The history of the Catholic Church in Mexico dates from the period of the Spanish conquest (1519–21) and has continued as an institution in Mexico into the twenty-first century. Catholicism is one of many major legacies from the Spanish colonial era, the others include Spanish as the nation's language, the

Civil Code

A civil code is a codification of private law relating to property, family, and obligations.

A jurisdiction that has a civil code generally also has a code of civil procedure. In some jurisdictions with a civil code, a number of the core ar ...

and Spanish colonial architecture. The Catholic Church was a privileged institution until the mid nineteenth century. It was the sole permissible church in the colonial era and into the early Mexican Republic, following independence in 1821. Following independence, it involved itself directly in politics, including in matters that did not specifically involve the Church.

In the mid-nineteenth century the liberal

Reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

brought major changes in church-state relations. Mexican liberals in power challenged the Catholic Church's role, particularly in reaction to its involvement in politics.

[Roderic Ai Camp, ''Crossing Swords: Politics and Religion in Mexico''. Oxford University Press 1997, p. 25.] The Reform curtailed the Church's role in

education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

, property ownership, and control of birth, marriage, and death records, with specific anticlerical laws. Many of these were incorporated into the

Constitution of 1857

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1857 ( es, Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos de 1857), often called simply the Constitution of 1857, was the liberal constitution promulgated in 1857 by Constituent Co ...

, restricting the Church's corporate ownership of property and other limitations. Although there were some liberal clerics who advocated reform, such as

José María Luis Mora

José María Luis Mora Lamadrid (12 October 1794, Chamacuero, Guanajuato – 14 July 1850, Paris, France) was a priest, lawyer, historian, politician and liberal ideologist. Considered one of the first supporters of liberalism in Mexico, he fou ...

, the Church came to be seen as conservative and anti-revolutionary.

During the bloody

War of the Reform

The Reform War, or War of Reform ( es, Guerra de Reforma), also known as the Three Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Tres Años), was a civil war in Mexico lasting from January 11, 1858 to January 11, 1861, fought between liberals and conservativ ...

, the Church was an ally of conservative forces that attempted to oust the liberal government. They also were associated with the conservatives' attempt to regain power during the

French Intervention

This is a list of wars involving France and its predecessor states. It is an incomplete list of French and proto-French wars and battles from the foundation of Frankish Kingdom, Francia by Clovis I, the Merovingian dynasty, Merovingian king who uni ...

, when

Maximilian of Habsburg

Maximilian I (german: Ferdinand Maximilian Josef Maria von Habsburg-Lothringen, link=no, es, Fernando Maximiliano José María de Habsburgo-Lorena, link=no; 6 July 1832 – 19 June 1867) was an Austrian archduke who reigned as the only Emperor ...

was invited to become emperor of Mexico. The empire fell and conservatives were discredited, along with the Catholic Church. However, during the long presidency of

Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori ( or ; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915), known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 Decem ...

(1876–1911) the liberal general pursued a policy of conciliation with the Catholic Church; though he kept the anticlerical articles of the liberal constitution in force, he in practice allowed greater freedom of action for the Catholic Church. With Díaz's ouster in 1911 and the decade-long conflict of the

Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

, the victorious Constitutionalist faction led by

Venustiano Carranza

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (; 29 December 1859 – 21 May 1920) was a Mexican wealthy land owner and politician who was Governor of Coahuila when the constitutionally elected president Francisco I. Madero was overthrown in a February ...

wrote the new

Constitution of 1917

The Constitution of Mexico, formally the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States ( es, Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the current constitution of Mexico. It was drafted in Santiago de Querétaro, in th ...

that strengthened the anticlerical measures in the liberal Constitution of 1857.

With the presidency of Northern, anticlerical, revolutionary general

Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a general in the Mexican Revolution and a Sonoran politician, serving as President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928.

The 1924 Calles presidential campaign was the first populist ...

(1924–28), the State's enforcement of the

anticlerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

articles of Constitution of 1917 provoked a major crisis with violence in a number of regions of Mexico. The

Cristero Rebellion

The Cristero War ( es, Guerra Cristera), also known as the Cristero Rebellion or es, La Cristiada, label=none, italics=no , was a widespread struggle in central and western Mexico from 1 August 1926 to 21 June 1929 in response to the implementa ...

(1926–29) was resolved, with the aid of diplomacy of the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, ending the violence, but the anticlerical articles of the constitution remained. President

Manuel Avila Camacho (1940–1946) came to office declaring "I am a

atholicbeliever," (''soy creyente'') and Church-State relations improved though without constitutional changes.

A major change came in 1992, with the presidency of

Carlos Salinas de Gortari

Carlos Salinas de Gortari CYC DMN (; born 3 April 1948) is a Mexican economist and politician who served as 60th president of Mexico from 1988 to 1994. Affiliated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), earlier in his career he wor ...

(1988–1994). In a sweeping program of reform to "modernize Mexico" that he outlined in his 1988 inaugural address, his government pushed through revisions in the Mexican Constitution, explicitly including a new legal framework that restored the Catholic Church's juridical personality.

[Jorge A. Vargas, "Freedom of Religion and Public Worship in Mexico: A Legal Commentary on the 1992 Federal Act on Religious Matters." ''BYU Law Review'' Vol. 1998, issue 2, article 6, pp. 421-481.] The majority of Mexicans in the twenty-first century identify themselves as being Catholic, but the growth of other religious groups such as Protestant

evangelicals

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

,

Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into sever ...

, as well secularism is consistent with trends elsewhere in Latin America. The 1992 federal Act on Religious Associations and Public Worship (''Ley de Asociaciones Religiosas y Culto Público''), known in English as the Religious Associations Act or (RAA), has affected all religious groups in Mexico.

Colonial era (1521–1821)

Early period: The Spiritual Conquest 1519–1572

During the conquest, the Spaniards pursued a dual policy of military conquest, bringing indigenous peoples and territory under Spanish control, and spiritual conquest, that is, conversion of indigenous peoples to Christianity. When Spaniards embarked on the exploration and conquest of Mexico, a Catholic priest,

Gerónimo de Aguilar

Jerónimo de Aguilar O.F.M. (1489–1531) was a Franciscan friar born in Écija, Spain. Aguilar was sent to Panama to serve as a missionary. He was later shipwrecked on the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511 and captured by the Maya. In 1519 Hernán ...

, accompanied

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

's expedition. Spaniards were appalled at the ritual practice of human sacrifice and initially attempted to suppress it, but until the

Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, also known as the Conquest of Mexico or the Spanish-Aztec War (1519–21), was one of the primary events in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. There are multiple 16th-century narratives of the eve ...

was accomplished, it was not stamped out. The rulers of Cortés's allies from the city-state of

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is ...

converted to Christianity almost immediately and there is a depiction of Cortés,

Malinche

Marina or Malintzin ( 1500 – 1529), more popularly known as La Malinche , a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast, became known for contributing to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521), by acting as an interpreter, advi ...

, and the lords of Tlaxcala showing this event. But not until the fall of the Aztec capital of

Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

in 1521 was a full-scale conversion of the indigenous populations undertaken.

Power of the Spanish Crown in ecclesiastical matters

The justification of Spanish (and Portuguese) overseas conquests was to convert the existing populations to Christianity. The pope granted the Spanish monarch (and the crown of Portugal) broad concessions termed the ''

Patronato Real

The ''patronato'' () system in Spain (and a similar '' padroado'' system in Portugal) was the expression of royal patronage controlling major appointments of Church officials and the management of Church revenues, under terms of concordats with ...

'' or Royal Patronage, giving the monarch the power to appoint candidates for high ecclesiastical posts, collection of tithes and support of the clergy, but did not cede power in matters of doctrine or dogma. This essentially made the Spanish monarch the highest power of Church and State in its overseas territories.

The first evangelists to the indigenous

In the early conquest era of Mexico, the formal institutions of Church and State had not been established. But to initiate the spiritual conquest even though the episcopal hierarchy (the diocesan clergy) had not yet been established, Cortés requested that the

mendicant

A mendicant (from la, mendicans, "begging") is one who practices mendicancy, relying chiefly or exclusively on alms to survive. In principle, mendicant religious orders own little property, either individually or collectively, and in many inst ...

orders of

Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

s,

Dominicans, and

Augustinians

Augustinians are members of Christian religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–1 ...

be sent to New Spain, to convert the indigenous. The

Twelve Apostles of Mexico as they are known were the first Franciscans who arrived in 1524, followed by the Dominican order in 1526, and the Augustinian order in 1533.

Mendicants did not usually function as parish priests, administering the sacraments, but mendicants in early Mexico were given special dispensation to fulfill this function. The Franciscans, the first-arriving mendicants, staked out the densest and most central communities as their bases for conversion. These bases (called ''doctrina'') saw the establishment of resident friars and the building of churches, often on the same sacred ground as pagan temples.

Given the small number of mendicants and the vast number of indigenous to convert, outlying populations of indigenous communities did not have resident priests but priests visited at intervals to perform the sacraments (mainly baptism, confession, and matrimony). In prehispanic Central Mexico, there had been a long tradition of conquered city-states adding the gods of their conquerors to their existing pantheon so that conversion to Christianity seemed to be similar.

In general, Indians did not resist conversion to Christianity. Priests of the indigenous were displaced and the temples transformed into Christian churches. Mendicants targeted Indian elites as key converts, who would set the precedent for the commoners in their communities to convert. Also targeted were youngsters who had not yet grown up with pagan beliefs. In Tlaxcala, some young converts were murdered and later touted as martyrs to the faith.

In Texcoco, however, one its lords,

Don Carlos

''Don Carlos'' is a five-act grand opera composed by Giuseppe Verdi to a French-language libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, based on the dramatic play '' Don Carlos, Infant von Spanien'' (''Don Carlos, Infante of Spain'') by Fried ...

, was accused and convicted of sedition by the apostolic inquisition (which gives inquisitorial powers to a bishop) headed by

Juan de Zumárraga

Juan de Zumárraga, OFM (1468 – June 3, 1548) was a Spanish Basque Franciscan prelate and the first Bishop of Mexico. He was also the region's first inquisitor. He wrote ''Doctrina breve'', the first book published in the Western Hemisph ...

in 1536 and was executed. His execution prompted the crown to reprimand Zumárraga and when the Holy Office of the

Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

was established in Mexico in 1571, Indians were exempted from its jurisdiction. There was a concern that Indians were insufficiently indoctrinated in Catholic orthodox beliefs to be held to the same standards as Spaniards and other members of the ''República de Españoles''. In the eyes of the Church and in Spanish law, Indians were legal minors.

The arrival of the Franciscan

Twelve Apostles of Mexico initiated what came to be called The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico. Many of the names and accomplishments of earliest Franciscans have come down to the modern era, including

Toribio de Benavente Motolinia

Toribio of Benavente, O.F.M. (1482, Benavente, Spain – 1565, Mexico City, New Spain), also known as Motolinía, was a Franciscan missionary who was one of the famous Twelve Apostles of Mexico who arrived in New Spain in May 1524. His publis ...

,

Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún, OFM (; – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, ...

,

Andrés de Olmos

Andrés de Olmos (c.1485 – 8 October 1571) was a Spanish Franciscan priest and grammarian and ethno-historian of Mexico's indigenous languages and peoples. He was born in Oña, Burgos, Spain and died in Tampico in New Spain (modern-day Ta ...

,

Alonso de Molina

Alonso de Molina (1513. or 1514.. – 1579 or 1585) was a Franciscan priest and grammarian, who wrote a well-known dictionary of the Nahuatl language published in 1571 and still used by scholars working on Nahuatl texts in the tradition of the ...

, and

Gerónimo de Mendieta. The first bishop of Mexico was Franciscan

Juan de Zumárraga

Juan de Zumárraga, OFM (1468 – June 3, 1548) was a Spanish Basque Franciscan prelate and the first Bishop of Mexico. He was also the region's first inquisitor. He wrote ''Doctrina breve'', the first book published in the Western Hemisph ...

. Early Dominicans in Mexico include

Bartolomé de Las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar ...

, who famously was an

encomendero

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

and black slave dealer in the early Caribbean before he became a Dominican friar;

Diego Durán and

Alonso de Montúfar

Alonso de Montúfar y Bravo de Lagunas, O.P., was a Spanish Dominican friar and prelate of the Catholic Church, who ruled as the second Archbishop of Mexico from 1551 to his death in 1572. He approved and promoted the devotion to Our Lady of ...

who became the second bishop of Mexico. It was not until

Pedro Moya de Contreras

Pedro Moya de Contreras (sometimes ''Pedro de Moya y Contreras'') (c. 1528, Pedroche, Córdoba Province, Spain – December 21, 1591, Madrid) was a prelate and colonial administrator who held the three highest offices in the Spanish colon ...

became archbishop of Mexico in 1573 that a diocesan cleric rather than a mendicant served as Mexico's highest prelate.

The friars sought ways to make their task of converting millions of Indians less daunting. By using existing indigenous settlements in Central Mexico where indigenous rulers were kept in place in the post-conquest period, the mendicant orders created ''doctrinas'', major Indian towns designated as important for the initial evangelization, while smaller settlements, ''visitas'', were visited at intervals to teach, preach, and administer the sacraments.

Friars built churches on the sites of temples, transforming the ancient sacred space into a place for Catholic worship. Some of these have been recognized by

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

as

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

s under the general listing of

Monasteries on the slopes of Popocatépetl

The Earliest Monasteries on the Slopes of Popocatepetl ( es, Primeros Monasterios en las faldas del Popocatépetl) are fifteen 16th-century monasteries which were built by the Augustinians, the Franciscans and the Dominicans in order to evangeli ...

. Churches were built in the major Indian towns and, by the late sixteenth century, local neighborhoods; ''barrios'' (Spanish) or ''tlaxilacalli'' (Nahuatl) built chapels.

The abandoned experiment to train Indian priests

The crown and the Franciscans had hopes for the training of indigenous men to become ordained Catholic priests, and with the sponsorship of Bishop Juan de Zumárraga and Don

Antonio de Mendoza

Antonio de Mendoza y Pacheco (, ; 1495 – 21 July 1552) was a Spanish colonial administrator who was the first Viceroy of New Spain, serving from 14 November 1535 to 25 November 1550, and the third Viceroy of Peru, from 23 September 1551 ...

, the

Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco

The Colegio de Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco, Mexico City, is the first and oldest European school of higher learning in the Americas and the first major school of interpreters and translators in the New World. It was established by the Franciscans ...

was established in 1536, in an indigenous section of Mexico City. Several prominent Franciscans, including

Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún, OFM (; – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, ...

taught at the school, but the Franciscans concluded that although their elite Indian students were capable of high learning, their failure to maintain life habits expected of a friar resulted in the ending of their religious education toward ordination.

[Ricard, ''The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico'', pp. 294-95]

In 1555 the Third Mexican Provincial Council banned Indians from ordination to the priesthood. The failure to create a Christian priesthood of indigenous men has been deemed a major failure of the Catholic Church in Mexico.

With the banning of ordination for indigenous men, the priest was always a Spaniard (and in later years one who passed as one). The highest religious official in Indian towns was the ''fiscal'', who was a nobleman who aided the priest in the affairs of the church.

The Colegio continued for a number of decades more, with some of its most able students becoming participants in Sahagún's project to compile information about the prehispanic Aztecs in order that Christian evangelization would be more effective. The twelve-volume magnum opus ''The General History of the Things of New Spain'', completed in the 1570s, is one of the high achievements of the early colonial period, published in English as the

Florentine Codex

The ''Florentine Codex'' is a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Sahagún originally titled it: ''La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España'' (in English: ''Th ...

.

Mendicant-produced texts for evangelization

The Franciscans were especially prolific in creating materials so that they could evangelize in the indigenous language, which in Central Mexico was

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have small ...

, the language of the Aztecs and other groups. Fray Andrés de Olmos completed a manual designed to teach the friars Nahuatl. Fray Alonso de Molina compiled a bilingual dictionary in Nahuatl (''Mexicana'') and Spanish (''Castellano'') to aid the friars in teaching and preaching. He also created a bilingual confessional manual, so that friars could hear confessions in Nahuatl.

Bernardino de Sahagún wrote a book of psalms in Nahuatl for friars to use in their preaching; it was the only one of his many works that was published in his lifetime. When friars began to evangelize elsewhere in New Spain where there were other indigenous groups, they created similar materials in languages as diverse as Zapotec, Maya, and Chinantec. Increasingly the crown became hostile to the production of materials in indigenous languages, so that Sahagún's multivolume ''General History'' was not a model for such works elsewhere in Mexico.

One of the major challenges for friars in creating such materials was to find words and phrasing that evoked the sacred without confusing the indigenous about Christianity and their old beliefs. For that reason, a whole series of words from Spanish and a few from Latin were incorporated as loanwords into Nahuatl to denote God (''Dios'') rather than god (''teotl'') and others to denote new concepts, such as a last will and testament (''testamento'') and soul (''ánima''). Some Christian dichotomous concepts, such as good and evil, were not easy to convey to Nahuas, since their belief system sought a middle ground without extremes.

Fray Alonso de Molina's 1569 confessional manual had a model testament in Spanish and Nahuatl. Whether or not it was the direct model for Nahua scribes or notaries in indigenous towns, the making of testaments that were simultaneously a religious document as well as one designed to pass property to selected heirs became standard in Nahua towns during the second half of the sixteenth century and carried on as a documentary type until Mexican independence in 1821. Early testaments in Nahuatl have been invaluable for the information they provide about Nahua men and women's property holding, but the religious formulas at the beginning of wills were largely that and did not represent individual statements of belief. However, testators did order property to be sold for Masses for their souls or gave money directly to the local friar, which may well have been encouraged by the recipients but can also be the testators’ gesture of piety.

Hospitals

The friars founded 120 hospitals in the first hundred years of the colonial era, some serving only Spaniards but others exclusively for the indigenous. These hospitals for Indians were especially important since epidemics sickened and killed countless Indians after the conquest.

[David Howard, ''The Royal Indian Hospital of Mexico City'', Tempe: Arizona State University Center for Latin American Studies, Special Studies 20, 1979, p. 1.] Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

endowed the Hospital of the Immaculate Conception, more commonly known as the Hospital de Jesús, in Mexico City, which was run by religious. Bishop

Vasco de Quiroga

Vasco de Quiroga (1470/78 – 14 March 1565) was the first bishop of Michoacán, Mexico, and one of the judges (''oidores'') in the second Real Audiencia of Mexico – the high court that governed New Spain – from January 10, 1531, to April 16, ...

founded hospitals in Michoacan. The crown established the Royal Indian Hospital (''Hospital Real de Indios'' or ''Hospital Real de Naturales'') in Mexico city in 1553, which functioned until 1822 when Mexico gained its independence.

Although the Royal Indian Hospital was a crown institution and not an ecclesiastical one, the nursing staff during the eighteenth century was the brothers of the religious order of San Hipólito. The order was founded in Mexico by Bernardino de Alvarez (1514–1584), and it established a number of hospitals. The religious order was to be removed from its role at the Royal Indian Hospital by a royal decree (''cédula'') after an investigation into allegations of irregularities, and the brothers were to return to their convent.

Hospitals were not just places to treat the sick and dying, but were spiritual institutions as well. At the Royal Indian Hospital, the ordinances for governing called for four chaplains, appointed by the crown and not the church, to minister to the sick and dying. All four had to be proficient in either Nahuatl or Otomi, with two to serve in each language.

[Howard, ''Royal Indian Hospital'', p. 34.] Although many secular clerics without a benefice held multiple posts in order to make a living, the chaplains at the Royal Indian Hospital were forbidden to serve elsewhere.

Confraternities

Organizations that were more in the hands of the indigenous were

confraternities

A confraternity ( es, cofradía; pt, confraria) is generally a Christian voluntary association of laypeople created for the purpose of promoting special works of Christian charity or piety, and approved by the Church hierarchy. They are most ...

(''cofradías'') founded in the Nahua area starting in the late sixteenth century and were established elsewhere in indigenous communities. Confraternities functioned as burial societies for their members, celebrated their patron saint, and conducted other religious activities, nominally under the supervision of a priest, but like their European counterparts there was considerable power in the hands of the lay leadership. Confraternities usually had religious banners, many of their officials wore special ritual attire, and they participated in larger religious festivities as an identifiable group. For Indians and Blacks, these religious organizations promoted both their spiritual life and their sense of community, since their membership was exclusively of those groups and excluded Spaniards. On the contrary, ''limpieza'' (pure Spanish blood) status was gradually necessary for certain religious orders, confraternities, convents, and guilds.

In one Nahua sodality in Tula, women not only participated but held publicly religious office. When the confraternity was given official recognition in 1631, they are noted in the confraternity's records in Nahuatl: "Four mothers of people in holy matters

ho are

Ho (or the transliterations He or Heo) may refer to:

People Language and ethnicity

* Ho people, an ethnic group of India

** Ho language, a tribal language in India

* Hani people, or Ho people, an ethnic group in China, Laos and Vietnam

* Hiri ...

to take good care of the holy ''cofradía'' so it will be much respected, and they are to urge those who have not yet joined the ''cofradía'' to enter, and they are to take care of the brothers

nd sisterswho are sick, and the orphans; they are to see to what is needed for their souls and what pertains to their earthly bodies."

In the Maya area, confraternities had considerable economic power since they held land in the name of their patron saint and the crops went to the support of the saint's cult. The ''cah's'' (indigenous community) retention of considerable land via the confraternities was a way the Maya communities avoided colonial officials, the clergy, or even indigenous rulers (''gobernadores'') from diverting of community revenues in their ''cajas de comunidad'' (literally community-owned chests that had locks and keys). "

Yucatan the ''cofradía'' in its modified form ''was'' the community."

Spanish Habsburg Era (1550–1700)

Establishment of the episcopal hierarchy and the assertion of crown control

The Catholic Church is organized by territorial districts or dioceses, each with a

bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

. The main church of a diocese is the

cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

. The diocese of Mexico was established in Mexico City in 1530. Initially, Mexico was not an episcopal jurisdiction in its own right; until 1547 it was under the authority of the Archbishop of

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

(Spain).

The first bishop of Mexico was Franciscan friar Don

Juan de Zumárraga

Juan de Zumárraga, OFM (1468 – June 3, 1548) was a Spanish Basque Franciscan prelate and the first Bishop of Mexico. He was also the region's first inquisitor. He wrote ''Doctrina breve'', the first book published in the Western Hemisph ...

. The church that became the first cathedral was begun in 1524 on the main square

Zócalo

The Zócalo () is the common name of the main square in central Mexico City. Prior to the colonial period, it was the main ceremonial center in the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan. The plaza used to be known simply as the "Main Square" or "Arms Sq ...

and consecrated in 1532. In general, a member of a mendicant order was not appointed to a high position in the episcopal hierarchy, so Zumárraga and his successor Dominican

Alonso de Montúfar

Alonso de Montúfar y Bravo de Lagunas, O.P., was a Spanish Dominican friar and prelate of the Catholic Church, who ruled as the second Archbishop of Mexico from 1551 to his death in 1572. He approved and promoted the devotion to Our Lady of ...

(r. 1551–1572) as bishops of Mexico should be seen as atypical figures. In 1572

Pedro Moya de Contreras

Pedro Moya de Contreras (sometimes ''Pedro de Moya y Contreras'') (c. 1528, Pedroche, Córdoba Province, Spain – December 21, 1591, Madrid) was a prelate and colonial administrator who held the three highest offices in the Spanish colon ...

became the first bishop of Mexico who was a secular cleric.

Bishops as interim viceroys

The crown established the

viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

, appointing high-born Spaniards loyal to the crown as the top civil official. On occasion in all three centuries of Spanish rule, the crown appointed archbishops or bishops as

viceroy of New Spain

The following is a list of Viceroys of New Spain.

In addition to viceroys, the following lists the highest Spanish governors of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, before the appointment of the first viceroy or when the office of viceroy was vacant. ...

, usually on an interim basis, until a new viceroy was sent from Spain.

Pedro Moya de Contreras

Pedro Moya de Contreras (sometimes ''Pedro de Moya y Contreras'') (c. 1528, Pedroche, Córdoba Province, Spain – December 21, 1591, Madrid) was a prelate and colonial administrator who held the three highest offices in the Spanish colon ...

was the first secular cleric to be appointed archbishop of Mexico and he was also the first cleric to serve as viceroy, September 25, 1584 – October 17, 1585.

The seventeenth century saw the largest number of clerics as viceroys. The Dominican

García Guerra

Fray García Guerra (''also Francisco García Guerra''), OP (c. 1547 in Frómista, Palencia, Spain – February 22, 1612 in Mexico City), archbishop of Mexico and viceroy of New Spain. He held the former office from December 3, 1607, and the l ...

served from June 19, 1611 – February 22, 1612. Blessed Don

Juan de Palafox y Mendoza

Juan de Palafox y Mendoza (26 June 1600 – 1 October 1659) was a Spanish politician, administrator, and Catholic clergyman in 17th century Spain and a viceroy of Mexico.

Palafox was the Bishop of Puebla (1640−1655), and the interim Archbis ...

also served briefly as viceroy, June 10, 1642 – November 23, 1642.

Marcos de Torres y Rueda

Marcos de Torres y Rueda (April 25, 1591, Almazán, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyo ...

, bishop of Yucatán, served from May 15, 1648 – April 22, 1649.

Diego Osorio de Escobar y Llamas, bishop of Puebla, served from June 29, 1664 – October 15, 1664. Archbishop of the

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mexico

The Archdiocese of Mexico ( la, Archidioecesis Mexicanensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church that is situated in Mexico City, Mexico. It was erected as a diocese on 2 September 1530 and elevated to ...

Payo Enríquez de Rivera Manrique,

O.S.A., served an unusually long term as viceroy, from December 13, 1673, to November 7, 1680. Another unusual cleric-viceroy was

Juan Ortega y Montañés

Don Juan Ortega y Montañés (''also Juan de Ortega Cano Montañez y Patiño'') (July 3, 1627 in Siles, Spain – December 16, 1708 in Mexico City) was a Roman Catholic bishop and colonial administrator in Guatemala and New Spain. He was s ...

, archbishop of Mexico City archdiocese, who served twice as interim viceroy, February 27, 1696, to December 18, 1696, and again from November 4, 1701, to November 27, 1702.

Once the Spanish Bourbon monarchy was established, just three clerics served as viceroy. Archbishop of Mexico City

Juan Antonio de Vizarrón y Eguiarreta

Juan Antonio de Vizarrón y Eguiarreta (September 2, 1682, in El Puerto de Santa María, Spain – January 25, 1747, in Mexico City, Spain) was archbishop of Mexico from March 21, 1731, to January 25, 1747, and viceroy of New Spain from March ...

, served six years as viceroy, March 17, 1734, to August 17, 1740. The last two cleric-viceroys followed the more usual pattern of being interim.

Alonso Núñez de Haro y Peralta

Dr. Alonso Núñez de Haro y Peralta (October 31, 1729 – May 26, 1800) was archbishop of Mexico from September 12, 1772, to May 26, 1800, and viceroy of New Spain from May 8, 1787, to August 16, 1787.

Origins and education

Núñez de Ha ...

, archbishop of Mexico City, served from May 8, 1787, to August 16, 1787, and

Francisco Javier de Lizana y Beaumont, archbishop of Mexico City, served from July 19, 1809, to May 8, 1810.

Structure of the episcopal hierarchy

The ecclesiastical structure was ruled by a bishop, who had considerable power encompassing legislative, executive, and judicial matters. A bishop ruled over a geographical district, a diocese, subdivided into parishes, each with a parish priest. The seat of the diocese was its cathedral, which had its own administration, the ''cabildo eclesiástico'' whose senior official was the dean of the cathedral.

New Spain became the seat of an archbishopric in 1530, with the archbishop overseeing multiple dioceses. The diocese of Michoacan (now Morelía) became an archdiocese in the sixteenth century as well. The creation of further dioceses in Mexico is marked by the construction of cathedrals in the main cities: the cathedral in Antequera (now Oaxaca City) (1535), the

Guadalajara Cathedral (1541), the

Puebla Cathedral

The Basilica Cathedral of Puebla, as the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception is known according to its Marian invocation, is the episcopal see of the Archdiocese of Puebla de los Ángeles (Mexico). It is one of the most importan ...

1557, the

Zacatecas Cathedral

The Cathedral of Zacatecas, dedicated to the Assumption of Mary, Virgin of the Assumption, is the main temple of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Zacatecas, Diocese of Zacatecas. Located in the historic center of the Zacatecas City, city, declared W ...

(1568), the

Mérida Cathedral

Mérida or Merida may refer to:

Places

*Mérida (state), one of the 23 states which make up Venezuela

* Mérida, Mérida, the capital city of the state of Mérida, Venezuela

*Merida, Leyte, Philippines, a municipality in the province of Leyte

*M ...

(1598), and the Saltillo Cathedral (1762).

Ecclesiastical privileges

The ordained clergy (but not religious sisters) had ecclesiastical privileges (''fueros''), which meant that they were exempt from civil courts, no matter what the offense, but were tried in canonical courts. This separation of jurisdictions for different groups meant that the Church had considerable independent power. In the late eighteenth century, one of the

Bourbon Reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of the new Crown's ...

was the removal of this ''fuero'', making the clergy subject to civil courts.

[N.M. Farriss, ''Crown and Clergy in Colonial Mexico''. London: Athlone Press 1968.]

Secular or diocesan clergy's income

Members of the upper levels of the hierarchy, parish priests, and priests who functioned in religious institutions such as hospitals, received a salaried income, a benefice. However, not all ordained priests had a secure income from such benefices and had to find a way to make a living. Since secular priests did not take a vow of poverty, they often pursued economic functions like any other member of Hispanic society. An example of a secular cleric piecing together an income from multiple posts is Don

Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora

Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (August 14, 1645 – August 22, 1700) was one of the first great intellectuals born in the New World - Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain ( Mexico City). He was a criollo patriot, exalting New Spain over O ...

, one of New Spain's most distinguished intellectuals, who had no benefice.

Reduction of mendicants' role

In the sixteenth century, the establishment of the episcopal hierarchy was part of a larger Crown policy that in the early period increasingly aimed at diminishing the role of the mendicant orders as parish priests in central areas of the colony and strengthening the role of the diocesan (secular) clergy. The ''Ordenanza del Patronazgo'' was the key act of the crown asserting control over the clergy, both mendicant and secular. It was promulgated by the crown in 1574, codifying this policy, which simultaneously strengthened the crown's role, since it had the power of royal patronage over the diocesan clergy, the ''

Patronato Real

The ''patronato'' () system in Spain (and a similar '' padroado'' system in Portugal) was the expression of royal patronage controlling major appointments of Church officials and the management of Church revenues, under terms of concordats with ...

'', but not the mendicant orders.

The ''Ordenanza'' guaranteed parish priests an income and a permanent position. Priests competed for desirable parishes through a system of competitive examinations called ''oposiones'', with the aim of having the most qualified candidates receiving benefices. With these competitions, the winners became holders of benefices (''beneficiados'') and priests who did not come out on top were curates who served on an interim basis by appointment by the bishop; those who failed entirely did not even hold a temporary assignment. The importance of the ''Ordenanza'' is in the ascendancy of the diocesan clergy over the mendicants, but also indicates the growth in the Spanish population in New Spain and the necessity not only to minister to it but also to provide ecclesiastical posts for the best American-born Spaniards (creoles).

Pious endowments

One type of institution that produced income for priests without a parish or other benefice was to say Masses for the souls of men and women who had set up chantries (''capellanías''). Wealthy members of society would set aside funds, often by a lien on real property, to ensure Masses would be said for their souls in perpetuity. Families with an ordained priest as a member often designated him as the ''capellán'', thus ensuring the economic well-being of one of its own. Although the endowment was for a religious purpose, the Church itself did not control the funds. It was a way that pious elite families could direct their wealth.

Tithes

The crown had significant power in the economic realm regarding the Church, since it was granted the use of tithes (a ten percent tax of agriculture) and the responsibility of collecting them. In general the crown gave these revenues for the support of the Church, and where revenues fell short, the crown supplemented them from the royal treasury.

Society of Jesus in Mexico, 1572–1767

At the same time that the episcopal hierarchy was established, the

Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

or Jesuits, a new religious order founded on new principles, came to Mexico in 1572. The Jesuits distinguished themselves in several ways. They had high standards for acceptance to the order and many years of training. They were adept at attracting the patronage of elite families whose sons they educated in rigorous, newly founded Jesuit ''colegios'' ("colleges"), including

Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo,

Colegio de San Ildefonso

The Colegio de San Ildefonso was an educational institution run by the Society of Jesus in Cebu City, Philippines in the then Spanish Captaincy General of the Philippines. It was established by the Jesuits in 1595 thus making it the first Europe ...

, and the

Colegio de San Francisco Javier, Tepozotlan. Those same elite families hoped that a son with a vocation to the priesthood would be accepted as a Jesuit. Jesuits were also zealous in evangelization of the indigenous, particularly on the northern frontiers.

Jesuit haciendas

To support their colleges and members of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits acquired landed estates that were run with the best-practices for generating income in that era. A number of these haciendas were donated by wealthy elites. The donation of an hacienda to the Jesuits was the spark igniting a conflict between seventeenth-century bishop of Puebla

Don Juan de Palafox and the Jesuit ''colegio'' in that city. Since the Jesuits resisted paying the tithe on their estates, this donation effectively took revenue out of the church hierarchy's pockets by removing it from the tithe rolls.

[D.A. Brading, ''The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991, 242.]

Many Jesuit haciendas were huge, with Palafox asserting that just two colleges owned 300,000 head of sheep, whose wool was transformed locally in Puebla to cloth; six sugar plantations worth a million pesos and generating an income of 100,000 pesos.

The immense Jesuit hacienda of Santa Lucía produced ''pulque'', the fermented juice of the agave cactus whose main consumers were the lower classes and Indians in Spanish cities. Although most haciendas had a free work force of permanent or seasonal laborers, the Jesuit haciendas in Mexico had a significant number of black slaves.

The Jesuits operated their properties as an integrated unit with the larger Jesuit order; thus revenues from haciendas funded ''colegios''. Jesuits did significantly expand missions to the indigenous in the frontier area and a number were martyred, but the crown supported those missions.

Mendicant orders that had real estate were less economically integrated, so that some individual houses were wealthy while others struggled economically. The Franciscans, who were founded as an order embracing poverty, did not accumulate real estate, unlike the Augustinians and Dominicans in Mexico.

Jesuit resistance to the tithe

The Jesuits engaged in conflict with the episcopal hierarchy over the question of payment of tithes, the ten percent tax on agriculture levied on landed estates for support of the Church hierarchy, from bishops and cathedral chapters to parish priests. Since the Jesuits were the largest religious order holding real estate, surpassing the Dominicans and Augustinians who had accumulated significant property, this was no small matter.

They argued that they were exempt, due to special pontifical privileges. In the mid-seventeenth century, bishop of Puebla Don

Juan de Palafox

Juan de Palafox y Mendoza (26 June 1600 – 1 October 1659) was a Spanish politician, administrator, and Catholic clergyman in 17th century Spain and a viceroy of Mexico.

Palafox was the Bishop of Puebla (1640−1655), and the interim Archbis ...

took on the Jesuits over this matter and was so soundly defeated that he was recalled to Spain, where he became the bishop of the minor diocese of

Osma

Burgo de Osma-Ciudad de Osma is the third-largest municipality in the province of Soria, in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It has a population of about 5,250.

It is made up of two parts:

*the smaller Ciudad de Osma (c ...

. The mendicant orders were envious of the Jesuits’ economic power and influence and the fact that fewer good candidates for their orders chose them as opposed to the Jesuits.

Expulsion of the Jesuits 1767

In 1767, the Spanish crown ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain and its overseas territories. Their properties passed into the hands of elites who had the wherewithal to buy them. The mendicants did not protest their expulsion. The Jesuits had established missions in

Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

prior to their expulsion. These were taken over by the Franciscans, who then went on to establish 21 missions in

Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

.

Convents

Establishments for elite creole women

In the first generation of Spaniards in New Spain, women emigrated to join existing kin, generally marrying. With few marital partners of equal ''calidad'' for Spanish men, there was pressure for Spanish women to marry rather than take the veil as a cloistered

nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

. However, as more Spanish families were created and there were a larger number of daughters, the social economy could accommodate the creation of nunneries for women. The first convent in New Spain was founded in 1540 in Mexico City by the Conceptionist Order. Mexico City had the largest number of nunneries with 22. Puebla, New Spain's second largest city, had 11, with its first in 1568; Guadalajara had 6, starting in 1578; Antequera (Oaxaca), had 5, starting in 1576. In all, there were 56 convents for creole women in New Spain, with the greatest number in the largest cities. However, even a few relatively small provincial cities had convents, including Pátzcuaro (1744), San Miguel el Grande (1754), Aguascalientes (1705-07), Mérida (Yucatán) 1596, and San Cristóbal (Chiapas) 1595. The last nunnery before independence in 1821 was in Mexico City in 1811, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Over the colonial period, there were 56 nunneries established in New Spain, the largest number being the

Conceptionists

, image = OrdoIC.jpg

, size = 150px

, abbreviation = OIC

, nickname = Conceptionists

, motto =

, formation =

, founder = Saint Beatrice of Silva)

, founding_locatio ...

with 15, followed by Franciscans at 14, Dominicans with 9, and

Carmelites

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount C ...

with 7. Sor Juana's Jeronymite order had only 3 houses. The largest concentration of convents was in the capital, Mexico City, with 11 built between 1540 and 1630, and, by 1780 another 10 for a total of 21.

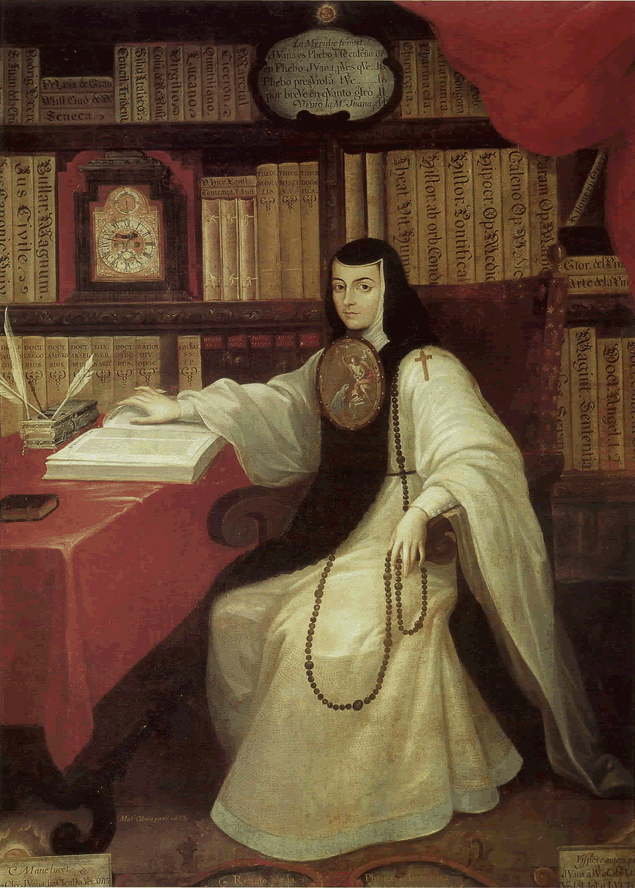

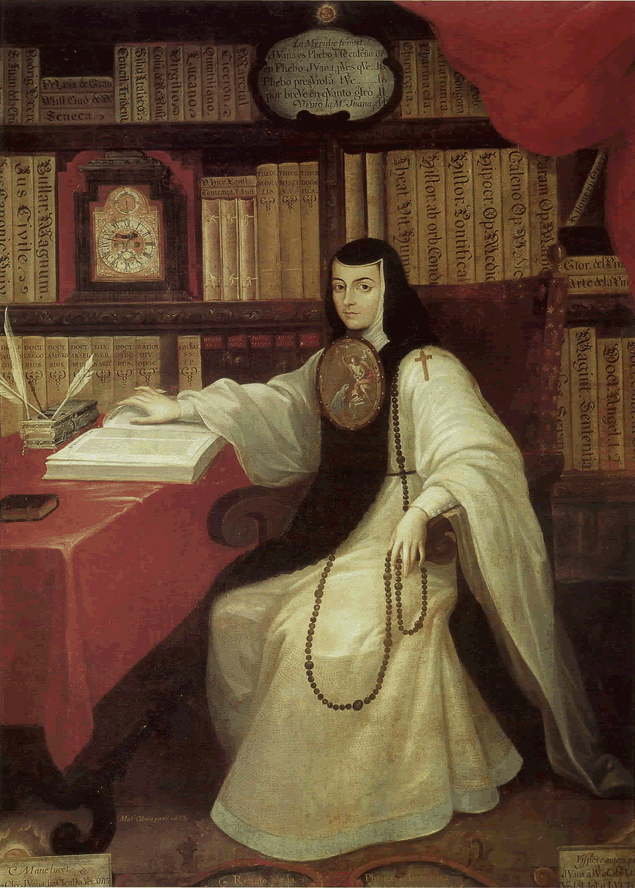

These institutions were designed for the daughters of elites, with individual living quarters not only for the nuns, but also their servants. Depending on the particular religious order, the discipline was more or less strict. The Carmelites were strictly observant, which prompted Doña Juana Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana to withdraw from their community and join the Jeronymite nunnery in Mexico City, becoming Sor

Juana Inés de la Cruz

''Doña'' Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, better known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (12 November 1648 – 17 April 1695) was a Mexican writer, philosopher, composer and poet of the Baroque period, and Hieronymite nun. Her contribut ...

, known in her lifetime as the "Tenth Muse".

Nuns were enclosed in their convents, but some orders regularly permitted visits from the nuns’ family members (and in Sor Juana's case, the viceroy and his wife the virreina), as well as her friend, the priest and savant Don

Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora

Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (August 14, 1645 – August 22, 1700) was one of the first great intellectuals born in the New World - Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain ( Mexico City). He was a criollo patriot, exalting New Spain over O ...

. Nuns were required to provide a significant dowry to the nunnery on their entrance. As "brides of Christ", nuns often entered the nunnery with an elaborate ceremony that was an occasion for the family to display not only its piety but also its wealth.

Nunneries accumulated wealth due to the dowries donated for the care of nuns when they entered. Many nunneries also acquired urban real estate, whose rents were a steady source of income to that particular house.

For Indian noblewomen

In the eighteenth century, the Poor Clares established a convent for noble Indian women. The debate leading up to the creation of the convent of Corpus Christi in 1724 was another round of debate about the capacity of Indians, male or female, for religious life. The early sixteenth century had seen the demise of the

Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco

The Colegio de Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco, Mexico City, is the first and oldest European school of higher learning in the Americas and the first major school of interpreters and translators in the New World. It was established by the Franciscans ...

, which had been founded to train Indian men for ordination.

Holy Office of the Inquisition

At the same time that the episcopal hierarchy in Mexico first had a secular cleric as archbishop, the tribunal of the

Holy Office of the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

was established in 1569 to maintain orthodoxy and Christian morality. In 1570, Indians were removed from the Inquisition's jurisdiction.

Crypto-Jews

Non-Catholics were banned from emigrating to Spain's overseas territories, with potential migrants needing to receive a license to travel that stated they were of pure Catholic heritage. However, a number of

crypto-Jews, that is, Jews who supposedly converted to Christianity (''conversos'') but continued practicing Judaism, did emigrate. Many were merchants of Portuguese background, who could more easily move within the Spanish realms during the period 1580–1640 when Spain and Portugal had the same monarch.

The Portuguese empire included territories in West Africa and was the source of African slaves sold in Spanish territories. Quite a number of Portuguese merchants in Mexico were involved in the transatlantic slave trade. When Portugal successfully revolted against Spanish rule in 1640, the Inquisition in Mexico began to closely scrutinize the merchant community in which many Portuguese merchants were crypto-Jews. In 1649, crypto-Jews both living and dead were "relaxed to the secular arm" of crown justice for punishment. The Inquisition had no power to execute the convicted, so civil justice carried out capital punishment in a grand public ceremony affirming the power of Christianity and the State.

The Gran Auto de Fe of 1649 saw Crypto-Jews burned alive, while the effigies or statues along with the bones of others were burned. Although the trial and punishment of those already dead might seem bizarre to those in the modern era, the disinterment of the remains of crypto-Jews from Christian sacred ground and then burning their remains protected living and dead Christians from the pollution of those who rejected Christ. A spectacular case of sedition was prosecuted a decade later in 1659, the case of Irishman

William Lamport

William Lamport (or Lampart) (1611/1615 – 1659) was an Irish Catholic adventurer, known in Mexico as "Don Guillén de Lamport (or Lombardo) y Guzmán". He was tried by the Mexican Inquisition for sedition and executed in 1659. He claimed to b ...

, also known as Don Guillén de Lampart y Guzmán, who was executed in an ''

auto de fe

Auto may refer to:

* An automaton

* An automobile

* An autonomous car

* An automatic transmission

* An auto rickshaw

* Short for automatic

* Auto (art), a form of Portuguese dramatic play

* ''Auto'' (film), 2007 Tamil comedy film

* Auto (play), ...

''.

Other jurisdictional transgressions

In general though the Inquisition imposed penalties that were far less stringent than capital punishment. They prosecuted cases of bigamy, blasphemy, Lutheranism (Protestantism), witchcraft, and, in the eighteenth century, sedition against the crown was added to the Inquisition's jurisdiction. Historians have in recent decades utilized Inquisition records to find information on a broad range of those in the Hispanic sector and discern social and cultural patterns and colonial ideas of deviance.

Indigenous beliefs

Indigenous men and women were excluded from the jurisdiction of the Inquisition when it was established, but there were on-going concerns about indigenous beliefs and practice. In 1629, Hernando Riz de Alarcón wrote the ''Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions that today live among the Indians native to this New Spain. 1629.'' Little is known about Ruiz de Alarcón himself, but his work is an important contribution to early Mexico for understanding Nahua religion, beliefs, and medicine. He collected information about Nahuas in what is now modern Guerrero. He came to the attention of the Inquisition for conducting ''autos-de-fe'' and punishing Indians without authority. The Holy Office exonerated him due to his ignorance and then appointed him to a position to inform the Holy Office of pagan practices, resulting in the ''Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions''.

Devotions to holy men and women

Virgin of Guadalupe and other devotions to Mary

In 1531, a Nahua,

Juan Diego

Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, also known as Juan Diego (; 1474–1548), was a Chichimec peasant and Marian visionary. He is said to have been granted apparitions of the Virgin Mary on four occasions in December 1531: three at the hill of Tepeyac an ...

, is said to have experienced a vision of a young girl on the site of a destroyed temple to a

mother goddess

A mother goddess is a goddess who represents a personified deification of motherhood, fertility goddess, fertility, creation, destruction, or the earth goddess who embodies the bounty of the earth or nature. When equated with the earth or t ...

. The cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe was promoted by Dominican archbishop of Mexico,

Alonso de Montúfar

Alonso de Montúfar y Bravo de Lagunas, O.P., was a Spanish Dominican friar and prelate of the Catholic Church, who ruled as the second Archbishop of Mexico from 1551 to his death in 1572. He approved and promoted the devotion to Our Lady of ...

, while Franciscans such as

Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún, OFM (; – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, ...

were deeply suspicious because of the possibility of confusion and idolatry.

The vision became embodied in a physical object, the cloak or ''tilma'' on which the image of the Virgin appeared. This ultimately became known as

Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe grew in importance in the seventeenth century, becoming especially associated with American-born Spaniards. In the era of independence, she was an important symbol of liberation for the insurgents.

Although the Virgin of Guadalupe is the most important Marian devotion in Mexico, she is by no means the only one. In

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is ...

, the

Virgin of Ocotlan is important; in Jalisco

Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos and the

Basilica of Our Lady of Zapopan

The Basilica of Our Lady of Zapopan ( es, Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Zapopan) and the abbey of Our lady of zapopan of Zapopan are a 17th-century Franciscan sanctuary built in downtown Zapopan, in the state of Jalisco, México.

It is one of ...

are important pilgrimage sites; in Oaxaca, the

Basilica of Our Lady of Solitude is important. In the colonial period and particularly during the struggle for independence in the early nineteenth century, the

Virgin of Los Remedios

The Virgin of Los Remedios ( es, La Virgen de los Remedios) or Our Lady of Los Remedios ( pt, Nossa Senhora dos Remédios, es, Nuestra Señora de los Remedios) is a title of the Virgin Mary developed by the Trinitarian Order, founded in the lat ...

was the symbolic leader of the royalists defending Spanish rule in New Spain.

Devotions to Christ and pilgrimage sites

In colonial New Spain, there were several devotions to Christ with images of Christ focusing worship. A number of them were images are of a Black Christ. The

Cristos Negros of Central America and Mexico included the Cristo Negro de Esquipulas; the Cristo Negro of Otatitlan, Veracruz; the Cristo Negro of San Pablo Anciano, Acatitlán de Osorio, Puebla; the Lord of Chalma, in

Chalma, Malinalco. In

Totolapan

Totolapan is a municipality in the north of the Mexican state of Morelos, surrounded by the State of Mexico to the north; to the south with Tlayacapan and Atlatlahucan; to the east and southeast with Atlatlahucan; and to the west with Tlalnepan ...

, Morelos, the Christ crucified image that appeared in 1543 has been the subject of a full-scale scholarly monograph.

Mexican saints

New Spain had residents who lived holy lives and were recognized in their own communities. Late sixteenth-century Franciscan

Felipe de Jesús, who was born in Mexico, became its first saint, a martyr in Japan; he was beatified in 1627, a step in the process of sainthood, and canonized a saint in 1862, during a period of conflict between Church and the liberal State in Mexico. One of the martyrs of the Japanese state's crackdown on Christians, San Felipe was crucified.

Sebastian de Aparicio

Sebastian may refer to:

People

* Sebastian (name), including a list of persons with the name

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films and television

* ''Sebastian'' (1968 film), British spy film

* ''Sebastian'' (1995 film), Swedish drama film

...

, another sixteenth-century holy person, was a lay Franciscan, an immigrant from Spain, who became a Franciscan late in life. He built a reputation for holiness in Puebla, colonial Mexico's second largest city, and was beatified (named Blessed) in 1789. Puebla was also the home of another immigrant, Catarina de San Juan, one who did not come to New Spain of her own volition, but as an Asian (''China'') slave.

[Ronald J. Morgan, ''Spanish American Saints'' pp. 119-142.]

Known as the "''

China Poblana''" (Asian woman of Puebla), Catarina lived an exemplary life and was regarded in her lifetime as a holy woman, but the campaign for her recognition by the Vatican stalled in the seventeenth century, despite clerics’ writing her spiritual autobiography. Her status as an outsider and non-white might have affected her cause for designation as holy.

Madre

María de Ágreda

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

*170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

*Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, da ...

(1602–1665), named Venerable in 1675, was a Spanish nun who, while cloistered in Spain, is said to have experienced

bilocation

Bilocation, or sometimes multilocation, is an alleged psychic or miraculous ability wherein an individual or object is located (or appears to be located) in two distinct places at the same time. Reports of bilocational phenomena have been made i ...

between 1620 and 1623 and is believed to have helped evangelize the

Jumano Jumanos were a tribe or several tribes, who inhabited a large area of western Texas, New Mexico, and northern Mexico, especially near the Junta de los Rios region with its large settled Indigenous population. They lived in the Big Bend area in ...

Indians of west Texas and New Mexico.

In the twentieth century, the Vatican beatified in 1988 eighteenth-century Franciscan

Junípero Serra

Junípero Serra y Ferrer (; ; ca, Juníper Serra i Ferrer; November 24, 1713August 28, 1784) was a Spanish Roman Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Order. He is credited with establishing the Franciscan Missions in the Sierr ...

(1713–84) and canonized him in 2015. He founded most of the Franciscan

Missions of California. Seventeenth-century bishop of Puebla and Osma (Spain), Don

Juan de Palafox y Mendoza

Juan de Palafox y Mendoza (26 June 1600 – 1 October 1659) was a Spanish politician, administrator, and Catholic clergyman in 17th century Spain and a viceroy of Mexico.

Palafox was the Bishop of Puebla (1640−1655), and the interim Archbis ...

was beatified in 2011 by

Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereig ...

. The Niños Mártires de Tlaxcala (child martyrs of Tlaxcala), who died during the initial "spiritual conquest" of the 1520s, were the first lay Catholics from the Americas beatified, done in 1990 by John Paul II.

Juan Diego

Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, also known as Juan Diego (; 1474–1548), was a Chichimec peasant and Marian visionary. He is said to have been granted apparitions of the Virgin Mary on four occasions in December 1531: three at the hill of Tepeyac an ...

, the Nahua who is credited with the vision of

Our Lady of Guadalupe was beatified in 1990 and canonized in 2002 by John Paul II in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The Church has also canonized a number of twentieth-century

Saints of the Cristero War; Father

Miguel Pro

José Ramón Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez, also known as Blessed Miguel Pro, SJ (January 13, 1891 – November 23, 1927) was a Mexican Jesuit priest executed under the presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles on the false charges of bombing and atte ...

was beatified in 1988 by

John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

.

Spanish Bourbon Era 1700–1821

With the death of Charles II of Spain in 1700 without heir, the crown of Spain was contested by European powers in the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. The candidate from the French

House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spani ...

royal line became Philip V of Spain, coming to power in 1714. Initially, in terms of ecclesiastical matters there were no major changes, but the Bourbon monarchs in both France and Spain began making major changes to existing political, ecclesiastical, and economic arrangements, collectively known as the

Bourbon Reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of the new Crown's ...

. Church-state Bourbon policy shifted toward an increase in state power and a decrease in ecclesiastical.

The

''Patronato Rea''l ceding the crown power in the ecclesiastical sphere continued in force, but the centralizing tendencies of the Bourbon state meant that policies were implemented that directly affected clerics. Most prominent of these was the attack on the special privileges of the clergy, the ''fuero eclesiástico'' which exempted churchmen from prosecution in civil courts.

Bourbon policy also began to systematically exclude American-born Spaniards from high ecclesiastical and civil office while privileging

peninsular

A peninsula (; ) is a landform that extends from a mainland and is surrounded by water on most, but not all of its borders. A peninsula is also sometimes defined as a piece of land bordered by water on three of its sides. Peninsulas exist on all ...

Spaniards. The Bourbon crown diminished the power and influence of parish priests,

secularized missions founded by the mendicant orders (meaning that the secular or diocesan clergy rather than the orders were in charge). An even more sweeping change was the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain and Spain's overseas territories in 1767. The crown expanded the jurisdiction of the Inquisition to include sedition against the crown.

The crown also expanded its reach into ecclesiastical matters by bringing in new laws that empowered families to veto the marriage choices of their offspring. This disproportionately affected elite families, giving them the ability to prevent marriages to those they deemed social or racial unequals. Previously, the regulation of marriage was in the hands of the Church, which consistently supported a couple's decision to marry even when the family objected. With generations of racial mixing in Mexico in a process termed ''mestizaje'', elite families had anxiety about interlopers who were of inferior racial status.

Changes in the Church as an economic institution

In the economic sphere, the Church had acquired a significant amount of property, particularly in Central Mexico, and the Jesuits ran efficient and profitable

hacienda

An ''hacienda'' ( or ; or ) is an estate (or '' finca''), similar to a Roman '' latifundium'', in Spain and the former Spanish Empire. With origins in Andalusia, ''haciendas'' were variously plantations (perhaps including animals or orchard ...

s, such as that of Santa Lucía. More important, however, was the Church's taking the role of the major lender for mortgages. Until the nineteenth century in Mexico, there were no banks in the modern sense, so that those needing credit to finance real estate acquisitions turned to the Church as a banker.

The Church had accumulated wealth from donations by patrons. That capital was too significant to let sit idle, so it was lent to reputable borrowers, generally at 5 percent interest. Thus, elite land owners had access to credit to finance acquisitions of property and infrastructure improvement, with multi-decade mortgages. Many elite families’ consumption patterns were such that they made little progress on paying off the principal and many estates were very heavily mortgaged to the Church. Estates were also burdened with liens on their income to pay for the salary of the family's ''capellan'', a priest guaranteed an income to say Masses for the founder of the ''capellanía''.

The Bourbon crown attempted to eliminate ''capellanías'' entirely. The lower secular clergy was significantly affected, many of whom not having a steady income via a benefice, or having a benefice insufficient to support them.

The Bourbon monarchy increasingly tried to gain control over ecclesiastical funds for their own purposes. They eliminated tax exemptions for ecclesiastical donations, put a 15% tax on property passing into the hands of the Church in ''

mortmain

Mortmain () is the perpetual, inalienable ownership of real estate by a corporation or legal institution; the term is usually used in the context of its prohibition. Historically, the land owner usually would be the religious office of a church ...

''. Most serious for elite creole families was the crown's law, the Act of Consolidation in 1804, which changed the terms of mortgages. Rather than long-term mortgages with a modest schedule of repayment, the crown sought to gain access to that capital immediately. Thus, families were suddenly faced with paying off the entire mortgage without the wherewithal to gain access to other credit. It was economically ruinous to many elite families and is considered a factor in elite creoles’ alienation from the Spanish crown.

Expulsion of the Jesuits 1767

The Jesuits were an international order with an independence of action due to its special relationship as "soldiers of the pope." The Portuguese expelled the Jesuits in 1759 and the French in 1764, so the Spanish crown's move against them was part of a larger assertion of regal power in Europe and their overseas territories. Since the Jesuits had been the premier educators of elite young men in New Spain and the preferred order if a young man had a vocation for the priesthood, the connection between the Jesuits and creole elites was close. Their churches were magnificent, sometimes more opulent than the cathedral (the main church of a diocese). Their estates were well run and profitable, funding both their educational institutions as well as frontier missions. The expulsion of the Jesuits meant the exile of their priests, many of them to Italy, and for many creole families connected to the order by placing a son there, it meant splitting of elite families. One Mexican Jesuit who was expelled was

Francisco Javier Clavijero

Francisco Javier Clavijero Echegaray (sometimes ''Francesco Saverio Clavigero'') (September 9, 1731 – April 2, 1787), was a Mexican Jesuit teacher, scholar and historian. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spanish provinces (1767), he ...

, who wrote a history of Mexico that extolled the Aztec past.

Charitable Institutions

Pious works (''obras pías'') were expressions of religious belief and the wealthy in Mexico established institutions to aid the poor, sometimes with the support of the Church and the crown. The 1777 establishment of what is now called

Nacional Monte de Piedad

The Nacional Monte de Piedad is a not-for-profit institution and pawnshop whose main office is located just off the Zócalo, or main plaza of Mexico City. It was commanded to be built between 1774 and 1777 by Don Pedro Romero de Terreros, the Cou ...

allowed urban dwellers who had any property at all to pawn access to interest-free, small-scale credit. It was established by the Count of

Regla

Regla () is one of the 15 municipalities or boroughs (''municipios'' in Spanish) in the city of Havana, Cuba. It comprises the town of Regla, located at the bottom of Havana Bay in a former aborigine settlement named ''Guaicanamar'', Loma Model ...

, who had made a fortune in silver mining, and the pawnshop continues to operate as a national institution in the twenty-first century, with its headquarters still right off the

Zócalo

The Zócalo () is the common name of the main square in central Mexico City. Prior to the colonial period, it was the main ceremonial center in the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan. The plaza used to be known simply as the "Main Square" or "Arms Sq ...