History of Omaha on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

"Omaha Mall, Scene Of Mass Killing, Reopens"

''

Historic photos

*

'

"Douglas County Historical Society"

*

' by former mayor Alfred Sorenson.

"Early Omaha: Gateway to the West"

by the Omaha Public Library. * of the Nebraska State Historical Society.

Historic Florence

Florence Futures Foundation website.

Mardos Memorial Library

featuring Douglas County history.

at Omaha South High School from th

website. * website.

Brief History of Omaha, Nebraska

WPA Omaha, Nebraska City Guide Project

by the

North Omaha History

website.

''Reconnaissance Survey of Downtown and Columbus Park Omaha''

- Nebraska State Historical Society, August 2011 {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Omaha, Nebraska

The history of

On July 21, 1804, the

On July 21, 1804, the

"History at a glance"

, Douglas County Historical Society. Retrieved 2/2/08. The expedition stopped at a point about 20 miles (30 km) north of present-day Omaha, at which point they first met with the Otoe. They had a council meeting with members of the tribal leadership on the west side of the Missouri River. The first recorded instance of a

In 1853

In 1853

The small city suffered greatly in the economic

The small city suffered greatly in the economic

Urban League of Nebraska

also supported the movement, as did the CIO union in the meatpacking plants. Their successes led to the end of

''. 2007-12-08. Retrieved 2007-12-09.Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest ...

, began before the settlement of the city, with speculators from neighboring Council Bluffs, Iowa

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The city is the most populous in Southwest Iowa, and is the third largest and a primary city of the Omaha-Council Bluffs Metropolitan Area. It is loc ...

staking land across the Missouri River illegally as early as the 1840s. When it was legal to claim land in Indian Country, William D. Brown

William D. Brown (1813 – February 3, 1868) was the first pioneer to envision building a city where Omaha, Nebraska sits today. Many historians attribute Brown to be the founder of Omaha, although this has been disputed since the late nineteenth ...

was operating the Lone Tree Ferry The Lone Tree Ferry, later known as the Council Bluffs and Nebraska Ferry Company, was the crossing of the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha, Nebraska, US, that was established in 1850 by William D. Brown. Brown was the first pion ...

to bring settlers from Council Bluffs to Omaha. A treaty with the Omaha Tribe allowed the creation of the Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

, and Omaha City

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

was founded on July 4, 1854. With early settlement came claim jumpers and squatter

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

s, and the formation of a vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a person who ...

law group called the Omaha Claim Club The Omaha Claim Club, also called the Omaha Township Claim Association(1954 ''Omaha's First Century''. Omaha World-Herald. Retrieved 7/14/07. and the Omaha Land Company, was organized in 1854 for the purpose of "encouraging the building of a city"Mo ...

, which was one of many claim clubs across the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

. During this period many of the city's founding fathers

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

received lots in Scriptown Scriptown was the name of the first subdivision in the history of Omaha, which at the time was located in Nebraska Territory. It was called "Scriptown" because scrip was used as payment, similar to how a company would pay employees when regular mone ...

, which was made possible by the actions of the Omaha Claim Club. The club's violent actions were challenged successfully in a case ultimately decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, ''Baker v. Morton

''Baker v. Morton'', 79 U.S. (12 Wall.) 150 (1870), was the second of two land claim suits to come out of Omaha, Nebraska Territory, filed in September 1860, prior to statehood. A claim jumper filed suit against local land barons to stake out a h ...

'', which led to the end of the organization.

Surrounded by small towns and cities that competed for business from the hinterland

Hinterland is a German word meaning "the land behind" (a city, a port, or similar). Its use in English was first documented by the geographer George Chisholm in his ''Handbook of Commercial Geography'' (1888). Originally the term was associate ...

's farmers, the city suffered a major setback in the Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

. Despite this, Omaha quickly emerged as the largest city in Nebraska. After losing the Nebraska State Capitol

The Nebraska State Capitol is the seat of government for the U.S. state of Nebraska and is located in downtown Lincoln. Designed by New York architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue in 1920, it was constructed of Indiana limestone from 1922 to 19 ...

to Lincoln in 1867, many business leaders rallied and created the Jobbers Canyon

Jobbers Canyon Historic District was a large industrial and warehouse area comprising 24 buildings located in downtown Omaha, Nebraska, US. It was roughly bound by Farnam Street on the north, South Eighth Street on the east, Jackson Street on th ...

in downtown Omaha to outfit farmers in Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

, Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

and further west. Their entrepreneurial success allowed them to build mansions in Kountze Place The Kountze Place neighborhood of Omaha, Nebraska is a historically significant community on the city's north end. Today the neighborhood is home to several buildings and homes listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is located betw ...

and the Old Gold Coast

Old Gold Coast is the name of a historic district in south Omaha, Nebraska. With South 10th Street as the central artery, the area was home to neighborhoods such as Little Italy and Forest Hill. The area is referred to as "old" because it was repl ...

neighborhoods.

With the development of the Omaha Stockyards The Union Stockyards of Omaha, Nebraska, were founded in 1883 in South Omaha by the Union Stock Yards Company of Omaha. A fierce rival of Chicago's Union Stock Yards, the Omaha Union Stockyards were third in the United States for production by 1890 ...

and neighboring packinghouses in the 1870s, several workers' housing areas, including Sheelytown Sheelytown was a historic ethnic neighborhood in South Omaha, Nebraska, USA with populations of Irish, Polish and other first generation immigrants. Located north of the Union Stockyards, it was bounded by Edward Creighton Boulevard on the north, ...

, developed in South Omaha South Omaha is a former city and current district of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. During its initial development phase the town's nickname was "The Magic City" because of the seemingly overnight growth, due to the rapid development of the Union S ...

. Its growth happened so quickly that the town was nicknamed the "Magic City". The latter part of the 19th century also saw the formation of several fraternal organization

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': " brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fratern ...

s, including the formation of Knights of Aksarben. City leaders rallied for the creation of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition

The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition was a world's fair held in Omaha, Nebraska from June 1 to November 1 of 1898. Its goal was to showcase the development of the entire West, stretching from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Co ...

in 1898. During the Expo, famous madames Anna Wilson and Ada Everleigh were making a good living from the crowds. At the same time, Boss Tom Dennison compounded the city's vices in the notorious Sporting District, with the full support of eight-term mayor "Cowboy" James Dahlman

James Charles Dahlman (December 15, 1856 – January 21, 1930), also known as Jim Dahlman, Cowboy Jim and Mayor Jim, was elected to eight terms as mayor of Omaha, Nebraska, serving the city for 20 years over a 23-year-period. A German-America ...

. Many of these early pioneers are buried in Prospect Hill Cemetery. City leaders created Omaha University

The University of Nebraska Omaha (Omaha or UNO) is a public research university in Omaha, Nebraska. Founded in 1908 by faculty from the Omaha Presbyterian Theological Seminary as a private non-sectarian college, the university was originally ...

in 1908.

With reform administrations in the 1930s and 40s, the city became a meatpacking powerhouse. Several regional beer

Beer is one of the oldest and the most widely consumed type of alcoholic drink in the world, and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches, mainly derived from ce ...

breweries developed, including Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

, Storz and Krug companies. The city's southern suburb became home to the Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

in the late 1940s; in 1950 the Rosenblatt Stadium

Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium was a baseball stadium in Omaha, Nebraska, the former home to the annual NCAA Division I College World Series and the minor league Omaha Royals, now known as the Omaha Storm Chasers. Rosenblatt Stadium was the largest m ...

in South Omaha South Omaha is a former city and current district of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. During its initial development phase the town's nickname was "The Magic City" because of the seemingly overnight growth, due to the rapid development of the Union S ...

became home to the College World Series

The College World Series (CWS), officially the NCAA Men's College World Series (MCWS), is an annual baseball tournament held in June in Omaha, Nebraska. The MCWS is the culmination of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Divisi ...

. Labor unrest in the 1930s resulted in organizing of the meatpacking plants by the CIO-FCW, which built an interracial partnership and achieved real gains for the workers for some decades.

After World War II, blacks in Omaha as in other parts of the nation began to press harder for civil rights. Veterans believed they deserved full rights after fighting for the nation. Some organizations had already been formed, but they became more active, leading into the city's Civil Rights Movement.

Suburbanization and highway expansion led to white flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

to newer housing and development of middle and upper-class areas in West Omaha from the 1950s through the 1970s. The historically ethnically diverse areas of North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

and South Omaha South Omaha is a former city and current district of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. During its initial development phase the town's nickname was "The Magic City" because of the seemingly overnight growth, due to the rapid development of the Union S ...

became more concentrated by economics, race, and class. These workers suffered dramatic job losses during the industrial restructuring that increased rapidly in the 1960s, and poverty became more widespread.

White contact with Native Americans

Omaha's location near the confluence of the Missouri River andPlatte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itsel ...

has long made the location a key point of transfer for both people and goods. Prior to European-American establishment of the city, numerous Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

tribes had inhabited the area, including the Pawnee, Otoe, Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota: /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations peoples in North America. The modern Sioux consist of two major divisions based on language divisions: the Dakota and ...

, the Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

and Ioway. They had developed a semi-nomadic lifestyle necessary for survival on the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, a ...

. Since the 17th century, the Pawnee, Otoe, Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota: /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations peoples in North America. The modern Sioux consist of two major divisions based on language divisions: the Dakota and ...

, and Ioway all variously occupied the land that became Omaha. The Pawnee and Otoe tribes had inhabited the region for hundreds of years by the time the Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the ent ...

-language Omaha tribe had arrived from the lower Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

valley in the early 18th century. Translated, the word "Omaha" ( oma, Umoⁿhoⁿ) means "Dwellers on the Bluff". Usually, the word is translated "against the current," but in those cases no source is quoted.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries when they were the most powerful Indians along the stretch of the Missouri River north of the Platte, the Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest c ...

nation moved on the western edge of present-day Bellevue, Nebraska

Bellevue (French for "beautiful view"; previously named Belleview) is a suburban city in Sarpy County, Nebraska, United States. It is part of the Omaha–Council Bluffs metropolitan area, and had a population of 64,176 as of the 2020 Census, mak ...

. After a smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

outbreak, cultural degradation, the elimination of the buffalo, and continued property loss, the Omaha sold the last of their claims in 1856 and relocated to their present reservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

in Thurston County, in northeastern Nebraska.

European settlement

On July 21, 1804, the

On July 21, 1804, the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

passed by the riverbanks that would later become the city of Omaha. On July 22 the Corps of Discovery

The Corps of Discovery was a specially established unit of the United States Army which formed the nucleus of the Lewis and Clark Expedition that took place between May 1804 and September 1806. The Corps was led jointly by Captain Meriwether Lew ...

established a camp near present-day Bellevue for five nights, naming it "Camp White Catfish." On the 27th, William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Miss ...

and Reuben Fields investigated mysterious earthen mounds close to where 8th and Douglas Streets and the Heartland of America Park

Heartland of America Park is a public park located at 800 Douglas Street in downtown Omaha, Nebraska. After partially closing in 2020 due to extensive renovations, the park reopened to the public on August 18, 2023. The park is situated between ...

are today in Downtown Omaha

Downtown Omaha is the central business, government and social core of the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area, U.S. state of Nebraska. The boundaries are Omaha's 20th Street on the west to the Missouri River on the east and the centerline ...

. That night they camped in an area that is Eppley Airfield

Eppley Airfield , also known as Omaha Airport, is an airport in the midwestern United States, located northeast of downtown Omaha, Nebraska. On the west bank of the Missouri River in Douglas County, it is the largest airport in Nebraska, with ...

today.(2007"History at a glance"

, Douglas County Historical Society. Retrieved 2/2/08. The expedition stopped at a point about 20 miles (30 km) north of present-day Omaha, at which point they first met with the Otoe. They had a council meeting with members of the tribal leadership on the west side of the Missouri River. The first recorded instance of a

black person

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in s ...

in the Omaha area was "York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

", an enslaved African American who accompanied William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Miss ...

on the Expedition.

The Astor Expedition came through in 1811. Stephen Long passed through the Omaha area in 1819 on his Platte River Expedition. A decade later, adventurers and fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

rs were frequenting the region, trading at Fort Lisa, built by Manuel Lisa in 1806; Fort Atkinson, built in 1819 as a military outpost adjacent to the location of the earlier council meeting; and Cabanne's Trading Post

Cabanne's Trading Post was established in 1822 by the American Fur Company as Fort Robidoux near present-day Dodge Park in North Omaha, Nebraska, United States. It was named for the influential fur trapper Joseph Robidoux. Soon after it was op ...

, built by the American Fur Company

The American Fur Company (AFC) was founded in 1808, by John Jacob Astor, a German immigrant to the United States. During the 18th century, furs had become a major commodity in Europe, and North America became a major supplier. Several British ...

in 1822.

In 1825 a fur trader named J.B. Royce built a stockade and trading post on a plateau near the present-day block formed by Dodge Street and Capitol Avenue, Ninth and Tenth Streets. That establishment was abandoned and decayed within the next 20 years.

In the 1840s the Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into sever ...

built a town called Cutler's Park in the area before resuming their westward migration on the Mormon Trail

The Mormon Trail is the long route from Illinois to Utah that members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traveled for 3 months. Today, the Mormon Trail is a part of the United States National Trails System, known as the Mormon ...

.

In 1854 Logan Fontenelle and the Omaha Tribe sold the majority of their tribal land, four million acres (16,000 km²), to the United States for less than 22 cents an acre. This allowed the settlement of Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

and the founding of Omaha City. That year the formation of the Territory in the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

was based on the condition that it remain slave-free.

Pioneer Omaha: 1853 to 1867

In 1853

In 1853 William D. Brown

William D. Brown (1813 – February 3, 1868) was the first pioneer to envision building a city where Omaha, Nebraska sits today. Many historians attribute Brown to be the founder of Omaha, although this has been disputed since the late nineteenth ...

operated the Lone Tree Ferry The Lone Tree Ferry, later known as the Council Bluffs and Nebraska Ferry Company, was the crossing of the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha, Nebraska, US, that was established in 1850 by William D. Brown. Brown was the first pion ...

to shuttle California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

prospectors and Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what is now the state of Kans ...

settlers across the river between Kanesville, Iowa

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The city is the most populous in Southwest Iowa, and is the third largest and a primary city of the Omaha-Council Bluffs Metropolitan Area. It is l ...

and the Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

. The Lone Tree Ferry eventually became the Council Bluffs and Nebraska Ferry Company. "Omaha City" was organized by the owners of the Council Bluffs & Nebraska Ferry Company to lure the proposed transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

to Council Bluffs. Alfred D. Jones, Omaha City's first postmaster

A postmaster is the head of an individual post office, responsible for all postal activities in a specific post office. When a postmaster is responsible for an entire mail distribution organization (usually sponsored by a national government), ...

, plat

In the United States, a plat ( or ) (plan) is a cadastral map, drawn to scale, showing the divisions of a piece of land. United States General Land Office surveyors drafted township plats of Public Lands Surveys to show the distance and bea ...

ted the town site early in 1854, months after the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

created the Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

. The first black person in Omaha arrived in 1854.

While the city was young, there were no formal police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

or sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

, or at least one with any significant authority. Compensating for the absence of the law, many early Omaha pioneers formed a claim club to create and enforce a legal system to their advantage. The Omaha Claim Club The Omaha Claim Club, also called the Omaha Township Claim Association(1954 ''Omaha's First Century''. Omaha World-Herald. Retrieved 7/14/07. and the Omaha Land Company, was organized in 1854 for the purpose of "encouraging the building of a city"Mo ...

took authority over many areas of the new city, generally focused on land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various isla ...

-related issues. In the 1860s, ten years after the city's formation, early citizens also created the Old Settlers' Association to record the early history of the settlement.

Aside from Omaha, other early settlements and towns in the area include Fontenelle's Post founded in 1806; Fort Lisa founded 1806; Culter's Park

Winter Quarters was an encampment formed by approximately 2,500 members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as they waited during the winter of 1846–47 for better conditions for their trek westward. It followed a preliminary te ...

, founded 1846; Bellevue, settled in 1804 and founded 1853; East Omaha, founded 185?; and Saratoga, founded 1857. The town of Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

was platted by James C. Mitchell in 1854 and founded in 1855.

The first minister in Omaha was Moses F. Shinn, a Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. ...

leader from Council Bluffs. Most of Omaha's early pioneers, including Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

politicians, soldiers from Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha, originally known as Sherman Barracks and then Omaha Barracks, is an Indian War-era United States Army supply installation. Located at 5730 North 30th Street, with the entrance at North 30th and Fort Streets in modern-day North Omaha, ...

and the early African-American community, were buried at Prospect Hill Cemetery in North Omaha. Starting in 1887 Douglas County officials started recording the burials of poor

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse

people and people without a known identity in Potter's Field

A potter's field, paupers' grave or common grave is a place for the burial of unknown, unclaimed or indigent people. "Potter's field" is of Biblical origin, referring to Akeldama (meaning ''field of blood'' in Aramaic), stated to have been pu ...

. Located in far North Omaha

North Omaha is a community area in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States. It is bordered by Cuming and Dodge Streets on the south, Interstate 680 on the north, North 72nd Street on the west and the Missouri River and Carter Lake, Iowa on the ...

, today Potter's Field is maintained by Forest Lawn Cemetery, which is located nearby. There is speculation that Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into se ...

pioneers were buried there in the 1850s, as well.

The Nebraska State Capitol was moved from Omaha in 1867.

Nebraska Territory Capitol

Late in 1854 Omaha was chosen as the territorial capital for Nebraska. In 1855 during a land grab a group of businessmen formed theOmaha Land Company The Omaha Claim Club, also called the Omaha Township Claim Association(1954 ''Omaha's First Century''. Omaha World-Herald. Retrieved 7/14/07. and the Omaha Land Company, was organized in 1854 for the purpose of "encouraging the building of a city"Mo ...

and platted Scriptown Scriptown was the name of the first subdivision in the history of Omaha, which at the time was located in Nebraska Territory. It was called "Scriptown" because scrip was used as payment, similar to how a company would pay employees when regular mone ...

to reward Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

legislators for their votes for statehood. After ''Baker v. Morton

''Baker v. Morton'', 79 U.S. (12 Wall.) 150 (1870), was the second of two land claim suits to come out of Omaha, Nebraska Territory, filed in September 1860, prior to statehood. A claim jumper filed suit against local land barons to stake out a h ...

'' in 1857, this type of land baron

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant (also a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). When a juristic person is in this position, the ...

-like behavior was made illegal; by that time lots had been developed and Scriptown quickly became part of several neighborhoods, including Gifford Park Gifford Park is a historic neighborhood in midtown Omaha, Nebraska. It is roughly bounded by the North Freeway on the east, North 38th Street on the west, Dodge Street on the south and Cuming Street on the north. Its namesake park was added to t ...

, Prospect Hill and the Near North Side.

The small city suffered greatly in the economic

The small city suffered greatly in the economic Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

; however, the presence of the capital is credited for keeping the town alive. For several years Omaha enjoyed its status as the capital of the Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

, although not without contention. On January 1858 a group of representatives illegally moved the Nebraska Territorial Legislature to Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

following a violent outburst at the State Capitol in Omaha. After repeatedly being dogged out of voting on the removal of the Capitol from Omaha, a skirmish pitted representatives from Nebraska City

Nebraska City is a city in Nebraska, and the county seat of, Otoe County, Nebraska, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 7,289.

The Nebraska State Legislature has credited Nebraska City as being the oldest incorporated ...

, Florence, and other communities to convene outside of Omaha. Despite having a majority of members present for the vote to remove the Capitol and all agreeing, the "Florence Legislature" did not succeed in swaying the Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

governor, and the Capitol remained in Omaha until 1867 when Nebraska gained statehood

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "st ...

. When Omaha eventually lost the capital to Lincoln in 1867, the city was by then strong enough to maintain economic growth

Economic growth can be defined as the increase or improvement in the inflation-adjusted market value of the goods and services produced by an economy in a financial year. Statisticians conventionally measure such growth as the percent rate o ...

for a period of time.

Business

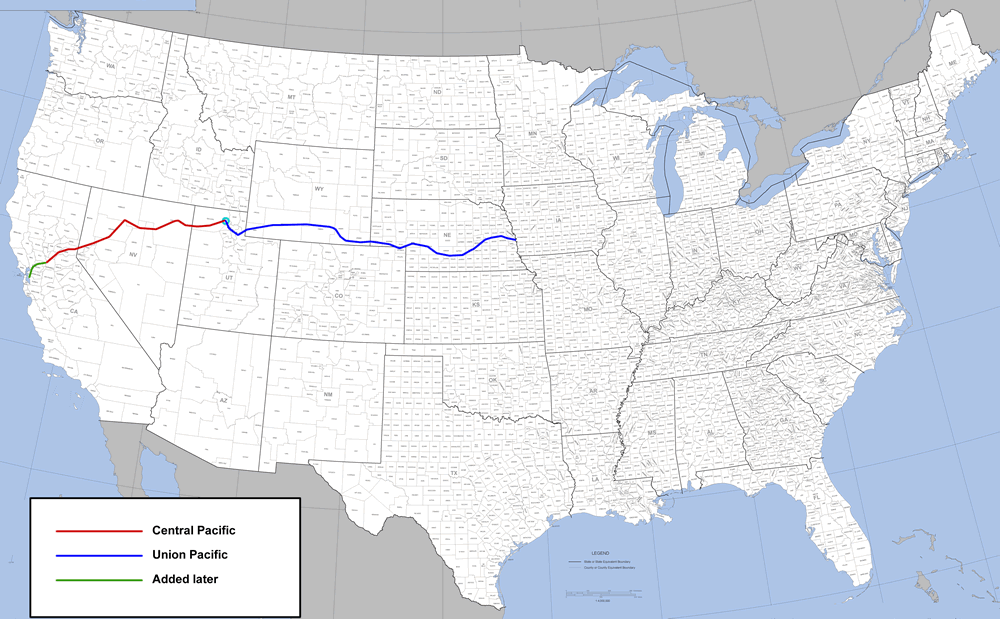

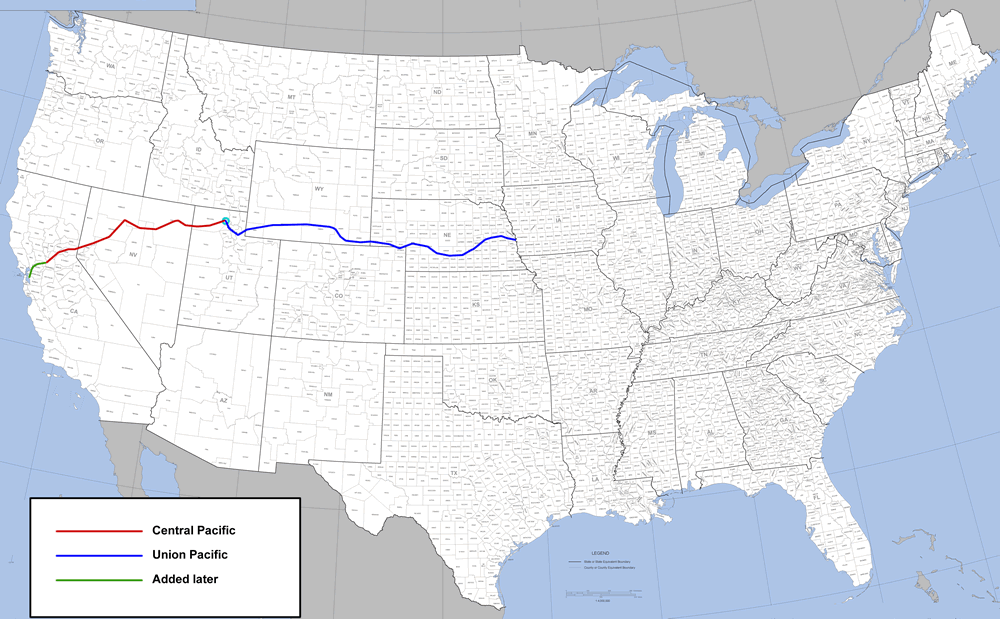

While Council Bluffs was chosen as the eastern terminus of the United States'first transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

in 1862 with the passage of the Pacific Railway Act, construction on the railroad began west from Omaha to avoid the difficulties of constructing a bridge across the Missouri River. This ensured that Omaha would become a major transportation center for the entire country in the years to come. The Omaha Cable Tramway Company The Cable Tramway Company of Omaha, Nebraska started in 1884 and ended in 1895. It was the only cable car line ever built in Omaha, and had only four lines of tracks in operation.

History

The Omaha Cable Tramway Company was originally formed in 18 ...

was the only cable car company that operated in Omaha. Founded in 1884, it operated cars until 1894. The warehousing sector became predominant early on, with the Jobber's Canyon

Jobbers Canyon Historic District was a large industrial and warehouse area comprising 24 buildings located in downtown Omaha, Nebraska, US. It was roughly bound by Farnam Street on the north, South Eighth Street on the east, Jackson Street on th ...

playing an important role. Other efforts including the market house and various hotels weren't as successful.

Development Era: 1868 to 1899

Towns founded during this period include Benson, founded 1887; Chalco, founded ?;Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, founded 1880; Elkhorn, founded 1865; Papillion, founded 1870; Ralston, founded 1888; South Omaha South Omaha is a former city and current district of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. During its initial development phase the town's nickname was "The Magic City" because of the seemingly overnight growth, due to the rapid development of the Union S ...

, founded 1886, and; Millard, which was founded in 1871.

In 1856 the Omaha Claim Club The Omaha Claim Club, also called the Omaha Township Claim Association(1954 ''Omaha's First Century''. Omaha World-Herald. Retrieved 7/14/07. and the Omaha Land Company, was organized in 1854 for the purpose of "encouraging the building of a city"Mo ...

donated two lots for the congregation to build a church, and soon after Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul com ...

, Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

s, Congregationalists, Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

s and Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

s followed. Catholics dedicated St. Philomena's Cathedral in 1856, and the entire Creighton family, including Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

, his wife Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

, and his brother John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

greatly supported the Catholic Church. Pioneer banker Augustus Kountze

Augustus Kountze (November 19, 1826–April 30, 1892) was an American businessman based in Omaha, Nebraska, Kountze, Texas and New York City. He founded a late 19th-century national banking dynasty along with his brothers Charles, Herman an ...

called for and financially supported the founding of the first Lutheran church west of the Missouri River, which was then called Immanuel Lutheran Church and was located downtown. It was renamed after Kountze's father in the 1880s. In 1871 Omaha's Jewish community bought land to create its first cemetery.

In 1879 the trial of '' Standing Bear v. Crook'' was held at Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha, originally known as Sherman Barracks and then Omaha Barracks, is an Indian War-era United States Army supply installation. Located at 5730 North 30th Street, with the entrance at North 30th and Fort Streets in modern-day North Omaha, ...

. During the trial General Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

testified on behalf of Standing Bear, leading the court to recognize American Indians as persons. This was the first time this occurred in a U.S. Federal Court

The federal judiciary of the United States is one of the three branches of the federal government of the United States organized under the United States Constitution and laws of the federal government. The U.S. federal judiciary consists primaril ...

.

In the 1880s, Omaha was said to be the fastest-growing city in the United States. After Irish-born James E. Boyd founded the first packing operation in Omaha in the 1870s, thousands of immigrants from central and southern Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

came to Omaha to work in the Union Stockyards

The Union Stock Yard & Transit Co., or The Yards, was the meatpacking district in Chicago for more than a century, starting in 1865. The district was operated by a group of railroad companies that acquired marshland and turned it into a centra ...

and slaughterhouse

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is no ...

s of South Omaha South Omaha is a former city and current district of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. During its initial development phase the town's nickname was "The Magic City" because of the seemingly overnight growth, due to the rapid development of the Union S ...

. They created Omaha's original ethnic neighborhoods, with names such as Sheelytown Sheelytown was a historic ethnic neighborhood in South Omaha, Nebraska, USA with populations of Irish, Polish and other first generation immigrants. Located north of the Union Stockyards, it was bounded by Edward Creighton Boulevard on the north, ...

, Greek Town

Greektown is a general name for an ethnic enclave populated primarily by Greeks or people of Greek ancestry, usually in an urban neighborhood.

History

The oldest Greek dominated neighborhood outside of Greece were probably the Fener in Istanb ...

, Little Italy

Little Italy is a general name for an ethnic enclave populated primarily by Italians or people of Italian ancestry, usually in an urban neighborhood. The concept of "Little Italy" holds many different aspects of the Italian culture. There are ...

, Little Bohemia and Little Poland. Other neighborhoods founded during this period included Bemis Park, Country Club

A country club is a privately owned club, often with a membership quota and admittance by invitation or sponsorship, that generally offers both a variety of recreational sports and facilities for dining and entertaining. Typical athletic offe ...

, Dog Hollow and Field Club. The Near North Side also developed greatly during this period, with high concentrations of Jews and Germans, and the first groups of African Americans.

Omaha's growth was accelerated in the 1880s by the rapid development of the Union Stockyards

The Union Stock Yard & Transit Co., or The Yards, was the meatpacking district in Chicago for more than a century, starting in 1865. The district was operated by a group of railroad companies that acquired marshland and turned it into a centra ...

and the meat packing industry

The meat-packing industry (also spelled meatpacking industry or meat packing industry) handles the slaughtering, processing, packaging, and distribution of meat from animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep and other livestock. Poultry is generally no ...

in South Omaha South Omaha is a former city and current district of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. During its initial development phase the town's nickname was "The Magic City" because of the seemingly overnight growth, due to the rapid development of the Union S ...

. The "Big Four" packers during this time were Armour

Armour (British English) or armor (American English; see spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, especially direct contact weapons or projectiles during combat, or f ...

, Wilson

Wilson may refer to:

People

*Wilson (name)

** List of people with given name Wilson

** List of people with surname Wilson

* Wilson (footballer, 1927–1998), Brazilian manager and defender

* Wilson (footballer, born 1984), full name Wilson R ...

, Cudahy, and Swift

Swift or SWIFT most commonly refers to:

* SWIFT, an international organization facilitating transactions between banks

** SWIFT code

* Swift (programming language)

* Swift (bird), a family of birds

It may also refer to:

Organizations

* SWIFT, ...

. There were several breweries established throughout the city during this period. The "Big Four" breweries in Omaha were the Storz, Krug, Willow Springs and Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

breweries

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of beer ...

.

Culture in Omaha

The culture of Omaha, Nebraska, has been partially defined by music and college sports, and by local cuisine and community theatre. The city has a long history of improving and expanding on its cultural offerings. In the 1920s, the '' Omaha Bee'' ...

grew extensively during this era. With the increase in population, many social, fraternal and advocacy organizations formed in Omaha in the late 19th century. The city's premier newspapers, the ''Omaha Bee

The ''Omaha Daily Bee'' was a leading Republican newspaper that was active in the late 19th and early 20th century. The paper's editorial slant frequently pitted it against the ''Omaha Herald'', the '' Omaha Republican'' and other local papers. ...

'' and the ''Omaha World-Herald

The ''Omaha World-Herald'' is a daily newspaper in the midwestern United States, the primary newspaper of the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area. It was locally owned from its founding in 1885 until 2020, when it was sold to the newspaper ch ...

'', were founded in 1874 and 1885, respectively. Omaha was the location of the 1892 convention that formed the Populist Party, with its aptly titled '' Omaha Platform'' written by "radical farmers" from throughout the Midwest.

In 1894 the Ladies Axillary of the Ancient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is now in the United States, where it was founded in N ...

, a nationalistic Irish-Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

fraternal organization

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': " brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fratern ...

, was founded in Omaha. That year the city was also the site of the first African-American fair held in the United States. The following year the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben

The Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben Foundation is a 501(c)(3) civic and philanthropic organization in Omaha, Nebraska.

History

The organization was formed in 1895 in an attempt to keep the Nebraska State Fair in Omaha after receiving an ultimatum to provide ...

, a civic and philanthropic organization, was founded.

The Trans-Mississippi Exposition

The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition was a world's fair held in Omaha, Nebraska from June 1 to November 1 of 1898. Its goal was to showcase the development of the entire West, stretching from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Co ...

was held in North Omaha

North Omaha is a community area in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States. It is bordered by Cuming and Dodge Streets on the south, Interstate 680 on the north, North 72nd Street on the west and the Missouri River and Carter Lake, Iowa on the ...

from June 1 to November 1, 1898. The exposition drew more than 2 million visitors. It required the construction of attractions spanning 100 city blocks, including a ship-worthy lagoon, bridges and magnificent (though temporary) buildings constructed of plaster and horsehair. The Exposition also featured a number of sideshows, including Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), known as "Buffalo Bill", was an American soldier, bison hunter, and showman. He was born in Le Claire, Iowa Territory (now the U.S. state of Iowa), but he lived for several years ...

's Wild West Show and the Everleigh House. Run by Ada

Ada may refer to:

Places

Africa

* Ada Foah, a town in Ghana

* Ada (Ghana parliament constituency)

* Ada, Osun, a town in Nigeria

Asia

* Ada, Urmia, a village in West Azerbaijan Province, Iran

* Ada, Karaman, a village in Karaman Province, T ...

and Minna Everleigh, the house continued operating until 1900, when the two women moved to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

.

This period also saw the rise of formal crime in Omaha that presaged the arrival of Tom Dennison. The Sporting District was an area in downtown Omaha where many of the city's vice activities happened, including gambling, prostitution, and grafting. Anna Wilson was an early madam who got her start in Omaha. She eventually opened a 25-room mansion brothel

A brothel, bordello, ranch, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in sexual activity with prostitutes. However, for legal or cultural reasons, establishments often describe themselves as massage parlors, bars, strip clubs, body rub p ...

at Ninth and Douglas Streets. She was the longtime romantic partner of Dan Allen, a well-known and successful riverboat gambler in Omaha. The 1900 kidnap

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the p ...

ing of Edward Cudahy, Jr.

Edward Aloysius Cudahy Jr. (August 22, 1885 - January 8, 1966), also known as Eddie Cudahy, was kidnapped on December 18, 1900 in Omaha, Nebraska. Edward Cudahy Sr. was the wealthy owner of the Cudahy Packing Company, which helped build the Omaha ...

in the Old Gold Coast

Old Gold Coast is the name of a historic district in south Omaha, Nebraska. With South 10th Street as the central artery, the area was home to neighborhoods such as Little Italy and Forest Hill. The area is referred to as "old" because it was repl ...

neighborhood caused a national uproar. The perpetrator, Pat Crowe, became a nationally renowned author and lecturer on criminal justice reforms.

Establishment Era: 1900 to 1941

In the decades beforeWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Omaha went through a prosperous period marked with rapid development, cultural growth and massive growth of population throughout the city. African Americans were recruited for work by the meatpacking industry and came North in the Great Migration in highest numbers after 1910. This was also the period of highest immigration by Polish workers. A number of new residents established communities throughout the city, older immigrant populations became further assimilated into the city's culture, and growth was accommodated in neighborhoods built to the north and south of Downtown Omaha

Downtown Omaha is the central business, government and social core of the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area, U.S. state of Nebraska. The boundaries are Omaha's 20th Street on the west to the Missouri River on the east and the centerline ...

. The early 1910s saw the growth of the city's Automobile Row along Farnam Street.

The city suffered greatly during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Federal intervention throughout the 1930s was critical for many residents. Work Progress Administration (WPA) and Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a ...

(CCC) projects employed many men in projects to build infrastructure of parks and community facilities. All of the current city core was surrounded by farms by this period, with buildings such as the Ackerhurst Dairy Barn indicative of that phase.

Sports

Omaha University

The University of Nebraska Omaha (Omaha or UNO) is a public research university in Omaha, Nebraska. Founded in 1908 by faculty from the Omaha Presbyterian Theological Seminary as a private non-sectarian college, the university was originally ...

was founded at the Redick Mansion in the Kountze Place The Kountze Place neighborhood of Omaha, Nebraska is a historically significant community on the city's north end. Today the neighborhood is home to several buildings and homes listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is located betw ...

neighborhood in 1908, moving to their present campus in 1929. Their football team played on the Saratoga School field until 1952.

The Omaha Omahogs was a baseball team

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

started in 1900 as part of the new Western League. Their name changed to the Omaha Indians in 1902. In 1904 the team was fielded as the Omaha Packers, and in 1906 as the Omaha Rourkes. They kept that name until 1921 when the name changed to the Omaha Buffaloes, which stuck until 1928 when it changed to the Omaha Crickets. In 1930 the team changed its name back to the Omaha Packers and kept that name until 1935 when they moved to Council Bluffs and subsequently folded. A new team called the Omaha Robin Hoods formed in 1936, but moved to Rock Island, Illinois

Rock Island is a city in and the county seat of Rock Island County, Illinois, United States. The original Rock Island, from which the city name is derived, is now called Arsenal Island. The population was 37,108 at the 2020 census. Located on t ...

late in the year. The team reformed shortly thereafter as the Omaha Cardinals, remaining as such for several years.

Greek Town Riot

New immigrants jostled for position with those who had arrived earlier and competition for jobs and place was intense. Many immigrant ethnic groups were intensely territorial. In 1909 a mob of 1,000 ethnic white men from South Omaha almost lynched aGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

man for supposedly being involved with a "white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

" woman. After their efforts were thwarted, the mob grew and swarmed into Greek Town, where they destroyed homes, businesses and a school; beat Greek immigrants; and destroyed the area by burning it. No person was indicted for any aspect of the riot.

Easter Sunday Tornado

In 1913 a devastating tornado ripped through Omaha, becoming known as the Easter Sunday tornado. It killed more than 100 people, destroyed hundreds of homes, and cut a long swathe through the city, including the heart of North Omaha's Jewish and African-American commercial district, which suffered the most damage.Omaha Race Riot

Social tensions simmered in the postwar years, as the nation adjusted to returning veterans, competition for jobs, and fears about labor unrest. After a summer of race riots in numerous industrial cities across the country, Omaha was tense, too. The newspaper had inflamed feelings with sensational stories accusing black men of crimes. The black population increased dramatically from 1910-1920 when they were recruited to work by the stockyards. When many black men worked as strikebreakers, resentment by other working-class, ethnic white men rose against them. The "independent political boss" Tom Dennison was later implicated of contributing to racial tensions in an effort to turn out a reform mayor. The spark of the Omaha Race Riot of 1919 occurred when a black man named Will Brown was arrested and accused of raping a young white woman from South Omaha. A mob of mostly white ethnic young men marched from South Omaha (rallied and led by a henchman of Dennison's) and converged on the Douglas County Courthouse, where the jail was. In the evening the crowd grew larger and set the courthouse on fire, forcing police to turn Brown over to them. They lynched him, hanging him from a lamppost on the south side of the courthouse, then dragging his body through the streets and burning it. The mob was mostly European-born immigrants and ethnicEuropean American

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent Eu ...

s. The mayor attempted to intervene and was also hanged; he was saved only by a last-minute rescue by federal agents. The city had to ask for help from Federal troops to quell the disorder, and their arrival was delayed because of a series of communication problems. The commander stationed troops in South Omaha to prevent more mobs from forming, and in North Omaha to protect the blacks.

In 1998 Max Sparber's play about the events was produced by the Blue Barn Theatre

The Bluebarn Theatre, located at 1106 S. 10th Street in Omaha, Nebraska, United States, is a nationally recognized theater.

Begun in 1989, the theater was founded by a group of 1988 graduates from the theater program at Purchase College: Kevin La ...

at the Douglas County Courthouse, the site of the riot. It was performed in several other cities as well.

Social and cultural developments

Job's Daughters International, aMasonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

youth organization

The following is a list of youth organizations. A youth organization is a type of organization with a focus upon providing activities and socialization for minors. In this list, most organizations are international unless noted otherwise.

...

for girls, was founded in Omaha in 1920. Aleph Zadik Aleph

The Grand Order of the Aleph Zadik Aleph (AZA or ) is an international youth-led fraternal organization for Jewish teenagers, founded in 1924 and currently existing as the male wing of BBYO Inc., an independent non-profit organization. It is for ...

, the men's Order of the B'nai B'rith Youth Organization, began in 1923 as a college fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin '' frater'': "brother"; whence, "brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternity ...

.

In 1925 Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

was born (as Malcolm Little) at 3446 Pinkney Street in North Omaha. His minister father moved the family to Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee i ...

when Malcolm was a year old after threats on their lives from the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

because of his father's activism.

The Nebraska chapter of the National German-American Alliance (NGAA) was founded and led by Valentin J. Peter

Valentin J. Peter (1875–1960) was a German-American publisher of a German language newspaper called the '' Omaha Tribüne'' in Omaha, Nebraska. He had immigrated to the United States from Bavaria in 1889. Active in the ethnic German commu ...

, the publisher and editor of the German language

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is also a ...

'' Omaha Tribune'' in 1907. By the 1920s the organization was working closely with breweries throughout the city to challenge the complete political and social assimilation of German immigrants in Nebraska. During the same period Peter was buying other German-language newspapers across the U.S. The NGAA folded in the late 1920s; Peter's business, the Interstate Publishing Company, still operates in Omaha today.

Tom Dennison

The reign of Omaha political boss Tom Dennison ended in 1933. For more than thirty-five years, he controlled gambling, drinking, prostitution and other criminal interests throughout Omaha, particularly in his seedy Sporting District. He controlled bootlegging operations inLittle Italy

Little Italy is a general name for an ethnic enclave populated primarily by Italians or people of Italian ancestry, usually in an urban neighborhood. The concept of "Little Italy" holds many different aspects of the Italian culture. There are ...

through the Prohibition Era. He was closely allied with James Dahlman

James Charles Dahlman (December 15, 1856 – January 21, 1930), also known as Jim Dahlman, Cowboy Jim and Mayor Jim, was elected to eight terms as mayor of Omaha, Nebraska, serving the city for 20 years over a 23-year-period. A German-America ...

, Omaha's only eight-term mayor. Dennison was implicated in agitation of groups related to the Omaha Race Riot of 1919.

World War II

In 1945 theEnola Gay

The ''Enola Gay'' () is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Colonel Paul Tibbets. On 6 August 1945, piloted by Tibbets and Robert A. Lewis during the final stages of World War II, it ...

and Bockscar

''Bockscar'', sometimes called Bock's Car, is the name of the United States Army Air Forces B-29 bomber that dropped a Fat Man nuclear weapon over the Japanese city of Nagasaki during World War II in the secondand most recent nuclear attack in ...

were two of 536 B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 ...

es manufactured at the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Factory (now Offutt Air Force Base

Offutt Air Force Base is a U.S. Air Force base south of Omaha, adjacent to Bellevue in Sarpy County, Nebraska. It is the headquarters of the U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), the 557th Weather Wing, and the 55th Wing (55 WG) of the Ai ...

) in suburban Bellevue.

That same year a Japanese fire balloon

An incendiary balloon (or balloon bomb) is a balloon inflated with a lighter-than-air gas such as hot air, hydrogen, or helium, that has a bomb, incendiary device, or Molotov cocktail attached. The balloon is carried by the prevailing winds t ...

exploded over Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

. The incident was part of a large World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

campaign by the Japanese military to cause mass chaos in American cities. The story was suppressed by the American military until after the war was over, as no one was hurt in the explosion.

Civil Rights Movement Era

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

activism

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived greater good. Forms of activism range fro ...

in Omaha began in 1912 with the formation of a local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.& ...

. It continued through the coming years under the influence of local leaders Whitney Young, George Wells Parker

George Wells Parker (September 18, 1882 – July 28, 1931) was an African-American political activist, historian, public intellectual, and writer who co-founded the Hamitic League of the World.

Biography

George Wells Parker's parents were b ...

and Harry Haywood

Harry Haywood (February 4, 1898 – January 4, 1985) was an American political activist who was a leading figure in both the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). His goal was to connect ...

. Other organizations formed such as the Citizens Civic Committee for Civil Liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties ma ...

(4CL) and the DePorres Club

The DePorres Club was an early pioneer organization in the Civil Rights Movement in Omaha, Nebraska, whose "goals and tactics foreshadowed the efforts of civil rights activists throughout the nation in the 1960s." The club was an affiliate of COR ...

at Creighton University

Creighton University is a private Jesuit research university in Omaha, Nebraska. Founded by the Society of Jesus in 1878, the university is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission. In 2015 the university enrolled 8,393 graduate and undergra ...

in the 1940s. Mainstream organizations including the Omaha Urban League (now thUrban League of Nebraska

also supported the movement, as did the CIO union in the meatpacking plants. Their successes led to the end of

redlining

In the United States, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which services ( financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as "hazardous" to investment; these neighborhoods have sign ...

and discriminatory neighborhood covenants, as well as the implementation of a school integration plan. In the late 1960s, the student-led Black Association for Nationalism Through Unity

The Black Association for Nationalism Through Unity, or BANTU, was a youth activism group focused on black power and nationalism in Omaha, Nebraska in the 1960s. Its name is a reference to the Bantu peoples of Southern Africa.

It was reportedl ...

(BANTU) adopted a more militant posture and got into confrontations with police following the shooting of a youth in the housing project.

Transformative Era: 1950 to 1999

In 1950, theNCAA

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is a nonprofit organization that regulates student athletics among about 1,100 schools in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. It also organizes the athletic programs of colleges ...

moved the College World Series

The College World Series (CWS), officially the NCAA Men's College World Series (MCWS), is an annual baseball tournament held in June in Omaha, Nebraska. The MCWS is the culmination of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Divisi ...

(CWS) to Rosenblatt Stadium

Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium was a baseball stadium in Omaha, Nebraska, the former home to the annual NCAA Division I College World Series and the minor league Omaha Royals, now known as the Omaha Storm Chasers. Rosenblatt Stadium was the largest m ...

, (then known as Omaha Municipal Stadium). Started in 1947, the tournament was held at Kalamazoo, Michigan

Kalamazoo ( ) is a city in the southwest region of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is the county seat of Kalamazoo County. At the 2010 census, Kalamazoo had a population of 74,262. Kalamazoo is the major city of the Kalamazoo-Portage Metropoli ...

in 1947 and 1948, and Wichita, Kansas

Wichita ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Sedgwick County. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 397,532. The Wichita metro area had a population of 647,610 in 2020. It is located in ...

in 1949. Since 1950 the series has been held annually at the Rosenblatt, despite bids from several cities to move the CWS to another venue. More than 6,000,000 fans have attended CWS games in Omaha. The City of Omaha has regularly expanded and renovated the stadium to accommodate fans, teams, and media covering the event. ESPN

ESPN (originally an initialism for Entertainment and Sports Programming Network) is an American international basic cable sports channel owned by ESPN Inc., owned jointly by The Walt Disney Company (80%) and Hearst Communications (20%). The ...

televised every game of the event from 1980 through 1987. ESPN started coverage again when the championship series went to a best-of-3 format in 2003. From 1988 through 2002, CBS televised the championship game: a winner-take-all single game.

In 1955 the Omaha Cardinals joined the AAA American Association American Association may refer to:

Baseball

* American Association (1882–1891), a major league active from 1882 to 1891

* American Association (1902–1997), a minor league active from 1902 to 1962 and 1969 to 1997

* American Association of Profe ...

, and thrived until the late 1950s. That team folded in 1959. In 1961-62 the Omaha Dodgers were the farm team for the Los Angeles Dodgers

The Los Angeles Dodgers are an American professional baseball team based in Los Angeles. The Dodgers compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) National League West, West division. Established in 1883 i ...

. After the city went six years without a professional team, the Omaha Royals

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest c ...

started in 1969. The Omaha Royals become the Omaha Storm Chasers in 2011.

By the 1960s, the Omaha Stockyards had become the world's largest livestock processing center. They surpassed Chicago's Union Stock Yards

The Union Stock Yard & Transit Co., or The Yards, was the meatpacking district in Chicago for more than a century, starting in 1865. The district was operated by a group of railroad companies that acquired marshland and turned it into a central ...