History of aluminium on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of aluminium was shaped by the usage of its compound

The history of aluminium was shaped by the usage of its compound

At the start of the

At the start of the

Aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It ha ...

(or aluminum) metal is very rare in native form, and the process to refine it from ores is complex, so for most of human history it was unknown. However, the compound alum

An alum () is a type of chemical compound, usually a hydrated double sulfate salt of aluminium with the general formula , where is a monovalent cation such as potassium or ammonium. By itself, "alum" often refers to potassium alum, with the ...

has been known since the 5th century BCE and was used extensively by the ancients for dyeing. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, its use for dyeing made it a commodity

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a co ...

of international commerce. Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

scientists believed that alum was a salt of a new earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

; during the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, it was established that this earth, alumina, was an oxide of a new metal. Discovery of this metal was announced in 1825 by Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted ( , ; often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 17779 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricit ...

, whose work was extended by German chemist Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler () FRS(For) Hon FRSE (31 July 180023 September 1882) was a German chemist known for his work in inorganic chemistry, being the first to isolate the chemical elements beryllium and yttrium in pure metallic form. He was the fi ...

.

Aluminium was difficult to refine and thus uncommon in actual usage. Soon after its discovery, the price of aluminium exceeded that of gold. It was reduced only after the initiation of the first industrial production by French chemist Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville

Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville (11 March 18181 July 1881) was a French chemist.

He was born in the island of St Thomas in the Danish West Indies, where his father was French consul. Together with his elder brother Charles he was educate ...

in 1856. In 1878, metallurgist James Fern Webster was producing 100 pounds of pure aluminium every week at his Solihull

Solihull (, or ) is a market town and the administrative centre of the wider Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in West Midlands County, England. The town had a population of 126,577 at the 2021 Census. Solihull is situated on the River Blyth ...

Lodge factory in Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avo ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, using a chemical process. In 1884, he established a trading title, Webster's Patent Aluminium Crown Metal Company Ltd. Aluminium became much more available to the public with the Hall–Héroult process

The Hall–Héroult process is the major industrial process for smelting aluminium. It involves dissolving aluminium oxide (alumina) (obtained most often from bauxite, aluminium's chief ore, through the Bayer process) in molten cryolite, and el ...

developed independently by French engineer Paul Héroult

Paul (Louis-Toussaint) Héroult (10 April 1863 – 9 May 1914) was a French scientist. He was the inventor of the aluminium electrolysis and developed the first successful commercial electric arc furnace. He lived in Thury-Harcourt, Normandy. ...

and American engineer Charles Martin Hall

Charles Martin Hall (December 6, 1863 – December 27, 1914) was an American inventor, businessman, and chemist. He is best known for his invention in 1886 of an inexpensive method for producing aluminum, which became the first metal to atta ...

in 1886, and the Bayer process

The Bayer process is the principal industrial means of refining bauxite to produce alumina (aluminium oxide) and was developed by Carl Josef Bayer. Bauxite, the most important ore of aluminium, contains only 30–60% aluminium oxide (Al2O3), th ...

developed by Austrian chemist Carl Joseph Bayer in 1889. These processes have been used for aluminium production up to the present.

The introduction of these methods for the mass production of aluminium led to extensive use of the light, corrosion-resistant metal in industry and everyday life. Aluminium began to be used in engineering and construction. In World Wars I and II, aluminium was a crucial strategic resource

In economics, factors of production, resources, or inputs are what is used in the production process to produce output—that is, goods and services. The utilized amounts of the various inputs determine the quantity of output according to the rel ...

for aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes airplane, fixed-wing and helicopter, rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as aerostat, lighter- ...

. World production of the metal grew from 6,800 metric tons in 1900 to 2,810,000 metric tons in 1954, when aluminium became the most produced non-ferrous metal

In metallurgy, non-ferrous metals are metals or alloys that do not contain iron ( allotropes of iron, ferrite, and so on) in appreciable amounts.

Generally more costly than ferrous metals, non-ferrous metals are used because of desirable prop ...

, surpassing copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

.

In the second half of the 20th century, aluminium gained usage in transportation and packaging. Aluminium production became a source of concern due to its effect on the environment, and aluminium recycling gained ground. The metal became an exchange commodity in the 1970s. Production began to shift from developed countries

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastruct ...

to developing ones; by 2010, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

had accumulated an especially large share in both production and consumption of aluminium. World production continued to rise, reaching 58,500,000 metric tons in 2015. Aluminium production exceeds those of all other non-ferrous metals combined.

Early history

The history of aluminium was shaped by the usage of its compound

The history of aluminium was shaped by the usage of its compound alum

An alum () is a type of chemical compound, usually a hydrated double sulfate salt of aluminium with the general formula , where is a monovalent cation such as potassium or ammonium. By itself, "alum" often refers to potassium alum, with the ...

. The first written record of alum was in the 5th century BCE by Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

historian Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

. The ancients used it as a dyeing mordant

A mordant or dye fixative is a substance used to set (i.e. bind) dyes on fabrics by forming a coordination complex with the dye, which then attaches to the fabric (or tissue). It may be used for dyeing fabrics or for intensifying stains in ...

, in medicine, in chemical milling, and as a fire-resistant coating for wood to protect fortresses from enemy arson. Aluminium metal was unknown. Roman writer Petronius

Gaius Petronius Arbiter"Gaius Petronius Arbiter"

Satyricon The ''Satyricon'', ''Satyricon'' ''liber'' (''The Book of Satyrlike Adventures''), or ''Satyrica'', is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius, though the manuscript tradition identifies the author as Titus Petr ...

'' that an unusual glass had been presented to the emperor: after it was thrown on the pavement, it did not break but only deformed. It was returned to its former shape using a hammer. After learning from the inventor that nobody else knew how to produce this material, the emperor had the inventor executed so that it did not diminish the price of gold. Variations of this story were mentioned briefly in ''Natural History'' by Roman historian Satyricon The ''Satyricon'', ''Satyricon'' ''liber'' (''The Book of Satyrlike Adventures''), or ''Satyrica'', is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius, though the manuscript tradition identifies the author as Titus Petr ...

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

(who noted the story had "been current through frequent repetition rather than authentic") and ''Roman History'' by Roman historian Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

. Some sources suggest this glass could be aluminium. It is possible aluminium-containing alloys were produced in China during the reign of the first Jin dynasty (266–420).

After the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

, alum was a commodity

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a co ...

of international commerce; it was indispensable in the European fabric industry. Small alum mines were worked in Catholic Europe but most alum came from the Middle East. Alum continued to be traded through the Mediterranean Sea until the mid-15th century, when the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

greatly increased export taxes. In a few years, alum was discovered in great abundance in Italy. Pope Pius II forbade all imports from the east, using the profits from the alum trade to start a war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

with the Ottomans. This newly found alum long played an important role in European pharmacy

Pharmacy is the science and practice of discovering, producing, preparing, dispensing, reviewing and monitoring medications, aiming to ensure the safe, effective, and affordable use of medication, medicines. It is a miscellaneous science as it ...

, but the high prices set by the papal government eventually made other states start their own production; large-scale alum mining came to other regions of Europe in the 16th century.

Establishing the nature of alum

At the start of the

At the start of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, the nature of alum remained unknown. Around 1530, Swiss physician Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

He ...

recognized alum as separate from ''vitriol

Vitriol is the general chemical name encompassing a class of chemical compound comprising sulfates of certain metalsoriginally, iron or copper. Those mineral substances were distinguished by their color, such as green vitriol for hydrated iron( ...

e'' (sulfates) and suggested it was a salt of an earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

. In 1595, German doctor and chemist Andreas Libavius demonstrated that alum and green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by a combin ...

and blue

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model. It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The eye perceives blue when ...

''vitriole'' were formed by the same acid but different earths; for the undiscovered earth that formed alum, he proposed the name "alumina". German chemist Georg Ernst Stahl stated that the unknown base of alum was akin to lime or chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. C ...

in 1702; this mistaken view was shared by many scientists for half a century. In 1722, German chemist Friedrich Hoffmann suggested that the base of alum was a distinct earth. In 1728, French chemist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories ...

claimed alum was formed by an unknown earth and sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular fo ...

; he mistakenly believed burning that earth yielded silica. (Geoffroy's mistake was corrected only in 1785 by German chemist and pharmacist Johann Christian Wiegleb

Johann Christian Wiegleb (December 21, 1732 – January 16, 1800) was a notable German apothecary and early innovator of chemistry as a science.

Life

Wiegleb, the son of a lawyer, was schooled in Langensalza.Wolfgang-Hagen Heim, Holm-Dietmar Sch ...

. He determined that earth of alum could not be synthesized from silica and alkalis, contrary to contemporary belief.) French chemist Jean Gello proved the earth in clay and the earth resulting from the reaction of an alkali on alum were identical in 1739. German chemist Johann Heinrich Pott showed the precipitate obtained from pouring an alkali into a solution of alum was different from lime and chalk in 1746.

German chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf

Andreas Sigismund Marggraf (; 3 March 1709 – 7 August 1782) was a German chemist from Berlin, then capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, and a pioneer of analytical chemistry. He isolated zinc in 1746 by heating calamine and carbon. Tho ...

synthesized the earth of alum by boiling clay in sulfuric acid and adding potash

Potash () includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water- soluble form.

in 1754. He realized that adding soda, potash, or an alkali to a solution of the new earth in sulfuric acid yielded alum. He described the earth as alkaline, as he had discovered it dissolved in acids when dried. Marggraf also described salts of this earth: chloride

The chloride ion is the anion (negatively charged ion) Cl−. It is formed when the element chlorine (a halogen) gains an electron or when a compound such as hydrogen chloride is dissolved in water or other polar solvents. Chloride s ...

, nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insolu ...

and acetate

An acetate is a salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. alkaline, earthy, metallic, nonmetallic or radical base). "Acetate" also describes the conjugate base or ion (specifically, the negatively charged ion called ...

. In 1758, French chemist Pierre Macquer

Pierre-Joseph Macquer (9 October 1718 – 15 February 1784) was an influential French chemist.

He is known for his ''Dictionnaire de chymie'' (1766). He was also involved in practical applications, to medicine and industry, such as the French de ...

wrote that alumina resembled a metallic earth. In 1760, French chemist Théodore Baron d'Hénouville expressed his confidence that alumina was a metallic earth.

In 1767, Swedish chemist Torbern Bergman

Torbern Olaf (Olof) Bergman (''KVO'') (20 March 17358 July 1784) was a Swedish chemist and mineralogist noted for his 1775 ''Dissertation on Elective Attractions'', containing the largest chemical affinity tables ever published. Bergman was the ...

synthesized alum by boiling alunite

Alunite is a hydroxylated aluminium potassium sulfate mineral, formula K Al3( S O4)2(O H)6. It was first observed in the 15th century at Tolfa, near Rome, where it was mined for the manufacture of alum. First called ''aluminilite'' by J.C. D ...

in sulfuric acid and adding potash to the solution. He also synthesized alum as a reaction product between sulfates of potassium and earth of alum, demonstrating that alum was a double salt. Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified molybdenum, tungsten, barium, hydr ...

demonstrated that both alum and silica originated from clay and alum did not contain silicon in 1776. Writing in 1782, French chemist Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS ( suggested the formula AlO3 for alumina in 1815. The correct formula, Al2O3, was established by German chemist

In 1760, Baron de Hénouville unsuccessfully attempted to reduce alumina to its metal. He claimed he had tried every method of reduction known at the time, though his methods were unpublished. It is probable he mixed alum with carbon or some organic substance, with salt or soda for flux, and heated it in a charcoal fire. Austrian chemists Anton Leopold Ruprecht and Matteo Tondi repeated Baron's experiments in 1790, significantly increasing the temperatures. They found small metallic particles they believed were the sought-after metal; but later experiments by other chemists showed these were

In 1760, Baron de Hénouville unsuccessfully attempted to reduce alumina to its metal. He claimed he had tried every method of reduction known at the time, though his methods were unpublished. It is probable he mixed alum with carbon or some organic substance, with salt or soda for flux, and heated it in a charcoal fire. Austrian chemists Anton Leopold Ruprecht and Matteo Tondi repeated Baron's experiments in 1790, significantly increasing the temperatures. They found small metallic particles they believed were the sought-after metal; but later experiments by other chemists showed these were  Berzelius tried isolating the metal in 1825 by carefully washing the potassium analog of the base salt in

Berzelius tried isolating the metal in 1825 by carefully washing the potassium analog of the base salt in

Since Wöhler's method could not yield large amounts of aluminium, the metal remained uncommon; its

Since Wöhler's method could not yield large amounts of aluminium, the metal remained uncommon; its  Manufacturers did not wish to divert resources from producing well-known (and marketable) metals, such as iron and

Manufacturers did not wish to divert resources from producing well-known (and marketable) metals, such as iron and  Some chemists, including Deville, sought to use cryolite as the source ore, but with little success. British engineer William Gerhard set up a plant with cryolite as the primary raw material in Battersea, London, in 1856, but technical and financial difficulties forced the closure of the plant in three years. British ironmaster

Some chemists, including Deville, sought to use cryolite as the source ore, but with little success. British engineer William Gerhard set up a plant with cryolite as the primary raw material in Battersea, London, in 1856, but technical and financial difficulties forced the closure of the plant in three years. British ironmaster

CNRS ( suggested the formula AlO3 for alumina in 1815. The correct formula, Al2O3, was established by German chemist

Eilhard Mitscherlich

Eilhard Mitscherlich (; 7 January 179428 August 1863) was a German chemist, who is perhaps best remembered today for his discovery of the phenomenon of crystallographic isomorphism in 1819.

Early life and work

Mitscherlich was born at Neuende ...

in 1821; this helped Berzelius determine the correct atomic weight

Relative atomic mass (symbol: ''A''; sometimes abbreviated RAM or r.a.m.), also known by the deprecated synonym atomic weight, is a dimensionless physical quantity defined as the ratio of the average mass of atoms of a chemical element in a giv ...

of the metal, 27.

Isolation of metal

In 1760, Baron de Hénouville unsuccessfully attempted to reduce alumina to its metal. He claimed he had tried every method of reduction known at the time, though his methods were unpublished. It is probable he mixed alum with carbon or some organic substance, with salt or soda for flux, and heated it in a charcoal fire. Austrian chemists Anton Leopold Ruprecht and Matteo Tondi repeated Baron's experiments in 1790, significantly increasing the temperatures. They found small metallic particles they believed were the sought-after metal; but later experiments by other chemists showed these were

In 1760, Baron de Hénouville unsuccessfully attempted to reduce alumina to its metal. He claimed he had tried every method of reduction known at the time, though his methods were unpublished. It is probable he mixed alum with carbon or some organic substance, with salt or soda for flux, and heated it in a charcoal fire. Austrian chemists Anton Leopold Ruprecht and Matteo Tondi repeated Baron's experiments in 1790, significantly increasing the temperatures. They found small metallic particles they believed were the sought-after metal; but later experiments by other chemists showed these were iron phosphide

Iron phosphide is a chemical compound of iron and phosphorus, with a formula of FeP. Its physical appearance is grey, hexagonal needles.

Manufacturing of iron phosphide takes place at elevated temperatures, where the elements combine directly. I ...

from impurities in the charcoal and bone ash. German chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth

Martin Heinrich Klaproth (1 December 1743 – 1 January 1817) was a German chemist. He trained and worked for much of his life as an apothecary, moving in later life to the university. His shop became the second-largest apothecary in Berlin, and ...

commented in an aftermath, "if there exists an earth which has been put in conditions where its metallic nature should be disclosed, if it had such, an earth exposed to experiments suitable for reducing it, tested in the hottest fires by all sorts of methods, on a large as well as on a small scale, that earth is certainly alumina, yet no one has yet perceived its metallization." Lavoisier in 1794 and French chemist Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau in 1795 melted alumina to a white enamel in a charcoal fire fed by pure oxygen but found no metal. American chemist Robert Hare melted alumina with an oxyhydrogen blowpipe in 1802, also obtaining the enamel, but still found no metal.

In 1807, British chemist Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for ...

successfully electrolyzed alumina with alkaline batteries, but the resulting alloy contained potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin '' kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmos ...

and sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

, and Davy had no means to separate the desired metal from these. He then heated alumina with potassium, forming potassium oxide

Potassium oxide ( K O) is an ionic compound of potassium and oxygen. It is a base. This pale yellow solid is the simplest oxide of potassium. It is a highly reactive compound that is rarely encountered. Some industrial materials, such as fertili ...

but was unable to produce the sought-after metal. In 1808, Davy set up a different experiment on electrolysis of alumina, establishing that alumina decomposed in the electric arc but formed metal alloyed with iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

; he was unable to separate the two. Finally, he tried yet another electrolysis experiment, seeking to collect the metal on iron, but was again unable to separate the coveted metal from it. Davy suggested the metal be named ''alumium'' in 1808 and ''aluminum'' in 1812, thus producing the modern name. Other scientists used the spelling ''aluminium''; the former spelling regained usage in the United States in the following decades.

American chemist Benjamin Silliman repeated Hare's experiment in 1813 and obtained small granules of the sought-after metal, which almost immediately burned.

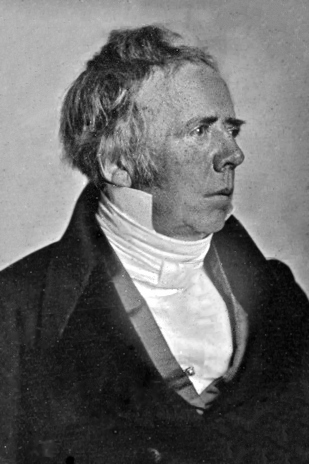

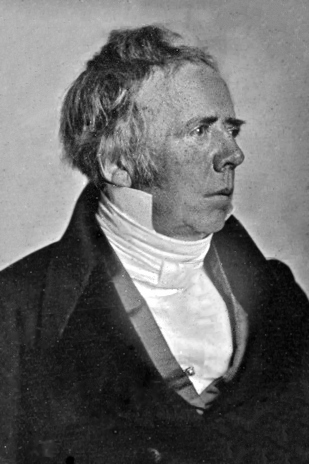

In 1824, Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted ( , ; often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 17779 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricit ...

attempted to produce the metal. He reacted anhydrous

A substance is anhydrous if it contains no water. Many processes in chemistry can be impeded by the presence of water; therefore, it is important that water-free reagents and techniques are used. In practice, however, it is very difficult to achi ...

aluminium chloride with potassium amalgam

Amalgam most commonly refers to:

* Amalgam (chemistry), mercury alloy

* Amalgam (dentistry), material of silver tooth fillings

** Bonded amalgam, used in dentistry

Amalgam may also refer to:

* Amalgam Comics, a publisher

* Amalgam Digital, an in ...

, yielding a lump of metal that looked similar to tin. He presented his results and demonstrated a sample of the new metal in 1825. In 1826, he wrote, "aluminium has a metallic luster and somewhat grayish color and breaks down water very slowly"; this suggests he had obtained an aluminium–potassium alloy, rather than pure aluminium. Ørsted placed little importance on his discovery. He did not notify either Davy or Berzelius, both of whom he knew, and published his work in a Danish magazine unknown to the European public. As a result, he is often not credited as the discoverer of the element; some earlier sources claimed Ørsted had not isolated aluminium.

Berzelius tried isolating the metal in 1825 by carefully washing the potassium analog of the base salt in

Berzelius tried isolating the metal in 1825 by carefully washing the potassium analog of the base salt in cryolite

Cryolite ( Na3 Al F6, sodium hexafluoroaluminate) is an uncommon mineral identified with the once-large deposit at Ivittuut on the west coast of Greenland, mined commercially until 1987.

History

Cryolite was first described in 1798 by Danish vete ...

in a crucible. Prior to the experiment, he had correctly identified the formula of this salt as K3AlF6. He found no metal, but his experiment came very close to succeeding and was successfully reproduced many times later. Berzelius's mistake was in using an excess of potassium, which made the solution too alkaline and dissolved all the newly formed aluminium.

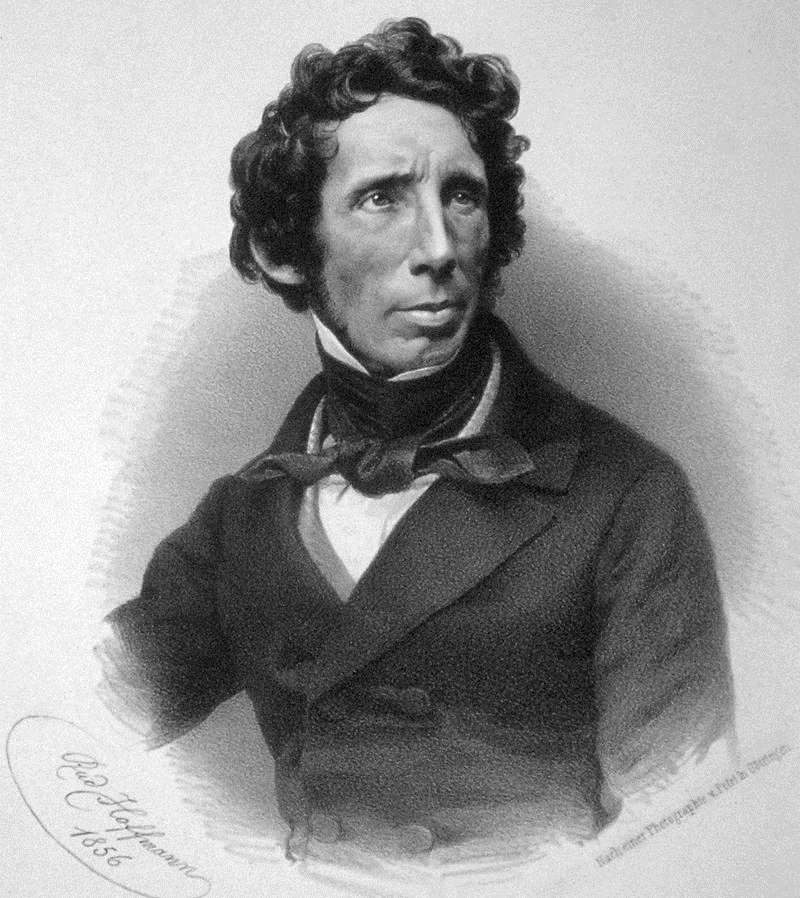

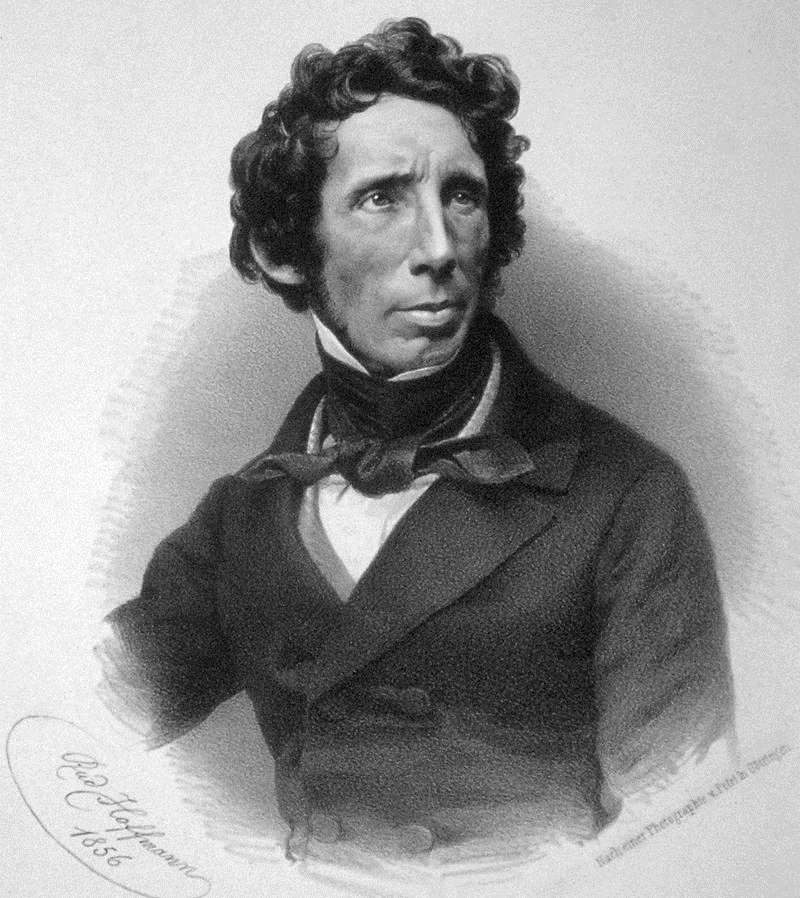

German chemist Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler () FRS(For) Hon FRSE (31 July 180023 September 1882) was a German chemist known for his work in inorganic chemistry, being the first to isolate the chemical elements beryllium and yttrium in pure metallic form. He was the fi ...

visited Ørsted in 1827 and received explicit permission to continue the aluminium research, which Ørsted "did not have time" for. Wöhler repeated Ørsted's experiments but did not identify any aluminium. (Wöhler later wrote to Berzelius, "what Oersted assumed to be a lump of aluminium was certainly nothing but aluminium-containing potassium".) He conducted a similar experiment, mixing anhydrous aluminium chloride with potassium, and produced a powder of aluminium. After hearing about this, Ørsted suggested that his own aluminium might have contained potassium. Wöhler continued his research and in 1845 was able to produce small pieces of the metal and described some of its physical properties. Wöhler's description of the properties indicates that he had obtained impure aluminium. Other scientists also failed to reproduce Ørsted's experiment, and Wöhler was credited as the discoverer for many years. While Ørsted was not concerned with the priority of the discovery, some Danes tried to demonstrate he had obtained aluminium. In 1921, the reason for the inconsistency between Ørsted's and Wöhler's experiments was discovered by Danish chemist Johan Fogh, who demonstrated that Ørsted's experiment was successful thanks to use of a large amount of excess aluminium chloride and an amalgam with low potassium content. In 1936, scientists from American aluminium producing company Alcoa

Alcoa Corporation (an acronym for Aluminum Company of America) is a Pittsburgh-based industrial corporation. It is the world's eighth-largest producer of aluminum. Alcoa conducts operations in 10 countries. Alcoa is a major producer of primar ...

successfully recreated that experiment. However, many later sources still credit Wöhler with the discovery of aluminium, as well as its successful isolation in a relatively pure form.

Early industrial production

Since Wöhler's method could not yield large amounts of aluminium, the metal remained uncommon; its

Since Wöhler's method could not yield large amounts of aluminium, the metal remained uncommon; its cost

In production, research, retail, and accounting, a cost is the value of money that has been used up to produce something or deliver a service, and hence is not available for use anymore. In business, the cost may be one of acquisition, in whic ...

had exceeded that of gold before a new method was devised. In 1852, aluminium was sold at US$34 per ounce. In comparison, the price of gold at the time was $19 per ounce.

French chemist Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville

Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville (11 March 18181 July 1881) was a French chemist.

He was born in the island of St Thomas in the Danish West Indies, where his father was French consul. Together with his elder brother Charles he was educate ...

announced an industrial method of aluminium production in 1854 at the Paris Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at t ...

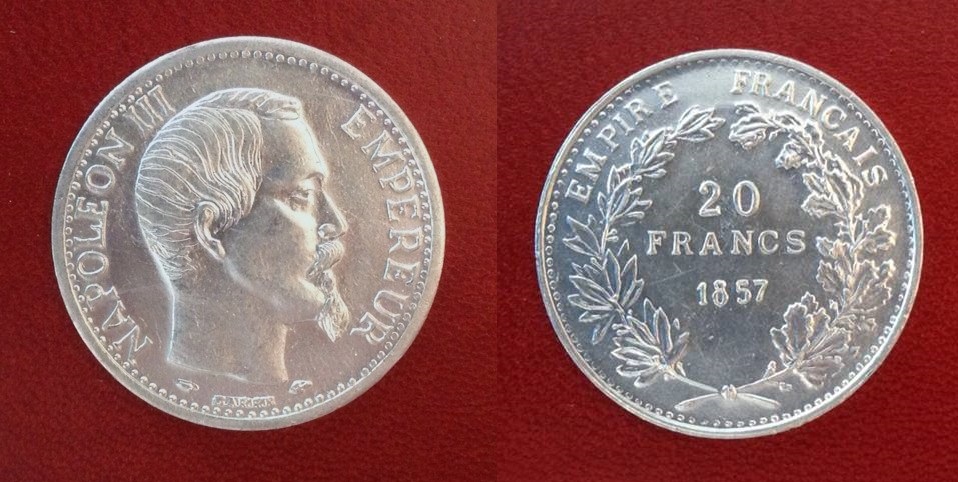

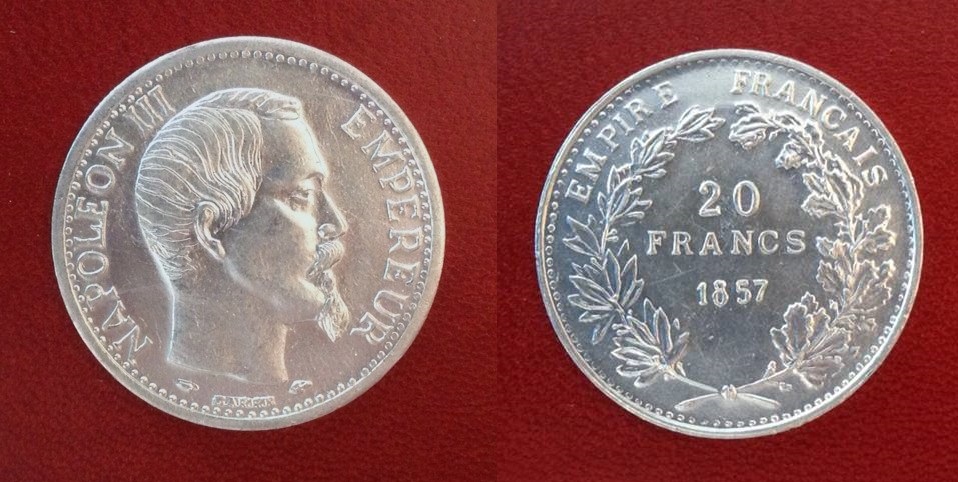

. Aluminium chloride could be reduced by sodium, a metal more convenient and less expensive than potassium used by Wöhler. Deville was able to produce an ingot of the metal. Napoleon III of France

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

promised Deville an unlimited subsidy for aluminium research; in total, Deville used 36,000 French franc

The franc (, ; sign: F or Fr), also commonly distinguished as the (FF), was a currency of France. Between 1360 and 1641, it was the name of coins worth 1 livre tournois and it remained in common parlance as a term for this amount of money. It w ...

s—20 times the annual income of an ordinary family. Napoleon's interest in aluminium lay in its potential military use: he wished weapons, helmets, armor, and other equipment for the French army could be made of the new light, shiny metal. While the metal was still not displayed to the public, Napoleon is reputed to have held a banquet where the most honored guests were given aluminium utensils while others made do with gold.

Twelve small ingots of aluminium were later exhibited for the first time to the public at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. The metal was presented as "the silver from clay" (aluminium is very similar to silver visually), and this name was soon widely used. It attracted widespread attention; it was suggested aluminium be used in arts, music, medicine, cooking, and tableware. The metal was noticed by the avant-garde writers of the time—Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

, Nikolay Chernyshevsky

Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky ( – ) was a Russian literary and social critic, journalist, novelist, democrat, and socialist philosopher, often identified as a utopian socialist and leading theoretician of Russian nihilism. He was ...

, and Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the '' Voyages extra ...

—who envisioned its use in the future. However, not all attention was favorable. Newspapers wrote, "The Parisian expo put an end to the fairy tale of the silver from clay", saying that much of what had been said about the metal was exaggerated if not untrue and that the amount of the presented metal—about a kilogram—contrasted with what had been expected and was "not a lot for a discovery that was said to turn the world upside down". Overall, the fair led to the eventual commercialization of the metal. That year, aluminium was put to the market at a price of 300 F per kilogram. At the next fair in Paris in 1867, visitors were presented with aluminium wire and foil as well a new alloy— aluminium bronze, notable for its low cost of production, high resistance to corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engi ...

, and desirable mechanical properties.

Manufacturers did not wish to divert resources from producing well-known (and marketable) metals, such as iron and

Manufacturers did not wish to divert resources from producing well-known (and marketable) metals, such as iron and bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids suc ...

, to experiment with a new one; moreover, produced aluminium was still not of great purity and differed in properties by sample. This led to an initial general reluctance to produce the new metal. Deville and partners established the world's first industrial production of aluminium at a smelter in Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

in 1856. Deville's smelter moved that year to La Glacière and then Nanterre

Nanterre (, ) is the prefecture of the Hauts-de-Seine department in the western suburbs of Paris. It is located some northwest of the centre of Paris. In 2018, the commune had a population of 96,807.

The eastern part of Nanterre, bordering t ...

, and in 1857 to Salindres. For the factory in Nanterre, an output of 2 kilograms of aluminium per day was recorded; with a purity of 98%. Originally, production started with synthesis of pure alumina, which was obtained from calcination of ammonium alum. In 1858, Deville was introduced to bauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO ...

and soon developed into what became known as the Deville process, employing the mineral as a source for alumina production. In 1860, Deville sold his aluminium interests to Henri Merle

Pechiney SA was a major aluminium conglomerate based in France. The company was acquired in 2003 by the Alcan Corporation, headquartered in Canada. In 2007, Alcan itself was taken over by mining giant Rio Tinto Alcan.

Prior to its acquisition, ...

, a founder of Compagnie d'Alais et de la Camargue; this company dominated the aluminium market in France decades later.

Some chemists, including Deville, sought to use cryolite as the source ore, but with little success. British engineer William Gerhard set up a plant with cryolite as the primary raw material in Battersea, London, in 1856, but technical and financial difficulties forced the closure of the plant in three years. British ironmaster

Some chemists, including Deville, sought to use cryolite as the source ore, but with little success. British engineer William Gerhard set up a plant with cryolite as the primary raw material in Battersea, London, in 1856, but technical and financial difficulties forced the closure of the plant in three years. British ironmaster Isaac Lowthian Bell

Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell, 1st Baronet, FRS (18 February 1816 – 20 December 1904) was a Victorian ironmaster and Liberal Party politician from Washington, County Durham, in the north of England. He was described as being "as famous in his day ...

produced aluminium from 1860 to 1874. During the opening of his factory, he waved to the crowd with a unique and costly aluminium top hat

A top hat (also called a high hat, a cylinder hat, or, informally, a topper) is a tall, flat-crowned hat for men traditionally associated with formal wear in Western dress codes, meaning white tie, morning dress, or frock coat. Traditional ...

. No statistics about this production can be recovered, but it "cannot be very high". Deville's output grew to 1 metric ton per year in 1860; 1.7 metric tons in 1867; and 1.8 metric tons in 1872. At the time, demand for aluminium was low: for example, sales of Deville's aluminium by his British agents equaled 15 kilograms in 1872. Aluminium at the time was often compared with silver; like silver, it was found to be suitable for making jewelry

Jewellery ( UK) or jewelry ( U.S.) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment, such as brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the clothes. From a w ...

and objéts d'art. Price for aluminium steadily declined to 240 F in 1859; 200 F in 1862; 120 F in 1867.

Other production sites began to appear in the 1880s. British engineer James Fern Webster launched the industrial production of aluminium by reduction with sodium in 1882; his aluminium was much purer than Deville's (it contained 0.8% impurities whereas Deville's typically contained 2%). World production of aluminium in 1884 equaled 3.6 metric tons. In 1884, American architect William Frishmuth

William Frishmuth (April 22, 1830–August 1, 1893) was a German-born American architect and metallurgist.

William Frishmuth was born Johann Wilhelm Gottfried Frischmuth in 1830 in Coburg in the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (now Germany). Fr ...

combined production of sodium, alumina, and aluminium into a single technological process; this contrasted with the previous need to collect sodium, which combusts in water and sometimes air; his aluminium production cost was about $16 per pound (compare to silver's cost of $19 per pound, or the French price, an equivalent of $12 per pound). In 1885, Aluminium- und Magnesiumfabrik started production in Hemelingen

Hemelingen (Plattdeutsch ') is a German city and district of Bremen belonging to the Bremen district East.

Geography and districts

Hemelingen is located about 6 km east of the center of Bremen on the right bank of the Weser. The neighbori ...

. Its production figures strongly exceeded those of the factory in Salindres but the factory stopped production in 1888. In 1886, American engineer Hamilton Castner

Hamilton Young Castner (September 11, 1858 – October 11, 1899) was an American industrial chemist.

Biography

He was born in Brooklyn, New York and educated at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, then at the Columbia University School of Mine ...

devised a method of cheaper production of sodium, which decreased the cost of aluminium production to $8 per pound, but he did not have enough capital to construct a large factory like Deville's. In 1887, he constructed a factory in Oldbury; Webster constructed a plant nearby and bought Castner's sodium to use it in his own production of aluminium. In 1889, German metallurgist Curt Netto launched a method of reduction of cryolite with sodium that produced aluminium containing 0.5–1.0% of impurities.

Electrolytic production and commercialization

Aluminium was first produced independently using electrolysis in 1854 by the German chemistRobert Wilhelm Bunsen

Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen (;

30 March 1811

– 16 August 1899) was a German chemist. He investigated emission spectra of heated elements, and discovered caesium (in 1860) and rubidium (in 1861) with the physicist Gustav Kirchhoff. The Buns ...

and Deville. Their methods did not become the basis for industrial production of aluminium because electrical supplies were inefficient at the time. This changed only with Belgian engineer Zénobe-Théophile Gramme's invention of the dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos were the first electrical generators capable of delivering power for industry, and the foundati ...

in 1870, which made creation of large amounts of electricity possible. The invention of the three-phase current by Russian engineer Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky

Mikhail Osipovich Dolivo-Dobrovolsky (russian: Михаи́л О́сипович Доли́во-Доброво́льский; german: Michail von Dolivo-Dobrowolsky or ''Michail Ossipowitsch Doliwo-Dobrowolski''; – ) was a Russian Empire ...

in 1889 made transmission of this electricity over long distances achievable. Soon after his discovery, Bunsen moved on to other areas of interest while Deville's work was noticed by Napoleon III; this was the reason Deville's Napoleon-funded research on aluminium production had been started. Deville quickly realized electrolytic production was impractical at the time and moved on to chemical methods, presenting results later that year.

Electrolytic mass production remained difficult because electrolytic baths could not withstand prolonged contact with molten salts, succumbing to corrosion. The first attempt to overcome this for aluminium production was made by American engineer Charles Bradley in 1883. Bradley heated aluminium salts internally: the highest temperature was inside the bath and the lowest was on its walls, where salts would solidify and protect the bath. Bradley then sold his patent claim to brothers Alfred and Eugene Cowles, who used it at a smelter in Lockport and later in Stoke-upon-Trent

Stoke-upon-Trent, commonly called Stoke is one of the six towns that along with Hanley, Burslem, Fenton, Longton and Tunstall form the city of Stoke-on-Trent, in Staffordshire, England.

The town was incorporated as a municipal borough in 18 ...

but the method was modified to yield alloys rather than pure aluminium. Bradley applied for a patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

in 1883; due to his broad wordings, it was rejected as composed of prior art

Prior art (also known as state of the art or background art) is a concept in patent law used to determine the patentability of an invention, in particular whether an invention meets the novelty and the inventive step or non-obviousness criteria ...

. After a necessary two-year break, he re-applied. This process lasted for six years, as the patent office questioned whether Bradley's ideas were original. When Bradley was granted a patent, electrolytic aluminium production had already been in place for several years.

The first large-scale production method was independently developed by French engineer Paul Héroult

Paul (Louis-Toussaint) Héroult (10 April 1863 – 9 May 1914) was a French scientist. He was the inventor of the aluminium electrolysis and developed the first successful commercial electric arc furnace. He lived in Thury-Harcourt, Normandy. ...

and American engineer Charles Martin Hall

Charles Martin Hall (December 6, 1863 – December 27, 1914) was an American inventor, businessman, and chemist. He is best known for his invention in 1886 of an inexpensive method for producing aluminum, which became the first metal to atta ...

in 1886; it is now known as the Hall–Héroult process

The Hall–Héroult process is the major industrial process for smelting aluminium. It involves dissolving aluminium oxide (alumina) (obtained most often from bauxite, aluminium's chief ore, through the Bayer process) in molten cryolite, and el ...

. Electrolysis of pure alumina is impractical, given its very high melting point; both Héroult and Hall realized it could be greatly lowered by the presence of molten cryolite. Héroult was granted a patent in France in April and subsequently in several other European countries; he also applied for a U.S. patent in May. After securing a patent, Héroult could not find interest in his invention. When asking professionals for advice, he was told there was no demand for aluminium but some for aluminium bronze. The factory in Salindres did not wish to improve its process. In 1888, Héroult and his companions founded Aluminium Industrie Aktiengesellschaft and started industrial production of aluminium bronze in Neuhausen am Rheinfall. Then, Société électrométallurgique française was founded in Paris. They convinced Héroult to return to France, purchased his patents, and appointed him as the director of a smelter in Isère

Isère ( , ; frp, Isera; oc, Isèra, ) is a landlocked department in the southeastern French region of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. Named after the river Isère, it had a population of 1,271,166 in 2019.

At the same time, Hall produced aluminium by the same process in his home at Oberlin. He applied for a patent in July, and the patent office notified Hall of an "interference" with Héroult's application. The Cowles brothers offered legal support. By then, Hall had failed to develop a commercial process for his first investors, and he turned to experimenting at Cowles' smelter in Lockport. He experimented for a year without much success but gained the attention of investors. Hall co-founded the Pittsburgh Reduction Company in 1888 and initiated production of aluminium. Hall's patent was granted in 1889. In 1889, Hall's production began to use the principle of internal heating. By September 1889, Hall's production grew to at a cost of $0.65 per pound. By 1890, Hall's company still lacked capital and did not pay

At the same time, Hall produced aluminium by the same process in his home at Oberlin. He applied for a patent in July, and the patent office notified Hall of an "interference" with Héroult's application. The Cowles brothers offered legal support. By then, Hall had failed to develop a commercial process for his first investors, and he turned to experimenting at Cowles' smelter in Lockport. He experimented for a year without much success but gained the attention of investors. Hall co-founded the Pittsburgh Reduction Company in 1888 and initiated production of aluminium. Hall's patent was granted in 1889. In 1889, Hall's production began to use the principle of internal heating. By September 1889, Hall's production grew to at a cost of $0.65 per pound. By 1890, Hall's company still lacked capital and did not pay  The total amount of unalloyed aluminium produced using Deville's chemical method from 1856 to 1889 equaled 200 metric tons. Production in 1890 alone was 175 metric tons. It grew to 715 metric tons in 1893 and to 4,034 metric tons in 1898. The price fell to $2 per pound in 1889 and to $0.5 per pound in 1894.

By the end of 1889, a consistently high purity of aluminium produced via electrolysis had been achieved. In 1890, Webster's factory went obsolete after an electrolysis factory was opened in England. Netto's main advantage, the high purity of the resulting aluminium, was outmatched by electrolytic aluminium and his company closed the following year. Compagnie d'Alais et de la Camargue also decided to switch to electrolytic production, and their first plant using this method was opened in 1895.

Modern production of the aluminium metal is based on the Bayer and Hall–Héroult processes. It was further improved in 1920 by a team led by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Söderberg. Previously,

The total amount of unalloyed aluminium produced using Deville's chemical method from 1856 to 1889 equaled 200 metric tons. Production in 1890 alone was 175 metric tons. It grew to 715 metric tons in 1893 and to 4,034 metric tons in 1898. The price fell to $2 per pound in 1889 and to $0.5 per pound in 1894.

By the end of 1889, a consistently high purity of aluminium produced via electrolysis had been achieved. In 1890, Webster's factory went obsolete after an electrolysis factory was opened in England. Netto's main advantage, the high purity of the resulting aluminium, was outmatched by electrolytic aluminium and his company closed the following year. Compagnie d'Alais et de la Camargue also decided to switch to electrolytic production, and their first plant using this method was opened in 1895.

Modern production of the aluminium metal is based on the Bayer and Hall–Héroult processes. It was further improved in 1920 by a team led by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Söderberg. Previously,

Prices for aluminium declined, and by the early 1890s, the metal had become widely used in jewelry, eyeglass frames, optical instruments, and many everyday items. Aluminium cookware began to be produced in the late 19th century and gradually supplanted copper and

Prices for aluminium declined, and by the early 1890s, the metal had become widely used in jewelry, eyeglass frames, optical instruments, and many everyday items. Aluminium cookware began to be produced in the late 19th century and gradually supplanted copper and  During the first half of the 20th century, the

During the first half of the 20th century, the

Earth's first artificial satellite, launched in 1957, consisted of two joined aluminium hemispheres. All subsequent spacecraft have used aluminium to some extent. The

Earth's first artificial satellite, launched in 1957, consisted of two joined aluminium hemispheres. All subsequent spacecraft have used aluminium to some extent. The  The increase of the real price, and changes of tariffs and taxes, began the redistribution of world producers' shares: the United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan accounted for nearly 60% of world's primary production in 1972 (and their combined share of consumption of primary aluminium was also close to 60%); but their combined share only slightly exceeded 10% in 2012. The production shift began in the 1970s with production moving from the United States, Japan, and Western Europe to Australia, Canada, the Middle East, Russia, and China, where it was cheaper due to lower electricity prices and favorable state regulation, such as low taxes or subsidies. Production costs in the 1980s and 1990s declined because of advances in technology, lower energy and alumina prices, and high exchange rates of the United States dollar.

In the 2000s, the BRIC countries' (Brazil, Russia, India and China) combined share grew from 32.6% to 56.5% in primary production and 21.4% to 47.8% in primary consumption. China has accumulated an especially large share of world production, thanks to an abundance of resources, cheap energy, and governmental stimuli; it also increased its share of consumption from 2% in 1972 to 40% in 2010. The only other country with a two-digit percentage was the United States with 11%; no other country exceeded 5%. In the United States, Western Europe and Japan, most aluminium was consumed in transportation, engineering, construction, and packaging.

In the mid-2000s, increasing energy, alumina and carbon (used in anodes) prices caused an increase in production costs. This was amplified by a shift in currency exchange rates: not only a weakening of the United States dollar, but also a strengthening of the

The increase of the real price, and changes of tariffs and taxes, began the redistribution of world producers' shares: the United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan accounted for nearly 60% of world's primary production in 1972 (and their combined share of consumption of primary aluminium was also close to 60%); but their combined share only slightly exceeded 10% in 2012. The production shift began in the 1970s with production moving from the United States, Japan, and Western Europe to Australia, Canada, the Middle East, Russia, and China, where it was cheaper due to lower electricity prices and favorable state regulation, such as low taxes or subsidies. Production costs in the 1980s and 1990s declined because of advances in technology, lower energy and alumina prices, and high exchange rates of the United States dollar.

In the 2000s, the BRIC countries' (Brazil, Russia, India and China) combined share grew from 32.6% to 56.5% in primary production and 21.4% to 47.8% in primary consumption. China has accumulated an especially large share of world production, thanks to an abundance of resources, cheap energy, and governmental stimuli; it also increased its share of consumption from 2% in 1972 to 40% in 2010. The only other country with a two-digit percentage was the United States with 11%; no other country exceeded 5%. In the United States, Western Europe and Japan, most aluminium was consumed in transportation, engineering, construction, and packaging.

In the mid-2000s, increasing energy, alumina and carbon (used in anodes) prices caused an increase in production costs. This was amplified by a shift in currency exchange rates: not only a weakening of the United States dollar, but also a strengthening of the

At the same time, Hall produced aluminium by the same process in his home at Oberlin. He applied for a patent in July, and the patent office notified Hall of an "interference" with Héroult's application. The Cowles brothers offered legal support. By then, Hall had failed to develop a commercial process for his first investors, and he turned to experimenting at Cowles' smelter in Lockport. He experimented for a year without much success but gained the attention of investors. Hall co-founded the Pittsburgh Reduction Company in 1888 and initiated production of aluminium. Hall's patent was granted in 1889. In 1889, Hall's production began to use the principle of internal heating. By September 1889, Hall's production grew to at a cost of $0.65 per pound. By 1890, Hall's company still lacked capital and did not pay

At the same time, Hall produced aluminium by the same process in his home at Oberlin. He applied for a patent in July, and the patent office notified Hall of an "interference" with Héroult's application. The Cowles brothers offered legal support. By then, Hall had failed to develop a commercial process for his first investors, and he turned to experimenting at Cowles' smelter in Lockport. He experimented for a year without much success but gained the attention of investors. Hall co-founded the Pittsburgh Reduction Company in 1888 and initiated production of aluminium. Hall's patent was granted in 1889. In 1889, Hall's production began to use the principle of internal heating. By September 1889, Hall's production grew to at a cost of $0.65 per pound. By 1890, Hall's company still lacked capital and did not pay dividend

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders. When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a portion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-i ...

s; Hall had to sell some of his shares to attract investments. During that year, a new factory in Patricroft was constructed. The smelter in Lockport was unable to withstand the competition and shut down by 1892.

The Hall–Héroult process converts alumina into the metal. Austrian chemist Carl Josef Bayer

Carl Josef Bayer (also Karl Bayer, March 4, 1847 – October 4, 1904) was an Austrian chemist who invented the Bayer process of extracting alumina from bauxite, essential to this day to the economical production of aluminium.

Bayer had been worki ...

discovered a way of purifying bauxite to yield alumina in 1888 at a textile factory in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

and was issued a patent later that year; this is now known as the Bayer process

The Bayer process is the principal industrial means of refining bauxite to produce alumina (aluminium oxide) and was developed by Carl Josef Bayer. Bauxite, the most important ore of aluminium, contains only 30–60% aluminium oxide (Al2O3), th ...

. Bayer sintered

Clinker nodules produced by sintering

Sintering or frittage is the process of compacting and forming a solid mass of material by pressure or heat without melting it to the point of liquefaction.

Sintering happens as part of a manufacturing ...

bauxite with alkali and leached it with water; after stirring the solution and introducing a seeding agent to it, he found a precipitate of pure aluminium hydroxide, which decomposed to alumina on heating. In 1892, while working at a chemical plant in Yelabuga, he discovered the aluminium contents of bauxite dissolved in the alkaline leftover from isolation of alumina solids; this was crucial for the industrial employment of this method. He was issued a patent later that year.

anode

An anode is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the device. A common mnemonic is ...

electrodes had been made from pre-baked coal blocks, which quickly corrupted and required replacement; the team introduced continuous electrodes made from a coke and tar

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black bi ...

paste in a reduction chamber. This advance greatly increased the world output of aluminium.

Mass usage

cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

cookware in the first decades of the 20th century. Aluminium foil

Aluminium foil (or aluminum foil in North American English; often informally called tin foil) is aluminium prepared in thin metal leaves with a thickness less than ; thinner gauges down to are also commonly used. Standard household foil is typ ...

was popularized at that time. Aluminium is soft and light, but it was soon discovered that alloying it with other metals could increase its hardness while preserving its low density. Aluminium alloys found many uses in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For instance, aluminium bronze is applied to make flexible bands, sheets, and wire, and is widely employed in the shipbuilding and aviation industries. Aviation used a new aluminium alloy, duralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age hardening, age-hardenable aluminium alloys. The term is a combination of ''Dürener'' and ''aluminium''.

Its ...

, invented in 1903. Aluminium recycling began in the early 1900s and has been used extensively since as aluminium is not impaired by recycling and thus can be recycled repeatedly. At this point, only the metal that had not been used by end-consumers was recycled. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

, major governments demanded large shipments of aluminium for light strong airframes. They often subsidized factories and the necessary electrical supply systems. Overall production of aluminium peaked during the war: world production of aluminium in 1900 was 6,800 metric tons; in 1916, annual production exceeded 100,000 metric tons. The war created a greater demand for aluminium, which the growing primary production was unable to fully satisfy, and recycling grew intensely as well. The peak in production was followed by a decline, then a swift growth.

During the first half of the 20th century, the

During the first half of the 20th century, the real price

In economics, nominal value is measured in terms of money, whereas real value is measured against goods or services. A real value is one which has been adjusted for inflation, enabling comparison of quantities as if the prices of goods had not ...

for aluminium fell continuously from $14,000 per metric ton in 1900 to $2,340 in 1948 (in 1998 United States dollars). There were some exceptions such as the sharp price rise during World War I. Aluminium was plentiful, and in 1919 Germany began to replace its silver coins with aluminium ones; more and more denominations were switched to aluminium coins as hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

progressed in the country. By the mid-20th century, aluminium had become a part of everyday lives, becoming an essential component of housewares. Aluminium freight cars first appeared in 1931. Their lower mass allowed them to carry more cargo. During the 1930s, aluminium emerged as a civil engineering material used in both basic construction and building interiors. Its use in military engineering for both airplanes and tank engines advanced.

Aluminium obtained from recycling was considered inferior to primary aluminium because of poorer chemistry control as well as poor removal of dross and slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting ( pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-p ...

s. Recycling grew overall but depended largely on the output of primary production: for instance, as electric energy prices declined in the United States in the late 1930s, more primary aluminium could be produced using the energy-expensive Hall–Héroult process. This rendered recycling less necessary, and thus aluminium recycling rates went down. By 1940, mass recycling of post-consumer aluminium had begun.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, production peaked again, exceeding 1,000,000 metric tons for the first time in 1941. Aluminium was used heavily in aircraft production and was a strategic material of extreme importance; so much so that when Alcoa (successor of Hall's Pittsburgh Reduction Company and the aluminium production monopolist in the United States at the time) did not expand its production, the United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natur ...

proclaimed in 1941, "If America loses the war, it can thank the Aluminum Corporation of America". In 1939, Germany was the world's leading producer of aluminium; the Germans thus saw aluminium as their edge in the war. Aluminium coins continued to be used but while they symbolized a decline on their introduction, by 1939, they had come to represent power. (In 1941, they began to be withdrawn from circulation to save the metal for military needs.) After the United Kingdom was attacked in 1940, it started an ambitious program of aluminium recycling; the newly appointed Minister of Aircraft Production

The Minister of Aircraft Production was, from 1940 to 1945, the British government minister at the Ministry of Aircraft Production, one of the specialised supply ministries set up by the British Government during World War II. It was responsible ...

appealed to the public to donate any household aluminium for airplane building. The Soviet Union received 328,100 metric tons of aluminium from its co-combatants from 1941 to 1945; this aluminium was used in aircraft and tank engines. Without these shipments, the output of the Soviet aircraft industry would have fallen by over a half.

After the wartime peak, world production fell for three late-war and post-war years but then regained its rapid growth. In 1954, the world output equaled 2,810,000 metric tons; this production surpassed that of copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

, historically second in production only to iron, making it the most produced non-ferrous metal

In metallurgy, non-ferrous metals are metals or alloys that do not contain iron ( allotropes of iron, ferrite, and so on) in appreciable amounts.

Generally more costly than ferrous metals, non-ferrous metals are used because of desirable prop ...

.

Aluminium Age

Earth's first artificial satellite, launched in 1957, consisted of two joined aluminium hemispheres. All subsequent spacecraft have used aluminium to some extent. The

Earth's first artificial satellite, launched in 1957, consisted of two joined aluminium hemispheres. All subsequent spacecraft have used aluminium to some extent. The aluminium can

An Aluminum can (British English: Tin can) is a single-use container for packaging made primarily of aluminum.

It is commonly used for food and beverages such as milk and soup but also for products such as oil, chemicals, and other liquids. Globa ...

was first manufactured in 1956 and employed as a container for drinks in 1958. In the 1960s, aluminium was employed for the production of wires and cables. Since the 1970s, high-speed trains have commonly used aluminium for its high strength-to-weight ratio. For the same reason, the aluminium content of cars is growing.

By 1955, the world market had been dominated by the Six Majors: Alcoa, Alcan

Alcan was a Canadian mining company and aluminum manufacturer. It was founded in 1902 as the Northern Aluminum Company, renamed Aluminum Company of Canada in 1925, and Alcan Aluminum in 1966. It took the name Alcan Incorporated in 2001. During t ...

(originated as a part of Alcoa), Reynolds, Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

, Pechiney

Pechiney SA was a major aluminium conglomerate based in France. The company was acquired in 2003 by the Alcan Corporation, headquartered in Canada. In 2007, Alcan itself was taken over by mining giant Rio Tinto Alcan.

Prior to its acquisition, ...

(merger of Compagnie d'Alais et de la Camargue that bought Deville's smelter and Société électrométallurgique française that hired Héroult), and Alusuisse (successor of Héroult's Aluminium Industrie Aktien Gesellschaft); their combined share of the market equaled 86%. From 1945, aluminium consumption grew by almost 10% each year for nearly three decades, gaining ground in building applications, electric cables, basic foils and the aircraft industry. In the early 1970s, an additional boost came from the development of aluminium beverage cans. The real price declined until the early 1970s; in 1973, the real price equaled $2,130 per metric ton (in 1998 United States dollars). The main drivers of the drop in price was the decline of extraction and processing costs, technological progress, and the increase in aluminium production, which first exceeded 10,000,000 metric tons in 1971.

In the late 1960s, governments became aware of waste from the industrial production; they enforced a series of regulations favoring recycling and waste disposal. Söderberg anodes, which save capital and labor to bake the anodes but are more harmful to the environment (because of a greater difficulty in collecting and disposing of the baking fumes), fell into disfavor, and production began to shift back to the pre-baked anodes. The aluminium industry began promoting the recycling of aluminium cans in an attempt to avoid restrictions on them. This sparked recycling of aluminium previously used by end-consumers: for example, in the United States, levels of recycling of such aluminium increased 3.5 times from 1970 to 1980 and 7.5 times to 1990. Production costs for primary aluminium grew in the 1970s and 1980s, and this also contributed to the rise of aluminium recycling. Closer composition control and improved refining technology diminished the quality difference between primary and secondary aluminium.

In the 1970s, the increased demand for aluminium made it an exchange commodity; it entered the London Metal Exchange

The London Metal Exchange (LME) is a futures and forwards exchange with the world's largest market in standarised forward contracts, futures contracts and options on base metals. The exchange also offers contracts on ferrous metals and precious ...

, the world's oldest industrial metal exchange, in 1978. Since then, aluminium has been traded for United States dollars and its price fluctuated along with the currency's exchange rate. The need to exploit lower-grade poorer quality deposits and fast increasing input costs of energy, but also bauxite, as well as changes in exchange rates and greenhouse gas

A greenhouse gas (GHG or GhG) is a gas that absorbs and emits radiant energy within the thermal infrared range, causing the greenhouse effect. The primary greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere are water vapor (), carbon dioxide (), methane ...

regulation, increased the net cost of aluminium; the real price grew in the 1970s.

Chinese yuan

The renminbi (; symbol: ¥; ISO code: CNY; abbreviation: RMB) is the official currency of the People's Republic of China and one of the world's most traded currencies, ranking as the fifth most traded currency in the world as of April 2022. ...

. The latter became important as most Chinese aluminium was relatively cheap.

World output continued growing: in 2018, it was a record 63,600,000 metric tons before falling slightly in 2019. Aluminium is produced in greater quantities than all other non-ferrous metals combined. Its real price (in 1998 United States dollars) in 2019 was $1,400 per metric ton ($2,190 per ton in contemporary dollars).

See also

* List of countries by primary aluminium productionNotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * {{cite book , url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r8zTDQAAQBAJ, title=Aluminum in America: A History, last=Skrabec, first=Quentin R., publisher= McFarland, year=2017, isbn=978-1-4766-2564-5 Aluminium History of chemistryaluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It ha ...