Hideki Tojo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician,

Tojo was appointed commander of the IJA 24th Infantry Brigade in August 1934. In September 1935, Tojo assumed top command of the

Tojo was appointed commander of the IJA 24th Infantry Brigade in August 1934. In September 1935, Tojo assumed top command of the

At the time,

At the time,

On December 8, 1941 (December 7 in the Americas), Tojo went on Japanese radio to announce that Japan was now at war with the United States, the British Empire, and the Netherlands, reading out an imperial rescript that ended with the playing of the popular martial song '' Umi Yukaba'' (''Across the Sea''), which set to music a popular war poem from the classic collection '' Manyōshū'', featuring the lyrics "Across the sea, corpses soaking in the water, Across the mountains corpses heaped up in the grass, We shall die by the side of our lord, We shall never look back". Tojo continued to hold the position of army minister during his term as prime minister from October 17, 1941, to July 22, 1944. He also served concurrently as home minister from 1941 to 1942,

On December 8, 1941 (December 7 in the Americas), Tojo went on Japanese radio to announce that Japan was now at war with the United States, the British Empire, and the Netherlands, reading out an imperial rescript that ended with the playing of the popular martial song '' Umi Yukaba'' (''Across the Sea''), which set to music a popular war poem from the classic collection '' Manyōshū'', featuring the lyrics "Across the sea, corpses soaking in the water, Across the mountains corpses heaped up in the grass, We shall die by the side of our lord, We shall never look back". Tojo continued to hold the position of army minister during his term as prime minister from October 17, 1941, to July 22, 1944. He also served concurrently as home minister from 1941 to 1942,  However, after the

However, after the  In September 1943, the Emperor and Tojo agreed that Japan would pull back to an "absolute defense line" in the south-west Pacific to stem the American advance, and considered abandoning Rabaul base, but changed their minds in face of objections from the Navy. In November 1943, the American public's reaction to the

In September 1943, the Emperor and Tojo agreed that Japan would pull back to an "absolute defense line" in the south-west Pacific to stem the American advance, and considered abandoning Rabaul base, but changed their minds in face of objections from the Navy. In November 1943, the American public's reaction to the

In the central Pacific, the Americans destroyed the main Japanese naval base at Truk in an air raid on February 18, 1944, forcing the Imperial Navy back to the Marianas (the oil to fuel ships and planes operating in the Marshalls, Caroline and Gilbert islands went up in smoke at Truk). This breach of the "absolute defense line", five months after its creation, led Tojo to fire Admiral

In the central Pacific, the Americans destroyed the main Japanese naval base at Truk in an air raid on February 18, 1944, forcing the Imperial Navy back to the Marianas (the oil to fuel ships and planes operating in the Marshalls, Caroline and Gilbert islands went up in smoke at Truk). This breach of the "absolute defense line", five months after its creation, led Tojo to fire Admiral  On March 12, 1944, the Japanese launched the U-Go offensive and invaded India. Tojo had some doubts about Operation U-Go, but it was ordered by the Emperor himself, and Tojo was unwilling to oppose any decision of the Emperor. Despite the Japanese Pan-Asian rhetoric and claim to be liberating India, the Indian people did not revolt and the Indian soldiers of the

On March 12, 1944, the Japanese launched the U-Go offensive and invaded India. Tojo had some doubts about Operation U-Go, but it was ordered by the Emperor himself, and Tojo was unwilling to oppose any decision of the Emperor. Despite the Japanese Pan-Asian rhetoric and claim to be liberating India, the Indian people did not revolt and the Indian soldiers of the

After Japan's unconditional surrender in 1945, U.S. general

After Japan's unconditional surrender in 1945, U.S. general  After recovering from his injuries, Tojo was moved to

After recovering from his injuries, Tojo was moved to  Hideki Tojo accepted full responsibility for his actions during the war, and made this speech:

Tojo was sentenced to death on November 12, 1948, and executed by

Hideki Tojo accepted full responsibility for his actions during the war, and made this speech:

Tojo was sentenced to death on November 12, 1948, and executed by

Tojo's commemorating tomb is located in a shrine in Hazu, Aichi (now Nishio, Aichi), and he is one of those enshrined at the controversial

Tojo's commemorating tomb is located in a shrine in Hazu, Aichi (now Nishio, Aichi), and he is one of those enshrined at the controversial

WW2DB: Hideki Tojo

* * Hideki Tojo's grave a

Findagrave

The Kokomo Tribune

September 10, 1945. * * * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Tojo, Hideki 1884 births 1948 deaths 20th-century prime ministers of Japan 20th-century criminals Shōwa Statism Tōjō Prime Ministers of Japan World War II political leaders Heads of government who were later imprisoned Executed prime ministers Executed military leaders Heads of government convicted of war crimes Japanese people convicted of crimes against humanity Japanese people convicted of the international crime of aggression Japanese people convicted of war crimes Japanese politicians convicted of crimes People executed for war crimes People executed for crimes against humanity People executed by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East Education ministers of Japan Foreign ministers of Japan Imperial Rule Assistance Association politicians International response to the Holocaust Japanese anti-communists Japanese nationalists Japanese fascists Fascist rulers Members of the Kwantung Army Ministers of Home Affairs of Japan Ministers of the Imperial Japanese Army 20th-century Japanese politicians Politicians from Tokyo Imperial Japanese Army officers Genocide perpetrators People executed by hanging Executed mass murderers

general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

of the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

(IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan

The prime minister of Japan ( Japanese: 内閣総理大臣, Hepburn: ''Naikaku Sōri-Daijin'') is the head of government of Japan. The prime minister chairs the Cabinet of Japan and has the ability to select and dismiss its Ministers of S ...

and president of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association

The , or Imperial Aid Association, was the Empire of Japan's ruling organization during much of World War II. It was created by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe on 12 October 1940, to promote the goals of his ("New Order") movement. It evolved i ...

for most of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. He assumed several more positions including chief of staff of the Imperial Army before ultimately being removed from power in July 1944. During his years in power, his leadership was marked by extreme state-perpetrated violence in the name of Japanese ultranationalism, much of which he was personally involved in.

Hideki Tojo was born on December 30, 1884, to a relatively low-ranking samurai family in the Kōjimachi district of Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

. He began his career in the Army in 1902 and steadily rose through the ranks to become a general by 1934. In March 1937, he was promoted to chief of staff of the Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

whereby he led military operations against the Chinese in Inner Mongolia and the Chahar-Suiyan provinces. By July 1940, he was appointed minister of war to the Japanese government led by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

.

On the eve of the Second World War's expansion into Asia and the Pacific, Tojo was an outspoken advocate for a preemptive attack on the United States and its European allies. Upon being appointed prime minister on October 17, 1941, he oversaw the Empire of Japan's decision to go to war as well as its ensuing conquest of much of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

and the Pacific Islands. During the course of the war, Tojo presided over numerous war crimes, including the massacre and starvation of civilians and prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

. He was also involved in the sexual enslavement of thousands of mostly Korean women and girls for Japanese soldiers, an event that still strains modern Japanese–Korean relations.

After the war's tide decisively turned against Japan, Tojo was forced to resign as prime minister on July 18th, 1944. Following his nation's surrender to the Allied Powers in September 1945, he was arrested, convicted by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conv ...

in the Tokyo Trials, sentenced to death, and hanged on December 23, 1948. To this day, Tojo's complicity in atrocities such as the Rape of Nanjing

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the ...

, the Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March ( Filipino: ''Martsa ng Kamatayan sa Bataan''; Spanish: ''Marcha de la muerte de Bataán'' ; Kapampangan: ''Martsa ning Kematayan quing Bataan''; Japanese: バターン死の行進, Hepburn: ''Batān Shi no Kōshin'') ...

, and human experimentation entailing the torture and death of thousands have firmly intertwined his legacy with the fanatical brutality shown by the Japanese Empire throughout World War II.

Early life and education

Hideki Tojo was born in the Kōjimachi district ofTokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

on December 30, 1884, as the third son of Hidenori Tojo, a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army. Under the ''bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakura ...

'', Japanese society was divided rigidly into four castes; the merchants, artisans, peasants, and the samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They ...

. After the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

, the caste system was abolished in 1871, but the former caste distinctions in many ways persisted afterwards, ensuring that those from the former samurai caste continued to enjoy their traditional prestige. The Tojo family came from the samurai caste, though the Tojos were relatively lowly warrior retainers for the great ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominall ...

s'' (lords) that they had served for generations. Tojo's father was a samurai turned Army officer and his mother was the daughter of a Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

priest, making his family very respectable, but poor.

Hideki had an education typical of Japanese youth in the Meiji era. The purpose of the Meiji educational system was to train the boys to be soldiers as adults, and the message was relentlessly drilled into Japanese students that war was the most beautiful thing in the entire world, that the emperor was a living god, and that the greatest honor for a Japanese man was to die for the emperor. Japanese girls were taught that the highest honor for a woman was to have as many sons as possible who could die for the emperor in war. As a boy, Tojo was known for his stubbornness, lack of a sense of humor, for being an opinionated and combative youth fond of getting into fights with the other boys, and for his tenacious way of pursuing what he wanted. Japanese schools in the Meiji era were very competitive, and there was no tradition of sympathy for failure; those who did so were often bullied by the teachers. Those who knew him during his formative years deemed him to be of only average intelligence. However, he was known to compensate for his observed lack of intellect with a willingness to work extremely hard. Tojo's boyhood hero was the 17th-century shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fello ...

who issued the injunction: "Avoid the things you like, turn your attention to unpleasant duties". Tojo liked to say: "I am just an ordinary man possessing no shining talents. Anything I have achieved I owe to my capacity for hard work and never giving up". In 1899, Tojo enrolled in the Army Cadet School.

In 1905, Tojo shared in the general outrage in Japan at the Treaty of Portsmouth

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

, which ended the war with Russia, and which the Japanese people saw as a betrayal as the war did not end with Japan annexing Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

as popular opinion had demanded. The Treaty of Portsmouth was so unpopular that it set off anti-American riots known as the Hibiya incendiary incident as many Japanese were enraged at the way the Americans had apparently cheated Japan as the Japanese gains in the treaty were far less than what public opinion had expected. Very few Japanese at the time had understood that the war with Russia had pushed their nation to the verge of bankruptcy, and most people in Japan believed that the American president Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

who had mediated the Treaty of Portsmouth had cheated Japan out of its rightful gains. Tojo's anger at the Treaty of Portsmouth left him with an abiding dislike of Americans. In 1909, he married Katsuko Ito, with whom he had three sons (Hidetake, Teruo, and Toshio) and four daughters (Mitsue, Makie, Sachie, and Kimie).

Military career

Early service as officer

Upon graduating from the Japanese Military Academy (ranked 10th of 363 cadets) in March 1902, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the infantry of the IJA. In 1918–19, he briefly served in Siberia as part of the Japanese expeditionary force sent to intervene in theRussian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

. He served as Japanese military attache to Germany between 1919 and 1922. As the Imperial Japanese Army had been trained by a German military mission in the 19th century, the Japanese Army was always very strongly influenced by intellectual developments in the German Army, and Tojo was no exception. In the 1920s, the German military favored preparing for the next war by creating a totalitarian ''Wehrstaat'' (Defense State), an idea that was taken up by the Japanese military as the "national defense state". In 1922, on his way home to Japan, he took a train ride across the United States, his first and only visit to America, which left him with the impression that the Americans were a materialistic soft people devoted only to making money and to hedonistic pursuits like sex, partying, and (despite Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

) drinking.

Tojo boasted that his only hobby was his work, and he customarily brought home his paperwork to work late into the night, and he refused to have any part in raising his children, which he viewed both as a distraction from his work and a woman's work, having his wife do all the work of taking care of his children. A stern, humorless man, he was known for his brusque manner, his obsession with etiquette, and for his coldness. Like almost all Japanese officers at the time, he routinely slapped the faces of the men under his command when giving orders, saying that face-slapping was a "means of training" men who came from families that were not part of the samurai caste, and for whom bushido

is a moral code concerning samurai attitudes, behavior and lifestyle. There are multiple bushido types which evolved significantly through history. Contemporary forms of bushido are still used in the social and economic organization of Japan. ...

was not second nature.

In 1924, Tojo was greatly offended by the Immigration Control Act passed by the American Congress banning all Asian immigration into the United States with many congressmen and senators openly saying the act was necessary because the Asians worked harder than whites. He wrote with bitterness at the time that American whites would never accept Asians as equals and "It he Immigration Control Act

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

shows how the strong will always put their own interests first. Japan, too, has to be strong to survive in the world".

By 1928, he was bureau chief of the Japanese Army and was shortly thereafter promoted to colonel. He began to take an interest in militarist politics during his command of the 8th Infantry Regiment. Reflecting the imagery often used in Japan to describe people in power, he told his officers that they were to be both a "father" and a "mother" to the men under their command. Tojo often visited the homes of the men under his command, assisted his men with personal problems, and made loans to officers short of money. Like many other Japanese officers, he disliked Western cultural influence in Japan, which was often disparaged as resulting in the ero-guro-nansensu ("eroticism, grotesquerie and nonsense") movement as he complained about such forms of "Western decadence" like young couples holding hands and kissing in public, which were undermining traditional values necessary to uphold the ''kokutai

is a concept in the Japanese language translatable as " system of government", "sovereignty", "national identity, essence and character", "national polity; body politic; national entity; basis for the Emperor's sovereignty; Japanese constitu ...

''.

Promotion to Army high command

In 1934, Hideki was promoted tomajor general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

and served as chief of the personnel department within the Army Ministry. Tojo wrote a chapter in the book ''Hijōji kokumin zenshū'' (''Essays in time of national emergency''), a book published in March 1934 by the Army Ministry calling for Japan to become a totalitarian "national defense state". This book of fifteen essays by senior generals argued that Japan had defeated Russia in the war of 1904–05 because ''bushidō'' had given the Japanese superior willpower as the Japanese did not fear death unlike the Russians who wanted to live, and what was needed to win the

inevitable next war (against precisely whom the book did not say) was to repeat the example of the Russian-Japanese war on a much greater scale by creating the "national defense state" that would mobilize the entire nation for war. In his essay Tojo wrote "The modern war of national defense extends over a great many areas" requiring "a state that can monolithically control" all aspects of the nation in the political, social and economic spheres. Tojo attacked Britain, France and the United States for waging "ideological war" against Japan since 1919. Tojo ended his essay stating that Japan must stand tall "and spread its own moral principles to the world" as the "cultural and ideological war of the 'imperial way' is about to begin".

Tojo was appointed commander of the IJA 24th Infantry Brigade in August 1934. In September 1935, Tojo assumed top command of the

Tojo was appointed commander of the IJA 24th Infantry Brigade in August 1934. In September 1935, Tojo assumed top command of the Kenpeitai

The , also known as Kempeitai, was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945 that also served as a secret police force. In addition, in Japanese-occupied territories, the Kenpeitai arrested or killed those suspec ...

of the Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

in Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

. Politically, he was nationalist, and militarist, and was nicknamed , for his reputation of having a sharp and legalistic mind capable of quick decision-making. Tojo was a member of the ''Tōseiha

The ''Tōseiha'' or was a political faction in the Imperial Japanese Army active in the 1920s and 1930s. The ''Tōseiha'' was a grouping of moderate officers united primarily by their opposition to the radical ''Kōdōha'' (Imperial Way) faction ...

'' ("Control") faction in the Army that was opposed by the more radical ''Kōdōha

The ''Kōdōha'' or was a political faction in the Imperial Japanese Army active in the 1920s and 1930s. The ''Kōdōha'' sought to establish a military government that promoted totalitarian, militaristic and aggressive expansionistic ideal ...

'' ("Imperial Way") faction. Both the ''Tōseiha'' and the ''Kōdōha'' factions were militaristic groups that favored a policy of expansionism abroad and dictatorship under the Emperor at home, but differed over the best way of achieving these goals. The Imperial Way faction wanted a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

to achieve a Shōwa Restoration

The was promoted by Japanese author Kita Ikki in the 1930s, with the goal of restoring power to the newly enthroned Emperor Shōwa and abolishing the liberal Taishō democracy. The aims of the "Shōwa Restoration" were similar to the Meiji Rest ...

; emphasised "spirit" as the principle war-winning factor; and despite advocating socialist policies at home wanted to invade the Soviet Union. The Control faction, while being willing to use assassination to achieve its goals, was more willing to work within the system to achieve reforms; wanted to create the "national defense state" to mobilize the entire nation before going to war; and, while not rejecting the idea of "spirit" as a war-winning factor also saw military modernization as a war-winning factor; and saw the United States as a future enemy just as much as the Soviet Union.

During the February 26 coup attempt of 1936, Tojo and Shigeru Honjō, a noted supporter of Sadao Araki

Baron was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War II. As one of the principal nationalist right-wing political theorists in the Empire of Japan, he was regarded as the leader of the radical faction within the polit ...

, both opposed the rebels who were associated with the rival "Imperial Way" faction. Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

himself was outraged at the attacks on his close advisers, and after a brief political crisis and stalling on the part of a sympathetic military, the rebels were forced to surrender. As the commander of the ''Kenpeitai'', Tojo ordered the arrest of all officers in the Kwantung Army suspected of supporting the coup attempt in Tokyo. In the aftermath, the Tōseiha faction was able to purge the Army of radical officers, and the coup leaders were tried and executed. Following the purge, Tōseiha and Kōdōha elements were unified in their nationalist but highly anti-political stance under the banner of the Tōseiha military clique, which included Tojo as one of its leaders.

Tojo was promoted to chief of staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

of the Kwangtung Army in 1937. As the " Empire of Manchukuo" was, in reality, a Japanese colony in all but name, the Kwangtung Army's duties were just as much political as they were military. During this period, Tojo became close to Yōsuke Matsuoka

was a Japanese diplomat and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Empire of Japan during the early stages of World War II. He is best known for his defiant speech at the League of Nations in February 1933, ending Japan's participation in the organ ...

, the fiery ultra-nationalist CEO of the South Manchuria Railway

The South Manchuria Railway ( ja, 南満州鉄道, translit=Minamimanshū Tetsudō; ), officially , Mantetsu ( ja, 満鉄, translit=Mantetsu) or Mantie () for short, was a large of the Empire of Japan whose primary function was the operatio ...

, one of Asia's largest corporations at the time, and Nobusuke Kishi

was a Japanese bureaucrat and politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Known for his exploitative rule of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China in the 1930s, Kishi was nicknamed the "Monster of the Sh� ...

, the Deputy Minister of Industry in Manchukuo, who was the man ''de facto'' in charge of Manchukuo's economy. Though Tojo regarded preparing for a war with the Soviet Union as his first duty, Tojo also supported the forward policy in north China as the Japanese sought to extend their influence into China. As chief of staff, Tojo was responsible for the military operations designed to increase Japanese penetration into the Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

border regions with Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

. In July 1937, he personally led the units of the 1st Independent Mixed Brigade in Operation Chahar, his only real combat experience.

After the Marco Polo Bridge Incident

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident, also known as the Lugou Bridge Incident () or the July 7 Incident (), was a July 1937 battle between China's National Revolutionary Army and the Imperial Japanese Army.

Since the Japanese invasion of Manchuri ...

marking the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

, Tojo ordered his forces to attack Hebei Province

Hebei or , (; alternately Hopeh) is a northern province of China. Hebei is China's sixth most populous province, with over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. The province is 96% Han Chinese, 3% Manchu, 0.8% Hui, and 0 ...

and other targets in northern China. Tojo received Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish refugees in accordance with Japanese national policy and rejected the resulting Nazi German protests. Tojo was recalled to Japan in May 1938 to serve as Vice-Minister of War under Army Minister Seishirō Itagaki

was a Japanese military officer and politician who served as a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II and War Minister from 1938 to 1939.

Itagaki was a main conspirator behind the Mukden Incident and held prestigious chief of ...

. From December 1938 to 1940, Tojo was Inspector-General of Army Aviation.

Rise to Prime Minister

Advocacy for preventive war

On June 1, 1940, Emperor Hirohito appointed Kōichi Kido, a leading "reform bureaucrat" as the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, making him into the Emperor's leading political advisor and fixer. Kido had aided in the creation in the 1930s of an alliance between the "reform bureaucrats" and the Army's "Control" faction centered around Tojo and General Mutō Akira. Kido's appointment also favored the rise of his allies in the Control faction. On July 30, 1940, Hideki Tojo was appointed army minister in the secondFumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

regime and remained in that post in the third Konoe cabinet. Prince Konoe had chosen Tojo—a man representative of both the Army's hardline views and the Control faction while being considered reasonable to deal with—to secure the Army's backing for his foreign policy. Tojo was a militant ultra-nationalist, well respected for his work ethic and his ability to handle paperwork, who believed that the emperor was a living god and favored "direct imperial rule", ensuring that he would faithfully follow any order from the emperor. Konoe favored having Germany mediate an end to the Sino-Japanese war, pressuring Britain to end its economic and military support of China even at the risk of war, seeking better relations with both Germany and the United States, and taking advantage of the changes in the international order caused by Germany's victories in the spring of 1940 to make Japan a stronger power in Asia. Konoe wanted to make Japan the dominant power in East Asia, but he also believed it was possible to negotiate a ''modus vivendi'' with the United States under which the Americans would agree to recognize the "Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

".

By 1940, Konoe, who had started the war with China in 1937, no longer believed that a military solution to the "China Affair" was possible as he once did, instead favored having Germany mediate an end to the war that would presumably result in a pro-Japanese peace settlement, but would be less than he himself had outlined in the "Konoe programme" of January 1938. For this reason, Konoe wanted Tojo, a tough general whose ultra-nationalism was beyond question, to provide "cover" for his attempt to seek a diplomatic solution to the war with China. Tojo was a strong supporter of the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

between Imperial Japan, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, and Fascist Italy. As the army minister, he continued to expand the war with China. After negotiations with Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

, Japan was given permission to place its troops in the southern part of French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

in July 1941. In spite of its formal recognition of the Vichy government, the United States retaliated against Japan by imposing economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they ...

in August, including a total embargo on oil and gasoline exports. On September 6, a deadline of early October was fixed in the Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

for resolving the situation diplomatically. On October 14, the deadline had passed with no progress. Prime Minister Konoe then held his last cabinet meeting, where Tojo did most of the talking:

The prevailing opinion within the Japanese Army at that time was that continued negotiations could be dangerous. However, Hirohito thought that he might be able to control extreme opinions in the army by using the charismatic and well-connected Tojo, who had expressed reservations regarding war with the West, although the emperor himself was skeptical that Tojo would be able to avoid conflict. On October 13, he declared to Kōichi Kido: "There seems little hope in the present situation for the Japan-U.S. negotiations. This time, if hostilities erupt, I have to issue a declaration of war." During the last cabinet meetings of the Konoe government, Tojo emerged as a hawkish voice, saying he did not want a war with the United States but portrayed the Americans as arrogant, bullying, white supremacists. He said that any compromise solution would only encourage them to make more extreme demands on Japan, in which case Japan might be better off choosing war to uphold national honor. Despite saying he favored peace, Tojo had often declared at cabinet meetings that any withdrawal from French Indochina and/or China would be damaging to military morale and might threaten the ''kokutai''; the "China Incident" could not be resolved via diplomacy and required a military solution; and attempting to compromise with the Americans would be seen as weakness by them.

On October 16, Konoe, politically isolated and convinced that the emperor no longer trusted him, resigned. Later, he justified himself to his chief cabinet secretary, Kenji Tomita:

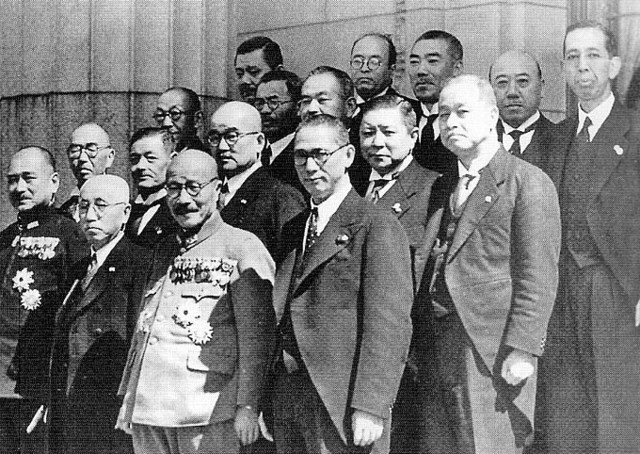

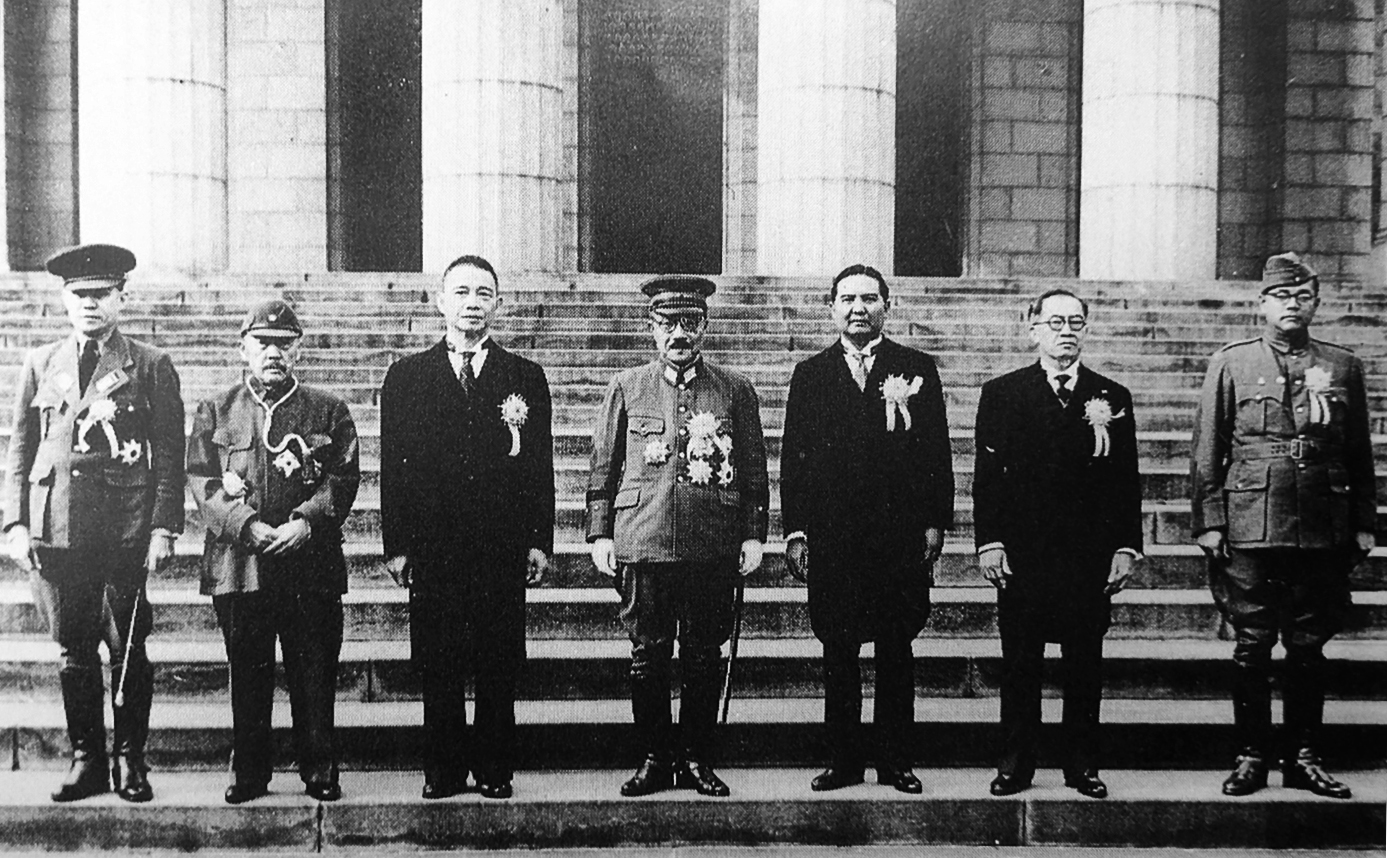

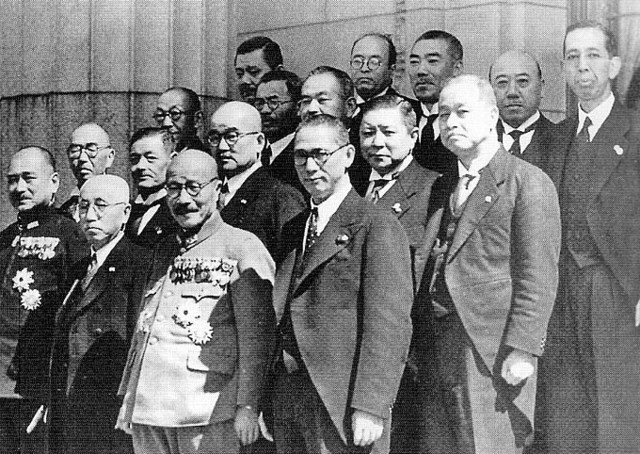

Appointment as Prime Minister

At the time,

At the time, Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni

General was a Japanese imperial prince, a career officer in the Imperial Japanese Army and the 30th Prime Minister of Japan from 17 August 1945 to 9 October 1945, a period of 54 days. An uncle-in-law of Emperor Hirohito twice over, Prince Hi ...

was said to be the only person who could control the Army and the Navy and was recommended by Konoe and Tojo as Konoe's replacement. Hirohito rejected this option, arguing that a member of the imperial family should not have to eventually carry the responsibility for a war against the West as a defeat would ruin the prestige of the House of Yamato. Following the advice of Kōichi Kido, he chose instead Tojo, who was known for his devotion to the imperial institution. By tradition, the Emperor needed a consensus among the elder statesmen or "''jushin''" before appointing a prime minister, and as long as former Prime Minister Admiral Keisuke Okada

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, politician and Prime Minister of Japan from 1934 to 1936.

Biography

Early life

Okada was born on 20 January 1868, in Fukui Prefecture, the son of a samurai of the Fukui Domain. He attended the 1 ...

was opposed to Tojo, it would be impolitic for the Emperor to appoint him. During the meetings of the ''jushin'' regarding Prince Konoe's succession, Okada argued against Tojo's appointment while the powerful Lord Privy Seal Kōichi Kido pushed for Tojo. The result was a compromise where Tojo would become Prime Minister while "re-examining" the options for dealing with the crisis with the United States, though no promise was made Tojo would attempt to avoid a war.

After being informed of Tojo's appointment, Prince Takamatsu wrote in his diary: "We have finally committed to war and now must do all we can to launch it powerfully. But we have clumsily telegraphed our intentions. We needn't have signaled what we're going to do; having he entire Konoe cabinetresign was too much. As matters stand now we can merely keep silent and without the least effort war will begin." Tojo's first speech on the radio made a call for "world peace", but also stated his determination to settle the "China Affair" on Japanese terms and to achieve the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" that would unite all of the Asian nations together.

Decision for war

The Emperor summoned Tojo to the Imperial Palace one day before Tojo took office. After being informed of his appointment, Tojo was given one order from the Emperor: to make a policy review of what had been sanctioned by the Imperial Conferences. Despite being vocally on the side of war, Tojo nevertheless accepted this order, and pledged to obey. According to Colonel Akiho Ishii, a member of the Army General Staff, the newly appointed prime minister showed a true sense of loyalty to the emperor performing this duty. For example, when Ishii received from Hirohito a communication saying the Army should drop the idea of stationing troops in China to counter the military operations of the Western powers, he wrote a reply for the Prime Minister for his audience with the Emperor. Tojo then replied to Ishii: "If the Emperor said it should be so, then that's it for me. One cannot recite arguments to the Emperor. You may keep your finely phrased memorandum." On November 2, Tojo and Chiefs of StaffHajime Sugiyama

was a Japanese field marshal and one of the leaders of Japan's military throughout most of World War II. As Army Minister in 1937, Sugiyama was a driving force behind the launch of hostilities against China in retaliation for the Marco Polo Bri ...

and Osami Nagano

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of the leaders of Japan's military during most of the Second World War. In April 1941, he became Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff. In this capacity, he served as the ...

reported to Hirohito that the review had been in vain. The Emperor then gave his consent to war. The next day, Fleet Admiral Osami Nagano

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of the leaders of Japan's military during most of the Second World War. In April 1941, he became Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff. In this capacity, he served as the ...

explained in detail the Pearl Harbor attack plan to Hirohito. The eventual plan drawn up by Army and Navy Chiefs of Staff envisaged such a mauling of the Western powers that Japanese defense perimeter lines—operating on interior lines of communications and inflicting heavy Western casualties—could not be breached. In addition, the Japanese fleet which attacked Pearl Harbor was under orders from Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II until he was killed.

Yamamoto held several important posts in the IJN, and undertook many of its changes and reor ...

to be prepared to return to Japan on a moment's notice, should negotiations succeed. Two days later, on November 5, Hirohito approved the operations plan for a war against the West and continued to hold meetings with the military and Tojo until the end of the month.

On November 26, 1941, the American Secretary of State Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

handed Ambassador Nomura and Kurusu Saburo in Washington a "draft mutual declaration of policy" and "Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement between the United States and Japan". Hull proposed that Japan "withdraw all military, naval, air and police forces" from China and French Indochina in exchange for lifting the oil embargo, but left the term China undefined. The "Hull note

The Hull note, officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1 ...

" as it is known in Japan made it clear the United States would not recognise the puppet government of Wang Jingwei as the government of China, but strongly implied that the United States might recognise the "Empire of Manchukuo" and did not impose a deadline for the Japanese withdrawal from China. On November 27, 1941, Tojo chose to misrepresent the "Hull note" to the Cabinet as an "ultimatum to Japan", which was incorrect as the "Hull note" did not have a timeline for its acceptance and was marked "tentative" in the opening sentence, which is inconsistent with an ultimatum. The claim that the Americans had demanded in the "Hull note" Japanese withdrawal from all of China, instead of just the parts occupied since 1937 and together with the claim the note was an ultimatum was used as one of the principal excuses for choosing war with the United States. On December 1, another conference finally sanctioned the "war against the United States, England, and the Netherlands".

World War II

On December 8, 1941 (December 7 in the Americas), Tojo went on Japanese radio to announce that Japan was now at war with the United States, the British Empire, and the Netherlands, reading out an imperial rescript that ended with the playing of the popular martial song '' Umi Yukaba'' (''Across the Sea''), which set to music a popular war poem from the classic collection '' Manyōshū'', featuring the lyrics "Across the sea, corpses soaking in the water, Across the mountains corpses heaped up in the grass, We shall die by the side of our lord, We shall never look back". Tojo continued to hold the position of army minister during his term as prime minister from October 17, 1941, to July 22, 1944. He also served concurrently as home minister from 1941 to 1942,

On December 8, 1941 (December 7 in the Americas), Tojo went on Japanese radio to announce that Japan was now at war with the United States, the British Empire, and the Netherlands, reading out an imperial rescript that ended with the playing of the popular martial song '' Umi Yukaba'' (''Across the Sea''), which set to music a popular war poem from the classic collection '' Manyōshū'', featuring the lyrics "Across the sea, corpses soaking in the water, Across the mountains corpses heaped up in the grass, We shall die by the side of our lord, We shall never look back". Tojo continued to hold the position of army minister during his term as prime minister from October 17, 1941, to July 22, 1944. He also served concurrently as home minister from 1941 to 1942, foreign minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

in September 1942, education minister in 1943, and minister of Commerce and Industry in 1943.

As education minister, he continued militaristic

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

indoctrination in the national education system, and reaffirmed totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

policies in government. As home minister, he ordered various eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

measures (including the sterilization of the "mentally unfit").

In the early years of the war, Tojo had popular support as Japanese forces moved from one victory to another. In March 1942, in his capacity as army minister he gave permission for the Japanese Army in Taiwan to ship 50 "comfort women

Comfort women or comfort girls were women and girls forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army in occupied countries and territories before and during World War II. The term "comfort women" is a translation of the Japanese '' ian ...

" from Taiwan to Borneo without ID papers (his approval was necessary as the Army's rules forbade people without ID traveling to the new conquests). The Japanese historian Yoshiaki Yoshimi noted this document proves that Tojo was aware of and approved of the "comfort women" corps. On April 18, 1942, the Americans staged the Doolittle Raid

The Doolittle Raid, also known as the Tokyo Raid, was an air raid on 18 April 1942 by the United States on the Japanese capital Tokyo and other places on Honshu during World War II. It was the first American air operation to strike the Japa ...

, bombing Tokyo. Some of the American planes were shot down and their pilots taken prisoner. The Army General Staff led by Field Marshal Hajime Sugiyama

was a Japanese field marshal and one of the leaders of Japan's military throughout most of World War II. As Army Minister in 1937, Sugiyama was a driving force behind the launch of hostilities against China in retaliation for the Marco Polo Bri ...

insisted on executing the eight American fliers, but was opposed by Tojo, who feared that the Americans would retaliate against Japanese POWs if the Doolittle fliers were executed. The dispute was resolved by the emperor who commuted the death sentences of five fliers while allowing the other three to die, for reasons that remain unclear as the documents relating to the emperor's intervention were burned in 1945.

As the Japanese went from victory to victory, Tojo and the rest of the Japanese elite were gripped by what the Japanese called "victory disease

Victory disease occurs in military history when complacency or arrogance, brought on by a victory or a series of victories, makes an engagement end disastrously for a commander and his forces.

A commander may disdain the enemy, and believe ...

" as the entire elite was caught up in a state of hubris, believing Japan was invincible and the war was as good as won. By May 1942, Tojo approved a set of "non-negotiable" demands to be presented once the Allies sued for peace that allowed Japan to keep everything it already conquered while assuming possession of considerably more. Under such demands, Japan would assume control of the following territories:

* the British Crown colonies of India and Honduras as well as the British dominions of Australia, Australian New Guinea, Ceylon, New Zealand, British Columbia and the Yukon Territory

* the American state of Washington and the American territories of Alaska and Hawaii

* most of Latin America including Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti and the rest of the West Indies.

Additionally, Tojo wanted all of China to be under the rule of the puppet Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

, planned to buy Macau and East Timor from Portugal and to create new puppet kingdoms in Burma, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaya. As the Burmese had proved to be enthusiastic collaborators in the "New Order in Asia", the new Burmese kingdom would be allowed to annex much of north-east India as a reward. The Navy for its part demanded that Japan take New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa.

While Tojo was prime minister, the main forum for military decision-making was the Imperial General Headquarters presided over by the Emperor. It consisted of the Army and Navy ministers; the Army and Navy chiefs of staff; and chiefs of the military affairs bureaus in both services. The Imperial GHQ was not a joint chiefs of staff as existed in the United States and United Kingdom, but rather two separate services command operating under the same roof who would meet about twice a week to attempt to agree on a common strategy. The Operations Bureaus of the Army and Navy would develop their own plans and then attempt to "sell them" to the other, which was often not possible. Tojo was one voice out of many speaking at the Imperial GHQ, and was not able to impose his will on the Navy, which he had to negotiate with, as if dealing with an ally. The American historian Stanley Falk described the Japanese system as characterized by "bitter inter-service antagonisms" as the Army and Navy worked "at cross-purposes", observing the Japanese system of command was "uncoordinated, ill-defined and inefficient".

However, after the

However, after the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under ...

, with the tide of war turning against Japan, Tojo faced increasing opposition within the government and military. In August–September 1942, a major crisis gripped the Tojo cabinet when the Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō

(10 December 1882 – 23 July 1950), was Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Empire of Japan at both the start and the end of the Axis–Allied conflict during World War II. He also served as Minister of Colonial Affairs in 1941, and assume ...

objected quite violently on August 29, 1942, to the Prime Minister's plan to establish a Greater East Asia Ministry to handle relations with the puppet regimes in Asia as an insult to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (the ''Gaimusho'') and threatened to resign in protest. Tojo went to see the Emperor, who backed the Prime Minister's plans for the Greater East Asia Ministry, and on September 1, 1942, Tojo told the cabinet he was establishing the Greater East Asia Ministry and could not care less about how the ''Gaimusho'' felt about the issue, leading Tōgō to resign in protest. The American historian Herbert Bix

Herbert P. Bix (born 1938) is an American historian. He wrote ''Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan'', an account of the Japanese Emperor and the events which shaped modern Japanese imperialism, which won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfict ...

wrote that Tojo was a "dictator" only in the narrow sense that from September 1942 on, he was generally able to impose his will on the Cabinet without seeking a consensus, but at the same time noted that Tojo's authority was based upon the support of the Emperor, who held ultimate power. In November 1942, Tojo, as Army Minister, was involved in drafting the regulations for taking "comfort women" from China, Japan (which included Taiwan and Korea at this time) and Manchukuo to the "South", as the Japanese called their conquests in South-East Asia, to ensure that the "comfort women" had the proper papers before departing. Until then the War Ministry required special permission to take "comfort women" without papers, and Tojo was tired of dealing with these requests. At the same time, Tojo, as the Army Minister, became involved in a clash with the Army chief of staff over whether to continue the battle of Guadalcanal or not. Tojo sacked the Operations office and his deputy at the general staff, who were opposed to withdrawing, and ordered the abandonment of the island.

Battle of Tarawa

The Battle of Tarawa was fought on 20–23 November 1943 between the United States and Japan at the Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, and was part of Operation Galvanic, the U.S. invasion of the Gilberts. Nearly 6,400 Japanese, Koreans, ...

led Tojo to view Tarawa as a sort of Japanese victory, believing that more battles like Tarawa would break American morale, and force the U.S. to sue for peace. Moreover, Tojo believed that the Americans would become bogged down in the Marshalls, giving more time to strengthen the defenses in the Marianas. In late 1943, with the support of the Emperor, Tojo made a major effort to make peace with China to free up the 2 million Japanese soldiers in China for operations elsewhere, but the unwillingness of the Japanese to give up any of their "rights and interests" in China doomed the effort. China was by far the largest theater of operations for Japan, and with the Americans steadily advancing in the Pacific, Tojo was anxious to end the quagmire of the "China affair" to redeploy Japanese forces. In an attempt to enlist support from all of Asia, especially China, Tojo opened the Greater East Asia Conference

was an international summit held in Tokyo from 5 to 6 November 1943, in which the Empire of Japan hosted leading politicians of various component members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The event was also referred to as the Toky ...

in November 1943, which issued a set of Pan-Asian war aims, which made little impression on most Asians. On January 9, 1944, Japan signed a treaty with the puppet Wang regime under which Japan gave up its extraterritorial rights in China as part of a bid to win Chinese public opinion over to a pro-Japanese viewpoint, but as the treaty changed nothing in practice, the gambit failed.

At the same time as he sought a diplomatic effort to end the war with China, Tojo also approved of the planning for Operation Ichi-Go

Operation Ichi-Go ( ja, 一号作戦, Ichi-gō Sakusen, lit=Operation Number One) was a campaign of a series of major battles between the Imperial Japanese Army forces and the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China, fought from A ...

, a huge offensive against China intended to take the American air bases in China and finally knock China out of the war once and for all. In January 1944, Tojo approved of orders issued by Imperial General Headquarters for an invasion of India, where the Burma Area Army in Burma under General Masakazu Kawabe

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. He held important commands in the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War, and during World War II in the Burma Campaign and defense of the Japanese homeland late in the war. He was ...

was to seize the Manipour and Assam provinces with the aim of cutting off American aid to China (the railroad that supplied the American air bases in north-east India that allowed for supplies to be flown over "the Hump

The Hump was the name given by Allied pilots in the Second World War to the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains over which they flew military transport aircraft from India to China to resupply the Chinese war effort of Chiang Kai-shek ...

" of the Himalayas to China passed through these provinces). Cutting off American aid to China in turn might have had the effect of forcing Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

to sue for peace. Following the 15th Army into India in the U-Go offensive were the Indian nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose ( ; 23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*) was an Indian nationalist whose defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among Indians, but his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperi ...

and his Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a collaborationist armed force formed by Indian collaborators and Imperial Japan on 1 September 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II. Its aim was to secure In ...

, as the political purpose of the operation was to provoke a general uprising against British rule in India that might allow the Japanese to take all of India. The roads necessary to properly supply the 150,000 Japanese soldiers committed to invading India would turn into mud when the monsoons arrived, giving the Japanese a very short period of time to break through. The Japanese were counting on capturing food from the British to feed their army, assuming that all of India would rise up when the Japanese arrived and thereby cause the collapse of the Raj. The Japanese brought along with them enough food to last for only 20 days; after that, they would have to capture food from the British to avoid starving. Bose had impressed Tojo at their meetings as the best man to inspire an anti-British revolution in India.

In the central Pacific, the Americans destroyed the main Japanese naval base at Truk in an air raid on February 18, 1944, forcing the Imperial Navy back to the Marianas (the oil to fuel ships and planes operating in the Marshalls, Caroline and Gilbert islands went up in smoke at Truk). This breach of the "absolute defense line", five months after its creation, led Tojo to fire Admiral

In the central Pacific, the Americans destroyed the main Japanese naval base at Truk in an air raid on February 18, 1944, forcing the Imperial Navy back to the Marianas (the oil to fuel ships and planes operating in the Marshalls, Caroline and Gilbert islands went up in smoke at Truk). This breach of the "absolute defense line", five months after its creation, led Tojo to fire Admiral Osami Nagano

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of the leaders of Japan's military during most of the Second World War. In April 1941, he became Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff. In this capacity, he served as the ...

as the Navy Chief of Staff, for incompetence. The Americans had penetrated 2,100 km (1,300 miles) beyond the "absolute defense line" at Truk, and Tojo, senior generals and admirals all blamed each other for the situation. To strengthen his position in face of criticism of the way the war was going, on February 21, 1944, Tojo assumed the post of Chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff

The , also called the Army General Staff, was one of the two principal agencies charged with overseeing the Imperial Japanese Army.

Role

The was created in April 1872, along with the Navy Ministry, to replace the Ministry of Military Affairs ...

, arguing he needed to take personal charge of the Army. When Field Marshal Sugiyama complained to the Emperor about being fired and having the Prime Minister run the General Staff, the Emperor told him he supported Tojo. Tojo's major concern as Army Chief of Staff was planning the operations in China and India, with less time given over to the coming battles in the Marianas. Tojo decided to take the strategic offensive for 1944 with his plans to win the war in 1944 being as follows:

* Operation Ichigo would end the war with China, freeing up some 2 million Japanese soldiers.

* Operation U-Go

The U Go offensive, or Operation C (ウ号作戦 ''U Gō sakusen''), was the Japanese offensive launched in March 1944 against forces of the British Empire in the northeast Indian regions of Manipur and the Naga Hills (then administered as part ...

would take India.

* When the Americans made the expected offensive into the Marianas, the Imperial Navy's Combined Fleet would fight a decisive battle of annihilation against the U.S. 5th Fleet

The Fifth Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy. It has been responsible for naval forces in the Persian Gulf, Red Sea, Arabian Sea, and parts of the Indian Ocean since 1995 after a 48-year hiatus. It shares a commander and headq ...

, and halt the American drive in the central Pacific.

* In the Southwest Pacific, the Japanese forces in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands would stay on the defensive and try to slow down the American, Australian, and New Zealand forces for as long as possible. Knowing of General MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

's personal obsession with returning to the Philippines, Tojo expected MacArthur to head for the Philippines rather than the Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

(modern Indonesia), which was a relief from the Japanese viewpoint; the Dutch East Indies were rich in oil while the Philippines were not.

Tojo expected that a major American defeat in the Marianas combined with the conquest of China and India would so stun the Americans that they would sue for peace. By this point, Tojo no longer believed the war aims of 1942 could be achieved, but he believed that his plans for victory in 1944 would lead to a compromise peace that he could present as a victory to the Japanese people. By serving as Prime Minister, Army Minister and Army Chief of Staff, Tojo took on nearly all of the responsibility; if plans for victory in 1944 failed, he would have no scapegoat.

On March 12, 1944, the Japanese launched the U-Go offensive and invaded India. Tojo had some doubts about Operation U-Go, but it was ordered by the Emperor himself, and Tojo was unwilling to oppose any decision of the Emperor. Despite the Japanese Pan-Asian rhetoric and claim to be liberating India, the Indian people did not revolt and the Indian soldiers of the

On March 12, 1944, the Japanese launched the U-Go offensive and invaded India. Tojo had some doubts about Operation U-Go, but it was ordered by the Emperor himself, and Tojo was unwilling to oppose any decision of the Emperor. Despite the Japanese Pan-Asian rhetoric and claim to be liberating India, the Indian people did not revolt and the Indian soldiers of the 14th Army Fourteenth Army or 14th Army may refer to:

* 14th Army (German Empire), a World War I field Army

* 14th Army (Wehrmacht), a World War II field army

* Italian Fourteenth Army

* Japanese Fourteenth Army, a World War II field army, in 1944 converted ...

stayed loyal to their British officers, and the invasion of India ended in complete disaster. The Japanese were defeated by the Anglo-Indian 14th Army at the Battles of Imphal and Kohima. On July 5, 1944, the Emperor accepted Tojo's advice to end the invasion of India as 72,000 Japanese soldiers had been killed in battle. A similar number had starved to death or died of diseases as the logistics to support an invasion of India were lacking, once the monsoons turned the roads of Burma into impassable mud. Of the 150,000 Japanese soldiers who had participated in the March invasion of India, most were dead by July 1944.

In parallel with the invasion of India, in April 1944 Tojo began Operation Ichigo, the largest Japanese offensive of the entire war, with the aim of taking southern China.

In the Battle of Saipan

The Battle of Saipan was a battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II, fought on the island of Saipan in the Mariana Islands from 15 June to 9 July 1944 as part of Operation Forager. It has been referred to as the "Pacific D-Day" with the ...

, about 70,000 Japanese soldiers, sailors, and civilians were killed in June–July 1944 and in the Battle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944) was a major naval battle of World War II that eliminated the Imperial Japanese Navy's ability to conduct large-scale carrier actions. It took place during the United States' amphibious invas ...

the Imperial Navy suffered a crushing defeat. The first day of the Battle of the Philippine Sea, June 19, 1944, was dubbed by the Americans "the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot", as over the course of the dogfights in the air, the US Navy lost 30 planes while shooting down about 350 Imperial Japanese planes, in one of the Imperial Navy's most humiliating defeats. The Japanese believed that indoctrination in ''bushido

is a moral code concerning samurai attitudes, behavior and lifestyle. There are multiple bushido types which evolved significantly through history. Contemporary forms of bushido are still used in the social and economic organization of Japan. ...

'' ("the way of the warrior") would give them the edge as the Japanese longed to die for the Emperor, while the Americans were afraid to die, but superior American pilot training and airplanes meant the Japanese were hopelessly outclassed by the Americans. With Saipan in American hands, the Americans could take other islands in the Marianas to build airbases. The establishment of American bases in the Marianas meant the cities of Japan were within the range of B-29 Superfortress bombers and the British historian H. P. Willmott noted that "even the most hard-headed of the Japanese militarists could dimly perceive that Japan would be at the end of her tether in that case". As the news of the disastrous defeat suffered at Saipan reached Japan, it turned elite opinion against the Tojo government. The Emperor himself was furious about the defeat at Saipan; had called a meeting of the Board of Field Marshals and Fleet Admirals to consider whether it might be possible to recapture Saipan (it was not); and Prince Takamatsu wrote in his diary "he flares up frequently". Tojo was the Prime Minister, Minister of War and Chief of the Army General Staff, and was seen both in Japan and in the US as, in words of Willmott, "the embodiment of national determination, hardline nationalism and militarism". Prince Konoe and Admiral Okada had long been plotting to bring down the Tojo government since the spring of 1943, and their principal problem had been the support of the Emperor, who did not wish to lose his favorite Prime Minister.

After the Battle of Saipan, it was clear to at least some of the Japanese elite that the war was lost, and Japan needed to make peace before the ''kokutai

is a concept in the Japanese language translatable as " system of government", "sovereignty", "national identity, essence and character", "national polity; body politic; national entity; basis for the Emperor's sovereignty; Japanese constitu ...

'' and perhaps even the Chrysanthemum Throne

The is the throne of the Emperor of Japan. The term also can refer to very specific seating, such as the throne in the Shishin-den at Kyoto Imperial Palace.

Various other thrones or seats that are used by the Emperor during official functions ...

itself was destroyed. Tojo had been so demonized in the United States during the war that, for the American people, Tojo was the face of Japanese militarism, and it was inconceivable that the United States would make peace with a government headed by Tojo. Willmott noted that an additional problem for the "peace faction" was that: "Tojo was an embodiment of ''mainstream opinion'' within the nation, the armed services and particularly the Army. Tojo had powerful support, and by Japanese standards, he was not extreme." Tojo was more of a follower than a leader, and he represented mainstream opinion in the Army, and so his removal from office would not mean the end of the political ambitions of an Army still fanatically committed to victory or death. The ''jushin'' (elder statesmen) had advised the Emperor that Tojo needed to go after Saipan and further advised the Emperor against partial changes in the cabinet, demanding that the entire Tojo cabinet resign. Tojo, aware of the intrigues to bring him down, had sought the public approval of the Emperor, which was denied; the Emperor sent him a message to the effect that the man responsible for the disaster of Saipan was not worthy of his approval. Tojo suggested reorganizing his cabinet to regain Imperial approval, but was rebuffed again; the Emperor said the entire cabinet had to go. Once it was clear that Tojo no longer had the support of the Chrysanthemum Throne, Tojo's enemies had little trouble bringing down his government. The politically powerful Lord Privy Seal, Marquis Kōichi Kido spread the word that the Emperor no longer supported Tojo. After the fall of Saipan, he was forced to resign on July 18, 1944.

As Tojo's replacement, the ''jushin'' advised the Emperor to appoint a former Prime Minister, Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai

was a Japanese general and politician. He served as admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Minister of the Navy, and Prime Minister of Japan in 1940.

Early life and career

Yonai was born on 2 March 1880, in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, the firs ...

, as he was popular among the Navy, the diplomatic corps, the bureaucracy and the "peace faction". However Yonai refused to serve, knowing full well that a Prime Minister who attempted to make peace with the Americans might be assassinated, as many Army officers were still committed to victory or death and regarded any talk of peace as treason. He stated only another general could serve as Prime Minister, and recommended General Kuniaki Koiso

was a Japanese general in the Imperial Japanese Army, Governor-General of Korea and Prime Minister of Japan from 1944 to 1945.

After Japan's defeat in World War II, he was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early l ...

in his place. At a conference with the Emperor, Koiso and Yonai were told by the Emperor to co-operate in forming a new government, but left in the dark about who was to become Prime Minister. As the Emperor was worshiped as a living god, neither Yonai and Koiso could ask him who was to be the Prime Minister, as one does not ask questions of a god, and after the meeting, both men were very confused as to which of the two was now the Prime Minister. Finally Lord Privy Seal Kido resolved the muddle by saying Koiso was the Prime Minister. Two days after Tojo resigned, the Emperor gave him an imperial rescript offering him unusually lavish praise for his "meritorious services and hard work" and declaring "Hereafter we expect you to live up to our trust and make even greater contributions to military affairs".

Arrest, trial, and execution

After Japan's unconditional surrender in 1945, U.S. general

After Japan's unconditional surrender in 1945, U.S. general Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

ordered the arrest of forty individuals suspected of war crimes, including Tojo. Five American GIs were sent to serve the arrest warrant. As American soldiers surrounded Tojo's house on September 11, he shot himself in the chest with a pistol, but missed his heart. As a result of this experience, the Army had medical personnel present during the later arrests of other accused Japanese war criminals, such as Shigetarō Shimada

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. He also served as Minister of the Navy. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early life and education

A native of Tokyo, Shimada graduated from ...

.

As he bled, Tojo began to talk, and two Japanese reporters recorded his words: "I am very sorry it is taking me so long to die. The Greater East Asia War was justified and righteous. I am very sorry for the nation and all the races of the Greater Asiatic powers. I wait for the righteous judgment of history. I wished to commit suicide but sometimes that fails."

After recovering from his injuries, Tojo was moved to

After recovering from his injuries, Tojo was moved to Sugamo Prison

Sugamo Prison (''Sugamo Kōchi-sho'', Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: ) was a prison in Tokyo, Japan. It was located in the district of Ikebukuro, which is now part of the Toshima ward of Tokyo, Japan.

History

Sugamo Prison was originally built ...

. While there, he received a new set of dentures, made by an American dentist, into which the phrase "Remember Pearl Harbor" had been secretly drilled in Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

. The dentist ground away the message three months later.

Tojo was tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East