Henry A. Wallace on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

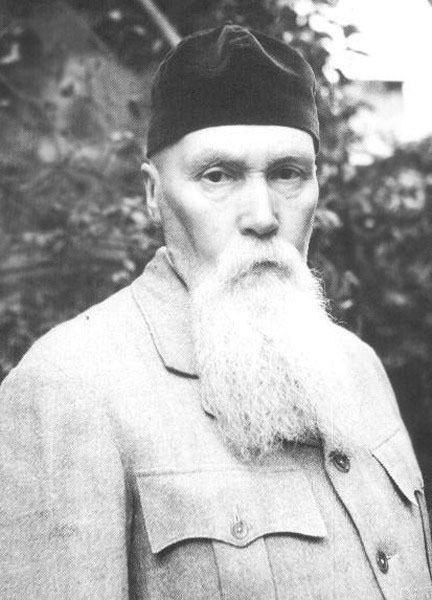

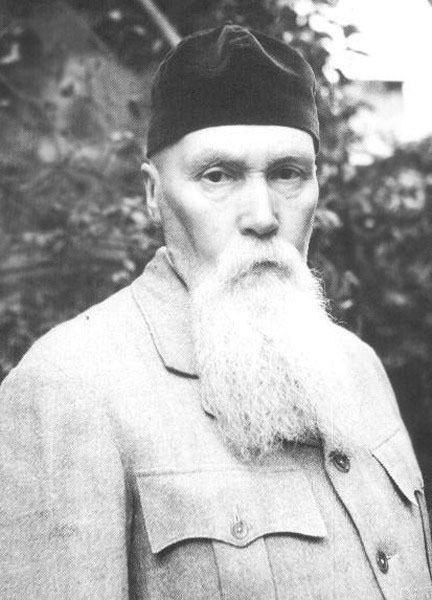

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd

Wallace became a full-time writer and editor for ''Wallace's Farmer'' after graduating from college in 1910. He was deeply interested in using mathematics and economics in agriculture and learned

Wallace became a full-time writer and editor for ''Wallace's Farmer'' after graduating from college in 1910. He was deeply interested in using mathematics and economics in agriculture and learned

As Roosevelt refused to commit to either retiring or seeking reelection during his second term, supporters of Wallace and other leading Democrats such as Vice President John Nance Garner and Postmaster General

As Roosevelt refused to commit to either retiring or seeking reelection during his second term, supporters of Wallace and other leading Democrats such as Vice President John Nance Garner and Postmaster General

Wallace was sworn in as vice president on January 20, 1941. He quickly grew frustrated with his ceremonial role as the presiding officer of the

Wallace was sworn in as vice president on January 20, 1941. He quickly grew frustrated with his ceremonial role as the presiding officer of the

Wallace believed that Democratic party leaders had unfairly stolen the vice-presidential nomination from him, but he supported Roosevelt in the 1944 presidential election. Hoping to mend ties with Wallace, Roosevelt offered him any position in the Cabinet other than secretary of state, and Wallace asked to replace Jones as secretary of commerce. In that position, Wallace expected to play a key role in the economy's postwar transition. In January 1945, with the end of Wallace's vice presidency, Roosevelt nominated Wallace for secretary of commerce. The nomination prompted an intense debate, as many senators objected to his support for liberal policies designed to boost wages and employment. Conservatives failed to block the nomination, but Senator Walter F. George led passage of a measure removing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation from the

Wallace believed that Democratic party leaders had unfairly stolen the vice-presidential nomination from him, but he supported Roosevelt in the 1944 presidential election. Hoping to mend ties with Wallace, Roosevelt offered him any position in the Cabinet other than secretary of state, and Wallace asked to replace Jones as secretary of commerce. In that position, Wallace expected to play a key role in the economy's postwar transition. In January 1945, with the end of Wallace's vice presidency, Roosevelt nominated Wallace for secretary of commerce. The nomination prompted an intense debate, as many senators objected to his support for liberal policies designed to boost wages and employment. Conservatives failed to block the nomination, but Senator Walter F. George led passage of a measure removing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation from the

Wallace was raised a

Wallace was raised a

vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

. He was the nominee of the new Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

in the 1948 presidential election.

The oldest son of Henry C. Wallace, who served as U.S. Secretary of Agriculture from 1921 to 1924, Henry A. Wallace was born in rural Iowa in 1888. After graduating from Iowa State University

Iowa State University of Science and Technology (Iowa State University, Iowa State, or ISU) is a public land-grant research university in Ames, Iowa. Founded in 1858 as the Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm, Iowa State became one of the ...

in 1910, he worked as a writer and editor for his family's farm journal, ''Wallaces' Farmer

Farm Progress is the publisher of 22 farming and ranching magazines. The company dates back nearly 200 years. Farm Progress Companies is owned by Informa.

Farm Progress has the oldest known continuously published magazine, ''Prairie Farmer'', whi ...

''. He also founded the Hi-Bred Corn Company, a hybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two dif ...

corn company that became extremely successful. Wallace displayed intellectual curiosity about a wide array of subjects, including statistics and economics, and explored various religious and spiritual movements, including Theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion ...

. After his father's death in 1924, Wallace drifted away from the Republican Party; he supported Democratic nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

in the 1932 presidential election.

Wallace served as Secretary of Agriculture under Roosevelt from 1933 to 1940. He strongly supported the New Deal and presided over a major shift in federal agricultural policy, implementing measures designed to curtail agricultural surpluses and to ameliorate rural poverty. Roosevelt overcame strong opposition from conservative leaders in the Democratic Party and had Wallace nominated for vice president at the 1940 Democratic National Convention

The 1940 Democratic National Convention was held at the Chicago Stadium in Chicago, Illinois from July 15 to July 18, 1940. The convention resulted in the nomination of President Franklin D. Roosevelt for an unprecedented third term. Secretary o ...

. The Roosevelt-Wallace ticket won the 1940 presidential election. At the 1944 Democratic National Convention

The 1944 Democratic National Convention was held at the Chicago Stadium in Chicago, Illinois from July 19 to July 21, 1944. The convention resulted in the nomination of President Franklin D. Roosevelt for an unprecedented fourth term. Senator ...

, conservative party leaders defeated Wallace's bid for renomination, placing Missouri Senator Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

on the Democratic ticket instead. In early 1945, Roosevelt appointed Wallace as Secretary of Commerce.

Roosevelt died in April 1945 and Truman succeeded him as president. Wallace continued to serve as Secretary of Commerce until September 1946, when he was fired by Truman for delivering a speech urging conciliatory policies toward the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Wallace and his supporters then established the nationwide Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

and launched a third-party campaign for president. The Progressive platform called for conciliatory policies toward the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, desegregation of public schools, racial

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

and gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing d ...

, a national health-insurance program, and other left-wing policies. Accusations of Communist influence followed, and Wallace's association with controversial Theosophist figure Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich (; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), also known as Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (russian: link=no, Никола́й Константи́нович Ре́рих), was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophi ...

undermined his campaign; he received just 2.4% of the popular vote. Wallace broke with the Progressive Party in 1950 over the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, and in a 1952 article he called the Soviet Union "utterly evil". Turning his attention back to agricultural innovation, he became a highly successful businessman. He specialized in developing and marketing hybrid seed corn and improved chickens before his death in 1965 of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Early life and education

Henry Agard Wallace was born on October 7, 1888, on a farm nearOrient, Iowa

Orient is a city in Orient Township, Adair County, Iowa, United States. The population was 368 at the time of the 2020 census.

History

Orient was incorporated on March 21, 1882, on land set aside by the nearby Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Ra ...

, to Henry Cantwell Wallace and his wife, May. Wallace had two younger brothers and three younger sisters. His paternal grandfather, "Uncle Henry" Wallace, was a prominent landowner, newspaper editor, Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

activist, and Social Gospel advocate in Adair County, Iowa. Uncle Henry's father, John Wallace, was an Ulster-Scots immigrant from the village Kilrea

Kilrea ( , ) is a village, townland and civil parish in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It gets its name from the ancient church that was located near to where the current Church of Ireland is located on Church Street looking over the tow ...

in County Londonderry, Ireland, who arrived in Philadelphia in 1823. May (née Broadhead) was born in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

but was raised by an aunt in Muscatine, Iowa

Muscatine ( ) is a city in Muscatine County, Iowa, United States. The population was 23,797 at the time of the 2020 census, an increase from 22,697 in 2000. The county seat of Muscatine County, it is located along the Mississippi River. The lo ...

, after her parents' death.

Wallace's family moved to Ames, Iowa, in 1892 and to Des Moines, Iowa

Des Moines () is the capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Iowa. It is also the county seat of Polk County. A small part of the city extends into Warren County. It was incorporated on September 22, 1851, as Fort Des Moines, ...

, in 1896. In 1894, the Wallaces established an agricultural newspaper, '' Wallace's Farmer''. It became extremely successful and made the family wealthy and politically influential. Wallace took a strong interest in agriculture and plants from a young age and befriended African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

botanist George Washington Carver, with whom he frequently discussed plants and other subjects. Wallace was particularly interested in corn, Iowa's key crop. In 1904, he devised an experiment that disproved agronomist Perry Greeley Holden's assertion that the most aesthetically pleasing corn would produce the greatest yield. Wallace graduated from West High School in 1906 and enrolled in Iowa State College

Iowa State University of Science and Technology (Iowa State University, Iowa State, or ISU) is a public land-grant research university in Ames, Iowa. Founded in 1858 as the Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm, Iowa State became one of the n ...

later that year, majoring in animal husbandry. He joined the Hawkeye Club, a fraternal organization, and spent much of his free time continuing to study corn. He also organized a political club to support Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

, a Progressive Republican who was head of the United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands. The Forest Service manages of land. Major divisions of the agency in ...

.

Journalist and farmer

Wallace became a full-time writer and editor for ''Wallace's Farmer'' after graduating from college in 1910. He was deeply interested in using mathematics and economics in agriculture and learned

Wallace became a full-time writer and editor for ''Wallace's Farmer'' after graduating from college in 1910. He was deeply interested in using mathematics and economics in agriculture and learned calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithm ...

as part of an effort to understand hog prices. He also wrote an influential article with pioneering statistician George W. Snedecor

George Waddel Snedecor (October 20, 1881 – February 15, 1974) was an American mathematician and statistician. He contributed to the foundations of analysis of variance, data analysis, experimental design, and statistical methodology. Snedecor ...

on computational methods for correlations and regressions. After his grandfather died in 1916, Wallace and his father became the coeditors of ''Wallace's Farmer''. In 1921, Wallace assumed leadership of the paper after his father accepted an appointment as Secretary of Agriculture under President Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

. His uncle lost ownership of the paper in 1932 during the Great Depression, and Wallace stopped serving as editor in 1933.

In 1914, Wallace and his wife purchased a farm near Johnston, Iowa; they initially attempted to combine corn production with dairy farming, but later turned their full attention to corn. Influenced by Edward Murray East

Edward Murray East (October 4, 1879 – November 9, 1938) was an American plant geneticist, botanist, agronomist and eugenicist. He is known for his experiments that led to the development of hybrid corn and his support of 'forced' elimina ...

, Wallace focused on producing hybrid corn, developing a variety called Copper Cross. In 1923, he reached the first-ever contract for hybrid seed production, agreeing to grant the Iowa Seed Company the sole right to grow and sell Copper Cross corn. In 1926, he co-founded the Hi-Bred Corn Company to develop and produce hybrid corn. It initially turned only a small profit, but eventually became a massive financial success.

Early political involvement

DuringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Wallace and his father helped the United States Food Administration

The United States Food Administration (1917–1920) was an independent Federal agency that controlled the production, distribution and conservation of food in the U.S. during the nation's participation in World War I. It was established to preve ...

(USFA) develop policies to increase hog production. After USFA director Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

abandoned the hog production policies the Wallaces favored, the elder Wallace joined an effort to deny Hoover the presidential nomination at the 1920 Republican National Convention. Partly in response to Hoover, Wallace published ''Agricultural Prices'', in which he advocated government policies to control agricultural prices. He also warned farmers of an imminent price collapse after the war. Wallace's prediction proved accurate: a farm crisis extended into the 1920s. Reflecting a broader decrease in agricultural prices, the corn prices fell from $1.68 per bushel in 1918 to $0.42 per bushel in 1921. Wallace proposed various remedies to combat the farm crisis, which he believed stemmed primarily from overproduction. Among his proposed policies was the " ever-normal granary": the government buys and stores agricultural surpluses when agricultural prices are low and sells them when they are high.

Both Wallaces backed the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill

The McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Act, which never became law, was a controversial plan in the 1920s to subsidize American agriculture by raising the domestic prices of five crops. The plan was for the government to buy each crop and then store it o ...

, which would have required the federal government to market and export agricultural surpluses in foreign markets. The bill was defeated in large part because of the opposition of President Calvin Coolidge, who became president after Harding's death in 1923. Wallace's father died in October 1924, and in the November 1924 presidential election, Henry Wallace voted for the Progressive nominee, Robert La Follette

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

. Due, in part, to Wallace's continued lobbying, Congress passed the McNary–Haugen bill in 1927 and 1928, but Coolidge vetoed the bill both times. Dissatisfied with both major party candidates in the 1928 presidential election

The following elections occurred in the year 1928.

Africa

* 1928 Southern Rhodesian general election

Asia

* 1928 Japanese general election

* 1928 Persian legislative election

* 1928 Philippine House of Representatives elections

* 1928 Philippin ...

, Wallace tried to get Illinois Governor Frank Lowden

Frank Orren Lowden (January 26, 1861 – March 20, 1943) was an American Republican Party politician who served as the 25th Governor of Illinois and as a United States Representative from Illinois. He was also a candidate for the Republican pres ...

to run for president. He ultimately supported Democratic nominee Al Smith, but Hoover won a landslide victory. The onset of the Great Depression during Hoover's administration devastated Iowa farmers as farm income fell by two-thirds from 1929 to 1932. In the 1932 presidential election, Wallace campaigned for Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, who favored the agricultural policies of Wallace and economist M. L. Wilson. He did not formally register as a Democrat until 1936.

Secretary of Agriculture

After Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election, he appointed Wallace as secretary of agriculture. Despite his past affiliation with the Republican Party, Wallace strongly supported Roosevelt and his New Deal domestic program, and became a registered member of the Democratic Party in 1936. Upon taking office, Wallace appointedRexford Tugwell

Rexford Guy Tugwell (July 10, 1891 – July 21, 1979) was an American economist who became part of Franklin D. Roosevelt's first "Brain Trust", a group of Columbia University academics who helped develop policy recommendations leading up to R ...

, a member of Roosevelt's "Brain Trust

Brain trust was a term that originally described a group of close advisers to a political candidate or incumbent; these were often academics who were prized for their expertise in particular fields. The term is most associated with the group of ad ...

" of important advisers, as his deputy secretary. Though Roosevelt was initially focused primarily on addressing the banking crisis, Wallace and Tugwell convinced him of the necessity of quickly passing major agricultural reforms. Roosevelt, Wallace, and House Agriculture Committee Chairman John Marvin Jones

John Marvin Jones (February 26, 1882 – March 4, 1976) was a United States representative from Texas and a Judge of the United States Court of Claims.

Education and career

Born on February 26, 1882, in Valley View, Cooke County, Texas, Jone ...

rallied congressional support around the Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was a United States federal law of the New Deal era designed to boost agricultural prices by reducing surpluses. The government bought livestock for slaughter and paid farmers subsidies not to plant on par ...

, which established the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). The AAA's aim was to raise prices for commodities through artificial scarcity by using a system of "domestic allotments" that set the total output of agricultural products. It paid land owners subsidies to leave some of their land idle. Farm income increased significantly in the first three years of the New Deal, as prices for commodities rose. After the Agricultural Adjustment Act passed, Agriculture became the federal government's largest department.

The Supreme Court struck down the Agricultural Adjustment Act in the 1936 case '' United States v. Butler''. Wallace strongly disagreed with the Court's holding that agriculture was a "purely local activity" and thus could not be regulated by the federal government, saying, "were agriculture truly a local matter in 1936, as the Supreme Court says it is, half of the people of the United States would quickly starve." He quickly proposed a new agriculture program designed to satisfy the Supreme Court's objections; under the new program, the federal government would reach rental agreements with farmers to plant green manure rather than crops like corn and wheat. Less than two months after the Supreme Court decided ''United States v. Butler'', Roosevelt signed the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act of 1936

The Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act , enacted February 29, 1936) is a United States federal law that allowed the government to pay farmers to reduce production so as to conserve soil and prevent erosion.

Legislative history

The Act ...

into law. In the 1936 presidential election, Wallace was an important surrogate in Roosevelt's campaign.

In 1935, Wallace fired general counsel Jerome Frank and some other Agriculture Department officials who sought to help Southern sharecroppers

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

by issuing a reinterpretation of the Agricultural Adjustment Act. He became more committed to aiding sharecroppers and other groups of impoverished farmers during a trip to the South in late 1936, after which he wrote, "I have never seen among the peasantry of Europe poverty so abject as that which exists in this favorable cotton year in the great cotton states." He helped lead passage of the Bankhead–Jones Farm Tenant Act of 1937, which authorized the federal government to issue loans to tenant farmers so that they could purchase land and equipment. The law also established the Farm Security Administration, which was charged with ameliorating rural poverty, within the Agriculture Department. The failure of Roosevelt's Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, frequently called the "court-packing plan",Epstein, at 451. was a legislative initiative proposed by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to add more justices to the U.S. Supreme Court in order t ...

(the "court-packing plan"), the onset of the Recession of 1937–38, and a wave of strikes led by John L. Lewis badly damaged the Roosevelt administration's ability to pass major legislation after 1936. Nonetheless, Wallace helped lead passage of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, which implemented Wallace's ever-normal granary plan. Between 1932 and 1940, the Agriculture Department grew from 40,000 employees and an annual budget of $280 million to 146,000 employees and an annual budget of $1.5 billion.

A Republican wave

In physics, mathematics, and related fields, a wave is a propagating dynamic disturbance (change from equilibrium) of one or more quantities. Waves can be periodic, in which case those quantities oscillate repeatedly about an equilibrium (re ...

in the 1938 elections

The following elections occurred in the year 1938.

Africa

* 1938 South African general election

Asia

* 1938 Philippine general election

* 1938 Philippine legislative election

* 1938 Soviet Union regional elections

Europe

* 1938 Estonian parl ...

effectively brought an end to the New Deal legislative program, and the Roosevelt administration increasingly focused on foreign policy. Unlike many Midwestern progressives, Wallace supported internationalist

Internationalist may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Liberal internationalism, a doctrine in international relations

* Internationalist/Defencist Schism, socialists opposed to ...

policies, such as Secretary of State Cordell Hull's efforts to lower tariffs. He joined Roosevelt in attacking the aggressive actions of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

, and in one speech derided Nazi eugenics

Nazi eugenics refers to the social policies of eugenics in Nazi Germany, composed of various pseudoscientific ideas about genetics. The racial ideology of Nazism placed the biological improvement of the German people by selective breeding of ...

as a "mumbo-jumbo of dangerous nonsense." After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

broke out in September 1939, Wallace supported Roosevelt's program of military buildup and, anticipating hostilities with Germany, pushed for initiatives like a synthetic rubber program and closer trade relations with Latin American

Latin Americans ( es, Latinoamericanos; pt, Latino-americanos; ) are the citizens of Latin American countries (or people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America). Latin American countries and their diasporas are multi-eth ...

countries.

Vice presidency (1941–1945)

Election of 1940

James Farley

James Aloysius Farley (May 30, 1888 – June 9, 1976) was an American politician and Knight of Malta who simultaneously served as chairman of the New York State Democratic Committee, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and Postmaste ...

laid the groundwork for a presidential campaign in the 1940 election. After the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

in Europe in September 1939, Wallace publicly endorsed a third term for Roosevelt. Though Roosevelt never declared his candidacy, the 1940 Democratic National Convention

The 1940 Democratic National Convention was held at the Chicago Stadium in Chicago, Illinois from July 15 to July 18, 1940. The convention resulted in the nomination of President Franklin D. Roosevelt for an unprecedented third term. Secretary o ...

nominated him for president. Shortly after being nominated, Roosevelt told party leaders that he insisted on Wallace for vice president. A recent convert to the Democratic Party, Wallace was not popular among its leaders and had never been tested in an election. But he had a strong base of support among farmers, had been a loyal lieutenant to Roosevelt in domestic and foreign policy, and was in good health. Roosevelt convinced James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes ( ; May 2, 1882 – April 9, 1972) was an American judge and politician from South Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in U.S. Congress and on the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in the executive branch, ...

, Paul V. McNutt, and other contenders for the vice-presidential nomination to support Wallace, but conservative Democrats rallied around the candidacy of Speaker of the House William B. Bankhead

William Brockman Bankhead (April 12, 1874 – September 15, 1940) was an American politician who served as the 42nd speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1936 to 1940, representing Alabama's 10th and later 7th congressiona ...

. Eventually, Wallace won the nomination by a wide margin.

Though many Democrats were disappointed by Wallace's nomination, it was generally well received by newspapers. Arthur Krock of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' wrote that Wallace was "able, thoughtful, honorable–the best of the New Deal type." Wallace left office as Secretary of Agriculture in September 1940, and was succeeded by Undersecretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard. The Roosevelt campaign settled on a strategy of keeping Roosevelt largely out of the fray of the election, leaving most of the campaigning to Wallace and other surrogates. Wallace was dispatched to the Midwest, giving speeches in states like Iowa, Illinois, and Missouri. He made foreign affairs the main focus of his campaigning, telling one audience that "the replacement of Roosevelt ... would cause dolfHitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

to rejoice." Both campaigns predicted a close election, but Roosevelt won 449 of the 531 electoral votes and the popular vote by nearly ten points. After the election, Wallace toured Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

as a goodwill ambassador, delivering a well-received speech regarding Pan-Americanism

Pan-Americanism is a movement that seeks to create, encourage, and organize relationships, associations and cooperation among the states of the Americas, through diplomatic, political, economic, and social means.

History

Following the indepen ...

and Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy

The Good Neighbor policy ( ) was the foreign policy of the administration of United States President Franklin Roosevelt towards Latin America. Although the policy was implemented by the Roosevelt administration, President Woodrow Wilson had prev ...

. Upon his return, Wallace convinced the Rockefeller Foundation to establish an agricultural experiment center in Mexico, the first of many such centers the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the death ...

established.

Tenure

Wallace was sworn in as vice president on January 20, 1941. He quickly grew frustrated with his ceremonial role as the presiding officer of the

Wallace was sworn in as vice president on January 20, 1941. He quickly grew frustrated with his ceremonial role as the presiding officer of the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

, the one duty the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

assigns the vice president. In July 1941, Roosevelt named Wallace chairman of the Board of Economic Warfare (BEW) and of the Supply Priorities and Allocations Board

The Supply Priorities and Allocations Board (SPAB) was a United States administrative entity within the Office for Emergency Management which was created and dissolved during World War II. The board was created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt ...

(SPAB). These appointments gave him a voice in organizing national mobilization for war. One journalist noted that Roosevelt made Wallace the first "Vice President to work really as the number two man in government–a conception of the vice presidency popularly held but never realized." Reflecting Wallace's role in organizing mobilization efforts, many journalists began calling him the "Assistant President." Wallace was also named to the Top Policy Group, which advised Roosevelt on the development of nuclear weapons, an initiative Wallace supported. He did not hold any official role in the subsequent Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, which developed the first nuclear weapons, but he was informed of its progress.

Economic conditions became chaotic, and Roosevelt decided new leadership was needed. In early 1942 he established the War Production Board

The War Production Board (WPB) was an agency of the United States government that supervised war production during World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established it in January 1942, with Executive Order 9024. The WPB replaced the Su ...

with businessman Donald Nelson in charge as Wallace became a minor member of the War Production Board. He continued to serve as head of the BEW, which was now far less important: it was now charged with importing the raw materials such as rubber necessary for war production. Wallace struggled to carve out authority for the BEW, demanding that American purchases in Latin America raise the standard of living of the workers. In the process he clashed privately with Secretary of State Cordell Hull, who opposed American interference in another state's internal affairs. The national media dramatically covered Wallace's public battle with Jesse H. Jones, the Secretary of Commerce who was also in charge of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), which paid the purchases bills BEW made. Roosevelt's standard strategy for executive management was to give two different people the same role, expecting controversy would result. He wanted the agencies' heads to bring the controversy to him so he could make the decision. On August 21, 1942, Roosevelt explicitly wrote to all his department heads that disagreements "should not be publicly aired, but are to be submitted to me by the appropriate heads of the conflicting agencies." Anyone going public had to resign. Wallace denounced Jones for blocking funding for purchases of raw materials in Latin America needed for the war effort. Jones called on Congress and the public for help, calling Wallace a liar. According to James MacGregor Burns

James MacGregor Burns (August 3, 1918 – July 15, 2014) was an American historian and political scientist, presidential biographer, and authority on leadership studies. He was the Woodrow Wilson Professor of Government Emeritus at Williams Col ...

, Jones, a leader of Southern conservative Democrats, was "taciturn, shrewd, practical, cautious". Wallace, deeply distrusted by Democratic party leaders, was the "hero of the Lib Labs, dreamy, utopian, even mystical, yet with his own bent for management and power." On July 15, 1943, Roosevelt stripped both men of their roles in the matter. BEW was reorganized as the Office of Economic Warfare

The Office of Administrator of Export Control (also referred to as the Export Control Administration) was established in the United States by Presidential Proclamation 2413, July 2, 1940, to administer export licensing provisions of the act of July ...

, and put under Leo Crowley

Leo Thomas Crowley (August 15, 1889 – April 15, 1972) was a senior administrator for President Franklin D. Roosevelt as the head of the Foreign Economic Administration. Previously he had served as Alien Property Custodian and as chief o ...

. The loss of the BEW was a major blow to Wallace's prestige. He now had no agency and a weak political base on the left wing of the Democratic Party. But he still had visibility, ambition and an articulate voice, and remained a loyal Roosevelt supporter. He was not renominated for vice president but in 1945 Roosevelt fired Jones and made Wallace Secretary of Commerce.

On May 8, 1942, Wallace delivered what became his best-remembered speech, known for containing the phrase "the Century of the Common Man". He cast World War II as a war between a "free world" and a "slave world," and held that "peace must mean a better standard of living for the common man, not merely in the United States and England, but also in India, Russia, China, and Latin America–not merely in the United Nations, but also in Germany and Italy and Japan". Some conservatives disliked the speech, but it was translated into 20 languages and millions of copies were distributed around the world.

In early 1943, Wallace was dispatched on a goodwill tour of Latin America; he made 24 stops across Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

and South America. Partly due to his ability to deliver speeches in Spanish, Wallace received a warm reception; one State Department official said, "never in Chilean history has any foreigner ever been received with such extravagance and evidently sincere enthusiasm". During his trip, several Latin American countries declared war against Germany. Back home, Wallace continued to deliver speeches, saying after the Detroit race riot of 1943, "we cannot fight to crush Nazi brutality abroad and condone race riots at home". Though Congress largely blocked Roosevelt's domestic agenda, Wallace continued to call for progressive programs; one newspaper wrote that "the New Deal today is Henry Wallace ... the New Deal banner in his hands is not yet furled".

In mid-1944, Wallace toured the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and China. The USSR presented its American guests with a fully sanitized version of labor camps in Magadan and Kolyma, claiming that all the workers were volunteers. Wallace was impressed by the camp at Magadan, describing it as a "combination Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

and Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

".Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 339 He received a warm reception in the Soviet Union, but was largely unsuccessful in his efforts to negotiate with Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek.

Election of 1944

After the abolition of the BEW, speculation began as to whether Roosevelt would drop Wallace from the ticket in the 1944 election. Gallup polling published in March 1944 showed that Wallace was clearly the most popular choice for vice president among Democrats, and many journalists predicted that he would win renomination. As Roosevelt was in declining health, party leaders expected that the party's vice-presidential nominee would eventually succeed Roosevelt, and Wallace's many enemies within the Democratic Party organized to ensure his removal. Much of the opposition to Wallace stemmed from his open denunciation ofracial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in the South, but others were concerned by Wallace's unorthodox religious views and pro-Soviet statements. Shortly before the 1944 Democratic National Convention

The 1944 Democratic National Convention was held at the Chicago Stadium in Chicago, Illinois from July 19 to July 21, 1944. The convention resulted in the nomination of President Franklin D. Roosevelt for an unprecedented fourth term. Senator ...

, party leaders such as Robert E. Hannegan

Robert Emmet Hannegan (June 30, 1903 – October 6, 1949) was an American politician who served as Commissioner of Internal Revenue from October 1943 to January 1944. He also served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1944 to 19 ...

and Edwin W. Pauley convinced Roosevelt to sign a document expressing support for either Associate Justice William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often ci ...

or Senator Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

for the vice-presidential nomination. Nonetheless, Wallace got Roosevelt to send a public letter to the convention chairman in which he wrote, "I personally would vote for allace'srenomination if I were a delegate to the convention".

With Roosevelt not committed to keeping or dropping Wallace, the vice-presidential balloting turned into a battle between those who favored Wallace and those who favored Truman. Wallace did not have an effective organization to support his candidacy, though allies like Calvin Benham Baldwin

Calvin Benham Baldwin, also known as Calvin B Baldwin, C.B. Baldwin, and generally as "Beanie" Baldwin (August 19, 1902 – May 12, 1975), served as assistant to US Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace and administrator of the New Deal's Fa ...

, Claude Pepper

Claude Denson Pepper (September 8, 1900 – May 30, 1989) was an American politician of the Democratic Party, and a spokesman for left-liberalism and the elderly. He represented Florida in the United States Senate from 1936 to 1951, and the Mi ...

, and Joseph F. Guffey pressed for him. Truman, meanwhile, was reluctant to put forward his own candidacy, but Hannegan and Roosevelt convinced him to run. At the convention, Wallace galvanized supporters with a well-received speech in which he lauded Roosevelt and argued that "the future belongs to those who go down the line unswervingly for the liberal principles of both political democracy and economic democracy regardless of race, color, or religion". After Roosevelt delivered his acceptance speech, the crowd began chanting for the nomination of Wallace, but Samuel D. Jackson adjourned the convention for the day before Wallace supporters could call for the beginning of vice presidential balloting. Party leaders worked furiously to line up support for Truman overnight, but Wallace received 429 1/2 votes (589 were needed for nomination) on the first ballot for vice president and Truman 319 1/2, with the rest going to various favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

candidates. On the second ballot, many delegates who had voted for favorite sons shifted into Truman's camp, giving him the nomination.

On January 20, 1945, Wallace swore in Truman as his vice-presidential successor.

Secretary of Commerce (1945–1946)

Wallace believed that Democratic party leaders had unfairly stolen the vice-presidential nomination from him, but he supported Roosevelt in the 1944 presidential election. Hoping to mend ties with Wallace, Roosevelt offered him any position in the Cabinet other than secretary of state, and Wallace asked to replace Jones as secretary of commerce. In that position, Wallace expected to play a key role in the economy's postwar transition. In January 1945, with the end of Wallace's vice presidency, Roosevelt nominated Wallace for secretary of commerce. The nomination prompted an intense debate, as many senators objected to his support for liberal policies designed to boost wages and employment. Conservatives failed to block the nomination, but Senator Walter F. George led passage of a measure removing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation from the

Wallace believed that Democratic party leaders had unfairly stolen the vice-presidential nomination from him, but he supported Roosevelt in the 1944 presidential election. Hoping to mend ties with Wallace, Roosevelt offered him any position in the Cabinet other than secretary of state, and Wallace asked to replace Jones as secretary of commerce. In that position, Wallace expected to play a key role in the economy's postwar transition. In January 1945, with the end of Wallace's vice presidency, Roosevelt nominated Wallace for secretary of commerce. The nomination prompted an intense debate, as many senators objected to his support for liberal policies designed to boost wages and employment. Conservatives failed to block the nomination, but Senator Walter F. George led passage of a measure removing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation from the Commerce Department

The United States Department of Commerce is an executive department of the U.S. federal government concerned with creating the conditions for economic growth and opportunity. Among its tasks are gathering economic and demographic data for busin ...

. After Roosevelt signed George's bill, Wallace was confirmed by a vote of 56 to 32 on March 1, 1945.

Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and was succeeded by Truman. Truman quickly replaced most other senior Roosevelt appointees, but retained Wallace, who remained very popular with liberal Democrats. The discontent of liberal leaders strengthened Wallace's position in the Cabinet; Truman privately stated that the two most important members of his "political team" were Wallace and Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

. As secretary of commerce, Wallace advocated a "middle course" between the planned economy of the Soviet Union and the laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

economics that had dominated the United States before the Great Depression. With his congressional allies, he led passage of the Employment Act of 1946. Conservatives blocked the inclusion of a measure providing for full employment, but the act established the Council of Economic Advisers and the Joint Economic Committee to study economic matters. Wallace's proposal to establish international control over nuclear weapons was not adopted, but he did help pass the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which established the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

to oversee domestic development of nuclear power.

World War II ended in September 1945 with the Surrender of Japan, and relations with the USSR became a central matter of foreign policy. Various issues, including the fate of European and Asian postwar governments and the administration of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

, had already begun to strain the wartime alliance between the Soviet Union and the United States. Critics of the USSR objected to the oppressive satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbitin ...

s it had established in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

and Soviet involvement in the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος}, ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom and ...

and the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

. In February 1946, George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

laid out the doctrine of containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which wa ...

, which called for the United States to resist the spread of Communism. Wallace feared that confrontational policies toward the Soviet Union would eventually lead to war, and urged Truman to "allay any reasonable Russian grounds for fear, suspicion, and distrust". Historian Tony Judt

Tony Robert Judt ( ; 2 January 1948 – 6 August 2010) was a British-American historian, essayist and university professor who specialized in European history. Judt moved to New York and served as the Erich Maria Remarque Professor in European ...

wrote in ''Postwar

In Western usage, the phrase post-war era (or postwar era) usually refers to the time since the end of World War II. More broadly, a post-war period (or postwar period) is the interval immediately following the end of a war. A post-war period ...

'' that Wallace's "distaste for American involvement with Britain and Europe was widely shared across the political spectrum".

Though Wallace was dissatisfied with Truman's increasingly confrontational policies toward the Soviet Union, he remained an integral part of Truman's Cabinet during the first half of 1946. He broke with administration policies in September 1946 when he delivered a speech in which he stated that "we should recognize that we have no more business in the political affairs of Eastern Europe than Russia has in the political affairs of Latin America, Western Europe and the United States". Wallace's speech was booed by the pro-Soviet crowd he delivered it to and even more strongly criticized by Truman administration officials and leading Republicans like Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate Majority Leade ...

and Arthur Vandenberg

Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg Sr. (March 22, 1884April 18, 1951) was an American politician who served as a United States senator from Michigan from 1928 to 1951. A member of the Republican Party, he participated in the creation of the United Natio ...

. Truman stated that Wallace's speech did not represent administration policy but merely Wallace's personal views, and on September 20 he demanded and received Wallace's resignation.

1948 presidential election

Shortly after leaving office, Wallace became the editor of ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

'', a progressive magazine. He also helped establish the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA), a progressive political organization that called for good relations with the Soviet Union and more liberal programs at home. Though not a member of the PCA, Wallace was widely regarded as the organization's leader and was criticized for the PCA's acceptance of Communist members. In response to the creation of the PCA, anti-Communist liberals established a rival group, Americans for Democratic Action

Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) is a liberal American political organization advocating progressive policies. ADA views itself as supporting social and economic justice through lobbying, grassroots organizing, research, and supporting pro ...

(ADA), which explicitly rejected any association with Communism. Wallace strongly criticized the president in early 1947 after Truman promulgated the Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledged American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion during the Cold War. It wa ...

to oppose Communist threats to Greece and Turkey. Wallace also opposed Truman's Executive Order 9835

President Harry S. Truman signed United States Executive Order 9835, sometimes known as the "Loyalty Order", on March 21, 1947. The order established the first general loyalty program in the United States, designed to root out communist influence ...

, which began a purge of government workers affiliated Communist groups deemed to be subversive. He initially favored the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

, but later opposed it because he believed the program should have been administered through the United Nations. Wallace and the PCA were scrutinized by the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

and the House Un-American Activities Committee, both of which sought to uncover evidence of Communist influence.

Many in the PCA favored the establishment of a third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a V ...

, but other longtime Wallace allies warned him against leaving the Democratic Party. On December 29, 1947, Wallace launched a third party campaign, declaring, "we have assembled a Gideon's Army, small in number, powerful in conviction ... We face the future unfettered, unfettered by any principal but the general welfare". He was backed by many Hollywood and Broadway celebrities, and intellectuals. Among his prominent supporters were Rexford Tugwell

Rexford Guy Tugwell (July 10, 1891 – July 21, 1979) was an American economist who became part of Franklin D. Roosevelt's first "Brain Trust", a group of Columbia University academics who helped develop policy recommendations leading up to R ...

, Congressmen Vito Marcantonio

Vito is an Italian name that is derived from the Latin word "''vita''", meaning "life".

It is a modern form of the Latin name Vitus, meaning "life-giver," as in San Vito or Saint Vitus, the patron saint of dogs and a heroic figure in southern I ...

and Leo Isacson

Leo Leous Isacson (April 20, 1910 – September 21, 1996) was a New York attorney and politician. He was notable for winning a 1948 election to the United States House of Representatives from New York's twenty-fourth district (Bronx) as the cand ...

, musicians Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplish ...

and Pete Seeger

Peter Seeger (May 3, 1919 – January 27, 2014) was an American folk singer and social activist. A fixture on nationwide radio in the 1940s, Seeger also had a string of hit records during the early 1950s as a member of the Weavers, notably ...

, and future presidential nominee George McGovern. Calvin Baldwin became Wallace's campaign manager and took charge of fundraising and ensuring that Wallace appeared on as many state ballots as possible. Wallace's first choice for running mate, Claude Pepper, refused to leave the Democratic Party, but Democratic Senator Glen H. Taylor

Glen Hearst Taylor (April 12, 1904 – April 28, 1984) was an American politician, entertainer, businessman, and U.S. senator from Idaho.

He was the vice presidential candidate on the Progressive Party ticket in the 1948 election. Taylor was ...

of Idaho agreed to serve as Wallace's running mate. Wallace accepted the endorsement of the American Communist Party

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

, stating, "I'm not following their line. If they want to follow my line, I say God bless 'em". Truman responded to Wallace's left-wing challenge by pressing for liberal domestic policies, while pro-ADA liberals like Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

, Robert F. Wagner, and James Roosevelt

James Roosevelt II (December 23, 1907 – August 13, 1991) was an American businessman, Marine, activist, and Democratic Party politician. The eldest son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt, he served as an official Secr ...

linked Wallace to the Soviet Union and the Communist Party. Many Americans came to see Wallace as a fellow traveler to Communists, a view that was reinforced by Wallace's refusal to condemn the 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état. In early 1948, the CIO and the AFL both rejected Wallace, with the AFL denouncing him as a "front, spokesman, and apologist for the Communist Party". With Wallace's foreign policy views overshadowing his domestic policy views, many liberals who had previously favored his candidacy returned to the Democratic fold.

Wallace embarked on a nationwide speaking tour to support his candidacy, encountering resistance in both the North and South. He openly defied the Jim Crow regime in the South, refusing to speak before segregated audiences. ''Time'' magazine, which opposed Wallace's candidacy, described him as "ostentatiously" riding through the towns and cities of the segregated South "with his Negro secretary beside him". A barrage of eggs and tomatoes were hurled at Wallace and struck him and his campaign members during the tour. State authorities in Virginia sidestepped enforcing their own segregation laws by declaring Wallace's campaign gatherings private parties. ''The Pittsburgh Press

''The Pittsburgh Press'' (formerly ''The Pittsburg Press'' and originally ''The Evening Penny Press'') was a major afternoon daily newspaper published in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from 1884 to 1992. At one time, the ''Press'' was the second larg ...

'' began publishing the names of known Wallace supporters. Scores of Wallace supporters in colleges and high schools lost their positions.

With strong financial support from Anita McCormick Blaine Anita Eugenie McCormick Blaine (1866-1954) was an American philanthropist and political activist. An heir to the McCormick Reaping Machine Works fortune built by her father, Cyrus McCormick (1809–1884), Blaine funded the launch of Chicago's Franci ...

, Wallace exceeded fundraising goals, and appeared on the ballot of every state except for Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Illinois. The campaign distributed 25 million copies of 140 fliers and pamphlets. Nevertheless, Gallup polls showed support for Wallace falling from 7% in December 1947 to 5% in June 1948. He was endorsed by only two newspapers: the Communist ''Daily Worker'' in New York and ''The Gazette and Daily'' in York, Pennsylvania. Some in the press began to speculate that Wallace would drop out of the race.

Wallace's supporters held a national convention in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

in July, formally establishing a new Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

. The party platform addressed a wide array of issues, and included support for the desegregation of public schools, gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing d ...

, a national health insurance program, free trade, and public ownership of large banks, railroads, and power utilities. Another part of the platform stated, "responsibility for ending the tragic prospect of war is a joint responsibility of the Soviet Union and the United States". During the convention, Wallace faced questioning regarding letters he had written to guru Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich (; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), also known as Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (russian: link=no, Никола́й Константи́нович Ре́рих), was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophi ...

; his refusal to comment on the letters was widely criticized. Wallace was further damaged days after the convention when Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938) ...

and Elizabeth Bentley testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee that several government officials associated with Wallace (including Alger Hiss and John Abt

John Jacob Abt (May 1, 1904 – August 10, 1991) was an American lawyer and politician, who spent most of his career as chief counsel to the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and was a member of the Communist Party and the Soviet spy network "Ware Gro ...

) were Communist infiltrators. Meanwhile, many Southern Democrats, outraged by the Democratic Party's pro-civil rights plank, bolted the party and nominated Strom Thurmond for president. With the Democrats badly divided, Republicans were confident that Republican nominee Thomas Dewey would win the election. Wallace himself predicted that Truman would be "the worst defeated candidate in history".

Though polls consistently showed him losing the race, Truman ran an effective campaign against Dewey and the conservative 80th United States Congress

The 80th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from January 3, 1947, ...

. He ultimately defeated Dewey in both the popular and electoral vote. Wallace won just 2.38 percent of the nationwide popular vote, and failed to carry any state. His best performance was in New York, where he won eight percent of the vote. Just one of the party's congressional candidates, incumbent Congressman Vito Marcantonio, won election.Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 500–502 Though Wallace and Thurmond probably took many voters from Truman, their presence in the race may have boosted the president's overall appeal by casting him as the candidate of the center-left. In response to the election results, Wallace stated, "Unless this bi-partisan foreign policy of high prices and war is promptly reversed, I predict that the Progressive Party will rapidly grow into the dominant party. ... To save the peace of the world the Progressive Party is more needed than ever before".

Historians Edward Schapsmeier and Frederick Schapsmeier argue:The Progressive party stood for one thing and Wallace another. Actually the party organization was controlled from the outset by those representing the radical left and not liberalism per se. This made it extremely easy for Communists and fellow travelers to infiltrate into important positions within the party machinery. Once this happened, party stands began to resemble a party line. Campaign literature, speech materials, and campaign slogans sounded strangely like echoes of what Moscow wanted to hear. As if wearing moral blinkers, Wallace increasingly became an imperceptive ideologue. Words were uttered by Wallace that did not sound like him, and his performance took on a strange Jekyll and Hyde quality—one moment he was a peace protagonist and the next a propaganda parrot for the Kremlin.

Later politics

Wallace initially remained active in politics following the 1948 campaign, and he delivered the keynote address at the 1950 Progressive National Convention. In early 1949, Wallace testified before Congress in the hope of preventing the ratification of theNorth Atlantic Treaty

The North Atlantic Treaty, also referred to as the Washington Treaty, is the treaty that forms the legal basis of, and is implemented by, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The treaty was signed in Washington, D.C., on 4 April 194 ...

, which established the NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

alliance between the United States, Canada, and several European countries. He became increasingly critical of the Soviet Union after 1948, and he resigned from the Progressive Party in August 1950 due to his support for the UN intervention in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

. After leaving the Progressive Party, Wallace endured what biographers John Culver and John Hyde describe as a "long, slow decline into obscurity marked by a certain acceptance of his outcast status".

In the early 1950s, he spent much of his time rebutting attacks by prominent public figures like General Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project, a top secret research project ...

, who claimed to have stopped providing Wallace with information regarding the Manhattan Project because he considered Wallace to be a security risk. In 1951, Wallace appeared before Congress to deny accusations that in 1944 he had encouraged a coalition between Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Communists. In 1952, he published an article, "Where I Was Wrong," in which he repudiated his earlier foreign policy positions and declared the Soviet Union to be "utterly evil".

Wallace did not endorse a candidate in the 1952 presidential election, but in the 1956 presidential election he endorsed incumbent Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

over Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson. Wallace, who maintained a correspondence with Eisenhower, described Eisenhower as "utterly sincere" in his efforts for peace. Wallace also began a correspondence with Vice President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, but he declined to endorse either Nixon or Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

in the 1960 presidential election. Though Wallace criticized Kennedy's farm policy during the 1960 campaign, Kennedy invited Wallace to his 1961 inauguration, the first presidential inauguration Wallace had attended since 1945. Wallace later wrote Kennedy, "at no time in our history have so many tens of millions of people been so completely enthusiastic about an inaugural address as about yours". In 1962, he delivered a speech commemorating the centennial anniversary of the establishment of the Department of Agriculture. He also began a correspondence with President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

regarding methods to alleviate rural poverty, though privately he criticized Johnson's escalation of American involvement in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

. In the 1964 election, Wallace returned to the Democratic fold, supporting Johnson over Republican nominee Barry Goldwater. Due to declining health, he made his last public appearance that year; in one of his last speeches, he stated, "We lost Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

in 1959 not only because of Castro but also because we failed to understand the needs of the farmer in the back country of Cuba from 1920 onward. ... The common man is on the march, but it is up to the uncommon men of education and insight to lead that march constructively".Business success

Wallace continued to co-own and take an interest in the company he had established,Pioneer Hi-Bred

Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc. is a U.S.-based producer of seeds for agriculture. They are a major producer of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), including genetically modified crops with insect and herbicide resistance.

As of 2019, Pi ...

(formerly the Hi-Bred Corn Company), and he established an experimental farm at his New York estate. He focused much of his efforts on the study of chickens, and Pioneer Hi-Bred's chickens at one point produced three-quarters of all commercially sold eggs worldwide. He also wrote or co-wrote several works on agriculture, including a book on the history of corn.

Illness and death

Wallace was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 1964. He consulted numerous specialists and tried various methods of treating the disease, stating, "I look on myself as an ALS guinea-pig, willing to try almost anything". He died in Danbury, Connecticut, on November 18, 1965, at the age of 77.Southwick (1998), p. 620. His remains were cremated and the ashes interred in Glendale Cemetery inDes Moines, Iowa