Hans Globke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hans Josef Maria Globke (10 September 1898 – 13 February 1973) was a German administrative lawyer, who worked in the Prussian and Reich Ministry of the Interior in the Reich, during the

From 1934 onwards, Globke continued to be responsible mainly for name changes and civil status issues; from 1937, international issues in the field of citizenship and

From 1934 onwards, Globke continued to be responsible mainly for name changes and civil status issues; from 1937, international issues in the field of citizenship and  Globke was responsible for preparing legal commentaries and explanations for his areas of responsibility. In 1936, together with his superior, State Secretary Wilhelm Stuckart, he published the first commentary on the

Globke was responsible for preparing legal commentaries and explanations for his areas of responsibility. In 1936, together with his superior, State Secretary Wilhelm Stuckart, he published the first commentary on the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

and the time of National Socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Naz ...

and was later the Under-Secretary of State and Chief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

of the German Chancellery

The German Chancellery (german: Bundeskanzleramt, , more faithfully translated as ''Federal Chancellery'' or ''Office of the Federal Chancellor'') is an agency serving the executive office of the chancellor of Germany, the head of the federal go ...

in West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

from 28 October 1953 to 15 October 1963 under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman who served as the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the Christian Dem ...

. It is the most prominent example of the continuity of the administrative elites between Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the early West Germany.

In 1936, during the Weimar Republic Globke wrote a legal annotation on the antisemitic Nuremberg Race Laws

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented in Nazi Germany under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, based on a specific racist doctrine asserting the superiority of the Aryan race, which claimed scientific leg ...

that did not express any objection to the discrimination against Jews, placing the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

on a firmer legal ground and setting the path to the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. By 1938, Globke had been promoted to ''Ministerialdirigent'' in the Office for Jewish Affairs in the Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministr ...

, where he produced the , a law that forced Jewish men to take the middle name ''Israel'' and Jewish women ''Sara'' for easier identification. In 1941, during the Nazi period, he issued another statute that stripped Jews in occupied territories of their statehood and possessions. Globke was identified as the author of an interior ministry report from France, written in racist language, that complained of "coloured blood into Europe" and called for the "elimination" of its "influences" on the gene pool.

Globke later had a controversial career as Secretary of State and Chief of Staff of the West German Chancellery. A strident anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

, Globke became a powerful ''éminence grise

An ''éminence grise'' () or grey eminence is a powerful decision-maker or adviser who operates "behind the scenes", or in a non-public or unofficial capacity.

This phrase originally referred to François Leclerc du Tremblay, the right-hand man ...

'' of the West German government, and was widely regarded as one of most influential public officials in the government of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman who served as the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the Christian Dem ...

. Globke had a major role in shaping the course and structure of the state and West Germany's alignment with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. He was also an important figure in West Germany's anti-communist policies at the domestic and international level and in the Western intelligence community, and was the German government's main liaison with NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

and other Western intelligence services, especially the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA). During his lifetime, only some parts of his role in the Nazi state were known to the broader public.

Early life and education

Globke was born inDüsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in ...

, Rhine Province

The Rhine Province (german: Rheinprovinz), also known as Rhenish Prussia () or synonymous with the Rhineland (), was the westernmost province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia, within the German Reich, from 1822 to 1946. ...

, the son of the cloth wholesaler Josef Globke and his wife Sophie (née Erberich), both Roman Catholics and supporters of the Centre Party (Deutsche Zentrumspartei). Shortly after Hans's birth, the family moved to Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th ...

, where his father opened a draper's shop. When he finished his secondary education at the elite Catholic Kaiser-Karl-Gymnasium and completing his Abitur

''Abitur'' (), often shortened colloquially to ''Abi'', is a qualification granted at the end of secondary education in Germany. It is conferred on students who pass their final exams at the end of ISCED 3, usually after twelve or thirteen ye ...

in 1916, he was drafted, serving until the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in an artillery unit on the Western Front. After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, he studied law and political science at the University of Bonn

The Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn (german: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn) is a public research university located in Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It was founded in its present form as the ( en, Rhine ...

, University of Cologne

The University of Cologne (german: Universität zu Köln) is a university in Cologne, Germany. It was established in the year 1388 and is one of the most prestigious and research intensive universities in Germany. It was the sixth university to ...

and the University of Giessen

University of Giessen, official name Justus Liebig University Giessen (german: Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen), is a large public research university in Giessen, Hesse, Germany. It is named after its most famous faculty member, Justus von ...

. In 1921, Globke became a legal trainee when he passed the state examination (german: Referendarexamen) at the Higher Regional Court of Cologne. For a year he worked as a trainee in Eschweiler

Eschweiler (, Ripuarian: ) is a municipality in the district of Aachen in North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany on the river Inde, near the German-Belgian-Dutch border, and about east of Aachen and west of Cologne.

History

* Celts (fi ...

, Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

and Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

. In 1922, Globke qualified as a doctor of law

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor (LL ...

(Dr. jur.) at the University of Giessen

University of Giessen, official name Justus Liebig University Giessen (german: Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen), is a large public research university in Giessen, Hesse, Germany. It is named after its most famous faculty member, Justus von ...

, with a dissertation titled ''The immunity of the members of the Reichstag and the Landtag

A Landtag (State Diet) is generally the legislative assembly or parliament of a federated state or other subnational self-governing entity in German-speaking nations. It is usually a unicameral assembly exercising legislative competence in non ...

'' (german: Die Immunität der Mitglieder des Reichstages und der Landtage). In the same year, his father died and Globke became the main wage-earner for the family.

While studying, Globke, a practising Catholic, joined the Bonn chapter of the Cartellverband

The Union of Catholic German Student Fraternities (german: Cartellverband der katholischen deutschen Studentenverbindungen or ''Cartellverband'' (CV)) is a German umbrella organization of Catholic male student fraternities (Studentenverbindung). ...

(KdStV), the German Catholic Students' Federation. His close contacts with fellow KdStV members and his membership from 1922 in the Catholic Centre Party played a significant role in his later political life. Globke finished his '' Assessorexamen'' in 1924 and briefly served as a judge in the Aachen district court. He became vice police-chief of Aachen in 1925 and governmental civil servant with a rank of ''Regierungsassessor'' (District Assessor) in 1926.

In 1934, he married Augusta Vaillant, with whom he had two sons and one daughter.

Ministerial career

In December 1929, Globke entered the Higher Civil Service at the lowest rank of Government Counciller in thePrussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

Ministry of the Interior. There he worked in area like standesamt, demilitarisation

Demilitarisation or demilitarization may mean the reduction of state armed forces; it is the opposite of militarisation in many respects. For instance, the demilitarisation of Northern Ireland entailed the reduction of British security and military ...

of the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

and questions related to the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

.

Globke was not affected by the personnel purges of the Prussian ministerial bureaucracy by the Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany ...

government, which removed republican-oriented officials after the coup d'état in Prussia on 20 July 1932. On the contrary, on 12 August 1932, he was appointed head of the constitutional department in Department I. This department also included the civil status department, which was responsible for regulating name change matters. In October 1932, under Globke's leadership, a set of rules, known as the "Ordinance on the Responsibility for Changing Surnames and First Names of 21 November 1932" (german: Verordnung über die Zuständigkeit zur Änderung von Familiennamen und Vornamen vom 21. November 1932 were created. The rule made it harder for Germans of Jewish ancestry in Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

to change their last names to less obviously Jewish names, followed by guidelines for their implementation in December 1932.

This ordinance tied in with the restrictive principles for the treatment of Jewish name changes formulated in the Prussian Ministry of the Interior in 1909 and 1921, but now placed these changes openly in the context of an anti-Jewish attitude. In the circular issued by Globke on naming rights, it was said that every name change impairs "the recognisability of origin from a family", facilitates "the obscuration of marital status" and conceals "the blood descent".

This unequal treatment of the Jews in the final phase of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, in which Globke played a major role, is considered by researchers and in the earlier case law of East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In t ...

to be a precursor to name-related discrimination during the early Nazi era. For the historian and the criminal lawyer , Globke "was therefore one of the pioneers of later racial legislation as early as the Weimar Republic."

Career during Nazism

After the seizure of power by the Nazi Party in early 1933, Globke was involved in the drafting of a series of laws aimed at the co-ordination (german: Gleichschaltung) of the legal system ofPrussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

with the Reich. In December 1933, he was appointed to the upper government council, which Globke later said had been postponed due to his doubts over the legality of the so-called Prussian coup of 1932, which was well known in the Ministry. Globke helped to formulate the Enabling Act of 1933

The Enabling Act (German: ') of 1933, officially titled ' (), was a law that gave the German Cabinet – most importantly, the Chancellor – the powers to make and enforce laws without the involvement of the Reichstag or Weimar Pres ...

, which effectively gave Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

dictatorial powers. He was also the author of the law of 10 July 1933 concerning the dissolution of the Prussian State Council

The Prussian State Council (german: Preußischer Staatsrat) was the upper chamber of the bicameral legislature of the Free State of Prussia between 1920 and 1933. The lower chamber was the Prussian Landtag (''Preußischer Landtag'').

Impleme ...

and of further legislation that co-ordinated all Prussian parliamentary bodies.

On 1 November 1934, following the unification of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior with the Reich Ministry of the Interior, Globke took a position as a speaker in the newly formed Reich and Prussian Ministry of the Interior under Reich Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), who served as Reich Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate ...

, where he worked until 1945. In 1938 Globke received his final promotion of the Nazi period, to the ministerial council.

Measures to exclude and persecute Jews

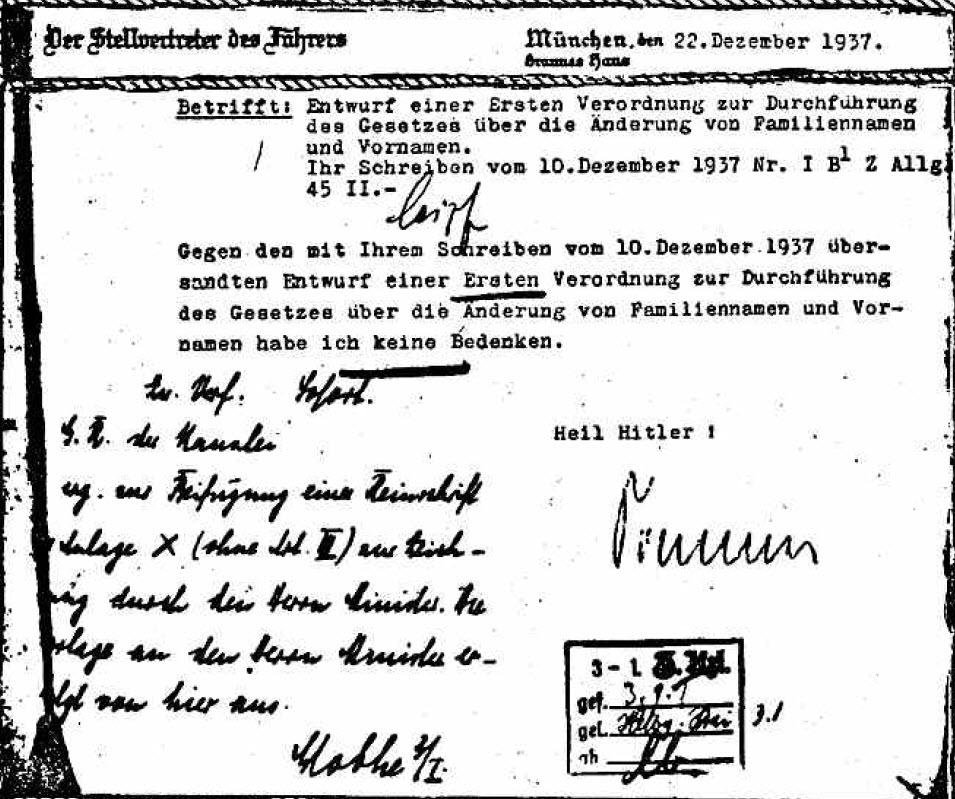

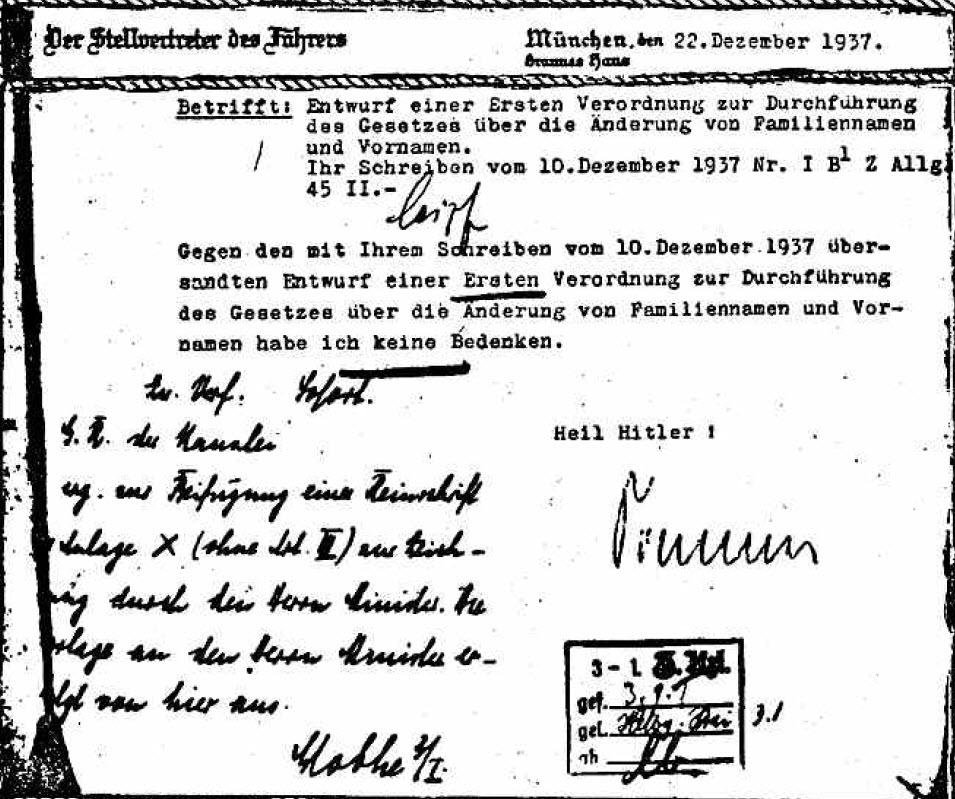

From 1934 onwards, Globke continued to be responsible mainly for name changes and civil status issues; from 1937, international issues in the field of citizenship and

From 1934 onwards, Globke continued to be responsible mainly for name changes and civil status issues; from 1937, international issues in the field of citizenship and option contract

An option contract, or simply option, is defined as "a promise which meets the requirements for the formation of a contract and limits the promisor's power to revoke an offer". Option contracts are common in professional sports.

An option contrac ...

s were added to his brief. As a co-supervisor, he also dealt with "general race issues", immigration and emigration, and matters related to the anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

" Blood Protection Act" (german: Rassenschande) laws covering sexual relations between Aryans

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ...

and non-Aryans. He co-authored the official legal commentary on the new Reich Citizenship Law

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of th ...

, one of the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of ...

introduced at the Nazi Party Congress in September 1935, which revoked the citizenship of German Jews

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (''circa'' 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish ...

, as well as various legal regulations. Globke's work also included the elaboration of templates and drafts for laws and ordinances. In this context, he had a leading role in the preparation of the first Ordinance on the Reich's civil law (enacted on 14 November 1935), The Law for the Defense of German Blood and Honour (enacted 18 October 1935), and the (enacted on 3 November 1937). The "J" which was imprinted in the passports of Jews was designed by Globke.

Globke was responsible for preparing legal commentaries and explanations for his areas of responsibility. In 1936, together with his superior, State Secretary Wilhelm Stuckart, he published the first commentary on the

Globke was responsible for preparing legal commentaries and explanations for his areas of responsibility. In 1936, together with his superior, State Secretary Wilhelm Stuckart, he published the first commentary on the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of ...

and their implementing regulations. This proved to be particularly influential for the interpretation of the Nuremberg Laws because it was given an official character. Originally, Globke was only supposed to comment on matrimonial issues as Stuckart wanted to do the rest of the work himself, but Stuckart became ill for a long time, so Globke wrote the commentary on his own. Stuckart ended up only writing the extensive introduction. In this context, Globke's later defense lawyers pointed out that he was not to be held responsible for Stuckart's racist choice of words and that his commentary on the law interpreted the Nuremberg Laws narrowly in comparison to later comments. In individual cases, especially in the case of so-called mixed marriages, this has proven to be beneficial for those affected.

Globke also authored the (enacted 5 January 1938), the (enacted 17 August 1938), and the associated implementing ordinances. According to the ordinances, Jews who did not bear any of the given names in an attached list were required to add a middle name to their own: "Sara" for women and "Israel" for men. The list of male first names began with Abel, Abiezer, Abimelech, Abner, Absalom, Ahab, Ahaziah, Ahasuerus, and so on. Some of the names on the list were fictitious or selected in a controversial manner. It is unclear whether this was due to an intention to further disparage Jews, or whether they were errors and inaccuracies. Insofar as they were particularly widespread among German Jews at the time, even the names of Christian saints were included on this list, e.g. B. "Isidor", the name of the theologian Isidor of Seville

Isidore of Seville ( la, Isidorus Hispalensis; c. 560 – 4 April 636) was a Spanish scholar, theologian, and archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of 19th-century historian Montalembert, as "the last scholar of t ...

or Saint Isidor of Madrid, the patron of many southern German village churches. By registering the population regarded as Jewish, Globke created the administrative prerequisites that facilitated to a great extent the rounding up and deportation of Jews during the Holocaust that, began at the end of 1941.

Globke also served as chief legal adviser to the Office for Jewish Affairs in the Ministry of Interior, headed by Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

'' On 25 April 1938, Globke was praised by the Reich Interior Minister

At the beginning of the war, Globke was responsible for the new German imperial borders in the West that were the responsibility of the Reich Ministry of the Interior. He made several trips to the conquered territories. The historian Peter Schöttler suspected that Globke was probably the author of a memorandum to Hitler in June 1940 discussing the idea of State Secretary Stuckart proposing a far-reaching annexation of the East French and Belgian territories, which would have involved the deportation of about 5 million people.

He applied for membership of the

At the beginning of the war, Globke was responsible for the new German imperial borders in the West that were the responsibility of the Reich Ministry of the Interior. He made several trips to the conquered territories. The historian Peter Schöttler suspected that Globke was probably the author of a memorandum to Hitler in June 1940 discussing the idea of State Secretary Stuckart proposing a far-reaching annexation of the East French and Belgian territories, which would have involved the deportation of about 5 million people.

He applied for membership of the

In the post-war era Globke rose to become one of the most powerful people in the German government. On 26 September 1949, Konrad Adenauer "had no reservations whatsoever" in appointing Globke to be one of his closest aides, with his appointment to the position of undersecretary at the

In the post-war era Globke rose to become one of the most powerful people in the German government. On 26 September 1949, Konrad Adenauer "had no reservations whatsoever" in appointing Globke to be one of his closest aides, with his appointment to the position of undersecretary at the

In the early 1960s, there was a vigorous campaign in

In the early 1960s, there was a vigorous campaign in

'' On 25 April 1938, Globke was praised by the Reich Interior Minister

Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), who served as Reich Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate ...

as "the most capable and efficient official in my ministry" when it came to drafting anti-Semitic laws.

During the war

At the beginning of the war, Globke was responsible for the new German imperial borders in the West that were the responsibility of the Reich Ministry of the Interior. He made several trips to the conquered territories. The historian Peter Schöttler suspected that Globke was probably the author of a memorandum to Hitler in June 1940 discussing the idea of State Secretary Stuckart proposing a far-reaching annexation of the East French and Belgian territories, which would have involved the deportation of about 5 million people.

He applied for membership of the

At the beginning of the war, Globke was responsible for the new German imperial borders in the West that were the responsibility of the Reich Ministry of the Interior. He made several trips to the conquered territories. The historian Peter Schöttler suspected that Globke was probably the author of a memorandum to Hitler in June 1940 discussing the idea of State Secretary Stuckart proposing a far-reaching annexation of the East French and Belgian territories, which would have involved the deportation of about 5 million people.

He applied for membership of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

for career reasons in 1940, but the application was rejected on 24 October 1940 by Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

, reportedly because of his former membership of the Centre Party, which had represented Roman Catholic voters in Weimar Germany

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

.

At the beginning of September 1941, Globke accompanied Interior Minister Frick and State Secretary Stuckart on an official visit to Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

, which at that time was a client state of the German Reich. Immediately following this visit, the government of Slovakia announced the introduction of the so-called Jewish Code, which provided the legal basis for the later expropriations and deportations of Slovak Jews. In 1961, Globke denied there was any connection between the two events and the allegation that he had participated in the creation of the Code. Clear evidence for it was never verified. According to CIA documents, Globke was possibly also responsible for the deportation of 20,000 Jews from Northern Greece

Northern Greece ( el, Βόρεια Ελλάδα, Voreia Ellada) is used to refer to the northern parts of Greece, and can have various definitions.

Administrative regions of Greece

Administrative term

The term "Northern Greece" is widely used ...

to Nazi extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The ...

s in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

.

Globke submitted a final application for Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

membership, but the application was rejected in 1943, again due to his former affiliation to the Centre Party.

On the other hand, Globke maintained contacts with military and civilian resistance groups. He was the informant of the Berlin Bishop Konrad von Preysing

Johann Konrad Maria Augustin Felix, Graf von Preysing Lichtenegg-Moos (30 August 1880 – 21 December 1950) was a German prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. Considered a significant figure in Catholic resistance to Nazism, he served as B ...

and had knowledge of the coup preparations by the opponents of Hitler Carl Friedrich Goerdeler

Carl Friedrich Goerdeler (; 31 July 1884 – 2 February 1945) was a monarchist conservative German politician, executive, economist, civil servant and opponent of the Nazi regime. He opposed some anti-Jewish policies while he held office and was ...

and Ludwig Beck

Ludwig August Theodor Beck (; 29 June 1880 – 20 July 1944) was a German general and Chief of the German General Staff during the early years of the Nazi regime in Germany before World War II. Although Beck never became a member of the Na ...

. According to reports by Jakob Kaiser

Jakob Kaiser (8 February 1888 – 7 May 1961) was a German politician and resistance leader during World War II.

Jakob Kaiser was born in Hammelburg, Lower Franconia, Kingdom of Bavaria. Following in his father's footsteps, Kaiser began a career ...

and Otto Lenz, in the event that the attempt to overthrow the National Socialist regime had succeeded, Globke was earmarked for a senior ministerial post in an imperial government formed by Goerdeler. However, no evidence ever emerged to support Globke's later assertion that the National Socialists wanted to arrest him in 1945, but were prevented by the advance of the Allies.

Post-war period

Immediately after the war, his close friendHerbert Engelsing

Herbert ''Enke'' Wilhelm Engelsing (born 2 September 1904 in Overath, died 10 February 1962 in Konstanz) was a right-wing German Catholic lawyer in Berlin and resistance fighter against the Nazi regime. When the Nazi regime began, Engelsing fou ...

and friends from the Catholic church helped to promote Globke to the British, ensuring his political survival. Although the British had doubts, the need for Globke's expertise after the war became so great that they were willing to take a chance in employing him in the drafting of election law. Once freed from British obligation on 1 July 1946, he was appointed as the city treasurer in Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th ...

, a position he held for three years.

During the process of denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

, Globke stated that he had been part of the resistance against National Socialism, and was therefore classified by the Arbitration Chamber on 8 September 1947 in Category V: Persons Exonerated. Globke was a witness for both the defence and the prosecution at the Wilhelmstraße trial. At Stuckart's trial, he testified as a witness for the defendant, "I knew that the Jews were mass murdered".

At the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

, he appeared at the Wilhelmstraße trial as a witness for both the prosecution and the defence. When questioned in the trial of his former superior Wilhelm Stuckart, he confirmed that he knew that "Jews were being put to death ''en masse''". He had known at that time that "the extermination of the Jews was systematic", but, he said, restricting his statement, "not that it referred to all Jews".

Career in the Adenauer government

In the post-war era Globke rose to become one of the most powerful people in the German government. On 26 September 1949, Konrad Adenauer "had no reservations whatsoever" in appointing Globke to be one of his closest aides, with his appointment to the position of undersecretary at the

In the post-war era Globke rose to become one of the most powerful people in the German government. On 26 September 1949, Konrad Adenauer "had no reservations whatsoever" in appointing Globke to be one of his closest aides, with his appointment to the position of undersecretary at the German Chancellery

The German Chancellery (german: Bundeskanzleramt, , more faithfully translated as ''Federal Chancellery'' or ''Office of the Federal Chancellor'') is an agency serving the executive office of the chancellor of Germany, the head of the federal go ...

, despite protests from the opposition parties in the Bundestag and the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

. There were three main reasons for this: firstly as Catholics that shared a common environment in their upbringing in the Rhineland, secondly Adenauer considered him an effective and reliable civil servant and thirdly, Globke was absolutely devoted to Adenauer. The appointment of a Nazi official was in itself not unusual; the historian Gunnar Take, from the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

, established that only three out of 50 officials of the interior ministry who were of working age during the Nazi era had been anti-fascists. In 1951, he issued a statute that restored back pay, pensions, and advancement to civil servants who had served under the Nazi regime, including himself. John Le Carré

David John Moore Cornwell (19 October 193112 December 2020), better known by his pen name John le Carré ( ), was a British and Irish author, best known for his espionage novels, many of which were successfully adapted for film or television. ...

wrote that these were "rights as they would have enjoyed if the Second World War hadn't taken place, or if Germany had won it. In a word, they would be entitled to whatever promotion would have come their way had their careers proceeded without the inconvenience of an Allied victory". At the end of October 1953, following Otto Lenz's election to the Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Comm ...

in the election of the previous month, Globke succeeded Lenz as Secretary of State at the Federal Chancellery, wielding a great deal of power behind the scenes and therefore an important pillar of Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman who served as the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the Christian Dem ...

's "chancellor democracy" (german: Kanzlerdemokratie).

Globke served as Chief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

of the Chancellery from 1953 to 1963. As such he was one of the closest aides to Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Adenauer, with significant influence over government policy. He advised Adenauer on political decisions during joint walks in the garden of the Chancellor's office, such as the reparations agreement with Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. His areas of responsibility and his closeness to the Chancellor arguably made him one of the most powerful members of the government; he was responsible for running the Chancellery, recommending the people who were appointed to roles in the government, coordinating the government's work, for the establishment and oversight of the West German intelligence service and for all matters of national security

National security, or national defence, is the security and defence of a sovereign state, including its citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of government. Originally conceived as protection against military att ...

. He was the German government's main liaison with NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

and other western intelligence services, especially the CIA. He also maintained contact with the party apparatus and became "a kind of hidden secretary general" to the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), and contact with the Chancellor usually had to go through him. As Adenauer and everyone else knew of his previous career, the Chancellor could be assured of his absolute loyalty.

Globke's key position as chief of staff to Adenauer, responsible for matters of national security, made both the West German government and CIA officials wary of exposing his past, despite their full knowledge of it. This led, for instance, to the withholding of Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

'' Israeli government The Cabinet of Israel (officially: he, ממשלת ישראל ''Memshelet Yisrael'') exercises executive authority in the State of Israel. It consists of ministers who are chosen and led by the prime minister. The composition of the governmen ...

and '' Israeli government The Cabinet of Israel (officially: he, ממשלת ישראל ''Memshelet Yisrael'') exercises executive authority in the State of Israel. It consists of ministers who are chosen and led by the prime minister. The composition of the governmen ...

Nazi hunter

A Nazi hunter is an individual who tracks down and gathers information on alleged former Nazis, or SS members, and Nazi collaborators who were involved in the Holocaust, typically for use at trial on charges of war crimes and crimes against huma ...

s in the late 1950s, and CIA pressure in 1960 on ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy ...

'' magazine to delete references to Globke from its recently obtained Eichmann memoirs.

According to CIA documents, in the 1961 election campaign against Willy Brandt (who was later elected Chancellor in 1969), Globke offered Brandt a brazen deal not to make allegations of treason against him resulting from his time in exile, a campaign topic, provided that the SPD would not use Globke's Nazi past as an election topic. Globke threatened Brandt with a new campaign against him, initiated by the communists. However, Globke believed that it was in the national interest to stop the campaigns and the continual aspersions about the past would stop the population finding peace. Brandt decided not make Globke's Nazi past a campaign issue.

Globke left office together with the Adenauer administration in 1963, and was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany by President Heinrich Lübke

Karl Heinrich Lübke (; 14 October 1894 – 6 April 1972) was a German politician, who served as president of West Germany from 1959 to 1969.

He suffered from deteriorating health towards the end of his career and is known for a series of emba ...

. He remained active as an adviser for Adenauer and the CDU during the 1960s.

Gehlen organisation

In 1950, Globke began working with Reinhard Gehlen, who Globke considered a close friend with complimentary views. An obsessive anti-communist, Gehlen was a former intelligence officer who had held the rank oflieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

in the ''Heer'' during World War II. Gehlen was then the director of Foreign Armies East Foreign Armies East, or Fremde Heere Ost (FHO), was a military intelligence organization of the ''Oberkommando des Heeres'' (OKH), the Supreme High Command of the German Army during World War II. It focused on analyzing the Soviet Union and other E ...

, a military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

organisation that operated against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front. Gehlen had created the Gehlen Organization, known as ''The Org'', in 1946 to spy on the Soviet Union, with approval and funding from the CIA.

In April 1956, on orders from Adenauer, Globke established the Federal Intelligence Service (BND, Bundesnachrichtendienst), the successor organisation to the Gehlen Organisation.

Nazi past

Political debate

The fact that a man like Globke played a leading role in German politics again shortly after the founding of the Federal Republic, triggered a bitterparliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

debate on 12 July 1950 when Adolf Arndt

Adolf Arndt (12 March 1904 – 13 February 1974) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and former member of the German Bundestag.

Life

Born in Königsberg as the son of the Law professor ''Gustav Adolf Arndt'', he moved ...

then the legal spokesman for the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

(SPD), read an excerpt from the commentaries on the Nuremberg Laws in which Globke discusses whether or not "racial defilement" committed abroad could be punished. Federal Interior Minister Gustav Heinemann

Gustav Walter Heinemann (; 23 July 1899 – 7 July 1976) was a German politician who was President of West Germany from 1969 to 1974. He served as mayor of Essen from 1946 to 1949, West German Minister of the Interior from 1949 to 1950, and Mini ...

(CDU) referred in his answer to the exonerating testimony of the Nuremberg prosecutor Robert Kempner

Robert Max Wasilii Kempner (17 October 1899 – 15 August 1993) was a German lawyer who played a prominent role during the Weimar Republic and who later served as assistant U.S. chief counsel during the International Military Tribunal at Nurembe ...

, that Globke had served with his willingness to testify.

Although Globke was controversial because of his Nazi past, Adenauer was loyal to Globke until the end of his term in 1963. On one hand, Adenauer commented on the debate over Globke's participation in the drafting of the Nuremberg race laws

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented in Nazi Germany under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, based on a specific racist doctrine asserting the superiority of the Aryan race, which claimed scientific leg ...

with the words "You don't throw away dirty water as long as you don't have clean water" (german: Man schüttet kein schmutziges Wasser weg, solange man kein sauberes hat). On the other hand, Adenauer stated in a newspaper interview on 25 March 1956 that claims Globke was a willing helper of the Nazis, lacked any basis. Many people, including from the ranks of the Catholic Church, certified that Globke had repeatedly campaigned on behalf of persecuted people.

In the opinion of the journalist Harald Jähner

Harald Jähner (born March 26, 1953) is a German journalist and author. Since 2011 he has been an honorary professor of cultural journalism at the Berlin University of the Arts.

Biography

Jähner studied literature, history and art history in ...

, Globke's continued presence led to "disgraceful state measures to prevent criminal prosecution and obstruction of justice" and repeatedly offered the GDR a welcome opportunity to describe the Federal Republic as "fascist". This was especially true after 1960, when the Israeli intelligence service Mossad

Mossad ( , ), ; ar, الموساد, al-Mōsād, ; , short for ( he, המוסד למודיעין ולתפקידים מיוחדים, links=no), meaning 'Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations'. is the national intelligence agency ...

tracked Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

'' Argentina Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

. that loyalty to Globke increasingly proved to be a burden on Adenauer's government. The German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) had known since 1952 that Eichmann was living in '' Argentina Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

and working at Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz (), commonly referred to as Mercedes and sometimes as Benz, is a German luxury and commercial vehicle automotive brand established in 1926. Mercedes-Benz AG (a Mercedes-Benz Group subsidiary established in 2019) is headquarte ...

.

Whether or not Globke knew of Adolf Eichmann's whereabouts in Argentina at the end of the 1950s was still the subject of political debate in May 2013 when the parliamentry group Alliance 90/The Greens

Alliance 90/The Greens (german: Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, ), often simply referred to as the Greens ( ), is a green political party in Germany. It was formed in 1993 as the merger of The Greens (formed in West Germany in 1980) and Alliance 90 (for ...

asked the Bundestag for clarification of their relationship and the Federal Intelligence Service to Eichmann. The Bundestag was unable to answer it.

West German investigation

The former administrative officer ofArmy Group E

Army Group E (''Heeresgruppe E'') was a German Army Group active during World War II.

Army Group E was created on 1 January 1943 from the 12th Army. Units from this Army Group were distributed throughout the Eastern Mediterranean area, includin ...

in Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, Max Merten

Max Merten (8 September 1911 in Berlin-Lichterfelde – 21 September 1971 in West Berlin) was the ''Kriegsverwaltungsrat'' (military administration counselor) of the Nazi German occupation forces in Thessaloniki in northern Greece during World Wa ...

, had accused Globke of being heavily responsible for the Holocaust in Greece, as he could have prevented the deaths of 20,000 Jews in Thessaloniki when Eichmann contacted the Reich Interior Ministry and asked for Globke's permission to kill them. When these accusations became known, they prompted preliminary criminal proceedings to be initiated against Globke by Fritz Bauer

Fritz Bauer (16 July 1903 – 1 July 1968) was a German Jewish judge and prosecutor. He was instrumental in the post-war capture of former Holocaust planner Adolf Eichmann and played an essential role in beginning the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials ...

, the chief public prosecutor of Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are ...

. The investigation was transferred to the public prosecutor's office in Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

in May 1961 after an intervention by Adenauer, where it was closed due to lack of evidence.

Trial in East Berlin

In the early 1960s, there was a vigorous campaign in

In the early 1960s, there was a vigorous campaign in East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In t ...

, led by the Politburo member Albert Norden

Albert Norden (4 December 1904 – 30 May 1982) was a German communist politician.

Early years

Albert Norden was born in Myslowitz, Silesia on 4 December 1904, one of the five recorded children born to the liberal rabbi (1870–1943) and hi ...

of the Ministry of State Security, against the so-called "author of the Nuremberg Blood Laws" as well an "agitator and organiser of the persecutions of the Jews". Norden's goal was to prove that Globke was in contact with Eichmann. In a 1961 memorandum, Norden stated that "in collaboration with Erich Mielke

Erich Fritz Emil Mielke (; 28 December 1907 – 21 May 2000) was a German communist official who served as head of the East German Ministry for State Security (''Ministerium für Staatsicherheit'' – MfS), better known as the Stasi, from 1957 u ...

, certain materials should be procured or produced. We definitely need a document that somehow proves Eichmann's direct cooperation with Globke".

In July 1963, the trial, a show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt or innocence of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal the presentation of both the accusation and the verdict to the public so ...

was held in the Supreme Court of East Germany which was presided over by . The trial was not about establishing the truth, but about propagandistically reproaching the Federal Republic for its Nazi past and emphasising its own anti-fascist founding myth. On 23 July 1963, Globke was sentenced in ''in absentia

is Latin for absence. , a legal term, is Latin for "in the absence" or "while absent".

may also refer to:

* Award in absentia

* Declared death in absentia, or simply, death in absentia, legally declared death without a body

* Election in ab ...

'', to life imprisonment "for continued war crimes committed with complicity and crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

in partial combination with murder". In the trial and in the extensive reasons for the verdict, the court tried to prove the alleged "similarity of essence of the Bonn regime" with Hitler's terror state.

However, such East German trials were not recognised outside of the Soviet bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that exist ...

, least of all by West Germany. On the 10 July 1963, the affair was denounced by the West German Government as a show trial. The fact that much of the criticism of Globke came from the Soviet bloc, and that it mixed genuine information with false accusations, made it easier for the West Germans and the Americans to dismiss it as communist propaganda.

Retirement

After his retirement, Globke decided to move toSwitzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, where his wife Augusta had bought a property in Chardonne

Chardonne is a municipality in the district of Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut in the canton of Vaud in Switzerland.

History

Chardonne is first mentioned in 1001 as ''Cardona''.

Geography

Chardonne has an area, , of . Of this area, or 46.9% is used ...

VD on Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

in 1957 and built a holiday home on it. In autumn 1963, however, the parliament of the canton of Vaud

Vaud ( ; french: (Canton de) Vaud, ; german: (Kanton) Waadt, or ), more formally the canton of Vaud, is one of the 26 cantons forming the Swiss Confederation. It is composed of ten districts and its capital city is Lausanne. Its coat of arms ...

declared him an unwanted foreigner and denied him a residence permit. In 1964, he undertook to "sever all spatial and future connections with Switzerland". The Swiss Federal President Ludwig von Moos said before the National Council that "in view of this declaration" the government had "refrained from issuing an entry ban".Globke was buried in the central cemetery in Bad Godesberg

Bad Godesberg ( ksh, Bad Jodesbersch) is a borough ('' Stadtbezirk'') of Bonn, southern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. From 1949 to 1999, while Bonn was the capital of West Germany, most foreign embassies were in Bad Godesberg. Some buildings ...

in the district of Plittersdorf.

Death

Globke died after a serious illness at his home on 13 February 1973. He was buried in the central cemetery of Bad Godesberg in Plittersdorf inBonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

.

Scholarly investigation

Bertelsmann

In 1961 the civil activist wrote, ''Hans Globke – File Extracts, documents based on Strecker's research in Polish and Czech archives'', which was published by theBertelsmann

Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA () is a German private multinational conglomerate corporation based in Gütersloh, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is one of the world's largest media conglomerates, and is also active in the service sector and ...

affiliate Rütten & Loening. The book consisted of a collection of legal files, images and newspaper reports that had been colleted by Strecker from Nazi archives. The collection proved that Globke had helped to draft several anti-semitic laws during the early 1930's, years before Adolf Hitler had come to power had later become one of Eichmann's most important functionaries. Eichmann was given the book by his lawyer Robert Servatius and had written 40 pages of commentaries on 15 December 1961 that detailed his relationship to himself and tried to prove that Globke had more authority than he did.

The naming of Globke by Eichmann was highly undesirable for the West German Government. Globke attempted to block further publication of the book in court with an interim injunction

The term interim order refers to an order issued by a court during the pendency of the litigation. It is generally issued by the Court to ensure Status quo. The rationale for such orders to be issued by the Courts is best explained by the Latin l ...

. The BND, under the leadership of Gehlen, spent 50,000 marks trying to take the book off the market. When a court then discovered two minor mistakes (the publisher had caused one of them by abbreviation), it imposed a restraining order and Bertelsmann came to the decision to cancel the new edition of the book. The government is thought by historians to have threatened Bertelsmann by informing them that no official agency would have acquired any book from the publisher again.

Adolf Eichmann

In June 2006, it was announced that the Adenauer Government had informed the CIA of the location ofAdolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

'' Timothy Naftali Timothy Naftali is a Canadian-American historian who is clinical associate professor of public service at New York University. He has written four books, two of them co-authored with Alexander Fursenko on the Cuban Missile Crisis and Nikita Khrush ...

, through contacts at the highest level, it had also ensured that the CIA did not use that knowledge. Neither the federal government nor the CIA passed the new information on to the '' Timothy Naftali Timothy Naftali is a Canadian-American historian who is clinical associate professor of public service at New York University. He has written four books, two of them co-authored with Alexander Fursenko on the Cuban Missile Crisis and Nikita Khrush ...

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

i government. Naftali suggested that Adenauer had wanted to prevent pressure on Globke regarding Eichmann. When Eichmann was captured and taken to be tried in Isreal, Adenauer sent the German-Jewish journalist Rolf Vogel as an emissary, to influence the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, in the one of the most sensitive diplomatic and intelligence operations of West Germany. The fact that Vogel was specially commissioned into the BND provides an indication of the sensitivity of the operation. Vogel met with David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the nam ...

to present a letter from Adenauer. Ben-Gurion informed Vogel that of the hundred names that Eichmann was queried on, Globke's was not mentioned.. Vogel immediately returned to Germany and contacted Adenauer to confirm that Globke was in the clear.

Eichmann had previously given extensive interviews on his life to Dutch journalist and former SS agent Willem Sassen

Wilhelmus Antonius Sassen (born 16 April 1918 – died 2002) was a Dutch collaborator, Nazi journalist and a member of the ''Waffen-SS''. He became known around 1960 as "the interviewer of Adolf Eichmann".

Biography

Willem Sassen was born in ...

, on which his memoirs were to be based. Since 1957, Sassen's attempts to sell this material to US magazine ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy ...

'' had been unsuccessful. This changed with the spectacular kidnapping of Eichmann by Mossad

Mossad ( , ), ; ar, الموساد, al-Mōsād, ; , short for ( he, המוסד למודיעין ולתפקידים מיוחדים, links=no), meaning 'Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations'. is the national intelligence agency ...

in May 1960, made possible by an unofficial tip-off by the Hessian Attorney General Fritz Bauer

Fritz Bauer (16 July 1903 – 1 July 1968) was a German Jewish judge and prosecutor. He was instrumental in the post-war capture of former Holocaust planner Adolf Eichmann and played an essential role in beginning the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials ...

, and the preparation of the Eichmann trial in Israel. ''Life'' published extracts from Sassen's material about Eichmann in two articles, on 28 November and 5 December 1960. His family wanted to use the royalties from the articles to fund his defence in court. However the federal government, already worried about the campaign in East Berlin, contacted the CIA to ensure that any material regarding Globke was removed from the ''Life'' coverage. In an internal memo dated 20 September 1960, CIA chief Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles (, ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was the first civilian Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and its longest-serving director to date. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the early Cold War, he ov ...

mentioned "a vague mention of Globke, which Life omits at our demand".

Globke's estate

In 2009, the historian Erik Lommatzsch wrote a monograph detailing his investigation of the Globke's estate in the archive of theKonrad Adenauer Foundation

The Konrad Adenauer Foundation (german: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, KAS) is a German political party foundation associated with but independent of the centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU). The foundation's headquarters are located in Sank ...

. However, Globke's actual relationship to Nazism and his influence on the government of Adenauer are not really clarified, which, according to reviewer Hans-Heinrich Jansen, "in view of the sourcing, which for many central issues, turned out to be slim, after all" is not conclusively possible. The background of the Stasi

The Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the (),An abbreviation of . was the state security service of the East Germany from 1950 to 1990.

The Stasi's function was similar to the KGB, serving as a means of maintaining state autho ...

campaign against Globke remains largely unknown; however, this aspect of Lommatzsch's biography was in any case only intended as a digression, since it requires separate treatment. However, Lommatzsch mentions a number of examples of Globke campaigning for the persecuted, his commentary on the Nuremberg Laws was aimed at defusing the regulations, and he had not played the dominant role in the postwar period the Adenauer opponents had assumed.

Research into Gehlen organisation

In 2011, the German historian began research into the Federal Intelligence Service archives, the successor organisation to ''The Org'', and concluded that Gehlen, under the cloak of anti-communist activities, had been supplying Globke with briefings on a wide range of domestic German targets. Henke discovered that Gehlen methodically collected intelligence on senior members of theSocial Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

(SPD), the Fourth Estate, other intelligence agencies, Nazi victims associations and members of the nobility and the church. In the early years of the German Federal Republic

BRD (german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland ; English: FRG/Federal Republic of Germany) is an unofficial abbreviation for the Federal Republic of Germany, informally known in English as West Germany until 1990, and just Germany since reunification. I ...

, it was important for Adenauer and Globke to be fully aware of the activities of the opposition. Globke and Gehlen met daily and developed a successful symbiotic relationship, that ensured Adenauer remained in power. According to Henke, the organisation "was able to work, in effect, fully under the radar. And in effect, it was an instrument for keeping a stranglehold on power and a personal tool for Globke". Globke and Gehlen used the organisation's network to have unfriendly journalists removed from their posts, place propaganda in more friendly newspapers, and acquire information that could be used against Globke and Adenauer's rivals. In 1960, the organisation provided a briefing to Globke on the SPD politician and future Chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt (; born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992) was a German politician and statesman who was leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1964 to 1987 and served as the chancellor of West Ger ...

that stated:

:"This pig has things on his record from his time in the safety of western exile and with the Red Orchestra that could bring him down at any point of our choosing. We've got the material, but we have time, too."

Complicit in the system

The historianWolfgang Benz

Wolfgang Benz (born 9 June 1941) is a German historian from Ellwangen. He was the director of the Center for Research on Antisemitism of the Technische Universität Berlin between 1990 and 2011.

Personal life

Benz studied history, political ...

judges that Globke was "not a National Socialist and not an anti-Semite", but "functioned in the interests of the Nazi regime and made himself complicit in the system of persecution of the Jews through competent participation".

Awards and honours

Before 1945

* Honor Cross for Front Fighters (1934) * Medal commemorating the 13th of March 1938 (1938) *Sudetenland Medal

The 1 October 1938 Commemorative Medal (german: Die Medaille zur Erinnerung an den 1. Oktober 1938), commonly known as the Sudetenland Medal was a decoration of Nazi Germany awarded during the interwar period, and the second in a series of Occupa ...

(1939)

* Silver Loyalty Merit Sign (1941)

* War Merit Cross 2nd Class (1942)

* Commander's Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania (1942)

After 1945

* Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria, Grand Decoration of Honour in Gold with Sash for Services to the Republic of Austria (1956) * Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (1956) * Order of the Oak Crown, Grand Cross of the Order of the Oak Crown of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (1957) * Order of Christ (Portugal), Grand Cross of the Order of Christ of Portugal (1960) * Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1963)Works

* *See also

* Theodor Oberländer * Rudolf von GersdorffBibliography

* * * LCN 61-7240.Publications

* *References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Globke, Hans 1898 births 1973 deaths Politicians from Düsseldorf People from the Rhine Province German Roman Catholics Centre Party (Germany) politicians German activists Jurists from North Rhine-Westphalia Lawyers in the Nazi Party Cartellverband members University of Bonn alumni University of Cologne alumni German Army personnel of World War I Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Recipients of the Grand Decoration with Sash for Services to the Republic of Austria Commanders of the Order of the Star of Romania Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic Grand Crosses of the Order of Christ (Portugal) Officials of Nazi Germany Heads of the German Chancellery People convicted in absentia