The first modern humans are believed to have inhabited

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

more than 100,000 years ago. South Africa's prehistory has been divided into two phases based on broad patterns of technology namely the

Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with ...

and

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

. After the discovery of hominins at

Taung and australopithecine fossils in limestone caves at

Sterkfontein

Sterkfontein (Afrikaans for ''Strong Spring'') is a set of limestone caves of special interest to paleo-anthropologists located in Gauteng province, about northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa in the Muldersdrift area close to the town of ...

,

Swartkrans, and

Kromdraai

Kromdraai Conservancy is a protected conservation park located to the south-west of Gauteng province in north-east South Africa. It is in the Muldersdrift area not far from Krugersdorp.

Etymology

Its name is derived from Afrikaans meaning "Cro ...

these areas were collectively designated a World Heritage site. The first nations of South Africa are collectively referred to as the

Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

, the Khoi Khoi and the San separately. These groups were displaced or sometimes absorbed by migrating Africans (Bantus) during the

Bantu expansion

The Bantu expansion is a hypothesis about the history of the major series of migrations of the original Proto-Bantu-speaking group, which spread from an original nucleus around Central Africa across much of sub-Saharan Africa. In the process, ...

from Western and Central Africa. While some maintained separateness, others were grouped into a category known as

Coloureds

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. Sou ...

, a multiracial ethnic group which includes people with shared ancestry from two or more of these groups:

Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

,

Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Nationa ...

,

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

,

Afrikaners

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Cas ...

,

Austronesians

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Au ...

,

East Asians and

South Asians. European exploration of the African coast began in the 13th century when Portugal committed itself to discover an alternative route to the

silk road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

that would lead to China. In the 14th and 15th century, Portuguese explorers traveled down the west African Coast, detailing and mapping the coastline and in 1488 they rounded the

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

. The

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

established a trading post in

Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

under the command of

Jan van Riebeeck

Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 – 18 January 1677) was a Dutch navigator and colonial administrator of the Dutch East India Company.

Life

Early life

Jan van Riebeeck was born in Culemborg, as the son of a surgeon. ...

in 1652, European workers who settled at the Cape became known as the

Free Burghers

Free Burghers ( Dutch: ''Vrijburgher'', Afrikaans: ''Vryburger'') were early European settlers at the Cape of Good Hope in the 18th century. The introduction of Free Burghers to the Cape is regarded as the beginning of a permanent settlement of ...

and gradually established farms in the

Dutch Cape Colony.

Following the

Invasion of the Cape Colony

The Invasion of the Cape Colony, also known as the Battle of Muizenberg, was a British military expedition launched in 1795 against the Dutch Cape Colony at the Cape of Good Hope. The Dutch colony at the Cape, established and controlled by the ...

in 1795 and 1806, mass migrations collectively known as the

Great Trek

The Great Trek ( af, Die Groot Trek; nl, De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyo ...

occurred during which the Voortrekkers established several

Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this are ...

settlements on the interior of South Africa. The discoveries of diamonds and gold in the nineteenth century had a profound effect on the fortunes of the region, propelling it onto the world stage and introducing a shift away from an exclusively agrarian-based economy towards industrialisation and the development of urban infrastructure. The discoveries also led to new conflicts culminating in open warfare between the

Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this are ...

settlers and the British Empire, fought essentially for control over the nascent South African mining industry.

Following the defeat of the Boers in the Anglo–Boer or

South African War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

(1899–1902), the

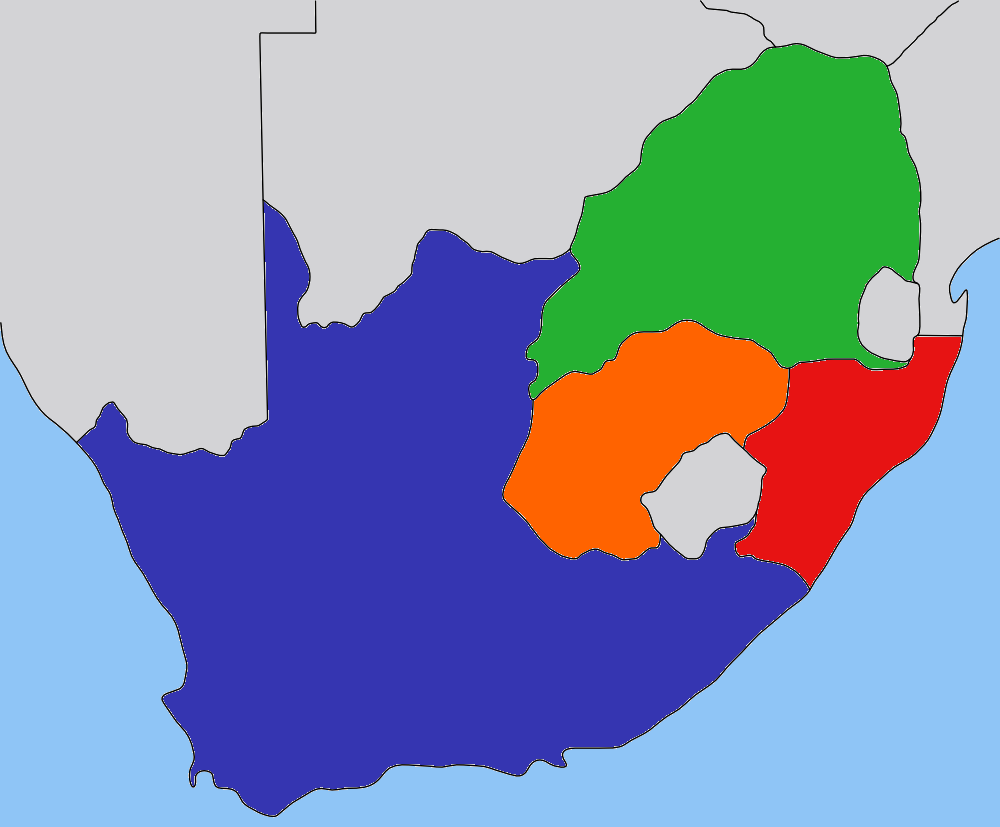

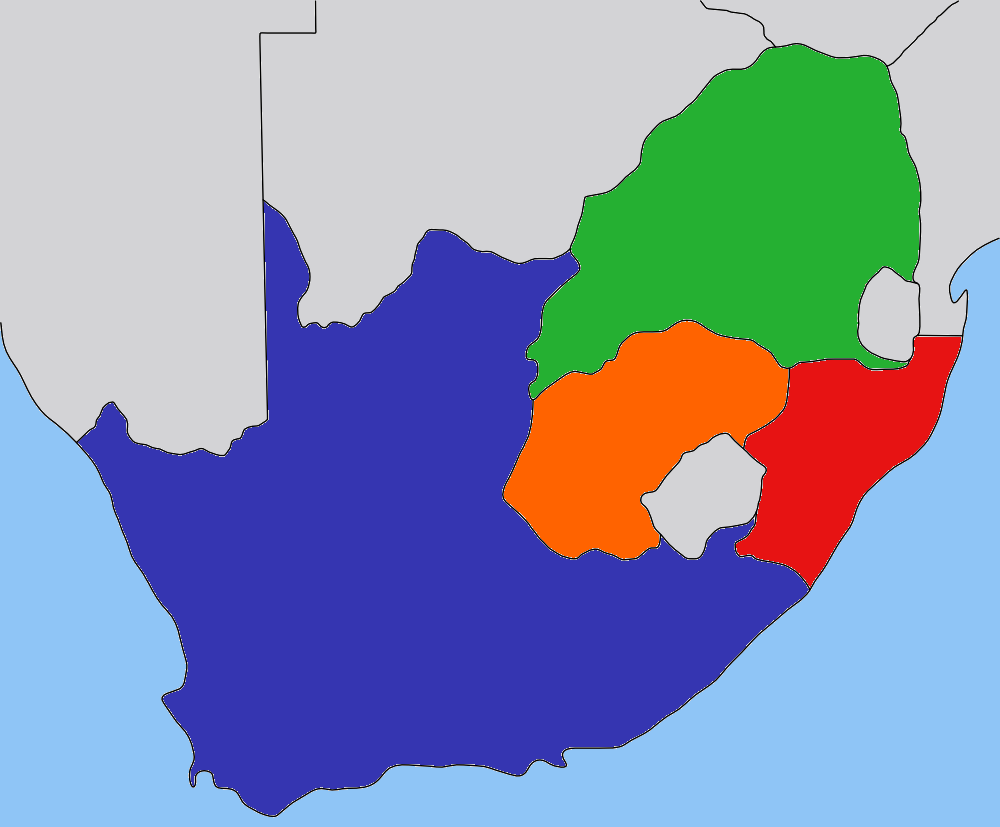

Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tr ...

was created as a

self-governing dominion of the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

on 31 May 1910 in terms of the

South Africa Act 1909

The South Africa Act 1909 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which created the Union of South Africa from the British Cape Colony, Colony of Natal, Orange River Colony, and Transvaal Colony. The Act also made provisions for ...

, which amalgamated the four previously separate British colonies:

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

,

Colony of Natal

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on 4 May 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Natalia Republic, Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three o ...

,

Transvaal Colony

The Transvaal Colony () was the name used to refer to the Transvaal region during the period of direct British rule and military occupation between the end of the Second Boer War in 1902 when the South African Republic was dissolved, and the ...

, and

Orange River Colony

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Union ...

. The country became a fully sovereign

nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may ...

within the British Empire, in 1934 following enactment of the

Status of the Union Act. The monarchy came to an end on 31 May 1961, replaced by a

republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

as the consequence of a

1960 referendum, which legitimised the country becoming the

Republic of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countr ...

.

From 1948–1994, South African politics was dominated by

Afrikaner nationalism

Afrikaner nationalism ( af, Afrikanernasionalisme) is a nationalistic political ideology which created by Afrikaners residing in Southern Africa during the Victorian era. The ideology was developed in response to the significant events in Afri ...

. Racial segregation and white minority rule known officially as

apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

, an

Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

word meaning "separateness", was implemented in 1948. On 27 April 1994, after decades of passive resistance, armed struggle,

terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

and international opposition to apartheid, the first black party

frican National Congress(ANC) achieved victory in the country's first democratic election. Since then, the African National Congress has governed South Africa, in an alliance with the

South African Communist Party

The South African Communist Party (SACP) is a communist party in South Africa. It was founded in 1921 as the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), tactically dissolved itself in 1950 in the face of being declared illegal by the governing N ...

and the

Congress of South African Trade Unions

The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) is a trade union federation in South Africa. It was founded in 1985 and is the largest of the country's three main trade union federations, with 21 affiliated trade unions.One Union expelled ...

.

Early history (before 1652)

Prehistory

Scientists researching the periods before written historical records were made have established that the territory of what is now referred to generically as South Africa was one of the important centers of

human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of '' Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual developmen ...

. It was inhabited by

Australopithecine

Australopithecina or Hominina is a subtribe in the tribe Hominini. The members of the subtribe are generally ''Australopithecus'' ( cladistically including the genera ''Homo'', '' Paranthropus'', and ''Kenyanthropus''), and it typically inclu ...

s since at least 2.5 million years ago.

Modern human settlement occurred around 125,000 years ago in the Middle Stone Age, as shown by archaeological discoveries at

Klasies River Caves. The first human habitation is associated with a DNA group originating in a northwestern area of southern Africa and still prevalent in the indigenous

Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

(

Khoi and

San). Southern Africa was later populated by

Bantu-speaking people who

migrated from the western region of central Africa during the early centuries AD.

At the

Blombos cave Professor

Raymond Dart

Raymond Arthur Dart (4 February 1893 – 22 November 1988) was an Australian anatomist and anthropologist, best known for his involvement in the 1924 discovery of the first fossil ever found of ''Australopithecus africanus'', an extinct hom ...

discovered the skull of a 2.51 million year old

Taung Child

The Taung Child (or Taung Baby) is the fossilised skull of a young '' Australopithecus africanus''. It was discovered in 1924 by quarrymen working for the Northern Lime Company in Taung, South Africa. Raymond Dart described it as a new specie ...

in 1924, the first example of ''

Australopithecus africanus

''Australopithecus africanus'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived between about 3.3 and 2.1 million years ago in the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from Taung, Sterkfontei ...

'' ever found. Following in Dart's footsteps

Robert Broom

Robert Broom FRS FRSE (30 November 1866 6 April 1951) was a British- South African doctor and palaeontologist. He qualified as a medical practitioner in 1895 and received his DSc in 1905 from the University of Glasgow.

From 1903 to 1910, he ...

discovered a new much more robust hominid in 1938 ''

Paranthropus robustus

''Paranthropus robustus'' is a species of robust australopithecine from the Early and possibly Middle Pleistocene of the Cradle of Humankind, South Africa, about 2.27 to 0.87 (or, more conservatively, 2 to 1) million years ago. It has been iden ...

'' at

Kromdraai

Kromdraai Conservancy is a protected conservation park located to the south-west of Gauteng province in north-east South Africa. It is in the Muldersdrift area not far from Krugersdorp.

Etymology

Its name is derived from Afrikaans meaning "Cro ...

, and in 1947 uncovered several more examples of ''Australopithecus africanus'' at

Sterkfontein

Sterkfontein (Afrikaans for ''Strong Spring'') is a set of limestone caves of special interest to paleo-anthropologists located in Gauteng province, about northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa in the Muldersdrift area close to the town of ...

. In further research at the Blombos cave in 2002, stones were discovered engraved with grid or cross-hatch patterns, dated to some 70,000 years ago. This has been interpreted as the earliest example ever discovered of abstract art or symbolic art created by ''

Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

''.

Many more species of early hominid have come to light in recent decades. The oldest is

Little Foot

"Little Foot" (Stw 573) is the nickname given to a nearly complete Australopithecus fossil skeleton found in 1994–1998 in the cave system of Sterkfontein, South Africa.

Originally nicknamed "little foot" in 1995 when four ankle bones in a mus ...

, a collection of footbones of an unknown hominid between 2.2 and 3.3 million years old, discovered at Sterkfontein by

Ronald J. Clarke. An important recent find was that of 1.9 million year old ''

Australopithecus sediba'', discovered in 2008. In 2015, the discovery near Johannesburg of a previously unknown species of ''Homo'' was announced, named ''

Homo naledi

'' Homo naledi'' is an extinct species of archaic human discovered in 2013 in the Rising Star Cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa dating to the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. The initial discovery comprises 1,550 specimens ...

''. It has been described as one of the most important paleontological discoveries in modern times.

San and Khoikhoi

The descendants of the Middle Paleolithic populations are thought to be the aboriginal

San and

Khoikhoi

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

tribes. These are collectively known as the ''

Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

'', a modern European portmanteau of these two tribes' names. The settlement of southern Africa by the Khoisan corresponds to the

earliest separation of the extant ''Homo sapiens'' populations altogether, associated in genetic science with what is described in scientific terms as matrilinear

haplogroup L0 (mtDNA) and patrilinear

haplogroup A (Y-DNA), originating in a northwestern area of southern Africa.

The San and Khoikhoi are essentially distinguished only by their respective occupations. Whereas the San were hunter-gatherers, the Khoikhoi were pastoral herders. The initial origin of the Khoikhoi remains uncertain.

Archaeological discoveries of livestock bones on the

Cape Peninsula

The Cape Peninsula ( af, Kaapse Skiereiland) is a generally mountainous peninsula that juts out into the Atlantic Ocean at the south-western extremity of the African continent. At the southern end of the peninsula are Cape Point and the Cape ...

indicate that the Khoikhoi began to settle there by about 2000 years ago.

In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Portuguese mariners, who were the first Europeans at the Cape, encountered pastoral Khoikhoi with livestock.

Later, English and Dutch seafarers in the late 16th and 17th centuries exchanged metals for cattle and sheep with the Khoikhoi.

The conventional view is that availability of livestock was one reason why, in the mid-17th century, the Dutch East India Company established a staging post where the port city of Cape Town is today situated.

The establishment of the staging post by the

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

at the Cape in 1652 soon brought the Khoikhoi into conflict with Dutch settlers over land ownership. Cattle rustling and livestock theft ensued, with the Khoikhoi being ultimately expelled from the peninsula by force, after a succession of wars. The first Khoikhoi–Dutch War broke out in 1659, the second in 1673, and the third 1674–1677.

By the time of their defeat and expulsion from the Cape Peninsula and surrounding districts, the Khoikhoi population was decimated by a

smallpox epidemic introduced by Dutch sailors against which the Khoikhoi had no natural resistance or indigenous medicines.

The Bantu people

The

Bantu expansion

The Bantu expansion is a hypothesis about the history of the major series of migrations of the original Proto-Bantu-speaking group, which spread from an original nucleus around Central Africa across much of sub-Saharan Africa. In the process, ...

was one of the major demographic movements in human prehistory, sweeping much of the African continent during the 2nd and 1st millennia BC. Bantu-speaking communities reached southern Africa from the

Congo basin as early as the 4th century BC. The advancing Bantu encroached on the Khoikhoi territory, forcing the original inhabitants of the region to move to more arid areas.

Some groups, ancestral to today's

Nguni peoples (the

Zulu,

Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

,

Swazi Swazi may refer to:

* Swazi people, a people of southeastern Africa

* Swazi language

* Eswatini

Eswatini ( ; ss, eSwatini ), officially the Kingdom of Eswatini and formerly named Swaziland ( ; officially renamed in 2018), is a landlocked coun ...

, and

Ndebele), preferred to live near the eastern coast of what is present-day South Africa.

Others, now known as the

Sotho–Tswana

The Sotho-Tswana people are a meta-ethnicity of southern Africa and live predominantly in Botswana, South Africa and Lesotho. The group mainly consists of four clusters; Southern Sotho (Sotho), Northern Sotho (which consists of the Baped ...

peoples (

Tswana

Tswana may refer to:

* Tswana people, the Bantu speaking people in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other Southern Africa regions

* Tswana language, the language spoken by the (Ba)Tswana people

* Bophuthatswana, the former ba ...

,

Pedi, and

Sotho), settled in the interior on the plateau known as the

Highveld

The Highveld (Afrikaans: ''Hoëveld'', where ''veld'' means "field") is the portion of the South African inland plateau which has an altitude above roughly 1500 m, but below 2100 m, thus excluding the Lesotho mountain regions to the south-east of ...

,

while today's

Venda

Venda () was a Bantustan in northern South Africa, which is fairly close to the South African border with Zimbabwe to the north, while to the south and east, it shared a long border with another black homeland, Gazankulu. It is now part of the ...

,

Lemba Lemba may refer to:

* ''Lemba'' (grasshopper), a genus of insect in the subfamily Caryandinae

* Lemba people, an African ethnic group in Southern Africa

;Places

* Lemba, Kinshasa, a commune in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo

* Lembá ...

, and

Tsonga people

The Tsonga people ( ts, Vatsonga) are a Bantu peoples, Bantu ethnic group primarily native to Southern Mozambique and South Africa (Limpopo and Mpumalanga). They speak Xitsonga, a Southern Bantu language.

A very small number of Tsonga people ar ...

s made their homes in the north-eastern areas of present-day South Africa.

The Kingdom of

Mapungubwe

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe (or Maphungubgwe) (c. 1075–c. 1220) was a medieval state in South Africa located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, south of Great Zimbabwe. The name is derived from either TjiKalanga and Tshivenda ...

, which was located near the northern border of present-day South Africa, at the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe rivers adjacent to present-day

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and ...

and

Botswana

Botswana (, ), officially the Republic of Botswana ( tn, Lefatshe la Botswana, label= Setswana, ), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory being the Kalaha ...

, was the first indigenous kingdom in southern Africa between AD 900 and 1300. It developed into the largest kingdom in the sub-continent before it was abandoned because of climatic changes in the 14th century. Smiths created objects of iron, copper and gold both for local decorative use and for foreign trade. The kingdom controlled trade through the east African ports to

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and

China, and throughout southern Africa, making it wealthy through the exchange of gold and ivory for imports such as Chinese porcelain and Persian glass beads.

Specifics of the contact between Bantu-speakers and the indigenous

Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

ethnic group remain largely unresearched, although

linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

proof of assimilation exists, as several southern

Bantu languages (notably

Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

and

Zulu) are theorised in that they incorporate many

click consonants from the

Khoisan languages

The Khoisan languages (; also Khoesan or Khoesaan) are a group of African languages originally classified together by Joseph Greenberg. Khoisan languages share click consonants and do not belong to other African language families. For much of ...

, as possibilities of such developing independently are valid as well.

Colonisation

Portuguese role

The Portuguese mariner

Bartolomeu Dias was the first European to explore the coastline of South Africa in 1488, while attempting to discover a trade route to the Far East via the southernmost cape of South Africa, which he named ''Cabo das Tormentas'', meaning

Cape of Storms. In November 1497, a fleet of Portuguese ships under the command of the Portuguese mariner

Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope. By 16 December, the fleet had passed the

Great Fish River on the east coast of South Africa, where Dias had earlier turned back. Da Gama gave the name

Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

to the coast he was passing, which in Portuguese means Christmas. Da Gama's fleet proceeded northwards to Zanzibar and later sailed eastwards, eventually reaching

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and opening the

Cape Route

The European-Asian sea route, commonly known as the sea route to India or the Cape Route, is a shipping route from the European coast of the Atlantic Ocean to Asia's coast of the Indian Ocean passing by the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Agulhas ...

between Europe and Asia. Many Portuguese words are still found along the coast of South Africa including Saldanha, Algoa, Natal, Agulhas, Benguela and Lucia.

Dutch role

Dutch colonization (1652–1815)

The

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

(in the Dutch of the day: ''Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie'', or VOC) decided to establish a permanent settlement at the Cape in 1652. The VOC, one of the major European trading houses sailing the

spice route to the East, had no intention of colonizing the area, instead wanting only to establish a secure base camp where passing ships could be serviced and restock on supplies.

To this end, a small VOC expedition under the command of

Jan van Riebeeck

Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 – 18 January 1677) was a Dutch navigator and colonial administrator of the Dutch East India Company.

Life

Early life

Jan van Riebeeck was born in Culemborg, as the son of a surgeon. ...

reached Table Bay on 6 April 1652.

The VOC had settled at the Cape in order to supply their trading ships. The Cape and the VOC had to import Dutch farmers to establish farms to supply the passing ships as well as to supply the growing VOC settlement. The small initial group of free burghers, as these farmers were known, steadily increased in number and began to expand their farms further north and east into the territory of the Khoikhoi.

The free burghers were ex-VOC soldiers and gardeners, who were unable to return to Holland when their contracts were completed with the VOC. The VOC also brought some 71,000 slaves to Cape Town from India, Indonesia, East Africa, Mauritius, and Madagascar.

The majority of burghers had

Dutch ancestry and belonged to the

Dutch Reformed Church

The Dutch Reformed Church (, abbreviated NHK) was the largest Christian denomination in the Netherlands from the onset of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century until 1930. It was the original denomination of the Dutch Royal Family and ...

, but there were also some Germans, who often happened to be

Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

. In 1688, the Dutch and the Germans were joined by French

Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

, Calvinist Protestants fleeing religious persecution in France under its Catholic ruler,

King Louis XIV.

Van Riebeeck considered it impolitic to enslave the local Khoi and San aboriginals, so the VOC began to import large numbers of slaves, primarily from the

Dutch colonies in Indonesia. Eventually, van Riebeeck and the VOC began to make

indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

out of the Khoikhoi and the San. The descendants of unions between the Dutch settlers and the Khoi-San and Malay slaves became known officially as the

Cape Coloureds

Cape Coloureds () are a South African ethnic group consisted primarily of persons of mixed race and Khoisan descent. Although Coloureds form a minority group within South Africa, they are the predominant population group in the Western Cape.

...

and the

Cape Malays, respectively. A significant number of the offspring from the white and slave unions were absorbed into the local proto-

Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

speaking white population. The racially mixed genealogical origins of many so-called

"white" South Africans have been traced to interracial unions at the Cape between the European occupying population and imported Asian and African slaves, the indigenous Khoi and San, and their vari-hued offspring.

Simon van der Stel

Simon van der Stel (14 October 1639 – 24 June 1712) was the last commander and first Governor of the Dutch Cape Colony, the settlement at the Cape of Good Hope.

Background

Simon was the son of Adriaan van der Steland Maria Lievens, ...

, the first Governor of the Dutch settlement, famous for his development of the lucrative South African wine industry, was himself of mixed race-origin.

British colonisation, Mfecane and Boer Republics (1815–1910)

British at the Cape

In 1787, shortly before the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, a faction within the politics of the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

known as the

Patriot Party attempted to overthrow the regime of

stadtholder William V William V may refer to:

* William V, Duke of Aquitaine (969–1030)

*William V of Montpellier (1075–1121)

* William V, Marquess of Montferrat (1191)

* William V, Count of Nevers (before 11751181)

*William V, Duke of Jülich (1299–1361)

* Willia ...

. Though the revolt was crushed, it was resurrected after the

French invasion of the Netherlands in 1794/1795 which resulted in the stadtholder fleeing the country. The Patriot revolutionaries then proclaimed the

Batavian Republic, which was closely allied to revolutionary France. In response, the stadtholder, who had taken up residence in England, issued the

Kew Letters

The Kew Letters (also known as the Circular Note of Kew) were a number of letters, written by stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange between 30 January and 8 February 1795 from the "Dutch House" at Kew Palace, where he temporarily stayed after hi ...

, ordering colonial governors to surrender to the British. The British then

seized the Cape in 1795 to prevent it from falling into French hands. The Cape was relinquished back to the Dutch in 1803. In 1805, the British inherited the Cape as a prize during the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

,

again seizing the Cape from the French controlled

Kingdom of Holland

The Kingdom of Holland ( nl, Holland (contemporary), (modern); french: Royaume de Hollande) was created by Napoleon Bonaparte, overthrowing the Batavian Republic in March 1806 in order to better control the Netherlands. Since becoming Empero ...

which had replaced the Batavian Republic.https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/batavian-republic-1803-1806

Like the Dutch before them, the British initially had little interest in the Cape Colony, other than as a strategically located port. As one of their first tasks they outlawed the use of the Dutch language in 1806 with the view of converting the European settlers to the British language and culture. The

Cape Articles of Capitulation of 1806 allowed the colony to retain "all their rights and privileges which they have enjoyed hitherto", and this launched South Africa on a divergent course from the rest of the British Empire, allowing the continuance of

Roman-Dutch law. British

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

of the area was recognised at the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815, the Dutch accepting a payment of 6 million pounds for the colony. This had the effect of forcing more of the Dutch colonists to move (or trek) away from British administrative reach. Much later, in 1820 the British authorities persuaded about 5,000 middle-class British immigrants (most of them "in trade") to leave Great Britain. Many of the

1820 Settlers

The 1820 Settlers were several groups of British colonists from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, settled by the government of the United Kingdom and the Cape Colony authorities in the Eastern Cape of South Africa in 1820.

Origins

After ...

eventually settled in

Grahamstown

Makhanda, also known as Grahamstown, is a town of about 140,000 people in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated about northeast of Port Elizabeth and southwest of East London. Makhanda is the largest town in the Makana ...

and

Port Elizabeth.

British policy with regard to South Africa would vacillate with successive governments, but the overarching imperative throughout the 19th century was to protect the strategic trade route to India while incurring as little expense as possible within the colony. This aim was complicated by border conflicts with the Boers, who soon developed a distaste for British authority.

European exploration of the interior

Colonel

Robert Jacob Gordon

Robert Jacob Gordon (29 September 1743, in Doesburg, Gelderland – 25 October 1795, in Cape Town) was a Dutch explorer, soldier, artist, naturalist and linguist of Scottish descent.

Life

Robert Jacob Gordon was the son of Maj. General Jacob ...

of the

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

was the first European to explore parts of the interior while commanding the Dutch garrison at the renamed

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

, from 1780 to 1795. The four expeditions Gordon undertook between 1777 and 1786 are recorded in a series of several hundred drawings known collectively as the Gordon Atlas, as well as in his journals, which were only discovered in 1964.

Early relations between the European settlers and the Xhosa, the first Bantu peoples they met when they ventured inward, were peaceful. However, there was competition for land, and this tension led to skirmishes in the form of cattle raids from 1779.

The British explorers

David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

and William Oswell, setting out from a mission station in the northern Cape Colony, are believed to have been the first white men to cross the Kalahari desert in 1849. The Royal Geographical Society later awarded Livingstone a gold medal for his discovery of

Lake Ngami in the desert.

Zulu militarism and expansionism

The Zulu people are part of the Nguni tribe and were originally a minor clan in what is today northern KwaZulu-Natal, founded ca. 1709 by

Zulu kaNtombela.

The 1820s saw a time of immense upheaval relating to the military expansion of the

Zulu Kingdom, which replaced the original African clan system with kingdoms.

Sotho-speakers know this period as the ''

difaqane

The Mfecane ( isiZulu, Zulu pronunciation: ̩fɛˈkǀaːne, also known by the Sesotho names Difaqane or Lifaqane (all meaning "crushing, scattering, forced dispersal, forced migration") is a historical period of heightened military conflict ...

'' ("

forced migration

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

");

Zulu-speakers call it the ''mfecane'' ("crushing").

Various theories have been advanced for the causes of the ''difaqane'', ranging from ecological factors to competition in the ivory trade. Another theory attributes the epicentre of Zulu violence to the slave trade out of Delgoa Bay in Mozambique situated to the north of Zululand. Most historians recognise that the Mfecane wasn't just a series of events caused by the founding of the Zulu kingdom but rather a multitude of factors caused before and after

Shaka Zulu

Shaka kaSenzangakhona ( – 22 September 1828), also known as Shaka Zulu () and Sigidi kaSenzangakhona, was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1816 to 1828. One of the most influential monarchs of the Zulu, he ordered wide-reaching reforms that ...

came into power.

In 1818,

Nguni Nguni may refer to:

*Nguni languages

* Nguni cattle

*Nguni people

*Nguni sheep, which divide into the Zulu, Pedi, and Swazi types

*Nguni stick-fighting

* Nguni shield

* Nguni homestead

*Nguni (surname) Nguni is an African surname. Notable people ...

tribes in Zululand created a militaristic kingdom between the

Tugela River

The Tugela River ( zu, Thukela; af, Tugelarivier) is the largest river in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. With a total length of , it is one of the most important rivers of the country.

The river originates in Mont-aux-Sources of the D ...

and

Pongola River

The Phongolo River is a river in South Africa. It is a tributary of the Maputo River. It rises near Utrecht in northern KwaZulu-Natal, flows east through Pongolo, is dammed at Pongolapoort, and crosses the Ubombo Mountains; then it flows north ...

, under the driving force of

Shaka

Shaka kaSenzangakhona ( – 22 September 1828), also known as Shaka Zulu () and Sigidi kaSenzangakhona, was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1816 to 1828. One of the most influential monarchs of the Zulu, he ordered wide-reaching reforms that ...

kaSenzangakhona, son of the chief of the Zulu clan. Shaka built large

armies

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, breaking from clan tradition by placing the armies under the control of his own officers rather than of hereditary chiefs. He then set out on a massive programme of expansion, killing or enslaving those who resisted in the territories he conquered. His ''

impis'' (warrior regiments) were rigorously disciplined: failure in battle meant death.

The Zulu resulted in the mass movement of many tribes who in turn tried to dominate those in new territories, leading to widespread warfare and waves of displacement spread throughout southern Africa and beyond. It accelerated the formation of several new nation-states, notably those of the Sotho (present-day

Lesotho) and the

Swazi Swazi may refer to:

* Swazi people, a people of southeastern Africa

* Swazi language

* Eswatini

Eswatini ( ; ss, eSwatini ), officially the Kingdom of Eswatini and formerly named Swaziland ( ; officially renamed in 2018), is a landlocked coun ...

(now

Eswatini (formerly Swaziland)). It caused the consolidation of groups such as the

Matebele, the

Mfengu

The ''amaMfengu'' (in the Xhosa language ''Mfengu'', plural ''amafengu'') was a reference of Xhosa clans whose ancestors were refugees that fled from the Mfecane in the early 19th century to seek land and protection from the Xhosa and have sinc ...

and the

Makololo

The Kololo or Makololo are a subgroup of the Sotho-Tswana people native to Southern Africa. In the early 19th century, they were displaced by the Zulu, migrating north to Barotseland, Zambia. They conquered the territory of the Luyana people and ...

.

In 1828 Shaka was killed by his half-brothers

Dingaan and

Umhlangana. The weaker and less-skilled Dingaan became king, relaxing military discipline while continuing the despotism. Dingaan also attempted to establish relations with the British traders on the Natal coast, but events had started to unfold that would see the demise of Zulu independence. Estimates for the death toll resulting from the Mfecane range from 1 million to 2 million.

Boer people and republics

After 1806, a number of

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

-speaking inhabitants of the Cape Colony trekked inland, first in small groups. Eventually, in the 1830s, large numbers of Boers migrated in what came to be known as the

Great Trek

The Great Trek ( af, Die Groot Trek; nl, De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyon ...

.

Among the initial reasons for their leaving the Cape colony were the English language rule. Religion was a very important aspect of the settlers culture and the bible and church services were in Dutch. Similarly, schools, justice and trade up to the arrival of the British, were all managed in the Dutch language. The language law caused friction, distrust and dissatisfaction.

Another reason for Dutch-speaking white farmers trekking away from the Cape was the abolition of slavery by the British government on Emancipation Day, 1 December 1838. The farmers complained they could not replace the labour of their slaves without losing an excessive amount of money. The farmers had invested large amounts of capital in slaves. Owners who had purchased slaves on credit or put them up as surety against loans faced financial ruin. Britain had allocated the sum of 1 200 000 British Pounds as compensation to the Dutch settlers, on condition the Dutch farmers had to lodge their claims in Britain as well as the fact that the value of the slaves was many times the allocated amount. This caused further dissatisfaction among the Dutch settlers. The settlers, incorrectly, believed that the Cape Colony administration had taken the money due to them as payment for freeing their slaves. Those settlers who were allocated money could only claim it in Britain in person or through an agent. The commission charged by agents was the same as the payment for one slave, thus those settlers only claiming for one slave would receive nothing.

South African Republic

The South African Republic (Dutch: ''Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek'' or ZAR, not to be confused with the much later

Republic of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countr ...

), is often referred to as The Transvaal and sometimes as the Republic of Transvaal. It was an independent and internationally recognised nation-state in southern Africa from 1852 to 1902. Independent sovereignty of the republic was formally recognised by

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

with the signing of the

Sand River Convention

The Sand River Convention ( af, Sandrivierkonvensie) of 17 January 1852 was a convention whereby the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formally recognised the independence of the Boers north of the Vaal River.

Background

The conven ...

on 17 January 1852.

The republic, under the premiership of

Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904) was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South African Republic, South Africa, and President of the So ...

, defeated British forces in the

First Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

and remained independent until the end of the Second Boer War on 31 May 1902, when it was forced to surrender to the British. The territory of the South African Republic became known after this war as the Transvaal Colony.

Free State Republic

The independent Boer republic of

Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

evolved from colonial Britain's

Orange River Sovereignty, enforced by the presence of British troops, which lasted from 1848 to 1854 in the territory between the Orange and Vaal rivers, named Transorange. Britain, due to the military burden imposed on it by the

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

in Europe, then withdrew its troops from the territory in 1854, when the territory along with other areas in the region was claimed by the Boers as an independent Boer republic, which they named the Orange Free State. In March 1858, after land disputes, cattle rustling and a series of raids and counter-raids, the Orange Free State declared war on the

Basotho

The Sotho () people, also known as the Basuto or Basotho (), are a Bantu nation native to southern Africa. They split into different ethnic groups over time, due to regional conflicts and colonialism, which resulted in the modern Basotho, who ...

kingdom, which it failed to defeat. A succession of wars were conducted between the Boers and the Basotho for the next 10 years. The name Orange Free State was again changed to the

Orange River Colony

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Union ...

, created by Britain after the latter occupied it in 1900 and then annexed it in 1902 during the

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

. The colony, with an estimated population of less than 400,000 in 1904 ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Union of South Africa as the

Orange Free State Province.

Natalia

Natalia was a short-lived Boer republic established in 1839 by Boer

Voortrekkers emigrating from the Cape Colony. In 1824 a party of 25 men under British Lieutenant F G Farewell arrived from the Cape Colony and established a settlement on the northern shore of the Bay of Natal, which would later become the port of Durban, so named after

Benjamin D'Urban

Lieutenant General Sir Benjamin D'Urban (16 February 1777 – 25 May 1849) was a British general and colonial administrator, who is best known for his frontier policy when he was the Governor in the Cape Colony (now in South Africa).

Ear ...

, a governor of the Cape Colony. Boer ''Voortrekkers'' in 1838 established the Republic of Natalia in the surrounding region, with its capital at

Pietermaritzburg. On the night of 23/24 May 1842 British colonial forces attacked the ''Voortrekker'' camp at Congella. The attack failed, with British forces then retreating back to Durban, which the Boers besieged. A local trader

Dick King and his servant Ndongeni, who later became folk heroes, were able to escape the blockade and ride to Grahamstown, a distance of 600 km (372.82 miles) in 14 days to raise British reinforcements. The reinforcements arrived in Durban 20 days later; the siege was broken and the ''Voortrekkers'' retreated. The Boers accepted British annexation in 1844. Many of the Natalia Boers who refused to acknowledge British rule trekked over the

Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Afrikaans: Drakensberge, Zulu: uKhahlambha, Sotho: Maluti) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, which encloses the central Southern African plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – within t ...

mountains to settle in the Orange Free State and Transvaal republics.

Cape Colony

Between 1847 and 1854,

Harry Smith, governor and high commissioner of the Cape Colony, annexed territories far to the north of original British and Dutch settlement.

Smith's expansion of the Cape Colony resulted in conflict with disaffected Boers in the Orange River Sovereignty who in 1848 mounted an abortive rebellion at Boomplaats, where the Boers were defeated by a detachment of the Cape Mounted Rifles. Annexation also precipitated a war between British colonial forces and the indigenous Xhosa nation in 1850, in the eastern coastal region.

Starting from the mid-1800s, the

Cape of Good Hope, which was then the largest state in southern Africa, began moving towards greater independence from Britain.

In 1854, it was granted its first locally elected legislature, the

Cape Parliament.

In 1872, after a long political struggle, it attained

responsible government with a locally accountable executive and Prime Minister. The Cape nonetheless remained nominally part of the British Empire, even though it was self-governing in practice.

The Cape Colony was unusual in southern Africa in that its laws prohibited any discrimination on the basis of race and, unlike the Boer republics, elections were held according to the non-racial

Cape Qualified Franchise system, whereby suffrage qualifications applied universally, regardless of race.

Initially, a period of strong economic growth and social development ensued. However, an ill-informed British attempt to force the states of southern Africa into a British federation led to inter-ethnic tensions and the

First Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

. Meanwhile, the discovery of diamonds around

Kimberley and gold in the

Transvaal led to a later return to instability, particularly because they fueled the rise to power of the ambitious colonialist

Cecil Rhodes. As Cape Prime Minister, Rhodes curtailed the multi-racial franchise, and his expansionist policies set the stage for the

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

.

Natal

Indian slaves from the

Dutch colonies in India had been introduced into the Cape area of South Africa by the Dutch settlers in 1654.

By the end of 1847, following annexation by Britain of the former Boer republic of Natalia, nearly all the Boers had left their former republic, which the British renamed Natal. The role of the Boer settlers was replaced by subsidised British immigrants of whom 5,000 arrived between 1849 and 1851.

By 1860, with slavery having been abolished in 1834, and after the annexation of Natal as a British colony in 1843, the British colonists in

Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

(now

kwaZulu-Natal) turned to

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

to resolve a labour shortage, as men of the local Zulu warrior nation were refusing to work on the plantations and farms established by the colonists. In that year, the

SS ''Truro'' arrived in Durban harbour with over 300 Indians on board.

Over the next 50 years, 150,000 more

indentured

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

Indian servants and labourers arrived, as well as numerous free "passenger Indians," building the base for what would become the largest Indian diasporic community outside India.

By 1893, when the lawyer and social activist

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

arrived in Durban, Indians outnumbered whites in Natal. The

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

struggle of Gandhi's

Natal Indian Congress

The Natal Indian Congress (NIC) was an organisation that aimed to fight discrimination against Indians in South Africa.

The Natal Indian Congress was proposed by Mahatma Gandhi on 22 May 1894. established on 22 August 1894.

Gandhi was the H ...

failed; until the

1994 advent of democracy, Indians in South Africa were subject to most of the discriminatory laws that applied to all non-white inhabitants of the country.

Griqua people

By the late 1700s, the Cape Colony population had grown to include a large number of mixed-race so-called "

coloureds

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. South ...

" who were the offspring of extensive interracial relations between male Dutch settlers, Khoikhoi females, and female slaves imported from Dutch colonies in the East. Members of this mixed-race community formed the core of what was to become the Griqua people.

Under the leadership of a former slave named Adam Kok, these "coloureds" or ''Basters'' (meaning mixed race or multiracial) as they were named by the Dutch—a word derived from ''baster'', meaning "bastard"—started trekking northward into the interior, through what is today named Northern Cape Province. The trek of the Griquas to escape the influence of the Cape Colony has been described as "one of the great epics of the 19th century." They were joined on their long journey by a number of San and Khoikhoi aboriginals, local African tribesmen, and also some white renegades. Around 1800, they started crossing the northern frontier formed by the Orange River, arriving ultimately in an uninhabited area, which they named Griqualand.

In 1825, a faction of the Griqua people was induced by Dr

John Philip, superintendent of the

London Missionary Society

The London Missionary Society was an interdenominational evangelical missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Edward Williams. It was largely Reformed in outlook, with Congregational m ...

in Southern Africa, to relocate to a place called

Philippolis

Philippolis is a town in the Free State province of South Africa. The town is the birthplace of many South African celebrities including the writer and intellectual Sir Laurens van der Post, actress Brümilda van Rensburg and Springboks rugby ...

, a mission station for the San, several hundred miles southeast of Griqualand. Philip's intention was for the Griquas to protect the missionary station there against

banditti in the region, and as a bulwark against the northward movement of white settlers from the Cape Colony. Friction between the Griquas and the settlers over land rights resulted in British troops being sent to the region in 1845. It marked the beginning of nine years of British intervention in the affairs of the region, which the British named Transorange.

In 1861, to avoid the imminent prospect of either being colonised by the Cape Colony or coming into conflict with the expanding Boer Republic of

Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

, most of the Philippolis Griquas embarked on a further trek. They moved about 500 miles eastward, over the Quathlamba (today known as the

Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Afrikaans: Drakensberge, Zulu: uKhahlambha, Sotho: Maluti) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, which encloses the central Southern African plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – within t ...

mountain range), settling ultimately in an area officially designated as "Nomansland", which the Griquas renamed Griqualand East. East Griqualand was subsequently annexed by Britain in 1874 and incorporated into the Cape Colony in 1879.

The original Griqualand, north of the Orange River, was annexed by Britain's Cape Colony and renamed Griqualand West after the discovery in 1871 of the world's richest deposit of diamonds at Kimberley, so named after the British Colonial Secretary, Earl Kimberley.

Although no formally surveyed boundaries existed, Griqua leader

Nicolaas Waterboer

Nic(h)olaas Waterboer (1819 - 17 September 1896) was a leader ("Kaptijn") of the Griqua people.

He was the last fully independent Griqua Kaptijn of Griqualand West, and after it became a British colony, his rule and that of his successors was la ...

claimed the diamond fields were situated on land belonging to the Griquas. The Boer republics of

Transvaal and the

Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

also vied for ownership of the land, but Britain, being the preeminent force in the region, won control over the disputed territory. In 1878, Waterboer led an unsuccessful rebellion against the colonial authorities, for which he was arrested and briefly exiled.

Wars against the Xhosa

In early South Africa, European notions of national boundaries and land ownership had no counterparts in African political culture. To Moshoeshoe the BaSotho chieftain from Lesotho, it was customary tribute in the form of horses and cattle represented acceptance of land use under his authority. To European settlers in Southern Africa, the same form of tribute was believed to constitute purchase and permanent ownership of the land under independent authority.

As European settlers started establishing permanent farms after trekking across the country in search of prime agricultural land, they encountered resistance from the local Bantu people who had originally migrated southwards from central Africa hundreds of years earlier. The consequent frontier wars became known as the

Xhosa Wars (which were also referred to in contemporary discussion as the

Kafir

Kafir ( ar, كافر '; plural ', ' or '; feminine '; feminine plural ' or ') is an Arabic and Islamic term which, in the Islamic tradition, refers to a person who disbelieves in God as per Islam, or denies his authority, or reject ...

Wars or the Cape Frontier Wars). In the southeastern part of South Africa, Boer settlers and the Xhosa clashed along the Great Fish River, and in 1779 the First Xhosa War broke out. For nearly 100 years subsequently, the Xhosa fought the settlers sporadically, first the Boers or Afrikaners and later the British. In the Fourth Xhosa War, which lasted from 1811 to 1812, the British colonial authorities forced the Xhosa back across the Great Fish River and established forts along this boundary.

The increasing economic involvement of the British in southern Africa from the 1820s, and especially following the discovery of first diamonds at Kimberley and gold in the Transvaal, resulted in pressure for land and African labour, and led to increasingly tense relations with Southern African states.

In 1818 differences between two Xhosa leaders, Ndlambe and Ngqika, ended in Ngqika's defeat, but the British continued to recognise Ngqika as the paramount chief. He appealed to the British for help against Ndlambe, who retaliated in 1819 during the Fifth Frontier War by attacking the British colonial town of Grahamstown.

Wars against the Zulu

In the eastern part of what is today South Africa, in the region named Natalia by the Boer trekkers, the latter negotiated an agreement with Zulu King

Dingane kaSenzangakhona allowing the Boers to settle in part of the then Zulu kingdom. Cattle rustling ensued and a party of Boers under the leadership of

Piet Retief were killed.

Subsequent to the killing of the Retief party, the Boers defended themselves against a Zulu attack, at the Ncome River on 16 December 1838. An estimated five thousand Zulu warriors were involved. The Boers took a defensive position with the high banks of the Ncome River forming a natural barrier to their rear with their ox waggons as barricades between themselves and the attacking Zulu army. About three thousand Zulu warriors died in the clash known historically as the

Battle of Blood River.

In the later annexation of the Zulu kingdom by imperial Britain, an

Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, cou ...

was fought in 1879. Following Lord Carnarvon's successful introduction of federation in Canada, it was thought that similar political effort, coupled with military campaigns, might succeed with the African kingdoms, tribal areas and Boer republics in South Africa.

In 1874, Henry Bartle Frere was sent to South Africa as High Commissioner for the British Empire to bring such plans into being. Among the obstacles were the presence of the independent states of the South African Republic and the Kingdom of Zululand and its army. Frere, on his own initiative, without the approval of the British government and with the intent of instigating a war with the Zulu, had presented an ultimatum on 11 December 1878, to the Zulu king Cetshwayo with which the Zulu king could not comply. Bartle Frere then sent

Lord Chelmsford to invade Zululand. The war is notable for several particularly bloody battles, including an overwhelming victory by the Zulu at the

Battle of Isandlwana, as well as for being a landmark in the timeline of imperialism in the region.

Britain's eventual defeat of the Zulus, marking the end of the Zulu nation's independence, was accomplished with the assistance of Zulu collaborators who harboured cultural and political resentments against centralised Zulu authority. The British then set about establishing large sugar plantations in the area today named

KwaZulu-Natal Province.

Wars with the Basotho

From the 1830s onwards, numbers of white settlers from the Cape Colony crossed the Orange River and started arriving in the fertile southern part of territory known as the Lower Caledon Valley, which was occupied by Basotho cattle herders under the authority of the Basotho founding monarch

Moshoeshoe I. In 1845, a treaty was signed between the British colonists and Moshoeshoe, which recognised white settlement in the area. No firm boundaries were drawn between the area of white settlement and Moshoeshoe's kingdom, which led to border clashes. Moshoeshoe was under the impression he was loaning grazing land to the settlers in accordance with African precepts of occupation rather than ownership, while the settlers believed they had been granted permanent land rights. Afrikaner settlers in particular were loath to live under Moshoesoe's authority and among Africans.

The British, who at that time controlled the area between the Orange and Vaal Rivers called the

Orange River Sovereignty, decided a discernible boundary was necessary and proclaimed a line named the Warden Line, dividing the area between British and Basotho territories. This led to conflict between the Basotho and the British, who were defeated by Moshoeshoe's warriors at the battle of Viervoet in 1851.

As punishment to the Basotho, the governor and commander-in-chief of the Cape Colony, George Cathcart, deployed troops to the Mohokare River; Moshoeshoe was ordered to pay a fine. When he did not pay the fine in full, a battle broke out on the Berea Plateau in 1852, where the British suffered heavy losses. In 1854, the British handed over the territory to the Boers through the signing of the

Sand River Convention

The Sand River Convention ( af, Sandrivierkonvensie) of 17 January 1852 was a convention whereby the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formally recognised the independence of the Boers north of the Vaal River.

Background

The conven ...

. This territory and others in the region then became the Republic of the Orange Free State.

A succession of wars followed from 1858 to 1868 between the Basotho kingdom and the Boer republic of

Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

. In the battles that followed, the Orange Free State tried unsuccessfully to capture Moshoeshoe's mountain stronghold at

Thaba Bosiu

Thaba Bosiu is a sandstone plateau with an area of approximately and a height of 1,804 meters above sea level. It is located between the Orange and Caledon Rivers in the Maseru District of Lesotho, 24 km east of the country's capital Maseru. ...

, while the

Sotho conducted raids in Free State territories. Both sides adopted scorched-earth tactics, with large swathes of pasturage and cropland being destroyed. Faced with starvation, Moshoeshoe signed a peace treaty on 15 October 1858, though crucial boundary issues remained unresolved.

[Beck 2000, p. 74] War broke out again in 1865. After an unsuccessful appeal for aid from the British Empire, Moshoeshoe signed the 1866 treaty of Thaba Bosiu, with the Basotho ceding substantial territory to the Orange Free State. On 12 March 1868, the British parliament declared the Basotho Kingdom a British protectorate and part of the British Empire. Open hostilities ceased between the Orange Free State and the Basotho. The country was subsequently named

Basutoland and is presently named

Lesotho.

Wars with the Ndebele

In 1836, when Boer V''oortrekkers'' (pioneers) arrived in the northwestern part of present-day South Africa, they came into conflict with a Ndebele sub-group that the settlers named "Matabele", under chief Mzilikazi. A series of battles ensued, in which Mzilikazi was eventually defeated. He withdrew from the area and led his people northwards to what would later become the Matabele region of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

Other members of the Ndebele ethnic language group in different areas of the region similarly came into conflict with the Voortrekkers, notably in the area that would later become the Northern Transvaal. In September 1854, 28 Boers accused of cattle rustling were killed in three separate incidents by an alliance of the Ndebele chiefdoms of Mokopane and Mankopane. Mokopane and his followers, anticipating retaliation by the settlers, retreated into the mountain caves known as Gwasa, (or Makapansgat in Afrikaans). In late October, Boer commandos supported by local Kgatla tribal collaborators laid siege to the caves. By the end of the siege, about three weeks later, Mokopane and between 1,000 and 3,000 people had died in the caves. The survivors were captured and allegedly enslaved.

Wars with the Bapedi

The Bapedi wars, also known as the

Sekhukhune wars, consisted of three separate campaigns fought between 1876 and 1879 against the

Bapedi

The Pedi or (also known as the Northern Sotho or and the Marota or ) – are a southern African ethnic group that speak Pedi or ''Sepedi'', a dialect belonging to the Sotho-Tswana enthnolinguistic group. Northern Sotho is a term used to ...

under their reigning monarch

King Sekhukhune I, in the northeastern region known as

Sekhukhuneland, bordering on