History of Minnesota on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the U.S. state of

The history of the U.S. state of

The oldest known human remains in Minnesota, dating back about 9,000 years ago, were discovered near Browns Valley in 1933. "Browns Valley Man" was found with tools of the Clovis and

The oldest known human remains in Minnesota, dating back about 9,000 years ago, were discovered near Browns Valley in 1933. "Browns Valley Man" was found with tools of the Clovis and  Archaeological evidence of Native American presence dates between 2,500 and 5,000 years ago at the

Archaeological evidence of Native American presence dates between 2,500 and 5,000 years ago at the

In the late 1650s, Pierre Esprit Radisson and

In the late 1650s, Pierre Esprit Radisson and  Father

Father

All of the land east of the Mississippi River was granted to the United States by the Second Treaty of Paris, which in 1783 ended of the

All of the land east of the Mississippi River was granted to the United States by the Second Treaty of Paris, which in 1783 ended of the

By 1851, treaties between Native American tribes and the U.S. government had opened much of Minnesota to settlement, so Fort Snelling no longer was a frontier outpost. It served as a training center for soldiers during the

By 1851, treaties between Native American tribes and the U.S. government had opened much of Minnesota to settlement, so Fort Snelling no longer was a frontier outpost. It served as a training center for soldiers during the

During the Civil War, the state faced another crisis as the Dakota War of 1862 broke out. As white settlement pressed in, the Dakota were destitute, even starving because of loss of habitat of huntable game. Dakota had signed the

During the Civil War, the state faced another crisis as the Dakota War of 1862 broke out. As white settlement pressed in, the Dakota were destitute, even starving because of loss of habitat of huntable game. Dakota had signed the

Oliver Hudson Kelley played an important role in farming as one of the founders of the

Oliver Hudson Kelley played an important role in farming as one of the founders of the

At the end of the 19th century, several forms of industrial development shaped Minnesota. In 1882, a

At the end of the 19th century, several forms of industrial development shaped Minnesota. In 1882, a

* At a Minneapolis campus from 1927 until the 1990s, Honeywell Information Systems, Honeywell, experts in variable feedback-control, had a national profile in military technology. Medtronic, founded in a Minneapolis garage in 1949, is the world's largest medical device maker as of 2020.

Hubert Humphrey was an influential Minnesota Democrat who became Minneapolis mayor (1945), United States Senate, U.S. senator (1948–1964, elected three times), and Vice President of the United States, U.S. vice president (1965–1969). In 1944 he and others worked to merge Democrats and the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party into the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party. Proposed by Humphrey, the country’s first municipal fair employment law was adopted while he was mayor. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which Humphrey called his greatest achievement, was based on ideas that Humphrey had introduced in the Senate for the previous fifteen years. Lyndon B. Johnson recruited Humphrey for his running mate in the 1964 United States presidential election, 1964 presidential election. Humphrey's support of the Vietnam War is said to have cost him the U.S. presidency.

Eugene McCarthy Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, (DFL) served in the

Hubert Humphrey was an influential Minnesota Democrat who became Minneapolis mayor (1945), United States Senate, U.S. senator (1948–1964, elected three times), and Vice President of the United States, U.S. vice president (1965–1969). In 1944 he and others worked to merge Democrats and the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party into the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party. Proposed by Humphrey, the country’s first municipal fair employment law was adopted while he was mayor. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which Humphrey called his greatest achievement, was based on ideas that Humphrey had introduced in the Senate for the previous fifteen years. Lyndon B. Johnson recruited Humphrey for his running mate in the 1964 United States presidential election, 1964 presidential election. Humphrey's support of the Vietnam War is said to have cost him the U.S. presidency.

Eugene McCarthy Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, (DFL) served in the

online

* Carroll, Jane Lamm. "Good Times, Eh? Minnesota's Territorial Newspapers". ''Minnesota History'' (1998): 222–234. * George, Stephen. ''Enterprising Minnesotans: 150 Years of Business Pioneers'' (U of Minnesota Press, 2003) * Gilman, Rhoda R. "Territorial Imperative: How Minnesota Became the 32nd State". ''Minnesota History'' (1998): 154–171. in JSTOR * Gilman, Rhoda R. "The history and peopling of Minnesota: Its culture". ''Daedalus'' (2000): 1–29. * Hatle, Elizabeth Dorsey. ''The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota'' (The History Press, 2013). * Meyer, Sabine N. ''We Are What We Drink: The Temperance Battle in Minnesota'' (U of Illinois Press, 2015) * Nziramasanga, Caiphas T. "Minnesota: First State to Send Troops." ''Journal of the West'' 14 (1975): 42+.

Minnesota Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Minnesota History of Minnesota, History of the United States by state, Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

is shaped by its original Native American residents, European exploration and settlement

Settlement may refer to:

* Human settlement, a community where people live

*Settlement (structural), the distortion or disruption of parts of a building

*Closing (real estate), the final step in executing a real estate transaction

*Settlement (fin ...

, and the emergence of industries made possible by the state's natural resources. Early economic growth was based on fur trading, logging, milling and farming, and later through railroads, and iron mining.

The earliest known settlers followed herds of large game to the region during the last glacial period. They preceded the Anishinaabe

The Anishinaabeg (adjectival: Anishinaabe) are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples present in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. They include the Ojibwe (including Saulteaux and Oji-Cree), Odawa, Potawa ...

, the Dakota, and other Native American inhabitants. Fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

rs from France arrived during the 17th century. Europeans moving west during the 19th century drove out most of the Native Americans. Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

, built to protect United States territorial interests, brought early settlers to the future state. They used Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony ( dak, italics=no, Owámniyomni, ) located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, is the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late 1 ...

to power sawmills in the area that became Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

, while others settled downriver in the area that became Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

.

Minnesota's legal identity was created as the Minnesota Territory

The Territory of Minnesota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1849, until May 11, 1858, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Minnesota and west ...

in 1849, and it became the 32nd U.S. state on May 11, 1858. After the chaos of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

and the Dakota War of 1862 ended, the state's economy grew when its timber and agriculture resources were developed. Railroads attracted immigrants, established the farm economy, and brought goods to market. The power provided by St. Anthony Falls spurred the growth of Minneapolis, and the innovative milling methods gave it the title of the "milling capital of the world".

New industry came from iron ore, discovered in the north, mined relatively easily from open pits, and shipped to Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

steel mills from the ports at Duluth

, settlement_type = City

, nicknames = Twin Ports (with Superior), Zenith City

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top: urban Duluth skyline; Minnesota ...

and Two Harbors. Economic development and social changes led to an expanded role for state government and a population shift from rural areas to cities. The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

brought layoffs in mining and tension in labor relations, but New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

programs helped the state. After World War II, Minnesota became known for technology, fueled by early computer companies Sperry Rand

Sperry Corporation was a major American equipment and electronics company whose existence spanned more than seven decades of the 20th century. Sperry ceased to exist in 1986 following a prolonged hostile takeover bid engineered by Burroug ...

, Control Data

Control Data Corporation (CDC) was a mainframe and supercomputer firm. CDC was one of the nine major United States computer companies through most of the 1960s; the others were IBM, Burroughs Corporation, DEC, NCR, General Electric, Honeywel ...

, and Cray

Cray Inc., a subsidiary of Hewlett Packard Enterprise, is an American supercomputer manufacturer headquartered in Seattle, Washington. It also manufactures systems for data storage and analytics. Several Cray supercomputer systems are listed i ...

. The Twin Cities

Twin cities are a special case of two neighboring cities or urban centres that grow into a single conurbation – or narrowly separated urban areas – over time. There are no formal criteria, but twin cities are generally comparable in sta ...

also became a regional center for the arts, with cultural institutions such as the Guthrie Theater

The Guthrie Theater, founded in 1963, is a center for theater performance, production, education, and professional training in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The concept of the theater was born in 1959 in a series of discussions between Sir Tyrone Gut ...

, Minnesota Orchestra

The Minnesota Orchestra is an American orchestra based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Founded originally as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in 1903, the Minnesota Orchestra plays most of its concerts at Minneapolis's Orchestra Hall.

History

Em ...

, and Walker Art Center

The Walker Art Center is a multidisciplinary contemporary art center in the Lowry Hill neighborhood of Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. The Walker is one of the most-visited modern and contemporary art museums in the United States and, to ...

.

Native American inhabitation

Folsom Folsom may refer to:

People

* Folsom (surname)

Places in the United States

* Folsom, Perry County, Alabama

* Folsom, Randolph County, Alabama

* Folsom, California

* Folsom, Georgia

* Folsom, Louisiana

* Folsom, Missouri

* Folsom, New Jerse ...

types. Some of the earliest evidence of a sustained presence in the area comes from a site known as Bradbury Brook near Mille Lacs Lake

Mille Lacs Lake (also called Lake Mille Lacs or Mille Lacs) is a large but shallow lake in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It is located in the counties of Mille Lacs, Aitkin, and Crow Wing, roughly 75 miles north of the Minneapolis-St. Paul m ...

which was used around 7500 BC. Subsequently, extensive trading networks developed in the region. The body of an early resident known as " Minnesota Woman" was discovered in 1931 in Otter Tail County

Otter Tail County is a county in the U.S. state of Minnesota. As of the 2020 census, its population was 60,081. Its county seat is Fergus Falls. Otter Tail County comprises the Fergus Falls micropolitan statistical area. With 1,048 lakes i ...

. Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was de ...

places the age of the bones approximately 8000 years ago, approximately 7890 ±70 BP or near the end of the Eastern Archaic period. She had a conch shell from a snail species known as '' Busycon perversa'', which had previously only been known to exist in Florida.

Several hundred years later, the climate of Minnesota warmed significantly. As large animals such as mammoths

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

became extinct, native people changed their diet. They gathered nuts, berries, and vegetables, and they hunted smaller animals such as deer, bison, and birds. The stone tools found from this era became smaller and more specialized to use these new food sources. They also devised new techniques for catching fish, such as fish hooks, nets, and harpoons. Around 5000 BC, people on the shores of Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

(in Minnesota and portions of what is now Michigan, Wisconsin, and Canada) were the first on the continent to begin making metal tools. Pieces of ore with high concentrations of copper were initially pounded into a rough shape, heated to reduce brittleness, pounded again to refine the shape, and reheated. Edges could be made sharp enough to be useful as knives or spear points.

Archaeological evidence of Native American presence dates between 2,500 and 5,000 years ago at the

Archaeological evidence of Native American presence dates between 2,500 and 5,000 years ago at the Jeffers Petroglyphs

The Jeffers Petroglyphs site is an outcrop in southwestern Minnesota with pre-contact Native American petroglyphs. The petroglyphs are pecked into rock of the Red Rock Ridge, a -long Sioux quartzite outcrop that extends from Watonwan County, Minn ...

site in southwest Minnesota. The exposed sioux quartzite rock is dotted with several thousand petroglyphs

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

thought to date to the Late Archaic Period (3000 BC to 1000 BC). Around 700 BC, burial mound

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

s were first created, and the practice continued until the arrival of Europeans, when 10,000 to 11,000 such mounds dotted the state. The Hopewell burial mounds in Saint Paul are protected from invasive modern tourism.

Archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscapes ...

believe native peoples discovered the catlinite

Catlinite, also called pipestone, is a type of argillite (metamorphosed mudstone), usually brownish-red in color, which occurs in a matrix of Sioux Quartzite. Because it is fine-grained and easily worked, it is prized by Native Americans, pri ...

deposit at Pipestone over 3,000 years ago. Word of its existence spread and a quarry developed that was sacred ground to the native peoples across a vast area. When the French Voyageurs arrived in the region in the 1600s they learned of the quarry in their bartering with the indigenous peoples. In 1858, the same year Minnesota became a state, the Yankton Sioux Tribe signed the Yankton Treaty in which they gave up their lands in western Minnesota and South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

. However, section 8 of the treaty gave the Yankton nation a one mile square reservation at the quarry site. In 1893 the site was sold to the US Government and in 1937 FDR

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

signed the bill creating the Pipestone National Monument. Today the quarry remains active and is restricted exclusively to native Americans by treaty with the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational properti ...

. At present there are 23 tribal nations affiliated by treaty to the Monument based upon their historic ties with Pipestone.

By AD 800, wild rice

Wild rice, also called manoomin, Canada rice, Indian rice, or water oats, is any of four species of grasses that form the genus ''Zizania'', and the grain that can be harvested from them. The grain was historically gathered and eaten in both ...

became a staple crop in the region, and corn farther to the south. Within a few hundred years, the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, eart ...

reached into the southeast portion of the state, and large villages were formed. The Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, ...

Native American culture may have descended from some of the peoples of the Mississippian culture.

When Europeans first started exploring Minnesota, the region was inhabited primarily by tribes of Dakota, with the Ojibwa

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

(sometimes called Chippewa, or Anishinaabe) beginning to migrate westward into the state around 1700. (Other sources suggest the Ojibwe reached Minnesota by 1620 or earlier.) The economy of these tribes was chiefly based on hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

activities. There was also a small group of Ho-Chunk

The Ho-Chunk, also known as Hoocągra or Winnebago (referred to as ''Hotúŋe'' in the neighboring indigenous Iowa-Otoe language), are a Siouan-speaking Native American people whose historic territory includes parts of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iow ...

(Winnebago) Native Americans near Long Prairie, who later moved to a reservation in Blue Earth County in 1855.

At some early point, the Missouria moved south into what is now Missouri, the Menominee ceded much of their westernmost lands and withdrew closer to the region of Green Bay, Wisconsin, and the A'ani were pushed north and west by the Dakota and split into the Gros Ventre and the Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ba ...

. Later tribes who would inhabit the region include the Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakod ...

, who split from the Dakota and returned to Minnesota, but later also moved west as American settlers came to populate the region.

European exploration

In the late 1650s, Pierre Esprit Radisson and

In the late 1650s, Pierre Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers

Médard Chouart des Groseilliers (1618–1696) was a French explorer and fur trader in Canada. He is often paired with his brother-in-law Pierre-Esprit Radisson, who was about 20 years younger. The pair worked together in fur trading and explor ...

, while following the southern shore of Lake Superior (which would become northern Wisconsin), were probably the first Europeans to meet Dakota Native Americans . The north shore of the lake was explored in the 1660s. Among the first to do this was Claude Allouez

Claude Jean Allouez (June 6, 1622 – August 28, 1689) was a Jesuit missionary and French explorer of North America. He established a number of missions among the indigenous people living near Lake Superior.

Biography

Allouez was born in Sain ...

, a missionary on Madeline Island

''Madeline'' is a media franchise that originated as a series of children's books written and illustrated by Ludwig Bemelmans, an Austrian-American author. The books have been adapted into numerous formats, spawning telefilms, television series a ...

. He made an early map of the area in 1671.

Around this time, the Ojibwa Native Americans reached Minnesota as part of a westward migration. Having come from a region around Maine, they were experienced at dealing with European traders. They sold furs and purchased guns. Tensions rose between the Ojibwa and Dakota in the ensuing years.

In 1671, France signed a treaty with a number of tribes to allow trade. Shortly thereafter, French trader Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, arrived in the area and began trading with the local tribes. Du Lhut explored the western area of Lake Superior, near his namesake, the city of Duluth, and areas south of there. He helped to arrange a peace treaty between the Dakota and Ojibwa tribes in 1679.

Father

Father Louis Hennepin

Father Louis Hennepin, O.F.M. baptized Antoine, (; 12 May 1626 – 5 December 1704) was a Belgian Roman Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Recollet order (French: ''Récollets'') and an explorer of the interior of North Ameri ...

, with companions Michel Aco and Antoine Auguelle

Antoine Auguelle Picard du Gay (alternative spelling ''Augelle'', also referred to as Anthony Auguel) was a 17th-century French explorer. Born at Amiens in Picardy, Auguelle, along with Michel Aco, accompanied Father Louis Hennepin during his expl ...

(a.k.a. Picard Du Gay), headed north from the area of modern Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

after coming into that area with an exploration party headed by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (; November 22, 1643 – March 19, 1687), was a 17th-century French explorer and fur trader in North America. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, the Mississippi River, ...

. They were captured by a Dakota tribe in 1680. While with the tribe, they came across and named the Falls of Saint Anthony. Soon, Du Lhut was able to obtain through negotiation the release of Hennepin's party. Hennepin returned to Europe and wrote a book, ''Description of Louisiana'', published in 1683, about his travels; many portions, including the part about Saint Anthony Falls, were strongly embellished. As an example, he described the falls as having a drop of 50 to 60 feet (15–18 m), when they were really only about . Pierre-Charles Le Sueur

Pierre-Charles Le Sueur (c. 1657, Artois, France – 17 July 1704, Havana, Cuba) was a French fur trader and explorer in North America, recognized as the first known European to explore the Minnesota River valley.

Le Sueur came to Canada with ...

explored the Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

to the Blue Earth area around 1700. He thought the blue earth was a source of copper, and he told stories about the possibility of mineral wealth, but there actually was no copper in it.

Explorers searching for the fabled Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

and large inland seas in North America continued to pass through the state. In 1721, the French built Fort Beauharnois

Fort Beauharnois was a French fort, serving as a fur trading post and Catholic mission, built on the shores of Lake Pepin, a wide section of the upper Mississippi River, in 1727. The location chosen was on lowlands and the fort was rebuilt in 1 ...

on Lake Pepin

Lake Pepin is a naturally occurring lake on the Mississippi River on the border between the U.S. states of Minnesota and Wisconsin. It is located in a valley carved by the outflow of an enormous glacial lake at the end of the last Ice Age. The ...

. In 1731, the Grand Portage

Grand Portage National Monument is a United States National Monument located on the north shore of Lake Superior in northeastern Minnesota that preserves a vital center of fur trade activity and Anishinaabeg Ojibwe heritage. The area became one ...

trail was first traversed by a European, Pierre La Vérendrye

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

. He used a map written down on a piece of birch bark by Ochagach, an Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakod ...

guide. The North West Company

The North West Company was a fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in what is present-day Western Canada and Northwestern Ontario. With great weal ...

, which traded in fur and competed with the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

, was established along the Grand Portage in 1783–1784.

Jonathan Carver

Jonathan Carver (April 13, 1710 – January 31, 1780) was a captain in a Massachusetts colonial unit, explorer, and writer. After his exploration of the northern Mississippi valley and western Great Lakes region, he published an account of his exp ...

, a shoemaker from Massachusetts, visited the area in 1767 as part of another expedition. He and the rest of the exploration party were only able to stay for a relatively short period, due to lack of supplies. They headed back east to Fort Michilimackinac

Fort Michilimackinac was an 18th-century French, and later British, fort and trading post at the Straits of Mackinac; it was built on the northern tip of the lower peninsula of the present-day state of Michigan in the United States. Built aroun ...

, where Carver wrote journals about the trip, though others would later claim the stories were largely plagiarize

Plagiarism is the fraudulent representation of another person's language, thoughts, ideas, or expressions as one's own original work.From the 1995 '' Random House Compact Unabridged Dictionary'': use or close imitation of the language and thought ...

d. The stories were published in 1778, but Carver died before the book earned him much money. Carver County and Carver's Cave ( Wakan Tipi) are named for him.

In 1822 the Earl of Selkirk acquired a controlling interest in the Hudson Bay Company. Through the Company he acquired of land that today (2021) make up Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

and the northern portions of North Dakota and Minnesota. Until 1818 the Red River Valley

The Red River Valley is a region in central North America that is drained by the Red River of the North; it is part of both Canada and the United States. Forming the border between Minnesota and North Dakota when these territories were admitted ...

was considered part of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

, and several colonization plans were mounted to the region, such as the Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assinboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hudson's Bay ...

. The boundary where the Red River crossed the 49th parallel was not marked until 1823, when Stephen H. Long

Stephen Harriman Long (December 30, 1784 – September 4, 1864) was an American army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor. As an inventor, he is noted for his developments in the design of steam locomotives. He was also one of the most pro ...

conducted a survey expedition. When several hundred settlers abandoned the Red River Colony in the 1820s, they entered United States territory along the Red River Valley, going south to Fort Snelling. The region had been occupied by Métis people

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which derives ...

, the children of voyageurs and Native Americans, since the middle of the 17th century.

Several efforts were made to find the source of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

. The true source was found in 1832, when Henry Schoolcraft

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (March 28, 1793 – December 10, 1864) was an American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist, noted for his early studies of Native American cultures, as well as for his 1832 expedition to the source of the Mississippi R ...

was guided by a group of Ojibwa headed by ''Ozaawindib

''Ozaawindib'' ("Yellow Head" in English, recorded variously as Oza Windib, O-zaw-wen-dib, O-zaw-wan-dib, Ozawondib, etc.) (Ojibwe) was an early 19th century (fl. 1797-1832) male-bodied warrior. He had several husbands, at times wore attire typic ...

'' ("Yellow Head") to a lake in northern Minnesota. Schoolcraft named it Lake Itasca

Lake Itasca is a small glacial lake, approximately in area. Located in southeastern Clearwater County, in the Headwaters area of north central Minnesota, it is notable for being the headwater of the Mississippi River. The lake is in Itasca Sta ...

, combining the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

words ''veritas'' ("truth") and ''caput'' ("head"). The native name for the lake was ''Omashkooz'', meaning elk. Other explorers of the area include Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

in 1806, Major Stephen Long in 1817, and George William Featherstonhaugh

George William Featherstonhaugh ( /ˈfɪərstənhɔː/ '' FEER-stən-haw''; 9 April 1780, in London – 28 September 1866, in Le Havre) was a British-American geologist and geographer. He was one of the proposers of the Albany and Schenectady Ra ...

in 1835. Featherstonhaugh conducted a geological survey of the Minnesota River Valley

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ...

and wrote an account, entitled ''A Canoe Voyage up the Minnay Sotor''.

Joseph Nicollet scouted the area in the late 1830s, exploring and mapping the Upper Mississippi River

The Upper Mississippi River is the portion of the Mississippi River upstream of St. Louis, Missouri, United States, at the confluence of its main tributary, the Missouri River.

History

In terms of geologic and hydrographic history, the Upper ...

basin, the St. Croix River, and the land between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. He and John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

left their mark in the southwest part of the state, carving their names in the pipestone quarries near Winnewissa Falls (an area now part of Pipestone National Monument

Pipestone National Monument is located in southwestern Minnesota, just north of the city of Pipestone, Minnesota. It is located along the highways of U.S. Route 75, Minnesota State Highway 23 and Minnesota State Highway 30. The quarries are sac ...

, in Pipestone County).

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely trans ...

never explored the state, but he did help to make it popular. In 1855 he published ''The Song of Hiawatha

''The Song of Hiawatha'' is an 1855 epic poem in trochaic tetrameter by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow which features Native American characters. The epic relates the fictional adventures of an Ojibwe warrior named Hiawatha and the tragedy of hi ...

'', which contains references to many places in Minnesota. The story is based on Ojibwa legends carried back east by other explorers and traders (particularly those collected by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (March 28, 1793 – December 10, 1864) was an American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist, noted for his early studies of Native American cultures, as well as for his 1832 expedition to the source of the Mississippi ...

).

Territorial foundation and settlement

Land acquisition

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. This included what would become modern-day Saint Paul but only part of Minneapolis, along with the northeast, north-central, and east-central portions of the future state. The western portion of the state was part of Spanish Louisiana

Spanish Louisiana ( es, link=no, la Luisiana) was a governorate and administrative district of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1762 to 1801 that consisted of a vast territory in the center of North America encompassing the western basin of t ...

since the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762)

The Treaty of Fontainebleau was a secret agreement of 1762 in which the Kingdom of France ceded Louisiana (New France), Louisiana to Spain. The treaty followed the last battle in the French and Indian War in North America, the Battle of Signal Hill ...

. The wording of the treaty in the Minnesota area depended on landmarks reported by fur traders, who erroneously reported an "Isle Phelipeaux" in Lake Superior, a "Long Lake" west of the island, and the belief that the Mississippi River ran well into modern Canada. Most of the state—the area west of the Mississippi—was purchased in 1803 from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

. Parts of northern Minnesota were considered to be in Rupert's Land. The exact definition of the boundary between Minnesota and British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

was not addressed until the Anglo-American Convention of 1818

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international treaty signed in 1818 betw ...

, which set the U.S.–Canada border at the 49th parallel west of the Lake of the Woods

Lake of the Woods (french: Lac des Bois, oj, Pikwedina Sagainan) is a lake occupying parts of the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Manitoba and the U.S. state of Minnesota. Lake of the Woods is over long and wide, containing more than 14,5 ...

(except for a small chunk of land now dubbed the Northwest Angle

The Northwest Angle, known simply as the Angle by locals, and coextensive with Angle Township, is a pene-exclave of northern Lake of the Woods County, Minnesota. Except for surveying errors, it is the only place in the contiguous United Sta ...

). Border disputes east of Lake of the Woods continued until the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842.

During the first half of the 19th century, the northeastern portion of the state was a part of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

, then the Illinois Territory, then the Michigan Territory

The Territory of Michigan was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 30, 1805, until January 26, 1837, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Michigan. Detroit ...

, and finally the Wisconsin Territory

The Territory of Wisconsin was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 3, 1836, until May 29, 1848, when an eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Wisconsin. Belmont was ...

. The western and southern areas of the state, although theoretically part of the Wisconsin Territory from its creation in 1836, were not formally organized until 1838, when they became part of the Iowa Territory

The Territory of Iowa was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1838, until December 28, 1846, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Iowa. The remain ...

.

Establishment of Fort Snelling, Minneapolis and Saint Paul

Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

was the first U.S. military post in the state. The land for the fort encompassed the confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main stem); o ...

of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers and was acquired in 1805 by Lt. Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

. When concerns mounted about the fur trade in the area, construction of the fort began in 1819, and was completed in 1825, named after Colonel Josiah Snelling

Colonel Josiah Snelling (1782 – 20 August 1828) was the first commander of Fort Snelling, a fort located at the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers in Minnesota. He was responsible for the initial design and construction of the fo ...

.

Slaves Dred Scott and his wife were taken to the fort by their master, John Emerson. They lived at the fort and elsewhere in territories where slavery was prohibited. After Emerson's death, the Scotts argued that since they had lived in free territory, they were no longer slaves. The U.S. Supreme Court sided against the Scotts in Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

. Dred Scott Field, located just a short distance away in Bloomington, is named in the memory of Fort Snelling's significance in one of the most important legal decisions in U.S. history.

By 1851, treaties between Native American tribes and the U.S. government had opened much of Minnesota to settlement, so Fort Snelling no longer was a frontier outpost. It served as a training center for soldiers during the

By 1851, treaties between Native American tribes and the U.S. government had opened much of Minnesota to settlement, so Fort Snelling no longer was a frontier outpost. It served as a training center for soldiers during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

and later as the headquarters for the Department of Dakota. A portion has been designated as Fort Snelling National Cemetery 3

Fort Snelling National Cemetery is a United States National Cemetery located in the Fort Snelling Unorganized Territory adjacent to the historic

fort and Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport. It is the only National Cemetery in Minneso ...

where over 160,000 are interred. During World War II, the fort served as a training center for nearly 300,000 inductees. Fort Snelling is now a historic site operated by the Minnesota Historical Society

The Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) is a nonprofit educational and cultural institution dedicated to preserving the history of the U.S. state of Minnesota. It was founded by the territorial legislature in 1849, almost a decade before state ...

.

Fort Snelling was largely responsible for the establishment of the city of Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

. The fort garrison built roads, planted crops, and built a grist mill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separat ...

and a sawmill at Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony ( dak, italics=no, Owámniyomni, ) located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, is the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late 1 ...

. Later, Franklin Steele

Franklin Steele (1813 – September 10, 1880) was an early settler of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, of Scottish descent, Steele worked in the Lancaster post office as a young man, where he once met James Bucha ...

came to Fort Snelling as the post sutler. He established interests in lumbering as well as operated the ferries serving the fort from St. Paul and Mendota. When the Ojibwe signed a treaty ceding lands in 1837, Steele staked a claim to land on the east side of the Mississippi River adjacent to Saint Anthony Falls. In 1848, he built a sawmill at the falls, and the community of Saint Anthony developed along the east side of the falls. Steele told one of his employees, John H. Stevens, that land on the west side of the falls would make a good site for future mills. Since the land on the west side was still part of the military reservation, Stevens made a deal with Fort Snelling's commander. Stevens would provide free ferry service across the river in exchange for a tract of at the head of the falls. Stevens received the claim and built a house, the first house in Minneapolis, in 1850. In 1854, Stevens platted the city of Minneapolis on the west bank. Later, in 1872, Minneapolis absorbed the city of Saint Anthony.

The city of Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center ...

is also a Fort Snelling development. Squatter

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

s, mostly from the ill-fated Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assinboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hudson's Bay ...

in what is now Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

, established a camp near the fort. The commandant of Fort Snelling, Major Joseph Plympton, found their presence problematic because they were using resources that the fort required; timber, firewood and grazing lands around the fort. Plympton banned lumbering and evicted the squatters from the military reservation. As a result, they moved four miles downstream on the Mississippi River to Fountain cave. This location was not quite far enough for Plympton, so the squatters were forced out again. Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant, established a moonshine

Moonshine is high-proof liquor that is usually produced illegally. The name was derived from a tradition of creating the alcohol during the nighttime, thereby avoiding detection. In the first decades of the 21st century, commercial dist ...

trade there with both the soldiers and Sioux. The settlement got the name "Pig's Eye" when a customer at Parrant's tavern wrote a letter with "Pig's Eye" as the return address. The reply to that letter was delivered directly to the settlement. In 1840, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Dubuque sent Father Lucien Galtier

Lucien Galtier ( – February 21, 1866) was the first Roman Catholic priest who served in Minnesota. He was born in southern France in the town of Saint-Affrique, department of Aveyron. The year of his birth is somewhat uncertain, some sources cl ...

as a missionary to the settlement. Galtier built a small log church and dedicated it to Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

. The nearby steamboat landing took on the name "St. Paul's Landing", and by 1846, when a post office was opened, the area was known as St. Paul. Before white settlement, the Mdewakanton Sioux knew the area as ''Im-in-i-ja Ska'', meaning "White Rock", which describes the sandstone bluffs adjacent to Carver's Cave.

Minneapolis and Saint Paul are collectively known as the Twin Cities

Twin cities are a special case of two neighboring cities or urban centres that grow into a single conurbation – or narrowly separated urban areas – over time. There are no formal criteria, but twin cities are generally comparable in sta ...

. Minneapolis is the largest city in Minnesota, with a population of 429,954 in the 2020 census. Saint Paul is smaller with a population of 311,527 in 2020. Minneapolis-Saint Paul are the core of the MPLS metropolitan area with a population of 3,690,261 as of 2020, with a total state population of 5,706,494.

Early European settlement and development

Henry Hastings Sibley

Henry Hastings Sibley (February 20, 1811 – February 18, 1891) was a North American fur trade, fur trader with the American Fur Company, the first United States House of Representatives, U.S. Congressional representative for Minnesota Territor ...

built the first stone house in the Minnesota Territory in Mendota in 1838, along with other limestone buildings used by the American Fur Company

The American Fur Company (AFC) was founded in 1808, by John Jacob Astor, a German immigrant to the United States. During the 18th century, furs had become a major commodity in Europe, and North America became a major supplier. Several British ...

, which bought animal pelts at that location from 1825 to 1853. Another area of early economic development in Minnesota was the logging industry. Loggers found the white pine

''Pinus'', the pines, is a genus of approximately 111 extant tree and shrub species. The genus is currently split into two subgenera: subgenus ''Pinus'' (hard pines), and subgenus ''Strobus'' (soft pines). Each of the subgenera have been further ...

especially valuable, and it was plentiful in the northeastern section of the state and in the St. Croix River valley. Before railroads, lumbermen relied mostly on river transportation to bring logs to market, which made Minnesota's timber resources attractive. Towns like Pine City, Marine on St. Croix and Stillwater became important lumber centers fed by the St. Croix River, while Winona Winona, Wynona or Wynonna may refer to:

Places Canada

* Winona, Ontario

United States

* Winona, Arizona

* Winona, Indiana

* Winona Lake, Indiana

* Winona, Kansas

* Winona, Michigan

* Winona County, Minnesota

** Winona, Minnesota, the seat of ...

became an important lumber market because of its proximity to farms that were developing in the south of the state. The unregulated logging practices of the time and a severe drought took their toll in 1894, when the Great Hinckley Fire ravaged in the Hinckley

Hinckley is a market town in south-west Leicestershire, England. It is administered by Hinckley and Bosworth Borough Council. Hinckley is the third largest settlement in the administrative county of Leicestershire, after Leicester and Loughbo ...

and Sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

areas of Pine County, killing over 400 residents. The combination of logging and drought struck again in the Baudette Fire of 1910 and the Cloquet Fire of 1918.

Saint Anthony, on the east bank of the Mississippi River later became part of Minneapolis, and was an important lumber milling center supplied by the Rum River

The Rum River is a slow, meandering stream that connects Minnesota's Mille Lacs Lake with the Mississippi River. It runs for U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed October 5, 2 ...

. In 1848, businessman Franklin Steele built the first private sawmill on the Saint Anthony Falls, and more sawmills quickly followed. The oldest wood frame home still standing in Saint Anthony is the Ard Godfrey house, built in 1848, and lived in by Ard and Harriet Godfrey. The house of John H. Stevens, the first house on the west bank in Minneapolis, was moved several times, finally to Minnehaha Park

Minnehaha Park is a city park in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, and home to Minnehaha Falls and the lower reaches of Minnehaha Creek. Officially named Minnehaha Regional Park, it is part of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board syst ...

in south Minneapolis in 1896.

Minnesota Territory

On August 26, 1848, shortly after Wisconsin was admitted to the Union, a convention of sixty-one met in Stillwater to petition Congress to create a Minnesota Territory from the remainder of the Wisconsin and Iowa Territories. The delegate chosen to bring the convention's petition before Congress wasHenry Hastings Sibley

Henry Hastings Sibley (February 20, 1811 – February 18, 1891) was a North American fur trade, fur trader with the American Fur Company, the first United States House of Representatives, U.S. Congressional representative for Minnesota Territor ...

. Stephen A. Douglas (D), the chair of the Senate Committee on Territories, drafted the bill authorizing Minnesota Territory. He had envisioned a future for the upper Mississippi valley, so he was motivated to keep the area from being carved up by neighboring territories. In 1846, he prevented Iowa from including Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

and Saint Anthony Falls within its northern border. In 1847, he kept the organizers of Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

from including Saint Paul and Saint Anthony Falls. The Minnesota Territory

The Territory of Minnesota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1849, until May 11, 1858, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Minnesota and west ...

was established from the lands remaining from Iowa Territory

The Territory of Iowa was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1838, until December 28, 1846, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Iowa. The remain ...

and Wisconsin Territory

The Territory of Wisconsin was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 3, 1836, until May 29, 1848, when an eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Wisconsin. Belmont was ...

on March 3, 1849. The Minnesota Territory extended far into what is now North Dakota and South Dakota, to the Missouri River. There was a dispute over the shape of the state to be carved out of Minnesota Territory. An alternate proposal that was only narrowly defeated would have made the 46th parallel the state's northern border and the Missouri River its western border, thus giving up the whole northern half of the state in exchange for the eastern half of what later became South Dakota.

With Alexander Ramsey

Alexander Ramsey (September 8, 1815 April 22, 1903) was an American politician. He served as a Whig and Republican over a variety of offices between the 1840s and the 1880s. He was the first Minnesota Territorial Governor.

Early years and fa ...

(W) as the first governor of Minnesota Territory and Henry Hastings Sibley

Henry Hastings Sibley (February 20, 1811 – February 18, 1891) was a North American fur trade, fur trader with the American Fur Company, the first United States House of Representatives, U.S. Congressional representative for Minnesota Territor ...

(D) as the territorial delegate to the United States Congress. Ramsey lobbied Congress for funds to build five military roads in the Territory: Mendota/Fort Snelling to Wabasha, Point Douglas to Fort Ripley/Crow River Indian Agency, Mendota/Fort Snelling to the Missouri River, Point Douglas to Superior, and Fort Ripley Road to Long Prairie Indian Agency. The populations of Saint Paul and Saint Anthony swelled. Henry M. Rice (D), who replaced Sibley as the territorial delegate in 1853, worked in Congress to promote Minnesota interests. He lobbied for the construction of a railroad connecting Saint Paul and Lake Superior, with a link from Saint Paul to the Illinois Central

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also c ...

. Another military road would run from Fort Ridgely to South Pass, Nebraska Territory.

Statehood

In December 1856, Henry Mower Rice brought forward two bills in Congress: an enabling act that would allow Minnesota to form a state constitution, and a railroad land grant bill. Rice's enabling act defined a state containing both prairie and forest lands. The state was bounded on the south by Iowa, on the east by Wisconsin, on the north by Canada, and on the west by theRed River of the North

The Red River (french: rivière Rouge or ) is a river in the north-central United States and central Canada. Originating at the confluence of the Bois de Sioux and Otter Tail rivers between the U.S. states of Minnesota and North Dakota, it fl ...

and the Bois de Sioux River

The Bois de Sioux River () drains Lake Traverse, the southernmost body of water in the Hudson Bay watershed of North America. It is a tributary of the Red River of the North and defines part of the western border of the U.S. state of Minnesota, ...

, Lake Traverse, Big Stone Lake

Big Stone Lake ( dak, Íŋyaŋ Tháŋka Bdé) is a long, narrow freshwater lake and reservoir on the border between western Minnesota and northeastern South Dakota in the United States.

Description

The lake covers , stretching from end to end ...

, and then a line extending due south to the Iowa border. Rice made this motion based on Minnesota's population growth.

At the time, tensions between the northern and the southern United States were growing, in a series of conflicts that eventually resulted in the American Civil War. There was little debate in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, but when Stephen A. Douglas introduced the bill in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

, it caused a firestorm of debate. Northerners saw their chance to add two senators to the side of the free states, while Southerners were sure that they would lose power. Many senators offered polite arguments that the population was too sparse and that statehood was premature. Senator John Burton Thompson

John Burton Thompson (December 14, 1810 – January 7, 1874) was a United States Representative and Senator from Kentucky.

Early life

Born near Harrodsburg, Kentucky, Thompson completed preparatory studies and studied law. He was admitted to t ...

of Kentucky, in particular, argued that new states would cost the government too much for roads, canals, forts, and lighthouses. Although Thompson and 21 other senators voted against statehood, the enabling act was passed on February 26, 1857.

After the enabling act was passed, territorial legislators had a difficult time writing a state constitution. A constitutional convention was assembled in July 1857, but Republicans and Democrats were deeply divided. In fact, they formed two separate constitutional conventions and drafted two separate constitutions. Eventually, the two groups formed a conference committee and worked out a common constitution. The divisions continued, though, because Republicans refused to sign a document that had Democratic signatures on it, and vice versa. One copy of the constitution was written on white paper and signed only by Republicans, while the other copy was written on blue-tinged paper and signed by Democrats. These copies were signed on August 29, 1857. An election was called on October 13, 1857, where Minnesota residents would vote to approve or disapprove the constitution. The constitution was approved by 30,055 voters, while 571 rejected it.

The state constitution was sent to the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

for ratification in December 1857. The approval process was drawn out for several months while Congress debated over issues that had stemmed from the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

. Southerners had been arguing that the next state should be pro-slavery, so when Kansas submitted the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution (1859) was the second of four proposed constitutions for the state of Kansas. Named for the city of Lecompton where it was drafted, it was strongly pro-slavery. It never went into effect.

History Purpose

The Lecompton C ...

, the Minnesota statehood bill was delayed. After that, Northerners feared that Minnesota's Democratic delegation would support slavery in Kansas. Finally, after the Kansas question was settled and after Congress decided how many representatives Minnesota would get in the House of Representatives, the bill passed. The eastern half of the Minnesota Territory, under the boundaries defined by Rice, became the country's 32nd state on May 11, 1858. The western part remained unorganized until its incorporation into the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of N ...

on March 2, 1861.

Military conflicts

Civil War

When news broke in 1861 thatFort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

had been fired on, Gov. Ramsey

Ramsey may refer to:

Geography British Isles

* Ramsey, Cambridgeshire, a small market town in England

* Ramsey, Essex, a village near Harwich, England

** Ramsey and Parkeston, a civil parish formerly called just "Ramsey"

* Ramsey, Isle of Man, t ...

happened to be in Washington D.C. and rushed to give President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

Minnesota's support. The soldiers of the 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment

The 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment was the very first group of volunteers the Union received in response to the South's assault of Fort Sumter at the beginning of the United States Civil War. Minnesota's Governor Alexander Ramsey offered 1000 m ...

were the first soldiers offered to fight for the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

. Minnesota had more than 24,000 troops serve in the Civil War, about one-seventh of the state's population in 1860. Nearly 3,000 lost their lives to battlefield wounds or disease.

The 1st Minnesota changed the course of the decisive Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

. Desperate to make time for reinforcements to arrive, on Gettysburg's second day, July 2, 1863, General Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

sent the 262 members of 1st Minnesota to halt a Confederate assault. They succeeded in capturing a Confederate flag

The flags of the Confederate States of America have a history of three successive designs during the American Civil War. The flags were known as the "Stars and Bars", used from 1861 to 1863; the "Stainless Banner", used from 1863 to 1865; and ...

and held the line for the Union, but all but 47 of them were killed, wounded, or captured. The regiment lost 17 more facing Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge (July 3, 1863), also known as the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge, was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee against Major General George G. Meade's Union positions on the last day of the ...

to end the battle the next day. Lt. Col. William F. Fox wrote that "the percentage of loss in the First Minnesota, Gibbon's Division swithout an equal in the records of modern warfare". Explaining his role in ordering the First Minnesota in, Hancock is quoted, "There is no more gallant deed recorded in history ..."

By the end of the war, Minnesota had raised 11 regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

s of infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

, two sharpshooter

A sharpshooter is one who is highly proficient at firing firearms or other projectile weapons accurately. Military units composed of sharpshooters were important factors in 19th-century combat. Along with " marksman" and "expert", "sharpshooter" ...

units, and some cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

.

Dakota War of 1862

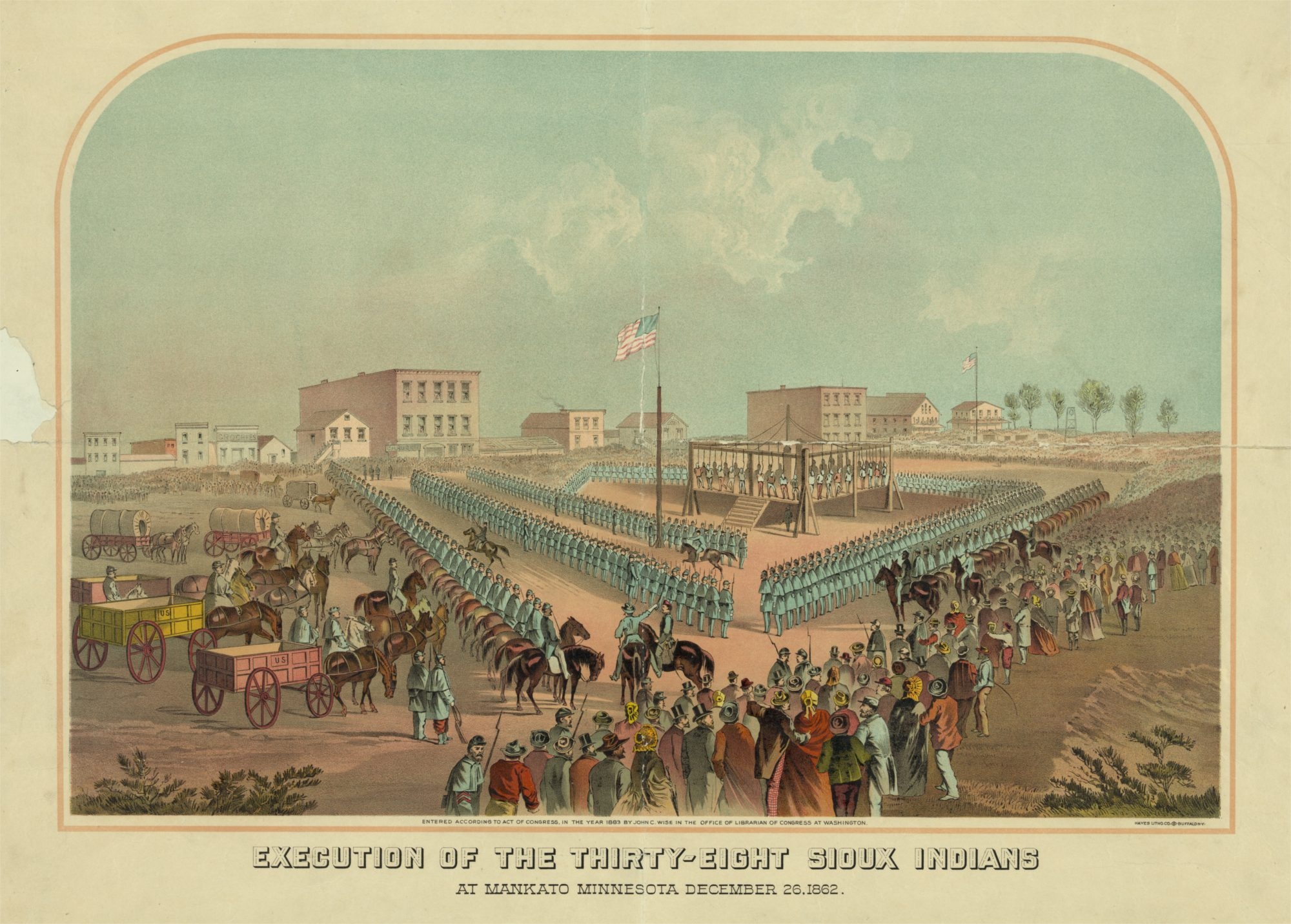

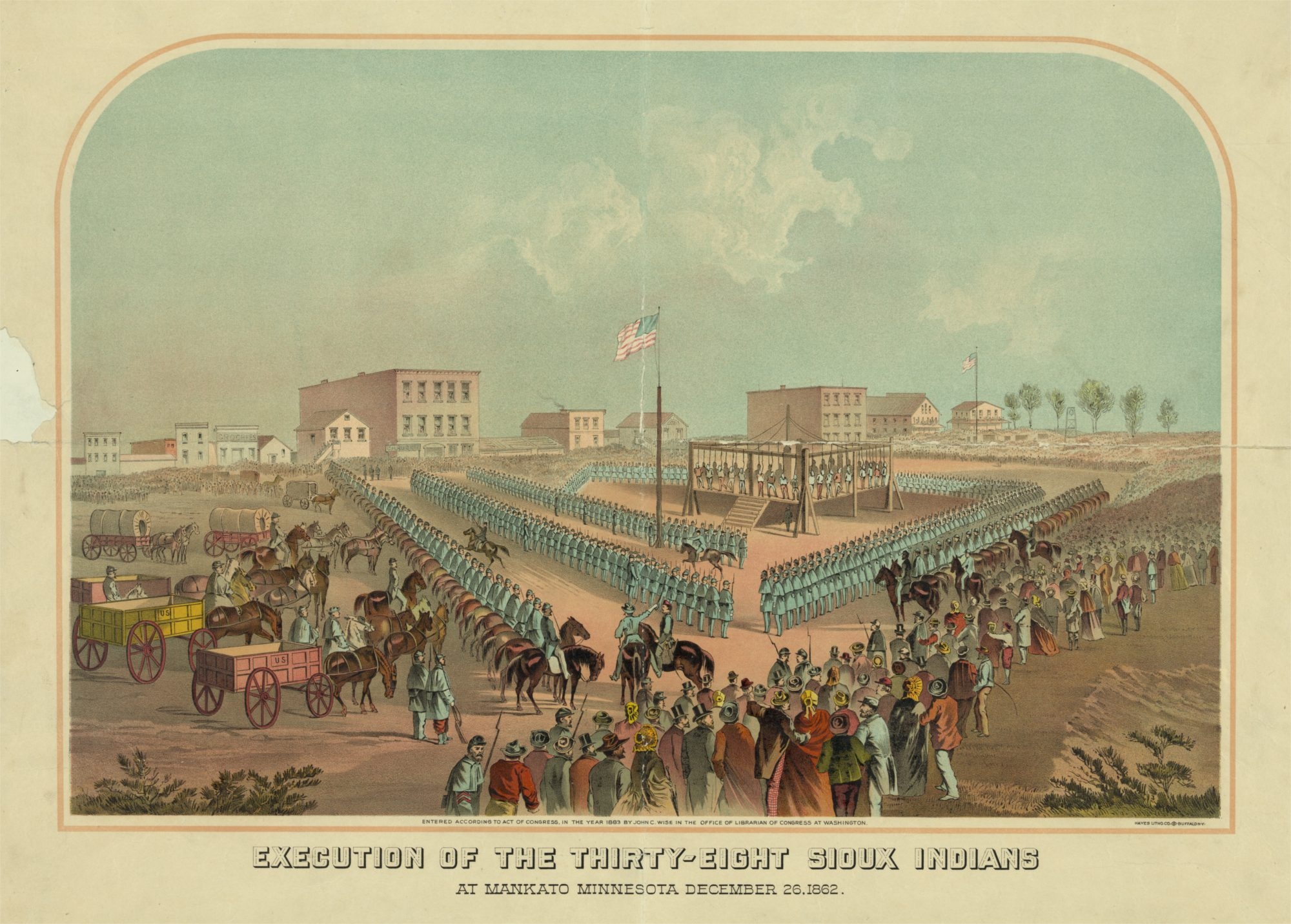

During the Civil War, the state faced another crisis as the Dakota War of 1862 broke out. As white settlement pressed in, the Dakota were destitute, even starving because of loss of habitat of huntable game. Dakota had signed the

During the Civil War, the state faced another crisis as the Dakota War of 1862 broke out. As white settlement pressed in, the Dakota were destitute, even starving because of loss of habitat of huntable game. Dakota had signed the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux () was signed on July 23, 1851, at Traverse des Sioux in Minnesota Territory between the United States government and the Upper Dakota Sioux bands. In this land cession treaty, the Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota ban ...

and Treaty of Mendota

The Treaty of Mendota was signed in Mendota, Minnesota on August 5, 1851 between the United States federal government and the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Dakota people of Minnesota.

The agreement was signed near Pilot Knob on the south bank of the M ...

in 1851, negotiating with corrupt officials who enriched themselves. They were given a strip of land of north and south of the Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

, but were later forced to sell the northern half. In 1862, crop failures left the Dakota with food shortages, and government money was delayed.

The conflict was ignited when four young Dakota men, searching for food, killed a family of white settlers on August 17. That night, a faction of Little Crow's Dakota decided to try and drive all settlers out of the Minnesota River valley. In the weeks that followed, Dakota warriors attacked and killed hundreds of settlers, causing thousands to flee the area. The ensuing battles at the Lower Sioux Agency

The Lower Sioux Agency, or Redwood Agency, was the federal administrative center for the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation in what became Redwood County, Minnesota, United States. It was the site of the Battle of Lower Sioux Agency on August 18, 186 ...

, Fort Ridgely

Fort Ridgely was a frontier United States Army outpost from 1851 to 1867, built 1853–1854 in Minnesota Territory. The Sioux called it Esa Tonka. It was located overlooking the Minnesota river southwest of Fairfax, Minnesota. Half of the ...

, Birch Coulee, and Wood Lake punctuated a six-week war, which ended with the trial of 425 Indians for their participation in the war. Of this number, 303 were convicted and sentenced to death. Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple

Henry Benjamin Whipple (February 15, 1822 – September 16, 1901) was the first Episcopal bishop of Minnesota, who gained a reputation as a humanitarian and an advocate for Native Americans.

Summary of his life

Born in Adams, New York, he was ...

pled to President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

for clemency, and the death sentences of all but 39 Sioux were reduced to prison terms. On December 26, 1862, 38 Sioux were hanged in the largest mass execution in the United States.

Many of the remaining Dakota Indians, including non-combatants

Non-combatant is a term of art in the law of war and international humanitarian law to refer to civilians who are not taking a direct part in hostilities; persons, such as combat medics and military chaplains, who are members of the belligeren ...

were confined in a prison camp at Pike Island over the winter of 1862–1863, where between 125 and 300 died of disease. They were later exiled to the Crow Creek Reservation

The Crow Creek Indian Reservation ( dak, Khąǧí wakpá okášpe, '' lkt, Kȟaŋğí Wakpá Oyáŋke''), home to Crow Creek Sioux Tribe ( dak, Khąǧí wakpá oyáte) is located in parts of Buffalo, Hughes, and Hyde counties on the east ban ...

, and then to a reservation near Niobrara, Nebraska

Niobrara (; Omaha: ''Ní Ubthátha'' ''Tʰáⁿwaⁿgthaⁿ'' , meaning "water spread-out village")Dorsey, James Owen (1890)''The Cegiha Language: Contributions to North American Ethnology'' 4. Washington: US Department of the Interior: Governmen ...

. A small number of Dakota Indians returned to Minnesota in the 1880s and established small communities near Granite Falls, Morton, Prior Lake

Prior Lake is an exurban city southwest of Minneapolis seated next to Savage and Shakopee in Scott County in the state of Minnesota. Surrounding the shores of Lower and Upper Prior Lake, the city lies south of the Minnesota River in an area kn ...

, and Red Wing.

World War I

When the United States entered theGreat war

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Minnesota's National Guard was activated for federal service. To fill that void the State created the Minnesota Home Guard

Home guard is a title given to various military organizations at various times, with the implication of an emergency or reserve force raised for local defense.

The term "home guard" was first officially used in the American Civil War, starting w ...