History of Saint Lucia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Saint Lucia was inhabited by the

Saint Lucia was inhabited by the

In 1605, an English vessel called the ''Oliphe Blossome'' was blown off-course on its way to Guyana, and the 67 colonists started a settlement on Saint Lucia, after initially being welcomed by the Carib chief Anthonie. By 26 Sept. 1605, only 19 survived, after continued attacks by the Carib chief Augraumart, so they fled the island. In 1626, the

In 1605, an English vessel called the ''Oliphe Blossome'' was blown off-course on its way to Guyana, and the 67 colonists started a settlement on Saint Lucia, after initially being welcomed by the Carib chief Anthonie. By 26 Sept. 1605, only 19 survived, after continued attacks by the Carib chief Augraumart, so they fled the island. In 1626, the

During the

During the

Website for the Permanent Mission of St. Lucia to the United Nations: ''History of Saint Lucia''

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia was inhabited by the

Saint Lucia was inhabited by the Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Great ...

and Kalinago

The Kalinago, also known as the Island Caribs or simply Caribs, are an indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. They may have been related to the Mainland Caribs (Kalina) of South America, but they spoke an unrelated langua ...

Caribs before European contact in the early 16th century. It was colonized by the British and French in the 17th century and was the subject of several possession changes until 1814, when it was ceded to the British by France for the final time. In 1958, St. Lucia joined the short-lived semi-autonomous West Indies Federation

The West Indies Federation, also known as the West Indies, the Federation of the West Indies or the West Indian Federation, was a short-lived political union that existed from 3 January 1958 to 31 May 1962. Various islands in the Caribbean that ...

. Saint Lucia was an associated state of the United Kingdom from 1967 to 1979 and then gained full independence on February 22, 1979.

Pre-colonial period

Saint Lucia was first inhabited sometime between 1000 and 500 BC by theCiboney people

The Ciboney, or Siboney, were a Taíno people of western Cuba, Jamaica, and the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti. A Western Taíno group living in central Cuba during the 15th and 16th centuries, they had a dialect and culture distinct from the Ta%C3%AD ...

, but there is not a lot of evidence of their presence on the island. The first proven inhabitants were the peaceful Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Great ...

s, believed to have come from northern South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

around 200-400 AD, as there are numerous archaeological sites on the island where specimens of the Arawaks' well-developed pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

have been found. There is evidence to suggest that these first inhabitants called the island ''Iouanalao'', which meant 'Land of the Iguanas', due to the island's high number of iguana

''Iguana'' (, ) is a genus of herbivorous lizards that are native to tropical areas of Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. The genus was first described in 1768 by Austrian naturalist Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in his ...

s.

The more aggressive Caribs

“Carib” may refer to:

People and languages

*Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of South America

**Carib language, also known as Kalina, the language of the South American Caribs

*Kalinago people, or Island Caribs, an indigenous pe ...

arrived around 800 AD, and seized control from the Arawaks by killing their men and assimilating the women into their own society. They called the island ''Hewanarau'', and later ''Hewanorra'' (Ioüanalao, or "there where iguanas are found"). This is the origin of the name of the Hewanorra International Airport

Hewanorra International Airport , located near Vieux Fort Quarter, Saint Lucia, in the Caribbean, is the larger of Saint Lucia's two airports and is managed by the Saint Lucia Air and Seaports Authority (SLASPA). It is on the southern cape of ...

in Vieux Fort

Vieux Fort is one of 10 districts of the Caribbean island country of Saint Lucia. Vieux Fort is also the name of the main town in the district. It is the home of the second-largest town in Saint Lucia and is the home of Saint Lucia's internati ...

. The Caribs had a complex society, with hereditary kings and shamans

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritu ...

. Their war canoes could hold more than 100 men and were fast enough to catch a sailing ship. They were later feared by the invading Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

ans for their ferocity in battle.

16th century

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

may have sighted the island during his fourth voyage in 1502, since he made landfall on Martinique, yet he does not mention the island in his log. Juan de la Cosa

Juan de la Cosa (c. 1450 – 28 February 1510) was a Castilian navigator and cartographer, known for designing the earliest European world map which incorporated the territories of the Americas discovered in the 15th century.

De la Cosa was th ...

noted the island on his map of 1500, calling it ''El Falcon'', and another island to the south ''Las Agujas''. A Spanish Cedula from 1511 mentions the island within the Spanish domain, and a globe

A globe is a spherical model of Earth, of some other celestial body, or of the celestial sphere. Globes serve purposes similar to maps, but unlike maps, they do not distort the surface that they portray except to scale it down. A model glo ...

in the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

made in 1520, shows the island as ''Sancta Lucia''. A 1529 Spanish map shows ''S. Luzia''.

In the late 1550s the French pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

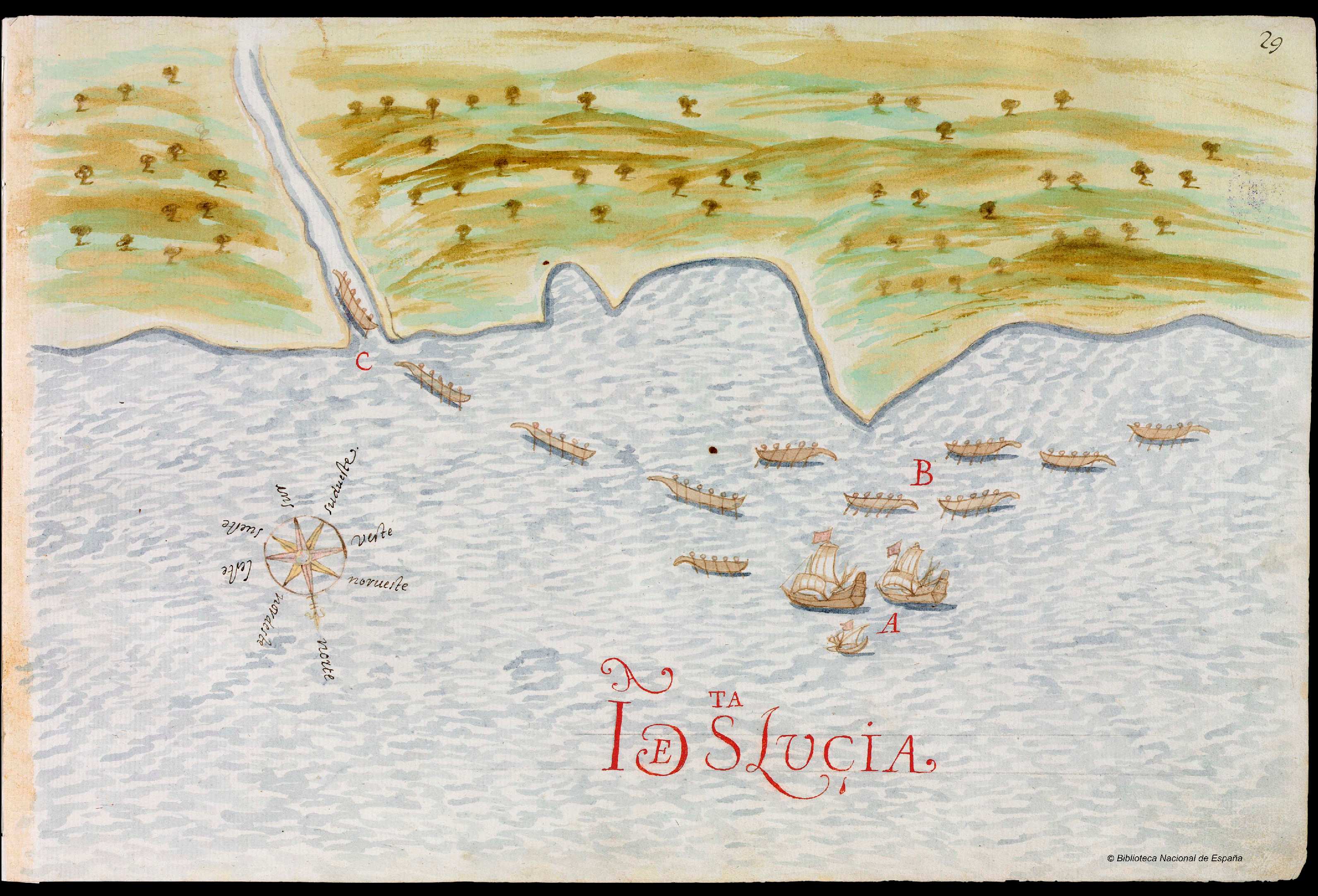

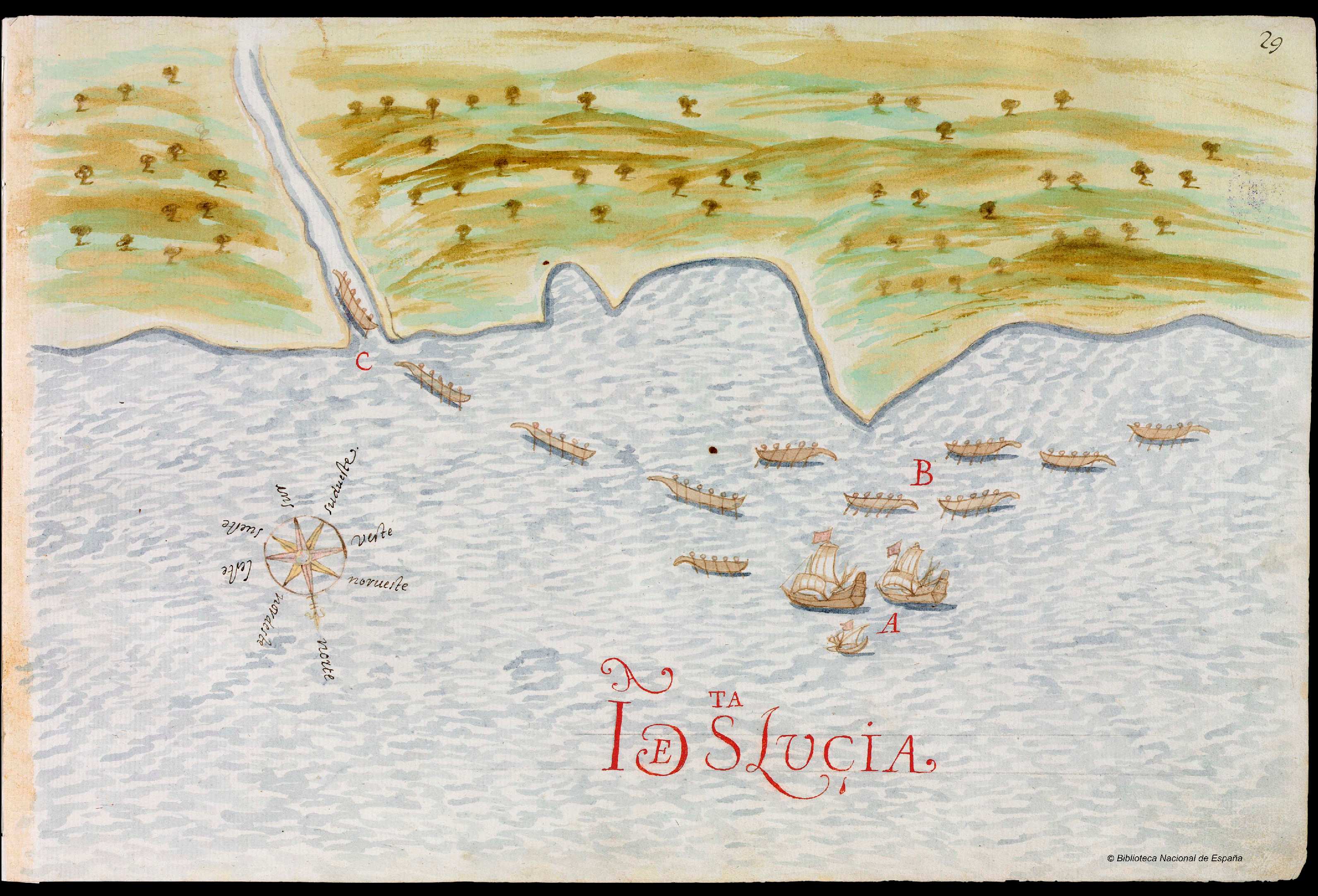

François le Clerc (known as ''Jambe de Bois'', due to his wooden leg) set up a camp on Pigeon Island, from where he attacked passing Spanish ships.

17th century

In 1605, an English vessel called the ''Oliphe Blossome'' was blown off-course on its way to Guyana, and the 67 colonists started a settlement on Saint Lucia, after initially being welcomed by the Carib chief Anthonie. By 26 Sept. 1605, only 19 survived, after continued attacks by the Carib chief Augraumart, so they fled the island. In 1626, the

In 1605, an English vessel called the ''Oliphe Blossome'' was blown off-course on its way to Guyana, and the 67 colonists started a settlement on Saint Lucia, after initially being welcomed by the Carib chief Anthonie. By 26 Sept. 1605, only 19 survived, after continued attacks by the Carib chief Augraumart, so they fled the island. In 1626, the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe The Compagnie de Saint-Christophe was a company created and chartered by French adventurers to exploit the island of Saint-Christophe, the present-day Saint Kitts and Nevis. In 1625, a French adventurer, Pierre Bélain sieur d'Esnambuc, landed on S ...

was chartered by Cardinal Richelieu, chief minister of Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

to colonize the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc bet ...

, between the eleventh and eighteenth parallels. The following year, a royal patent was issued to James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle

James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle KB (c. 1580March 1636) was a British noble.

Life

A Scot, he was the son of Sir James Hay of Fingask, second son of Peter Hay of Megginch (a branch member of Hay of Leys, a younger branch of the Erroll family) a ...

by Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. He was born into the House of Stuart as the second son of King James VI of Scotland, but after hi ...

granting rights over the Caribbean islands situated between 10° and 20° north latitude, creating a competing claim. In 1635, the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe was reorganized under a new patent for the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique The Company of the American Islands (french: Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique) was a French chartered company that in 1635 took over the administration of the French portion of ''Saint-Christophe island'' (Saint Kitts) from the Compagnie de Saint ...

, which gave the company all the properties and administration of the former company and the rights to continue colonizing neighboring vacant islands.

English documents claim colonists from Bermuda settled the island in 1635, while a French letter of patent claims settlement on 8 March 1635 by a Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc

Pierre Belain, sieur d'Esnambuc (; 1585–1636) was a French trader and adventurer in the Caribbean, who established the first permanent French colony, Saint-Pierre, on the island of Martinique in 1635.

Biography Youth

Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc ...

, who was succeeded by his nephew, Jacques Dyel du Parquet

Jacques Dyel du Parquet (1606 – 3 January 1658) was a French soldier who was one of the first governors of Martinique.

He was appointed governor of the island for the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique in 1636, a year after the first French se ...

. Thomas Warner sent Capt. Judlee with 300-400 Englishmen to establish a settlement at Praslin Bay but they were attacked over three weeks by Caribs, until the few remaining colonists fled on 12 October 1640. In 1642, Louis XIII extended the charter of the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique for twenty years. The following year, du Parquet, who had become Governor of Martinique, noted that the British had abandoned Saint Lucia and he began making plans for a settlement. In June 1650, he sent Louis de Kerengoan, Sieur de Rousselan and 40 Frenchmen to establish a fort at the mouth of the Rivière du Carenage, near present day Castries. As the Compagnie was facing bankruptcy, du Parquet sailed to France in September 1650 and purchased the sole proprietorship

A sole proprietorship, also known as a sole tradership, individual entrepreneurship or proprietorship, is a type of enterprise owned and run by one person and in which there is no legal distinction between the owner and the business entity. A sole ...

for Grenada, the Grenadines, Martinique and Sainte-Lucie for ₣41,500. The French drove off an attempted English invasion in 1659, but allowed the Dutch to build a redoubt near Vieux Fort Bay in 1654. On 6 April 1663, the Caribs sold St. Lucia to Francis Willoughby, 5th Baron Willoughby of Parham

Francis Willoughby, 5th Baron Willoughby of Parham (baptised 1614; died 23 July 1666 O.S., 2 August 1666 N.S.) was an English peer of the House of Lords.

He succeeded to the title on 14 October 1617 on the death in infancy of his elder brother ...

, English governor of the Caribbean. He invaded the island with 1100 Englishmen and 600 Amerindians in 5 ships-of-war and 17 pirogue

A pirogue ( or ), also called a piragua or piraga, is any of various small boats, particularly dugouts and native canoes. The word is French and is derived from Spanish , which comes from the Carib '. Description

The term 'pirogue' does n ...

s forcing the 14 French defenders to flee.

However, the English colony succumbed to disease. The French took over again, but the English came back in June 1664 and retained possession until 20 Oct. 1665 when diplomacy gave the island back to the French. The English invaded again in 1665, but disease, famine and the Caribs forced their fleeing in Jan. 1666. The Treaty of Breda (1667)

The Peace of Breda, or Treaty of Breda was signed in the Dutch city of Breda, on 31 July 1667. It consisted of three separate treaties between England and each of its opponents in the Second Anglo-Dutch War: the Dutch Republic, France, and Denma ...

gave control of the island back to the French. The English raided the island in 1686, but relinquished all claims in a 1687 treaty and the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick

The Peace of Ryswick, or Rijswijk, was a series of treaties signed in the Dutch city of Rijswijk between 20 September and 30 October 1697. They ended the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War between France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Gran ...

.

18th century

Both the British, with their headquarters inBarbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate) ...

, and the French, centered on Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

, found Saint Lucia attractive after the slave-based sugar industry developed in 1763, and during the 18th century the island changed ownership or was declared neutral territory a dozen times, although the French settlements remained and the island was a de facto a French colony well into the 18th century.

In 1722, the George I of Great Britain

George I (George Louis; ; 28 May 1660 – 11 June 1727) was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 and ruler of the Electorate of Hanover within the Holy Roman Empire from 23 January 1698 until his death in 1727. He was the first ...

granted both Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent to John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu

John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu, (1690 – 5 July 1749), styled Viscount Monthermer until 1705 and Marquess of Monthermer between 1705 and 1709, was a British peer.

Life

Montagu was an owner of a coal mine.

Montagu went on the grand tour wi ...

. He in turn appointed Nathaniel Uring, a merchant sea captain and adventurer, as deputy-governor. Uring went to the islands with a group of seven ships, and established settlement at Petit Carenage. Unable to get enough support from British warships, he and the new colonists were quickly run off by the French.

The 1730 census showed 463 occupants of the island, which included just 125 whites, 37 Caribs, 175 slaves, and the rest free blacks or mixed race. The French took control of the island in 1744, and by 1745, the island had a population of 3455, including 2573 slaves.

During the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

Britain occupied Saint Lucia in 1762, but gave the island back at the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

on 10 February 1763. Britain occupied the island again in 1778 after the Grand Battle of Cul de Sac during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. British Admiral George Rodney

Admiral George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron Rodney, KB ( bap. 13 February 1718 – 24 May 1792), was a British naval officer. He is best known for his commands in the American War of Independence, particularly his victory over the French at th ...

then built Fort Rodney from 1779 to 1782.

By 1779, the island's population had increased to 19,230, which included 16,003 slaves working 44 sugar plantations. Yet, the Great Hurricane of 1780

The Great Hurricane of 1780 was the deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record. An estimated 22,000 people died throughout the Lesser Antilles when the storm passed through the islands from October 10 to October 16. Specifics on the hurricane's tra ...

killed about 800. By the time the island was restored to French rule in 1784, as a consequence of the Peace of Paris (1783)

The Peace of Paris of 1783 was the set of treaties that ended the American Revolutionary War. On 3 September 1783, representatives of King George III of Great Britain signed a treaty in Paris with representatives of the United States of America� ...

, 300 plantations had been abandoned and some thousand maroons

Maroons are descendants of Africans in the Americas who escaped from slavery and formed their own settlements. They often mixed with indigenous peoples, eventually evolving into separate creole cultures such as the Garifuna and the Mascogos.

...

lived in the interior.

In Jan. 1791, during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

sent four ''Commissaries'' to St. Lucia to spread the revolution philosophy. By August, slaves began to abandon their estates and Governor de Gimat fled. In Dec. 1792, Lt. Jean-Baptiste Raymond de Lacrosse arrived with revolutionary pamphlets, and the poor whites and free people of color began to arm themselves as ''patriots''. On 1 Feb. 1793, France declared war on England and Holland, and General Nicolas Xavier de Ricard took over as Governor. The National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nationa ...

abolished enslavement on 4 Feb. 1794, but St. Lucia fell to a British invasion led by Vice Admiral John Jervis on 1 April 1794. Morne Fortune

Morne Fortune is a hill and residential area located south of Castries, Saint Lucia, in the West Indies.

Originally known as Morne Dubuc, it was renamed Morne Fortuné in 1765 when the French moved their military headquarters and government admi ...

became ''Fort Charlotte''. Soon, a patriot army of resistance, ''L'Armee Francaise dans les Bois'', began to fight back. Thus started the First Brigand War.

A short time later, the British invaded in response to the concerns of the wealthy plantation owners, who wanted to keep sugar production going. On 21 February 1795, a group of rebels, led by Victor Hugues

Jean-Baptiste Victor Hugues sometimes spelled Hughes (July 20, 1762 in Marseille – August 12, 1826 in Cayenne) was a French politician and colonial administrator during the French Revolution, who governed Guadeloupe from 1794 to 1798, emancipa ...

, defeated a battalion of British troops. For the next four months, a group of recently freed slaves known as the Brigands forced out not only the British army, but every white slave-owner from the island (coloured slave owners were left alone, as in Haiti). The English were eventually defeated on June 19, and fled from the island. The Royalist planters fled with them, leaving the remaining Saint Lucians to enjoy “l’Année de la Liberté”, “a year of freedom from slavery…”. Gaspard Goyrand, a Frenchman who was Saint Lucia's Commissary later became Governor of Saint Lucia, and proclaimed the abolition of slavery. Goyrand brought the aristocratic planters to trial. Several lost their heads on the guillotine, which had been brought to Saint Lucia with the troops. He then proceeded to re-organize the island.

The British continued to harbor hopes of recapturing the island and in April 1796 Sir Ralph Abercrombie and his troops attempted to do so. Castries was burned as part of the conflict, and after approximately one month of bitter fighting the French surrendered at Morne Fortune on 25 May. General Moore was elevated to the position of Governor of Saint Lucia by Abercrombie and was left with 5,000 troops to complete the task of subduing the entire island.

British Brig. Gen. John Moore was appointed Military Governor on 25 May 1796, and engaged in the Second Brigand War. Some ''Brigands'' began to surrender in 1797, when promised they would not be returned to slavery. Final freedom and the end to hostilities came with Emancipation in 1838.''They Called Us the Brigands. The Saga of St. Lucia's Freedom Fighters'' by Robert J Devaux

19th century

The 1802Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it s ...

restored the island to French control, and Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

reinstated slavery. The British regained the island in June 1803, when Commodore Samuel Hood defeated French Governor Brig. Gen. Antoine Noguès. The island was officially ceded to Britain in 1814.

Also in 1838, Saint Lucia was incorporated into the British Windward Islands

french: Îles du Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Windward Islands. Clockwise: Dominica, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Grenada.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean Sea No ...

administration, headquartered in Barbados. This lasted until 1885, when the capital was moved to Grenada.

20th century to 21st century

During the

During the Battle of the Caribbean

The Battle of the Caribbean refers to a naval campaign waged during World War II that was part of the Battle of the Atlantic, from 1941 to 1945. German U-boats and Italian submarines attempted to disrupt the Allied supply of oil and other ma ...

, a German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

attacked and sank two British ships in Castries harbor on 9 March 1942.

Increasing self-government has marked St Lucia's 20th-century history. A 1924 constitution gave the island its first form of representative government, with a minority of elected members in the previously all-nominated legislative council. Universal adult suffrage was introduced in 1951, and elected members became a majority of the council. Ministerial government was introduced in 1956, and in 1958 St. Lucia joined the short-lived West Indies Federation

The West Indies Federation, also known as the West Indies, the Federation of the West Indies or the West Indian Federation, was a short-lived political union that existed from 3 January 1958 to 31 May 1962. Various islands in the Caribbean that ...

, a semi-autonomous dependency of the United Kingdom. When the federation collapsed in 1962, following Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

's withdrawal, a smaller federation was briefly attempted. After the second failure, the United Kingdom and the six windward and leeward islands—Grenada, St. Vincent, Dominica, Antigua, St. Kitts and Nevis and Anguilla

Anguilla ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin. The terr ...

, and St. Lucia—developed a novel form of cooperation called associated statehood.

By 1957, bananas exceed sugar as the major export crop.

As an associated state of the United Kingdom from 1967 to 1979, St. Lucia had full responsibility for internal self-government but left its external affairs and defence responsibilities to the United Kingdom. This interim arrangement ended on February 22, 1979, when St. Lucia achieved complete independence. St. Lucia is a Constitutional Monarch

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

with King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

as King of St. Lucia and is an active member of the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

. The island continues to cooperate with its neighbours through the Caribbean community and common market ( CARICOM), the East Caribbean Common Market (ECCM), and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS; French: ''Organisation des États de la Caraïbe orientale'', OECO) is an inter-governmental organisation dedicated to economic harmonisation and integration, protection of human and legal ri ...

(OECS).

See also

* British colonization of the Americas *French colonization of the Americas

France began colonizing the Americas in the 16th century and continued into the following centuries as it established a colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere. France established colonies in much of eastern North America, on several Caribbe ...

*History of the Americas

The prehistory of the Americas (North, South, and Central America, and the Caribbean) begins with people migrating to these areas from Asia during the height of an ice age. These groups are generally believed to have been isolated from the peopl ...

* History of the British West Indies

*History of North America

History of North America encompasses the past developments of people populating the continent of North America. While it was widely believed that continent first became a human habitat when people migrated across the Bering Sea 40,000 to 17,0 ...

*History of the Caribbean

The history of the Caribbean reveals the significant role the region played in the colonial struggles of the European powers since the 15th century. In 1492, Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean and claimed the region for Spain. The ...

* List of colonial governors of Saint Lucia

* List of prime ministers of Saint Lucia

*Politics of Saint Lucia

Politics of Saint Lucia takes place in the framework of an independent parliamentary democratic constitutional monarchy, with King Charles III as its head of state, represented by a Governor General, who acts on the advice of the prime ministe ...

* Spanish colonization of the Americas

References

* * * * * * *Further reading

*Website for the Permanent Mission of St. Lucia to the United Nations: ''History of Saint Lucia''

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Saint Lucia