History of Maine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the area comprising the U.S. state of

There are many stories of

There are many stories of  The New Somersetshire colony was small, and in 1639 Gorges received a second patent, from

The New Somersetshire colony was small, and in 1639 Gorges received a second patent, from  In 1686 James, now king, established the

In 1686 James, now king, established the

/ref> The Maine Constitution was unanimously approved by the 210 delegates to the Maine Constitutional Convention in October 1819. On February 25, 1820, the General Court passed a follow-up measure officially accepting the fact of Maine's imminent statehood. At the time of Maine's request for statehood, there were an equal number of

Maine was the first state in the northeast to support the new anti-slavery

Maine was the first state in the northeast to support the new anti-slavery

/ref>

Mother Jones, March/April 2004 Mainly concentrated in Lewiston, Somalis have opened up community centers to cater to their community. In 2001, the non-profit organization United Somali Women of Maine (USWM) was founded in Lewiston, seeking to promote the empowerment of Somali women and girls across the state. In August 2010, the ''

/ref> Most of the early arrivals in the United States settled in Clarkston,

Mather Cotten. Magnalia Christi Americana, or, The ecclesiastical history of New-England: from its first planting in the year 1620, unto the year of Our Lord, 1698, in seven books (1702)

A summary, historical and political, of the first planting, progressive ... By William Douglass. 1755 Hubbard's Narrative History of the Indian Wars. 1677

*

Thomas Hutchingson. The history of the province of Massachusetts-Bay. Vol. 1. 1828 Thomas Hitchingson. Story of the province of Massachusetts bay, from 1749 to 1774, Vol. 2 George Minot. Continuation of the history of Massachusetts Bay, Vol. 1, 1798George Minot. Continuation of the history of Massachusetts Bay, Vol. 2

Samuel Niles, "History of the Indian and French wars," (1760) reprinted in Mass. Hist. Soc. Coll., 3d ser., VI (1837), 248–50

*

Samuel Penhallow. History of the New England Wars with the Eastern Indians. 1726

Journal of John PikeSamuel Sewell vol. 1 (1674-1729) Rufus Sewall. Ancient dominions of Maine. 1859 Journals of the Rev. Thomas Smith, and the Rev. Samuel Deane, pastors of the First church in Portland: with notes and biographical notices: and a Summary history of Portland (1849)

James Sullivan. History of Maine. 1796

* Stevens, John, Cabot Abbott, Edward Henry Elwell

''The History of Maine''

(1892). comprehensive older history

Herbert Sylvester. Indian Wars of New England Vol. 1Herbert Sylvester. Indian Wars of New England Vol. 3 William D. Williamson, ''The History of the State of Maine, Vol. 1'' (1832)William Williamson. History of Maine 'Vol. 2

vol.1

vol2, vol 3, (1919) * Leamon, James S. ''Revolution Downeast: The War for American Independence in Maine'' (University of Massachusetts Press, 1993

online edition

* Lockard, Duane. ''New England State Politics'' (1959) pp 79–118; covers 1932–1958 * MacDonald, William

''The Government of Maine: Its History and Administration''

(1902). * Palmer, Kenneth T., G. Thomas Taylor, Marcus A. Librizzi; ''Maine Politics & Government'' (University of Nebraska Press, 1992

online edition

* Rolde, Neil ''Maine: A Narrative History'

(1990) * Peirce, Neal R. ''The New England States: People, Politics, and Power in the Six New England States'' (1976) pp 362–420; updated in Neal R. Peirce and Jerry Hagstrom, ''The Book of America: Inside the Fifty States Today'' (1983) pp 208–13 * Stewart, Alice R. "The Franco-Americans of Maine: A Historiographical Essay," ''Maine Historical Society Quarterly'' 1987 26(3): 160-179 * WPA. ''Maine, a Guide down East'' (1937

online edition

famous guidebook

History of SacoHistory of WellsHistory of York, Maine

* Bruce J. Bourque. ''Twelve Thousand Years: American Indians in Maine'' (University of Nebraska Press, 2001

online editionHistory of Thomaston, Rockland, and South Thomaston, Maine: From ..., Volume 1 By Cyrus Eaton

History of Brunswick, Topsham, and Harpswell, Maine

Including Ancient Pejepscot. By

History of Castine, Penobscot, and Brooksville, Maine

including the ancient settlement of Pentagoet. By

William Willis. History of Portland. 1865

Sketches of the History of the Town of Camden, Maine.

By John Lymburner Locke. Published 1859.

History of Boothbay, Southport and Boothbay Harbor, Maine

1623–1905. By Francis Byron Greene. Published 1906.

History of Farmington, Maine, from Its First Settlement.

By Thomas Parker. Published 1875.

History of Bath and Environs, Sagadahoc County, Maine, 1607-1894.

By Parker McCobb Reed.

The Makers of Maine: Essays and Tales of Early Maine History.

By Herbert Edgar Holmes. Published 1912.

Sketches of the Ecclesiastical History of the State of Maine.

By Jonathan Greenleaf. Published 1821.

A History of the Baptists in Maine.

By Joshua Millet. Published 1845.

History of the First Maine Cavalry, 1861-1865.

By Edward Parsons Tobie. Published 1887.

History of Piscataquis County, Maine: From Its Earliest Settlement to 1880.

By Amasa Loring. Published 1880.

A History of Swan's Island, Maine.

By Herman Wesley Small. Published 1898.

Genealogical and Family History of the State of Maine.

By Henry Sweetser Burrage, Albert Roscoe Stubbs. Published 1909, Vol. 1.

The History of Waterford: Oxford County, Maine.

By Henry Pelt Warren, William Warren. Published 1879.

The History of Sanford, Maine, 1661-1900.

By Edwin Emery, William Morrell Emery. Published 1901.

History of Rumford, Oxford County, 156651645Maine: From Its First Settlement in 1779.

By William Berry Lapham. Published 1890.

History of the City of Belfast in the State of Maine.

By Joseph Williamson. Published 1877.

History of Belfast in the 20th Century

by Jay Davis and Tim Hughes with Megan Pinette. Published 2002 by the Belfast History Project

A History of the Town of Industry: Franklin County, Maine.

By William Collins Hatch. Published 1893.

History of the Maine State College and the University of Maine.

By Merritt Caldwell Fernald. Published 1916. *

online edition

* Richard P. Horwitz; ''Anthropology toward History: Culture and Work in a 19th Century Maine Town,'' (Wesleyan University Press, 1978

online edition

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Vol.1, 1865

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Vol.2, 1847

Vol. 3

Vol. 4

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Vol.5, 1857 Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Vol. 6

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Vol.7, 1859

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Vol.8, 1881

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Vol.9, 1887Collections of the Maine Historical Society - Index Vol.1-10

Second Series

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Second Series. Vol.1, 1890Second Series, Vol. 2

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Second Series. Vol.3, 1892

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Second Series. Vol.4, 1893Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Second Series, Volume 5 (1894)

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Second Series. Vol.6, 1895Vol.7Vol. 8

Vol. 9

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Second Series. Vol.10, 1899

Third Series

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Third Series. Vol.1, 1901

Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Third Series. Vol.2, 1906

Vol. 6Vol 7 Vol. 9 (1689-1723) Documentary history of the state of Maine, vol. 10 (1662-1729)Vol. 11 (1729-1749)Vo. 12 (1749-1755)

Vol. 13 (1755-1768)Vol. 14

(1776-1777)

Vol. 15

(1777-1778)

vol. 16

(1778-1779)

Vol. 17

(1777-1779)

Vol.18

(1778-1780)

Vol.19

(1780-1782)

Vol. 20

(1781-1785)

Vol. 21

(1785-1788)

Vol. 22 (1788-1791) Vol. 23 (Native affairs)

Vol. 24 (Native affairs)

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Maine

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

spans thousands of years, measured from the earliest human settlement, or approximately two hundred, measured from the advent of U.S. statehood in 1820. The present article will concentrate on the period of European contact and after.

The origin of the name ''Maine'' is unclear. One theory is it was named after the French province of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

. Another is that it derives from a practical nautical term, "the main" or "Main Land", "Meyne" or "Mainland", which served to distinguish the bulk of the state from its numerous islands.

Etymology

There is no definitive explanation for the origin of the name "Maine", but the most likely is that early explorers named it after the former province of Maine inFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. Whatever the origin, the name was fixed for English settlers in 1665 when the English King's Commissioners ordered that the "Province of Maine" be entered from then on in official records. The state legislature in 2001 adopted a resolution establishing Franco-American Day, which stated that the state was named after the former French province of Maine.

Other theories mention earlier places with similar names or claim it is a nautical

Seamanship is the art, knowledge and competence of operating a ship, boat or other craft on water. The'' Oxford Dictionary'' states that seamanship is "The skill, techniques, or practice of handling a ship or boat at sea."

It involves topics ...

reference to the mainland. Captain John Smith, in his "Description of New England" (1614) laments the lack of exploration: "Thus you may see, of this 2000. miles more then halfe is yet vnknowne to any purpose: no not so much as the borders of the Sea are yet certainly discouered. As for the goodnes and true substances of the Land, wee are for most part yet altogether ignorant of them, vnlesse it bee those parts about the Bay of Chisapeack and Sagadahock: but onely here and there wee touched or haue seene a little the edges of those large dominions, which doe stretch themselues into the Maine, God doth know how many thousand miles;"

Note that his description of the mainland of North America is "the Maine". The word "main" was a frequent shorthand for the word "mainland" (as in "The Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of America, the Spanish Main was the collective term for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The term was used to ...

").

The first known record of the name appears in an August 10, 1622, land charter to Sir Ferdinando Gorges and Captain John Mason, English Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

veterans, who were granted a large tract in present-day Maine that Mason and Gorges "intend to name the Province of Maine". Mason had served with the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

in the Orkney Islands

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) no ...

, where the chief island is called Mainland, a possible name derivation for these English sailors. In 1623, the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

naval captain Christopher Levett

Capt. Christopher Levett (15 April 1586 – 1630) was an English writer, explorer and naval captain, born at York, England. He explored the coast of New England and secured a grant from the King to settle present-day Portland, Maine, the fi ...

, exploring the New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

coast, wrote: "The first place I set my foote upon in New England was the Isle of Shoals, being Ilands in the sea, above two Leagues from the Mayne." Initially, several tracts along the coast of New England were referred to as ''Main'' or ''Maine'' (cf.

The abbreviation ''cf.'' (short for the la, confer/conferatur, both meaning "compare") is used in writing to refer the reader to other material to make a comparison with the topic being discussed. Style guides recommend that ''cf.'' be used onl ...

the Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of America, the Spanish Main was the collective term for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The term was used to ...

). A reconfirmed and enhanced April 3, 1639, charter, from England's King CharlesI, gave Sir Ferdinando Gorges increased powers over his new province and stated that it "shall forever hereafter, be called and named the PROVINCE OR COUNTIE OF MAINE, and not by any other name or names whatsoever..." Maine is the only U.S. state whose name has only one syllable.

Attempts to uncover the history of the name of Maine began with James Sullivan's 1795 "History of the District of Maine." He made the unsubstantiated claim that the Province of Maine was a compliment to the queen of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She was ...

, who once "owned" the Province of Maine in France. Maine historians quoted this until the 1845 biography of that queen by Agnes Strickland established that she had no connection to the province; further, King Charles I married Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She was ...

in 1625, three years after the name Maine first appeared on the charter. A new theory put forward by Carol B. Smith Fisher in 2002 postulated that Sir Ferdinando Gorges chose the name in 1622 to honor the village where his ancestors first lived in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, rather than the province in France. "MAINE" appears in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

of 1086 in reference to the county of Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

, which is today Broadmayne

Broadmayne is a village in the English county of Dorset. It lies two miles south-east of the county town Dorchester. The A352 main road between Dorchester (from Sherborne) and Wareham passes through the village. In the 2001 Census the populat ...

, just southeast of Dorchester.

The view generally held among British place name scholars is that Mayne in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

is Brythonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

, corresponding to modern Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

"maen", plural "main" or "meini". Some early spellings are: MAINE 1086, MEINE 1200, MEINES 1204, MAYNE 1236. Today the village is known as Broadmayne

Broadmayne is a village in the English county of Dorset. It lies two miles south-east of the county town Dorchester. The A352 main road between Dorchester (from Sherborne) and Wareham passes through the village. In the 2001 Census the populat ...

, which is primitive Welsh or Brythonic, "main" meaning rock or stone, considered a reference to the many large sarsen stones still present around Little Mayne farm, half a mile northeast of Broadmayne village.

Pre-European history

The earliest culture known to have inhabited Maine, from roughly 3000 BC to 1000 BC, were the Red Paint People, a maritime group known for elaborate burials usingred ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced ...

. They were followed by the Susquehanna culture, the first to use pottery.

By the time of European discovery, the inhabitants of Maine were the Algonquian-speaking Wabanaki peoples, including the Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

, Passamaquoddy

The Passamaquoddy ( Maliseet-Passamaquoddy: ''Peskotomuhkati'') are a Native American/First Nations people who live in northeastern North America. Their traditional homeland, Peskotomuhkatik'','' straddles the Canadian province of New Brunswick ...

, and Penobscot

The Penobscot ( Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewi'') are an Indigenous people in North America from the Northeastern Woodlands region. They are organized as a federally recognized tribe in Maine and as a First Nations band government in the Atlantic ...

s.

Colonial period

There are many stories of

There are many stories of Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the ...

exploring as far south as Maine, but there is currently no documented evidence for that. In 1497 John Cabot

John Cabot ( it, Giovanni Caboto ; 1450 – 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest-known European exploration of coastal Nor ...

made the first of two documented voyages to explore the New World on behalf of Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beauf ...

and it's very likely on one of the voyages reached as far south as the coast of Maine. Cabot's expeditions were based out of the fishing port of Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

, England, and Bristol merchant William Weston followed up on Cabot's efforts in 1499. Cabot's crews reported (as written in a letter to the Duke of Milan in 1497): "''The Sea there is swarming with fish which can be taken not only with the net but in baskets with a stone, so that it sinks in the water.''" In fact Bristol fishermen had already been sailing to Iceland for cod fishing, and after Weston's return there is anecdotal evidence that Europeans from England to Portugal regularly fished the waters of the northeast waters, including the Gulf of Maine, immediately afterwards.

Following disputed rights over the northeast coasts between Spain and England the next documented Europeans to explore the coast of Maine were by Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , , often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1485–1528) was an Italian ( Florentine) explorer of North America, in the service of King Francis I of France.

He is renowned as the first European to explore the Atlanti ...

under the French flag in 1574, and then the Portuguese explorer Estêvão Gomes, in service of the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, in 1525. They mapped the coastline (including the Penobscot River

The Penobscot River (Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 22, 2011 river in the U.S. state of Maine. Including the river's ...

) but did not settle, though Verrazzano's efforts added a French claim to the area. The first European settlement in the area was made on St. Croix Island in 1604 by a French party that included Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fr ...

and Mathieu da Costa

, birth_date = March 1 1589

, other_names = Mathieu da Costa (sometimes d'Acosta)

, death_date = after 1619

, death_place = Quebec City, Quebec

, known_for = First recorded black person in Canada, Exploration of New France, Bridge betwe ...

. The French named the area Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

. French and English settlers would contest central Maine until the 1750s (when the French were defeated in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

). The French developed and maintained strong relations with the local Indian tribes through Catholic missionaries.

English colonists sponsored by the Plymouth Company

The Plymouth Company, officially known as the Virginia Company of Plymouth, was a division of the Virginia Company with responsibility for colonizing the east coast of America between latitudes 38° and 45° N.

History

The merchants (wit ...

founded a settlement in Maine in 1607 (the Popham Colony

The Popham Colony—also known as the Sagadahoc Colony—was a short-lived English colonial settlement in North America. It was established in 1607 by the proprietary Plymouth Company and was located in the present-day town of Phippsburg, Ma ...

at Phippsburg), but it was abandoned the following year. A French trading post was established at present-day Castine in 1613 by Claude de Saint-Étienne de la Tour, and may represent the first permanent European settlement in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. The Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the passengers on the ...

, established on the shores of Cape Cod Bay

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment which drapes the wearer's back, arms, and chest, and connects at the neck.

History

Capes were common in medieval Europe, especially when combined with a hood in the chaperon. T ...

in 1620, set up a competing trading post at Penobscot Bay in the 1620s.

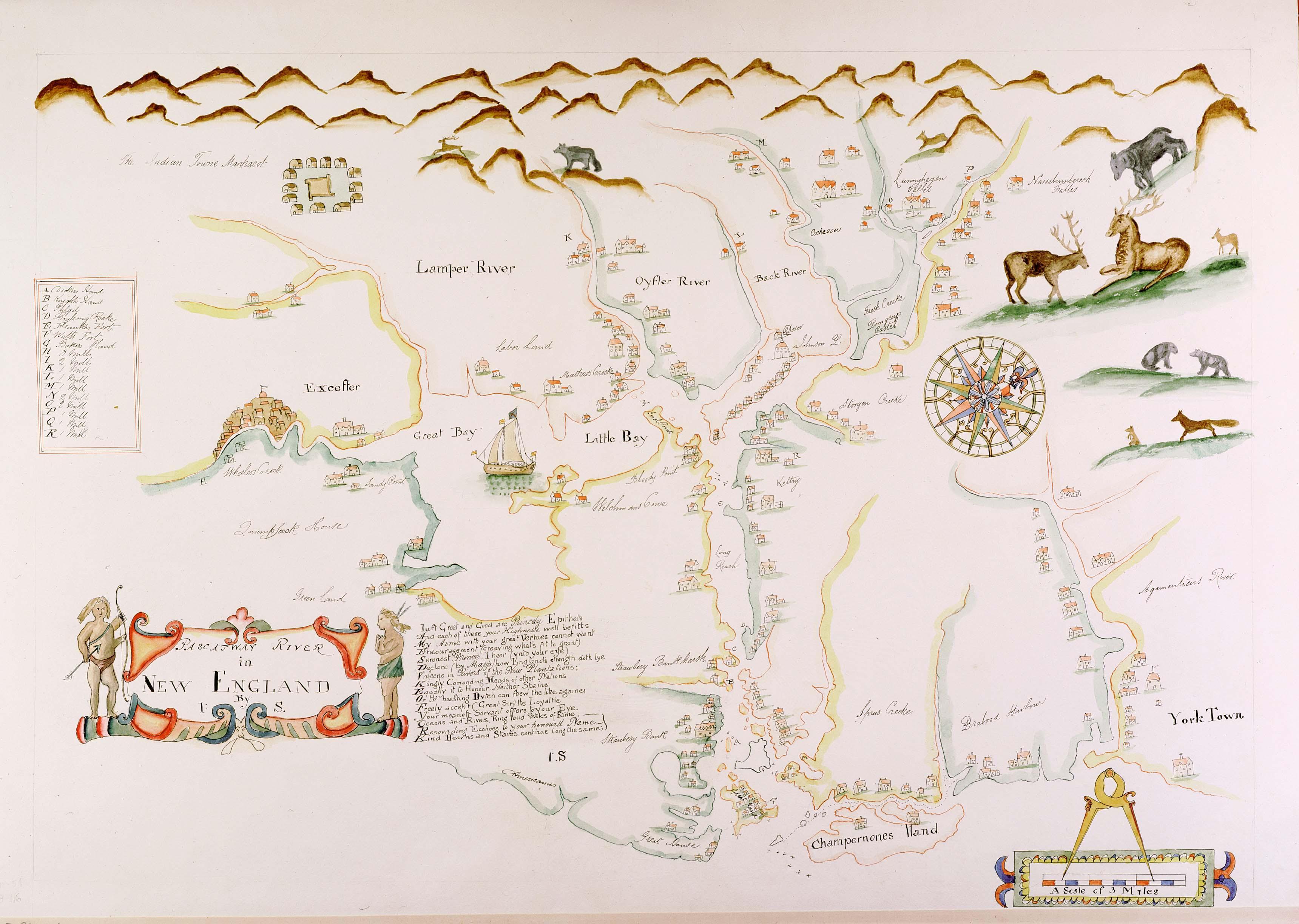

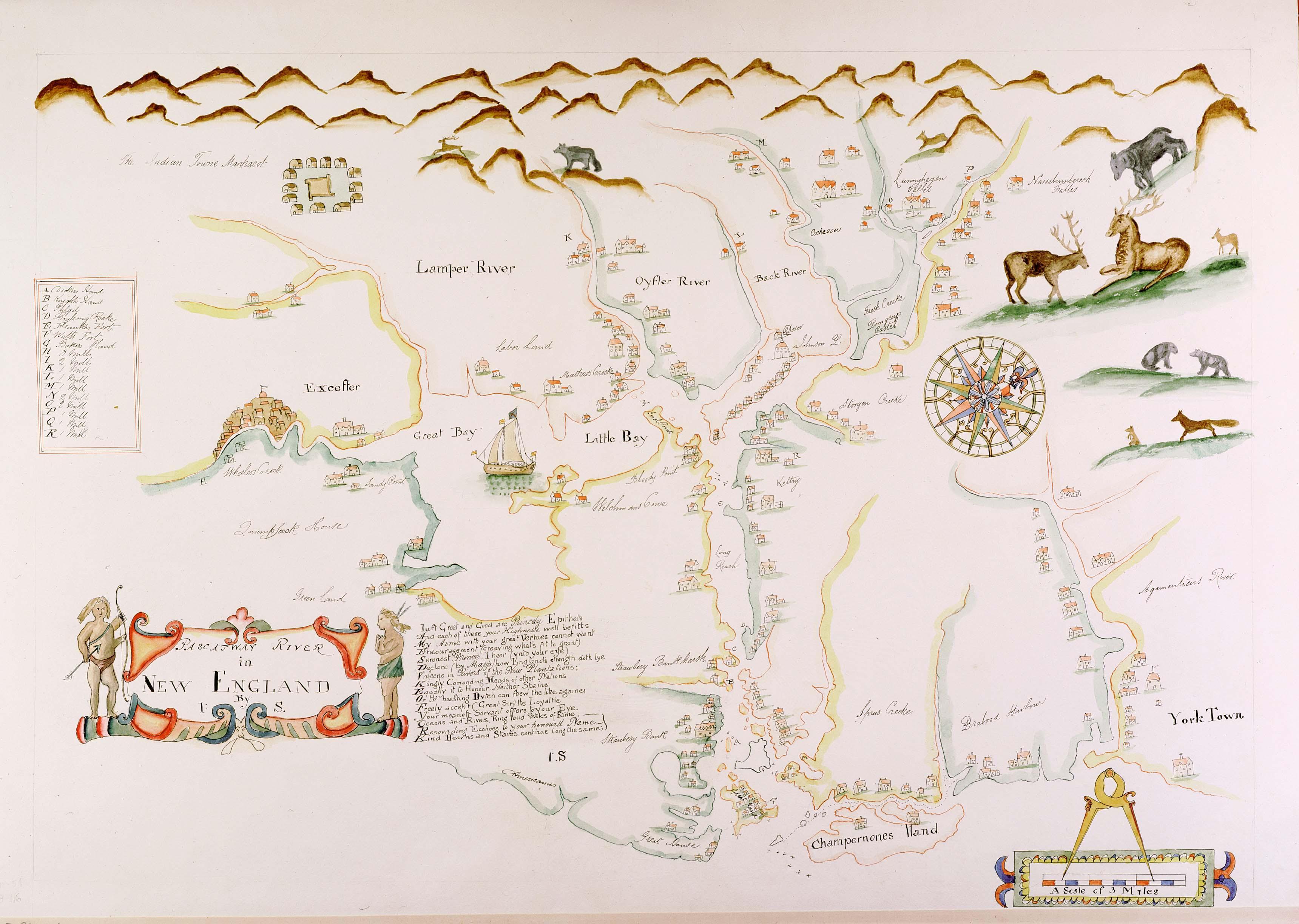

The territory between the Merrimack and Kennebec rivers was first called the Province of Maine in a 1622 land patent granted to Sir Ferdinando Gorges

Sir Ferdinando Gorges ( – 24 May 1647) was a naval and military commander and governor of the important port of Plymouth in England. He was involved in Essex's Rebellion against the Queen, but escaped punishment by testifying against the mai ...

and John Mason. The two split the territory along the Piscataqua River in a 1629 pact that resulted in the Province of New Hampshire

The Province of New Hampshire was a colony of England and later a British province in North America. The name was first given in 1629 to the territory between the Merrimack and Piscataqua rivers on the eastern coast of North America, and was nam ...

being formed by Mason in the south and New Somersetshire

The Province of Maine refers to any of the various English colonies established in the 17th century along the northeast coast of North America, within portions of the present-day U.S. states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, and the Canadian ...

being created by Gorges to the north, in what is now southwestern Maine. The present Somerset County in Maine preserves this early nomenclature.

One of the first English attempts to settle the Maine coast was by Christopher Levett

Capt. Christopher Levett (15 April 1586 – 1630) was an English writer, explorer and naval captain, born at York, England. He explored the coast of New England and secured a grant from the King to settle present-day Portland, Maine, the fi ...

, an agent for Gorges and a member of the Plymouth Council for New England

The Council for New England was a 17th-century English joint stock company that was granted a royal charter to found colonial settlements along the coast of North America. The Council was established in November of 1620, and was disbanded (alt ...

. After securing a royal grant for of land on the site of present-day Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropo ...

, Levett built a stone house and left a group of settlers behind when he returned to England in 1623 to drum up support for his settlement, which he called "York" after the city in England of his birth. Originally called Machigonne by the local Abenaki, later settlers named it Falmouth and it is known today as Portland. Levett's settlement, like the Popham Colony also failed, and the settlers Levett left behind were never heard from again. Levett did sail back across the Atlantic to meet with Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

Governor John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

at Salem in 1630, but died on the return voyage without ever returning to his settlement.

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, covering the same territory as Gorges' 1629 settlement with Mason. Gorges' second effort resulted in the establishment of more settlements along the coast of southern Maine, and along the Piscataqua River, with a formal government under his distant relation, Thomas Gorges. A dispute about the bounds of a 1630 land grant led in 1643 to the short-lived formation of Lygonia

Lygonia was a proprietary province in pre-colonial Maine, created through a grant from the Plymouth Council for New England in 1630 to lands then under control of Sir Ferdinando Gorges. The province was named for his mother, Cicely (Lygon) Gorges. ...

on territory that encompassed a large area of the Gorges grant (modern Portland, Scarborough and Saco).

The 1629 Charter of Massachusetts Bay set the northern sea-to-sea boundary three miles north of the northernmost part of the Merrimack River

The Merrimack River (or Merrimac River, an occasional earlier spelling) is a river in the northeastern United States. It rises at the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipesaukee rivers in Franklin, New Hampshire, flows southward into Mas ...

. After the parliamentary victory in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bi ...

and installation of the Puritan Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

, a 1652 survey by the Massachusetts reported the source of the Merrimack as Lake Winnipesaukee

Lake Winnipesaukee () is the largest lake in the U.S. state of New Hampshire, located in the Lakes Region at the foothills of the White Mountains. It is approximately long (northwest-southeast) and from wide (northeast-southwest), covering ...

, and set the boundary at three miles north of 43°40′12″N *which would put it at 43°43′12″N). Surveyors reckoned on the Maine coast this corresponded to Upper Clapboard Island in Casco Bay

Casco Bay is an inlet of the Gulf of Maine on the southern coast of Maine, New England, United States. Its easternmost approach is Cape Small and its westernmost approach is Two Lights in Cape Elizabeth. The city of Portland sits along its ...

, just north of modern-day Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropo ...

. This meant Massachusetts' patent encompassed all the English colonial settlements in the Mason's lands (New Hampshire), and both Lygonia and Gorges' lands (western Maine, which ended around modern-day Bath, Maine

Bath is a city in Sagadahoc County, Maine, in the United States. The population was 8,766 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Sagadahoc County, which includes one city and 10 towns. The city is popular with tourists, many drawn by its ...

). The Parliamentarian, Puritan colony of Massachusetts sent commissioners to the Anglican, Royalist colonies to enforce jurisdiction. Opponents were arrested and jailed until the leader of the resistance, Edward Godfrey, capitulated.

Both Gorges' Province of Maine and Lygonia had been absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

by 1658. The Massachusetts claim would be overturned in 1676, but Massachusetts again asserted control by purchasing the territorial claims of the Gorges' heirs.

In 1669, the Territory of Sagadahock, between the Kennebec and St. Croix rivers (what is now eastern Maine) was granted by Charles II to his brother James, Duke of York

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious ...

. Under the terms of this grant, all the territory from the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

to the Atlantic Ocean was constituted as Cornwall County, and was governed as part of the duke's proprietary Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the U ...

. At times, this territory was claimed by New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

as part of Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

.

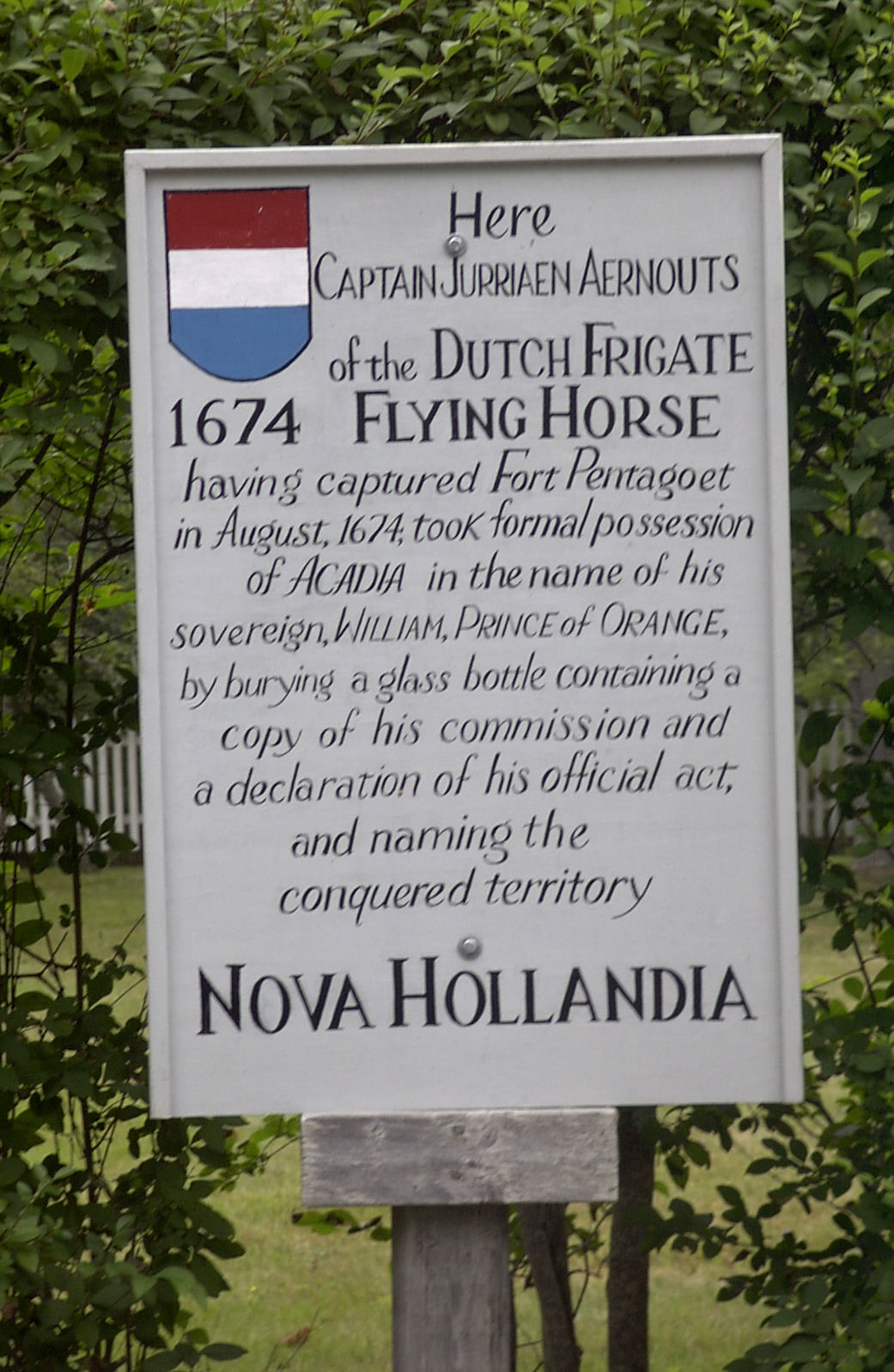

In 1674, the Dutch briefly conquered Acadia, renaming the colony New Holland.

In 1686 James, now king, established the

In 1686 James, now king, established the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure repres ...

. This political entity eventually combined all of the English colonial territories from Delaware Bay

Delaware Bay is the estuary outlet of the Delaware River on the northeast seaboard of the United States. It is approximately in area, the bay's freshwater mixes for many miles with the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean.

The bay is bordered inland ...

to the St. Croix River. The dominion collapsed in 1689, and a new patent was issued by William III of England

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic f ...

and Mary II of England

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife A ...

in 1691. This became effective in 1692 when the territory between the Piscataqua and the St. Croix (all of modern Maine) became part of the new Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in British America which became one of the thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III and Mary II, the joint monarchs of the kingdoms of ...

as Yorkshire, a name which survives in present-day York County.

Eastern border wars

For English settlers, the east of theKennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 river within the U.S. state of Maine. It rises in Moosehead ...

was known in the 17th century as the Territory of Sagadahock; however, the French included this area as part of Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

. It was dominated by tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of four principal Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet ( ...

, which supported Acadia. The only significant European presence was at Fort Pentagouet, the French trading post first established in 1613 as well as missionaries on Kennebec River and the Penobscot River. Fort Pentagouet was briefly the capital of Acadia (1670–1674) in an effort to protect the French claim to the territory. There were four wars before the region was finally taken by English settlers in Father Rale's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

.

In the first war, King Philips War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

, some of the tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy participated and successfully prevented English colonial settlement in their territory. During the next war, King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Alli ...

, Baron St. Castin at Fort Pentagouet and French Jesuit missionary Sébastien Rale were notably active. Again, the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of four principal Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet ( ...

executed a successful campaign against the English settlers west of the Kennebec River. In 1696, the major defensive establishment in the territory, Fort William Henry at Pemaquid (present-day Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

), was besieged by a French force. The territory was again on the front lines in Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

(1702–1713), with the Northeast Coast Campaign.

The next and final conflict over the New England/ Acadia border was Father Rale's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

. During the war, the Confederacy launched two campaigns against the British settlers west of the Kennebec (1723, 1724). Rale and numerous chiefs were killed by a New England force in 1724 at Norridgewock

Norridgewock was the name of both an Indigenous village and a band of the Abenaki ("People of the Dawn") Native Americans/ First Nations, an Eastern Algonquian tribe of the United States and Canada. The French of New France called the village ...

, which led to the collapse of French claims to Maine.

During King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

, members of the Wabanaki Confederacy led three campaigns against the British settlers in Maine (1745, 1746, 1747).

During the final colonial war, the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

, members of the Confederacy again executed numerous raids into Maine from Acadia/ Nova Scotia. Acadian militia raided the British colonial settlements of Swan's Island, Maine

Swan's Island is an island town in Hancock County, Maine. It is named after Colonel James Swan of Fife, Scotland, who purchased the island and some surrounding areas and organized their colonization in the eighteenth century. The population w ...

and present-day Friendship, Maine and Thomaston, Maine

Thomaston (formerly known as Fort St. Georges, Fort Wharf, Lincoln) is a town in Knox County, Maine, United States. The population was 2,739 at the 2020 census. Noted for its antique architecture, Thomaston is an old port popular with touris ...

. Francis Noble wrote her captivity narrative after being captured at Swan's Island. On June 9, 1758, Indians raided Woolwich, Maine, killing members of the Preble family and taking others prisoner to Quebec. This incident became known as the last conflict on the Kennebec River.

After the defeat of the French colony of Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

, the territory from the Penobscot River

The Penobscot River (Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 22, 2011 river in the U.S. state of Maine. Including the river's ...

east fell under the nominal authority of the Province of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, and together with present-day New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

formed the Nova Scotia County of Sunbury, with its court of general sessions at Campobello Island.

Land sales

In the late 18th century, several tracts of land in Maine, then part of Massachusetts, were sold off by lottery. Two tracts of 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km2), one in south-east Maine and another in the west, were bought by a wealthy Philadelphia banker, William Bingham. This land became known as theBingham Purchase

The Bingham Purchase refers to several tracts of land in the U.S. state of Maine,http://www.rootsweb.com/~mefrankl/ Franklin County, Maine Genealogy formerly owned by William Bingham.

These lands were granted to early colonizers in the 1630s, an ...

.http://newenglandtowns.org/maine/franklin-county "Franklin County, Maine", ''New England Towns''. Retrieved: 11-22-2007

American Revolution

Maine was a center of Patriotism during theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, with less Loyalist activity than most colonies. Merchants operated 52 ships that served as privateers attacking British supply ships. Machias in particular was a center for privateering and Patriot activity. It was the site of an early naval engagement that resulted in the capture of a small Royal Navy vessel. Jonathan Eddy led a failed attempt to capture Fort Cumberland in Nova Scotia in 1776. In 1777 Eddy led the defense of Machias against a Royal Navy raid.

Captain Henry Mowat of the Royal Navy had charge of operations off the Maine coast during much the war. He dismantled Fort Pownall at the mouth of the Penobscot River and burned Falmouth in 1775 (present-day Portland). His reputation in Maine traditions is heartless and brutal, but historians note that he performed his duty well and in accordance with the ethics of the era.

New Ireland

In 1779, the British adopted a strategy to occupy parts of Maine, especially around Penobscot Bay, and make it a new colony to be called "New Ireland". The scheme was promoted by exiled Loyalists Dr. John Calef (1725–1812) and John Nutting (fl. 1775-85), as well as Englishman William Knox (1732–1810). It was intended to be a permanent colony for Loyalists and a base for military action during the war. The plan ultimately failed because of a lack of interest by the British government and the determination of the Americans to keep all of Maine. In July 1779, British general Francis McLean captured Castine and built Fort George on the Bagaduce Peninsula on the eastern side of Penobscot Bay. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts sent thePenobscot Expedition

The Penobscot Expedition was a 44-ship American naval armada during the Revolutionary War assembled by the Provincial Congress of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The flotilla of 19 warships and 25 support vessels sailed from Boston on July 1 ...

led by Massachusetts general Solomon Lovell and Continental Navy captain Dudley Saltonstall. The Americans failed to dislodge the British during a 21-day siege and were routed by the arrival of British reinforcements. The Royal Navy blocked an escape by sea so the Patriots burned their ships near present-day Bangor and walked home. Maine was unable to repel the British threat despite a reorganized defense and the imposition of martial law in selected areas. Some of the most easterly towns tried to become neutral.

After the peace was signed in 1783, the New Ireland proposal was abandoned. In 1784 the British split New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

off from Nova Scotia and made it into the desired Loyalist colony, with deference to King and Church, and with republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

suppressed. It was almost named "New Ireland".

The 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolutionary War ceded western Sunbury County (west of the St. Croix River) from Nova Scotia to Massachusetts, which had an overlapping claim. The treaty was ambiguous about the inland boundary between what came to be known as the District of Maine and the neighboring British provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec. This would set the stage for the bloodless "Aroostook War

The Aroostook War (sometimes called the Pork and Beans WarLe Duc, Thomas (1947). The Maine Frontier and the Northeastern Boundary Controversy. ''The American Historical Review'' Vol. 53, No. 1 (Oct., 1947), pp. 30–41), or the Madawaska War, wa ...

" a half century later.

War of 1812

During theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, Maine suffered the effects of warfare less than most sections of New England. Early in the war there was some Canadian privateering action and Royal Navy harassment along the coast. In September 1813, the memorable combat off Pemaquid between HMS ''Boxer'' and USS ''Enterprise'' gained international attention. But it wasn't until 1814 that the district was invaded. The U.S. Army and the small U.S. Navy could do little to defend Maine. The national administration assigned nominal resources to the region, concentrating its efforts in the west. The local militia generally proved inadequate to the challenge.

However, in the last months of the war, large militia mobilizations discouraged enemy interventions at Wiscasset, Bath, and Portland. British army and naval forces from nearby Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

captured and occupied the eastern coast from Eastport to Castine, and plundered the Penobscot River

The Penobscot River (Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 22, 2011 river in the U.S. state of Maine. Including the river's ...

towns of Hampden and Bangor (see Battle of Hampden). Legitimate commerce all along the Maine coast was largely stopped—a critical situation for a place so dependent on shipping. In its place an illicit smuggling trade with the British developed, especially at Castine and Eastport. The British gave "New Ireland" to America in the Treaty of Ghent, and Castine was evacuated, although Eastport remained under occupation until 1818. But Maine's vulnerability to foreign invasion, and its lack of protection by Massachusetts, were important factors in the post-war momentum for statehood.

Maine statehood

TheMassachusetts General Court

The Massachusetts General Court (formally styled the General Court of Massachusetts) is the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name "General Court" is a hold-over from the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, ...

passed enabling legislation on June 19, 1819 separating the District of Maine from the rest of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The following month, on July 26, voters in the district approved statehood by 17,091 to 7,132.

The results of the election were presented to the Massachusetts Governor's Council on August 24, 1819.The Maine Register and United States' Almanac for the Year of Our Lord 1820, p. 72/ref> The Maine Constitution was unanimously approved by the 210 delegates to the Maine Constitutional Convention in October 1819. On February 25, 1820, the General Court passed a follow-up measure officially accepting the fact of Maine's imminent statehood. At the time of Maine's request for statehood, there were an equal number of

free and slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

. Pro-slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

members of the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

saw the admission of another free state, Maine, as a threat to the balance between slave and free states. They would only support statehood for Maine if Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812, until August 10, 1821. In 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was created from a portion of its southern area. In 1821, a southea ...

, where slavery was legal, would be admitted to the Union as a slave state. Maine became the nation's 23rd state on March 15, 1820, following the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

, which allowed Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

to enter the Union as a slave-holding state and Maine as a free state. However, Massachusetts still held onto the vast offshore islands of Maine after allowing it to secede, because of the high number of people on them who still wished to remain part of Massachusetts. This only lasted until 1824, when the cost of supplying the islands that were now very hard to access directly from Massachusetts outweighed any profit from holding onto those islands. Massachusetts formally ceded the last of its islands near Maine in late 1824.

William King William King may refer to:

Arts

* Willie King (1943–2009), American blues guitarist and singer

*William King (author) (born 1959), British science fiction author and game designer, also known as Bill King

*William King (artist) (1925–2015), Am ...

was elected as the state's first Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

. William D. Williamson became the first President of the Maine State Senate

The Maine Senate is the upper house of the Maine Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maine. The Senate currently consists of 35 members representing an equal number of districts across the state, though the Maine Constitution ...

. When King resigned as governor in 1821, Williamson automatically succeeded him to become Maine's second governor. That same year, however, he ran for and won a seat in the 17th United States Congress

The 17th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. While its term was officially March 4, 1821 ...

. Upon Williamson's resignation, Speaker of the Maine House of Representatives

The Maine House of Representatives is the lower house of the Maine Legislature. The House consists of 151 voting members and three nonvoting members. The voting members represent an equal number of districts across the state and are elected via ...

Benjamin Ames became Maine's third governor for approximately a month until Daniel Rose took office. Rose served only from January 2 to January 5, 1822, filling the unexpired term between the administrations of Ames and Albion K. Parris. Parris served as governor until January 3, 1827.

The Aroostook War

The still-lingering border dispute withBritish North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

came to a head in 1839 when Maine Governor John Fairfield

John Fairfield (January 30, 1797December 24, 1847) was an attorney and politician from Maine. He served as a U.S. Congressman, governor and U.S. Senator.

was born in Pepperellborough, Massachusetts (now Saco, Maine) and attended the schools ...

declared virtual war on lumbermen from New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

cutting timber in lands claimed by Maine. Four regiments of the Maine militia were mustered in Bangor and marched to the border, but there was no fighting. The Aroostook War

The Aroostook War (sometimes called the Pork and Beans WarLe Duc, Thomas (1947). The Maine Frontier and the Northeastern Boundary Controversy. ''The American Historical Review'' Vol. 53, No. 1 (Oct., 1947), pp. 30–41), or the Madawaska War, wa ...

was an undeclared and bloodless conflict that was settled by diplomacy.

Secretary of State Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

secretly funded a propaganda campaign that convinced Maine leaders that a compromise was wise; Webster used an old map that showed British claims were legitimate. The British had a different old map that showed the American claims were legitimate, so both sides thought the other had the better case. The final border between the two countries was established with the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842, which gave Maine most of the disputed area, and gave the British a militarily vital connection between its provinces of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

(present-day Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

and Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

) and New Brunswick.

The passion of the Aroostook War signaled the increasing role lumbering and logging were playing in the Maine economy, particularly in the central and eastern sections of the state. Bangor arose as a lumbering boom-town in the 1830s, and a potential demographic and political rival to Portland. Bangor became for a time the largest lumber port in the world, and the site of furious land speculation that extended up the Penobscot River valley and beyond.

Industrialization

Industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

in 19th century Maine took a number of forms, depending on the region and period. The river valleys, particularly the Androscroggin, Kennebec and Penobscot, became virtual conveyor belts for the making of lumber beginning in the 1820s-30s. Logging crews penetrated deep into the Maine woods in search of pine (and later spruce) and floated it down to sawmills gathered at waterfalls. The lumber was then shipped from ports such as Bangor, Ellsworth and Cherryfield all over the world.

Partly because of the lumber industry's need for transportation, and partly due to the prevalence of wood and carpenters along a very long coastline, shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to bef ...

became an important industry in Maine's coastal towns. The Maine merchant marine was huge in proportion to the state's population, and ships and crews from communities such as Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, Brewer

Brewing is the production of beer by steeping a starch source (commonly cereal grains, the most popular of which is barley) in water and fermenting the resulting sweet liquid with yeast. It may be done in a brewery by a commercial brewer ...

, and Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

could be found all over the world. The building of very large wooden sailing ships continued in some places into the early 20th century.

Cotton textile mills migrated to Maine from Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

beginning in the 1820s. The major site for cotton textile manufacturing was Lewiston on the Androscoggin River

The Androscoggin River (Abenaki: ''Aləssíkαntekʷ'') is a river in the U.S. states of Maine and New Hampshire, in northern New England. It is U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Ma ...

, the most northerly of the Waltham-Lowell system

The Waltham-Lowell system was a labor and production model employed during the rise of the textile industry in the United States, particularly in New England, amid the larger backdrop of rapid expansion of the Industrial Revolution in the early 1 ...

towns (factory towns modeled on Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell () is a city in Massachusetts, in the United States. Alongside Cambridge, It is one of two traditional seats of Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in 2020, it was the fifth most populous city in Massachusetts as ...

). The twin cities of Biddeford

Biddeford is a city in York County, Maine, United States. It is the principal commercial center of York County. Its population was 22,552 at the 2020 census. The twin cities of Saco and Biddeford include the resort communities of Biddeford Poo ...

and Saco, as well as Augusta, Waterville, and Brunswick also became important textile manufacturing communities. These mills were established on waterfalls and amidst farming communities as they initially relied on the labor of farm-girls engaged on short-term contracts. In the years after the Civil War, they would become magnets for immigrant labor.

In addition to fishing, important 19th century industries included granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

and slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

quarrying, brick-making

A brickworks, also known as a brick factory, is a factory for the manufacturing of bricks, from clay or shale. Usually a brickworks is located on a clay bedrock (the most common material from which bricks are made), often with a quarry for cl ...

, and shoe-making.

Starting in the early 20th century, the pulp and paper industry

The pulp and paper industry comprises companies that use wood as raw material and produce Pulp (paper), pulp, paper, paperboard and other cellulose-based products.

Manufacturing process

The pulp is fed to a paper machine where it is formed as ...

spread into the Maine woods and most of the river valleys from the lumbermen, so completely that Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American political activist, author, lecturer, and attorney noted for his involvement in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes.

The son of Lebanese immigrants to the Un ...

would famously describe Maine in the 1960s as a "paper plantation". Entirely new cities, such as Millinocket

Millinocket is a town in Penobscot County, Maine, United States. The population was 4,114 at the 2020 census.

Millinocket's economy has historically been centered on forest products and recreation, but the paper company closed in 2008.

History ...

and Rumford were established on many of the large rivers.

For all this industrial development, however, Maine remained a largely agricultural state well into the 20th century, with most of its population living in small and widely separated villages. With short growing seasons, rocky soil, and relative remoteness from markets, Maine agriculture was never as prosperous as in other states; the populations of most farming communities peaked in the 1850s, declining steadily thereafter.

Railroads

Railroads shaped Maine's geography, as they did that of most American states. The first railroad in Maine was the Calais Railroad, incorporated by the state legislature on February 17, 1832. It was built to transport lumber from a mill on the Saint Croix River opposite Milltown, New Brunswick two miles to the tidewater atCalais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

in 1835. In 1849, the name was changed to the Calais and Baring Railroad and the line was extended four more miles to Baring. In 1870, it became part of the St. Croix and Penobscot Railroad.

The state's second railroad was the Bangor & Piscataquis Railroad & Canal Company incorporated by the legislature on February 18, 1833. It ran eleven miles from Bangor to Oldtown along the west bank of the Penobscot River and opened in November, 1836. In 1854-55, it was extended 1.5 miles across the Penobscot River to Milford and the name was changed to the Bangor, Oldtown & Milford Railroad Company. In 1869, it was absorbed into the European and North American Railway

The European and North American Railway (E&NA) is the name for three historic Canadian and American railways which were built in New Brunswick and Maine.

The idea of the E&NA as a single system was conceived at a railway conference in Portland, M ...

.

The third railroad in Maine was the Portland, Saco and Portsmouth Railroad, incorporated by the legislature on March 14, 1837. This was a crucial step in the development of railroads in Maine because the new railroad connected Portland to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

by connecting to the Eastern Railroad

The Eastern Railroad was a railroad connecting Boston, Massachusetts to Portland, Maine. Throughout its history, it competed with the Boston and Maine Railroad for service between the two cities, until the Boston & Maine put an end to the compet ...

at Kittery via a bridge to Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

. This railroad was opened on November 21, 1842 and was 51.34 miles in length.

Portland in particular prospered as the terminus of the Grand Trunk railroad from Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, essentially becoming Canada's winter port because of efforts by investors like John A. Poor and John Neal. The Portland Company built early railway locomotives and the Portland Terminal Company

The Portland Terminal Company was a terminal railroad notable for its control of switching (shunting) activity for the Maine Central Railroad (MEC) and Boston & Maine (B&M) railroads in the Maine cities of Portland, South Portland, and Westbro ...

handled joint switching operations for the Maine Central Railroad and Boston and Maine Railroad. A railroad pushed through to Bangor in the 1850s, and as far as Aroostook County

Aroostook County ( ; french: Comté d'Aroostook) is a county in the U.S. state of Maine along the Canada–U.S. border. As of the 2020 census, the population was 67,105. Its county seat is Houlton, with offices in Caribou and Fort Kent.

...

in the early 20th century, farming potato growing as a cash crop.

Belfast and Moosehead Lake Railroad

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingd ...

was chartered in 1867 and opened in 1870. Despite the aspirational name its 33 miles of standard gauge

A standard-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge of . The standard gauge is also called Stephenson gauge (after George Stephenson), International gauge, UIC gauge, uniform gauge, normal gauge and European gauge in Europe, and SGR in E ...

tracks connected the port of Belfast to Burnham Junction where they joined with the newly created Maine Central Railroad Company

The Maine Central Railroad Company was a United States, U. S. Class I railroad in central and southern Maine. It was chartered in 1856 and began operations in 1862. By 1884, Maine Central was the longest railroad in New England. Maine Central had ...

. Maine Central promptly took a 50 year lease on the B&MLR to haul passengers and freight in and out of Waldo County. In 1925 Maine Central declined to renew their lease, citing losses, and the City of Belfast began operating the B&MLR as the only publicly owned freight and passenger rail line in the US.

The Sandy River and Rangeley Lakes Railroad, Bridgton and Saco River Railroad

The Bridgton and Saco River Railroad (B&SR) was a narrow gauge railroad that operated in the vicinity of Bridgton and Harrison, Maine. It connected with the Portland and Ogdensburg Railroad (later Maine Central Railroad Mountain Division) from ...

, Monson Railroad

The Monson Railroad was a narrow gauge railway, which operated between Monson Junction on the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad and Monson, Maine. The primary purpose of this railroad was to serve several slate mines and finishing houses in Mons ...

, Kennebec Central Railroad

The Kennebec Central Railroad was a narrow gauge railroad operating between Randolph and Togus, Maine. The railroad was built to offer transportation for American Civil War veterans living at Togus to the nearby City of Gardiner.Barney(1986 ...

and Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington Railway were built with the unusually narrow gauge of 2 feet (60 cm).

"Ohio Fever", the California Gold Rush, and westward migration from Maine

Even before the tide of settlement crested in most of Maine, some began to leave for The West. The first large-scale exodus was probably in 1816-17, spurred by the privations of the War of 1812, an unusually cold summer, and the expansion of settlement west of theAppalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

in Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

. "Ohio Fever" as the lure of the West was initially called, depopulated a number of fledgling Maine communities and stunted the growth of others, even if the overall momentum of settlement had been largely restored by the 1820s, when Maine achieved statehood.

As the American frontier continued to expand westward, Mainers were particularly attracted to the forested states of Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and t ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, and Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

, and large numbers brought their lumbering skills and knowledge there. Migrants from Maine were particularly prominent in Minnesota; for example, three 19th century Mayors of Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

were Mainers.

The California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

of 1849 and afterwards was a major boost to the lumber and coastal shipbuilding economies, as building lumber needed to be "shipped around the Horn" from Maine until the establishment of a West Coast sawmilling industry. Maine ships also carried gold-seeking migrants, however, and thus were many Mainers (and aspects of Maine culture, such as lumbering and carpentering) transplanted to California and the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Thou ...

. Three 19th century Mayors of San Francisco