History of Wrocław on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 985 Duke

In 985 Duke

Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

(German: ''Breslau)'' has long been the largest and culturally dominant city in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

, and is today the capital of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

's Lower Silesian Voivodeship.

The history of Wrocław starts at a crossroads in Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( pl, Dolny Śląsk; cz, Dolní Slezsko; german: Niederschlesien; szl, Dolny Ślōnsk; hsb, Delnja Šleska; dsb, Dolna Šlazyńska; Silesian German: ''Niederschläsing''; la, Silesia Inferior) is the northwestern part of the ...

. It was one of the centres of the Duchy and then Kingdom of Poland, and briefly, in the first half of the 13th century, the centre of half of the divided Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exi ...

. German settlers arrived in increasing numbers after the first Mongol invasion of Poland

The Mongol Invasion of Poland from late 1240 to 1241 culminated in the Battle of Legnica, where the Mongols defeated an alliance which included forces from fragmented Poland and their allies, led by Henry II the Pious, the Duke of Silesia. ...

in 1241, and Wrocław eventually became part of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

after the extinction of local Polish dukes in 1335. It was ruled by Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

between 1469 and 1490, and after the War of Austrian Succession

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

in the 18th century, the city and region were annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

, and in 1871 became part of the German Empire. In the interwar period and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the city witnessed discrimination and persecution of its Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

and Jewish inhabitants, including deportations to forced labour and Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

, and in addition, tens of thousands of forced labourers and prisoners of war of various nationalities were imprisoned in multiple German labour camps and prisons throughout the city. After World War II, Wrocław and most of Silesia were transferred again to Poland and the German-speaking majority of its population was expelled to Germany.

Origin

The city of Wrocław originated as a stronghold situated at the intersection of two long-existing trading routes, theVia Regia

The Via Regia (Royal Highway) is a European Cultural Route following the route of the historic road of the Middle Ages. There were many such ''viae regiae'' associated with the king in the medieval Holy Roman Empire.

History Origins

The V ...

and the Amber Road

The Amber Road was an ancient trade route for the transfer of amber from coastal areas of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Prehistoric trade routes between Northern and Southern Europe were defined by the amber trade.

...

. The city was founded in the 10th century, possibly by a local duke Wrocisław, who the city might also bear its name after. At the time the city was limited to the district of Ostrów Tumski (the Cathedral Island) and was first mentioned by Thietmar of Merseburg

Thietmar (also Dietmar or Dithmar; 25 July 9751 December 1018), Prince-Bishop of Merseburg from 1009 until his death, was an important chronicler recording the reigns of German kings and Holy Roman Emperors of the Ottonian (Saxon) dynasty. Two ...

in 1000 as "''Wrotizlava''".

Poland

In 985 Duke

In 985 Duke Mieszko I of Poland

Mieszko I (; – 25 May 992) was the first ruler of Poland and the founder of the first independent Polish state, the Duchy of Poland. His reign stretched from 960 to his death and he was a member of the Piast dynasty, a son of Siemomysł and a ...

of the Piast dynasty conquered Silesia and Wrocław. In 1000 Mieszko's son, Duke and future King Bolesław I of Poland Boleslav or Bolesław may refer to:

In people:

* Boleslaw (given name)

In geography:

*Bolesław, Dąbrowa County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

*Bolesław, Olkusz County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

*Bolesław, Silesian Voivodeship, Pol ...

, in the then capital of Poland, Gniezno

Gniezno (; german: Gnesen; la, Gnesna) is a city in central-western Poland, about east of Poznań. Its population in 2021 was 66,769, making it the sixth-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship. One of the Piast dynasty's chief cities, ...

, established the Bishopric of Wrocław

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

, along with the bishoprics of Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

and Kołobrzeg and the Archbishopric of Gniezno

The Archdiocese of Gniezno ( la, Archidioecesis Gnesnensis, pl, Archidiecezja Gnieźnieńska) is the oldest Latin Catholic archdiocese in Poland, located in the city of Gniezno.Odra river. Hugo Weczerka writes that around 1000 the town had approximately 1000 inhabitants. and after an uprising in 1037/38 against the church and probably also against the bishop and the representatives of the Polish king, who were expelled.Weczerka, p. 40 In 1038 Bohemia captured the city and owned her until 1054 when Poland regained control. In 1138 it became the capital of the Piast-ruled Duchy of Silesia, which slowly detached from Poland. By 1139 two more settlements were built. One belonged to Governor  Bishop of Wrocław was known as the prince-bishop ever since Bishop Przecław of Pogorzela (1341–1376) bought the Duchy of

Bishop of Wrocław was known as the prince-bishop ever since Bishop Przecław of Pogorzela (1341–1376) bought the Duchy of

When

When

After the demise of the

After the demise of the

Breslau became part of the German Empire in 1871, which was established at Versailles in defeated France. The early years were characterized by rapid economic growth, the so-called

Breslau became part of the German Empire in 1871, which was established at Versailles in defeated France. The early years were characterized by rapid economic growth, the so-called  Performing arts in the city received a notable boost too. In 1861 the Orchestral Society (''Orchesterverein'') was founded, which achieved a good reputation in 1880 when

Performing arts in the city received a notable boost too. In 1861 the Orchestral Society (''Orchesterverein'') was founded, which achieved a good reputation in 1880 when

The end of the German Empire led to anarchy all over Germany. In Breslau however, the imperial authorities were deposed without larger tumults. While, among others, Lord Mayor Paul Mattig and Archbishop Bertram called for a continuance of public duty and ordered General Pfeil of the VI Army Corps to release all political prisoners, ordered his soldiers to leave the barracks and, as his last military order, allowed a demonstration of the Social Democrats in the ''Jahrhunderthalle''. One day later soldiers councils in the army and the Committee of Public Safety were formed. On the same day, a ''Volksrat'' (peoples council) of Social Democrats, Liberals, the Catholic Centre Party and trade unions was founded, led by Social Democrat

The end of the German Empire led to anarchy all over Germany. In Breslau however, the imperial authorities were deposed without larger tumults. While, among others, Lord Mayor Paul Mattig and Archbishop Bertram called for a continuance of public duty and ordered General Pfeil of the VI Army Corps to release all political prisoners, ordered his soldiers to leave the barracks and, as his last military order, allowed a demonstration of the Social Democrats in the ''Jahrhunderthalle''. One day later soldiers councils in the army and the Committee of Public Safety were formed. On the same day, a ''Volksrat'' (peoples council) of Social Democrats, Liberals, the Catholic Centre Party and trade unions was founded, led by Social Democrat  Despite the largely peaceful transition Breslau faced several challenges which radicalized the political landscape of the city. Social conditions got worse as 170,000 soldiers and displaced persons were expected to return, with only 47,000 available quarters. The prospect of a Communist government was a major fear. The loss of nearby Posnania to a newly created

Despite the largely peaceful transition Breslau faced several challenges which radicalized the political landscape of the city. Social conditions got worse as 170,000 soldiers and displaced persons were expected to return, with only 47,000 available quarters. The prospect of a Communist government was a major fear. The loss of nearby Posnania to a newly created  After First World War the Polish community started having masses in Polish in the Churches of Saint Ann and since 1921 in St. Martin Church; the Polish consulate was opened on the Main Square, additionally, a Polish School was formed by Helena Adamczewska.Microcosm, page 361

Soon after tensions around the Upper Silesian plebiscite sparked violence in Breslau, where widespread rioting was mostly directed against the Inter-Allied Plebiscite Commission, especially the French, but also the Polish. The buildings of the Polish consulate and school were demolished and Polish library was burned along with several thousand volumes Problems culminated however in 1923. Hyperinflation ruined many people, and strikes and walk-outs swept all over Germany. 50 large shops in the commercial centre were looted in the city when partly anti-Semitic, riots broke out on 22 July, and six looters were killed.

In 1919, Breslau became the capital of the newly created

After First World War the Polish community started having masses in Polish in the Churches of Saint Ann and since 1921 in St. Martin Church; the Polish consulate was opened on the Main Square, additionally, a Polish School was formed by Helena Adamczewska.Microcosm, page 361

Soon after tensions around the Upper Silesian plebiscite sparked violence in Breslau, where widespread rioting was mostly directed against the Inter-Allied Plebiscite Commission, especially the French, but also the Polish. The buildings of the Polish consulate and school were demolished and Polish library was burned along with several thousand volumes Problems culminated however in 1923. Hyperinflation ruined many people, and strikes and walk-outs swept all over Germany. 50 large shops in the commercial centre were looted in the city when partly anti-Semitic, riots broke out on 22 July, and six looters were killed.

In 1919, Breslau became the capital of the newly created  After the incorporation of 54 communes between 1925 and 1930, the city expanded to 175 km2 and housed 600,000 people. Between 26 and 29 June 1930 it hosted the ''Deutsche Kampfspiele'', a sporting event for German athletes after Germany was excluded from the Olympic Games after World War I.

After the incorporation of 54 communes between 1925 and 1930, the city expanded to 175 km2 and housed 600,000 people. Between 26 and 29 June 1930 it hosted the ''Deutsche Kampfspiele'', a sporting event for German athletes after Germany was excluded from the Olympic Games after World War I.

This peaceful period ended with the Wall Street Crash and the following collapse of the German economy. Unemployment rose from 1.3 million in September 1929 to 6 million (1/3 of the working population) in 1933; in Breslau from 6,672 persons in 1925 to 23,978 in 1929, the worst figures in Germany after Chemnitz. The number of families living on welfare support was more than twice as high as in

This peaceful period ended with the Wall Street Crash and the following collapse of the German economy. Unemployment rose from 1.3 million in September 1929 to 6 million (1/3 of the working population) in 1933; in Breslau from 6,672 persons in 1925 to 23,978 in 1929, the worst figures in Germany after Chemnitz. The number of families living on welfare support was more than twice as high as in

In addition, a network of concentration camps and forced labour camps, or

In addition, a network of concentration camps and forced labour camps, or  Throughout most of World War II Breslau was not close to the fighting. The city became a haven for refugees, swelling in population to nearly one million. Polish resistance from the group

Throughout most of World War II Breslau was not close to the fighting. The city became a haven for refugees, swelling in population to nearly one million. Polish resistance from the group

In the summer of 1945, the city had a predominately German population who were expelled to one of the two post-war German states between 1945 and 1949. However, as was the case with other Lower Silesian cities, a considerable German presence remained in Wrocław until the late 1950s; the city's last German school closed in 1963. The population of Wrocław was soon increased by the resettlement of

In the summer of 1945, the city had a predominately German population who were expelled to one of the two post-war German states between 1945 and 1949. However, as was the case with other Lower Silesian cities, a considerable German presence remained in Wrocław until the late 1950s; the city's last German school closed in 1963. The population of Wrocław was soon increased by the resettlement of

In May 1997 Wrocław was visited by

In May 1997 Wrocław was visited by

Breslauer Urkundenbuch

– complete collection of all deeds of the city

Codex Diplomaticus Silesiae T.11 Breslauer Stadtbuch

– liber civitatis (town book) of Wroclaw, containing the councilmen since 1287 and documents regarding the constitutional history

Codex Diplomaticus Silesiae T.3: Henricus pauper

– account book of Wroclaw, 1299–1358 * Dorn, Leonard (2016), Regimentskultur und Netzwerk. Dietrich Goswin von Bockum-Dolffs und das Kürassier-Regiment No. 1 in Breslau 1788-1805 (Vereinigte Westfälische Adelsarchive e.V., Veröffentlichung Nr. 20). Münster * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Wrocław

Piotr Włostowic

Herb ŁabędźPiotr Włostowic ( 1080 – 1153), also known as Peter Wlast or ''Włost'') was a Polish noble, castellan of Wrocław, and a ruler (''możnowładca'') of part of Silesia. From 1117 he was voivode (''palatyn'') of the Duke of Poland ...

(a.k.a. Piotr Włast Dunin; ca. 1080–1153) and was situated near his residence on the Olbina by the St. Vincent's Benedictine Abbey. The other settlement was founded on the left bank of the Oder River, near the present seat of the university. It was located on the Via Regia that lead from Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

and Legnica) and followed through Opole, and Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

to Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

.

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

, Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

, Jewish, Walloon and German communities existed in the city.

In the first half of the 13th-century duke Henry I the Bearded

Henry the Bearded ( pl, Henryk (Jędrzych) Brodaty, german: Heinrich der Bärtige; c. 1165/70 – 19 March 1238) was a Polish duke from the Piast dynasty.

He was Duke of Silesia at Wrocław from 1201, Duke of Kraków and High Duke of all Pol ...

of the Silesian line of the Piast dynasty, managed to reunite much of the divided Polish kingdom. He became the duke of Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

(Polonia Minor

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

) in 1232, which gave him the title of the senior duke of Poland (see Testament of Bolesław III Krzywousty

A testament is a document that the author has sworn to be true. In law it usually means last will and testament.

Testament or The Testament can also refer to:

Books

* ''Testament'' (comic book), a 2005 comic book

* ''Testament'', a thriller nov ...

). Henry started striving for the Polish crown. His activity in this field was continued by his son and successor Henry II the Pious

Henry II the Pious ( pl, Henryk II Pobożny; 1196 – 9 April 1241) was Duke of Silesia and High Duke of Poland as well as Duke of South-Greater Poland from 1238 until his death. Between 1238 and 1239 he also served as regent of Sandomierz and ...

whose work towards this goal was halted by his sudden death in 1241 ( Battle of Legnica). Polish territories acquired by the Silesian dukes in this period are called "The monarchy of the Silesian Henries". Wrocław was the centre of the divided Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exi ...

.

The city was devastated in 1241 during the first Mongol invasion of Poland

The Mongol Invasion of Poland from late 1240 to 1241 culminated in the Battle of Legnica, where the Mongols defeated an alliance which included forces from fragmented Poland and their allies, led by Henry II the Pious, the Duke of Silesia. ...

. The inhabitants burned down their own city to force the Mongols to a quick withdrawal. The invasion, according to Norman Davies, led German historiography to portray the Mongol attack as an event which eradicated the Polish community. However, in light of historical research this is doubtful, as many Polish settlements remained, even in the 14th century, especially on the right bank of the Oder and Polish names such as Baran or Cebula appear including among Wrocław's ruling elite.

Georg Thum, Maciej Lagiewski, Halina Okolska and Piotr Oszczanowski write that the decimated population was replenished by many Germans.Thum, p. 316 A different thesis is presented by Norman Davies who writes that it is wrong to portray people of that time as "Germans" as their identities were those of Saxons and Bavarians, while historian Norbert Conrads argues that a Polish identity didn't exist either, a view shared by Czech author František R. Kraus. While Germanisation started, Norman Davies writes that "Vretslav was a multi-ethnic city in the Middle Ages. Its ethnic composition moved in an endless state of flux, changing with each political and cultural ebb and flow to which it was exposed". German author Georg Thum states that Breslau, the German name of the city, appeared for the first time in written records, and the city council from the beginning used only the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and German.

In 1245, in Wrocław, Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

friar Benedict of Poland, considered one of the first Polish explorers, joined Italian diplomat Giovanni da Pian del Carpine

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, variously rendered in English as ''John of Pian de Carpine'', ''John of Plano Carpini'' or ''Joannes de Plano'' (c. 11851 August 1252), was a medieval Italian diplomat, archbishop and explorer and one of the firs ...

, on his journey to the seat of the Mongol Khan near Karakorum

Karakorum (Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, ''Kharkhorum''; Mongolian Script:, ''Qaraqorum''; ) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan dynasty in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in th ...

, the capital of the Mongol Empire. It was the first such journey by Europeans, and they returned with the letter from Güyük Khan to Pope Innocent IV.

The new and rebuilt town adopted Magdeburg rights

Magdeburg rights (german: Magdeburger Recht; also called Magdeburg Law) were a set of town privileges first developed by Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor (936–973) and based on the Flemish Law, which regulated the degree of internal autonomy within ...

in 1262 and, at the end of the 13th century joined the Hanseatic League. The expanded town was around 60 hectares in size and the new Main Market Square (Rynek), which was covered with timber-framed houses, became the new centre of the town. The original foundation, Ostrów Tumski, was now the religious centre. With the ongoing Ostsiedlung the Polish Piast dynastyEncyklopedia Powszechna PWN Warsaw 1975 vol. III page 505 dukes remained in control of the region, however, their influence declined continuously as the self-administration rights of the city council increased. German historian Norbert Conrads writes that they adopted the German language and culture and became Germanized in the 13th century. Norman Davies writes that German historiography has tried to present the Silesian branch of Polish Piasts as subjects of early Germanization who wished to enter the Holy Roman Empire, but that this theory is inaccurate. Wrotzila – despite the beginnings of Germanization – remained in close union with the Polish church, and local Piasts remained active in Polish politics, while Polish was still used at the court in the 14th century

During much of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

Wrocław was ruled by Dukes of the Piast dynasty. In 1335 the last Piast Duke of Wrocław, Henry VI the Good

Henry VI the Good (also known as of Wrocław) ( pl, Henryk VI Dobry or Wrocławski) (18 March 1294 – 24 November 1335) was a Duke of Wrocław from 1296 (with his brothers as co-rulers until 1311).

He was the second son of Henry V the Fat, Du ...

died. As a result, the city passed to John of Luxembourg

John the Blind or John of Luxembourg ( lb, Jang de Blannen; german: link=no, Johann der Blinde; cz, Jan Lucemburský; 10 August 1296 – 26 August 1346), was the Count of Luxembourg from 1313 and King of Bohemia from 1310 and titular King of ...

, who fought a war with Casimir the Great over Silesia. John died, while fighting in France, and the war ended inconclusively. The issue was closed only in 1372 between Charles IV of Luxembourg and Louis I of Hungary; and while the city lost political ties to the Polish state, it remained connected to Poland by religious links and the existence of Polish population within it. Jan Długosz

Jan Długosz (; 1 December 1415 – 19 May 1480), also known in Latin as Johannes Longinus, was a Polish priest, chronicler, diplomat, soldier, and secretary to Bishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki of Kraków. He is considered Poland's first histo ...

described the foreign rule over Wrocław as unlawful and expressed hope that it would eventually return to Poland.

Bishop of Wrocław was known as the prince-bishop ever since Bishop Przecław of Pogorzela (1341–1376) bought the Duchy of

Bishop of Wrocław was known as the prince-bishop ever since Bishop Przecław of Pogorzela (1341–1376) bought the Duchy of Grodków

Grodków (; szl, Grodkōw) is a town in Brzeg County, Opole Voivodeship in Poland, the administrative seat of Gmina Grodków. It is located in the Silesian Lowlands of the Oder basin, in the historic Upper Silesia region, about south of Brz ...

from Duke Bolesław III the Generous

Boleslaw III the Wasteful ( pl, Bolesław III Rozrzutny; 23 September 1291 – Brieg, 21 April 1352), was a Duke of Legnica, Brzeg (Brieg) from 1296 until 1342, and Duke of Wrocław from 1296 until 1311.

He was the eldest son of Henry V the Fa ...

and added it to the episcopal Duchy of Nysa, after which the Bishops of Wrocław

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

had the titles of Prince of Nysa and Dukes of Grodków, taking precedence over the other Silesian rulers.

Holy Roman Empire and Hungary

In 1348, the city was incorporated with almost the entirety of Silesia into theHoly Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

, and a ''Landeshauptmann'' (Provincial governor) was appointed to administrate the region. Between 1342 and 1344 two fires destroyed large parts of the city. In 1352 Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, visited the town. His successors Wenceslaus

Wenceslaus, Wenceslas, Wenzeslaus and Wenzslaus (and other similar names) are Latinized forms of the Czech name Václav. The other language versions of the name are german: Wenzel, pl, Wacław, Więcesław, Wieńczysław, es, Wenceslao, russian ...

and Sigismund Sigismund (variants: Sigmund, Siegmund) is a German proper name, meaning "protection through victory", from Old High German ''sigu'' "victory" + ''munt'' "hand, protection". Tacitus latinises it '' Segimundus''. There appears to be an older form of ...

became involved in a long-lasting feud with the city and its magistrate, culminating in the revolt of the guilds in 1418 when local craftsmen killed seven councillors. In a tribunal two years later, when Sigismund was in town, 27 ringleaders were executed. He also called up for a Reichstag in the same year, which discussed the earlier happenings in the city.

In June 1466, in Wrocław, Polish diplomat Jan Długosz

Jan Długosz (; 1 December 1415 – 19 May 1480), also known in Latin as Johannes Longinus, was a Polish priest, chronicler, diplomat, soldier, and secretary to Bishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki of Kraków. He is considered Poland's first histo ...

held a meeting with a papal legate, starting a peace process

A peace process is the set of sociopolitical negotiations, agreements and actions that aim to solve a specific armed conflict.

Definitions

Prior to an armed conflict occurring, peace processes can include the prevention of an intra-state or in ...

between Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and the Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

, which a few months later culminated in the signing of a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

in Toruń

)''

, image_skyline =

, image_caption =

, image_flag = POL Toruń flag.svg

, image_shield = POL Toruń COA.svg

, nickname = City of Angels, Gingerbread city, Copernicus Town

, pushpin_map = Kuyavian-Pom ...

that ended the Thirteen Years' War, the longest of Polish–Teutonic wars.

George of Poděbrady

George of Kunštát and Poděbrady (23 April 1420 – 22 March 1471), also known as Poděbrad or Podiebrad ( cs, Jiří z Poděbrad; german: Georg von Podiebrad), was the sixteenth King of Bohemia, who ruled in 1458–1471. He was a leader of the ...

was elected as Silesia's overlord, the city opposed him since he was a Hussite

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

and instead sided with his Catholic rival Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi Mátyás, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/Matijaš Korvin, sk, Matej Korvín, cz, Matyáš Korvín; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several m ...

. After Breslau fought alongside Corvinus against George in 1466, the local classes rendered homage to the king on 31 May 1469 in the city, where the king also met the daughter of mayor Krebs, Barbara, whom he took as his mistress. In 1474 the city was besieged by combined Polish-Bohemian forces, however in November 1474 Kings Casimir IV of Poland

Casimir is classically an English, French and Latin form of the Polish name Kazimierz. Feminine forms are Casimira and Kazimiera. It means "proclaimer (from ''kazać'' to preach) of peace (''mir'')."

List of variations

*Belarusian: Казі ...

, his son Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Matthias Corvinus of Hungary met in the nearby village of Muchobór Wielki (present-day district of Wrocław) and in December 1474 a ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state act ...

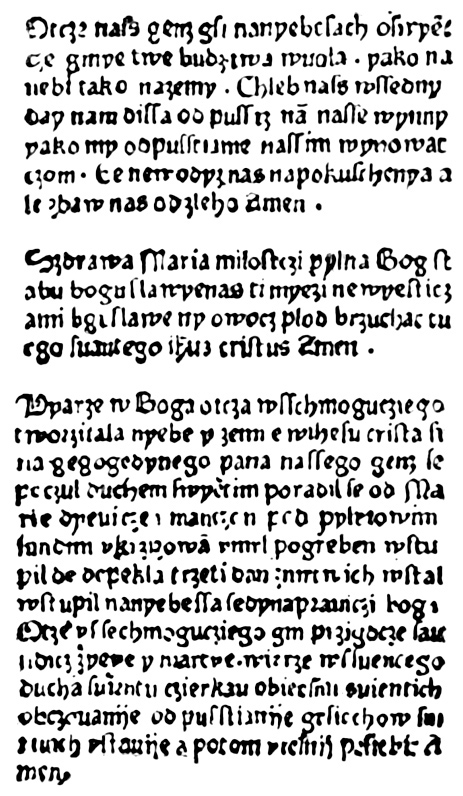

was signed, according to which the city remained under Hungarian rule. Matthias Corvinus incorporated the city with Silesia in his dominion, which he controlled until his death in 1490. 1475 marks the beginning of movable type printing in the city and in Silesia, when opened his printing shop ('' Drukarnia Świętokrzyska''). That same year he published the ', which contains the first-ever text printed in Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

. It was also the first ever printing in Silesia. The first illustration of the city was published in the '' Nuremberg Chronicle'' in 1493. Documents of that time referred to the town by many variants of the name including ''Wratislaw'', ''Bresslau'' and ''Presslau''.

Habsburg Monarchy

The ideas of theProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

reached Breslau already in 1518, and in 1519 the writings of Luther

Luther may refer to:

People

* Martin Luther (1483–1546), German monk credited with initiating the Protestant Reformation

* Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968), American minister and leader in the American civil rights movement

* Luther (give ...

, Eck and the opening of the Leipzig Disputation

The Leipzig Debate (german: Leipziger Disputation) was a theological disputation originally between Andreas Karlstadt, Martin Luther and Johann Eck. Karlstadt, the dean of the Wittenberg theological faculty, felt that he had to defend Luther ...

by Mosellanus were published by local printer Adam Dyon. In 1523 the town council unanimously, appointed Johann Heß as the new pastor of St. Maria Magdalena and thus introduced the Reformation in Breslau. In 1524 the town council issued a decree that obliged all clerics to the Protestant sermon and in 1525 another decree banned a number of Catholic customs. Breslau had become dominated by Protestants although a Catholic minority remained. Norman Davies states that as a city it was located on the borderline between Polish and German parts of Silesia, writing that "Vretslav lay astride the dividing line"; it also hosted a Czech community.

After the death of Louis II in the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

in 1526, the Habsburg monarchy of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

inherited Silesia and the city of Breslau. In 1530 Ferdinand I awarded Breslau its current coat of arms. On 11 October 1609 German emperor Rudolf II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the Hous ...

granted the Letter of Majesty

The Letter of Majesty (1609) was a 17th-century European document, reluctantly signed by the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, granting religious tolerance to both Protestant and Catholic citizens living in the estates of Bohemia. The letter also ...

, which ensured the free exercise of church services for all Silesian Protestants. During Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

the city suffered badly, was occupied by Saxon and Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

troops and lost 18,000 of its 40,000 residents to plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

.

The Counter-Reformation had started with Rudolf II and Martin Gerstmann, bishop of Breslau. One of his successors, bishop Charles of Austria, did not accept the letter of the majesty on his territory. At the same time, the emperor encouraged several Catholic orders to settle in Breslau. The Minorites came back in 1610, the Jesuits arrived in 1638, the Capuchins in 1669, the Franciscans in 1684 and the Ursulines in 1687. These orders undertook an unequalled amount of construction which shaped the appearance of the city until 1945. The Jesuits were the main representatives of the Counter-Reformation in Breslau and Silesia. Much more feared were the Liechtensteiner dragoons, which converted people by force and expelled those who refused. At the end of the Thirty Years' War, Breslau was only one of a few Silesian cities which stayed Protestant, and after the Treaty of Altranstädt of 1707 four churches were given back to the local Protestants.

During the Counter-Reformation, the intellectual life of the city, which was shaped by Protestantism and Humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and Agency (philosophy), agency of Human, human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical in ...

, flourished, as the Protestant bourgeoisie of the city lost its role as the patron of the arts to the Catholic orders. Breslau and Silesia, which possessed 6 of the 12 leading grammar schools in the Holy Roman Empire, became the centre of German Baroque literature. Poets such as Martin Opitz

Martin Opitz von Boberfeld (23 December 1597 – 20 August 1639) was a German poet, regarded as the greatest of that nation during his lifetime.

Biography

Opitz was born in Bunzlau (Bolesławiec) in Lower Silesia, in the Principality of ...

, Andreas Gryphius

Andreas Gryphius (german: Andreas Greif; 2 October 161616 July 1664) was a German poet and playwright. With his eloquent sonnets, which contains "The Suffering, Frailty of Life and the World", he is considered one of the most important Baroque ...

, Christian Hoffmann von Hoffmannswaldau

Christian Hoffmann von Hoffmannswaldau (baptised 25 December 1616 – 4 April 1679) was a German poet of the Baroque era.

He was born and died in Breslau (Wrocław) in Silesia. During his education in Danzig (Gdańsk) and Leiden, he befrie ...

, Daniel Casper von Lohenstein

Daniel Casper (25 January 1635 in Nimptsch, Niederschlesien – 28 April 1683 in Breslau, Niederschlesien), also spelled Daniel Caspar, and referred to from 1670 as Daniel Casper von Lohenstein, was a Baroque Silesian playwright, lawyer, diplo ...

and Angelus Silesius

Angelus Silesius (9 July 1677), born Johann Scheffler and also known as Johann Angelus Silesius, was a German Catholic priest and physician, known as a mystic and religious poet. Born and raised a Lutheran, he adopted the name ''Angelus'' (Lati ...

formed the so-called First and Second Silesian school of poets which shaped the German literature of that time.

The dominance of the German population under the Habsburg rule in the city became more visible, while the Polish population diminished in numbers, although it did not disappear.Microcosm, page 182 Only a few families from the upper and middle classes celebrated their Polish roots, despite having Polish ancestors, and while the Polish population was reinforced by migrants and merchants, many of them became Germanized. Nevertheless, Poles continued to exist in the city, mostly living on the right bank of Oder river also known as "Polish side". The Polish community was led by such priests as Stanislaw Bzowski or Michał Kusz, who fought for the continued existence of Polish schools in the city, and addressed their flock in Polish; Latin masses were interspersed with hymns and prayers in Polish.

In 1702 the Jesuit academy was founded by Leopold I and named after himself, the Leopoldine Academy.

Prussia

During theWar of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's ...

in the 1740s, most of Silesia was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

. Prussia's claims were derived from the agreement, rejected by the Habsburgs, between the Silesian Piast rulers of the duchy and the Hohenzollerns who secured the Prussian succession after the extinction of the Piasts. The Protestant citizenry didn't fight against the armies of Protestant Prussia and Frederick II of Prussia captured the city without a struggle in January 1741. In November 1741 the Silesian classes rendered homage to Frederick. In the following years, Prussian armies often stayed in the city during the winter month. After three wars Empress Maria Theresa renounced Silesia and Breslau in the Treaty of Hubertusburg

The Treaty of Hubertusburg (german: Frieden von Hubertusburg) was signed on 15 February 1763 at Hubertusburg Castle by Prussia, Austria and Saxony to end the Third Silesian War. Together with the Treaty of Paris, signed five days earlier, it mark ...

in 1763.

The Protestants of the city could now express their faith without limitation, and the new Prussian authorities also allowed the establishment of a Jewish community.

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

in 1806, Breslau was occupied by an army of the Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine, also known as Napoleonic Germany, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austria an ...

between 6 December 1806 to 7 January 1807. The Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berli ...

disrupted trade almost completely. The fortifications of the city were levelled and almost every monastery and cloister secularized. The Protestant Viadrina university of Frankfurt (Oder) was relocated to Breslau in 1811, united with the local Catholic university of the Jesuits and formed the new Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelm-Universität (Wrocław University

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, ro ...

).

In 1813 King Frederick William III of Prussia gave a speech in Breslau signalling Prussia's intent to join the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

against Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. He also donated the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

and issued the proclamation "An mein Volk" (to my people), summoning the Prussian people to war against the French. The city became the centre of the Liberation movement

A liberation movement is an organization or political movement leading a rebellion, or a non-violent social movement, against a colonial power or national government, often seeking independence based on a nationalist identity and an anti-imperial ...

against Napoleon Bonaparte as volunteers from all over Germany gathered in Breslau, among them Theodor Körner, Friedrich Ludwig Jahn and Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow

Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm Freiherr von Lützow (18 May 17826 December 1834) was a Prussian general notable for his organization and command of the '' Lützow Freikorps'' of volunteers during the Napoleonic Wars.

Early life

Lützow was born in Berlin ...

, who set up his Lützow Free Corps

Lützow Free Corps ( ) was a volunteer force of the Prussian army during the Napoleonic Wars. It was named after its commander, Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow. The Corpsmen were also widely known as the “''Lützower Jäger''“ or “''Schwarz ...

in the city.

The Prussian reforms of Stein

Stein is a German, Yiddish and Norwegian word meaning "stone" and "pip" or "kernel". It stems from the same Germanic root as the English word stone. It may refer to:

Places In Austria

* Stein, a neighbourhood of Krems an der Donau, Lower Aust ...

and Hardenberg

Hardenberg (; nds-nl, Haddenbarreg or '' 'n Arnbarg'') is a city and municipality in the province of Overijssel, Eastern Netherlands. The municipality of Hardenberg has a population of about 60,000, with about 19,000 living in the city. It recei ...

led to a sustainable increase in prosperity in Silesia and Breslau. Due to the levelled fortifications, the city could grow beyond her old borders. Breslau became an important railway hub and a major industrial centre, notably of linen and cotton manufacture and the metal industry. Thanks to the unification of the Viadrina and Jesuit universities the city also became the biggest Prussian centre of sciences after Berlin, and the secularization laid the base for a rich museum landscape. In 1836 the Slavonic Literary Society was founded in the city by Czech scholar Jan Evangelista Purkyně

Jan Evangelista Purkyně (; also written Johann Evangelist Purkinje) (17 or 18 December 1787 – 28 July 1869) was a Czech anatomist and physiologist. In 1839, he coined the term '' protoplasm'' for the fluid substance of a cell. He was one of ...

with the assistance of Polish scholars Władysław Nehring and Wojciech Cybulski, its aim was to develop studies on Slavic languages and cultures; the Prussian authorities disbanded it in 1886

On 15 January 1841, the Chair of Slavistics was formed in the city, and headed by Professor František Čelakovský

František Ladislav Čelakovský (7 March 1799 Strakonice - 5 August 1852 Prague) was a Czech poet, translator, linguist, and literary critic. He was a major figure in the Czech " national revival". His most notable works are ''Ohlas písní rus ...

, it was the first institution of this kind in Germany

In 1854 the Jewish Theological Seminary was created, one of the first modern rabbi seminars in Europe. Its first director, Zecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

, was the principal founder of conservative Judaism.

German Empire

Breslau became part of the German Empire in 1871, which was established at Versailles in defeated France. The early years were characterized by rapid economic growth, the so-called

Breslau became part of the German Empire in 1871, which was established at Versailles in defeated France. The early years were characterized by rapid economic growth, the so-called Gründerzeit

(; "founders' period") was the economic phase in 19th-century Germany and Austria before the great stock market crash of 1873. In Central Europe, the age of industrialisation had been taking place since the 1840s. That period is not precisely ...

, although Breslau was hampered by protectionist policies of its natural markets in Austria-Hungary and Russia and had to turn to the German domestic market. Breslau's population grew from 208,000 in 1871 to 512,000 in 1910, yet the city was pushed down from being the third- to the seventh-biggest city in Germany. Among the population were the Polish and Jewish minorities.

The city spread out and incorporated outlying villages, like Kleinburg (Dworek) and Pöpelwitz (Popowice) in 1896, Herdain (Gaj) and Morgentau (Rakowiec) in 1904 and Gräbschen (Grabiszyn) in 1911. With the regulation of the Oder (Odra) modern garden suburbs like Leerbeutel (Zalesie) and Karlowitz (Karlowice) were built.

The official German census of 1905 listed 470,904 residents, thereof 20,536 Jews, 6,020 Poles and 3,752 others. Polish historians point to distortion of that number by German officials, and speak of several thousand more, or even 20,000 Poles living in it. Estimates however are difficult, since foreign residents were registered by citizenship rather than by nationality. Most of suburbs on right bank of Oder were Polish-speaking communities according to a source from 1874, and many photographs from this period indicate widespread use of Polish names;.

As a frontier city on the edge of the Slavonic world, Breslau was more assertively German than other cities of the empire, and Breslau was less friendly to Poles, Czechs or unassimilated Jews than, for example, Berlin was. During his one-year tenure as rector of the university Felix Dahn

Felix Dahn (9 February 1834 – 3 January 1912) was a German law professor, German nationalist author, poet and historian.

Biography

Ludwig Julius Sophus Felix Dahn was born in Hamburg as the oldest son of Friedrich (1811–1889) and Constanze ...

for instance banned all Polish student associations.

Woodworking, brewing, textiles and agriculture, Breslau's traditional industries, flourished, and service and manufacturing sectors were established, which benefited from the nearby heavy industry of Upper Silesia. Linke-Hofmann, specialized in locomotives, became one of the city's largest employers and one of Europe's biggest manufacturers of railway carriages. By the end of the 19th century, Breslau threatened to eclipse Berlin, the capital of Prussia and the German Empire, as the financial centre of the country. The retail sector flourished too, represented by modern stores of Barasch, Molinari, Wertheim or Petersdorff. At the end of the German Empire Breslau had become the economic, cultural and administrative centre of Eastern Germany.

While Breslau itself was mostly Protestant the city also housed the Roman Catholic Diocese of Breslau, the second-largest diocese in the world, and thus became entangled in Bismarcks Kulturkampf. According to Norman Davies, the city had a population divided among 63% Protestants, 32% Catholics and 5% Jews. At the time of the German Empire Although the open conflict between Breslau's Protestant majority and Catholics was avoided, public resentment was notable, most notably in the affairs of the numerous student corporations. Meanwhile, Breslau became the focus of the Old Lutheran Church. In 1883 the Old Lutheran Theological Seminar was opened, which attracted numerous scholars, among them Rudolf Rocholl. By 1905 the community already had 75 pastors and 52,000 members.

The German Jewry of Breslau formed the ''Einheitsgemeinde'' (united community) of Orthodox and Reform Jews and thus narrowing the gap between both schools. In 1872 Reformed Rabbi Joel and his Orthodox counterpart Gedaliah Tiktin jointly consecrated Breslau's New Synagogue. From 14,000 in 1871 the Jewish community grew to 20,000 in 1910, thus becoming the third-largest in Germany. Breslau's confident, vibrant and assimilated community, with countless social, charitable, cultural and educational organisations, became a model for others. The first Jewish students' fraternity in the German Empire, the Viadrina, was created in 1886 in Breslau. Polish student organisations included Concordia, Polonia, and a branch of the Sokol

The Sokol movement (, ''falcon'') is an all-age gymnastics organization first founded in Prague in the Czech region of Austria-Hungary in 1862 by Miroslav Tyrš and Jindřich Fügner. It was based upon the principle of " a strong mind in a ...

association.

While most of Silesia's greats of the 19th century, such as Gustav Freytag

Gustav Freytag (; 13 July 1816 – 30 April 1895) was a German novelist and playwright.

Life

Freytag was born in Kreuzburg (Kluczbork) in Silesia. After attending the school at Oels (Oleśnica), he studied philology at the universities of ...

, Adolph Menzel

Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel (8 December 18159 February 1905) was a German Realist artist noted for drawings, etchings, and paintings. Along with Caspar David Friedrich, he is considered one of the two most prominent German painters of t ...

or Willibald Alexis

Willibald Alexis, the pseudonym of Georg Wilhelm Heinrich Häring (29 June 179816 December 1871), was a German historical novelist, considered part of the Young Germany movement.

Life

Alexis was born in Breslau, Silesia. His father, who cam ...

, had to leave Silesia to get recognized, the cultural exodus was stopped by the 1890s. In a few decades, Breslau was turned into a cultural centre of international notability. The old Art Academy moved into a bigger home and attracted artists like painter Max Wislicenus, sculptor Theodor von Gosen and future Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

winner Gerhard Hauptmann. The architectural section of the academy rose to prominence under the directorship of Hans Poelzig

Hans Poelzig (30 April 1869 – 14 June 1936) was a German architect, painter and set designer.

Life

Poelzig was born in Berlin in 1869 to Countess Clara Henrietta Maria Poelzig while she was married to George Acland Ames, an Englishman. Uncerta ...

, who contributed greatly, along with Max Berg, to the Neues Bauen movement, and Breslau gained fame as a centre of modernist architecture.

Performing arts in the city received a notable boost too. In 1861 the Orchestral Society (''Orchesterverein'') was founded, which achieved a good reputation in 1880 when

Performing arts in the city received a notable boost too. In 1861 the Orchestral Society (''Orchesterverein'') was founded, which achieved a good reputation in 1880 when Max Bruch

Max Bruch (6 January 1838 – 2 October 1920) was a German Romantic composer, violinist, teacher, and conductor who wrote more than 200 works, including three violin concertos, the first of which has become a prominent staple of the standard ...

was conductor of the orchestra, and later the Polish musician Rafał Ludwik Maszkowski, who conducted the orchestra till his death in 1901; he along with other Polish artists like Wanda Landowska

Wanda Aleksandra Landowska (5 July 1879 – 16 August 1959) was a Polish harpsichordist and pianist whose performances, teaching, writings and especially her many recordings played a large role in reviving the popularity of the harpsichord in ...

, Józef Śliwiński

Józef Śliwiński (15 December 1865, in Warsaw – 1930) was a Polish classical pianist, one of the outstanding interpreters of the poetic and romantic repertoire, especially Chopin and Schumann. He was taught by Theodor Leschetizky and Anton Rub ...

, Bronisław Huberman

Bronisław Huberman (19 December 1882 – 16 June 1947) was a Polish violinist. He was known for his individualistic interpretations and was praised for his tone color, expressiveness, and flexibility. The '' Gibson ex-Huberman Stradivarius'' ...

and Władysław Żeleński performed Polish-themed plays as part of the repertoire of the Orchesterverein. The Opera house (''Stadttheater''), which was reopened in 1871 after two fires, attracted artists like Leo Slezak

Leo Slezak (; 18 August 1873 – 1 June 1946) was a Moravian dramatic tenor. He was associated in particular with Austrian opera as well as the title role in Verdi's '' Otello''. He is the father of actors Walter Slezak and Margarete Slezak a ...

and Wilhelm Furtwängler

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler ( , , ; 25 January 188630 November 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century. He was a major ...

. Johannes Brahms paid tribute to the city when he composed the ''Akademische Festovertüre, Op. 80'' upon receiving an honorary doctorate in 1879.

Modern science flourished in the city, with a wide array of achievements in almost every department. During the German Empire, Breslau's scientists received four Nobel Prizes (plus two in literature). Above all, medical sciences were the flagship of academic research, where Breslau not only presented new theories but also new disciplines. Ferdinand Cohn, the director of the Institute of Plant Physiology, is considered a pioneer of bacteriology, while Albert Neisser, director of the Dermatology Clinic, discovered gonorrhoea, and Alois Alzheimer

Alois Alzheimer ( , , ; 14 June 1864 – 19 December 1915) was a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist and a colleague of Emil Kraepelin. Alzheimer is credited with identifying the first published case of "presenile dementia", which Kraep ...

, professor at the university, discovered the Alzheimer disease.

In the 1890s Breslau developed into a centre of Social Democracy in Germany. With one exception at least one member of the Silesian SPD

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been t ...

was sent to the Reichstag in Berlin, among them several prominent socialists like Eduard Bernstein, the former secretary of Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Schlieffen plan The Schlieffen Plan (german: Schlieffen-Plan, ) is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on ...

, while the 1st ''Leibkürassiere'' saw action at the battle of the Marne before they were moved to the Eastern Front. The end of Germany's western offensive and the absence of the VI. Army Corps left Silesia and Breslau dangerously exposed. In 1914/15 the Russian army stopped only 80 km to the east of Breslau, which led to the evacuation of children and the erection of barbed-wire defenses. The Silesian '' Schlieffen plan The Schlieffen Plan (german: Schlieffen-Plan, ) is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on ...

Landwehr

''Landwehr'', or ''Landeswehr'', is a German language term used in referring to certain national armies, or militias found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe. In different context it refers to large-scale, low-strength fortificatio ...

under General Remus von Woyrsch was rapidly deployed to face the Russian army, but German victories at the Masurian lakes and Gorlice soon eliminated this threat.

The population in the city suffered badly during the war. Food was rationed, and prices for potatoes or eggs skyrocketed by more than 200%, resulting in food riots. The "Turnip Winter

The Turnip Winter (German: ''Steckrübenwinter'') of 1916 to 1917 was a period of profound civilian hardship in Germany during World War I.

Introduction

For the duration of World War I, Germany was constantly under threat of starvation due to t ...

" of 1916/17 left many on the verge of starvation. Food hoarding was decreed with capital punishment in the city. After four years of war, Breslau's trade had fallen by 66 per cent. More than 8,000 people died of tuberculosis, and the population dropped from 540,000 to 472,000.

The end of World War I was followed by civil unrest and revolution in Germany. The garrison in Breslau mutinied in November, liberated convicts from jail, among them Rosa Luxemburg, looted shops and seized the offices of the ''Schlesische Zeitung'', Breslau's biggest newspaper. When emperor Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

left the country the German Empire dissolved.

Weimar Republic

The end of the German Empire led to anarchy all over Germany. In Breslau however, the imperial authorities were deposed without larger tumults. While, among others, Lord Mayor Paul Mattig and Archbishop Bertram called for a continuance of public duty and ordered General Pfeil of the VI Army Corps to release all political prisoners, ordered his soldiers to leave the barracks and, as his last military order, allowed a demonstration of the Social Democrats in the ''Jahrhunderthalle''. One day later soldiers councils in the army and the Committee of Public Safety were formed. On the same day, a ''Volksrat'' (peoples council) of Social Democrats, Liberals, the Catholic Centre Party and trade unions was founded, led by Social Democrat

The end of the German Empire led to anarchy all over Germany. In Breslau however, the imperial authorities were deposed without larger tumults. While, among others, Lord Mayor Paul Mattig and Archbishop Bertram called for a continuance of public duty and ordered General Pfeil of the VI Army Corps to release all political prisoners, ordered his soldiers to leave the barracks and, as his last military order, allowed a demonstration of the Social Democrats in the ''Jahrhunderthalle''. One day later soldiers councils in the army and the Committee of Public Safety were formed. On the same day, a ''Volksrat'' (peoples council) of Social Democrats, Liberals, the Catholic Centre Party and trade unions was founded, led by Social Democrat Paul Löbe

Paul Gustav Emil Löbe (14 December 1875 – 3 August 1967) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), a member and president of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic, and member of the Bundestag of West Germany. He ...

. As relations between the Volksrat and his opponents were mostly consensual the "revolution" in Breslau was peaceful.

Despite the largely peaceful transition Breslau faced several challenges which radicalized the political landscape of the city. Social conditions got worse as 170,000 soldiers and displaced persons were expected to return, with only 47,000 available quarters. The prospect of a Communist government was a major fear. The loss of nearby Posnania to a newly created

Despite the largely peaceful transition Breslau faced several challenges which radicalized the political landscape of the city. Social conditions got worse as 170,000 soldiers and displaced persons were expected to return, with only 47,000 available quarters. The prospect of a Communist government was a major fear. The loss of nearby Posnania to a newly created Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, the prospect of further losses in Upper Silesia and the transformation of neighbouring Bohemia into a hostile new state called Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

spread anxiety among people, who saw their city turn into an advance post of Germany.

The number of Poles in the city dropped from an already low 4–5.000 to 0.5 per cent 20 years later.

Riots of the Spartacists in February resulted in the death of five protesters and injured nineteen. A month later the Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

revolted, but only in Silesia did the Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo th ...

receive solid backing. The commander of the military district supported the coup d'état and four Freikorps peacefully took over large parts of the city. The governor of Silesia, Breslau's Chief of Police and the SPD President of Breslau was immediately purged. Kapp's government, however, collapsed after a week and the Freikorps in Breslau withdrew, killing 18 people and wounding countless others. Anti-Semitic propaganda, moreover, culminated in the murder of Bernhard Schottländer, the Jewish editor of the ''Schlesische Arbeiter-Zeitung

''Schlesische Arbeiter-Zeitung'' ('Silesian Workers Newspaper') was a left-wing German language newspaper published from Breslau, Province of Lower Silesia, Weimar Germany (present-day Wrocław in Poland) between 1919 and 1933.Bibliothek der Fried ...

''. Jewish stores and hotels were attacked by mobs in the city.

After First World War the Polish community started having masses in Polish in the Churches of Saint Ann and since 1921 in St. Martin Church; the Polish consulate was opened on the Main Square, additionally, a Polish School was formed by Helena Adamczewska.Microcosm, page 361

Soon after tensions around the Upper Silesian plebiscite sparked violence in Breslau, where widespread rioting was mostly directed against the Inter-Allied Plebiscite Commission, especially the French, but also the Polish. The buildings of the Polish consulate and school were demolished and Polish library was burned along with several thousand volumes Problems culminated however in 1923. Hyperinflation ruined many people, and strikes and walk-outs swept all over Germany. 50 large shops in the commercial centre were looted in the city when partly anti-Semitic, riots broke out on 22 July, and six looters were killed.

In 1919, Breslau became the capital of the newly created

After First World War the Polish community started having masses in Polish in the Churches of Saint Ann and since 1921 in St. Martin Church; the Polish consulate was opened on the Main Square, additionally, a Polish School was formed by Helena Adamczewska.Microcosm, page 361

Soon after tensions around the Upper Silesian plebiscite sparked violence in Breslau, where widespread rioting was mostly directed against the Inter-Allied Plebiscite Commission, especially the French, but also the Polish. The buildings of the Polish consulate and school were demolished and Polish library was burned along with several thousand volumes Problems culminated however in 1923. Hyperinflation ruined many people, and strikes and walk-outs swept all over Germany. 50 large shops in the commercial centre were looted in the city when partly anti-Semitic, riots broke out on 22 July, and six looters were killed.

In 1919, Breslau became the capital of the newly created Province of Lower Silesia

The Province of Lower Silesia (german: Provinz Niederschlesien; Silesian German: ''Provinz Niederschläsing''; pl, Prowincja Dolny Śląsk; szl, Prowincyjŏ Dolny Ślōnsk) was a province of the Free State of Prussia from 1919 to 1945. Between ...

, and its first head of government (German: Oberpräsident) was social democrat Felix Philipp. The Social democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

also won the Lower Silesian elections of 1921 with 51.19%, followed by the Catholic centre with 20.2%, DVP with 11.9%, DDP with 9.5% and the Communists with 3.6%.

The mid-1920s brought political stability, mostly due to the leadership of Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Ernst Stresemann (; 10 May 1878 – 3 October 1929) was a German statesman who served as chancellor in 1923 (for 102 days) and as foreign minister from 1923 to 1929, during the Weimar Republic.

His most notable achievement was the reconci ...

. In 1 Election result in Lower Silesia and Breslau showed a solid Socialist majority in 1924 and 1928. In 1925 the Silesian NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

was founded, the party however garnered only 1 per cent of the votes in 1928, well below the national average of 2,8 per cent.

After the incorporation of 54 communes between 1925 and 1930, the city expanded to 175 km2 and housed 600,000 people. Between 26 and 29 June 1930 it hosted the ''Deutsche Kampfspiele'', a sporting event for German athletes after Germany was excluded from the Olympic Games after World War I.

After the incorporation of 54 communes between 1925 and 1930, the city expanded to 175 km2 and housed 600,000 people. Between 26 and 29 June 1930 it hosted the ''Deutsche Kampfspiele'', a sporting event for German athletes after Germany was excluded from the Olympic Games after World War I.

This peaceful period ended with the Wall Street Crash and the following collapse of the German economy. Unemployment rose from 1.3 million in September 1929 to 6 million (1/3 of the working population) in 1933; in Breslau from 6,672 persons in 1925 to 23,978 in 1929, the worst figures in Germany after Chemnitz. The number of families living on welfare support was more than twice as high as in

This peaceful period ended with the Wall Street Crash and the following collapse of the German economy. Unemployment rose from 1.3 million in September 1929 to 6 million (1/3 of the working population) in 1933; in Breslau from 6,672 persons in 1925 to 23,978 in 1929, the worst figures in Germany after Chemnitz. The number of families living on welfare support was more than twice as high as in Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

or Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

. Public faith in democratic institutions faded and anti-democratic parties – Communists and Nazis – gained support. The battles of both were played out all over Germany, also in Breslau. In June 1931 the annual rally of the Stahlhelm, marked by violent rhetoric and clashes, took place in the city. The violence in the city spiralled in the summer of 1932. On 23 June a column of SA men was attacked by Communists, with eleven seriously injured, followed by a killed Socialist three days later. On 6 August grenades were thrown during battles between Nazis and Communists. In July 1932 Hitler spoke in Breslau, attracting 16,000 listeners. In the following elections, his party received 43% of the Breslau vote, the third-highest result in Germany. On 30 January 1933, he was appointed Chancellor of Germany.

Despite all turbulences, the cultural scene in the Weimar Republic and in Breslau flourished. The reorganized Academy of Arts reached its creative height under the directorship of Oskar Moll and can be considered a predecessor of the first Bauhaus

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the Bauhaus (), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 20 ...

. Many Bauhaus artists, among them Oskar Schlemmer

Oskar Schlemmer (4 September 1888 – 13 April 1943) was a German painter, sculptor, designer and choreographer associated with the Bauhaus school.

In 1923, he was hired as Master of Form at the Bauhaus theatre workshop, after working at the w ...

and Georg Muche

Georg Muche (8 May 1895 – 26 March 1987) was a German painter, printmaker, architect, author, and teacher.

Early life and education

Georg Muche was born on 8 May 1895 in Querfurt, in the Prussian Province of Saxony, and grew up in the Rhön ...

, taught in Breslau, while several lecturers and students of the academy became leading protagonists of the main artistic trends in the Weimar Republic, like Alexander Kanoldt, who was co-founder of the ''Munich New Secession'' and became one of the stars of the Neue Sachlichkeit

The New Objectivity (in german: Neue Sachlichkeit) was a movement in German art that arose during the 1920s as a reaction against expressionism. The term was coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the director of the '' Kunsthalle'' in Mannheim, w ...

, or Hans Scharoun

Bernhard Hans Henry Scharoun (20 September 1893 – 25 November 1972) was a German architect best known for designing the Berliner Philharmonie (home to the Berlin Philharmonic) and the Schminke House in Löbau, Saxony. He was an important ...

, an important exponent of Organic architecture

Organic architecture is a philosophy of architecture which promotes harmony between human habitation and the natural world. This is achieved through design approaches that aim to be sympathetic and well-integrated with a site, so buildings, furn ...

. In 1929 the Werkbund opened '' WuWa'' (german: link=no, Wohnungs-und Werkraumausstellung) in Breslau-Scheitnig, an international showcase of modern architecture by architects of the Silesian branch of the Werkbund.

During the inter-war years, the city was also the centre of the Polish national movement radiating towards other groups of Poles in Lower Silesia; it focused on Polish cultural life and organisational efforts.

Nazi period and World War II

The city became one of the largest support bases of the NSDAP movement, and in the 1932 elections the Nazi party received in it 43.5% of votes, achieving the third biggest victory in Weimar Germany A reason for the strong NSDAP support may have been that Breslau was the city among the eight largest cities of Germany with the highest rate of unemployment, which the Nazi party promised to tackle. Before theHolocaust