Herbert C. Brown on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Herbert Charles Brown (May 22, 1912 – December 19, 2004) was an American chemist and recipient of the 1979

As a doctoral student at the

As a doctoral student at the  When Brown started his own research, he observed the reactions of diborane with

When Brown started his own research, he observed the reactions of diborane with  While researching these reducing agents, Brown's coworker, Dr. B. C. Subba Rao, discovered an unusual reaction between sodium borohydride and

While researching these reducing agents, Brown's coworker, Dr. B. C. Subba Rao, discovered an unusual reaction between sodium borohydride and

Herbert Brown obituary

in

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

for his work with organoborane

Organoborane or organoboron compounds are chemical compounds of boron and carbon that are organic derivatives of BH3, for example trialkyl boranes. Organoboron chemistry or organoborane chemistry is the chemistry of these compounds.

Organoboron ...

s.

Life and career

Brown was born Herbert Brovarnik inLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants from Zhitomir, Pearl (''née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

'' Gorinstein) and Charles Brovarnik, a hardware store manager and carpenter. His family moved to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

in June 1914, when he was two years old. Brown attended Crane Junior College

Malcolm X College, one of the City Colleges of Chicago, is a two-year college located on the Near West Side of Chicago, Illinois. It was founded as Crane Junior College in 1911 and was the first of the City Colleges. Crane ceased operations at ...

in Chicago, where he met Sarah Baylen, whom he would later marry. The college was under threat of closing, and Brown and Baylen transferred to Wright Junior College

Wilbur Wright College, formerly known as Wright Junior College, is a public community college in Chicago. Part of the City Colleges of Chicago system, it offers two-year associate's degrees, as well as occupational training in IT, manufacturing, ...

. In 1935 he left Wright Junior College and that autumn entered the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

, completed two years of studies in three quarters, and earned a B.S. in 1936. That same year, he became a naturalized United States citizen. On February 6, 1937, Brown married Baylen, the person he credits with making him interested in hydrides of boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the '' boron group'' it has t ...

, a topic related to the work in which he, together with Georg Wittig, won the Nobel prize in Chemistry in 1979. Two years after starting graduate studies, he earned a Ph.D. in 1938, also from the University of Chicago.

Unable to find a position in industry, he decided to accept a postdoctoral position. This became the beginning of his academic career. He became an instructor at the University of Chicago in 1939, and held the position for four years before moving to Wayne University

Wayne State University (WSU) is a public research university in Detroit, Michigan. It is Michigan's third-largest university. Founded in 1868, Wayne State consists of 13 schools and colleges offering approximately 350 programs to nearly 25,0 ...

in Detroit as an assistant professor. In 1946, he was promoted to associate professor. He became a professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who professes". Professo ...

of inorganic chemistry

Inorganic chemistry deals with synthesis and behavior of inorganic and organometallic compounds. This field covers chemical compounds that are not carbon-based, which are the subjects of organic chemistry. The distinction between the two disci ...

at Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and ...

in 1947

and joined the Beta Nu chapter of Alpha Chi Sigma

Alpha Chi Sigma () is a professional fraternity specializing in the fields of the chemical sciences. It has both collegiate and professional chapters throughout the United States consisting of both men and women and numbering more than 70,000 me ...

there in 1960.

He held the position of Professor Emeritus

''Emeritus'' (; female: ''emerita'') is an adjective used to designate a retired chair, professor, pastor, bishop, pope, director, president, prime minister, rabbi, emperor, or other person who has been "permitted to retain as an honorary title ...

from 1978 until his death in 2004. The ''Herbert C. Brown Laboratory of Chemistry'' was named after him on Purdue University's campus. He was an honorary member of the International Academy of Science, Munich.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, while working with Hermann Irving Schlesinger, Brown discovered a method for producing sodium borohydride

Sodium borohydride, also known as sodium tetrahydridoborate and sodium tetrahydroborate, is an inorganic compound with the formula Na BH4. This white solid, usually encountered as an aqueous basic solution, is a reducing agent that finds applica ...

(NaBH4), which can be used to produce borane

Trihydridoboron, also known as borane or borine, is an unstable and highly reactive molecule with the chemical formula . The preparation of borane carbonyl, BH3(CO), played an important role in exploring the chemistry of boranes, as it indicated ...

s, compounds of boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the '' boron group'' it has t ...

and hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

. His work led to the discovery of the first general method for producing asymmetric pure enantiomer

In chemistry, an enantiomer ( /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''; from Ancient Greek ἐνάντιος ''(enántios)'' 'opposite', and μέρος ''(méros)'' 'part') – also called optical isomer, antipode, or optical anti ...

s. The elements found as initials of his name H, C and B were his working field.

In 1969, he was awarded the National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

.

Brown was quick to credit his wife Sarah with supporting him and allowing him to focus on creative efforts by handling finances, maintaining the house and yard, etc. According to Brown, after receiving the Nobel prize in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

, he carried the medal and she carried the US$100,000 award.

In 1971, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet ...

.

He was inducted into the Alpha Chi Sigma

Alpha Chi Sigma () is a professional fraternity specializing in the fields of the chemical sciences. It has both collegiate and professional chapters throughout the United States consisting of both men and women and numbering more than 70,000 me ...

Hall of Fame in 2000.

He died December 19, 2004, at a hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergen ...

in Lafayette, Indiana

Lafayette ( , ) is a city in and the county seat of Tippecanoe County, Indiana, United States, located northwest of Indianapolis and southeast of Chicago. West Lafayette, on the other side of the Wabash River, is home to Purdue University, whi ...

after a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

. His wife died May 29, 2005, aged 89.

Research

As a doctoral student at the

As a doctoral student at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

, Herbert Brown studied the reactions of diborane, B2H6. Hermann Irving Schlesinger's laboratory at the University of Chicago was one of two laboratories that prepared diborane. It was a rare compound that was only prepared in small quantities. Schlesinger was researching the reactions of diborane to understand why the simplest hydrogen-boron compound is B2H6 instead of BH3.

When Brown started his own research, he observed the reactions of diborane with

When Brown started his own research, he observed the reactions of diborane with aldehydes

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl grou ...

, ketones

In organic chemistry, a ketone is a functional group with the structure R–C(=O)–R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group –C(=O)– (which contains a carbon-oxygen double b ...

, esters

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ar ...

, and acid chlorides. He discovered that diborane reacts with aldehydes and ketones to produce dialkoxyboranes, which are hydrolyzed

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysis ...

by water to produce alcohols

In chemistry, an alcohol is a type of organic compound that carries at least one hydroxyl () functional group bound to a saturated carbon atom. The term ''alcohol'' originally referred to the primary alcohol ethanol (ethyl alcohol), which is ...

. Until this point, organic chemists did not have an acceptable method of reducing carbonyls

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups. A compound containing a ...

under mild conditions. Yet Brown's Ph.D. thesis published in 1939 received little interest. Diborane was too rare to be useful as a synthetic reagent.

In 1939, Brown became the research assistant in Schlesinger's laboratory. In 1940, they began to research volatile, low molecular weight uranium compounds for the National Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the Un ...

. Brown and Schlesinger successfully synthesized volatile uranium(IV) borohydride, which had a molecular weight of 298. The laboratory was asked to provide a large amount of the product for testing, but diborane was in short supply. They discovered that it could be formed by reacting lithium hydride with boron trifluoride

Boron trifluoride is the inorganic compound with the formula BF3. This pungent, colourless, and toxic gas forms white fumes in moist air. It is a useful Lewis acid and a versatile building block for other boron compounds.

Structure and bond ...

in ethyl ether, allowing them to produce the chemical in larger quantities. This success was met with several new problems. Lithium hydride was also in short supply, so Brown and Schlesinger needed to find a procedure that would allow them to use sodium hydride

Sodium hydride is the chemical compound with the empirical formula Na H. This alkali metal hydride is primarily used as a strong yet combustible base in organic synthesis. NaH is a saline (salt-like) hydride, composed of Na+ and H− ions, in ...

instead. They discovered that sodium hydride and methyl borate reacted to produce sodium trimethoxyborohydride, which was viable as a substitute for the lithium hydride.

Soon they were informed that there was no longer a need for uranium borohydride, but it appeared that sodium borohydride could be useful in generating hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

. They began to look for a cheaper synthesis and discovered that adding methyl borate to sodium hydride at 250° produced sodium borohydride and sodium methoxide. When acetone

Acetone (2-propanone or dimethyl ketone), is an organic compound with the formula . It is the simplest and smallest ketone (). It is a colorless, highly volatile and flammable liquid with a characteristic pungent odour.

Acetone is miscibl ...

was used in an attempt to separate the two products, it was discovered that sodium borohydride reduced the acetone.

Sodium borohydride is a mild reducing agent

In chemistry, a reducing agent (also known as a reductant, reducer, or electron donor) is a chemical species that "donates" an electron to an (called the , , , or ).

Examples of substances that are commonly reducing agents include the Earth met ...

that works well in reducing aldehydes, ketones, and acid chlorides. Lithium aluminum hydride is a much more powerful reducing agent that can reduce almost any functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is a substituent or moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions regardless of the r ...

. When Brown moved to Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and ...

in 1947, he worked to find stronger borohydrides and milder aluminum hydrides that would provide a spectrum of reducing agents. The team of researchers at Purdue discovered that changing the metal ion of the borohydride to lithium

Lithium (from el, λίθος, lithos, lit=stone) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense soli ...

, magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ...

, or aluminum

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It ha ...

increases the reducing ability. They also found that introducing alkoxy

In chemistry, the alkoxy group is an alkyl group which is singularly bonded to oxygen; thus . The range of alkoxy groups is vast, the simplest being methoxy (). An ethoxy group () is found in the organic compound ethyl phenyl ether (, also ...

substituents to the aluminum hydride decreases the reducing ability. They successfully developed a full spectrum of reducing agents.

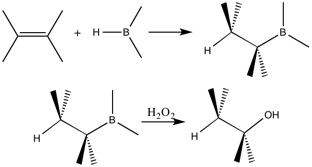

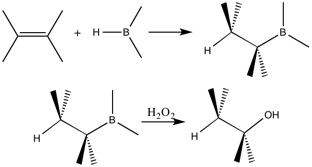

While researching these reducing agents, Brown's coworker, Dr. B. C. Subba Rao, discovered an unusual reaction between sodium borohydride and

While researching these reducing agents, Brown's coworker, Dr. B. C. Subba Rao, discovered an unusual reaction between sodium borohydride and ethyl oleate

Ethyl oleate is a fatty acid ester formed by the condensation of oleic acid and ethanol. It is a colorless oil although degraded samples can appear yellow.

Use and occurrence Additive

Ethyl oleate is used by compounding pharmacies as a vehicle f ...

. The borohydride added hydrogen and boron to the carbon-carbon double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betwee ...

in the ethyl oleate. The organoborane product could then be oxidized

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

to form an alcohol. This two-step reaction is now called hydroboration-oxidation and is a reaction that converts alkenes

In organic chemistry, an alkene is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond.

Alkene is often used as synonym of olefin, that is, any hydrocarbon containing one or more double bonds.H. Stephen Stoker (2015): General, Organic, a ...

into anti-Markovnikov alcohols. Markovnikov's rule

In organic chemistry, Markovnikov's rule or Markownikoff's rule describes the outcome of some addition reactions. The rule was formulated by Russian chemist Vladimir Markovnikov in 1870.

Explanation

The rule states that with the addition of a ...

states that, in adding hydrogen and a halide

In chemistry, a halide (rarely halogenide) is a binary chemical compound, of which one part is a halogen atom and the other part is an element or radical that is less electronegative (or more electropositive) than the halogen, to make a flu ...

or hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydrox ...

group to a carbon-carbon double bond, the hydrogen is added to the less-substituted carbon of the bond and the hydroxyl or halide group is added to the more-substituted carbon of the bond. In hydroboration-oxidation, the opposite addition occurs.

See also

*List of Jewish Nobel laureates

Nobel Prizes have been awarded to over 900 individuals, of whom at least 20% were Jews.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The number of Jews receiving Nobel prizes has been the subject of some attention.*

*

*"Jews rank high among winners of Nobel, but why ...

References

External links

*Herbert Brown obituary

in

Chemical & Engineering News

''Chemical & Engineering News'' (''C&EN'') is a weekly news magazine published by the American Chemical Society, providing professional and technical news and analysis in the fields of chemistry and chemical engineering.Herbert Brown obituary

in

National Academy of Sciences Biographical MemoirNobel Lecture

1979 {{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, Herbert C. 1912 births 2004 deaths Nobel laureates in Chemistry British Nobel laureates American Nobel laureates English Jews English people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent English emigrants to the United States American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent Jewish American scientists Jewish chemists Inorganic chemists Stereochemists Purdue University faculty Wayne State University faculty University of Chicago alumni National Medal of Science laureates Wilbur Wright College alumni

in

USA Today

''USA Today'' (stylized in all uppercase) is an American daily middle-market newspaper and news broadcasting company. Founded by Al Neuharth on September 15, 1982, the newspaper operates from Gannett's corporate headquarters in Tysons, Virgini ...

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

1979 {{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, Herbert C. 1912 births 2004 deaths Nobel laureates in Chemistry British Nobel laureates American Nobel laureates English Jews English people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent English emigrants to the United States American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent Jewish American scientists Jewish chemists Inorganic chemists Stereochemists Purdue University faculty Wayne State University faculty University of Chicago alumni National Medal of Science laureates Wilbur Wright College alumni