Historical race concepts on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The concept of

''History and Theory'', Vol. 42, Feb 2003 William Desborough Cooley's ''The Negro Land of the Arabs Examined and Explained'' (1841) has excerpts of translations of Khaldun's work that were not affected by French colonial ideas. For example, Cooley quotes Khaldun's describing the great African civilization of Ghana (in Cooley's translation):

Among the 19th century naturalists who defined the field were Georges Cuvier, James Cowles Pritchard, Louis Agassiz, Charles Pickering (''Races of Man and Their Geographical Distribution'', 1848). Cuvier enumerated three races, Pritchard seven, Agassiz twelve, and Pickering eleven.

The 19th century saw the introduction of anthropological techniques such as anthropometrics, invented by Francis Galton and Alphonse Bertillon. They measured the shapes and sizes of skulls and related the results to group differences in intelligence or other attributes.

Stefan Kuhl wrote that the

Among the 19th century naturalists who defined the field were Georges Cuvier, James Cowles Pritchard, Louis Agassiz, Charles Pickering (''Races of Man and Their Geographical Distribution'', 1848). Cuvier enumerated three races, Pritchard seven, Agassiz twelve, and Pickering eleven.

The 19th century saw the introduction of anthropological techniques such as anthropometrics, invented by Francis Galton and Alphonse Bertillon. They measured the shapes and sizes of skulls and related the results to group differences in intelligence or other attributes.

Stefan Kuhl wrote that the

Arthur de Gobineau (1816–1882) was a successful diplomat for the

Arthur de Gobineau (1816–1882) was a successful diplomat for the

(Hosted by the Society for Nordish Physical Anthropology) #The Caucasian race is of dual origin consisting of Upper Paleolithic (mixture of ''

Hoover, Dwight W. "Paradigm Shift: The Concept of Race in the 1920s and the 1930s". ''Conspectus of History'' 1.7 (1981): 82–100.

* Koenig, Barbara A., Lee Sandra Soo-Jin, and Richardson Sarah S. ''Revisiting Race in a Genomic Age''. Piscataway: Rutgers University Press, 2008. * Lewis, B. ''Race and slavery in the Middle East''. Oxford University Press, New York, 1990. * Lieberman, L. "How 'Caucasoids' got such big crania and why they shrank: from Morton to Rushton". ''Current Anthropology'' 42:69–95, 2001. * Malik, Kenan. ''The Meaning of Race''. New York: New York University Press, 1996. * Meltzer, M. ''Slavery: a world history'', rev ed. DaCapo Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1993. * Rick Kittles, and S. O. Y. Keita, "Interpreting African Genetic Diversity", ''African Archaeological Review'', Vol. 16, No. 2,1999, pp. 1–5 * Sarich, Vincent, and Miele Frank. ''Race: the Reality of Human Differences''. Boulder: Westview Press, 2004. * Shipman, Pat. ''The Evolution of Racism: Human Differences and the Use and Abuse of Science''. 1994. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002. * Smedley, Audrey. ''Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview''. Boulder: Westview Press, 1999. * Snowden F. M. ''Before color prejudice: the ancient view of blacks''. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1983. * Stanton W. ''The leopard's spots: scientific attitudes toward race in America, 1815–1859''. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1960. * Stepan, Nancy. ''The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain, 1800–1960''. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, 1982 * Takaki, R. ''A different mirror: a history of multicultural America''. Little, Brown, Boston, 1993. * von Vacano, Diego. ''The Color of Citizenship: Race, Modernity and Latin American/Hispanic Political Thought''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Definition of "race" in the 1913 ''Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary''

provided by the ARTFL Project, University of Chicago. * Definition of "race" in the Wiktionary

The RaceSci Website

preserved at the

PBS website for the three-part television documentary ''Race – The Power of an Illusion''

with background reading and teaching resources. {{DEFAULTSORT:Historical Definitions Of Race Social constructionism fr:Race humaine#Historique de la notion

race

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

as a categorization of anatomically modern human

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

s (''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

'') has an extensive history in Europe and the Americas. The contemporary word ''race'' itself is modern; historically it was used in the sense of "nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective Identity (social science), identity of a group of people unde ...

, ethnic group" during the 16th to 19th centuries. Race acquired its modern meaning in the field of physical anthropology through scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

starting in the 19th century. With the rise of modern genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

, the concept of distinct human races in a biological sense has become obsolete. In 2019, the American Association of Biological Anthropologists

The American Association of Biological Anthropologists (AABA) is an international professional society of biological anthropologists, based in the United States. The organization publishes the ''American Journal of Physical Anthropology'', a pe ...

stated: "The belief in 'races' as natural aspects of human biology, and the structures of inequality (racism) that emerge from such beliefs, are among the most damaging elements in the human experience both today and in the past."

Etymology

The word "race", interpreted to mean an identifiable group of people who share a common descent, was introduced into English in about 1580, from the Old French ' (1512), from Italian '. An earlier but etymologically distinct word for a similar concept was the Latin word ' meaning a group sharing qualities related to birth, descent, origin, race, stock, or family; this Latin word is cognate with the Greek words "genos", () meaning "race or kind", and "gonos", which has meanings related to "birth, offspring, stock ...".Early history

In many ancient civilizations, individuals with widely varying physical appearances became full members of asociety

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

by growing up within that society or by adopting that society's cultural norms. (Snowden 1983; Lewis 1990)

Classical civilization

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

s from Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to China tended to invest the most importance in familial or tribal affiliation rather than an individual's physical appearance (Dikötter 1992; Goldenberg 2003). Societies still tended to equate physical characteristics, such as hair and eye colour, with psychological and moral qualities, usually assigning the highest qualities to their own people and lower qualities to the "Other", either lower classes or outsiders to their society. For example, a historian of the 3rd century Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

in the territory of present-day China describes barbarians of blond hair and green eyes as resembling "the monkeys from which they are descended".Gossett, Thomas F. New Edition, ''Race: The History of an Idea in America.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. (Gossett, pp. 4)

Dominant in ancient Greek and Roman conceptions of human diversity was the thesis that physical differences between different populations could be attributed to environmental factors. Though ancient peoples likely had no knowledge of evolutionary theory or genetic variability, their concepts of race could be described as malleable. Chief among environmental causes for physical difference in the ancient period were climate and geography. Though thinkers in ancient civilizations recognized differences in physical characteristics between different populations, the general consensus was that all non-Greeks were barbarians. This barbarian status, however, was not thought to be fixed; rather, one could shed the 'barbarian' status simply by adopting Greek culture. (Graves 2001)

Classical antiquity

Hippocrates of Kos

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of ...

believed, as many thinkers throughout early history did, that factors such as geography and climate played a significant role in the physical appearance of different peoples. He writes, "the forms and dispositions of mankind correspond with the nature of the country". He attributed physical and temperamental differences among different peoples to environmental factors such as climate, water sources, elevation and terrain. He noted that temperate climates created peoples who were "sluggish" and "not apt for labor", while extreme climates led to peoples who were "sharp", "industrious" and "vigilant". He also noted that peoples of "mountainous, rugged, elevated, and well-watered" countries displayed "enterprising" and "warlike" characteristics, while peoples of "level, windy, and well-watered" countries were "unmanly" and "gentle".

The Roman emperor Julian factored in the constitutions, laws, capacities, and character of peoples:

Middle Ages

Europeanmedieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

models of race generally mixed Classical ideas with the notion that humanity as a whole was descended from Shem

Shem (; he, שֵׁם ''Šēm''; ar, سَام, Sām) ''Sḗm''; Ge'ez: ሴም, ''Sēm'' was one of the sons of Noah in the book of Genesis and in the book of Chronicles, and the Quran.

The children of Shem were Elam, Ashur, Arphaxad, Lu ...

, Ham

Ham is pork from a leg cut that has been preserved by wet or dry curing, with or without smoking."Bacon: Bacon and Ham Curing" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 39. As a processed meat, the term "ham ...

and Japheth, the three sons of Noah, producing distinct Semitic (Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

tic), Hamitic (Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n), and Japhetic (Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

) peoples. The association between the sons of Noah and skin color dates back at least to the Babylonian ''Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

'', which states that the descendants of Ham were cursed with black skin. In the seventh century, the idea that black Africans were cursed with both dark skin and slavery began to gain strength with some Islamic writers, as black Africans became a slave class in the Islamic world.

In the 9th century, Al-Jahiz

Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو عثمان عمرو بن بحر الكناني البصري), commonly known as al-Jāḥiẓ ( ar, links=no, الجاحظ, ''The Bug Eyed'', born 776 – died December 868/Jan ...

, an Afro-Arab

Afro-Arabs are Arabs of full or partial Black African descent. These include populations within mainly the Sudanese, Emiratis, Yemenis, Saudis, Omanis, Sahrawis, Mauritanians, Algerians, Egyptians and Moroccans, with considerably long est ...

Islamic philosopher, attempted to explain the origins of different human skin color

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents and or indivi ...

s, particularly black skin, which he believed to be the result of the environment. He cited a stony region of black basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

in the northern Najd as evidence for his theory.

In the 14th century, the Islamic sociologist Ibn Khaldun, dispelled the Babylonian ''Talmuds account of peoples and their characteristics as a myth. He wrote that black skin was due to the hot climate of sub-Saharan Africa and not due to the descendants of Ham being cursed.

Independently of Ibn Khaldun's work, the question of whether skin colour is heritable or a product of the environment is raised in 17th to 18th century European anthropology.

Georgius Hornius (1666) inherits the rabbinical view of heritability, while François Bernier

François Bernier (25 September 162022 September 1688) was a French physician and traveller. He was born in Joué-Etiau in Anjou. He stayed (14 October 165820 February 1670) for around 12 years in India.

His 1684 publication "Nouvel ...

(1684) argues for at least partial influence of the environment.

Ibn Khaldun's work was later translated into French, especially for use in Algeria, but in the process, the work was "transformed from local knowledge to colonial categories of knowledge".Abdelmajid Hannoum, "Translation and the Colonial Imaginary: Ibn Khaldun Orientalist"''History and Theory'', Vol. 42, Feb 2003 William Desborough Cooley's ''The Negro Land of the Arabs Examined and Explained'' (1841) has excerpts of translations of Khaldun's work that were not affected by French colonial ideas. For example, Cooley quotes Khaldun's describing the great African civilization of Ghana (in Cooley's translation):

"When the conquest of the West (by the Arabs) was completed, and merchants began to penetrate into the interior, they saw no nation of the Blacks so mighty as Ghánah, the dominions of which extended westward as far as the Ocean. The King's court was kept in the city of Ghánah, which, according to the author of the 'Book of Roger' (El Idrisi), and the author of the 'Book of Roads and Realms' (El Bekri), is divided into two parts, standing on both banks of the Nile, and ranks among the largest and most populous cities of the world. The people of Ghánah had for neighbours, on the east, a nation, which, according to historians, was called Súsú; after which came another named Máli; and after that another known by the name of Kaǘkaǘ; although some people prefer a different orthography, and write this name Kághó. The last-named nation was followed by a people called Tekrúr. The people of Ghánah declined in course of time, being overwhelmed or absorbed by the Molaththemún (or muffled people; that is, the Morabites), who, adjoining them on the north towards the Berber country, attacked them, and, taking possession of their territory, compelled them to embrace the Mohammedan religion. The people of Ghánah, being invaded at a later period by the Súsú, a nation of Blacks in their neighbourhood, were exterminated, or mixed with other Black nations." William Desborough Cooley, ''The Negro Land of the Arabs Examined and Explained''Ibn Khaldun suggests a link between the rise of the Almoravids and the decline of Ghana. However, historians have found virtually no evidence for an Almoravid conquest of Ghana.

London: J. Arrowsmith, pp. 61–62

Early modern period

Scientists who were interested in natural history, including biological and geological scientists, were known as " naturalists". They would collect, examine, describe, and arrange data from their explorations into categories according to certain criteria. People who were particularly skilled at organizing specific sets of data in a logically and comprehensive fashion were known as classifiers and systematists. This process was a new trend in science that served to help answer fundamental questions by collecting and organizing materials for systematic study, also known astaxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

.Smedley, Audrey. Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview. Boulder: Westview Press, 1999.

As the study of natural history grew, so did scientists' effort to classify human groups. Some zoologists and scientists wondered what made humans different from animals in the primate family. Furthermore, they contemplated whether homo sapiens should be classified as one species with multiple varieties or separate species. In the 16th and 17th century, scientists attempted to classify ''Homo sapiens'' based on a geographic arrangement of human populations based on skin color, others simply on geographic location, shape, stature, food habits, and other distinguishing characteristics. Occasionally the term "race" was used, but most of the early taxonomists used classificatory terms, such as "peoples", "nations", "types", "varieties", and "species".

Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) and Jean Bodin (1530–1596), French philosopher, attempted a rudimentary geographic arrangement of known human populations based on skin color. Bodin's color classifications were purely descriptive, including neutral terms such as "duskish colour, like roasted quinze", "black", "chestnut", and "farish white".

17th century

German and English scientists, Bernhard Varen (1622–1650) and John Ray (1627–1705) classified human populations into categories according to stature, shape, food habits, and skin color, along with any other distinguishing characteristics. Ray was also the first person to produce a biological definition ofspecies

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

.

François Bernier

François Bernier (25 September 162022 September 1688) was a French physician and traveller. He was born in Joué-Etiau in Anjou. He stayed (14 October 165820 February 1670) for around 12 years in India.

His 1684 publication "Nouvel ...

(1625–1688) is believed to have developed the first comprehensive classification of humans into distinct races which was published in a French journal article in 1684, ''Nouvelle division de la terre par les différentes espèces ou races l'habitant'', New division of Earth by the different species or races which inhabit it. (Gossett, 1997:32–33). Bernier advocated using the "four quarters" of the globe as the basis for providing labels for human differences. The four subgroups that Bernier used were Europeans, Far Easterners, Negroes (blacks), and Lapps.C. Loring, Brace. ''"Race" is a Four-Letter Word: the Genesis of the Concept''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

18th century

As noted earlier, scientists attempted to classify ''Homo sapiens'' based on a geographic arrangement of human populations. Some based their hypothetical divisions of race on the most obvious physical differences, like skin color, while others used geographic location, shape, stature, food habits, and other distinguishing characteristics to delineate between races. However, cultural notions of racial and gender superiority tainted early scientific discovery. In the 18th century, scientists began to include behavioral or psychological traits in their reported observations—which traits often had derogatory or demeaning implications—and researchers often assumed that those traits were related to their race, and therefore, innate and unchangeable. Other areas of interest were to determine the exact number of races, categorize and name them, and examine the primary and secondary causes of variation between groups. TheGreat Chain of Being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, humans, animals and plants to minerals.

The great ...

, a medieval idea that there was a hierarchical structure of life from the most fundamental elements to the most perfect, began to encroach upon the idea of race. As taxonomy grew, scientists began to assume that the human species could be divided into distinct subgroups. One's "race" necessarily implied that one group had certain character qualities and physical dispositions that differentiated it from other human populations. Society assigned different values to those differentiations, as well as other, more trivial traits (a man with a strong chin was assumed to possess a stronger character than men with weaker chins). This essentially created a gap between races by deeming one race superior or inferior to another race, thus creating a hierarchy of races. In this way, science was used as justification for unfair treatment of different human populations.

The systematization of race concepts during the Enlightenment period brought with it the conflict between monogenism

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all human races. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the ...

(a single origin for all human races) and polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

(the hypothesis that races had separate origins). This debate was originally cast in creationist

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 'th ...

terms as a question of one versus many creations of humanity, but continued after evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

was widely accepted, at which point the question was given in terms of whether humans had split from their ancestral species one or many times.

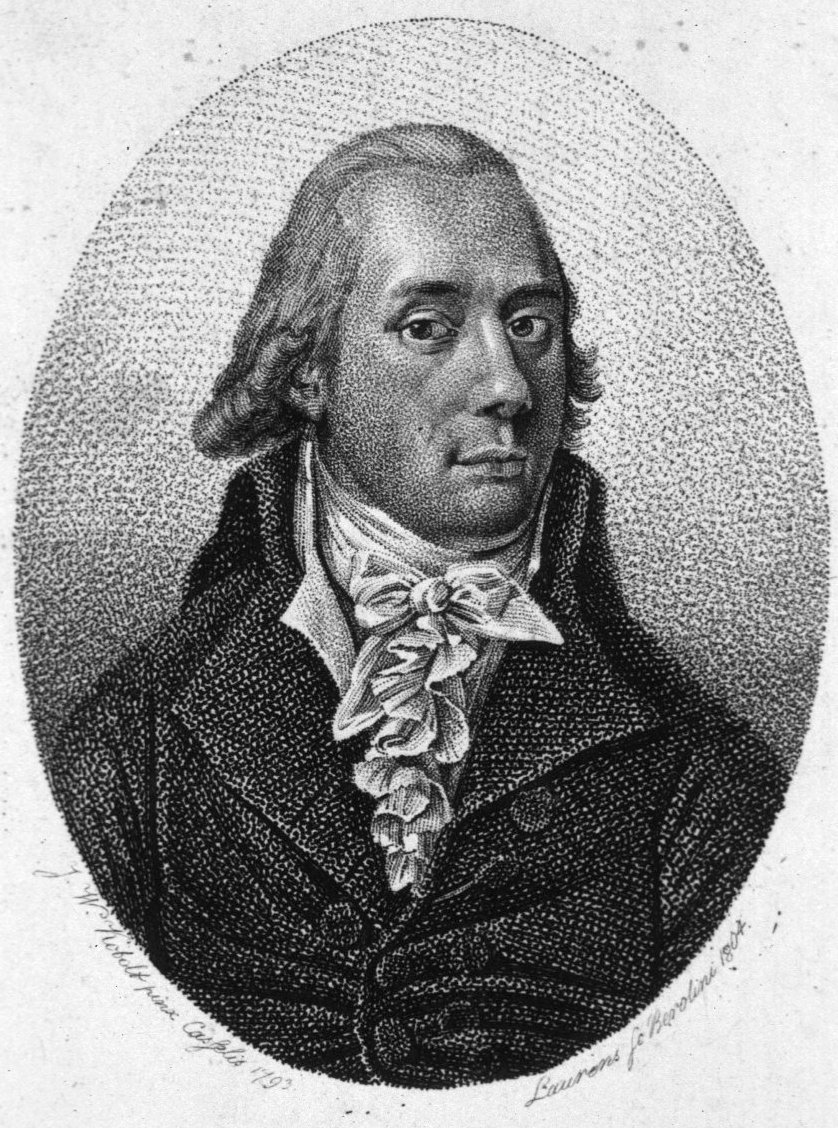

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist, and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He ...

(1752–1840) divided the human species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

into five races in 1779, later founded on crania research (description of human skulls), and called them (1793/1795):

* the Caucasian race (Europe, the Caucasus, Asia Minor, North Africa and West Asia)

* the Mongolian race (East Asia, Central Asia and South Asia)

* the Aethiopian race (Sub-Saharan Africa)

* the American race (North America and South America)

* the Malayan race

The concept of a Malay race was originally proposed by the German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840), and classified as a brown race. ''Malay'' is a loose term used in the late 19th century and early 20th century to describe the ...

(Southeast Asia)

Blumenbach argued that physical characteristics like the collective characteristic types of facial structure and hair characteristics, skin color, cranial profile, etc., depended on geography and nutrition and custom. Blumenbach's work included his description of sixty human crania (skulls) published originally in fascicules as ''Decas craniorum'' (Göttingen, 1790–1828). This was a founding work for other scientists in the field of craniometry

Craniometry is measurement of the cranium (the main part of the skull), usually the human cranium. It is a subset of cephalometry, measurement of the head, which in humans is a subset of anthropometry, measurement of the human body. It is dis ...

.

Further anatomical study led him to the conclusion that 'individual Africans differ as much, or even more, from other individual Africans as Europeans differ from Europeans'. Furthermore, he concluded that Africans were not inferior to the rest of mankind 'concerning healthy faculties of understanding, excellent natural talents and mental capacities'.

"Finally, I am of opinion that after all these numerous instances I have brought together of negroes of capacity, it would not be difficult to mention entire well-known provinces of Europe, from out of which you would not easily expect to obtain off-hand such good authors, poets, philosophers, and correspondents of the Paris Academy; and on the other hand, there is no so-called savage nation known under the sun which has so much distinguished itself by such examples of perfectibility and original capacity for scientific culture, and thereby attached itself so closely to the most civilized nations of the earth, as the Negro."These five groups saw some continuity in the various classification schemes of the 19th century, in some cases augmented, e.g. by the Australoid race and the Capoid race in some cases the Mongolian (East Asian) and American collapsed into a single group.

Racial anthropology (1850–1930)

Among the 19th century naturalists who defined the field were Georges Cuvier, James Cowles Pritchard, Louis Agassiz, Charles Pickering (''Races of Man and Their Geographical Distribution'', 1848). Cuvier enumerated three races, Pritchard seven, Agassiz twelve, and Pickering eleven.

The 19th century saw the introduction of anthropological techniques such as anthropometrics, invented by Francis Galton and Alphonse Bertillon. They measured the shapes and sizes of skulls and related the results to group differences in intelligence or other attributes.

Stefan Kuhl wrote that the

Among the 19th century naturalists who defined the field were Georges Cuvier, James Cowles Pritchard, Louis Agassiz, Charles Pickering (''Races of Man and Their Geographical Distribution'', 1848). Cuvier enumerated three races, Pritchard seven, Agassiz twelve, and Pickering eleven.

The 19th century saw the introduction of anthropological techniques such as anthropometrics, invented by Francis Galton and Alphonse Bertillon. They measured the shapes and sizes of skulls and related the results to group differences in intelligence or other attributes.

Stefan Kuhl wrote that the eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

movement rejected the racial and national hypotheses of Arthur Gobineau and his writing ''An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races

''Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines'' (Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, 1853–1855) is a racist and pseudoscientific work of French writer Joseph Arthur, Comte de Gobineau, which argues that there are intellectual differen ...

''. According to Kuhl, the eugenicists believed that nations were political and cultural constructs, not race constructs, because nations were the result of race mixtures. Georges Vacher de Lapouge

Count Georges Vacher de Lapouge (; 12 December 1854 – 20 February 1936) was a French anthropologist and a theoretician of eugenics and racialism. He is known as the founder of anthroposociology, the anthropological and sociological study of race ...

's "anthroposociology", asserted as self-evident the biological inferiority of particular groups (Kevles 1985). In many parts of the world, the idea of race became a way of rigidly dividing groups by culture as well as by physical appearances (Hannaford 1996). Campaigns of oppression and genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

were often motivated by supposed racial differences (Horowitz 2001).

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, the tension between some who believed in hierarchy and innate superiority, and others who believed in human equality, was at a paramount. The former continued to exacerbate the belief that certain races were innately inferior by examining their shortcomings, namely by examining and testing intelligence between groups. Some scientists claimed that there was a biological determinant of race by evaluating one's genes and DNA. Different methods of eugenics, the study and practice of human selective breeding often with a race as a primary concentration, was still widely accepted in Britain, Germany, and the United States.Sarich, Vincent, and Miele Frank. Race: the Reality of Human Differences. Boulder: Westview Press, 2004. On the other hand, many scientists understood race as a social construct

Social constructionism is a theory in sociology, social ontology, and communication theory which proposes that certain ideas about physical reality arise from collaborative consensus, instead of pure observation of said reality. The theory ...

. They believed that the phenotypical

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological prop ...

expression of an individual were determined by one's genes that are inherited through reproduction but there were certain social constructs, such as culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups ...

, environment, and language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

that were primary in shaping behavioral characteristics. Some advocated that race 'should centre not on what race explains about society, but rather on the questions of who, why and with what effect social significance is attached to racial attributes that are constructed in particular political and socio-economic contexts', and thus, addressing the "folk" or "mythological representations" of race.

Louis Agassiz's racial definitions

After Louis Agassiz (1807–1873) traveled to the United States, he became a prolific writer in what has been later termed the genre of scientific racism. Agassiz was specifically a believer and advocate inpolygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

, that races came from separate origins (specifically separate creations), were endowed with unequal attributes, and could be classified into specific climatic zones, in the same way he felt other animals and plants could be classified.

These included Western American Temperate (the indigenous peoples west of the Rockies); Eastern American Temperate (east of the Rockies); Tropical Asiatic (south of the Himalayas); Temperate Asiatic (east of the Urals and north of the Himalayas); South American Temperate (South America); New Holland (Australia); Arctic (Alaska and Arctic Canada); Cape of Good Hope (South Africa); and American Tropical (Central America and the West Indies).

Agassiz denied that species originated in single pairs, whether at a single location or at many. He argued instead multiple individuals in each species were created at the same time and then distributed throughout the continents where God meant for them to dwell. His lectures on polygenism were popular among the slaveholders in the South, for many this opinion legitimized the belief in a lower standard of the Negro.

His stance in this case was considered to be quite radical in its time, because it went against the more orthodox and standard reading of the Bible in his time which implied all human stock descended from a single couple (Adam and Eve), and in his defense Agassiz often used what now sounds like a very "modern" argument about the need for independence between science and religion; though Agassiz, unlike many polygeneticists, maintained his religious beliefs and was not anti-Biblical in general.

In the context of ethnology and anthropology of the mid-19th century, Agassiz's polygenetic views became explicitly seen as opposing Darwin's views on race, which sought to show the common origin of all human races and the superficiality of racial differences. Darwin's second book on evolution, ''The Descent of Man'', features extensive argumentation addressing the single origin of the races, at times explicitly opposing Agassiz's theories.

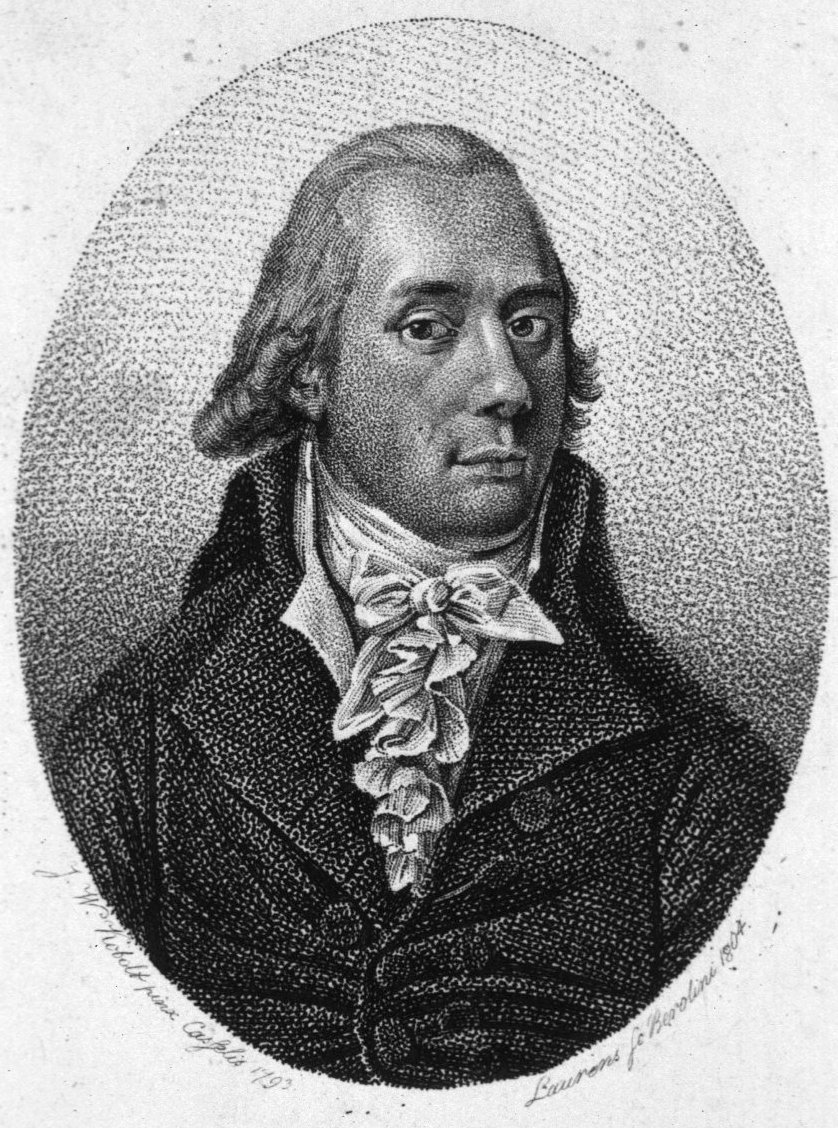

Arthur de Gobineau

Arthur de Gobineau (1816–1882) was a successful diplomat for the

Arthur de Gobineau (1816–1882) was a successful diplomat for the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930 ...

. Initially he was posted to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, before working in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and other countries. He came to believe that race created culture, arguing that distinctions between the three "black", "white", and "yellow" races were natural barriers, and that " race-mixing" breaks those barriers down and leads to chaos. He classified the populations of the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

, North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, and southern France as being racially mixed.

Gobineau also believed that the white race was superior to all others. He thought it corresponded to the ancient Indo-European culture, also known as " Aryan". Gobineau originally wrote that the white race's miscegenation was inevitable. He attributed much of the economic turmoils in France to the pollution of races. Later on in his life, he altered his opinion to believe that the white race could be saved.

To Gobineau, the development of empires was ultimately destructive to the "superior races" that created them, since they led to the mixing of distinct races. This he saw as a degenerative process.

According to his definitions, the people of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, most of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, most of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, southern and western Iran as well as Switzerland, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Northern Italy, and a large part of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, consisted of a degenerative race that arose from miscegenation. Also according to him, the whole population of North India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Central ...

consisted of a yellow race.

Thomas Huxley's racial definitions

Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

(1825–1895) wrote one paper, "On the Geographical Distribution of the Chief Modifications of Mankind" (1870), in which he proposed a distinction within the human species ('races'), and their distribution across the earth. He also acknowledged that certain geographical areas with more complex ethnic compositions, including much of the Horn of Africa and the India subcontinent, did not fit into his racial paradigm. As such, he noted that: "I have purposely omitted such people as the Abyssinians and the Hindoos, who there is every reason to believe result from the intermixture of distinct stocks." By the late nineteenth century, Huxley's Xanthochroi group had been redefined as the Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming tha ...

, whereas his Melanochroi became the Mediterranean race

The Mediterranean race (also Mediterranid race) was a historical race concepts, historical race concept that was a sub-race of the Caucasian race as categorised by anthropology, anthropologists in the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. According to ...

. His Melanochroi thus eventually also comprised various other dark Caucasoid populations, including the Hamites

Hamites is the name formerly used for some Northern and Horn of Africa peoples in the context of a now-outdated model of dividing humanity into different races which was developed originally by Europeans in support of colonialism and slavery ...

(e.g. Berbers, Somalis, northern Sudanese, ancient Egyptians) and Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

.

Huxley's paper was rejected by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and this became one of the many theories to be advanced and dropped by the early exponents of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

.

Despite rejection by Huxley and the science community, the paper is sometimes cited in support of racialism. Along with Darwin, Huxley was a monogenist, the belief that all humans are part of the same species, with morphological variations emerging out of an initial uniformity. (Stepan, p. 44). This view contrasts polygenism, the theory that each race is actually a separate species with separate sites of origin.

Despite Huxley's monogenism and his abolitionism on ethical grounds, Huxley assumed a hierarchy of innate abilities, a stance evinced in papers such as "Emancipation Black and White" and his most famous paper, "Evolution and Ethics".

In the former, he writes that the "highest places in the hierarchy of civilization will assuredly not be within the reach of our dusky cousins, though it is by no means necessary that they should be restricted to the lowest". (Stepan, p. 79–80).

Charles Darwin and race

ThoughCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's evolutionary theory was set forth in 1859 upon publication of ''On the Origin of Species'', this work was largely absent of explicit reference to Darwin's theory applied to man. This application by Darwin would not become explicit until 1871 with the publication of his second great book on evolution, '' The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex''.

Darwin's publication of this book occurred within the heated debates between advocates of monogeny, who held that all races came from a common ancestor, and advocates of polygeny, who held that the races were separately created. Darwin, who had come from a family with strong abolitionist ties, had experienced and was disturbed by cultures of slavery during his voyage on the Beagle years earlier. Noted Darwin biographers Adrian Desmond

Adrian John Desmond (born 1947) is an English writer on the history of science and author of books about Charles Darwin.

Life

He studied physiology at London University and went on to study history of science and vertebrate palaeontology at Unive ...

and James Moore argue that Darwin's writings on evolution were not only influenced by his abolitionist tendencies, but also his belief that non-white races were equal in regard to their intellectual capacity as white races, a belief which had been strongly disputed by scientists such as Morton, Agassiz and Broca, all noted polygenists.

By the late 1860s, however, Darwin's theory of evolution had been thought to be compatible with the polygenist thesis (Stepan 1982). Darwin thus used ''Descent of Man'' to disprove the polygenist thesis and end the debate between polygeny and monogeny once and for all. Darwin also used it to disprove other hypotheses about racial difference that had persisted since the time of ancient Greece, for example, that differences in skin color and body constitution occurred because of differences of geography and climate.

Darwin concluded, for example, that the biological similarities between the different races were "too great" for the polygenist thesis to be plausible. He also used the idea of races to argue for the continuity between humans and animals, noting that it would be highly implausible that man should, by mere accident acquire characteristics shared by many apes.

Darwin sought to demonstrate that the physical characteristics that were being used to define race for centuries (i.e. skin color and facial features) were superficial and had no utility for survival. Because, according to Darwin, any characteristic that did not have survival value could not have been naturally selected, he devised another hypothesis for the development and persistence of these characteristics. The mechanism Darwin developed is known as sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection in which members of one biological sex choose mates of the other sex to mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex ( ...

.

Though the idea of sexual selection had appeared in earlier works by Darwin, it was not until the late 1860s when it received full consideration (Stepan 1982). Furthermore, it was not until 1914 that sexual selection received serious consideration as a racial theory by naturalist thinkers.

Darwin defined sexual selection as the "struggle between individuals of one sex, generally the males, for the possession of the other sex". Sexual selection consisted of two types for Darwin: 1.) The physical struggle for a mate, and 2.) The preference for some color or another, typically by females of a given species. Darwin asserted that the differing human races (insofar as race was conceived phenotypically) had arbitrary standards of ideal beauty, and that these standards reflected important physical characteristics sought in mates.

Broadly speaking, Darwin's attitudes of what race was and how it developed in the human species are attributable to two assertions, 1.) That all human beings, regardless of race, share a single, common ancestor, and 2.) Phenotypic racial differences are superficially selected, and have no survival value. Given these two beliefs, some believe Darwin to have established monogenism as the dominant paradigm for racial ancestry, and to have defeated the scientific racism practiced by Morton, Knott, Agassiz et al., as well as notions that there existed a natural racial hierarchy that reflected inborn differences and measures of value between the different human races.

Nevertheless, he stated: "The various races, when carefully compared and measured, differ much from each other – as in the texture of hair, the relative proportions of all parts of the body, the capacity of the lungs, the form and capacity of the skull, and even the convolutions of the brain. But it would be an endless task to specify the numerous points of difference. The races differ also in constitution, in acclimatization and in liability to certain diseases. Their mental characteristics are likewise very distinct; chiefly as it would appear in their emotion, but partly in their intellectual faculties." (''The Descent of Man'', chapter VII).

In ''The Descent of Man'', Darwin noted the great difficulty naturalists had in trying to decide how many "races" there actually were:

Man has been studied more carefully than any other animal, and yet there is the greatest possible diversity amongst capable judges whether he should be classed as a single species or race, or as two (Virey), as three (Jacquinot), as four (Kant), five (Blumenbach), six (Buffon), seven (Hunter), eight (Agassiz), eleven (Pickering), fifteen (Bory St. Vincent), sixteen (Desmoulins), twenty-two (Morton), sixty (Crawfurd), or as sixty-three, according to Burke. This diversity of judgment does not prove that the races ought not to be ranked as species, but it shews that they graduate into each other, and that it is hardly possible to discover clear distinctive characters between them.

Decline of racial studies after 1930

Several social and political developments that occurred at the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century led to the transformation in the discourse of race. Three movements that historians have considered are: the coming of massdemocracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

, the age of imperialist expansion, and the impact of Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

.Malik, Kenan. The Meaning of Race. New York: New York University Press, 1996. More than any other, the violence of Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

rule, the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

transformed the whole discussion of race. Nazism made an argument for racial superiority based on a biological basis. This led to the idea that people could be divided into discrete groups and based on the divisions, there would be severe, tortuous, and often fatal consequences. The exposition of Nazi racial theories

The Nazi Party adopted and developed several pseudoscientific racial classifications as part of its ideology (Nazism) in order to justify the genocide of groups of people which it deemed racially inferior. The Nazis considered the putative " ...

, which culminated in the Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

, created a moral revolution against racism. In 1945, and as a response to the genocide by Nazism, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

was formed. In 1950, it released a statement saying that there was no biological determinant or basis for race.

Consequently, studies of human variation focused more on actual patterns of variation and evolutionary patterns among populations and less about classification. Some scientists point to three discoveries. Firstly, African populations exhibit greater genetic diversity and less linkage disequilibrium because of their long history. Secondly, genetic similarity is directly correlated with geographic proximity. Lastly, some loci reflect selection in response to environmental gradients. Therefore, some argue, human racial groups do not appear to be distinct ethnic groups.

Franz Boas

Franz Boas (1858–1942) was a German American anthropologist and has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". Professor of anthropology at Columbia University from 1899, Boas made significant contributions withinanthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

, more specifically, physical anthropology, linguistics

Linguistics is the science, scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure ...

, archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

, and cultural anthropology. His work put an emphasis on cultural and environmental effects on people to explain their development into adulthood and evaluated them in concert with human biology and evolution. This encouraged academics to break away from static taxonomical classifications of race. It is said that before Boas, anthropology was the study of race, and after Boas, anthropology was the study of culture.

The 20th-century criticism of racial anthropology was significantly based on Boas and his school. Beginning in 1920, he strongly favoured the influence of social environment over heritability. As a reaction to the rise of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and its prominent espousing of racist ideologies in the 1930s, there was an outpouring of popular works by scientists criticizing the use of race to justify the politics of "superiority" and "inferiority". An influential work in this regard was the publication of ''We Europeans: A Survey of "Racial" Problems'' by Julian Huxley and A. C. Haddon in 1935, which sought to show that population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as Adaptation (biology), adaptation, ...

allowed for only a highly limited definition of race at best. Another popular work during this period, "The Races of Mankind" by Ruth Benedict

Ruth Fulton Benedict (June 5, 1887 – September 17, 1948) was an American anthropologist and folklorist.

She was born in New York City, attended Vassar College, and graduated in 1909. After studying anthropology at the New School of Social Re ...

and Gene Weltfish, argued that though there were some extreme racial differences, they were primarily superficial, and in any case did not justify political action.

Julian Huxley and A. C. Haddon

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (1887–1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, humanist, internationalist, and the first director of UNESCO. After returning to England from a tour of the United States in 1924, Huxley wrote a series of articles for the ''Spectator'' which he expressed his belief in the drastic differences between "negros" and "whites".Barkan, Elazar. The Retreat of Scientific Racism. New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1992. He believed that the color of "blood" – percentage of 'white' and 'black' blood – that a person had would determine a person's mental capacity, moral probity, and social behavior. "Blood" also determined how individuals should be treated by society. He was a proponent of racial inequality and segregation. By 1930, Huxley's ideas on race and inherited intellectual capacity of human groups became more liberal. By the mid-1930s, Huxley was considered one of the leadingantiracist

Anti-racism encompasses a range of ideas and political actions which are meant to counter racial prejudice, systemic racism, and the oppression of specific racial groups. Anti-racism is usually structured around conscious efforts and deliberate a ...

and committed much of his time and efforts into publicizing the fight against Nazism.

Alfred Cort Haddon (1855–1940) was a British anthropologist and ethnologist.

In 1935, Huxley and A. C. Haddon wrote, ''We Europeans'', which greatly popularized the struggle against racial science and attacked the Nazis' abuse of science to promote their racial theories. Although they argued that 'any biological arrangement of the types of European man is still largely a subjective process', they proposed that humankind could be divided up into "major" and "minor subspecies". They believed that races were a classification based on hereditary traits but should not by nature be used to condemn or deem inferior to another group. Like most of their peers, they continued to maintain a distinction between the social meaning of race and the scientific study of race. From a scientific standpoint, they were willing to accept that concepts of superiority and inferiority did not exist, but from a social standpoint, they continued to believe that racial differences were significant. For example, they argued that genetic differences between groups were functionally important for certain jobs or tasks.

Carleton Coon

In 1939, Coon published '' The Races of Europe'', in which he concluded:The Races of Europe by Carleton Coon 1939(Hosted by the Society for Nordish Physical Anthropology) #The Caucasian race is of dual origin consisting of Upper Paleolithic (mixture of ''

Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

'' and '' Neanderthals'') types and Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

(purely ''Homo sapiens'') types.

#The Upper Paleolithic peoples are the truly indigenous peoples of Europe.

#Mediterraneans invaded Europe in large numbers during the Neolithic period and settled there.

#The racial situation in Europe today may be explained as a mixture of Upper Paleolithic survivors and Mediterraneans.

#When reduced Upper Paleolithic survivors and Mediterraneans mix, then occurs the process of dinarization, which produces a hybrid with non-intermediate features.

#The Caucasian race encompasses the regions of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth descr ...

, the Near East, North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, and the Horn of Africa.

#The Nordic race is part of the Mediterranean racial stock, being a mixture of Corded and Danubian Mediterraneans.

In 1962, Coon also published ''The Origin of Races'', wherein he offered a definitive statement of the polygenist

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

view. He also argued that human fossils could be assigned a date, a race, and an evolutionary grade. Coon divided humanity into five races and believed that each race had ascended the ladder of human evolution at different rates.

Since Coon followed the traditional methods of physical anthropology, relying on morphological characteristics, and not on the emerging genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

to classify humans, the debate over ''Origin of Races'' has been "viewed as the last gasp of an outdated scientific methodology that was soon to be supplanted." In today's anthropology, Coon's theories on races are considered pseudoscientific.

Ashley Montagu

Montague Francis Ashley Montagu (1905–1999) was a British-American anthropologist. In 1942, he made a strong effort to have the word "race" replaced with " ethnic group" by publishing his book, ''Man's Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race''. He was also selected to draft the initial 1950 UNESCO Statement on Race. Montagu would later publish ''An Introduction to Physical Anthropology'', a comprehensive treatise on human diversity. In doing so, he sought to provide a firmer scientific framework through which to discuss biological variation among populations.UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

) was established November 16, 1945, in the wake of the genocide of Nazism. The UNESCO 1945 constitution declared that, "The great and terrible war which now has ended was made possible by the denial of the democratic principles of the dignity, equality and mutual respect of men, and by the propagation, in their place, through ignorance and prejudice, of the doctrine of the inequality of men and races." Between 1950 and 1978 the UNESCO issued five statements on the issue of race.

The first of the UNESCO statements on race was "The Race Question

The Race Question is the first of four UNESCO statements about issues of race. It was issued on 18 July 1950 following World War II and Nazi racism to clarify what was scientifically known about race, and as a moral condemnation of racism.< ...

" and was issued on July 18, 1950. The statement included both a rejection of a scientific basis for theories of racial hierarchies and a moral condemnation of racism. Its first statement suggested in particular to "drop the term 'race' altogether and speak of 'ethnic groups

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

, which proved to be controversial. The 1950 statement was most concerned with dispelling the notion of race as species. It did not reject the idea of a biological basis to racial categories. Instead it defined the concept of race in terms as a population defined by certain anatomical and physiological characteristics as being divergent from other populations; it gives the examples of the Caucasian

Caucasian may refer to:

Anthropology

*Anything from the Caucasus region

**

**

** ''Caucasian Exarchate'' (1917–1920), an ecclesiastical exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Caucasus region

*

*

*

Languages

* Northwest Caucasian l ...

, Mongoloid

Mongoloid () is an obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. In the past, other terms ...

and Negroid

Negroid (less commonly called Congoid) is an obsolete racial grouping of various people indigenous to Africa south of the area which stretched from the southern Sahara desert in the west to the African Great Lakes in the southeast, but also to i ...

races. The statements maintain that there are no "pure races" and that biological variability was as great within any race as between races. It argued that there is no scientific basis for believing that there are any innate differences in intellectual, psychological or emotional potential among races.

The statement was drafted by Ashley Montagu

Montague Francis Ashley-Montagu (June 28, 1905November 26, 1999) — born Israel Ehrenberg — was a British-American anthropologist who popularized the study of topics such as race and gender and their relation to politics and development. He ...

and endorsed by some of the leading researchers of the time, in the fields of psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between ...

, biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

, cultural anthropology and ethnology

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology). ...

. The statement was endorsed by Ernest Beaglehole, Juan Comas, L. A. Costa Pinto, Franklin Frazier

Edward Franklin Frazier (; September 24, 1894 – May 17, 1962), was an American sociologist and author, publishing as E. Franklin Frazier. His 1932 Ph.D. dissertation was published as a book titled ''The Negro Family in the United States'' (1 ...

, sociologist specialised in race relations studies, Morris Ginsberg, founding chairperson of the British Sociological Association, Humayun Kabir

Humayun Kabir (1906-1969) was an Indian educationist and politician. He was also a poet, essayist and novelist in the Bengali-language. He was also a renowned political thinker. He was educated at Exeter College, Oxford and graduated in 1931. ...

, writer, philosopher and Education Minister of India twice, Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss (, ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair of Social An ...

, one of the founders of ethnology

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology). ...

and leading theorist of structural anthropology, and Ashley Montagu

Montague Francis Ashley-Montagu (June 28, 1905November 26, 1999) — born Israel Ehrenberg — was a British-American anthropologist who popularized the study of topics such as race and gender and their relation to politics and development. He ...

, anthropologist and author of '' The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity'', who was the rapporteur

A rapporteur is a person who is appointed by an organization to report on the proceedings of its meetings. The term is a French-derived word.

For example, Dick Marty was appointed ''rapporteur'' by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Eur ...

.

As a result of a lack of representation of physical anthropologists in the drafting committee the 1950 publication was criticized by biologists and physical anthropologists for confusing the biological and social senses of race and for going beyond the scientific facts, although there was a general agreement about the statement's conclusions.

UNESCO assembled a new committee with better representation of the physical sciences and drafted a new statement released in 1951. The 1951 statement, published as " The Race Concept", focused on race as a biological heuristic that could serve as the basis for evolutionary studies of human populations. It considered the existing races to be the result of such evolutionary processes throughout human history. It also maintained that "equality of opportunity and equality in law in no way depend, as ethical principles, upon the assertion that human beings are in fact equal in endowment."

As the 1950 and 1951 statements generated considerable attention, in 1964 a new commission was formed to draft a third statement titled " Proposals on the Biological Aspects of Race". According to Michael Banton

Michael Parker Banton CMG, FRAI (8 September 1926 – 22 May 2018) was a British social scientist, known primarily for his publications on racial and ethnic relations. He was also the first editor of ''Sociology'' (1966-1969).

Academic contrib ...

(2008), this statement broke more clearly with the notion of race-as-species than the previous two statements, declaring that almost any genetically differentiated population could be defined as a race. The statement stated that "Different classifications of mankind into major stocks, and of those into more restricted categories (races, which are groups of populations, or single populations) have been proposed on the basis of hereditary physical traits. Nearly all classifications recognise at least three major stocks" and "There is no national, religious, geographic, linguistic or cultural group which constitutes a race ipso facto; the concept of race is purely biological." It concluded with "The biological data given above stand in open contradiction to the tenets of racism. Racist theories can in no way pretend to have any scientific foundation."

The 1950, '51 and '64 statements focused on dispelling the scientific foundations for racism but did not consider other factors contributing to racism. For this reason, in 1967 a new committee was assembled, including representatives of the social sciences (sociologists, lawyers, ethnographers and geneticists), to draft a statement "covering the social, ethical and philosophical aspects of the problem". This statement was the first to provide a definition of racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonis ...

: "antisocial beliefs and acts which are based upon the fallacy that discriminatory intergroup relations are justifiable on biological grounds". The statement continued to denounce the many negative social effects of racism.

In 1978 the general assembly of the UNESCO considered the four previous statements and published a collective " Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice". This declaration included Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

as one of the examples of racism, an inclusion which caused South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

to step out of the assembly. It declared that a number of public policies and laws needed to be implemented. It stated that:

* "All human beings belong to a single species."

**"All peoples of the world possess equal faculties for attaining the highest level in intellectual, technical, social, economic, cultural and political development."

**"The differences between the achievements of the different peoples are entirely attributable to geographical, historical, political, economic, social and cultural factors."

**"Any theory which involves the claim that racial or ethnic groups are inherently superior or inferior, thus implying that some would be entitled to dominate and eliminate others, presumed to be inferior, or which bases value judgements on racial differentiation, has no scientific foundation and is contrary to the moral and ethical principles of humanity."

Criticism of racial studies (1930s–1980s)

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss (, ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair of Social An ...

' ''Race and History'' (UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

, 1952) was another critique of the biological "race" notion, arguing in favor of cultural relativism. Lévi-Strauss argued that when comparatively ranking cultures, the culture of the person performing the ranking would naturally decide which values and ideas are prioritized. Lévi-Strauss compared this to special relativity

In physics, the special theory of relativity, or special relativity for short, is a scientific theory regarding the relationship between space and time. In Albert Einstein's original treatment, the theory is based on two postulates:

# The laws ...

, suggesting that each observer's frame of reference, their culture, appeared to them to be stationary, while the others' cultures appeared to be moving only in relation to an outside frame of reference. Lévi-Strauss cautioned against focusing on specific differences, such as which race was first to develop a specific technology in isolation, as he believed this would create a simplistic and warped view of humanity. Instead Lévi-Strauss instead advocated looking at why these developments were made in context, and what problems they addressed.

In his 1984 article in ''Essence

Essence ( la, essentia) is a polysemic term, used in philosophy and theology as a designation for the property or set of properties that make an entity or substance what it fundamentally is, and which it has by necessity, and without which it ...

'' magazine, "On Being 'White' ... and Other Lies", James Baldwin reads the history of racialization

In sociology, racialization or ethnicization is a political process of ascribing ethnic or racial identities to a relationship, social practice, or group that did not identify itself as such. Racialization or ethnicization often arises out of th ...