The History of French foreign relations covers French diplomacy and foreign relations down to 1980. For the more recent developments, see

Foreign relations of France

In the 19th century France built a new French colonial empire second only to the British Empire. It was humiliated in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, which marked the rise of Germany to dominance in Europe. France allied with Great Bri ...

.

Valois and Bourbon France 1453–1789

Franco-Ottoman alliance

The

Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman Alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish Alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between the King of France Francis I and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Suleiman I. The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance was o ...

was a military alliance established in 1536 between the king of

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

Francis I and the Sultan of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ ...

. The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance was one of the most important

foreign alliances of France

The foreign alliances of France have a long and complex history spanning more than a millennium. One traditional characteristic of the French diplomacy of alliances has been the ''"Alliance de revers"'' (i.e. "Rear alliance"), aiming at allying w ...

, and was particularly influential during the

Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

. It enabled France to fight the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

under Charles V and Philip II on equal terms. The Franco-Ottoman military alliance reached its peak

around 1553 during the reign

Henry II of France

Henry II (french: Henri II; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I and Duchess Claude of Brittany, he became Dauphin of France upon the death of his elder bro ...

. The alliance was exceptional, as the first alliance between a Christian and Muslim state, and caused a scandal in the Christian world, especially since France was heavily committed to support Catholicism.

Carl Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Burckhardt (September 10, 1891 – March 3, 1974) was a Swiss diplomat and historian. His career alternated between periods of academic historical research and diplomatic postings; the most prominent of the latter were League of Nati ...

called it "the

sacrilegious

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects (a ...

union of the

lily

''Lilium'' () is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants growing from bulbs, all with large prominent flowers. They are the true lilies. Lilies are a group of flowering plants which are important in culture and literature in much of the world. M ...

and the

crescent

A crescent shape (, ) is a symbol or emblem used to represent the lunar phase in the first quarter (the "sickle moon"), or by extension a symbol representing the Moon itself.

In Hinduism, Lord Shiva is often shown wearing a crescent moon on his ...

". It lasted intermittently for more than two and a half centuries,

[Merriman, p.132] until the

Napoleonic

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

invasion of

Ottoman Egypt, in 1798–1801.

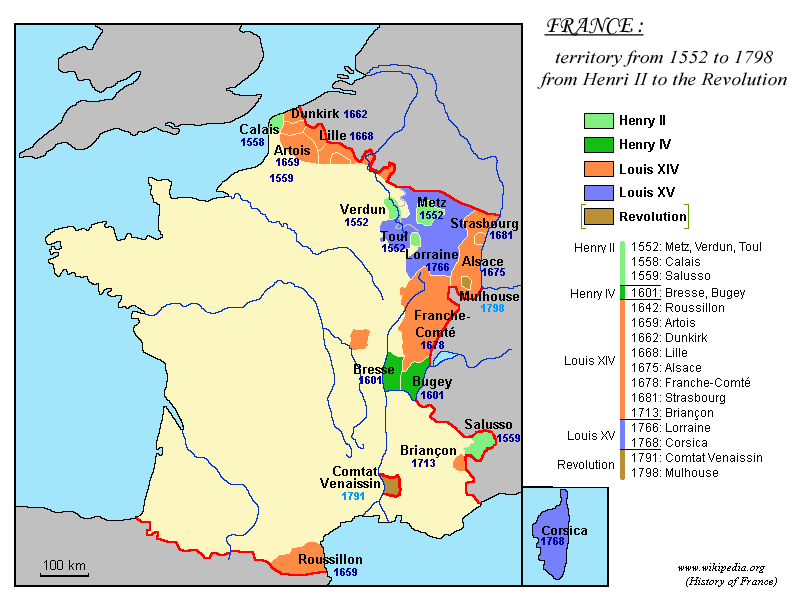

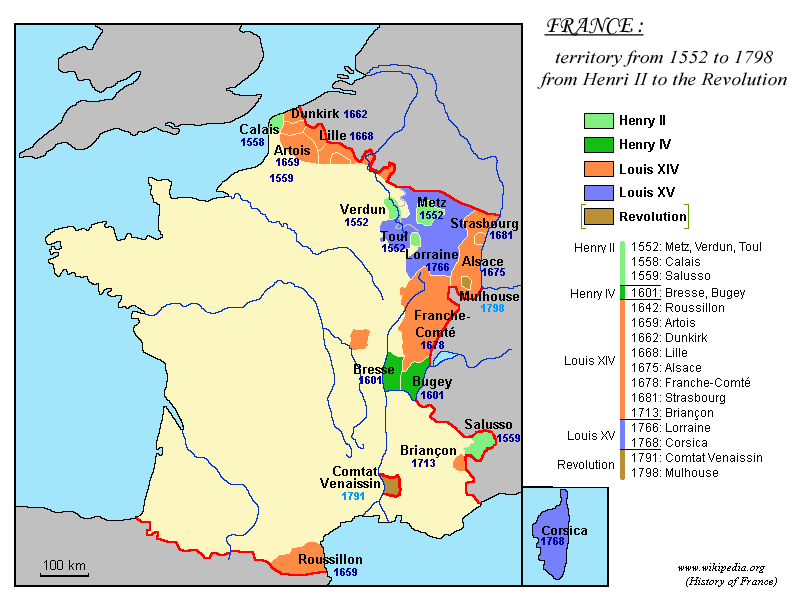

Louis XIV and Louis XV

Under the long reigns of kings

Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

(1643–1715) and

Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

(1715–1774), France was second in size to Russia but first in terms of economic and military power. It fought numerous expensive wars, usually to protect its voice in the selection of monarchs in neighboring countries. A high priority was blocking the growth of power of the Habsburg rivals who controlled Austria and Spain.

Warfare defined the foreign policies of Louis XIV, and his personality shaped his approach. Impelled "by a mix of commerce, revenge, and pique", Louis sensed that warfare was the ideal way to enhance his glory. In peacetime he concentrated on preparing for the next war. He taught his diplomats their job was to create tactical and strategic advantages for the French military.

Louis XIV had at his service many notable military commanders and an excellent support staff. His chief engineer

Vauban (1633–1707) perfected the arts of fortifying French towns and besieging enemy cities. The finance minister

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–83) dramatically improved the financial system so that it could support an army of 250,000 men. The system deteriorated under Louis XV so that wars drained the increasingly inefficient financial system. Louis XIV made France prouder in psychology but poorer in wealth; military glory and cultural splendor were exalted above economic growth.

Under Louis XIV, France fought three major wars: the

Franco-Dutch War, the

War of the League of Augsburg, and the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. There were also two lesser conflicts: the

War of Devolution

In the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution (, ), France occupied large parts of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté, both then provinces of the Holy Roman Empire (and properties of the King of Spain). The name derives from an obscure law know ...

and the

War of the Reunions

The War of the Reunions (1683–84) was a conflict between France, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, with limited involvement by Genoa. It can be seen as a continuation of the 1667–1668 War of Devolution and the 1672–1678 Franco–Dutch War ...

.

Louis XV did merge

Lorraine

Lorraine , also , , ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; german: Lothringen ; lb, Loutrengen; nl, Lotharingen is a cultural and historical region in Northeastern France, now located in the administrative region of Gra ...

and

Corsica into France. However France was badly defeated in the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

(1754–1763) and forced to give up its holdings in North America. It ceded

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

to Great Britain and Louisiana to Spain, and was left with a bitter grudge that sought revenge in 1778 by helping the Americans win independence. Louis XV's decisions damaged the power of France, weakened the treasury, discredited the absolute monarchy, and made it more vulnerable to distrust and destruction, as happened in the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, which broke out 15 years after his death. Norman Davies characterized Louis XV's reign as "one of debilitating stagnation", characterized by lost wars, endless clashes between the Court and Parliament, and religious feuds. A few scholars defend Louis, arguing that his highly negative reputation was based on propaganda meant to justify the French Revolution.

Jerome Blum

Lord and Peasant in Russia from the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century is a political-social-economic history of Russia written by historian Jerome Blum and published by Princeton University Press in 1961. The work covers the period from Varang ...

described him as "a perpetual adolescent called to do a man's job."

American Revolutionary War

France played a key role helping the American Patriots win

their War of Independence against Britain 1775–1783. Motivated by a long-term rivalry with Britain and by revenge for its territorial losses during Seven Years' War, France began secretly sending supplies in 1775. In 1777, American captured the British invasion army at Saratoga, demonstrating the viability of their revolt. In 1778, France recognized the United States of America as a sovereign nation, signed a military alliance and went to war with Britain. France built a coalitions with Netherlands and Spain, provided Americans with money and arms, sent a combat army to serve under

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, and sent a navy that prevented the second British army from escaping from Yorktown in 1781.

India was a major battlefield, in which France tried to form alliances with Indian states against the British -controlled

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

. Under

Warren Hastings, the British managed to hold their own throughout the war. When the war began Britain quickly seized all of France's Indian possessions, especially

Pondicherry

Pondicherry (), now known as Puducherry ( French: Pondichéry ʊdʊˈtʃɛɹi(listen), on-dicherry, is the capital and the most populous city of the Union Territory of Puducherry in India. The city is in the Puducherry district on the sout ...

. They were returned to France in the 1783 peace treaty.

By 1789, the French debt acquired to fight in that war came to a staggering 1.3 billion livres. It "set off France's own fiscal crisis, a political brawl over taxation that soon became one of the reasons for French Revolution." France did obtain its revenge against Britain, but materially it gained little and its huge debts seriously weakened the government and helped facilitate the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

in 1789.

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

served as the American ambassador to France from 1776 to 1785. He met with many leading diplomats, aristocrats, intellectuals, scientists and financiers. Franklin's image and writings caught the French imagination – there were many images of him sold on the market – and he became the

cultural icon

A cultural icon is a person or an artifact that is identified by members of a culture as representative of that culture. The process of identification is subjective, and "icons" are judged by the extent to which they can be seen as an authentic ...

of the archetypal new American, and even a hero for aspirations for a new order inside France.

French Revolution and Napoleon: 1789–1815

French Revolution

After the stated aim of the National Convention to

export revolution, the guillotining of Louis XVI of France, and the French opening of the Scheldt, a European military coalition was formed against France. Spain, Naples, Great Britain, and the Netherlands joined Austria and Prussia in

The First Coalition (1792–97), the first major concerted effort of multiple European powers to contain Revolutionary France. It took shape after the wars had already begun.

The Republican government in Paris was radicalised after a diplomatic coup from the Jacobins said it would be the

''Guerre Totale'' ("total war") and called for a ''

Levée en masse'' (mass conscription of troops). Royalist invasion forces were defeated at

Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

in 1793, leaving the French republican forces in an offensive position and granting nationwide fame to a young hero,

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

(1769–1821). Following their victory at

Fleurus

Fleurus (; wa, Fleuru) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It has been the site of four major battles.

The municipality consists of the following districts: Brye, Heppignies, Fleurus, Lambusart, ...

, the French occupied Belgium and the Rhineland. An invasion of the Netherlands established the puppet

Batavian Republic. Finally, a peace agreement was concluded between France, Spain, and Prussia in 1795 at

Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

.

Napoleonic wars

By 1799 Napoleon had seized power in France and proved highly adept at warfare and coalition building. Britain led a series of shifting coalitions to oppose him. After a brief truce in 1802–3, war resumed. In 1806 Prussia joined Britain and Russia, thus forming the

Fourth Coalition. Napoleon was not alone since he now had a complex network of allies and subject states. The largely outnumbered French army crushed the Prussian army at

Jena-Auerstedt in 1806; Napoleon captured Berlin and went as far as Eastern Prussia. There the Russian Empire was defeated at the

Battle of Friedland

The Battle of Friedland (14 June 1807) was a major engagement of the Napoleonic Wars between the armies of the French Empire commanded by Napoleon I and the armies of the Russian Empire led by Count von Bennigsen. Napoleon and the French obtai ...

(14 June 1807). Peace was dictated in the

Treaties of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when ...

, in which Russia had to join the

Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berli ...

, and Prussia handed half of its territories to France. The

Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

was formed over these territorial losses, and Polish troops entered the Grande Armée in significant numbers.

Napoleon then went back to the west, to deal with Britain. Only two countries remained neutral in the war: Sweden and Portugal, and Napoleon then looked toward the latter. In the

Treaty of Fontainebleau, a Franco-Spanish alliance against Portugal was sealed as Spain eyed Portuguese territories. French armies entered Spain in order to attack Portugal, but then seized Spanish fortresses and took over the kingdom by surprise.

Joseph Bonaparte

it, Giuseppe-Napoleone Buonaparte es, José Napoleón Bonaparte

, house = Bonaparte

, father = Carlo Buonaparte

, mother = Letizia Ramolino

, birth_date = 7 January 1768

, birth_place = Corte, Corsica, Republic of ...

, Napoleon's brother, was made King of Spain after

Charles IV abdicated. This occupation of the Iberian peninsula fueled local nationalism, and soon the Spanish and Portuguese fought the French using

guerrilla tactics, defeating the French forces at the

Battle of Bailén (June and July 1808). Britain sent a short-lived ground support force to Portugal, and French forces evacuated Portugal as defined in the

Convention of Sintra

The Convention of Cintra (or Sintra) was an agreement signed on 30 August 1808, during the Peninsular War. By the agreement, the defeated French were allowed to evacuate their troops from Portugal without further conflict. The Convention was sig ...

following the Allied victory at

Vimeiro (21 August 1808). France only controlled

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

and

Navarre and could have been definitely expelled from the Iberian peninsula had the Spanish armies attacked again, but the Spanish did not.

Another French attack was launched on Spain, led by Napoleon himself, and was described as "an avalanche of fire and steel." However, the French Empire was no longer regarded as invincible by European powers. In 1808 Austria formed the

Fifth Coalition

The War of the Fifth Coalition was a European conflict in 1809 that was part of the Napoleonic Wars and the Coalition Wars. The main conflict took place in central Europe between the Austrian Empire of Francis I and Napoleon's French Empir ...

in order to break down the French Empire. The Austrian Empire defeated the French at

Aspern-Essling, yet was beaten at

Wagram

Deutsch-Wagram (literally "German Wagram", ), often shortened to Wagram, is a village in the Gänserndorf District, in the state of Lower Austria, Austria. It is in the Marchfeld Basin, close to the Vienna city limits, about 15 km (9 mi) northeas ...

while the Polish allies defeated the Austrian Empire at

Raszyn (April 1809). Although not as decisive as the previous Austrian defeats, the

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

in October 1809 stripped Austria of a large amount of territories, reducing it even more.

In 1812 Napoleon could no longer tolerate Russian independence. He assembled a gigantic army and invaded. The

French invasion of Russia (1812)

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign, the Second Polish War, the Army of Twenty nations, and the Patriotic War of 1812 was launched by Napoleon Bonaparte to force the Russian Empire back into the continental block ...

Was a total disaster, caused primarily by weather, partisan attacks, disease and inadequate logistics. Only small remnants of the invading army returned from Russia. On the Spanish front the French armies were defeated and evacuated Spain.

Since France had been defeated on these two fronts, states it previously conquered and controlled struck back. The

Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor six ...

was formed, and the German states of the Confederation of the Rhine switched sides, finally opposing Napoleon. Napoleon was defeated in the

Battle of the Nations outside Leipzig in October 1813. The Allies invaded France and Napoleon abdicated on 6 April 1814. The

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

reversed the political changes that had occurred during the wars. Napoleon's attempted restoration, a period known as the

Hundred Days, ended with his final defeat at the

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

in 1815. The monarchy was restored with

Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

as king, followed by his brother. France was soon integrated into the reactionary international situation. However much of the Napoleonic liberalization of Western Europe, including Italy, and Germany, and adjacent areas became permanent.

France 1814–1850

France was no longer the dominant power it had been before 1814, but it played a major role in European economics, culture, diplomacy and military affairs. The Bourbons were restored, but left a weak record and one branch was overthrown in 1830 and the other branch in 1848 as Napoleon's nephew was elected president. He made himself emperor as

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

and lasted until he was defeated and captured by Prussians in 1870 a war that humiliated France and made the new nation of Germany dominant in the continent. France built up an empire, especially in Africa and Indochina. The economy was strong, with a good railway system. The arrival of the

Rothschild banking family of France in 1812 guaranteed the role of Paris alongside London as a major center of international finance.

Overseas empire in the nineteenth century

Starting with its scattered smallholdings in India, West Indies, and Latin America, France began rebuilding its world empire. It took control of Algeria in 1830 and started to send in settlers. It began in earnest to rebuild its worldwide empire after 1850, concentrating chiefly in North and West Africa, as well as South-East Asia, with other conquests in Central and East Africa, as well as the South Pacific. Republicans, at first hostile to the empire, only became supportive when Germany started to build its own colonial empire in the 1880s. As it developed the new French empire expanded trade with France, especially supplying raw materials and purchasing manufactured items. The empire bestowed prestige on the motherland and spread French civilization and language, as well as the Catholic religion. It also provided manpower in the World Wars.

Paris took on a moral mission to lift the world up to French standards by bringing Christianity and French culture. In 1884 the leading exponent of colonialism,

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

declared; "The higher races have a right over the lower races, they have a

duty to civilize the inferior races." Full citizenship rights – ''assimilation'' – was a long-term goal, but in practice, colonial officials were reluctant to extend full citizenship rights. France sent small numbers of white permanent settlers to its empire, in sharp contrast to Britain, Spain, and Portugal. The notable exception was Algeria, where the French settlers held power but remained a minority.

Second Empire: 1851–1871

Despite his promises in 1852 of a peaceful reign,

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

could not resist the temptations of glory in foreign affairs such as his uncle, the world-famous Napoleon, had achieved. He was visionary, mysterious and secretive; he had a poor staff, and kept running afoul of his domestic supporters. In the end he was incompetent as a diplomat. Napoleon did have some successes: he strengthened French control over Algeria, established bases in Africa, began the takeover of Indochina, and opened trade with China. He facilitated a French company building the Suez Canal, which Britain could not stop.

In Europe, however, Napoleon failed again and again. The

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

of 1854–1856 against Russia, in alliance with Britain and the Ottoman Empire, produced heavy losses and high expenses but no territorial or political gains. War with Austria in 1859 facilitated the unification of Italy, and Napoleon was rewarded with the annexation of Savoy and Nice. The British grew annoyed at his intervention in Syria in 1860–61. He angered Catholics alarmed at his poor treatment of the Pope, then reversed himself and angered the anticlerical liberals at home and his erstwhile Italian allies. He lowered the tariffs, which helped in the long run but in the short run angered owners of large estates and the textile and iron industrialists, while leading worried workers to organize.

Finally Napoleon was outmaneuvered by

Otto von Bismarck and went to war with the Germans in 1870 when it was too late to stop German unification. Napoleon had alienated everyone; after failing to obtain an alliance with Austria and Italy, France had no allies and was bitterly divided at home. It was disastrously defeated on the battlefield, losing Alsace and Lorraine. A. J. P. Taylor is blunt: "he ruined France as a great power."

American Civil War and Mexico

France remained officially neutral throughout the War and never recognized the Confederate States of America. However, there were advantages to helping the Confederacy. France's textile factories needed cotton, and Napoleon III had imperial ambitions in Mexico which could be greatly aided by the Confederacy. The United States had warned that recognition of the Confederacy meant war. France was reluctant to act alone without British collaboration, and the British rejected intervention. Emperor Napoleon III realized that a war with the U.S. without allies "would spell disaster" for France. Napoleon III and his Minister of Foreign Affairs Edouard Thouvenel adopted a cautious attitude and maintained diplomatically correct relations with Washington. Half the French press favored the Union, while the "imperial" press was more sympathetic to the Confederacy. Public opinion generally ignored the war, but did show interest in controlling Mexico.

Napoleon hoped that a Confederate victory would result in two weak nations on Mexico's northern borders, allowing French dominance in a country ruled by its puppet Emperor Maximilian.

Matías Romero, Júarez's ambassador to the United States, gained some support in Congress for possibly intervening on Mexico's behalf against France's occupation. However, Lincoln's Secretary of State

William Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

was cautious in limiting US aid to Mexico. He did not want a war with France before the Confederacy was defeated.

Napoleon nearly blundered into war with the United States in 1862.

His plan to take control of Mexico in 1861–1867 was a total disaster. The United States forced him to evacuate his army from Mexico, and his puppet Emperor was executed. In 1861, Mexican conservatives looked to Napoleon III to abolish the Republic led by liberal President

Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

. France favored the Confederacy but did not accord it diplomatic recognition. The French expected that a Confederate victory would facilitate French economic dominance in Mexico. He helped the Confederacy by shipping urgently needed supplies through the ports of Matamoros, Mexico, and Brownsville (Texas). The Confederacy itself sought closer relationships with Mexico. Juarez turned it down, but the Confederates worked well with local warlords in northern Mexico, and with the French invaders.

Realizing that Washington could not intervene in Mexico as long as the Confederacy controlled Texas, France invaded Mexico in 1861 and installed an Austrian prince

Maximilian I of Mexico as its puppet ruler in 1864. Owing to the shared convictions of the democratically elected government of Juárez and Lincoln,

Matías Romero, Juárez's minister to Washington, mobilized support in the U.S. Congress, and raised money, soldiers and ammunition in the United States for the war against Maximilian. Washington repeatedly protested France's violation of the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

.

Once the Union won the War in spring 1865, Washington allowed supporters of Juárez to openly purchase weapons and ammunition and issued stronger warnings to Paris. Washington sent General

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

with 50,000 combat veterans to the Mexican border to emphasize that time had run out on the French intervention. Napoleon III had no choice but to withdrew his outnumbered army in disgrace. Emperor Maximilian refused exile and was executed by the Mexican government in 1867.

Historians typically interpret the fiasco as a disaster for France. They portray an imperialistic attempt to secure access to raw materials and markets, and to establish a Latin, Catholic client state to prevent further American into Latin America. The failure stemmed from lack of realism in its conception, a gross misunderestimate of the power of the United States, a misunderstanding of Mexican public opinion, and recurring ineptitude in execution. While Maximilian and his widow get popular sympathy, Napoleon earns the sharp negative criticism of historians.

Third Republic: 1871–1914

French foreign policy was based on a hatred of Germany—whose larger size and faster-growing economy could not be matched—combined with a popular revanchism that demanded the return of Alsace and Lorraine. There were some moderate leaders who wanted to forget the past, but Berlin ignored their overtures.

According to M.B. Hayne, the French foreign office, known widely from its street address as Quai d'Orsay, wad run by a highly professional diplomatic core group who controlled France's foreign policy in the two decades before 1914. Their decisive power resulted from clever exploitation of the preoccupation of the cabinet and parliament with internal politics; the rapid turnover of senior ministers, usually with minimal foreign-policy experience; and the growing expertise and self-assuredness of the bureaucrats. Hayne points out that they often defied official policies, withheld information from politicians they disdain, and used an outside network of influence from bankers, journalists, and French industry to promote their independent foreign policy.

Foreign affairs attracted far less attention than domestic affairs. Religious and class differences deeply divided the French people on polarities such as monarchy versus Republicanism, secularism versus Catholicism, farmers versus urbanites, workers versus owners. Permanent professional diplomats and bureaucrats had developed their own traditions of how to operate at the

Quai d'Orsay

The Quai d'Orsay ( , ) is a quay in the 7th arrondissement of Paris. It is part of the left bank of the Seine opposite the Place de la Concorde. The Quai becomes the Quai Anatole-France east of the Palais Bourbon, and the Quai Branly west of t ...

(where the Foreign Ministry was located), and their style changed little from generation to generation. Most of the diplomats came from high status or aristocratic families. Although France was one of the few republics in Europe, its diplomats mingled smoothly with the aristocratic representatives at the royal courts. Prime ministers and leading politicians generally paid little attention to foreign affairs, allowing a handful of senior men to control policy. In the decades before the First World War they dominated the embassies in the 10 major countries where France had an ambassador (elsewhere, they set lower-ranking ministers). They included

Théophile Delcassé, the foreign minister from 1898 to 1906;

Paul Cambon, the ambassador in London, 1890–1920;

Jean Jules Jusserand

Jean Adrien Antoine Jules Jusserand (18 February 1855 – 18 July 1932) was a French author and diplomat. He was the French Ambassador to the United States 1903-1925 and played a major diplomatic role during World War I.

Birth and education

...

in Washington from 1902 to 1924; and Camille Barrere, in Rome from 1897 to 1924. In terms of foreign policy, there was general agreement about the need for high protective tariffs, which kept agricultural prices high. After the defeat by the Germans, there was a strong widespread anti-German sentiment focused on revanchism and regaining Alsace and Lorraine. The Empire was a matter of great pride, and service as administrators, soldiers and missionaries was a high status occupation.

Besides a demand for revenge against Germany, imperialism was a factor. In the midst of the

Scramble for Africa, French and British interest in Africa came into conflict. The most dangerous episode was the

Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis (French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French exped ...

of 1898 when French troops tried to claim an area in the Southern Sudan, and a British force purporting to be acting in the interests of the

Khedive of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brou ...

arrived. Under heavy pressure the French withdrew securing Anglo-Egyptian control over the area. The status quo was recognised by an agreement between the two states acknowledging British control over Egypt, while France became the dominant power in Morocco, but France suffered a humiliating defeat overall.

Colonial empire in Africa and Asia

The

Suez Canal, initially built by the French, became a joint British-French project in 1875, as both saw it as vital to maintaining their influence and empires in Asia. In 1882, ongoing civil disturbances in Egypt prompted Britain to intervene, extending a hand to France. The government allowed Britain to take effective control of Egypt.

Under the leadership of expansionist

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

, the Third Republic greatly expanded the

French colonial empire. Catholic missionaries played a major role. France acquired

Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

,

Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, vast territories in

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

and

Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

, and much of

Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

.

In the early 1880s,

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza

Pietro Paolo Savorgnan di Brazzà, later known as Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de Brazza; 26 January 1852 – 14 September 1905), was an Italian-born, naturalized French explorer. With his family's financial help, he explored the Ogoou ...

was exploring the

Kongo Kingdom

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

for France, at the same time

Henry Morton Stanley explored it in on behalf of

Leopold II of Belgium

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

, who would have it as his personal

Congo Free State (see section below). France occupied

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

in May 1881. In 1884, France occupied Guinea.

French West Africa (AOF) was founded in 1895, and

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa (french: link=no, Afrique-Équatoriale française), or the AEF, was the federation of French colonial possessions in Equatorial Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River into the Sahel, and comprising what are ...

in 1910.

During the

Scramble for Africa in the 1870s and 1880s, the British and French generally recognised each other's spheres of influence. The

Suez Canal, initially built by the French, became a joint British-French project in 1875, as both saw it as vital to maintaining their influence and empires in Asia. In 1882, ongoing civil disturbances in Egypt (''see

Urabi Revolt'') prompted Britain to intervene, extending a hand to France. France's expansionist Prime Minister

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

was out of office, and the government was unwilling to send more than an intimidatory fleet to the region. Britain established a protectorate, as France had a year earlier in

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, and popular opinion in France later put this action down to duplicity. It was about this time that the two nations established co-ownership of

Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

. The

Anglo-French Convention of 1882 was also signed to resolve territory disagreements in western Africa.

Fashoda crisis of 1898

In the 1875–1898 era, serious tensions with Britain erupted over African issues. At several points war was possible, but it never happened. One brief but dangerous dispute occurred during the

Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis (French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French exped ...

of 1898 when French troops tried to claim an area in the Southern Sudan, and a more powerful British military force purporting to be acting in the interests of the

Khedive of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brou ...

arrived. Under heavy pressure the French withdrew, thereby permitting Anglo-Egyptian control over the area south of Egypt. The status quo was recognised by an agreement acknowledging British control over Egypt, while France became the dominant power in

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

. France had failed in its main goals. P.M.H. Bell says, "Between the two governments there was a brief battle of wills, with the British insisting on immediate and unconditional French withdrawal from Fashoda. The French had to accept these terms, amounting to a public humiliation....Fashoda was long remembered in France as an example of British brutality and injustice."

Asia

France had colonies in Asia and looked for alliances and found in Japan a possible ally. At Japan's request Paris sent military missions in

1872–1880, in

1884–1889 and in

1918–1919 to help modernize the Japanese army. Conflicts with China over Indochina climaxed during the

Sino-French War (1884–1885).

Admiral Courbet

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

destroyed the Chinese fleet anchored at

Foochow

Fuzhou (; , Fuzhounese: Hokchew, ''Hók-ciŭ''), alternately romanized as Foochow, is the capital and one of the largest cities in Fujian province, China. Along with the many counties of Ningde, those of Fuzhou are considered to constitute t ...

. The treaty ending the war, put France in a protectorate over northern and central Vietnam, which it divided into

Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain '' Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, includ ...

and

Annam.

[Frederic Wakeman, Jr., ''The Fall of Imperial China'' (1975) pp. 189–191.]

Franco-Russian Alliance

France was deeply split between the monarchists on one side, and the Republicans on the other. The monarchists were comfortable with the tsar, but the Republicans deeply distrusted Russia. It was poor and not industrialized; it was intensely religious and authoritarian, with no sense of democracy or freedom for its peoples. It oppressed Poland. It exiled, and even executed political liberals and radicals. At a time when French Republicans were rallying in the

Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

against anti-Semitism in France, Russia was the most notorious center in the world of anti-Semitic outrages. On the other hand, Republicans and monarchists alike were increasingly frustrated by Bismarck's success in isolating France diplomatically. Paris made a few overtures to Berlin, but they were rebuffed, and after 1900 there was a threat of war between France and Germany over Germany's attempt to deny French expansion into Morocco. Great Britain was still in its "splendid isolation" mode and after a major agreement in 1890 with Germany, it seemed especially favorable toward Berlin. Colonial conflicts in Africa were troubling. The Fashoda crisis of 1898 brought Britain and France almost to the brink of war and ended with a humiliation of France that left it hostile to Britain. By 1892 Russia was the only opportunity for France to break out of its diplomatic isolation. Russia had been allied with Germany the new Kaiser Wilhelm removed Bismarck in 1890 and disrupted the established system. Thus in 1892 ended the "Reinsurance treaty" with Russia. Russia was now alone diplomatically and like France, it needed a military alliance to contain the threat of Germany's strong army and military aggressiveness. The pope, angered by German anti-Catholicism, worked diplomatically to bring Paris and St. Petersburg together. Russia desperately needed money for our infrastructure of railways and ports facilities. The German government refused to allow its banks to lend money to Russia, but French banks eagerly did so. For example, it funded the essential trans-Siberian railway. Negotiations were increasingly successful, and by 1895. France and Russia had signed the

Franco-Russian Alliance

The Franco-Russian Alliance (french: Alliance Franco-Russe, russian: Франко-Русский Альянс, translit=Franko-Russkiy Al'yans), or Russo-French Rapprochement (''Rapprochement Russo-Français'', Русско-Французско� ...

, a strong military alliance to join together in war if Germany attacked either of them. France had finally escaped its diplomatic isolation.

1900–1914

After Bismarck's removal from office in 1890, French efforts to isolate Germany finally succeeded. With the formation of the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

, Germany began to feel encircled. French foreign minister

Théophile Delcassé, especially, went to great pains to woo Russia and Great Britain. Key markers were the

Franco-Russian Alliance

The Franco-Russian Alliance (french: Alliance Franco-Russe, russian: Франко-Русский Альянс, translit=Franko-Russkiy Al'yans), or Russo-French Rapprochement (''Rapprochement Russo-Français'', Русско-Французско� ...

of 1894, the 1904

Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

with Great Britain, and finally the

Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907 which became the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

. This formal alliance with Russia, and informal alignment with Britain, against Germany and Austria eventually led Russia and Britain to enter World War I as France's main allies.

By 1914 French foreign policy was thus based on its formal alliance with Russia, and an informal understanding with Britain, all based on the assumption that the main threat was from Germany. The crisis of 1914 was unexpected, and when Germany mobilized its forces in response to Russian mobilization, France also had to mobilize or be overwhelmed by sheer numbers. Germany then invaded Belgium and France, and World War I had begun.

First World War

Germany declared war on France on 3 August 1914 and invaded Belgium and northeastern France following its

Schlieffen Plan

The Schlieffen Plan (german: Schlieffen-Plan, ) is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on ...

. The plan seemed to promise quick victory but it failed because of inadequate forces, unexpected Belgian resistance, and poor coordination among German generals. France had already launched its invasion of Germany with

Plan XVII, but very quickly realized it needed to defend Paris at all costs. It did so at the

First Battle of the Marne

The First Battle of the Marne was a battle of the First World War fought from 5 to 12 September 1914. It was fought in a collection of skirmishes around the Marne River Valley. It resulted in an Entente victory against the German armies in the ...

; the German armies were defeated and forced back. The war became stalemated on the

Western Front, with practically no movement until spring 1918. Both sides suffered very high casualties caused by repeated infantry attacks against defensive positions protected by trenches, barbed wire, machine guns, and heavy artillery using aircraft as spotters, and poison gas. Meanwhile, the rich industrial and mining regions of Belgium and northeastern France remained in German hands throughout the war. Marshals

Joseph Joffre

Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre (12 January 1852 – 3 January 1931) was a French general who served as Commander-in-Chief of French forces on the Western Front from the start of World War I until the end of 1916. He is best known for regroupi ...

(1852–1931) and

Douglas Haig

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, (; 19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928) was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War, he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until ...

(1861–1928) believed that attrition would win the war by wearing down the German reserves in multiple massive assaults. German general

Erich von Falkenhayn

General Erich Georg Sebastian Anton von Falkenhayn (11 September 1861 – 8 April 1922) was the second Chief of the German General Staff of the First World War from September 1914 until 29 August 1916. He was removed on 29 August 1916 after t ...

(1861–1922) was outnumbered and focused on defense. Both sides failed to realize the stultifying effect of trench warfare on morale and the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives in futile attempts to win a "decisive battle."

After Socialist leader

Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

. a pacifist, was assassinated at the start of the war, the French socialist movement abandoned its antimilitarist positions and joined the national war effort. The labor unions supported the war. Prime Minister

Rene Viviani called for unity—for a "

Union sacrée The Sacred Union (french: Union Sacrée, ) was a political truce in France in which the left-wing agreed, during World War I, not to oppose the government or call any strikes. Made in the name of patriotism, it stood in opposition to the pledge mad ...

" ("Sacred Union")--Which was a wartime truce between the right and left factions that had been fighting bitterly. France had few dissenters. However,

war-weariness

War-weariness is the public or political disapproval for the continuation of a prolonged conflict or war. The causes normally involve the intensity of casualties—financial, civilian, and military. It also occurs when a belligerent has the abil ...

was a major factor by 1917, even reaching the army.

The French Right supported the war, emphasizing the deep spiritual value of "the Union Sacrée." The middle-of-the-road Radicals split—one wing wanted a compromise peace. By winter 1916–17 strong annexationist demands emerged on the right, calling for annexation of Germany's Saar basin to France and the creation of independent German states on the left bank of the Rhine.

In 1914 London and Paris agreed that financially Britain would support the weaker Allies and that France would take care of itself. There was no common financial policy. French credit collapsed in 1916 and Britain took full control of the failing Allied finances and began loaning large sums to Paris. The J. P. Morgan bank in New York assumed control of French loans in the fall of 1916 and relinquished it to the US government when the U,S, entered the war in 1917.

In 1917 the Russian Revolution ended the Franco-Russian alliance, and French policy changed. It joined Britain sending forces against the Bolsheviks and in support of the "white" counter-revolutionaries. Paris gave active support to the Southern Slav unionist movement and to the Czech and Polish claims for independence. Serbia was a loyal ally of France throughout World War I. Serbia was highly appreciative of French financial and material aid before its collapse in 1915 as well as funding the Serbian government in exile. There was popular support in France for Serbia as seen in taking in refugees and educating students. France took part in the armed liberation of Serbia, Montenegro, and Vojvodina in 1918.

Paris Peace conference 1919

France suffered very heavy losses in the war, in terms of battle casualties and economic distress, but came out on the winning side. It demanded Germany make good all its financial losses (including pensions for the veterans.) At the Paris peace conference of 1919, vengeance against defeated Germany was the main French theme, and Prime Minister Clemenceau was largely effective against the moderating influences of the British and Americans. The

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

was forced upon Germany which deeply resented the harsh terms. France strongly supported the new Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. It became

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

and in the 1920s and 1930s helped France by opposing German ambitions in the Balkans.

Interwar years

French foreign and security policy after 1919 used traditional alliance strategies to weaken German's potential to threaten France and comply with the strict obligations devised by France in the Treaty of Versailles. The main diplomatic strategy came in response to the demands of the French army to form alliances against the German threat. Germany resisted then finally complied, aided by American money, and France took a more conciliatory policy by 1924 in response to pressure from Britain and the United States, as well as to French realization that its potential allies in Eastern Europe were weak and hard to coordinate. It proved impossible to establish military alliances with the United States or Britain. A tentative Russian agreement in 1935 was politically suspect and was not implemented. The alliances with Poland and Czechoslovakia; these proved to be weak ties that collapsed in the face of German threats in 1938 in 1939.

1920s

France was part of the Allied force that

occupied the Rhineland following the Armistice. Foch supported Poland in the

Greater Poland Uprising and in the

Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

and France also joined Spain during the

Rif War

The Rif War () was an armed conflict fought from 1921 to 1926 between Spain (joined by France in 1924) and the Berber tribes of the mountainous Rif region of northern Morocco.

Led by Abd el-Krim, the Riffians at first inflicted several de ...

. From 1925 until his death in 1932,

Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

, as prime minister during five short intervals, directed French foreign policy, using his diplomatic skills and sense of timing to forge friendly relations with

Weimar Germany

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

as the basis of a genuine peace within the framework of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. He realized France could neither contain the much larger Germany by itself nor secure effective support from Britain or the League.

In January 1923 as a response to the failure of Germany to ship enough coal as part of its reparations, France (and Belgium) occupied the industrial region of the

Ruhr. Germany responded with passive resistance, including Printing vast amounts of marks To pay for the occupation, thereby causing runaway inflation. Inflation heavily damaged the German middle class (Whose bank accounts became worthless) but it also damaged the French franc. France fomented a separatist movement pointing to an independent buffer state, but it collapsed after some bloodshed. The intervention was a failure, and in summer 1924 France accepted the American solution to the reparations issues, as expressed in the

Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

. According to the Dawes Plan, American banks made long-term loans to Germany which used the dollars to pay reparations. The United States demanded repayment of the war loans, although the terms were slightly softened in 1926. All the loans, payments and reparations were suspended in 1931, and all were finally resolved in 1951.

The

Locarno Treaties of 1925 helped bring Germany back into the French good graces. It guaranteed the border between France and Germany, but ignored Germany's controversial eastern border. In Poland, the public humiliation received by Polish diplomats was one of the contributing factors to the fall of the Grabski cabinet. Locarno contributed to the worsening of the atmosphere between Poland and France, weakening the

French-Polish alliance.

Józef Beck

Józef Beck (; 4 October 1894 – 5 June 1944) was a Polish statesman who served the Second Republic of Poland as a diplomat and military officer. A close associate of Józef Piłsudski, Beck is most famous for being Polish foreign minister in ...

ridiculed the treaties saying, "Germany was officially asked to attack the east, in return for peace in the west."

In the 1920s, France built the

Maginot Line, an elaborate system of static border defences, designed to fight off any German attack. The Maginot Line did not extend into Belgium, where Germany attacked in 1940 and went around the French defenses. Military alliances were signed with weak powers in 1920–21, called the "

Little Entente".

1930s

British historian

Richard Overy explains how the country that had dominated Europe for three centuries wanted one last extension of power, but failed in its resolve:

:In the 1930s France became a deeply conservative, defensive society, split by social conflict, undermined by failing and un-modernized economy and an empire in crisis. All these things explain the loss of will and direction in the 1930s.

The foreign policy of right-wing

Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occ ...

(prime minister and foreign minister 1934–1936) was based on a deep distrust of Nazi Germany. He sought anti-German alliances. He and Mussolini signed the

Franco-Italian Agreement

The Franco-Italian Agreements (often called ''Mussolini-Laval Accord'') were signed in Rome by both French Foreign Minister Pierre Laval and Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini on 7 January 1935.

History

After its victory in World War I, it ...

in January 1935. The agreement ceded parts of

French Somaliland to Italy and allowed her a free hand in Abyssinia, in exchange for support against any German aggression. In April 1935, Laval persuaded Italy and Great Britain to join France in the

Stresa Front against German ambitions in Austria. On 2 May 1935, he likewise signed the

Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance

The Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance was a bilateral treaty between France and the Soviet Union with the aim of enveloping Nazi Germany in 1935 to reduce the threat from Central Europe. It was pursued by Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet forei ...

, but it was not implemented by Laval nor by his left-wing successors.

Appeasement was increasingly adopted as Germany grew stronger, for France was increasingly weakened by a stagnant economy, unrest in its colonies, and bitter internal political fighting. Appeasement was the fall-back position when it was impossible to make a major decision. Martin Thomas says it was not a coherent diplomatic strategy nor a copying of the British. When Hitler in 1936 sent troops into the Rhineland—the part of Germany where no troops were allowed—neither Paris nor London would risk war, and nothing was done. France also appeased Italy on the Ethiopia question because it could not afford to risk an alliance between Italy and Germany.

Hitler's remilitarization of the Rhineland changed the balance of power decisively in favor of the ''Reich''. French credibility in standing against German expansion or aggression was left in doubt. French military strategy was entirely defensive, and it had no intention whatever of invading Germany if war broke out. Instead it planned to defend the

Maginot Line. Its failure to send even a single unit into Rhineland signaled that strategy to all of Europe. Potential allies in Eastern Europe could no longer trust in an alliance with a France that could not be trusted to deter Germany through threat of an invasion. without such deterrence, the ally was militarily helpless. Belgium dropped its defensive alliance with France and relied on neutrality. Paris neglected to expand the Maginot line to cover the Belgian border, which is where Germany invaded in 1940. Mussolini had previously pushed back against German expansion, now he realized cooperation with France was unpromising, so he began instead to swing in favor of Berlin. All of France's friends were disappointed – even the Pope told the French ambassador that, "Had you ordered the immediate advance of 200,000 men into the zone the Germans had occupied, you would have done everyone a very great favor."

Appeasement in union with Britain now became the main policy after 1936, as France sought peace in the face of Hitler's escalating demands.

Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier (; 18 June 1884 – 10 October 1970) was a French Radical-Socialist (centre-left) politician, and the Prime Minister of France who signed the Munich Agreement before the outbreak of World War II.

Daladier was born in Carpe ...

. prime minister 1938–40, refused to go to war against Germany and Italy without British support. He endorsed

Neville Chamberlain who wanted to save peace using the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

in 1938. France's military alliance with Czechoslovakia was sacrificed at Hitler's demand when France and Britain agreed to his terms at

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

in 1938.

The left-wing

Léon Blum government in 1936–37 joined the right-wing Britain government in establishing an arms embargo during the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

(1936–39). Blum rejected support for the Spanish Republicans because of his fear that civil war might spread to deeply divided France. As the Republican cause faltered in Spain, Blum secretly supplied the Republican cause with warplanes money and sanctuaries. The government nationalized arms suppliers, and dramatically increased its program of rearming the French military in a last-minute catch up with the Germans. It also tried to build up the weak Polish army.

French foreign policy in the 1920s and 1930s aimed to build military alliances with small nations in Eastern Europe in order to counter the threat of German attacks. Paris saw Romania as an ideal partner in this venture, especially in 1926 to 1939. During World War II the alliance failed. Romania was first neutral and then after Germany defeated France in 1940 it aligned with Germany. The main device France had used was arms sales in order to strengthen Romania and ensure its goodwill. French military promises were vague and not trusted after the sellout of Czechoslovakia at Munich in 1938, By 1938 French needed all the arms it could produce. Meanwhile, Germany was better poised to build strong economic ties. In 1938-39 France made a final effort to guarantee Romanian borders because it calculated that Germany needed Romanian oil, but Romania decided war with Germany would be hopeless and so it veered toward Berlin.

Second World War

Entry into war

In 1938 Germany demanded control of the German-speaking

Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. That small country had a defense alliance with France but militarily its position was hopeless. The Munich conference of September 29–30, 1938, was a summit meeting of leaders from Germany, Italy Britain and France. The Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia were not invited. The British and French wanted peace—or at least enough delay to allow them to try to catch up to German military superiority. Britain did not control French actions, but London had more influence on Paris than vice versa. The leading French voice for cooperating with British Prime Chamberlain in appeasement was foreign minister

Georges Bonnet. He was a "munichois"—that is, a defeatist and pacifist who sensed that France would lose to Germany in a war. He wanted to abandon the alliances with Poland and Russia and allow Germany a free hand in the east so it would ignore France. After a short conference Hitler got his way—the agreement allowed Germany to peacefully absorb the Sudetenland. In March, 1939, Germany took over Bohemia and Moravia, and turned Slovakia into a puppet state. The British and French finally realized that appeasement did not produce peace.

In spring 1939 Hitler demanded concessions from Poland and this time Britain and France announced they would go to war to defend the integrity of Poland. Efforts to bring the USSR into the coalition failed and instead it formed an agreement with Hitler to divide up Poland and Eastern Europe. Hitler did not believe the Allies would fight in such a faraway hopeless cause, and he invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Britain and France declared war on September 3, 1939. But there was little they could or did do to help Poland.

German conquest 1940

France and Britain together declared war against Germany two days after it invaded Poland. The British and French empires joined the war but no one else. Britain and France took a defensive posture, fearing German air attacks on cities. France hoped the

Maginot Line would protect it from an invasion. There was little fighting between the fall of Poland in mid-September and the following spring; it was the

Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

in Britain or ''Drôle de guerre'' – "the funny sort of war" – in France. Britain tried several peace feelers, but Hitler did not respond.

In spring 1940 Germany launched its

Blitzkrieg against Denmark and Norway, easily pushing the British out. Then it invaded the Low Countries and tricked Britain and France into sending their best combat units deep into the Netherlands, where they became trapped in the

Battle of France in May 1940. The Royal Navy rescued over 300,000 British and French soldiers from Dunkirk, but left behind all the equipment.

Paris fell to the Germans on 14 June 1940, and the government surrendered on 24 June 1940. Nazi Germany occupied three-fifths of France's territory, leaving the rest in the southeast to the new Vichy government, which was a bit more than a puppet state since it still had a navy. However nearly 2 million French soldiers became prisoners of war in Germany. They served as hostages and forced laborers in German factories. The United States suddenly realized Germany was on the verge of controlling practically all of Europe, and it determined to rapidly build up its small Army and Air Force, and expand its Navy. Sympathy with Britain was high, and many were willing to send munitions, but few Americans called for war.

Vichy France

The fall of France in June 1940 brought a new regime known as

Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its te ...

. Theoretically it was neutral, but in practice it was partly controlled by Germany until November 1942, when Germany took full control. Vichy was intensely conservative and anti-Communist, but it was practically helpless with Germany controlling half of France directly and holding nearly two million French POWs as hostages. Vichy finally collapsed when the Germans fled in summer 1944.

The United States granted Vichy full diplomatic recognition, sending Admiral

William D. Leahy to Paris as American ambassador. President Roosevelt hoped to use American influence to encourage those elements in the Vichy government opposed to military collaboration with Germany. Vichy still controlled its overseas colonies and Washington encouraged Vichy to resist German demands such as for air bases in Syria or to move war supplies through French North Africa. The essential American position was that France should take no action not explicitly required by the armistice terms that could adversely affect Allied efforts in the war. When Germany took full control the U.S. and Canada cut their ties.

French fleet

Britain feared that the French naval fleet could end up in German hands and be used against its own naval forces, which were so vital to maintaining north Atlantic shipping and communications. Under the armistice, France had been allowed to retain the

French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

, the ''Marine Nationale'', under strict conditions. Vichy pledged that the fleet would never fall into the hands of Germany, but refused to send the fleet beyond Germany's reach by sending it to Britain or to far away territories of the French empire such as the West Indies. Shortly after France gave up it attacked a large French naval contingent in

Mers-el-Kebir, killing 1,297 French military personnel. Vichy severed diplomatic relations but did not declare war on Britain. Churchill also ordered French ships in British ports to be seized by the Royal Navy. The French squadron at

Alexandria, Egypt

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, under Admiral

René-Emile Godfroy, was effectively interned until 1943.

The American position towards Vichy France and Free France was inconsistent. President Roosevelt disliked and distrusted de Gaulle, and agreed with Ambassador Leahy's view that he was an "apprentice dictator."

North Africa

Preparing for a landing in North Africa in late 1942, the US looked for a top French ally. It turned to

Henri Giraud

Henri Honoré Giraud (18 January 1879 – 11 March 1949) was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944.

Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from ...