History of Worcester on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

"The First Settlers".

Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005.

"Vertis—The Roman Industrial Town, 1st–4th centuries A.D."

Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005. and may have built a small fort.''Roman Britain''

"Vertis".

/ref> There is no sign of municipal buildings that would indicate an administrative role. Earthwork defences encompassed the settlement, surrounding around ten hectares of land. In the 3rd century, Roman Worcester occupied a larger area than the subsequent medieval city, but silting of the

"The Late Roman and Post-Roman Settlement, 4th Century A.D.–A.D. 680".

Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005. This settlement is generally identified with the

The 28 Cities of Britain

" at Britannia. 2000.Newman, John Henry & al

''Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre'', Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92.

James Toovey (London), 1844. This is probably not a

Worcester in the years before the first millennium was a centre of monastic learning and church power.

Worcester in the years before the first millennium was a centre of monastic learning and church power.

Worcester was also a centre of medieval religious life; there were several monasteries until the dissolution. These included the

Worcester was also a centre of medieval religious life; there were several monasteries until the dissolution. These included the

The Dissolution saw the Priory's status change, as it lost its Benedictine monks. There were around 36 monks plus the Prior at dissolution in 1540 and some 16 were given pensions immediately or soon after, the rest being employed in the new Deanery. It was necessary to establish 'public schools' to replace monastic education in Worcester as elsewhere. This led to the establishment of King's School. Worcester School continued to teach. St Oswald's Hospital survived the dissolution, later providing

The Dissolution saw the Priory's status change, as it lost its Benedictine monks. There were around 36 monks plus the Prior at dissolution in 1540 and some 16 were given pensions immediately or soon after, the rest being employed in the new Deanery. It was necessary to establish 'public schools' to replace monastic education in Worcester as elsewhere. This led to the establishment of King's School. Worcester School continued to teach. St Oswald's Hospital survived the dissolution, later providing

Worcester equivocated about whether to support the Parliamentary cause before the outbreak of

Worcester equivocated about whether to support the Parliamentary cause before the outbreak of

Worcester Guildhall was rebuilt in 1721, replacing the earlier hall on the same site. The now

Worcester Guildhall was rebuilt in 1721, replacing the earlier hall on the same site. The now

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Worcester was a major centre for glove-making, employing nearly half the glovers in England at its peak (over 30,000 people). In 1815 the

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Worcester was a major centre for glove-making, employing nearly half the glovers in England at its peak (over 30,000 people). In 1815 the  Railways came to Worcester in 1850, with the opening Shrub Hill station, jointly owned by the

Railways came to Worcester in 1850, with the opening Shrub Hill station, jointly owned by the

History of the City of Worcester

* {{Authority control

Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

's early importance is partly due to its position on trade routes, but also because it was a centre of Church learning and wealth, due to the very large possessions of the See and Priory accumulated in the Anglo-Saxon period. After the reformation, Worcester continued as a centre of learning, with two early Grammar schools with strong links to Oxford University.

The city was often important for strategic military reasons, being close to Gloucester and Oxford, as well as Wales, which led to a number of attacks and sieges in the conflicts of the early medieval period. For similar reasons, it was valuable to the crown in the English Civil Wars.

The city was a centre of the cloth trade, and later of glove production. It had a number of foundries and made machine tools for the car industry.

In politics, Worcester often lagged behind other similar cities in municipal reform, and in the nineteenth and start of the twentieth century, retained corrupt electoral practices in Westminster elections long after gifts and bribes had been made unlawful.

Early history

The trade route which ran past Worcester, later forming part of theRoman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

Ryknild Street

Icknield Street or Ryknild Street is a Roman road in England, with a route roughly south-west to north-east. It runs from the Fosse Way at Bourton on the Water in Gloucestershire () to Templeborough in South Yorkshire (). It passes through A ...

, dates to Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

times. The position commanded a ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

over the River Severn

, name_etymology =

, image = SevernFromCastleCB.JPG

, image_size = 288

, image_caption = The river seen from Shrewsbury Castle

, map = RiverSevernMap.jpg

, map_size = 288

, map_c ...

(the river was tidal

Tidal is the adjectival form of tide.

Tidal may also refer to:

* ''Tidal'' (album), a 1996 album by Fiona Apple

* Tidal (king), a king involved in the Battle of the Vale of Siddim

* TidalCycles, a live coding environment for music

* Tidal (servic ...

past Worcester prior to public works projects in the 1840s) and was fortified

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere' ...

by the Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mod ...

around 400 BC. It would have been on the northern border of the Dobunni

The Dobunni were one of the Iron Age tribes living in the British Isles prior to the Roman conquest of Britain. There are seven known references to the tribe in Roman histories and inscriptions.

Various historians and archaeologists have examined ...

and probably subject to the larger communities of the Malvern hillforts.City of Worcester"The First Settlers".

Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005.

Roman and British

TheRoman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

settlement at the site passes unmentioned by Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's ''Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

'', the Antonine Itinerary

The Antonine Itinerary ( la, Itinerarium Antonini Augusti, "The Itinerary of the Emperor Antoninus") is a famous ''itinerarium'', a register of the stations and distances along various roads. Seemingly based on official documents, possibly ...

and the Register of Dignitaries, but would have grown up on the road opened between Glevum

Glevum (or, more formally, Colonia Nervia Glevensium, or occasionally ''Glouvia'') was originally a Roman fort in Roman Britain that became a " colonia" of retired legionaries in AD 97. Today, it is known as Gloucester, in the English county o ...

(Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east o ...

) and Viroconium

Viroconium or Uriconium, formally Viroconium Cornoviorum, was a Roman city, one corner of which is now occupied by Wroxeter, a small village in Shropshire, England, about east-south-east of Shrewsbury. At its peak, Viroconium is estimated to ...

(Wroxeter

Wroxeter is a village in Shropshire, England, which forms part of the civil parish of Wroxeter and Uppington, beside the River Severn, south-east of Shrewsbury.

'' Viroconium Cornoviorum'', the fourth largest city in Roman Britain, was site ...

) in the 40s and 50s AD. It may have been the "Vertis" mentioned in the 7th century Ravenna Cosmography. Using charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ...

from the Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the county of Gloucestershire, England. It forms a roughly triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and northwest, Herefordshire to ...

, the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

operated pottery kilns and ironworks at the siteCity of Worcester"Vertis—The Roman Industrial Town, 1st–4th centuries A.D."

Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005. and may have built a small fort.''Roman Britain''

"Vertis".

/ref> There is no sign of municipal buildings that would indicate an administrative role. Earthwork defences encompassed the settlement, surrounding around ten hectares of land. In the 3rd century, Roman Worcester occupied a larger area than the subsequent medieval city, but silting of the

Diglis Basin

Diglis Basin is a canal basin on the Worcester and Birmingham Canal. It is situated in Diglis in the centre of Worcester, England, near The Commandery (a command post during the English Civil War).

To the north is Tibberton (8.41 miles and 1 ...

caused the abandonment of Sidbury. Industrial production ceased and the settlement contracted to a defended position along the lines of the old British fort at the river terrace's southern end.City of Worcester"The Late Roman and Post-Roman Settlement, 4th Century A.D.–A.D. 680".

Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005. This settlement is generally identified with the

Nennius

Nennius – or Nemnius or Nemnivus – was a Welsh monk of the 9th century. He has traditionally been attributed with the authorship of the '' Historia Brittonum'', based on the prologue affixed to that work. This attribution is widely considere ...

(). Theodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th centur ...

(). ''Historia Brittonum'', VI. Composed after AD 830. Hosted at Latin Wikisource. listed among the 28 cities of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

in the ''History of the Britons

''The History of the Britons'' ( la, Historia Brittonum) is a purported history of the indigenous British ( Brittonic) people that was written around 828 and survives in numerous recensions that date from after the 11th century. The ''Historia Br ...

'' attributed to Nennius

Nennius – or Nemnius or Nemnivus – was a Welsh monk of the 9th century. He has traditionally been attributed with the authorship of the '' Historia Brittonum'', based on the prologue affixed to that work. This attribution is widely considere ...

.Ford, David Nash.The 28 Cities of Britain

" at Britannia. 2000.Newman, John Henry & al

''Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre'', Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92.

James Toovey (London), 1844. This is probably not a

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

name

A name is a term used for identification by an external observer. They can identify a class or category of things, or a single thing, either uniquely, or within a given context. The entity identified by a name is called its referent. A persona ...

but an adaption of its Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

name , "fort of the Weogoran".

The Anglo-Saxons

The settlement was eventually subsumed by the emerging Kingdom ofMercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, y ...

, In 680, Worcester was chosen—in preference to both the much larger Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east o ...

and the royal court at Winchcombe—to be the seat

A seat is a place to sit. The term may encompass additional features, such as back, armrest, head restraint but also headquarters in a wider sense.

Types of seat

The following are examples of different kinds of seat:

* Armchair, a chair ...

of a new bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

. This site of the new St Peter's was probably chosen due to the presence of Roman-era fortifications; many Roman sites were reused in this period by church communities, because of their perceived prestige.

It is likely that there was Christian occupation within the city defences at the Church of , which was likely British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, serving a sizeable parish. Two further churches were established by 800, St Margaret's and St Alban's. Between the four religious communities, along with people supplying the basics needed for everyday life, a considerable number of people would have lived in the settlement. Nevertheless, the site was an essentially private settlement. Worcester appears frequently in the historic records prior to the Viking era, often with reference to the church and monastic communities, and showing evidence of extensive ecclesiastical ownership of lands. In this early phase, the Bishop was already a powerful figure, collecting considerable dues from lands and properties owned, including the Droitwich saltworks.

The city became a public settlement during King Alfred

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who ...

's reign, when it was chosen to be the site of a 'burh', or fortified town, as part of efforts to create a network of defensible sites able to resist Viking invasions. The earls of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, y ...

fortified Worcester "for the protection of all the people" at the request of Bishop Werfrith. It appears that maintenance of the defences was to be paid for by the townspeople. A unique document detailing this and privileges granted to the church also outlines the existence of Worcester's market and borough court, differentiation between church and market quarters within the city, as well as the role of the King in relation to the roads.

Worcester's fortifications would most likely have established the line of the wall that was extant until the 1600s, perhaps excepting the south east area near the former castle. It is referred to as a wall by contemporaries, so may have been of stone.

Worcester in the years before the first millennium was a centre of monastic learning and church power.

Worcester in the years before the first millennium was a centre of monastic learning and church power. Oswald of Worcester

Oswald of Worcester (died 29 February 992) was Archbishop of York from 972 to his death in 992. He was of Danish ancestry, but brought up by his uncle, Oda, who sent him to France to the abbey of Fleury to become a monk. After a number of ye ...

was an important reformer, appointed Bishop in 961, jointly with York. The last Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Worcester, Wulfstan, or St Wulstan, was also an important reformer, and stayed in post until his death in 1095.

Worcester became the focus of tax resistance against the Danish Harthacanute

Harthacnut ( da, Hardeknud; "Tough-knot"; – 8 June 1042), traditionally Hardicanute, sometimes referred to as Canute III, was King of Denmark from 1035 to 1042 and King of the English from 1040 to 1042.

Harthacnut was the son of King ...

. Two huscarls were killed in May 1041 while attempting to collect taxes for the expanded navy, after being driven into the Priory, where they were murdered. A military force was sent to deal with the non-payment, while the townspeople attempted to defend themselves by moving to and occupying the island of Bevere, two miles up river, where they were then besieged. After Harthacnut's men had sacked the city and set it alight, agreement was reached.

Worcester was also the site of a mint during the late Anglo-Saxon period, with seven moneyers in the reign of Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

. This implies a middling role in trade for the city.

Medieval

Early medieval

Worcester was, for tax purposes, counted within Worcestershire's rural administration units (known as ''Hundred

100 or one hundred (Roman numeral: C) is the natural number following 99 and preceding 101.

In medieval contexts, it may be described as the short hundred or five score in order to differentiate the English and Germanic use of "hundred" to des ...

s'') at the start of the Norman period. It was administratively independent.

The first Norman Sheriff of Worcestershire, Urse d'Abetot

Urse d'Abetot ( - 1108) was a Norman who followed King William I to England, and became Sheriff of Worcestershire and a royal official under him and Kings William II and Henry I. He was a native of Normandy and moved to England shortly after the ...

oversaw the construction of a new castle at Worcester,Barlow ''William Rufus'' p. 152 although nothing now remains of the castle.Pettifer ''English Castles'' p. 280 Worcester Castle was in place by 1069, its outer bailey built on land that had previously been the cemetery for the monks of the Worcester cathedral chapter.Williams "Introduction" ''Digital Domesday'' "Norman Settlement" section The motte

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy to ...

of the castle overlooked the river, just south of the cathedral.Holt "Worcester in the Time of Wulfstan" ''St Wulfstan and His World'' pp. 132–133

Worcester's growth and position as a market town distributing goods and produce came from its river crossing and bridge, and its position on the road network. In the 14th century, the nearest bridges over the Severn were at Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east o ...

and Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a town in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the 2011 Census was 12,079.

Histor ...

. The main road from London to mid-Wales ran through Worcester. The road north west ran to Kidderminster, Bridgnorth and Shrewsbury; and the road north through Bromsgrove connected to Coventry, and towards Derby. The road southward connected to Tewkesbury and Gloucester.

There had been a bridge in Worcester since at least the 11th century; it was replaced in the early 14th century. This bridge, situated below the current Newport Street, had six arches on piers with starlings

Starlings are small to medium-sized passerine birds in the family Sturnidae. The Sturnidae are named for the genus '' Sturnus'', which in turn comes from the Latin word for starling, ''sturnus''. Many Asian species, particularly the larger ones, ...

, and the middle pier had a gatehouse.

The city walls' upkeep was paid for by the residents. The walls included bastions and a watercourse. The course of the wall was fairly irregular. The entrances to the city were through defensive gates, constructed at different times, including St. Martin's Gate in the east, Sidbury Gate to the south, Friar Gate, Edgar Tower and Water Gate; there were six gates by the 16th century.

Worcester was also a centre of medieval religious life; there were several monasteries until the dissolution. These included the

Worcester was also a centre of medieval religious life; there were several monasteries until the dissolution. These included the Greyfriars Greyfriars, Grayfriars or Gray Friars is a term for Franciscan Order of Friars Minor, in particular, the Conventual Franciscans. The term often refers to buildings or districts formerly associated with the order.

Former Friaries

* Greyfriars, Bed ...

, Blackfriars, Penitent Sisters and the Benedictine Priory, now Worcester Cathedral. Monastic houses provided hospitals and education, including Worcester School

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Englan ...

. The St. Wulstan Hospital was founded around 1085 and was dissolved with the monasteries in 1540. The St. Oswald Hospital was possibly founded by St Oswald. Substantial lands and property in Worcester were held by the church.

Domesday Book also records a considerable number of town houses belonging to rural landowners, presumably used as residences while selling produce from their lands.

In the 1100s, Worcester suffered a number of city fires. The first was on 19 June 1113, destroying town, castle and cathedral, and the second in November 1131.

The following century, the town (then better defended) was attacked several times (in 1139, 1150 and 1151) during the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legi ...

, i.e. civil war between King Stephen and Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

, daughter of Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the N ...

. The 1139 attack again resulted in fire and destruction of a portion of the city, with citizens being held for ransom.

Another fire in 1189 destroyed much of the city for the fourth time that century.

Worcester received its first royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, b ...

in 1189. This set out the annual payment made to the Crown as £24 per annum, and set out that the city would deal directly with the Crown's Exchequer, rather than through the county sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

, who would no longer have general jurisdiction over the city. However, under King John, Worcester's charter was not renewed, which allowed him to levy increasing and arbitrary taxation (tallage Tallage or talliage (from the French ''tailler, i.e. '' a part cut out of the whole) may have signified at first any tax, but became in England and France a land use or land tenure tax. Later in England it was further limited to assessments by the ...

) on Worcester.

King John made eleven visits to Worcester, including at his first Easter as King in 1200. Wulstan was made a saint in 1203, and John visited his shrine in 1207. He appears to have developed an attachment to Wulstan's cult because he appeared to support the authority of kings.

John attempted to claim the right to appoint English bishops, which led him into a long dispute with the Pope. Bishop Mauger of Worcester

Mauger was a medieval Bishop of Worcester.

Mauger was archdeacon of Capévreux and a royal clerk and physician before he was elected to the see of Worcester before 23 August 1199. His election, however, was quashed by Pope Innocent III because M ...

was appointed by the Pope to enforce his Interdict, alongside the Bishops of London and Ely. He was forced into exile and his possessions confiscated as a result.

John spent Christmas 1214 at Worcester, During his disputes with the Barons over the administration of justice, before returning to London where discussions leading to Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

began. In 1216, the barons asked the French Dauphin to depose John. This brought conflict to Worcestershire, where the county 's leaders organised against him, and allowed William Marshall, son of the Earl of Pembroke, who was loyal to John, to take possession of Worcester as governor. Ranulph, Earl of Chester attacked the city, took the castle and ransacked the Cathedral, where the garrison had attempted to take shelter. Marshal was warned of the attack by his father, and was able to escape.

The Priory was fined for protecting the rebels and were forced to melt down the treasures used to adorn St Wulfstan's tomb. The city of Worcester was fined £100 for its role; the lack of a Charter for the city enabled this arbitrary payment to be levied.

John was buried in the cathedral near Wulfstan's altar after he died.

In 1227, under King Henry III Worcester regained its charter and was granted more freedoms. The annual tax was increased to £30. The sheriff was again removed from his role representing the city to the Crown, except in some limited circumstances. A guild of merchants was created, creating a trading monopoly for those admitted. Villein

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

s who resided in the city for a year and day, and were members of the guild, were to be deemed free. Finally, the charter granted rights to levy tolls and taxation, and exemption from certain duties and taxes otherwise due to the Crown. The charter was renewed in 1264.

Worcester's institutions grew at a slower pace than most county towns and had detectably archaic echoes. It is likely that this is related to the power of the local aristocracy.

Jewish life, persecution and expulsions

Worcester had a smallJewish population

As of 2020, the world's "core" Jewish population (those identifying as Jews above all else) was estimated at 15 million, 0.2% of the 8 billion worldwide population. This number rises to 18 million with the addition of the "connected" Jewish pop ...

by the late 12th century. It was one of a number of places allowed to keep records of debts, in an official locked chest known as an archa. (An archa or arca (plural archae/arcae) was a municipal chest in which deeds were preserved.) Jewish life probably centred around what is now Copenhagen Street.

The Diocese was notably hostile to the Jewish community in Worcester. Peter of Blois

Peter of Blois ( la, Petrus Blesensis; French: ''Pierre de Blois''; ) was a French cleric, theologian, poet and diplomat. He is particularly noted for his corpus of Latin letters.

Early life and education

Peter of Blois was born about 1130. Ear ...

was commissioned by a Bishop of Worcester, probably John of Coutances

John of Coutances was a medieval Bishop of Worcester.

John was a nephew of Walter of Coutances, Bishop of Lincoln and was treasurer of the diocese of Lisieux before his uncle appointed him Archdeacon of Oxford sometime before December 1184. He al ...

, to write a significant anti-Judaic treatise ''Against the Perfidy of Jews'' around 1190.

William de Blois, as Bishop of Worcester, imposed particularly strict rules on Jews within the diocese in 1219. As elsewhere in England, Jews were officially compelled to wear square white badges, supposedly representing tabulae. In most places, this requirement was relinquished as long as fines were paid. In addition to enforcing the church laws on wearing badges, Blois tried to impose additional restrictions on usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is c ...

, and wrote to Pope Gregory in 1229 to ask for better enforcement and further, harsher measures. In response, the Papacy demanded that Christians be prevented from working in Jewish homes, "lest temporal profit be preferred to the zeal of Christ", and enforcement of the wearing of badges.

A national assembly of Jewish notables was summoned to Worcester by the Crown in 1240 to assess their wealth for taxation; at which Henry III "squeezed the largest tallage of the thirteenth century from his Jewish subjects."

In 1263 Worcester's Jewish residents were attacked by a baronial force led by Robert Earl Ferrers and Henry de Montfort. Most were killed. Ferrers used this opportunity to remove the titles to his debts by taking the archae.

The massacre in Worcester was part of a wider campaign by the De Montforts and their allies in the run up to the Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in England between the forces of a number of barons led by Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of King Henry III, led initially by the king himself and later by his son, the fu ...

, aimed at undermining Henry III. Simon de Montfort

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester ( – 4 August 1265), later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was a nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the ...

had previously been engaged in a campaign

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

*Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* Bl ...

of persecution of Jewish communities in Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

. A massacre of London's Jewry also took place during the war.

A few years later, in 1275, those still remaining in Worcester were forced to move to Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester, England, Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. ...

, as Jews were expelled from towns under the jurisdiction of the queen mother.

Evolution of craft guilds

Through the medieval and early modern period, Worcester developed a system of craftguild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

s. Guilds regulated who could work in a trade, trade practices and training, and provided social support for members.

The city's late medieval ordinances banned tilers from forming a guild, and encouraged tilers to settle in Worcester to trade freely. Roofs of thatch and wooden chimneys were banned in order to reduce fire risks.

Late medieval

Worcester's Ordinances of the sixth year of Edward IV, renewed in 1496–7, and detailed in 82 clauses, give a detailed picture of life and city organisation in the latemedieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

period. They were to be enforced by the city's bailiffs. Chamberlains received and accounted for rents and other income and the use of common lands within Worcester was set out. Trade regulations covered bread and ale. Others dealt with sanitation, fire regulations and upkeep of the city wall, quays and pavements. Public order and crimes including affray are covered. Citizens were given the privilege of being imprisoned underneath the Guildhall rather than in the town jail, except for the most serious offences.

The cloth industry was also regulated by the Ordinances. Apart from regulation of weights and measures, the ordinances also attempted to protect the artisans engaged in the trade. Payment in kind was banned, with fines of 20 shillings for anyone making payment other than with gold and silver. People were only to be employed if they lived in the city and its suburbs.

Worcester elected members of Parliament at the Guildhall, by males "of suche as hev dwellynge wtin the ffraunches and by the moste voice." That is, by shouting. Members of Parliament had to own freehold property worth 40 shillings a year, and be "of good name and fame, not outlawed, not acombred in accyons as nygh as men may knowe, for worshipp of the seid cite". Their wages were levied by the Constable.

The ordinances also mandated that the then-neglected pageants of the crafts take place five times a year, and set out a few general rules for newcomers expecting to set up their trade in the city. A master craftsman was obliged to make customary payments to the wardens of the craft. A journeyman would after a fortnight have to pay dues to the wardens.

The city council was organised by a system of co-option. There were 24 members of the high chamber, and 48 of the lower chamber. Committees appointed the two Bailiffs and made financial decisions, while the two chambers agreed the city's rules, or ordinances.

By late medieval times the population had grown to 1,025 families, excluding the cathedral quarter, so probably stood under 10,000. Worcester had grown beyond the limits of its walls with a number of suburbs.

The manufacture of cloth and allied trades started to become a large local industry. For instance, Leland stated in the mid 1500s that "The welthe of the towne of Worcestar standithe most by draping, and noe towne of England, at this present tyme, maketh so many cloathes yearly as this towne doth."

The glove-making trade has its roots in this period.

Early modern

The Dissolution saw the Priory's status change, as it lost its Benedictine monks. There were around 36 monks plus the Prior at dissolution in 1540 and some 16 were given pensions immediately or soon after, the rest being employed in the new Deanery. It was necessary to establish 'public schools' to replace monastic education in Worcester as elsewhere. This led to the establishment of King's School. Worcester School continued to teach. St Oswald's Hospital survived the dissolution, later providing

The Dissolution saw the Priory's status change, as it lost its Benedictine monks. There were around 36 monks plus the Prior at dissolution in 1540 and some 16 were given pensions immediately or soon after, the rest being employed in the new Deanery. It was necessary to establish 'public schools' to replace monastic education in Worcester as elsewhere. This led to the establishment of King's School. Worcester School continued to teach. St Oswald's Hospital survived the dissolution, later providing almshouses

An almshouse (also known as a bede-house, poorhouse, or hospital) was charitable housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the medieval era. They were often targeted at the poor of a locality, at those from certai ...

; the charity and its housing survives to the present.

The city was given the right to elect a Mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

and was designated a county corporate

A county corporate or corporate county was a type of subnational division used for local government in England, Wales, and Ireland.

Counties corporate were created during the Middle Ages, and were effectively small self-governing county-empo ...

in 1621, giving it autonomy from local government. From this point, Worcester was governed by a mayor, recorder and six aldermen. Councillors were selected through co-option.

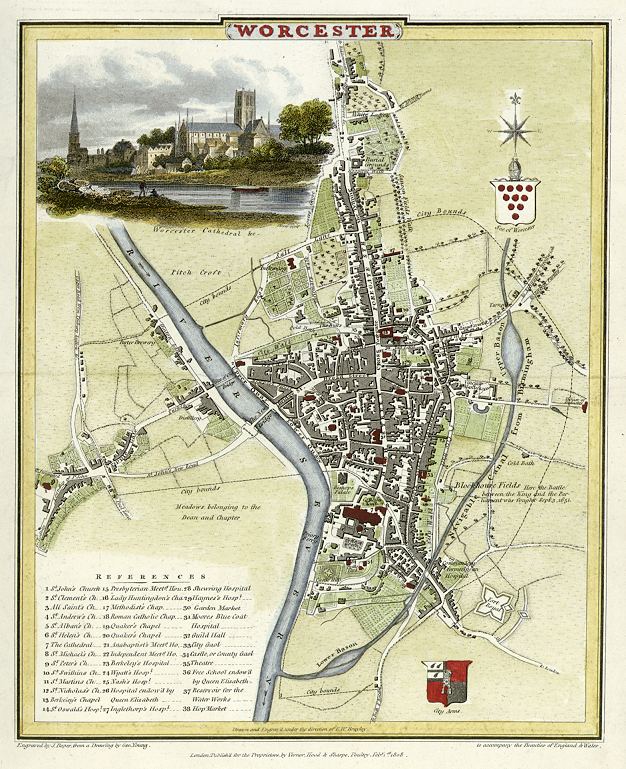

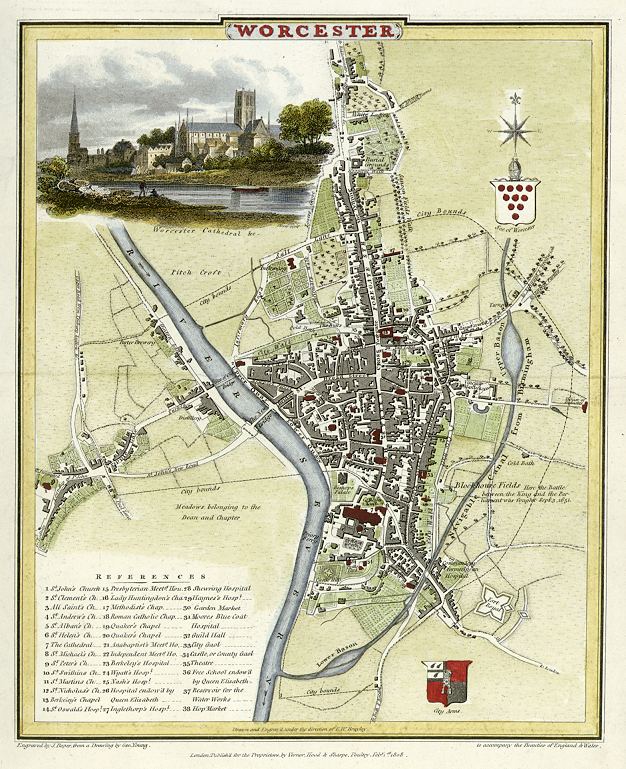

Worcester in this period contained green spaces such as orchards and fields between its main streets within the city wall boundary, as evidenced by Speed's map of 1610. The walls were still more or less complete at this time, but suburbs had also been established beyond them.

Civil War

Worcester equivocated about whether to support the Parliamentary cause before the outbreak of

Worcester equivocated about whether to support the Parliamentary cause before the outbreak of civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

in 1642, eventually siding with Parliament. The city was swiftly occupied by the Royalists, who billeted their troops in the city and used the cathedral to store munitions. Essex

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

briefly retook the city for Parliament after the skirmish at the Battle of Powick Bridge

The Battle of Powick Bridge was a skirmish fought on 23 September 1642 just south of Worcester, England, during the First English Civil War. It was the first engagement between elements of the principal field armies of the Royalists and Parli ...

, the first engagement of the war. Parliamentary troops then ransacked the cathedral building. Stained glass was smashed and the organ destroyed, along with library books and monuments. Essex was soon forced to withdraw, after the Battle of Edgehill

The Battle of Edgehill (or Edge Hill) was a pitched battle of the First English Civil War. It was fought near Edge Hill and Kineton in southern Warwickshire on Sunday, 23 October 1642.

All attempts at constitutional compromise between ...

.

The city spent the rest of the First Civil War Royalist control, as did the county, for the most part. Worcester was a garrison town with a Royalist governor), and had to bear high taxation for of sustaining and billeting a large number of Royalist troops. The city walls

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates ...

which were in a lamentable state at the start of the war were strengthened, and houses close to the walls were demolished by Worcester women after the first siege in 1643 to give the defenders a clear field of fire.

As Royalist power collapsed in May 1646, Worcester was placed under siege for the second time. Worcester had around 5,000 civilians, together with a Royalist garrison of around 1,500 men, facing a 2,500-5,000 strong force of the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

. Worcester finally surrendered on 23 July, bringing the first civil war to a close in Worcestershire.

In 1651 a Scottish army, 16,000 strong, marched south along the west coast in support of Charles II's attempt to regain the Crown. When the army approached, Worcester's council voted to surrender, fearing further violence and destruction. The Parliamentary garrison withdrew to Evesham

Evesham () is a market town and parish in the Wychavon district of Worcestershire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is located roughly equidistant between Worcester, Cheltenham and Stratford-upon-Avon. It lies within the Vale of Eves ...

in the face of the overwhelming numbers against them. The Scots were billeted in and around the city, again at great expense and causing new anxiety for the residents. The Scots were joined by very limited local forces, including a company of 60 men under Francis Talbot.

The Battle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 in and around the city of Worcester, England and was the last major battle of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Parliamentarian army of around 28,000 under Oliver Cromwell d ...

(3 September 1651), took place in the fields a little to the west and south of the city, near the village of Powick

Powick is a village and civil parish in the Malvern Hills district of Worcestershire, England, located two miles south of the city of Worcester and four miles north of Great Malvern. The parish includes the village of Callow End and the hamlet ...

. Charles II was easily defeated by Cromwell's forces of 30,000 men. Charles II returned to his headquarters in what is now known as King Charles House in the Cornmarket, before fleeing in disguise with Talbot's help to Boscobel House

Boscobel House () is a Grade II* listed building in the parish of Boscobel in Shropshire. It has been, at various times, a farmhouse, a hunting lodge, and a holiday home; but it is most famous for its role in the escape of Charles II after the B ...

in Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

, from where he eventually escaped to France.

In the aftermath of the battle, Worcester was heavily looted by the Parliamentarian army, with an estimated £80,000 of damage done. Around 10,000 prisoners, mostly Scots, were held captive, and either sent to work on the Fens drainage projects, or transported to the New World.

From 1646 to 1660, the bishopric was abolished and the cathedral fell into disrepair.

After the Restoration

After the Restoration in 1660, Worcester cleverly used its location as the site of the final battles of the First Civil War (1646) and Third Civil War (1651) to mount an appeal for compensation from the new King Charles II. As part of this and not based upon any historical fact, it invented the epithet ''Fidelis Civitas'' (The Faithful City) and this motto has since been incorporated into the city'scoat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its ...

.

Around 1690, a news-sheet that started publication, which later became known as one of the oldest newspapers in the world, ''Berrow's Worcester Journal

''Berrow's Worcester Journal'' is a weekly freesheet tabloid newspaper, based in Worcester, England. Owned by Newsquest, the newspaper is delivered across central and southern Worcestershire county.

History

16th Century Printing Press

Worces ...

''.

Worcester Guildhall was rebuilt in 1721, replacing the earlier hall on the same site. The now

Worcester Guildhall was rebuilt in 1721, replacing the earlier hall on the same site. The now Grade I listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

Queen Anne style building was described by Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, '' The Buildings of England'' ...

as "a splendid town hall, as splendid as any of C18 England".

Worcester's historic bridge was replaced, at a cost of £29,843 including its approaches, opening on 17 September 1781. As the town's population expanded, the green areas between the main streets filled with housing and back streets. Nevertheless, the size of the city and suburbs was roughly the same as it was in the early 1600s. Large stretches of the walls of the city had been removed by 1796.

The Royal Worcester Porcelain Company factory was founded by Dr John Wall in 1751.

Industrial revolution, Victorian and Edwardian eras

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Worcester was a major centre for glove-making, employing nearly half the glovers in England at its peak (over 30,000 people). In 1815 the

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Worcester was a major centre for glove-making, employing nearly half the glovers in England at its peak (over 30,000 people). In 1815 the Worcester and Birmingham Canal

The Worcester and Birmingham Canal is a canal linking Birmingham and Worcester in England. It starts in Worcester, as an 'offshoot' of the River Severn (just after the river lock) and ends in Gas Street Basin in Birmingham. It is long.

There a ...

opened, allowing Worcester goods to be transported to a larger conurbation.

Later in that century the industry declined after import taxes on foreign competitors, mainly from France, were greatly reduced.

Riots took place in 1831, in response to the defeat of the Reform Bill

In the United Kingdom, Reform Act is most commonly used for legislation passed in the 19th century and early 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. ...

, reflecting discontent with the city administration and the wider lack of democratic representation. Riots occurred elsewhere, including Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

. Local government reform took place in 1835, which for the first time created election procedures for councillors, but also restricted the ability of the city to buy and sell property, requiring Treasury permission. Until that year, the legal distinction between a select group of citizens with specific privileges and other residents of the town had survived.

Political troubles continued throughout the Victorian and Edwardian period, with Worcester becoming notorious for corrupt political practices. Through the period, attempts were made to reduce and eliminate electoral bribery through national legislation. As the franchise widened, attempts to fix elections through bribes, fake employment in campaigns and gifts of beer became very expensive, making it politically preferable to crack down on them. Nevertheless, such practices persisted in Worcester, allowing Worcester to retain Conservative representation in 1892 against a Liberal landslide, leading to investigations being made. A Royal Commission in 1906 finally found that around 500 men on low incomes regarded the purchase of their vote as something they should expect as of right, and a welcome addition to their subsistence. The campaign by liberals to end electoral corruption was not welcomed, and led to underperformance by that party for many years.

The British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. The association does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The association's headqua ...

(BMA) was founded in the Board Room of the old Worcester Royal Infirmary building in Castle Street in 1832.

Lea & Perrins

Lea & Perrins (L&P) is a United Kingdom-based subsidiary of Kraft Heinz, originating in Worcester, England where it continues to operate. It is best known as the maker of Lea & Perrins brand of Worcestershire sauce, which was first sold in 183 ...

Worcestershire sauce has been made and bottled in Worcester since around 1837, first produced by two chemists, it is claimed according to a recipe supplied by an unnamed "Nobleman of the County". Production expanded, and a new factory was opened at the Midland Road on 16 October 1897, which accommodated exports to the USA.  Railways came to Worcester in 1850, with the opening Shrub Hill station, jointly owned by the

Railways came to Worcester in 1850, with the opening Shrub Hill station, jointly owned by the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway

The Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway (OW&WR) was a railway company in England. It built a line from Wolvercot JunctionThe nearby settlement is spelt ''Wolvercote'' and a later station on the LNWR Bicester line follows that spelling. ...

and the Midland Railway

The Midland Railway (MR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1844. The Midland was one of the largest railway companies in Britain in the early 20th century, and the largest employer in Derby, where it had its headquarters. It ama ...

, initially running to Birmingham only. Foregate Street was opened in 1860 by the Hereford and Worcester Railway, quickly incorporated into the West Midland Railway

The West Midland Railway was an early British railway company. It was formed on 1 July 1860 by a merger of several older railway companies and amalgamated with the Great Western Railway on 1 August 1863. It was the successor to the Oxford, Worc ...

. The WMR lines became part of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

after 1 August 1863. The railways also gave Worcester thousands of jobs with just under half of all GWR passenger coaches built in Worcester and the three signalling factories including the largest railway signalling

Railway signalling (), also called railroad signaling (), is a system used to control the movement of railway traffic. Trains move on fixed rails, making them uniquely susceptible to collision. This susceptibility is exacerbated by the enormo ...

company in the World: McKenzie & Holland

Vulcan Iron Works was the name of several iron foundries in both England and the United States during the Industrial Revolution and, in one case, lasting until the mid-20th century. Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and smithery, was a popular n ...

.

In 1882 Worcester hosted the Worcestershire Exhibition, inspired by the earlier Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition which took pl ...

in London. There were sections for exhibits of fine arts (over 600 paintings), historical manuscripts and industrial items. The profit was £1,867.9s.6d and the number of visitors is recorded as 222,807. Some of the profit from the exhibition was used to build the Victoria Institute in Foregate Street, Worcester, which opened on 1 October 1896 and originally housed the city art gallery and museum.

The late-Victorian period saw the growth of ironfounders, including Heenan & Froude

Heenan & Froude was a United Kingdom-based engineering company, founded in Newton Heath, Manchester, England in 1881 in a partnership formed by engineers Richard Froude and Richard Hammersley Heenan. Expanded on the back of William Froude's pat ...

, Hardy & Padmore and McKenzie & Holland.

1914 to present

Worcester was a centre for recruitment of soldiers to fight in theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, into the Worcestershire Regiment, which was based at Norton Barracks

Norton Barracks is a military installation in Norton, Worcestershire. The keep is a Grade II listed building.

History

The barracks were built in the Fortress Gothic Revival Style between 1874 and 1877. Their creation took place as part of the C ...

. The regiment took part in early battles in the war, most notably at the Battle of Gheluvelt

The First Battle of Ypres (french: Première Bataille des Flandres; german: Erste Flandernschlacht – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the Firs ...

in October 1914, which prevented the German army from reaching Belgian ports.

The newly-appointed Vicar of St Paul's, Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy

Geoffrey Anketell Studdert Kennedy (27 June 1883 – 8 March 1929) was an English Anglican priest and poet. He was nicknamed "Woodbine Willie" during World War I for giving Woodbine cigarettes to the soldiers he met, as well as spiritual aid t ...

, was among those urging Worcester's men to enlist. He became an army chaplain, later known as 'Woodbine Willy', as he brought cigarettes to soldiers during fighting and exposed himself to physical danger, earning him a Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC ...

. Shops in Worcester organised collections to supply him with cigarettes. His experience of war ushed him towards pacifism and Christian Socialism

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe capi ...

. After the war, he left his Worcester parish, but kept a house in the city for the rest of his life.

Rail reorganisation in 1922 saw the Midland Railway's routes from Shrub Hill absorbed into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway

The London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMSIt has been argued that the initials LMSR should be used to be consistent with LNER, GWR and SR. The London, Midland and Scottish Railway's corporate image used LMS, and this is what is generally ...

.

The inter-war years saw the rapid growth of engineering, producing machine tools (James Archdale, H.W. Ward), castings for the motor industry (Worcester Windshields and Casements), mining machinery (Mining Engineering Company which later became part of Joy Mining Machinery) and open-top cans( Williamsons, though G H Williamson and Sons had become part of the Metal Box Co in 1930); later the company became Carnaud Metal Box plc).

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the city was chosen to be the seat of an evacuated government in case of mass German invasion German invasion may refer to:

Pre-1900s

* German invasion of Hungary (1063)

World War I

* German invasion of Belgium (1914)

* German invasion of Luxembourg (1914)

World War II

* Invasion of Poland

* German invasion of Belgium (1940)

* G ...

. The War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senio ...

, along with Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

and some 16,000 state workers, would have moved to Hindlip Hall (now part of the complex forming the Headquarters of West Mercia Police

West Mercia Police (), formerly the West Mercia Constabulary, is the territorial police force responsible for policing the counties of Herefordshire, Shropshire (including Telford and Wrekin) and Worcestershire in England. The force area cove ...

), north of Worcester and Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

would have temporarily seated in Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon (), commonly known as just Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-we ...

. The former RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

station RAF Worcester

Royal Air Force Worcester, or more simply RAF Worcester, is a former Royal Air Force relief landing ground (RLG) which was located north east of Worcester city centre, Worcestershire, England and south west of Droitwich Spa, Worcestershire ...

was located east of Northwick.

A fuel storage depot was constructed in 1941-2 by Shell Mex & BP (later operated by Texaco) for the government on the eastern bank of the River Severn, about one mile south of Worcester. There were six 4,000 ton semi-buried tanks for the storage of white oils. It had no rail or road loading facilities but distribution could be carried out by barge through the Diglis basin and the depot could receive fuel either by barge or the GPSS pipeline network. It was at one time used as a civil reserve storing gas oil and then stored aviation kerosene for USAFE. In the early 1990s it was closed down and the site was sold for housing in the 2000s.

By the middle of the 20th century, only a few Worcester gloving companies survived since gloves became less fashionable and free trade allowed in cheaper imports from the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The t ...

. Nevertheless, at least three large glove manufacturing companies survived until the late 20th century: Dent Allcroft, Fownes and Milore. Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states durin ...

's coronation gloves were designed and manufactured in the Worcester-based Dent Allcroft & Co. factory.

In the 1950s and 1960s large areas of the medieval centre of Worcester were demolished and rebuilt as a result of decisions by town planners. This was condemned by many such as Pevsner who described it as a "totally incomprehensible... act of self-mutilation". There is still a significant area of medieval Worcester remaining, examples of which can be seen along City Walls Road, Friar Street and New Street, but it is a small fraction of what was present before the redevelopments.

The current city boundaries date from 1974, when the Local Government Act 1972

The Local Government Act 1972 (c. 70) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974. It was one of the most significant Acts of Parliament to be passed by the Heath Gov ...

transferred the parishes of Warndon

Warndon is a suburb and civil parish of the City of Worcester in Worcestershire, England.

The parish, which includes the villages of Trotshill and Warndon was part of Droitwich Rural District until 1974 when it was annexed to Worcester under t ...

and St. Peter the Great County

St Peter the Great or St Peter's is a suburb in the civil parish of St. Peter the Great County, in the city of Worcester, in the county of Worcestershire, England. It is south of the city centre, on the east side of the River Severn, near Junctio ...

into the city.

Worcester Porcelain closed down in 2009 due to the recession. The site of the factory still houses the Museum of Royal Worcester

The Museum of Royal Worcester (formerly ''Worcester Porcelain Museum'' and ''Dyson Perrins Museum'') is a ceramics museum located in the Royal Worcester porcelain factory's former site in Worcester, England.

Overview

The museum houses the wo ...

. and handful of decorators are still employed at the factory. Since 2015 there has been extensive re-development of the quarter, entirely devoted to housing.

While part of the Royal Infirmary hospital was demolished to make way for the University of Worcester

, motto_lang = la

, mottoeng = ''Aspire to Inspire''

, established = 1946 – Worcester Emergency Teacher Training College 1948 – Worcester Teacher Training College 1976 – Worcester College of Higher Education 1997 – ...

's new city campus, the original Georgian building has been preserved. One of the old wards opened as a medical museum, the Infirmary, in 2012.

The foundry heritage of the city is represented by Morganite Crucible at Norton which produces graphitic shaped products and cements for use in the modern industry.

The city is home to the European manufacturing plant of Yamazaki Mazak Corporation

is a Japanese machine tool builder based in Oguchi, Japan. In the United States, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country ...

, a global Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

ese machine tool builder A machine tool builder is a corporation or person that builds machine tools, usually for sale to manufacturers, who use them to manufacture products. A machine tool builder runs a machine factory, which is part of the machine industry.

The machin ...

, which was established in 1980.

Images

See also

* List of Bishops of Worcester *Worcester City Art Gallery & Museum

The Worcester City Art Gallery & Museum is an art gallery and local museum in Worcester, the county town of Worcestershire, England.

History

The museum was founded in 1833 by members of the Worcestershire Natural History Society. It is locate ...

*Jewish Community of Worcester

During the Middle Ages there was a small Jewish community in Worcester, a city and county town of Worcestershire in the West Midlands of England that mainly provided money lending services to the non-Jewish citizens. Worcester also hosted a nati ...

Notes

Explanatory citations

Citations

References

General

* * * * * * * * * * * *Medieval history

* * * * *Civil War

* *Twentieth century

* *Further reading

* * * * *External links

History of the City of Worcester

* {{Authority control