History of Mars observation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Mars observation is about the recorded history of observation of the planet

The history of Mars observation is about the recorded history of observation of the planet

The existence of Mars as a wandering object in the night sky was recorded by ancient

The existence of Mars as a wandering object in the night sky was recorded by ancient

The Greeks used the word ''planēton'' to refer to the seven celestial bodies that moved with respect to the background stars and they held a

The Greeks used the word ''planēton'' to refer to the seven celestial bodies that moved with respect to the background stars and they held a

In 1644, the Italian Jesuit Daniello Bartoli reported seeing two darker patches on Mars. During the

In 1644, the Italian Jesuit Daniello Bartoli reported seeing two darker patches on Mars. During the

Surface obscuration caused by yellow clouds had been noted in the 1870s when they were observed by Schiaparelli. Evidence for such clouds was observed during the oppositions of 1892 and 1907. In 1909, Antoniadi noted that the presence of yellow clouds was associated with the obscuration of albedo features. He discovered that Mars appeared more yellow during oppositions when the planet was closest to the Sun and was receiving more energy. He suggested windblown sand or dust as the cause of the clouds.

In 1894, American astronomer William W. Campbell found that the spectrum of Mars was identical to the spectrum of the Moon, throwing doubt on the burgeoning theory that the atmosphere of Mars is similar to that of the Earth. Previous detections of water in the atmosphere of Mars were explained by unfavorable conditions, and Campbell determined that the water signature came entirely from the Earth's atmosphere. Although he agreed that the ice caps did indicate there was water in the atmosphere, he did not believe the caps were sufficiently large to allow the water vapor to be detected. At the time, Campbell's results were considered controversial and were criticized by members of the astronomical community, but they were confirmed by American astronomer

Surface obscuration caused by yellow clouds had been noted in the 1870s when they were observed by Schiaparelli. Evidence for such clouds was observed during the oppositions of 1892 and 1907. In 1909, Antoniadi noted that the presence of yellow clouds was associated with the obscuration of albedo features. He discovered that Mars appeared more yellow during oppositions when the planet was closest to the Sun and was receiving more energy. He suggested windblown sand or dust as the cause of the clouds.

In 1894, American astronomer William W. Campbell found that the spectrum of Mars was identical to the spectrum of the Moon, throwing doubt on the burgeoning theory that the atmosphere of Mars is similar to that of the Earth. Previous detections of water in the atmosphere of Mars were explained by unfavorable conditions, and Campbell determined that the water signature came entirely from the Earth's atmosphere. Although he agreed that the ice caps did indicate there was water in the atmosphere, he did not believe the caps were sufficiently large to allow the water vapor to be detected. At the time, Campbell's results were considered controversial and were criticized by members of the astronomical community, but they were confirmed by American astronomer

The

The

The history of Mars observation is about the recorded history of observation of the planet

The history of Mars observation is about the recorded history of observation of the planet Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

. Some of the early records of Mars' observation date back to the era of the ancient Egyptian astronomers

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

in the 2nd millennium BCE

The 2nd millennium BC spanned the years 2000 BC to 1001 BC.

In the Ancient Near East, it marks the transition from the Middle to the Late Bronze Age.

The Ancient Near Eastern cultures are well within the historical era:

The first half of the mil ...

. Chinese records about the motions of Mars appeared before the founding of the Zhou dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by th ...

(1045 BCE). Detailed observations of the position of Mars were made by Babylonian astronomers

Babylonian astronomy was the study or recording of celestial objects during the early history of Mesopotamia.

Babylonian astronomy seemed to have focused on a select group of stars and constellations known as Ziqpu stars. These constellations m ...

who developed arithmetic techniques to predict the future position of the planet. The ancient Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

and Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

astronomers

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either obse ...

developed a geocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

to explain the planet's motions. Measurements of Mars' angular diameter can be found in ancient Greek and Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

texts. In the 16th century, Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

proposed a heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

for the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

in which the planets follow circular orbits about the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

. This was revised by Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

, yielding an elliptic orbit

In astrodynamics or celestial mechanics, an elliptic orbit or elliptical orbit is a Kepler orbit with an eccentricity of less than 1; this includes the special case of a circular orbit, with eccentricity equal to 0. In a stricter sense, i ...

for Mars that more accurately fitted the observational data.

The first telescopic

A telescope is an instrument designed for the observation of remote objects.

Telescope(s) also may refer to:

Music

* The Telescopes, a British psychedelic band

* ''Telescope'' (album), by Circle, 2007

* ''The Telescope'' (album), by Her Space H ...

observation of Mars was by Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He ...

in 1610. Within a century, astronomers discovered distinct albedo features on the planet, including the dark patch Syrtis Major Planum

Syrtis Major Planum is a "dark spot" (an albedo feature) located in the boundary between the northern lowlands and southern highlands of Mars just west of the impact basin Isidis in the Syrtis Major quadrangle. It was discovered, on the basis o ...

and polar ice cap

A polar ice cap or polar cap is a high-latitude region of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite that is covered in ice.

There are no requirements with respect to size or composition for a body of ice to be termed a polar ice cap, no ...

s. They were able to determine the planet's rotation period

The rotation period of a celestial object (e.g., star, gas giant, planet, moon, asteroid) may refer to its sidereal rotation period, i.e. the time that the object takes to complete a single revolution around its axis of rotation relative to the ...

and axial tilt

In astronomy, axial tilt, also known as obliquity, is the angle between an object's rotational axis and its orbital axis, which is the line perpendicular to its orbital plane; equivalently, it is the angle between its equatorial plane and orb ...

. These observations were primarily made during the time intervals when the planet was located in opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* '' The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Com ...

to the Sun, at which points Mars made its closest approaches to the Earth.

Better telescopes developed early in the 19th century allowed permanent Martian albedo

Albedo (; ) is the measure of the diffuse reflection of solar radiation out of the total solar radiation and measured on a scale from 0, corresponding to a black body that absorbs all incident radiation, to 1, corresponding to a body that refle ...

features to be mapped in detail. The first crude map of Mars was published in 1840, followed by more refined maps from 1877 onward. When astronomers mistakenly thought they had detected the spectroscopic signature of water in the Martian atmosphere, the idea of life on Mars

The possibility of life on Mars is a subject of interest in astrobiology due to the planet's proximity and similarities to Earth. To date, no proof of past or present life has been found on Mars. Cumulative evidence suggests that during the ...

became popularized among the public. Percival Lowell

Percival Lowell (; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars, and furthered theories of a ninth planet within the Solar System. ...

believed he could see a network of artificial canals on Mars. These linear features later proved to be an optical illusion

Within visual perception, an optical illusion (also called a visual illusion) is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual perception, percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide v ...

, and the atmosphere was found to be too thin to support an Earth-like environment.

Yellow clouds on Mars have been observed since the 1870s, which Eugène M. Antoniadi suggested were windblown sand or dust. During the 1920s, the range of Martian surface temperature was measured; it ranged from . The planetary atmosphere was found to be arid with only trace amounts of oxygen and water. In 1947, Gerard Kuiper

Gerard Peter Kuiper (; ; born Gerrit Pieter Kuiper; 7 December 1905 – 23 December 1973) was a Dutch astronomer, planetary scientist, selenographer, author and professor. He is the eponymous namesake of the Kuiper belt.

Kuiper is ...

showed that the thin Martian atmosphere contained extensive carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

; roughly double the quantity found in Earth's atmosphere. The first standard nomenclature for Mars albedo features was adopted in 1960 by the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreac ...

. Since the 1960s, multiple robotic spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle or machine designed to fly in outer space. A type of artificial satellite, spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, ...

have been sent to explore Mars from orbit and the surface. The planet has remained under observation by ground and space-based instruments across a broad range of the electromagnetic spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of frequencies (the spectrum) of electromagnetic radiation and their respective wavelengths and photon energies.

The electromagnetic spectrum covers electromagnetic waves with frequencies ranging fro ...

.The discovery of meteorite

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or moon. When the original object ...

s on Earth that originated on Mars has allowed laboratory examination of the chemical conditions on the planet.

Earliest records

Egyptian astronomers

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

. By the 2nd millennium BCE they were familiar with the apparent retrograde motion

Apparent retrograde motion is the apparent motion of a planet in a direction opposite to that of other bodies within its system, as observed from a particular vantage point. Direct motion or prograde motion is motion in the same direction as ...

of the planet, in which it appears to move in the opposite direction across the sky from its normal progression. Mars was portrayed on the ceiling of the tomb of Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom period, ruling c.1294 or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and the father of Ramesses II.

The ...

, on the Ramesseum

The Ramesseum is the memorial temple (or mortuary temple) of Pharaoh Ramesses II ("Ramesses the Great", also spelled "Ramses" and "Rameses"). It is located in the Theban Necropolis in Upper Egypt, on the west of the River Nile, across from the ...

ceiling, and in the Senenmut

Senenmut ( egy, sn-n-mwt, sometimes spelled Senmut, Senemut, or Senmout) was an 18th Dynasty ancient Egyptian architect and government official. His name translates literally as "mother's brother."

Family

Senenmut was of low commoner birth, ...

star map. The last is the oldest known star map, being dated to 1534 BCE based on the position of the planets.

By the period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

, Babylonian astronomers

Babylonian astronomy was the study or recording of celestial objects during the early history of Mesopotamia.

Babylonian astronomy seemed to have focused on a select group of stars and constellations known as Ziqpu stars. These constellations m ...

were making systematic observations of the positions and behavior of the planets. For Mars, they knew, for example, that the planet made 37 synodic period

The orbital period (also revolution period) is the amount of time a given astronomical object takes to complete one orbit around another object. In astronomy, it usually applies to planets or asteroids orbiting the Sun, moons orbiting planets, ...

s, or 42 circuits of the zodiac, every 79 years. The Babylonians invented arithmetic methods for making minor corrections to the predicted positions of the planets. This technique was primarily derived from timing measurements—such as when Mars rose above the horizon, rather than from the less accurately known position of the planet on the celestial sphere

In astronomy and navigation, the celestial sphere is an abstract sphere that has an arbitrarily large radius and is concentric to Earth. All objects in the sky can be conceived as being projected upon the inner surface of the celestial sphe ...

.

Chinese records of the appearances and motions of Mars appear before the founding of the Zhou dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by th ...

(1045 BCE), and by the Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

(221 BCE) astronomers maintained close records of planetary conjunctions, including those of Mars. Occultations of Mars by Venus were noted in 368, 375, and 405 CE. The period and motion of the planet's orbit was known in detail during the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

(618 CE).

The early astronomy of ancient Greece was influenced by knowledge transmitted from the Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

n culture. Thus, the Babylonians associated Mars with Nergal

Nergal ( Sumerian: d''KIŠ.UNU'' or ; ; Aramaic: ܢܸܪܓܲܠ; la, Nirgal) was a Mesopotamian god worshiped through all periods of Mesopotamian history, from Early Dynastic to Neo-Babylonian times, with a few attestations under indicating hi ...

, their god of war and pestilence, and the Greeks connected the planet with their god of war, Ares

Ares (; grc, Ἄρης, ''Árēs'' ) is the Greek god of war and courage. He is one of the Twelve Olympians, and the son of Zeus and Hera. The Greeks were ambivalent towards him. He embodies the physical valor necessary for success in war ...

. During this period, the motions of the planets were of little interest to the Greeks; Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

's ''Works and Days

''Works and Days'' ( grc, Ἔργα καὶ Ἡμέραι, Érga kaì Hēmérai)The ''Works and Days'' is sometimes called by the Latin translation of the title, ''Opera et Dies''. Common abbreviations are ''WD'' and ''Op''. for ''Opera''. is a ...

'' (''c.'' 650 BCE) makes no mention of the planets.

Orbital models

The Greeks used the word ''planēton'' to refer to the seven celestial bodies that moved with respect to the background stars and they held a

The Greeks used the word ''planēton'' to refer to the seven celestial bodies that moved with respect to the background stars and they held a geocentric

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

view that these bodies moved about the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

. In his work, '' The Republic'' (X.616E–617B), the Greek philosopher Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

provided the oldest known statement defining the order of the planets in Greek astronomical tradition. His list, in order of the nearest to the most distant from the Earth, was as follows: the Moon, Sun, Venus, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...

, Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

, and the fixed stars. In his dialogue '' Timaeus'', Plato proposed that the progression of these objects across the skies depended on their distance, so that the most distant object moved the slowest.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, a student of Plato, observed an occultation

An occultation is an event that occurs when one object is hidden from the observer by another object that passes between them. The term is often used in astronomy, but can also refer to any situation in which an object in the foreground blocks ...

of Mars by the Moon on 4 May 357 BCE. From this he concluded that Mars must lie further from the Earth than the Moon. He noted that other such occultations of stars and planets had been observed by the Egyptians and Babylonians.In China, astronomers recorded an occultation of Mars by the Moon in 69 BCE. See Price (2000:148). Aristotle used this observational evidence to support the Greek sequencing of the planets. His work ''De Caelo

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings ...

'' presented a model of the universe in which the Sun, Moon, and planets circle about the Earth at fixed distances. A more sophisticated version of the geocentric model was developed by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the e ...

when he proposed that Mars moved along a circular track called the epicycle

In the Hipparchian, Ptolemaic, and Copernican systems of astronomy, the epicycle (, meaning "circle moving on another circle") was a geometric model used to explain the variations in speed and direction of the apparent motion of the Moon, S ...

that, in turn, orbited about the Earth along a larger circle called the deferent.

In Roman Egypt

, conventional_long_name = Roman Egypt

, common_name = Egypt

, subdivision = Province

, nation = the Roman Empire

, era = Late antiquity

, capital = Alexandria

, title_leader = Praefectus Augustalis

, image_map = Roman E ...

during the 2nd century CE, Claudius Ptolemaeus

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

(Ptolemy) attempted to address the problem of the orbital motion of Mars. Observations of Mars had shown that the planet appeared to move 40% faster on one side of its orbit than the other, in conflict with the Aristotelian model of uniform motion. Ptolemy modified the model of planetary motion by adding a point offset from the center of the planet's circular orbit about which the planet moves at a uniform rate of rotation. He proposed that the order of the planets, by increasing distance, was: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the fixed stars. Ptolemy's model and his collective work on astronomy was presented in the multi-volume collection ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it can ...

'', which became the authoritative treatise on Western astronomy for the next fourteen centuries.

In the 5th century CE, the Indian astronomical text ''Surya Siddhanta

The ''Surya Siddhanta'' (; ) is a Sanskrit treatise in Indian astronomy dated to 505 CE,Menso Folkerts, Craig G. Fraser, Jeremy John Gray, John L. Berggren, Wilbur R. Knorr (2017)Mathematics Encyclopaedia Britannica, Quote: "(...) its Hindu inven ...

'' estimated the angular size

The angular diameter, angular size, apparent diameter, or apparent size is an angular distance describing how large a sphere or circle appears from a given point of view. In the vision sciences, it is called the visual angle, and in optics, it ...

of Mars as 2 arc-minutes (1/30 of a degree) and its distance to Earth as 10,433,000 km (1,296,600 yojana

A yojana (Sanskrit: योजन; th, โยชน์; my, ယူဇနာ) is a measure of distance that was used in ancient India, Thailand and Myanmar. A yojana is about 12–15 km.

Edicts of Ashoka (3rd century BCE)

Ashoka, in his Major R ...

, where one yojana is equivalent to eight km in the ''Surya Siddhanta''). From this the diameter of Mars is deduced to be 6,070 km (754.4 yojana), which has an error within 11% of the currently accepted value of 6,788 km. However, this estimate was based upon an inaccurate guess of the planet's angular size. The result may have been influenced by the work of Ptolemy, who listed a value of 1.57 arc-minutes. Both estimates are significantly larger than the value later obtained by telescope.

In 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

published a heliocentric model in his work ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, ...

''. This approach placed the Earth in an orbit around the Sun between the circular orbits of Venus and Mars. His model successfully explained why the planets Mars, Jupiter and Saturn were on the opposite side of the sky from the Sun whenever they were in the middle of their retrograde motions. Copernicus was able to sort the planets into their correct heliocentric order based solely on the period of their orbits about the Sun. His theory gradually gained acceptance among European astronomers, particularly after the publication of the ''Prutenic Tables

The ''Prutenic Tables'' ( la, Tabulae prutenicae from ''Prutenia'' meaning "Prussia", german: Prutenische oder Preußische Tafeln), were an ephemeris (astronomical tables) by the astronomer Erasmus Reinhold published in 1551 (reprinted in 1562, 1 ...

'' by the German astronomer Erasmus Reinhold

Erasmus Reinhold (22 October 1511 – 19 February 1553) was a German astronomer and mathematician, considered to be the most influential astronomical pedagogue of his generation. He was born and died in Saalfeld, Saxony.

He was educated, und ...

in 1551, which were computed using the Copernican model.

On October 13, 1590, the German astronomer Michael Maestlin

Michael Maestlin (also Mästlin, Möstlin, or Moestlin) (30 September 1550 – 26 October 1631) was a German astronomer and mathematician, known for being the mentor of Johannes Kepler. He was a student of Philipp Apian and was known as the tea ...

observed an occultation

An occultation is an event that occurs when one object is hidden from the observer by another object that passes between them. The term is often used in astronomy, but can also refer to any situation in which an object in the foreground blocks ...

of Mars by Venus. One of his students, Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

, quickly became an adherent to the Copernican system. After the completion of his education, Kepler became an assistant to the Danish nobleman and astronomer, Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

. With access granted to Tycho's detailed observations of Mars, Kepler was set to work mathematically assembling a replacement to the Prutenic Tables. After repeatedly failing to fit the motion of Mars into a circular orbit as required under Copernicanism, he succeeded in matching Tycho's observations by assuming the orbit was an ellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special type of ellipse in ...

and the Sun was located at one of the foci. His model became the basis for Kepler's laws of planetary motion

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler between 1609 and 1619, describe the orbits of planets around the Sun. The laws modified the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus, replacing its circular orb ...

, which were published in his multi-volume work ''Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae

The ''Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae'' was an astronomy book on the heliocentric system published by Johannes Kepler in the period 1618 to 1621. The first volume (books I–III) was printed in 1618, the second (book IV) in 1620, and the third ...

'' (Epitome of Copernican Astronomy) between 1615 and 1621.

Early telescope observations

At its closest approach, theangular size

The angular diameter, angular size, apparent diameter, or apparent size is an angular distance describing how large a sphere or circle appears from a given point of view. In the vision sciences, it is called the visual angle, and in optics, it ...

of Mars is 25 arcsecond

A minute of arc, arcminute (arcmin), arc minute, or minute arc, denoted by the symbol , is a unit of angular measurement equal to of one degree. Since one degree is of a turn (or complete rotation), one minute of arc is of a turn. The n ...

s (a unit of degree); this is much too small for the naked eye to resolve. Hence, prior to the invention of the telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to obse ...

, nothing was known about the planet besides its position on the sky. The Italian scientist Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He ...

was the first person known to use a telescope to make astronomical observations. His records indicate that he began observing Mars through a telescope in September 1610. This instrument was too primitive to display any surface detail on the planet, so he set the goal of seeing if Mars exhibited phases of partial darkness similar to Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

or the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

. Although uncertain of his success, by December he did note that Mars had shrunk in angular size. Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius

Johannes Hevelius

Some sources refer to Hevelius as Polish:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Some sources refer to Hevelius as German:

*

*

*

*

*of the Royal Society

* (in German also known as ''Hevel''; pl, Jan Heweliusz; – 28 January 1687) was a councillor ...

succeeded in observing a phase of Mars in 1645.

In 1644, the Italian Jesuit Daniello Bartoli reported seeing two darker patches on Mars. During the

In 1644, the Italian Jesuit Daniello Bartoli reported seeing two darker patches on Mars. During the oppositions

''Oppositions'' was an architectural journal produced by the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies from 1973 to 1984. Many of its articles contributed to advancing architectural theory and many of its contributors became distinguished practi ...

of 1651, 1653 and 1655, when the planet made its closest approaches to the Earth, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli, SJ (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion ...

and his student Francesco Maria Grimaldi

Francesco Maria Grimaldi, SJ (2 April 1618 – 28 December 1663) was an Italian Jesuit priest, mathematician and physicist who taught at the Jesuit college in Bologna. He was born in Bologna to Paride Grimaldi and Anna Cattani.

Work

Between ...

noted patches of differing reflectivity

The reflectance of the surface of a material is its effectiveness in reflecting radiant energy. It is the fraction of incident electromagnetic power that is reflected at the boundary. Reflectance is a component of the response of the electronic ...

on Mars. The first person to draw a map of Mars that displayed terrain features was the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists o ...

. On November 28, 1659, he made an illustration of Mars that showed the distinct dark region now known as Syrtis Major Planum

Syrtis Major Planum is a "dark spot" (an albedo feature) located in the boundary between the northern lowlands and southern highlands of Mars just west of the impact basin Isidis in the Syrtis Major quadrangle. It was discovered, on the basis o ...

, and possibly one of the polar ice cap

In glaciology, an ice cap is a mass of ice that covers less than of land area (usually covering a highland area). Larger ice masses covering more than are termed ice sheets.

Description

Ice caps are not constrained by topographical feat ...

s. The same year, he succeeded in measuring the rotation period of the planet, giving it as approximately 24 hours. He made a rough estimate of the diameter of Mars, guessing that it is about 60% of the size of the Earth, which compares well with the modern value of 53%. Perhaps the first definitive mention of Mars's southern polar ice cap was by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini, also known as Jean-Dominique Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian (naturalised French) mathematician, astronomer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the ...

, in 1666. That same year, he used observations of the surface markings on Mars to determine a rotation period of 24h 40m. This differs from the currently-accepted value by less than three minutes. In 1672, Huygens noticed a fuzzy white cap at the north pole.

After Cassini became the first director of the Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (french: Observatoire de Paris ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centers in the world. Its histo ...

in 1671, he tackled the problem of the physical scale of the Solar System. The relative size of the planetary orbits was known from Kepler's third law

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler between 1609 and 1619, describe the orbits of planets around the Sun. The laws modified the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus, replacing its circular orbi ...

, so what was needed was the actual size of one of the planet's orbits. For this purpose, the position of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

was measured against the background stars from different points on the Earth, thereby measuring the diurnal parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby objects ...

of the planet. During this year, the planet was moving past the point along its orbit where it was nearest to the Sun (a perihelic opposition), which made this a particularly close approach to the Earth. Cassini and Jean Picard

Jean Picard (21 July 1620 – 12 July 1682) was a French astronomer and priest born in La Flèche, where he studied at the Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand.

He is principally notable for his accurate measure of the size of the Earth, bas ...

determined the position of Mars from Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, while the French astronomer Jean Richer

Jean Richer (1630–1696) was a French astronomer and assistant (''élève astronome'') at the French Academy of Sciences, under the direction of Giovanni Domenico Cassini.

Between 1671 and 1673 he performed experiments and carried out celestia ...

made measurements from Cayenne

Cayenne (; ; gcr, Kayenn) is the capital city of French Guiana, an overseas region and department of France located in South America. The city stands on a former island at the mouth of the Cayenne River on the Atlantic coast. The city's m ...

, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

. Although these observations were hampered by the quality of the instruments, the parallax computed by Cassini came within 10% of the correct value. The English astronomer John Flamsteed

John Flamsteed (19 August 1646 – 31 December 1719) was an English astronomer and the first Astronomer Royal. His main achievements were the preparation of a 3,000-star catalogue, ''Catalogus Britannicus'', and a star atlas called '' Atlas C ...

made comparable measurement attempts and had similar results.

In 1704, Italian astronomer Jacques Philippe Maraldi "made a systematic study of the southern cap and observed that it underwent" variations as the planet rotated. This indicated that the cap was not centered on the pole. He observed that the size of the cap varied over time. The German-born British astronomer Sir William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel (; german: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-born British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline ...

began making observations of the planet Mars in 1777, particularly of the planet's polar caps. In 1781, he noted that the south cap appeared "extremely large", which he ascribed to that pole being in darkness for the past twelve months. By 1784, the southern cap appeared much smaller, thereby suggesting that the caps vary with the planet's seasons and thus were made of ice. In 1781, he estimated the rotation period of Mars as 24h 39m 21.67s and measured the axial tilt

In astronomy, axial tilt, also known as obliquity, is the angle between an object's rotational axis and its orbital axis, which is the line perpendicular to its orbital plane; equivalently, it is the angle between its equatorial plane and orb ...

of the planet's poles to the orbital plane as 28.5°. He noted that Mars had a "considerable but moderate atmosphere, so that its inhabitants probably enjoy a situation in many respects similar to ours". Between 1796 and 1809, the French astronomer Honoré Flaugergues

Pierre-Gilles-Antoine-Honoré Flaugergues, usually known as Honoré Flaugergues (16 May 1755 in Viviers, Ardèche – 26 November 1835 or 20 November 1830different sources give different years of death) was a French astronomer.

Biography

Flauger ...

noticed obscurations of Mars, suggesting "ochre-colored veils" covered the surface. This may be the earliest report of yellow clouds or storms on Mars.

Geographical period

At the start of the 19th century, improvements in the size and quality of telescope optics proved a significant advance in observation capability. Most notable among these enhancements was the two-componentachromatic lens

An achromatic lens or achromat is a lens that is designed to limit the effects of chromatic and spherical aberration. Achromatic lenses are corrected to bring two wavelengths (typically red and blue) into focus on the same plane.

The most comm ...

of the German optician Joseph von Fraunhofer

Joseph Ritter von Fraunhofer (; ; 6 March 1787 – 7 June 1826) was a German physicist and optical lens manufacturer. He made optical glass, an achromatic telescope, and objective lenses. He also invented the spectroscope and developed diffr ...

that essentially eliminated coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

—an optical effect that can distort the outer edge of the image. By 1812, Fraunhofer had succeeded in creating an achromatic objective lens in diameter. The size of this primary lens is the main factor in determining the light gathering ability and resolution of a refracting telescope

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens as its objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope design was originally used in spyglasses an ...

. During the opposition of Mars in 1830, the German astronomers Johann Heinrich Mädler and Wilhelm Beer used a Fraunhofer refracting telescope

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens as its objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope design was originally used in spyglasses an ...

to launch an extensive study of the planet. They chose a feature located 8° south of the equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can also ...

as their point of reference. (This was later named the Sinus Meridiani

Sinus Meridiani (Latin ''Sinus meridiani'', "Meridian Bay") is an albedo feature on Mars stretching east-west just south of the planet's equator. It was named by the French astronomer Camille Flammarion in the late 1870s.

In 1979-2001, the vicin ...

, and it would become the zero meridian of Mars.) During their observations, they established that most of Mars' surface features were permanent, and more precisely determined the planet's rotation period. In 1840, Mädler combined ten years of observations to draw the first map of Mars. Rather than giving names to the various markings, Beer and Mädler simply designated them with letters; thus Meridian Bay (Sinus Meridiani) was feature "''a''".

Working at the Vatican Observatory

The Vatican Observatory () is an astronomical research and educational institution supported by the Holy See. Originally based in the Roman College of Rome, the Observatory is now headquartered in Castel Gandolfo, Italy and operates a telescope at ...

during the opposition of Mars in 1858, Italian astronomer Angelo Secchi

Angelo Secchi (; 28 June 1818 – 26 February 1878) was an Italian Catholic priest, astronomer from the Italian region of Emilia. He was director of the observatory at the Pontifical Gregorian University (then called the Roman College) for ...

noticed a large blue triangular feature, which he named the "Blue Scorpion". This same seasonal cloud-like formation was seen by English astronomer J. Norman Lockyer in 1862, and it has been viewed by other observers. During the 1862 opposition, Dutch astronomer Frederik Kaiser

Frederik Kaiser (Amsterdam, 10 June 1808 – Leiden, 28 July 1872) was a Dutch astronomer.

He was director of the Leiden Observatory from 1838 until his death.

He is credited with the advancement of Dutch astronomy through his scientific ...

produced drawings of Mars. By comparing his illustrations to those of Huygens and the English natural philosopher Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

, he was able to further refine the rotation period of Mars. His value of 24h 37m 22.6s is accurate to within a tenth of a second.

Father Secchi produced some of the first color illustrations of Mars in 1863. He used the names of famous explorers for the distinct features. In 1869, he observed two dark linear features on the surface that he referred to as ''canali'', which is Italian for 'channels' or 'grooves'. In 1867, English astronomer Richard A. Proctor

Richard Anthony Proctor (23 March 1837 – 12 September 1888) was an English astronomer. He is best remembered for having produced one of the earliest maps of Mars in 1867 from 27 drawings by the English observer William Rutter Dawes. His map w ...

created a more detailed map of Mars based on the 1864 drawings of English astronomer William R. Dawes. Proctor named the various lighter or darker features after astronomers, past and present, who had contributed to the observations of Mars. During the same decade, comparable maps and nomenclature were produced by the French astronomer Camille Flammarion

Nicolas Camille Flammarion FRAS (; 26 February 1842 – 3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science ficti ...

and the English astronomer Nathan Green.

At the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December ...

in 1862–64, German astronomer Johann K. F. Zöllner developed a custom photometer

A photometer is an instrument that measures the strength of electromagnetic radiation in the range from ultraviolet to infrared and including the visible spectrum. Most photometers convert light into an electric current using a photoresistor, ...

to measure the reflectivity of the Moon, planets and bright stars. For Mars, he derived an albedo

Albedo (; ) is the measure of the diffuse reflection of solar radiation out of the total solar radiation and measured on a scale from 0, corresponding to a black body that absorbs all incident radiation, to 1, corresponding to a body that refle ...

of 0.27. Between 1877 and 1893, German astronomers Gustav Müller and Paul Kempf observed Mars using Zöllner's photometer. They found a small phase coefficient—the variation in reflectivity with angle—indicating that the surface of Mars is smooth and without large irregularities. In 1867, French astronomer Pierre Janssen

Pierre Jules César Janssen (22 February 1824 – 23 December 1907), usually known as Jules Janssen, was a French astronomer who, along with English scientist Joseph Norman Lockyer, is credited with discovering the gaseous nature of the solar ...

and British astronomer William Huggins

Sir William Huggins (7 February 1824 – 12 May 1910) was an English astronomer best known for his pioneering work in astronomical spectroscopy together with his wife, Margaret.

Biography

William Huggins was born at Cornhill, Middlesex, in ...

used spectroscope

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

s to examine the atmosphere of Mars. Both compared the optical spectrum

The visible spectrum is the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation in this range of wavelengths is called ''visible light'' or simply light. A typical human eye will respond to wavel ...

of Mars to that of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

. As the spectrum of the latter did not display absorption lines

A spectral line is a dark or bright line in an otherwise uniform and continuous spectrum, resulting from emission or absorption of light in a narrow frequency range, compared with the nearby frequencies. Spectral lines are often used to identi ...

of water, they believed they had detected the presence of water vapor in the atmosphere of Mars. This result was confirmed by German astronomer Herman C. Vogel in 1872 and English astronomer Edward W. Maunder in 1875, but would later come into question. In 1882, an article appeared in Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

discussing snow on the polar regions of Mars and speculation on the probability of ocean currents.

A particularly favorable perihelic opposition occurred in 1877. The English astronomer David Gill used this opportunity to measure the diurnal parallax of Mars from Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island, 7°56′ south of the Equator in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is about from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America. It is governed as part of the British Overseas Territory of ...

, which led to a parallax estimate of . Using this result, he was able to more accurately determine the distance of the Earth from the Sun, based upon the relative size of the orbits of Mars and the Earth. He noted that the edge of the disk of Mars appeared fuzzy because of its atmosphere, which limited the precision he could obtain for the planet's position.

In August 1877, the American astronomer Asaph Hall discovered the two moons of Mars

The two moons of Mars are Phobos (moon), Phobos and Deimos (moon), Deimos. They are irregular in shape. Both were discovered by American astronomer Asaph Hall in August 1877 and are named after the Greek mythology, Greek mythological twin charac ...

using a telescope at the U.S. Naval Observatory. The names of the two satellites, Phobos and Deimos Deimos, a Greek word for ''dread'', may refer to:

* Deimos (deity), one of the sons of Ares and Aphrodite in Greek mythology

* Deimos (moon), the smaller and outermost of Mars' two natural satellites

* Elecnor Deimos, a Spanish aerospace company

* ...

, were chosen by Hall based upon a suggestion by Henry Madan, a science instructor at Eton College

Eton College () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI of England, Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. i ...

in England.

Martian canals

During the 1877 opposition, Italian astronomerGiovanni Schiaparelli

Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli ( , also , ; 14 March 1835 – 4 July 1910) was an Italian astronomer and science historian.

Biography

He studied at the University of Turin, graduating in 1854, and later did research at Berlin Observatory, ...

used a telescope to help produce the first detailed map of Mars. These maps notably contained features he called ''canali'', which were later shown to be an optical illusion

Within visual perception, an optical illusion (also called a visual illusion) is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual perception, percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide v ...

. These ''canali'' were supposedly long straight lines on the surface of Mars to which he gave names of famous rivers on Earth. His term ''canali'' was popularly mistranslated in English as ''canals

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flow un ...

''. In 1886, the English astronomer William F. Denning observed that these linear features were irregular in nature and showed concentrations and interruptions. By 1895, English astronomer Edward Maunder became convinced that the linear features were merely the summation of many smaller details.

In his 1892 work ''La planète Mars et ses conditions d'habitabilité'', Camille Flammarion

Nicolas Camille Flammarion FRAS (; 26 February 1842 – 3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science ficti ...

wrote about how these channels resembled man-made canals, which an intelligent race could use to redistribute water across a dying Martian world. He advocated for the existence of such inhabitants, and suggested they may be more advanced than humans.

Influenced by the observations of Schiaparelli, Percival Lowell

Percival Lowell (; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars, and furthered theories of a ninth planet within the Solar System. ...

founded an observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysical, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed. ...

with telescopes. The observatory was used for the exploration of Mars during the last good opportunity in 1894 and the following less favorable oppositions. He published books on Mars and life on the planet, which had a great influence on the public. The ''canali'' were found by other astronomers, such as Henri Joseph Perrotin and Louis Thollon using a refractor at the Nice Observatory in France, one of the largest telescopes of that time.

Beginning in 1901, American astronomer A. E. Douglass

A. E. (Andrew Ellicott) Douglass (July 5, 1867 in Windsor, Vermont – March 20, 1962 in Tucson, Arizona) was an American astronomer. He discovered a correlation between tree rings and the sunspot cycle, and founded the discipline of dendrochron ...

attempted to photograph the canal features of Mars. These efforts appeared to succeed when American astronomer Carl O. Lampland published photographs of the supposed canals in 1905. Although these results were widely accepted, they became contested by Greek astronomer Eugène M. Antoniadi, English naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British natural history, naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution thro ...

and others as merely imagined features. As bigger telescopes were used, fewer long, straight ''canali'' were observed. During an observation in 1909 by Flammarion with an telescope, irregular patterns were observed, but no ''canali'' were seen.

Starting in 1909 Eugène Antoniadi

Eugène Michel Antoniadi (Greek: Ευγένιος Αντωνιάδης; 1 March 1870 – 10 February 1944) was a Greek-French astronomer.

Biography

Antoniadi was born in Istanbul (Constantinople) but spent most of his adult life in France ...

was able to help disprove the theory of Martian ''canali'' by viewing through the great refractor of Meudon, the Grande Lunette (83 cm lens). A trifecta of observational factors synergize; viewing through the third largest refractor in the World, Mars was at opposition, and exceptional clear weather. The ''canali'' dissolved before Antoniadi's eyes into various "spots and blotches" on the surface of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

.

Refining planetary parameters

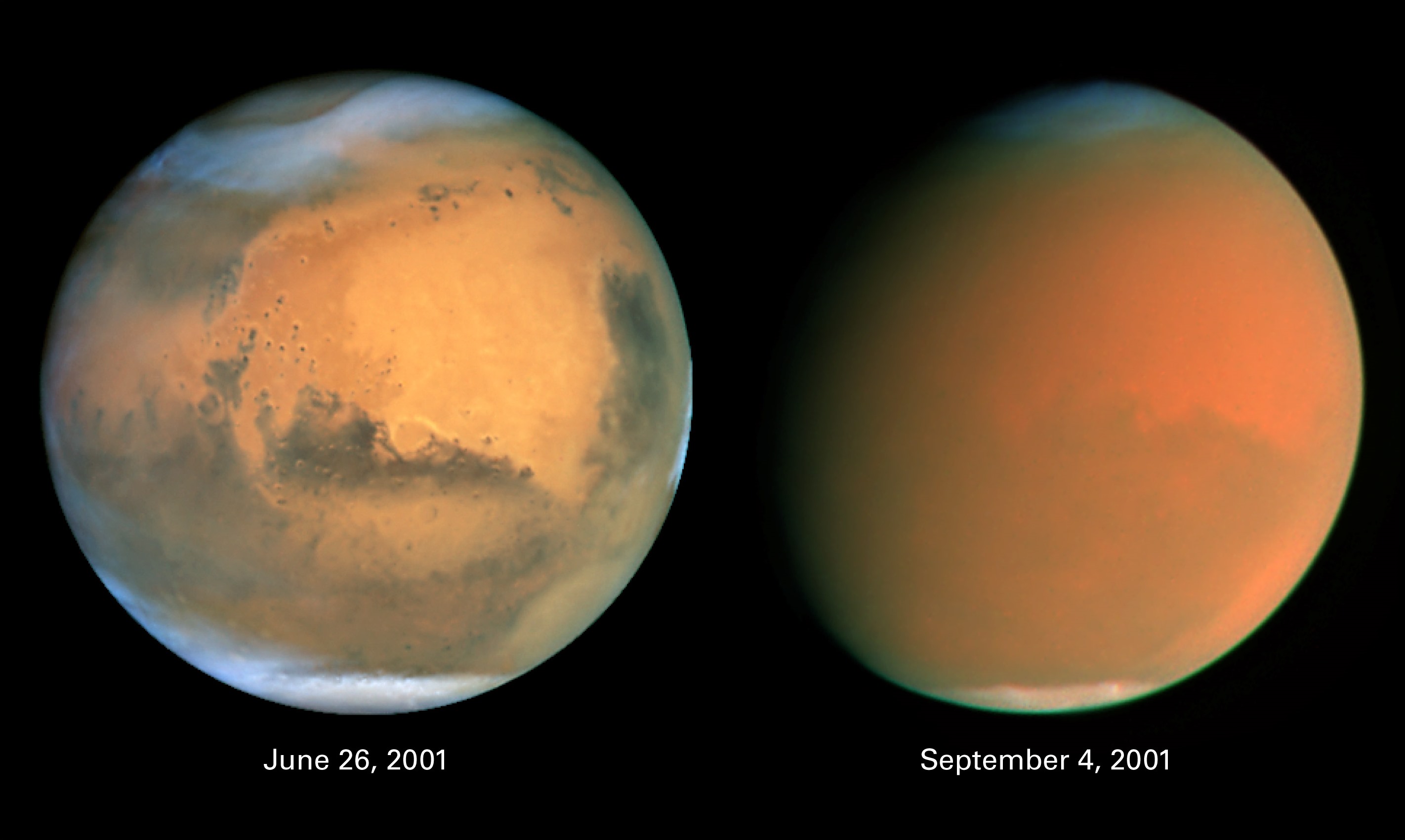

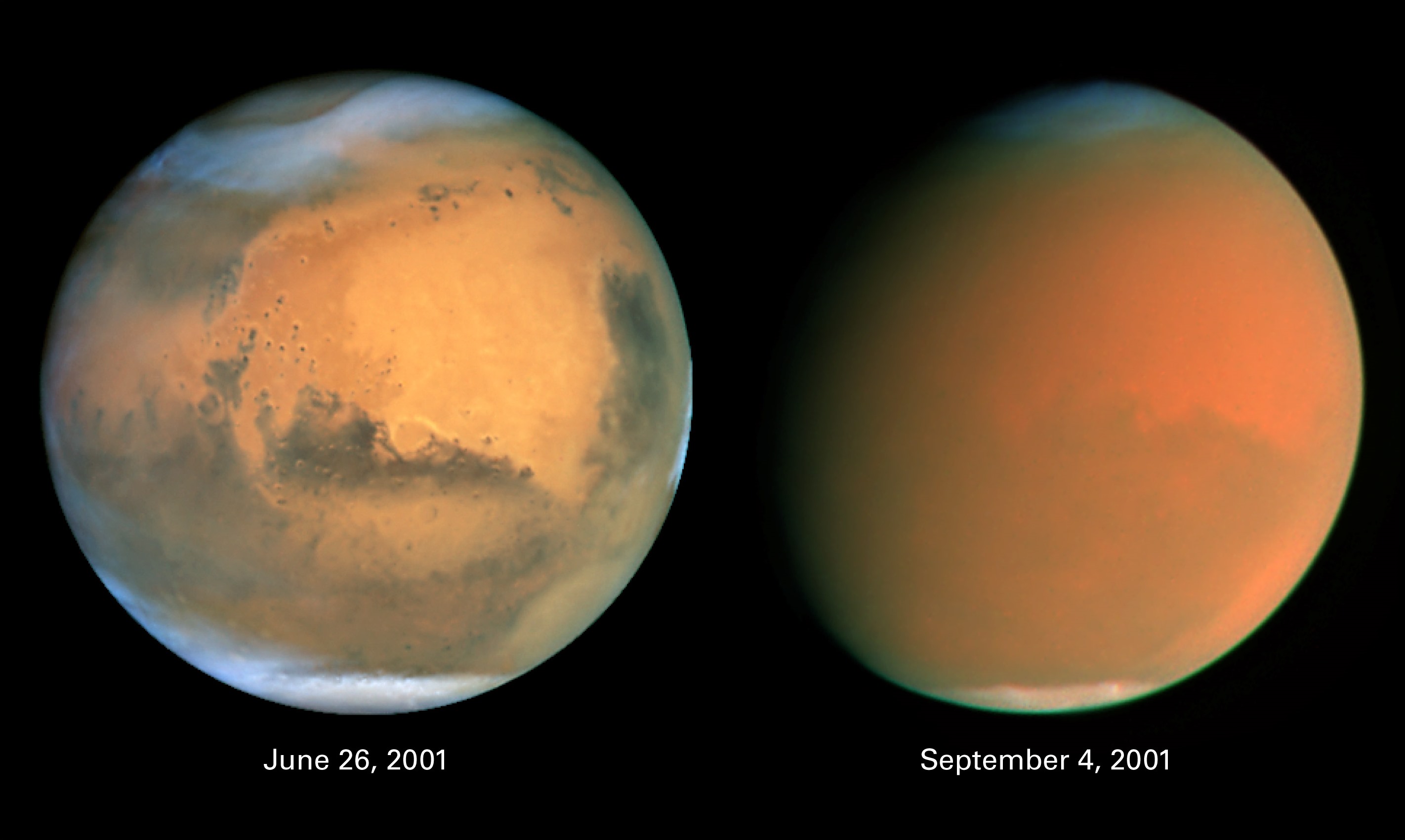

Surface obscuration caused by yellow clouds had been noted in the 1870s when they were observed by Schiaparelli. Evidence for such clouds was observed during the oppositions of 1892 and 1907. In 1909, Antoniadi noted that the presence of yellow clouds was associated with the obscuration of albedo features. He discovered that Mars appeared more yellow during oppositions when the planet was closest to the Sun and was receiving more energy. He suggested windblown sand or dust as the cause of the clouds.

In 1894, American astronomer William W. Campbell found that the spectrum of Mars was identical to the spectrum of the Moon, throwing doubt on the burgeoning theory that the atmosphere of Mars is similar to that of the Earth. Previous detections of water in the atmosphere of Mars were explained by unfavorable conditions, and Campbell determined that the water signature came entirely from the Earth's atmosphere. Although he agreed that the ice caps did indicate there was water in the atmosphere, he did not believe the caps were sufficiently large to allow the water vapor to be detected. At the time, Campbell's results were considered controversial and were criticized by members of the astronomical community, but they were confirmed by American astronomer

Surface obscuration caused by yellow clouds had been noted in the 1870s when they were observed by Schiaparelli. Evidence for such clouds was observed during the oppositions of 1892 and 1907. In 1909, Antoniadi noted that the presence of yellow clouds was associated with the obscuration of albedo features. He discovered that Mars appeared more yellow during oppositions when the planet was closest to the Sun and was receiving more energy. He suggested windblown sand or dust as the cause of the clouds.

In 1894, American astronomer William W. Campbell found that the spectrum of Mars was identical to the spectrum of the Moon, throwing doubt on the burgeoning theory that the atmosphere of Mars is similar to that of the Earth. Previous detections of water in the atmosphere of Mars were explained by unfavorable conditions, and Campbell determined that the water signature came entirely from the Earth's atmosphere. Although he agreed that the ice caps did indicate there was water in the atmosphere, he did not believe the caps were sufficiently large to allow the water vapor to be detected. At the time, Campbell's results were considered controversial and were criticized by members of the astronomical community, but they were confirmed by American astronomer Walter S. Adams

Walter Sydney Adams (December 20, 1876 – May 11, 1956) was an American astronomer.

Life and work

Adams was born in Antioch, Turkey, to Lucien Harper Adams and Nancy Dorrance Francis Adams, missionary parents, and was brought to the U.S. in ...

in 1925.

Baltic German

Baltic Germans (german: Deutsch-Balten or , later ) were ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since their coerced resettlement in 1939, Baltic Germans have markedly declined ...

astronomer Hermann Struve used the observed changes in the orbits of the Martian moons to determine the gravitational influence of the planet's oblate

In Christianity (especially in the Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican and Methodist traditions), an oblate is a person who is specifically dedicated to God or to God's service.

Oblates are individuals, either laypersons or clergy, normally liv ...

shape. In 1895, he used this data to estimate that the equatorial diameter was 1/190 larger than the polar diameter. In 1911, he refined the value to 1/192. This result was confirmed by American meteorologist Edgar W. Woolard in 1944.

Using a vacuum thermocouple

A thermocouple, also known as a "thermoelectrical thermometer", is an electrical device consisting of two dissimilar electrical conductors forming an electrical junction. A thermocouple produces a temperature-dependent voltage as a result of th ...

attached to the Hooker Telescope

The Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO) is an astronomical observatory in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The MWO is located on Mount Wilson, a peak in the San Gabriel Mountains near Pasadena, northeast of Los Angeles.

The observato ...

at Mount Wilson Observatory

The Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO) is an astronomical observatory in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The MWO is located on Mount Wilson, a peak in the San Gabriel Mountains near Pasadena, northeast of Los Angeles.

The observat ...

, in 1924 the American astronomers Seth Barnes Nicholson

Seth Barnes Nicholson (November 12, 1891 – July 2, 1963) was an American astronomer. He worked at the Lick observatory in California, and is known for discovering several moons of Jupiter in the 20th century.

Nicholson was born in Springfield, ...

and Edison Pettit

Edison Pettit (September 22, 1889 – May 6, 1962) was an American astronomer.

He was born in Peru, Nebraska. Pettit received his bachelor's degree from the Nebraska State Normal School in Peru. He taught astronomy at Washburn College in T ...

were able to measure the thermal energy being radiated by the surface of Mars. They determined that the temperature ranged from at the pole up to at the midpoint of the disk (corresponding to the equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can also ...

). Beginning in the same year, radiated energy measurements of Mars were made by American physicist William Coblentz

William Weber Coblentz (November 20, 1873 – September 15, 1962) was an American physicist notable for his contributions to infrared radiometry and spectroscopy.

Early life, education, and employment

William Coblentz was born in North Lima, O ...

and American astronomer Carl Otto Lampland

Carl Otto Lampland (December 29, 1873 – December 14, 1951) was an American astronomer. He was involved with both of the Lowell Observatory solar system projects, observations of the planet Mars and the search for Planet X.

Biography ...

. The results showed that the night time temperature on Mars dropped to , indicating an "enormous diurnal fluctuation" in temperatures. The temperature of Martian clouds was measured as . In 1926, by measuring spectral lines that were redshift

In physics, a redshift is an increase in the wavelength, and corresponding decrease in the frequency and photon energy, of electromagnetic radiation (such as light). The opposite change, a decrease in wavelength and simultaneous increase in fr ...

ed by the orbital motions of Mars and Earth, American astronomer Walter Sydney Adams

Walter Sydney Adams (December 20, 1876 – May 11, 1956) was an American astronomer.

Life and work

Adams was born in Antioch, Turkey, to Lucien Harper Adams and Nancy Dorrance Francis Adams, missionary parents, and was brought to the U.S. i ...

was able to directly measure the amount of oxygen and water vapor in the atmosphere of Mars. He determined that "extreme desert conditions" were prevalent on Mars. In 1934, Adams and American astronomer Theodore Dunham Jr.

Theodore Dunham Jr. (December 17, 1897 – April 3, 1984) was an American astronomer and physicist.

He was born in New York City, the first-born son of Theodore Dunham, a surgeon, and Josephine Balestier. He was educated at the private schools S ...

found that the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere of Mars was less than one percent of the amount over a comparable area on Earth.

In 1927, Dutch graduate student Cyprianus Annius van den Bosch made a determination of the mass of Mars based upon the motions of the Martian moons, with an accuracy of 0.2%. This result was confirmed by the Dutch astronomer Willem de Sitter and published posthumously in 1938. Using observations of the near Earth asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere. ...

Eros

In Greek mythology, Eros (, ; grc, Ἔρως, Érōs, Love, Desire) is the Greek god of love and sex. His Roman counterpart was Cupid ("desire").''Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia'', The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215. In the ear ...

from 1926 to 1945, German-American astronomer Eugene K. Rabe was able to make an independent estimate the mass of Mars, as well as the other planets in the inner Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

, from the planet's gravitational perturbations of the asteroid. His estimated margin of error was 0.05%, but subsequent checks suggested his result was poorly determined compared to other methods.

During the 1920s, French astronomer Bernard Lyot

Bernard Ferdinand Lyot (27 February 1897 in Paris – 2 April 1952 in Cairo) was a French astronomer.

Biography

An avid reader of the works of Camille Flammarion, he became a member of the Société Astronomique de France in 1915 and made h ...

used a polarimeter

A polarimeter is a scientific instrument used to measure the angle of rotation caused by passing polarized light through an optically active substance.polarized light

Polarization ( also polarisation) is a property applying to transverse waves that specifies the geometrical orientation of the oscillations. In a transverse wave, the direction of the oscillation is perpendicular to the direction of motion of t ...

emitted from the Martian surface is very similar to that radiated from the Moon, although he speculated that his observations could be explained by frost and possibly vegetation. Based on the amount of sunlight scattered by the Martian atmosphere, he set an upper limit of 1/15 the thickness of the Earth's atmosphere. This restricted the surface pressure to no greater than . Using infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of Light, visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from ...

spectrometry, in 1947 the Dutch-American astronomer Gerard Kuiper

Gerard Peter Kuiper (; ; born Gerrit Pieter Kuiper; 7 December 1905 – 23 December 1973) was a Dutch astronomer, planetary scientist, selenographer, author and professor. He is the eponymous namesake of the Kuiper belt.

Kuiper is ...

detected carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

in the Martian atmosphere. He was able to estimate that the amount of carbon dioxide over a given area of the surface is double that on the Earth. However, because he overestimated the surface pressure on Mars, Kuiper concluded erroneously that the ice caps could not be composed of frozen carbon dioxide. In 1948, American meteorologist Seymour L. Hess determined that the formation of the thin Martian clouds would only require of water precipitation and a vapor pressure

Vapor pressure (or vapour pressure in English-speaking countries other than the US; see spelling differences) or equilibrium vapor pressure is defined as the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed pha ...

of .

The first standard nomenclature for Martian albedo features was introduced by the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreac ...

(IAU) when in 1960 they adopted 128 names from the 1929 map of Antoniadi named ''La Planète Mars''. The Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN) was established by the IAU in 1973 to standardize the naming scheme for Mars and other bodies.

Remote sensing

The

The International Planetary Patrol Program The NASA International Planetary Patrol Program consists of a network of astronomical observatories to collect uninterrupted images and observations of the large-scale atmospheric and surface features of the planets. This group was established in 19 ...

was formed in 1969 as a consortium to continually monitor planetary changes. This worldwide group focused on observing dust storms on Mars. Their images allow Martian seasonal patterns to be studied globally, and they showed that most Martian dust storms occur when the planet is closest to the Sun.

Since the 1960s, robotic spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle or machine designed to fly in outer space. A type of artificial satellite, spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, ...

have been sent to explore Mars from orbit and the surface

A surface, as the term is most generally used, is the outermost or uppermost layer of a physical object or space. It is the portion or region of the object that can first be perceived by an observer using the senses of sight and touch, and is ...

in extensive detail. In addition, remote sensing of Mars from Earth by ground-based and orbiting telescopes has continued across much of the electromagnetic spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of frequencies (the spectrum) of electromagnetic radiation and their respective wavelengths and photon energies.

The electromagnetic spectrum covers electromagnetic waves with frequencies ranging fro ...

. These include infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of Light, visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from ...

observations to determine the composition of the surface, ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

and submillimeter observation of the atmospheric composition, and radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a tr ...

measurements of wind velocities.

The Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble Space Telescope (often referred to as HST or Hubble) is a space telescope that was launched into low Earth orbit in 1990 and remains in operation. It was not the first space telescope, but it is one of the largest and most vers ...

(HST) has been used to perform systematic studies of Mars and has taken the highest resolution images of Mars ever captured from Earth. This telescope can produce useful images of the planet when it is at an angular distance

Angular distance \theta (also known as angular separation, apparent distance, or apparent separation) is the angle between the two sightlines, or between two point objects as viewed from an observer.

Angular distance appears in mathematics (in par ...

of at least 50° from the Sun. The HST can take images of a hemisphere

Hemisphere refers to:

* A half of a sphere

As half of the Earth

* A hemisphere of Earth

** Northern Hemisphere

** Southern Hemisphere

** Eastern Hemisphere

** Western Hemisphere

** Land and water hemispheres

* A half of the (geocentric) celes ...

, which yields views of entire weather systems. Earth-based telescopes equipped with charge-coupled device

A charge-coupled device (CCD) is an integrated circuit containing an array of linked, or coupled, capacitors. Under the control of an external circuit, each capacitor can transfer its electric charge to a neighboring capacitor. CCD sensors are a ...

s can produce useful images of Mars, allowing for regular monitoring of the planet's weather during oppositions.

X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

emission from Mars was first observed by astronomers in 2001 using the Chandra X-ray Observatory

The Chandra X-ray Observatory (CXO), previously known as the Advanced X-ray Astrophysics Facility (AXAF), is a Flagship-class space telescope launched aboard the during STS-93 by NASA on July 23, 1999. Chandra is sensitive to X-ray sources ...