The rule of the

Jagiellonian dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty (, pl, dynastia jagiellońska), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty ( pl, dynastia Jagiellonów), the House of Jagiellon ( pl, Dom Jagiellonów), or simply the Jagiellons ( pl, Jagiellonowie), was the name assumed by a cad ...

in Poland between 1386 and 1572 spans the

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

and the

Early Modern Period in European history. The

Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło) founded the dynasty; his marriage to Queen

Jadwiga of Poland

Jadwiga (; 1373 or 137417 July 1399), also known as Hedwig ( hu, Hedvig), was the first woman to be crowned as monarch of the Kingdom of Poland. She reigned from 16 October 1384 until her death. She was the youngest daughter of Louis the Grea ...

in 1386 strengthened an ongoing

Polish–Lithuanian union Polish–Lithuanian can refer to:

* Polish–Lithuanian union (1385–1569)

* Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

* Polish-Lithuanian identity as used to describe groups, families, or individuals with histories in the Polish–Lithuanian ...

. The partnership brought vast territories controlled by the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was Partitions of Poland, partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire, Habsburg Empire of ...

into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for both the

Polish and

Lithuanian people

Lithuanians ( lt, lietuviai) are a Baltic ethnic group. They are native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,378,118 people. Another million or two make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the United States, Unite ...

, who coexisted and cooperated in one of the largest

political entities in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

for the next four centuries.

In the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

region, Poland engaged in ongoing conflict with the

Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

. The struggles led to a major battle, the

Battle of Grunwald

The Battle of Grunwald, Battle of Žalgiris or First Battle of Tannenberg was fought on 15 July 1410 during the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War. The alliance of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, led respec ...

of 1410, but there was also the milestone

Peace of Thorn of 1466 under King

Casimir IV Jagiellon

Casimir IV (in full Casimir IV Andrew Jagiellon; pl, Kazimierz IV Andrzej Jagiellończyk ; Lithuanian: ; 30 November 1427 – 7 June 1492) was Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1440 and King of Poland from 1447, until his death. He was one of the m ...

; the treaty defined the basis of the future

Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

. In the south, Poland confronted the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

and the

Crimean Tatars, and in the east Poles helped Lithuania fight the

Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

. Poland's and Lithuania's territorial expansion included the far north region of

Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

.

In the Jagiellonian period,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

developed as a

feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

state with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant

landed nobility Landed nobility or landed aristocracy is a category of nobility in the history of various countries, for which landownership was part of their noble privileges. Their character depends on the country.

*The notion of landed gentry in the United Kin ...

. The ''

Nihil novi

''Nihil novi nisi commune consensu'' ("Nothing new without the Consent of the governed, common consent") is the original Latin title of a 1505 Statute, act or constitution adopted by the Poland, Polish ''Sejm of the Kingdom of Poland, Sejm'' (parl ...

'' act adopted by the Polish

Sejm in 1505 transferred most of the

legislative power in the state from the

monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

to the Sejm. This event marked the beginning of the system known as the "

Golden Liberty

Golden Liberty ( la, Aurea Libertas; pl, Złota Wolność, lt, Auksinė laisvė), sometimes referred to as Golden Freedoms, Nobles' Democracy or Nobles' Commonwealth ( pl, Rzeczpospolita Szlachecka or ''Złota wolność szlachecka'') was a pol ...

", when the "free and equal" members of the

Polish nobility

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in ...

ruled the state

and

elected the monarch.

The 16th century saw

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

movements deeply influencing Polish

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

, resulting in unique policies of

religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

for the Europe of that time. The European

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

as fostered by the last Jagiellonian Kings

Sigismund I the Old

Sigismund I the Old ( pl, Zygmunt I Stary, lt, Žygimantas II Senasis; 1 January 1467 – 1 April 1548) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until his death in 1548. Sigismund I was a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the ...

() and

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus ( pl, Zygmunt II August, lt, Žygimantas Augustas; 1 August 1520 – 7 July 1572) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548. He was the first ruler ...

() resulted in an immense

cultural flowering.

Late Middle Ages (14th–15th century)

Jagiellonian monarchy

In 1385, the

Union of Krewo was signed between Queen

Jadwiga of Poland

Jadwiga (; 1373 or 137417 July 1399), also known as Hedwig ( hu, Hedvig), was the first woman to be crowned as monarch of the Kingdom of Poland. She reigned from 16 October 1384 until her death. She was the youngest daughter of Louis the Grea ...

and

Jogaila, the

Grand Duke of Lithuania

The monarchy of Lithuania concerned the monarchical head of state of Lithuania, which was established as an absolute and hereditary monarchy. Throughout Lithuania's history there were three ducal dynasties that managed to stay in power— Ho ...

, the ruler of the last

pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

state in Europe. The act arranged for Jogaila's

baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

and the couple's marriage, which established the beginning of the

Polish–Lithuanian union Polish–Lithuanian can refer to:

* Polish–Lithuanian union (1385–1569)

* Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

* Polish-Lithuanian identity as used to describe groups, families, or individuals with histories in the Polish–Lithuanian ...

. After Jogaila's baptism, he was known in Poland by his baptismal name Władysław and the Polish version of his Lithuanian name, Jagiełło. The union strengthened both nations in their shared opposition to the

Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

and the growing threat of the

Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

.

Vast expanses of

Rus' lands, including the

Dnieper River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

basin and territories extending south to the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

, were at that time under Lithuanian control. In order to gain control of these vast holdings, Lithuanians and Ruthenians had fought the

Battle of Blue Waters

The Battle of Blue Waters ( lt, Mūšis prie Mėlynųjų Vandenų, be, Бітва на Сініх Водах, uk, Битва на Синіх Водах) was a battle fought at some time in autumn 1362 or 1363 on the banks of the Syniukha river, ...

in 1362 or 1363 against the invading

Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

and had taken advantage of the power vacuum to the south and east that resulted from the

Mongol destruction of

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

. The population of the Grand Duchy's enlarged territory was accordingly heavily

Ruthenia

Ruthenia or , uk, Рутенія, translit=Rutenia or uk, Русь, translit=Rus, label=none, pl, Ruś, be, Рутэнія, Русь, russian: Рутения, Русь is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms ...

n and

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

. The territorial expansion led to a confrontation between Lithuania and the Grand Duchy of Moscow, which found itself emerging from the

Tatar

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different rule and itself in a process of expansion. Uniquely in Europe, the union connected two states geographically located on the opposite sides of the great civilizational divide between the

Western Christian

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholic ...

or

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

world, and the

Eastern Christian or

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

world.

The intention of the union was to create a common state under Władysław Jagiełło, but the ruling oligarchy of Poland learned that their goal of incorporating Lithuania into Poland was unrealistic. Territorial disputes led to warfare between Poland and Lithuania or Lithuanian factions; the Lithuanians at times even found it expedient to conspire with the Teutonic Knights against the Poles. Geographic consequences of the

dynastic union

A dynastic union is a type of union with only two different states that are governed under the same dynasty, with their boundaries, their laws, and their interests remaining distinct from each other.

Historical examples

Union of Kingdom of Arag ...

and the preferences of the

Jagiellonian kings instead created a process of orientating Polish territorial priorities to the east.

Between 1386 and 1572, the Polish–Lithuanian union was ruled by a succession of constitutional monarchs of the

Jagiellonian dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty (, pl, dynastia jagiellońska), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty ( pl, dynastia Jagiellonów), the House of Jagiellon ( pl, Dom Jagiellonów), or simply the Jagiellons ( pl, Jagiellonowie), was the name assumed by a cad ...

. The political influence of the Jagiellonian kings gradually diminished during this period, while the landed nobility took over an ever-increasing role in central government and national affairs. The royal dynasty, however, had a stabilizing effect on Poland's politics. The Jagiellonian Era is often regarded as a period of maximum political power, great prosperity, and in its later stage, a

Golden Age of Polish culture.

Social and economic developments

The feudal rent system prevalent in the 13th and 14th centuries, under which each

estate had well defined rights and obligations, degenerated around the 15th century as the nobility tightened their control over manufacturing, trade and other economic activities. This created many directly owned agricultural enterprises known as

folwarks in which feudal rent payments were replaced with forced labor on the lord's land. This limited the rights of cities and forced most of the

peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

s into

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

. Such practices were increasingly sanctioned by the law. For example, the

Piotrków Privilege of 1496, granted by King

John I Albert

John I Albert ( pl, Jan I Olbracht; 27 December 1459 – 17 June 1501) was King of Poland from 1492 until his death in 1501 and Duke of Głogów (Glogau) from 1491 to 1498. He was the fourth Polish sovereign from the Jagiellonian dynasty, the s ...

, banned rural land purchases by townspeople and severely limited the ability of peasant farmers to leave their villages. Polish towns, lacking national representation protecting their class interests, preserved some degree of self-government (city councils and jury courts), and the trades were able to organize and form

guilds

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

. The nobility soon excused themselves from their principal duty: mandatory military service in case of war (

pospolite ruszenie

''Pospolite ruszenie'' (, lit. ''mass mobilization''; "Noble Host", lat, motio belli, the French term ''levée en masse'' is also used) is a name for the mobilisation of armed forces during the period of the Kingdom of Poland and the Polish–Li ...

). The division of the nobility into two main layers was institutionalized, but never legally formalized, in the ''

Nihil novi

''Nihil novi nisi commune consensu'' ("Nothing new without the Consent of the governed, common consent") is the original Latin title of a 1505 Statute, act or constitution adopted by the Poland, Polish ''Sejm of the Kingdom of Poland, Sejm'' (parl ...

'' "constitution" of 1505, which required the king to consult the

general sejm

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

, that is the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, as well as the lower chamber of (regional) deputies, the Sejm proper, before enacting any changes. The masses of ordinary nobles

szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in ...

competed or tried to compete against the uppermost rank of their class, the

magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s, for the duration of Poland's independent existence.

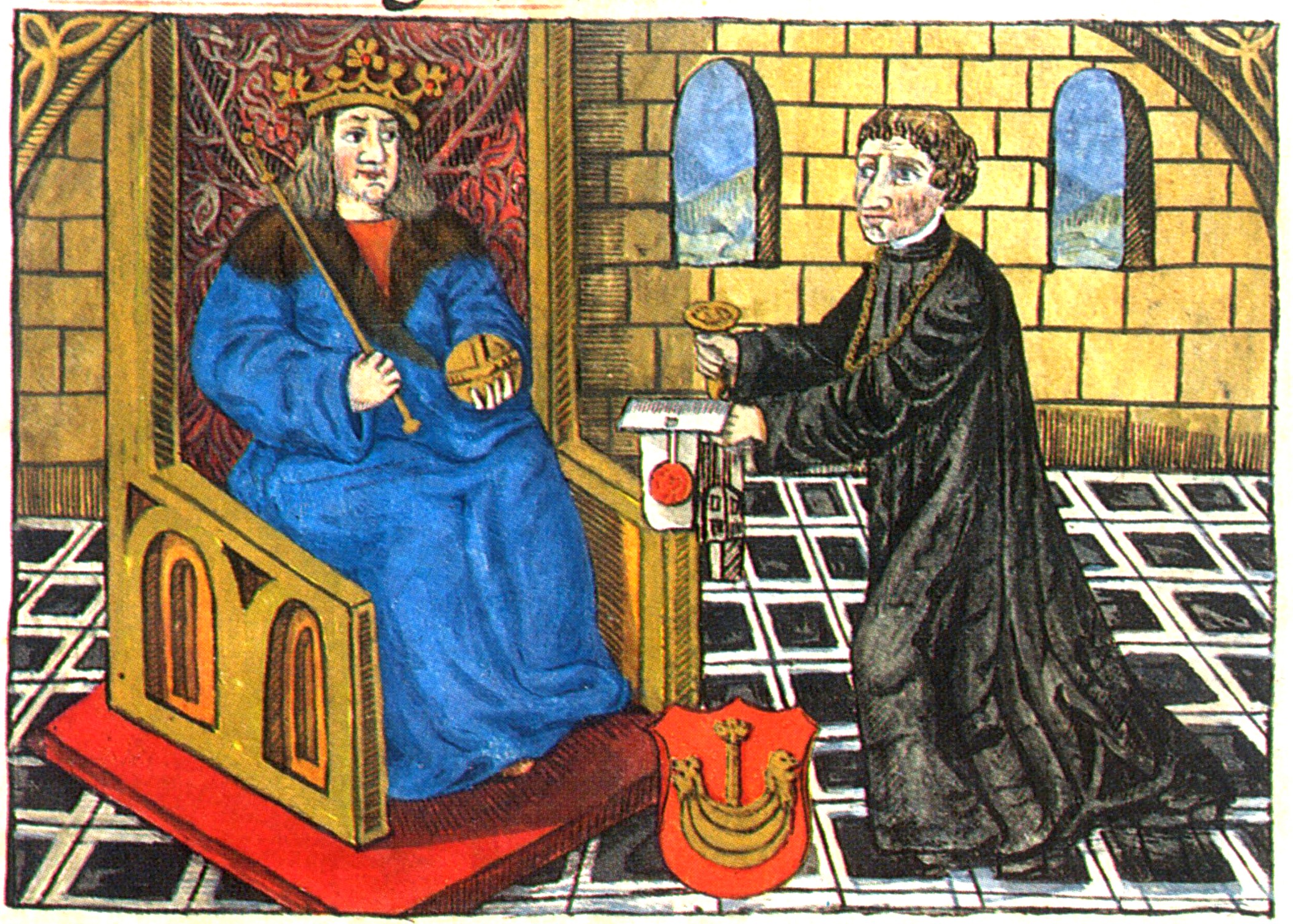

Poland and Lithuania in personal union under Jagiełło

The first king of the new dynasty was Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, who was known as

Władysław II Jagiełło

Jogaila (; 1 June 1434), later Władysław II Jagiełło ()He is known under a number of names: lt, Jogaila Algirdaitis; pl, Władysław II Jagiełło; be, Jahajła (Ягайла). See also: Names and titles of Władysław II Jagiełło. ...

in Poland. He was elected king of Poland in 1386 after his marriage to

Jadwiga of Anjou, the

King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16th ...

in her own right, and his conversion to

Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. The

Christianization of Lithuania

The Christianization of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos krikštas) occurred in 1387, initiated by King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Władysław II Jagiełło and his cousin Vytautas the Great. It signified the official adoption of Christianity b ...

in the

Latin Rite

Latin liturgical rites, or Western liturgical rites, are Catholic rites of public worship employed by the Latin Church, the largest particular church '' sui iuris'' of the Catholic Church, that originated in Europe where the Latin language onc ...

followed. Jogaila's rivalry in Lithuania with his cousin

Vytautas the Great

Vytautas (c. 135027 October 1430), also known as Vytautas the Great ( Lithuanian: ', be, Вітаўт, ''Vitaŭt'', pl, Witold Kiejstutowicz, ''Witold Aleksander'' or ''Witold Wielki'' Ruthenian: ''Vitovt'', Latin: ''Alexander Vitoldus'', O ...

, who was opposed to Lithuania's domination by Poland, was settled in 1392 in the

Ostrów Agreement

The Ostrów or Astrava Agreement ( lt, Astravos sutartis, be, Востраўскае пагадненне, pl, Ugoda w Ostrowie) was a treaty between Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło), King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and his cous ...

and in 1401 in the

Union of Vilnius and Radom

The Pact of Vilnius and Radom ( pl, Unia wileńsko-radomska, lt, Vilniaus-Radomo sutartis) was a set of three acts passed in Vilnius, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and confirmed by the Crown Council in Radom, Kingdom of Poland in 1401. The union ame ...

: Vytautas became the Grand Duke of Lithuania for life under Jogaila's nominal supremacy. The agreement made possible a close cooperation between the two nations necessary to succeed in struggles with the Teutonic Order. The

Union of Horodło of 1413 defined the relationship further and granted privileges to the

Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

(as opposed to

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

) segment of the Lithuanian nobility.

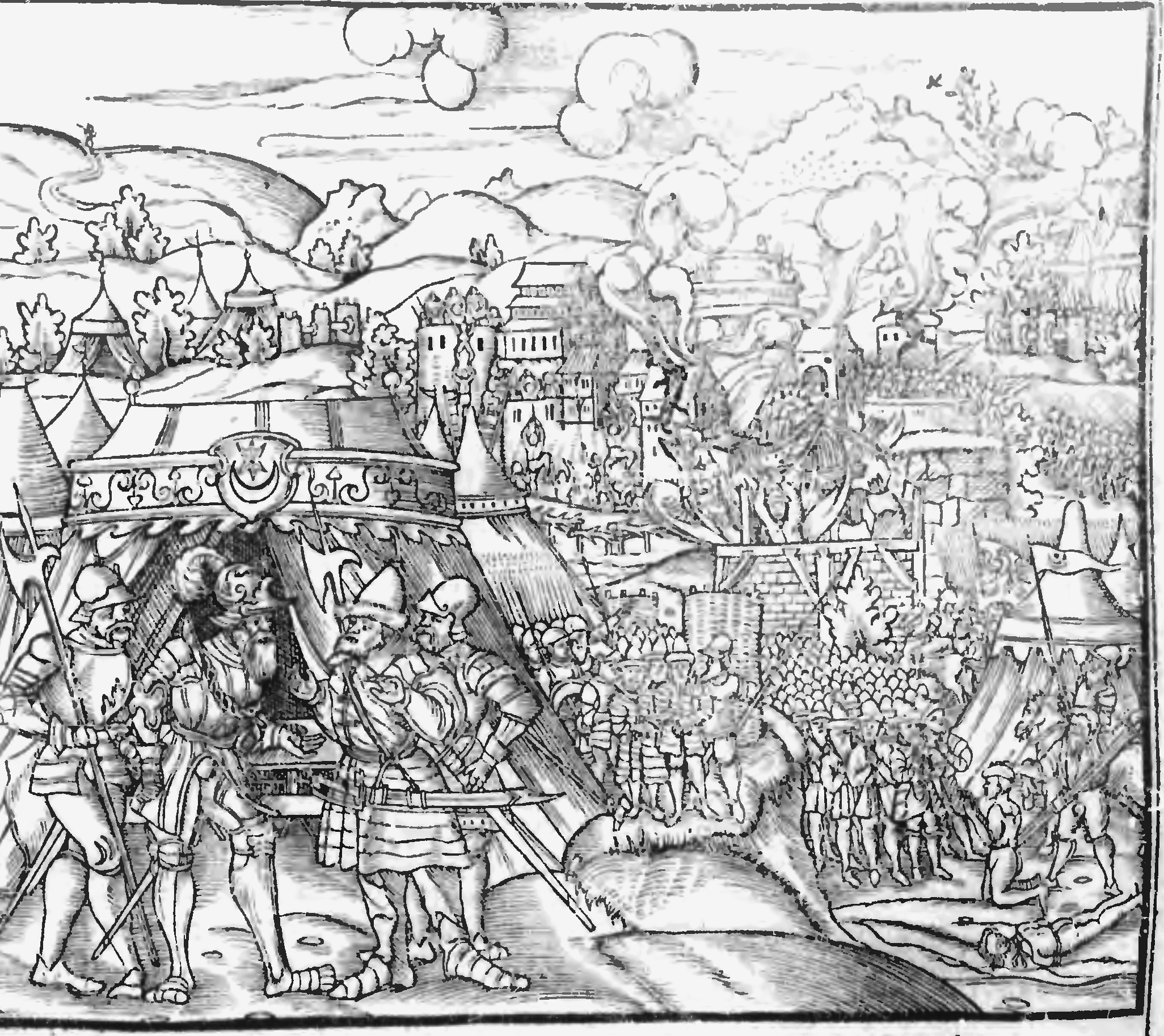

Struggle with the Teutonic Knights

The

Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War of 1409–1411, precipitated by the

Samogitian uprisings in Lithuanian territories controlled by the

State of the Teutonic Order

The State of the Teutonic Order (german: Staat des Deutschen Ordens, ; la, Civitas Ordinis Theutonici; lt, Vokiečių ordino valstybė; pl, Państwo zakonu krzyżackiego), also called () or (), was a medieval Crusader state, located in Cent ...

, culminated in the

Battle of Grunwald

The Battle of Grunwald, Battle of Žalgiris or First Battle of Tannenberg was fought on 15 July 1410 during the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War. The alliance of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, led respec ...

(Tannenberg), in which the combined forces of the Polish and Lithuanian-Rus' armies completely defeated the

Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

. The offensive that followed lost its impact with the ineffective siege of

Malbork

Malbork; ;

* la, Mariaeburgum, ''Mariae castrum'', ''Marianopolis'', ''Civitas Beatae Virginis''

* Kashubian: ''Malbórg''

* Old Prussian: ''Algemin'' is a town in the Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland. It is the seat of Malbork County and has ...

(Marienburg). The failure to take the fortress and eliminate the Teutonic (later

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n) state had dire historic consequences for Poland in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. The

Peace of Thorn of 1411 gave Poland and Lithuania rather modest territorial adjustments, including Samogitia. Afterwards, there were more military campaigns and peace deals that did not hold. One unresolved arbitration took place at the

Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the r ...

. In 1415,

Paulus Vladimiri,

rector of the

Kraków Academy, presented his ''Treatise on the Power of the Pope and the Emperor in respect to Infidels'' at the council, in which he advocated tolerance, criticized the violent conversion methods of the Teutonic Knights, and postulated that pagans have the right to peaceful coexistence with Christians and political independence. This stage of the Polish-Lithuanian conflict with the Teutonic Order ended with the

Treaty of Melno

The Treaty of Melno ( lt, Melno taika; pl, Pokój melneński) or Treaty of Lake Melno (german: Friede von Melnosee) was a peace treaty ending the Gollub War. It was signed on 27 September 1422, between the Teutonic Knights and an alliance of th ...

in 1422. The

Polish-Teutonic War of 1431-35 (see

Battle of Wiłkomierz

The Battle of Wiłkomierz (see other names) took place on September 1, 1435, near Ukmergė in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. With the help of military units from the Kingdom of Poland, the forces of Grand Duke Sigismund Kęstutaitis soundly defea ...

) was concluded with the

Peace of Brześć Kujawski

Peace of Brześć Kujawski was a peace treaty signed on December 31, 1435 in Brześć Kujawski that ended the Polish–Teutonic War (1431–1435). The treaty was signed in the aftermath of the Livonian Order's defeat at the hands of the allied Po ...

in 1435.

The Hussite movement and the Polish–Hungarian union

During the

Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, Eur ...

of 1420–1434, Jagiełło, Vytautas and

Sigismund Korybut

Sigismund Korybut ( lt, Žygimantas Kaributaitis; be, Жыгімонт Карыбутавіч; pl, Zygmunt Korybutowicz; cz, Zikmund Korybutovič; uk, Жиґимонт Корибутович or Сигізмунд Корибутович, 1395 � ...

were involved in political and military intrigues with respect to the

Czech crown, which was offered by the

Hussite

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

s to Jagiełło in 1420. Bishop

Zbigniew Oleśnicki became known as the leading opponent of a union with the Hussite Czech state.

The Jagiellonian dynasty was not entitled to automatic hereditary succession, rather each new king had to be approved by nobility consensus. Władysław Jagiełło had two sons late in life from his last wife

Sophia of Halshany

Sophia (Sonka) of Halshany or Sophia Holshanska ( be, Соф'я Гальшанская, translit=Sofja Halšanskaja; lt, Sofija Alšėniškė; pl, Zofia Holszańska; – September 21, 1461 in Kraków) was a princess of Halshany and was Queen ...

. In 1430, the nobility agreed to the succession of the future

Władysław III only after the king consented to a series of concessions. In 1434, the old monarch died and his minor son Władysław was crowned; the Royal Council led by Bishop Oleśnicki undertook the regency duties.

In 1438, the Czech anti-

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

opposition, mainly Hussite factions, offered the Czech crown to Jagiełło's younger son

Casimir

Casimir is classically an English, French and Latin form of the Polish name Kazimierz. Feminine forms are Casimira and Kazimiera. It means "proclaimer (from ''kazać'' to preach) of peace (''mir'')."

List of variations

*Belarusian: Казі ...

. The idea, accepted in Poland over Oleśnicki's objections, resulted in two unsuccessful Polish military expeditions to

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

.

After Vytautas' death in 1430, Lithuania became embroiled in internal wars and conflicts with Poland. Casimir, sent as a boy by King Władysław on a mission there in 1440, was surprisingly proclaimed by the Lithuanians as their Grand Duke, and he remained in Lithuania.

Oleśnicki gained the upper hand again and pursued his long-term objective of Poland's union with Hungary. At that time, the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

embarked on a fresh round of European conquests and threatened Hungary, which needed the assistance of the powerful Polish–Lithuanian ally. In 1440, Władysław III assumed the Hungarian throne. Influenced by

Julian Cesarini, the young king led the Hungarian army against the Ottomans in 1443 and again in 1444. Like Cesarini, Władysław III was killed at the

Battle of Varna.

Beginning near the end of Jagiełło's life, Poland was governed in practice by an oligarchy of magnates led by Bishop Oleśnicki. The rule of the dignitaries was actively opposed by various groups of ''

szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in ...

''. Their leader

Spytek of Melsztyn was killed at the

Battle of Grotniki in 1439, which allowed Oleśnicki to purge Poland of the remaining Hussite sympathizers and pursue his other objectives without significant opposition.

The accession of Casimir IV Jagiellon

In 1445,

Casimir

Casimir is classically an English, French and Latin form of the Polish name Kazimierz. Feminine forms are Casimira and Kazimiera. It means "proclaimer (from ''kazać'' to preach) of peace (''mir'')."

List of variations

*Belarusian: Казі ...

, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, was asked to assume the Polish throne vacated upon the death of his brother Władysław. Casimir was a tough negotiator and did not accept the Polish nobility's conditions for his election. He finally arrived in Poland and was crowned in 1447 on his own terms. His assumption of the Crown of Poland freed Casimir from the control that the Lithuanian oligarchy had imposed on him; in the

Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

Privilege of 1447, he declared the

Lithuanian nobility

The Lithuanian nobility or szlachta ( Lithuanian: ''bajorija, šlėkta'') was historically a legally privileged hereditary elite class in the Kingdom of Lithuania and Grand Duchy of Lithuania (including during period of foreign rule 1795–191 ...

to have equal rights with Polish ''szlachta''. In time, Casimir was able to wrest power from

Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**'' Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, t ...

Oleśnicki and his group. He replaced their influence with a power base built on the younger middle nobility. Casimir was able to resolve a conflict with the pope and the local Church hierarchy over the right to fill vacant bishop positions in his favor.

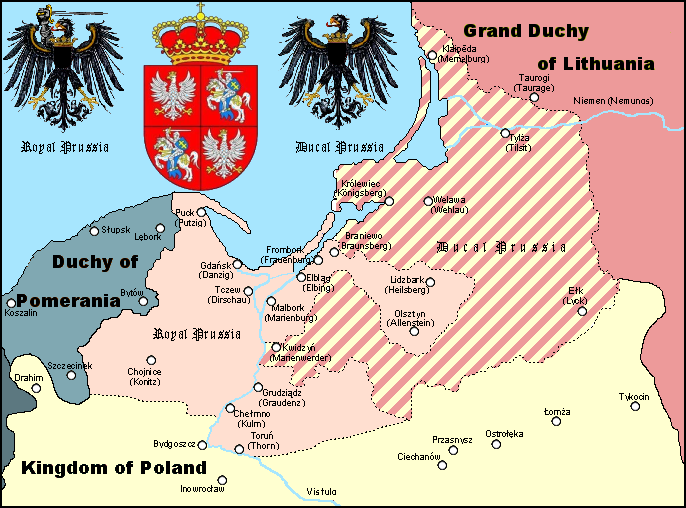

War with the Teutonic Order and its resolution

In 1454, the

Prussian Confederation

The Prussian Confederation (german: Preußischer Bund, pl, Związek Pruski) was an organization formed on 21 February 1440 at Kwidzyn (then officially ''Marienwerder'') by a group of 53 nobles and clergy and 19 cities in Prussia, to oppose the ...

, an alliance of Prussian cities and nobility opposed to the increasingly oppressive rule of the Teutonic Knights, asked King Casimir to take over Prussia and initiated an armed uprising against the Knights. Casimir declared a war on the Order and the formal incorporation of Prussia into the Polish Crown; those events led to the

Thirteen Years' War of 1454–66. The mobilization of the Polish forces (the

pospolite ruszenie

''Pospolite ruszenie'' (, lit. ''mass mobilization''; "Noble Host", lat, motio belli, the French term ''levée en masse'' is also used) is a name for the mobilisation of armed forces during the period of the Kingdom of Poland and the Polish–Li ...

) was weak at first, since the

szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in ...

would not cooperate without concessions from Casimir that were formalized in the

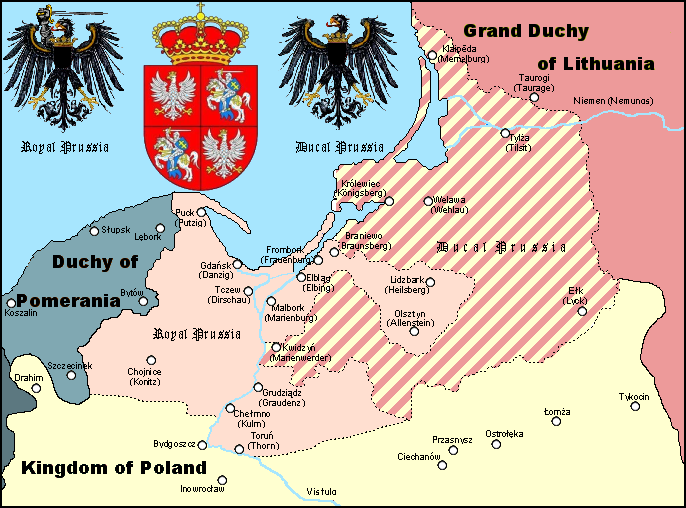

Statutes of Nieszawa promulgated in 1454. This prevented a takeover of all of Prussia, but in the

Second Peace of Thorn

The Peace of Thorn or Toruń of 1466, also known as the Second Peace of Thorn or Toruń ( pl, drugi pokój toruński; german: Zweiter Friede von Thorn), was a peace treaty signed in the Hanseatic city of Thorn (Toruń) on 19 October 1466 betwe ...

in 1466, the Knights had to surrender the western half of their territory to the

Polish Crown (the areas known afterwards as

Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia ( pl, Prusy Królewskie; german: Königlich-Preußen or , csb, Królewsczé Prësë) or Polish PrussiaAnton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. ''A New System of Geography'', London 1762p. 588/ref> (Polish: ; German: ) was a ...

, a semi-autonomous entity), and to accept Polish-Lithuanian

suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

over the remainder (the later

Ducal Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establishe ...

). Poland regained

Pomerelia, with its access to the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, as well as

Warmia

Warmia ( pl, Warmia; Latin: ''Varmia'', ''Warmia''; ; Warmian: ''Warńija''; lt, Varmė; Old Prussian: ''Wārmi'') is both a historical and an ethnographic region in northern Poland, forming part of historical Prussia. Its historic capital ...

. In addition to land warfare, naval battles took place in which ships provided by the City of

Danzig (Gdańsk) successfully fought

Danish and Teutonic fleets.

Other territories recovered by the Polish Crown in the 15th-century include the

Duchy of Oświęcim and

Duchy of Zator on

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

's border with

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

, and there was notable progress regarding the incorporation of the Piast

Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

n duchies into the Crown.

Turkish and Tatar wars

The influence of the

Jagiellonian dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty (, pl, dynastia jagiellońska), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty ( pl, dynastia Jagiellonów), the House of Jagiellon ( pl, Dom Jagiellonów), or simply the Jagiellons ( pl, Jagiellonowie), was the name assumed by a cad ...

in

Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

rose during the 15th century. In 1471, Casimir's son

Władysław became king of Bohemia, and in 1490, also of Hungary.

The southern and eastern outskirts of Poland and Lithuania became threatened by

Turkish invasions beginning in the late 15th century.

Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

's involvement with Poland goes back to 1387, when

Petru I,

Hospodar of Moldavia sought protection against the Hungarians by paying

homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to King Władysław II Jagiełło in

Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

. This move gave Poland access to

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

ports.

In 1485, King Casimir undertook an expedition into Moldavia after its seaports were overtaken by the

Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

. The Turkish-controlled

Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace ...

raided the eastern territories in 1482 and 1487 until they were confronted by King

John Albert, Casimir's son and successor.

Poland was attacked in 1487–1491 by remnants of the

Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragmen ...

that invaded Poland as far as

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

before being beaten at

Zaslavl.

In 1497, King John Albert made an attempt to resolve the Turkish problem militarily, but his efforts were unsuccessful; he was unable to secure effective participation in the war by his brothers, King

Vladislas (Władysław) II of Bohemia and Hungary and

Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, and he also faced resistance on the part of

Stephen the Great, the ruler of Moldavia. More destructive

Tatar raids instigated by the Ottoman Empire took place in 1498, 1499 and 1500.

Diplomatic peace efforts initiated by John Albert were finalized after the king's death in 1503. They resulted in a territorial compromise and an unstable truce.

Invasions into Poland and Lithuania from the

Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the long ...

took place in 1502 and 1506 during the reign of King

Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

. In 1506, the Tatars were defeated at the

Battle of Kletsk by

Michael Glinski

Michael Lvovich Glinsky ( lt, Mykolas Glinskis, russian: Михаил Львович Глинский, pl, Michał Gliński; 1460s – 24 September 1534) was a noble from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania of distant Tatar extraction, who was also a t ...

.

Moscow's threat to Lithuania; accession of Sigismund I

Lithuania was increasingly threatened by the growing power of the

Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

in the 15th and 16th centuries. Moscow indeed took over many of Lithuania's eastern possessions in

military campaigns of 1471, 1492, and 1500. Grand Duke

Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

of Lithuania was elected King of Poland in 1501, after the death of John Albert. In 1506, he was succeeded by

Sigismund I the Old

Sigismund I the Old ( pl, Zygmunt I Stary, lt, Žygimantas II Senasis; 1 January 1467 – 1 April 1548) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until his death in 1548. Sigismund I was a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the ...

(''Zygmunt I Stary'') in both Poland and Lithuania as political realities were drawing the two states closer together. Prior to his accession to the Polish throne, Sigismund had been a Duke of

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

by the authority of his brother Vladislas II of

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, but like other Jagiellon rulers before him, he did not pursue the claim of the Polish Crown to Silesia.

Culture in the Late Middle Ages

The

culture of the 15th century Poland can be described as retaining typical medieval characteristics. Nonetheless, the crafts and industries in existence already in the preceding centuries became more highly developed under favorable social and economic conditions, and their products were much more widely disseminated. Paper production was one of the new industries that appeared, and printing developed during the last quarter of the century. In 1473,

Kasper Straube produced the first

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

print in

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

, whereas Kasper Elyan printed Polish texts for the first time in

Wrocław (Breslau) in 1475. The world's oldest prints in

Cyrillic script

The Cyrillic script ( ), Slavonic script or the Slavic script, is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking c ...

, namely religious texts in

Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and using it in translating the Bible and othe ...

, appeared after 1490 from the press of

Schweipolt Fiol in Krakow.

Luxury items were in high demand among the increasingly prosperous nobility, and to a lesser degree among the wealthy town merchants. Brick and stone residential buildings became common, but only in cities. The mature

Gothic style

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

was represented not only in architecture, but also in sacral wooden sculpture. The

Altar of Veit Stoss

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paganism ...

in

St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków is one of the most magnificent art works of its kind in Europe.

Kraków University

The Jagiellonian University ( Polish: ''Uniwersytet Jagielloński'', UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and the 13th oldest university ...

, which stopped functioning after the death of

Casimir the Great

Casimir III the Great ( pl, Kazimierz III Wielki; 30 April 1310 – 5 November 1370) reigned as the King of Poland from 1333 to 1370. He also later became King of Ruthenia in 1340, and fought to retain the title in the Galicia-Volhynia Wars. He w ...

, was renewed and rejuvenated around 1400. Augmented by a

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

department, the "academy" was supported and protected by Queen

Jadwiga

Jadwiga (; diminutives: ''Jadzia'' , ''Iga'') is a Polish feminine given name. It originated from the old German feminine given name ''Hedwig'' (variants of which include ''Hedwiga''), which is compounded from ''hadu'', "battle", and ''wig'', "figh ...

and the Jagiellonian dynasty members, which is reflected in its present name: the Jagiellonian University. Europe's oldest department of mathematics and astronomy was established in 1405. Among the university's prominent scholars were

Stanisław of Skarbimierz

Stanisław of Skarbimierz (1360–1431; Latinised as ''Stanislaus de Scarbimiria'') was the first rector of the University of Krakow following its restoration in 1399. He was the author of ''Sermones sapientiales'' ( pl, Kazania sapiencjalne), com ...

,

Paulus Vladimiri and

Albert of Brudzewo,

Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

' teacher.

John of Ludzisko and Archbishop

Gregory of Sanok, the precursors of Polish

humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

, were professors at the university. Gregory's court was the site of an early literary society at

Lwów (Lviv) after he became the archbishop there. Scholarly thought elsewhere was represented by Jan Ostroróg, a political publicist and reformist, and

Jan Długosz

Jan Długosz (; 1 December 1415 – 19 May 1480), also known in Latin as Johannes Longinus, was a Polish priest, chronicler, diplomat, soldier, and secretary to Bishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki of Kraków. He is considered Poland's first histo ...

, a historian, whose ''Annals'' is the largest history work of his time in Europe and a fundamental source for history of medieval Poland. Distinguished and influential foreign humanists were also active in Poland.

Filippo Buonaccorsi, a poet and diplomat, arrived from Italy in 1468 and stayed in Poland until his death in 1496. Known as Kallimach, he prepared biographies of Gregory of Sanok, Zbigniew Oleśnicki, and very likely Jan Długosz, besides establishing another literary society in Kraków. He tutored and mentored the sons of Casimir IV and postulated unrestrained royal power. In Kraków, the

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

humanist

Conrad Celtes

Conrad Celtes (german: Konrad Celtes; la, Conradus Celtis (Protucius); 1 February 1459 – 4 February 1508) was a German Renaissance humanist scholar and poet of the German Renaissance born in Franconia (nowadays part of Bavaria). He led the ...

organized the humanist literary and scholarly association ''

Sodalitas Litterarum Vistulana Sodalitas Litterarum Vistulana ("Literary Sodality of the Vistula") was an international academic society modelled after the Roman Academy, founded around 1488 in Cracow by Conrad Celtes, a German humanist scholar who in other areas founded seve ...

'', the first in this part of Europe.

Early Modern Era (16th century)

Agriculture-based economic expansion

The

folwark, a large-scale system of agricultural production based on

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, was a dominant feature on Poland's economic landscape beginning in the late 15th century and for the next 300 years. This dependence on nobility-controlled agriculture in central-eastern Europe diverged from the western part of the continent, where elements of

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

and

industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

were developing to a much greater extent, with the attendant growth of a

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

class and its political influence. The 16th-century agricultural trade

boom

Boom may refer to:

Objects

* Boom (containment), a temporary floating barrier used to contain an oil spill

* Boom (navigational barrier), an obstacle used to control or block marine navigation

* Boom (sailing), a sailboat part

* Boom (windsurfin ...

combined with free or very cheap peasant labor made the folwark economy very profitable.

Mining and metallurgy developed further during the 16th century, and technical progress took place in various commercial applications. Great quantities of exported agricultural and forest products floated down the rivers to be transported through ports and land routes. This resulted in a

positive trade balance for Poland throughout the 16th century. Imports from the West included industrial products, luxury products and fabrics.

[Józef Andrzej Gierowski – ''Historia Polski 1505–1764'' (History of Poland 1505–1764), p. 24-38]

Most of the exported

grain

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit ( caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legum ...

left Poland through

Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

(Danzig), which became the wealthiest, most highly developed, and most autonomous of the Polish cities because of its location at the mouth of the

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

River and access to the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

. It was also by far the largest center for manufacturing. Other towns were negatively affected by Gdańsk's near-monopoly in foreign trade, but profitably participated in transit and export activities. The largest of those were

Kraków (Cracow),

Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

,

Lwów (Lviv), and

Warszawa (Warsaw), and outside of the Crown,

Breslau (Wrocław).

Thorn (Toruń) and

Elbing (Elbląg) were the main cities in

Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia ( pl, Prusy Królewskie; german: Königlich-Preußen or , csb, Królewsczé Prësë) or Polish PrussiaAnton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. ''A New System of Geography'', London 1762p. 588/ref> (Polish: ; German: ) was a ...

after Gdańsk.

Burghers and nobles

During the 16th century, prosperous

patrician families of merchants, bankers, or industrial investors, many of German origin, still conducted large-scale business operations in Europe or lent money to Polish noble interests, including the royal court. Some regions were highly urbanized in comparison to most of the rest of Europe. In

Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest cit ...

and

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

at the end of the 16th century, for example, 30% of the population lived in cities.

256 towns were founded, most in

Red Ruthenia

Red Ruthenia or Red Rus' ( la, Ruthenia Rubra; '; uk, Червона Русь, Chervona Rus'; pl, Ruś Czerwona, Ruś Halicka; russian: Червонная Русь, Chervonnaya Rus'; ro, Rutenia Roșie), is a term used since the Middle Ages fo ...

. The townspeople's upper layer was ethnically multinational and tended to be well-educated. Numerous sons of burghers studied at the

Academy of Kraków and at foreign universities; members of their group are among the finest contributors to the culture of the

Polish Renaissance. Unable to form their own nationwide political class, many blended into the nobility in spite of the legal obstacles.

The nobility (or ''

szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in ...

'') in Poland constituted a greater proportion of the population than in other countries, up to 10%. In principle, they were all equal and politically empowered, but some had no property and were not allowed to hold offices or participate in

sejms or

sejmik

A sejmik (, diminutive of ''sejm'', occasionally translated as a ''dietine''; lt, seimelis) was one of various local parliaments in the history of Poland and history of Lithuania. The first sejmiks were regional assemblies in the Kingdom of ...

s, the legislative bodies. Of the "landed" nobility, some possessed a small patch of land that they tended themselves and lived like peasant families, while the magnates owned dukedom-like networks of estates with several hundred towns and villages and many thousands of subjects. Mixed marriages gave some peasants one of the few possible paths to nobility.

16th-century Poland was officially a "republic of nobles", and the "middle class" of the nobility (individuals at a lower social level than "magnates") formed the leading component during the later Jagiellonian period and afterwards. Nonetheless, members of the magnate families held the highest state and church offices. At that time, the ''szlachta'' in Poland and Lithuania was ethnically diversified and represented several religious denominations. During this period of tolerance, such factors had little bearing on one's economic status or career potential. Jealous of their class privilege ("

freedoms

Political freedom (also known as political autonomy or political agency) is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies.Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?", ''Between Past and F ...

"), the Renaissance ''szlachta'' developed a sense of public service duties, educated their youth, took keen interest in current trends and affairs and traveled widely. The

Golden Age of Polish Culture adopted western

humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

and

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

patterns, and visiting foreigners often remarked on the splendor of their residencies and the conspicuous consumption of wealthy Polish nobles.

Reformation

In a situation analogous with that of other European countries, the progressive internal decay of the

Polish Church created conditions favorable for the dissemination of the

Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

ideas and currents. For example, there was a chasm between the lower clergy and the nobility-based Church hierarchy, which was quite laicized and preoccupied with temporal issues, such as power and wealth, and often corrupt. The middle nobility, which had already been exposed to the

Hussite

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

reformist persuasion, increasingly looked at the Church's many privileges with envy and hostility.

The teachings of

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

were accepted most readily in the regions with strong German connections:

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

,

Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest cit ...

,

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

. In

Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

(Danzig) in 1525 a lower-class

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

social uprising took place and was bloodily subdued by

Sigismund I; after the reckoning he established a representation for the plebeian interests as a segment of the city government.

Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was ...

and the

Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

under

Albrecht Hohenzollern became a strong center of

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

propaganda dissemination affecting all of northern Poland and

Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

. Sigismund quickly reacted against the "religious novelties", issuing his first related edict in 1520, banning any promotion of the Lutheran ideology, or even foreign trips to the Lutheran centers. Such attempted (poorly enforced) prohibitions continued until 1543.

Sigismund's son

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus ( pl, Zygmunt II August, lt, Žygimantas Augustas; 1 August 1520 – 7 July 1572) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548. He was the first ruler ...

(''Zygmunt II August''), a monarch of a much more tolerant attitude, guaranteed the freedom of the Lutheran religion practice in all of

Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia ( pl, Prusy Królewskie; german: Königlich-Preußen or , csb, Królewsczé Prësë) or Polish PrussiaAnton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. ''A New System of Geography'', London 1762p. 588/ref> (Polish: ; German: ) was a ...

by 1559. Besides Lutheranism, which, within the Polish Crown, ultimately found substantial following mainly in the cities of Royal Prussia and western Greater Poland, the teachings of the persecuted

Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

s and

Unitarians, and in Greater Poland the

Czech Brothers, were met, at least among the ''szlachta'', with a more sporadic response.

In Royal Prussia, 41% of the parishes were counted as Lutheran in the second half of the 16th century, but that percentage kept increasing. According to

Kasper Cichocki, who wrote in the early 17th century, only remnants of Catholicism were left there in his time. Lutheranism was strongly dominant in Royal Prussia throughout the 17th century, with the exception of

Warmia

Warmia ( pl, Warmia; Latin: ''Varmia'', ''Warmia''; ; Warmian: ''Warńija''; lt, Varmė; Old Prussian: ''Wārmi'') is both a historical and an ethnographic region in northern Poland, forming part of historical Prussia. Its historic capital ...

(Ermland).

Around 1570, of the at least 700 Protestant congregations in Poland–Lithuania, over 420 were

Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

and over 140 Lutheran, with the latter including 30-40 ethnically Polish. Protestants encompassed approximately ½ of the

magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

class, ¼ of other nobility and townspeople, and 1/20 of the non-Orthodox peasantry. The bulk of the Polish-speaking population had remained Catholic, but the proportion of Catholics became significantly diminished within the upper social ranks.

Calvinism gained many followers in the mid 16th century among both the ''szlachta'' and the magnates, especially in

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

and Lithuania. The Calvinists, who led by

Jan Łaski were working on unification of the Protestant churches, proposed the establishment of a Polish national church, under which all Christian denominations, including

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

(very numerous in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Ukraine), would be united. After 1555 Sigismund II, who accepted their ideas, sent an envoy to the pope, but the papacy rejected the various Calvinist postulates. Łaski and several other Calvinist scholars published in 1563 the

Bible of Brest, a complete Polish

Bible translation from the

original languages, an undertaking financed by

Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Black. After 1563–1565 (the abolishment of state enforcement of

the Church jurisdiction), full religious tolerance became the norm. The Polish

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

emerged from this critical period weakened but not badly damaged (the bulk of the Church property was preserved), which facilitated the later success of

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

.

Among the Calvinists, who also included the lower classes and their leaders, ministers of common background, disagreements soon developed, based on different views in the areas of religious and social doctrines. The official split took place in 1562, when two separate churches were officially established: the mainstream Calvinist and the smaller, more reformist,

Polish Brethren

The Polish Brethren (Polish: ''Bracia Polscy'') were members of the Minor Reformed Church of Poland, a Nontrinitarian Protestant church that existed in Poland from 1565 to 1658. By those on the outside, they were called " Arians" or " Socinians" ( ...

or

Arians. The adherents of the radical wing of the Polish Brethren promoted, often by way of personal example, the ideas of social justice. Many Arians (such as

Piotr of Goniądz

Piotr of Goniądz ( pl, Piotr z Goniądza, ; Latin: Gonesius; c. 1525–1573) was a Polish political and religious writer, thinker and one of the spiritual leaders of the Polish Brethren.

Life

Little is known of his early life. He was born to a p ...

and

Jan Niemojewski

Janusz Jan Niemojewski (1531–1598) was a Polish nobleman, and theologian of the Polish Brethren.Kęstutis Daugirdas, "Die Anfänge des Sozinianismus", Göttingen, 2016, p. 91-94, 180-183

Works

* 1583 – "Odpowiedź na potwarz Wilkowskiego"

* 1 ...

) were pacifists opposed to private property, serfdom, state authority and military service; through communal living some had implemented the ideas of shared usage of the land and other property. A major Polish Brethren congregation and center of activities was established in 1569 in

Raków near

Kielce

Kielce (, yi, קעלץ, Keltz) is a city in southern Poland, and the capital of the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship. In 2021, it had 192,468 inhabitants. The city is in the middle of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains (Holy Cross Mountains), on the ban ...

, and lasted until 1638, when Counter-Reformation had it closed. The notable

Sandomierz Agreement of 1570, an act of compromise and cooperation among several Polish Protestant denominations, excluded the Arians, whose more moderate, larger faction toward the end of the century gained the upper hand within the movement.

The act of the

Warsaw Confederation

The Warsaw Confederation, signed on 28 January 1573 by the Polish national assembly (''sejm konwokacyjny'') in Warsaw, was one of the first European acts granting religious freedoms. It was an important development in the history of Poland and o ...

, which took place during the

convocation sejm of 1573, provided guarantees, at least for the nobility, of religious freedom and peace. It gave the Protestant denominations, including the Polish Brethren, formal rights for many decades to come. Uniquely in 16th-century Europe, it turned the Commonwealth, in the words of Cardinal

Stanislaus Hosius

Stanislaus Hosius ( pl, Stanisław Hozjusz; 5 May 1504 – 5 August 1579) was a Polish Roman Catholic cardinal. From 1551 he was the Prince-Bishop of the Bishopric of Warmia in Royal Prussia and from 1558 he served as the papal legate to the H ...

, a Catholic reformer, into a "safe haven for heretics".

Culture of Polish Renaissance

Golden Age of Polish culture

The Polish "Golden Age", the period of the reigns of Sigismund I and Sigismund II, the last two Jagiellonian kings, or more generally the 16th century, is most often identified with the rise of the culture of

Polish Renaissance. The cultural flowering had its material base in the prosperity of the elites, both the landed nobility and urban

patriciate at such centers as

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

and

Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

.

As was the case with other European nations, the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

inspiration came in the first place from

Italy