History of Seattle before 1900 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Two conflicting perspectives exist for the early history of Seattle. There is the "establishment" view, which favors the centrality of the

Denny Party

The Denny Party is a group of American pioneers credited with founding Seattle, Washington. They settled at Alki Point on November 13, 1851.

History

A wagon party headed by Arthur A. Denny left Cherry Grove, Illinois on April 10, 1851. The part ...

(generally the Denny, Mercer, Terry, and Boren families), and Henry Yesler

Henry Leiter Yesler (December 2, 1810 – December 16, 1892) was an entrepreneur and a politician, regarded as a founder of the city of Seattle. Yesler served two non-consecutive terms as Mayor of Seattle, and was the city's wealthiest resident ...

. A second, less didactic view, advanced particularly by historian Bill Speidel

William C Speidel (1912–1988) was a columnist for ''The Seattle Times'' and a self-made historian who wrote the books ''Sons of the Profits'' and ''Doc Maynard, The Man Who Invented Seattle'' about the people who settled and built Seattle, Wa ...

and others such as Murray Morgan, sees David Swinson "Doc" Maynard as a key figure, perhaps ''the'' key figure. In the late nineteenth century, when Seattle had become a thriving town, several members of the Denny Party still survived; they and many of their descendants were in local positions of power and influence. Maynard was about ten years older and died relatively young, so he was not around to make his own case. The Denny Party were generally conservative Methodists, teetotalers

Teetotalism is the practice or promotion of total personal abstinence from the psychoactive drug alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler or teetotaller, or is ...

, Whigs and Republicans, while Maynard was a drinker and a Democrat. He felt that well-run prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

could be a healthy part of a city's economy. He was also on friendly terms with the region's Native Americans, while many of the Denny Party were not. Thus Maynard was not on the best of terms with what became the Seattle Establishment, especially after the Puget Sound War

The Puget Sound War was an armed conflict that took place in the Puget Sound area of the state of Washington in 1855–56, between the United States military, local militias and members of the Native American tribes of the Nisqually, Muckl ...

. He was nearly written out of the city's history until Morgan's 1951 book ''Skid Road'' and Speidel's research in the 1960s and 1970s.

Founding

What is now Seattle has been inhabited since at least the end of the lastglacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

(c. 8000 BCE—10,000 years ago). Archaeological excavations at what is now called West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

in Discovery Park, Magnolia

''Magnolia'' is a large genus of about 210 to 340The number of species in the genus ''Magnolia'' depends on the taxonomic view that one takes up. Recent molecular and morphological research shows that former genera ''Talauma'', ''Dugandiodendr ...

confirm settlement within the current city for at least 4,000 years and probably much longer. The area of ("herring

Herring are forage fish, mostly belonging to the family of Clupeidae.

Herring often move in large schools around fishing banks and near the coast, found particularly in shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and North Atlantic Ocean ...

house") and later ("where there are horse clams") at the then-mouth of the Duwamish River

The ''Dkhw'Duw'Absh'' and ''Xachua'bsh'' are today represented by the

Seattle was incorporated as a town January 14, 1865. The incorporators were Charles C. Terry, Henry L. Yesler, David T. Denny,

Seattle was incorporated as a town January 14, 1865. The incorporators were Charles C. Terry, Henry L. Yesler, David T. Denny,

As has been remarked, Seattle in this era was an "open" and often relatively lawless town. Although it boasted two English-language

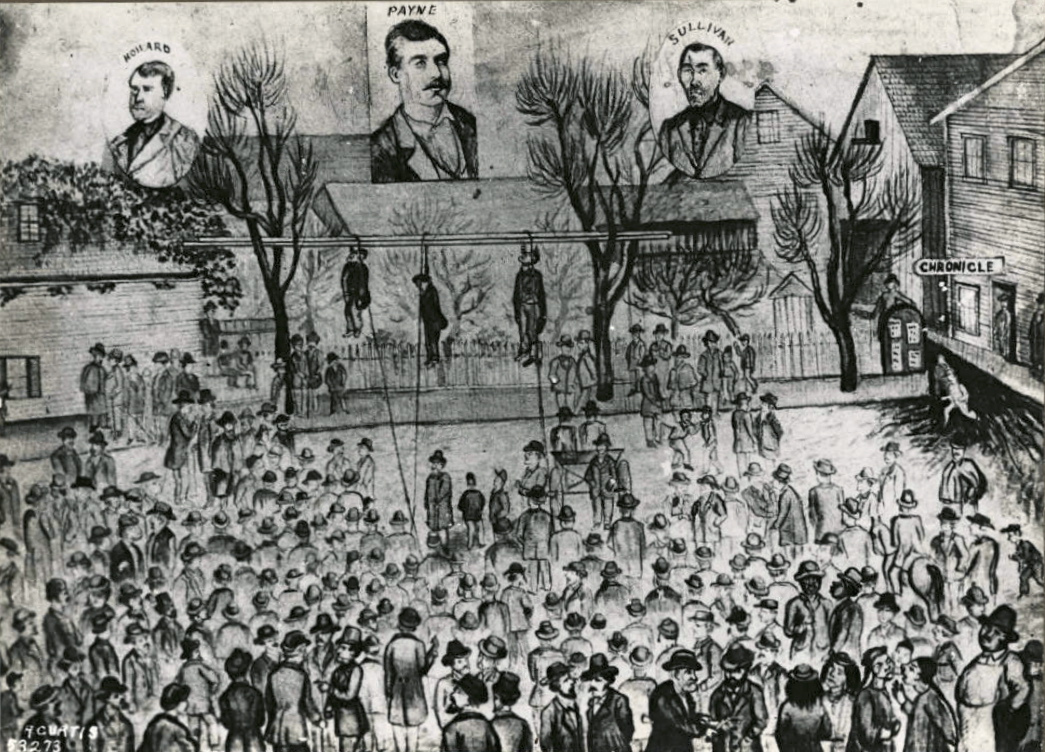

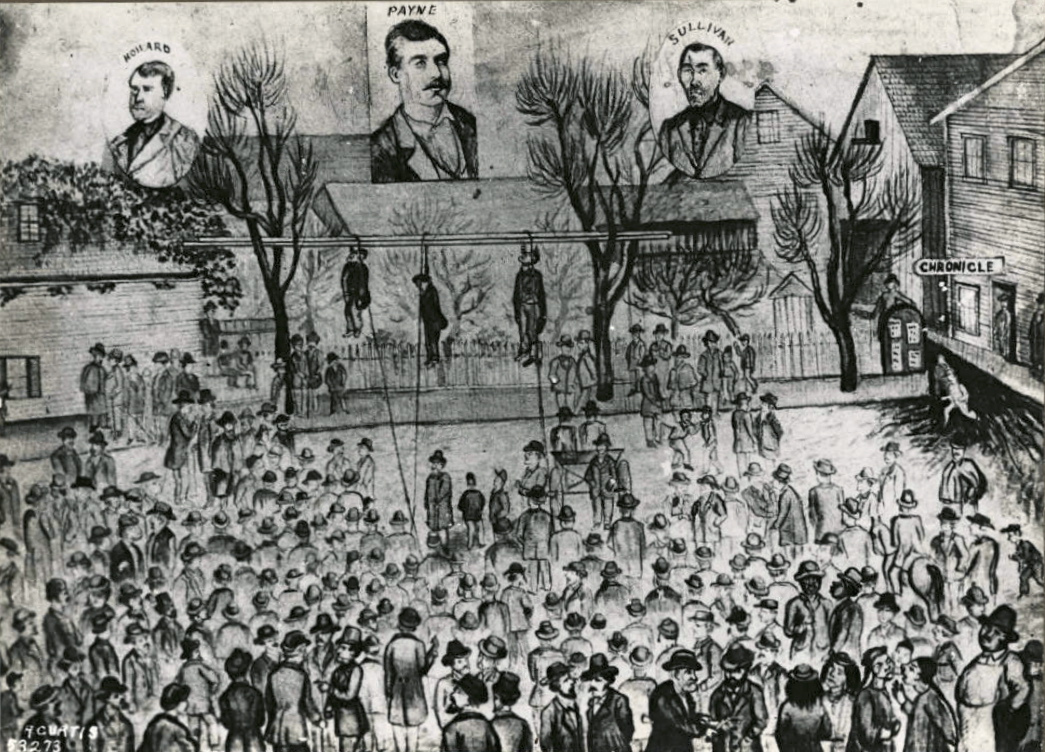

As has been remarked, Seattle in this era was an "open" and often relatively lawless town. Although it boasted two English-language  The 1882 lynchings are well described in Murray Morgan's book ''Skid Road''. The events involved a mob defying an armed sheriff, successfully disarming the sheriff's deputies, and assaulting Judge Roger Sherman Greene, who attempted to slash the ropes by which the lynching victims were to be hanged. Judge Greene, while not doubting the actual guilt of the lynched men, was later to write that "the lynchers were co-criminal with the lynched".

In an era during which the Washington Territory was one of the first parts of the U.S. to (briefly) allow

The 1882 lynchings are well described in Murray Morgan's book ''Skid Road''. The events involved a mob defying an armed sheriff, successfully disarming the sheriff's deputies, and assaulting Judge Roger Sherman Greene, who attempted to slash the ropes by which the lynching victims were to be hanged. Judge Greene, while not doubting the actual guilt of the lynched men, was later to write that "the lynchers were co-criminal with the lynched".

In an era during which the Washington Territory was one of the first parts of the U.S. to (briefly) allow

Among the few defenders of the rule of law were the Methodist Episcopal Ministers' Association and Judge Thomas Burke. Burke, an

Among the few defenders of the rule of law were the Methodist Episcopal Ministers' Association and Judge Thomas Burke. Burke, an

Seattle, as well as the rest of the nation, was hard hit by the

Seattle, as well as the rest of the nation, was hard hit by the

and * * *

Page links t

Village Descriptions Duwamish-Seattle section

Dailey referenced "Puget Sound Geography" by T. T. Waterman. Washington DC: National Anthropological Archives, mss. .d.

''Duwamish et al. vs. United States of America, F-275''. Washington DC: US Court of Claims, 1927. ef. 5

"Indian Lake Washington" by David Buerge in the ''Seattle Weekly'', 1–7 August 1984

"Seattle Before Seattle" by David Buerge in the ''Seattle Weekly'', 17–23 December 1980.

''The Puyallup-Nisqually'' by Marian W. Smith. New York: Columbia University Press, 1940.

Recommended start i

"Coast Salish Villages of Puget Sound"

* *

2d edition of vol. I of III * *

Lange referenced a very extensive list.

Summary article **

Lange referenced Lange, "Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 among Northwest Coast and Puget Sound Indians

HistoryLink.org ''Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History''. Accessed 8 December 2000. * * * * * *

Speidel provides a substantial bibliography with extensive primary sources. *

Speidel provides a substantial bibliography with extensive primary sources. * . * *

Wilma referenced "Petition: To the Honorable Arthur A. Denny, Delegate to Congress from Washington Territory," n.d., National Archives Roll 909, "Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-81";

Pioneer Association of the State of Washington, "A Petition to Support Recognition of The Duwamish Indians as a 'Tribe', June 18, 1988, in possession of Ken Tollefson, Seattle, Washington. * {{cite web , last =Wilma , first =David , date =2000-01-01 , url=http://www.historylink.org/essays/output.cfm?file_id=2076 , title =Stolen totem pole unveiled in Seattle's Pioneer Square on October 18, 1899 , work =HistoryLink.org Essay 2076 , publisher =Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Seattle Unit , access-date =2006-07-16

Wilam referenced Paul Dorpat, ''Seattle Now and Then Vol. 2'' (Seattle: Tartu Publications, 1984), 32-35;

Joseph H. Wherry, ''The Totem Pole Indians'', (New York: Wilfred Funk, Inc., 1964), 64, 89;

William C. Speidel, ''Sons of the Profits'' (Seattle: Nettle Creek Publishing Co., 1967), 329-331;

Viola Garfield, ''Seattle's Totem Poles'' (Bellevue, WA: Thistle Press, 1996), 9;

Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation, ''Data on the History of Seattle Park System Vol. 4'' (Seattle: Seattle Parks Department, 1978);

James William Clise, "Personal Memoirs 1855-1935" Mimeograph, Altadena, California, 1935, Seattle Public Library.

provides a collection of articles on Seattle and Washington State history, unparalleled in its niche. * Seattl

Museum of History and Industry

With the Seattle Room at the

Washington State History Museum

Washington State Historical Society

University of Washington Libraries: Digital Collections

*

88 photographs, c. 1888–1893, of early Seattle, including the waterfront and street scenes, Madrona and Leschi parks, Native American hop pickers, scenes of the aftermath of the

Frank La Roche Photographs

312 photographs c. 1888-1910 depicting scenes of the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush, A small photograph album (ca. 1891) used as a sales tool. Photographed by Frank La Roche, it contains an historical photographic record of early Seattle and its expansion northwards along the shores of

Theodore E. Peiser Photographs

140 images from the later part of the 19th century to about 1907. Among his subjects were images of troops preparing to embark from

Prosch Seattle Views Album

169 images by Thomas Prosch, one of Seattle's earliest pioneers, documenting the early history of Seattle and vicinity, c. 1851–1906.

Ongoing database of over 1,700 historical photographs of Seattle with special emphasis on images depicting neighborhoods, recreational activities including baseball, the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, "The Great Snow of 1916", theaters and transportation. *

Images by the pioneer photographer A.C. Warner, from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, of Seattle conventional street scenes, waterfront activity, city parks, and

Duwamish Tribe

The Duwamish ( lut, Dxʷdəwʔabš, ) are a Lushootseed-speaking Native American tribe in western Washington, and the indigenous people of metropolitan Seattle, where they have been living since the end of the last glacial period (c. 8000 BCE ...

.

George Vancouver

Captain George Vancouver (22 June 1757 – 10 May 1798) was a British Royal Navy officer best known for his 1791–1795 expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern Pacific Coast regions, including the coasts of what are ...

was the first Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an to visit the Seattle area in May 1792 during his 1791–95 expedition to chart the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Thou ...

; the first White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

forays for sites in the area were in the 1830s.

The founding of Seattle is usually dated from the arrival of the Denny Party

The Denny Party is a group of American pioneers credited with founding Seattle, Washington. They settled at Alki Point on November 13, 1851.

History

A wagon party headed by Arthur A. Denny left Cherry Grove, Illinois on April 10, 1851. The part ...

on November 13, 1851, at Alki Point. The group had travelled overland from the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

to Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous ...

, then made a short ocean journey up the Pacific coast into Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected m ...

, with the express intent of founding a town. The next April, Arthur A. Denny abandoned the original site at Alki in favor of a better-protected site on Elliott Bay

Elliott Bay is a part of the Central Basin region of Puget Sound. It is in the U.S. state of Washington, extending southeastward between West Point in the north and Alki Point in the south. Seattle was founded on this body of water in the 1850s ...

, near the south end of what is now downtown Seattle

Downtown is the central business district of Seattle, Washington. It is fairly compact compared with other city centers on the U.S. West Coast due to its geographical situation, being hemmed in on the north and east by hills, on the west by ...

. Around the same time, Doc Maynard began settling the land immediately south of Denny's. Charles C. Terry and others hung on at Alki for a few more years, but eventually it became clear that Maynard and Denny had chosen the better location.

The first plat

In the United States, a plat ( or ) (plan) is a cadastral map, drawn to scale, showing the divisions of a piece of land. United States General Land Office surveyors drafted township plats of Public Lands Surveys to show the distance and bea ...

s for Seattle were filed on May 23, 1853. Nominal legal land settlement was provisionally established in 1855 (with treaty terms for what is now Seattle not implemented). Doc Maynard's land claim lay south of today's Yesler Way, encompassing most of today's Pioneer Square Historical District and the International District. He based his street grid on strict compass bearings. The more northerly plats of Arthur A. Denny and Carson D. Boren encompassed Pioneer Square north of what is now Yesler Way; the heart of the current downtown; and the western slope of First Hill. These had street grids that more or less followed the shoreline. The downtown grid from Yesler Way north to Stewart Street is oriented 32 degrees west of north; from Stewart north to Denny Way the orientation is 49 degrees west of north. The result is a tangle of streets where the grids clash. (''See also Street layout of Seattle

The street layout of Seattle is based on a series of disjointed rectangular street grids. Most of Seattle and King County use a single street grid, oriented on true north. Near the center of the city, various land claims were platted in the 19th ...

.'')

Both Alki and the settlement that was to become Seattle relied in their early decades on the timber industry, shipping out logs (and, later, milled timber) to build and rebuild San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

which, as Bill Speidel points out, kept burning down. Seattle and Alki offered plenty of trees to build San Francisco and plenty of hill

A hill is a landform that extends above the surrounding terrain. It often has a distinct summit.

Terminology

The distinction between a hill and a mountain is unclear and largely subjective, but a hill is universally considered to be not a ...

s to slide them down to water. A climax forest of trees up to 1,000–2,000 years old and towering as high as nearly covered much of what is now Seattle. Today, none of that size remain anywhere in the world.

Relations with the natives

''This section draws heavily on Bill Speidel,'' Sons of the Profits ''(1967) and'' Doc Maynard'' (1978).'' Doc Maynard ''and Murray Morgan,'' Skid Road ''(1951, 1960, 1982) are especially useful on the events regarding resistance nominally led by Kamiakim in the January 1856 attack on the town.''Generally before the Point Elliott Treaty

The early Seattle settlers had a sometimes rocky relationship with the local Native Americans. There is no question that the settlers were steadily taking away native lands and, in many cases, treating the natives terribly. There were numerous deadly attacks by settlers against natives and by natives against settlers. Bill Speidel writes in ''Sons of the Profits'', "The general consensus of the community was that killing an Indian was a matter of no graver consequence than shooting a cougar or a bear..." Against this background, Doc Maynard stands out for his excellent relations with the natives. He andChief Seattle

Chief Seattle ( – June 7, 1866) was a Suquamish and Duwamish chief. A leading figure among his people, he pursued a path of accommodation to white settlers, forming a personal relationship with "Doc" Maynard. The city of Seattle, in th ...

were friends and allies: Maynard certainly profited greatly from this friendship, but that should not diminish the fact that during the outbreak of violent hostilities in 1856 he risked the wrath of his fellow settlers by protecting neutral Indians. However, outside of some old-time trappers and traders, he was almost unique in his attitude.

Denny and Edward Lander (the latter was the first local federal judge) also stood out in that they believed that the law should be applied fairly and equally: to them, murder was murder, regardless of the race of the victim. However, it was impossible to get this view upheld by a jury. In ''Sons of the Profits'' Speidel recounts a case of two vigilantes who had hanged a native man. After a series of (possibly deliberate) irregularities in their trial, the jury acquitted these obviously guilty men on a technicality.

Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represen ...

probably did more damage to relations between settlers and natives than any one other person. He put a bounty on scalps of "bad Indians". He declared martial law to prevent Lander from issuing writs of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, ...

'' for people who were held in jail for little other reason than sympathizing with the natives. On at least two occasions, he actually had Lander himself jailed.

Perhaps worst of all in its consequences for relations, he dealt dishonestly in treaties, among other things making oral promises that were not matched by what was written down. The local natives had at least a thirty-year history of dealing with the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

, who had developed a reputation for driving a hard bargain, but sticking honestly to what they agreed to, and for treating Whites and Indians impartially. This continued through the dealings of the local Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

Superintendent General, Joel Palmer

General Joel Palmer (October 4, 1810 – June 9, 1881) was an American pioneer of the Oregon Territory in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. He was born in Canada, and spent his early years in New York and Pennsylvania before serving ...

, who (along with Maynard's brother-in-law, Indian Agent Mike Simmons) was among the few even-handed men in the BIA.

Consequently, when Stevens, in drafting treaties, acted in a manner that Judge James Wickerson would characterize forty years later as "unfair, unjust, ungenerous, and illegal", some natives, quite unprepared for such behavior by the official representatives of the white man's power, were angered to the point of war. The unjust and deliberately confusing Western Washington treaties such as that of Medicine Creek (December 26, 1854) and Point Elliott (now Mukilteo

Mukilteo ( ) is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is located on the Puget Sound between Edmonds, Washington, Edmonds and Everett, Washington, Everett, approximately north of Seattle. The city had a population of 20,254 ...

) (January 22, 1855) were followed by the yet more provocative Treaty of Walla Walla (May 21, 1855), as Stevens pointedly ignored federal government instructions to stick to sorting out the areas where natives and settlers found themselves immediately adjacent to one another, or, from the other perspective, where settlers moved right in on Native places.

Generally after the Point Elliott Treaty

By the time of theTreaty of Point Elliott

The Treaty of Point Elliott of 1855, or the Point Elliott Treaty,—also known as Treaty of Point Elliot (with one ''t'') / Point Elliott Treaty—is the lands settlement treaty between the United States government and the Native American tribes ...

, Maynard had already made an ally of Chief Seattle by arranging to have him somewhat compensated for the use of his name for the new town. Chief Seattle's ancestral religion and Coast Salish

The Coast Salish is a group of ethnically and linguistically related Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, living in the Canadian province of British Columbia and the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon. They speak one of the Coa ...

culture have beliefs opposed to speaking or using a person's name after that person's death and prior to protocols, so this was not a simple matter, although Chief Seattle soon converted to a somewhat eclectic Roman Catholicism. (See also Duwamish). At Point Elliott, Maynard cemented this alliance (and greatly benefited his emerging town) by getting Chief Seattle and the Duwamish a separate, more favorable treaty, which, in exchange for a relatively large reservation (promised, not yet ever fulfilled), Natives abandoned all aboriginal title to , constituting an area almost identical to the eventual twentieth-century city limits of the City of Seattle, for nearly nothing at the time.

With Stevens in Eastern Washington sowing discord, Secretary of State Charles Mason was left in charge of the state government. Yakama

The Yakama are a Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in eastern Washington state.

Yakama people today are enrolled in the federally recognized tribe, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Their Ya ...

Chief Kamiakim had effectively declared war and told nations such as the Duwamish that they could either join him or would be treated as enemies. By autumn, there had been an exchange of massacres by Whites and settlers, in which both sides seemed ready to kill whichever people of the other race were at hand, with no regard for whether these particular individuals had in any way previously wronged them. (This cycle of retaliatory violence would reach its logical conclusion two years after the war, when ''si'ab'' Lescay (Chief Leschi

Chief Leschi (; 1808 – February 19, 1858) was a chief of the Nisqually Indian Tribe of southern Puget Sound, Washington, primarily in the area of the Nisqually River.

Following outbreaks of violence and the Yakima Wars (1855–1858), as a l ...

) was tried and condemned to death for a murder, and hanged before his appeal could be properly heard.)

Maynard got Mike Simmons to deputize him as a Special Indian Agent, then—in a complex, multi-way transaction—cemented a relationship with acting governor Mason and some other key figures by selling them some prime Seattle real estate at a good price. He then used the money from the transaction to buy supplies and a boat to ferry Chief Seattle and his Duwamish to what was effectively a privately funded reservation at Port Madison, west of Puget Sound. He also, at enormous personal risk, spent the first several weeks of November 1855 traveling around eastern King County, which was already penetrated by some of Kamiakim's men, informing several hundred other neutral natives that there was a safe place they could go. Most of them took him up on it. Induced fear effected abandonment of places Natives were otherwise loath to leave.

(In ''Doc Maynard'', Bill Speidel reports that not all of the Seattle businessmen were pleased with his getting the local Indians out of the way. Henry Yesler and others found themselves deprived of much of their labor force and wrote letters of protest to the territorial government.)

Shortly before Stevens returned to Olympia January 16, 1856, Captain E.D. Keyes had managed an uneasy informal truce by communicating with, among others, Chief Leschi. Stevens promptly undercut the truce, saying of the natives, "Nothing but death is mete punishment for their perfidy".

On January 25, 1856, Stevens announced, "The town of Seattle is in as much danger of an Indian attack as are the cities of San Francisco or New York".

On January 26, 1856, natives attacked the Seattle settlement. Friendly Indians permitted to stay in Seattle had warned the Whites, and sentries had been put on patrol. In the morning, acting on tip, a shell was lobbed into the forest above the town, what is now First Hill. First fire. The Indians fired back, small arms. Settlers rushed from their cabins to the blockhouse

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stro ...

. The defenses were based on a large wooden blockhouse

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stro ...

, a five-foot-high wood-and-earth breastworks, various ravines—and the cannon just offshore zeroed (bearing and range laid in). The settlement was defended at the time by the 150 man, 566 ton, 16 gun sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' en ...

''Decatur'', the bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, e ...

''Bronte'', seven out-of-town civilian volunteers, fifty local volunteers, and at least 6 Marines from the ''Decatur'' The number of attackers is impossible to establish: estimates range from a mere thirty to 2000 with more than a hundred killed, another hundred wounded. Not so much as a single Indian body was ever found, not even a sign of blood. The Indians had made no attempt to storm the stockade. No one in the blockhouse was much interested in venturing out on attack. Both sides had paused for dinner. There were two known fatalities: a young volunteer and a 14-year-old boy, both of whom had neglected to stay behind cover. No one who kept inside the stockade was wounded. A few things do seem clear in this fog of war: nearly all of the local volunteers hardly left the blockhouse, the Navy took no combat casualties in this land battle, and Kamiakim's forces were successfully driven off, but also took few (if any) fatalities. Still, they seem to have drawn the conclusion that attacking a major settlement wasn't worth the trouble. The only remaining major battle of the war was to occur March 10 at Connell's Prairie near Puyallup

Puyallup may refer to:

* Puyallup (tribe), a Native American tribe

* Puyallup, Washington, a city

** Puyallup High School

** Puyallup School District

** Puyallup station, a Sounder commuter rail station

** Washington State Fair, formerly the ...

.

After the skirmish "Battle of Seattle"

The cessation of general hostilities did not diminish Stevens' crusading zeal against the natives. He encouraged fratricidal war by offering the "good Indians" a bounty for scalps of the "bad Indians". The largest collector of such rewards was Chief Seattle's sworn rival, Chief Patkanim, a leader among the Snoqualmie and Snohomish. According to Speidel, Patkanim was not above killing and scalping his own slaves as a means of generating income. Speidel also narrates (in ''Sons of the Profits'') that on one occasion this led to a native being killed and scalped in Stevens' own office. Stevens continually attempted to recruit Chief Seattle and the Duwamish to this cause. Maynard and Chief Seattle, who had already gone to great lengths to help keep the Duwamish at a safe distance from Patkanim, never actually refused the Governor's request, but instead maintained a successful pattern of stalling and passive resistance to avoid ever providing any Duwamish fighters to further Stevens' scheme. The1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic

Year 186 ( CLXXXVI) was a common year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Aurelius and Glabrio (or, less frequently, year 939 ''Ab urbe co ...

killed roughly half of the native population. Documentation in archives and historical epidemiology demonstrates that Governmental policies furthered the progress of the epidemic among the natives.

The Seattle Establishment, including 'Doc' Maynard, petitioned the Territorial Delegate to Congress in 1866 to deny treaty rights to the Duwamish. The commitments made by the United States government in the Point Elliott Treaty have not yet been met.

Yesler's Mill

At first, Alki was larger than Seattle. "It was platted into six blocks of eight lots... and most of them had buildings on them that were in use. There weren't eight level, usable blocks in all of Seattle". However, when Henry Yesler brought "financial backing from aMassillon, Ohio

Massillon is a city in Stark County, Ohio, Stark County in the U.S. state of Ohio, approximately west of Canton, Ohio, Canton, south of Akron, and south of Cleveland. The population was 32,146 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. Mass ...

capitalist, John E. McLain, to start a steam sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logging, logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes ...

once he had isolated the perfect location for such a structure", he chose a Seattle location, on the waterfront where Maynard and Denny's plats met. Thereafter, Seattle would dominate the lumber industry.

Yesler selected this location because of a critical flaw with Alki as a port: "During the winter, the north wind, building up the tides in front of it, comes sweeping down the Sound out of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, piling mighty waves on Alki Point. Beginning with Terry... nobody has been able to build anything out in the water at Alki that will withstand those waves".

The road leading down the hill to that mill, later called Mill Street and now known as Yesler Way, was originally known as the Skid Road, the route for skidding logs down to the mill, hence the term "Skid Road" or corrupted as "Skid Row

A skid row or skid road is an impoverished area, typically urban, in English-speaking North America whose inhabitants are mostly poor people " on the skids". This specifically refers to poor or homeless, considered disreputable, downtrodden or fo ...

" for a rundown or dilapidated urban area as the mill declined and the area collapsed with the Crash

Crash or CRASH may refer to:

Common meanings

* Collision, an impact between two or more objects

* Crash (computing), a condition where a program ceases to respond

* Cardiac arrest, a medical condition in which the heart stops beating

* Couch ...

and Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

.

Via the bargaining power of his mill, Yesler wrangled about of prime land from some of the original settlers. Besides his mill, Yesler started a cookhouse that "did more to 'set' the heart of the city in the middle of Yesler's property holdings than anything else Henry did. Henry never did make a lot of money out of his mill. It was the strategic location of his land that made him a millionaire". Like many of Seattle's early entrepreneurs, Yesler was not always the most scrupulous about how he made his money; he borrowed $30,000 at 8% interest to build the mill, and repaid McLain only after McLain took Yesler to court three times.

A city grows

The first Seattle fortunes were founded on logs, and later milled timber, shipped south for the construction of buildings in San Francisco. Seattle itself, in the early years, was, of course, also a place of wooden buildings, and remained so until the Great Fire of June 6, 1889. Even the early system of delivering water to the settlement used hollowed-out logs for pipes. Seattle in its early years relied on the timber industry, shipping logs (and, later, milled timber) toSan Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

.

Terry sold out Alki (which, after his departure barely held on as a settlement), moved to Seattle and began acquiring land. He either owned or partially owned the first ships that allowed Seattle's timber industry to exist by providing a means to move the product to market. He eventually gave a land grant to the University of the Territory of Washington that housed its original campus and today makes the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seatt ...

a downtown landlord collecting rents of more than $1 million a year. He worked in politics to establish street grades, a water system, and a host of other services (which, not coincidentally, benefited him as one of the city's largest landholders).

Meanwhile, Arthur Denny became the second richest man in town, after Yesler, and got himself elected to territorial legislature. From that position, he tried unsuccessfully to get the territorial capital moved to Seattle from its then supposedly temporary location in Olympia. The other potential money prizes were the territorial penitentiary and the territorial university. When the politics all played out, Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. ...

wound up as the proposed capital, Port Townsend

Port Townsend is a city on the Quimper Peninsula in Jefferson County, Washington, United States. The population was 10,148 at the 2020 United States Census.

It is the county seat and only incorporated city of Jefferson County. In addition t ...

was supposed to get the penitentiary, and Seattle got the university. Apparently, Seattle was the only real winner in this deal: to this day, Olympia remains the capital of Washington; the main state penitentiary is in Walla Walla.

The legislature had tacked on the requirement that a grant of of land would be required for the university to be built, which they presumably thought would be sufficient to prevent its construction. However, Denny wanted his town to grow and donated the land, creating what would be "one of the biggest and most effective central core properties in the United States". The University of the Territory of Washington (later the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seatt ...

) opened on November 4, 1861. There were barely enough students to run it as a high school, let alone as a university, but over time it grew into its originally grandiose name.

The logging town developed rapidly into a small city. Despite being officially founded by the Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

s of the Denny Party, Seattle quickly developed a reputation as a wide-open town, a haven for prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

, liquor

Liquor (or a spirit) is an alcoholic drink produced by distillation of grains, fruits, vegetables, or sugar, that have already gone through alcoholic fermentation. Other terms for liquor include: spirit drink, distilled beverage or h ...

, and gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of value ("the stakes") on a random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy are discounted. Gambling thus requires three ele ...

. Some attribute this, at least in part, to Maynard, who arrived separately from the Denny Party, and who had a rather different view of what it would take to build a city, based on his experience in growing Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S ...

. By selling some of his land cheaply on condition that businesses be soon built upon them, he recruited professionals, such as blacksmiths and purveyors of vice, who enhanced the value of his remaining land. The city's first brothel dated from 1861 and was founded by one John Pinnell (or Pennell), who was already involved in similar business in San Francisco. Real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more genera ...

records show that nearly all of the city's first 60 businesses were on, or immediately adjacent to, Maynard's plat.

Seattle was incorporated as a town January 14, 1865. The incorporators were Charles C. Terry, Henry L. Yesler, David T. Denny,

Seattle was incorporated as a town January 14, 1865. The incorporators were Charles C. Terry, Henry L. Yesler, David T. Denny, Charles Plummer

Charles Plummer, FBA (1851–1927) was an English historian and cleric, best known as the editor of Sir John Fortescue's ''The Governance of England'', and for coining the term "bastard feudalism". He was the fifth son of Matthew Plummer of St ...

and Hiram Burnett

Hiram Burnett (July 5, 1817 at Southborough, Massachusetts – 1906, in Seattle, Washington) was a well-known pioneer of the Puget Sound country, and an honored citizen of Seattle.

Family and early life

His parents were Charles Ripley Burne ...

, manager of the largest Puget Sound lumber company predecessor to Pope & Talbot

Pope & Talbot, Inc. was a lumber company and shipping company founded by Andrew Jackson Pope and Frederic Talbot in 1849 in San Francisco, California. Pope and Talbot came to California in 1849 from East Machias, Maine. Pope & Talbot lumber comp ...

. That charter was voided January 18, 1867, in response to unrest. Seattle was re-incorporated as a city on December 2, 1869. At the times of incorporation, the population was approximately 350 and 1,000, respectively.

Railroad rivalry and encroaching civilization

On July 14, 1873, theNorthern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, wh ...

announced that they had chosen the then-small town of Tacoma over Seattle as the Western terminus of their transcontinental railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

. The railroad barons appear to have been gambling on the advantage they could gain from being able to buy up the land around their terminus cheaply instead of bringing the railroad into a more established Pacific port town.

Unwilling to be bypassed, the citizens of Seattle chartered their own railroad, the Seattle & Walla Walla, to link with the Union Pacific Railroad in eastern Washington. The S&WW never got beyond Renton, but that was far enough to connect with new coal mines, fueling industry in Seattle. The later Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway was only moderately more successful, although it did provide a route for logs to come to the city from as far away as Arlington, Washington

Arlington is a city in northern Snohomish County, Washington, United States, part of the Seattle metropolitan area. The city lies on the Stillaguamish River in the western foothills of the Cascade Range, adjacent to the city of Marysville. It i ...

, boost development of towns, and help Seattle hit the jackpot with the Northern Pacific. The Great Northern Railway chose Seattle as the terminus for its transcontinental road in 1893, winning Seattle a place in competition for freight traffic to California and across the Pacific. The Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern was, over the years, incorporated into the Northern Pacific and then the Burlington Northern

The Burlington Northern Railroad was a United States-based railroad company formed from a merger of four major U.S. railroads. Burlington Northern operated between 1970 and 1996.

Its historical lineage begins in the earliest days of railroadin ...

railways. The line was abandoned as a railroad in 1971 with the general decline in rail, and became in 1978 a foot and bicycle route renamed the Burke-Gilman Trail, then gradually greatly extended.

As has been remarked, Seattle in this era was an "open" and often relatively lawless town. Although it boasted two English-language

As has been remarked, Seattle in this era was an "open" and often relatively lawless town. Although it boasted two English-language newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as politics, business, spor ...

s (and, for a while, a third in Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

), and telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into e ...

s had arrived in town, lynch law sometimes prevailed (there were at least four lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

s in 1882), school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes co ...

s barely operated, and indoor plumbing

Plumbing is any system that conveys fluids for a wide range of applications. Plumbing uses pipes, valves, plumbing fixtures, tanks, and other apparatuses to convey fluids. Heating and cooling (HVAC), waste removal, and potable water delive ...

was a rare novelty. In the low mud flats where much of the city was built, sewage

Sewage (or domestic sewage, domestic wastewater, municipal wastewater) is a type of wastewater that is produced by a community of people. It is typically transported through a sewer system. Sewage consists of wastewater discharged from reside ...

was almost as likely to come in on the tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

as to flow away. Potholes in the street were so bad that legend has it there was at least one fatal drowning

Drowning is a type of suffocation induced by the submersion of the mouth and nose in a liquid. Most instances of fatal drowning occur alone or in situations where others present are either unaware of the victim's situation or unable to offer as ...

.

The 1882 lynchings are well described in Murray Morgan's book ''Skid Road''. The events involved a mob defying an armed sheriff, successfully disarming the sheriff's deputies, and assaulting Judge Roger Sherman Greene, who attempted to slash the ropes by which the lynching victims were to be hanged. Judge Greene, while not doubting the actual guilt of the lynched men, was later to write that "the lynchers were co-criminal with the lynched".

In an era during which the Washington Territory was one of the first parts of the U.S. to (briefly) allow

The 1882 lynchings are well described in Murray Morgan's book ''Skid Road''. The events involved a mob defying an armed sheriff, successfully disarming the sheriff's deputies, and assaulting Judge Roger Sherman Greene, who attempted to slash the ropes by which the lynching victims were to be hanged. Judge Greene, while not doubting the actual guilt of the lynched men, was later to write that "the lynchers were co-criminal with the lynched".

In an era during which the Washington Territory was one of the first parts of the U.S. to (briefly) allow women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

, Seattle women attempted to counter these trends and to be a civilizing influence. On April 4, 1884, 15 Seattle women founded The Ladies Relief Society to address "the number of needy and suffering cases within the limits of the city". This eventually resulted in the founding of the Seattle Children's Home, still in operation today.

Other signs of encroaching civilization were the city's first bathtub with plumbing in 1870, and first streetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport a ...

in 1884, followed by a cable car from downtown over First Hill to Leschi Park

Leschi Park is an park in the Leschi neighborhood of Seattle, Washington, named after Chief Leschi of the Nisqually tribe. The majority of the park is a grassy hillside that lies west of Lakeside Avenue S. and features tennis courts, picni ...

in 1887. In 1885, the city passed an ordinance requiring attached sewer lines for all new residences. In 1886, the city got its first YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

gymnasium, and in 1888 the exclusive Rainier Club

The Rainier Club is a private club in Seattle, Washington; it has been referred to as "Seattle's preeminent private club."Priscilla LongGentlemen organize Seattle's Rainier Club on February 23, 1888 HistoryLink.org, January 27, 2001. Accessed onli ...

was founded. On December 24, 1888, ferry

A ferry is a ship, watercraft or amphibious vehicle used to carry passengers, and sometimes vehicles and cargo, across a body of water. A passenger ferry with many stops, such as in Venice, Italy, is sometimes called a water bus or water ta ...

service was inaugurated, connecting Seattle to West Seattle

West Seattle is a conglomeration of neighborhoods in Seattle, Washington, United States. It comprises two of the thirteen districts, Delridge and Southwest, and encompasses all of Seattle west of the Duwamish River. It was incorporated as an i ...

, near the location of the Denny Party's first attempt at settling at Alki and reviving that settlement. A year later, a bridge was built across Salmon Bay

Salmon Bay is a portion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, which passes through the city of Seattle, linking Lake Washington to Puget Sound, lying west of the Fremont Cut. It is the westernmost section of the canal and empties into Puget Sound ...

, providing a land route to the nearby town of Ballard, which after 17 years would be annexed to Seattle.

The relative fortunes of Seattle and Tacoma clearly show the nature of Seattle's growth. Though both Seattle and Tacoma grew at a rapid rate from 1880 to 1890, based on the strength of their timber industries, Seattle's growth as an exporter of services and manufactured goods continued for another two decades, while Tacoma's growth dropped almost to zero. The reason for this lies in Tacoma's nature as a company town and Seattle's successful avoidance of that condition.

Both Seattle and Tacoma in the 1880s were essentially lumber towns, built on the resulting export income. All over the Puget Sound there are communities that started with the same assets, timber and a port. However, Seattle's early lead with Yesler's mill and other enterprises meant that its economy was based on manufacturing as well as lumber, and was thus far more diversified than Tacoma's. The Northern Pacific Railway terminus only increased Tacoma's lumber trade instead of diversifying the economy. Meanwhile, Seattle became the hub for the region and the railroad ''had'' to come.

Relations between whites and Chinese

Chinese first arrived in Seattle around 1860. The Northern Pacific Railway completed the project of laying tracks fromLake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

to Tacoma, Washington

Tacoma ( ) is the county seat of Pierce County, Washington, United States. A port city, it is situated along Washington's Puget Sound, southwest of Seattle, northeast of the state capital, Olympia, and northwest of Mount Rainier National Pa ...

, in 1883, leaving many Chinese laborers without employment. In 1883, Chinese laborers played a key role in the first effort at digging the Montlake Cut to connect Lake Union

Lake Union is a freshwater lake located entirely within the city limits of Seattle, Washington, United States. It is a major part of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, which carries fresh water from the much larger Lake Washington on the east to P ...

's Portage Bay

Portage Bay is a body of water, often thought of as the eastern arm of Lake Union, that forms a part of the Lake Washington Ship Canal in Seattle, Washington.

To the east, Portage Bay is connected with Union Bay—a part of Lake Washington— ...

to Lake Washington

Lake Washington is a large freshwater lake adjacent to the city of Seattle.

It is the largest lake in King County and the second largest natural lake in the state of Washington, after Lake Chelan. It borders the cities of Seattle on the west, ...

's Union Bay.

Seattle's Chinese district, located near the present day Occidental Park, was a mixed neighborhood of residences over stores, laundries, and other retail storefronts. In fall 1885, with a shortage of jobs in the West, many workers turned violently anti-Chinese, complaining of overly cheap labor competition. In the Pacific Northwest, this had the unusual character that the anti-Chinese mobs included significant numbers of the native Indians as well as European-Americans.

The first massacre of Chinese occurred at Rock Springs, Wyoming

Rock Springs is a city in Sweetwater County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 23,036 at the 2010 census, making it the fifth most populated city in the state of Wyoming, and the most populous city in Sweetwater County. Rock Springs is ...

, September 2, 1885. On September 7, Chinese hop-pickers were massacred in the Squak valley near present-day Issaquah

Issaquah ( ) is a city in King County, Washington, United States. The population was 40,051 at the 2020 census. Located in a valley and bisected by Interstate 90, the city is bordered by the Sammamish Plateau to the north and the " Issaquah Al ...

. Similar incidents occurred in the nearby mining camps at Coal Creek and Black Diamond. Many Chinese headed from these isolated rural areas into the cities, but it did them little good: on October 24, a mob burned a large portion of Seattle's Chinatown; on November 3, a mob of 300 expelled the Chinese in Tacoma (loading them into boxcars with surprisingly little actual violence) before moving on to force similar expulsions in smaller towns.

Violent opposition to the Chinese at this time was inseparable from labor union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (s ...

organizing. The pro-labor ''Seattle Call'' routinely described the Chinese in brutally racist terms; leading figures in the anti-Chinese movement included Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

organizer Dan Cronin and Seattle socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

agitator Mary Kenworthy; the utopian socialist

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

George Venable Smith was also of this party. Nor did the Chinese have many strong defenders among the wealthier classes, who, however, mostly favored a more orderly departure of the Chinese to massacre and riot (the policy of Henry Yesler, who was serving as mayor at this time).

Among the few defenders of the rule of law were the Methodist Episcopal Ministers' Association and Judge Thomas Burke. Burke, an

Among the few defenders of the rule of law were the Methodist Episcopal Ministers' Association and Judge Thomas Burke. Burke, an Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

immigrant and generally a friend of labor, was nonetheless a stronger defender of the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

; he also spoke out that his fellow Irish should identify with the Chinese as fellow immigrants, a view which fell almost entirely on deaf ears.

On February 7, 1886, well-organized anti-Chinese "order committees" descended on Seattle's Chinatown, claiming to be health inspectors, declaring Chinese-occupied buildings to be unfit for habitation, rousting out the residents and herding them down to the harbor, where the ''Queen of the Pacific'' was docked. The police were willing to intervene only to the point of preventing the Chinese from being physically harmed, not to challenging the mob. It is quite probable that if ship's captain Jack Alexander had been willing simply to board the Chinese and take them away, the mob would entirely have ruled the day; however, he was not in the business of hauling non-paying passengers. The mob raised several hundred dollars, 86 Chinese were boarded, but this delay gave the mayor, Judge Burke, the U.S. Attorney, and others time both to rally the Home Guard and to serve Alexander with a writ of ''habeas corpus''. A plot to deport the Chinese by rail was foiled when Sheriff McGraw threatened to prosecute the railroad superintendent for kidnapping.

The following day, Judge Greene made it clear that those Chinese who wished to remain would be protected, but by now, after what they had been through, all but sixteen preferred to leave. Alexander, by now, "was anxious to keep his operations strictly legal", and would board only the 196 passengers for which his ship was rated, slightly more than half of the Chinese who were ready to leave. Possibly due to poor communication, the anti-Chinese faction were unsatisfied; a resulting scuffle resulted in one dead and four others wounded among the anti-Chinese faction, and martial law was imposed. Ultimately, the bulk of the Chinese remained in Seattle, and the U.S. government "out of humane consideration and without reference to liability" paid out $276,619.15 to the Chinese government, but nothing to the victims themselves.

The Great Seattle Fire

The early Seattle era came to a stunning halt with theGreat Seattle Fire

The Great Seattle Fire was a fire that destroyed the entire central business district of Seattle, Washington on June 6, 1889. The conflagration lasted for less than a day, burning through the afternoon and into the night, and during the same sum ...

of June 6, 1889. It burned 29 city blocks, destroying most of the central business district

A central business district (CBD) is the commercial and business centre of a city. It contains commercial space and offices, and in larger cities will often be described as a financial district. Geographically, it often coincides with the "city ...

; no one, however, perished in the flames, and the city quickly rebounded from the destruction. Thanks in part to credit arranged by Jacob Furth (as well as, according to Speidel, brothel-owner Lou Graham

Louis Krebs Graham (born January 7, 1938) is an American professional golfer who won six PGA Tour tournaments including the 1975 U.S. Open. Most of his wins were in the 1970s.

Lou Graham was born in Nashville, Tennessee. He started playing go ...

), Seattle rebuilt from the ashes with astounding rapidity. A new zoning

Zoning is a method of urban planning in which a municipality or other tier of government divides land into areas called zones, each of which has a set of regulations for new development that differs from other zones. Zones may be defined for a si ...

code resulted in a downtown of brick and stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

buildings, rather than wood. In the single year after the fire, the city grew from 25,000 to 40,000 inhabitants, largely because of the enormous number of construction jobs suddenly created.

Labor history in 19th century Seattle

The Pacific Northwest economy during the nineteenth century was heavily rooted inextractive industries

Extractivism is the process of extracting natural resources from the Earth to sell on the world market. It exists in an economy that depends primarily on the extraction or removal of natural resources that are considered valuable for exportation w ...

, mainly logging. Still, Seattle was becoming a city, and union organizing arrived first in the form of a skilled craft union. In 1882, Seattle printers formed the Seattle Typographical Union Local 202. Dockworkers followed in 1886, cigar

A cigar is a rolled bundle of dried and fermented tobacco leaves made to be smoked. Cigars are produced in a variety of sizes and shapes. Since the 20th century, almost all cigars are made of three distinct components: the filler, the binder l ...

makers in 1887, tailors in 1889, and both brewers and musicians in 1890. Even the newsboys unionized in 1892, followed by more organizing, mostly of craft unions.

According to various analyses and as evident through general readings in news coverage of the time, the history of labor in this period is inseparable from the issue of anti-Chinese vigilantism, as discussed above. A rough-and-ready approach to labor organizing was typical of the period, and there is no question that white Seattle-area laborers at this time saw cheap Chinese labor as their prime competition and strove to eliminate it by eliminating the Chinese immigrants.

The Klondike Gold Rush

Seattle, as well as the rest of the nation, was hard hit by the

Seattle, as well as the rest of the nation, was hard hit by the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

and, to a lesser extent, the Panic of 1896. Unlike many other cities, it soon found salvation in the form of becoming the main transportation and supply center for stampeders heading for the Klondike gold rush. When the steamer SS ''Portland'' arrived at Schwabacher's Wharf in Seattle July 17, 1897, the ''Seattle Post-Intelligencer

The ''Seattle Post-Intelligencer'' (popularly known as the ''Seattle P-I'', the ''Post-Intelligencer'', or simply the ''P-I'') is an online newspaper and former print newspaper based in Seattle, Washington, United States.

The newspaper was fo ...

'' scooped all other U.S. newspapers with the story that a "ton of gold" had arrived from Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

. A publicity campaign engineered largely by Erastus Brainerd

Erastus Brainerd (25 February 1855 – 25 December 1922) was an American journalist and art museum curator. During the Yukon Gold Rush, he was the publicist who "sold the idea that Seattle was the Gateway to Alaska and the ''only'' such portal".' ...

successfully convinced the world that Seattle was the place to be outfitted for the journey to Alaska, and Seattle became a household name, literally overnight. The miners mined the gold. Seattle mined the miners.

Seattle's relationship with Alaska during this period was generally one of rapacity. Besides the mining, on October 18, 1899 in Pioneer Square, a Chamber of Commerce "Committee of Fifteen", just back from a goodwill visit to Alaska, proudly unveiled a totem pole

Totem poles ( hai, gyáaʼaang) are monumental carvings found in western Canada and the northwestern United States. They are a type of Northwest Coast art, consisting of poles, posts or pillars, carved with symbols or figures. They are usually ...

from Fort Tongass

Fort Tongass was a United States Army base on Tongass Island, in the southernmost Alaska Panhandle, located adjacent to the village of the group of Tlingit people on the east side of the island.

. The problem was, the pole had been stolen from the Tlingit

The Tlingit ( or ; also spelled Tlinkit) are indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their language is the Tlingit language (natively , pronounced ),

village of Gaash on Cape Fox. A federal grand jury in Alaska indicted eight of Seattle's most prominent citizens for theft of government property. A nominal fine was assessed.(1) Wilma (1 January 2000, Essay 2076) The village was repaid when the original burned and the Chamber of Commerce commissioned a replacement—and paid twice. "Thank you for the check", wrote the Gaash village leaders. "That was payment for the first one. Send another check for the replacement".

See also

*Duwamish tribe

The Duwamish ( lut, Dxʷdəwʔabš, ) are a Lushootseed-speaking Native American tribe in western Washington, and the indigenous people of metropolitan Seattle, where they have been living since the end of the last glacial period (c. 8000 BCE ...

* Mother Damnable

* Rock Springs massacre

The Rock Springs massacre, also known as the Rock Springs riot, occurred on September 2, 1885, in the present-day United States city of Rock Springs in Sweetwater County, Wyoming. The riot, and resulting massacre of immigrant Chinese miner ...

* Timeline of Seattle, 19th century

Notes and references

Much of the content of this page is from "Seattle: Booms and Busts", by Emmett Shear; Shear has granted blanket permission for material from that paper to be reused in Wikipedia.Bibliography

*and * * *

Page links t

Village Descriptions Duwamish-Seattle section

Dailey referenced "Puget Sound Geography" by T. T. Waterman. Washington DC: National Anthropological Archives, mss. .d.

ef. 2

EF or ef may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Ef (band), a post-rock band from Sweden

* '' Ef: A Fairy Tale of the Two.'', a Japanese adult visual novel series by Minori, or its anime adaptations

Businesses and organizations

* Eagle Forum

...

''Duwamish et al. vs. United States of America, F-275''. Washington DC: US Court of Claims, 1927. ef. 5

"Indian Lake Washington" by David Buerge in the ''Seattle Weekly'', 1–7 August 1984

ef. 8

EF or ef may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Ef (band), a post-rock band from Sweden

* '' Ef: A Fairy Tale of the Two.'', a Japanese adult visual novel series by Minori, or its anime adaptations

Businesses and organizations

* Eagle Forum, an ...

"Seattle Before Seattle" by David Buerge in the ''Seattle Weekly'', 17–23 December 1980.

ef. 9

EF or ef may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Ef (band), a post-rock band from Sweden

* '' Ef: A Fairy Tale of the Two.'', a Japanese adult visual novel series by Minori, or its anime adaptations

Businesses and organizations

* Eagle Forum, a ...

''The Puyallup-Nisqually'' by Marian W. Smith. New York: Columbia University Press, 1940.

ef. 10

EF or ef may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Ef (band), a post-rock band from Sweden

* '' Ef: A Fairy Tale of the Two.'', a Japanese adult visual novel series by Minori, or its anime adaptations

Businesses and organizations

* Eagle Forum, an ...

Recommended start i

"Coast Salish Villages of Puget Sound"

* *

2d edition of vol. I of III * *

Lange referenced a very extensive list.

Summary article **

Lange referenced Lange, "Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 among Northwest Coast and Puget Sound Indians

HistoryLink.org ''Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History''. Accessed 8 December 2000. * * * * * *

Speidel provides a substantial bibliography with extensive primary sources. *

Speidel provides a substantial bibliography with extensive primary sources. * . * *

Wilma referenced "Petition: To the Honorable Arthur A. Denny, Delegate to Congress from Washington Territory," n.d., National Archives Roll 909, "Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-81";

Pioneer Association of the State of Washington, "A Petition to Support Recognition of The Duwamish Indians as a 'Tribe', June 18, 1988, in possession of Ken Tollefson, Seattle, Washington. * {{cite web , last =Wilma , first =David , date =2000-01-01 , url=http://www.historylink.org/essays/output.cfm?file_id=2076 , title =Stolen totem pole unveiled in Seattle's Pioneer Square on October 18, 1899 , work =HistoryLink.org Essay 2076 , publisher =Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Seattle Unit , access-date =2006-07-16

Wilam referenced Paul Dorpat, ''Seattle Now and Then Vol. 2'' (Seattle: Tartu Publications, 1984), 32-35;

Joseph H. Wherry, ''The Totem Pole Indians'', (New York: Wilfred Funk, Inc., 1964), 64, 89;

William C. Speidel, ''Sons of the Profits'' (Seattle: Nettle Creek Publishing Co., 1967), 329-331;

Viola Garfield, ''Seattle's Totem Poles'' (Bellevue, WA: Thistle Press, 1996), 9;

Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation, ''Data on the History of Seattle Park System Vol. 4'' (Seattle: Seattle Parks Department, 1978);

James William Clise, "Personal Memoirs 1855-1935" Mimeograph, Altadena, California, 1935, Seattle Public Library.

Further reading

* HistoryLink.org ''Encyclopedia of Washington State History'provides a collection of articles on Seattle and Washington State history, unparalleled in its niche. * Seattl

Museum of History and Industry

With the Seattle Room at the

Seattle Public Library

The Seattle Public Library (SPL) is the public library system serving the city of Seattle, Washington. Efforts to start a Seattle library had commenced as early as 1868, with the system eventually being established by the city in 1890. The syst ...

, these host the most extensive archives about Seattle.

Washington State History Museum

Washington State Historical Society

University of Washington Libraries: Digital Collections

*

88 photographs, c. 1888–1893, of early Seattle, including the waterfront and street scenes, Madrona and Leschi parks, Native American hop pickers, scenes of the aftermath of the

Great Seattle Fire

The Great Seattle Fire was a fire that destroyed the entire central business district of Seattle, Washington on June 6, 1889. The conflagration lasted for less than a day, burning through the afternoon and into the night, and during the same sum ...

of June 6, 1889, and portraits of Seattle pioneers.

*Frank La Roche Photographs

312 photographs c. 1888-1910 depicting scenes of the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush, A small photograph album (ca. 1891) used as a sales tool. Photographed by Frank La Roche, it contains an historical photographic record of early Seattle and its expansion northwards along the shores of

Lake Union

Lake Union is a freshwater lake located entirely within the city limits of Seattle, Washington, United States. It is a major part of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, which carries fresh water from the much larger Lake Washington on the east to P ...

, Seattle, Washington state, Alaska, western United States, and Canada.

*Theodore E. Peiser Photographs

140 images from the later part of the 19th century to about 1907. Among his subjects were images of troops preparing to embark from

Fort Lawton

Fort Lawton was a United States Army post located in the Magnolia neighborhood of Seattle, Washington overlooking Puget Sound. In 1973 a large majority of the property, 534 acres of Fort Lawton, was given to the city of Seattle and dedicated as ...

to China in 1900, the Territorial University (later University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seatt ...

), and early Seattle scenes.

*Prosch Seattle Views Album

169 images by Thomas Prosch, one of Seattle's earliest pioneers, documenting the early history of Seattle and vicinity, c. 1851–1906.

Ongoing database of over 1,700 historical photographs of Seattle with special emphasis on images depicting neighborhoods, recreational activities including baseball, the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, "The Great Snow of 1916", theaters and transportation. *

Images by the pioneer photographer A.C. Warner, from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, of Seattle conventional street scenes, waterfront activity, city parks, and

regrading

Grading in civil engineering and landscape architectural construction is the work of ensuring a level base, or one with a specified slope, for a construction work such as a foundation, the base course for a road or a railway, or landscape a ...

of downtown.

a

Seattle a