History of Prague on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Prague covers more than a thousand years, during which time the city grew from the Vyšehrad Castle to the capital of a modern

The history of Prague covers more than a thousand years, during which time the city grew from the Vyšehrad Castle to the capital of a modern

From around 900 until 1306, Czech

From around 900 until 1306, Czech

excerpt and text search

* Cohen, Gary B. ''The Politics of Ethnic Survival: Germans in Prague, 1861–1914.'' (1981). 344 pp. * Fucíková, Eliska, ed. ''Rudolf II and Prague: The Court and the City.'' (1997). 792 pp. * Holz, Keith. ''Modern German Art for Thirties Paris, Prague, and London: Resistance and Acquiescence in a Democratic Public Sphere.'' (2004). 359 pp. * Iggers, Wilma Abeles. ''Women of Prague: Ethnic Diversity and Social Change from the Eighteenth Century to the Present.'' (1995). 381 pp

online edition

* Kleineberg, A., Marx, Ch., Knobloch, E., Lelgemann, D.: Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios`"Atlas der Oikumene". WBG 2010. . * Porizka, Lubomir; Hojda, Zdenek; and Pesek, Jirí. ''The Palaces of Prague.'' (1995). 216 pp. * Sayer, Derek. "The Language of Nationality and the Nationality of Language: Prague 1780–1920." ''Past & Present'' 1996 (153): 164–210. * Sayer, Derek. ''Prague, Capital of the Twentieth Century: A Surrealist History'' (Princeton University Press; 2013) 595 pages; a study of the city as a crossroads for modernity. * Spector, Scott. ''Prague Territories: National Conflict and Cultural Innovation in Kafka's Fin de Siècle.'' (2000). 331 pp

online edition

* Svácha, Rostislav. ''The Architecture of New Prague, 1895–1945.'' (1995). 573 pp. * Wittlich, Peter. ''Prague: Fin de Siècle.'' (1992). 280 pp. * Wilson, Paul. ''Prague: A Traveler's Literary Companion'' (1995) * ''Prague'' Top 10 (2011

Prague Top 10

myczechrepublic, History of Prague

conference-consult, History of Prague

{{Authority control Populated places established in the 9th century

The history of Prague covers more than a thousand years, during which time the city grew from the Vyšehrad Castle to the capital of a modern

The history of Prague covers more than a thousand years, during which time the city grew from the Vyšehrad Castle to the capital of a modern Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an state, the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

.

Prehistory

The land where Prague came to be built has been settled since thePaleolithic Age

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος '' lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

. Several thousand years ago, trade routes connecting southern and northern Europe passed through this area, following the course of the river. From around 500 BC the Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic tribe known as the Boii

The Boii ( Latin plural, singular ''Boius''; grc, Βόιοι) were a Celtic tribe of the later Iron Age, attested at various times in Cisalpine Gaul ( Northern Italy), Pannonia ( Hungary), parts of Bavaria, in and around Bohemia (after whom ...

were the first inhabitants of this region known by name. The Boii gave their name to the region of Bohemia and the river Vltava. The Germanic tribe Marcomanni

The Marcomanni were a Germanic people

*

*

*

that established a powerful kingdom north of the Danube, somewhere near modern Bohemia, during the peak of power of the nearby Roman Empire. According to Tacitus and Strabo, they were Suebian.

O ...

migrated to Bohemia with its king, Maroboduus

Maroboduus (d. AD 37) was a king of the Marcomanni, who were a Germanic Suebian people. He spent part of his youth in Rome, and returning, found his people under pressure from invasions by the Roman empire between the Rhine and Elbe. He led the ...

, in AD 9. Meanwhile, some of the Celts migrated southward while the remainder assimilated with the Marcomanni. In 568, most of the Marcomanni migrated southward with the Lombards, another Germanic tribe. The rest of the Marcomanni assimilated with the invading West Slavs

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic la ...

. (The "Migration of Nations" started in the 2nd century; it ended at the end of the 9th and at the beginning of the 10th centuries). The Byzantine historian Prokopios mentions the presence of the Slavs in these lands in AD 512.

According to legend, Princess Libuše

, Libussa, Libushe or, historically ''Lubossa'', is a legendary ancestor of the Přemyslid dynasty and the Czech people as a whole. According to legend, she was the youngest but wisest of three sisters, who became queen after their father died; ...

, the sovereign of the Czech tribe, married a humble ploughman by the name of Přemysl and founded the dynasty carrying the same name. The legendary princess saw many prophecies from her castle Libusin, which was located in central Bohemia. (Archaeological finds dating back to the eighth century support the theory of the castle's location). In one prophecy, it is told, she foresaw the glory of Prague. One day she had a vision: "I see a vast city, whose glory will touch the stars! I see a place in the middle of a forest where a steep cliff rises above the Vltava River. There is a man, who is chiselling the threshold (''prah'') for the house. A castle named Prague (''Praha'') will be built there. Just as the princes and the dukes stoop in front of a threshold, they will bow to the castle and to the city around it. It will be honoured, favoured with great repute, and praise will be bestowed upon it by the entire world."

Medieval Prague

From around 900 until 1306, Czech

From around 900 until 1306, Czech Přemyslid dynasty

The Přemyslid dynasty or House of Přemyslid ( cs, Přemyslovci, german: Premysliden, pl, Przemyślidzi) was a Bohemian royal dynasty that reigned in the Duchy of Bohemia and later Kingdom of Bohemia and Margraviate of Moravia (9th century–1 ...

rulers had most of Bohemia under their control. The first Bohemian ruler acknowledged by historians was the Czech Prince Bořivoj Přemyslovec, who ruled in the second half of the 9th century. He and his wife Ludmila (who became a patron saint of Bohemia after her death) were baptised by Metodej, who (together with his brother Cyril

Cyril (also Cyrillus or Cyryl) is a masculine given name. It is derived from the Greek name Κύριλλος (''Kýrillos''), meaning 'lordly, masterful', which in turn derives from Greek κυριος (''kýrios'') 'lord'. There are various varian ...

) brought orthodox Christianity and a new alphabet called Glagolitic script

The Glagolitic script (, , ''glagolitsa'') is the oldest known Slavic alphabet. It is generally agreed to have been created in the 9th century by Saint Cyril, a monk from Thessalonica. He and his brother Saint Methodius were sent by the Byza ...

to Moravia in 863 which would later be suppressed by the latin Franks. Bořivoj moved his seat from the fortified settlement Levý Hradec to a place called Prague (Praha). Prague Castle was built by Bořivoj around 880, and it is one of the largest castles in the world. Since Bořivoj's reign the area has been the seat of the Czech rulers. Prague Castle became one of the largest inhabited fortresses in Europe. Today, it is the seat of the Czech president.

Bořivoj's grandson, Prince Wenceslas, initiated friendly relations with the Saxon dynasty. Wenceslas wanted Bohemia to become an equal partner in the larger empire. (In a similar way, Bohemia had belonged to Great Moravia

Great Moravia ( la, Regnum Marahensium; el, Μεγάλη Μοραβία, ''Meghálī Moravía''; cz, Velká Morava ; sk, Veľká Morava ; pl, Wielkie Morawy), or simply Moravia, was the first major state that was predominantly West Slavic to ...

in the 9th century and to Samo's empire in the 7th century; both of these empires had been founded to resist the attacks of the Avars). Orientation towards the Saxons was not favoured by his brother Boleslav, and it was the main reason why Prince Wenceslas was assassinated on September 28, 935. He was buried in St. Vitus' Rotunda, the church which he founded. (It stood on the ground where St. Wenceslas' Chapel in St. Vitus Cathedral

, native_name_lang = Czech

, image = St Vitus Prague September 2016-21.jpg

, imagesize = 300px

, imagelink =

, imagealt =

, landscape =

, caption ...

now is). A few years later Wenceslas was canonised and became Bohemia's most beloved patron saint. (He is " Good King Wenceslas" from the Christmas carol.) In 950, after long war, Boleslav was forced to accept the supremacy of Otto I the Great from the Saxon dynasty, who later became the emperor. From 1002 (definitely 1041) onward Bohemian dukes and kings were vassals of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

s and Czech lands appertained to Holy Roman Empire as autonomous territory.

By the early 10th century, the area around and below Prague Castle had developed into an important trading centre, where merchants from all over Europe gathered. In 965, an Arab merchant and traveller, called Ibrahim ibn Ya'qub wrote: "Prague is built from stone and lime, and it has the biggest trade centre. Slavs are on the whole courageous and brave... They occupy the lands which are the most fertile and abundant with a good food supply."

In 973, a bishopric was founded in Bohemia with the bishop's palace located on the Prague castle grounds. The first Czech bishop was Vojtěch ( St. Adalbert) from the Czech noble family of Slavník, who later evangelized Poles and Hungarians and became a patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

to Czechs, Poles and Hungarians after his canonization in 999.

Next to the Romanesque fortified settlement of Prague, another Romanesque fortified settlement was built across the river Vltava at Vyšehrad

Vyšehrad ( Czech for "upper castle") is a historic fort in Prague, Czech Republic, just over 3 km southeast of Prague Castle, on the east bank of the Vltava River. It was probably built in the 10th century. Inside the fort are the Basil ...

in the 11th century. During the reign of Prince Vratislav II

Vratislaus II (or Wratislaus II) ( cs, Vratislav II.) (c. 1032 – 14 January 1092), the son of Bretislaus I and Judith of Schweinfurt, was the first King of Bohemia as of 15 June 1085, his royal title granted as a lifetime honorific from Holy ...

, who rose to the title of King of Bohemia Vratislav I in 1085, Vyšehrad became the temporary seat of Czech rulers.

Prince Vladislav II rose to the title of King of Bohemia Vladislav I in 1158. Many monasteries and many churches were built under the rule of Vladislav I. The Strahov Monastery, built after the Romanesque style, was founded in 1142. The first stone bridge over the river Vltava — the Judith Bridge — was built in 1170. (It collapsed in 1342 and a new bridge, later called the Charles Bridge

Charles Bridge ( cs, Karlův most ) is a medieval stone arch bridge that crosses the Vltava river in Prague, Czech Republic. Its construction started in 1357 under the auspices of King Charles IV, and finished in the early 15th century.; ...

was built in its place in 1357.)

In 1212, Bohemia became a hereditary kingdom when Prince Přemysl Otakar I rose to the title of King by inheritance from Frederick II (Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

from 1215), which was legalised in the document called the "Golden Bull of Sicily

The Golden Bull of Sicily ( cs, Zlatá bula sicilská; la, Bulla Aurea Siciliæ) was a decree issued by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in Basel on 26 September 1212 that confirmed the royal title obtained by Ottokar I of Bohemia in 1198, dec ...

". The king's daughter, Agnes, became another Bohemian saint. Agnes preferred to enter a convent rather than to marry Emperor Frederick II. During the reign of King Premysl Otakar I, peaceful colonisation started. The German colonists were invited both to Bohemia and Moravia. For hundreds of years this duality of population did not cause any problem - before nationalism had become a world force.

In the 13th century, towns started to increase in size, driven by institution of German town law

The German town law (german: Deutsches Stadtrecht) or German municipal concerns (''Deutsches Städtewesen'') was a set of early town privileges based on the Magdeburg rights developed by Otto I. The Magdeburg Law became the inspiration for regiona ...

and immigration of Germans. Three settlements around the Prague Castle gained the privilege of a town. Across the river Vltava, the Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

of Prague — ''Staré Město'' gained the privilege of a town in 1230,

The settlement below Prague Castle became the New Town of Prague in 1257 under King Otakar II, and it was later renamed Lesser Town (or Quarter) of Prague — ''Malá Strana

Malá Strana (Czech for "Little Side (of the River)", ) or more formally Menší Město pražské () is a district of the city of Prague, Czech Republic, and one of its most historic neighbourhoods.

In the Middle Ages, it was a dominant cente ...

''. The Castle District — ''Hradčany

Hradčany (; german: Hradschin), the Castle District, is the district of the city of Prague, Czech Republic surrounding Prague Castle.

The castle is one of the biggest in the world at about in length and an average of about wide. Its histo ...

'' which was built around its square, just outside Prague Castle, dates from 1320.

In the 13th century, King Přemysl Otakar II was the most powerful king in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

during his reign, known as the "Iron and Golden King". He ruled in Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Styria

Styria (german: Steiermark ; Serbo-Croatian and sl, ; hu, Stájerország) is a state (''Bundesland'') in the southeast of Austria. With an area of , Styria is the second largest state of Austria, after Lower Austria. Styria is bordered ...

, Carniola

Carniola ( sl, Kranjska; , german: Krain; it, Carniola; hu, Krajna) is a historical region that comprised parts of present-day Slovenia. Although as a whole it does not exist anymore, Slovenes living within the former borders of the region s ...

, Carinthia

Carinthia (german: Kärnten ; sl, Koroška ) is the southernmost Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The main language is German. Its regional dialects belong to the Southern Bavarian group. Carin ...

, Egerland and Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giuli ...

. His domain stretched from the Sudetes

The Sudetes ( ; pl, Sudety; german: Sudeten; cs, Krkonošsko-jesenická subprovincie), commonly known as the Sudeten Mountains, is a geomorphological subprovince in Central Europe, shared by Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic. They consi ...

to the Adriatic sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to th ...

. Otakar II. hoped that the 6 other prince-electors

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the prince ...

would choose him as the king of Romans but at imperial election in 1273

Year 1273 ( MCCLXXIII) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* January 22 – Sultan Muhammad I (or Ibn al-Ahmar) suffers fatal injuries after fa ...

the 6 other electors thought that Otakar II. was too risky so they chose a Rudolf I. Habsburg as the emperor. Rudolf Habsburg was a weak ruler which was the primary reason the electors chose him so they could keep their power and land they acquired from the Great Interregnum (1245-1312). Otakar II. himseld being a prince-electors was outraged and wasn't present at Rudolf's coronation. When Rudolf requested that Otakar II. be present at the imperial diet in Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

Otakar refused. Rudolf placed an imperial ban

The imperial ban (german: Reichsacht) was a form of outlawry in the Holy Roman Empire. At different times, it could be declared by the Holy Roman Emperor, by the Imperial Diet, or by courts like the League of the Holy Court (''Vehmgericht'') or t ...

on him which made him lose all his territory acquired during the interregnum.

Otakar's plans weren't to abide to Rudolf and he slowly assembled and army but unfortunately lost and died against Rudolf I. in the battle of Marchfeld on 26 August 1278. His son Wenceslaus II. was still very young and would have to burden the great turmoil that has arisen in Bohemia.

The Přemyslid dynasty

The Přemyslid dynasty or House of Přemyslid ( cs, Přemyslovci, german: Premysliden, pl, Przemyślidzi) was a Bohemian royal dynasty that reigned in the Duchy of Bohemia and later Kingdom of Bohemia and Margraviate of Moravia (9th century–1 ...

ruled until 1306 when the male line died out. The inheriting dynasty was the Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

dynasty when the father of John of Luxembourg emperor Henry VII

Henry VII ( German: ''Heinrich''; c. 1273 – 24 August 1313),Kleinhenz, pg. 494 also known as Henry of Luxembourg, was Count of Luxembourg, King of Germany (or '' Rex Romanorum'') from 1308 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1312. He was the first em ...

wanted to prevent Henry of Carinthia

Henry of Gorizia (german: Heinrich, cs, Jindřich; – 2 April 1335), a member of the House of Gorizia, was Duke of Carinthia and Landgrave of Carniola (as Henry VI) and Count of Tyrol from 1295 until his death, as well as King of Bohemia, Mar ...

to get the bohemian throne so he offered his son John of Luxembourg the bohemian throne if he was to marry the sister of the killed Wenceslaus III of Bohemia Elizabeth of Bohemia

Elizabeth Stuart (19 August 159613 February 1662) was Electress of the Palatinate and briefly Queen of Bohemia as the wife of Frederick V of the Palatinate. Since her husband's reign in Bohemia lasted for just one winter, she is called the Wi ...

. It took a long time for the young John but he decided to accept. He married Elizabeth on 7 of September 1310 and was now heading to Prague to be crowned. But his rival Henry of Carinthia had claimed the throne before he could arrive. John mustered a large army with the help of his father and when he arrived to Prague Henry of Carinthia ran away allowing John to claim the bohemian throne and be crowned on the 7 of February 1311.

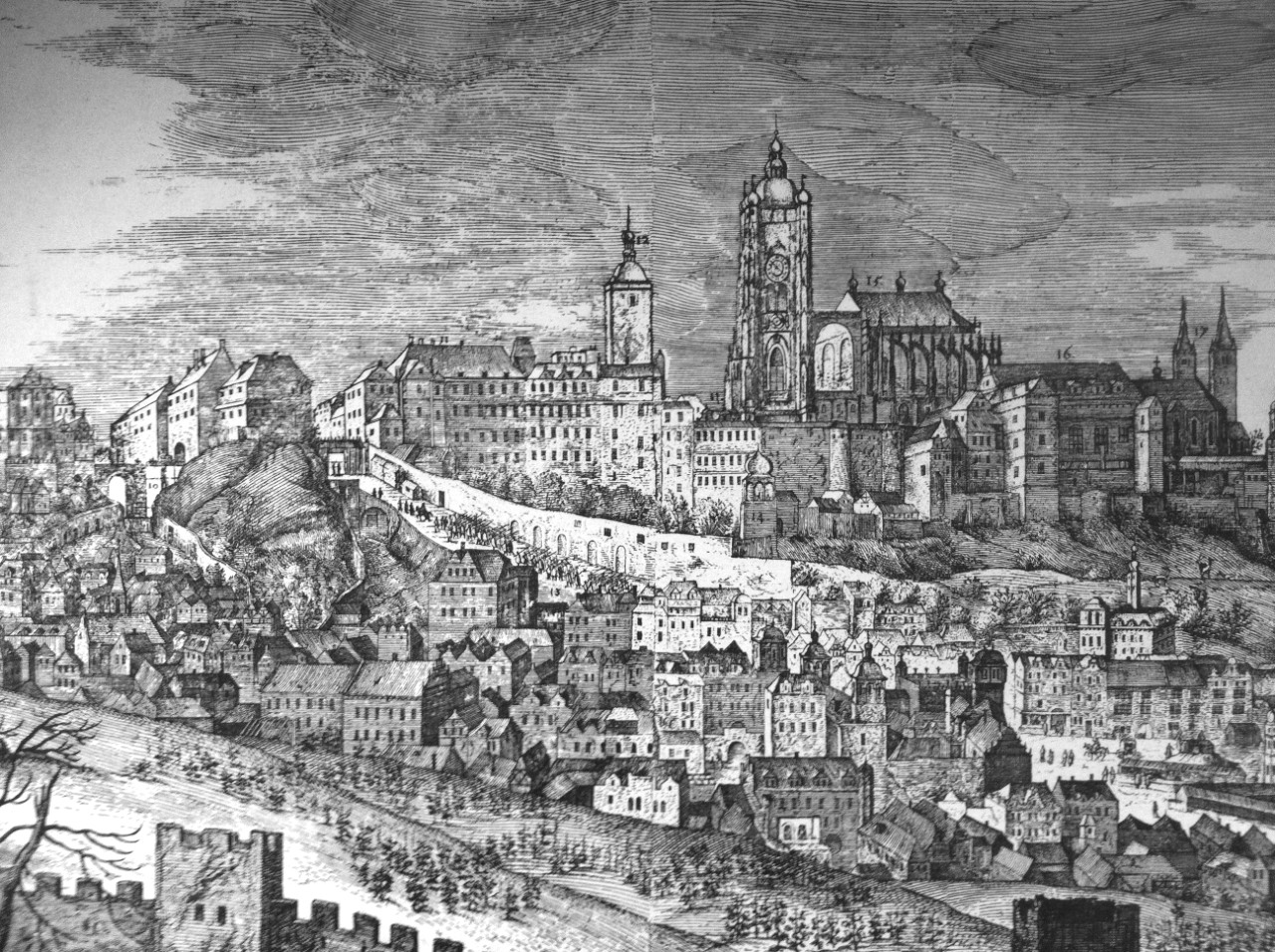

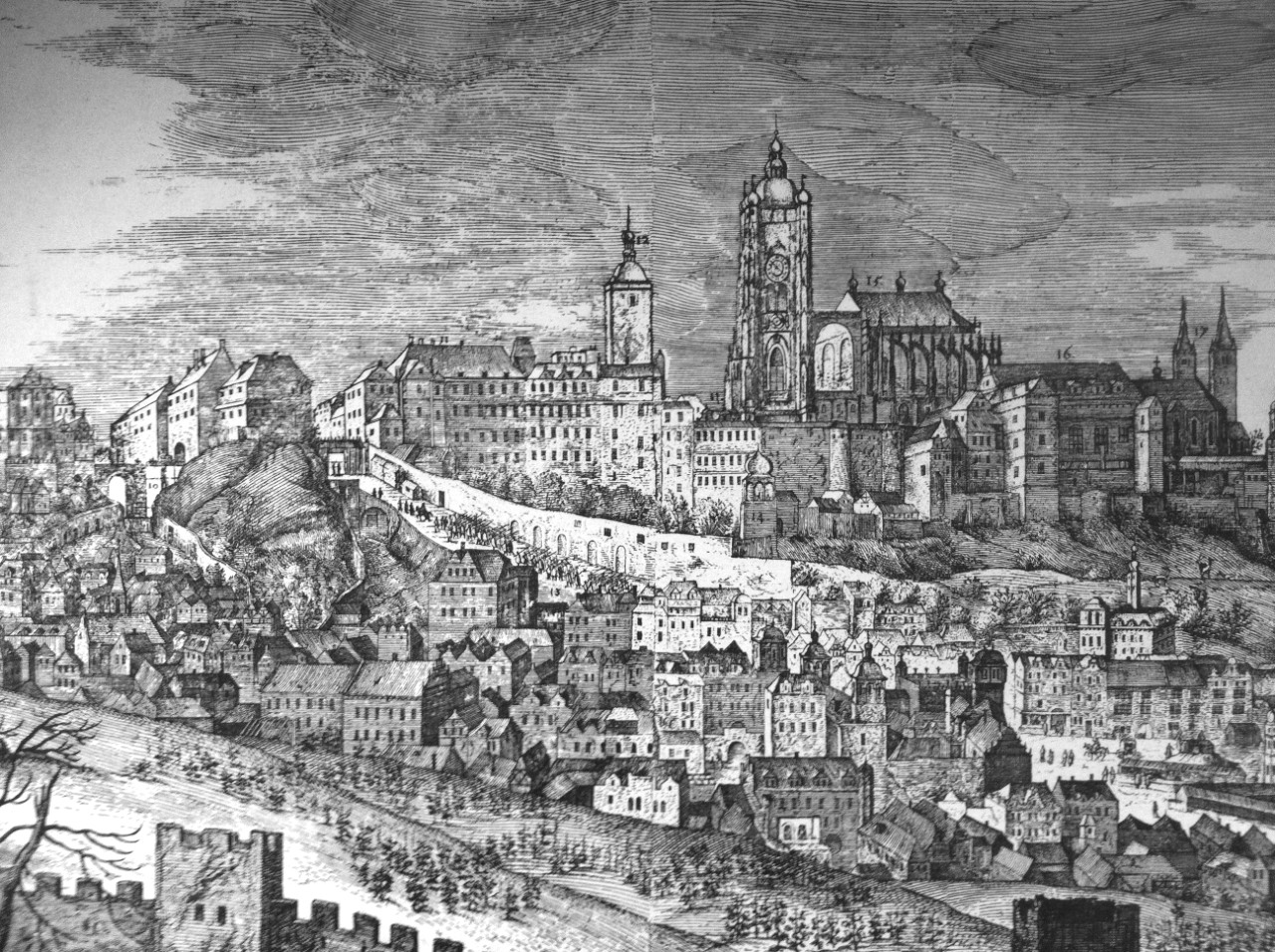

Renaissance

The city flourished during the 14th century during the reign of Charles IV, of the Luxembourg dynasty. Charles was the eldest son of Czech Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia and John of Luxembourg. He was born in Prague in 14 of May 1316 and became King of Bohemia upon the death of his father in 1346. Due to Charles's efforts, the bishopric of Prague was raised to an archbishopric in 1344 and the first archbishop was Arnošt z Pardubic who was a close advisor to Charles. On April 7, 1348 he founded the first university in central, northern and eastern Europe, now calledCharles University

)

, image_name = Carolinum_Logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, established =

, type = Public, Ancient

, budget = 8.9 billion CZK

, rector = Milena Králíčková

, faculty = 4,057

, administrative_staff = 4,026

, students = 51,438

, under ...

, the oldest Czech university. In the same year with inspiration of Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

he also founded New Town

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

(''Nové Město'') with adjacent to the Old Town. Charles rebuilt Prague Castle and Vysehrad, and a new bridge was erected, now called the Charles Bridge

Charles Bridge ( cs, Karlův most ) is a medieval stone arch bridge that crosses the Vltava river in Prague, Czech Republic. Its construction started in 1357 under the auspices of King Charles IV, and finished in the early 15th century.; ...

. The construction of St. Vitus' Cathedral had also begun. Many new churches were founded. In 1355, Charles was crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in Rome. Prague became the capital of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

. Charles wanted Prague to become one of the most beautiful cities in the world and to make it a new center of art, science and prestige. He wanted Prague to be the dominant city of the whole empire, with Prague Castle as the dominant site in the city and the stately Gothic Cathedral to be more dominant than Prague Castle. Everything was built in a grandiose Gothic style and decorated with an independent art style, called the Bohemian school. During the reign of Emperor Charles IV, the Czech Lands were among the most powerful in Europe.

All that changed during the reign of weak King Wenceslas IV, son of Charles IV. During the reign of King Wenceslas IV

Wenceslaus IV (also ''Wenceslas''; cs, Václav; german: Wenzel, nicknamed "the Idle"; 26 February 136116 August 1419), also known as Wenceslaus of Luxembourg, was King of Bohemia from 1378 until his death and King of Germany from 1376 until he ...

—''Václav IV''—(1378–1419), Master Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the insp ...

, a preacher and the university's rector, held his sermons in Prague in the Bethlehem Chapel, speaking in Czech to enlarge as much as possible the diffusion of his ideas about the reformation of the church. His execution in 1415 in Constance (accused of heresy) led four years later to the Hussite wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, Eur ...

(following the defenestration

Defenestration (from Modern Latin ) is the act of throwing someone or something out of a window.

The term was coined around the time of an incident in Prague Castle in the year 1618 which became the spark that started the Thirty Years' War. ...

, when the people rebelled under the command of the Prague priest Jan Želivský

Jan Želivský (1380 in Humpolec – 9 March 1422 in Prague) was a prominent Czech priest during the Hussite Reformation.

Life

Želivský preached at Church of Saint Mary Major. He was one of a few Utraquist

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub u ...

and threw the city's councillors from the New Town Hall). King Wenceslas IV died 16 days later. His younger stepbrother Sigismund was the legitimate heir to the throne. But the Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

opposed Sigismund and so he came to Prague with an army of 30,000 crusaders. He planned to make Prague capitulate and to take the crown. In 1420, peasant rebels, led by the famous general Jan Žižka

Jan Žižka z Trocnova a Kalicha ( en, John Zizka of Trocnov and the Chalice; 1360 – 11 October 1424) was a Czech general – a contemporary and follower of Jan Hus and a Radical Hussite who led the Taborites. Žižka was a successful milit ...

, along with Hussite troops, defeated Sigismund (''Zikmund'', son of Charles IV) in the Battle of Vítkov Mountain. There were more crusades, all of which ended in failure. But after Žižka died, the Hussite lost their focus. Eventually they split into groups. The most radical Hussites were finally defeated at the battle of Lipany in 1434

Year 1434 ( MCDXXXIV) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–December

* April 14 – The foundation stone of Nantes Cathedral in Nantes, France, is laid ...

when the moderate Hussites got together with the Czech Catholics. Sigismund became King of Bohemia.

In 1437

Year 1437 ( MCDXXXVII) was a common year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–December

* February 20– 21 – James I of Scotland is fatally stabbed at Perth in a f ...

, Sigismund died. The male line of the Luxembourg dynasty died out. The husband of Sigismund's daughter Elizabeth, Albert II, Duke of Austria, became the Bohemian king for two years (until his death). Then, the next in line for Bohemian crown was the grandson of Sigismund, born after his father's death, and thus called Ladislaw Posthumous (Posthumous because he was born after his father's death). When he died at 17 years old, the nobleman George of Poděbrady

George of Kunštát and Poděbrady (23 April 1420 – 22 March 1471), also known as Poděbrad or Podiebrad ( cs, Jiří z Poděbrad; german: Georg von Podiebrad), was the sixteenth King of Bohemia, who ruled in 1458–1471. He was a leader of the ...

, former adviser of Ladislaus, was chosen as the Bohemian king both by the Catholics and by the Utraquist Hussites. He was called the Hussite king. During his reign, the Pope called for a crusade against the Czech heretics. The crusade was led by the King of Hungary Matthius Corvinus who, after the crusade, became also the King of Bohemia. George did not abdicate. Bohemia had two kings. George, before his death, made an arrangement with the Polish King Casimir IV that the next Bohemian king would come from the Jagellon dynasty. (The wife of King Casimir IV was the sister of late Ladislaus Posthumous and so her son Vladislav was related to the Luxembourg dynasty and also to the original Bohemian Premyslovec dynasty). The Jagiellonian dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty (, pl, dynastia jagiellońska), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty ( pl, dynastia Jagiellonów), the House of Jagiellon ( pl, Dom Jagiellonów), or simply the Jagiellons ( pl, Jagiellonowie), was the name assumed by a cad ...

ruled only until 1526 when it died out with Ludwig Jagiellon, son of Vladislaus II Jagiellon.

The next Bohemian king was Ferdinand Habsburg, husband of Ann Jagellon, who was the sister of Ludwig Jagellon. It was the beginning of the Habsburg dynasty. After Ferdinand's brother Charles V resigned in 1556 as Emperor, Ferdinand was elected Emperor in 1558. After he died, his son Maximilian II inherited all his titles and then upon his death, his son Rudolf II inherited them in turn. It was during the reign of Emperor Rudolf II, when there was another glorious time for Prague. Prague became the cultural centre of the Holy Roman Empire again. Rudolf was related to the Jagellon dynasty, to the Luxemburg dynasty and to the Premyslovec dynasty. But he was also related to Spanish Joan the Mad (the daughter of Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon); Joan was the mother of Rudolf's grandfather. Although Rudolf II was very talented, he was eccentric and he suffered from depression. Emperor Rudolf II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the Ho ...

lived in Prague Castle, where he held his bizarre courts of astrologers, magicians and other strange figures. But it was a prosperous period for the city; famous people living there included the astronomers Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

and Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

, the painters Giuseppe Arcimboldo

Giuseppe Arcimboldo (; also spelled ''Arcimboldi'') (1526 or 1527 – 11 July 1593) was an Italian painter best known for creating imaginative portrait heads made entirely of objects such as fruits, vegetables, flowers, fish and books.

These wo ...

, B. Spranger, Hans von Aachen, J. Heintz and others. In 1609, under the influence of the Protestant Estates, Rudolf II (a devout Catholic), issued an "Imperial Charter of the Emperor" in which he legalised extensive religious freedoms unparalleled in the Europe of that period. Many German Protestants (both Lutherans and Calvinists) immigrated to Bohemia. (One of them was Count J.M. Thurn, a German Lutheran; under his leadership the Second Defenestration of Prague happened in 1618, leading to the Thirty Years' War).

Next in line for Bohemian crown was Rudolf's brother Matthias, but since Matthias was childless, his cousin, the archduke Ferdinand of Styria (related also to Jagellon, Luxemburg and Premyslovec Dynasties), was initially accepted by the Bohemian Diet as heir presumptive when Matthias became ill. The Protestant Estates of Bohemia didn't like this decision. Tension between the Protestants and the pro-Habsburg Catholics led to the Second Defenestration of Prague, when the Catholic governors were thrown from the windows of Prague Castle on May 23, 1618. They survived, but the Protestants replaced the Catholic governors. This incident led to the Thirty Years' War. When Matthias died, Ferdinand of Styria was elected Emperor as Emperor Ferdinand II, but was not accepted as King of Bohemia by the Protestant directors. The Calvinist Frederick V of Pfalz was elected King of Bohemia. The Battle on the White Mountain followed on November 8, 1620. Emperor Ferdinand II was helped not only by Catholic Spain, Catholic Poland, and Catholic Bavaria, but also by Lutheran Saxony (which disliked the Calvinists). The Protestant army, led by the warrior Count J. M. Thurn, was formed mostly from Lutheran Silesia, Lusatia, and Moravia. It was mainly a battle between Protestants and Catholics. The Catholics won and Emperor Ferdinand II became King of Bohemia. He proclaimed the re-Catholicisation of the Czech Lands. Twenty-seven Protestant leaders were executed in the Old Town Square

Old Town Square ( cs, Staroměstské náměstí or colloquially ) is a historic square in the Old Town quarter of Prague, the capital of the Czech Republic. It is located between Wenceslas Square and Charles Bridge.

Buildings

The square ...

in Prague on June 21, 1621. (Three noblemen, seven knights and seventeen burghers were executed, including Dr. Jan Jesenius, the Rector of Prague University.) Most of the Protestant leaders fled, including Count J. M. Thurn; those who stayed didn't expect harsh punishment. The Protestants had to return all the seized Catholic property to the Church. No faith other than Catholicism was permitted. The upper classes were given the option either to emigrate or to convert to Catholicism. The German language was given equal rights with the Czech language. After the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

, Ferdinand II moved the court to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and Prague began a steady decline which reduced the population from the 60,000 it had had in the years before the war to 20,000.

Jewish quarter

The 17th century is considered the Golden Age of Jewish Prague. TheJewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

community of Prague numbered some 15,000 people (approx. 30 per cent of the entire population), making it the largest Ashkenazic

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

community in the world and the second largest Jewish community in Europe after Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

. In the years 1597 to 1609, the Maharal (Judah Loew ben Bezalel

Judah Loew ben Bezalel (; between 1512 and 1526 – 17 September 1609), also known as Rabbi Loew ( Löw, Loewe, Löwe or Levai), the Maharal of Prague (), or simply the Maharal (the Hebrew acronym of "''Moreinu ha-Rav Loew''", 'Our Teacher, Rabbi ...

) served as Prague's chief rabbi. He is considered the greatest of Jewish scholars in Prague's history, his tomb in the Old Jewish Cemetery eventually becoming a pilgrimage site.

The expulsion of Jews from Prague by Maria Theresa of Austria

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position '' suo jure'' (in her own right) ...

in 1745 based on their alleged collaboration with the Prussian army was a severe blow to the flourishing Jewish community. The Queen allowed the Jews to return to the city in 1748. In 1848 the gates of the Prague ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

were opened. The former Jewish quarter, renamed Josefov in 1850, was demolished during the "ghetto clearance" (Czech: asanace) around the start of the 20th century.

18th century

In 1689 a great fire devastated Prague, but this spurred a renovation and a rebuilding of the city. The economic rise continued through the following century, and in 1771 the city had 80,000 inhabitants. Many of these were rich merchants who, together with noblemen, enriched the city with a host of palaces, churches and gardens, creating aBaroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

style renowned throughout the world. In 1784, under Joseph II

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 un ...

, the four municipalities of Malá Strana, Nové Město, Staré Město and Hradčany were merged into a single entity. The Jewish district, called Josefov, was included only in 1850. The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

had a strong effect in Prague, as factories could take advantage of the coal mines and ironworks of the nearby region. A first suburb, Karlín, was created in 1817, and twenty years later the population exceeded 100,000. The first railway connection was built in 1842.

19th century

In 1806, the Holy Roman Empire ended when Napoleon dictated its dissolution. Holy Roman Emperor Francis II abdicated his title. He became Francis I, Emperor of Austria. At the same time as the Industrial Revolution was developing, the Czechs were also going through the Czech National Revival movement: political and cultural changes demanded greater autonomy. Since the late 18th century, Czech literature occupied an important position in the Czech culture. The revolutions that shocked all of Europe around 1848 touched Prague too, but they were fiercely suppressed. In the following years the Czech nationalist movement (opposed to another nationalist party, the German one) began its rise, until it gained the majority in the Town Council in 1861. In 1867, Emperor Francis Joseph I established the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy of the Austrian Empire and Kingdom of Hungary.20th century

The next in succession to the Austro-Hungarian throne was Francis Ferdinand d'Este after Crown Prince Rudolf (son of the emperor Francis Joseph I) had committed suicide and after the Emperor's brother (Ferdinand's father) had died. Ferdinand (related also to Jagellon, Luxemburg and Premyslovec Dynasties) was married to Sophie von Chotek from a Czech aristocratic family. They lived in Bohemia at the Konopiste Castle, not far from Prague. He was in favour of a Triple Monarchy, expanding an Austro-Hungary Dualism into Austro-Hungary-Czech Triple Monarchy, but on June 28, 1914 he and his wife were assassinated in Sarajevo. This assassination led to World War I.World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

ended with the defeat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

and, with the help of Tomas Garrigue Masaryk who was going around the world trying to find political support, the creation of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. Apart from just having Czechia and Slovakia during the war in 1919 in Austry-Hungary Czechoslovakia was granted Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

. Prague was chosen as its capital. At this time Prague was a European city with developed industrial background. In 1930 the population had risen to 850,000.

For most of its history Prague had been an ethnically mixed city with important Czech, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, and Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

populations. Prague had German-speaking near-majority in 1848, but by 1880 the German population decreased to 13.52 percent, and by 1910 to 5.97 percent, due to a massive increase of the city's overall population caused by the influx of Czechs from the rest of Bohemia and Moravia and also due to the assimilation of some Germans. As a result, the German minority along with the German-speaking Jewish community remained mainly in the central, ancient parts of city, while the Czechs had a near-absolute majority in the fast-growing suburbs of Prague. As late as 1880, Germans speakers still formed 22 percent of the population of Stare Mesto (the Old Town), 16 percent in Nove Mesto (the New Town), 20 percent in Mala strana (the Little Quarter), 9 percent in Hradcany, and 39 percent in the former Jewish Ghetto of Josefov.

When Czechoslovakia gained independence, the Prague Germans experienced discrimination. Prague Mayor Karel Baxa banned the posting of notices in German and the inscription of burial urns in German.

As in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

nationalistic and fascist movements gained ground in the first half of the 20th. century, Prague German underwent a revival as German speaking emigrants settled in the town. Famous German speaking writers such as Max Brod, Egon Erwin Kisch

Egon Erwin Kisch (29 April 1885 – 31 March 1948) was an Austrian and Czechoslovak writer and journalist, who wrote in German. He styled himself ''Der Rasende Reporter'' (The Raging Reporter) for his countless travels to the far corners of the ...

, Joseph Roth, Alfred Döblin

Bruno Alfred Döblin (; 10 August 1878 – 26 June 1957) was a German novelist, essayist, and doctor, best known for his novel ''Berlin Alexanderplatz'' (1929). A prolific writer whose œuvre spans more than half a century and a wide variety of ...

, Egon Friedell, Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short-story writer, widely regarded as one of the major figures of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of realism and the fantastic. It typ ...

, and Leo Perutz wrote for the liberal German language newspaper Prager Tagblatt

The ''Prager Tagblatt'' was a German language newspaper published in Prague from 1876 to 1939. Considered to be the most influential liberal-democratic German newspaper in Bohemia, it stopped publication after the German occupation of Czechos ...

.

From 1939, when the country was occupied by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, most Jews either fled the city or were killed in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

. Most of the Jews living in Prague after the war emigrated during the years of Communism, particularly after the communist coup, the establishment of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

in 1948, and the Soviet invasion in 1968. In the early 1990s, the Jewish Community in Prague numbered only 800 people compared to nearly 50,000 before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. In 2006, some 1,600 people were registered in the Jewish Community.

During the Nazi German occupation of Czechoslovakia Prague citizens were oppressed and persecuted by the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

. Politicians (e.g. prime minister Alois Eliáš

Alois Eliáš (29 September 1890 – 19 June 1942) was a Czech general and politician. He served as prime minister of the puppet government of the German-occupied Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from 27 April 1939 to 27 September 1941 bu ...

), university professors and students and many others were murdered, imprisoned or sent to concentration camps. Prague was a target of several allied bombings, the deadliest one occurring on February 14, 1945, when large parts of the city centre were destroyed, leaving over 700 people dead and nearly 1200 injured. The Prague uprising

The Prague uprising ( cs, Pražské povstání) was a partially successful attempt by the Czech resistance movement to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation in May 1945, during the end of World War II. The preceding six years of o ...

started on May 5, 1945 when Prague's Czech citizens, assisted by the defecting 1st Infantry Division of the Russian Liberation Army

The Russian Liberation Army; russian: Русская освободительная армия, ', abbreviated as (), also known as the Vlasov army after its commander Andrey Vlasov, was a collaborationist formation, primarily composed of Rus ...

, revolted against the Nazi German

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

occupiers. That same day, General Patton's American Third Army (with 150,000 soldiers) arrived in Pilsen (only a few hours away from Prague) while Marshal Konev's Soviet Army was on the borders of Moravia. General Patton was in favour of liberating Prague, but he had to comply with the instructions from General D. Eisenhower. General Eisenhower requested the Soviet Chief of Staff to permit them to press forward, but was informed that American help was not needed (a prior agreement from the Yalta Conference was that Bohemia would be liberated by the Red Army). Finally, on May 9, 1945 (the day after Germany officially capitulated) Soviet tanks reached Prague. It was not until May 12, 1945 that all fighting ceased in the Czech Lands. German occupation caused the death of 77,297 Czechoslovak Jews, whose names are inscribed on walls of the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague.

The German army left Prague in the morning of May 8. German-speaking Prague citizens were gathered brutally and expelled from their home city, similar to the expulsions carried out all over Czechoslovakia and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

. During this, a number of local massacres occurred resulting in an unknown number of fatalities.

After the war, Prague again became the capital of Czechoslovakia, now without significant Germans and Jews left in the city. Many Czechs genuinely felt gratitude towards the Soviet soldiers. Soviet troops left Czechoslovakia a couple of months after the war but the country remained under strong Soviet political influence. In February 1948, Prague became the centre of a communist coup.

The intellectual community of Prague, however, suffered under the totalitarian regime, in spite of the rather careful programme of rebuilding and caring for the damaged monuments after World War II. At the 4th Czechoslovakian Writers' Congress held in the city in 1967 a strong position against the regime was taken. This spurred the new secretary of the Communist Party, Alexander Dubček to proclaim a new phase in the city's and country's life, beginning the short-lived season of "socialism with a human face". This was the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First ...

, which aimed at a democratic reform of institutions. The Soviet Union and the rest of the Warsaw Pact, except for Romania, reacted, occupying Czechoslovakia and the capital in August 1968, suppressing any attempt at innovation under the treads of their tanks.

During the communist period little was actively done to maintain the beauty of the city's buildings. Due to the poor incentives offered by the regime, workers would put up scaffolding and then disappear to moonlighting jobs. Vaclavske Namesti (Wenceslas Square) was covered in such scaffolds for over a decade, with little repair ever being accomplished. True renovation began after the collapse of communism. The durability of renovations was aided by the fact that Prague converted almost entirely from coal heating in homes to electric heating. The coal burnt during the communist period was a major source of air pollution that corroded and spotted building façades, giving Prague the look of a dark, dirty city.

In 1989, after the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (german: Berliner Mauer, ) was a guarded concrete barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and East Germany (GDR). Construction of the Berlin Wall was commenced by the gover ...

had fallen, and the Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...

crowded the streets of Prague, Czechoslovakia freed itself from communism and Soviet influence, and Prague benefited deeply from the new mood. In 1993, after the split of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Prague became the capital city of the new Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

. Prague is capital of two administrative units of Czech Republic - Prague region ( cz, hlavní město Praha) and Central Bohemian Region

The Central Bohemian Region ( cz, Středočeský kraj, german: Mittelböhmische Region) is an administrative unit ( cz, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located in the central part of its historical region of Bohemia. Its administrative centre is in ...

( cz, Středočeský kraj). As Prague is not geographically part of Central Bohemian Region it is a capital outside of the territory it serves.

Timeline of important moments in Prague history

The four independent boroughs that had formerly constituted Prague were eventually proclaimed a single city in 1784. Those four cities wereHradčany

Hradčany (; german: Hradschin), the Castle District, is the district of the city of Prague, Czech Republic surrounding Prague Castle.

The castle is one of the biggest in the world at about in length and an average of about wide. Its histo ...

(the Castle District, west and north of the Castle), Little Quarter (Malá Strana, south of the Castle), Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

(Staré Město, on the east bank opposite the Castle) and New Town

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

(Nové Město, further south and east). The city underwent further expansion with the annexation of Josefov in 1850 and Vyšehrad

Vyšehrad ( Czech for "upper castle") is a historic fort in Prague, Czech Republic, just over 3 km southeast of Prague Castle, on the east bank of the Vltava River. It was probably built in the 10th century. Inside the fort are the Basil ...

in 1883, and at the beginning of 1922, another 37 municipalities were incorporated, raising the city's population to 676,000. In 1938 population reached 1,000,000.

Historical population

*The record of 1230 includes Staré Město only *The records of 1370 and 1600 includes Staré město, Nové město, Malá Strana and Hradčany quarters *Numbers beside other years denote the population of Prague within the administrative border of the city at that time.Further reading

* Becker, Edwin et al., ed. ''Prague 1900: Poetry and Ecstasy.'' (2000). 224 pp. * Burton, Richard D. E. ''Prague: A Cultural and Literary History.'' (2003). 268 ppexcerpt and text search

* Cohen, Gary B. ''The Politics of Ethnic Survival: Germans in Prague, 1861–1914.'' (1981). 344 pp. * Fucíková, Eliska, ed. ''Rudolf II and Prague: The Court and the City.'' (1997). 792 pp. * Holz, Keith. ''Modern German Art for Thirties Paris, Prague, and London: Resistance and Acquiescence in a Democratic Public Sphere.'' (2004). 359 pp. * Iggers, Wilma Abeles. ''Women of Prague: Ethnic Diversity and Social Change from the Eighteenth Century to the Present.'' (1995). 381 pp

online edition

* Kleineberg, A., Marx, Ch., Knobloch, E., Lelgemann, D.: Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios`"Atlas der Oikumene". WBG 2010. . * Porizka, Lubomir; Hojda, Zdenek; and Pesek, Jirí. ''The Palaces of Prague.'' (1995). 216 pp. * Sayer, Derek. "The Language of Nationality and the Nationality of Language: Prague 1780–1920." ''Past & Present'' 1996 (153): 164–210. * Sayer, Derek. ''Prague, Capital of the Twentieth Century: A Surrealist History'' (Princeton University Press; 2013) 595 pages; a study of the city as a crossroads for modernity. * Spector, Scott. ''Prague Territories: National Conflict and Cultural Innovation in Kafka's Fin de Siècle.'' (2000). 331 pp

online edition

* Svácha, Rostislav. ''The Architecture of New Prague, 1895–1945.'' (1995). 573 pp. * Wittlich, Peter. ''Prague: Fin de Siècle.'' (1992). 280 pp. * Wilson, Paul. ''Prague: A Traveler's Literary Companion'' (1995) * ''Prague'' Top 10 (2011

Prague Top 10

See also

*History of the Czech Lands

The history of the Czech lands – an area roughly corresponding to the present-day Czech Republic – starts approximately 800,000 years BCE. A simple chopper from that age was discovered at the Red Hill ( cz, Červený kopec) archeological sit ...

* Famous people connected with Prague

*List of rulers of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings beforehand, first gaining the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman E ...

* Churches in Prague

References

Bibliography

Chittom, Lynn-nore. "Prague, Czech Republic." ''Salem Press Encyclopedia'' (2015): ''Research Starters''. Web. 26 Oct. 2015. Kieval, Hillel J. "Jewish Prague, Christian Prague, And The Castle In The City's 'Golden Age'." ''Jewish Studies Quarterly'' 18.2 (2011): 202–215. "Prague." ''Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia'' (2014): 1p. 1. ''Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia''. Logan, Webb. "Prague: The Czech Republic's 'Dear Little Mother'." ''World Literature Today'' 2014: 5.External links

myczechrepublic, History of Prague

conference-consult, History of Prague

{{Authority control Populated places established in the 9th century