History of Columbia University on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

The history of

Although the

Although the

:''Includes the administrations of Samuel Johnson (1754–1763) and

:''Includes the administrations of Samuel Johnson (1754–1763) and  In 1763, Dr. Johnson was succeeded in the presidency by

In 1763, Dr. Johnson was succeeded in the presidency by

King's college had been in a state of abeyance for eight years by the time the war ended, with many of the members of the college's Board of Governors either absent or killed during the revolution. The college turned to the

King's college had been in a state of abeyance for eight years by the time the war ended, with many of the members of the college's Board of Governors either absent or killed during the revolution. The college turned to the

On May 21, 1787,

On May 21, 1787,

In 1896, the trustees officially authorized the use of yet another new name, Columbia University, and today the institution is officially known as "Columbia University in the City of New York." Additionally, the engineering school was renamed the "School of Mines, Engineering and Chemistry." At the same time, university president

In 1896, the trustees officially authorized the use of yet another new name, Columbia University, and today the institution is officially known as "Columbia University in the City of New York." Additionally, the engineering school was renamed the "School of Mines, Engineering and Chemistry." At the same time, university president  In 1893 the

In 1893 the

Columbia University website

{{Columbia University Universities and colleges in Manhattan

The history of

The history of Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

began before it was founded in 1754 in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

as King's College, by royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

of King George II of Great Britain

, house = Hanover

, religion = Protestant

, father = George I of Great Britain

, mother = Sophia Dorothea of Celle

, birth_date = 30 October / 9 November 1683

, birth_place = Herrenhausen Palace,Cannon. or Leine ...

. It is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. state ...

, and the fifth oldest in the United States.

Founding of King's College

The period leading up to the school's founding was marked by controversy, with various groups competing to determine its location and religious affiliation. Advocates of New York City met with success on the first point, while theChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

prevailed on the latter. However, all constituencies agreed to commit themselves to principles of religious liberty in establishing the policies of the College.

City of New York

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

had come under the control of the English in 1674, no serious discussions as to the founding of a university began until the early eighteenth-century. This delay is often attributed to the multitude of languages and religions practiced in the province, which made the founding of a seat of learning difficult. Colleges during the colonial period were regarded as a religious, no less a scientific and literary institution. The large gap between the founding of New York province and the opening of its first college stands in contrast to institutions such as Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, which was created only six years after the founding of Boston, Massachusetts, a colony with a more homogenous Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

population. Discussions regarding the founding of a college in the Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the U ...

began as early as 1704, when Colonel Lewis Morris wrote to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Societi ...

, the missionary arm of the Church of England, persuading the society that New York City was an ideal community in which to establish a college. In 1686 Governor of New York Thomas Dongan, 2nd Earl of Limerick

Thomas Dongan, (pronounced "Dungan") 2nd Earl of Limerick (1634 – 14 December 1715), was a member of the Irish Parliament, Royalist military officer during the English Civil War, and Governor of the Province of New York. He is noted for hav ...

unsuccessfully petitioned James II of England

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious Re ...

for a grant of the Duke's, known as King's Farm, to maintain his Jesuit College, which eventually failed. Morris had initially designed the college to be built upon this land, which was vested to Trinity Church by Queen Anne and Lord Cornburry in 1705, and nothing came of the proposition to form a college in the province until almost fifty years later. The founding of Harvard in 1636 and Yale in 1701 had set no competitive juices flowing among New York's merchants. But the announcement in the summer of 1745 that New Jersey, which had only seven years before secured a government separate from New York's and was still considered by New Yorkers to be within its cultural catch basin, was about to found the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, demanded an immediate response.

In 1746 an act was passed by the general assembly of New York to raise a sum of £2,250 by public lottery for the foundation of a new college, despite the fact that the University had neither a founding denomination nor a location for its first campus. In 1751, the assembly appointed a commission of ten New York residents, seven of whom were Church of England members, to direct the funds accrued by the state lottery towards the foundation of a college. Funds were also provided by many of the wealthiest individuals of the period, including numerous slave owners

The following is a list of slave owners, for which there is a consensus of historical evidence of slave ownership, in alphabetical order by last name.

A

* Adelicia Acklen (1817–1887), at one time the wealthiest woman in Tennessee, she inh ...

and slave traders. In March of the following year, the vestrymen of Trinity Church offered the commission the six-northernmost acres of its property for the foundation of the college, which settled the problem of the college's first campus; however, considerable outcry from William Livingston

William Livingston (November 30, 1723July 25, 1790) was an American politician who served as the first governor of New Jersey (1776–1790) during the American Revolutionary War. As a New Jersey representative in the Continental Congress, he sig ...

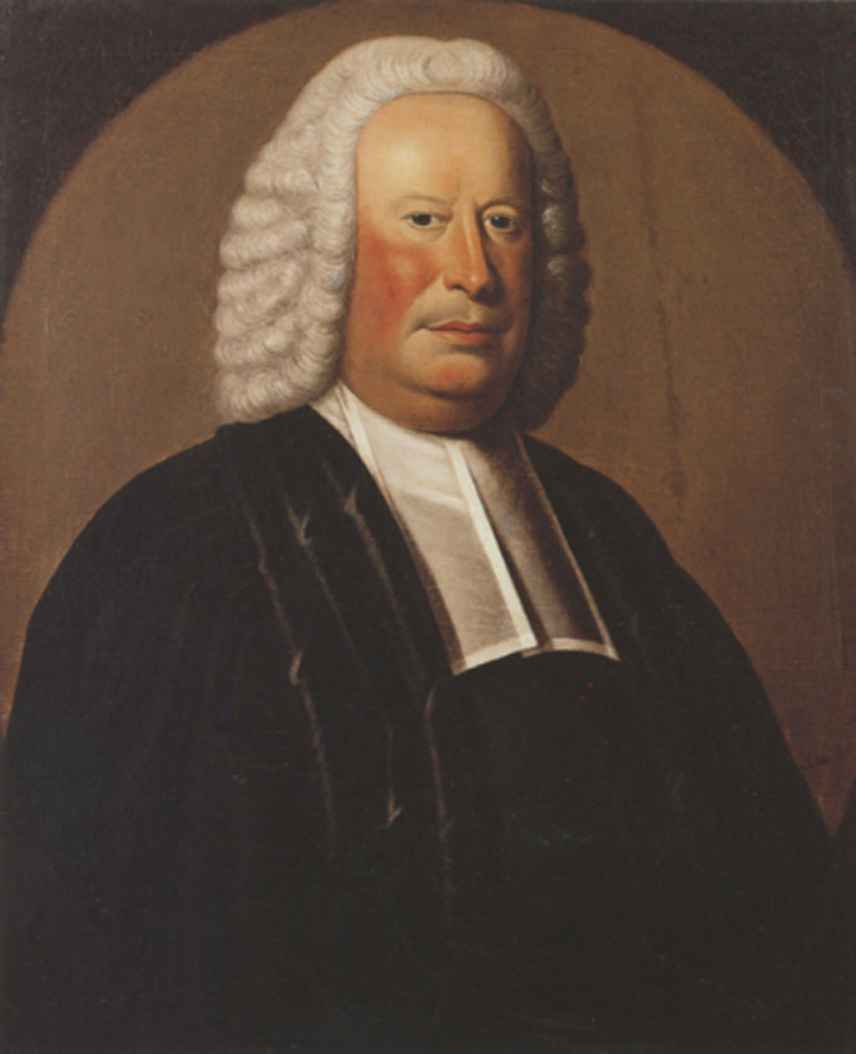

and other members of the commission who believed that the college should be nonsectarian caused further delay in the college's founding. Despite Livingston's objections, the commission voted to accept the lands from Trinity Church on the condition that the college's affiliation be Church of England. The commission chose as the college's first president Dr. Samuel Johnson, a preeminent scholar who had received his doctorate from The University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

, and had been sought in similar capacity to preside over the College of Philadelphia, now The University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

.

King's College (1754–1784)

:''Includes the administrations of Samuel Johnson (1754–1763) and

:''Includes the administrations of Samuel Johnson (1754–1763) and Myles Cooper

Myles Cooper (1735 – May 1, 1785) was a figure in colonial New York. An Anglican priest, he served as the President of King's College (predecessor of today's Columbia University) from 1763 to 1775, and was a public opponent of the American Re ...

(1763–1785)

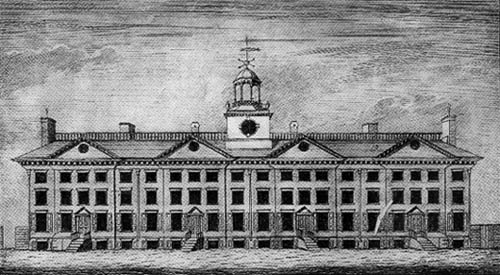

Classes were initially held in July 1754, the delay stemming from the inability of the college to secure adequate faculty. Dr. Johnson was the only instructor of the college's first class, which consisted of a mere eight students. Instruction was held in a new schoolhouse adjoining Trinity Church, located on what is now lower Broadway in Manhattan. The college was officially founded on October 31, 1754, as King's College by royal charter of King George II, making it the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York and the fifth oldest in the United States. On June 3 of the following year, the Governors of the College adopted a design prepared by Dr. Johnson for the seal of King's College, which continues to be that of Columbia College with the alteration in name.

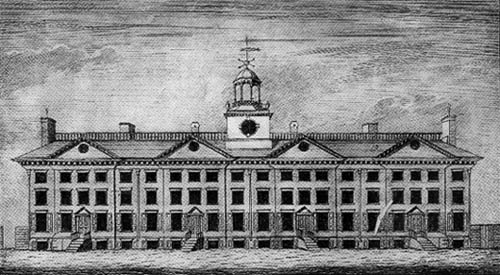

In 1760, King's College moved to its own building at Park Place, near the present City Hall, and in 1767 it established the first American medical school to grant the M.D.

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degree. ...

degree.

Controversy surrounded the founding of the new college in New York, as it was a thoroughly Church of England institution dominated by the influence of Crown officials in its governing body, such as the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Secretary of State for the Colonies. Fears of the establishment of a Church of England episcopacy

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

and of Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

influence in America through King's College were underpinned by its vast wealth, far surpassing all other colonial colleges of the period.

In 1763, Dr. Johnson was succeeded in the presidency by

In 1763, Dr. Johnson was succeeded in the presidency by Myles Cooper

Myles Cooper (1735 – May 1, 1785) was a figure in colonial New York. An Anglican priest, he served as the President of King's College (predecessor of today's Columbia University) from 1763 to 1775, and was a public opponent of the American Re ...

, a graduate of The Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassical architecture, ...

, and an ardent Tory. In the political controversies which preceded The American Revolution, his chief opponent in discussions at the College was an undergraduate of the class of 1777, Alexander Hamilton. On one occasion, a mob came to the College, bent on doing violence to the president, but Hamilton held their attention with a speech, giving Cooper enough time to escape. The next year the Revolutionary War broke out and the College was turned into a military hospital and barracks.

The American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

and the subsequent war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

were catastrophic for the operation of King's College. It suspended instruction for eight years beginning in 1776 with the arrival of the Continental Army in the spring of that year. The suspension continued through the military occupation of New York City by British troops until their departure in 1783. The college's library was looted and its sole building requisitioned for use as a military hospital first by American and then British forces. Although the college had been considered a bastion of Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

sentiment, it nevertheless produced many key leaders of the Revolutionary generation — individuals later instrumental in the college's revival. Among the earliest students and trustees of King's College were five "founding fathers" of the United States: John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

, who negotiated the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

between the United States and the Kingdom of Great Britain, ending the Revolutionary War, and who later became the first Chief Justice of the United States; Alexander Hamilton, military aide to General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, author of most of the '' Federalist Papers'', and the first Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

; Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to th ...

, the author of the final draft of the United States Constitution; Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

, a member of the Committee of Five

''

The Committee of Five of the Second Continental Congress was a group of five members who drafted and presented to the full Congress in Pennsylvania State House what would become the United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776. Thi ...

, that drafted the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

; and Egbert Benson

Egbert Benson (June 21, 1746 – August 24, 1833) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician, who represented New York State in the Continental Congress, Annapolis Convention, and United States House of Representatives. He served as a membe ...

who represented New York in the Continental Congress and the Annapolis Convention, and who was a ratifier of the United States Constitution.

Post Revolutionary War Recovery (1784–1800)

Columbia College under the Regents

King's college had been in a state of abeyance for eight years by the time the war ended, with many of the members of the college's Board of Governors either absent or killed during the revolution. The college turned to the

King's college had been in a state of abeyance for eight years by the time the war ended, with many of the members of the college's Board of Governors either absent or killed during the revolution. The college turned to the State of New York

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. state ...

in order to restore its vitality, promising to make whatever changes to the schools charter the state might demand. The Legislature agreed to assist the college, and on May 1, 1784, it passed "an Act for granting certain privileges to the College heretofore called King's College." The Act created a Board of Regents

In the United States, a board often governs institutions of higher education, including private universities, state universities, and community colleges. In each US state, such boards may govern either the state university system, individual c ...

to oversee the resuscitation of King's, giving them the power to hire a college president and appoint professors, but prohibiting the College from administering any "religious test-oath" to its faculty. Finally, in an effort to demonstrate its support for the new Republic, the Legislature stipulated that "the College within the City of New York heretofore called King's College be forever hereafter called and known by the name of Columbia College."

On May 5, 1784, the Regents held their first meeting, instructing Treasurer Brockholst Livingston and Secretary Robert Harpur (who was Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at King's) to recover the books, records and any other assets that had been dispersed during the war, and appointing a committee to supervise the repairs of the college building. In addition, the Regents moved quickly to rebuild Columbia's faculty, appointing William Cochran instructor of Greek and Latin. In the summer of 1784, after the legislature passed the act restoring the college, Major General James Clinton

Major General James Clinton (August 9, 1736 – September 22, 1812) was an American Revolutionary War officer who, with John Sullivan, led in 1779 the Sullivan Expedition in what is now western New York to attack British-allied Seneca and ...

, a hero of the revolutionary war, brought his son DeWitt Clinton to New York on his way to enroll him as a student at the College of New Jersey. When James Duane

James Duane (February 6, 1733 – February 1, 1797) was an American Founding Father, attorney, jurist, and American Revolutionary leader from New York. He served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress, Second Continental Congress an ...

, the Mayor of New York and a member of the Regents, heard that the younger Clinton was leaving the state for his education, he pleaded with Cochran to offer him admission to the reconstituted Columbia. Cochran agreed — partly because DeWitt's uncle, George Clinton, the Governor of New York, had recently been elected Chancellor of the College by the Regents — and DeWitt Clinton became one of nine students admitted to Columbia in the year 1784.

During the period under the Regents, many efforts were made to put the University on respectable footing, resolving to organize the college into the four faculties of Arts, Divinity, Medicine, and Law. A number of different professorships were created within each faculty, while the college remained under the supervision of the Regents. The staff of the entire university - which included numerous aforementioned professors, a president, a secretary, and a librarian – operated under the yearly budget of £1,200. During this period no president was able to be appointed due to the college's inadequate funds, which rendered it unable to offer a salary as would induce a suitable person to accept the office. Instead, the duties of the president's office were held by the schools various professors, which led to discord between the school's faculty members. The Regents finally became aware of the college's defective constitution in February 1787 and appointed a revision committee, which was headed by John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

and Alexander Hamilton. In April of that same year, a new charter was adopted for the college, still in use today, granting power to a private board of twenty-four Trustees.

Columbia College

:''Includes the administration ofWilliam Samuel Johnson

William Samuel Johnson (October 7, 1727 – November 14, 1819) was an American Founding Father and statesman. Before the Revolutionary War, he served as a militia lieutenant before being relieved following his rejection of his election to the Fi ...

(1787–1800)

On May 21, 1787,

On May 21, 1787, William Samuel Johnson

William Samuel Johnson (October 7, 1727 – November 14, 1819) was an American Founding Father and statesman. Before the Revolutionary War, he served as a militia lieutenant before being relieved following his rejection of his election to the Fi ...

, the son of Dr. Samuel Johnson, was unanimously elected President of Columbia College. Prior to serving at the University, Johnson had participated in the First Continental Congress and been chosen as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. For a period in the 1790s, with New York City as the federal and state capital and the country under successive Federalist governments, a revived Columbia thrived under the auspices of Federalists such as Hamilton and Jay. Both President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and Vice President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

attended the College's commencement on May 6, 1789, as a tribute of honor to the many alumni of the school that had been instrumental in bringing about the independence of the fledgling United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

.

During the period of Johnson's presidency, the College's campus began to expand, and in 1792 a new library extension was built to accommodate the College's growing library with the help of a grant from the Legislature of New York State. In December 1793, the Professorship of Law was filled by the election of James Kent, who gave the first instruction of law at any American University and was a forerunner to the University's Law School. On July 16, 1800, the seventy-four-year-old Dr. Johnson resigned his presidency of the College. In 1801, the Board of Trustees appointed Charles Henry Wharton

Charles Henry Wharton (June 5, 1748 – July 22, 1833), who grew up Catholic and became a Catholic priest, converted to Protestantism and became one of the leading Episcopal clergyman of the early United States, as well as briefly serving as p ...

as Dr. Johnson's successor. Wharton was to assume the office of president at the August commencement ceremonies, but he did not appear for them, and resigned in the fall.

College stagnation (1800–1857)

Despite the College's liberal acceptance of various religious and ethnic groups, during the period from 1785–1849 the institutional life of the college was a continuous struggle for existence, owing to inadequate means and lack of financial support. The curriculum of the college during the beginning of the 19th century was mostly focused on study of the classics. As a result, the major prerequisite for admission into the College was familiarity with Greek and Latin and a basic understanding of mathematics. In 1810, following the advice of a committee put together by members of the school, the College greatly tightened its admission standards; nonetheless, admission of qualified students increased, with 135 students matriculating in 1810. In the preceding decade, the average size of the graduating class had been seventeen. Because the school had no athletic program, student life during this period was mainly focused around literary groups such as thePhilolexian Society

The Philolexian Society of Columbia University is one of the oldest college literary and debate societies in the United States, and the oldest student group at Columbia. Founded in 1802, the Society aims to "improve its members in Oratory, Compo ...

, which was founded in 1802. In 1811, the College's new president William Harris William or Will or Willie Harris may refer to:

Politicians and political activists

*William Harris (born 1504) (1504–?), MP for Newport, Cornwall

*William Harris (died 1556), MP for Maldon (UK Parliament constituency), Maldon

*William Harris (MP ...

presided over what became known as the ""Riotous Commencement" in which students violently protested the faculty's decision not to confer a degree upon John Stevenson, who had inserted objectionable words into his commencement speech.

The main building which housed the College was decayed and unsightly in appearance; however, the funds of the College were augmented somewhat by the growing importance of its investments in real estate, although the true value of some of these acquisitions would not come to light until over a century later. For example, in 1814 the New York Legislature responded to the College's appeal for financial assistance by giving the school the Elgin Botanic Garden, a twenty-acre tract of land that had been privately developed as the nation's first botanical garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

by physician David Hosack

David Hosack (August 31, 1769 – December 22, 1835) was a noted American physician, botanist, and educator. He remains widely known as the doctor who tended to the fatal injuries of Alexander Hamilton after his duel with Aaron Burr in July 1 ...

, but which Hosack had closed and resold to the state at a loss. The site, which had been outside of the city limits in 1801, was leased by Columbia to John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist, and the only son of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller.

He was involved in the development of the vast office complex in M ...

in the 1920s for the construction of Rockefeller Center

The construction of the Rockefeller Center complex in New York City was conceived as an urban renewal project in the late 1920s, spearheaded by John D. Rockefeller Jr. to help revitalize Midtown Manhattan. Rockefeller Center is on one of Colum ...

. It was still owned by Columbia until 1985, when it was sold for $400 million.

In November 1813, the College agreed to combine its medical school with The College of Physicians and Surgeons, a new school created by the Regents of New York, forming Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) is the graduate medical school of Columbia University, located at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan. Founded ...

. During the 1820s, the College renovated its campus and continued to seek grants from the state while it slowly expanded the scope of its academic catalog, adding Italian courses in 1825.

The College's enrollment, structure, and academics stagnated for the remaining forty years, with many of the college presidents doing little to change the way that the College functioned. Adding to the woes of the College during this period, in 1831 the school began to face direct competition in the form of the University of the City of New York, which was later to become New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

. This new university had a more utilitarian curriculum, which stood in contrast to Columbia's focus on ancient literature. As a demonstration of NYU's popularity, by the second year of its operation it had 158 students, whereas Columbia College, eighty years after its founding, only had 120. Trustees of Columbia attempted to block the founding of NYU, issuing pamphlets to dissuade the Legislature from opening another university while Columbia continued to struggle financially. By July, 1854 the ''Christian Examiner'' of Boston, in an article entitled "The Recent Difficulties at Columbia College", noted that the school was "good in classics" yet "weak in sciences", and had "very few distinguished graduates".

When Charles King became Columbia's president in November 1849, the College was in large amounts of debt, having exceeded their annual expenditure by about $2200 for the past fifteen years. On his formal inauguration, King spoke on the duties and responsibilities of the university staff, and espoused the virtues of copying the English university system. By this time, the College's investments in New York real estate, particularly the Botanical Garden, became a primary source of steady income for the school, mainly owing to the city's rapidly increasing population.

Expansion and Madison Avenue (1857–1896)

In 1857, the College moved from Park Place to a primarily Gothic Revival campus on 49th Street and Madison Avenue, at the former site of the New York Institute for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, where it remained for the next fifty years. The transition to the new campus coincided with a new outlook for the college; during the commencement of that year, College President Charles King proclaimed Columbia "a university". During the last half of the nineteenth century, under the leadership of President F.A.P. Barnard, the institution rapidly assumed the shape of a true modern university.Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (Columbia Law or CLS) is the law school of Columbia University, a private Ivy League university in New York City. Columbia Law is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious law schools in the world and has always ranked i ...

was founded in 1858, and in 1864 the School of Mines

A school of mines (or mining school) is an engineering school, often established in the 18th and 19th centuries, that originally focused on mining engineering and applied science. Most have been integrated within larger constructs such as mine ...

, the country's first such institution and the precursor to today's Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science

The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (popularly known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering; previously known as Columbia School of Mines) is the engineering and applied science school of Columbia University. It was founded as th ...

, was established. Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

for women, established by the eponymous Columbia president, was established in 1889; the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) is the graduate medical school of Columbia University, located at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan. Founded ...

came under the aegis of the University in 1891, followed by Teachers College, Columbia University

Teachers College, Columbia University (TC), is the graduate school of education, health, and psychology of Columbia University, a private research university in New York City. Founded in 1887, it has served as one of the official faculties and ...

in 1893. The Graduate Faculties in Political Science, Philosophy, and Pure Science awarded its first PhD in 1875. This period also witnessed the inauguration of Columbia's participation in intercollegiate sports, with the creation of the baseball team in 1867, the organization of the football team in 1870, and the creation of a crew

A crew is a body or a class of people who work at a common activity, generally in a structured or hierarchical organization. A location in which a crew works is called a crewyard or a workyard. The word has nautical resonances: the tasks involved ...

team by 1873. The first intercollegiate Columbia football game was a 6–3 loss to Rutgers

Rutgers University (; RU), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a public land-grant research university consisting of four campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's College, and w ...

. The '' Columbia Daily Spectator'' began publication during this period as well, in 1877.

Morningside Heights (1896–Present)

In 1896, the trustees officially authorized the use of yet another new name, Columbia University, and today the institution is officially known as "Columbia University in the City of New York." Additionally, the engineering school was renamed the "School of Mines, Engineering and Chemistry." At the same time, university president

In 1896, the trustees officially authorized the use of yet another new name, Columbia University, and today the institution is officially known as "Columbia University in the City of New York." Additionally, the engineering school was renamed the "School of Mines, Engineering and Chemistry." At the same time, university president Seth Low

Seth Low (January 18, 1850 – September 17, 1916) was an American educator and political figure who served as the mayor of Brooklyn from 1881 to 1885, the president of Columbia University from 1890 to 1901, a diplomatic representative of t ...

moved the campus again, from 49th Street to its present location, a more spacious (and, at the time, more rural) campus in the developing neighborhood of Morningside Heights. The site was formerly occupied by the Bloomingdale Lunatic Asylum. One of the asylum's buildings, the warden's cottage (later known as East Hall and Buell Hall), still stands today.

The building often depicted as emblematic of Columbia is the centerpiece of the Morningside Heights campus, Low Memorial Library

The Low Memorial Library (nicknamed Low) is a building at the center of Columbia University's Morningside Heights campus in Manhattan, New York City, United States. The building, located near 116th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenu ...

. Constructed in 1895, the building is still referred to as "Low Library" although it has not functioned as a library since 1934. It currently houses the offices of the President, Provost, the Visitor's Center, and the Trustees' Room and Columbia Security. Patterned loosely on the Classical Pantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone S ...

, it is surmounted by the largest all-granite dome in the United States.

Under the leadership of Low's successor, Nicholas Murray Butler

Nicholas Murray Butler () was an American philosopher, diplomat, and educator. Butler was president of Columbia University, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, and the deceased Ja ...

, Columbia rapidly became the nation's major institution for research, setting the "multiversity" model that later universities would adopt. On the Morningside Heights campus, Columbia centralized on a single campus the College, the School of Law, the Graduate Faculties, the School of Mines (predecessor of the Engineering School), and the College of Physicians & Surgeons. Butler went on to serve as president of Columbia for over four decades and became a giant in American public life (as one-time vice presidential candidate and a Nobel Laureate). His introduction of "downtown" business practices in university administration led to innovations in internal reforms such as the centralization of academic affairs, the direct appointment of registrars, deans, provosts, and secretaries, as well as the formation of a professionalized university bureaucracy, unprecedented among American universities at the time.

In 1893 the

In 1893 the Columbia University Press

Columbia University Press is a university press based in New York City, and affiliated with Columbia University. It is currently directed by Jennifer Crewe (2014–present) and publishes titles in the humanities and sciences, including the fiel ...

was founded to "promote the study of economic, historical, literary, scientific and other subjects; and to promote and encourage the publication of literary works embodying original research in such subjects." Among its publications are ''The Columbia Encyclopedia

The ''Columbia Encyclopedia'' is a one-volume encyclopedia produced by Columbia University Press and, in the last edition, sold by the Gale Group. First published in 1935, and continuing its relationship with Columbia University, the encyclopedi ...

'', first published in 1935, and ''The Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer of the World'', first published in 1952. In 1902, New York newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer

Joseph Pulitzer ( ; born Pulitzer József, ; April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911) was a Hungarian-American politician and newspaper publisher of the '' St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' and the ''New York World''. He became a leading national figure in ...

donated a substantial sum to the University for the founding of a school to teach journalism. The result was the 1912 opening of the Graduate School of Journalism—the only journalism school in the Ivy League. Columbia does not, however, offer an undergraduate degree in journalism. The school is the administrator of the Pulitzer Prize and the duPont-Columbia Award in broadcast journalism.

In 1904 Columbia organized adult education classes into a formal program called Extension Teaching (later renamed University Extension). Courses in Extension Teaching eventually give rise to the Columbia Writing Program, the Columbia Business School, and the School of Dentistry.

In 1928, Seth Low

Seth Low (January 18, 1850 – September 17, 1916) was an American educator and political figure who served as the mayor of Brooklyn from 1881 to 1885, the president of Columbia University from 1890 to 1901, a diplomatic representative of t ...

Junior College was established by Columbia University in order to mitigate the number of Jewish applicants to Columbia College. The college was closed in 1938 due to the adverse effects of the Great Depression and its students were subsequently taught at Mornington Heights, although they did not belong to any college but to the university at large.

There was an evening school called University Extension, which taught night classes, for a fee, to anyone willing to attend. In 1947, the program was reorganized as an undergraduate college and designated the School of General Studies

The School of General Studies, Columbia University (GS) is a liberal arts college and one of the undergraduate colleges of Columbia University, situated on the university's main campus in Morningside Heights, New York City. GS is known primarily ...

in response to the return of GIs after World War II. In 1995, the School of General Studies was again reorganized as a full-fledged liberal arts college for non-traditional students (those who have had an academic break of one year or more) and was fully integrated into Columbia's traditional undergraduate curriculum. Within the same year, the Division of Special Programs—later the School of Continuing Education, and now the School of Professional Studies—was established to reprise the former role of University Extension. While the School of Professional Studies only offered non-degree programs for lifelong learners and high school students in its earliest stages, it now offers degree programs in a diverse range of professional and inter-disciplinary fields.

By the late 1930s, a Columbia student could study with the likes of Jacques Barzun

Jacques Martin Barzun (; November 30, 1907 – October 25, 2012) was a French-American historian known for his studies of the history of ideas and cultural history. He wrote about a wide range of subjects, including baseball, mystery novels, and ...

, Paul Lazarsfeld

Paul Felix Lazarsfeld (February 13, 1901August 30, 1976) was an Austrian-American sociologist. The founder of Columbia University's Bureau of Applied Social Research, he exerted influence over the techniques and the organization of social rese ...

, Mark Van Doren

Mark Van Doren (June 13, 1894 – December 10, 1972) was an American poet, writer and critic. He was a scholar and a professor of English at Columbia University for nearly 40 years, where he inspired a generation of influential writers and thin ...

, Lionel Trilling, and I. I. Rabi. The University's graduates during this time were equally accomplished—for example, two alumni of Columbia's Law School, Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

and Harlan Fiske Stone

Harlan is a given name and a surname which may refer to:

Surname

* Bob Harlan (born 1936 Robert E. Harlan), American football executive

*Bruce Harlan (1926–1959), American Olympic diver

*Byron B. Harlan (1886–1949), American politician

* Byron ...

(who also held the position of Law School dean), served successively as Chief Justices of the United States. Dwight Eisenhower served as Columbia's president from 1948 until he became the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

in 1953.

Research into the atom by faculty members John R. Dunning, I. I. Rabi, Enrico Fermi and Polykarp Kusch

Polykarp Kusch (January 26, 1911 – March 20, 1993) was a German-born American physicist. In 1955, the Nobel Committee gave a divided Nobel Prize for Physics, with one half going to Kusch for his accurate determination that the magnetic momen ...

placed Columbia's Physics Department in the international spotlight in the 1940s after the first nuclear pile was built to start what became the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. Following the end of World War II, the School of International Affairs was founded in 1946, beginning by offering the Master of International Affairs

The Master in International Affairs (MIA), or the Master in Global Affairs (MGA), also known as Master in International relations (MIR) is a master's degree awarded by schools of international affairs.

Subject matter

Details can vary between deg ...

. To satisfy an increasing desire for skilled public service

A public service is any service intended to address specific needs pertaining to the aggregate members of a community. Public services are available to people within a government jurisdiction as provided directly through public sector agencies ...

professionals at home and abroad, the School added the Master of Public Administration degree in 1977. In 1981, the School was renamed the School of International and Public Affairs

The School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University (SIPA) is the international affairs and public policy school of Columbia University, a private Ivy League university located in Morningside Heights, Manhattan, New York City. ...

(SIPA). The School introduced an MPA in Environmental Science and Policy

Policy is a deliberate system of guidelines to guide decisions and achieve rational outcomes. A policy is a statement of intent and is implemented as a procedure or protocol. Policies are generally adopted by a governance body within an orga ...

in 2001 and, in 2004, SIPA inaugurated its first doctoral program — the interdisciplinary Ph.D. in Sustainable Development.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Columbia, Morningside Heights campus, was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program

The V-12 Navy College Training Program was designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers in the United States Navy during World War II. Between July 1, 1943, and June 30, 1946, more than 125,000 participants were enrolled in 131 colleg ...

which offered students a path to a Navy commission.

During the 1960s Columbia experienced large-scale student activism centering over the Vietnam War and the demand for greater student rights

Student rights are those rights, such as civil, constitutional, contractual and consumer rights, which regulate student rights and freedoms and allow students to make use of their educational investment. These include such things as the right to ...

. Many students, led by the Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s, and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships ...

and its President Mark Rudd protested the University's ties with the defense establishment and its controversial plans to build a gym in Morningside Park. The fervor on campus reached a climax in the spring of 1968 when hundreds of students occupied various buildings on campus. The incident forced the resignation of Columbia's then President, Grayson Kirk and the establishment of the University Senate.

Columbia College first admitted women in the fall of 1983, after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

, an all female institution affiliated with the University, to merge the two schools. Barnard College still remains affiliated with Columbia, and all Barnard graduates are issued diplomas authorized by both Columbia University and Barnard College.

During the late 20th century, the University underwent significant academic, structural, and administrative changes as it developed into a major research university. For much of the 19th century, the University consisted of decentralized and separate faculties specializing in Political Science, Philosophy, and Pure Science. In 1979, these faculties were merged into the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. In 1991, the faculties of Columbia College, the School of General Studies, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the School of the Arts, and the School of Professional Studies were merged into the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, leading to the academic integration and centralized governance of these schools. In 2010, the School of International and Public Affairs

The School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University (SIPA) is the international affairs and public policy school of Columbia University, a private Ivy League university located in Morningside Heights, Manhattan, New York City. ...

, which was previously a part of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, became an independent faculty.

In 1997, the Columbia Engineering School was renamed the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science

The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (popularly known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering; previously known as Columbia School of Mines) is the engineering and applied science school of Columbia University. It was founded as th ...

, in honor of Chinese businessman Z. Y. Fu, who gave Columbia $26 million. The school is popularly referred to as "SEAS" or simply "the engineering school."

See also

*Columbia College of Columbia University

Columbia College is the oldest undergraduate college of Columbia University, situated on the university's main campus in Morningside Heights in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded by the Church of England in 1754 as King's ...

, the oldest liberal arts undergraduate college at Columbia University, New York

* '' Columbia Daily Spectator'', a student newspaper at Columbia University, New York

* Columbia Journal, the graduate writing program's student-founded, student-run literary journal Columbia University School of the Arts

* ''Columbia Journalism Review

The ''Columbia Journalism Review'' (''CJR'') is a biannual magazine for professional journalists that has been published by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism since 1961. Its contents include news and media industry trends, an ...

'', a bimonthly journal published by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism

* Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (Columbia Law or CLS) is the law school of Columbia University, a private Ivy League university in New York City. Columbia Law is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious law schools in the world and has always ranked i ...

:* '' Columbia Business Law Review'', a monthly journal published by students at Columbia Law School

* The Pulitzer Prize

* The School at Columbia University, New York City

* Teachers College

A normal school or normal college is an institution created to train teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. In the 19th century in the United States, instruction in normal schools was at the high school level, turni ...

, Columbia University's Graduate School of Education

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * *External links

Columbia University website

{{Columbia University Universities and colleges in Manhattan

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...