History of antisemitism in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

There have been different opinions among historians with regard to the extent of antisemitism in America's past and how American antisemitism contrasted with its European counterpart. Earlier students of American Jewish life minimized the presence of

Between 1881 and 1920, approximately 3 million

Between 1881 and 1920, approximately 3 million

In the middle of the 19th century, a number of German Jewish immigrants founded investment banking firms which later became mainstays of the industry. Most prominent Jewish banks in the United States were investment banks, rather than

In the middle of the 19th century, a number of German Jewish immigrants founded investment banking firms which later became mainstays of the industry. Most prominent Jewish banks in the United States were investment banks, rather than

In the first half of the 20th century, Jews were discriminated against in employment, access to residential and resort areas, membership in clubs and organizations, and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrollment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. Restaurants, hotels and other establishments that barred Jews from entry were called "restricted".

In the first half of the 20th century, Jews were discriminated against in employment, access to residential and resort areas, membership in clubs and organizations, and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrollment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. Restaurants, hotels and other establishments that barred Jews from entry were called "restricted".

In a 1938 poll, approximately 60 percent of the respondents held a low opinion of Jews, labeling them "greedy," "dishonest," and "pushy." 41 percent of respondents agreed that Jews had "too much power in the United States," and this figure rose to 58 percent by 1945. Several surveys taken from 1940 to 1946 found that Jews were seen as a greater threat to the welfare of the United States than any other national, religious, or racial group.

In a 1938 poll, approximately 60 percent of the respondents held a low opinion of Jews, labeling them "greedy," "dishonest," and "pushy." 41 percent of respondents agreed that Jews had "too much power in the United States," and this figure rose to 58 percent by 1945. Several surveys taken from 1940 to 1946 found that Jews were seen as a greater threat to the welfare of the United States than any other national, religious, or racial group.

''New York Daily News'', August 23, 2001. According to

During the early 1980s,

During the early 1980s,

, ''New Internationalist'', October 2004. This was mainly in the area of

"Right woos Left"

Publiceye.org, December 20, 1990; revised February 22, 1994, revised again 1999. As they interacted, some of the classic right-wing antisemitic

online

*Gerber, David A., ed. ''Anti-Semitism in American History'' (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), scholarly essays. * Gerteis, Joseph, and Nir Rotem. "Connecting the 'Others': White Anti-Semitic and Anti-Muslim Views in America." ''Sociological Quarterly'' (2022): 1-21. * Goldstein, Judith S. ''The Politics of Ethnic Pressure: The American Jewish Committee Fight against Immigration Restriction, 1906–1917'' (Routledge, 2020

online

* Halperin, Edward C. "Why did the United States medical school admissions quota for Jews end?" ''American Journal of the Medical Sciences'' 358.5 (2019): 317-325. * Handlin, Oscar, and Mary F. Handlin. "The Acquisition of Political and Social Rights by the Jews in the United States." ''The American Jewish Year Book'' (1955): 43-98

online

* Handlin, Oscar. “American Views of the Jew at the Opening of the Twentieth Century.” ''Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society'' 40#4, 1951, pp. 323–44

online

** Pollack, Norman. "Handlin on Anti-Semitism: A Critique of 'American Views of the Jew'." ''Journal of American History'' 51.3 (1964): 391-403

online

* Higham, John. ''Strangers in the land: Patterns of American nativism, 1860-1925'' (1955) a famous classic

online

* Higham, John. ''Send these to me: immigrants in urban America'' (2nd ed. 1984

online

extensive coverage of anti-semitism * Higham, John. "Social discrimination against Jews in America, 1830-1930." ''Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society'' 47.1 (1957): 1-33

online

*Jaher, Frederic Cople. ''A Scapegoat in the Wilderness: The Origins and Rise of Anti-Semitism in America'' (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994), a standard scholarly history. * Jacobs, Steven Leonard. "Antisemitism in the American Religious Landscape: The Present Twenty-First Century Moment." ''Socio-Historical Examination of Religion and Ministry'' 3.2 (2021

online

*Levinger, Lee J. ''Anti-Semitism in the United States: Its History and Causes'' (1925). outdated * Levy, Richard S., ed. ''Antisemitism: A historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution'' (2 vol, Abc-clio, 2005), worldwide coverage by experts

excerpt

* Marinari, Maddalena. ''Unwanted: Italian and Jewish mobilization against restrictive immigration laws, 1882–1965'' (UNC Press Books, 2019). *Martire, Gregory and Ruth Clark. ''Anti-Semitism in the United States: A Study of Prejudice in the 1980s'' (New York, N.Y.: Praeger, 1982). * Rausch, David A. ''Fundamentalist-evangelicals and Anti-semitism'' (Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1993). * Rosenfeld, Alvin H. "Antisemitism in Today’s America." in ''An End to Antisemitism!'' (2021): 367

online

*Scholnick, Myron I. ''The New Deal and Anti-Semitism in America'' (New York: Garland Pub., 1990). *Selzer, Michael, ed. '' 'Kike!:' A Documentary History of Anti-Semitism in America'' (New York, World Pub. 1972). * Thernstrom, Stephan, Ann Orlov, and Oscar Handlin, eds. ''Harvard encyclopedia of American ethnic groups'' (Harvard UP) (1980); scholarly coverage of every major ethnic group * Valbousquet, Nina. "'Un-American' Antisemitism?: The American Jewish Committee's Response to Global Antisemitism in the Interwar Period." ''American Jewish History'' 105.1 (2021): 77-102

excerpt

*Volkman, Ernest. ''A Legacy of Hate: Anti-Semitism in America'' (New York: F. Watts, 1982); popular history.

online

* Dobkowski, Michael N. “American Anti-Semitism: A Reinterpretation.” ''American Quarterly'' 29#2, (1977), pp. 166–81

online

emphasis on popular stereotypes * Dobkowski, Michael N. "American antisemitism and American historians: A critique." ''Patterns of Prejudice'' 14.2 (1980): 33-43

excerpt

* Gordan, Rachel. "The 1940s as the Decade of the Anti-Antisemitism Novel." ''Religion and American Culture'' 31.1 (2021): 33-81

online

* Koffman, David S., et al. "Roundtable on Anti-Semitism in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 19.3 (2020): 473-505. * Kranson, Rachel. "Rethinking the Historiography of American Antisemitism in the Wake of the Pittsburgh Shooting." ''American Jewish History'' 105.1 (2021): 247-253

excerpt

* MacDonald, Kevin. "Jewish involvement in shaping American immigration policy, 1881–1965: A historical review." ''Population and Environment'' 19.4 (1998): 295-356. * Pollack, Norman. "The Myth of Populist Anti-Semitism." ''American Historical Review'' 68.1 (1962): 76-80

online

* Rockaway, Robert, and Arnon Gutfeld. "Demonic images of the Jew in the nineteenth century United States." ''American Jewish History'' 89.4 (2001): 355-381

online

* Rockaway, Robert. "Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate." ''American Jewish History'' 89.4 (2001): 467-469

summary

* Stember, Charles, ed. ''Jews in the Mind of America'' (1966

online

* Tevis, Britt P. "Trends in the Study of Antisemitism in United States History." ''American Jewish History'' 105.1 (2021): 255-284

excerpt

* Varat, Deborah. " 'Their New Jerusalem': Representations of Jewish Immigrants in the American Popular Press, 1880–1903." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 20.2 (2021): 277-300. * Winston, Andrew S. "'Jews will not replace us!': Antisemitism, Interbreeding and Immigration in Historical Context." ''American Jewish History'' 105.1 (2021): 1-24

excerpt

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Antisemitism In The United States Jewish-American history History of the United States by topic

antisemitism in the United States

Antisemitism in the United States has existed for centuries. In the United States, most Jewish community relations agencies draw distinctions between antisemitism, which is measured in terms of attitudes and behaviors, and the security and status ...

, which they considered a late and alien phenomenon that arose on the American scene in the late 19th century. More recently however, scholars have asserted that no period in American Jewish history was free from antisemitism. The debate about the significance of antisemitism during different periods of American history

The history of the lands that became the United States began with the arrival of the first people in the Americas around 15,000 BC. Numerous indigenous cultures formed, and many saw transformations in the 16th century away from more densel ...

has continued to the present day.

The first governmental incident of anti-Jewish sentiment was recorded during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, when General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

issued a General Order

A general order, in military and paramilitary organizations, is a published directive, originated by a commander and binding upon all personnel under his or her command. Its purpose is to enforce a policy or procedure unique to the unit's situatio ...

(quickly rescinded by President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

) of expulsion against Jews from the portions of Tennessee, Kentucky and Mississippi that were under his control.

During the first half of the 20th century, Jews were discriminated against and barred from working in some fields of employment, barred from renting and/or owning certain properties, not accepted as members by social clubs, barred from resort areas and barred from enrolling in colleges by quotas. Antisemitism reached its peak during the interwar period with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

in the 1920s, antisemitic publications in The Dearborn Independent, and incendiary radio speeches by Father Coughlin

Charles Edward Coughlin ( ; October 25, 1891 – October 27, 1979), commonly known as Father Coughlin, was a Canadian-American Catholic priest based in the United States near Detroit. He was the founding priest of the National Shrine of th ...

in the late 1930s.

Following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

, anti-Jewish sentiment significantly declined in the United States. However, there has been an upsurge in the number of antisemitic hate crime

A hate crime (also known as a bias-motivated crime or bias crime) is a prejudice-motivated crime which occurs when a perpetrator targets a victim because of their membership (or perceived membership) of a certain social group or racial demograph ...

s in recent years.

Colonial era

In the mid 17th century,Peter Stuyvesant

Peter Stuyvesant (; in Dutch also ''Pieter'' and ''Petrus'' Stuyvesant, ; 1610 – August 1672)Mooney, James E. "Stuyvesant, Peter" in p.1256 was a Dutch colonial officer who served as the last Dutch director-general of the colony of New Ne ...

, the last Director-General of the Dutch colony of New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva ...

, sought to maintain the position of the Dutch Reformed Church in America refusing to allow other denominations such as Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

, Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

the right to organize a church. He also described Jews as "deceitful", "very repugnant", and "hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ". Prior to this, the inhabitants of the Dutch settlement of Vlishing had declared that "the law of love, peace, and liberty" extended to "Jews, Turks, and Egyptians."

19th century

According to Peter Knight, throughout most of the 18th and 19th centuries, the United States rarely experienced antisemitic action comparable to the sort that was endemic in Europe during the same period. Jews were viewed as a race beginning in the 1870s, but this understanding was considered positive, as Jews were viewed aswhite

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

.

Civil War

Major GeneralUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

was influenced by these sentiments and issued General Order No. 11 expelling Jews from areas under his control in western Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers, delineated by state law. Its ...

:

The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled ... within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.Grant later issued an order "that no Jews are to be permitted to travel on the road southward." His aide, Colonel John V. DuBois, ordered "all cotton speculators, Jews, and all vagabonds with no honest means of support", to leave the district. "The Israelites especially should be kept out ... they are such an intolerable nuisance." This order was quickly rescinded by President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

but not until it had been enforced in a number of towns. According to Jerome Chanes, Lincoln's revocation of Grant's order was based primarily on "constitutional strictures against ... the federal government singling out any group for special treatment." Chanes characterizes General Order No. 11 as "unique in the history of the United States" because it was the only overtly antisemitic official action of the United States government.

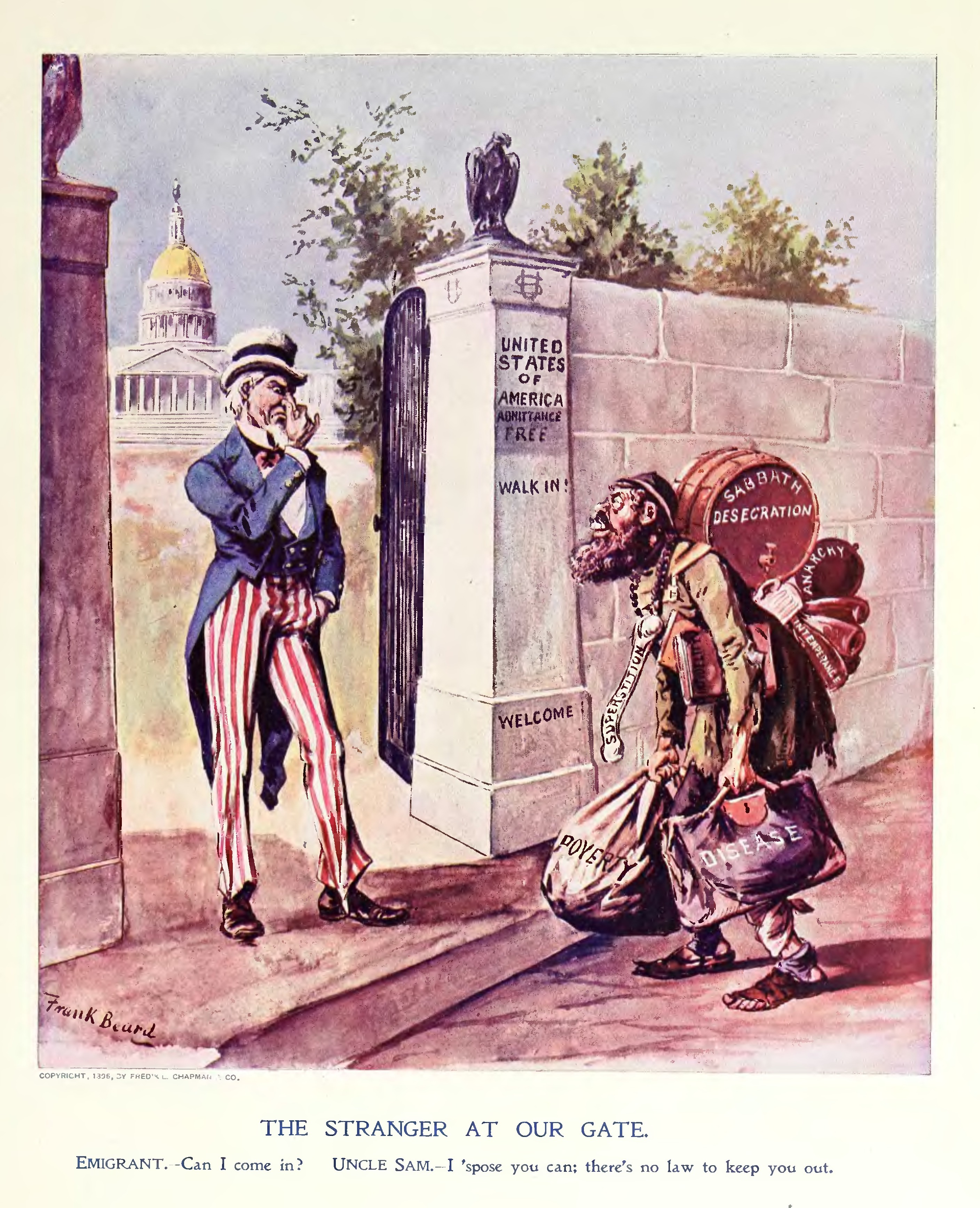

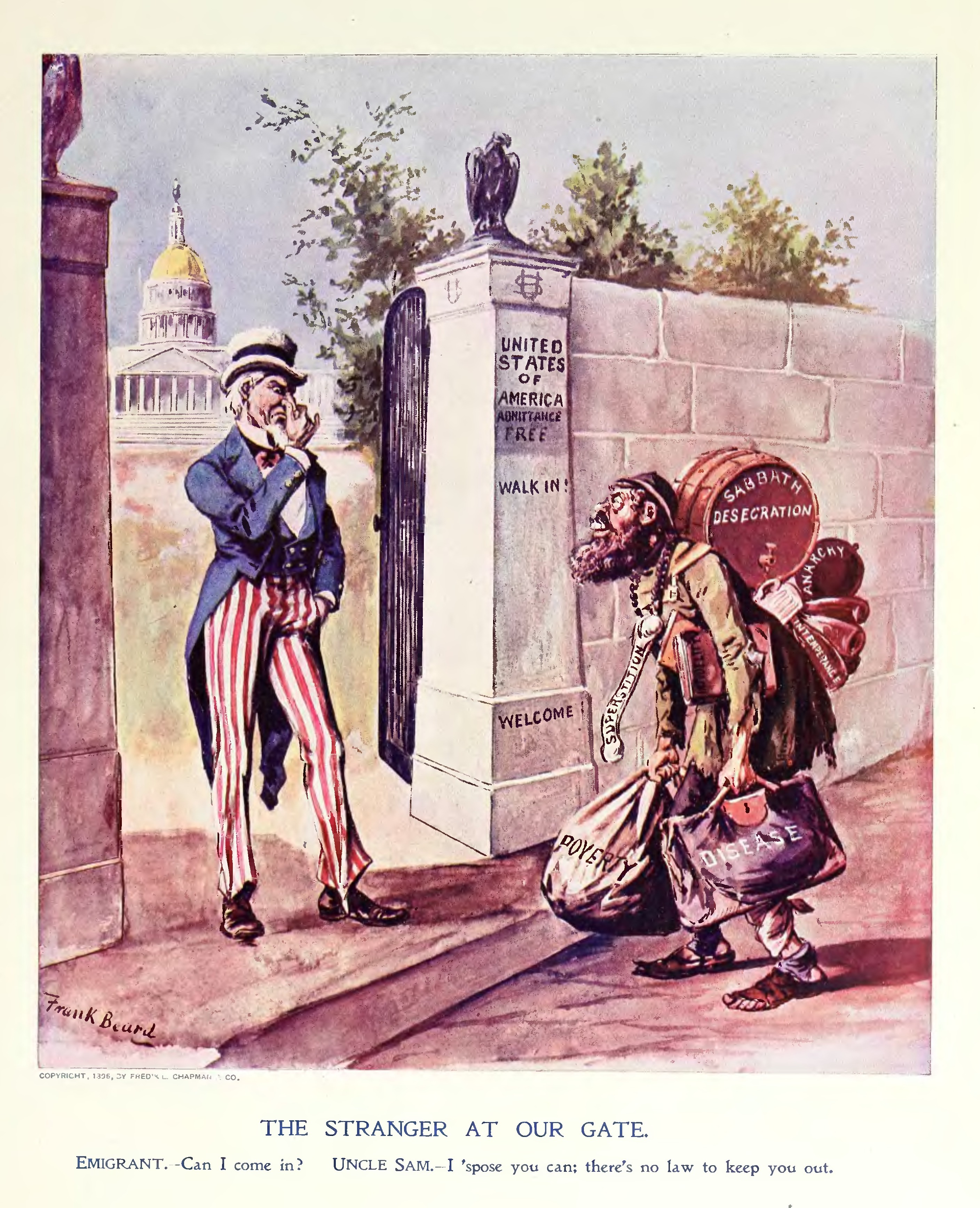

Immigration from Eastern Europe

Between 1881 and 1920, approximately 3 million

Between 1881 and 1920, approximately 3 million Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

from Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

immigrated to America, many of them fleeing pogroms and the difficult economic conditions which were widespread in much of Eastern Europe during this time. Pogroms in the Russian Empire prompted waves of Jewish immigrants after 1881. Jews, along with many Eastern and Southern European immigrants, came to work the country's growing mines and factories. Many Americans distrusted these Jewish immigrants.

Between 1900 and 1924, approximately 1.75 million Jews immigrated to America's shores, the bulk from Eastern Europe. Whereas before 1900, American Jews never amounted even to 1 percent of America's total population, by 1930 Jews formed about 3.5 percent. This dramatic increase, combined with the upward mobility of some Jews, contributed to a resurgence of antisemitism.

As the European immigration swelled the Jewish population of the United States, there developed a growing sense of Jews as different. Indeed, the United States government's Census Bureau classified Jews as their own race, Hebrews, and a 1909 effort led by Simon Wolf

Simon Wolf (October 28, 1836 – June 4, 1923) was a United States businessman, lawyer, writer, diplomat and Jewish activist.

Biography

Wolf was born in Hinzweiler, Kingdom of Bavaria. He emigrated to the United States in 1848, making his home ...

to remove Hebrew as a race through a Congressional bill failed. Jerome Chanes attributes this perception on the fact that Jews were concentrated in a small number of occupations: they were perceived as being mostly clothing manufacturers, shopkeepers and department store owners. He notes that so-called "German Jews" (who in reality came not just from Germany but from Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

and other countries as well) found themselves increasingly segregated by a widespread social antisemitism that became even more prevalent in the twentieth century and which persists in vestigial form even today.

Populism

In the middle of the 19th century, a number of German Jewish immigrants founded investment banking firms which later became mainstays of the industry. Most prominent Jewish banks in the United States were investment banks, rather than

In the middle of the 19th century, a number of German Jewish immigrants founded investment banking firms which later became mainstays of the industry. Most prominent Jewish banks in the United States were investment banks, rather than commercial bank

A commercial bank is a financial institution which accepts deposits from the public and gives loans for the purposes of consumption and investment to make profit.

It can also refer to a bank, or a division of a large bank, which deals with ...

s. Although Jews played only a minor role in the nation's commercial banking system, the prominence of Jewish investment bankers such as the Rothschild family

The Rothschild family ( , ) is a wealthy Ashkenazi Jewish family originally from Frankfurt that rose to prominence with Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), a court factor to the German Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel in the Free City of Fr ...

in Europe, and Jacob Schiff, of Kuhn, Loeb & Co. in New York City, made the claims of antisemites believable to some.

One example of allegations of Jewish control of world finances, during the 1890s, is Mary Elizabeth Lease, an American farming activist and populist from Kansas, who frequently blamed the Rothschilds and the "British bankers" as the source of farmers' ills.Levitas, pp 187-88

The Morgan Bonds scandal injected populist antisemitism into the 1896 presidential campaign. It was disclosed that President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

had sold bonds to a syndicate which included J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known ...

and the Rothschilds house, bonds which that syndicate was now selling for a profit, the Populists used it as an opportunity to uphold their view of history, and argue that Washington and Wall Street were in the hands of the international Jewish banking houses.

Another focus of antisemitic feeling was the allegation that Jews were at the center of an international conspiracy to fix the currency and thus the economy to a single gold standard.

According to Deborah Dash Moore

Deborah Dash Moore (born 1946, in New York City) is the former director of the Frankel Center for Judaic Studies and a Frederick G.L. Huetwell Professor of History and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Early li ...

, populist antisemitism used the Jew to symbolize both capitalism and urbanism so as to personify concepts that were too abstract to serve as satisfactory objects of animosity.

Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter (August 6, 1916October 24, 1970) was an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century.

Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University. Rejecting his earlier histo ...

describes populist antisemitism as "entirely verbal." He continues by asserting that, "(it) was a mode of expression, a rhetorical style, not a tactic or a program." He notes that, "(it) did not lead to exclusion laws, much less to riots or pogroms." Hofstadter still concludes, however, that the "Greenback-Populist tradition activated most of ... modern popular antisemitism in the United States."

Early 20th century

In the first half of the 20th century, Jews were discriminated against in employment, access to residential and resort areas, membership in clubs and organizations, and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrollment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. Restaurants, hotels and other establishments that barred Jews from entry were called "restricted".

In the first half of the 20th century, Jews were discriminated against in employment, access to residential and resort areas, membership in clubs and organizations, and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrollment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. Restaurants, hotels and other establishments that barred Jews from entry were called "restricted".

Lynching of Leo Frank

In 1913, a Jewish-American in Atlanta namedLeo Frank

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884August 17, 1915) was an American factory superintendent who was convicted in 1913 of the murder of a 13-year-old employee, Mary Phagan, in Atlanta, Georgia. His trial, conviction, and appeals attracted national at ...

was convicted for the rape and murder of Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old Christian girl who he employed. In the middle of the night on April 27, 1913, a 13-year-old girl named Mary Phagan was found dead by a night watchman in the basement of a pencil factory in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Leo Frank, the superintendent of the factory, was the last person to acknowledge seeing her alive earlier that day after paying her weekly wages. Detectives took Frank to the scene of the crime and the morgue to view the body. After further questioning, they concluded that he was most likely not the murderer. In the days following, rumors began to spread amongst the public that the girl had been sexually assaulted prior to her death. This sparked outrage amongst the public which called for immediate action and justice for her murder. On April 29, following Phagan's funeral, public outrage reached its pinnacle. Under immense pressure to identify a suspect, detectives arrested Leo Frank on the same day. Being a Jewish factory owner, previously from the north, Frank was an easy target for the anti-Semitic population who already distrusted northern merchants who had come to the south to work following the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. During the trial, the primary witness was Jim Conley, a black janitor who worked at the factory. Initially a suspect, Conley became the state's main witness in the trial against Frank.

Prior to the trial, Conely had given four conflicting statements regarding his role in the murder. In court, the Frank's lawyers were unable to disprove Conley's claims that he was forced by Frank to dispose of Phagan's body. The trial gathered immense attention especially from Atlantans, who gathered in large crowds around the courthouse demanding for a guilty verdict. In addition to this, much of the media coverage at the time took an anti-Semitic tone and after 25 days, Leo Frank was found guilty of murder on August 25 and sentenced to death by hanging on August 26. The verdict was met with cheers and celebration form the crowd. Following the verdict, Frank's lawyers submitted a total of five appeals to the Georgia Supreme Court as well as the U.S. Supreme Court claiming that Frank's absence on the day of the verdict and the amount of public pressure and influence swayed the jury. After this, the case was brought to Georgia governor John M. Slaton

John Marshall "Jack" Slaton (December 25, 1866 – January 11, 1955) served two non-consecutive terms as the 60th Governor of Georgia. His political career was ended in 1915 after he commuted the death penalty sentence of Atlanta factory boss ...

. Despite the public demanding for him to hold the verdict, Slaton changed Frank's verdict from death sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes fo ...

, believing that his innocence would eventually be established and he would be set free. This decision was met with immense public outrage, causing riots and even forcing Slaton to declare Martial Law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

at one point. On August 16, 1915, 25 citizens stormed a prison farm in Milledgeville where Leo Frank was being held. Taking Frank from his cell, they drove him to Marietta, the hometown of Mary Phagan, and hanged him from a tree. Leaders of the lynch mob would later gather at Stone Mountain

Stone Mountain is a quartz monzonite dome Inselberg, monadnock and the site of Stone Mountain Park, east of Atlanta, Georgia. Outside the park is the small city of Stone Mountain, Georgia. The park is the most visited tourist site in the state o ...

to revive the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

.

In response to the lynching of Leo Frank, Sigmund Livingston founded the Anti-Defamation League

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), formerly known as the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, is an international Jewish non-governmental organization based in the United States specializing in civil rights law. It was founded in late Septe ...

(ADL) under the sponsorship of B'nai B'rith

B'nai B'rith International (, from he, בְּנֵי בְּרִית, translit=b'né brit, lit=Children of the Covenant) is a Jewish service organization. B'nai B'rith states that it is committed to the security and continuity of the Jewish peo ...

. The ADL became the leading Jewish group fighting antisemitism in the United States. The lynching of Leo Frank coincided with and helped spark the revival of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

. The Klan disseminated the view that anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and Jews were subverting American values and ideals.

World War I

With theAmerican entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

, Jews were targeted by antisemites as "slackers" and "war-profiteers" responsible for many of the ills of the country. For example, a U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

manual published for war recruits stated that, "The foreign born, and especially Jews, are more apt to malinger than the native-born." When ADL representatives protested about this to President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, he ordered the manual recalled. The ADL also mounted a campaign to give Americans the facts about military and civilian contributions of Jews to the war effort.

1920s

Antisemitism in the United States reached its peak during theinterwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relative ...

. The rise of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

in the 1920s, the antisemitic works of newspapers and radio speeches in the late 1930s indicated the strength of attacks on the Jewish community.

One element in American antisemitism during the 1920s was the identification of Jews with Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, ...

where the concept of Bolshevism was used pejoratively in the country. (see article on "Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an anti-communist and antisemitic canard, which alleges that the Jews were the originators of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and that they held primary power among the Bolsheviks who led the revo ...

").

Immigration legislation enacted in the United States in 1921 and 1924 was interpreted widely as being at least partly anti-Jewish in intent because it strictly limited the immigration quotas of eastern European nations with large Jewish populations, nations from which approximately 3 million Jews had immigrated to the United States by 1920.

Discrimination in education and professions

Jews encountered resistance when they tried to move into white-collar and professional positions. Banking, insurance, public utilities, medical schools, hospitals, large law firms and faculty positions, restricted the entrance of Jews. This era of "polite" Judeophobia through social discrimination, underwent an ideological escalation in the 1930s.Restriction on immigration

In 1924, Congress passed the Johnson–Reed Act severely restricting immigration. Although the act did not specifically target Jews, the effect of the legislation was that 86% of the 165,000 permitted entries were from Northern European countries, with Germany, Britain, and Ireland having the highest quotas. The act effectively diminished the flow of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe to a trickle.The Dearborn Independent

Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

was a pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campai ...

who opposed World War I, and he believed that Jews were responsible for starting wars in order to profit from them: "International financiers are behind all war. They are what is called the international Jew: German Jews, French Jews, English Jews, American Jews. I believe that in all those countries except our own the Jewish financier is supreme ... here the Jew is a threat". Ford believed that Jews were responsible for capitalism, and in their role as financiers, they did not contribute anything of value to society.

In 1915, during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Ford blamed Jews for instigating the war, saying "I know who caused the war: German-Jewish bankers."Watts, Steven,''The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century'', Vintage, 2006, p 383 Later, in 1925, Ford said "What I oppose most is the international Jewish money power that is met in every war. That is what I oppose—a power that has no country and that can order the young men of all countries out to death'". According to author Steven Watts, Ford's antisemitism was partially due to a noble desire for world peace.

Ford became aware of ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' () or ''The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated antisemitic text purporting to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. The hoax was plagiarized from several ...

'' and believed it to be a legitimate document, and he published portions of it in his newspaper, the '' Dearborn Independent''. Also, in 1920–21 the Dearborn Independent carried a series of articles expanding on the themes of financial control by Jews, entitled:

# ''Jewish Idea in American Monetary Affairs: The remarkable story of Paul Warburg

Paul Moritz Warburg (August 10, 1868 – January 24, 1932) was a German-born American investment banker who served as the 2nd Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve from 1916 to 1918. Prior to his term as vice chairman, Warburg appointed as a member o ...

, who began work on the United States monetary system after three weeks residence in this country''

# ''Jewish Idea Molded Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after ...

: What Baruch was in War Material, Paul Warburg was in War Finances; Some Curious revelations of money and politics.''

# ''Jewish Idea of a Central Bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a centra ...

for America: The evolution of Paul M. Warburg's idea of Federal Reserve System without government management.''

# ''How Jewish International Finance Functions: The Warburg family and firm divided the world between them and did amazing things which non-Jews could not do''

# ''Jewish Power and America's Money Famine: The Warburg Federal Reserve sucks money to New York, leaving productive sections of the country in disastrous need.''

# ''The Economic Plan of International Jews: An outline of the Protocolists' monetary policy, with notes on the parallel found in Jewish financial practice.''

One of the articles, "Jewish Power and America's Money Famine", asserted that the power exercised by Jews over the nation's supply of money was insidious by helping deprive farmers and others outside the banking coterie of money when they needed it most. The article asked the question: "Where is the American gold supply? ... It may be in the United States but it does not belong to the United States" and it drew the conclusion that Jews controlled the gold supply and, hence, American money.

Another of the articles, "Jewish Idea Molded Federal Reserve System" was a reflection of Ford's suspicion of the Federal Reserve System and its proponent, Paul Warburg

Paul Moritz Warburg (August 10, 1868 – January 24, 1932) was a German-born American investment banker who served as the 2nd Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve from 1916 to 1918. Prior to his term as vice chairman, Warburg appointed as a member o ...

. Ford believed the Federal Reserve system was secretive and insidious.

These articles gave rise to claims of antisemitism against Ford, and in 1929 he signed a statement apologizing for the articles.

1930s

Antisemitic activists in the 1930s were led by FatherCharles Coughlin

Charles Edward Coughlin ( ; October 25, 1891 – October 27, 1979), commonly known as Father Coughlin, was a Canadian-American Catholic priest based in the United States near Detroit. He was the founding priest of the National Shrine of the ...

, William Dudley Pelley and Gerald L. K. Smith

Gerald Lyman Kenneth Smith (February 27, 1898 – April 15, 1976) was an American clergyman, politician and organizer known for his populist and far-right demagoguery. A leader of the populist Share Our Wealth movement during the Great Depressi ...

. Ford's attacks on Jews continued to be circulated, although the KKK was practically defunct. They promulgated various interrelated conspiracy theories, widely spreading the fear that Jews were working for the destruction or replacement of white Americans and Christianity in the U.S.

According to Gilman and Katz, antisemitism increased dramatically in the 1930s with demands being made to exclude American Jews from American social, political and economic life.

During the 1930s and 1940s, right-wing demagogues linked the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

of the 1930s, the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

, President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, and the threat of war in Europe to the machinations of an imagined international Jewish conspiracy that was both communist and capitalist. A new ideology appeared which accused "the Jews" of dominating Franklin Roosevelt's administration, of causing the Great Depression, and of dragging the United States into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

against a new Germany which deserved nothing but admiration. Roosevelt's "New Deal" was derisively referred to as the "Jew Deal".

Father Charles Coughlin

Charles Edward Coughlin ( ; October 25, 1891 – October 27, 1979), commonly known as Father Coughlin, was a Canadian-American Catholic priest based in the United States near Detroit. He was the founding priest of the National Shrine of the ...

, a radio preacher, as well as many other prominent public figures, condemned "the Jews," Gerald L. K. Smith

Gerald Lyman Kenneth Smith (February 27, 1898 – April 15, 1976) was an American clergyman, politician and organizer known for his populist and far-right demagoguery. A leader of the populist Share Our Wealth movement during the Great Depressi ...

, a Disciples of Christ

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

minister, was the founder (1937) of the Committee of One Million and publisher (beginning in 1942) of ''The Cross and the Flag

Christian Nationalist Crusade was an American antisemitic organization which operated from St. Louis, Missouri. Its founder was Gerald L. K. Smith. It sold and distributed, ''inter alia'', '' The International Jew'', and subscribed to the antise ...

'', a magazine that declared that "Christian character is the basis of all real Americanism." Other antisemitic agitators included Fritz Julius Kuhn

Fritz Julius Kuhn (May 15, 1896 – December 14, 1951) was a German Nazi activist who served as elected leader of the German American Bund before World War II. He became a naturalized United States citizen in 1934, but his citizenship was can ...

of the German-American Bund

The German American Bund, or the German American Federation (german: Amerikadeutscher Bund; Amerikadeutscher Volksbund, AV), was a German-American Nazi organization which was established in 1936 as a successor to the Friends of New Germany (FoN ...

, William Dudley Pelley, and the Rev. Gerald Winrod.

In the end, promoters of antisemitism achieved no more than a passing popularity as the threat of Nazi Germany became more and more evident to the American electorate. Steven Roth asserts that there was never a real possibility of a "Jewish question" appearing on the American political agenda as it did in Europe; according to Roth, the resistance to political antisemitism in the United States was due to the heterogeneity of the American political structure.

American attitudes towards Jews

In a 1938 poll, approximately 60 percent of the respondents held a low opinion of Jews, labeling them "greedy," "dishonest," and "pushy." 41 percent of respondents agreed that Jews had "too much power in the United States," and this figure rose to 58 percent by 1945. Several surveys taken from 1940 to 1946 found that Jews were seen as a greater threat to the welfare of the United States than any other national, religious, or racial group.

In a 1938 poll, approximately 60 percent of the respondents held a low opinion of Jews, labeling them "greedy," "dishonest," and "pushy." 41 percent of respondents agreed that Jews had "too much power in the United States," and this figure rose to 58 percent by 1945. Several surveys taken from 1940 to 1946 found that Jews were seen as a greater threat to the welfare of the United States than any other national, religious, or racial group.

Charles Coughlin

The main spokesman for antisemitic sentiment was Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest whose weekly radio program drew between 5 and 12 million listeners in the late 1930s. Coughlin's newspaper, ''Social Justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals ...

'', reached a circulation of 800,000 at its peak in 1937.

After the 1936 election, Coughlin increasingly expressed sympathy for the fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

policies of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until Fall of the Fascist re ...

, as an antidote to Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, ...

. His weekly radio broadcasts became suffused with themes regarded as overtly antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

. He blamed the Depression on an international conspiracy of Jewish bankers, and also claimed that Jewish bankers were behind the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

.

Coughlin began publication of a newspaper, ''Social Justice'', during this period, in which he printed antisemitic polemics such as ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' () or ''The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated antisemitic text purporting to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. The hoax was plagiarized from several ...

''. Like Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the '' Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to ...

, Coughlin claimed that Marxist atheism in Europe was a Jewish plot. The 5 December 1938 issue of ''Social Justice'' included an article by Coughlin which closely resembled a speech made by Goebbels on 13 September 1935 attacking Jews, atheists and communists, with some sections being copied verbatim by Coughlin from an English translation of the Goebbels speech.

On November 20, 1938, two weeks after Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

, when Jews across Germany were attacked and killed, and Jewish businesses, homes and synagogues burned, Coughlin blamed the Jewish victims, saying that "Jewish persecution only followed after Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ� ...

first were persecuted." After this speech, and as his programs became more antisemitic, some radio stations, including those in New York and Chicago, began refusing to air his speeches without pre-approved scripts; in New York, his programs were cancelled by WINS and WMCA WMCA may refer to:

*WMCA (AM), a radio station operating in New York City

* West Midlands Combined Authority, the combined authority of the West Midlands metropolitan county in the United Kingdom

*Wikimedia Canada

The Wikimedia Foundation, ...

, leaving Coughlin to broadcasting on the Newark part-time station WHBI. This made Coughlin a hero in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, where papers ran headlines like: "America is Not Allowed to Hear the Truth."

On December 18, 1938, two thousand of Coughlin's followers marched in New York protesting potential asylum law changes that would allow more Jews (including refugees from Hitler's persecution) into the US, chanting, "Send Jews back where they came from in leaky boats!" and "Wait until Hitler comes over here!" The protests continued for several months. Donald Warren, using information from the FBI and German government archives, has also argued that Coughlin received indirect funding from Nazi Germany during this period.

After 1936, Coughlin began supporting an organization called the Christian Front, which claimed him as an inspiration. In January, 1940, the Christian Front was shut down when the FBI discovered the group was arming itself and "planning to murder Jews, communists, and 'a dozen Congressmen'" and eventually establish, in J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

's words, "a dictatorship, similar to the Hitler dictatorship in Germany." Coughlin publicly stated, after the plot was discovered, that he still did not "disassociate himself from the movement," and though he was never linked directly to the plot, his reputation suffered a fatal decline.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war in December 1941, the anti-interventionist movement (such as the America First Committee) sputtered out, and isolationists like Coughlin were seen as being sympathetic to the enemy. In 1942, the new bishop of Detroit ordered Coughlin to stop his controversial political activities and confine himself to his duties as a parish priest.

Pelley and Winrod

William Dudley Pelley founded (1933) the antisemitic Silvershirt Legion of America; nine years later he was convicted ofsedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, esta ...

. And Gerald Winrod, leader of Defenders of the Christian Faith, was eventually indicted for conspiracy to cause insubordination in the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is ...

during World War II.

America First Committee

The avant-garde of the new non-interventionism was theAmerica First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was the foremost United States isolationist pressure group against American entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supp ...

, which included the aviation hero Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

and many prominent Americans. The America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was the foremost United States isolationist pressure group against American entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supp ...

opposed any involvement in the war in Europe.

Officially, America First avoided any appearance of antisemitism and voted to drop Henry Ford as a member for his overt antisemitism.

In a speech delivered on September 11, 1941, at an America First rally, Lindbergh claimed that three groups had been "pressing this country toward war": the Roosevelt Administration, the British, and the Jews—and complained about what he insisted was the Jews' "large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government."

In an expurgated portion of his published diaries Lindbergh wrote: "We must limit to a reasonable amount the Jewish influence. ... Whenever the Jewish percentage of total population becomes too high, a reaction seems to invariably occur. It is too bad because a few Jews of the right type are, I believe, an asset to any country."

German American Bund

The German American Bund held parades inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in the late 1930s which featured Nazi uniforms and flags

A flag is a piece of textile, fabric (most often rectangular or quadrilateral) with a distinctive design and colours. It is used as a symbol, a signalling device, or for decoration. The term ''flag'' is also used to refer to the graphic desi ...

featuring swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. I ...

s alongside American flags

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the ''American flag'' or the ''U.S. flag'', consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the c ...

. Some 20,000 people heard Bund leader Fritz Julius Kuhn

Fritz Julius Kuhn (May 15, 1896 – December 14, 1951) was a German Nazi activist who served as elected leader of the German American Bund before World War II. He became a naturalized United States citizen in 1934, but his citizenship was can ...

criticize President Franklin D. Roosevelt by repeatedly referring to him as "Frank D. Rosenfeld", calling his New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

the "Jew Deal", and espousing his belief in the existence of a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

-Jewish conspiracy in America.

Refugees from Nazi Germany

In the years before and during World War II theUnited States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

, the Roosevelt Administration, and public opinion expressed concern about the fate of Jews in Europe but consistently refused to permit immigration of Jewish refugees.

In a report issued by the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

, Undersecretary of State Stuart Eizenstat noted that the United States accepted only 21,000 refugees from Europe and did not significantly raise or even fill its restrictive quotas, accepting far fewer Jews per capita than many of the neutral European countries and fewer in absolute terms than Switzerland.

According to David Wyman, "The United States and its Allies were willing to attempt almost nothing to save the Jews." There is some debate as to whether U.S. policies were generally targeted against all immigrants or specifically against Jews in particular. Wyman characterized FDR advisor and State Department official in charge of immigration policy Breckinridge Long

Samuel Miller Breckinridge Long (May 16, 1881 – September 26, 1958) was an American diplomat and politician. He served in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He is infamous among Holocaust historians for makin ...

as a nativist, more anti-immigrant than just antisemitic.

SS St. Louis

The SS ''St. Louis'' sailed out ofHamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

into the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

in May 1939 carrying one non-Jewish and 936 (mainly German) Jewish refugees seeking asylum

Asylum may refer to:

Types of asylum

* Asylum (antiquity), places of refuge in ancient Greece and Rome

* Benevolent Asylum, a 19th-century Australian institution for housing the destitute

* Cities of Refuge, places of refuge in ancient Judea

...

from Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

persecution just before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. On 4 June 1939, having failed to obtain permission to disembark passengers in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, the ''St. Louis'' was also refused permission to unload on orders of President Roosevelt as the ship waited in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexic ...

between Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

and Cuba.Rosen, p. 563.

The Holocaust

During theHolocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, antisemitism was a factor that limited American Jewish action during the war, and put American Jews in a difficult position. It is clear that antisemitism was a prevalent attitude in the US, which was especially convenient for America during the Holocaust. In America, antisemitism, which reached high levels in the late 1930s, continued to rise in the 1940s. During the years before Pearl Harbor, over a hundred antisemitic organizations were responsible for pumping hate propaganda to the American public. Furthermore, especially in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, young gangs vandalized Jewish cemeteries

A Jewish cemetery ( he, בית עלמין ''beit almin'' or ''beit kvarot'') is a cemetery where Jews are buried in keeping with Jewish tradition. Cemeteries are referred to in several different ways in Hebrew, including ''beit kevarot'' ...

and synagogues, and attacks on Jewish youngsters were common. Swastikas and anti-Jewish slogans, as well as antisemitic literature, were spread. In 1944, a public opinion poll showed that a quarter of Americans still regarded Jews as a "menace." Antisemitism in the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

played a large role in Washington's hesitant response to the plight of European Jews persecuted by Nazis.

In a 1943 speech on the floor of Congress quoted in both ''The Jewish News'' of Detroit and the antisemitic magazine ''The Defender'' of Wichita Mississippi Representative John E. Rankin

John Elliott Rankin (March 29, 1882 – November 26, 1960) was a Democratic politician from Mississippi who served sixteen terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1921 to 1953. He was co-author of the bill for the Tennessee Valley A ...

espoused a conspiracy of "alien-minded" Communist Jews arranging for white women to be raped by African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

men:

US Government policy

Josiah DuBois wrote the famous "Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews," which Treasury SecretaryHenry Morgenthau, Jr.

Henry Morgenthau Jr. (; May 11, 1891February 6, 1967) was the United States Secretary of the Treasury during most of the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. He played a major role in designing and financing the New Deal. After 1937, while s ...

, used to convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt to establish the War Refugee Board

The War Refugee Board, established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in January 1944, was a U.S. executive agency to aid civilian victims of the Axis powers. The Board was, in the words of historian Rebecca Erbelding, "the only time in American h ...

in 1944. Randolph Paul was also a principal sponsor of this report, the first contemporaneous Government paper attacking America's dormant complicity in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

.

Entitled "Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews", the document was an indictment of the U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other n ...

's diplomatic, military, and immigration policies. Among other things, the Report narrated the State Department's inaction and in some instances active opposition to the release of funds for the Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe, and condemned immigration policies that closed American doors to Jewish refugees from countries then engaged in their systematic slaughter.

The catalyst for the Report was an incident involving 70,000 Romanian Jews

The history of the Jews in Romania concerns the Jews both of Romania and of Romanian origins, from their first mention on what is present-day Romanian territory. Minimal until the 18th century, the size of the Jewish population increased after ...

whose evacuation from the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

could have been procured with a $170,000 bribe. The Foreign Funds Control unit of the Treasury, which was within Paul's jurisdiction, authorized the payment of the funds, the release of which both the President and Secretary of State Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

supported. From mid-July 1943, when the proposal was made and Treasury approved, through December 1943, a combination of the State Department's bureaucracy and the British Ministry of Economic Warfare interposed various obstacles. The Report was the product of frustration over that event.

On January 16, 1944, Morgenthau and Paul personally delivered the paper to President Roosevelt, warning him that Congress would act if he did not. The result was Executive Order 9417, creating the War Refugee Board

The War Refugee Board, established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in January 1944, was a U.S. executive agency to aid civilian victims of the Axis powers. The Board was, in the words of historian Rebecca Erbelding, "the only time in American h ...

composed of the Secretaries of State, Treasury and War. Issued on January 22, 1944, the Executive Order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

declared that "it is the policy of this Government to take all measures within its power to rescue the victims of enemy oppression who are in imminent danger of death and otherwise to afford such victims all possible relief and assistance consistent with the successful prosecution of the war."

It has been estimated that 190,000–200,000 Jews could have been saved during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

had it not been for bureaucratic obstacles to immigration deliberately created by Breckinridge Long

Samuel Miller Breckinridge Long (May 16, 1881 – September 26, 1958) was an American diplomat and politician. He served in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He is infamous among Holocaust historians for makin ...

and others."Breckinridge Long (1881-1958)"Public Broadcasting Service

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educa ...

(PBS), accessed March 12, 2006.

1950s

Liberty Lobby

Liberty Lobby

Liberty Lobby was a far-right think tank and lobby group founded in 1958 by Willis Carto. Carto was known for his promotion of antisemitic conspiracy theories, white nationalism, and Holocaust denial.

The organization produced a daily five-mi ...

was a political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studi ...

advocacy organization which was founded in 1955 by Willis Carto in 1955. Liberty Lobby was founded as a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

political organization and was known to hold strongly antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

views and to be a devotee of the writings of Francis Parker Yockey, who was one of a handful of post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

writers who revered Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

.

Late twentieth century

TheNixon White House tapes

The Nixon White House tapes are audio recordings of conversations between U.S. President Richard Nixon and Nixon administration officials, Nixon family members, and White House staff, produced between 1971 and 1973.

In February 1971, a sound-a ...

released during the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

reveal that President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

made numerous anti-Semitic remarks during his presidency. For example he repeatedly referred to National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

as "Jew boy," and blamed the anti-Vietnam War movement

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War (before) or anti-Vietnam War movement (present) began with demonstrations in 1965 against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War and grew into a broad social move ...

and leaking of the Pentagon Papers

The ''Pentagon Papers'', officially titled ''Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force'', is a United States Department of Defense history of the United States' political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 ...

on Jews.

Antisemitic violence in this era includes the 1977 shootings at Brith Sholom Kneseth Israel synagogue in St. Louis, Missouri, the 1984 murder of Alan Berg

Alan Harrison Berg (January 18, 1934 – June 18, 1984) was an American talk radio show host in Denver, Colorado. Born to a Jewish family, he had outspoken atheistic and liberal views and a confrontational interview style. Berg was murdered b ...

, the 1985 Goldmark Murders, and the 1986 Murder of Neal Rosenblum.

NSPA march in Skokie

Seeking a venue, In 1977 and 1978, members of theNational Socialist Party of America

The National Socialist Party of America (NSPA) was a Chicago-based organization founded in 1970 by Frank Collin shortly after he left the National Socialist White People's Party. The NSWPP had been the American Nazi Party until shortly after th ...

(NSPA) chose Skokie. Because of the large number of Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

survivors in Skokie, it was believed that the march would be disruptive, and the village refused to allow it. They passed three new ordinances requiring damage deposits, banning marches in military uniforms and limiting the distribution of hate speech literature. The American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

interceded on behalf of the NSPA in ''National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie

''National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie'', 432 U.S. 43 (1977), arising out of what is sometimes referred to as the Skokie Affair, was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court dealing with freedom of speech and freedom of assem ...

'' seeking a parade permit and to invalidate the three new Skokie ordinances.

However, due to a subsequent lifting of the Marquette Park ban, the NSPA ultimately held their rally in Chicago on July 7, 1978, instead of in Skokie.

African-American community

In 1984, civil rights leader Jessie Jackson speaking toWashington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large na ...

reporter Milton Coleman referred to Jews as "Hymies" and New York City