History of Buddhism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Buddhism spans from the 5th century BCE to the present.

The history of Buddhism spans from the 5th century BCE to the present.

After the death of the Buddha, the Buddhist

After the death of the Buddha, the Buddhist

File:Buddha Sakyamuni on the Rummindei pillar of Ashoka.jpg, The words " Bu-dhe" (𑀩𑀼𑀥𑁂, the

During the reign of the

During the reign of the

Sri Lankan chronicles like the '' Dipavamsa'' state that Ashoka's son Mahinda brought Buddhism to the island during the 2nd century BCE. In addition, Ashoka's daughter, Saṅghamitta also established the

Sri Lankan chronicles like the '' Dipavamsa'' state that Ashoka's son Mahinda brought Buddhism to the island during the 2nd century BCE. In addition, Ashoka's daughter, Saṅghamitta also established the

The Buddhist movement that became known as Mahayana (Great Vehicle) and also the Bodhisattvayana, began sometime between 150 BCE and 100 CE, drawing on both Mahasamghika and

The Buddhist movement that became known as Mahayana (Great Vehicle) and also the Bodhisattvayana, began sometime between 150 BCE and 100 CE, drawing on both Mahasamghika and

The Shunga dynasty (185–73 BCE) was established about 50 years after Ashoka's death. After assassinating King

The Shunga dynasty (185–73 BCE) was established about 50 years after Ashoka's death. After assassinating King

The

The

The

The  After the fall of the Kushans, small kingdoms ruled the Gandharan region, and later the Hephthalite White Huns conquered the area (circa 440s–670). Under the Hephthalites, Gandharan Buddhism continued to thrive in cities like

After the fall of the Kushans, small kingdoms ruled the Gandharan region, and later the Hephthalite White Huns conquered the area (circa 440s–670). Under the Hephthalites, Gandharan Buddhism continued to thrive in cities like

Central Asians played a key role in the transmission of Buddhism to China The first translators of Buddhists scriptures into Chinese were Iranians, including the

Central Asians played a key role in the transmission of Buddhism to China The first translators of Buddhists scriptures into Chinese were Iranians, including the

Nalanda Buddhist University Ruins, which flourished from 427 to 1197 CE, Nalanda, Bihar.jpg, Ruins of the Buddhist

Buddhism continued to flourish in India during the

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

arose in Ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by m ...

, in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

, and is based on the teachings of the ascetic Siddhārtha Gautama

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

. The religion evolved as it spread from the northeastern region of the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

throughout Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

, East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

, and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

. At one time or another, it influenced most of Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

.

The history of Buddhism is also characterized by the development of numerous movements, schisms, and philosophical schools, among them the Theravāda

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

, Mahāyāna

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhism, Buddhist traditions, Buddhist texts#Mahāyāna texts, texts, Buddhist philosophy, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BC ...

and Vajrayāna

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

traditions, with contrasting periods of expansion and retreat.

Shakyamuni Buddha (5th cent. BCE)

Siddhārtha Gautama

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

(5th cent. BCE) was the historical founder of Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

. The early sources state he was born in the small Shakya

Shakya (Pali, Pāḷi: ; sa, शाक्य, translit=Śākya) was an ancient eastern Sub-Himalayan Range, sub-Himalayan ethnicity and clan of north-eastern region of the Indian subcontinent, whose existence is attested during the Iron Age i ...

(Pali: Sakya) Republic, which was part of the Kosala

The Kingdom of Kosala (Sanskrit: ) was an ancient Indian kingdom with a rich culture, corresponding to the area within the region of Awadh in present-day Uttar Pradesh to Western Odisha. It emerged as a janapada, small state during the late Ve ...

realm of ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by m ...

, now in modern-day Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

.Harvey, 2012, p. 14. He is thus also known as the ''Shakyamuni'' (literally: "The sage of the Shakya clan").

The Early Buddhist Texts

Early Buddhist texts (EBTs), early Buddhist literature or early Buddhist discourses are parallel texts shared by the early Buddhist schools. The most widely studied EBT material are the first four Pali Nikayas, as well as the corresponding Chines ...

contain no continuous life of the Buddha, only later after 200 BCE were various "biographies" with much mythological embellishment written. All texts agree however that Gautama renounced the householder life and lived as a sramana ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

for some time studying under various teachers, before attaining nirvana

( , , ; sa, निर्वाण} ''nirvāṇa'' ; Pali: ''nibbāna''; Prakrit: ''ṇivvāṇa''; literally, "blown out", as in an oil lampRichard Gombrich, ''Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benāres to Modern Colombo.' ...

(extinguishment) and bodhi

The English term enlightenment is the Western translation of various Buddhist terms, most notably bodhi and vimutti. The abstract noun ''bodhi'' (; Sanskrit: बोधि; Pali: ''bodhi''), means the knowledge or wisdom, or awakened intellect ...

(awakening) through meditation.

For the remaining 45 years of his life, he traveled the Gangetic Plain

The Indo-Gangetic Plain, also known as the North Indian River Plain, is a fertile plain encompassing northern regions of the Indian subcontinent, including most of northern and eastern India, around half of Pakistan, virtually all of Bangla ...

of north-central India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

(the region of the Ganges/Ganga river and its tributaries), teaching his doctrine to a diverse range of people from different castes

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

and initiating monks into his order. The Buddha sent his disciples to spread the teaching across India. He also initiated an order of nuns.Harvey, 2012, p. 24. He urged his disciples to teach in the local language or dialects. He spent a lot of his time near the cities of Sāvatthī, Rājagaha and Vesālī (Skt. Śrāvastī, Rājagrha, Vāiśalī). By the time of his death at 80, he had thousands of followers.

Early Buddhism

After the death of the Buddha, the Buddhist

After the death of the Buddha, the Buddhist sangha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

(monastic community) remained centered on the Ganges valley, spreading gradually from its ancient heartland. The canonical sources record various councils, where the monastic Sangha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

recited and organized the orally transmitted collections of the Buddha's teachings and settled certain disciplinary problems within the community. Modern scholarship has questioned the accuracy and historicity of these traditional accounts.

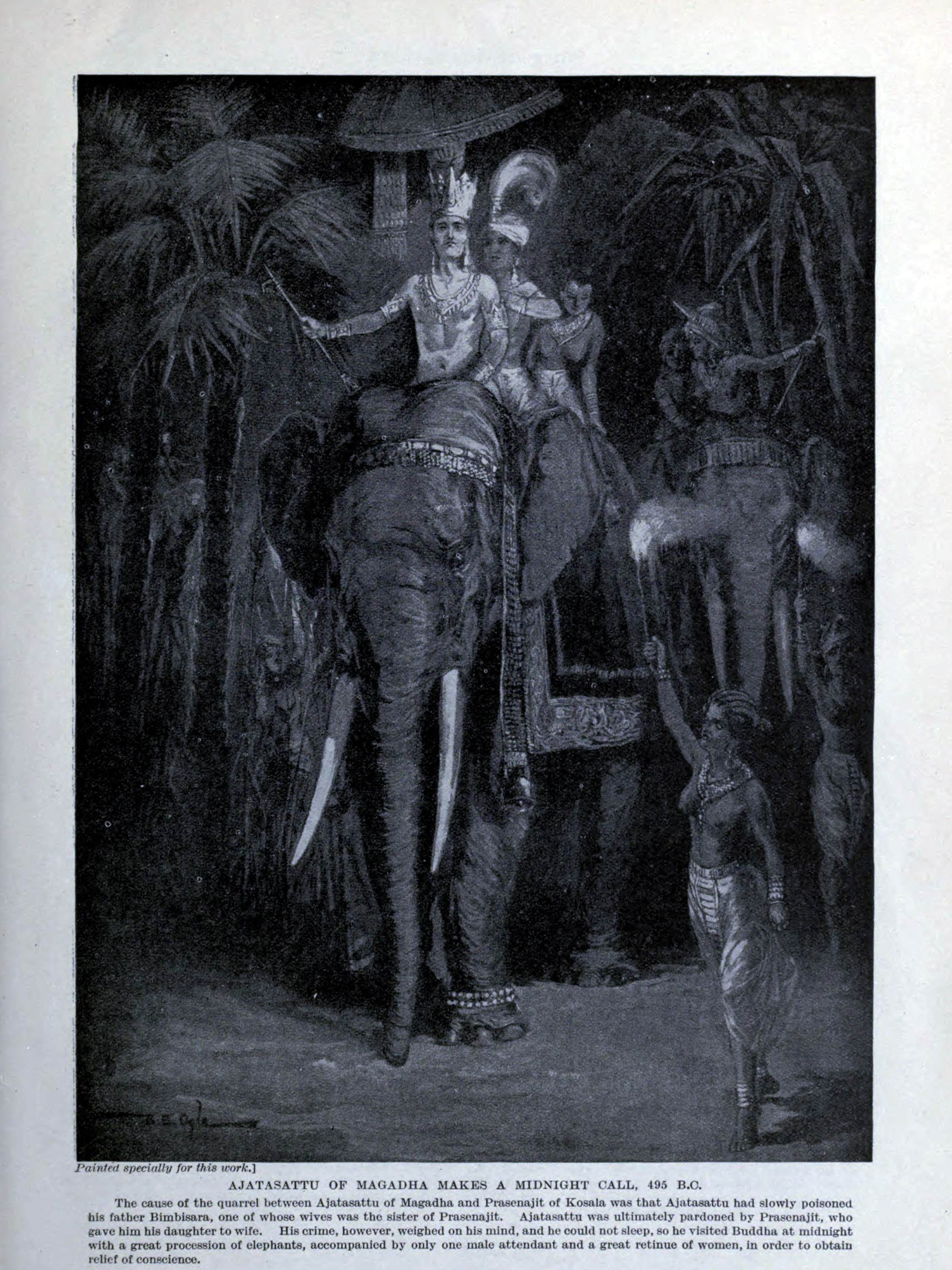

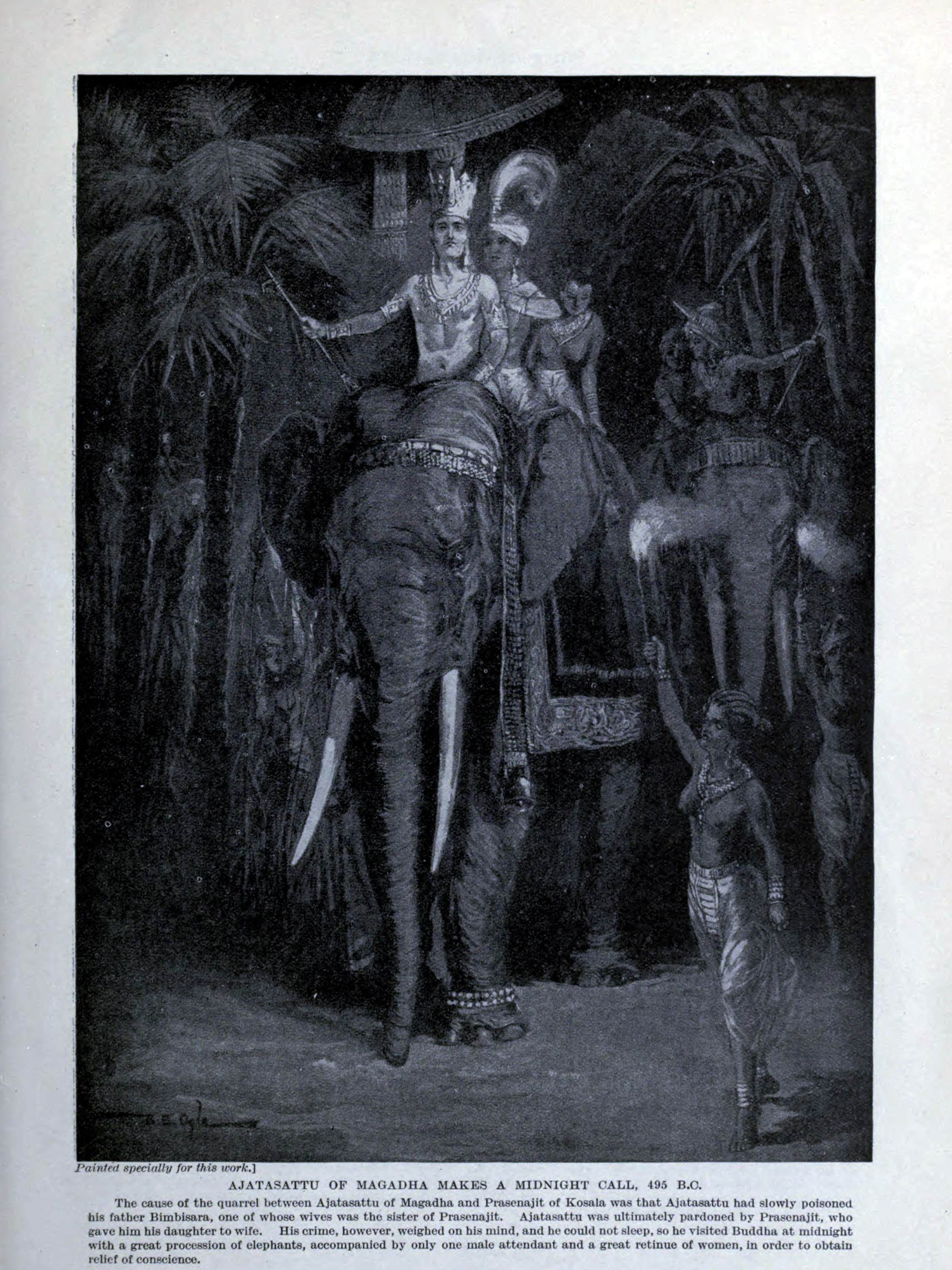

The first Buddhist council

__NOTOC__

The First Buddhist council was a gathering of senior monks of the Buddhist order convened just after Gautama Buddha's death, which according to Buddhist tradition was c. 483 BCE, though most modern scholars place it around 400 BCE. T ...

is traditionally said to have been held just after Buddha's Parinirvana

In Buddhism, ''parinirvana'' (Sanskrit: '; Pali: ') is commonly used to refer to nirvana-after-death, which occurs upon the death of someone who has attained ''nirvana'' during their lifetime. It implies a release from '' '', karma and rebirth a ...

, and presided over by Mahākāśyapa

Mahākāśyapa ( pi, Mahākassapa) was one of the principal disciples of Gautama Buddha. He is regarded in Buddhism as an enlightened disciple, being foremost in ascetic practice. Mahākāśyapa assumed leadership of the monastic community fol ...

, one of his most senior disciples, at Rājagṛha (today's Rajgir

Rajgir, meaning "The City of Kings," is a historic town in the district of Nalanda in Bihar, India. As the ancient seat and capital of the Haryanka dynasty, the Pradyota dynasty, the Brihadratha dynasty and the Mauryan Empire, as well as the d ...

) with the support of king Ajātasattu. According to Charles Prebish, almost all scholars have questioned the historicity of this first council.

Mauryan empire (322–180 BCE)

Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was ...

) and " Sa-kya- mu-nī" ( 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻, "Sage of the Shakyas

Shakya (Pāḷi: ; sa, शाक्य, translit=Śākya) was an ancient eastern sub-Himalayan ethnicity and clan of north-eastern region of the Indian subcontinent, whose existence is attested during the Iron Age. The Shakyas were organise ...

") in Brahmi script

Brahmi (; ; ISO: ''Brāhmī'') is a writing system of ancient South Asia. "Until the late nineteenth century, the script of the Aśokan (non-Kharosthi) inscriptions and its immediate derivatives was referred to by various names such as 'lath' o ...

, on Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

's Lumbini pillar inscription

The Lumbini pillar inscription, also called the Paderia inscription, is an inscription in the ancient Brahmi script, discovered in December 1896 on a pillar of Ashoka in Lumbini, Nepal by former Chief of the Nepalese Army General Khadga Shamsher J ...

(circa 250 BCE).

File:6thPillarOfAshoka.JPG, Fragment of the 6th Pillar Edict of Aśoka (238 BCE), in Brāhmī

Brahmi (; ; ISO 15919, ISO: ''Brāhmī'') is a writing system of ancient South Asia. "Until the late nineteenth century, the script of the Aśokan (non-Kharosthi) inscriptions and its immediate derivatives was referred to by various names such ...

, sandstone. British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

.

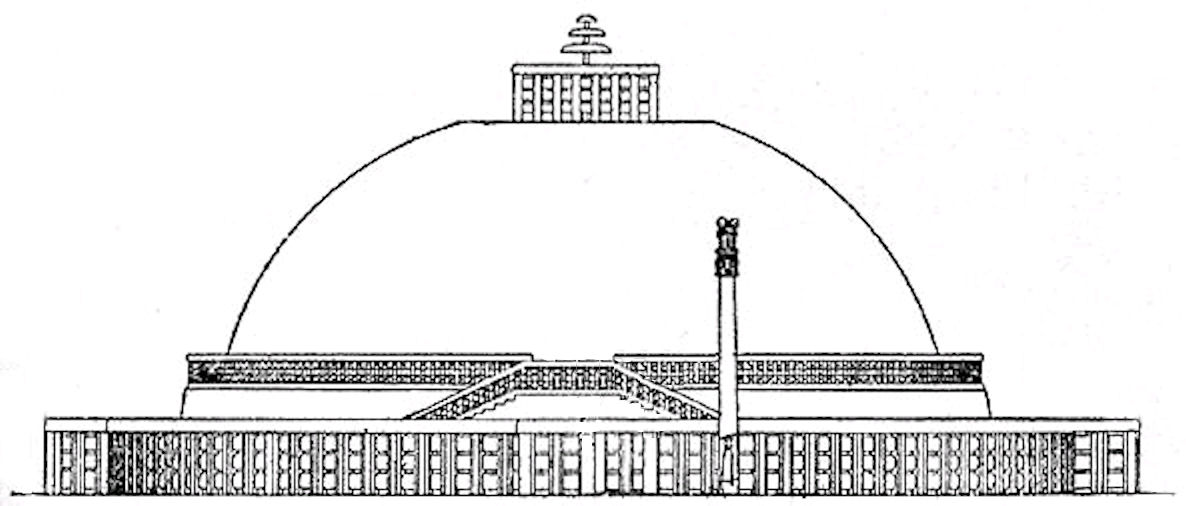

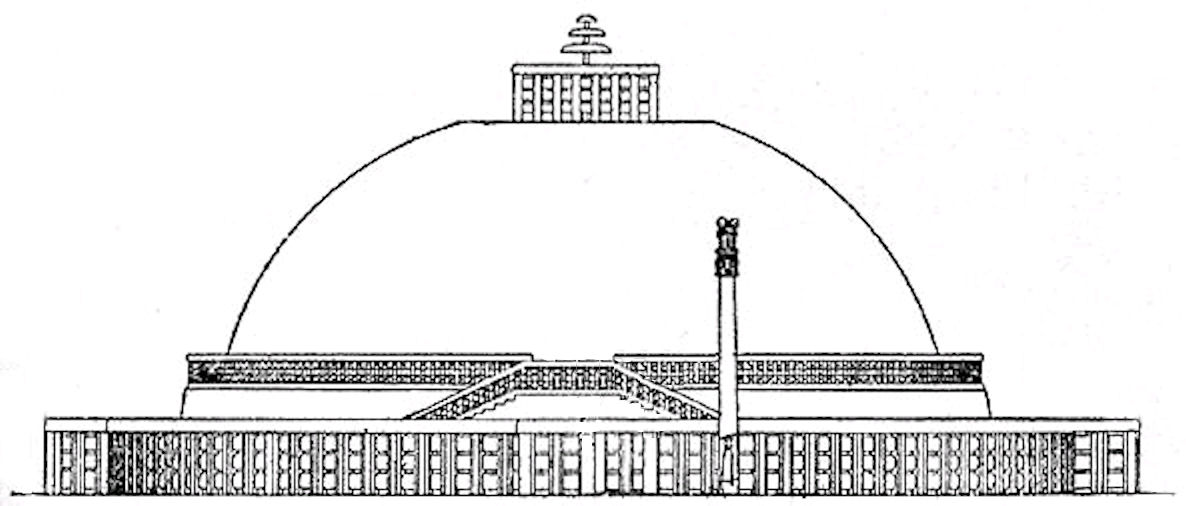

File:Sanchi Great Stupa Mauryan configuration.jpg, Approximate reconstitution of the Great Stupa with Ashoka Pillar

The pillars of Ashoka are a series of monolithic columns dispersed throughout the Indian subcontinent, erected or at least inscribed with edicts by the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka during his reign from c. 268 to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the express ...

, Sanchi

Sanchi is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the States and territories of India, State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometres from Raisen, Raisen town, dist ...

, India.

Second Buddhist council and first schism

After an initial period of unity, divisions in the sangha or monastic community led to the first schism of the sangha into two groups: the Sthavira (Elders) and Mahasamghika (Great Sangha). Most scholars agree that the schism was caused by disagreements over points ofvinaya

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon ('' Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinaya traditions remai ...

(monastic discipline). Over time, these two monastic fraternities would further divide into various Early Buddhist Schools

The early Buddhist schools are those schools into which the Buddhist monastic saṅgha split early in the history of Buddhism. The divisions were originally due to differences in Vinaya and later also due to doctrinal differences and geographic ...

.

Lamotte and Hirakawa both maintain that the first schism in the Buddhist sangha occurred during the reign of Ashoka. According to scholar Collett Cox "most scholars would agree that even though the roots of the earliest recognized groups predate Aśoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

, their actual separation did not occur until after his death." According to the Theravada tradition, the split took place at the Second Buddhist council, which took place at Vaishali, approximately one hundred years after Gautama Buddha's parinirvāṇa. While the second council probably was a historical event, traditions regarding the Second Council are confusing and ambiguous. According to the Theravada tradition the overall result was the first schism in the sangha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

, between the Sthavira nikāya and the Mahāsāṃghikas, although it is not agreed upon by all what the cause of this split was.

The Sthaviras gave birth to a large number of influential schools including the Sarvāstivāda

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (Sanskrit and Pali: 𑀲𑀩𑁆𑀩𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀺𑀯𑀸𑀤, ) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (3rd century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy ...

, the Pudgalavāda (also known as ''Vatsīputrīya''), the Dharmaguptakas and the Vibhajyavāda

Vibhajyavāda (Sanskrit; Pāli: ''Vibhajjavāda''; ) is a term applied generally to groups of early Buddhists belonging to the Sthavira Nikaya. These various groups are known to have rejected Sarvāstivāda doctrines (especially the doctrine of ...

(the Theravādins being descended from these. The Mahasamghikas meanwhile also developed their own schools and doctrines early on, which can be seen in texts like the Mahavastu, associated with the Lokottaravāda

The Lokottaravāda (Sanskrit, लोकोत्तरवाद; ) was one of the early Buddhist schools according to Mahayana doxological sources compiled by Bhāviveka, Vinitadeva and others, and was a subgroup which emerged from the Mahāsā� ...

, or ‘Transcendentalist’ school, who might be the same as the Ekavyāvahārika

The Ekavyāvahārika ( sa, एकव्यावहारिक; ) was one of the early Buddhist schools, and is thought to have separated from the Mahāsāṃghika sect during the reign of Aśoka.

History

Relationship to Mahāsāṃghika

Tāra ...

s or "One-utterancers".Harvey, 2012, p. 98. This school has been seen as foreshadowing certain Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

ideas, especially due to their view that all of Gautama Buddha's acts were "transcendental" or "supramundane", even those performed before his Buddhahood.

In the third century BCE, some Buddhists began introducing new systematized teachings called Abhidharma

The Abhidharma are ancient (third century BCE and later) Buddhist texts which contain detailed scholastic presentations of doctrinal material appearing in the Buddhist ''sutras''. It also refers to the scholastic method itself as well as the f ...

, based on previous lists or tables (''Matrka'') of main doctrinal topics.Harvey, 2012, p. 90. Unlike the Nikayas, which were prose sutras

''Sutra'' ( sa, सूत्र, translit=sūtra, translit-std=IAST, translation=string, thread)Monier Williams, ''Sanskrit English Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, Entry fo''sutra'' page 1241 in Indian literary traditions refers to an aph ...

or discourses, the Abhidharma literature consisted of systematic doctrinal exposition and often differed across the Buddhist schools who disagreed on points of doctrine. Abhidharma sought to analyze all experience into its ultimate constituents, phenomenal events or processes called ''dharmas''. These texts further contributed to the development of sectarian identities. The various splits within the monastic organization went together with the introduction and emphasis on Abhidhammic literature by some schools. This literature was specific to each school, and arguments and disputes between the schools were often based on these Abhidhammic writings. However, actual splits were originally based on disagreements on vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon ('' Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinaya traditions remai ...

(monastic discipline), though later on, by about 100 CE or earlier, they could be based on doctrinal disagreement. Pre-sectarian Buddhism, however, did not have Abhidhammic scriptures, except perhaps for a basic framework, and not all of the early schools developed an Abhidhamma literature.

Ashokan missions

During the reign of the

During the reign of the Mauryan

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until ...

Emperor Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

(268–232 BCE), Buddhism gained royal support and began to spread more widely, reaching most of the Indian subcontinent.Harvey, 2012, p. 100. After his invasion of Kalinga, Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

seems to have experienced remorse and began working to improve the lives of his subjects. Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

also built wells, rest-houses and hospitals for humans and animals. He also abolished torture, royal hunting trips and perhaps even the death penalty. Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

also supported non-Buddhist faiths like Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current ...

and Brahmanism

The historical Vedic religion (also known as Vedicism, Vedism or ancient Hinduism and subsequently Brahmanism (also spelled as Brahminism)), constituted the religious ideas and practices among some Indo-Aryan peoples of northwest Indian Subco ...

.Harvey, 2012, p. 102. Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

propagated religion by building stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumamb ...

s and pillars urging, among other things, respect of all animal life and enjoining people to follow the Dharma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for '' ...

. He has been hailed by Buddhist sources as the model for the compassionate chakravartin

A ''chakravarti'' ( sa, चक्रवर्तिन्, ''cakravartin''; pi, cakkavatti; zh, 轉輪王, ''Zhuǎnlúnwáng'', "Wheel-Turning King"; , ''Zhuǎnlún Shèngwáng'', "Wheel-Turning Sacred King"; ja, 転輪王, ''Tenrin'ō'' ...

(wheel turning monarch).

Another feature of Mauryan Buddhism was the worship and veneration of stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumamb ...

s, large mounds which contained relics (Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

: ''sarīra'') of the Buddha or other saints within.Harvey, 2012, p. 103. It was believed that the practice of devotion to these relics and stupas could bring blessings. Perhaps the best-preserved example of a Mauryan Buddhist site is the Great Stupa of Sanchi

Sanchi is a Buddhist art, Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the States and territories of India, State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometres from Raisen, Rais ...

(dating from the 3rd century BCE).

According to the plates and pillars left by Aśoka (known as the Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who reigned from 268 BCE to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the expres ...

), emissaries were sent to various countries in order to spread Buddhism, as far south as Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and as far west as the Greek kingdoms, in particular the neighboring Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era Hellenistic Greece, Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Helleni ...

, and possibly even farther to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

.

Third council

Theravadin

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

sources state that Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

convened the third Buddhist council

The Third Buddhist council was convened in about 250 BCE at Asokarama in Pataliputra, under the patronage of Emperor Ashoka.

The traditional reason for convening the Third Buddhist Council is reported to have been to rid the Sangha of corruption ...

around 250 BCE at Pataliputra (today's Patna

Patna (

), historically known as Pataliputra, is the capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Patna had a population of 2.35 million, making it the 19th largest city in India. ...

) with the elder Moggaliputtatissa. The objective of the council was to purify the Saṅgha, particularly from non-Buddhist ascetics who had been attracted by the royal patronage. Following the council, Buddhist missionaries were dispatched throughout the known world, as is recorded in some of the edicts of Ashoka.

Proselytism in the Hellenistic world

Some of theEdicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who reigned from 268 BCE to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the expres ...

describe the efforts made by him to propagate the Buddhist faith throughout the Hellenistic world, which at that time formed an uninterrupted cultural continuum from the borders of India to Greece. The edicts indicate a clear understanding of the political organization in Hellenistic territories: the names and locations of the main Greek monarchs of the time are identified, and they are claimed as recipients of Buddhist proselytism

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invol ...

: Antiochus II Theos

Antiochus II Theos ( grc-gre, Ἀντίοχος Θεός, ; 286 – July 246 BC) was a Greek king of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire who reigned from 261 to 246 BC. He succeeded his father Antiochus I Soter in the winter of 262–61 BC. He wa ...

of the Seleucid Kingdom

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the M ...

(261–246 BCE), Ptolemy II Philadelphos

; egy, Userkanaenre Meryamun Clayton (2006) p. 208

, predecessor = Ptolemy I

, successor = Ptolemy III

, horus = ''ḥwnw-ḳni'Khunuqeni''The brave youth

, nebty = ''wr-pḥtj'Urpekhti''Great of strength

, gol ...

of Egypt (285–247 BCE), Antigonus Gonatas

Antigonus II Gonatas ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Γονατᾶς, ; – 239 BC) was a Macedonian ruler who solidified the position of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedon after a long period defined by anarchy and chaos and acquired fame for ...

of Macedonia (276–239 BCE), Magas

Magas (russian: Мага́с) is the capital town of the Republic of Ingushetia, Russia. It was founded in 1995 and replaced Nazran as the capital of the republic in 2002. Due to this distinction, Magas is the smallest capital of a federal subje ...

(288–258 BCE) in Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

(modern Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

), and Alexander II (272–255 BCE) in Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich ...

(modern Northwestern Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

). One of the edicts states:

:"The conquest by Dharma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for '' ...

has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojana

A yojana (Sanskrit: योजन; th, โยชน์; my, ယူဇနာ) is a measure of distance that was used in ancient India, Thailand and Myanmar. A yojana is about 12–15 km.

Edicts of Ashoka (3rd century BCE)

Ashoka, in his Major R ...

s (5,400–9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Chola

The Chola dynasty was a Tamils, Tamil thalassocratic Tamil Dynasties, empire of southern India and one of the longest-ruling dynasties in the history of the world. The earliest datable references to the Chola are from inscriptions dated ...

s, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni

Tamraparni (Sanskrit for "with copper leaves" or "red-leaved") is an older name for multiple distinct places, including Sri Lanka, Tirunelveli in India, and the Thamirabarani River that flows through Tirunelveli.

As a name for Sri Lanka

The r ...

(Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

)." ( Edicts of Aśoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).

Furthermore, according to the Mahavamsa (XII) some of Ashoka's emissaries were Greek (Yona

The word Yona in Pali and the Prakrits, and the analogue Yavana in Sanskrit and Yavanar in Tamil, were words used in Ancient India to designate Greek speakers. "Yona" and "Yavana" are transliterations of the Greek word for "Ionians" ( grc, � ...

), particularly one named Dhammarakkhita. He also issued edicts in the Greek language as well as in Aramaic. One of them, found in Kandahar, advocates the adoption of "piety" (using the Greek term ''eusebeia

Eusebeia (Greek: from "pious" from ''eu'' meaning "well", and ''sebas'' meaning "reverence", itself formed from ''seb-'' meaning sacred awe and reverence especially in actions) is a Greek word abundantly used in Greek philosophy as well as in ...

'' for Dharma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for '' ...

) to the Greek community.

It is not clear how much these interactions may have been influential, but authors like Robert Linssen have commented that Buddhism may have influenced Western thought and religion at that time. Linssen points to the presence of Buddhist communities in the Hellenistic world around that period, in particular in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

(mentioned by Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and ...

), and to the pre-Christian monastic order of the Therapeutae

The Therapeutae were a religious sect which existed in Alexandria and other parts of the ancient Greek world. The primary source concerning the Therapeutae is the ''De vita contemplativa'' ("The Contemplative Life"), traditionally ascribed to the ...

(possibly a deformation of the Pāli word "Theravāda

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

"), who may have "almost entirely drawn (its) inspiration from the teaching and practices of Buddhist asceticism" and may even have been descendants of Aśoka's emissaries to the West. Philosophers like Hegesias of Cyrene

Hegesias ( el, Ἡγησίας; fl. 290 BC) of Cyrene was a Cyrenaic philosopher. He argued that eudaimonia (happiness) is impossible to achieve, and that the goal of life should be the avoidance of pain and sorrow. Conventional values suc ...

and Pyrrho are sometimes thought to have been influenced by Buddhist teachings.

Buddhist gravestones from the Ptolemaic period have also been found in Alexandria, decorated with depictions of the Dharma wheel. The presence of Buddhists in Alexandria has even drawn the conclusion that they influenced monastic Christianity. In the 2nd century CE, the Christian dogmatist, Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and ...

recognized Bactrian '' śramanas'' and Indian ''gymnosophist

Gymnosophists ( grc, γυμνοσοφισταί, ''gymnosophistaí'', i.e. "naked philosophers" or "naked wise men" (from Greek γυμνός ''gymnós'' "naked" and σοφία ''sophía'' "wisdom")) is the name given by the Greeks to certain anc ...

s'' for their influence on Greek thought.

Establishment of Sri Lanka Buddhism

Sri Lankan chronicles like the '' Dipavamsa'' state that Ashoka's son Mahinda brought Buddhism to the island during the 2nd century BCE. In addition, Ashoka's daughter, Saṅghamitta also established the

Sri Lankan chronicles like the '' Dipavamsa'' state that Ashoka's son Mahinda brought Buddhism to the island during the 2nd century BCE. In addition, Ashoka's daughter, Saṅghamitta also established the bhikkhunī

A bhikkhunī ( pi, 𑀪𑀺𑀓𑁆𑀔𑀼𑀦𑀻) or bhikṣuṇī ( sa, भिक्षुणी) is a fully ordained Nun, female monastic in Buddhism. Male monastics are called bhikkhus. Both bhikkhunis and bhikkhus live by the Vinaya, a ...

(order for nuns) in Sri Lanka, also bringing with her a sapling of the sacred bodhi tree that was subsequently planted in Anuradhapura

Anuradhapura ( si, අනුරාධපුරය, translit=Anurādhapuraya; ta, அனுராதபுரம், translit=Aṉurātapuram) is a major city located in north central plain of Sri Lanka. It is the capital city of North Central ...

. These two figures are seen as the mythical founders of the Sri Lankan Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

. They are said to have converted the King Devanampiya Tissa

Tissa, later Devanampiya Tissa, was one of the earliest kings of Sri Lanka based at the ancient capital of Anuradhapura from 247 BC to 207 BC. His reign was notable for the arrival of Buddhism in Sri Lanka under the aegis of the Mauryan ...

(307–267 BCE) and many of the nobility.

The first architectural records of Buddha images, however, actually come from the reign of King Vasabha

Vasabha ( Sinhala: ) was a monarch of the Anuradhapura period of Sri Lanka. He is considered to be the pioneer of the construction of large-scale irrigation works and underground waterways in Sri Lanka to support paddy cultivation. 11 reservoirs ...

(65–109 CE). The major Buddhist monasteries and schools in Ancient Sri Lanka were Mahāvihāra, Abhayagiri and Jetavana

Jetavana (Jethawanaramaya or Weluwanaramaya ''buddhist literature'') was one of the most famous of the Buddhist monasteries or viharas in India (present-day Uttar Pradesh). It was the second vihara donated to Gautama Buddha after the Venuvan ...

. The Pāli canon

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

During th ...

was written down during the 1st century BCE to preserve the teaching in a time of war and famine. It is the only complete collection of Buddhist texts

Buddhist texts are those religious texts which belong to the Buddhist tradition. The earliest Buddhist texts were not committed to writing until some centuries after the death of Gautama Buddha. The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts a ...

to survive in a Middle Indo-Aryan language

The Middle Indo-Aryan languages (or Middle Indic languages, sometimes conflated with the Prakrits, which are a stage of Middle Indic) are a historical group of languages of the Indo-Aryan family. They are the descendants of Old Indo-Aryan (OIA; ...

. It reflects the tradition of the Mahavihara

Mahavihara () is the Sanskrit and Pali term for a great vihara (centre of learning or Buddhist monastery) and is used to describe a monastic complex of viharas.

Mahaviharas of India

A range of monasteries grew up in ancient Magadha (modern Bihar ...

school. Later Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

Mahavihara

Mahavihara () is the Sanskrit and Pali term for a great vihara (centre of learning or Buddhist monastery) and is used to describe a monastic complex of viharas.

Mahaviharas of India

A range of monasteries grew up in ancient Magadha (modern Bihar ...

commentators of the Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

such as Buddhaghoṣa (4th–5th century) and Dhammapāla (5th–6th century), systematized the traditional Sri Lankan commentary literature (Atthakatha

Aṭṭhakathā (Pali for explanation, commentary) refers to Pali-language Theravadin Buddhist commentaries to the canonical Theravadin Tipitaka. These commentaries give the traditional interpretations of the scriptures. The major commentaries w ...

).

Although Mahāyāna Buddhism

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

gained some influence in Sri Lanka as it was studied in Abhayagiri and Jetavana

Jetavana (Jethawanaramaya or Weluwanaramaya ''buddhist literature'') was one of the most famous of the Buddhist monasteries or viharas in India (present-day Uttar Pradesh). It was the second vihara donated to Gautama Buddha after the Venuvan ...

, the Mahavihara

Mahavihara () is the Sanskrit and Pali term for a great vihara (centre of learning or Buddhist monastery) and is used to describe a monastic complex of viharas.

Mahaviharas of India

A range of monasteries grew up in ancient Magadha (modern Bihar ...

(“Great Monastery”) school became dominant in Sri Lanka following the reign of Parakramabahu I

Parākramabāhu I ( Sinhala: මහා පරාක්රමබාහු, 1123–1186), or Parakramabahu the Great, was the king of Polonnaruwa from 1153 to 1186. He oversaw the expansion and beautification of his capital, constructed extensiv ...

(1153–1186), who abolished the Abhayagiri and Jetavanin traditions.

Mahāyāna Buddhism

The Buddhist movement that became known as Mahayana (Great Vehicle) and also the Bodhisattvayana, began sometime between 150 BCE and 100 CE, drawing on both Mahasamghika and

The Buddhist movement that became known as Mahayana (Great Vehicle) and also the Bodhisattvayana, began sometime between 150 BCE and 100 CE, drawing on both Mahasamghika and Sarvastivada

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (Sanskrit and Pali: 𑀲𑀩𑁆𑀩𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀺𑀯𑀸𑀤, ) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (3rd century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy ...

trends. The earliest inscription which is recognizably Mahayana dates from 180 CE and is found in Mathura

Mathura () is a city and the administrative headquarters of Mathura district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is located approximately north of Agra, and south-east of Delhi; about from the town of Vrindavan, and from Govardhan. ...

.

The Mahayana emphasized the Bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

path to full Buddhahood

In Buddhism, Buddha (; Pali, Sanskrit: 𑀩𑀼𑀤𑁆𑀥, बुद्ध), "awakened one", is a title for those who are awake, and have attained nirvana and Buddhahood through their own efforts and insight, without a teacher to point out ...

(in contrast to the spiritual goal of arhat

In Buddhism, an ''arhat'' (Sanskrit: अर्हत्) or ''arahant'' (Pali: अरहन्त्, 𑀅𑀭𑀳𑀦𑁆𑀢𑁆) is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved ''Nirvana'' and liberated ...

ship). It emerged as a set of loose groups associated with new texts named the Mahayana sutras

The Mahāyāna sūtras are a broad genre of Buddhist scriptures (''sūtra'') that are accepted as canonical and as ''buddhavacana'' ("Buddha word") in Mahāyāna Buddhism. They are largely preserved in the Chinese Buddhist canon, the Tibetan B ...

. The Mahayana sutras promoted new doctrines, such as the idea that "there exist other Buddhas who are simultaneously preaching in countless other world-systems". In time Mahayana Bodhisattvas and also multiple Buddhas came to be seen as transcendental beneficent beings who were subjects of devotion.

Mahayana remained a minority among Indian Buddhists for some time, growing slowly until about half of all monks encountered by Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

in 7th-century India were Mahayanists. Early Mahayana schools of thought included the Mādhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhist ...

, Yogācāra

Yogachara ( sa, योगाचार, IAST: '; literally "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga") is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through t ...

, and Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gone ...

(''Tathāgatagarbha'') teachings. Mahayana is today the dominant form of Buddhism in East Asia

East Asian Buddhism or East Asian Mahayana is a collective term for the schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed across East Asia which follow the Chinese Buddhist canon. These include the various forms of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and V ...

and Tibet.

Several scholars have suggested that the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, which are among the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras, developed among the Mahāsāṃghika

The Mahāsāṃghika ( Brahmi: 𑀫𑀳𑀸𑀲𑀸𑀁𑀖𑀺𑀓, "of the Great Sangha", ) was one of the early Buddhist schools. Interest in the origins of the Mahāsāṃghika school lies in the fact that their Vinaya recension appears in ...

along the Kṛṣṇa River in the Āndhra region of South India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, as well as the union territo ...

. The earliest Mahāyāna sūtras to include the very first versions of the Prajñāpāramitā genre, along with texts concerning Akṣobhya Buddha, which were probably written down in the 1st century BCE in the south of India.Akira, Hirakawa (translated and edited by Paul Groner) (1993). ''A History of Indian Buddhism''. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: pp. 253, 263, 268 A.K. Warder

Anthony Kennedy Warder (8 September 1924 – 8 January 2013) was a British Indologist. His best-known works are ''Introduction to Pali'' (1963), ''Indian Buddhism'' (1970), and the eight-volume ''Indian Kāvya Literature'' (1972–2011).

Life

Wa ...

believes that "the Mahāyāna originated in the south of India and almost certainly in the Āndhra country." Anthony Barber and Sree Padma also trace Mahayana Buddhism to ancient Buddhist sites in the lower Kṛṣṇa Valley, including Amaravati Stupa

The Amarāvati ''Stupa'', is a ruined Buddhist '' stūpa'' at the village of Amaravathi, Palnadu district, Andhra Pradesh, India, probably built in phases between the third century BCE and about 250 CE. It was enlarged and new sculptures repla ...

, Nāgārjunakoṇḍā and Jaggayyapeṭa.

Shunga dynasty (2nd–1st century BCE)

The Shunga dynasty (185–73 BCE) was established about 50 years after Ashoka's death. After assassinating King

The Shunga dynasty (185–73 BCE) was established about 50 years after Ashoka's death. After assassinating King Brhadrata

Brihadratha was the last ruler of the Mauryan Empire. He ruled from 187 to 185 BCE, when he was killed by his general, Pushyamitra Shunga, who went on to establish the Shunga Empire. The Mauryan territories, centred on the capital of Patal ...

(last of the Mauryan

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until ...

rulers), military commander-in-chief Pushyamitra Shunga took the throne. Buddhist religious scriptures such as the Aśokāvadāna allege that Pushyamitra (an orthodox Brahmin

Brahmin (; sa, ब्राह्मण, brāhmaṇa) is a varna as well as a caste within Hindu society. The Brahmins are designated as the priestly class as they serve as priests (purohit, pandit, or pujari) and religious teachers (guru ...

) was hostile towards Buddhists and persecuted the Buddhist faith. Buddhists wrote that he "destroyed hundreds of monasteries and killed hundreds of thousands of innocent Monks": 840,000 Buddhist stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumamb ...

s which had been built by Ashoka were destroyed, and 100 gold coins were offered for the head of each Buddhist monk.

Modern historians, however, dispute this view in the light of literary and archaeological evidence. They opine that following Ashoka's sponsorship of Buddhism, it is possible that Buddhist institutions fell on harder times under the Shungas, but no evidence of active persecution has been noted. Etienne Lamotte observes: "To judge from the documents, Pushyamitra must be acquitted through lack of proof."

Another eminent historian, Romila Thapar

Romila Thapar (born 30 November 1931) is an Indian historian. Her principal area of study is ancient India, a field in which she is pre-eminent. Quotr: "The pre-eminent interpreter of ancient Indian history today. ... " Thapar is a Professor ...

points to archaeological evidence that "suggests the contrary" to the claim that "Pushyamitra was a fanatical anti-Buddhist" and that he "never actually destroyed 840,000 stupas as claimed by Buddhist works, if any". Thapar stresses that Buddhist accounts are probably hyperbolic renditions of Pushyamitra's attack of the Mauryas, and merely reflect the desperate frustration of the Buddhist religious figures in the face of the possibly irreversible decline in the importance of their religion under the Shungas.

During the period, Buddhist monks deserted the Ganges

The Ganges ( ) (in India: Ganga ( ); in Bangladesh: Padma ( )). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international river to which India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China are the riparian states." is ...

valley, following either the northern road ('' uttarapatha'') or the southern road (''dakṣinapatha''). Conversely, Buddhist artistic creation stopped in the old Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

area, to reposition itself either in the northwest area of Gandhāra

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Val ...

and Mathura

Mathura () is a city and the administrative headquarters of Mathura district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is located approximately north of Agra, and south-east of Delhi; about from the town of Vrindavan, and from Govardhan. ...

or in the southeast around Amaravati Stupa

The Amarāvati ''Stupa'', is a ruined Buddhist '' stūpa'' at the village of Amaravathi, Palnadu district, Andhra Pradesh, India, probably built in phases between the third century BCE and about 250 CE. It was enlarged and new sculptures repla ...

. Some artistic activity also occurred in central India, as in Bhārhut, to which the Shungas may or may not have contributed.

Greco-Buddhism

The

The Greco-Bactrian

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the India ...

king Demetrius I (reigned c. 200–180 BCE) invaded the Indian Subcontinent, establishing an Indo-Greek kingdom

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya), was a Hellenistic-era Greek kingdom covering various parts of Afghanistan and the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent ( ...

that was to last in parts of Northwest South Asia until the end of the 1st century CE.

Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek and Greco-Bactrian kings. One of the most famous Indo-Greek kings is Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

(reigned c. 160–135 BCE). He may have converted to Buddhism and is presented in the Mahāyāna tradition as one of the great benefactors of the faith, on a par with king Aśoka or the later Kushan king Kaniśka. Menander's coins bear designs of the eight-spoked dharma wheel

The dharmachakra (Sanskrit: धर्मचक्र; Pali: ''dhammacakka'') or wheel of dharma is a widespread symbol used in Indian religions such as Hinduism, Jainism, and especially Buddhism.John C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel, ''The Circle o ...

, a classic Buddhist symbol.

Direct cultural exchange is also suggested by a dialogue called the Debate of King Milinda ( ''Milinda Pañha'') which recounts a discussion between Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

and the Buddhist monk Nāgasena

Nāgasena was a Sarvastivadan Buddhist sage who lived around 150 BC. His answers to questions about Buddhism posed by Menander I (Pali: ''Milinda''), the Indo-Greek king of northwestern India, are recorded in the '' Milinda Pañha'' and the Sa ...

, who was himself a student of the Greek Buddhist monk Mahadharmaraksita

Mahadhammarakkhita (Sanskrit: ''Mahadharmaraksita'', literally "Great protector of the Dharma") was a Greek (in Pali:"Yona", lit. " Ionian") Buddhist master, who lived during the 2nd century BCE during the reign of the Indo-Greek king Menander ...

. Upon Menander's death, the honor of sharing his remains was claimed by the cities under his rule, and they were enshrined in stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumamb ...

s, in a parallel with the historic Buddha. Several of Menander's Indo-Greek

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya), was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era Ancient Greece, Greek kingdom covering various parts of Afghanistan and the northwestern r ...

successors inscribed "Follower of the Dharma," in the Kharoṣṭhī

The Kharoṣṭhī script, also spelled Kharoshthi (Kharosthi: ), was an ancient Indo-Iranian script used by various Aryan peoples in north-western regions of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely around present-day northern Pakistan and e ...

script, on their coins.

During the first century BCE the first anthropomorphic

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. It is considered to be an innate tendency of human psychology.

Personification is the related attribution of human form and characteristics t ...

representations of the Buddha are found in the lands ruled by the Indo-Greeks, in a realistic style known as Greco-Buddhist

Greco-Buddhism, or Graeco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism, which developed between the fourth century BC and the fifth century AD in Gandhara, in present-day north-western Pakistan and parts of nort ...

. Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence: the Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

toga

The toga (, ), a distinctive garment of ancient Rome, was a roughly semicircular cloth, between in length, draped over the shoulders and around the body. It was usually woven from white wool, and was worn over a tunic. In Roman historical tra ...

-like wavy robe covering both shoulders (more exactly, its lighter version, the Greek '' himation''), the contrapposto

''Contrapposto'' () is an Italian term that means "counterpoise". It is used in the visual arts to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot, so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs in the a ...

stance of the upright figures (see: 1st–2nd century Gandhara standing Buddhas), the stylicized Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

curly hair and topknot (ushnisha

The ushnisha (, IAST: ) is a three-dimensional oval at the top of the head of the Buddha. In Pali scriptures, it is the crown of Lord Buddha, the symbol of his Enlightenment and Enthronement.

Description

The Ushnisha is the thirty-second of th ...

) apparently derived from the style of the Belvedere Apollo

The ''Apollo Belvedere'' (also called the ''Belvedere Apollo, Apollo of the Belvedere'', or ''Pythian Apollo'') is a celebrated marble sculpture from Classical Antiquity.

The ''Apollo'' is now thought to be an original Roman creation of Hadrianic ...

(330 BCE), and the measured quality of the faces, all rendered with strong artistic realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

(See: Greek art

Greek art began in the Cycladic and Minoan civilization, and gave birth to Western classical art in the subsequent Geometric, Archaic and Classical periods (with further developments during the Hellenistic Period). It absorbed influences of ...

). A large quantity of sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

s combining Buddhist and purely Hellenistic styles and iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

were excavated at the Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

n site of Hadda.

Several influential Greek Buddhist monks are recorded. Mahadharmaraksita

Mahadhammarakkhita (Sanskrit: ''Mahadharmaraksita'', literally "Great protector of the Dharma") was a Greek (in Pali:"Yona", lit. " Ionian") Buddhist master, who lived during the 2nd century BCE during the reign of the Indo-Greek king Menander ...

(literally translated as 'Great Teacher/Preserver of the Dharma'), was "a Greek ("Yona

The word Yona in Pali and the Prakrits, and the analogue Yavana in Sanskrit and Yavanar in Tamil, were words used in Ancient India to designate Greek speakers. "Yona" and "Yavana" are transliterations of the Greek word for "Ionians" ( grc, � ...

") Buddhist head monk", according to the Mahavamsa (Chap. XXIX), who led 30,000 Buddhist monks from "the Greek city of Alasandra" (Alexandria of the Caucasus

Alexandria in the Caucasus ( grc, Ἀλεξάνδρεια) (medieval Kapisa, modern Bagram) was a colony of Alexander the Great (one of many colonies designated with the name ''Alexandria''). He founded the colony at an important junction of co ...

, around 150 km north of today's Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

), to Sri Lanka for the dedication of the Great Stupa in Anuradhapura

Anuradhapura ( si, අනුරාධපුරය, translit=Anurādhapuraya; ta, அனுராதபுரம், translit=Aṉurātapuram) is a major city located in north central plain of Sri Lanka. It is the capital city of North Central ...

during the rule (165–135 BCE) of King Menander I

Menander I Soter ( grc, Μένανδρος Σωτήρ, Ménandros Sōtḗr, Menander the Saviour; pi, मिलिन्दो, Milinda), was a Greco-Bactrian and later Indo-Greek King (reigned c.165/155Bopearachchi (1998) and (1991), respectivel ...

. Dhammarakkhita (meaning: ''Protected by the Dharma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for '' ...

''), was one of the missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

sent by the Mauryan

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until ...

emperor Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

to proselytize the Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

faith. He is described as being a Greek (Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

: "Yona", lit. "Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

n") in the Sri Lankan '' Mahavamsa.''

Kushan empire and Gandharan Buddhism

The

The Kushan empire

The Kushan Empire ( grc, Βασιλεία Κοσσανῶν; xbc, Κυϸανο, ; sa, कुषाण वंश; Brahmi: , '; BHS: ; xpr, 𐭊𐭅𐭔𐭍 𐭇𐭔𐭕𐭓, ; zh, 貴霜 ) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, i ...

(30–375 CE) was formed by the invading Yuezhi

The Yuezhi (;) were an ancient people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat ...

nomads in the 1st century BCE. It eventually encompassed much of northern India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Kushans adopted elements of the Hellenistic culture of Bactria and the Indo-Greeks. During Kushan rule, Gandharan Buddhism

Gandhāran Buddhism refers to the Buddhist culture of ancient Gandhāra which was a major center of Buddhism in the northwestern Indian subcontinent from the 3rd century BCE to approximately 1200 CE.Kurt Behrendt, Pia Brancaccio, Gandharan Bu ...

was at the height of its influence and a significant number of Buddhist centers were built or renovated.

The Buddhist art of Kushan Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

was a synthesis of Greco-Roman, Iranian and Indian elements. The Gandhāran Buddhist texts also date from this period. Written in Gāndhārī Prakrit

Gāndhārī is the modern name, coined by scholar Harold Walter Bailey (in 1946), for a Prakrit language found mainly in texts dated between the 3rd century BCE and 4th century CE in the region of Gandhāra, located in the northwestern Indian su ...

, they are the oldest Buddhist manuscripts yet discovered (c. 1st century CE). According to Richard Salomon, most of them belong to the Dharmaguptaka school.

Emperor Kanishka

Kanishka I (Sanskrit: कनिष्क, '; Greco-Bactrian: Κανηϸκε ''Kanēške''; Kharosthi: 𐨐𐨞𐨁𐨮𐨿𐨐 '; Brahmi: '), or Kanishka, was an emperor of the Kushan dynasty, under whose reign (c. 127–150 CE) the empire re ...

(128–151 CE) is particularly known for his support of Buddhism. During his reign, stupas and monasteries were built in the Gandhāran city of Peshawar

Peshawar (; ps, پېښور ; hnd, ; ; ur, ) is the sixth most populous city in Pakistan, with a population of over 2.3 million. It is situated in the north-west of the country, close to the International border with Afghanistan. It is ...

(Skt. ''Purusapura''), which he used as a capital.Heirman, Ann; Bumbacher, Stephan Peter (editors). The Spread of Buddhism, Brill, p. 57 Kushan royal support and the opening of trade routes allowed Gandharan Buddhism to spread along the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

to Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hydr ...

and thus to China.

Kanishka is also said to have convened a major Buddhist council for the Sarvastivada

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (Sanskrit and Pali: 𑀲𑀩𑁆𑀩𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀺𑀯𑀸𑀤, ) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (3rd century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy ...

tradition, either in Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

or Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

. Kanishka gathered 500 learned monks partly to compile extensive commentaries on the Abhidharma

The Abhidharma are ancient (third century BCE and later) Buddhist texts which contain detailed scholastic presentations of doctrinal material appearing in the Buddhist ''sutras''. It also refers to the scholastic method itself as well as the f ...

, although it is possible that some editorial work was carried out upon the existing Sarvastivada

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (Sanskrit and Pali: 𑀲𑀩𑁆𑀩𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀺𑀯𑀸𑀤, ) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (3rd century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy ...

canon itself. Allegedly during the council there were altogether three hundred thousand verses and over nine million statements compiled, and it took twelve years to complete. The main fruit of this council was the compilation of the vast commentary known as the Mahā-Vibhāshā ("Great Exegesis"), an extensive compendium and reference work on a portion of the Sarvāstivādin Abhidharma. Modern scholars such as Etienne Lamotte and David Snellgrove

David Llewellyn Snellgrove, FBA (29 June 192025 March 2016) was a British Tibetologist noted for his pioneering work on Buddhism in Tibet as well as his many travelogues.

Biography

Snellgrove was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire, and educated ...

have questioned the veracity of this traditional account.

Scholars believe that it was also around this time that a significant change was made in the language of the Sarvāstivādin canon, by converting an earlier Prakrit

The Prakrits (; sa, prākṛta; psu, 𑀧𑀸𑀉𑀤, ; pka, ) are a group of vernacular Middle Indo-Aryan languages that were used in the Indian subcontinent from around the 3rd century BCE to the 8th century CE. The term Prakrit is usu ...

version into Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

. Although this change was probably effected without significant loss of integrity to the canon, this event was of particular significance since Sanskrit was the sacred language of Brahmanism

The historical Vedic religion (also known as Vedicism, Vedism or ancient Hinduism and subsequently Brahmanism (also spelled as Brahminism)), constituted the religious ideas and practices among some Indo-Aryan peoples of northwest Indian Subco ...

in India, and was also being used by other thinkers, regardless of their specific religious or philosophical allegiance, thus enabling a far wider audience to gain access to Buddhist ideas and practices.

After the fall of the Kushans, small kingdoms ruled the Gandharan region, and later the Hephthalite White Huns conquered the area (circa 440s–670). Under the Hephthalites, Gandharan Buddhism continued to thrive in cities like

After the fall of the Kushans, small kingdoms ruled the Gandharan region, and later the Hephthalite White Huns conquered the area (circa 440s–670). Under the Hephthalites, Gandharan Buddhism continued to thrive in cities like Balkh

), named for its green-tiled ''Gonbad'' ( prs, گُنبَد, dome), in July 2001

, pushpin_map=Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_relief=yes

, pushpin_label_position=bottom

, pushpin_mapsize=300

, pushpin_map_caption=Location in Afghanistan ...

(Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

), as remarked by Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

who visited the region in the 7th century. Xuanzang notes that there were over a hundred Buddhist monasteries in the city, including the Nava Vihara as well many stupas and monks. After the end of the Hephthalite empire, Gandharan Buddhism declined in Gandhara proper (in the Peshawar basin). However it continued to thrive in adjacent areas like the Swat Valley

Swat District (, ps, سوات ولسوالۍ, ) is a district in the Malakand Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. With a population of 2,309,570 per the 2017 national census, Swat is the 15th-largest district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa prov ...

of Pakistan, Gilgit

Gilgit (; Shina: ; ur, ) is the capital city of Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan. The city is located in a broad valley near the confluence of the Gilgit River and the Hunza River. It is a major tourist destination in Pakistan, serving as a h ...

, Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

and in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

(in sites such as Bamiyan).

Spread to Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

was home to the international trade route known as the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

, which carried goods between China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and the Mediterranean world

The history of the Mediterranean region and of the cultures and people of the Mediterranean Basin is important for understanding the origin and development of the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Canaanite, Phoenician, Hebrew, Carthaginian, Minoan, Gre ...