History of Mississippi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the state of

At the end of the last Ice Age, Native Americans or Paleo-Indians appeared in what today is the Southern United States. Paleo-Indians in the South were hunter-gatherers who pursued the megafauna that became extinct following the end of the

At the end of the last Ice Age, Native Americans or Paleo-Indians appeared in what today is the Southern United States. Paleo-Indians in the South were hunter-gatherers who pursued the megafauna that became extinct following the end of the  The Mississippian culture disappeared in most places around the time of European encounter. Archaeological and linguistic evidence has shown their descendants are the historic

The Mississippian culture disappeared in most places around the time of European encounter. Archaeological and linguistic evidence has shown their descendants are the historic

The first major European expedition into the territory that became Mississippi was Spanish, led by Hernando de Soto, which passed through in the early 1540s. The French claimed the territory that included Mississippi as part of their colony of

The first major European expedition into the territory that became Mississippi was Spanish, led by Hernando de Soto, which passed through in the early 1540s. The French claimed the territory that included Mississippi as part of their colony of

The Mississippi Territory was sparsely populated and suffered initially from a series of difficulties that hampered its development.

The Mississippi Territory was sparsely populated and suffered initially from a series of difficulties that hampered its development.

More than 80,000 Mississippians fought in the

More than 80,000 Mississippians fought in the  As Union troops advanced, many slaves escaped and joined their lines to gain freedom. After the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863, more slaves left the plantations. Thousands of former slaves in Mississippi enlisted in the

As Union troops advanced, many slaves escaped and joined their lines to gain freedom. After the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863, more slaves left the plantations. Thousands of former slaves in Mississippi enlisted in the  General

General

Most whites supported the Confederacy, but there were holdouts. The most vehemently anti-Confederate areas in Mississippi were Jones County in the southeastern corner of the state, and Itawamba County and

Most whites supported the Confederacy, but there were holdouts. The most vehemently anti-Confederate areas in Mississippi were Jones County in the southeastern corner of the state, and Itawamba County and

Univ of North Carolina Press, 2006, p. 3 The ''New York Times'' also carried reporting on the congressional investigation into these events, beginning in January 1875. The Democratic Party had factions of the Regulars and New Departures, but as the state election of 1875 approached, they united and worked on the " Mississippi Plan", to organize whites to defeat both white and black Republicans. They used economic and political pressure against scalawags and carpetbaggers, persuading them to change parties or leave the state. Armed attacks by the Red Shirts,

There was steady economic and social progress among some classes in Mississippi after the Reconstruction era, despite the low prices for cotton and reliance on agriculture. Politically the state was controlled by the conservative elite whites, known as "

There was steady economic and social progress among some classes in Mississippi after the Reconstruction era, despite the low prices for cotton and reliance on agriculture. Politically the state was controlled by the conservative elite whites, known as "

University of Virginia Press, 2000 The sharecropping system, as Cresswell (2006) shows, functioned as a compromise between white landowners' desire for a reliable supply of labor, and black workers' refusal to work in gangs. By the turn of the century, much of the second-generation of black owner-farmers had lost their land. In 1890 the state adopted a new constitution that imposed a poll tax of $2 a year, which the great majority of blacks and poor whites could not pay to register to vote; they were effectively excluded from the political process. These requirements, with additions in legislation of 1892, resulted in a 90% reduction in the number of blacks who voted. In every county whites allowed a handful of prominent black ministers and local leaders to vote. As only voters could serve on juries, disenfranchisement meant blacks could not serve on juries, and they lost all chance at local and state offices, as well as representation in Congress. When these provisions survived a Supreme Court challenge in 1898 in '' Williams v. Mississippi'', other southern state legislatures rapidly incorporated them into new constitutions or amendments, effectively extending disfranchisement to every southern state. In 1900 the population of Mississippi was nearly 59% African American, but they were virtually excluded from political life. The Jim Crow system became total after 1900, with disenfranchisement, coupled with increasingly restrictive racial segregation laws, and increased lynchings. Economic disasters always lurked, such as failure of the cotton crop due to

''Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture,'' accessed August 27, 2012 The

The war years brought prosperity as cotton prices soared and new war installations paid high wages. Many blacks headed to northern and western cities, particularly in California, as part of the second and larger wave of the Great Migration. White farmers often headed to southern factory towns. Young men, white and black, were equally subject to the draft, but farmers were often exempt on occupational grounds. The

The war years brought prosperity as cotton prices soared and new war installations paid high wages. Many blacks headed to northern and western cities, particularly in California, as part of the second and larger wave of the Great Migration. White farmers often headed to southern factory towns. Young men, white and black, were equally subject to the draft, but farmers were often exempt on occupational grounds. The

''Jackson Free Press'', May 9, 2012

online edition

* Swain, Martha H. ed. ''Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives'' (2003). 17 short biographies

Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2007. 185 pp * Carson, James Taylor. ''Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal,'' Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999

Peacock, Evan. ''Mississippi Archaeology Q and A''

Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2005

Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 1986/3rd edition, 2010 * White, Douglas R., George P. Murdock, Richard Scaglion. "Natchez Class and Rank Reconsidered." ''Ethnology'' 10:369–388. (1971). Study of the Natchez nation before the French-Indian wars of the 1720s

online

online

* Currie, James T. ''Enclave: Vicksburg and Her Plantations, 1863–1870'' (1980) * Dittmer, John. ''Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi'' (1994) * Dollard, John. ''Caste and Class in a Southern Town'' (1957) sociological case study of race and class in the 1930s * Greenberg, Kenneth S. "The Civil War and the Redistribution of Land: Adams County, Mississippi, 1860–1870," ''Agricultural History'', Vol. 52, No. 2 (Apr. 1978), pp. 292–307 {{JSTOR, 3742925 * Helferich, Gerry. ''High Cotton: Four Seasons in the Mississippi Delta'' (2007), growing cotton in the 21st century * James, Dorris Clayton. ''Ante-Bellum Natchez'' (1968) * Morris, Christopher. ''Becoming Southern: The Evolution of a Way of Life, Warren County and Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1770–1860'' (1995) * Nelson, Lawrence J. "Welfare Capitalism on a Mississippi Plantation in the Great Depression." ''Journal of Southern History'' 50 (May 1984): 225–250. {{JSTOR, 2209460 * Owens, Harry P. ''Steamboats and the Cotton Economy: River Trade in the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta'' (1990). * Polk, Noel. ''Natchez before 1830'' (1989) * Von Herrmann, Denise. ''Resorting to Casinos: The Mississippi Gambling Industry'' (2006) {{ISBN? * Willis, John C. ''Forgotten Time: The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta After the Civil War'' (2000) * Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. ''American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta'' (2003)

excerpt and text search

* Evers, Charles. ''Have No Fear: The Charles Evers Story'' (1997), memoir of a black politician {{ISBN? * Moody, Anne. ''Coming of Age in Mississippi''. (1968) memoir of Black girlhood * Percy, William Alexander. ''Lanterns on the Levee; Recollections of a planter's son'' (1941) 347 p

excerpt and text search

* Rosengarten, Theodore. ''All God's Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw'' (1974) memoir of a Black Mississippian {{ISBN? * Waters, Andrew, ed. ''Prayin' to Be Set Free: Personal Accounts of Slavery in Mississippi'' (2002) 196 pp{{ISBN?

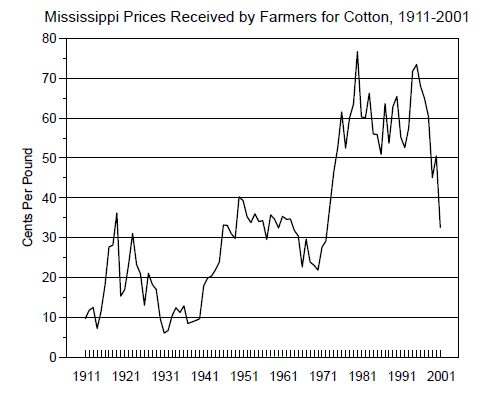

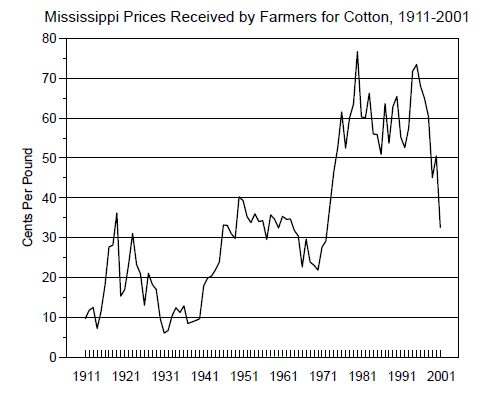

Charts and data on farm production, 1911–201

Reconstruction in Mississippi

(by Professor Donald J. Mabry)

The Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice

(by David M. Oshinsky)

Mississippi Historical Society: Mississippi History Now

{{Mississippi {{Years in Mississippi {{U.S. political divisions histories {{Authority control

Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

extends back to thousands of years of indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. Evidence of their cultures has been found largely through archeological excavations, as well as existing remains of earthwork mounds built thousands of years ago. Native American traditions were kept through oral histories; with Europeans recording the accounts of historic peoples they encountered. Since the late 20th century, there have been increased studies of the Native American tribes and reliance on their oral histories to document their cultures. Their accounts have been correlated with evidence of natural events.

Initial colonization of the region was carried out by the French, though France would cede their control over portions of the region to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, particularly along the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

. European-American

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent E ...

settlers did not enter the territory in great number until the early 19th century. Some European-American settlers would bring many enslaved Africans with them to serve as laborers to develop cotton plantations along major riverfronts. On December 10, 1817, Mississippi became a state of the United States. Through the 1830s, the federal government forced most of the native Choctaw and Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

people west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

. American planters developed an economy based on the export of cotton produced by slave labor along the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers. A small elite group of planters controlled most of the richest land, the wealth, and politics of the state, which led to Mississippi seceding from the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

in 1861. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

(1861–1865), its river cities particularly were sites of extended battles. Following the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865, Mississippi would enter the Reconstruction era (1865–1877).

The bottomlands of the Mississippi Delta were still 90% undeveloped after the Civil War. Thousands of migrants, both black and white, entered this area for a chance at land ownership. They sold timber while clearing land to raise money for purchases. During the Reconstruction era, many freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

became owners of farms in these areas, and by 1900, composed two-thirds of the property owners in the Mississippi Delta. Democrats regained control of the state legislature in the late 19th century, and in 1890, passed a disfranchising constitution, resulting in the exclusion of African Americans from political life until the mid-1960s. Most African Americans lost their lands due to disenfranchisement, segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

, financial crises, and an extended decline in cotton prices. By 1920, most African Americans in the state were landless sharecroppers

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

and tenant farmers. However in the 1930s, some African Americans acquired land under low-interest loans from New Deal programs; in 1960 Holmes County still had 800 black farmers, the most of any county in the state. The state continued to rely mostly on agriculture and timber through the mid-20th century, but mechanization

Mechanization is the process of changing from working largely or exclusively by hand or with animals to doing that work with machinery. In an early engineering text a machine is defined as follows:

In some fields, mechanization includes the ...

and acquisition of properties by megafarms would change the face of the labor market and state economy.

During the early through mid-20th century, the two waves of the Great Migration led to hundreds of thousands of rural blacks leaving the state. As a result, by the 1930s, African Americans were a minority of the state population for the first time since the early 19th century. They would remain a majority of the population in many Delta counties. Mississippi also had numerous sites of activism related to the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

during the 1950s and 1960s, as African Americans sought to re-establish their constitutional rights for access to public facilities, including all state universities, and the ability to register, vote, and run for office.

By the early 21st century Mississippi had made notable progress in overcoming attitudes and attributes that had impeded social, economic, and political development. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina would cause severe damage along Mississippi's Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

. The tourism industry in Mississippi would help play a key role in helping build the states economy in the early 21st century. Mississippi would also expand its professional communities in cities such as Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Qu ...

, the state capital. Top industries in Mississippi today include agriculture, forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests, woodlands, and associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. ...

, manufacturing, transportation and utilities

A public utility company (usually just utility) is an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure). Public utilities are subject to forms of public control and ...

, and health services.

Native Americans

At the end of the last Ice Age, Native Americans or Paleo-Indians appeared in what today is the Southern United States. Paleo-Indians in the South were hunter-gatherers who pursued the megafauna that became extinct following the end of the

At the end of the last Ice Age, Native Americans or Paleo-Indians appeared in what today is the Southern United States. Paleo-Indians in the South were hunter-gatherers who pursued the megafauna that became extinct following the end of the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

age. A variety of indigenous cultures arose in the region, including some that built great earthwork mounds more than 2,000 years ago.Busbee (2005)

The successive mound building Troyville, Coles Creek, and Plaquemine culture

The Plaquemine culture was an archaeological culture (circa 1200 to 1700 CE) centered on the Lower Mississippi River valley. It had a deep history in the area stretching back through the earlier Coles Creek (700-1200 CE) and Troyville culture ...

s occupied western Mississippi bordering the Mississippi River during the Late Woodland period

In the classification of archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 BCE to European contact in the eastern part of North America, with some archaeolog ...

. During the Terminal Coles Creek period (1150 to 1250 CE) contact increased with Mississippian cultures centered upriver near St. Louis, Missouri. This led to the adaption of new pottery techniques, as well as new ceremonial objects and possibly new forms of social structuring. As more Mississippian culture influences were absorbed the Plaquemine area as a distinct culture began to shrink after 1350 CE. Eventually the last enclave of purely Plaquemine culture was the Natchez Bluffs area, while the Yazoo Basin and adjacent areas of Louisiana became a hybrid Plaquemine-Mississippian culture. Historic groups in the area during first European contact bear out this division. In the Natchez Bluffs, the Taensa

The Taensa (also Taënsas, Tensas, Tensaw, and ''Grands Taensas'' in French) were a Native American people whose settlements at the time of European contact in the late 17th century were located in present-day Tensas Parish, Louisiana. The mean ...

and Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

had held out against Mississippian influence and continued to use the same sites as their ancestors and carry on the Plaquemine culture. Groups who appear to have absorbed more Mississippian influence were identified at the time of European contact as those tribes speaking the Tunican, Chitimachan, and Muskogean languages

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

.

The Mississippian culture disappeared in most places around the time of European encounter. Archaeological and linguistic evidence has shown their descendants are the historic

The Mississippian culture disappeared in most places around the time of European encounter. Archaeological and linguistic evidence has shown their descendants are the historic Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

and Choctaw peoples, who were later counted by colonists as among the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

of the Southeast. Other tribes who inhabited the territory that became known as Mississippi (and whose names were given by colonists to local towns and features) include the Natchez, Yazoo, Pascagoula

The Pascagoula (also Pascoboula, Pacha-Ogoula, Pascagola, Pascaboula, Paskaguna) were an indigenous group living in coastal Mississippi on the Pascagoula River.

The name ''Pascagoula'' is a Mobilian Jargon term meaning "bread people". Choctaw ...

, and the Biloxi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in and one of two county seats of Harrison County, Mississippi, United States (the other being the adjacent city of Gulfport). The 2010 United States Census recorded the population as 44,054 and in 2019 the estimated popu ...

. French, Spanish and English settlers all traded with these tribes in the early colonial years.

Pressure from European-American settlers increased during the early nineteenth century, after invention of the cotton gin made cultivation of short-staple cotton profitable. This was readily cultivated in the upland areas of the South, and its development could feed an international demand for cotton in the 19th century. Migrants from the United States entered Mississippi mostly from the north and east, coming from the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

and coastal areas. Eventually they gained passage of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

in 1830, which achieved federal forced removal of most of the indigenous peoples during the 1830s to areas west of the Mississippi River.

European colonial period

The first major European expedition into the territory that became Mississippi was Spanish, led by Hernando de Soto, which passed through in the early 1540s. The French claimed the territory that included Mississippi as part of their colony of

The first major European expedition into the territory that became Mississippi was Spanish, led by Hernando de Soto, which passed through in the early 1540s. The French claimed the territory that included Mississippi as part of their colony of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

and started settlement along the Gulf Coast. They created the first Fort Maurepas under Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

on the site of modern Ocean Springs

Ocean Springs is a city in Jackson County, Mississippi, United States, approximately east of Biloxi and west of Gautier. It is part of the Pascagoula, Mississippi Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 17,225 at the 2000 U.S. Census ...

(or Old Biloxi) in 1699.

In 1716, the French founded Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

as ''Fort Rosalie

Fort Rosalie was built by the French in 1716 within the territory of the Natchez Native Americans and it was part of the French colonial empire in the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi.

Early history

As part of the peace terms that ...

'' on the Mississippi River; it became the dominant town and trading post of the area. In this period of the early 18th century, the French Roman Catholic Church created pioneer parishes at Old Biloxi/Ocean Springs and Natchez. The church also established seven pioneer parishes in present-day Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

and two in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

, which was also part of New France.

The French and later Spanish colonial rule influenced early social relations of the settlers who held enslaved Africans. As in Louisiana, for a period there developed a third class of free people of color. They were chiefly descendants of white European colonists and enslaved African or African-American mothers. The planters often had formally supportive relationships with their mistresses of color, known in French as ''plaçage

Plaçage was a recognized extralegal system in French and Spanish slave colonies of North America (including the Caribbean) by which ethnic European men entered into civil unions with non-Europeans of African, Native American and mixed-race descen ...

''. They sometimes freed them and their multiracial children. The fathers passed on property to their mistresses and children, or arranged for the apprenticeship or education of children so they could learn a trade. Some wealthier male colonists sent their mixed-race sons to France for education, and some entered the military there. Free people of color often migrated to , where there was more opportunity for work and a bigger community of their class.

As part of New France, Mississippi was also ruled by the Spanish after France's defeat in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

(1756–63). Later it was briefly part of West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

under the British. In 1783 the Mississippi area was deeded by Great Britain to the United States after the latter won its independence in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, under the terms of the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

. Following the Peace of Paris (1783)

The Peace of Paris of 1783 was the set of treaties that ended the American Revolutionary War. On 3 September 1783, representatives of King George III of Great Britain signed a treaty in Paris with representatives of the United States of America� ...

the southern third of Mississippi came under Spanish rule as part of West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

.

Through the colonial period, the various tribes of Native Americans changed alliances trying to achieve the best trading and other conditions for themselves.

Territory and statehood

Before 1798 the state ofGeorgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

claimed the entire region extending west from the Chattahoochee to the Mississippi River and tried to sell lands there, most notoriously in the Yazoo land scandal

The Yazoo land scandal, Yazoo fraud, Yazoo land fraud, or Yazoo land controversy was a massive real-estate fraud perpetrated, in the mid-1790s, by Georgia governor George Mathews and the Georgia General Assembly. Georgia politicians sold large ...

of 1795. Georgia finally ceded the disputed area in 1802 to the United States national government for its management. In 1804, after the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, the government assigned the northern part of this cession to Mississippi Territory. The southern part became the Louisiana Territory.

The Mississippi Territory was sparsely populated and suffered initially from a series of difficulties that hampered its development.

The Mississippi Territory was sparsely populated and suffered initially from a series of difficulties that hampered its development. Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795 by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

of 1795 ended Spanish control over Mississippi, but Spain continued to hamper the territory's growth by harassing commercial traders. It restricted American trading and travel on the Mississippi River down to , the major port on the Gulf Coast.

Winthrop Sargent

Winthrop Sargent (May 1, 1753 – June 3, 1820) was a United States patriot, politician, and writer; and a member of the Federalist party.

Early life

Sargent was born in Gloucester, Massachusetts on May 1, 1753. He was one of eight childre ...

, territorial governor in 1798, proved unable to impose a code of laws. Not until the emergence of cotton as a profitable staple crop in the nineteenth century, after the invention of the cotton gin, were the riverfront areas of Mississippi developed as cotton plantations. These were based on slave labor, and developed most intensively along the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers, bordering the Mississippi Delta. The rivers offered the best transportation to markets.

Americans had continuing land disputes with the Spanish, even after taking control of much of this territory through the Louisiana Purchase (1803) from France. In 1810 the European-American settlers in parts of West Florida rebelled and declared their freedom from Spain. President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

declared that the region between the Mississippi and Perdido rivers, which included most of West Florida, had already become part of the United States under the terms of the Louisiana Purchase. The section of West Florida between the Pearl and Perdido rivers, known as the District of Mobile, was annexed to Mississippi Territory in 1812; Americans from the United States occupied Kiln, Mississippi, in 1813.

Settlement

The attraction of vast amounts of high-quality, fertile and inexpensive cotton land attracted hordes of settlers, mostly from Georgia andthe Carolinas

The Carolinas are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina, considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia to the southwest. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east.

Combining Nor ...

, and from former tobacco areas of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and North Carolina in the Upper South. By this time, most planters in the Upper South had switched to mixed crops, as their lands were exhausted from tobacco and it was barely profitable as a commodity crop.

From 1798 through 1820, the population in the Mississippi Territory rose dramatically, from less than 9,000 to more than 222,000. The vast majority were enslaved African Americans brought by settlers or shipped by slave traders. Migration came in two fairly distinct waves—a steady movement until the outbreak of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, and a flood after it was ended, from 1815 through 1819. The postwar flood was catalyzed by various factors: high prices for cotton, the elimination of Indian titles to much land, new and improved roads, and the acquisition of new direct water outlets to the Gulf of Mexico. The first migrants were traders and trappers, then herdsmen, and finally farmers. Conditions on the Southwest frontier initially resulted in a relatively democratic society for whites. But expansion of cotton cultivation resulted in an elite group of white planters who controlled politics in the state for decades.

Cotton

Expansion of cultivation of cotton into the Deep South was enabled by the invention of the cotton gin, which made processing of short-staple cotton profitable. This type was more readily grown in upland and inland areas, in contrast to the long-staple cotton of theSea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the Southeastern United States. Numbering over 100, they are located between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns Rivers along the coast of South Caroli ...

and Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

. Americans pressed to gain more land for cotton, causing conflicts with the several tribes of Native Americans who historically occupied this territory of the Southeast. Five of the major tribes had adopted some western customs and had members who assimilated to varying degrees, often based on proximity and trading relationships with whites.

Through the 1830s, state and federal US governments forced the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

to cede their lands. Various US leaders developed proposals for removal of all Native Americans to west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

. This took place following passage of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

in 1830 by Congress. As Indians ceded their lands to whites through the Southeast, they moved west and became more isolated from the American planter society, where many African Americans were enslaved. The state sold off the ceded lands, and white migration into the state continued. Some families brought slaves with them; most slaves were transported into the area from the Upper South in a forced migration through the domestic slave trade.

Statehood

In 1817 elected delegates wrote a constitution and applied to Congress for statehood. On December 10, 1817, the western portion of Mississippi Territory became the State of Mississippi, the 20th state of the Union.Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

, long established as a major river port, was the first state capital. As more population came into the state and future growth was anticipated, in 1822 the capital was moved to the more central location of Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Qu ...

.

Religion

French colonists had established theCatholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in their colonial settlements along the coast, such as Biloxi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in and one of two county seats of Harrison County, Mississippi, United States (the other being the adjacent city of Gulfport). The 2010 United States Census recorded the population as 44,054 and in 2019 the estimated popu ...

. As Americans entered the territory, they brought their strongly Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

tradition. Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians made up the three leading denominations in the territory, and their congregations rapidly built new churches and chapels. By this time, many slaves were already Christians, attending church under the supervision of white planters. They also developed their own private worship and celebrations on the larger plantations. Adherents to other religions were a distinct minority. Some Protestant ministers won converts and often promoted education, although there was no state public school system until it was authorized after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

by the Reconstruction-era biracial legislature.

Whereas in the first Great Awakening, Protestant ministers of these denominations had promoted abolition of slavery, by the early 19th century, when the Deep South was being developed, most had retreated to support for slavery. They argued instead for an improved paternalism under Christianity by white slaveholders. This sometimes led to improved treatment for the enslaved.

Government

William C. C. Claiborne (1775–1817), a lawyer and former Republican congressman fromTennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

(1797–1801), was appointed by President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

as governor and superintendent of Indian affairs in the Mississippi Territory from 1801 through 1803. Although he favored acquiring some land from the Choctaw and Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

, Claiborne was generally sympathetic and conciliatory toward Indians. He worked long and patiently to iron out differences that arose, and to improve the material well-being of the Indians. He was partly successful in promoting the establishment of law and order; his offer of a $2,000 reward helped destroy a gang of outlaws headed by Samuel Mason

Samuel Ross Mason, also spelled Meason (November 8, 1739 – 1803), was a Virginia militia captain, on the American western frontier, during the American Revolutionary War. After the war, he became the leader of the Mason Gang, a criminal gang o ...

(1750–1803). His position on issues indicated a national rather than regional outlook, though he did not ignore his constituents. Claiborne expressed the philosophy of the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

and helped that party defeat the Federalists. When a smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemic broke out in the spring of 1802, Claiborne directed the first recorded mass vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

in the territory. This prevented the spread of the epidemic in Natchez.

Native American lands

The United States government removed land from the Chickasaw and Choctaw tribes from 1801 to about 1830, as white settlers entered the territory from coastal states. After Congressional passage of theIndian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830, the government forced the tribes to accept lands west of the Mississippi River in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

. Most left the state, but those who remained became United States citizens.

After 1800 the rapid development of a cotton economy and the slave society of the Deep South changed the economic relationship of native Indians with whites and slaves in Mississippi Territory. As Indians ceded their lands to whites in the eastern sections, they moved west in the state, becoming more isolated from whites and blacks. The following table illustrates ceded land in acres:

Antebellum period

The exit of most of the Native Americans meant that vast new lands were open to settlement, and tens of thousands of immigrant Americans poured in. Men with money brought slaves and purchased the best cotton lands in the Delta region along the Mississippi River. Poor men took up poor lands in the rest of the state, but the vast majority of the state was still undeveloped at the time of the Civil War.Cotton

By the 1830s Mississippi was a leading cotton producer, increasing its demand for enslaved labor. Some planters considered slavery a "necessary evil" to make cotton production profitable, for the survival of the cotton economy, and were brought in from the border states and the tobacco states where slavery was declining. The 1832 state constitution forbade any further importation of slaves by the domestic slave trade, but the provision was found to be unenforceable, and it was repealed. As planters increased their holdings of land and slaves, the price of land rose, and small farmers were driven into less fertile areas. An elite slave-owning class arose that wielded disproportionate political and economic power. By 1860, of the 354,000 whites, only 31,000 owned slaves and two-thirds of these held fewer than 10. Fewer than 5,000 slaveholders had more than 20 slaves; 317 possessed more than 100. These 5,000 planters, especially the elite among them, controlled the state. In addition a middle element of farmers owned land but no slaves. A small number of businessmen and professionals lived in the villages and small towns. The lower class, or "poor whites", occupied marginal farm lands remote from the rich cotton lands and grew food for their families, not cotton. Whether they owned slaves or not, however, most white Mississippians supported the slave society; all whites were considered above blacks in social status. They were both defensive and emotional on the subject of slavery. Aslave insurrection

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freedo ...

scare in 1836 resulted in the hanging of a number of slaves, as was common in the South after such incidents. Several white northerners were suspected of being secret abolitionists.Sydnor (1933)

When cotton was king during the 1850s, Mississippi plantation owners—especially those in the old Natchez District

The Natchez District was one of two areas established in the Kingdom of Great Britain's West Florida colony during the 1770sthe other being the Tombigbee District. The first Anglo settlers in the district came primarily from other parts of Britis ...

, as well as the newly emerging Delta and Black Belt region of the uplands in the center of the state—became increasingly wealthy due to the great fertility of the soil and the high price of cotton on the international market. The severe wealth imbalances and the necessity of large-scale slave populations to sustain such income played a strong role in state politics and political support for secession. Mississippi was among the six states in the Deep South with the highest proportion of slave population; it was the second state to secede from the union.

Mississippi's population grew rapidly due to migration, both voluntary and forced, reaching 791,305 in 1860. Blacks numbered 437,000, making up 55% of the population; they were overwhelmingly enslaved. Cotton production grew from 43,000 bales in 1820 to more than one million bales in 1860, as Mississippi became the leading cotton-producing state. With international demand high, Mississippi and other Deep South cotton was exported to the textile factories of Britain and France, as well as those in New York and New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

. The Deep South was the major supplier and had strong economic ties with the Northeast. By 1820, half of the exports from New York City were related to cotton. Southern businessmen traveled so frequently to the city that they had favorite hotels and restaurants.

In Mississippi some modernizers encouraged crop diversification, and production of vegetables and livestock increased, but King Cotton prevailed. Cotton's ascendancy was seemingly justified in 1859, when Mississippi planters were scarcely touched by the financial panic in the North. They were concerned by inflation of the price of slaves but were in no real distress. Mississippi's per capita wealth was well above the U.S. average. The major planters made very large profits, but they invested it on buying more cotton lands and more slaves, which pushed up prices even higher. They educated their children privately, and the state government made little investment in infrastructure. Railroad construction lagged behind that of other states, even in the South. The threat of abolition troubled planters, but they believed that if needed, the cotton states could secede from the Union, form their own country, and expand to the south in Mexico and Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. Until late 1860 they never expected a war.

The relatively low population of the state before the Civil War reflected the fact that much of the state was still frontier and needed many more settlers for development. For instance, except for riverside settlements and plantations, 90% of the Mississippi Delta bottom lands were still undeveloped and covered mostly in mixed forest and swampland. These areas were not cleared and developed until after the war. During and after Reconstruction, most of the new owners in the Delta were freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

, who bought the land by clearing it and selling off timber.

Slavery

At the time of the Civil War, the great majority of blacks were slaves living on plantations with 20 or more fellow slaves, many in much larger concentrations. While some had been born in Mississippi, many had been transported to the Deep South in a forcible migration through the domesticslave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

from the Upper South. Some were shipped from the Upper South in the coastwise slave trade, while others were taken overland or forced to make the entire journey on foot.

The typical division of labor on a large plantation included an elite of house slave

A house slave was a slave who worked, and often lived, in the house of the slave-owner, performing domestic labor. House slaves performed largely the same duties as all domestic workers throughout history, such as cooking, cleaning, serving meals, ...

s, a middle group of overseers, drivers (gang leaders) and skilled craftsmen, and a "lower class" of unskilled field workers whose main job was hoeing and picking cotton. The owners hired white overseers to direct the work. Some slaves resisted by work slowdowns and by breaking tools and equipment. Others left for a while, hiding out for a couple of weeks in woods or nearby plantations. There were no slave revolts of any size, although whites often circulated fearful rumors that one was about to happen. Most slaves who tried to escape were captured and returned, though a handful made it to northern states and eventual freedom.

Most slaves endured the harsh routine of plantation life. Because of their concentration on large plantations, within these constraints they built their own culture, often developing leaders through religion, and others who acquired particular skills. They created their own religious practices and worshipped sometimes in private, developing their own style of Christianity and deciding which stories, such as the Exodus

The Exodus (Hebrew: יציאת מצרים, ''Yeẓi’at Miẓrayim'': ) is the founding myth of the Israelites whose narrative is spread over four books of the Torah (or Pentateuch, corresponding to the first five books of the Bible), namely E ...

, spoke most to them. While slave marriages were not legally recognized, many families formed unions that lasted, and they struggled to maintain their stability. Some slaves with special skills attained a quasi-free status, being leased out to work on riverboats or in the port cities. Those on the riverboats got to travel to other cities; they were part of a wide information network among slaves.

By 1820, 458 former slaves had been freed in the state. The legislature restricted their lives, requiring free blacks to carry identification and forbidding them from carrying weapons or voting. In 1822 planters decided it was too awkward to have free blacks living near slaves and passed a state law forbidding emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranch ...

except by special act of the legislature for each manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

. In 1860 only 1,000 of the 437,000 blacks in the state were recorded as free. Most of these free people lived in wretched conditions near Natchez.

Politics

Mississippi was a stronghold ofJacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, And ...

, which glorified the independent farmer; the legislature named the state capital in Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's honor. Corruption and land speculation caused a severe blow to state credit in the years preceding the Civil War. Federally allocated funds were misused, tax collections embezzled, and finally, in 1853, two state-supported banks collapsed when their debts were repudiated. In the Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels ...

(1820s to 1850s), Mississippi moved politically from a divided Whig and Democratic state to a one-party Democratic state bent on secession.

Criticism from Northern abolitionists escalated after the Mexican War ended in 1848. Mississippi and other southern planters expected the war to gain new territory where slavery could flourish. The South resisted attacks by abolitionists, and white Mississippians were among those who became outspoken defenders of the slave system. An abortive secession attempt in 1850 was followed by a decade of political agitation during which the protection and expansion of slavery became their major goal. When Republican Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

was elected president in 1860 with the goal seeking an eventual end of slavery, Mississippi followed South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and seceded from the Union on January 9, 1861. Mississippi's U.S. senator Jefferson Davis was chosen as president of the Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

.

Civil War

More than 80,000 Mississippians fought in the

More than 80,000 Mississippians fought in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. Fear that white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

might be lost were among the reasons that men joined the Confederate Army. Men who owned more property, including slaves, were more likely to volunteer. Men in Mississippi's river counties, regardless of their wealth or other characteristics, joined at lower rates than those living in the state's interior. River-county residents were especially vulnerable and apparently left their communities for safer areas (and sometimes moved out of the Confederacy) rather than face invasion.

Both the Union and Confederacy knew control of the Mississippi River was critical to the war. Union forces mounted major military operations to take over Vicksburg, with General Ulysses S. Grant launching the Shiloh and Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

campaigns and the siege of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Mis ...

, from the spring of 1862 to the summer of 1863. The most important was the Vicksburg Campaign, fought for control of the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. The fall of the city to General Grant on July 4, 1863, gave the Union control of the Mississippi River, cut off the western states, and made the Confederate cause in the west hopeless.

As Union troops advanced, many slaves escaped and joined their lines to gain freedom. After the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863, more slaves left the plantations. Thousands of former slaves in Mississippi enlisted in the

As Union troops advanced, many slaves escaped and joined their lines to gain freedom. After the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863, more slaves left the plantations. Thousands of former slaves in Mississippi enlisted in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

in 1863 and the following years.

At the Battle of Grand Gulf, Admiral Porter led seven Union ironclads

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

in an attack on the fortifications and batteries at Grand Gulf, Mississippi. His goal was to take over the Confederate guns and secure the area with troops of McClernand's XIII Corps, who were on the accompanying transports and barges. The Confederates won but it was a hollow victory; the Union defeat at Grand Gulf caused only a slight change in Grant's offensive.

Grant won the Battle of Port Gibson

The Battle of Port Gibson was fought near Port Gibson, Mississippi, on May 1, 1863, between Union and Confederate forces during the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. The Union Army was led by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and was v ...

. Advancing toward Port Gibson, Grant's army ran into Confederate outposts after midnight. Union forces advanced on the Rodney Road and a plantation road at dawn, and were met by Confederates. Grant forced the Confederates to fall back to new defensive positions several times during the day; they could not stop the Union onslaught and left the field in the early evening. This defeat demonstrated that the Confederates were unable to defend the Mississippi River line; the Federals secured their needed beachhead.

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's march from Vicksburg to Meridian, Mississippi, was designed to destroy the strategic railroad center of Meridian, which had been supplying Confederate needs. The campaign was Sherman's first application of total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

tactics, prefiguring his March to the Sea through Georgia in 1864.

The Confederates didn't have better luck at the Battle of Raymond. On May 10, 1863, Pemberton sent troops from Jackson to Raymond, to the southwest. Brig. Gen. Gregg had an over-strength brigade, but they had endured a grueling march from Port Hudson, Louisiana, arriving in Raymond late on May 11. The next day he tried to ambush a small Union raiding party. The party was Maj. Gen. John A. Logan's Division of the XVII Corps. Gregg tried to hold Fourteen Mile Creek, and a sharp battle ensued for six hours, but the overwhelming Union force prevailed and the Confederates retreated. This left the Southern Railroad of Mississippi vulnerable to Union forces, severing the lifeline of Vicksburg.

In April–May 1863 Union colonel Benjamin H. Grierson led a major cavalry raid that raced through Mississippi and Louisiana, destroying railroads, telegraph lines, and Confederate weapons and supplies. The raid also served as a diversion to take away Confederate attention from Grant's moves toward Vicksburg.

A Union expedition in June 1864, commanded by General Samuel D. Sturgis, was opposed by Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest. They clashed at the Battle of Brice's Crossroads on June 10, 1864, and Forrest routed the Yankees in his greatest battlefield victory.

Free State of Jones and Unionism

Most whites supported the Confederacy, but there were holdouts. The most vehemently anti-Confederate areas in Mississippi were Jones County in the southeastern corner of the state, and Itawamba County and

Most whites supported the Confederacy, but there were holdouts. The most vehemently anti-Confederate areas in Mississippi were Jones County in the southeastern corner of the state, and Itawamba County and Tishomingo County

Tishomingo County is a county located in the northeastern corner of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, the population was 19,593. Its county seat is Iuka.

History

Tishomingo County was organized February 9, 1836, from Ch ...

in the northeastern corner. Among the most influential Mississippi Unionists were Newton Knight, who helped form the "Free State of Jones", and Presbyterian minister John Aughey, whose sermons and book ''The Iron Furnace or Slavery and Secession'' (1863) became hallmarks of the anti-secessionist cause in the state. Mississippi would furnish around 545 white troops for the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

.

Homefront

After each battle, there was increased economic chaos and local societal breakdown. State government during the course of the war transferred around the state. It moved from Jackson to Enterprise, to Meridian and back to Jackson, to Meridian and then to Columbus and Macon, Georgia, and finally back to what was left of Jackson. The first of the two wartime governors was theFire-Eater

Fire eating is the act of putting a flaming object into the mouth and extinguishing it. A fire eater can be an entertainer, a street performance, street performer, part of a sideshow or a circus act but has also been part of spiritual traditi ...

John J. Pettus, who carried the state into secession, whipped up the war spirit, began military and domestic mobilization, and prepared to finance the war. His successor, General Charles Clark, elected in 1863, remained committed to continuing the fight regardless of the cost, but he faced a deteriorating military and economic situation. The war presented both men with enormous challenges in providing an orderly, stable government for Mississippi.

There were no slave insurrections, but many slaves escaped to Union lines. Numerous plantations turned to food production. The federal government wanted to keep up cotton production to fulfill the North's needs, and some planters sold their cotton to Union Treasury agents for high prices. The Confederates considered this a sort of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

but were unable to stop the lucrative trading on the black market.

The war shattered the lives of all classes, high and low. Upper-class ladies replaced balls and parties with bandage-rolling sessions and fund-raising efforts. But soon enough they were losing brothers, sons and husbands to battlefield deaths and disease, lost their incomes and luxuries, and had to deal with chronic shortages and poor ersatz substitutes for common items. They took on unexpected responsibilities, including the chores previously left to slaves when the latter struck out for freedom. The women coped by focusing on survival. They maintained their family honor by upholding Confederate patriotism to the bitter end. Less privileged white women struggled even more to hold their families together in their men's absence; many became refugees in camps or fled to Union lines. After the war, Southern women organized to create Confederate cemeteries and memorials, becoming champions of the "Lost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Firs ...

" and shapers of social memory.

Black women and children had an especially hard time as the plantation regime collapsed; many took refuge in camps operated by the Union Army. They were freed after the Emancipation Proclamation but suffered from widespread diseases that flourished in the crowded camps. Disease was also common in the troop camps; during the war, more men on both sides died of disease than of wounds or direct warfare.

Reconstruction

After the defeat of the Confederacy, President Andrew Johnson appointed a temporary state government under provisional governor Judge William Lewis Sharkey (1798–1873). It repealed the 1861 Ordinance of Secession and wrote new "Black Codes", defining and limiting the civil rights of freedmen, the former slaves. The whites tried to restrict the African Americans to a second-class status without citizenship or voting rights. Johnson was following the previously expressed policies of his predecessor, 16th PresidentAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. He had planned a generous and tolerating Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

policy towards the former Confederates and southerners. He intended to grant citizenship and voting rights first to Black veterans, while slowly integrating the remainder of the freedmen into the political and economic life in the nation and the "new South".

The Black Codes were never implemented. Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recon ...

s in the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, with the early support of President Lincoln, objected strongly to the intent to impose new restrictions on the movement and rights of freedmen. The federal government established the Freedmen's Bureau as an agency to help educate and assist the former slaves, in the U.S. War Department. It attempted to help the freedmen negotiate contracts and other relations in the new free labor market. Most officials in the Freedmen's Bureau were former Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

officers from the North. Many settled permanently in the state, with some becoming political leaders in the Republican Party and in business (they were scornfully known as " carpetbaggers" by white Democrats in the South). The Black Codes outraged northern opinion, as they represented an attempt to reassert conditions of slavery and white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

. They were not fully implemented in any state. White Mississippians and other Southerners were committed to restoring white supremacy and circumscribing the legal, civil, political, and social rights of the freedmen.

In September 1865 Congress was under the control of more Radical Republicans from the North, and refused to seat the newly elected Mississippi delegation. Responding to tumultuous conditions and violence, in 1867, Congress passed Reconstruction legislation. It used U.S. Army forces to occupy and manage various areas of the South in an effort to create a new order, and Mississippi was one of the areas designated to be under military control.

The military Governor-General, and Union Army Gen. Edward O.C. Ord, (1818–1883), commander of the Mississippi/Arkansas District, was assigned to register the state's electorate so that voters could elect representatives to write a new state constitution reflecting the granting of citizenship and the franchise to freedmen through amendments to the United States Constitution. In a contested election, the state's white voters rejected the proposal of a new state constitution. Mississippi continued to be governed by federal martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

. Union Gen. Adelbert Ames

Adelbert Ames (October 31, 1835 – April 13, 1933) was an American sailor, soldier, and politician who served with distinction as a Union Army general during the American Civil War. A Radical Republican, he was military governor, U.S. Senat ...

(1835–1933) of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

, under direction from the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

majority in the U.S. Congress, deposed the provisional civil government appointed by President Johnson. He enabled all black men of age to enroll as voters (not just veterans), and temporarily prohibited about a thousand or so former Confederate leaders to vote or hold state offices.

In 1868 a biracial coalition (dominated by whites) drafted a new constitution for the state; it was adopted by referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

. The Constitutional Convention was the first political organization in the state's history to include African American (then referred to as "Negro" or "Colored") representatives, but they did not dominate the convention, nor the later state legislature. Freedmen numbered 17 among the 100 members, although blacks comprised more than half of the state population of the time. Thirty-two Mississippi counties had black majorities, but freedmen elected whites as well as blacks to represent them.

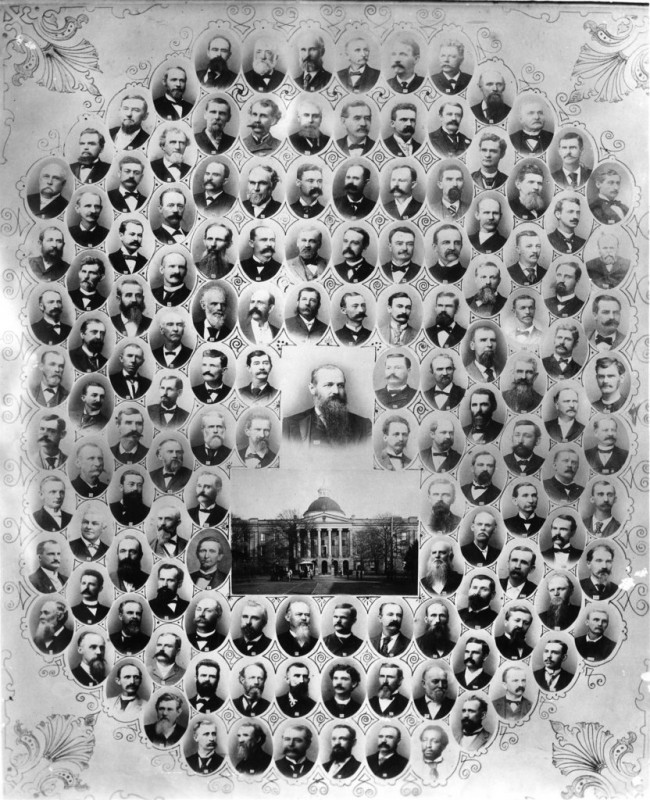

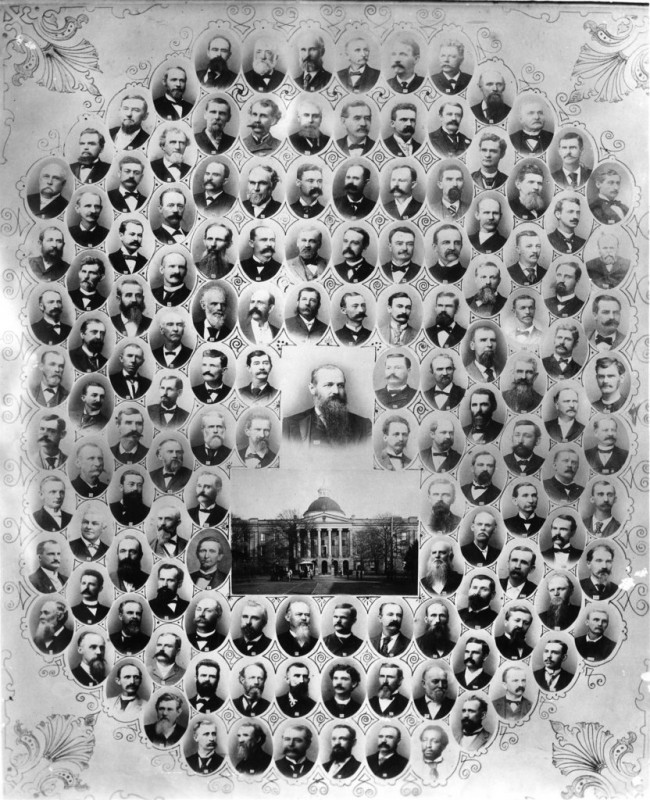

The 1868 constitution had major elements that lasted for 22 years. The convention adopted universal male suffrage (unrestricted by property qualifications, educational requirements or poll taxes