History of Minneapolis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut explored the Minnesota area in 1680 on a mission to extend French dominance over the area. While exploring the St. Croix River area, he got word that some other explorers had been held captive. He arranged for their release. The prisoners included Michel Aco,

French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut explored the Minnesota area in 1680 on a mission to extend French dominance over the area. While exploring the St. Croix River area, he got word that some other explorers had been held captive. He arranged for their release. The prisoners included Michel Aco,

A settlement on the east bank of the Mississippi near St. Anthony Falls was envisioned in the 1830s by Joseph Plympton, who became commander of Fort Snelling in 1837. He made a more accurate survey of the reservation lands and transmitted a map to the War Department delimiting about within the reservation. He cleverly drew the boundary line to exclude certain parts of the east bank that had been part of the 1805 cession to

A settlement on the east bank of the Mississippi near St. Anthony Falls was envisioned in the 1830s by Joseph Plympton, who became commander of Fort Snelling in 1837. He made a more accurate survey of the reservation lands and transmitted a map to the War Department delimiting about within the reservation. He cleverly drew the boundary line to exclude certain parts of the east bank that had been part of the 1805 cession to

After Franklin Steele obtained proper title to his land, he turned his energies to building a sawmill at St. Anthony Falls. He obtained financing and built a dam on the east channel of the river between Hennepin Island and

After Franklin Steele obtained proper title to his land, he turned his energies to building a sawmill at St. Anthony Falls. He obtained financing and built a dam on the east channel of the river between Hennepin Island and

On the west side of the river, John H. Stevens platted a townsite in 1854. He laid out

On the west side of the river, John H. Stevens platted a townsite in 1854. He laid out

The

The

Most of the early industrial development in Minneapolis was tied to

Most of the early industrial development in Minneapolis was tied to

The two cities were later pushed toward merger by a disaster that nearly wiped out the falls. The geological formation of the area consisted of a hard, thin layer of

The two cities were later pushed toward merger by a disaster that nearly wiped out the falls. The geological formation of the area consisted of a hard, thin layer of

The ''St. Anthony Express'' newspaper predicted in 1855 that, "The time is not distant when Minnesota, with the superiority of her soil and seasons for wheat culture, and her unparalleled water power for manufacturing flour, will export largely of this article. ... our mills will turn out wheat, superior in quality and appearance to any now manufactured in the West." By 1876, eighteen flour mills had been built on the west side of the river below the falls. The first mills used traditional technology of

The ''St. Anthony Express'' newspaper predicted in 1855 that, "The time is not distant when Minnesota, with the superiority of her soil and seasons for wheat culture, and her unparalleled water power for manufacturing flour, will export largely of this article. ... our mills will turn out wheat, superior in quality and appearance to any now manufactured in the West." By 1876, eighteen flour mills had been built on the west side of the river below the falls. The first mills used traditional technology of

In 1882, the first central station (supplying multiple users)

In 1882, the first central station (supplying multiple users)

Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

is the largest city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

by population in the U.S. state of Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

, and the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US ...

of Hennepin County. The origin and growth of the city was spurred by the proximity of Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

, the first major United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

military presence in the area, and by its location on Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony ( dak, italics=no, Owámniyomni, ) located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, is the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late 1 ...

, which provided power for sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logging, logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes ...

s and flour mills

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separated ...

.

Fort Snelling was established in 1819, at the confluence of the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

rivers, and soldiers began using the falls for waterpower. When land became available for settlement, two towns were founded on either side of the falls: Saint Anthony, on the east side, and Minneapolis, on the west side. The two towns later merged into one city in 1872. Early development focused on sawmills, but flour mills eventually became the dominant industry. This industrial development fueled the development of railroads and banks, as well as the foundation of the Minneapolis Grain Exchange

The Minneapolis Grain Exchange (MGEX) is a commodities and futures exchange of grain products. It was formed in 1881 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States as a regional cash marketplace to promote fair trade and to prevent trade abuses in ...

. Through innovations in milling techniques, Minneapolis became a world-leading center of flour production, earning the name "Mill City". As the city grew, the culture developed through its churches, arts institutions, the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

, and a famous park system designed by Horace Cleveland

Horace William Shaler Cleveland (December 16, 1814 – December 5, 1900) was an American landscape architect. His approach to natural landscape design can be seen in projects such as the Grand Rounds in Minneapolis; Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Conco ...

and Theodore Wirth

Theodore Wirth (1863–1949) was instrumental in designing the Minneapolis system of parks. Swiss-born, he was widely regarded as the dean of the local parks movement in America. The various titles he was given included administrator of pa ...

.

Although the sawmills and the flour

Flour is a powder made by grinding raw grains, roots, beans, nuts, or seeds. Flours are used to make many different foods. Cereal flour, particularly wheat flour, is the main ingredient of bread, which is a staple food for many cul ...

mills are long gone, Minneapolis remains a regional center in banking and industry. The two largest milling companies, General Mills

General Mills, Inc., is an American multinational manufacturer and marketer of branded processed consumer foods sold through retail stores. Founded on the banks of the Mississippi River at Saint Anthony Falls in Minneapolis, the company or ...

and the Pillsbury Company, now merged under the General Mills name, still remain prominent in the Twin Cities area. The city has rediscovered the riverfront, which now hosts parkland, the Mill City Museum

Mill City Museum is a Minnesota Historical Society museum in Minneapolis. It opened in 2003 built in the ruins of the Washburn "A" Mill next to Mill Ruins Park on the banks of the Mississippi River. The museum focuses on the founding and grow ...

, and the Guthrie Theater

The Guthrie Theater, founded in 1963, is a center for theater performance, production, education, and professional training in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The concept of the theater was born in 1959 in a series of discussions between Sir Tyrone Gut ...

.

Early European exploration

Minneapolis grew up aroundSaint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony ( dak, italics=no, Owámniyomni, ) located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, is the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late 1 ...

, the only waterfall

A waterfall is a point in a river or stream where water flows over a vertical drop or a series of steep drops. Waterfalls also occur where meltwater drops over the edge of a tabular iceberg or ice shelf.

Waterfalls can be formed in several ...

on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

and the end of the commercially navigable section of the river until locks were installed in the 1960s.

French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut explored the Minnesota area in 1680 on a mission to extend French dominance over the area. While exploring the St. Croix River area, he got word that some other explorers had been held captive. He arranged for their release. The prisoners included Michel Aco,

French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut explored the Minnesota area in 1680 on a mission to extend French dominance over the area. While exploring the St. Croix River area, he got word that some other explorers had been held captive. He arranged for their release. The prisoners included Michel Aco, Antoine Auguelle

Antoine Auguelle Picard du Gay (alternative spelling ''Augelle'', also referred to as Anthony Auguel) was a 17th-century French explorer. Born at Amiens in Picardy, Auguelle, along with Michel Aco, accompanied Father Louis Hennepin during his expl ...

, and Father Louis Hennepin

Father Louis Hennepin, O.F.M. baptized Antoine, (; 12 May 1626 – 5 December 1704) was a Belgian Roman Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Recollet order (French: ''Récollets'') and an explorer of the interior of North Ameri ...

, a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priest and missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

. On that expedition, Father Hennepin explored the falls and named them after his patron saint, Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua ( it, Antonio di Padova) or Anthony of Lisbon ( pt, António/Antônio de Lisboa; born Fernando Martins de Bulhões; 15 August 1195 – 13 June 1231) was a Portuguese Catholic priest and friar of the Franciscan Order. He was bo ...

. He published a book in 1683 entitled ''Description of Louisiana'', describing the area to interested Europeans. As time went on, he developed a tendency to exaggerate. A 1691 edition of the book described the falls as having a drop of fifty or sixty feet, when they only had a drop of . Hennepin may have been including nearby rapids in his estimate, as the current total drop in river level over the series of dams is .

The city's land was acquired by the United States in a series of treaties and purchases negotiated with the Mdewakanton

The Mdewakanton or Mdewakantonwan (also spelled ''Mdewákhaŋthuŋwaŋ'' and currently pronounced ''Bdewákhaŋthuŋwaŋ'') are one of the sub-tribes of the Isanti (Santee) Dakota ( Sioux). Their historic home is Mille Lacs Lake (Dakota: ''Mde W� ...

band of the Dakota and separately with European nations. England claimed the land east of the Mississippi and France, then Spain, and again France claimed the land west of the river. In 1787 land on the east side of the river became part of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

and in 1803 the west side became part of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

, both claimed by the United States. In 1805, Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

purchased two tracts of land from the Dakota Indians. One tract was located at the mouth of the St. Croix River, while a second, larger tract ran from the confluence of the Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

and Mississippi Rivers to St. Anthony Falls, with a width of east and west of the river. In return, he distributed about $200 in trading goods and sixty gallons of liquor, and promised a further payment from the United States government. The United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

eventually approved a payment of $2,000.

Fort Snelling and St. Anthony Falls

Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

was established in 1819 to extend United States jurisdiction over the area and to allay concerns about British fur traders in the area. The soldiers initially camped at a site on the south side of the Minnesota River, but conditions were hard there and nearly a fifth of the soldiers died of scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease, disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, ch ...

in the winter of 1819–1820. They later moved their camp to Camp Coldwater in May 1820. Much of the military's activity was conducted there while the fort was built. Camp Coldwater, the site of a cold, clear, flowing spring, was also considered sacred by the native Dakota.

The soldiers needed to supply the fort, so they built roads and planted vegetables, wheat, and hay, and raised cattle. They also made the first weather recordings in the area. A lumber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, w ...

mill and a grist mill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separat ...

were built on the falls in 1822 to supply the fort.

A settlement on the east bank of the Mississippi near St. Anthony Falls was envisioned in the 1830s by Joseph Plympton, who became commander of Fort Snelling in 1837. He made a more accurate survey of the reservation lands and transmitted a map to the War Department delimiting about within the reservation. He cleverly drew the boundary line to exclude certain parts of the east bank that had been part of the 1805 cession to

A settlement on the east bank of the Mississippi near St. Anthony Falls was envisioned in the 1830s by Joseph Plympton, who became commander of Fort Snelling in 1837. He made a more accurate survey of the reservation lands and transmitted a map to the War Department delimiting about within the reservation. He cleverly drew the boundary line to exclude certain parts of the east bank that had been part of the 1805 cession to Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

. His plan was to stake a pre-emption claim at the falls. However, Franklin Steele also had plans to stake a claim. On July 15, 1838, word reached Fort Snelling that a treaty between the United States and the Dakota and Ojibwa had been ratified, ceding land between the St. Croix River and the Mississippi Rivers. Steele rushed off to the falls, built a shanty, and marked off boundary lines. Plympton's party arrived the next morning, but they were too late to claim the most desirable land. Plympton claimed some less desirable land near Steele's claim, as did other settlers such as Pierre Bottineau

Pierre Bottineau (January 1, 1817 – July 26, 1895) was a Minnesota frontiersman.'Compendium of History and Biography of Central and Northern Minnesota,' G. A. Ogle & Company: 1904, Biographical Sketch of Pierre Bottineau, pg. 144

Known as ...

, Joseph Rondo, Samuel Findley, and Baptiste Turpin. Steele went on to build a dam at the falls and built a sawmill that cut logs from the Rum River

The Rum River is a slow, meandering stream that connects Minnesota's Mille Lacs Lake with the Mississippi River. It runs for U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed October 5, 2 ...

area.

The Dakota were hunters and gatherers and soon found themselves in debt to fur traders. Pressed by a whooping cough outbreak, loss of buffalo, deer, and bear, and loss of forests to logging, in 1851 in the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux () was signed on July 23, 1851, at Traverse des Sioux in Minnesota Territory between the United States government and the Upper Dakota Sioux bands. In this land cession treaty, the Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota ban ...

, the Mdewakanton sold the remaining land west of the river, allowing settlement in 1852.

Franklin Steele also had a clever plan to obtain land on the west side of the falls. He suggested to his associated Colonel John H. Stevens that he should bargain with the War Department to obtain some land. Stevens agreed to operate a ferry

A ferry is a ship, watercraft or amphibious vehicle used to carry passengers, and sometimes vehicles and cargo, across a body of water. A passenger ferry with many stops, such as in Venice, Italy, is sometimes called a water bus or water ta ...

service across the Mississippi in exchange for a claim of just above the government mills. The government approved this bargain, and Stevens built his house in the winter of 1849–1850. The house was the first permanent dwelling on the west bank in the area that became Minneapolis. A few years later, the amount of land controlled by the fort was reduced with an order from U.S. President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

, and rapid settlement followed. The village of Minneapolis soon sprung up on the southwest bank of the river.

City pioneers

St. Anthony

After Franklin Steele obtained proper title to his land, he turned his energies to building a sawmill at St. Anthony Falls. He obtained financing and built a dam on the east channel of the river between Hennepin Island and

After Franklin Steele obtained proper title to his land, he turned his energies to building a sawmill at St. Anthony Falls. He obtained financing and built a dam on the east channel of the river between Hennepin Island and Nicollet Island

Nicollet Island is an island in the Mississippi River just north of Saint Anthony Falls in central Minneapolis, Minnesota. According to the United States Census Bureau the island has a land area of and a 2000 census population of 144 persons. T ...

, along with a sawmill equipped with two up-and-down saws. His partner Daniel Stanchfield, a lumberman who had moved to Minnesota, dispatched crews up the Mississippi River to begin cutting lumber. The sawmill began cutting lumber in September 1848. In October 1848, Steele enlisted Ard Godfrey to supervise the mill at a salary of $1500 per year. Steele platted a townsite in 1849 and gave it the name "St. Anthony". The town quickly grew with workers. In addition to the first sawmill and several others that followed, a grist mill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separat ...

was built in 1851. By 1855, the town had approximately 3000 people, and it was incorporated as a city. Godfrey's house, built in 1848, was purchased by the Hennepin County Territorial Pioneers' Association and moved to Chute Square. The house was surveyed in 1934 by the Historic American Buildings Survey

Heritage Documentation Programs (HDP) is a division of the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) responsible for administering the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), and Historic American Landscapes ...

.

Minneapolis

Washington Avenue Washington Avenue may refer to:

United States

* Washington Avenue (Miami Beach) in Miami Beach, Florida

* Washington Avenue (Milford Mill, Maryland)

* Washington Avenue (Towson, Maryland)

* Washington Avenue (Minneapolis), a major street in Minne ...

parallel to the river, with other streets running parallel to and perpendicular to Washington. He later questioned his decision, thinking he should have run the streets directly east–west and north–south, but it ended up aligning nicely with the plat of St. Anthony. The wide, straight streets, with Washington and Hennepin Avenue

Hennepin Avenue is a major street in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. It runs from Lakewood Cemetery (at West 36th Street), north through the Uptown District of Southwest Minneapolis, through the Virginia Triangle, the former "Bottleneck" ...

being wide and the others being wide, contrasted with Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

's streets that were wide.

Before its incorporation, the city was known by several different names. The Dakota name for Minneapolis is ''Bdeóta Othúŋwe'' ('Many Lakes City'). The ''St. Paul Pioneer'' dubbed it facetiously "All Saints" anticipating that the town might absorb its neighbors St. Paul and St. Anthony. First west-bank settler John H. Stevens preferred "Hennepin" for the town and "Snelling" for the county. It was called "Lowell" for its water features, "Addiesville" or "Adasville" for a daughter of settler Charles Hoag, "Winona" by those who wished to preserve indigenous language, and "Brooklyn". "Albion" was recorded by the newly organized county government but a majority of residents rejected that name. The city's first schoolmaster, Hoag was searching for indigenous syllables, when he stumbled on "Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

" and was led by the twenty four small lake

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much large ...

s that are now within the city limits. In the ''St. Anthony Express,'' Hoag proposed "Minnehapolis," with a silent ''h,'' to combine the Dakota word for waterfall, ''Mníȟaȟa,'' and the Greek word for city, . ''Express'' editor George Bowman and Daniel Payne dropped the ''h'', leaving out the ''hah,'' to create ''Minneapolis,'' meaning 'city of the falls'.

The Minnesota Territorial Legislature recognized Saint Anthony as a town in 1855 and Minneapolis in 1856. Boundaries were changed and Minneapolis was incorporated as a city in 1867. Minneapolis and Saint Anthony joined in 1872. Minneapolis changed more than 100 road names in 1873, including deduplication of names between it and the former Saint Anthony.

Transportation

The

The Hennepin Avenue Bridge

The Hennepin Avenue Bridge is the structure that carries Hennepin County State Aid Highway 52, Hennepin Avenue, across the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, Minnesota, at Nicollet Island. Officially, it is the Father Louis Hennepin Bridge, in hon ...

, a suspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck is hung below suspension cables on vertical suspenders. The first modern examples of this type of bridge were built in the early 1800s. Simple suspension bridges, which lack vertical ...

that was the first bridge built over the full width of the Mississippi River, was built in 1854 and dedicated on January 23, 1855. The bridge had a span of , a roadway of , and was built at a cost of $36,000. The toll was five cents for pedestrians and twenty-five cents for horsedrawn wagons.

The early settlers of Minnesota were anxiously seeking railroad transportation, but insufficient capital was available after the Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

. Rails were finally built in Minnesota in 1862, when the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad built its first of track from the Phalen Creek area in St. Paul to a stop just short of St. Anthony Falls. The railroad continued building track from Minneapolis to Elk River in 1864 and to St. Cloud in 1866, and from Minneapolis west to Howard Lake in 1867 and Willmar in 1869. Meanwhile, the Minnesota Central, an early predecessor of the Milwaukee Road

The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (CMStP&P), often referred to as the "Milwaukee Road" , was a Class I railroad that operated in the Midwest and Northwest of the United States from 1847 until 1986.

The company experienced ...

, built a line from Minneapolis to Fort Snelling in 1865. The railroad gradually extended to Faribault, Owatonna, and Austin

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the seat and largest city of Travis County, with portions extending into Hays and Williamson counties. Incorporated on December 27, 1839, it is the 11th-most-populous city ...

. It crossed the Iowa border and met up with the McGregor & Western line. This connection gave Minneapolis rail service to Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee i ...

via Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin

Prairie du Chien () is a city in and the county seat of Crawford County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 5,506 at the 2020 census. Its ZIP Code is 53821.

Often referred to as Wisconsin's second oldest city, Prairie du Chien was est ...

, with through service beginning on October 14, 1867.

A streetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport a ...

system in the Minneapolis area took shape in 1875, when the Minneapolis Street Railway company began service with horse-drawn cars. Under the leadership of Thomas Lowry, the company merged with the St. Paul Railway Company and took the name Twin City Rapid Transit. By 1889, when electrification began, the system had grown to .

Business and industry

Most of the early industrial development in Minneapolis was tied to

Most of the early industrial development in Minneapolis was tied to St. Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony ( dak, italics=no, Owámniyomni, ) located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, is the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late ...

and the power it provided. Between 1848 and 1887, Minneapolis led the nation in sawmilling. In 1856, the mills produced 12 million board feet

The board foot or board-foot is a unit of measurement for the volume of lumber in the United States and Canada. It equals the volume of a length of a board, one foot wide and thick.

Board foot can be abbreviated as FBM (for "foot, board measure" ...

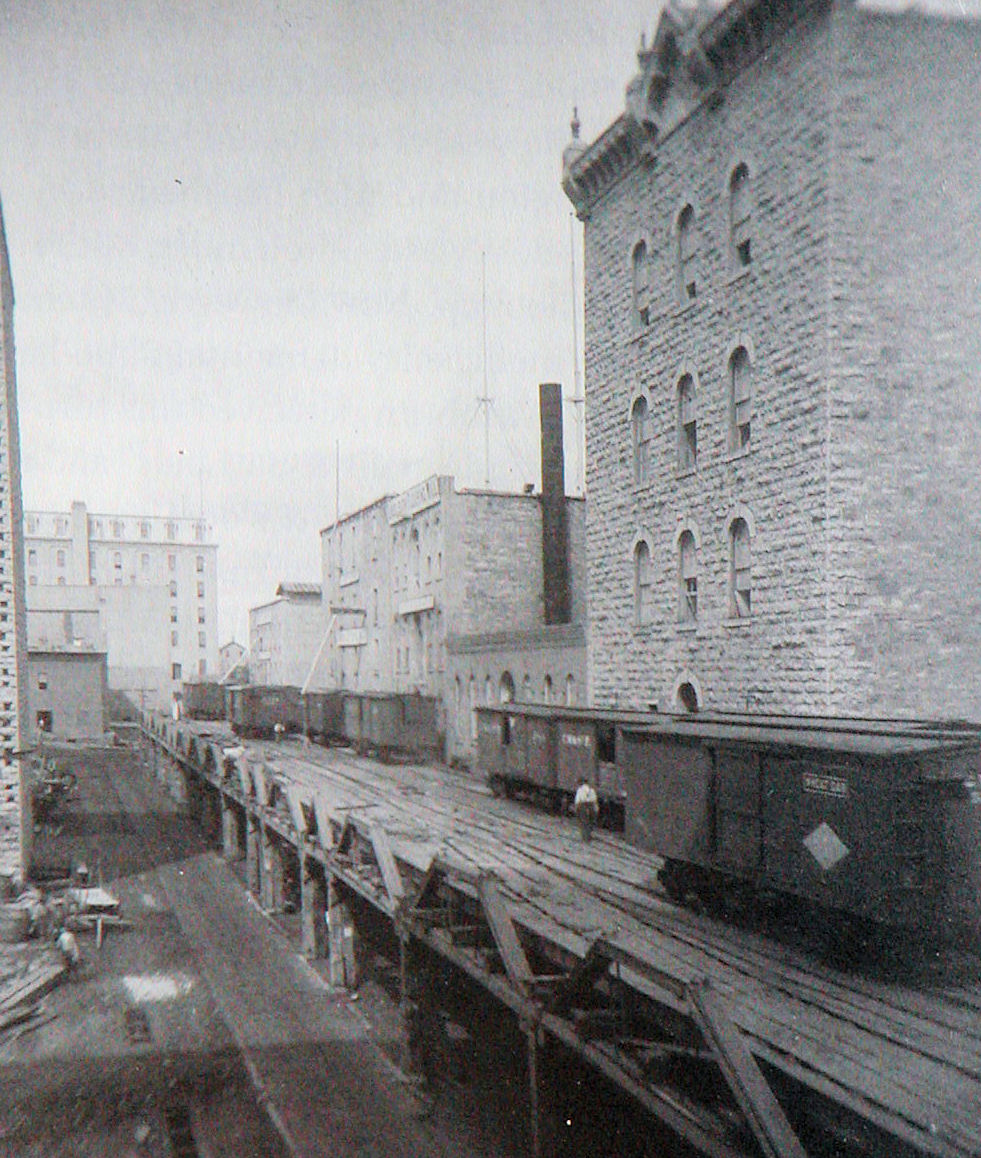

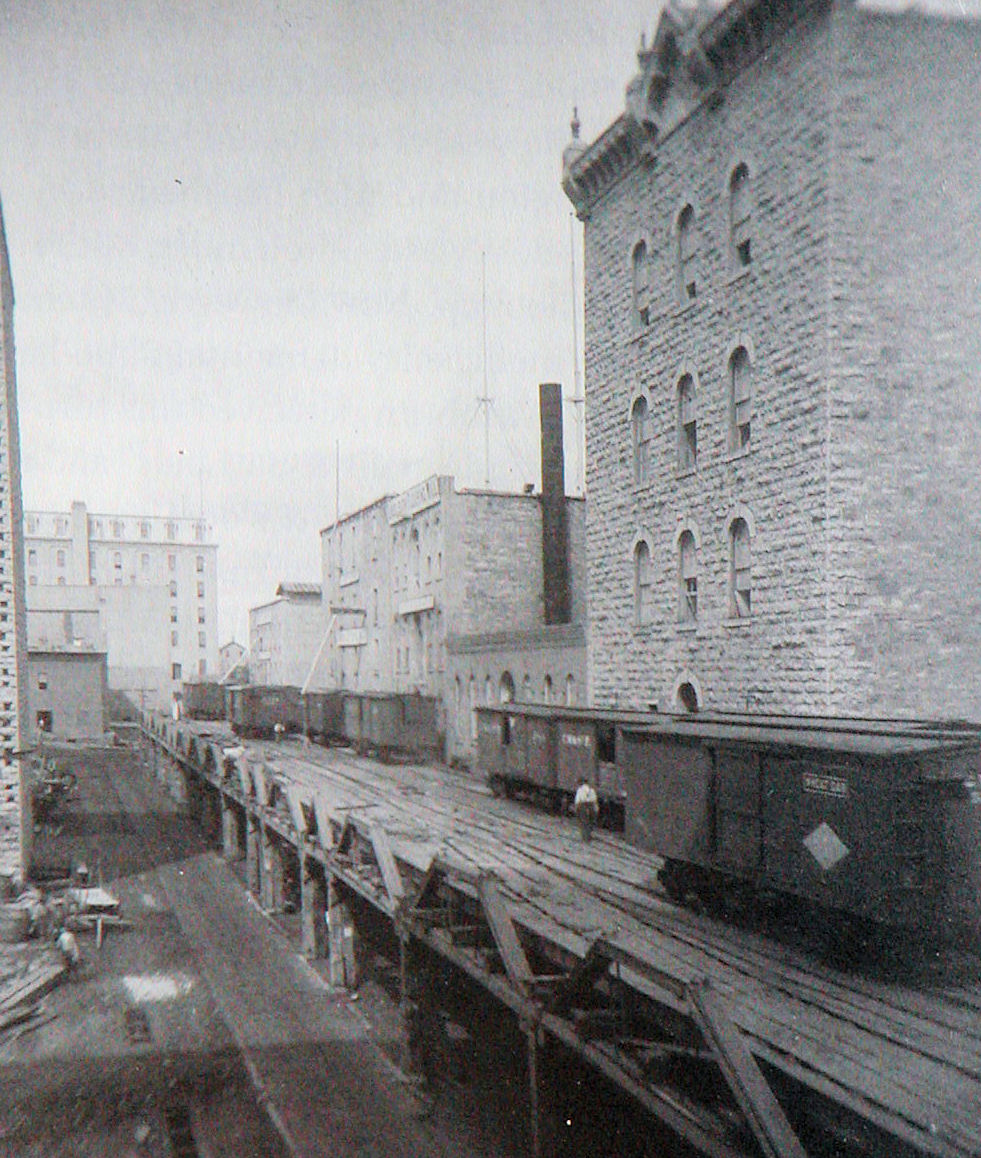

(28,000 m³) of lumber. That total had risen to about 91,000,000 board feet (215,000 m³) in 1869, and 960,000,000 board feet (2,270,000 m³) in 1899. During the peak of this activity, at least 13 sawmills were operating on the falls. The sawmills also supported related industries such as mills that planed and smoothed the lumber; factories that built sashes, doors, and windows; and manufacturers of shingles and wooden buckets.

The flour milling industry, dating back to the Fort Snelling government mill, later eclipsed the lumber industry in the value of its finished product. Flour production stood at in 1860, rising to in 1869. Cadwallader C. Washburn's imposing mill, built in 1866, was six stories high and promoted as the largest mill west of Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

. Other prominent industries at the falls included foundries, machine shops, and textile mills.

During this time, St. Anthony, on the east side, was separate from Minneapolis, on the west side. As a result of inferior management of the water power, St. Anthony found its manufacturing district declining. Some people and organizations started to talk about merging the two cities. A citizens' committee recommended merging the two cities in 1866, but a vote on this issue was rejected in 1867. Minneapolis incorporated as a city in 1867. The two cities found themselves competing with St. Paul, which had a larger population, the head of navigation of the Mississippi River, and more access to railroads.

In 1886 Richard Warren Sears started a mail-order watch business in Minneapolis, calling it "R.W. Sears Watch Company," before relocating the business to Chicago and later founding Sears, Roebuck and Co.

Sears, Roebuck and Co. ( ), commonly known as Sears, is an American chain of department stores founded in 1892 by Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck and reincorporated in 1906 by Richard Sears and Julius Rosenwald, with what began ...

, more commonly known as Sears.

Threatened collapse of St. Anthony Falls

The two cities were later pushed toward merger by a disaster that nearly wiped out the falls. The geological formation of the area consisted of a hard, thin layer of

The two cities were later pushed toward merger by a disaster that nearly wiped out the falls. The geological formation of the area consisted of a hard, thin layer of limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

overlaying a soft sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

formation. As the sandstone eroded away, large blocks of limestone would fall off causing the falls to progress upstream. The expansion of milling and industry at the falls accelerated the process of erosion. If the fragile limestone cap ever eroded away completely, the falls would turn into a rapids that would no longer provide water power. The Eastman tunnel was a tailrace tunnel being excavated in the sandstone from below the falls, under Hennepin Island, under the limestone cap, to Nicollet Island. In October 4, 1869 a hole in the limestone cap over the tunnel broke through as the tunnel neared Nicollet Island. The torrent of water blasted Hennepin Island and threatened to destroy the falls. Attempts to plug the hole were partially successful. The fix was a concrete dike (wall) built by the Corps of Engineers just upstream from the falls all the way across the river from just under the limestone cap down as much as 40 feet (12 m). Progression of the falls upstream was a separate problem, and was stopped by the Corps finishing a wooden apron (later replaced by concrete) creating a spillway to protect the edge of the falls and underlying sandstone. The Corps also built low dams above the falls to keep the limestone wet, as drying increased weathering. This work assisted by the Corps was eventually completed in 1884. The federal government spent $615,000 on this effort, while the two cities spent $334,500. Possibly as a result of the bonding needed to rehabilitate the falls, the cities of St. Anthony and Minneapolis merged on April 9, 1872.

Development of flour milling

The ''St. Anthony Express'' newspaper predicted in 1855 that, "The time is not distant when Minnesota, with the superiority of her soil and seasons for wheat culture, and her unparalleled water power for manufacturing flour, will export largely of this article. ... our mills will turn out wheat, superior in quality and appearance to any now manufactured in the West." By 1876, eighteen flour mills had been built on the west side of the river below the falls. The first mills used traditional technology of

The ''St. Anthony Express'' newspaper predicted in 1855 that, "The time is not distant when Minnesota, with the superiority of her soil and seasons for wheat culture, and her unparalleled water power for manufacturing flour, will export largely of this article. ... our mills will turn out wheat, superior in quality and appearance to any now manufactured in the West." By 1876, eighteen flour mills had been built on the west side of the river below the falls. The first mills used traditional technology of millstone

Millstones or mill stones are stones used in gristmills, for grinding wheat or other grains. They are sometimes referred to as grindstones or grinding stones.

Millstones come in pairs: a wikt:convex, convex stationary base known as the ''be ...

s that would pulverize the grain and grind as much flour as possible in one pass. This system worked best for winter wheat

Winter wheat (usually '' Triticum aestivum'') are strains of wheat that are planted in the autumn to germinate and develop into young plants that remain in the vegetative phase during the winter and resume growth in early spring. Classificatio ...

, which was sown in the fall and resumed its growth in the spring. However, the harsh winter conditions of the upper Midwest

The Upper Midwest is a region in the northern portion of the U.S. Census Bureau's Midwestern United States. It is largely a sub-region of the Midwest. Although the exact boundaries are not uniformly agreed-upon, the region is defined as referring ...

did not lend themselves to the production of winter wheat, since the deep frosts and lack of snow cover killed the crop. Spring wheat, which could be sown in the spring and reaped in the summer, was a more dependable crop. However, conventional milling techniques did not produce a desirable product, since the harder husks of spring wheat kernels fractured between the grindstones. The gluten

Gluten is a structural protein naturally found in certain cereal grains. Although "gluten" often only refers to wheat proteins, in medical literature it refers to the combination of prolamin and glutelin proteins naturally occurring in all grai ...

and starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human die ...

in the flour could not be mixed completely, either, and the flour would turn rancid. Minneapolis milling companies solved this problem by inventing the middlings purifier, which made it possible to separate the husks from the flour earlier in the milling process. They also developed a gradual-reduction process, where grain was pulverized between a series of rollers made of porcelain, iron, or steel. This process resulted in "patent" flour, which commanded almost double the price of "bakers" or "clear" flour, which it replaced. The Washburn mill attempted to monopolize these techniques, but Pillsbury and other companies lured employees away from Washburn and were able to duplicate the process.

Although the flour industry grew steadily, one major event caused a disturbance in the production of flour. On May 2, 1878, the Washburn "A" Mill

Mill City Museum is a Minnesota Historical Society museum in Minneapolis. It opened in 2003 built in the ruins of the Washburn "A" Mill next to Mill Ruins Park on the banks of the Mississippi River. The museum focuses on the founding and grow ...

exploded when grain dust ignited. The explosion, known as the Great Mill Disaster

The Great Mill Disaster (also known as the Washburn A Mill explosion) occurred in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, in 1878. The disaster resulted in 18 deaths. The explosion occurred on the evening of Thursday, May 2, 1878, when an accumu ...

, killed eighteen workers and destroyed one-third of the capacity of the milling district, as well as other nearby businesses and residences. By the end of the year, though, seventeen mills were back in operation, including the rebuilt Washburn "A" Mill and others that had been completely rebuilt. The millers also took the opportunity to rebuild with new technology such as dust collection systems. The largest mill on the east side of the river was the Pillsbury "A" Mill, built in 1880–1881 and designed by local architect LeRoy S. Buffington. The Pillsbury Company wanted a building that was beautiful as well as functional. The seven-story building had stone walls six feet thick at the base tapering to eighteen inches at the top. With improvements and additions over the years, it became the world's largest flour mill. The Pillsbury "A" Mill is now a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places liste ...

, along with the Washburn "A" Mill.

In 1891, Northwestern Consolidated Milling Company was formed, consolidating many of the smaller mills into one corporate entity. Between 1880 and 1930, Minneapolis led the nation in flour production, earning it the nickname "Mill City". Minneapolis surpassed Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

as the world's leading flour miller in 1884, and production stood at about annually in 1890. In 1900, Minneapolis mills were grinding 14.1 percent of the nation's grain, and in 1915–16, flour production hit its peak at annually.

Hydroelectric power

In 1882, the first central station (supplying multiple users)

In 1882, the first central station (supplying multiple users) hydroelectric

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined an ...

power plant in the United States was built at the falls on Upton Island. The Brush Electric Company, headed by Charles F. Brush, supplied the equipment, which included five generators. The electricity was transmitted via four circuits to shops on Washington Avenue Washington Avenue may refer to:

United States

* Washington Avenue (Miami Beach) in Miami Beach, Florida

* Washington Avenue (Milford Mill, Maryland)

* Washington Avenue (Towson, Maryland)

* Washington Avenue (Minneapolis), a major street in Minne ...

. The power plant turned on the lights on September 5, 1882, just ahead of the Vulcan Street Plant

The Vulcan Street Plant was the first Edison hydroelectric central station.Appleton, Wisconsin, which started generating electricity on September 30. The company competed with the Minneapolis Gas Light Company, which later became Minnegasco and is now part of CenterPoint Energy.

In 1895,

James J. Hill eventually reorganized the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad as the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad, which later became the Great Northern Railway. The Manitoba line had two lines leading to the

James J. Hill eventually reorganized the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad as the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad, which later became the Great Northern Railway. The Manitoba line had two lines leading to the

The Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1881 as a market to trade grain. It helped farmers by ensuring that they got the best prices possible for their

The Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1881 as a market to trade grain. It helped farmers by ensuring that they got the best prices possible for their

The

The

The first park in Minneapolis was land donated to the city in 1857, but it took about 25 years for the community to take a major interest in its parks. The Minneapolis Board of Trade and other civic leaders pressed the Minnesota Legislature for assistance. On February 27, 1883, the Legislature authorized the city to form a park district and to levy taxes. The initial vision was to create a number of boulevards, based on the design concepts of

The first park in Minneapolis was land donated to the city in 1857, but it took about 25 years for the community to take a major interest in its parks. The Minneapolis Board of Trade and other civic leaders pressed the Minnesota Legislature for assistance. On February 27, 1883, the Legislature authorized the city to form a park district and to levy taxes. The initial vision was to create a number of boulevards, based on the design concepts of

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church was founded in 1854. It is the oldest church in Minneapolis in continuous use. The church was originally built by the First Universalist Society, and later became a

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church was founded in 1854. It is the oldest church in Minneapolis in continuous use. The church was originally built by the First Universalist Society, and later became a  The Basilica of Saint Mary was constructed between 1907 and 1915 on land that was formerly a farm, then a

The Basilica of Saint Mary was constructed between 1907 and 1915 on land that was formerly a farm, then a

In response, companies such as the Washburn-Crosby Company and Pillsbury began marketing their brands specifically to consumers. Washburn-Crosby branded their flour "Gold Medal", in recognition of a prize won in 1880, and advertised with the slogan "Eventually – Why Not Now?" Pillsbury countered with their slogan, "Because Pillsbury's Best", incorporating their brand name "Pillsbury's Best". Washburn-Crosby invented the character

In response, companies such as the Washburn-Crosby Company and Pillsbury began marketing their brands specifically to consumers. Washburn-Crosby branded their flour "Gold Medal", in recognition of a prize won in 1880, and advertised with the slogan "Eventually – Why Not Now?" Pillsbury countered with their slogan, "Because Pillsbury's Best", incorporating their brand name "Pillsbury's Best". Washburn-Crosby invented the character

Humphrey first ran for

Humphrey first ran for

From about 200,000 in the 1900 Census, Minneapolis soared to its highest population recorded in 1950 of over 521,000 people. The main growth of the city was in part due to an organized private streetcar system. With 140 million passengers by 1920, the streetcars ran down important roads extending from Downtown Minneapolis. Neighborhood residential development out of the core mostly dates around the turn of the century as a result of this system. This growth also allowed Minneapolis to annex land from neighboring villages and townships which subsequently pushed the incorporation of today's inner ring suburbs.

The streetcar system was built by Twin City Rapid Transit and operated efficiently through 1949, with a program of reinvesting their profits into system improvements. However, in 1949, New York investor Charles Green gained control of the system, halted the rebuilding program, and announced a goal of completely converting the system to buses by 1958. These policies alienated the public and he was ousted in 1951, but his successor, Fred Ossanna, continued to cut service and replace the system with buses. On June 19, 1954, the last streetcar took its run. A photo taken in 1954 shows James Towley handing Fred Ossanna a check while one of the streetcars burned in the background. Later on, it was discovered that Ossanna and associates had plundered the streetcar system for personal gain. A small section of the line between Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet is now operated by the

From about 200,000 in the 1900 Census, Minneapolis soared to its highest population recorded in 1950 of over 521,000 people. The main growth of the city was in part due to an organized private streetcar system. With 140 million passengers by 1920, the streetcars ran down important roads extending from Downtown Minneapolis. Neighborhood residential development out of the core mostly dates around the turn of the century as a result of this system. This growth also allowed Minneapolis to annex land from neighboring villages and townships which subsequently pushed the incorporation of today's inner ring suburbs.

The streetcar system was built by Twin City Rapid Transit and operated efficiently through 1949, with a program of reinvesting their profits into system improvements. However, in 1949, New York investor Charles Green gained control of the system, halted the rebuilding program, and announced a goal of completely converting the system to buses by 1958. These policies alienated the public and he was ousted in 1951, but his successor, Fred Ossanna, continued to cut service and replace the system with buses. On June 19, 1954, the last streetcar took its run. A photo taken in 1954 shows James Towley handing Fred Ossanna a check while one of the streetcars burned in the background. Later on, it was discovered that Ossanna and associates had plundered the streetcar system for personal gain. A small section of the line between Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet is now operated by the

Downtown Minneapolis was the hub of business and financial activity. The Minneapolis City Hall (which also served as the Hennepin County Courthouse at the time) was the tallest building in Minneapolis from its construction in 1888 until 1929. A municipal ordinance instituted in 1890 restricted buildings to a height of , later raised to . The construction of the First National – Soo Line Building in 1915, with a height of , caused concerns among the real estate industry, so the 125-foot (twelve story) limit was reimposed at the request of the Minneapolis Civic and Commerce Association.

The twenty-seven story Rand Tower, built in 1929, was the next major challenger to the height limit. The thirty-two story Foshay Tower, also built in 1929, was the highest building in Minneapolis until 1971. Its builder, Wilbur Foshay, wanted a tower built along the lines of the

Downtown Minneapolis was the hub of business and financial activity. The Minneapolis City Hall (which also served as the Hennepin County Courthouse at the time) was the tallest building in Minneapolis from its construction in 1888 until 1929. A municipal ordinance instituted in 1890 restricted buildings to a height of , later raised to . The construction of the First National – Soo Line Building in 1915, with a height of , caused concerns among the real estate industry, so the 125-foot (twelve story) limit was reimposed at the request of the Minneapolis Civic and Commerce Association.

The twenty-seven story Rand Tower, built in 1929, was the next major challenger to the height limit. The thirty-two story Foshay Tower, also built in 1929, was the highest building in Minneapolis until 1971. Its builder, Wilbur Foshay, wanted a tower built along the lines of the  Kasota building in 1927 Gateway District.

The Gateway district, centered around the intersection of Hennepin and

Kasota building in 1927 Gateway District.

The Gateway district, centered around the intersection of Hennepin and

While the destruction of the Gateway district left a large gap in downtown Minneapolis, other developments would reshape it and transform the skyline. One of these developments was the building of the

While the destruction of the Gateway district left a large gap in downtown Minneapolis, other developments would reshape it and transform the skyline. One of these developments was the building of the

As industry and railroads left the Mississippi riverfront, people gradually became aware that the riverfront could be a destination for living, working, and shopping. The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board acquired land along the river banks, including much of

As industry and railroads left the Mississippi riverfront, people gradually became aware that the riverfront could be a destination for living, working, and shopping. The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board acquired land along the river banks, including much of

By the 21st century, Minneapolis was home to some of the largest racial disparities in the United States. The city's population of people of color and Indigenous people fared worse than the city's white population for many measures of well-being, such as health outcomes, academic achievement, income, and homeownership. As a result of discriminatory policies and racism throughout the city's history, racial disparities were described as the most significant issue facing Minneapolis in the first decades of the 21st century.

In the 2010s, several deaths of black men in Minneapolis and the metropolitan region by police officers brought issues of structural racism to the city's forefront. In 2015, the

By the 21st century, Minneapolis was home to some of the largest racial disparities in the United States. The city's population of people of color and Indigenous people fared worse than the city's white population for many measures of well-being, such as health outcomes, academic achievement, income, and homeownership. As a result of discriminatory policies and racism throughout the city's history, racial disparities were described as the most significant issue facing Minneapolis in the first decades of the 21st century.

In the 2010s, several deaths of black men in Minneapolis and the metropolitan region by police officers brought issues of structural racism to the city's forefront. In 2015, the

online

* * * * * * * Murray, Shannon. "Making a Model Metropolis: Boosterism, Reform, and Urban Design in Minneapolis, 1880-1920" (PhD dissertation, U of Calgary, 2015) doi:10.11575/PRISM/2681

online

* Nathanson, Iric. ''Minneapolis in the Twentieth Century: The Growth of an American City'' (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010)

excerpt

* * Pennefeather, Shannon, ed. ''Mill City: A Visual History of the Minneapolis Mill District.'' (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003) * Palmer, Bryan D. ''Revolutionary teamsters: The Minneapolis truckers’ strikes of 1934'' (Brill, 2013). * * Schmid, Calvin Fisher. ''Social saga of two cities: an ecological and statistical study of social trends in Minneapolis and St. Paul'' (Bureau of social research, The Minneapolis council of social agencies, 1937). * Shutter, Marion Daniel, ed. ''History of Minneapolis: Gateway to the Northwest'' (Biographies vol 3 1923

online

* Walker, Charles Rumford. ''American City: A Rank and File History of Minneapolis'' (U of Minnesota Press, 1937). * * * * Wills, Jocelyn. ''Boosters, Hustlers, and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849-1883'' (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005). * Wingerd, Mary Lethert. "Separated at Birth: The Sibling Rivalry of Minneapolis and St. Paul," ''OAH'' (February 2007)

*

online

Part 1

an

Part 2

Retrieved on February 10, 2008.

{{good article Minneapolis–Saint Paul

William de la Barre William de la Barre (April 15, 1849 in Vienna – March 24, 1936 in Minneapolis) was an Austrian-born civil engineer who developed a new process for milling wheat into flour, using energy-saving steel rollers at the Washburn-Crosby Mills (now kn ...

began building a lower dam, downriver from the falls. His objective was to build a hydroelectric plant that would sell energy to Twin City Rapid Transit, which was then using steam power to generate electricity. The dam was completed on March 20, 1897. Later, in 1906, he began construction of the Hennepin Island Hydroelectric Plant

The Hennepin Island Hydroelectric Plant is at St. Anthony Falls in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It has historically been an important part of St. Anthony Falls Hydroelectric Development. The plant is currently operated by Northern States Power/ Xcel ...

. The plant was leased to Minneapolis General Electric, which sublet the plant to Twin City Rapid Transit. Minneapolis General Electric later became Northern States Power Company, which is now known as Xcel Energy

Xcel Energy Inc. is an American utility holding company based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, serving more than 3.7 million electric customers and 2.1 million natural gas customers in Colorado, Texas, and New Mexico in 2019. It consists of four oper ...

.

Railroads

The development of sawmills and flour mills at the falls spurred demand for railroad service to Minneapolis. In 1868, Minneapolis was only served by a spur from St. Paul, from the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, and by the fledgling St. Paul and Pacific Railroad. Minneapolis millers found that railroads based inMilwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee i ...

and Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

were favoring their cities by diverting wheat from Minneapolis mills. In response, the owners of several Minneapolis mills chartered the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway, which would connect the Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad through Minneapolis to the Iowa border. Meanwhile, Jay Cooke took control of the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad in 1871 with the goal of aggregating it into the Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, wh ...

. Bad economic conditions caused the Panic of 1873, and the Northern Pacific had to relinquish control of the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad and the Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad.

James J. Hill eventually reorganized the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad as the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad, which later became the Great Northern Railway. The Manitoba line had two lines leading to the

James J. Hill eventually reorganized the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad as the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad, which later became the Great Northern Railway. The Manitoba line had two lines leading to the Red River Valley

The Red River Valley is a region in central North America that is drained by the Red River of the North; it is part of both Canada and the United States. Forming the border between Minnesota and North Dakota when these territories were admitted ...

, giving it access to wheat-growing regions, and it served several mills in Minneapolis. The Manitoba's small passenger station at Minneapolis had become inadequate, so Hill decided to build a new depot that he expected to share with other railroads. Since the Manitoba's mainline ran on the east side of the Mississippi, a new bridge across the river was needed to reach the station. The result was the Stone Arch Bridge

An arch bridge is a bridge with abutments at each end shaped as a curved arch. Arch bridges work by transferring the weight of the bridge and its loads partially into a horizontal thrust restrained by the abutments at either side. A viaduct (a ...

, completed in 1883. The Minneapolis Union Depot was opened for passenger service on April 25, 1885.

Meanwhile, the Milwaukee Road expanded their presence in Minneapolis with a "Short Line" connection from St. Paul to Minneapolis in 1880 and through the acquisition of the Hastings and Dakota Railroad, which had a line going west from Minneapolis to Montevideo

Montevideo () is the capital and largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . Montevideo is situated on the southern co ...

, Ortonville, and into Aberdeen, South Dakota

Aberdeen ( Lakota: ''Ablíla'') is a city in and the county seat of Brown County, South Dakota, United States, located approximately northeast of Pierre. The city population was 28,495 at the 2020 census, making it the third most populous ci ...

. They also built a large railyard and shops on Hiawatha Avenue just north of Lake Street, and a large depot on Washington Avenue.

The Minneapolis, Sault Ste. Marie & Atlantic Railway got its start in 1883, with a goal of serving Atlantic ports via Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan and bypassing Chicago altogether.

Other businesses

The Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1881 as a market to trade grain. It helped farmers by ensuring that they got the best prices possible for their

The Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1881 as a market to trade grain. It helped farmers by ensuring that they got the best prices possible for their wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, oats, and corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. The ...

, since the usual supply and demand curves were skewed by similar harvest times across the region. In 1883, they introduced its first futures contract

In finance, a futures contract (sometimes called a futures) is a standardized legal contract to buy or sell something at a predetermined price for delivery at a specified time in the future, between parties not yet known to each other. The asset ...

for hard red spring wheat. In 1947, the organization was renamed the Minneapolis Grain Exchange

The Minneapolis Grain Exchange (MGEX) is a commodities and futures exchange of grain products. It was formed in 1881 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States as a regional cash marketplace to promote fair trade and to prevent trade abuses in ...

, since the term "chamber of commerce

A chamber of commerce, or board of trade, is a form of business network. For example, a local organization of businesses whose goal is to further the interests of businesses. Business owners in towns and cities form these local societies to ...

" had become synonymous with organizations that lobbied for business and social issues.

The flour milling industry also spurred the growth of banking in the Minneapolis area. Mills required capital for investments in their plants and machinery and for their ongoing operations. By the early 20th century, Minneapolis was known as "the financial center of the Northwest".

Cultural institutions

Education

The

The University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

was charted by the state legislature in 1851, seven years before Minnesota became a state, as a preparatory school. The school was forced to close during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

because of financial difficulties, but with support from John S. Pillsbury, it reopened in 1867. William Watts Folwell became the first president of the university in 1869. The university granted its first two Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

degrees in 1873, and awarded its first Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

degree in 1888. From its beginnings in the St. Anthony area, the university eventually grew into a large campus on the east bank of the Mississippi, along with its campus in St. Paul and the addition of a West Bank campus in the 1960s.

DeLaSalle High School

DeLaSalle High School is a Catholic, college preparatory high school in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It is located on Nicollet Island.

History

DeLaSalle opened in 1900 and has been administered by the De La Salle Brothers (French Christian Brother ...

was founded by Archbishop John Ireland

John Benjamin Ireland (January 30, 1914 – March 21, 1992) was a Canadian actor. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in ''All the King's Men'' (1949), making him the first Vancouver-born actor to receive an Oscar nomin ...

in 1900 as a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

secondary school. Its early mission was as a commercial school, but in 1920, parents were asking for a college preparatory school. The school has been in operation for over 100 years in several buildings on Nicollet Island

Nicollet Island is an island in the Mississippi River just north of Saint Anthony Falls in central Minneapolis, Minnesota. According to the United States Census Bureau the island has a land area of and a 2000 census population of 144 persons. T ...

.

Parks

The first park in Minneapolis was land donated to the city in 1857, but it took about 25 years for the community to take a major interest in its parks. The Minneapolis Board of Trade and other civic leaders pressed the Minnesota Legislature for assistance. On February 27, 1883, the Legislature authorized the city to form a park district and to levy taxes. The initial vision was to create a number of boulevards, based on the design concepts of

The first park in Minneapolis was land donated to the city in 1857, but it took about 25 years for the community to take a major interest in its parks. The Minneapolis Board of Trade and other civic leaders pressed the Minnesota Legislature for assistance. On February 27, 1883, the Legislature authorized the city to form a park district and to levy taxes. The initial vision was to create a number of boulevards, based on the design concepts of Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the USA. Olmsted was famous for co- ...

, that would connect parks. Civic leaders also hoped to stimulate economic development and increase land values. Landscape architect Horace Cleveland

Horace William Shaler Cleveland (December 16, 1814 – December 5, 1900) was an American landscape architect. His approach to natural landscape design can be seen in projects such as the Grand Rounds in Minneapolis; Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Conco ...

was hired to create a system of parks named the "Grand Rounds".

Lake Harriet was donated to the city by William S. King

William Smith King (December 16, 1828 – February 24, 1900) was a Republican U.S. Representative for Minnesota from March 4, 1875 to March 3, 1877. He was a journalist and businessman. He is best known for allegations of political corrup ...

in 1885 and the first bandshell on the lake was built in 1888. The current bandshell, built in 1985, is the fifth one in its location.

Minnehaha Falls was purchased as a park in 1889. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely trans ...

named a character in his epic poem, ''The Song of Hiawatha

''The Song of Hiawatha'' is an 1855 epic poem in trochaic tetrameter by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow which features Native American characters. The epic relates the fictional adventures of an Ojibwe warrior named Hiawatha and the tragedy of hi ...

,'' after the falls.

In 1906, Theodore Wirth

Theodore Wirth (1863–1949) was instrumental in designing the Minneapolis system of parks. Swiss-born, he was widely regarded as the dean of the local parks movement in America. The various titles he was given included administrator of pa ...

came to Minneapolis as the parks superintendent. During his tenure, the park system increased from in 57 properties to in 144 properties. The park system, organized around the Minneapolis chain of lakes (including Cedar Lake, Lake of the Isles, Bde Maka Ska, Lake Harriet, Lake Hiawatha, and Lake Nokomis

Lake Nokomis is one of several lakes in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and part of the city's Chain of Lakes. The lake was previously named Lake Amelia in honor of Captain George Gooding's daughter, Amelia, in 1819. Its current name was adopted in 19 ...

) became a model for park planners around the world. He also encouraged active recreation in the parks, as opposed to just setting aside parks for passive admiration.

Arts

The Minneapolis Institute of Art was established in 1883 by twenty-five citizens who were committed to bringing the fine arts into the Minneapolis community. The present building, a neoclassical structure, was designed by the firm ofMcKim, Mead and White

McKim, Mead & White was an American architectural firm that came to define architectural practice, urbanism, and the ideals of the American Renaissance in fin de siècle New York. The firm's founding partners Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909), ...

and opened in 1915. It later received additions in 1974 by Kenzo Tange and in 2006 by Michael Graves.

The Minnesota Orchestra

The Minnesota Orchestra is an American orchestra based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Founded originally as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in 1903, the Minnesota Orchestra plays most of its concerts at Minneapolis's Orchestra Hall.

History

Em ...

dates back to 1903 when it was founded as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. It was renamed the Minnesota Orchestra

The Minnesota Orchestra is an American orchestra based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Founded originally as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in 1903, the Minnesota Orchestra plays most of its concerts at Minneapolis's Orchestra Hall.

History

Em ...

in 1968 and moved into its own building, Orchestra Hall, in downtown Minneapolis in 1974.

The Walker Art Center

The Walker Art Center is a multidisciplinary contemporary art center in the Lowry Hill neighborhood of Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. The Walker is one of the most-visited modern and contemporary art museums in the United States and, to ...

grew out of the Walker Art Gallery, which was established in 1927 by Thomas Barlow Walker, a wealthy lumber baron, as the first public art gallery in the Upper Midwest. Walker had been inviting the public into his home to view his extensive art collection since the 1880's. He built the Walker Art Gallery to perpetuate his public service focus after his death, which occurred soon after the Gallery opened. In the 1940s, under the auspices of the WPA Arts Project, the museum shifted its focus toward modern art, after a gift from Mrs. Gilbert Walker made it possible to acquire works by Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

, Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi-abstract art, abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Mo ...

, Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti (, , ; 10 October 1901 – 11 January 1966) was a Swiss sculptor, painter, draftsman and printmaker. Beginning in 1922, he lived and worked mainly in Paris but regularly visited his hometown Borgonovo to see his family and ...

, and others. The museum continued its focus on modern art with traveling shows in the 1960s and is now one of the "big five" modern art museums in the U.S.

Churches

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church was founded in 1854. It is the oldest church in Minneapolis in continuous use. The church was originally built by the First Universalist Society, and later became a

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church was founded in 1854. It is the oldest church in Minneapolis in continuous use. The church was originally built by the First Universalist Society, and later became a Catholic church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

in 1877 when a Catholic French Canadian congregation acquired it.

The Basilica of Saint Mary was constructed between 1907 and 1915 on land that was formerly a farm, then a

The Basilica of Saint Mary was constructed between 1907 and 1915 on land that was formerly a farm, then a zoological garden

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility in which animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for conservation purposes.

The term ''zoological garden'' refers to zool ...

. Archbishop John Ireland supervised the planning of the church, originally named the Pro-Cathedral of Minneapolis, along with the Cathedral of St. Paul in Saint Paul. He chose architect Emmanuel Masqueray, who was trained at the École des Beaux-Arts

École des Beaux-Arts (; ) refers to a number of influential art schools in France. The term is associated with the Beaux-Arts style in architecture and city planning that thrived in France and other countries during the late nineteenth centur ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. The first Mass was held on May 31, 1914. Church leaders desired to build the finest altar in America, handcrafted of the finest marble they could afford. It was elevated to the rank of basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its nam ...

and became the first basilica in the United States in 1926. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

as one of the area's finest examples of Beaux-Arts architecture

Beaux-Arts architecture ( , ) was the academic architectural style taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, particularly from the 1830s to the end of the 19th century. It drew upon the principles of French neoclassicism, but also incorpo ...

.

A changing city

In the first few decades of the 20th century, Minneapolis began to lose its dominant position in the flour milling industry, after reaching its peak in 1915–1916. The rise of steam power, and later electric power, eroded the advantage that St. Anthony Falls provided in water power. The wheat fields of the Dakotas and Minnesota's Red River Valley began suffering from soil exhaustion due to consecutive wheat crops, leading to an increase in wheat leaf rust and related crop diseases. The farmers of the southern plains developed a variety of hardy red winter wheat suitable for bread flour, and the Kansas City area gained prominence in milling. Also, due to changes in rail shipping rates, millers inBuffalo, New York