At the time of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, the area of modern

Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

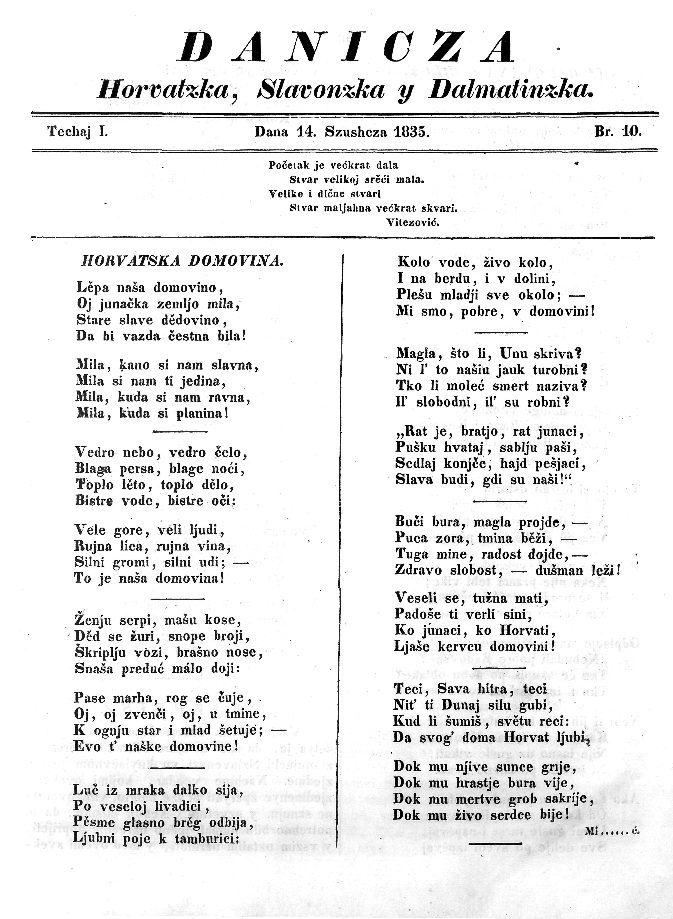

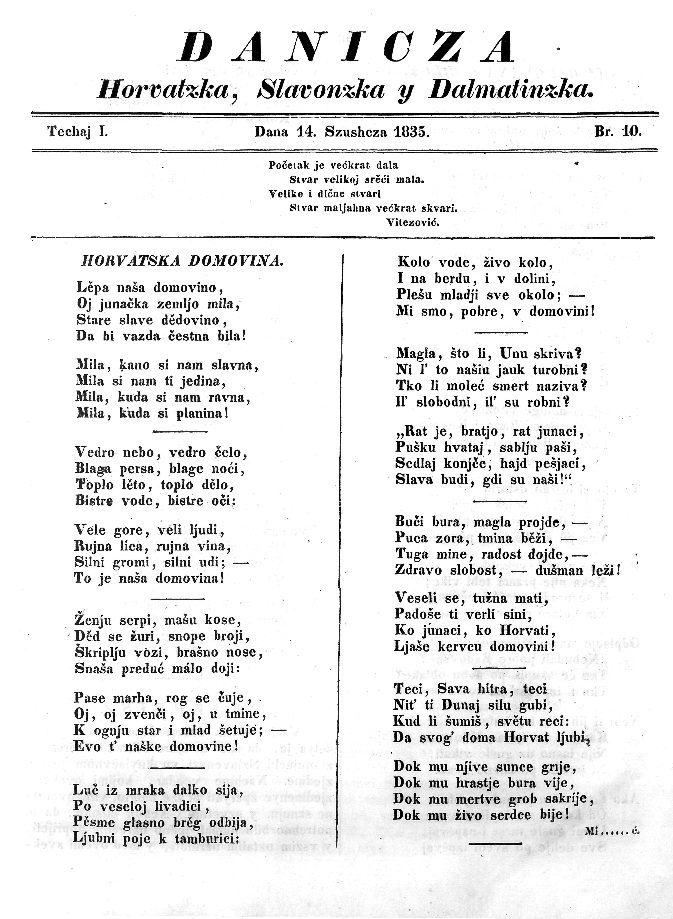

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

comprised two Roman provinces,

Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now west ...

and

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

. After the

collapse

Collapse or its variants may refer to:

Concepts

* Collapse (structural)

* Collapse (topology), a mathematical concept

* Collapsing manifold

* Collapse, the action of collapsing or telescoping objects

* Collapsing user interface elements

** ...

of the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

in the 5th century, the area was subjugated by the

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

for 50 years, before being incorporated into the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

.

Croatia, as a polity, first appeared as a

duchy

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a medieval country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between ...

in the 7th century, the

Duchy of Croatia

The Duchy of Croatia (; also Duchy of the Croats, hr , Kneževina Hrvata; ) was a medieval state that was established by White Croats who migrated into the area of the former Roman province of Dalmatia 7th century CE. Throughout its existenc ...

. With the nearby

Principality of Lower Pannonia

Early Slavs settled in the eastern and southern parts of the former Roman province of Pannonia. The term ''Lower Pannonia'' ( la, Pannonia inferior, hu, Alsó-pannoniai grófság, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Donja Panonija, Доња Панонија, sl, Spo ...

, it was united and elevated into the

Kingdom of Croatia Kingdom of Croatia may refer to:

* Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102), an independent medieval kingdom

* Croatia in personal union with Hungary (1102–1526), a kingdom in personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary

* Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg) (152 ...

which lasted from 925 until 1102. From the 12th century, the Kingdom of Croatia entered a

personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interli ...

with the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

. It remained a distinct state with its ruler (''

Ban

Ban, or BAN, may refer to:

Law

* Ban (law), a decree that prohibits something, sometimes a form of censorship, being denied from entering or using the place/item

** Imperial ban (''Reichsacht''), a form of outlawry in the medieval Holy Roman ...

'') and

Sabor, but it elected royal dynasties from neighboring powers, primarily

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

,

Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

, and the

Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

.

The period from the 15th to the 17th centuries was marked by intense struggles between the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

to the south and the

Habsburg Empire to the north.

Following the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the

dissolution of Austria-Hungary

The dissolution of Austria-Hungary was a major geopolitical event that occurred as a result of the growth of internal social contradictions and the separation of different parts of Austria-Hungary. The reason for the collapse of the state was Worl ...

in 1918, Croatian lands were incorporated into the

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 191 ...

, which was dominated by

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

. Following the German

invasion of Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, or ''Projekt 25'' was a German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was ...

in April 1941, the puppet state

Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

, allied to the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, was established. It was defeated in May 1945, after the

German Instrument of Surrender

The German Instrument of Surrender (german: Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht, lit=Unconditional Capitulation of the " Wehrmacht"; russian: Акт о капитуляции Германии, Akt o kapitulyatsii Germanii, lit=Act of capi ...

. The

Socialist Republic of Croatia

The Socialist Republic of Croatia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Socijalistička Republika Hrvatska, Социјалистичка Република Хрватска), or SR Croatia, was a constituent republic and federated state of the Socia ...

was formed as a

constituent republic

Administrative division, administrative unit,Article 3(1). country subdivision, administrative region, subnational entity, constituent state, as well as many similar terms, are generic names for geographical areas into which a particular, ind ...

of the

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yu ...

. In 1991, Croatia's leadership severed ties with Yugoslavia and

proclaimed independence amidst the

dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Prehistoric period

The area known today as Croatia was inhabited by hominids throughout the

prehistoric period. Fossils of

Neanderthals

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While ...

dating to the middle

Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

period have been unearthed in northern Croatia, with the most famous and best-presented site in

Krapina

Krapina (; hu, Korpona) is a town in northern Croatia and the administrative centre of Krapina-Zagorje County with a population of 4,482 (2011) and a total municipality population of 12,480 (2011). Krapina is located in the hilly Zagorje reg ...

. Remnants of several

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

and

Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "Rock (geology), stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin ''wikt:aeneus, aeneus'' "of copper"), is an list of archaeologi ...

cultures have been found throughout the country. Most of the sites are in the northern Croatian river valleys, and the most significant cultures whose presence was discovered include the

Starčevo

Starčevo () is a town located in the Pančevo municipality, in the South Banat District of Serbia. It is situated in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina. The town has a Serb ethnic majority and its population is 7,473 people ( 2011 census).

The ...

,

Vučedol

Vučedol () is an archeological site, an elevated ground on the right bank of the river Danube near Vukovar that became the eponym of the eneolithic Vučedol culture.

It is estimated that the site had once been home to about 3,000 inhabitants, ma ...

and

Baden cultures. The

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

left traces of the early

Illyrian Hallstatt culture

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western and Central European culture of Late Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe (Hallstatt C, Hallstatt D) from the 8th to 6th centuries ...

and the

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any defi ...

.

Protohistoric period

Greek author

Hecataeus of Miletus

Hecataeus of Miletus (; el, Ἑκαταῖος ὁ Μιλήσιος; c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC), son of Hegesander, was an early Greek historian and geographer.

Biography

Hailing from a very wealthy family, he lived in Miletus, then under ...

mentions that around 500 BC, the Eastern Adriatic region was settled by

Histri The Histri were an ancient people inhabiting the Istrian peninsula, to which they gave the name. Their territory stretched to the neighbouring Gulf of Trieste and bordered the Iapydes in the hinterland of Tarsatica. The Histri formed a kingdom.

...

ans,

Liburnians

The Liburnians or Liburni ( grc, Λιβυρνοὶ) were an ancient tribe inhabiting the district called Liburnia, a coastal region of the northeastern Adriatic between the rivers ''Arsia'' ( Raša) and ''Titius'' ( Krka) in what is now Croati ...

, and

Illyrians

The Illyrians ( grc, Ἰλλυριοί, ''Illyrioi''; la, Illyrii) were a group of Indo-European-speaking peoples who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo-Balkan populations, a ...

. Greek colonization saw settlers establish communities on the Issa (

Vis) and Pharos (

Hvar) islands.

Roman expansion

Before the Roman expansion, the eastern Adriatic coast formed the northern part of the

Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

n kingdom from the 4th century BC to the

Illyrian Wars

The Illyro-Roman Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ardiaei kingdom. In the ''First Illyrian War'', which lasted from 229 BC to 228 BC, Rome's concern was that the trade across the Adriatic Sea increased after the ...

in the 220s BC. In 168 BC, the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

established its protectorate south of the

Neretva

The Neretva ( sr-cyrl, Неретва, ), also known as Narenta, is one of the largest rivers of the eastern part of the Adriatic basin. Four HE power-plants with large dams (higher than 150,5 metres) provide flood protection, power and water s ...

river. The area north of the Neretva was slowly incorporated into Roman possession until the

province of Illyricum was formally established 32–27 BC.

These lands then became part of the Roman province of

Illyricum. Between 6 and 9 AD, tribes including the

Dalmatae

The Delmatae, alternatively Dalmatæ, during the Roman period, were a group of Illyrian tribes in Dalmatia, contemporary southern Croatia and western Bosnia and Herzegovina. The region of Dalmatia takes its name from the tribe.

The Delmatae ap ...

, who gave name to these lands, rose up against the Romans in the

Great Illyrian revolt

The (Latin for 'War of the Batos') was a military conflict fought in the Roman province of Illyricum in the 1st century AD, in which an alliance of native peoples of the two regions of Illyricum, Dalmatia and Pannonia, revolted against the Roma ...

, but the uprising was crushed, and in 10 AD Illyricum was split into two provinces—

Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now west ...

and Dalmatia. The

province of Dalmatia spread inland to cover all of the

Dinaric Alps

The Dinaric Alps (), also Dinarides, are a mountain range in Southern and Southcentral Europe, separating the continental Balkan Peninsula from the Adriatic Sea. They stretch from Italy in the northwest through Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herz ...

and most of the eastern Adriatic coast. Dalmatia was the birthplace of the Roman Emperor

Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

, who, when he retired as Emperor in 305 AD, built a

large palace near

Salona

Salona ( grc, Σάλωνα) was an ancient city and the capital of the Roman province of Dalmatia. Salona is located in the modern town of Solin, next to Split, in Croatia.

Salona was founded in the 3rd century BC and was mostly destroyed in ...

, from which the city of

Split later developed.

Historians such as

Theodore Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th centur ...

and

Bernard Bavant argue that all of Dalmatia was fully Romanized and

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

-speaking by the 4th century. Others, such as

Aleksandar Stipčević, argue that the process of

Romanization

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, a ...

was selective and involved mostly the urban centers but not the countryside, where previous Illyrian socio-political structures were adapted to Roman administration and political structure only where necessary. has argued that the

Vlachs

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other Easte ...

, or Morlachs, were Latin-speaking, pastoral peoples who lived in the Balkan mountains since pre-Roman times. They are mentioned in the oldest Croatian chronicles.

After the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

collapsed in 476, with the beginning of the

Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roma ...

,

Julius Nepos briefly ruled his diminished domain from Diocletian's Palace after his 476 flight from Italy. The region was then ruled by the

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

until 535 when

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

added the territory to the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Later, the Byzantines formed the

Theme of Dalmatia in the same territory.

Migration period

The Roman period ended with the

Avar and

Croat

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, Ge ...

invasions in the 6th and 7th centuries and the destruction of almost all Roman towns. Roman survivors retreated to more favorable sites on the coast, islands, and mountains. The city of

Ragusa was founded by survivors from

Epidaurum.

According to the work ''

De Administrando Imperio

''De Administrando Imperio'' ("On the Governance of the Empire") is the Latin title of a Greek-language work written by the 10th-century Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine VII. The Greek title of the work is ("To yown son Romanos"). It is a domes ...

'', written by the 10th-century Byzantine Emperor

Constantine VII

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe ...

, the Croats arrived in what is today Croatia from

southern Poland and

Western Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of Ukraine linked to the former Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, which was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austr ...

in the early 7th century. However, that claim is disputed and competing hypotheses date the event between late the 6th-early 7th (mainstream) or the late 8th-early 9th (fringe) centuries.

[Mužić (2007), pp. 249–293] Recent archaeological data established that the migration and settlement of the Slavs/Croats occurred in the late 6th and early 7th centuries.

Duchy of Croatia (800–925)

From the middle of the seventh century until the unification in 925, there were two duchies on the territory of today's Croatia,

Duchy of Croatia

The Duchy of Croatia (; also Duchy of the Croats, hr , Kneževina Hrvata; ) was a medieval state that was established by White Croats who migrated into the area of the former Roman province of Dalmatia 7th century CE. Throughout its existenc ...

and

Principality of Lower Pannonia

Early Slavs settled in the eastern and southern parts of the former Roman province of Pannonia. The term ''Lower Pannonia'' ( la, Pannonia inferior, hu, Alsó-pannoniai grófság, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Donja Panonija, Доња Панонија, sl, Spo ...

. Eventually, a

dukedom

Dukedom may refer to:

* The title and office of a duke

* Duchy, the territory ruled by a duke

* Dukedom, Kentucky and Tennessee, United States

* ''Dukedom'' (game), a land management game

See also

* Lists of dukedoms

Lists of dukedoms include:

...

was formed, the

Duchy of Croatia

The Duchy of Croatia (; also Duchy of the Croats, hr , Kneževina Hrvata; ) was a medieval state that was established by White Croats who migrated into the area of the former Roman province of Dalmatia 7th century CE. Throughout its existenc ...

, ruled by

Borna, as attested by chronicles of

Einhard

Einhard (also Eginhard or Einhart; la, E(g)inhardus; 775 – 14 March 840) was a Frankish scholar and courtier. Einhard was a dedicated servant of Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious; his main work is a biography of Charlemagne, the ''Vita ...

starting in the year 818. The record represents the first documented Croatian realms,

vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back t ...

s of

Francia

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks du ...

at the time.

[Mužić (2007), pp. 157–160] The most important ruler of Lower Pannonia was

Ljudevit Posavski

Ljudevit () or Liudewit ( la, Liudewitus), often also , was the Duke of the Slavs in Lower Pannonia from 810 to 823. The capital of his realm was in Sisak (today in Croatia). As the ruler of the Pannonian Slavs, he led a resistance to Frankish do ...

, who fought against the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

between 819 and 823. He ruled Pannonian Croatia from 810 to 823.

The Frankish overlordship ended during the reign of

Mislav two decades later.

[Mužić (2007), pp. 169–170] Duke Mislav was succeeded by

Duke Trpimir, the founder of the

Trpimirović dynasty. Trpimir successfully fought against

Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

, Venice and

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

. Duke Trpimir was succeeded by

Duke Domagoj, who repeatedly led wars against the Venetians and the Byzantines, and the Venetians called this Croatian ruler "the worst Croatian prince" (dux pessimus Croatorum). According to Constantine VII, the

Christianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

of Croats began in the 7th century, but the claim is disputed and generally, Christianization is associated with the 9th century. In 879, under

Branimir, the duke of Croatia,

Dalmatian Croatia received papal recognition as a state from

Pope John VIII

Pope John VIII ( la, Ioannes VIII; died 16 December 882) was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 14 December 872 to his death. He is often considered one of the ablest popes of the 9th century.

John devoted much of his papacy ...

.

[Mužić (2007), pp. 195–198]

Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)

The first king of Croatia is generally considered to have been

Tomislav

Tomislav (, ) is a masculine given name of Slavic origin, that is widespread amongst the South Slavs.

The meaning of the name ''Tomislav'' is thought to have derived from the Old Slavonic verb "'' tomiti''" or "'' tomit" meaning to "''languish ...

in the first half of the 10th century, who is mentioned as such in letters regarding

Church Councils of Split, as well as in ''

De Administrando Imperio

''De Administrando Imperio'' ("On the Governance of the Empire") is the Latin title of a Greek-language work written by the 10th-century Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine VII. The Greek title of the work is ("To yown son Romanos"). It is a domes ...

''. The latter also describes Tomislav's army driving off the Bulgarian invasion of Croatia in the 926

Battle of Bosnian Highlands.

Other important Croatian rulers from that period are:

Mihajlo Krešimir II

Mihajlo ( sr-cyr, Михајло) is the Serbian variant of the name '' Michael'', predominantly borne by ethnic Serbs. It is also spelled Mihailo (Михаило) and Mijailo (Мијаило).

;Science

*Mihajlo Pupin, Serbian physicist

* Mihajl ...

, 949-969, who conquered

Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

and restored the power of the Croatian kingdom,

Stjepan Držislav, 969- 997, is an ally of

Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

in the war with the

Bulgarian emperor

Samuil,

Stjepan, 1030- 1058, restored the Croatian kingdom and founded the

diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associ ...

in

Knin

Knin (, sr, link=no, Книн, it, link=no, Tenin) is a city in the Šibenik-Knin County of Croatia, located in the Dalmatian hinterland near the source of the river Krka, an important traffic junction on the rail and road routes between Zagr ...

.

Two Croatian queens are also known from that century, and

Helen of Zadar

Helen of Zadar ( hr, Jelena) (died 8 October 976), also known as Helen the Glorious, was the queen consort of the Kingdom of Croatia (medieval), Kingdom of Croatia, as the wife of King Michael Krešimir II of Croatia, Michael Krešimir II, from 9 ...

, whose epitaph was found in the

Solin area at the end of the 19th century during archeological excavations conducted by

Frane Bulić

Frane Bulić (October 4, 1846 - July 29, 1934) was a Croats, Croatian priest, archaeologist, and historian.

Biography

Bulić was born in Vranjic (now part of Solin), and studied theology in Zadar and then classical philology and archeology in ...

.

The medieval Croatian kingdom reached its peak in the 11th century during the reigns of

Petar Krešimir IV (1058–1074) and

Demetrius Zvonimir

Demetrius Zvonimir ( hr, Dmitar Zvonimir, ; died 1089) was a King of Dalmatia and Croatia from 1076 until his death in 1089. He was crowned as king in Solin on 8 October 1076. Zvonimir also served as Ban of Croatia (1064–1074), and was named ...

(1075–1089).

When

Stjepan II died in 1091, ending the

Trpimirović dynasty,

Ladislaus I of Hungary claimed the Croatian crown on the basis of Zvonimir's wife

Jelena (Helen), who was the daughter of Hungarian king

Béla I. Opposition to this claim led to a

war between the army loyal to

Petar Sančić and the army loyal to the Hungarian king Koloman I, and after the defeat of Petar Sančić's army, a

personal union of Croatia and Hungary was created in 1102, with

Coloman Coloman, es, Colomán (german: Koloman (also Slovak, Czech, Croatian), it, Colomanno, ca, Colomà; hu, Kálmán)

The Germanic origin name Coloman used by Germans since the 9th century.

* Coloman, King of Hungary

* Coloman of Galicia-Lodomeri ...

. as ruler.

Personal union with Hungary (1102–1527) and the Republic of Venice

Croatia under the Árpád dynasty

One consequence of entering a personal union with Hungary under the Hungarian king was the introduction of a

feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

. Later kings sought to restore some of their influence by giving certain privileges to the towns. Over the next four centuries, the Kingdom of Croatia was governed by the

Sabor (parliament) and a

Ban

Ban, or BAN, may refer to:

Law

* Ban (law), a decree that prohibits something, sometimes a form of censorship, being denied from entering or using the place/item

** Imperial ban (''Reichsacht''), a form of outlawry in the medieval Holy Roman ...

(viceroy) appointed by the king.

In the year 1217, the Hungarian king

Andrew II took the

sign of the cross

Making the sign of the cross ( la, signum crucis), or blessing oneself or crossing oneself, is a ritual blessing made by members of some branches of Christianity. This blessing is made by the tracing of an upright cross or + across the body with ...

and vowed to go on the

Fifth Crusade. After assembling his army, he marched from Hungary proper south to

Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

and then

Knin

Knin (, sr, link=no, Книн, it, link=no, Tenin) is a city in the Šibenik-Knin County of Croatia, located in the Dalmatian hinterland near the source of the river Krka, an important traffic junction on the rail and road routes between Zagr ...

, after which he proceeded to

Split on the Adriatic coast. The king and his party sailed to

the Holy Land. Andrew's son

King Béla IV had to deal with troubles brought by the

first Mongol invasion of Hungary. Following the Hungarian defeat in the

Battle of the Sajó River in 1241, the king withdrew to Dalmatia, hoping to take refuge there, with the Mongols in pursuit. The Mongols finally withdrew on receiving news of the death of

Ögedei Khan

Ögedei Khagan (also Ogodei;, Mongolian: ''Ögedei'', ''Ögüdei''; – 11 December 1241) was second khagan-emperor of the Mongol Empire. The third son of Genghis Khan, he continued the expansion of the empire that his father had begun.

...

. As Croatian historian Damir Karbić notes, during Béla's stay in Dalmatia, members of the Šubić noble family earned merit for sheltering him, so in return, the king granted them the County of

Bribir, where their power reached its peak during the time of

Paul I Šubić of Bribir.

This period, therefore, saw the rise of the

Frankopan

The House of Frankopan ( hr, Frankopani, Frankapani, it, Frangipani, hu, Frangepán, la, Frangepanus, Francopanus), was a Croatian noble family, whose members were among the great landowner magnates and high officers of the Kingdom of Croat ...

s and the

Šubićs, native nobility, to prominence. Numerous future Bans of Croatia originated from these two noble families.

The princes of Bribir from the Šubić family became particularly influential, as they asserted their control over large parts of Dalmatia,

Slavonia

Slavonia (; hr, Slavonija) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria, one of the four historical regions of Croatia. Taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with five Croatian counties: Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Bar ...

, and even Bosnia.

Croatia under the Anjou dynasty

Lord

Paul Šubić accumulated so much power, that he ruled as a de facto independent ruler. He coined his own money and held the hereditary title of Ban of Croatia. Following the death of king

Ladislaus IV of Hungary

Ladislaus IV ( hu, IV. (Kun) László, hr, Ladislav IV. Kumanac, sk, Ladislav IV. Kumánsky; 5 August 1262 – 10 July 1290), also known as Ladislaus the Cuman, was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1272 to 1290. His mother, Elizabeth, wa ...

, who had no male heir, a succession crisis emerged, and in 1300, Paul invited

Charles Robert of Anjou

Charles I, also known as Charles Robert ( hu, Károly Róbert; hr, Karlo Robert; sk, Karol Róbert; 128816 July 1342) was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1308 to his death. He was a member of the Capetian House of Anjou and the only son of ...

to come to the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

and take over its royal seat. A civil war ensued, in which Charles' party prevailed after winning a decisive victory in the

Battle of Rozgony in 1312.

Coronations of the kings of Croatia gradually fell into abeyance as a custom. Charles Robert was the last to be separately crowned as King of Croatia in 1301, after which Croatia had a separate constitution. Lord Paul Šubić died in 1312, and his son

Mladen

Mladen () is a South Slavic masculine given name, derived from the Slavic root ''mlad'' (, ), meaning "young". It is present in Bulgarian, Serbian, and Croatian society since the Middle Ages.

Notable people with the name include:

* Mladen (vojv ...

inherited the title of Ban of Croatia. Mladen's power was diminished due to the new king's policy of centralization, after he and his forces were defeated by the royal army and its allies in the

Battle of Bliska in 1322. The power vacuum caused by the downfall of Mladen Šubić was used by Venice to reassert control over Dalmatian cities.

The ensuing reign of King

Louis the Great (1342–1382) is considered the golden age of medieval Croatian history. Louis launched a campaign against Venice, with aim of retaking Dalmatian cities, and eventually succeeded, forcing Venice to sign the

Treaty of Zadar

The Treaty of Zadar, also known as the Treaty of Zara, was a peace treaty signed in Zadar, Dalmatia on February 18, 1358 by which the Venetian Republic lost influence over its Dalmatian holdings. The Treaty of Zadar ended hostilities between Lo ...

in 1358. The same peace treaty caused the

Republic of Ragusa

The Republic of Ragusa ( dlm, Republica de Ragusa; la, Respublica Ragusina; it, Repubblica di Ragusa; hr, Dubrovačka Republika; vec, Repùblega de Raguxa) was an aristocratic maritime republic centered on the city of Dubrovnik (''Ragusa'' ...

to gain independence from Venice.

Anti-Court Movement

Following Louis' death in 1382, the Kingdom of Hungary and parts of Croatia descended into a civil war between parties led by his daughter

Mary, and her fiancé

Sigismund of Luxemburg on one side, and supporters of the so-called

Anti-Court Movement on another.

Ladislaus of Naples sold the entirety of Dalmatia to

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

in 1409. The period saw an increasing threat of

Ottoman conquest and struggle against the

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

for control of coastal areas. The Venetians gained control over most of Dalmatia by 1428. With the exception of the

city-state of Dubrovnik, which became independent,

[Frucht 2005, p. 422-423] the rule of Venice over most of Dalmatia lasted nearly four centuries ( 1420–1797).

In 1490, the estates of Croatia declined to recognize

Vladislaus II until he had taken an oath to respect their liberties and insisted that he strike from the constitution certain phrases which seemed to reduce Croatia to the rank of a mere province. The dispute was resolved in 1492.

Ottoman expansion

As the

Ottoman expansion into Europe started, Croatian lands became a place of permanent warfare. This period of history is considered to be one of the direst for the people living in Croatia. The Ottoman conquest of Croatian lands began after the fall of

Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

to the Ottomans in 1463. Armies of Croatian nobility fought numerous battles to counter the Ottoman

akinji and

martolos raids.

The Ottoman forces raided the Croatian countryside, plundering towns and villages, then captured the local inhabitants as slaves. These "

scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

" tactics, also called "The Small War", were usually conducted once a year and were intended to soften up the region's defenses, but didn't result in actual conquest of territory. But combined with famines, diseases, and a cold climate, they caused vast depopulation and a refugee crisis, as people fled to safer areas. Croatian historian

Ivan Jurković points out that due to the combination of these factors, Croatia "lost almost three-fifths of its population" and the compactness of its territory. The center of the Croatian medieval state gradually shifted north into western

Slavonia

Slavonia (; hr, Slavonija) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria, one of the four historical regions of Croatia. Taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with five Croatian counties: Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Bar ...

(Zagreb).

led to the 1493

Battle of Krbava field and the 1526

Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

, both ending in decisive Ottoman victories.

Croatia in the Habsburg monarchy (1527–1918)

Remnants of the remnants

Croats fought an increasing number of battles, but lost increasing swathes of territory to the Ottoman Empire, until being reduced to what is commonly called in Croatian historiography the "Remains of the Remains of Once Glorious Croatian Kingdom" (''Reliquiae reliquiarum olim inclyti regni Croatiae''), or simply the "Remains of the Remains".

A decisive battle with the

Ottomans occurred on Mohács in 1526 where Hungarian king

Louis II was killed. As a consequence, in November of the same year, the Hungarian parliament elected

János Szapolyai

János or Janos may refer to:

* János, male Hungarian given name, a variant of John

Places

* Janos Municipality, a municipality of Chihuahua

** Janos, Chihuahua, town in Mexico

** Janos Biosphere Reserve, a nature reserve in Chihuahua

* Janos ...

as the new king of Hungary. In December 1526, another Hungarian parliament elected Ferdinand Habsburg as King of Hungary.

The Croatian nobles

met in Cetingrad in 1527 and chose Ferdinand I of the

House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

as the new ruler of Croatia, on the condition that he contribute to the defense of Croatia against the Ottomans, and respect its political rights.

The Diet of Slavonia, on the other hand, elected Szapolyai. A civil war between the two rival kings ensued, but later both crowns united as the Habsburgs prevailed over Szapolyai. The Ottoman Empire used these instabilities to expand in the 16th century to include most of Slavonia, western Bosnia (then called

Turkish Croatia), and

Lika

Lika () is a traditional region of Croatia proper, roughly bound by the Velebit mountain from the southwest and the Plješevica mountain from the northeast. On the north-west end Lika is bounded by Ogulin-Plaški basin, and on the south-east b ...

. Those territories initially made up part of

Rumelia Eyalet

The Eyalet of Rumeli, or Eyalet of Rumelia ( ota, ایالت روم ایلی, ), known as the Beylerbeylik of Rumeli until 1591, was a first-level province ('' beylerbeylik'' or ''eyalet'') of the Ottoman Empire encompassing most of the Balkans (" ...

, and subsequently parts of

Budin Eyalet

Budin Eyalet (also known as Province of Budin/Buda or Pashalik of Budin/Buda, ota, ایالت بودین, Eyālet-i Budin) was an administrative territorial entity of the Ottoman Empire in Central Europe and the Balkans. It was formed on the te ...

,

Bosnia Eyalet

The Eyalet of Bosnia ( ota, ایالت بوسنه ,Eyālet-i Bōsnâ; By Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters ; sh, Bosanski pašaluk), was an eyalet (administrative division, also known as a ''beylerbeylik'') of the Ottoman Empire, mostly based o ...

, and

Kanije Eyalet.

Later in the same century, Croatia was so weak that its parliament authorized Ferdinand Habsburg to carve out large areas of Croatia and Slavonia adjacent to the Ottoman Empire for the creation of the

Military Frontier (''Vojna Krajina'', German: ''Militaergrenze'') - a buffer zone for the Ottoman Empire managed directly by the

Imperial War Council

The ''Hofkriegsrat'' (or Aulic War Council, sometimes Imperial War Council) established in 1556 was the central military administrative authority of the Habsburg monarchy until 1848 and the predecessor of the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War. The ...

in Austria. This buffer area became depopulated due to constant warfare and was subsequently settled by

Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of ...

,

Vlachs

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other Easte ...

, Croats, and

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

. As a result of their compulsory military service to the Habsburg Empire during the conflict with the Ottoman Empire, the population in the Military Frontier was free of serfdom and enjoyed much political autonomy, unlike the population living in the parts managed by the Croatian Ban and Sabor, This was officially confirmed by an Imperial decree of 1630 called ''

Statuta Valachorum

''Statuta Valachorum'' ("Vlach Statute(s)", sh, Vlaški statut(i)) was a decree issued by Emperor Ferdinand II of the Habsburg monarchy on 5 October 1630 that defined the rights of "Vlachs" (a term used for a community of mostly Orthodox refugees, ...

'' (Vlach Statutes).

After the town of

Bihać fell to the Ottomans in 1592, little of Croatia remained unconquered. The Ottoman army was successfully repelled for the first time on the territory of Croatia after the

Battle of Sisak in 1593.

Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy

During the 17th century, distinguished Croatian noble

Nikola Zrinski

Nikola () is a given name which, like Nicholas, is a version of the Greek ''Nikolaos'' (Νικόλαος). It is common as a masculine given name in the South Slavic countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, North Macedonia, Monten ...

became one of the most prominent Croatian generals in the fight against the Ottomans. In 1663/1664 he led a successful incursion into Ottoman-controlled territory. The campaign ended in the destruction of the vital

Osijek

Osijek () is the fourth-largest city in Croatia, with a population of 96,848 in 2021. It is the largest city and the economic and cultural centre of the eastern Croatian region of Slavonia, as well as the administrative centre of Osijek-Baranja ...

bridge, which served as a connection between the Pannonian plain and the Balkan territories. As a reward for his victory against the Ottomans, Zrinski was commended by French king

Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

, thereby establishing contact with the French court. Croatian nobility also constructed

Novi Zrin castle which sought to protect Croatia and Hungary from further Ottoman advances. At the same time, emperor

Leopold of Habsburg sought to impose absolute rule on the entire Habsburg territory, which meant a loss of authority for the Croatian parliament and Ban and caused dissatisfaction with Habsburg rule among Croats.

[Macan, 108-110]

In July 1664, a large Ottoman army

besieged and destroyed Novi Zrin. As this army marched on Austrian lands, its campaign ended at the

Battle of St. Gotthard, where it was destroyed by the Habsburg imperial army. Given this victory, Croatians expected a decisive Habsburg counter-offensive to push the Ottomans back and relieve pressure on Croatian lands, but Leopold decided to conclude the unfavorable

Vasvar peace treaty with the Ottomans because it solved problems he had on the Rhine with the French at the time. In Croatia, his decision caused outrage among leading nobles and sparked a conspiracy to replace the Habsburgs with different rulers. After

Nikola Zrinski

Nikola () is a given name which, like Nicholas, is a version of the Greek ''Nikolaos'' (Νικόλαος). It is common as a masculine given name in the South Slavic countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, North Macedonia, Monten ...

died under unusual circumstances while hunting, his relatives

Fran Krsto Frankopan

Fran Krsto Frankopan ( hu, Frangepán Ferenc Kristóf; 4 March 1643 – 30 April 1671) was a Croatian baroque poet, nobleman and politician. He is remembered primarily for his involvement in the failed Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy. He was a ...

and

Petar Zrinski supported the conspiracy.

The conspirators established contact with the

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

,

Venetians,

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in ...

, and eventually even the Ottomans, only to be discovered by Habsburg spies at the Ottoman court who served as the sultan's translators. The conspirators were invited to reconcile with the emperor, to which they agreed. However, when they came to Austria, they were charged with high treason and sentenced to death. They were executed in

Wiener Neustadt

Wiener Neustadt (; ; Central Bavarian: ''Weana Neistod'') is a city located south of Vienna, in the state of Lower Austria, in northeast Austria. It is a self-governed city and the seat of the district administration of Wiener Neustadt-Land Distr ...

in April 1671. Their families, whose history was intertwined with centuries of Croatian history, were subsequently eradicated by imperial authorities, and all of their possessions were confiscated.

Great Turkish War: A revived Croatia

Despite the decline of Ottoman might in the 17th century, the Ottoman high command decided to

attack the Habsburg capital of Vienna in 1683, as the

Vasvár peace treaty was about to expire. Their attack, however, ended in disaster, and the Ottomans were ultimately routed near Vienna by joint Christian armies defending the city. Soon thereafter, the

Holy League was formed and the

Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War (german: Großer Türkenkrieg), also called the Wars of the Holy League ( tr, Kutsal İttifak Savaşları), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Pola ...

was launched. In the Croatian theater of operations, several commanders distinguished themselves, including friar

Luka Ibrišimović, whose rebels defeated the Ottomans in

Požega, and

Marko Mesić, who led the anti-Ottoman uprising in

Lika

Lika () is a traditional region of Croatia proper, roughly bound by the Velebit mountain from the southwest and the Plješevica mountain from the northeast. On the north-west end Lika is bounded by Ogulin-Plaški basin, and on the south-east b ...

.

Hajduk leader

Stojan Janković

Stojan Janković Mitrović ( sr-cyr, Стојан Јанковић Митровић; also known as ''Stoian Jancovich Mitrovich'', ''Stoian Mitrovich'', ''Stoiano Mitrovich''; about 1636 – 23 August 1687) was the commander of the Morlach troo ...

distinguished himself by leading troops in

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

. Croatian Ban

Nikola (Miklos) Erdody led his troops in battles for

Virovitica, which was liberated from the Ottomans in 1684.

Osijek

Osijek () is the fourth-largest city in Croatia, with a population of 96,848 in 2021. It is the largest city and the economic and cultural centre of the eastern Croatian region of Slavonia, as well as the administrative centre of Osijek-Baranja ...

was liberated by 1687,

Kostajnica was liberated by 1688, and

Slavonski Brod was liberated by 1691. A siege of

Bihać was also attempted in 1687 but was called off due to lack a of cannons. In the same year, general

Eugene of Savoy

Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy–Carignano, (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736) better known as Prince Eugene, was a field marshal in the army of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Austrian Habsburg dynasty during the 17th and 18th centuries. He ...

led a 6500-strong army from Osijek into Bosnia, where he raided the seat of

Bosnia Eyalet

The Eyalet of Bosnia ( ota, ایالت بوسنه ,Eyālet-i Bōsnâ; By Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters ; sh, Bosanski pašaluk), was an eyalet (administrative division, also known as a ''beylerbeylik'') of the Ottoman Empire, mostly based o ...

,

Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

, burning it to the ground. After this raid, large groups of Christian refugees from Bosnia settled in what was then an almost empty Slavonia. After the decisive Ottoman defeat in the

Battle of Zenta

The Battle of Zenta, also known as the Battle of Senta, was fought on 11 September 1697, near Zenta, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Senta, Serbia), between Ottoman and Holy League armies during the Great Turkish War. The battle was the most de ...

in 1697 by the forces of

Eugene of Savoy

Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy–Carignano, (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736) better known as Prince Eugene, was a field marshal in the army of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Austrian Habsburg dynasty during the 17th and 18th centuries. He ...

, the

Peace of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by ...

was signed in 1699, confirming the liberation of all of Slavonia from the Ottomans. For Croatia, nonetheless, large chunks of its late medieval territories between the rivers

Una and

Vrbas were lost, as they remained part of the Ottoman

Bosnia Eyalet

The Eyalet of Bosnia ( ota, ایالت بوسنه ,Eyālet-i Bōsnâ; By Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters ; sh, Bosanski pašaluk), was an eyalet (administrative division, also known as a ''beylerbeylik'') of the Ottoman Empire, mostly based o ...

. In the following years, the use of the German language spread in the new military borderland and proliferated over the next two centuries as German-speaking colonists settled in the borderlands.

Enlightened despotism

By the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire had been driven out of Hungary, and Austria brought the empire under central control. Since the emperor

Charles VI had no male heirs, he wanted to leave the imperial throne to his daughter

Maria Theresa of Austria

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position '' suo jure'' (in her own right) ...

, which eventually led to the

War of Austrian Succession of 1741–1748. The Croatian Parliament decided to accept Maria Theresa as a legitimate ruler by drafting the

Pragmatic Sanction of 1712, asking in return that whoever inherited the throne recognize and respect Croatian autonomy from Hungary. The king unwillingly granted this. The rule of Maria Theresa brought limited modernization in education and health care. Croatian Royal Council (''Consilium Regni Croatiae''), which served as the de facto Croatian government, was founded in Varaždin in 1767, but it was abolished in 1779 and its authority was passed to Hungary. The foundation of the Croatian Royal Council in

Varaždin

)

, image_photo =

, image_skyline =

, image_flag = Flag of Varaždin.svg

, flag_size =

, image_seal =

, seal_size =

, image_shield = Grb_Grad ...

made this town the administrative capital of Croatia, however, a large fire in 1776 caused significant damage to the city, so these major Croatian administrative institutions moved to Zagreb.

Maria Theresa's heir,

Joseph II of Austria

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 un ...

, also ruled in an enlightened absolutist manner, but his reforms were marked by attempts at centralization and Germanization. In this period, roads were built connecting

Karlovac

Karlovac () is a city in central Croatia. According to the 2011 census, its population was 55,705.

Karlovac is the administrative centre of Karlovac County. The city is located on the Zagreb-Rijeka highway and railway line, south-west of Zagre ...

with

Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Prim ...

, and

Jozefina connecting

Karlovac

Karlovac () is a city in central Croatia. According to the 2011 census, its population was 55,705.

Karlovac is the administrative centre of Karlovac County. The city is located on the Zagreb-Rijeka highway and railway line, south-west of Zagre ...

with

Senj. With the

Treaty of Sistova, which ended the

Austro-Turkish War (1788-1791), the Ottoman-held areas of

Donji Lapac

Donji Lapac ( sr-Cyrl, Доњи Лапац) is a settlement and a municipality in Lika, Croatia.

Geography

Donji Lapac is located a region of eastern Lika called ''Ličko Pounje'', by the river Una that flows near the town in the valley betwe ...

and

Cetingrad, along with the villages of

Drežnik Grad and

Jasenovac, were ceded to the Habsburg monarchy and incorporated into the

Croatian Military Frontier

The Croatian Military Frontier ( hr, Vojna krajina or ') was a district of the Military Frontier, a territory in the Habsburg monarchy, first during the period of the Austrian Empire and then during Austria-Hungary.

History

Founded in the late 1 ...

.

19th century in Croatia

Napoleonic Wars

As

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

's armies started to dominate Europe, Croatian lands came into contact with the French as well. When Napoleon abolished the

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

in 1797, former Venetian possessions in

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

came under Habsburg rule. In 1809, as Napoleon defeated the Austrians in the

Battle of Wagram

The Battle of Wagram (; 5–6 July 1809) was a military engagement of the Napoleonic Wars that ended in a costly but decisive victory for Emperor Napoleon's French and allied army against the Austrian army under the command of Archduke Charles ...

, French-controlled territory eventually expanded to the

Sava

The Sava (; , ; sr-cyr, Сава, hu, Száva) is a river in Central and Southeast Europe, a right-bank and the longest tributary of the Danube. It flows through Slovenia, Croatia and along its border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, and finally t ...

river. The French founded the "

Illyrian Provinces

The Illyrian Provinces sl, Ilirske province hr, Ilirske provincije sr, Илирске провинције it, Province illirichegerman: Illyrische Provinzen, group=note were an autonomous province of France during the First French Empire that e ...

" centered in

Ljubljana

Ljubljana (also known by other historical names) is the capital and largest city of Slovenia. It is the country's cultural, educational, economic, political and administrative center.

During antiquity, a Roman city called Emona stood in the ar ...

and appointed Marshal

Auguste de Marmont

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont (20 July 1774 – 22 March 1852) was a French general and nobleman who rose to the rank of Marshal of the Empire and was awarded the title (french: duc de Raguse). In the Peninsular War Marmont succeede ...

as their governor-general. The French presence brought the liberal ideas of the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

to the Croats. The French founded

Masonic lodges, built infrastructure, and printed the first newspapers in the local language in Dalmatia. Called ''

Kraglski Datmatin/Il Regio Dalmata'', it was printed in both Italian and Croatian. Croatian soldiers accompanied Napoleon in his conquests as far as Russia. In 1808, Napoleon abolished the

Republic of Ragusa

The Republic of Ragusa ( dlm, Republica de Ragusa; la, Respublica Ragusina; it, Repubblica di Ragusa; hr, Dubrovačka Republika; vec, Repùblega de Raguxa) was an aristocratic maritime republic centered on the city of Dubrovnik (''Ragusa'' ...

. Ottomans from Bosnia raided French Croatia and occupied the area of

Cetingrad in 1809. Auguste de Marmont reacted by occupying Bihać on 5 May 1810. After the Ottomans promised to stop raiding French territories and withdraw from the Cetingrad, he withdrew from Bihać.

With the fall of Napoleon, the French-controlled Croatian lands came back under Austrian rule.

Croatian national revival and the Illyrian Movement

Under the influence of German

romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, French political thought and

pan-Slavism, Croatian

romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

emerged in the mid-19th century to counteract the

Germanization and

Magyarization

Magyarization ( , also ''Hungarization'', ''Hungarianization''; hu, magyarosítás), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in Austro-Hungarian Transleitha ...

of Croatia.

Ljudevit Gaj

Ljudevit Gaj (; born Ludwig Gay; hu, Gáj Lajos; 8 August 1809 – 20 April 1872) was a Croatian linguist, politician, journalist and writer. He was one of the central figures of the pan-Slavist Illyrian movement.

Biography

Origin

He was bor ...

emerged as a leader of the Croatian national movement. One of the important issues to be resolved was the question of language, where regional Croatian dialects had to be standardized. Since the

Shtokavian dialect

Shtokavian or Štokavian (; sh-Latn, štokavski / sh-Cyrl, italics=no, штокавски, ) is the prestige dialect of the pluricentric language, pluricentric Serbo-Croatian language and the basis of its Serbian language, Serbian, Croatian l ...

, widespread among Croats, was also common with Serbs, this movement likewise had a South-Slavic characteristic.

[Macan, 134-142] At the time, "Croatian" only referred to the population in southwestern parts of what is today Croatia, while "Illyrian" was used throughout the south-Slavic world; wider masses of people were attempted to attract by using the Illyrian name.

Illyrian activists chose the Shtokavian dialect over

Kajkavian

Kajkavian (Kajkavian noun: ''kajkavščina''; Shtokavian adjective: ''kajkavski'' , noun: ''kajkavica'' or ''kajkavština'' ) is a South Slavic regiolect or language spoken primarily by Croats in much of Central Croatia, Gorski Kotar and no ...

as the standardized version of Croatian language. The Illyrian movement was not accepted by the Serbs or the Slovenes, and it remained strictly a Croatian national movement. In 1832, Croatian count

Janko Drašković

Janko Drašković ( Hungarian: ''Draskovich János''; 20 October 1770 – 14 January 1856) was a Croatian politician associated with the beginnings of the 19th-century national revival, the Illyrian movement. He studied law and philosophy befor ...

wrote a manifesto of Croatian national revival called ''

Disertacija'' (''Dissertation''). The manifesto called for the unification of Croatia with Slavonia, Dalmatia, Rijeka, the Military Frontier, Bosnia, and Slovene lands into a single unit inside the Hungarian part of the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

. This unit would have Croatian as the official language and would be governed by

Ban

Ban, or BAN, may refer to:

Law

* Ban (law), a decree that prohibits something, sometimes a form of censorship, being denied from entering or using the place/item

** Imperial ban (''Reichsacht''), a form of outlawry in the medieval Holy Roman ...

.

The movement spread throughout Dalmatia, Istria and among Bosnian

Francisian monks. It resulted in the emergence of the modern Croatian nation and eventually the formation of the first Croatian political parties.

After the usage, the Illyrian name was banned in 1843; the proponents of Illyrianism changed their name to Croatian.

On 2 May 1843,

Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski held the first speech on

Croatian language

Croatian (; ' ) is the standardized variety of the Serbo-Croatian pluricentric language used by Croats, principally in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Serbian province of Vojvodina, and other neighboring countries. It is the offici ...

in the Croatian Sabor, requesting that the Croatian language be made the official language in public institutions. At this point, this was a significant step, because

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

was still in use in public institutions in Croatia. In the Sabor in 1847 Croatian was proclaimed as an official language in Croatia.

Croats in revolutions of 1848

In the

Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europ ...

, the Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia, driven by fear of

Magyar nationalism, supported the Habsburg court against Hungarian revolutionary forces.

During a session of the Croatian Sabor held on 25 March 1848, colonel

Josip Jelačić

Count Josip Jelačić von Bužim (16 October 180120 May 1859; also spelled ''Jellachich'', ''Jellačić'' or ''Jellasics''; hr, Josip grof Jelačić Bužimski; hu, Jelasics József) was a Croatian lieutenant field marshal in the Imperial-Roy ...

was elected as Ban of Croatia and a petition called "

Demands of The People" (''Zahtjevanja naroda'') was drafted to be handed over to the Austrian Emperor. These liberal demands asked for: independence, unification of Croatian lands, a Croatian government responsible to the Croatian parliament and independent from Hungary, financial independence from Hungary, the introduction of the Croatian language in offices and schools, freedom of the press, religious freedom, abolishment of serfdom, abolishment of nobility privileges, the foundation of a people's army, and equality before the law.

As the Hungarian government denied the existence of the Croatian name and nationhood and treated Croatian institutions like provincial authorities, Jelačić severed ties between Croatia and Hungary. In May 1848, Ban's Council was formed which had all the executive powers of the Croatian government. The Croatian parliament abolished feudalism,

serfdom and demanded that the Monarchy become a constitutional federal state of equal nations with independent national governments and one federal parliament in the capital of

Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. The Croatian parliament also demanded the unification of the

Military Frontier and

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

with

Croatia proper. Sabor also asked for an undefined alliance with

Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian and Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian, Italian and Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. The peninsula is located at the head of the Adriatic betwe ...

,

Slovene lands

The Slovene lands or Slovenian lands ( sl, Slovenske dežele or in short ) is the historical denomination for the territories in Central and Southern Europe where people primarily spoke Slovene. The Slovene lands were part of the Illyrian provin ...

and

parts of southern Hungary inhabited with Croats and Serbs. Jelačić was also appointed the governor of

Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Prim ...

and

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

as well as the "Imperial Commander of Military Frontier", thus having most of the Croatian lands under his rule. The breakdown of negotiations between Croats and the Hungarians eventually led to war. Jelačić declared war on Hungary on 7 September 1848. On 11 September 1848, the Croatian army crossed the

river and annexed

Međimurje. Upon crossing Drava, Jelačić ordered his army to switch Croatian national flags with Habsburg Imperial flags.

Despite the contributions of its Ban

Josip Jelačić

Count Josip Jelačić von Bužim (16 October 180120 May 1859; also spelled ''Jellachich'', ''Jellačić'' or ''Jellasics''; hr, Josip grof Jelačić Bužimski; hu, Jelasics József) was a Croatian lieutenant field marshal in the Imperial-Roy ...

in quenching the

Hungarian war of independence, in the aftermath, Croatia was not treated any more favorably by Vienna than the Hungarians and therefore lost its domestic autonomy.

Croatia in Dual Monarchy

The dual monarchy of

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

was created in 1867 through the

Austro-Hungarian Compromise. Croatian autonomy was restored in 1868 with the

Croatian–Hungarian Settlement, which was comparatively favorable for the Croatians, but still problematic because of issues such as the

unresolved status of Rijeka. In 1873, the territory of

Military Frontier was demilitarized and in July 1871 a decision was made to incorporate it into Croatia with Croatian ban

Ladislav Pejačević taking over the authority. Pejačević's successor

Károly Khuen-Héderváry

Count Károly Khuen-Héderváry de Hédervár, born as ''Károly Khuen de Belás'' ( hr, Dragutin Khuen-Héderváry, 23 May 1849 – 16 February 1918) was a Hungarian politician and the Ban of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia in the late nine ...

caused further problems by violating the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement through his hardline

Magyarization

Magyarization ( , also ''Hungarization'', ''Hungarianization''; hu, magyarosítás), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in Austro-Hungarian Transleitha ...

policies in period from 1883 to 1903. Héderváry's magyarization of Croatia led to massive riots in 1903, when Croatian protesters burnt Hungarian flags and clashed with the gendarmes and the military, resulting in the death of several protesters. As a consequence of these riots, Héderváry left his position as Ban of Croatia, but was appointed prime minister of Hungary.

A year earlier, in 1902, ''Srbobran'', the newspaper of

Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

Serbs, published an article titled "Do istrage naše ili vaše" (Until us, or you get exterminated). The article was filled with

Greater Serbian ideology; its text denied the existence of the Croatian nation and the Croatian language and announced Serbian victory over "servile Croats", who would, the article proclaimed, be exterminated.

The article sparked major anti-Serb riots in Zagreb, in which barricades were raised and Serb-owned properties were attacked. Serbs of Zagreb eventually distanced themselves from the opinions published in the article.

World War I