History of Tanzania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Tanzania is home to some of the oldest

Tanzania is home to some of the oldest

In 1954,

In 1954,

Background Note: Tanzania

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Tanzania

African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes ( sw, Maziwa Makuu; rw, Ibiyaga bigari) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. They include Lake Victoria, the second-largest fresh water lake in th ...

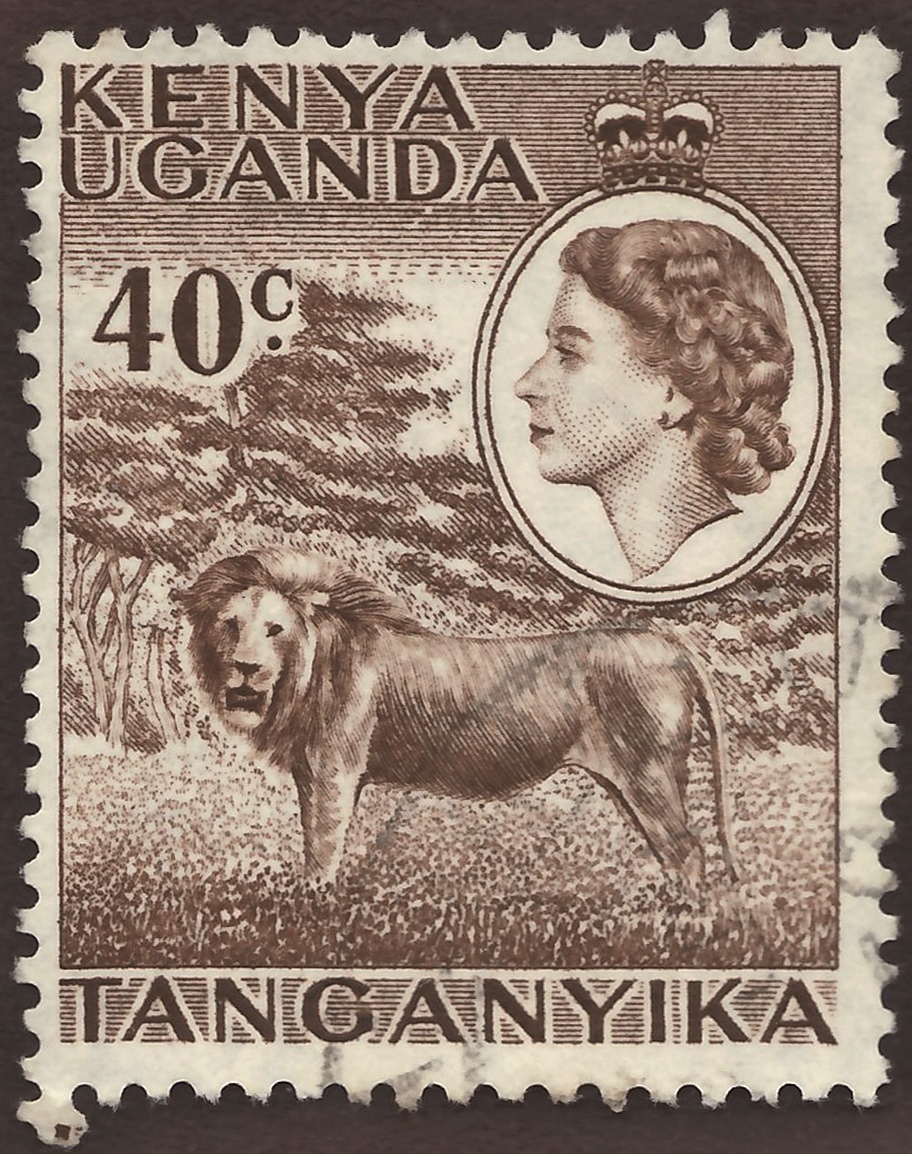

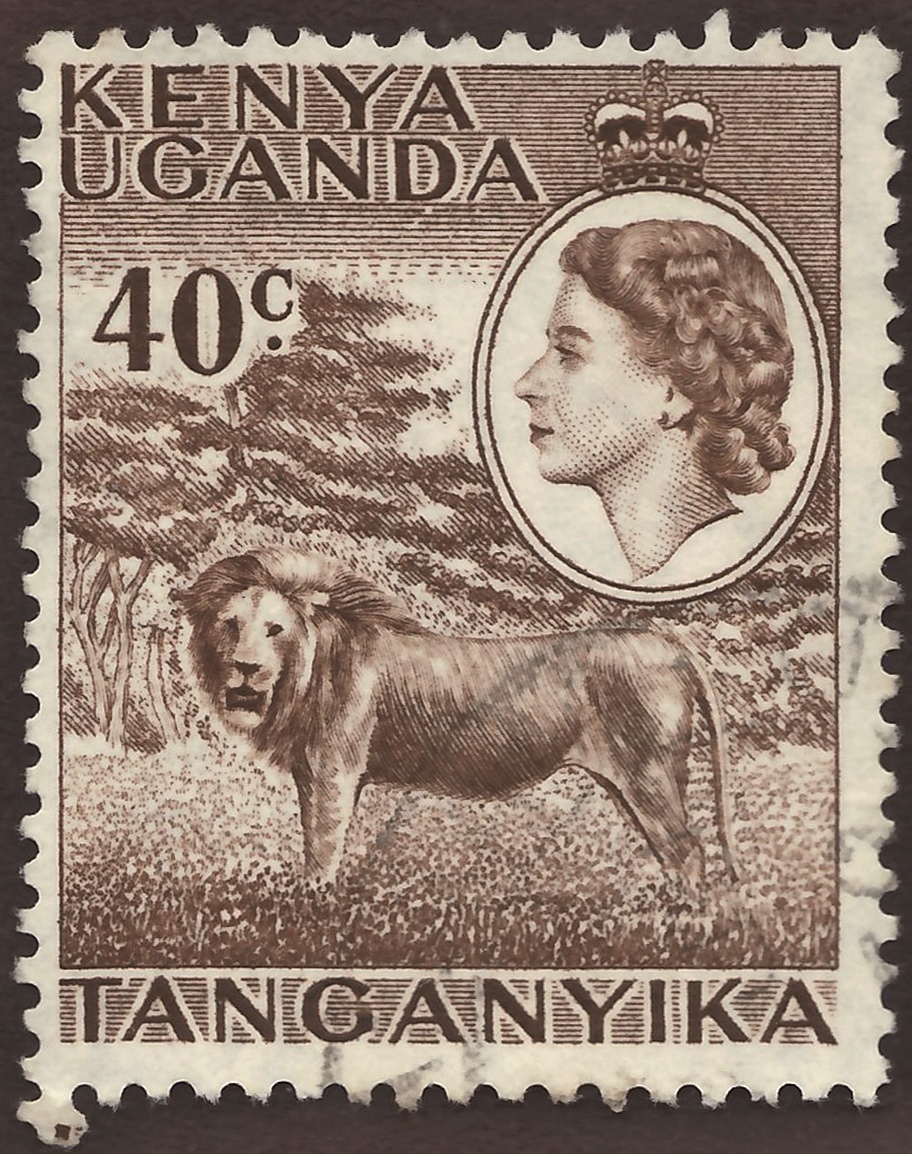

nation of Tanzania dates formally from 1964, when it was formed out of the union of the much larger mainland territory of Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

and the coastal archipelago of Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

. The former was a colony and part of German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mo ...

from the 1880s to 1919’s when, under the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

, it became a British mandate

Mandate most often refers to:

* League of Nations mandates, quasi-colonial territories established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 June 1919

* Mandate (politics), the power granted by an electorate

Mandate may also r ...

. It served as a British military outpost during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, providing financial help, munitions, and soldiers. In 1947, Tanganyika became a United Nations Trust Territory

United Nations trust territories were the successors of the remaining League of Nations mandates and came into being when the League of Nations ceased to exist in 1946. All of the trust territories were administered through the United Nati ...

under British administration, a status it kept until its independence in 1961. The island of Zanzibar thrived as a trading hub, successively controlled by the Portuguese, the Sultanate of Oman, and then as a British protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

by the end of the nineteenth century.

Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, af ...

, independence leader and "baba wa taifa" for Tanganyika (father of the Tanganyika nation), ruled the country for decades, while Abeid Amaan Karume, governed Zanzibar as its president and Vice President of the United Republic of Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

. Following Nyerere's retirement in 1985, various political and economic reforms began. He was succeeded in office by President Ali Hassan Mwinyi

Ali Hassan Mwinyi (born 8 May 1925) is a Tanzanian politician, who served as the second President of the United Republic of Tanzania from 1985 to 1995.

Previous posts include Interior Minister and Vice President. He also was chairman of the ru ...

.

Prehistory

Early Stone Age

Tanzania is home to some of the oldest

Tanzania is home to some of the oldest hominid

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

settlements unearthed by archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscapes ...

. Prehistoric stone tools and fossils have been found in and around Olduvai Gorge

The Olduvai Gorge or Oldupai Gorge in Tanzania is one of the most important paleoanthropological localities in the world; the many sites exposed by the gorge have proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution. A steep-si ...

in northern Tanzania, an area often referred to as "The Cradle of Mankind". Acheulian

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

stone tools were discovered there in 1931 by Louis Leakey

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (7 August 1903 – 1 October 1972) was a Kenyan-British palaeoanthropologist and archaeologist whose work was important in demonstrating that humans evolved in Africa, particularly through discoveries made at Olduvai ...

, after he had correctly identified the rocks brought back by Hans Reck

Hans Gottfried Reck (24 January 1886 – 4 August 1937) was a German volcanologist and paleontologist.

In 1913 he was the first to discover an ancient skeleton of a human in the Olduvai Gorge, in what is now Tanzania.

He collaborated with ...

to Germany from his 1913 Olduvai expedition as stone tools. The same year, Louis Leakey found older, more primitive stone tools in Olduvai Gorge. These were the first examples of the oldest human technology ever discovered in Africa, and were subsequently known throughout the world as Oldowan

The Oldowan (or Mode I) was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower ...

after Olduvai Gorge.

The first hominid skull in Olduvai Gorge was discovered by Mary Leakey

Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA (née Nicol, 6 February 1913 – 9 December 1996) was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised ''Proconsul'' skull, an extinct ape which is now believed to be ancestral to humans. She also disc ...

in 1959, and named Zinj or Nutcracker Man, the first example of ''Paranthropus boisei

''Paranthropus boisei'' is a species of australopithecine from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2.5 to 1.15 million years ago. The holotype specimen, OH 5, was discovered by palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey in 1959, and described by ...

'', and is thought to be more than 1.8 million years old. Other finds including ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly ...

'' fossils were subsequently made. At nearby Laetoli

Laetoli is a pre-historic site located in Enduleni ward of Ngorongoro District in Arusha Region, Tanzania. The site is dated to the Plio-Pleistocene and famous for its Hominina footprints, preserved in volcanic ash. The site of the Laetoli fo ...

the oldest known hominid footprints, the Laetoli footprints, were discovered by Mary Leakey

Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA (née Nicol, 6 February 1913 – 9 December 1996) was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised ''Proconsul'' skull, an extinct ape which is now believed to be ancestral to humans. She also disc ...

in 1978, and estimated to be approximately 3.6 million years old and probably made by ''Australopithecus afarensis

''Australopithecus afarensis'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived from about 3.9–2.9 million years ago (mya) in the Pliocene of East Africa. The first fossils were discovered in the 1930s, but major fossil finds would no ...

''. The oldest hominid fossils ever discovered in Tanzania also come from Laetoli and are the 3.6 to 3.8 million year old remains of ''Australopithecus afarensis

''Australopithecus afarensis'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived from about 3.9–2.9 million years ago (mya) in the Pliocene of East Africa. The first fossils were discovered in the 1930s, but major fossil finds would no ...

''—Louis Leakey

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (7 August 1903 – 1 October 1972) was a Kenyan-British palaeoanthropologist and archaeologist whose work was important in demonstrating that humans evolved in Africa, particularly through discoveries made at Olduvai ...

had found what he thought was a baboon tooth at Laetoli in 1935 (which was not identified as afarensis until 1979), a fragment of hominid jaw with three teeth was found there by Kohl-Larsen in 1938–39, and in 1974–75 Mary Leakey

Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA (née Nicol, 6 February 1913 – 9 December 1996) was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised ''Proconsul'' skull, an extinct ape which is now believed to be ancestral to humans. She also disc ...

recovered 42 teeth and several jawbones from the site.

Middle Stone Age

Mumba Cave in northern Tanzania includes aMiddle Stone Age

The Middle Stone Age (or MSA) was a period of African prehistory between the Early Stone Age and the Late Stone Age. It is generally considered to have begun around 280,000 years ago and ended around 50–25,000 years ago. The beginnings of ...

(MSA) to Later Stone Age

The Later Stone Age (LSA) is a period in African prehistory that follows the Middle Stone Age.

The Later Stone Age is associated with the advent of modern human behavior in Africa, although definitions of this concept and means of studying it ...

(LSA) archaeological sequence. The MSA represents the time period in Africa during which many archaeologists see the origins of modern human behavior

Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current ''Homo sapiens'' from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterized by ...

.

Later Stone Age and Pastoral Neolithic

Reaching back approximately 10,000 years in theLater Stone Age

The Later Stone Age (LSA) is a period in African prehistory that follows the Middle Stone Age.

The Later Stone Age is associated with the advent of modern human behavior in Africa, although definitions of this concept and means of studying it ...

, Tanzania is believed to have been populated by hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

communities, probably Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

-speaking people. Between approximately 4,000 to 3,000 years ago, during a time period known as the Pastoral Neolithic

The Pastoral Neolithic (5000 BP - 1200 BP) refers to a period in Africa's prehistory, specifically Tanzania and Kenya, marking the beginning of food production, livestock domestication, and pottery use in the region following the Later Stone Age. ...

, pastoralists who relied on cattle, sheep, goats, and donkeys came into Tanzania from the north. Two archaeological cultures are known from this time period, the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic

The Savanna Pastoral Neolithic (SPN; formerly known as the Stone Bowl Culture) is a collection of ancient societies that appeared in the Rift Valley of East Africa and surrounding areas during a time period known as the Pastoral Neolithic. The ...

(whose peoples may have spoken a Southern Cushitic language) and the Elmenteitan

The Elmenteitan culture was a prehistoric lithic industry and pottery tradition with a distinct pattern of land use, hunting and pastoralism that appeared and developed on the western plains of Kenya, East Africa during the Pastoral Neolithic ...

(whose peoples may have spoken a Southern Nilotic language). Luxmanda

Luxmanda is an archaeological site located in the north-central Babati District of Tanzania. It was discovered in 2012. Excavations in the area have identified it as the largest and southernmost settlement site of the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic (S ...

is the largest and southernmost-known Pastoral Neolithic site in Tanzania.

Iron Age

Approximately 2000 years ago, Bantu-speaking people began to arrive from western Africa in a series of migrations collectively referred to as theBantu expansion

The Bantu expansion is a hypothesis about the history of the major series of migrations of the original Proto-Bantu-speaking group, which spread from an original nucleus around Central Africa across much of sub-Saharan Africa. In the process, ...

. These groups brought and developed ironworking skills, agriculture, and new ideas of social and political organization. They absorbed many of the Cushitic

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and the Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As o ...

peoples who had preceded them, as well as most of the remaining Khoisan-speaking inhabitants. Later, Nilotic pastoralists arrived, and continued to immigrate into the area through to the eighteenth century.

One of Tanzania's most important Iron Age archeological sites is Engaruka in the Great Rift Valley

The Great Rift Valley is a series of contiguous geographic trenches, approximately in total length, that runs from Lebanon in Asia to Mozambique in Southeast Africa. While the name continues in some usages, it is rarely used in geology as it ...

, which includes an irrigation and cultivation system.

Early coastal history

Travellers and merchants from the Persian Gulf and Western India have visited the East African coast since early in the first millennium CE. Greek texts such as the ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

The ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' ( grc, Περίπλους τῆς Ἐρυθρᾶς Θαλάσσης, ', modern Greek '), also known by its Latin name as the , is a Greco-Roman periplus written in Koine Greek that describes navigation and ...

'' and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's Geography list a string of market places (emporia) along the coast. Finds of Roman-era coins along the coast confirm the existence of trade, and Ptolomey's Geography refers to a town of Rhapta

Rhapta ( grc, Ῥάπτα and Ῥαπτά) was an emporion said to be on the coast of Southeast Africa, first described in the 1st century CE. Its location has not been firmly identified, although there are a number of plausible candidate sites. ...

as "metropolis" of a political entity called Azania

Azania ( grc, Ἀζανία) is a name that has been applied to various parts of southeastern tropical Africa. In the Roman period and perhaps earlier, the toponym referred to a portion of the Southeast Africa coast extending from northern Kenya ...

. Archaeologists have not yet succeeded in identifying the location of Rhapta, although many believe it lies deeply buried in the silt of the delta of the Rufiji River. A long documentary silence follows these ancient texts, and it is not until Arab geographical treatises were written about the coast that our information resumes.

Remains of those towns' material culture demonstrate that they arose from indigenous roots, not from foreign settlement. And the language that was spoken in them, Swahili (now Tanzania's national language), is a member of the Bantu language family that spread from the northern Kenya coast well before significant Arab presence was felt in the region. By the beginning of the second millennium CE the Swahili towns conducted a thriving trade that linked Africans in the interior with trade partners throughout the Indian Ocean. From c. 1200 to 1500 CE, the town of Kilwa

Kilwa Kisiwani (English: ''Kilwa Island'') is an island, national historic site, and hamlet community located in the township of Kilwa Masoko, the district seat of Kilwa District in the Tanzanian region of Lindi Region in southern Tanzania. Ki ...

, on Tanzania's southern coast, was perhaps the wealthiest and most powerful of these towns, presiding over what some scholars consider the "golden age" of Swahili civilization. In the early 14th century, Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim ...

, a Berber traveller from North Africa, visited Kilwa and proclaimed it one of the best cities in the world. Islam was practised on the Swahili coast as early as the eighth or ninth century CE.

In 1498, Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

explorer Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

became the first known European to reach the African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes ( sw, Maziwa Makuu; rw, Ibiyaga bigari) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. They include Lake Victoria, the second-largest fresh water lake in th ...

coast; he stayed for 32 days. In 1505 the Portuguese captured the island of Zanzibar. Portuguese control lasted until the early eighteenth century, when Arabs from Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

established a foothold in the region. Assisted by Omani Arabs, the indigenous coastal dwellers succeeded in driving the Portuguese from the area north of the Ruvuma River

Ruvuma River, formerly also known as the Rovuma River, is a river in the African Great Lakes region. During the greater part of its course, it forms the border between Tanzania and Mozambique (in Mozambique known as ''Rio Rovuma''). The river is ...

by the early eighteenth century. Claiming the coastal strip, Omani Sultan Seyyid Said

Sayyid Saïd bin Sultan al-Busaidi ( ar, سعيد بن سلطان, , sw, Saïd bin Sultani) (5 June 1791 – 19 October 1856), was Sultan of Muscat and Oman, the fifth ruler of the Busaid dynasty from 1804 to 4 June 1856. His rule commenced fol ...

moved his capital to Zanzibar City

Zanzibar City or Mjini District, often simply referred to as Zanzibar (''Wilaya ya Zanzibar Mjini'' or ''Jiji la Zanzibar'' in Swahili) is one of two administrative districts of Mjini Magharibi Region in Tanzania. The district covers an area of . ...

in 1840. He focused on the island and developed trade routes that stretched as far as Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika () is an African Great Lake. It is the second-oldest freshwater lake in the world, the second-largest by volume, and the second-deepest, in all cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. It is the world's longest freshwater lake. T ...

and Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Co ...

. During this time, Zanzibar became the centre for the Indian Ocean slave trade

The Indian Ocean slave trade, sometimes known as the East African slave trade or Arab slave trade, was multi-directional slave trade and has changed over time. Africans were sent as slaves to the Middle East, to Indian Ocean islands (including Ma ...

. Due to the Arab and Persian domination at this later time, many Europeans misconstrued the nature of Swahili civilization as a product of Arab colonization. However, this misunderstanding has begun to dissipate over the past 40 years as Swahili civilization is becoming recognized as principally African in origin.

Tanganyika (1850–1890)

Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

as a geographical and political entity did not take shape before the period of High Imperialism; its name only came into use after German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mo ...

was transferred to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

as a mandate by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

in 1920. What is referred to here, therefore, is the history of the region that was to become Tanzania. A part of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

region, namely the western shore of Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface area after ...

consisted of many small kingdoms, most notably Karagwe and Buzinza, which were dominated by their more powerful neighbors Rwanda

Rwanda (; rw, u Rwanda ), officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of Central Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator ...

, Burundi

Burundi (, ), officially the Republic of Burundi ( rn, Repuburika y’Uburundi ; Swahili: ''Jamuhuri ya Burundi''; French: ''République du Burundi'' ), is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley at the junction between the African Gr ...

, and Buganda

Buganda is a Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Buganda's Central Region, including the Ugandan capital Kampala. The 14 mi ...

.

European exploration of the interior began in the mid-19th century. In 1848 the German missionary Johannes Rebmann

Johannes Rebmann (January 16, 1820 – October 4, 1876) was a German missionary, linguist, and explorer credited with feats including being the first European, along with his colleague Johann Ludwig Krapf, to enter Africa from the Indian Ocean coa ...

became the first European to see Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It has three volcanic cones: Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world: above sea level and a ...

. British explorers Richard Burton

Richard Burton (; born Richard Walter Jenkins Jr.; 10 November 1925 – 5 August 1984) was a Welsh actor. Noted for his baritone voice, Burton established himself as a formidable Shakespearean actor in the 1950s, and he gave a memorable pe ...

and John Speke crossed the interior to Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika () is an African Great Lake. It is the second-oldest freshwater lake in the world, the second-largest by volume, and the second-deepest, in all cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. It is the world's longest freshwater lake. T ...

in June 1857. In January 1866, the Scottish explorer and missionary David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

, who crusaded against the slave trade, went to Zanzibar, from where he sought the source of the Nile, and established his last mission at Ujiji

Ujiji is a historic town located in Kigoma-Ujiji District of Kigoma Region in Tanzania. The town is the oldest in western Tanzania. In 1900, the population was estimated at 10,000 and in 1967 about 41,000. The site is a registered National His ...

on the shores of Lake Tanganyika. After having lost contact with the outside world for years, he was "found" there on 10 November 1871. Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author and politician who was famous for his exploration of Central Africa and his sear ...

, who had been sent in a publicity stunt to find him by the New York Herald newspaper, greeted him with the now famous words "Dr Livingstone, I presume?" In 1877, the first of a series of Belgian expeditions arrived on Zanzibar. In the course of these expeditions, in 1879 a station was founded in Kigoma on the eastern bank of Lake Tanganyika, soon to be followed by the station of Mpala

Mpala is the location of an early Catholic mission in the Belgian Congo. A military station was established at Mpala on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in May 1883. It was transferred to the White Fathers missionaries in 1885. At one time it was ...

on the opposite western bank. Both stations were founded in the name of the Comite D'Etudes Du Haut Congo, a predecessor organization of the Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leop ...

. German colonial interests were first advanced in 1884. Karl Peters

Carl Peters (27 September 1856 – 10 September 1918), was a German colonial ruler, explorer, politician and author and a major promoter of the establishment of the German colony of East Africa (part of the modern republic Tanzania).

Life

H ...

, who formed the Society for German Colonization

The Society for German Colonization (german: Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation, GfdK) was founded on 28 March 1884 in Berlin by Carl Peters. Its goal was to accumulate capital for the acquisition of German colonial territories in overseas co ...

, concluded a series of treaties by which tribal chiefs ceded territory to the society. Prince Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

's government in 1885 granted imperial protection to the German East Africa Company

The German East Africa Company (german: Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Gesellschaft, abbreviated DOAG) was a chartered colonial organization which brought about the establishment of German East Africa, a territory which eventually comprised the area ...

established by Peters with Bismark's encouragement.

At the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergenc ...

of 1885, the fact that Kigoma had been established and supplied from Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

and Bagamoyo

Bagamoyo, is a historic coastal town founded at the end of the 18th century, though it is an extension of a much older (8th century) Swahili settlement, Kaole. It was chosen as the capital of German East Africa by the German colonial administra ...

led to the inclusion of German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mo ...

into the territory of the Conventional Basin of the Congo, to Belgium's advantage. At the table in Berlin, contrary to widespread perception, Africa was not partitioned; rather, rules were established among the colonial powers and prospective colonial powers as how to proceed in the establishment of colonies and protectorates. While the Belgian interest soon concentrated on the Congo River

The Congo River ( kg, Nzâdi Kôngo, french: Fleuve Congo, pt, Rio Congo), formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the second largest river in the world by discharg ...

, the British and Germans focused on Eastern Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

and in 1886 partitioned continental East Africa between themselves; the Sultanate of Zanzibar, now reduced to the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba, remained independent, for the moment. The Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leop ...

was eventually to give up its claim on Kigoma (its oldest station in Central Africa) and on any territory to the east of Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika () is an African Great Lake. It is the second-oldest freshwater lake in the world, the second-largest by volume, and the second-deepest, in all cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. It is the world's longest freshwater lake. T ...

, to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

.

German East Africa

All resistance to theGermans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

in the interior ceased and they could now set out to organize German East Africa. They continued brutally to exercise their authority with disregard and contempt for existing local structures and traditions. While the German colonial administration brought cash crops, railroads, and roads to Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

, European rule provoked African resistance. Between 1891 and 1894, the Hehe—led by Chief Mkwawa—resisted German expansion, but were eventually defeated. After a period of guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ta ...

, Mkwawa was cornered and committed suicide in 1898.

Maji Maji resistance

Widespread discontent re-emerged, and in 1902 a movement against forced labour for a cotton scheme rejected by the local population started along theRufiji River

The Rufiji River lies entirely within Tanzania. It is also the largest and longest river in the country. The river is formed by the confluence of the Kilombero and Luwegu rivers. It is approximately long, with its source in southwestern Tanzani ...

. The tension reached a breaking point in July 1905 when the Matumbi of Nandete led by Kinjikitile Ngwale revolted against the local administrators ( akida) and suddenly the revolt grew wider from Dar Es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (; from ar, دَار السَّلَام, Dâr es-Selâm, lit=Abode of Peace) or commonly known as Dar, is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over s ...

to the Uluguru Mountains, the Kilombero Valley, the Mahenge

Mahenge is a town in the Mahenge Mountains of Tanzania. It is the headquarters of Ulanga District in Morogoro Region.

There is a hospital, a market, and primary schools. A Catholic Capuchin mission was established around 1897, and there is ...

and Makonde plateaux, the Ruvuma

Ruvuma River, formerly also known as the Rovuma River, is a river in the African Great Lakes region. During the greater part of its course, it forms the border between Tanzania and Mozambique (in Mozambique known as ''Rio Rovuma''). The river is ...

in the southernmost part and Kilwa, Songea

Songea is the capital of Ruvuma Region in southwestern Tanzania. It is located along the A19 road. The city has a population of approximately 203,309, and it is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Songea. Between 1905 and 1907, the c ...

, Masasi

Masasi is one of the six districts of the Mtwara Region of Tanzania. It is bordered to the north by the Lindi Region, to the east by the Newala District, to the south by the Ruvuma River and Mozambique and to the west by Nanyumbu District

N ...

, and from Kilosa to Iringa

Iringa is a city in Tanzania with a population of 151,345 (). It is situated at a latitude of 7.77°S and longitude of 35.69°E. The name is derived from the Hehe word ''lilinga'', meaning fort. Iringa is the administrative capital of Iringa ...

down to the eastern shores of Lake Nyasa

Lake Malawi, also known as Lake Nyasa in Tanzania and Lago Niassa in Mozambique, is an African Great Lake and the southernmost lake in the East African Rift system, located between Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania.

It is the fifth largest fre ...

. The resistance culminated in the Maji Maji Resistance of 1905–1907. The resistance, which temporarily united a number of southern tribes ended only after an estimated 300,000 Africans had died from fighting or starvation. Research has shown that traditional hostilities played a large part in the resistance.

Germans had occupied the area since 1897 and totally altered many aspects of everyday life. They were actively supported by the missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

who tried to destroy all signs of indigenous beliefs, notably by razing the 'mahoka' huts where the local population worshiped their ancestors' spirits and by ridiculing their rites, dances and other ceremonies. This would not be forgotten or forgiven; the first battle which broke out at Uwereka in September 1905 under the Governorship of Count Gustav Adolf von Götzen

Gustav Adolf Graf von Götzen (12 May 1866 – 2 December 1910) was a German colonizer and Governor of German East Africa. He came to Rwanda in 1894 becoming the second European to enter the territory, since Oscar Baumann’s brief expedition in ...

turned instantly into an all-out war with indiscriminate murders and massacres perpetrated by all sides against farmers, settlers, missionaries, planters, villages, indigenous people and peasants. Known as the Maji-Maji war with the main brunt borne by the Ngoni people

The Ngoni people are an ethnic group living in the present-day Southern African countries of Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. The Ngoni trace their origins to the Nguni and Zulu people of kwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. ...

, this was a merciless rebellion and by far the bloodiest in Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

.

World War I

Before the outbreak of the war, German East Africa had been prepared to resist any attack that could be made without extensive preparation. For the first year of hostilities, the Germans were strong enough to conduct offensive operations in their neighbours' territories by, for example, repeatedly attacking railways inBritish East Africa

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was an area in the African Great Lakes occupying roughly the same terrain as present-day Kenya from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Controlled by Bri ...

. The strength of German forces at the beginning of the war is uncertain. Lieutenant-General Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

, the commander of British forces in east Africa beginning in 1916, estimated them at 2,000 Germans and 16,000 Askaris

An askari (from Somali, Swahili and Arabic , , meaning "soldier" or "military", which also means "police" in the Somali language) was a local soldier serving in the armies of the European colonial powers in Africa, particularly in the African G ...

. The white adult male population in 1913 numbered over 3,500 (exclusive of the German garrison). In addition, the indigenous population of over 7,000,000 formed a reservoir of manpower from which a force might be drawn, limited only by the supply of German officers and equipment. "There is no reason to doubt that the Germans made the best of this material during the ... nearly eighteen months which separated the outbreak of war from the invasion in force of their territory."

The geography of German East Africa also was a severe impediment to British and allied forces. The coastline offered few suitable points for landing and was backed by unhealthy swamps. The line of lakes and mountains to the west proved to be impenetrable. Belgian forces from the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

had to be moved through Uganda. On the south, the Ruvuma River

Ruvuma River, formerly also known as the Rovuma River, is a river in the African Great Lakes region. During the greater part of its course, it forms the border between Tanzania and Mozambique (in Mozambique known as ''Rio Rovuma''). The river is ...

was fordable only its upper reaches. In the north, only one practicable pass about five miles wide existed between the Pare Mountains

The Pare Mountains are a mountain range in northeastern Tanzania, located north of the Usambara Mountains. The mountains are administratively located in the Kilimanjaro Region, specifically in the Mwanga District and Same District. The North an ...

and Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It has three volcanic cones: Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world: above sea level and a ...

, and here the German forces had been digging in for eighteen months.

Germany commenced hostilities in 1914 by unsuccessfully attacking from the town of Tanga. The British then attacked the town in November 1914 but were thwarted by General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck (20 March 1870 – 9 March 1964), also called the Lion of Africa (german: Löwe von Afrika), was a general in the Imperial German Army and the commander of its forces in the German East Africa campaign. For four ye ...

's forces at the Battle of Tanga

The Battle of Tanga, sometimes also known as the Battle of the Bees, was the unsuccessful attack by the British Indian Expeditionary Force "B" under Major General A. E. Aitken to capture German East Africa (the mainland portion of present-day T ...

. The British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

occupied Mafia Island

Mafia Island (Kisiwa cha Mafia) is an island and district of Pwani Region, Tanzania. The island is the third largest in Tanzanian ocean territory, but is not administratively included within the semi-autonomous region of Zanzibar, which has been ...

in January 1915. However, the "attack on Tanga and the numerous smaller engagements that followed howedthe strength ... of erman forcesand made it evident that a powerful force must be organized before the conquest of erman East Africacould be ... undertaken. Such an enterprise had ... to await more favourable conditions on European battlefields and elsewhere. But in July, 1915, the last German troops in S.W. Africa capitulated ... and the nucleus of the requisite force ... became available." British forces from the northeast and southwest and Belgian forces from the northwest steadily attacked and defeated German forces beginning in January 1916. In October 1916, General Smuts wrote, "With the exception of the Mahenge Plateau he Germanshave lost every healthy or valuable part of their Colony".

Cut-off from Germany, General Von Lettow by necessity conducted a guerilla campaign throughout 1917, living off the land and dispersing over a wide area. In December, the remaining German forces evacuated the colony by crossing the Ruvuma River into Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique) or Portuguese East Africa (''África Oriental Portuguesa'') were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese colony. Portuguese Mozambique originally ...

. Those forces were estimated at 320 German troops and 2,500 Askaris. 1,618 Germans and 5,482 Askaris were killed or captured during the last six months of 1917. In November 1918, his remaining force surrendered near present-day Mbala, Zambia

Mbala is Zambia’s most northerly large town and seat of Mbala District in Northern Province, occupying a strategic location close to the border with Tanzania and controlling the southern approaches to Lake Tanganyika, 40 km by road to the ...

consisting of 155 Europeans, 1,165 Askaris, 2,294 African porters etc., and 819 African women.

Under the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, Germany relinquished all her overseas possessions, including German East Africa. Britain lost 3,443 men in battle plus 6,558 men to disease. The equivalent numbers for Belgium were 683 and 1,300. Germany lost 734 Europeans and 1,798 Africans.

Von Lettow's scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

policy and the requisition of buildings meant a complete collapse of the Government's education system, though some mission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

schools managed to retain a semblance of instruction. Unlike the Belgian, British, French and Portuguese colonial masters in central Africa, Germany had developed an educational program for her Africans that involved elementary, secondary and vocational schools. "Instructor qualifications, curricula, textbooks, teaching materials, all met standards unmatched anywhere in tropical Africa." In 1924, ten years after the beginning of the First World War and six years into British rule, the visiting American Phelps-Stokes Commission reported: In regards to schools, the Germans have accomplished marvels. Some time must elapse before education attains the standard it had reached under the Germans. But by 1920, the Education Department consisted of 1 officer and 2 clerks with a budget equal to 1% of the country's revenue—less than the amount appropriated for the maintenance of Government House.

British administration after World War I

In 1919, the population was estimated at 3,500,000. The first British civilian administrator after the end ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

was Sir Horace Archer Byatt CMG, appointed by Royal Commission on 31 January 1919. The colony was renamed Tanganyika Territory

Tanganyika was a colonial territory in East Africa which was administered by the United Kingdom in various guises from 1916 to 1961. It was initially administered under a military occupation regime. From 20 July 1922, it was formalised into a L ...

in January 1920. In September 1920 by the Tanganyika Order in Council, 1920, the initial boundaries of the territory, the Executive Council, and the offices of governor and commander-in-chief were established. The governor legislated by proclamation or ordinance until 1926.

Britain and Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

signed an agreement regarding the border between Tanganyika and Ruanda-Urundi

Ruanda-Urundi (), later Rwanda-Burundi, was a colonial territory, once part of German East Africa, which was occupied by troops from the Belgian Congo during the East African campaign in World War I and was administered by Belgium under milita ...

in 1924.

The administration of the Territory continued to be carried out under the terms of the mandate until its transfer to the Trusteeship System under the Charter of the United Nations by the Trusteeship Agreement of 13 December 1946.

British rule through indigenous authorities

Governor Byatt took measures to revive African institutions by encouraging limited local rule. He authorized the formation in 1922 of political clubs such as the Tanganyika Territory African Civil Service Association, which in 1929 became theTanganyika African Association

The Tanganyika African Association (TAA) was a Tanganyika Territory political association, formed in 1929. It was founded by civil servants including Ali Saidi, members of an earlier association called the Tanganyika Territory African Civil Ser ...

and later constituted the core of the nationalist movement. Under the Native Authority Ordinances of 1923, limited powers were granted to certain recognized chiefs who could also exercise powers granted by local customary law.

Sir Donald Cameron became the governor of Tanganyika in 1925. "His work ... was of great significance in the development of colonial administrative policy, being associated especially with the vigorous attempt to establish a system of 'Indirect Rule' through the traditional indigenous authorities." He was a major critic of Governor Byatt's policies about indirect rule, as evidenced by his ''Native Administration Memorandum No. 1, Principles of Native Administration and their Application''.

In 1926, the Legislative Council was established with seven unofficial (including two Indians) and thirteen official members, whose function was to advise and consent to ordinances issued by the governor. In 1945, the first Africans were appointed to the council. The council was reconstituted in 1948 under Governor Edward Twining

Edward Francis Twining, Baron Twining (29 June 1899 – 21 June 1967), known as Sir Edward Twining from 1949 to 1958, was a British diplomat, formerly Governor of North Borneo and Governor of Tanganyika. He was a member of the Twining tea ...

, with 15 unofficial members (7 Europeans, 4 Africans, and 4 Indians) and 14 official members. Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, af ...

became one of the unofficial members in 1954. The council was again reconstituted in 1955 with 44 unofficial members (10 Europeans, 10 Africans, 10 Indians, and 14 government representatives) and 17 official members.

Governor Cameron in 1929 enacted the Native Courts Ordinance No. 5, which removed those courts from the jurisdiction of the colonial courts and provided for a system of appeals with final resort to the governor himself.

Railway development

In 1928, theTabora

Tabora is the capital of Tanzania's Tabora Region and is classified as a municipality by the Tanzanian government. It is also the administrative seat of Tabora Urban District. According to the 2012 census, the district had a population of 226,999 ...

to Mwanza

Mwanza City, also known as Rock City to the residents, is a port city and capital of Mwanza Region on the southern shore of Lake Victoria in north-western Tanzania. With an urban population of 1,182,000 in 2021, it is Tanzania's second largest c ...

railway line was opened to traffic. The line from Moshi to Arusha

Arusha City is a Tanzanian city and the regional capital of the Arusha Region, with a population of 416,442 plus 323,198 in the surrounding Arusha District Council (2012 census).

Located below Mount Meru on the eastern edge of the eastern bran ...

opened in 1930.

1931 census

In 1931 a census established the population ofTanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

at 5,022,640 natives, in addition to 32,398 Asians and 8,228 Europeans.

Health and education initiatives

Under British rule, efforts were undertaken to fight theTsetse fly

Tsetse ( , or ) (sometimes spelled tzetze; also known as tik-tik flies), are large, biting flies that inhabit much of tropical Africa. Tsetse flies include all the species in the genus ''Glossina'', which are placed in their own family, Glos ...

(a carrier of sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis, also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals. It is caused by the species ''Trypanosoma brucei''. Humans are infected by two typ ...

), and to fight malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

and bilharziasis

Schistosomiasis, also known as snail fever, bilharzia, and Katayama fever, is a disease caused by parasitic flatworms called schistosomes. The urinary tract or the intestines may be infected. Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody ...

; more hospitals were built.

In 1926, the colonial administration provided subsidies to schools run by missionaries, and at the same time established its authority to exercise supervision and to establish guidelines. Yet in 1935, the education budget for the entire country of Tanganyika amounted to only US$290,000, although it is unclear how much this represented at the time in terms of purchasing power parity

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is the measurement of prices in different countries that uses the prices of specific goods to compare the absolute purchasing power of the countries' currencies. PPP is effectively the ratio of the price of a bask ...

.

Tanganyika wheat scheme

The British Government decided to develop wheat growing to help feed a war-ravaged and severely rationed Britain and eventually Europe at the hoped-for Allied victory at the end of the Second World War. An American farmer in Tanganyika,Freddie Smith

Freddie Matthew Smith (born March 19, 1988) is an American television actor. He is best known for his character Sonny Kiriakis, the first openly gay contract role on the daytime soap opera ''Days of Our Lives''. He also briefly portrayed Marco S ...

, was in charge, and David Gordon Hines

David Gordon Hines (8 February 1915 – 14 March 2000) was a chartered accountant who as a British colonial administrator developed farming co-operatives in Tanganyika and later in Uganda. This radically improved the living standards of farm ...

was the accountant responsible for the finances. The scheme had on the Ardai plains just outside Arusha

Arusha City is a Tanzanian city and the regional capital of the Arusha Region, with a population of 416,442 plus 323,198 in the surrounding Arusha District Council (2012 census).

Located below Mount Meru on the eastern edge of the eastern bran ...

; on Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It has three volcanic cones: Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world: above sea level and a ...

; and towards Ngorongoro to the west. All the machinery was lend/lease from the US, including 30 tractors, 30 ploughs, and 30 harrows. There were western agricultural and engineering managers. Most of the workers were Italian prisoners of war

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional ...

from Somalia and Ethiopia: excellent, skilled engineers and mechanics. The Ardai plains were too arid to be successful, but there were good crops in the Kilimanjaro and Ngorongoro areas.Work by WD Ogilvie: (a)1999 interview of David Hines; (b) London ''Daily Telegraph'' obituary of David Hines 8 April 2000

World War II

Two days afterNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

declared war and the British forces in Tanganyika were ordered to intern

An internship is a period of work experience offered by an organization for a limited period of time. Once confined to medical graduates, internship is used practice for a wide range of placements in businesses, non-profit organizations and gove ...

the German males living in Tanganyika. The British government feared that these Axis country citizens would attempt to help the Axis forces

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

and some of the Germans living in Dar es Salaam did attempt to flee the country but were stopped and later interned by Roald Dahl

Roald Dahl (13 September 1916 – 23 November 1990) was a British novelist, short-story writer, poet, screenwriter, and wartime fighter ace of Norwegian descent. His books have sold more than 250 million copies worldwide. Dahl has be ...

and a small group of Tanganyikan soldiers of the King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from Britain's various possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions within ...

.

During the war about 100,000 people from Tanganyika joined the Allied forces.Jay Heale, Winnie Wong, 2009, Cultures of the World, Second (Book 16), Tanzania, Publisher: Cavendish Square Publishing (March 1, 2009), and were part of the 375,000 British colonial troops who fought against the Axis forces. Tanganyikans fought in units of the King's African Rifles and fought in the East African Campaign in Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constitut ...

and Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

against the Italians, in Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

against the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

during the Madagascar Campaign

The Battle of Madagascar (5 May – 6 November 1942) was a British campaign to capture the Vichy French-controlled island Madagascar during World War II. The seizure of the island by the British was to deny Madagascar's ports to the Imperi ...

, and in Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

against the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

during the Burma Campaign. Tanganyika became an important source of food and Tanganyika's export income greatly increased from the pre-war years of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. However, despite the additional income, the war caused inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

within the country.

Transition to independence

In 1947, Tanganyika became aUnited Nations trust territory

United Nations trust territories were the successors of the remaining League of Nations mandates and came into being when the League of Nations ceased to exist in 1946. All of the trust territories were administered through the United Nati ...

under British control. "Its geography, topography, climate, geopolitics, patterns of settlement and history made Tanganyika the most significant of all UN Trust Territories."''Voices from Tanganyika: Great Britain, The United Nations and the Decolonization of a Trust Territory, 1946-1961'', authored by Ullrich Lohrmann, published by Lit Verlag, Berlin, 2007, accessed 30 October 2014 But two-thirds of the population lived in one-tenth of the territory because of water shortages, soil erosion, unreliable rainfall, tsetse fly infestations, and poor communications and transportation infrastructures.

Multi-ethnic population

In 1957, only 15 towns had more than 5,000 inhabitants, with the capitalDar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (; from ar, دَار السَّلَام, Dâr es-Selâm, lit=Abode of Peace) or commonly known as Dar, is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over s ...

having the nation's highest population of 128,742. Tanganyika was a multi-racial territory, which made it unique in the trusteeship world. Its total non-African population in 1957 was 123,310 divided as follows: 95,636 Asians and Arabs (subdivided as 65,461 Indians, 6,299 Pakistanis, 4,776 Goans, and 19,100 Arabs), 3,114 Somalis, and 3,782 "coloured" and "other" individuals. The white population, which included the Europeans (British, Italians, Greeks, and Germans) and white South Africans, totalled 20,598 individuals. Tanganyika's ethnic and economic make-up posed problems for the British. Their policy was geared to ensuring the continuance of the European presence as necessary to support the country's economy. But the British also had to remain responsive to the political demands of the Africans.

Many Africans were government servants, business employees, labourers, and producers of important cash crops during this period. But the vast majority were subsistence farmers who produced barely enough to survive. The standards of housing, clothing, and other social conditions were "equally quite poor." The Asians and Arabs were the middle class and tended to be wholesale and retail traders. The white population were missionaries, professional and government servants, and owners and managers of farms, plantations, mines, and other businesses. "White farms were of primary importance as producers of exportable agricultural crops."

Co-operative farming started

Britain, through its colonial officerDavid Gordon Hines

David Gordon Hines (8 February 1915 – 14 March 2000) was a chartered accountant who as a British colonial administrator developed farming co-operatives in Tanganyika and later in Uganda. This radically improved the living standards of farm ...

, encouraged the development of farming co-operatives to help convert subsistence farmers to cash husbandry. The subsistence farmers sold their produce to Indian traders at poor prices. By the early 1950s, there were over 400 co-operatives nationally. Co-operatives formed "unions" for their areas and developed cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

neries, coffee factories, and tobacco dryers. A major success for Tanzania was the Moshi coffee auctions that attracted international buyers after the annual Nairobi auctions.

The disastrous Tanganyika groundnut scheme

The Tanganyika groundnut scheme, or East Africa groundnut scheme, was a failed attempt by the British government to cultivate tracts of its African trust territory Tanganyika (now part of Tanzania) with peanuts. Launched in the aftermath of Worl ...

began in 1946 and was abandoned in 1951.

UN trust territory

After Tanganyika became a UN trust territory, the British felt extra pressure for political progress. The British principle of "gradualism" was increasingly threatened and was abandoned entirely during the last few years before independence. Five UN missions visited Tanganyika, the UN received several hundred written petitions, and a handful of oral presentations made it to the debating chambers in New York City between 1948 and 1960. The UN and the Africans who used the UN to achieve their purposes were very influential in driving Tanganyika towards independence. The Africans attended public gatherings in Tanganyika with UN representatives. There were peasants, urban workers, government employees, and local chiefs and nobles who personally approached the UN about local matters needing immediate action. And finally, there were Africans at the core of the political process who had the power to mould the future. Their goal was political advancement for Africans, with many supporting the nationalist movement, which had its roots in the African Association (AA). It was formed in 1929 as a social organization for African government servants in Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar. The AA was renamed theTanganyika African Association

The Tanganyika African Association (TAA) was a Tanganyika Territory political association, formed in 1929. It was founded by civil servants including Ali Saidi, members of an earlier association called the Tanganyika Territory African Civil Ser ...

(TAA) in 1948 and ceased being concerned with events in Zanzibar.

African nationalism

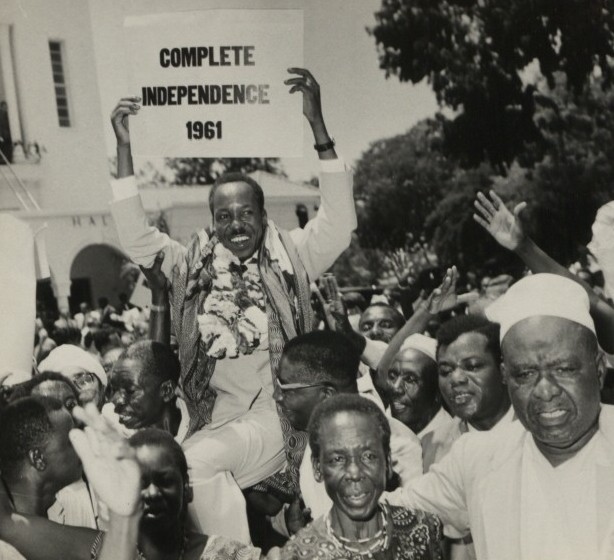

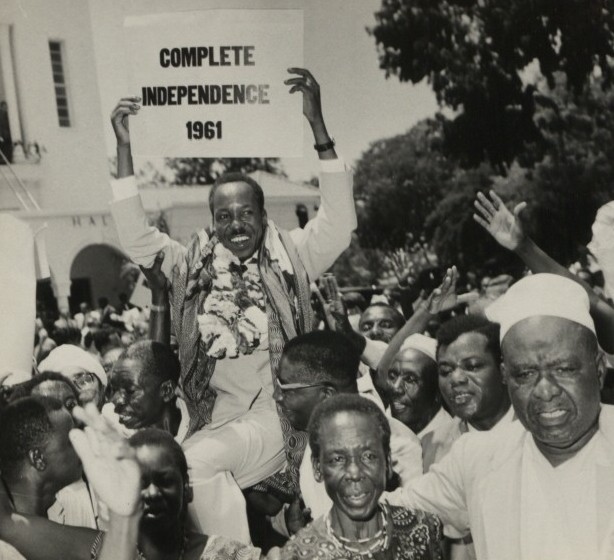

Beginning in 1954, African nationalism centered on theTanganyika African National Union

The Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) was the principal political party in the struggle for sovereignty in the East African state of Tanganyika (now Tanzania). The party was formed from the Tanganyika African Association by Julius Nyere ...

(TANU), which was a political organization formed by Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, af ...

in that year as the successor to the TAA. The TANU won the Legislative Council elections in 1958, 1959, and 1960, with Nyerere becoming chief minister after the 1960 election. Internal self-government started on 1 May 1961 followed by independence on 9 December 1961.

Zanzibar

Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

today refers to the island of that name, also known as Unguja, and the neighboring island of Pemba. Both islands fell under Portuguese domination in the 16th and early 17th centuries but were retaken by Omani Arabs in the early 18th century. The height of Arab rule came during the reign of Sultan Seyyid Said

Sayyid Saïd bin Sultan al-Busaidi ( ar, سعيد بن سلطان, , sw, Saïd bin Sultani) (5 June 1791 – 19 October 1856), was Sultan of Muscat and Oman, the fifth ruler of the Busaid dynasty from 1804 to 4 June 1856. His rule commenced fol ...

, who moved his capital from Muscat

Muscat ( ar, مَسْقَط, ) is the capital and most populated city in Oman. It is the seat of the Governorate of Muscat. According to the National Centre for Statistics and Information (NCSI), the total population of Muscat Governorate was ...

to Zanzibar, established a ruling Arab elite, and encouraged the development of clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands (or Moluccas) in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring or fragrance in consumer products, ...

plantations, using the island's slave labor. Zanzibar and Pemba were world-famous for their trade in spices and became known as the Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

; in the early 20th century, they produced approximately 90% of the world's supply of cloves. Zanzibar was also a major transit point in the African Great Lakes and Indian Ocean slave trade. Zanzibar attracted ships from as far away as the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, which established a consulate in 1833. The United Kingdom's early interest in Zanzibar was motivated by both commerce and the determination to end the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. In 1822, the British signed the first of a series of treaties with Sultan Said to curb this trade, but not until 1876 was the sale of slaves finally prohibited. The Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty of 1890 made Zanzibar and Pemba a British protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

, and the Caprivi Strip

The Caprivi Strip, also known simply as Caprivi, is a geographic salient protruding from the northeastern corner of Namibia. It is surrounded by Botswana to the south and Angola and Zambia to the north. Namibia, Botswana and Zambia meet at a s ...

in Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

became a German protectorate. British rule through a Sultan remained largely unchanged from the late 19th century until 1957, when elections were held for a largely advisory Legislative Council.

Independence and Union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar

In 1954,

In 1954, Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, af ...

, a school teacher who was then one of only two Tanganyikans educated to university level, organized a political party—the Tanganyika African National Union

The Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) was the principal political party in the struggle for sovereignty in the East African state of Tanganyika (now Tanzania). The party was formed from the Tanganyika African Association by Julius Nyere ...

(TANU). On 9 December 1961, Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

became independent, though retaining the British monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

as Queen of Tanganyika, and Nyerere became Prime Minister, under a new constitution. On 9 December 1962, a republican constitution was implemented with ''Mwalimu'' Julius Kambarage Nyerere as Tanganyika's first president.

Zanzibar received its independence from the United Kingdom on 10 December 1963, as a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

under its Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

. On 12 January 1964, the African majority revolted against the sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

and a new government was formed with the ASP leader, Abeid Karume

Abeid Amani Karume (4 August 1905 – 7 April 1972) was the first President of Zanzibar. He obtained this title as a result of a revolution which led to the deposing of Sir Jamshid bin Abdullah, the last reigning Sultan of Zanzibar, in . T ...

, as President of Zanzibar and Chairman

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the group ...

of the Revolutionary Council. In the first few days of what would come to be known as the Zanzibar Revolution, between 5,000 and 15,000 Arabs and Indians were murdered. During a series of riots, followers of the radical John Okello

John Gideon Okello (October 26, 1937 – ) was a Ugandan revolutionary and the leader of the Zanzibar Revolution in 1964. This revolution overthrew Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah and led to the proclamation of Zanzibar as a republic.

Biography Yo ...

carried out thousands of rapes and destroyed homes and other property. Within a few weeks, a fifth of the population had died or fled.

It was at this time that the Tanganyika army revolted and Britain was asked by Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, af ...

to send in troops. Royal Marines Commandos were sent by air from England via Nairobi and 40 Commando came ashore from the aircraft carrier HMS Bulwark. Several months were spent with Commandos touring the country disarming military outposts. When the successful operation ended, the Royal Marines left to be replaced by Canadian troops.