bakr al-Razi (865–925). However, al-Razi's atheism may have been "deliberately misdescribed" by an Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor ( imām) to Ja'far al ...

missionary named Abu Hatim. Al-Maʿarri wrote and taught that religion itself was a "fable invented by the ancients"Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, 1962, ''A Literary History of the Arabs'', page 318. Routledge and that humans were "of two sorts: those with brains, but no religion, and those with religion, but no brains."

Europe

The titular character of the Icelandic saga Hrafnkell, written in the late thirteenth century, says, "I think it is folly to have faith in gods". After his temple to Freyr is burnt and he is enslaved, he vows never to perform anothersacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

, a position described in the sagas as ''goðlauss'', "godless". Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He is known as the discoverer of Grimm's law of linguistics, the co-author of t ...

in his '' Teutonic Mythology'' observes,

It is remarkable that Old Norse legend occasionally mentions certain men who, turning away in utter disgust and doubt from the heathen faith, placed their reliance on their own strength and virtue. Thus in the Sôlar lioð 17 we read of Vêbogi and Râdey ''â sik þau trûðu,'' "in themselves they trusted",citing several other examples, including two kings. Subsequent to Grimm's investigation, scholars including J. R. R. Tolkien and E.O.G. Turville-Petre have identified the goðlauss ethic as a stream of atheistic and/or humanistic philosophy in the Icelandic sagas. People described as goðlauss expressed not only a lack of faith in deities, but also a pragmatic belief in their own faculties of strength, reason and virtue and in social codes of honor independent of any supernatural agency. Another phenomenon in the Middle Ages was proofs of the existence of God. Both

Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury, OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also called ( it, Anselmo d'Aosta, link=no) after his birthplace and (french: Anselme du Bec, link=no) after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher and theologian of th ...

, and later, William of Ockham

William of Ockham, OFM (; also Occam, from la, Gulielmus Occamus; 1287 – 10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small vil ...

acknowledge adversaries who doubt the existence of God. Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, Dominican Order, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino, Italy, Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest who was an influential List of Catholic philo ...

' five proofs of God's existence and Anselm's ontological argument implicitly acknowledged the validity of the question about God's existence. Frederick Copleston

Frederick Charles Copleston (10 April 1907 – 3 February 1994) was an English Roman Catholic Jesuit priest, philosopher, and historian of philosophy, best known for his influential multi-volume '' A History of Philosophy'' (1946–75).

...

, however, explains that Thomas laid out his proofs not to counter atheism, but to address certain early Christian writers such as John of Damascus

John of Damascus ( ar, يوحنا الدمشقي, Yūḥanna ad-Dimashqī; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Δαμασκηνός, Ioánnēs ho Damaskēnós, ; la, Ioannes Damascenus) or John Damascene was a Christian monk, priest, hymnographer, and ...

, who asserted that knowledge of God's existence was naturally innate in man, based on his natural desire for happiness.Frederick Copleston. 1950. ''A History of Philosophy: Volume II: Medieval Philosophy: From Augustine to Duns Scotus.'' London: Burns, Oates & Washbourne. pp. 336–337 Thomas stated that although there is desire for happiness which forms the basis for a proof of God's existence in man, further reflection is required to understand that this desire is only fulfilled in God, not for example in wealth or sensual pleasure. However, Aquinas's Five Ways also address (hypothetical) atheist arguments citing evil in the universe and claiming that God's existence is unnecessary to explain things.

The charge of atheism was used to attack political or religious opponents. Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani family was of baronial ...

, because he insisted on the political supremacy of the church, was accused by his enemies after his death of holding (unlikely) positions such as "neither believing in the immortality nor incorruptibility of the soul, nor in a life to come".

John Arnold's 2005 ''Belief and Unbelief in Medieval Europe'' discusses individuals who were indifferent to the Church and did not participate in faith practices. Arnold notes that while these examples could be perceived as simply people being lazy, it demonstrates that "belief was not universally fervent". Arnold enumerates examples of people not attending church, and even those who excluded the Church from their marriage. Disbelief, Arnold argues, stemmed from boredom. Arnold argues that while some blasphemy implies the existence of God, laws demonstrate that there were also cases of blasphemy that directly attacked articles of faith. Italian preachers in the fourteenth century also warned of unbelievers and people who lacked belief.

Renaissance and Reformation

During the time of theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

and the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, criticism of the religious establishment became more frequent in predominantly Christian countries, but did not amount to atheism, ''per se''.

The term ''athéisme'' was coined in France in the sixteenth century. The word "atheist" appears in English books at least as early as 1566.

The concept of atheism re-emerged initially as a reaction to the intellectual and religious turmoil of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

and the Reformation, as a charge used by those who saw the denial of god and godlessness in the controversial positions being put forward by others. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the word 'atheist' was used exclusively as an insult; nobody wanted to be regarded as an atheist. Although one overtly atheistic compendium known as the '' Theophrastus redivivus'' was published by an anonymous author in the seventeenth century, atheism was an epithet implying a lack of moral restraint.

According to

According to Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Norman Blainey (born 11 March 1930) is an Australian historian, academic, best selling author and commentator. He is noted for having written authoritative texts on the economic and social history of Australia, including '' The Tyranny ...

, the Reformation in Europe had paved the way for atheists by attacking the authority of the Catholic Church, which in turn "quietly inspired other thinkers to attack the authority of the new Protestant churches". Deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning " god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation o ...

gained influence in France, Prussia and England, and proffered belief in a noninterventionist deity, but "while some deists were atheists in disguise, most were religious, and by today's standards would be called true believers". The scientific and mathematical discoveries of such as Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

, Newton and Descartes sketched a pattern of natural laws that lent weight to this new outlook.

How dangerous it was to be accused of being an atheist at this time is illustrated by the examples of Étienne Dolet, who was strangled and burned in 1546. The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book '' Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

(1588–1679) was also accused of atheism, but he denied it. His theism was unusual, in that he held god to be material. Even earlier, the British playwright and poet Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon t ...

(1563–1593) was accused of atheism when a tract denying the divinity of Christ was found in his home. Before he could finish defending himself against the charge, Marlowe was murdered. Giulio Cesare Vanini, also accused of being an atheist, was burned at the stake in 1619.

Blainey wrote that the Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, ...

was "probably the first well known 'semi-atheist' to announce himself in a Christian land in the modern era", although nowhere in his work does Spinoza argue against the existence of God. It is a widespread belief that Spinoza equated God with the material universe and so his beliefs have been categorized as Pantheist. Spinoza had been expelled from his synagogue for his protests against the teachings of its rabbis and for failing to attend Saturday services. He believed that God did not interfere in the running of the world, but rather that natural laws explained the workings of the universe. In 1661 he published his '' Short Treatise on God'', but he was not a popular figure for the first century following his death: "An unbeliever was expected to be a rebel in almost everything and wicked in all his ways", wrote Blainey, "but here was a virtuous one. He lived the good life and made his living in a useful way. . . . It took courage to be a Spinoza or even one of his supporters. If a handful of scholars agreed with his writings, they did not so say in public".

In early modern times, the first explicit atheist known by name was the German-languaged Danish critic of religion Matthias Knutzen

Matthias Knutzen (also: ''Knuzen'', ''Knutsen'') (1646 – after 1674) was a German critic of religion and the author of three atheistic pamphlets. In modern Western history, he is the first atheist known by name and in person. Knutzen was called ...

(1646–after 1674), who published three atheist writings in 1674. Knutzen was called "The only person on record who openly professed and taught atheism" in the 1789 Students Pocket Dictionary of Universal History by Thomas Mortimer.

In 1689 the Polish nobleman Kazimierz Łyszczyński, who had denied the existence of God in his philosophical treatise ''De non-existentia Dei'', was imprisoned unlawfully; despite Warsaw Confederation tradition and King Sobieski's intercession, Łyszczyński was condemned to death for atheism and beheaded in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

after his tongue was pulled out with a burning iron and his hands slowly burned. In ''De non-existentia Dei'' he had demonstrated strong atheism:

The Age of Enlightenment

While not gaining converts from large portions of the population, versions of deism became influential in certain intellectual circles. Jean Jacques Rousseau challenged the Christian notion that human beings had been tainted by sin since the Garden of Eden, and instead proposed that humans were originally good, only later to be corrupted by civilization. The influential figure of

While not gaining converts from large portions of the population, versions of deism became influential in certain intellectual circles. Jean Jacques Rousseau challenged the Christian notion that human beings had been tainted by sin since the Garden of Eden, and instead proposed that humans were originally good, only later to be corrupted by civilization. The influential figure of Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

spread deistic notions to a wide audience. "After the French Revolution and its outbursts of atheism, Voltaire was widely condemned as one of the causes", wrote Blainey, "Nonetheless, his writings did concede that fear of God was an essential policeman in a disorderly world: 'If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him', wrote Voltaire". Voltaire's assertion occurs in his Épître à l'Auteur du Livre des Trois Imposteurs, written in response to the Treatise of the Three Impostors

The ''Treatise of the Three Impostors'' ( la, De Tribus Impostoribus) was a long-rumored book denying all three Abrahamic religions: Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, with the "impostors" of the title being Jesus, Moses, and Muhammad. Hearsay co ...

, a document (most likely) authored by John Toland

John Toland (30 November 167011 March 1722) was an Irish rationalist philosopher and freethinker, and occasional satirist, who wrote numerous books and pamphlets on political philosophy and philosophy of religion, which are early expressions o ...

that denied all three Abrahamic religions. In 1766, Voltaire tried unsuccessfully to have the judgment reversed in the case of the French nobleman François-Jean de la Barre

François-Jean Lefebvre de la Barre (12 September 17451 July 1766) was a young French nobleman. He was tortured and beheaded before his body was burnt on a pyre along with Voltaire's ''Philosophical Dictionary'' nailed to his torso. La Barre i ...

who was torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

d, beheaded, and his body burned for alleged vandalism

Vandalism is the action involving deliberate destruction of or damage to public or private property.

The term includes property damage, such as graffiti and defacement directed towards any property without permission of the owner. The ter ...

of a crucifix

A crucifix (from Latin ''cruci fixus'' meaning "(one) fixed to a cross") is a cross with an image of Jesus on it, as distinct from a bare cross. The representation of Jesus himself on the cross is referred to in English as the ''corpus'' (La ...

.

Arguably the first book in modern times solely dedicated to promoting atheism was written by French Catholic priest Jean Meslier (1664–1729), whose posthumously published lengthy philosophical essay (part of the original title: ''Thoughts and Feelings of Jean Meslier ... Clear and Evident Demonstrations of the Vanity and Falsity of All the Religions of the World'') rejects the concept of God (both in the Christian and also in the Deistic sense), the soul, miracles and the discipline of theology.Michel Onfray (2007). ''Atheist Manifesto: The Case Against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam''. Arcade Publishing. . p. 29 Philosopher Michel Onfray

Michel Onfray (; born 1 January 1959) is a French writer and philosopher with a hedonistic, epicurean and atheist worldview. A highly-prolific author on philosophy, he has written over 100 books. His philosophy is mainly influenced by such thin ...

states that Meslier's work marks the beginning of "the history of true atheism".

By the 1770s, atheism in some predominantly Christian countries was ceasing to be a dangerous accusation that required denial, and was evolving into a position openly avowed by some. The first open denial of the existence of God and avowal of atheism since classical times may be that of Baron d'Holbach

Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach (; 8 December 1723 – 21 January 1789), was a French-German philosopher, encyclopedist, writer, and prominent figure in the French Enlightenment. He was born Paul Heinrich Dietrich in Edesheim, near L ...

(1723–1789) in his 1770 work, '' The System of Nature''. D'Holbach was a Parisian social figure who conducted a famous salon widely attended by many intellectual notables of the day, including Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment ph ...

, Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

, and Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

. Nevertheless, his book was published under a pseudonym, and was banned and publicly burned by the Executioner. Diderot, one of the Enlightenment's most prominent ''philosophes'' and editor-in-chief of the Encyclopédie

''Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (English: ''Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts''), better known as ''Encyclopédie'', was a general encyclopedia publis ...

, which sought to challenge religious, particularly Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, dogma said, "Reason is to the estimation of the ''philosophe'' what grace is to the Christian", he wrote. "Grace determines the Christian's action; reason the ''philosophe''.David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment ph ...

produced a six volume history of England in 1754, which gave little attention to God. He implied that if God existed he was impotent in the face of European upheaval. Hume ridiculed miracles, but walked a careful line so as to avoid being too dismissive of Christianity. With Hume's presence, Edinburgh gained a reputation as a "haven of atheism", alarming many ordinary Britons.

The ''culte de la Raison'' developed during the uncertain period 1792–94 (Years I and III of the Revolution), following the

The ''culte de la Raison'' developed during the uncertain period 1792–94 (Years I and III of the Revolution), following the September massacres

The September Massacres were a series of killings of prisoners in Paris that occurred in 1792, from Sunday, 2 September until Thursday, 6 September, during the French Revolution. Between 1,176 and 1,614 people were killed by '' fédérés'', gu ...

, when Revolutionary France was rife with fears of internal and foreign enemies. Several Parisian churches were transformed into Temples of Reason, notably the Church of Saint-Paul Saint-Louis in the Marais. The churches were closed in May 1793 and more securely 24 November 1793, when the Catholic Mass

The Mass is the central liturgical service of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, in which bread and wine are consecrated and become the body and blood of Christ. As defined by the Church at the Council of Trent, in the Mass, "the same Chri ...

was forbidden.

Blainey wrote that "atheism seized the pedestal in revolutionary France in the 1790s. The secular symbols replaced the cross. In the cathedral of Notre Dame the altar, the holy place, was converted into a monument to Reason..." During the Terror of 1792–93, France's Christian calendar was abolished, monasteries, convents and church properties were seized and monks and nuns expelled. Historic churches were dismantled. The

Blainey wrote that "atheism seized the pedestal in revolutionary France in the 1790s. The secular symbols replaced the cross. In the cathedral of Notre Dame the altar, the holy place, was converted into a monument to Reason..." During the Terror of 1792–93, France's Christian calendar was abolished, monasteries, convents and church properties were seized and monks and nuns expelled. Historic churches were dismantled. The Cult of Reason

The Cult of Reason (french: Culte de la Raison) was France's first established state-sponsored atheistic religion, intended as a replacement for Roman Catholicism during the French Revolution. After holding sway for barely a year, in 1794 it ...

was a creed based on atheism devised during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

by Jacques Hébert

Jacques René Hébert (; 15 November 1757 – 24 March 1794) was a French journalist and the founder and editor of the extreme radical newspaper '' Le Père Duchesne'' during the French Revolution.

Hébert was a leader of the French Revolution ...

, Pierre Gaspard Chaumette