Heinrich Heine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was a German poet, writer and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early

Heine was born on 13 December 1797, in

Heine was born on 13 December 1797, in

Heine arrived in Berlin in March 1821. It was the biggest, most cosmopolitan city he had ever visited (its population was about 200,000). The university gave Heine access to notable cultural figures as lecturers: the Sanskritist Franz Bopp and the Homer critic F. A. Wolf, who inspired Heine's lifelong love of

Heine arrived in Berlin in March 1821. It was the biggest, most cosmopolitan city he had ever visited (its population was about 200,000). The university gave Heine access to notable cultural figures as lecturers: the Sanskritist Franz Bopp and the Homer critic F. A. Wolf, who inspired Heine's lifelong love of

In Hamburg one evening in January 1826 Heine met , who would be his chief publisher for the rest of his life. Their stormy relationship has been compared to a marriage. Campe was a liberal who published as many dissident authors as he could. He had developed various techniques for evading the authorities. The laws of the time stated that any book under 320 pages had to be submitted to censorship (the authorities thought long books would cause little trouble as they were unpopular). One way around censorship was to publish dissident works in large print to increase the number of pages beyond 320.

The censorship in Hamburg was relatively lax but Campe had to worry about Prussia, the largest German state and largest market for books (it was estimated that one-third of the German readership was Prussian). Initially, any book which had passed the censor in a German state was able to be sold in any of the other states, but in 1834 this loophole was closed. Campe was reluctant to publish uncensored books as he had bad experiences with print runs being confiscated. Heine resisted all censorship; this issue became a bone of contention between the two.

However, the relationship between author and publisher started well: Campe published the first volume of ''Reisebilder'' ("Travel Pictures") in May 1826. This volume included '' Die Harzreise'', which marked a new style of German travel-writing, mixing Romantic descriptions of nature with satire. Heine's ' followed in 1827. This was a collection of already published poems. No one expected it to become one of the most popular books of German verse ever published, and sales were slow to start with, picking up when composers began setting Heine's poems as Lieder. For example, the poem "Allnächtlich im Traume" was set to music by

In Hamburg one evening in January 1826 Heine met , who would be his chief publisher for the rest of his life. Their stormy relationship has been compared to a marriage. Campe was a liberal who published as many dissident authors as he could. He had developed various techniques for evading the authorities. The laws of the time stated that any book under 320 pages had to be submitted to censorship (the authorities thought long books would cause little trouble as they were unpopular). One way around censorship was to publish dissident works in large print to increase the number of pages beyond 320.

The censorship in Hamburg was relatively lax but Campe had to worry about Prussia, the largest German state and largest market for books (it was estimated that one-third of the German readership was Prussian). Initially, any book which had passed the censor in a German state was able to be sold in any of the other states, but in 1834 this loophole was closed. Campe was reluctant to publish uncensored books as he had bad experiences with print runs being confiscated. Heine resisted all censorship; this issue became a bone of contention between the two.

However, the relationship between author and publisher started well: Campe published the first volume of ''Reisebilder'' ("Travel Pictures") in May 1826. This volume included '' Die Harzreise'', which marked a new style of German travel-writing, mixing Romantic descriptions of nature with satire. Heine's ' followed in 1827. This was a collection of already published poems. No one expected it to become one of the most popular books of German verse ever published, and sales were slow to start with, picking up when composers began setting Heine's poems as Lieder. For example, the poem "Allnächtlich im Traume" was set to music by

Allnächtlich im Traume seh ich dich,

Und sehe dich freundlich grüßen,

Und laut aufweinend stürz ich mich

Zu deinen süßen Füßen.

Du siehst mich an wehmütiglich,

Und schüttelst das blonde Köpfchen;

Aus deinen Augen schleichen sich

Die Perlentränentröpfchen.

Du sagst mir heimlich ein leises Wort,

Und gibst mir den Strauß von Zypressen.

Ich wache auf, und der Strauß ist fort,

Und das Wort hab ich vergessen.

Nightly I see you in dreams – you speak,

With kindliness sincerest,

I throw myself, weeping aloud and weak

At your sweet feet, my dearest.

You look at me with wistful woe,

And shake your golden curls;

And stealing from your eyes there flow

The teardrops like to pearls.

You breathe in my ear a secret word,

A garland of cypress for token.

I wake; it is gone; the dream is blurred,

And forgotten the word that was spoken.

(Poetic translation by Hal Draper)

Starting from the mid-1820s, Heine distanced himself from

Das Fräulein stand am Meere

Und seufzte lang und bang.

Es rührte sie so sehre

der Sonnenuntergang.

Mein Fräulein! Sein sie munter,

Das ist ein altes Stück;

Hier vorne geht sie unter

Und kehrt von hinten zurück.

A mistress stood by the sea

sighing long and anxiously.

She was so deeply stirred

By the setting sun

My Fräulein!, be gay,

This is an old play;

ahead of you it sets

And from behind it returns.

The blue flower of Am Kreuzweg wird begraben

Wer selber brachte sich um;

dort wächst eine blaue Blume,

Die Armesünderblum.

Am Kreuzweg stand ich und seufzte;

Die Nacht war kalt und stumm.

Im Mondenschein bewegte sich langsam

Die Armesünderblum.

At the cross-road will be buried

He who killed himself;

There grows a blue flower,

Suicide’s flower.

I stood at the cross-road and sighed

The night was cold and mute.

By the light of the moon moved slowly

Suicide’s flower.

Heine became increasingly critical of

The first volume of travel writings was such a success that Campe pressed Heine for another. ''Reisebilder II'' appeared in April 1827. It contains the second cycle of North Sea poems, a prose essay on the North Sea as well as a new work, ''Ideen: Das Buch Le Grand'', which contains the following satire on German censorship:

The first volume of travel writings was such a success that Campe pressed Heine for another. ''Reisebilder II'' appeared in April 1827. It contains the second cycle of North Sea poems, a prose essay on the North Sea as well as a new work, ''Ideen: Das Buch Le Grand'', which contains the following satire on German censorship:

The German Censors —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— idiots —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— ——

Heine went to England to avoid what he predicted would be controversy over the publication of this work. In London he cashed a cheque from his uncle for £200 (equal to £ today), much to Salomon's chagrin. Heine was unimpressed by the English: he found them commercial and prosaic, and still blamed them for the defeat of Napoleon.

On his return to Germany, Cotta, the liberal publisher of Goethe and Schiller, offered Heine a job co-editing a magazine, ''Politische Annalen'', in Munich. Heine did not find work on the newspaper congenial, and instead tried to obtain a professorship at Munich University, with no success. After a few months he took a trip to northern Italy, visiting Lucca, Florence and Venice, but was forced to return when he received news that his father had died. This Italian journey resulted in a series of new works: ''Die Reise von München nach Genua'' (''Journey from Munich to Genoa''), ''Die Bäder von Lucca'' (''The Baths of Lucca'') and ''Die Stadt Lucca'' (''The Town of Lucca'').

''Die Bäder von Lucca'' embroiled Heine in controversy. The aristocratic poet August von Platen had been annoyed by some epigrams by Immermann which Heine had included in the second volume of ''Reisebilder''. He counter-attacked by writing a play, ''Der romantische Ödipus'', which included anti-Semitic jibes about Heine. Heine was stung and responded by mocking Platen's homosexuality in ''Die Bäder von Lucca''. This back-and-forth ad hominem literary polemic has become known as the .

In Paris, Heine earned money working as the French correspondent for one of Cotta's newspapers, the ''

In Paris, Heine earned money working as the French correspondent for one of Cotta's newspapers, the '' Heine had had few serious love affairs, but in late 1834 he made the acquaintance of a 19-year-old Paris shopgirl, Crescence Eugénie Mirat, whom he nicknamed "Mathilde". Heine reluctantly began a relationship with her. She was illiterate, knew no German, and had no interest in cultural or intellectual matters. Nevertheless, she moved in with Heine in 1836 and lived with him for the rest of his life (they were married in 1841).

Heine had had few serious love affairs, but in late 1834 he made the acquaintance of a 19-year-old Paris shopgirl, Crescence Eugénie Mirat, whom he nicknamed "Mathilde". Heine reluctantly began a relationship with her. She was illiterate, knew no German, and had no interest in cultural or intellectual matters. Nevertheless, she moved in with Heine in 1836 and lived with him for the rest of his life (they were married in 1841).

Heine's relationship with his fellow dissident Ludwig Börne was troubled. Since Börne did not attack religion or traditional morality like Heine, the German authorities hounded him less although they still banned his books as soon as they appeared.

Börne was the idol of German immigrant workers in Paris. He was also a republican, while Heine was not. Heine regarded Börne, with his admiration for

Heine's relationship with his fellow dissident Ludwig Börne was troubled. Since Börne did not attack religion or traditional morality like Heine, the German authorities hounded him less although they still banned his books as soon as they appeared.

Börne was the idol of German immigrant workers in Paris. He was also a republican, while Heine was not. Heine regarded Börne, with his admiration for  Heine continued to write reports for Cotta's ''Allgemeine Zeitung'' (and, when Cotta died, for his son and successor). One event which really galvanised him was the 1840 Damascus Affair in which Jews in Damascus had been subject to

Heine continued to write reports for Cotta's ''Allgemeine Zeitung'' (and, when Cotta died, for his son and successor). One event which really galvanised him was the 1840 Damascus Affair in which Jews in Damascus had been subject to

In October 1843, Heine's distant relative and German revolutionary,

In October 1843, Heine's distant relative and German revolutionary,

In May 1848, Heine, who had not been well, suddenly fell paralyzed and had to be confined to bed. He would not leave what he called his "mattress-grave" (''Matratzengruft'') until his death eight years later. He also experienced difficulties with his eyes. It had been suggested that he suffered from multiple sclerosis or

In May 1848, Heine, who had not been well, suddenly fell paralyzed and had to be confined to bed. He would not leave what he called his "mattress-grave" (''Matratzengruft'') until his death eight years later. He also experienced difficulties with his eyes. It had been suggested that he suffered from multiple sclerosis or

Wo wird einst des Wandermüden

Letzte Ruhestätte sein?

Unter Palmen in dem Süden?

Unter Linden an dem Rhein?

Werd ich wo in einer Wüste

Eingescharrt von fremder Hand?

Oder ruh ich an der Küste

Eines Meeres in dem Sand?

Immerhin! Mich wird umgeben

Gotteshimmel, dort wie hier,

Und als Totenlampen schweben

Nachts die Sterne über mir.

Where shall I, the wander-wearied,

Find my haven and my shrine?

Under palms will I be buried?

Under lindens on the Rhine?

Shall I lie in desert reaches,

Buried by a stranger's hand?

Or upon the well-loved beaches,

Covered by the friendly sand?

Well, what matter! God has given

Wider spaces there than here.

And the stars that swing in heaven

Shall be lamps above my bier.

(translation in verse by L.U.)

His wife Mathilde survived him, dying in 1883. The couple had no children.

In the 1890s, amidst a flowering of affection for Heine leading up to the centennial of his birth, plans were made to honor Heine with a memorial; these were strongly supported by one of Heine's greatest admirers, Elisabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria. The empress commissioned a statue from the sculptor

In the 1890s, amidst a flowering of affection for Heine leading up to the centennial of his birth, plans were made to honor Heine with a memorial; these were strongly supported by one of Heine's greatest admirers, Elisabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria. The empress commissioned a statue from the sculptor

File:HeineMonument.jpg, Heine monument in Düsseldorf

File:Heine-Denkmal Frankfurt.JPG, Heine monument in Frankfurt, the only pre-1945 one in Germany

File:Heinrich Heine Brocken 2017.jpg, Monument on Mount

**''Almansor'' (play, written 1821–1822)

**''William Ratcliff'' (play, written January 1822)

**''Lyrisches Intermezzo'' (cycle of poems)

* 1826 (May): ''Reisebilder. Erster Teil'' ("Travel Pictures I"), contains:

**'' Die Harzreise'' ("The Harz Journey", prose travel work)

**''Die Heimkehr'' ("The Homecoming", poems)

**''Die Nordsee. Erste Abteilung'' ("North Sea I", cycle of poems)

* 1827 (April): ''Reisebilder. Zweiter Teil'' ("Travel Pictures II"), contains:

** ''Die Nordsee. Zweite Abteilung'' ("The North Sea II", cycle of poems)

** ''Die Nordsee. Dritte Abteilung'' ("The North Sea III", prose essay)

** ''Ideen: das Buch le Grand'' ("Ideas: The Book of Le Grand")

** ''Briefe aus Berlin'' ("Letters from Berlin", a much shortened and revised version of the 1822 work)

* 1827 (October): ' ("Book of Songs"); collection of poems containing the following sections:

**''Junge Leiden'' ("Youthful Sorrows")

**''Die Heimkehr'' ("The Homecoming", originally published 1826)

**''Lyrisches Intermezzo'' ("Lyrical Intermezzo", originally published 1823)

**"Aus der ''Harzreise''" (poems from ''Die Harzreise'', originally published 1826)

**''Die Nordsee'' ("The North Sea: Cycles I and II", originally published 1826/1827)

* 1829 (December): ''Reisebilder. Dritter Teil'' ("Travel Pictures III"), contains:

**''Die Reise von München nach Genua'' ("Journey from Munich to Genoa", prose travel work)

**''Die Bäder von Lucca'' ("The Baths of Lucca", prose travel work)

**''Anno 1829''

* 1831 (January): ''Nachträge zu den Reisebildern'' ("Supplements to the Travel Pictures"), the second edition of 1833 was retitled as ''Reisebilder. Vierter Teil'' ("Travel Pictures IV"), contains:

**''Die Stadt Lucca'' ("The Town of Lucca", prose travel work)

**''Englische Fragmente'' ("English Fragments", travel writings)

* 1831 (April): ''Zu "Kahldorf über den Adel"'' (introduction to the book "Kahldorf on the Nobility", uncensored version not published until 1890)

* 1833: ''Französische Zustände'' ("Conditions in France", collected journalism)

* 1833 (December): ''Der Salon. Erster Teil'' ("The Salon I"), contains:

** ''Französische Maler'' ("French Painters", criticism)

** ''Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski'' ("From the Memoirs of Herr Schnabelewopski", unfinished novel)

* 1835 (January): ''Der Salon. Zweiter Teil'' ("The Salon II"), contains:

** '' Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland'' ("On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany")

** ''Neuer Frühling'' ("New Spring", cycle of poems)

* 1835 (November): ''Die romantische Schule'' ("The Romantic School", criticism)

* 1837 (July): ''Der Salon. Dritter Teil'' ("The Salon III"), contains:

** ''Florentinische Nächte'' ("Florentine Nights", unfinished novel)

** ''Elementargeister'' ("Elemental Spirits", essay on folklore)

* 1837 (July): ''Über den Denunzianten. Eine Vorrede zum dritten Teil des Salons.'' ("On the Denouncer. A Preface to Salon III", pamphlet)

* 1837 (November): ''Einleitung zum "Don Quixote"'' ("Introduction to ''Don Quixote''", preface to a new German translation of '' Don Quixote'')

* 1838 (November): ''Der Schwabenspiegel'' ("The Mirror of Swabia", prose work attacking poets of the Swabian School)

* 1838 (October): ''Shakespeares Mädchen und Frauen'' ("Shakespeare's Girls and Women", essays on the female characters in Shakespeare's tragedies and histories)

*1839: ''Anno 1839''

* 1840 (August): ''Ludwig Börne. Eine Denkschrift'' ("Ludwig Börne: A Memorial", long prose work about the writer Ludwig Börne)

* 1840 (November): ''Der Salon. Vierter Teil'' ("The Salon IV"), contains:

** ''Der Rabbi von Bacherach'' ("The Rabbi of Bacharach", unfinished historical novel)

** ''Über die französische Bühne'' ("On the French Stage", prose criticism)

* 1844 (September): ''Neue Gedichte'' ("New Poems"); contains the following sections:

**''Neuer Frühling'' ("New Spring", originally published in 1834)

**''Verschiedene'' ("Sundry Women")

**''Romanzen'' ("Ballads")

**''Zur Ollea'' ("Olio")

**''Zeitgedichte'' ("Poems for the Times")

** it also includes ''Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen'' ('' Germany. A Winter's Tale'', long poem)

*1847 (January): ''Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum'' (''Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night's Dream'', long poem, written 1841–46)

* 1851 (September): ''Romanzero''; collection of poems divided into three books:

**''Erstes Buch: Historien'' ("First Book: Histories")

**''Zweites Buch: Lamentationen'' ("Second Book: Lamentations")

**''Drittes Buch: Hebräische Melodien'' ("Third Book: Hebrew Melodies")

* 1851 (October): ''Der Doktor Faust. Tanzpoem'' ("Doctor Faust. Dance Poem", ballet libretto, written 1846)

* 1854 (October): ''Vermischte Schriften'' ("Miscellaneous Writings") in three volumes, contains:

**Volume One:

***''Geständnisse'' ("Confessions", autobiographical work)

***''Die Götter im Exil'' ("The Gods in Exile", prose essay)

***''Die Göttin Diana'' ("The Goddess Diana", ballet scenario, written 1846)

***''Ludwig Marcus: Denkworte'' ("Ludwig Marcus: Recollections", prose essay)

***''Gedichte. 1853 und 1854'' ("Poems. 1854 and 1854")

**Volume Two:

***''Lutezia. Erster Teil'' ("Lutetia I", collected journalism about France)

**Volume Three:

***''Lutezia. Zweiter Teil'' ("Lutetia II", collected journalism about France)

**''Almansor'' (play, written 1821–1822)

**''William Ratcliff'' (play, written January 1822)

**''Lyrisches Intermezzo'' (cycle of poems)

* 1826 (May): ''Reisebilder. Erster Teil'' ("Travel Pictures I"), contains:

**'' Die Harzreise'' ("The Harz Journey", prose travel work)

**''Die Heimkehr'' ("The Homecoming", poems)

**''Die Nordsee. Erste Abteilung'' ("North Sea I", cycle of poems)

* 1827 (April): ''Reisebilder. Zweiter Teil'' ("Travel Pictures II"), contains:

** ''Die Nordsee. Zweite Abteilung'' ("The North Sea II", cycle of poems)

** ''Die Nordsee. Dritte Abteilung'' ("The North Sea III", prose essay)

** ''Ideen: das Buch le Grand'' ("Ideas: The Book of Le Grand")

** ''Briefe aus Berlin'' ("Letters from Berlin", a much shortened and revised version of the 1822 work)

* 1827 (October): ' ("Book of Songs"); collection of poems containing the following sections:

**''Junge Leiden'' ("Youthful Sorrows")

**''Die Heimkehr'' ("The Homecoming", originally published 1826)

**''Lyrisches Intermezzo'' ("Lyrical Intermezzo", originally published 1823)

**"Aus der ''Harzreise''" (poems from ''Die Harzreise'', originally published 1826)

**''Die Nordsee'' ("The North Sea: Cycles I and II", originally published 1826/1827)

* 1829 (December): ''Reisebilder. Dritter Teil'' ("Travel Pictures III"), contains:

**''Die Reise von München nach Genua'' ("Journey from Munich to Genoa", prose travel work)

**''Die Bäder von Lucca'' ("The Baths of Lucca", prose travel work)

**''Anno 1829''

* 1831 (January): ''Nachträge zu den Reisebildern'' ("Supplements to the Travel Pictures"), the second edition of 1833 was retitled as ''Reisebilder. Vierter Teil'' ("Travel Pictures IV"), contains:

**''Die Stadt Lucca'' ("The Town of Lucca", prose travel work)

**''Englische Fragmente'' ("English Fragments", travel writings)

* 1831 (April): ''Zu "Kahldorf über den Adel"'' (introduction to the book "Kahldorf on the Nobility", uncensored version not published until 1890)

* 1833: ''Französische Zustände'' ("Conditions in France", collected journalism)

* 1833 (December): ''Der Salon. Erster Teil'' ("The Salon I"), contains:

** ''Französische Maler'' ("French Painters", criticism)

** ''Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski'' ("From the Memoirs of Herr Schnabelewopski", unfinished novel)

* 1835 (January): ''Der Salon. Zweiter Teil'' ("The Salon II"), contains:

** '' Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland'' ("On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany")

** ''Neuer Frühling'' ("New Spring", cycle of poems)

* 1835 (November): ''Die romantische Schule'' ("The Romantic School", criticism)

* 1837 (July): ''Der Salon. Dritter Teil'' ("The Salon III"), contains:

** ''Florentinische Nächte'' ("Florentine Nights", unfinished novel)

** ''Elementargeister'' ("Elemental Spirits", essay on folklore)

* 1837 (July): ''Über den Denunzianten. Eine Vorrede zum dritten Teil des Salons.'' ("On the Denouncer. A Preface to Salon III", pamphlet)

* 1837 (November): ''Einleitung zum "Don Quixote"'' ("Introduction to ''Don Quixote''", preface to a new German translation of '' Don Quixote'')

* 1838 (November): ''Der Schwabenspiegel'' ("The Mirror of Swabia", prose work attacking poets of the Swabian School)

* 1838 (October): ''Shakespeares Mädchen und Frauen'' ("Shakespeare's Girls and Women", essays on the female characters in Shakespeare's tragedies and histories)

*1839: ''Anno 1839''

* 1840 (August): ''Ludwig Börne. Eine Denkschrift'' ("Ludwig Börne: A Memorial", long prose work about the writer Ludwig Börne)

* 1840 (November): ''Der Salon. Vierter Teil'' ("The Salon IV"), contains:

** ''Der Rabbi von Bacherach'' ("The Rabbi of Bacharach", unfinished historical novel)

** ''Über die französische Bühne'' ("On the French Stage", prose criticism)

* 1844 (September): ''Neue Gedichte'' ("New Poems"); contains the following sections:

**''Neuer Frühling'' ("New Spring", originally published in 1834)

**''Verschiedene'' ("Sundry Women")

**''Romanzen'' ("Ballads")

**''Zur Ollea'' ("Olio")

**''Zeitgedichte'' ("Poems for the Times")

** it also includes ''Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen'' ('' Germany. A Winter's Tale'', long poem)

*1847 (January): ''Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum'' (''Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night's Dream'', long poem, written 1841–46)

* 1851 (September): ''Romanzero''; collection of poems divided into three books:

**''Erstes Buch: Historien'' ("First Book: Histories")

**''Zweites Buch: Lamentationen'' ("Second Book: Lamentations")

**''Drittes Buch: Hebräische Melodien'' ("Third Book: Hebrew Melodies")

* 1851 (October): ''Der Doktor Faust. Tanzpoem'' ("Doctor Faust. Dance Poem", ballet libretto, written 1846)

* 1854 (October): ''Vermischte Schriften'' ("Miscellaneous Writings") in three volumes, contains:

**Volume One:

***''Geständnisse'' ("Confessions", autobiographical work)

***''Die Götter im Exil'' ("The Gods in Exile", prose essay)

***''Die Göttin Diana'' ("The Goddess Diana", ballet scenario, written 1846)

***''Ludwig Marcus: Denkworte'' ("Ludwig Marcus: Recollections", prose essay)

***''Gedichte. 1853 und 1854'' ("Poems. 1854 and 1854")

**Volume Two:

***''Lutezia. Erster Teil'' ("Lutetia I", collected journalism about France)

**Volume Three:

***''Lutezia. Zweiter Teil'' ("Lutetia II", collected journalism about France)

Available online

Parallel German/English text

of Heine's poem Geoffroy Rudel and Melisande of Tripoli

review of Heinrich Heine in 2006, 150 years after his death

Art of the States: The Resounding Lyre

– musical setting of Heine's poem "Halleluja" *

Loving Herodias

by David P. Goldman, ''First Things''

Heinrich Heine (German author)

Britannica Online Encyclopedia {{DEFAULTSORT:Heine, Heinrich 1797 births 1856 deaths Anti-natalists Writers from Düsseldorf 19th-century German Jews 19th-century German writers 19th-century German male writers Converts to Lutheranism from Judaism German emigrants to France German Lutherans German poets German socialists German travel writers German writers in French Jewish German writers Jewish poets Saint-Simonists University of Bonn alumni University of Göttingen alumni Burials at Montmartre Cemetery Epic poets Romantic poets Spinoza scholars

lyric poetry

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

, which was set to music in the form of '' Lieder'' (art songs) by composers such as Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

and Franz Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wo ...

. Heine's later verse and prose are distinguished by their satirical wit and irony. He is considered a member of the Young Germany movement. His radical political views led to many of his works being banned by German authorities—which, however, only added to his fame. He spent the last 25 years of his life as an expatriate

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country. In common usage, the term often refers to educated professionals, skilled workers, or artists taking positions outside their home country, either ...

in Paris.

Early life

Childhood and youth

Heine was born on 13 December 1797, in

Heine was born on 13 December 1797, in Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in ...

, in what was then the Duchy of Berg, into a Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

family. He was called "Harry" in childhood but became known as "Heinrich" after his conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

to Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

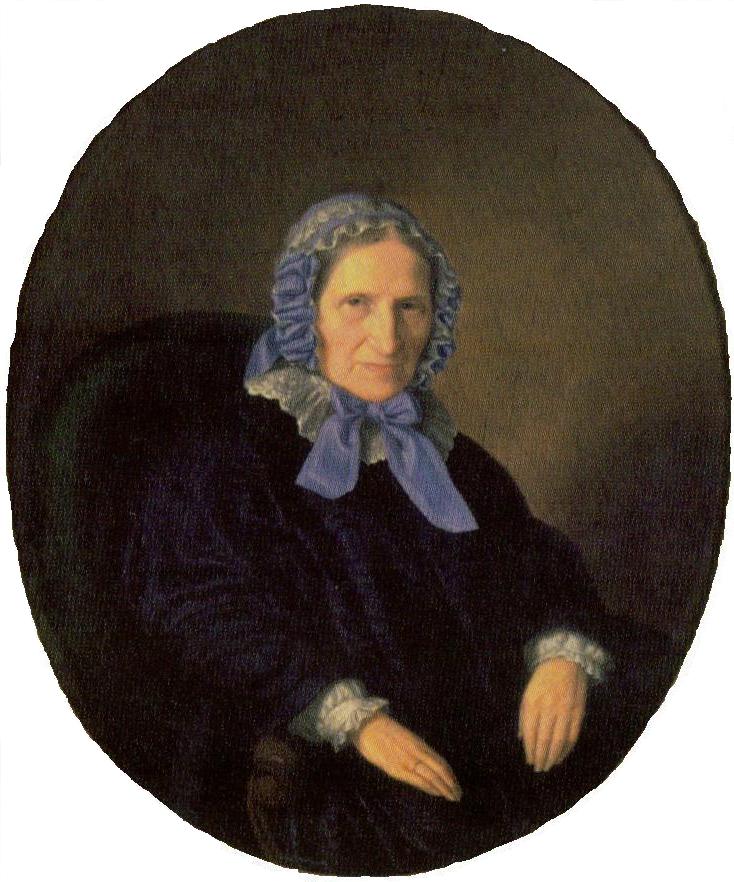

in 1825. Heine's father, Samson Heine (1764–1828), was a textile merchant. His mother Peira (known as "Betty"), ''née'' van Geldern (1771–1859), was the daughter of a physician.

Heinrich was the eldest of four children. He had a sister, Charlotte (later ), and two brothers, Gustav (later Baron Heine-Geldern and publisher of the Viennese newspaper '), and Maximilian, who became a physician in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. Heine was also a third cousin once removed of philosopher and economist Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, also born to a German Jewish family in the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

, with whom he became a frequent correspondent in later life.

Düsseldorf at the time was a town with a population of around 16,000. The French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

and subsequent Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars involving Germany complicated Düsseldorf's political history during Heine's childhood. It had been the capital of the Duchy of Jülich-Berg, but was under French occupation at the time of his birth. It then passed to the Elector of Bavaria before being ceded to Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

in 1806, who turned it into the capital of the Grand Duchy of Berg

The Grand Duchy of Berg (german: Großherzogtum Berg), also known as the Grand Duchy of Berg and Cleves, was a territorial grand duchy established in 1806 by Emperor Napoleon after his victory at the Battle of Austerlitz (1805) on territories b ...

, one of three French states he established in Germany. It was first ruled by Joachim Murat, then by Napoleon himself. Upon Napoleon's downfall in 1815 it became part of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

.

Thus Heine's formative years were spent under French influence. The adult Heine would always be devoted to the French for introducing the Napoleonic Code and trial by jury. He glossed over the negative aspects of French rule in Berg: heavy taxation, conscription, and economic depression brought about by the Continental Blockade

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berlin ...

(which may have contributed to his father's bankruptcy). Heine greatly admired Napoleon as the promoter of revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality and loathed the political atmosphere in Germany after Napoleon's defeat, marked by the conservative policies of Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

, who attempted to reverse the effects of the French Revolution.

Heine's parents were not particularly devout. They sent him as a young child to a Jewish school where he learned a smattering of Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, but thereafter he attended Catholic schools. Here he learned French, which became his second language – although he always spoke it with a German accent. He also acquired a lifelong love for Rhenish folklore.

In 1814 Heine went to a business school in Düsseldorf where he learned to read English, the commercial language of the time. The most successful member of the Heine family was his uncle Salomon Heine

Salomon Heine (19 October 1767 – 23 December 1844) was a merchant and banker in Hamburg. Heine was born in Hanover. Penniless, he came to Hamburg in 1784 and in the following years acquired sizeable assets. It was common knowledge at the ti ...

, a millionaire banker in Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

. In 1816 Heine moved to Hamburg to become an apprentice at Heckscher & Co, his uncle's bank, but displayed little aptitude for business. He learned to hate Hamburg, with its commercial ethos, but it would become one of the poles of his life alongside Paris.

When he was 18 Heine almost certainly had an unrequited love for his cousin Amalie, Salomon's daughter. Whether he then transferred his affections (equally unsuccessfully) to her sister Therese is unknown. This period in Heine's life is not clear but it seems that his father's business deteriorated, making Samson Heine effectively the ward of his brother Salomon.

Universities

Salomon realised that his nephew had no talent for trade, and it was decided that Heine should enter law. So, in 1819, Heine went to the University of Bonn (then in Prussia). Political life in Germany was divided between conservatives and liberals. The conservatives, who were in power, wanted to restore things to the way they were before theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

. They were against German unification because they felt a united Germany might fall victim to revolutionary ideas. Most German states were absolutist monarchies with a censored press. The opponents of the conservatives, the liberals, wanted to replace absolutism with representative, constitutional government, equality before the law and a free press.

At the University of Bonn, liberal students were at war with the conservative authorities. Heine was a radical liberal and one of the first things he did after his arrival was to take part in a parade which violated the Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees (german: Karlsbader Beschlüsse) were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town ...

, a series of measures introduced by Metternich to suppress liberal political activity.

Heine was more interested in studying history and literature than law. The university had engaged the famous literary critic and thinker August Wilhelm Schlegel as a lecturer and Heine heard him talk about the '' Nibelungenlied'' and Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. Though he would later mock Schlegel, Heine found in him a sympathetic critic for his early verses. Heine began to acquire a reputation as a poet at Bonn. He also wrote two tragedies, ''Almansor'' and ''William Ratcliff'', but they had little success in the theatre.

After a year at Bonn, Heine left to continue his law studies at the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded ...

. Heine hated the town. It was part of Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

, ruled by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the power Heine blamed for bringing Napoleon down.

Here the poet experienced an aristocratic snobbery absent elsewhere. He hated law as the Historical School of law he had to study was used to bolster the reactionary form of government he opposed. Other events conspired to make Heine loathe this period of his life: he was expelled from a student fraternity

Fraternities and sororities are social organizations at colleges and universities in North America.

Generally, membership in a fraternity or sorority is obtained as an undergraduate student, but continues thereafter for life. Some accept gradua ...

due to anti-Semitism reasons and he heard the news that his cousin Amalie had become engaged. When Heine challenged another student, Wiebel, to a duel (the first of ten known incidents throughout his life), the authorities stepped in and he was suspended from the university for six months. His uncle then decided to send him to the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

.

Heine arrived in Berlin in March 1821. It was the biggest, most cosmopolitan city he had ever visited (its population was about 200,000). The university gave Heine access to notable cultural figures as lecturers: the Sanskritist Franz Bopp and the Homer critic F. A. Wolf, who inspired Heine's lifelong love of

Heine arrived in Berlin in March 1821. It was the biggest, most cosmopolitan city he had ever visited (its population was about 200,000). The university gave Heine access to notable cultural figures as lecturers: the Sanskritist Franz Bopp and the Homer critic F. A. Wolf, who inspired Heine's lifelong love of Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his ...

. Most important was the philosopher Hegel, whose influence on Heine is hard to gauge. He probably gave Heine and other young students the idea that history had a meaning which could be seen as progressive. Heine also made valuable acquaintances in Berlin, notably the liberal Karl August Varnhagen and his Jewish wife Rahel, who held a leading salon.

Another friend was the satirist Karl Immermann, who had praised Heine's first verse collection, ''Gedichte'', when it appeared in December 1821. During his time in Berlin Heine also joined the ''Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft der Juden'', a society which attempted to achieve a balance between the Jewish faith and modernity. Since Heine was not very religious in outlook he soon lost interest, but he also began to investigate Jewish history. He was particularly drawn to the Spanish Jews of the Middle Ages. In 1824 Heine began a historical novel, ''Der Rabbi von Bacherach'', which he never managed to finish.

In May 1823 Heine left Berlin for good and joined his family at their new home in Lüneburg. Here he began to write the poems of the cycle ''Die Heimkehr'' ("The Homecoming"). He returned to Göttingen where he was again bored by the law. In September 1824 he decided to take a break and set off on a trip through the Harz

The Harz () is a highland area in northern Germany. It has the highest elevations for that region, and its rugged terrain extends across parts of Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. The name ''Harz'' derives from the Middle High German ...

mountains. On his return he started writing an account of it, '' Die Harzreise''.

On 28 June 1825 Heine converted to Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. The Prussian government had been gradually restoring discrimination against Jews. In 1822 it introduced a law excluding Jews from academic posts and Heine had ambitions for a university career. As Heine said in self-justification, his conversion was "the ticket of admission into European culture". In any event, Heine's conversion, which was reluctant, never brought him any benefits in his career.

Julius Campe and first literary successes

Heine now had to search for a job. He was only really suited to writing but it was extremely difficult to be a professional writer in Germany. The market for literary works was small and it was only possible to make a living by writing virtually non-stop. Heine was incapable of doing this so he never had enough money to cover his expenses. Before finding work, Heine visited the North Sea resort of Norderney which inspired the free verse poems of his cycle ''Die Nordsee''. In Hamburg one evening in January 1826 Heine met , who would be his chief publisher for the rest of his life. Their stormy relationship has been compared to a marriage. Campe was a liberal who published as many dissident authors as he could. He had developed various techniques for evading the authorities. The laws of the time stated that any book under 320 pages had to be submitted to censorship (the authorities thought long books would cause little trouble as they were unpopular). One way around censorship was to publish dissident works in large print to increase the number of pages beyond 320.

The censorship in Hamburg was relatively lax but Campe had to worry about Prussia, the largest German state and largest market for books (it was estimated that one-third of the German readership was Prussian). Initially, any book which had passed the censor in a German state was able to be sold in any of the other states, but in 1834 this loophole was closed. Campe was reluctant to publish uncensored books as he had bad experiences with print runs being confiscated. Heine resisted all censorship; this issue became a bone of contention between the two.

However, the relationship between author and publisher started well: Campe published the first volume of ''Reisebilder'' ("Travel Pictures") in May 1826. This volume included '' Die Harzreise'', which marked a new style of German travel-writing, mixing Romantic descriptions of nature with satire. Heine's ' followed in 1827. This was a collection of already published poems. No one expected it to become one of the most popular books of German verse ever published, and sales were slow to start with, picking up when composers began setting Heine's poems as Lieder. For example, the poem "Allnächtlich im Traume" was set to music by

In Hamburg one evening in January 1826 Heine met , who would be his chief publisher for the rest of his life. Their stormy relationship has been compared to a marriage. Campe was a liberal who published as many dissident authors as he could. He had developed various techniques for evading the authorities. The laws of the time stated that any book under 320 pages had to be submitted to censorship (the authorities thought long books would cause little trouble as they were unpopular). One way around censorship was to publish dissident works in large print to increase the number of pages beyond 320.

The censorship in Hamburg was relatively lax but Campe had to worry about Prussia, the largest German state and largest market for books (it was estimated that one-third of the German readership was Prussian). Initially, any book which had passed the censor in a German state was able to be sold in any of the other states, but in 1834 this loophole was closed. Campe was reluctant to publish uncensored books as he had bad experiences with print runs being confiscated. Heine resisted all censorship; this issue became a bone of contention between the two.

However, the relationship between author and publisher started well: Campe published the first volume of ''Reisebilder'' ("Travel Pictures") in May 1826. This volume included '' Die Harzreise'', which marked a new style of German travel-writing, mixing Romantic descriptions of nature with satire. Heine's ' followed in 1827. This was a collection of already published poems. No one expected it to become one of the most popular books of German verse ever published, and sales were slow to start with, picking up when composers began setting Heine's poems as Lieder. For example, the poem "Allnächtlich im Traume" was set to music by Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

and Felix Mendelssohn. It contains the ironic disillusionment typical of Heine:

Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

by adding irony, sarcasm, and satire into his poetry, and making fun of the sentimental-romantic awe of nature and of figures of speech in contemporary poetry and literature. An example are these lines:

Novalis

Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg (2 May 1772 – 25 March 1801), pen name Novalis (), was a German polymath who was a writer, philosopher, poet, aristocrat and mystic. He is regarded as an idiosyncratic and influential figure o ...

, "symbol for the Romantic movement", also received withering treatment from Heine during this period, as illustrated by the following quatrains from ''Lyrisches Intermezzo'':

despotism

Despotism ( el, Δεσποτισμός, ''despotismós'') is a form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute power. Normally, that entity is an individual, the despot; but (as in an autocracy) societies which limit respect an ...

and reactionary chauvinism in Germany, of nobility and clerics but also of the narrow-mindedness of ordinary people and of the rising German form of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, especially in contrast to the French and the revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

. Nevertheless, he made a point of stressing his love for his Fatherland:

Plant the black, red, gold banner at the summit of the German idea, make it the standard of free mankind, and I will shed my dear heart's blood for it. Rest assured, I love the Fatherland just as much as you do.

Travel and the Platen affair

The first volume of travel writings was such a success that Campe pressed Heine for another. ''Reisebilder II'' appeared in April 1827. It contains the second cycle of North Sea poems, a prose essay on the North Sea as well as a new work, ''Ideen: Das Buch Le Grand'', which contains the following satire on German censorship:

The first volume of travel writings was such a success that Campe pressed Heine for another. ''Reisebilder II'' appeared in April 1827. It contains the second cycle of North Sea poems, a prose essay on the North Sea as well as a new work, ''Ideen: Das Buch Le Grand'', which contains the following satire on German censorship:

Paris years

Foreign correspondent

Heine left Germany for France in 1831, settling in Paris for the remainder of his life. His move was prompted by theJuly Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first in 1789. It led to ...

of 1830 that had made Louis-Philippe the "Citizen King" of the French. Heine shared liberal enthusiasm for the revolution, which he felt had the potential to overturn the conservative political order in Europe. Heine was also attracted by the prospect of freedom from German censorship and was interested in the new French utopian

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia'', describing a fictional island socie ...

political doctrine of Saint-Simonianism. Saint-Simonianism preached a new social order in which meritocracy would replace hereditary distinctions in rank and wealth. There would also be female emancipation and an important role for artists and scientists. Heine frequented some Saint-Simonian meetings after his arrival in Paris but within a few years his enthusiasm for the ideology – and other forms of utopianism – had waned.

Heine soon became a celebrity in France. Paris offered him a cultural richness unavailable in the smaller cities of Germany. He made many famous acquaintances (the closest were Gérard de Nerval

Gérard de Nerval (; 22 May 1808 – 26 January 1855) was the pen name of the French writer, poet, and translator Gérard Labrunie, a major figure of French romanticism, best known for his novellas and poems, especially the collection '' Les ...

and Hector Berlioz) but he always remained something of an outsider. He had little interest in French literature and wrote everything in German, subsequently translating it into French with the help of a collaborator.

In Paris, Heine earned money working as the French correspondent for one of Cotta's newspapers, the ''

In Paris, Heine earned money working as the French correspondent for one of Cotta's newspapers, the ''Allgemeine Zeitung

The ''Allgemeine Zeitung'' was the leading political daily journal in Germany in the first part of the 19th century. It has been widely recognised as the first world-class German journal and a symbol of the German press abroad.

The ''Allgemein ...

''. The first event he covered was the Salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon ( ...

of 1831. His articles were eventually collected in a volume entitled ''Französische Zustände'' ("Conditions in France"). Heine saw himself as a mediator between Germany and France. If the two countries understood one another there would be progress. To further this aim he published ''De l'Allemagne'' ("On Germany") in French (begun 1833). In its later German version, the book is divided into two: '' Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland'' ("On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany") and ''Die romantische Schule'' ("The Romantic School"). Heine was deliberately attacking Madame de Staël's book ''De l'Allemagne

''On Germany'' (french: De l'Allemagne), also known in English as ''Germany'', is a book about German culture and in particular German Romanticism, written by the French writer Germaine de Staël. It promotes Romantic literature, introducing t ...

'' (1813) which he viewed as reactionary, Romantic and obscurantist. He felt de Staël had portrayed a Germany of "poets and thinkers", dreamy, religious, introverted and cut off from the revolutionary currents of the modern world. Heine thought that such an image suited the oppressive German authorities. He also had an Enlightenment view of the past, seeing it as mired in superstition and atrocities. "Religion and Philosophy in Germany" describes the replacement of traditional "spiritualist" religion by a pantheism

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ...

that pays attention to human material needs. According to Heine, pantheism had been repressed by Christianity and had survived in German folklore. He predicted that German thought would prove a more explosive force than the French Revolution.

Heine had had few serious love affairs, but in late 1834 he made the acquaintance of a 19-year-old Paris shopgirl, Crescence Eugénie Mirat, whom he nicknamed "Mathilde". Heine reluctantly began a relationship with her. She was illiterate, knew no German, and had no interest in cultural or intellectual matters. Nevertheless, she moved in with Heine in 1836 and lived with him for the rest of his life (they were married in 1841).

Heine had had few serious love affairs, but in late 1834 he made the acquaintance of a 19-year-old Paris shopgirl, Crescence Eugénie Mirat, whom he nicknamed "Mathilde". Heine reluctantly began a relationship with her. She was illiterate, knew no German, and had no interest in cultural or intellectual matters. Nevertheless, she moved in with Heine in 1836 and lived with him for the rest of his life (they were married in 1841).

Young Germany and Ludwig Börne

Heine and his fellow radical exile in Paris, Ludwig Börne, had become the role models for a younger generation of writers who were given the name " Young Germany". They included Karl Gutzkow, Heinrich Laube,Theodor Mundt

200px, Theodor Mundt

Theodor Mundt (September 19, 1808 – November 30, 1861) was a German critic and novelist. He was a member of the Young Germany group of German writers.

Biography

Born at Potsdam, Mundt studied philology and philosophy at Be ...

and Ludolf Wienbarg. They were liberal, but not actively political. Nevertheless, they still fell foul of the authorities.

In 1835, Gutzkow published a novel, ''Wally die Zweiflerin'' ("Wally the Sceptic"), which contained criticism of the institution of marriage and some mildly erotic passages. In November of that year, the German Diet consequently banned publication of works by the Young Germans in Germany and – on Metternich's insistence – Heine's name was added to their number. Heine, however, continued to comment on German politics and society from a distance. His publisher was able to find some ways of getting around the censors and he was still free, of course, to publish in France.

Heine's relationship with his fellow dissident Ludwig Börne was troubled. Since Börne did not attack religion or traditional morality like Heine, the German authorities hounded him less although they still banned his books as soon as they appeared.

Börne was the idol of German immigrant workers in Paris. He was also a republican, while Heine was not. Heine regarded Börne, with his admiration for

Heine's relationship with his fellow dissident Ludwig Börne was troubled. Since Börne did not attack religion or traditional morality like Heine, the German authorities hounded him less although they still banned his books as soon as they appeared.

Börne was the idol of German immigrant workers in Paris. He was also a republican, while Heine was not. Heine regarded Börne, with his admiration for Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

, as a puritanical neo-Jacobin and remained aloof from him in Paris, which upset Börne, who began to criticise him (mostly semi-privately). In February 1837, Börne died. When Heine heard that Gutzkow was writing a biography of Börne, he began work on his own, severely critical "memorial" of the man.

When the book was published in 1840 it was universally disliked by the radicals and served to alienate Heine from his public. Even his enemies admitted that Börne was a man of integrity so Heine's ''ad hominem'' attacks on him were viewed as being in poor taste. Heine had made personal attacks on Börne's closest friend Jeanette Wohl so Jeannette's husband challenged Heine to a duel. It was the last Heine ever fought – he received a flesh wound in the hip. Before fighting, he decided to safeguard Mathilde's future in the event of his death by marrying her.

Heine continued to write reports for Cotta's ''Allgemeine Zeitung'' (and, when Cotta died, for his son and successor). One event which really galvanised him was the 1840 Damascus Affair in which Jews in Damascus had been subject to

Heine continued to write reports for Cotta's ''Allgemeine Zeitung'' (and, when Cotta died, for his son and successor). One event which really galvanised him was the 1840 Damascus Affair in which Jews in Damascus had been subject to blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

and accused of murdering an old Catholic monk. This led to a wave of anti-Semitic persecution.

The French government, aiming at imperialism in the Middle East and not wanting to offend the Catholic party, had failed to condemn the outrage. On the other hand, the Austrian consul in Damascus had assiduously exposed the blood libel as a fraud. For Heine, this was a reversal of values: reactionary Austria standing up for the Jews while France temporised. Heine responded by dusting off and publishing his unfinished novel about the persecution of Jews in the Middle Ages, ''Der Rabbi von Bacherach''.

Political poetry and Karl Marx

German poetry took a more directly political turn when the new Frederick William IV ascended the Prussian throne in 1840. Initially it was thought he might be a "popular monarch" and during this honeymoon period of his early reign (1840–42) censorship was relaxed. This led to the emergence of popular political poets (so-called ''Tendenzdichter''), including Hoffmann von Fallersleben (author of '' Deutschlandlied'', the German anthem), Ferdinand Freiligrath and Georg Herwegh. Heine looked down on these writers on aesthetic grounds – they were bad poets in his opinion – but his verse of the 1840s became more political too. Heine's mode was satirical attack: against the Kings of Bavaria and Prussia (he never for one moment shared the belief that Frederick William IV might be more liberal); against the political torpor of the German people; and against the greed and cruelty of the ruling class. The most popular of Heine's political poems was his least typical, '' Die schlesischen Weber'' ("The Silesian Weavers"), based on the uprising of weavers in Peterswaldau in 1844. In October 1843, Heine's distant relative and German revolutionary,

In October 1843, Heine's distant relative and German revolutionary, Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, and his wife Jenny von Westphalen arrived in Paris after the Prussian government had suppressed Marx's radical newspaper. The Marx family settled in Rue Vaneau. Marx was an admirer of Heine and his early writings show Heine's influence. In December Heine met the Marxes and got on well with them. He published several poems, including ''Die schlesischen Weber'', in Marx's new journal ''Vorwärts'' ("Forwards"). Ultimately Heine's ideas of revolution through sensual emancipation and Marx's scientific socialism were incompatible, but both writers shared the same negativity and lack of faith in the bourgeoisie.

In the isolation he felt after the Börne debacle, Marx's friendship came as a relief to Heine, since he did not really like the other radicals. On the other hand, he did not share Marx's faith in the industrial proletariat and remained on the fringes of socialist circles. The Prussian government, angry at the publication of ''Vorwärts'', put pressure on France to deal with its authors, and Marx was deported to Belgium in January 1845. Heine could not be expelled from the country because he had the right of residence in France, having been born under French occupation. Thereafter Heine and Marx maintained a sporadic correspondence, but in time their admiration for each other faded. Heine always had mixed feelings about communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

. He believed its radicalism and materialism would destroy much of the European culture that he loved and admired.

In the French edition of "Lutetia" Heine wrote, one year before he died: "This confession, that the future belongs to the Communists, I made with an undertone of the greatest fear and sorrow and, oh!, this undertone by no means is a mask! Indeed, with fear and terror I imagine the time, when those dark iconoclasts come to power: with their raw fists they will batter all marble images of my beloved world of art, they will ruin all those fantastic anecdotes that the poets loved so much, they will chop down my Laurel forests and plant potatoes and, oh!, the herbs chandler will use my Book of Songs to make bags for coffee and snuff for the old women of the future – oh!, I can foresee all this and I feel deeply sorry thinking of this decline threatening my poetry and the old world order – And yet, I freely confess, the same thoughts have a magical appeal upon my soul which I cannot resist .... In my chest there are two voices in their favour which cannot be silenced .... because the first one is that of logic ... and as I cannot object to the premise "that all people have the right to eat", I must defer to all the conclusions....The second of the two compelling voices, of which I am talking, is even more powerful than the first, because it is the voice of hatred, the hatred I dedicate to this common enemy that constitutes the most distinctive contrast to communism and that will oppose the angry giant already at the first instance – I am talking about the party of the so-called advocates of nationality in Germany, about those false patriots whose love for the fatherland only exists in the shape of imbecile distaste of foreign countries and neighbouring peoples and who daily pour their bile especially on France".

In October–December 1843, Heine made a journey to Hamburg to see his aged mother and to patch things up with Campe with whom he had had a quarrel. He was reconciled with the publisher who agreed to provide Mathilde with an annuity for the rest of her life after Heine's death. Heine repeated the trip with his wife in July–October 1844 to see Uncle Salomon, but this time things did not go so well. It was the last time Heine left France. At the time, Heine was working on two linked but antithetical poems with Shakespearean titles: ''Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen'' ('' Germany. A Winter's Tale'') and ''Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum'' (''Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night's Dream''). The former is based on his journey to Germany in late 1843 and outdoes the radical poets in its satirical attacks on the political situation in the country. ''Atta Troll'' (actually begun in 1841 after a trip to the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

) mocks the literary failings Heine saw in the radical poets, particularly Freiligrath. It tells the story of the hunt for a runaway bear, Atta Troll, who symbolises many of the attitudes Heine despised, including a simple-minded egalitarianism and a religious view which makes God in the believer's image (Atta Troll conceives God as an enormous, heavenly polar bear). Atta Troll's cubs embody the nationalistic views Heine loathed.

''Atta Troll'' was not published until 1847, but ''Deutschland'' appeared in 1844 as part of a collection ''Neue Gedichte'' ("New Poems"), which gathered all the verse Heine had written since 1831. In the same year Uncle Salomon died. This put a stop to Heine's annual subsidy of 4,800 francs. Salomon left Heine and his brothers 8,000 francs each in his will. Heine's cousin Carl, the inheritor of Salomon's business, offered to pay him 2,000 francs a year at his discretion. Heine was furious; he had expected much more from the will and his campaign to make Carl revise its terms occupied him for the next two years.

In 1844, Heine wrote series of musical feuilletons over several different music seasons discussing the music of the day. His review of the musical season of 1844, written in Paris on 25 April of that year, is his first reference to Lisztomania, the intense fan frenzy directed toward Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

during his performances. However, Heine was not always honorable in his musical criticism. That same month, he wrote to Liszt suggesting that he might like to look at a newspaper review he had written of Liszt's performance ''before'' his concert; he indicated that it contained comments Liszt would not like. Liszt took this as an attempt to extort money for a positive review and did not meet Heine. Heine's review subsequently appeared on 25 April in ''Musikalische Berichte aus Paris'' and attributed Liszt's success to lavish expenditures on bouquets and to the wild behaviour of his hysterical female "fans". Liszt then broke relations with Heine. Liszt was not the only musician to be blackmailed by Heine for the nonpayment of "appreciation money". Meyerbeer had both lent and given money to Heine, but after refusing to hand over a further 500 francs was repaid by being dubbed "a music corrupter" in Heine's poem ''Die Menge tut es''.

Last years: the "mattress-grave"

In May 1848, Heine, who had not been well, suddenly fell paralyzed and had to be confined to bed. He would not leave what he called his "mattress-grave" (''Matratzengruft'') until his death eight years later. He also experienced difficulties with his eyes. It had been suggested that he suffered from multiple sclerosis or

In May 1848, Heine, who had not been well, suddenly fell paralyzed and had to be confined to bed. He would not leave what he called his "mattress-grave" (''Matratzengruft'') until his death eight years later. He also experienced difficulties with his eyes. It had been suggested that he suffered from multiple sclerosis or syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, a ...

, although in 1997 it was confirmed through an analysis of the poet's hair that he had suffered from chronic lead poisoning. He bore his sufferings stoically and he won much public sympathy for his plight. His illness meant he paid less attention than he might otherwise have done to the revolutions which broke out in France and Germany in 1848. He was sceptical about the Frankfurt Assembly and continued to attack the King of Prussia.

When the revolution collapsed, Heine resumed his oppositional stance. At first he had some hope Louis Napoleon might be a good leader in France but he soon began to share the opinion of Marx towards him as the new emperor began to crack down on liberalism and socialism. In 1848 Heine also returned to religious faith. In fact, he had never claimed to be an atheist. Nevertheless, he remained sceptical of organised religion.

He continued to work from his sickbed: on the collections of poems ''Romanzero'' and ''Gedichte (1853 und 1854)'', on the journalism collected in ''Lutezia'', and on his unfinished memoirs. During these final years Heine had a love affair with the young Camille Selden, who visited him regularly. He died on 17 February 1856 and was interred in the Paris Cimetière de Montmartre.

His tomb was designed by Danish sculptor Louis Hasselriis

Louis Hasselriis (12 January 1844 – 20 May 1912) was a Danish sculptor known for his public statuary.

Early life and education

Hasselriis was born in Hillerød, the son of Herman Edvard Louis H (1815–1907) and Sophie Frederikke Schondel ...

. It includes Heine's poem ''Where?'' (german: Wo?) engraved on three sides of the tombstone.

Legacy

Among the thousands of booksburned

Burned or burnt may refer to:

* Anything which has undergone combustion

* Burned (image), quality of an image transformed with loss of detail in all portions lighter than some limit, and/or those darker than some limit

* ''Burnt'' (film), a 2015 ...

on Berlin's Opernplatz in 1933, following the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

raid on the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

The was an early private sexology research institute in Germany from 1919 to 1933. The name is variously translated as ''Institute of Sex Research'', ''Institute of Sexology'', ''Institute for Sexology'' or ''Institute for the Science of Sexua ...

, were works by Heinrich Heine. To memorialize the event, one of the most famous lines of Heine's 1821 play ''Almansor'', spoken by the Muslim Hassan upon hearing that Christian conquerors burned the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

at the marketplace of Granada, was engraved in the ground at the site: "Das war ein Vorspiel nur, dort wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen." ("That was but a prelude; where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.")

In 1835, 98 years before Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

and the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

seized power in Germany, Heine wrote in his essay "The History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany":

Christianity – and that is its greatest merit – has somewhat mitigated that brutal Germanic love of war, but it could not destroy it. Should that subduing talisman, the cross, be shattered, the frenzied madness of the ancient warriors, that insane Berserk rage of which Nordic bards have spoken and sung so often, will once more burst into flame. This talisman is fragile, and the day will come when it will collapse miserably. Then the ancient stony gods will rise from the forgotten debris and rub the dust of a thousand years from their eyes, and finallyThe North American Heine Society was formed in 1982.Thor Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, ...with his giant hammer will jump up and smash the Gothic cathedrals. ... Do not smile at my advice – the advice of a dreamer who warns you against Kantians, Fichteans, and philosophers of nature. Do not smile at the visionary who anticipates the same revolution in the realm of the visible as has taken place in the spiritual. Thought precedes action as lightning precedes thunder. German thunder is of true Germanic character; it is not very nimble, but rumbles along ponderously. Yet, it will come and when you hear a crashing such as never before has been heard in the world's history, then you know that the German thunderbolt has fallen at last. At that uproar the eagles of the air will drop dead, and lions in the remotest deserts of Africa will hide in their royal dens. A play will be performed in Germany which will make the French Revolution look like an innocent idyll.

Heine in Nazi Germany

Heine's writings were abhorred by the Nazis and one of their political mouthpieces, the '' Völkischer Beobachter'', made noteworthy efforts to attack him. Within the pantheon of the "Jewish cultural intelligentsia" chosen for anti-Semitic demonization, perhaps nobody was the recipient of more National Socialist vitriol than Heinrich Heine. When a memorial to Heine was completed in 1926, the paper lamented that Hamburg had erected a "Jewish Monument to Heine and Damascus...one in which '' Alljuda'' ruled!". Editors for the ''Völkischer Beobachter'' referred to Heine's writing as degenerate on multiple occasions as did Alfred Rosenberg. Correspondingly, as part of the effort to dismiss and hide Jewish contribution to German art and culture, all Heine monuments were removed or destroyed duringNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and Heine's books were suppressed and, from 1940 on, banned.

The popularity of many songs to Heine's lyrics represented a problem for the policy of silencing and proposals such as bans or rewriting the lyrics were discussed. However, in contrast to an often-made claim, there is no evidence that poems such as "" were included in anthologies as written by an "unknown author".

Music

Many composers have set Heine's works to music. They includeRobert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

(especially his Lieder cycle '' Dichterliebe''), Friedrich Silcher (who wrote a popular setting of "Die Lorelei", one of Heine's best known poems), Franz Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wo ...

, Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

, Felix Mendelssohn, Fanny Mendelssohn, Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped wit ...

, Hugo Wolf, Richard Strauss, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

, Edward MacDowell

Edward Alexander MacDowell (December 18, 1860January 23, 1908) was an American composer and pianist of the late Romantic period. He was best known for his second piano concerto and his piano suites '' Woodland Sketches'', ''Sea Pieces'' and '' ...