Historical models of the Solar System on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The historical models of the

The historical models of the

Anaximander, around 560 BCE, was the first to conceive a mechanical model of the world. In his model, the Earth floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything. Its curious shape is that of a cylinder with a height one-third of its diameter. The flat top forms the inhabited world, which is surrounded by a circular oceanic mass.

At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the

Anaximander, around 560 BCE, was the first to conceive a mechanical model of the world. In his model, the Earth floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything. Its curious shape is that of a cylinder with a height one-third of its diameter. The flat top forms the inhabited world, which is surrounded by a circular oceanic mass.

At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the

Around 400 BCE, Pythagoras' students believed the motion of planets is caused by an out-of-sight "fire" at the centre of the universe (not the Sun) that powers them, and Sun and Earth orbit that ''Central Fire'' at different distances. The Earth's inhabited side is always opposite to the Central Fire, rendering it invisible to people. So, the Earth rotates around itself synchronously with a daily orbit around that Central Fire, while the Sun revolves it yearly in a higher orbit. That way, the inhabited side of Earth faces the Sun once every 24 hours. They also claimed that the Moon and the planets orbit the Earth. This model is usually attributed to

Around 400 BCE, Pythagoras' students believed the motion of planets is caused by an out-of-sight "fire" at the centre of the universe (not the Sun) that powers them, and Sun and Earth orbit that ''Central Fire'' at different distances. The Earth's inhabited side is always opposite to the Central Fire, rendering it invisible to people. So, the Earth rotates around itself synchronously with a daily orbit around that Central Fire, while the Sun revolves it yearly in a higher orbit. That way, the inhabited side of Earth faces the Sun once every 24 hours. They also claimed that the Moon and the planets orbit the Earth. This model is usually attributed to

Eudoxus of Cnidus, student of Plato in around 380 BCE, introduced a technique to describe the motion of the planets called the ''method of exhaustion''. Eudoxus reasoned that since the distances of the stars, the Moon, the Sun and all known planets do not appear to be changing, they are fixed in a sphere in which the bodies move around the sphere but with a constant radius and the Earth is at the centre of the sphere. To explain the complexity of the movements of the planets, Eudoxus thought they move as if they were attached to a number of concentrical, invisible spheres, every of them rotating around its own and different axis and at different paces.

Eudoxus’ model had twenty-seven homocentric spheres with each sphere explaining a type of observable motion for each celestial object. Eudoxus assigns one sphere for the fixed stars which is supposed to explain their daily movement. He assigns three spheres to both the Sun and the Moon with the first sphere moving in the same manner as the sphere of the fixed stars. The second sphere explains the movement of the Sun and the Moon on the ecliptic plane. The third sphere was supposed to move on a “latitudinally inclined” circle and explain the latitudinal motion of the Sun and the Moon in the cosmos. Four spheres were assigned to Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, the only known planets at that time. The first and second spheres of the planets moved exactly like the first two spheres of the Sun and the Moon. According to Simplicius, the third and fourth sphere of the planets were supposed to move in a way that created a curve known as a

Eudoxus of Cnidus, student of Plato in around 380 BCE, introduced a technique to describe the motion of the planets called the ''method of exhaustion''. Eudoxus reasoned that since the distances of the stars, the Moon, the Sun and all known planets do not appear to be changing, they are fixed in a sphere in which the bodies move around the sphere but with a constant radius and the Earth is at the centre of the sphere. To explain the complexity of the movements of the planets, Eudoxus thought they move as if they were attached to a number of concentrical, invisible spheres, every of them rotating around its own and different axis and at different paces.

Eudoxus’ model had twenty-seven homocentric spheres with each sphere explaining a type of observable motion for each celestial object. Eudoxus assigns one sphere for the fixed stars which is supposed to explain their daily movement. He assigns three spheres to both the Sun and the Moon with the first sphere moving in the same manner as the sphere of the fixed stars. The second sphere explains the movement of the Sun and the Moon on the ecliptic plane. The third sphere was supposed to move on a “latitudinally inclined” circle and explain the latitudinal motion of the Sun and the Moon in the cosmos. Four spheres were assigned to Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, the only known planets at that time. The first and second spheres of the planets moved exactly like the first two spheres of the Sun and the Moon. According to Simplicius, the third and fourth sphere of the planets were supposed to move in a way that created a curve known as a

Around 280 BCE, Aristarchus of Samos offers the first definite discussion of the possibility of a heliocentric cosmos, and uses the size of the Earth's

Around 280 BCE, Aristarchus of Samos offers the first definite discussion of the possibility of a heliocentric cosmos, and uses the size of the Earth's

accessed 28-II-2007. In Archimedes' own words: However, Aristarchus' views were not widely adopted, and the

Around 210 BCE, Apollonius of Perga shows the equivalence of two descriptions of the apparent retrograde planet motions (assuming the geocentric model), one using eccentrics and another

Around 210 BCE, Apollonius of Perga shows the equivalence of two descriptions of the apparent retrograde planet motions (assuming the geocentric model), one using eccentrics and another  During the period 127 to 141 AD,

During the period 127 to 141 AD,

Around 420 AD

Around 420 AD

During the 16th century

During the 16th century

The heliocentric model was not immediately adopted.

The heliocentric model was not immediately adopted.

In 1609, Johannes Kepler, an advocate of the heliocentric model, using his patron Tycho Brahe's accurate measurements, noticed the inconsistency of a heliocentric model where the Sun is exactly in the centre. Instead Kepler developed a more accurate and consistent model where the Sun is located not in the centre but at one of the two foci of an

In 1609, Johannes Kepler, an advocate of the heliocentric model, using his patron Tycho Brahe's accurate measurements, noticed the inconsistency of a heliocentric model where the Sun is exactly in the centre. Instead Kepler developed a more accurate and consistent model where the Sun is located not in the centre but at one of the two foci of an

The historical models of the

The historical models of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

began during prehistoric periods and are updated to this day. The models of the Solar System throughout history were first represented in the early form of cave markings and drawings, calendars and astronomical symbols. Then books and written records became the main source of information that expressed the way the people of the time thought of the Solar System.

New models of the Solar System are usually built on previous models, thus, the early models are kept track of by intellectuals in astronomy, an extended progress from trying to perfect the geocentric

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

model to eventually using the heliocentric model of the Solar System. The uses of the Solar System model began as a time source to signify particular periods during the year and also a navigation source which is exploited by many leaders from the past.

Astronomers and great thinkers of the past were able to record observations and attempt to formulate a model that accurately interprets the recordings. This scientific method of deriving a model of the Solar System is what enabled progress towards more accurate models to have a better understanding of the Solar System that we are in.

Prehistoric astronomy

Until the twenty-first century, astronomy was generally thought to begin withHipparchus of Nicaea

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

(d. c. 120 BC), who was credited with discovering the precession of the equinoxes

In astronomy, axial precession is a gravity-induced, slow, and continuous change in the orientation of an astronomical body's rotational axis. In the absence of precession, the astronomical body's orbit would show axial parallelism. In partic ...

. Ancient cave paintings that monitor the equinox

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun crosses the Earth's equator, which is to say, appears directly above the equator, rather than north or south of the equator. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise "due east" and se ...

es and solstice

A solstice is an event that occurs when the Sun appears to reach its most northerly or southerly excursion relative to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annually, around June 21 and December 21. In many countr ...

s were found from as early as 40 000 years ago by researchers in the University of Edinburgh and Kent. These events were used as an annual time reference in Çatalhöyük

Çatalhöyük (; also ''Çatal Höyük'' and ''Çatal Hüyük''; from Turkish ''çatal'' "fork" + ''höyük'' "tumulus") is a tell of a very large Neolithic and Chalcolithic proto-city settlement in southern Anatolia, which existed from app ...

during 7000 BCE:

* Summer solstice

*Autumn equinox Autumnal equinox or variations, may refer to:

* September equinox, the autumnal equinox in the Northern Hemisphere

* March equinox, the autumnal equinox in the Southern Hemisphere

Other uses

* Autumnal Equinox Day (Japanese: 秋分の日, ''Shūbu ...

*Winter solstice

The winter solstice, also called the hibernal solstice, occurs when either of Earth's poles reaches its maximum tilt away from the Sun. This happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere (Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the winter ...

* Spring equinox

Jeguès Wolkiewiez found that 122 out of 130 ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

Paleolithic caves she visited were aligned to equinoxes and solstices. The researchers concluded that these were calendar experts who used these astronomical events to know when to begin their rituals. This highlights their knowledge of the Sun and Moon's positioning which is the foundation of formulating a model of the Solar System.

Also, according to NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

, the first cave markings of a lunar cycle

Concerning the lunar month of ~29.53 days as viewed from Earth, the lunar phase or Moon phase is the shape of the Moon's directly sunlit portion, which can be expressed quantitatively using areas or angles, or described qualitatively using the t ...

were made by the Aurignacian Culture in 32 000 BCE. These cave markings are thought of as calendars that helped the people contain the cycles of the Solar System which is a method of keeping track of time. In Lascaux caves, there were many cave drawings in which a dot is in the middle and 11 to 14 dots are drawn around the centre dot which archaeologists date back to as early as 15 000 BCE. Alexander Marshack Alexander Marshack (April 4, 1918 – December 20, 2004) was an American independent scholar and Paleolithic archaeologist. He was born in The Bronx and earned a bachelor's degree in journalism from City College of New York, and worked for many y ...

, Professor of Paleolithic Archaeology at Harvard University's Peabody Museum, concluded that these dots represent lunar cycles.

Early astronomy

Navagraha

Around the 3rd millennium BC,Hindu astrology

Jyotisha or Jyotishya (from Sanskrit ', from ' “light, heavenly body" and ''ish'' - from Isvara or God) is the traditional Hindu system of astrology, also known as Hindu astrology, Indian astrology and more recently Vedic astrology. It is one ...

is developed, based on the Navagraha

Navagraha are nine heavenly bodies and deities that influence human life on Earth according to Hinduism and Hindu astrology. The term is derived from ''nava'' ( sa, नव "nine") and ''graha'' ( sa, ग्रह "planet, seizing, laying hold of, ...

, nine heavenly bodies and deities that influence human life on Earth: the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

, the then known five planets, plus the ascending and descending nodes of the Moon.

The Nebra Sky Disc

The Nebra Sky Disc is a bronze dish with symbols that are interpreted generally as theSun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

or full moon

The full moon is the lunar phase when the Moon appears fully illuminated from Earth's perspective. This occurs when Earth is located between the Sun and the Moon (when the ecliptic longitudes of the Sun and Moon differ by 180°). This means ...

, a lunar crescent

A crescent shape (, ) is a symbol or emblem used to represent the lunar phase in the first quarter (the "sickle moon"), or by extension a symbol representing the Moon itself.

In Hinduism, Lord Shiva is often shown wearing a crescent moon on his ...

, and stars (including a cluster of seven stars interpreted as the Pleiades

The Pleiades (), also known as The Seven Sisters, Messier 45 and other names by different cultures, is an asterism and an open star cluster containing middle-aged, hot B-type stars in the north-west of the constellation Taurus. At a distance ...

). The disc has been attributed to a site in present-day Germany near Nebra, Saxony-Anhalt

Saxony-Anhalt (german: Sachsen-Anhalt ; nds, Sassen-Anholt) is a state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. It covers an area of

and has a population of 2.18 million inhabitants, making it th ...

, and was originally dated by archaeologists to , based on the provenance provided by the looters who found it. Researchers initially suggested the disc is an artefact from the Bronze Age Unetice culture

The Únětice culture or Aunjetitz culture ( cs, Únětická kultura, german: Aunjetitzer Kultur, pl, Kultura unietycka) is an archaeological culture at the start of the Central European Bronze Age, dated roughly to about 2300–1600BC. The epon ...

, although a later dating to the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

has also been proposed.

Firmament

The ancient Hebrews, like all the ancient peoples of the Near East, believed the sky was a solid dome with theSun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

, planets and stars

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by its gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night, but their immense distances from Earth ma ...

embedded in it.

In biblical cosmology

Biblical cosmology is the biblical writers' conception of the cosmos as an organised, structured entity, including its origin, order, meaning and destiny. The Bible was formed over many centuries, involving many authors, and reflects shift ...

, the firmament

In biblical cosmology, the firmament is the vast solid dome created by God during his creation of the world to divide the primal sea into upper and lower portions so that the dry land could appear. The concept was adopted into the subsequent ...

is the vast solid dome created by God during his creation of the world to divide the primal sea into upper and lower portions so that the dry land could appear.

Babylonian interpretation

Babylonians thought the universe revolved around heaven and Earth. They used methodological observations of the patterns of planets and stars movements to predict future possibilities such aseclipses

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when an astronomical object or spacecraft is temporarily obscured, by passing into the shadow of another body or by having another body pass between it and the viewer. This alignment of three ce ...

. Babylonians were able to make use of periodic appearances of the Moon to generate a time source - a calendar. This was developed as the appearance of the full moon was visible every month. The 12 months came about by dividing the ecliptic into 12 equal segments of 30 degrees and were given zodiacal constellation names which were later used by the Greeks.

Chinese theories

The Chinese had multiple theories of the structure of the universe. The first theory is the ''Gaitian'' (celestial lid) theory, mentioned in an old mathematical text called ''Zhou bei suan jing'' in 100 BCE, in which the Earth is within the heaven, where the heaven acts as a dome or a lid. The second theory is the ''Huntian'' (Celestial sphere) theory during 100 BCE. This theory claims that the Earth floats on the water that the Heaven contains, which was accepted as the default theory until 200 AD. The ''Xuanye'' (Ubiquitous darkness) theory attempts to simplify the structure by implying that the Sun, Moon and the stars are just a highly dense vapour that floats freely in space with no periodic motion.Greek astronomy

Since 600 BCE, Greek thinkers noticed the periodic fashion of the Solar System (then regarded as the "wholeuniverse

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. ...

") but, like their contemporaries, they were puzzled about the forward and retrograde motion of the planets, the "wanderer stars", long taken as heavenly deities. Many theories were announced during this period, mostly purely speculative, but progressively supported by geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ...

.

Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

alleged to have predicted the solar eclipse of 586 BCE. Around 475 BCE, Parmenides claimed that the universe is spherical and moonlight is a reflection of sunlight. Shortly after, circa 450 BCE, Anaxagoras suggested that the Moon is rocky

''Rocky'' is a 1976 American sports drama film directed by John G. Avildsen and written by and starring Sylvester Stallone. It is the first installment in the ''Rocky'' franchise and stars Talia Shire, Burt Young, Carl Weathers, and Burge ...

, thus opaque

Opacity or opaque may refer to:

* Impediments to (especially, visible) light:

** Opacities, absorption coefficients

** Opacity (optics), property or degree of blocking the transmission of light

* Metaphors derived from literal optics:

** In lingu ...

, and closer to the Earth than the Sun, giving a correct explanation of eclipses. To him, comets are formed by collisions of planets and that the motion of planets is controlled by the ''nous'' (mind).

Anaximander cosmology

occlusion

Occlusion may refer to:

Health and fitness

* Occlusion (dentistry), the manner in which the upper and lower teeth come together when the mouth is closed

* Occlusion miliaria, a skin condition

* Occlusive dressing, an air- and water-tight trauma ...

of that hole. The diameter of the solar wheel was twenty-seven times that of the Earth (or twenty-eight, depending on the sources) and the lunar wheel, whose fire was less intense, eighteen (or nineteen) times. Its hole could change shape, thus explaining lunar phases. The stars and the planets, located closer, followed the same model.

Anaximander was the first astronomer to consider the Sun as a huge object, and consequently, to realize how far from Earth it might be, and the first to present a system where the celestial bodies turned at different distances.

Pythagorean astronomical system

Philolaus

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pyt ...

.

This model is the first one that depicts a moving Earth, simultaneously self-rotating and orbiting around an external point (but not around the Sun), thus not being geocentrical, contrary to common intuition

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledge; unconscious cognition; ...

.

Due to philosophical concerns about the number 10 (a "perfect number

In number theory, a perfect number is a positive integer that is equal to the sum of its positive divisors, excluding the number itself. For instance, 6 has divisors 1, 2 and 3 (excluding itself), and 1 + 2 + 3 = 6, so 6 is a perfect number.

...

" for the Pythagorians), they also added a tenth "hidden body" or Counter-Earth

The Counter-Earth is a hypothetical body of the Solar System that orbits on the other side of the solar system from Earth.

A Counter-Earth or ''Antichthon'' ( el, Ἀντίχθων) was hypothesized by the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Philol ...

(''Antichthon''), always in the opposite side of the invisible Central Fire and therefore also invisible from Earth.

Platonic geocentrism

Around 360 BCE whenPlato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

wrote in his ''Timaeus Timaeus (or Timaios) is a Greek name. It may refer to:

* ''Timaeus'' (dialogue), a Socratic dialogue by Plato

*Timaeus of Locri, 5th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher, appearing in Plato's dialogue

*Timaeus (historian) (c. 345 BC-c. 250 BC), Greek ...

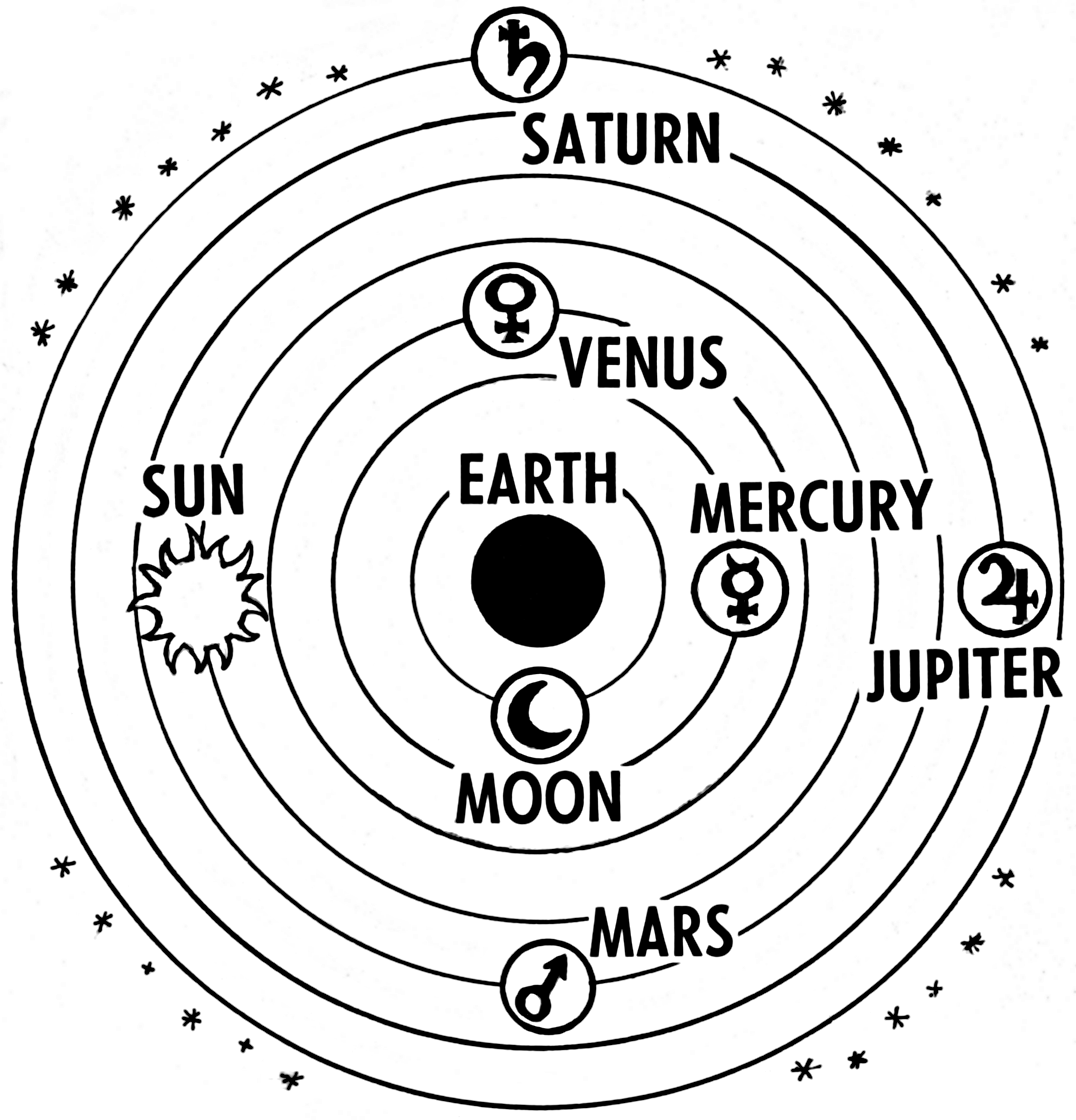

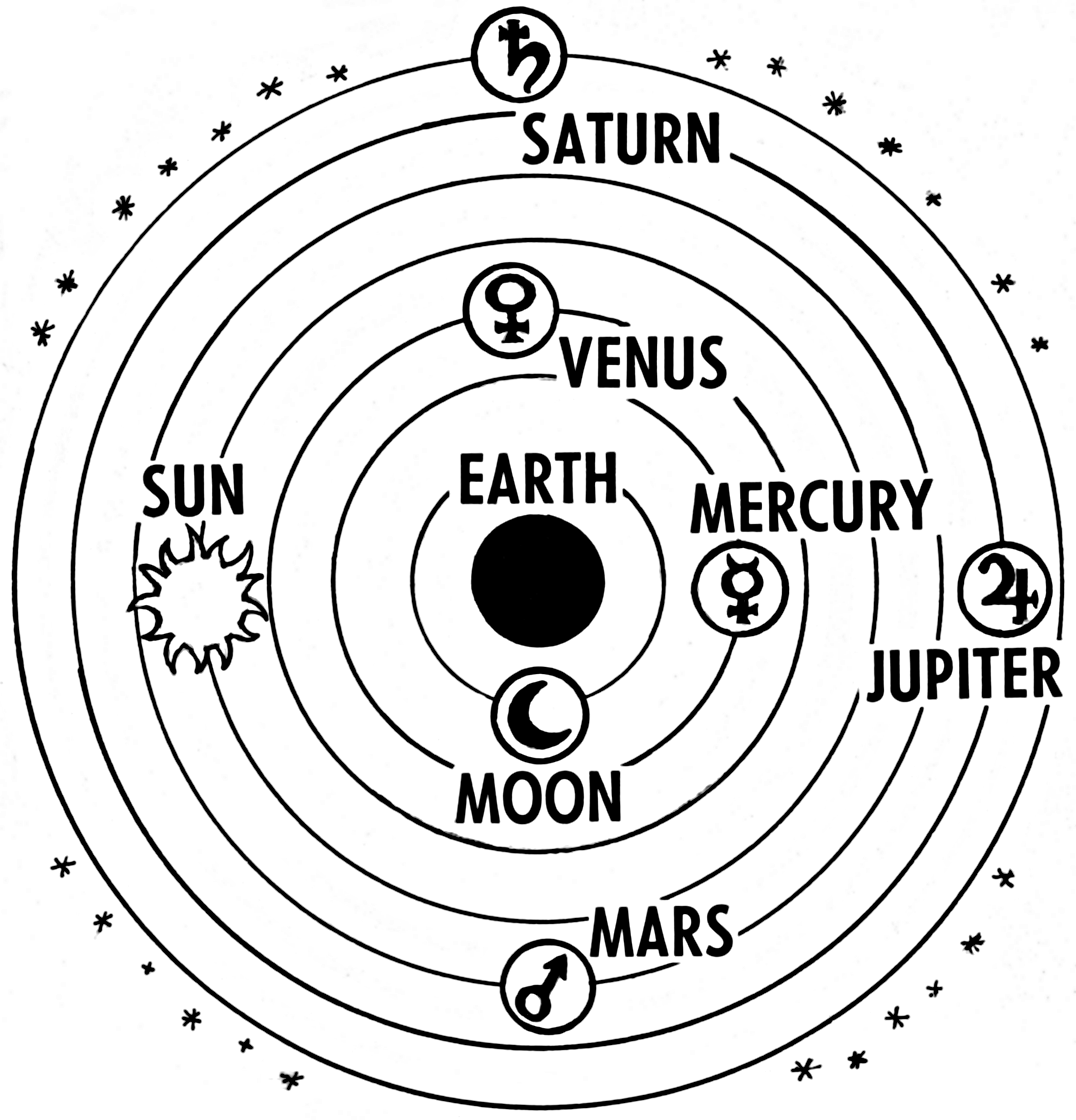

'' his idea to account for the motions. He claimed that circles and spheres were the preferred shape of the universe and that the Earth was at the centre and the stars forming the outermost shell, followed by planets, the Sun and the Moon. This is the so-called geocentric model.

In Plato's cosmogony, the demiurge

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the demiurge () is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. The Gnostics adopted the term ''demiurge'' ...

gave the primacy to the motion of Sameness and left it undivided; but he divided the motion of Difference in six parts, to have seven unequal circles. He prescribed these circles to move in opposite directions, three of them with equal speeds, the others with unequal speeds, but always in proportion. These circles are the orbits of the heavenly bodies: the three moving at equal speeds are the Sun, Venus and Mercury, while the four moving at unequal speeds are the Moon, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. The complicated pattern of these movements is bound to be repeated again after a period called a 'complete' or 'perfect' year.

So, Plato arranged these celestial orbs in the order (outwards from the center): Moon, Sun, Venus, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and fixed stars, with the fixed stars located on the celestial sphere. However, this did not suffice to explain the observed planetary motion.

Concentric spheres

Eudoxus of Cnidus, student of Plato in around 380 BCE, introduced a technique to describe the motion of the planets called the ''method of exhaustion''. Eudoxus reasoned that since the distances of the stars, the Moon, the Sun and all known planets do not appear to be changing, they are fixed in a sphere in which the bodies move around the sphere but with a constant radius and the Earth is at the centre of the sphere. To explain the complexity of the movements of the planets, Eudoxus thought they move as if they were attached to a number of concentrical, invisible spheres, every of them rotating around its own and different axis and at different paces.

Eudoxus’ model had twenty-seven homocentric spheres with each sphere explaining a type of observable motion for each celestial object. Eudoxus assigns one sphere for the fixed stars which is supposed to explain their daily movement. He assigns three spheres to both the Sun and the Moon with the first sphere moving in the same manner as the sphere of the fixed stars. The second sphere explains the movement of the Sun and the Moon on the ecliptic plane. The third sphere was supposed to move on a “latitudinally inclined” circle and explain the latitudinal motion of the Sun and the Moon in the cosmos. Four spheres were assigned to Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, the only known planets at that time. The first and second spheres of the planets moved exactly like the first two spheres of the Sun and the Moon. According to Simplicius, the third and fourth sphere of the planets were supposed to move in a way that created a curve known as a

Eudoxus of Cnidus, student of Plato in around 380 BCE, introduced a technique to describe the motion of the planets called the ''method of exhaustion''. Eudoxus reasoned that since the distances of the stars, the Moon, the Sun and all known planets do not appear to be changing, they are fixed in a sphere in which the bodies move around the sphere but with a constant radius and the Earth is at the centre of the sphere. To explain the complexity of the movements of the planets, Eudoxus thought they move as if they were attached to a number of concentrical, invisible spheres, every of them rotating around its own and different axis and at different paces.

Eudoxus’ model had twenty-seven homocentric spheres with each sphere explaining a type of observable motion for each celestial object. Eudoxus assigns one sphere for the fixed stars which is supposed to explain their daily movement. He assigns three spheres to both the Sun and the Moon with the first sphere moving in the same manner as the sphere of the fixed stars. The second sphere explains the movement of the Sun and the Moon on the ecliptic plane. The third sphere was supposed to move on a “latitudinally inclined” circle and explain the latitudinal motion of the Sun and the Moon in the cosmos. Four spheres were assigned to Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, the only known planets at that time. The first and second spheres of the planets moved exactly like the first two spheres of the Sun and the Moon. According to Simplicius, the third and fourth sphere of the planets were supposed to move in a way that created a curve known as a hippopede

In geometry, a hippopede () is a plane curve determined by an equation of the form

:(x^2+y^2)^2=cx^2+dy^2,

where it is assumed that and since the remaining cases either reduce to a single point or can be put into the given form with a rotation. ...

. The hippopede was a way to try and explain the retrograde motions of planets.

Eudoxus emphasised that this is a purely mathematical construct of the model in the sense that the spheres of each celestial body do not exist, it just shows the possible positions of the bodies.

Around 350 BCE Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

, in his chief cosmological teatrise ''De Caelo'' (On the Heavens), modified Eudoxus' model by supposing the spheres were material and crystalline. He was able to articulate the spheres for most planets, however, the spheres for Jupiter and Saturn crossed each other. Aristotle solved this complication by introducing an unrolled sphere in between, increasing the number of spheres needed well above Eudoxus'. Historians are unsure about how many spheres Aristotle thought there were in the cosmos with theories ranging from 43 up to 55.

Aristotle also tried to determine whether the Earth moves and concluded that all the celestial bodies fall towards Earth by natural tendency and since Earth is the centre of that tendency, it is stationary.

Incipient heliocentrism

By 330 BCE,Heraclides of Pontus

Heraclides Ponticus ( grc-gre, Ἡρακλείδης ὁ Ποντικός ''Herakleides''; c. 390 BC – c. 310 BC) was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who was born in Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey, and migrated to Athens. He ...

said that the rotation of the Earth on its axis, from west to east, once every 24 hours, explained the apparent daily motion of the celestial sphere. Simplicius says that Heraclides proposed that the irregular movements of the planets can be explained if the Earth moves while the Sun stays still, but these statements are disputed.

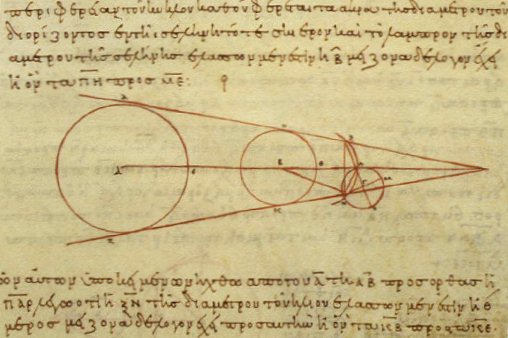

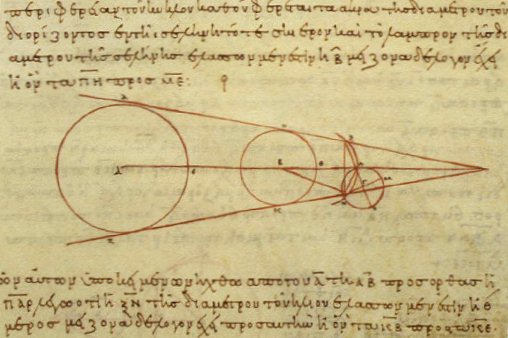

Around 280 BCE, Aristarchus of Samos offers the first definite discussion of the possibility of a heliocentric cosmos, and uses the size of the Earth's

Around 280 BCE, Aristarchus of Samos offers the first definite discussion of the possibility of a heliocentric cosmos, and uses the size of the Earth's shadow

A shadow is a dark area where light from a light source is blocked by an opaque object. It occupies all of the three-dimensional volume behind an object with light in front of it. The cross section of a shadow is a two-dimensional silhouette, ...

on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

to estimate the Moon's orbital radius at 60 Earth radii, and its physical radius as one-third that of the Earth. He made an inaccurate attempt to measure the distance to the Sun, but sufficient to assert that the Sun is bigger than Earth and it is further away than the Moon. So the minor body, the Earth, must orbit the major one, the Sun, and not the opposite.

Following the heliocentric ideas of Aristarcus (but not explicitly supporting them), around 250 BCE Archimedes in his work ''The Sand Reckoner

''The Sand Reckoner'' ( el, Ψαμμίτης, ''Psammites'') is a work by Archimedes, an Ancient Greek mathematician of the 3rd century BC, in which he set out to determine an upper bound for the number of grains of sand that fit into the unive ...

'' computes the diameter of the universe centered around the Sun to be about 1014 stadia

Stadia may refer to:

* One of the plurals of stadium, along with "stadiums"

* The plural of stadion, an ancient Greek unit of distance, which equals to 600 Greek feet (''podes'').

* Stadia (Caria), a town of ancient Caria, now in Turkey

* Stadi ...

(in modern units, about 2 light years, , ).Archimedes, The Sand Reckoner 511 R U, by Ilan Vardiaccessed 28-II-2007. In Archimedes' own words: However, Aristarchus' views were not widely adopted, and the

geocentric

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

notion will remain for centuries.

Further developments

deferent and epicycle

In the Hipparchian, Ptolemaic, and Copernican systems of astronomy, the epicycle (, meaning "circle moving on another circle") was a geometric model used to explain the variations in speed and direction of the apparent motion of the Moon, S ...

s. The latter will be a key feature for future models. The epicycle is described as a small orbit within a greater one, called the ''deferent'': as a planet orbits the Earth, it also orbits the original orbit, so its trajectory ressembles an epitrochoid

In geometry, an epitrochoid ( or ) is a roulette traced by a point attached to a circle of radius rolling around the outside of a fixed circle of radius , where the point is at a distance from the center of the exterior circle.

The parametric ...

, as shown in the illustration at left. This could explain how the planet seems to move as viewed from Earth.

In the following century, measures of sizes and distances of the Earth and the Moon are improved. Around 200 BCE Eratosthenes determines that the radius of the Earth is roughly 6,400 km. Circa 150 BCE Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

uses parallax to determine that the distance to the Moon is roughly 380,000 km.

The work of Hipparchus about the Earth-Moon system was so accurate that he could forecast solar and lunar eclipses for the next six centuries. Also, he discovers the precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In oth ...

of the equinox

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun crosses the Earth's equator, which is to say, appears directly above the equator, rather than north or south of the equator. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise "due east" and se ...

es, and compiles a star catalog

A star catalogue is an astronomical catalogue that lists stars. In astronomy, many stars are referred to simply by catalogue numbers. There are a great many different star catalogues which have been produced for different purposes over the years, ...

of about 850 entries.

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

deduced that the Earth is spherical based on the fact that not everyone records the solar eclipse at the same time and that observers from the North can not see the Southern stars. Ptolemy attempted to resolve the Planetary motion dilemma in which the observations were not consistent with the perfect circular orbits of the bodies. Ptolemy adopted the Apollonius' epicycles as solution. Ptolemy emphasised that the epicycle motion does not apply to the Sun. His main contribution to the model was the equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

points.

Ptolomy's work '' Almagest'' cimented the geocentric model in the West, and it remained the most authoritative text on astronomy for more than 1,500 years. His methods were accurate enough to keep them largely undisputed.

Medieval Astronomy

Capellas' astronomical model

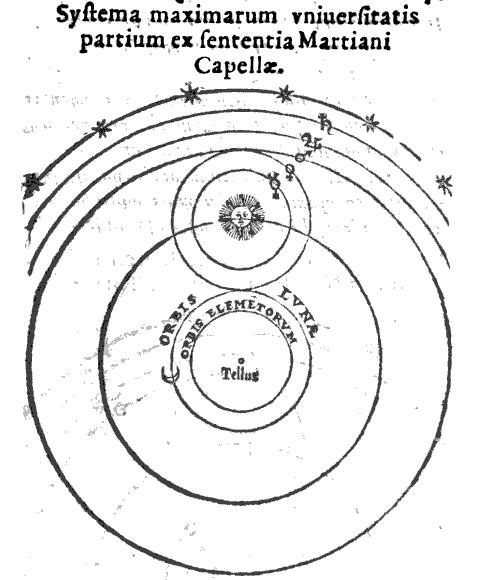

Martianus Capella

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (fl. c. 410–420) was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writer of late antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education. He was a nati ...

describes a modified geocentric model, in which the Earth is at rest in the center of the universe and circled by the Moon, the Sun, three planets and the stars, while Mercury and Venus circle the Sun.

His model was not widely accepted, despite of his authority; he was one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin "free" and "art or principled practice") is the traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term '' art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically th ...

, the trivium

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium is implicit in ''De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii'' ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but t ...

(grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domain ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premise ...

, and rhetoric) and the quadrivium

From the time of Plato through the Middle Ages, the ''quadrivium'' (plural: quadrivia) was a grouping of four subjects or arts—arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—that formed a second curricular stage following preparatory work in the ...

( arithmetic, geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

), that structured early medieval education. Nonetheless, his single encyclopedic work, '' De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii'' ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury"), also called ''De septem disciplinis'' ("On the seven disciplines") was read, taught, and commented upon throughout the early Middle Ages and shaped European education during the early medieval period and the Carolingian renaissance.

This model implies some knowledge about the transits of Mercury

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Mercury across the Sun takes place when the planet Mercury passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet. During a transit, Mercury appears as a tiny black dot moving across the Sun as the planet obs ...

and Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

in front of the Sun, and the fact they pass also behind it periodically, which cannot be explained with Ptolemy's model. But it is unclear how that knowledge could be achieved by that times, due to the difficult to see these transits at naked eye; indeed, there is no evidence that any ancient culture knew of the transits.

Alternatively, as seen from Earth, Mercury never departs from the Sun, neither East nor West, more than 28° and Venus no more than 47°, facts both known from antiquity that also could not be explained by Ptolomy. So it could be inferred that they orbit the Sun, and hence, there should be these transits.

Islamic astronomy

TheIslamic golden age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

period in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

, picking off from Ptolemy's work, had more accurate measurements taken followed by interpretations. In 1021 A.D, Ibn Al Haytham adjusted Ptolemy's geocentric model to his specialty in optics in his book ''Al-shukuk 'ata Batlamyus'' which translates to "Doubts about Ptolemy". Ibn al-Haytham claimed that the epicycles Ptolemy introduced are inclined planes, not in a flat motion which settled further conflicting disputes. However, Ibn Al Haytham agreed with the Earth being in the centre of the Solar System at a fixed position.

Nasir al-Din, during the 13th century, was able to combine two possible methods for a planet to orbit and as a result, derived a rotational aspect of planets within their orbits. Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

arrived to the same conclusion in the 16th century. Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ansari known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir ( ar, ابن الشاطر; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as ''muwaqqit'' (موقت, religious t ...

, during the 14th century, in an attempt to resolve Ptolemy's inconsistent lunar theory, applied a double epicycle model to the Moon which reduced the predicted displacement of the Moon from the Earth. Copernicus also arrived at the same conclusion in the 16th century.

Chinese Astronomy

In 1051, Shen Kua, a Chinese scholar inapplied mathematics

Applied mathematics is the application of mathematical methods by different fields such as physics, engineering, medicine, biology, finance, business, computer science, and industry. Thus, applied mathematics is a combination of mathemati ...

, rejected the circular planetary motion. He substituted it with a different motion described by the term ‘willow-leaf’. This is when a planet has a circular orbit but then it encounters another small circular orbit within or outside the original orbit and then returns to its original orbit which is demonstrated by the figure on the right.

Renaissance

Copernicus's Heliocentric Model

During the 16th century

During the 16th century Nicholas Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

, in reflecting about Ptolemy and Aristoles interpretations of the Solar System, believed that all the orbits of the planets and Moon must be a perfect uniform circular motion despite the observations showing the complex retrograde motion. Copernicus introduced a new model which was consistent with the observations and allowed for perfect circular motion. This is known as the Heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

where the Sun is placed at the centre of the universe (hence, the Solar System) and the Earth is, like all the other planets, orbiting it. The heliocentric model also resolved the varying brightness of planets problem. Copernicus also supported the spherical Earth theory with the idea that nature prefers spherical limits which are seen in the Moon, the Sun, and also the orbits of planets. Copernicus furthermore believed that the universe had a spherical limit. Copernicus contributed further to practical Astronomy by producing advanced techniques of observations and measurements and providing instructional procedure.

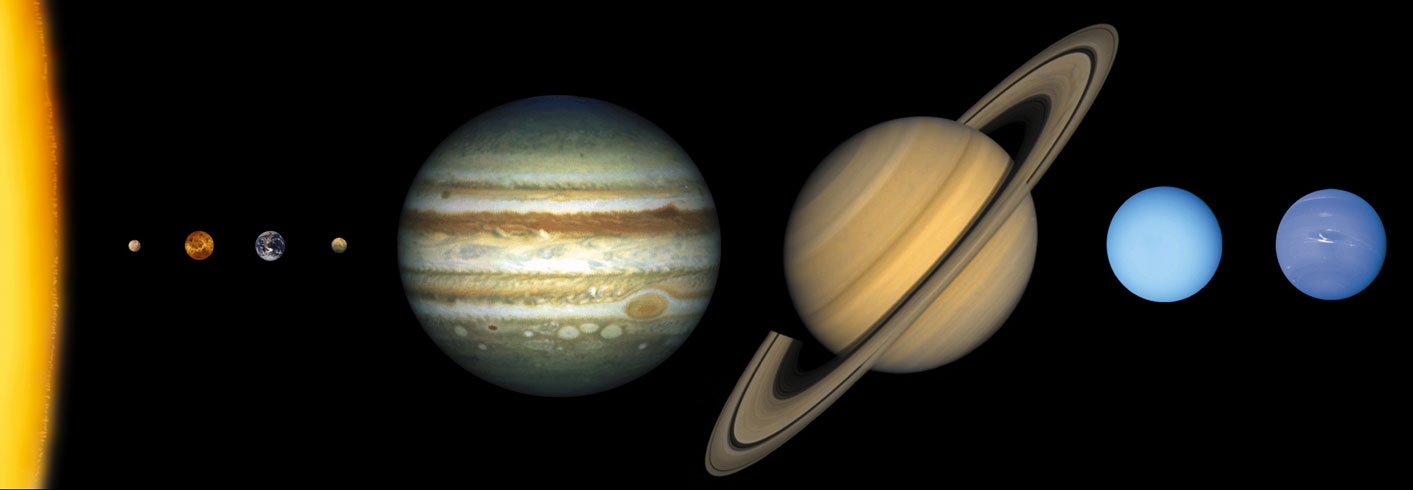

The heliocentric model implies that the Earth is also a planet, the third from the Sun after Mercury and Venus, and before Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. And also implicitly, that planets are "worlds", like Earth is, not "stars". But the Moon still orbits the Earth.

The Tychonic system

Conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

along to numerous observational, philosophical and religious concerns prevented it for more than a century.

In 1588 Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

publishes his own Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the Universe published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" bene ...

, a blend between the Ptolomy's classical geocentric model and Copernicus' heliocentric model, in which the Sun and the Moon revolve around the Earth, in the center of universe, and all other planets revolve around the Sun. It was an attempt to conciliate his religious beliefs with heliocentrism. This was the so-called geoheliocentric model, and it was adopted by some astronomers during the geocentrism vs heliocentrism disputes.

Kepler's model

In 1609, Johannes Kepler, an advocate of the heliocentric model, using his patron Tycho Brahe's accurate measurements, noticed the inconsistency of a heliocentric model where the Sun is exactly in the centre. Instead Kepler developed a more accurate and consistent model where the Sun is located not in the centre but at one of the two foci of an

In 1609, Johannes Kepler, an advocate of the heliocentric model, using his patron Tycho Brahe's accurate measurements, noticed the inconsistency of a heliocentric model where the Sun is exactly in the centre. Instead Kepler developed a more accurate and consistent model where the Sun is located not in the centre but at one of the two foci of an elliptic orbit

In astrodynamics or celestial mechanics, an elliptic orbit or elliptical orbit is a Kepler orbit with an eccentricity of less than 1; this includes the special case of a circular orbit, with eccentricity equal to 0. In a stricter sense, i ...

.

Kepler derived the three laws of planetary motion which changed the model of the Solar System and the orbital path of planets. These three laws of planetary motion are:

# All planets orbit the Sun in elliptical orbits (image on the left) and not perfectly circular orbits.

# The radius vector joining the planet and the Sun has an equal area in equal periods.

# The square of the period of the planet (one revolution around the Sun) is proportional to the cube of the average distance from the Sun.

In modern notation,

:

where ''a'' is the radius of the orbit, ''T'' is the period, ''G'' is the gravitational constant and ''M'' is the mass of the Sun. The third law explains the periods that occur during the year which relates the distance between the Earth and the Sun.

Along with unprecedent accuracy, the Keplerian model also allows put the Solar System into scale. If a reliable measure between planetary bodies would be taken, the whole size of the system could be computed. By this time, the Solar System started to be conceived as something smaller than the rest of the universe. (Yet, up to 1596 Kepler himself still believed in the sphere of fixed stars, as it was illustrated in his book ''Mysterium Cosmopgraphicum''.)

Galileo's discoveries

With the help of thetelescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observ ...

providing a closer look into the sky, Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He wa ...

proved the most part of the heliocentric model of the Solar System. Galileo observed the phases of Venus

The phases of Venus are the variations of lighting seen on the planet's surface, similar to lunar phases. The first recorded observations of them are thought to have been telescopic observations by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Although the extreme cr ...

's appearance with the telescope and was able to confirm Kepler's first law of planetary motion and Copernicus's heliocentric model, of which Galileo was an advocate. Galileo claimed that the Solar System is not only made up of the Sun, the Moon and the planets but also comets. By observing movements around Jupiter, Galileo initially thought that these were the actions of stars. However, after a week of observing, he noticed changes in the patterns of motion in which he concluded that they are moons, four moons

A natural satellite is, in the most common usage, an astronomical body that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or small Solar System body (or sometimes another natural satellite). Natural satellites are often colloquially referred to as ''moons'' ...

.

Shortly after, it was proved by Kepler himself that the Jupiter's moons move around the planet the same way planets orbit the Sun, thus making Kepler's laws universal.

Enlightenment to Victorian Era

Newton's interpretation

After all these theories, people still did not know what made the planets orbit the Sun, nor why the Moon tracks the Earth. Until the 17th century whenIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

introduced The Law of Universal Gravitation. He claimed that between any two masses, there is an attractive force between them proportional to the inverse of the distance squared.

:

where m1 is the mass of the Sun and m2 is the mass of the planet, G is the gravitational constant and r is the distance between them.

This theory was able to calculate the force on each planet by the Sun, which consequently, explained the planets elliptical motion.

Derived measurements

In 1672Jean Richer

Jean Richer (1630–1696) was a French astronomer and assistant (''élève astronome'') at the French Academy of Sciences, under the direction of Giovanni Domenico Cassini.

Between 1671 and 1673 he performed experiments and carried out celestial ...

and Giovanni Domenico Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini, also known as Jean-Dominique Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian (naturalised French) mathematician, astronomer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the ...

measure the astronomical unit

The astronomical unit (symbol: au, or or AU) is a unit of length, roughly the distance from Earth to the Sun and approximately equal to or 8.3 light-minutes. The actual distance from Earth to the Sun varies by about 3% as Earth orbits ...

(AU), the mean distance Earth-Sun, to be about 138,370,000 km, (later refined by others up to the current value of 149,597,870 km). This gave for first time ever a well estimated size of the then known Solar System (that is, up to Saturn), following the scale derived from Kepler's third law.

In 1798 Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English natural philosopher and scientist who was an important experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "infl ...

accurately measures the gravitational constant in the laboratory, which allows the mass of the Earth to be derived thru Newton's law of universal gravitation, and hence the masses of all bodies in the Solar System.

New members of the Solar System

Telescopic observations found new moons around Jupiter and Saturn, as well as an impressivering system

A ring system is a disc or ring, orbiting an astronomical object, that is composed of solid material such as dust and moonlets, and is a common component of satellite systems around giant planets. A ring system around a planet is also known as ...

around the latter.

In 1705 Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

asserted that the comet of 1682 is periodical with a highly elongated elliptical orbit around the Sun, and predicts its return in 1757. Johann Palitzsch observed in 1758 the return of the comet that Halley had anticipated. The interference of Jupiter's orbit had slowed the return by 618 days. Parisian astronomer La Caille

Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille (; 15 March 171321 March 1762), formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the 88 constellations. From 1750 to 1754, he studied the sky at the Cape of Goo ...

suggests it should be named "Halley's Comet". Comets became a popular target for astronomers, and were recognized as members of the Solar System.

In 1766 Johann Titius found a numeric progression for planetary distances, published in 1772 by Johann Bode, the so-called Titius-Bode rule.

When in 1781 William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel (; german: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-born British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline ...

discovered a new planet, Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus ( Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars), grandfather of Zeus (Jupiter) and father of ...

, it was found it lies at a distance beyond Saturn that approximately matches that predicted by the Titius-Bode rule.

That rule observed a gap between Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

and Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

void of any known planet. In 1801 Giuseppe Piazzi

Giuseppe Piazzi ( , ; 16 July 1746 – 22 July 1826) was an Italian Catholic priest of the Theatine order, mathematician, and astronomer. He established an observatory at Palermo, now the '' Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo – Giuseppe S ...

discovered Ceres

Ceres most commonly refers to:

* Ceres (dwarf planet), the largest asteroid

* Ceres (mythology), the Roman goddess of agriculture

Ceres may also refer to:

Places

Brazil

* Ceres, Goiás, Brazil

* Ceres Microregion, in north-central Goiás ...

, a body that filled the gap and was regarded as a new planet, and in 1802 Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers

Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers (; ; 11 October 1758 – 2 March 1840) was a German physician and astronomer.

Life and career

Olbers was born in Arbergen, Germany, today part of Bremen, and studied to be a physician at Göttingen (1777–80 ...

discovered Pallas

Pallas may refer to:

Astronomy

* 2 Pallas asteroid

** Pallas family, a group of asteroids that includes 2 Pallas

* Pallas (crater), a crater on Earth's moon

Mythology

* Pallas (Giant), a son of Uranus and Gaia, killed and flayed by Athena

* Pa ...

, at roughly the same distance to the Sun than Ceres. He proposed that the two objects were the remnants of a destroyed planet, and predicted that more of these pieces would be found.

Due their star-like apparience, William Herschel suggested Ceres and Pallas, and similar objects if found, be placed into a separate category, named asteroids, although they were still counted among the planets for some decades.

In 1804 Karl Ludwig Harding

Karl Ludwig Harding (29 September 1765 – 31 August 1834) was a German astronomer, who discovered 3 Juno, the third asteroid of the main-belt in 1804. The lunar crater '' Harding'' and the asteroid 2003 Harding are named in his honor. ...

discovered the asteroid Juno, and in 1807 Olbers discovered the asteroid Vesta.

In 1845 Karl Ludwig Hencke

Karl Ludwig Hencke (8 April 1793 – 21 September 1866) was a German amateur astronomer and discoverer of minor planets. He is sometimes confused with Johann Franz Encke, another German astronomer.

Biography

Hencke was born in Driesen, Branden ...

discovered a fifth body between Mars and Jupiter, Astraea

Astraea, Astrea or Astria ( grc, Ἀστραία, Astraía; "star-maiden" or "starry night"), in ancient Greek religion, is a daughter of Astraeus and Eos. She is the virgin goddess of justice, innocence, purity and precision. She is closely as ...

, and in 1849 Annibale de Gasparis

Annibale de Gasparis (9 November 1819, Bugnara – 21 March 1892, Naples; ) was an Italian astronomer, known for discovering asteroids and his contributions to theoretical astronomy.

Biography

De Gasparis was born in 1819 in Bugnara to Ang ...

discovers the asteroid Hygiea, the fourth largest asteroid in the Solar System by both volume and mass. As new objects of that kind were found there at an accelerating rate, counting them among the planets became increasingly cumbersome. Eventually, they were dropped from the planet list (as first suggested by Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

in the early 1850s) and Herschel's coinage, "asteroids", gradually came into common use. Since then, the region they occupy between Mars and Jupiter is known as the asteroid belt

The asteroid belt is a torus-shaped region in the Solar System, located roughly between the orbits of the planets Jupiter and Mars. It contains a great many solid, irregularly shaped bodies, of many sizes, but much smaller than planets, c ...

.

Alexis Bouvard

Alexis Bouvard (, 27 June 1767 – 7 June 1843) was a French astronomer. He is particularly noted for his careful observations of the irregularities in the motion of Uranus and his hypothesis of the existence of an eighth planet in the Solar ...

detected irregularities in the orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as ...

of Uranus in 1821. Later, between 1845 and 1846, John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

and Urbain Le Verrier

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier FRS (FOR) H FRSE (; 11 March 1811 – 23 September 1877) was a French astronomer and mathematician who specialized in celestial mechanics and is best known for predicting the existence and position of Neptune usin ...

separately predicted the existence and location of a new planet from irregularities in the orbit of Uranus. This new planet was finally found by Johann Galle and eventually named Neptune, following the predicted position gave to him by Le Verrier. This fact marked the climax of the Newtonian mechanics applied to astronomy, but the Neptune's orbit does not fit with the Titius-Bode rule, so it has been deprecated from then on.

Eventually, new moons were discovered also around Uranus starting in 1787 by Herschel, around Neptune starting in 1846 by William Lassell

William Lassell (18 June 1799 – 5 October 1880) was an English merchant and astronomer.around Mars in 1877 by

The

The

An accurate web-based scroll map of the Solar System scaled to the Moon being 1 pixel

{{Solar System models History of astronomy Solar System models

Asaph Hall

Asaph Hall III (October 15, 1829 – November 22, 1907) was an American astronomer who is best known for having discovered the two moons of Mars, Deimos and Phobos, in 1877. He determined the orbits of satellites of other planets and of double s ...

.

20th century add-ons

In 1919Arthur Stanley Eddington

Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington (28 December 1882 – 22 November 1944) was an English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician. He was also a philosopher of science and a populariser of science. The Eddington limit, the natural limit to the lumi ...

uses a solar eclipse to successfully test Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

's General Theory of Relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the differential geometry, geometric scientific theory, theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current descr ...

, which in turn explains the observed irregularities in the orbital motion of Mercury, and disproves the existence of the hypothesized inner planet Vulcan

Vulcan may refer to:

Mythology

* Vulcan (mythology), the god of fire, volcanoes, metalworking, and the forge in Roman mythology

Arts, entertainment and media Film and television

* Vulcan (''Star Trek''), name of a fictional race and their home p ...

.

General Theory of Relativity supersedes Newton's celestial mechanics. Instead of forces of attraction, gravity is seen as a ''bend'' of the tissue of the continuum space-time produced by the bodies' masses.

Clyde Tombaugh

Clyde William Tombaugh (February 4, 1906 January 17, 1997) was an American astronomer. He discovered Pluto in 1930, the first object to be discovered in what would later be identified as the Kuiper belt. At the time of discovery, Pluto was cons ...

discovered Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Sun. It is the largest ...

in 1930. It was regarded for decades as the ninth planet of the Solar System. In 1978 James Christy discovers Charon, the large moon of Pluto.

In 1950 Jan Oort

Jan Hendrik Oort ( or ; 28 April 1900 – 5 November 1992) was a Dutch astronomer who made significant contributions to the understanding of the Milky Way and who was a pioneer in the field of radio astronomy. His ''New York Times'' obituary ...

suggested the presence of a cometary reservoir in the outer limits of the Solar System, the Oort cloud

The Oort cloud (), sometimes called the Öpik–Oort cloud, first described in 1950 by the Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, is a theoretical concept of a cloud of predominantly icy planetesimals proposed to surround the Sun at distances ranging from ...

, and in 1951 Gerard Kuiper

Gerard Peter Kuiper (; ; born Gerrit Pieter Kuiper; 7 December 1905 – 23 December 1973) was a Dutch astronomer, planetary scientist, selenographer, author and professor. He is the eponymous namesake of the Kuiper belt.

Kuiper is ...

argued for an annular reservoir of comets between 40 and 100 astronomical unit

The astronomical unit (symbol: au, or or AU) is a unit of length, roughly the distance from Earth to the Sun and approximately equal to or 8.3 light-minutes. The actual distance from Earth to the Sun varies by about 3% as Earth orbits ...

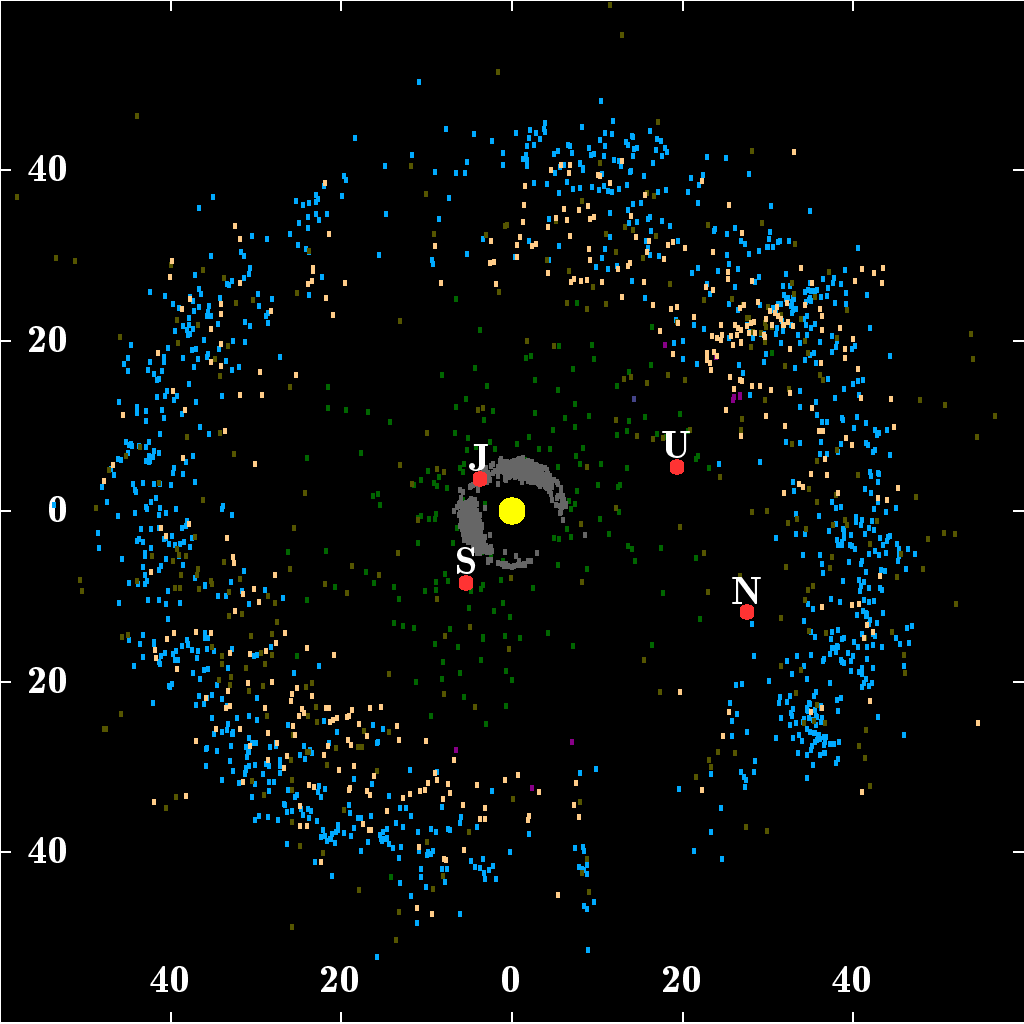

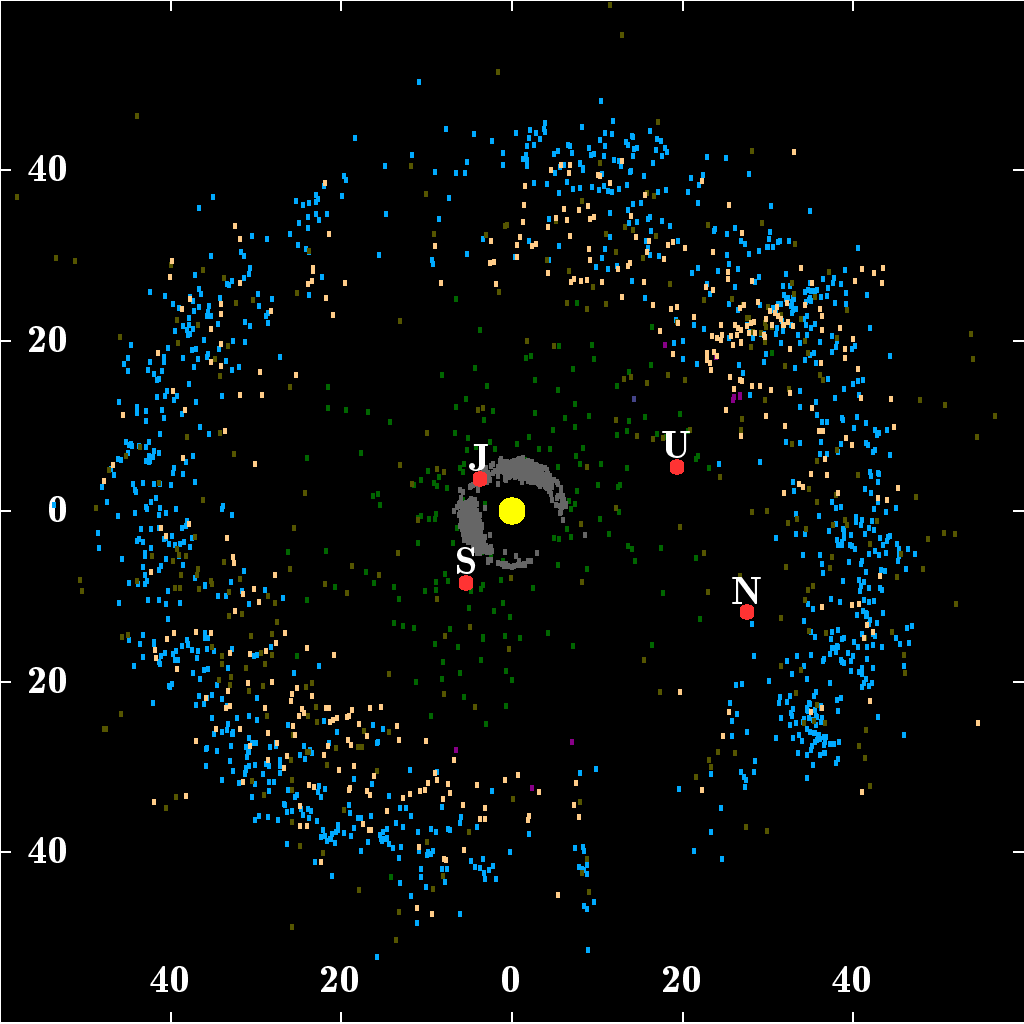

s from the Sun having formed early in the Solar System's evolution, but he did not think that such a belt still existed today. Decades later, this region was named after him, the Kuiper belt.

From 1957 on, technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and Reproducibility, reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in me ...

allowed for direct space exploration of the Solar System's bodies. To date, all their known main bodies have been visited at least once by robotic

Robotics is an interdisciplinary branch of computer science and engineering. Robotics involves design, construction, operation, and use of robots. The goal of robotics is to design machines that can help and assist humans. Robotics integrate ...

spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle or machine designed to fly in outer space. A type of artificial satellite, spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, p ...

s, providing first hand scientifical data and closeup imaginery. In some instances, robotic probes and rovers have landed on satellites, planets, asteroids and comets. And even some samples have been returned.

Current model

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

is a lone, G-type main-sequence star inside the galaxy of the Milky Way

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes our Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked eye. ...

, surrounded by eight major planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

s orbiting the star by the influence of gravity, most of them with a cohort of satellites, or moons

A natural satellite is, in the most common usage, an astronomical body that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or small Solar System body (or sometimes another natural satellite). Natural satellites are often colloquially referred to as ''moons'' ...

, orbiting them. The biggest planets also have rings

Ring may refer to:

* Ring (jewellery), a round band, usually made of metal, worn as ornamental jewelry

* To make a sound with a bell, and the sound made by a bell

:(hence) to initiate a telephone connection

Arts, entertainment and media Film and ...

, consisting of a multitude of tiny solid objects and dust.

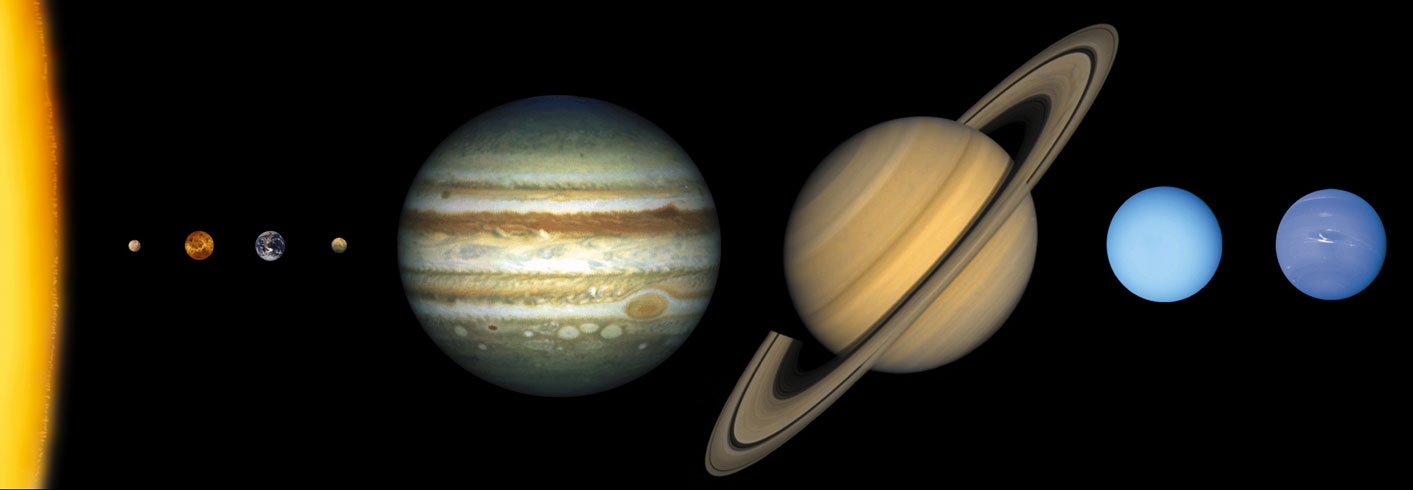

The planets are, in order of distance from the Sun: Mercury, Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

, Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

, Saturn, Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus ( Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars), grandfather of Zeus (Jupiter) and father of ...

and Neptune.

There are three main belts of minor bodies:

* The asteroid belt

The asteroid belt is a torus-shaped region in the Solar System, located roughly between the orbits of the planets Jupiter and Mars. It contains a great many solid, irregularly shaped bodies, of many sizes, but much smaller than planets, c ...

, between Mars and Jupiter.

* The Kuiper belt beyond Neptune, followed by the scattered disc

The scattered disc (or scattered disk) is a distant circumstellar disc in the Solar System that is sparsely populated by icy small solar system bodies, which are a subset of the broader family of trans-Neptunian objects. The scattered-disc obje ...

.

* The Oort cloud

The Oort cloud (), sometimes called the Öpik–Oort cloud, first described in 1950 by the Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, is a theoretical concept of a cloud of predominantly icy planetesimals proposed to surround the Sun at distances ranging from ...

in the boundaries of the Solar System.

The biggest of these minor bodies are regarded as dwarf planets

A dwarf planet is a small planetary-mass object that is in direct orbit of the Sun, smaller than any of the eight classical planets but still a world in its own right. The prototypical dwarf planet is Pluto. The interest of dwarf planets to p ...

: Ceres

Ceres most commonly refers to:

* Ceres (dwarf planet), the largest asteroid

* Ceres (mythology), the Roman goddess of agriculture

Ceres may also refer to:

Places

Brazil

* Ceres, Goiás, Brazil

* Ceres Microregion, in north-central Goiás ...

in the asteroid belt, and Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Sun. It is the largest ...

, Eris, Haumea

, discoverer =

, discovered =

, earliest_precovery_date = March 22, 1955

, mpc_name = (136108) Haumea

, pronounced =

, adjectives = Haumean

, note = yes

, alt_names =

, named_after = Haumea

, mp_category =

, orbit_ref =

, epoc ...

, Makemake

Makemake (minor-planet designation 136472 Makemake) is a dwarf planet and – depending on how they are defined – the second-largest Kuiper belt object in the classical population, with a diameter approximately 60% that of Pluto. It h ...

, Gonggong

Gonggong () is a Chinese water god who is depicted in Chinese mythology and folktales as having a copper human head with an iron forehead, red hair, and the body of a serpent, or sometimes the head and torso are human, with the tail of a serpe ...

, Quaoar

Quaoar (50000 Quaoar), provisional designation , is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a region of icy planetesimals beyond Neptune. A non-resonant object (cubewano), it measures approximately in diameter, about half the diameter of Pluto. T ...

, Sedna, and Orcus

Orcus ( la, Orcus) was a god of the underworld, punisher of broken oaths in Etruscan and Roman mythology. As with Hades, the name of the god was also used for the underworld itself. In the later tradition, he was conflated with Dis Pater.

A ...

(along with other candidates) in the Kuiper belt.

See also

*Discovery and exploration of the Solar System

Discovery and exploration of the Solar System is observation, visitation, and increase in knowledge and understanding of Earth's "cosmic neighborhood". This includes the Sun, Earth and the Moon, the major planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Sa ...

*Timeline of Solar System astronomy

The following is a timeline of Solar System astronomy and science. It includes the advances in the knowledge of the Earth at Planetary science, planetary scale, as part of it.

Direct observation

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') have inhabited the Earth ...

*Timeline of Solar System exploration

This is a timeline of Solar System exploration ordered by date of spacecraft launch. It includes:

*All spacecraft that have left Earth orbit for the purposes of Solar System exploration (or were launched with that intention but failed), includ ...

* History of astronomy

* Timeline of astronomy

* Fixed stars

References

External links

An accurate web-based scroll map of the Solar System scaled to the Moon being 1 pixel

{{Solar System models History of astronomy Solar System models