History of London (1900–39) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Londinium'' was established as a civilian town by the

''Londinium'' was established as a civilian town by the

Around this time the focus of settlement moved within the old Roman walls for the sake of defence, and the city became known as '' Lundenburh''. The Roman walls were repaired and the defensive ditch re-cut, while the bridge was probably rebuilt at this time. A second fortified

Around this time the focus of settlement moved within the old Roman walls for the sake of defence, and the city became known as '' Lundenburh''. The Roman walls were repaired and the defensive ditch re-cut, while the bridge was probably rebuilt at this time. A second fortified

The new Norman regime established new fortresses within the city to dominate the native population. By far the most important of these was the

The new Norman regime established new fortresses within the city to dominate the native population. By far the most important of these was the  During the

During the

In 1475, the Hanseatic League set up its main English trading base (''

In 1475, the Hanseatic League set up its main English trading base ('' Xenophobia was rampant in London, and increased after the 1580s. Many immigrants became disillusioned by routine threats of violence and molestation, attempts at expulsion of foreigners, and the great difficulty in acquiring English citizenship. Dutch cities proved more hospitable, and many left London permanently. Foreigners are estimated to have made up 4,000 of the 100,000 residents of London by 1600, many being Dutch and German workers and traders.

Xenophobia was rampant in London, and increased after the 1580s. Many immigrants became disillusioned by routine threats of violence and molestation, attempts at expulsion of foreigners, and the great difficulty in acquiring English citizenship. Dutch cities proved more hospitable, and many left London permanently. Foreigners are estimated to have made up 4,000 of the 100,000 residents of London by 1600, many being Dutch and German workers and traders.

In January 1642

In January 1642

The fire destroyed about 60% of the City, including Old St Paul's Cathedral, 87 parish churches, 44 livery company halls and the Royal Exchange. However, the number of lives lost was surprisingly small; it is believed to have been 16 at most. Within a few days of the fire, three plans were presented to the king for the rebuilding of the city, by Christopher Wren,

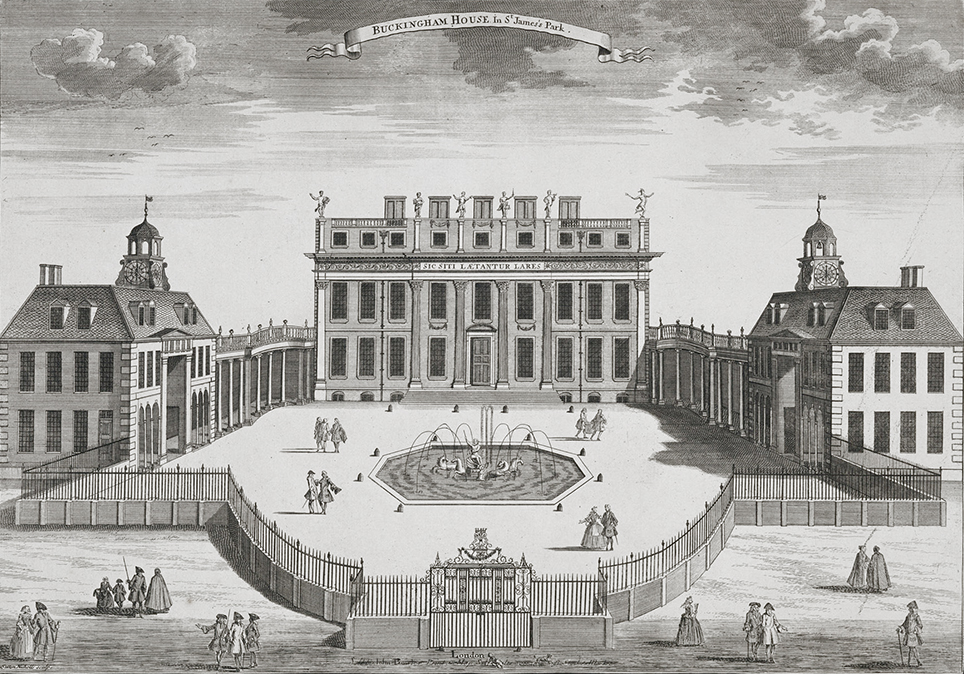

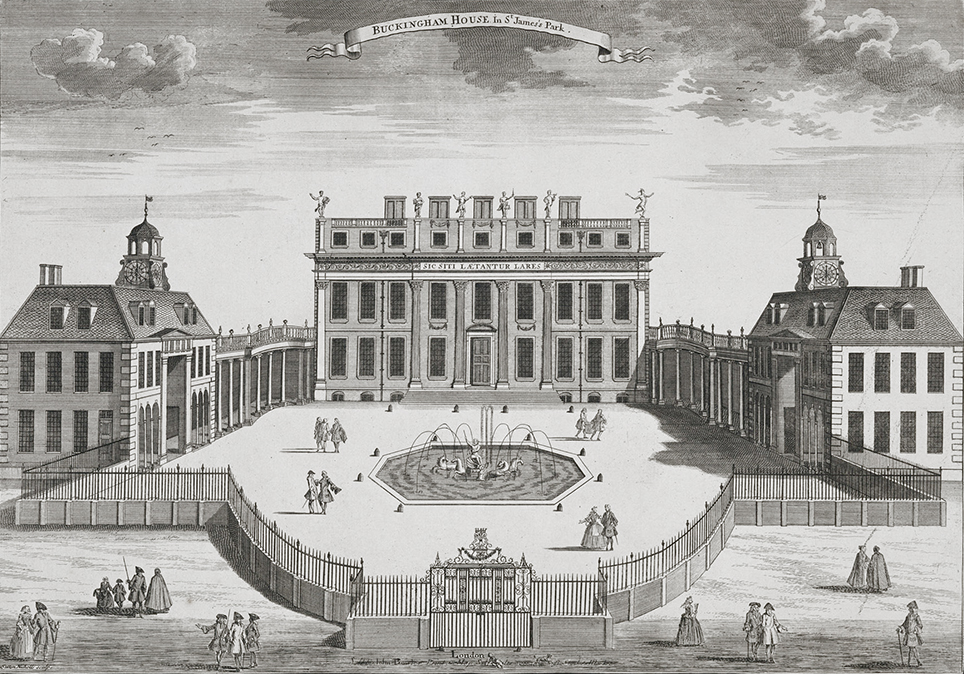

The fire destroyed about 60% of the City, including Old St Paul's Cathedral, 87 parish churches, 44 livery company halls and the Royal Exchange. However, the number of lives lost was surprisingly small; it is believed to have been 16 at most. Within a few days of the fire, three plans were presented to the king for the rebuilding of the city, by Christopher Wren,  Nonetheless, the new City was different from the old one. Many aristocratic residents never returned, preferring to take new houses in the West End, where fashionable new districts such as St. James's were built close to the main royal residence, which was

Nonetheless, the new City was different from the old one. Many aristocratic residents never returned, preferring to take new houses in the West End, where fashionable new districts such as St. James's were built close to the main royal residence, which was

Many tradesmen from different countries came to London to trade goods and merchandise. Also, more immigrants moved to London making the population greater. More people also moved to London for work and for business making London an altogether bigger and busier city. Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War increased the country's international standing and opened large new markets to British trade, further boosting London's prosperity.

During the Georgian period London spread beyond its traditional limits at an accelerating pace. This is shown in a series of detailed maps, particularly

Many tradesmen from different countries came to London to trade goods and merchandise. Also, more immigrants moved to London making the population greater. More people also moved to London for work and for business making London an altogether bigger and busier city. Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War increased the country's international standing and opened large new markets to British trade, further boosting London's prosperity.

During the Georgian period London spread beyond its traditional limits at an accelerating pace. This is shown in a series of detailed maps, particularly

A phenomenon of the era was the coffeehouse, which became a popular place to debate ideas. Growing literacy and the development of the

A phenomenon of the era was the coffeehouse, which became a popular place to debate ideas. Growing literacy and the development of the

During the 19th century, London was transformed into the world's largest city and capital of the British Empire. Its population expanded from 1 million in 1800 to 6.7 million a century later. During this period, London became a global political, financial, and trading capital. In this position, it was largely unrivalled until the latter part of the century, when

During the 19th century, London was transformed into the world's largest city and capital of the British Empire. Its population expanded from 1 million in 1800 to 6.7 million a century later. During this period, London became a global political, financial, and trading capital. In this position, it was largely unrivalled until the latter part of the century, when  As the capital of a massive empire, London became a magnet for immigrants from the colonies and poorer parts of Europe. A large Irish population settled in the city during the Victorian period, with many of the newcomers refugees from the Great Famine (1845–1849). At one point, Catholic Irish made up about 20% of London's population; they typically lived in overcrowded slums. London also became home to a sizable Jewish community, which was notable for its entrepreneurship in the clothing trade and merchandising.

In 1888, the new

As the capital of a massive empire, London became a magnet for immigrants from the colonies and poorer parts of Europe. A large Irish population settled in the city during the Victorian period, with many of the newcomers refugees from the Great Famine (1845–1849). At one point, Catholic Irish made up about 20% of London's population; they typically lived in overcrowded slums. London also became home to a sizable Jewish community, which was notable for its entrepreneurship in the clothing trade and merchandising.

In 1888, the new

London entered the 20th century at the height of its influence as the capital of one of the largest empires in history, but the new century was to bring many challenges.

London's population continued to grow rapidly in the early decades of the century, and

London entered the 20th century at the height of its influence as the capital of one of the largest empires in history, but the new century was to bring many challenges.

London's population continued to grow rapidly in the early decades of the century, and

During

During

Starting in the mid-1960s, and partly as a result of the success of such UK musicians as

Starting in the mid-1960s, and partly as a result of the success of such UK musicians as

Around the start of the 21st century, London hosted the much derided Millennium Dome at

Around the start of the 21st century, London hosted the much derided Millennium Dome at

First chapter

) * Ball, Michael, and David T. Sunderland. ''Economic history of London, 1800–1914'' (Routledge, 2002) * Billings, Malcolm (1994), ''London: A Companion to Its History and Archaeology'', * Bucholz, Robert O., and Joseph P. Ward. ''London: A Social and Cultural History, 1550–1750'' (Cambridge University Press; 2012) 526 pages * Clark, Greg. ''The Making of a World City: London 1991 to 2021'' (John Wiley & Sons, 2014) * Emerson, Charles. ''1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War'' (2013) compares London to 20 major world cities on the eve of World War I; pp 15 to 36, 431–49. * Inwood, Stephen. ''A History of London'' (1998) * Jones, Robert Wynn. ''The Flower of All Cities: The History of London from Earliest Times to the Great Fire'' (Amberley Publishing, 2019). * * Mort, Frank, and Miles Ogborn. "Transforming Metropolitan London, 1750–1960". ''Journal of British Studies'' (2004) 43#1 pp: 1–14. * Naismith, Rory, ''Citadel of the Saxons: The Rise of Early London'' (I.B.Tauris; 2018), * Porter, Roy. ''History of London'' (1995), by a leading scholar * Weightman, Gavin, and Stephen Humphries. ''The Making of Modern London, 1914–1939'' (Sidgwick & Jackson, 1984) * White, Jerry. ''London in the Twentieth Century: A City and Its People'' (2001) 544 pages; Social history of people, neighborhoods, work, culture, power

Excerpts

* White, Jerry. ''London in the Nineteenth Century: 'A Human Awful Wonder of God (2008); Social history of people, neighborhoods, work, culture, power

Excerpt and text search

* White, Jerry. ''London in the Eighteenth Century: A Great and Monstrous Thing'' (2013) 624 pages

Excerpt and text search

480pp; Social history of people, neighborhoods, work, culture, power. * Williams, Guy R. ''London in the Country: The Growth of Suburbia'' (Hamish Hamilton, 1975) *

online

* Jackson, Lee. ''Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth'' (2014) * Jørgensen, Dolly. "'All Good Rule of the Citee': Sanitation and Civic Government in England, 1400–1600". ''Journal of Urban History'' (2010)

online

* Landers, John. ''Death and the metropolis: studies in the demographic history of London, 1670–1830'' (1993). * Luckin, Bill, and Peter Thorsheim, eds. ''A Mighty Capital under Threat: The Environmental History of London, 1800-2000'' (U of Pittsburgh Press, 2020

online review

* Mosley, Stephen. "'A Network of Trust': Measuring and Monitoring Air Pollution in British Cities, 1912–1960". ''Environment and History'' (2009) 15#3 pp: 273–302. * Thorsheim, Peter. ''Inventing Pollution: Coal, Smoke, and Culture in Britain since 1800'' (2009)

Vol. 1Vol. 2Vol. 3Vol. 4Vol. 5Vol. 6

* *

London

' (Harper & Bros., 1892) * (thematic bibliography about London) *

v.2v.3Index

* *

– Article in the 1908 Catholic Encyclopædia

''A Chronicle of London from 1089 to 1483''

written in the fifteenth century

Roman London - "In their own words"

( PDF) A literary companion to the

London Lives 1690-1800

- A digital archive with personal records from lond during the 18th century

Exploring 20th-century London

– Explore London's history, culture and religions during the 20th century

The Victorian London

Collage - The London Picture Archive

Museum of London

London History

– From Britannia.com

The Growth of London 1666–1799

Maritime London

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of London

The history of

heads and weaponry from the Bronze and Iron Ages near the banks of the Thames in the London area, many of which had clearly been used in battle.

Archaeologist Leslie Wallace notes, "Because no LPRIA London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, the capital city of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, extends over 2000 years. In that time, it has become one of the world's most significant financial and cultural capital cities. It has withstood plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

, devastating fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition point, flames a ...

, civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, aerial bombardment

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighters, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters and drones. The offic ...

, terrorist attacks

The following is a list of terrorist incidents that have not been carried out by a state or its forces (see state terrorism and state-sponsored terrorism). Assassinations are listed at List of assassinated people.

Definitions of terrori ...

, and riots.

The City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

is the historic core of the Greater London metropolis, and is today its primary financial district, it represents only a small part of the wider metropolis.

Foundations and prehistory

Some recent discoveries indicate probable very early settlements near the Thames in the London area. In 1993, the remains of aBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

bridge were found on the Thames's south foreshore, upstream of Vauxhall Bridge

Vauxhall Bridge is a Grade II* listed steel and granite deck arch bridge in central London. It crosses the River Thames in a southeast–northwest direction between Vauxhall on the south bank and Pimlico on the north bank. Opened in 1906, i ...

. This bridge either crossed the Thames or went to a now lost island in the river. Dendrology

Dendrology ( grc, δένδρον, ''dendron'', "tree"; and grc, -λογία, ''-logia'', ''science of'' or ''study of'') or xylology ( grc, ξύλον, ''ksulon'', "wood") is the science and study of woody plants (trees, shrubs, and lianas), ...

dated the timbers to between 1750 BC and 1285 BC. In 2001, a further dig found that the timbers were driven vertically into the ground on the south bank of the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

west of Vauxhall Bridge.

In 2010, the foundations of a large timber structure, dated to between 4800 BC and 4500 BC were found, again on the foreshore south of Vauxhall Bridge. The function of the mesolithic structure is not known. All these structures are on the south bank at a natural crossing point where the River Effra

The River Effra is a former set of streams in south London, England, culverted and used mainly for storm sewerage. It had been a tributary of the Thames. Its catchment waters, where not drained to aquifer soakaways and surface water drains, ha ...

flows into the Thames.spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...ate pre-Roman Iron Age

Ate or ATE may refer to:

Organizations

* Active Training and Education Trust, a not-for-profit organization providing "Superweeks", holidays for children in the United Kingdom

* Association of Technical Employees, a trade union, now called the Nat ...

settlements or significant domestic refuse have been found in London, despite extensive archaeological excavation, arguments for a purely Roman foundation of London are now common and uncontroversial."

Early history

Roman London (47–410 AD)

''Londinium'' was established as a civilian town by the

''Londinium'' was established as a civilian town by the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

about four years after the invasion of 43 AD. London, like Rome, was founded on the point of the river where it was narrow enough to bridge and the strategic location of the city provided easy access to much of Europe. Early Roman London occupied a relatively small area, roughly equivalent to the size of Hyde Park. In around 60 AD, it was destroyed by the Iceni

The Iceni ( , ) or Eceni were a Brittonic tribe of eastern Britain during the Iron Age and early Roman era. Their territory included present-day Norfolk and parts of Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, and bordered the area of the Corieltauvi to the we ...

led by their queen Boudica. The city was quickly rebuilt as a planned Roman town and recovered after perhaps 10 years; the city grew rapidly over the following decades.

Although some sources claim that during the 2nd century ''Londinium'' replaced Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colch ...

as the capital of Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

(Britannia) there is no surviving evidence to prove it was ever the capital of Roman Britain. Its population was around 60,000 inhabitants. It boasted major public buildings, including the largest basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's Forum (Roman), forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building ...

north of the Alps, temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

, bath houses, an amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (British English) or amphitheater (American English; both ) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ...

and a large fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

for the city garrison. Political instability and recession from the 3rd century onwards led to a slow decline.

At some time between 180 AD and 225 AD, the Romans built the defensive London Wall

The London Wall was a defensive wall first built by the Romans around the strategically important port town of Londinium in AD 200, and is now the name of a modern street in the City of London. It has origins as an initial mound wall and ...

around the landward side of the city. The wall was about long, high, and thick. The wall would survive for another 1,600 years and define the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

's perimeters for centuries to come. The perimeters of the present City are roughly defined by the line of the ancient wall.

Londinium was an ethnically diverse city with inhabitants from across the Roman Empire, including natives of Britannia, continental Europe, the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, and North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

.

In the late 3rd century, Londinium was raided on several occasions by Saxon pirates. This led, from around 255 onwards, to the construction of an additional riverside wall. Six of the traditional seven city gates of London are of Roman origin, namely: Ludgate

Ludgate was the westernmost gate in London Wall. Of Roman origin, it was rebuilt several times and finally demolished in 1760. The name survives in Ludgate Hill, an eastward continuation of Fleet Street, Ludgate Circus and Ludgate Square.

Etym ...

, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate

Cripplegate was a gate in the London Wall which once enclosed the City of London.

The gate gave its name to the Cripplegate ward of the City which straddles the line of the former wall and gate, a line which continues to divide the ward into ...

, Bishopsgate and Aldgate

Aldgate () was a gate in the former defensive wall around the City of London. It gives its name to Aldgate High Street, the first stretch of the A11 road, which included the site of the former gate.

The area of Aldgate, the most common use of ...

(Moorgate

Moorgate was one of the City of London's northern gates in its defensive wall, the last to be built. The gate took its name from the Moorfields, an area of marshy land that lay immediately north of the wall.

The gate was demolished in 1762, bu ...

is the exception, being of medieval origin).

By the 5th century, the Roman Empire was in rapid decline and in 410 AD, the Roman occupation of Britannia came to an end. Following this, the Roman city also went into rapid decline and by the end of the 5th century was practically abandoned.

Anglo-Saxon London (5th century – 1066)

Until recently it was believed that Anglo-Saxon settlement initially avoided the area immediately around Londinium. However, the discovery in 2008 of an Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Covent Garden indicates that the incomers had begun to settle there at least as early as the 6th century and possibly in the 5th. The main focus of this settlement was outside the Roman walls, clustering a short distance to the west along what is now theStrand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

, between the Aldwych

Aldwych (pronounced ) is a street and the name of the area immediately surrounding it in central London, England, within the City of Westminster. The street starts east-northeast of Charing Cross, the conventional map centre-point of the city ...

and Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

. It was known as ''Lundenwic'', the ''-wic'' suffix here denoting a trading settlement. Recent excavations have also highlighted the population density and relatively sophisticated urban organisation of this earlier Anglo-Saxon London, which was laid out on a grid pattern and grew to house a likely population of 10–12,000.

Early Anglo-Saxon London belonged to a people known as the Middle Saxons

The Middle Saxons or Middel Seaxe were a people whose territory later became, with somewhat contracted boundaries, the county of Middlesex, England.

The first known mention of Middlesex stems from a royal charter of 704 between king Swæfred o ...

, from whom the name of the county of Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

is derived, but who probably also occupied the approximate area of modern Hertfordshire and Surrey. However, by the early 7th century the London area had been incorporated into the kingdom of the East Saxons

la, Regnum Orientalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the East Saxons

, common_name = Essex

, era = Heptarchy

, status =

, status_text =

, government_type = Monarch ...

. In 604 King Saeberht of Essex converted to Christianity and London received Mellitus

Saint Mellitus (died 24 April 624) was the first bishop of London in the Saxon period, the third Archbishop of Canterbury, and a member of the Gregorian mission sent to England to convert the Anglo-Saxons from their native paganism to Chris ...

, its first post-Roman bishop.

At this time Essex was under the overlordship of King Æthelberht of Kent

Æthelberht (; also Æthelbert, Aethelberht, Aethelbert or Ethelbert; ang, Æðelberht ; 550 – 24 February 616) was King of Kent from about 589 until his death. The eighth-century monk Bede, in his ''Ecclesiastical History of the Engli ...

, and it was under Æthelberht's patronage that Mellitus founded the first St. Paul's Cathedral, traditionally said to be on the site of an old Roman Temple of Diana (although Christopher Wren found no evidence of this). It would have only been a modest church at first and may well have been destroyed after he was expelled from the city by Saeberht's pagan successors.

The permanent establishment of Christianity in the East Saxon kingdom took place in the reign of King Sigeberht II in the 650s. During the 8th century, the kingdom of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879) Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era= Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ...

extended its dominance over south-eastern England, initially through overlordship which at times developed into outright annexation. London seems to have come under direct Mercian control in the 730s.

Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

attacks dominated most of the 9th century, becoming increasingly common from around 830 onwards. London was sacked in 842 and again in 851. The Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

"Great Heathen Army

The Great Heathen Army,; da, Store Hedenske Hær also known as the Viking Great Army,Hadley. "The Winter Camp of the Viking Great Army, AD 872–3, Torksey, Lincolnshire", ''Antiquaries Journal''. 96, pp. 23–67 was a coalition of Scandin ...

", which had rampaged across England since 865, wintered in London in 871. The city remained in Danish hands until 886, when it was captured by the forces of King Alfred the Great of Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

and reincorporated into Mercia, then governed under Alfred's sovereignty by his son-in-law Ealdorman Æthelred

Æthelred (; ang, Æþelræd ) or Ethelred () is an Old English personal name (a compound of '' æþele'' and '' ræd'', meaning "noble counsel" or "well-advised") and may refer to:

Anglo-Saxon England

* Æthelred and Æthelberht, legendary prin ...

.

Borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle A ...

was established on the south bank at Southwark, the ''Suthringa Geworc'' (defensive work of the men of Surrey). The old settlement of ''Lundenwic'' became known as the ''ealdwic'' or "old settlement", a name which survives today as Aldwich.

From this point, the City of London began to develop its own unique local government. Following Æthelred's death in 911 it was transferred to Wessex, preceding the absorption of the rest of Mercia in 918. Although it faced competition for political pre-eminence in the united Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, ...

from the traditional West Saxon centre of Winchester, London's size and commercial wealth brought it a steadily increasing importance as a focus of governmental activity. King Athelstan held many meetings of the ''witan'' in London and issued laws from there, while King Æthelred the Unready

Æthelred II ( ang, Æþelræd, ;Different spellings of this king’s name most commonly found in modern texts are "Ethelred" and "Æthelred" (or "Aethelred"), the latter being closer to the original Old English form . Compare the modern diale ...

issued the Laws of London there in 978.

Following the resumption of Viking attacks in the reign of Æthelred, London was unsuccessfully attacked in 994 by an army under King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark. As English resistance to the sustained and escalating Danish onslaught finally collapsed in 1013, London repulsed an attack by the Danes and was the last place to hold out while the rest of the country submitted to Sweyn, but by the end of the year it too capitulated and Æthelred fled abroad. Sweyn died just five weeks after having been proclaimed king and Æthelred was restored to the throne, but Sweyn's son Cnut

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norwa ...

returned to the attack in 1015.

After Æthelred's death at London in 1016 his son Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside (30 November 1016; , ; sometimes also known as Edmund II) was King of the English from 23 April to 30 November 1016. He was the son of King Æthelred the Unready and his first wife, Ælfgifu of York. Edmund's reign was marred by ...

was proclaimed king there by the '' witangemot'' and left to gather forces in Wessex. London was then subjected to a systematic siege by Cnut but was relieved by King Edmund's army; when Edmund again left to recruit reinforcements in Wessex the Danes resumed the siege but were again unsuccessful. However, following his defeat at the Battle of Assandun

The Battle of Assandun (or Essendune) was fought between Danish and English armies on 18 October 1016. There is disagreement whether Assandun may be Ashdon near Saffron Walden in north Essex, England, or, as long supposed and better evidenc ...

Edmund ceded to Cnut all of England north of the Thames, including London, and his death a few weeks later left Cnut in control of the whole country.

A Norse saga tells of a battle when King Æthelred returned to attack Danish-occupied London. According to the saga, the Danes lined London Bridge and showered the attackers with spears. Undaunted, the attackers pulled the roofs off nearby houses and held them over their heads in the boats. Thus protected, they were able to get close enough to the bridge to attach ropes to the piers and pull the bridge down, thus ending the Viking occupation of London. This story presumably relates to Æthelred's return to power after Sweyn's death in 1014, but there is no strong evidence of any such struggle for control of London on that occasion.

Following the extinction of Cnut's dynasty in 1042 English rule was restored under Edward the Confessor. He was responsible for the foundation of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

and spent much of his time at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, which from this time steadily supplanted the City itself as the centre of government. Edward's death at Westminster in 1066 without a clear heir led to a succession dispute and the Norman conquest of England. Earl Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the ...

was elected king by the ''witangemot'' and crowned in Westminster Abbey but was defeated and killed by William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy at the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings nrf, Batâle dé Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conque ...

. The surviving members of the ''witan'' met in London and elected King Edward's young nephew Edgar the Ætheling

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and '' gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, r ...

as king.

The Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

advanced to the south bank of the Thames opposite London, where they defeated an English attack and burned Southwark but were unable to storm the bridge. They moved upstream and crossed the river at Wallingford before advancing on London from the north-west. The resolve of the English leadership to resist collapsed and the chief citizens of London went out together with the leading members of the Church and aristocracy to submit to William at Berkhamstead

Berkhamsted ( ) is a historic market town in Hertfordshire, England, in the Bulbourne valley, north-west of London. The town is a civil parish with a town council within the borough of Dacorum which is based in the neighbouring large new town ...

, although according to some accounts there was a subsequent violent clash when the Normans reached the city. Having occupied London, William was crowned king in Westminster Abbey.

Norman and Medieval London (1066 – late 15th century)

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

at the eastern end of the city, where the initial timber fortification was rapidly replaced by the construction of the first stone castle in England. The smaller forts of Baynard's Castle

Baynard's Castle refers to buildings on two neighbouring sites in the City of London, between where Blackfriars station and St Paul's Cathedral now stand. The first was a Norman fortification constructed by Ralph Baynard ( 1086), 1st feudal ...

and Montfichet's Castle

Montfichet's Tower (also known as Montfichet's Castle and/or spelt Mountfitchet's or Mountfiquit's) was a Norman fortress on Ludgate Hill in London, between where St Paul's Cathedral and City Thameslink railway station now stand. First documente ...

were also established along the waterfront. King William also granted a charter in 1067 confirming the city's existing rights, privileges and laws. London was a centre of England's nascent Jewish population

As of 2020, the world's "core" Jewish population (those identifying as Jews above all else) was estimated at 15 million, 0.2% of the 8 billion worldwide population. This number rises to 18 million with the addition of the "connected" Jewish pop ...

, the first of whom arrived in about 1070. Its growing self-government was consolidated by the election rights granted by King John in 1199 and 1215.

On 17 October 1091 a tornado

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, altho ...

rated T8 on the TORRO

The Tornado and Storm Research Organisation (TORRO) was founded by Terence Meaden in 1974. Originally called the Tornado Research Organisation it was expanded in 1982 following the inclusion of the Thunderstorm Census Organisation (TCO) after the d ...

scale (equivalent to an F4 on the Fujita scale

The Fujita scale (F-Scale; ), or Fujita–Pearson scale (FPP scale), is a scale for rating tornado intensity, based primarily on the damage tornadoes inflict on human-built structures and vegetation. The official Fujita scale category is deter ...

) hit London; it directly struck the church of St. Mary-le-Bow; four rafter

A rafter is one of a series of sloped structural members such as wooden beams that extend from the ridge or hip to the wall plate, downslope perimeter or eave, and that are designed to support the roof shingles, roof deck and its associated ...

s 7.9 meters long (26 feet) were said to have been buried so deep into the ground that only 1.2 meters (4 feet) was visible. Other churches in the area were destroyed as well; it was reported to have also destroyed over 600 houses (although most of them were primarily wood) and hit the London Bridge, after the tornado the bridge was rebuilt in stone. The tornado caused 2 deaths and an unknown number of injuries; this tornado is mentioned in chronicles by Florence of Worcester Florence of Worcester (died 1118), known in Latin as Florentius, was a monk of Worcester, who played some part in the production of the '' Chronicon ex chronicis'', a Latin world chronicle which begins with the creation and ends in 1140.Keynes, "Fl ...

and William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury ( la, Willelmus Malmesbiriensis; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as " ...

, the latter of the two describing it as "a great spectacle for those watching from afar, but a terrifying experience for those standing near".

In 1097, William Rufus

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

, the son of William the Conqueror, began the construction of 'Westminster Hall', which became the focus of the Palace of Westminster.

In 1176, construction began of the most famous incarnation of London Bridge (completed in 1209), which was built on the site of several earlier timber bridges. This bridge would last for 600 years, and remained the only bridge across the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

until 1739.

Violence against Jews took place in 1190, after it was rumoured that the new King had ordered their massacre after they had presented themselves at his coronation.

In 1216, during the First Barons' War

The First Barons' War (1215–1217) was a civil war in the Kingdom of England in which a group of rebellious major landowners (commonly referred to as barons) led by Robert Fitzwalter waged war against King John of England. The conflict resulte ...

London was occupied by Prince Louis of France, who had been called in by the baronial rebels against King John and was acclaimed as King of England in St Paul's Cathedral. However, following John's death in 1217 Louis's supporters reverted to their Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in ...

allegiance, rallying round John's son Henry III, and Louis was forced to withdraw from England.

In 1224, after an accusation of ritual murder

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of veneration of the dead, dead ancestors or as ...

, the Jewish community was subjected to a steep punitive levy. Then in 1232, Henry III confiscated the principal synagogue of the London Jewish community because he claimed their chanting was audible in a neighboring church. In 1264, during the Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in England between the forces of a number of barons led by Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of King Henry III, led initially by the king himself and later by his son, the fu ...

, Simon de Montfort

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester ( – 4 August 1265), later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was a nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the ...

's rebels occupied London and killed 500 Jews while attempting to seize records of debts.; see p. 88–99

London's Jewish community was forced to leave England by the expulsion

Expulsion or expelled may refer to:

General

* Deportation

* Ejection (sports)

* Eviction

* Exile

* Expeller pressing

* Expulsion (education)

* Expulsion from the United States Congress

* Extradition

* Forced migration

* Ostracism

* Persona non ...

by Edward I in 1290. They left for France, Holland and further afield; their property was seized, and many suffered robbery and murder as they departed.

Over the following centuries, London would shake off the heavy French cultural and linguistic influence which had been there since the times of the Norman conquest. The city would figure heavily in the development of Early Modern English

Early Modern English or Early New English (sometimes abbreviated EModE, EMnE, or ENE) is the stage of the English language from the beginning of the Tudor period to the English Interregnum and Restoration, or from the transition from Middle E ...

.

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Blac ...

of 1381, London was invaded by rebels led by Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler (c. 1320/4 January 1341 – 15 June 1381) was a leader of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England. He led a group of rebels from Canterbury to London to oppose the institution of a poll tax and to demand economic and social reforms. Wh ...

. A group of peasants stormed the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

and executed the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, Archbishop Simon Sudbury

Simon Sudbury ( – 14 June 1381) was Bishop of London from 1361 to 1375, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1375 until his death, and in the last year of his life Lord Chancellor of England. He met a violent death during the Peasants' Revolt in 1 ...

, and the Lord Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State i ...

. The peasants looted the city and set fire to numerous buildings. Tyler was stabbed to death by the Lord Mayor William Walworth

Sir William Walworth (died 1385) was an English nobleman and politician who was twice Lord Mayor of London (1374–75 and 1380–81). He is best known for killing Wat Tyler during the Peasants' Revolt in 1381.

Political career

His family ca ...

in a confrontation at Smithfield and the revolt collapsed.

Trade increased steadily during the Middle Ages, and London grew heavily as a result. In 1100, London's population was somewhat more than 15,000. By 1300, it had grown to roughly 80,000. London lost at least half of its population during the Black Death in the mid-14th century, but its economic and political importance stimulated a quick recovery despite further epidemics. Trade in London was organised into various guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s, which effectively controlled the city, and elected the Lord Mayor of the City of London

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

.

Medieval London was made up of narrow and twisting streets, and most of the buildings were made from combustible materials such as timber and straw, which made fire a constant threat, while sanitation in cities was of low-quality.

Modern history

Tudor London (1485–1604)

In 1475, the Hanseatic League set up its main English trading base (''

In 1475, the Hanseatic League set up its main English trading base (''kontor

A ''kontor'' () was a foreign trading post of the Hanseatic League.

In addition to the major ''kontore'' in London (the Steelyard), Bruges, Bergen (Bryggen), and Novgorod (Peterhof), some ports had a representative merchant and a warehouse.

E ...

'') in London, called ''Stalhof'' or '' Steelyard''. It existed until 1853, when the Hanseatic cities of Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

, Bremen and Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

sold the property to South Eastern Railway. Woollen

Woolen (American English) or woollen (Commonwealth English) is a type of yarn made from carded wool. Woolen yarn is soft, light, stretchy, and full of air. It is thus a good insulator, and makes a good knitting yarn. Woolen yarn is in contrast t ...

cloth was shipped undyed and undressed from 14th/15th century London to the nearby shores of the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, where it was considered indispensable.

During the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, London was the principal early centre of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

in England. Its close commercial connections with the Protestant heartlands in northern continental Europe, large foreign mercantile communities, disproportionately large number of literate inhabitants and role as the centre of the English print trade all contributed to the spread of the new ideas of religious reform. Before the Reformation, more than half of the area of London was the property of monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

, nunneries

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

and other religious houses.Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (1 ...

, ''London I: The Cities of London and Westminster'' rev. edition,1962, Introduction p 48.

Henry VIII's " Dissolution of the Monasteries" had a profound effect on the city as nearly all of this property changed hands. The process started in the mid-1530s, and by 1538 most of the larger monastic houses had been abolished. Holy Trinity Aldgate went to Lord Audley, and the Marquess of Winchester

Marquess of Winchester is a title in the Peerage of England that was created in 1551 for the prominent statesman William Paulet, 1st Earl of Wiltshire. It is the oldest of six surviving English marquessates; therefore its holder is considered ...

built himself a house in part of its precincts. The Charterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

Londo ...

went to Lord North, Blackfriars to Lord Cobham, the leper hospital of St Giles to Lord Dudley, while the king took for himself the leper hospital of St James, which was rebuilt as St James's Palace.

The period saw London rapidly rising in importance among Europe's commercial centres. Trade expanded beyond Western Europe to Russia, the Levant, and the Americas. This was the period of mercantilism and monopoly trading companies such as the Muscovy Company

The Muscovy Company (also called the Russia Company or the Muscovy Trading Company russian: Московская компания, Moskovskaya kompaniya) was an English trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major chartered joint s ...

(1555) and the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

(1600) were established in London by royal charter. The latter, which ultimately came to rule India, was one of the key institutions in London, and in Britain as a whole, for two and a half centuries. Immigrants arrived in London not just from all over England and Wales, but from abroad as well, for example Huguenots from France; the population rose from an estimated 50,000 in 1530 to about 225,000 in 1605. The growth of the population and wealth of London was fuelled by a vast expansion in the use of coastal shipping.

The late 16th and early 17th century saw the great flourishing of drama in London whose preeminent figure was William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

. During the mostly calm later years of Elizabeth's reign, some of her courtiers and some of the wealthier citizens of London built themselves country residences in Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

, Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and Grea ...

and Surrey. This was an early stirring of the villa movement, the taste for residences which were neither of the city nor on an agricultural estate, but at the time of Elizabeth's death in 1603, London was still relatively compact.

Xenophobia was rampant in London, and increased after the 1580s. Many immigrants became disillusioned by routine threats of violence and molestation, attempts at expulsion of foreigners, and the great difficulty in acquiring English citizenship. Dutch cities proved more hospitable, and many left London permanently. Foreigners are estimated to have made up 4,000 of the 100,000 residents of London by 1600, many being Dutch and German workers and traders.

Xenophobia was rampant in London, and increased after the 1580s. Many immigrants became disillusioned by routine threats of violence and molestation, attempts at expulsion of foreigners, and the great difficulty in acquiring English citizenship. Dutch cities proved more hospitable, and many left London permanently. Foreigners are estimated to have made up 4,000 of the 100,000 residents of London by 1600, many being Dutch and German workers and traders.

Stuart London (1603–1714)

London's expansion beyond the boundaries of the City was decisively established in the 17th century. In the opening years of that century the immediate environs of the City, with the principal exception of the aristocratic residences in the direction of Westminster, were still considered not conducive to health. Immediately to the north wasMoorfields

Moorfields was an open space, partly in the City of London, lying adjacent to – and outside – its northern wall, near the eponymous Moorgate. It was known for its marshy conditions, the result of the defensive wall acting like a dam, ...

, which had recently been drained and laid out in walks, but it was frequented by beggars and travellers, who crossed it in order to get into London. Adjoining Moorfields were Finsbury Fields, a favourite practising ground for the archers, Mile End

Mile End is a district of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London, England, east-northeast of Charing Cross. Situated on the London-to-Colchester road, it was one of the earliest suburbs of London. It became part of the m ...

, then a common on the Great Eastern Road and famous as a rendezvous for the troops.

The preparations for King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

becoming king were interrupted by a severe plague epidemic, which may have killed over thirty thousand people. The Lord Mayor's Show

The Lord Mayor's Show is one of the best-known annual events in London as well as one of the longest-established, dating back to the 13th century. A new lord mayor is appointed every year, and the public parade that takes place as his or her in ...

, which had been discontinued for some years, was revived by order of the king in 1609. The dissolved monastery of the Charterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

Londo ...

, which had been bought and sold by the courtiers several times, was purchased by Thomas Sutton

Thomas Sutton (1532 – 12 December 1611) was an English civil servant and businessman, born in Knaith, Lincolnshire. He is remembered as the founder of the London Charterhouse and of Charterhouse School.

Life

Sutton was the son of an official ...

for £13,000. The new hospital, chapel, and schoolhouse were begun in 1611. Charterhouse School was to be one of the principal public schools in London until it moved to Surrey in the Victorian era, and the site is still used as a medical school.

The general meeting-place of Londoners in the day-time was the nave of Old St. Paul's Cathedral. Merchants conducted business in the aisles, and used the font as a counter upon which to make their payments; lawyers received clients at their particular pillars; and the unemployed looked for work. St Paul's Churchyard was the centre of the book trade and Fleet Street was a centre of public entertainment. Under James I the theatre, which established itself so firmly in the latter years of Elizabeth, grew further in popularity. The performances at the public theatres were complemented by elaborate masques

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A masq ...

at the royal court and at the inns of court.

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

acceded to the throne in 1625. During his reign, aristocrats began to inhabit the West End in large numbers. In addition to those who had specific business at court, increasing numbers of country landowners and their families lived in London for part of the year simply for the social life. This was the beginning of the "London season". Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in develo ...

was built about 1629. The piazza of Covent Garden, designed by England's first classically trained architect Inigo Jones followed in about 1632. The neighbouring streets were built shortly afterwards, and the names of Henrietta, Charles, James, King and York Streets were given after members of the royal family.

In January 1642

In January 1642 five members

The Five Members were Members of Parliament whom King Charles I attempted to arrest on 4 January 1642. King Charles I entered the English House of Commons, accompanied by armed soldiers, during a sitting of the Long Parliament, although the Fi ...

of parliament whom the King wished to arrest were granted refuge in the City. In August of the same year the King raised his banner at Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

, and during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

London took the side of the parliament. Initially the king had the upper hand in military terms and in November he won the Battle of Brentford a few miles to the west of London. The City organised a new makeshift army and Charles hesitated and retreated.

Subsequently, an extensive system of fortifications was built to protect London from a renewed attack by the Royalists. This comprised a strong earthen rampart, enhanced with bastions and redoubts. It was well beyond the City walls and encompassed the whole urban area, including Westminster and Southwark. London was not seriously threatened by the royalists again, and the financial resources of the City made an important contribution to the parliamentarians' victory in the war.

The unsanitary and overcrowded City of London has suffered from the numerous outbreaks of the plague many times over the centuries, but in Britain it is the last major outbreak which is remembered as the "Great Plague

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

" It occurred in 1665 and 1666 and killed around 60,000 people, which was one fifth of the population. Samuel Pepys chronicled the epidemic in his diary. On 4 September 1665 he wrote "I have stayed in the city till above 7400 died in one week, and of them about 6000 of the plague, and little noise heard day or night but tolling of bells."

Great Fire of London (1666)

The Great Plague was immediately followed by another catastrophe, albeit one which helped to put an end to the plague. On the Sunday, 2 September 1666 the Great Fire of London broke out at one o'clock in the morning at a bakery inPudding Lane

Pudding Lane is a small street in London, widely known as the location of Thomas Farriner's bakery, where the Great Fire of London started in 1666. It runs between Eastcheap and Thames Street in the historic City of London, and intersects Monum ...

in the southern part of the City. Fanned by an eastern wind the fire spread, and efforts to arrest it by pulling down houses to make firebreaks were disorganised to begin with. On Tuesday night the wind fell somewhat, and on Wednesday the fire slackened. On Thursday it was extinguished, but on the evening of that day the flames again burst forth at the Temple. Some houses were at once blown up by gunpowder, and thus the fire was finally mastered. The Monument

The Monument to the Great Fire of London, more commonly known simply as the Monument, is a fluted Doric column in London, England, situated near the northern end of London Bridge. Commemorating the Great Fire of London, it stands at the j ...

was built to commemorate the fire: for over a century and a half it bore an inscription attributing the conflagration to a ''"popish frenzy"''.

John Evelyn

John Evelyn (31 October 162027 February 1706) was an English writer, landowner, gardener, courtier and minor government official, who is now best known as a diarist. He was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society.

John Evelyn's diary, or ...

and Robert Hooke.

Wren proposed to build main thoroughfares north and south, and east and west, to insulate all the churches in conspicuous positions, to form the most public places into large piazzas, to unite the halls of the 12 chief livery companies into one regular square annexed to the Guildhall

A guildhall, also known as a "guild hall" or "guild house", is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commonly become town halls and in som ...

, and to make a fine quay on the bank of the river from Blackfriars to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

. Wren wished to build the new streets straight and in three standard widths of thirty, sixty and ninety feet. Evelyn's plan differed from Wren's chiefly in proposing a street from the church of St Dunstan's in the East to the St Paul's, and in having no quay or terrace along the river. These plans were not implemented, and the rebuilt city generally followed the streetplan of the old one, and most of it has survived into the 21st century.

Whitehall Palace

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

until it was destroyed by fire in the 1690s, and thereafter St. James's Palace. The rural lane of Piccadilly sprouted courtiers mansions such as Burlington House. Thus the separation between the middle class mercantile City of London, and the aristocratic world of the court in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

became complete.

In the City itself there was a move from wooden buildings to stone and brick construction to reduce the risk of fire. Parliament's Rebuilding of London Act 1666

The The reconstruction of London is an Act of the Parliament of England (19 Car. II. c. 8) with the long title "An Act for rebuilding the City of London."'Charles II, 1666: An Act for rebuilding the City of London.', Statutes of the Realm: volume ...

stated ''"building with brick snot only more comely and durable, but also more safe against future perils of fire"''. From then on only doorcases, window-frames and shop fronts were allowed to be made of wood.

Christopher Wren's plan for a new model London came to nothing, but he was appointed to rebuild the ruined parish churches and to replace St Paul's Cathedral. His domed baroque cathedral was the primary symbol of London for at least a century and a half. As city surveyor, Robert Hooke oversaw the reconstruction of the City's houses. The East End, that is the area immediately to the east of the city walls, also became heavily populated in the decades after the Great Fire. London's docks began to extend downstream, attracting many working people who worked on the docks themselves and in the processing and distributive trades. These people lived in Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

, Wapping

Wapping () is a district in East London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Wapping's position, on the north bank of the River Thames, has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through its riverside public houses and steps, ...

, Stepney

Stepney is a district in the East End of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The district is no longer officially defined, and is usually used to refer to a relatively small area. However, for much of its history the place name appli ...

and Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through ...

, generally in slum conditions.

In the winter of 1683–1684, a frost fair

The River Thames frost fairshttps://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=599805001&objectId=3199037&partId=1 Erra Paters Prophesy or Frost Faire 1684/3 were held on th ...

was held on the Thames. The frost, which began about seven weeks before Christmas and continued for six weeks after, was the greatest on record. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without s ...

in 1685 led to a large migration of Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

to London. They established a silk industry at Spitalfields.

At this time the Bank of England was founded, and the British East India Company was expanding its influence. Lloyd's of London

Lloyd's of London, generally known simply as Lloyd's, is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company; rather, Lloyd's is a corporate body gove ...

also began to operate in the late 17th century. In 1700, London handled 80% of England's imports, 69% of its exports and 86% of its re-exports. Many of the goods were luxuries from the Americas and Asia such as silk, sugar, tea and tobacco. The last figure emphasises London's role as an entrepot: while it had many craftsmen in the 17th century, and would later acquire some large factories, its economic prominence was never based primarily on industry. Instead it was a great trading and redistribution centre. Goods were brought to London by England's increasingly dominant merchant navy, not only to satisfy domestic demand, but also for re-export throughout Europe and beyond.

William III, a Dutchman, cared little for London, the smoke of which gave him asthma, and after the first fire at Whitehall Palace (1691) he purchased Nottingham House and transformed it into Kensington Palace. Kensington was then an insignificant village, but the arrival of the court soon caused it to grow in importance. The palace was rarely favoured by future monarchs, but its construction was another step in the expansion of the bounds of London. During the same reign Greenwich Hospital, then well outside the boundary of London, but now comfortably inside it, was begun; it was the naval complement to the Chelsea Hospital

The Royal Hospital Chelsea is a retirement home and nursing home for some 300 veterans of the British Army. Founded as an almshouse, the ancient sense of the word "hospital", it is a site located on Royal Hospital Road in Chelsea, London, Che ...

for former soldiers, which had been founded in 1681. During the reign of Queen Anne an act was passed authorising the building of 50 new churches to serve the greatly increased population living outside the boundaries of the City of London.

18th century

The 18th century was a period of rapid growth for London, reflecting an increasing national population, the early stirrings of theIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, and London's role at the centre of the evolving British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

.

In 1707, an Act of Union was passed merging the Scottish and the English Parliaments, thus establishing the Kingdom of Great Britain. A year later, in 1708 Christopher Wren's masterpiece, St Paul's Cathedral was completed on his birthday. However, the first service had been held on 2nd of December 1697; more than 10 years earlier. This Cathedral replaced the original St. Paul's which had been completely destroyed in the Great Fire of London. This building is considered one of the finest in Britain and a fine example of Baroque architecture

Baroque architecture is a highly decorative and theatrical style which appeared in Italy in the early 17th century and gradually spread across Europe. It was originally introduced by the Catholic Church, particularly by the Jesuits, as a means t ...

.

Many tradesmen from different countries came to London to trade goods and merchandise. Also, more immigrants moved to London making the population greater. More people also moved to London for work and for business making London an altogether bigger and busier city. Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War increased the country's international standing and opened large new markets to British trade, further boosting London's prosperity.

During the Georgian period London spread beyond its traditional limits at an accelerating pace. This is shown in a series of detailed maps, particularly

Many tradesmen from different countries came to London to trade goods and merchandise. Also, more immigrants moved to London making the population greater. More people also moved to London for work and for business making London an altogether bigger and busier city. Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War increased the country's international standing and opened large new markets to British trade, further boosting London's prosperity.

During the Georgian period London spread beyond its traditional limits at an accelerating pace. This is shown in a series of detailed maps, particularly John Rocque

John Rocque (originally Jean; c. 1704–1762) was a French-born British surveyor and cartographer, best known for his detailed map of London published in 1746.

Life and career

Rocque was born in France in about 1704, one of four children of a ...

's 1741–45 map ''(see below)'' and his 1746 Map of London. New districts such as Mayfair were built for the rich in the West End, new bridges over the Thames encouraged an acceleration of development in South London and in the East End, the Port of London

The Port of London is that part of the River Thames in England lying between Teddington Lock and the defined boundary (since 1968, a line drawn from Foulness Point in Essex via Gunfleet Old Lighthouse to Warden Point in Kent) with the North Se ...

expanded downstream from the City. During this period was also the uprising of the American colonies.

In 1780, the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

held its only American prisoner, former President of the Continental Congress, Henry Laurens

Henry Laurens (December 8, 1792) was an American Founding Father, merchant, slave trader, and rice planter from South Carolina who became a political leader during the Revolutionary War. A delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Laure ...

. In 1779, he was the Congress's representative of Holland, and got the country's support for the Revolution. On his return voyage back to America, the Royal Navy captured him and charged him with treason after finding evidence of a reason of war between Great Britain and the Netherlands. He was released from the Tower on 21 December 1781 in exchange for General Lord Cornwallis