HMS Barham (04) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Barham'' was one of five s built for the

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts, 6

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts, 6

Following Jutland, ''Barham'' was under repair until 5 July 1916.Preston, p. 34 On the evening of 18 August, the Grand Fleet put to sea in response to a message deciphered by Room 40 that indicated that the High Seas Fleet, minus II Squadron, would be leaving harbour that night. The German objective was to bombard

Following Jutland, ''Barham'' was under repair until 5 July 1916.Preston, p. 34 On the evening of 18 August, the Grand Fleet put to sea in response to a message deciphered by Room 40 that indicated that the High Seas Fleet, minus II Squadron, would be leaving harbour that night. The German objective was to bombard

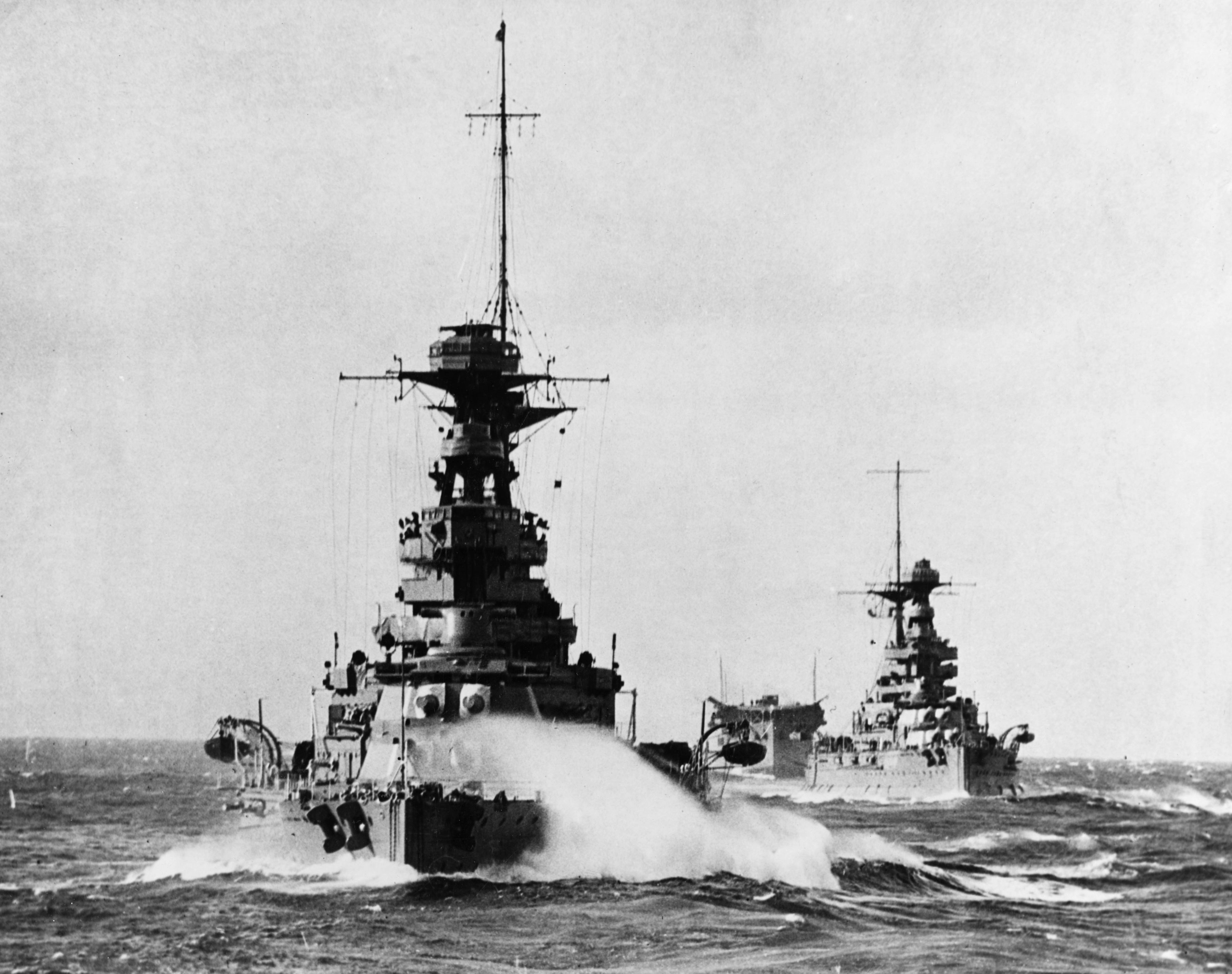

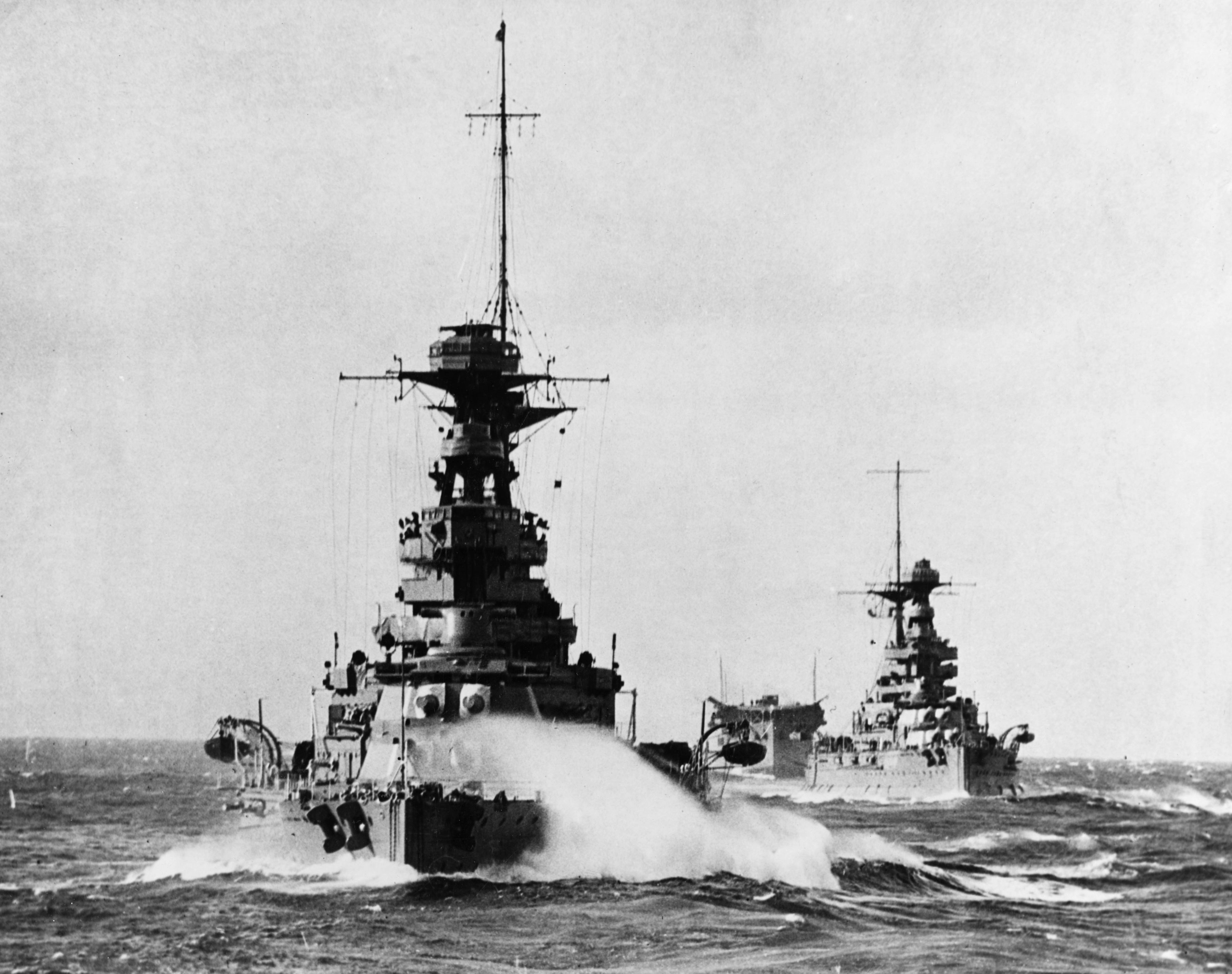

''Barham'' became flagship of the 1st Battle Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet in April 1919, and made a port visit to

''Barham'' became flagship of the 1st Battle Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet in April 1919, and made a port visit to

Captain Geoffrey Cooke assumed command on 25 March and the Navy took the opportunity to augment her light anti-aircraft armament and upgrade its directors. ''Barham'' played no role in the Norwegian Campaign although some of her crew and

Captain Geoffrey Cooke assumed command on 25 March and the Navy took the opportunity to augment her light anti-aircraft armament and upgrade its directors. ''Barham'' played no role in the Norwegian Campaign although some of her crew and

On 3 January 1941, the ship, together with ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'', bombarded

On 3 January 1941, the ship, together with ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'', bombarded

On the afternoon of 24 November 1941, the 1st Battle Squadron, ''Barham'', ''Queen Elizabeth'', and ''Valiant'', with an escort of eight destroyers, departed Alexandria to cover the 7th and 15th Cruiser Squadrons as they hunted for Italian convoys in the Central Mediterranean. The following morning, the , commanded by ''

On the afternoon of 24 November 1941, the 1st Battle Squadron, ''Barham'', ''Queen Elizabeth'', and ''Valiant'', with an escort of eight destroyers, departed Alexandria to cover the 7th and 15th Cruiser Squadrons as they hunted for Italian convoys in the Central Mediterranean. The following morning, the , commanded by ''

www.hmsbarham.com – Site of HMS ''Barham'' Association

* ttp://www.maritimequest.com/warship_directory/great_britain/battleships/barham/hms_barham.htm Maritimequest HMS ''Barham'' Photo Gallery

Captain Terry Herrick

– ''Daily Telegraph'' obituary

HMS Barham Explodes & Sinks: World War II (1941)

- archive footage captured by British Pathé News cameraman, John Turner {{DEFAULTSORT:Barham (1914) Queen Elizabeth-class battleships Ships built on the River Clyde 1914 ships World War I battleships of the United Kingdom World War II battleships of the United Kingdom Ships sunk by German submarines in World War II World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea Maritime incidents in Egypt Maritime incidents in December 1939 Maritime incidents in November 1941 Filmed killings Naval magazine explosions

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

during the early 1910s. Completed in 1915, she was often used as a flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

and participated in the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice ...

during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

as part of the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

. For the rest of the war, except for the inconclusive action of 19 August 1916

The action of 19 August 1916 was one of two attempts in 1916 by the German High Seas Fleet to engage elements of the British Grand Fleet, following the mixed results of the Battle of Jutland, during the First World War. The lesson of Jutland f ...

, her service generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the ship was assigned to the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

, and Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the Firs ...

s. ''Barham'' played a minor role in quelling the 1929 Palestine riots

The 1929 Palestine riots, Buraq Uprising ( ar, ثورة البراق, ) or the Events of 1929 ( he, מאורעות תרפ"ט, , ''lit.'' Events of 5689 Anno Mundi), was a series of demonstrations and riots in late August 1929 in which a longst ...

and the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, later known as The Great Revolt (''al-Thawra al- Kubra'') or The Great Palestinian Revolt (''Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra''), was a popular nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine a ...

. The ship was in the Mediterranean when the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

began in September 1939, on her voyage home three months later, she accidentally collided with and sank one of her escorting destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

s, .

She participated in the Battle of Dakar

The Battle of Dakar, also known as Operation Menace, was an unsuccessful attempt in September 1940 by the Allies to capture the strategic port of Dakar in French West Africa (modern-day Senegal). It was hoped that the success of the operation cou ...

in mid-1940, where she damaged a Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

battleship and was slightly damaged in return. ''Barham'' was then transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet, where she covered multiple Malta convoys

The Malta convoys were Allied supply convoys of the Second World War. The convoys took place during the Siege of Malta in the Mediterranean Theatre. Malta was a base from which British sea and air forces could attack ships carrying supplies ...

. She helped to sink an Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval T ...

and a destroyer during the Battle of Cape Matapan

The Battle of Cape Matapan ( el, Ναυμαχία του Ταινάρου) was a naval battle during the Second World War between the Allies, represented by the navies of the United Kingdom and Australia, and the Royal Italian navy, from 27 t ...

in March 1941 and was damaged by German aircraft two months later during the evacuation of Crete. ''Barham'' was sunk off the Egyptian coast the following November by the with the loss of 862 crewmen, approximately two thirds of her crew.

Design and description

The ''Queen Elizabeth''-class ships were designed to form a fast squadron for the fleet that was intended to operate against the leading ships of the opposingbattleline

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

. This required maximum offensive power and a speed several knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot may also refer to:

Places

* Knot, Nancowry, a village in India

Archaeology

* Knot of Isis (tyet), symbol of welfare/life.

* Minoan snake goddess figurines#Sacral knot

Arts, entertainme ...

faster than any other battleship to allow them to defeat any type of ship.

''Barham'' had a length overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and ...

of , a beam of and a deep draught of . She had a normal displacement of and displaced at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into we ...

. She was powered by two sets of Brown-Curtis steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam tu ...

s, each driving two shafts using steam from 24 Yarrow boiler

Yarrow boilers are an important class of high-pressure water-tube boilers. They were developed by

Yarrow & Co. (London), Shipbuilders and Engineers and were widely used on ships, particularly warships.

The Yarrow boiler design is characteristic ...

s. The turbines were rated at and intended to reach a maximum speed of . During her abbreviated sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s on 6 July 1916, ''Barham'' only reached a mean top speed of . The ship had a range of at a cruising speed of . Her crew numbered 1,016 officers and ratings in 1916.

Armament and fire-control

The ''Queen Elizabeth'' class was equipped with eightbreech-loading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition (cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally breech ...

(BL) Mk I guns in four twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s, in two superfiring pairs fore and aft of the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

, designated 'A', 'B', 'X', and 'Y' from front to rear. Twelve of the fourteen BL Mk XII guns were mounted in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" me ...

s along the broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

of the vessel amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17t ...

; the remaining pair were mounted on the forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " ...

deck near the aft funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construct ...

and were protected by gun shield

A U.S. Marine manning an M240 machine gun equipped with a gun shield

A gun shield is a flat (or sometimes curved) piece of armor designed to be mounted on a crew-served weapon such as a machine gun, automatic grenade launcher, or artillery pi ...

s. The anti-aircraft (AA) armament were composed of two quick-firing (QF) 20 cwt Mk I"Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight

The hundredweight (abbreviation: cwt), formerly also known as the centum weight or quintal, is a British imperial and US customary unit of weight or mass. Its value differs between the US and British imperial systems. The two values are disti ...

, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun. guns. The ships were fitted with four submerged 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, two on each broadside.

''Barham'' was completed with two fire-control directors fitted with rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

s. One was mounted above the conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

, protected by an armoured hood, and the other was in the spotting top above the tripod mast

The tripod mast is a type of mast used on warships from the Edwardian era onwards, replacing the pole mast. Tripod masts are distinctive using two large (usually cylindrical) support columns spread out at angles to brace another (usually vertical ...

. Each turret was also fitted with a 15-foot rangefinder. The main armament could be controlled by 'B' turret as well. The secondary armament was primarily controlled by directors mounted on each side of the compass platform on the foremast once they were fitted in July 1917.

Protection and aircraft

The waterline belt of the ''Queen Elizabeth'' class consisted ofKrupp cemented armour

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the ...

(KC) that was thick over the ships' vitals. The gun turrets were protected by of KC armour and were supported by barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s thick. The ships had multiple armoured decks that ranged from in thickness. The main conning tower was protected by of armour. After the Battle of Jutland, of high-tensile steel was added to the main deck over the magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and additional anti-flash equipment was added in the magazines.

The ship was fitted with flying-off platforms mounted on the roofs of 'B' and 'X' turrets in 1918, from which fighters and reconnaissance aircraft

A reconnaissance aircraft (colloquially, a spy plane) is a military aircraft designed or adapted to perform aerial reconnaissance with roles including collection of imagery intelligence (including using photography), signals intelligence, as ...

could launch. During her early-1930s refit, the platforms were removed from the turrets and a retractable catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stor ...

was installed on the roof of 'X' turret, along with a crane to recover a floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, m ...

. This was initially a Fairey III

The Fairey Aviation Company Fairey III was a family of British reconnaissance biplanes that enjoyed a very long production and service history in both landplane and seaplane variants. First flying on 14 September 1917, examples were still in u ...

F until it was replaced by a Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also us ...

in 1938.

Major alterations

''Barham'' received a series of minor refits during the 1920s. In 1921–1922, rangefinders replaced the smaller ones in 'B' and 'X' turrets. Two years later, her anti-aircraft defences were upgraded when the original three-inch AA guns were replaced with a pair of QF Mk V AA guns between November 1924 and January 1925 and another pair of four-inch AA guns were added from October to November later that year. To control these guns a temporary High-Angle Control Position was mounted above the torpedo-control tower aft. This was replaced by a torpedo rangefinder in early 1928 when the permanent position was installed in the remodelled spotting top. The ship was extensively refitted between January 1931 and January 1934 at a cost of £424,000. During this refit, the aft superstructure was rebuilt and the torpedo-control tower and its rangefinder were removed, together with the aft set of torpedo tubes. The fore funnel was trunked into the aft funnel to reduce smoke in the spotting top. A High-Angle Control System (HACS) Mk I director were added to the roof of the spotting top and themainmast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation lig ...

was reconstructed as a tripod to support the weight of a second HACS director. A pair of octuple mounts for 2-pounder () Mk VIII "pom-pom" anti-aircraft guns were added abreast the funnel and two positions for their directors were added on new platforms abreast and below the spotting top. In addition, a pair of quadruple mounts for Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 1 ...

AA machine guns were added abreast the conning tower.

The turret roofs were reinforced to a thickness of and the armour added over the magazines after Jutland was replaced by 4 inches of Krupp non-cemented armour, the first British battleship to receive such. In addition, the rear of the six-inch gun casemates was enclosed by a bulkhead. Underwater protection was improved by the addition of torpedo bulge

The anti-torpedo bulge (also known as an anti-torpedo blister) is a form of defence against naval torpedoes occasionally employed in warship construction in the period between the First and Second World Wars. It involved fitting (or retrofittin ...

s. They were designed to reduce the effect of torpedo detonations and improve stability at the cost of widening the ship's beam by almost to ,Campbell 1980, p. 7 and reduced her draught to . This increased her metacentric height to about at deep load, despite the increase in her deep displacement to . When ''Barham'' conducted her sea trials on 20 November 1933, her speed was reduced to from .

Later alterations included replacing the single mounts of the AA guns with twin mounts for the QF 4-inch Mark XVI gun, removal of the forward submerged torpedo tubes and the high-angle rangefinder in March–May 1938. In addition the torpedo-control tower aft was replaced by an air-defence position during that same refit. While under repair in December 1939March 1940, a 20-barrel Unrotated projectile (UP) rocket launcher was installed on the roof of 'B' turret and her HACS Mk I directors were replaced with Mk III models. The following year the UP mount was replaced by a pair of quadruple Vickers 0.5-inch machine gun mounts and another pair of eight-barreled "pom-pom" mounts were added abreast her conning tower.

Construction and career

The ''Queen Elizabeth'' class was ordered as part of the 1912 Naval Programme and the contract for ''Barham'' was awarded toJohn Brown & Company

John Brown and Company of Clydebank was a Scottish marine engineering and shipbuilding firm. It built many notable and world-famous ships including , , , , , and the ''Queen Elizabeth 2''.

At its height, from 1900 to the 1950s, it was one of ...

.Preston, p. 33 The ship, named after Admiral Charles Middleton, 1st Baron Barham

Admiral Charles Middleton, 1st Baron Barham, PC (14 October 172617 June 1813) was a Royal Navy officer and politician. As a junior officer he saw action during the Seven Years' War. Middleton was given command of a guardship at the Nore, a Roy ...

,Silverstone, p. 216 was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at their Clydebank

Clydebank ( gd, Bruach Chluaidh) is a town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland. Situated on the north bank of the River Clyde, it borders the village of Old Kilpatrick (with Bowling and Milton beyond) to the west, and the Yoker and Drumchapel ...

shipyard on 24 February 1913 and launched on 31 December 1914. ''Barham'' cost a total of £2,470,113. She was completed for trials on 19 August 1915 which took until the end of September to finish under the command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Arthur Craig Waller. The following day, 1 October, Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Hugh Evan-Thomas, commander of the 5th Battle Squadron

The 5th Battle Squadron was a squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of battleships. The 5th Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Second Fleet. During the First World War, the Home Fleet was renamed the Grand Fleet.

His ...

, hoisted his flag aboard his new flagship.

First World War

''Barham'' joined theGrand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay a ...

the next day and participated in a fleet training operation west of Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

during 2–5 November. During another training exercise in early December, the ship was accidentally rammed by her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

on 3 December. After temporary repairs at Scapa, ''Barham'' was sent to Cromarty Firth

The Cromarty Firth (; gd, Caolas Chrombaidh ; literally "kyles /nowiki>straits.html"_;"title="strait.html"_;"title="/nowiki>strait">/nowiki>straits">strait.html"_;"title="/nowiki>strait">/nowiki>straitsof_Cromarty.html" ;"title="strait">/no ...

for more permanent repairs in the floating dry dock

Floating may refer to:

* a type of dental work performed on horse teeth

* use of an isolation tank

* the guitar-playing technique where chords are sustained rather than scratched

* ''Floating'' (play), by Hugh Hughes

* Floating (psychological p ...

there that lasted until 23 December.

The Grand Fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February 1916; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, a ...

to sweep the Heligoland Bight

The Heligoland Bight, also known as Helgoland Bight, (german: Helgoländer Bucht) is a bay which forms the southern part of the German Bight, itself a bay of the North Sea, located at the mouth of the Elbe river. The Heligoland Bight extends f ...

, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea. Another sweep began on 6 March, but had to be abandoned the following day as the weather grew too severe for the escorting destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

s. On the night of 25 March, ''Barham'' and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support Beatty's battlecruisers and other light forces raiding the German Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a strong gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface winds moving at a speed of between 34 and 47 knots (, or ).Horns Reef

Horns Rev is a shallow sandy reef of glacial deposits in the eastern North Sea, about off the westernmost point of Denmark, Blåvands Huk.

to distract the Germans while the Russian Navy relaid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

. The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft. The 5th Battle Squadron preceded the rest of the Grand Fleet to reinforce Vice-Admiral David Beatty's battlecruiser fleet, but the British arrived in the area after the Germans had withdrawn. On 2–4 May, the fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea. On 21 May, the 5th Battle Squadron was attached to Beatty while his 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron

The 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron was a short-lived Royal Navy squadron of battlecruisers that saw service as part of the Grand Fleet during the First World War.

Creation

The 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron was created in 1915, with the return to home ...

was detached for gunnery training and arrived at Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

the following day.

Battle of Jutland

light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

s, and 31 torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s, departed the Jade

Jade is a mineral used as jewellery or for ornaments. It is typically green, although may be yellow or white. Jade can refer to either of two different silicate minerals: nephrite (a silicate of calcium and magnesium in the amphibole group ...

early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers and supporting cruisers and torpedo boats. The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet. ''Barham'' slipped her mooring

A mooring is any permanent structure to which a vessel may be secured. Examples include quays, wharfs, jetties, piers, anchor buoys, and mooring buoys. A ship is secured to a mooring to forestall free movement of the ship on the water. An ''an ...

at 22:08 and was followed by the rest of Beatty's ships.The times used in this section are in UT, one hour behind CET, which is often used in German works.

When dawn broke Beatty ordered his forces into cruising formation with the 5th Battle Squadron trailing his battle cruisers by . At 14:15, Beatty ordered a turn north by east

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each ...

to rendezvous with the Grand Fleet. Shortly before the turn, one of his escorting light cruisers, spotted smoke on the horizon and continued on her course to investigate. Ten minutes later, the ship radioed "Two cruisers, probably hostile, in sight..." They were actually two German destroyers that had stopped to check a Danish merchant ship's papers. At 14:32, Beatty ordered a course change to south-southeast in response to the spot report. ''Barham''s signallers were unable to read the signal and her officer of the watch

Watchkeeping or watchstanding is the assignment of sailors to specific roles on a ship to operate it continuously. These assignments, also known at sea as ''watches'', are constantly active as they are considered essential to the safe operation o ...

presumed that it was the expected point zigzag

A zigzag is a pattern made up of small corners at variable angles, though constant within the zigzag, tracing a path between two parallel lines; it can be described as both jagged and fairly regular.

In geometry, this pattern is described as ...

to the left of the base course and signalled that course change to the rest of the squadron. After several minutes it became apparent that the squadron was not conforming to Beatty's other ships, but Evan-Thomas refused to change course until clear instructions had been received despite entreaties from the ''Barham''s captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

. While the exact time when Evan-Thomas ordered his ships to turn to follow Beatty is not known, the consensus is that it was about seven minutes later, which increased his distance from Beatty to nothing less than .

Hipper's battlecruisers spotted the Battlecruiser Fleet to their west at 15:20, but Beatty's ships did not see the Germans to their east until 15:30. Two minutes later, Beatty ordered a course change to east-southeast, positioning the British ships to cut off the German's line of retreat, and signalled action stations

General quarters, battle stations, or action stations is an announcement made aboard a naval warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the arme ...

. Hipper ordered his ships to turn to starboard, away from the British, to assume a south-easterly course, and reduced speed to to allow three light cruisers of the 2nd Scouting Group to catch up. With this turn, Hipper was falling back on the High Seas Fleet, behind him. Beatty then altered course to the east, as he was still too far north to cut Hipper off. This was later characterised as the "Run to the South" as Beatty changed course to steer east-southeast at 15:45, now paralleling Hipper's course less than away. By this time the 5th Battle Squadron was about northwest of Beatty. The Germans opened fire first at 15:48, followed by the British battlecruisers.

The light cruisers of the 2nd Scouting Group were the first German ships visible to Evan-Thomas's ships and ''Barham'' opened fire on them at 15:58 until the cruisers disappeared into their own smoke screen

A smoke screen is smoke released to mask the movement or location of military units such as infantry, tanks, aircraft, or ships.

Smoke screens are commonly deployed either by a canister (such as a grenade) or generated by a vehicle (such as ...

at around 16:05. About three minutes later, the ship opened fire on the battlecruiser at a range of about . A minute later she scored one hit on the German ship's stern before she was ordered to switch targets to the battlecruiser , together with her sister . The shell struck just below the waterline and burst on impact with the belt armour. The impact was right on the joints between several armour plates and drove them inwards and destroyed part of the hull behind them. The damage allowed over of water to flood the stern and nearly knocked out the ship's steering gear. Between them, ''Barham'' and ''Valiant'' hit ''Moltke'' four times from 16:16 to 16:26, but only one of those hits can be attributed to ''Valiant''. Two of the others detonated upon striking the waterline armour, but failed to penetrate. The impacts drove in the plates and fragments caused much flooding by damaging the surrounding structure. The last shell passed all the way through the ship without detonating; it struck and dislodged a armour plate on the waterline on the other side of the ship that caused also some flooding. ''Barham'' was herself was struck twice during the "Run to the South": the first was a shell from ''von der Tann'' that failed to do any damage when it hit the waterline armour and the battlecruiser fired a shell that detonated in the aft superstructure. This sent splinters in every direction and started a small fire, but otherwise did no significant damage.

At 16:30, the light cruiser , scouting in front of Beatty's ships, spotted the lead elements of the High Seas Fleet coming north at top speed. Three minutes later, she sighted the topmasts of Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer's battleships, but did not report this for another five minutes. Beatty continued south for another two minutes to confirm the sighting before ordering his force to turn north, towards the Grand Fleet in what came to be known as the "Run to the North". His order only applied to his own forces; the 5th Battle Squadron continued south until after it passed Beatty heading northwestwards at 16:51. Beatty then ordered Evan-Thomas to turn his ships in succession to follow the battlecruisers three minutes later. This meant that they were some closer to the rapidly advancing High Sea Fleet. And now within range of the battleships of the 3rd Squadron which opened fire on the 5th Battle Squadron as they made their turn.

Evan-Thomas continued his turn until his ships were steering due north, which interposed the 5th Battle Squadron between Hipper's battlecruisers, which had reversed course around 16:48 to follow Beatty north, and Beatty's ships. While making the turn, ''Barham'' was struck by two 30.5-centimetre shells beginning at 16:58, probably from the battlecruiser . The first of these struck the ship's upper deck before detonating upon striking the main deck above the medical store compartment, which was completely burnt out. The detonation blew a hole in the main deck, sent fragments through the middle and lower decks and burned out the casemate for starboard No. 2 six-inch gun. Three minutes later another shell hit the aft superstructure, severing the antenna cables of the main wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

station. One fragment ricocheted off the upper deck and through the side plating on the opposite side of the ship. Either the first or the fourth of these shells destroyed the ship's sickbay, killing the staff and all of its patients, including eight ship's boys. ''Barham'' returned fire at the battlecruisers at 17:02, together with ''Valiant'', the two northernmost of Evan-Thomas's ships, and the two of them made three hits on the battlecruiser and ''Lützow'' between 17:06 and 17:13 while ''Barham'' was hit twice more by ''Derfflinger''; although neither of the hits did any significant damage. In contrast, the hit on ''Lützow'' flooded a magazine and the hits on ''Seydlitz'' blew a hole in the side of her bow. Fragments from this hit caused flooding that spread throughout the bow, while the ship's speed caused water to enter directly through the hole in the side. Other fragments from the second hit caused damage that allowed the water to spread even further. These two hits were ultimately responsible for the massive flooding that nearly sank the ship after the battle. The third shell detonated on the face of the starboard wing turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanism ...

, although some fragments entered the turret and caused minor damage.

Beatty in the meantime had turned further west to open up the range between his battered battlecruisers and the Germans. At 17:45 he turned eastwards to take his position in front of the Grand Fleet and re-engage Hipper's ships. This meant that the 5th Battle Squadron and the light cruisers were the sole targets available for the German ships until after his turn, although the worsening visibility hampered both sides' shooting. ''Barham'' was not hit during this time and she and ''Valiant'', later joined by their sister ''Warspite'', continued to fire at Hipper's 1st Scouting Group until 18:02 when ''Valiant'' lost sight of the Germans. They hit ''Lützow'', ''Derfflinger'' and ''Seydlitz'' three times each between 17:19 and about 18:05. ''Lützow'' was only slightly damaged by these hits, which essentially only knocked out the primary and back-up wireless rooms while the shells that hit ''Derfflinger'' hit the side of the ship's bow, knocking off several armour plates, while fragments opened holes that ultimately allowed roughly of water to enter the bow. One of these hits also started several major fires inside the hull. The hits on ''Seydlitz'' mostly opened up more holes that facilitated the flooding.

Hipper turned his ships southward around 18:05 to fall back upon Scheer's advancing battleships and then reversed course five minutes later. Evan-Thomas turned northeast at around 18:06 and then made a slow turn to the southeast once he spotted the Grand Fleet. He first spotted the battleship , flagship of the 6th Division of the 1st Battle Squadron

The 1st Battle Squadron was a naval squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of battleships. The 1st Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet. After World War I the Grand Fleet was reverted to its original name, ...

and thought she was leading the Grand Fleet as it deployed from cruising formation into line ahead. At 18:17 he realised that ''Marlborough'' was actually at the rear of the formation and he ordered a turn to the north to bring his squadron into line behind the Grand Fleet. This took some time and his ships had to slow down to to avoid overrunning the 6th Division and blocking its fire. The 5th Battle Squadron concentrated their fire on the German battleships after losing sight of the battlecruisers, with ''Barham'' opening fire at 18:14. No hits were observed and the ships stopped firing after making their turn north, but ''Barham'' opened fire for a short time when they fell in line with the Grand Fleet a few minutes later, probably without making any hits.

''Barham'' fired 337 fifteen-inch shells and 25 six-inch shells during the battle. The number of hits cannot be confirmed, but it is believed that she and ''Valiant'' made 23 or 24 hits between them, making them two of the most accurate warships in the British fleet. She was hit six times during the battle, five times by 30.5 cm shells and once by a 28.3 cm shell, suffering casualties of 26 killed and 46 wounded.

Subsequent activity

Following Jutland, ''Barham'' was under repair until 5 July 1916.Preston, p. 34 On the evening of 18 August, the Grand Fleet put to sea in response to a message deciphered by Room 40 that indicated that the High Seas Fleet, minus II Squadron, would be leaving harbour that night. The German objective was to bombard

Following Jutland, ''Barham'' was under repair until 5 July 1916.Preston, p. 34 On the evening of 18 August, the Grand Fleet put to sea in response to a message deciphered by Room 40 that indicated that the High Seas Fleet, minus II Squadron, would be leaving harbour that night. The German objective was to bombard Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port city in Tyne and Wear, England. It is the City of Sunderland's administrative centre and in the Historic counties of England, historic county of County of Durham, Durham. The city is from Newcastle-upon-Tyne and is on t ...

on 19 August, based on extensive reconnaissance conducted by Zeppelins and submarines. The Grand Fleet sailed with 29 dreadnoughts and 6 battlecruisers while the Germans mustered 18 dreadnoughts and 2 battlecruisers. Throughout the next day, Jellicoe and Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, commander of the High Seas Fleet, received conflicting intelligence; after reaching the location in the North Sea where they expected to encounter the High Seas Fleet, the British turned north in the erroneous belief that they had entered a minefield. Scheer turned south again, then steered south-eastward to pursue a lone British battle squadron sighted by an airship, which was in fact the Harwich Force of cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several ...

s and destroyers under Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

Reginald Tyrwhitt

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Reginald Yorke Tyrwhitt, 1st Baronet, (; 10 May 1870 – 30 May 1951) was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he served as commander of the Harwich Force. He led a supporting naval force of 31 destroyers a ...

. Realising their mistake, the Germans changed course for home. The only contact came in the evening when Tyrwhitt sighted the High Seas Fleet but was unable to achieve an advantageous attack position before dark, and broke off contact. The British and the German fleets returned home; the British lost two cruisers to submarine attacks, and one German dreadnought had been torpedoed. After returning to port, Jellicoe issued an order that prohibited risking the fleet in the southern half of the North Sea due to the overwhelming risk from mines and U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s unless the odds of defeating the High Seas Fleet in a decisive engagement were favourable.

She was refitted at Cromarty

Cromarty (; gd, Cromba, ) is a town, civil parish and former royal burgh in Ross and Cromarty, in the Highland area of Scotland. Situated at the tip of the Black Isle on the southern shore of the mouth of Cromarty Firth, it is seaward from ...

between February and March 1917 and King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother ...

inspected the ship on 22 June at Invergordon. ''Barham'' was refitted at Rosyth from 7–23 February 1918 and Waller was relieved by Captain Henry Buller

Admiral Sir Henry Tritton Buller, (30 October 1873 – 29 August 1960) was a Royal Navy officer, who commanded the Royal Yacht from 1921 to 1931. He served as an Extra Equerry to King George V, and, from 1932 till his death, he was a Groom-in-Wa ...

on 18 April. The latter was succeeded by Captain Richard Horne on 1 October. She was present when the High Seas Fleet surrendered for internment on 21 November.

Between the wars

''Barham'' became flagship of the 1st Battle Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet in April 1919, and made a port visit to

''Barham'' became flagship of the 1st Battle Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet in April 1919, and made a port visit to Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

, France that month together with the rest of the squadron. Captain Robin Dalglish relieved Horne on 1 October 1920.Jones, p. 265 She retained her position when the 1st and 2nd Battle Squadrons were merged in May 1921. Dalglish was relieved in his turn by Captain Percy Noble on 18 October 1922. ''Barham'' participated in the Fleet review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

on 26 July 1924 at Spithead. A few months later, now under the command of Captain Richard Hill, the ship again retained her position as the 1st Battle Squadron was split in two and the ''Queen Elizabeth''s of the new 1st Battle Squadron were transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

on 1 November 1924. On 14 October 1925, Captain Francis Marten

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

*Rural Mu ...

relieved Hill, but he retained command only until 9 March 1926 when Captain Joseph Henley assumed command. Together with her sister , ''Barham'' was sent to Alexandria, Egypt

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, in May 1927 during a time of unrest. Now under the command of Captain Hubert Monroe and accompanied by the battleship , she cruised along the coast of West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

from December 1927 to February 1928. She became a private ship in January of that year and was refitted at Portsmouth Royal Dockyard in February–July. Shortly after her return to the Mediterranean, ''Barham'' again became flagship of the 1st Battle Squadron in September after her sister ''Warspite'' had to return home for repairs after running aground. Captain James Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville, (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing naval suppo ...

relieved Monroe on 1 December and he was relieved in his turn on 16 March 1929 by Captain John C. Hamilton. The ship was relieved as flagship by in JuneBurt 2012a, p. 135 and she was ordered to Palestine in August where her crew helped to suppress rioting in Haifa and also operated the Haifa-Jerusalem railroad. The ship was transferred to the 2nd Battle Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet in November 1929, and, together with ''Malaya'', made a port visit to Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, an ...

, Norway in mid-1930 where they fired a salute to celebrate the birth of Princess Ragnhild on 9 June.

Between January 1931 and January 1934, ''Barham'' underwent a major refit. While the other four ships of the ''Queen Elizabeth class'' were given a second, more extensive refit in the mid-to-late 1930s (which for ''Warspite'', ''Valiant'' and amounted to a complete reconstruction with new machinery and superstructures), changes to ''Barham'' were relatively minor.Campbell 1980, p. 8 Now under the command of Captain Richard Scott, ''Barham'' was assigned to the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the Firs ...

as the flagship of the 2nd Battle Squadron, and deployed to the West Indies in January–February 1935 for training. The ship participated in the Silver Jubilee Fleet Review for George V on 16 July at Spithead and was then transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet at the end of August. At that time, Captain Norman Wodehouse

Vice Admiral Norman Atherton Wodehouse (18 May 1887 – 4 July 1941) was a Royal Navy officer killed in the Second World War. He had gained 14 caps for England at rugby union, including six as captain between 1910 and 1913. Wodehouse was actin ...

relieved Scott. She was briefly deployed to Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

in May 1936 at the beginning of the Arab revolt in Palestine. Shortly afterwards, she was deployed to Gibraltar for several months after the beginning of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

in July.

''Barham'' served as the flagship of the 1st Battle Squadron from November 1936 to May 1937 and participated in the Coronation Fleet Review for King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

on 19 May at Spithead. She became the flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet on 9 June until relieved by ''Warspite'' on 8 February 1938. Captain Henry Horan

Rear-Admiral Henry Edward Horan CB DSC (12 August 1890 – 15 August 1961) was an Irish Royal Navy officer who became Commander-in-Chief of the New Zealand Division.

Early life and education

Horan was born in Newcastle West, County Limerick t ...

assumed command on 28 July 1937, although he only remained in command until 22 April 1938 when he was relieved by Captain Algernon Willis

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Algernon Usborne Willis (17 May 1889 – 12 April 1976) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War and saw action at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. He also served in the Second World War as Commander ...

. The ship resumed her former role as flagship of the 1st Battle Squadron in February 1938 while undergoing a refit at Portsmouth that lasted until May. Willis was relieved by Captain Thomas Walker on 31 January 1939. During a port visit to Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

in July, the ship was visited by King George II of Greece

George II ( el, Γεώργιος Βʹ, ''Geórgios II''; 19 July Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S.:_7_July.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>O.S.:_7_July">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html"_;"title="nowiki/ ...

.

Second World War

''Barham'' remained part of the Mediterranean Fleet at the outbreak of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

in September 1939. She became a private ship on 1 December and departed Alexandria to join the Home Fleet that same day. On 12 December, she accidentally rammed one of her escorts, the destroyer , in thick fog west of the Mull of Kintyre

The Mull of Kintyre is the southwesternmost tip of the Kintyre Peninsula (formerly ''Cantyre'') in southwest Scotland. From here, the Antrim coast of Northern Ireland is visible on a calm and clear day, and a historic lighthouse, the second ...

. ''Duchess'' capsized and sank, with the loss of 124 of her crew.

''Barham'', the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

and the destroyers , , , and were on patrol off the Butt of Lewis

The Butt of Lewis ( gd, Rubha Robhanais) is the most northerly point of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. The headland, which lies in the North Atlantic, is frequently battered by heavy swells and storms and is marked by the Butt of Lewis Lighthouse. ...

to protect against a possible break-out into the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

by German warships when they were spotted by the , commanded by Fritz-Julius Lemp, on 28 December. Lemp fired four torpedoes at the two capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

s, and one struck ''Barham'' on her port side, adjacent to the shell rooms for 'A' and 'B' turrets. The anti-torpedo bulge was essentially destroyed adjacent to the strike, with four men killed and two wounded.Whitley, p. 103 Most of the adjacent compartments flooded and the ship took on a 7 degree list

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby unio ...

that was countered by transferring fuel oil to starboard. ''Barham''s speed was initially reduced to , but it was increased to about an hour and a half later and she was able to proceed under her own power to Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liv ...

for repairs by Cammell Laird

Cammell Laird is a British shipbuilding company. It was formed from the merger of Laird Brothers of Birkenhead and Johnson Cammell & Co of Sheffield at the turn of the twentieth century. The company also built railway rolling stock until 1929, ...

that lasted until April 1940.

marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refl ...

participated. In preparation for Operation Menace

The Battle of Dakar, also known as Operation Menace, was an unsuccessful attempt in September 1940 by the Allies to capture the strategic port of Dakar in French West Africa (modern-day Senegal). It was hoped that the success of the operation cou ...

, a British naval attack on Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

, Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

, prior to a planned landing by the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

, the ship was detached from the Home Fleet on 28 August and was assigned to Force M, the Royal Navy component of the operation. She departed Scapa Flow that day, escorted by four destroyers, and rendezvoused with the troop convoy en route to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

where she arrived on 2 September. She later became the flagship of Force M's commander, Vice-Admiral John Cunningham. Reinforced by the battleship and the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

from Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

, ''Barham'' departed Gibraltar for Freetown

Freetown is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educ ...

, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

, four days later.

Operation Menace

Force M departed Freetown for Dakar on 21 September and had arrived Dakar before dawn two days later. After Free French emissaries were either captured or driven off by theVichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

, Cunningham ordered his ships to open fire. ''Barham''s six-inch guns were the first to do so and fired at the on the surface. They claimed at least one hit and the submarine was finished off by two of the escorting destroyers and the light cruiser . Her main guns targeted the port and the battleship . Hindered by poor visibility, no significant damage was inflicted and ''Richelieu'' was not hit before the bombardment was called off after 20 minutes.

After the expiration of an ultimatum to surrender the following morning, the battleships engaged the port's coastal artillery, coast-defence guns and ''Richelieu'' at 09:30. The latter was only struck by a single shell splinter before the Allies broke off the bombardment at 10:07, although she had hit ''Barham'' once with a shellJordan & Dumas, p. 143 that blew a hole in diameter in the bulge.Director of Naval Construction The sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining supp ...

d from the harbour at 12:00 to rescue a British pilot in the water, but was engaged at 12:53 by the battleships at a range of . The ship was not hit, but was forced to return to port under the cover of a heavy smoke screen. The British battleships then switched targets to bombard the harbour and ''Richelieu''. They set several merchant ships on fire, but again failed to hit the latter at a range of before breaking off fire at 13:20. During this time ''Barham'' was struck by a 24 cm shell that penetrated through the superstructure before exploding with little effect and without causing any casualties. Another shell, probably also 24 cm in size, detonated in the water on the starboard side abreast of the funnels. The resulting shockwave pushed the bulge inwards for a length of and it started to slowly flood.

After a conference aboard ''Barham'' later that day, the Allied commanders resolved to continue the attack. On the morning of 25 September, ''Richelieu'' was the first ship to open fire at 09:04 at a range of . As the British battleships were manoeuvring to take up their positions, the submarine fired a spread of four torpedoes at a range of . ''Barham'' was able to dodge them, but ''Resolution'' was struck by one torpedo amidships that caused a heavy list, and she fell out of line. ''Barham'' opened fire at a range of and hit ''Richelieu'' with one 15-inch shell at 09:15. The shell devastated a messdeck and dented the armoured deck by a depth of , but caused no casualties. The severe damage to ''Resolution'' caused Operation Menace to be abandoned and ''Barham'' had to tow her to Freetown for temporary repairs, before escorting a convoy to Gibraltar where she arrived on 15 October where her own damage was repaired. She was briefly assigned to Force H, before she was transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet in November 1940.

''Barham'', two cruisers, and three destroyers also assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet were designated Force F as part of Operation Coat, one of a complex series of fleet movements in the Mediterranean. The battleship and the other ships of Force F were tasked to ferry troops to Malta, before continuing on to Alexandria. ''Barham'' was loaded with 600 troops, including the men of 12 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

, Force F departed Gibraltar on 7 November, escorted by Force H, rendezvoused with the main body of the Mediterranean Fleet three days later and unloaded their cargo at Malta later that day. While sailing eastwards, the aircraft carrier was detached from the main body to attack Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label=Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important comme ...

on the night of 11/12 November, damaging three Italian battleships. ''Barham'', now assigned to the 1st BS, and ''Malaya'' were detached to refuel at Souda Bay

Souda Bay is a bay and natural harbour near the town of Souda on the northwest coast of the Greek island of Crete. The bay is about 15 km long and only two to four km wide, and a deep natural harbour. It is formed between the Akrotiri p ...

, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, before sailing for Alexandria, reaching there on 14 November. As part of Operation Collar in late November, ''Barham'', ''Malaya'' and the carrier covered the forces rendezvousing with a convoy coming from Gibraltar. En route, ''Eagle''s aircraft attacked Tripoli on 26 November. ''Barham'' became the flagship of the 1st BS in December.

1941

On 3 January 1941, the ship, together with ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'', bombarded

On 3 January 1941, the ship, together with ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'', bombarded Bardia

Bardia, also El Burdi or Barydiyah ( ar, البردية, lit=, translit=al-Bardiyya or ) is a Mediterranean seaport in the Butnan District of eastern Libya, located near the border with Egypt. It is also occasionally called ''Bórdi Slemán''.

...

as a prelude to the Battle of Bardia

The Battle of Bardia was fought between 3 and 5 January 1941, as part of Operation Compass, the first British military operation of the Western Desert campaign of the Second World War. It was the first battle of the war in which an Australian ...

. On 26 March, the Italian fleet sortied in an attempt to intercept British convoys to Greece. The British had recently broken the Italian codes and sailed after dark on the 27th to intercept the Italians. The following morning, they were spotted by an aircraft from the carrier and the Battle of Cape Matapan

The Battle of Cape Matapan ( el, Ναυμαχία του Ταινάρου) was a naval battle during the Second World War between the Allies, represented by the navies of the United Kingdom and Australia, and the Royal Italian navy, from 27 t ...

began. Multiple air strikes by ''Formidable''s Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s damaged the battleship and crippled the heavy cruiser later that evening. Admiral Angelo Iachino

Angelo Iachino (or ''Jachino''; April 24, 1889–December 3, 1976) was an Italian admiral during World War II.

Early life and career

Iachino was born in Sanremo, Liguria, in 1889, Birth name: Angelo Francesco Jachino. the son of Giuseppe ...

, commander of the Italian fleet, ordered the two other heavy cruisers of the 1st Division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

to render assistance to ''Pola'' in the darkness. The Italian ships and the British arrived almost simultaneously at ''Pola''s location, but the Italians had almost no clue that the British were nearby. On the other hand, the British knew exactly where the Italians were, thanks to their radar-equipped ships. They opened fire at point-blank range

Point-blank range is any distance over which a certain firearm can hit a target without the need to compensate for bullet drop, and can be adjusted over a wide range of distances by sighting in the firearm. If the bullet leaves the barrel para ...

, ''Barham'' crippling the destroyer and then joining ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' in crippling .

In mid-April she escorted the fast transport , together with ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'', from Alexandria to Malta before the battleships bombarded Tripoli on the evening of 20 April. On 612 May, she covered the Alexandria-Malta convoy of Operation Tiger. With her newly arrived sister ''Queen Elizabeth'', ''Barham'' escorted ''Formidable'' as her aircraft attacked the Italian airfield at Scarpanto

Karpathos ( el, Κάρπαθος, ), also Carpathos, is the second largest of the Greek Dodecanese islands, in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Together with the neighboring smaller Saria Island it forms the municipality of Karpathos, which is part of ...

at dawn on 26 May with some success. While covering the evacuation of Crete the following day, the ship was attacked by Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called '' Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") that would be too fast ...

bombers from II./ LG (Demonstration Wing) 1 and Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a " wolf in sheep's clothing". Due to restrictions placed on Germany after t ...

bombers of II./ KG (Bomber Wing) 26. One bomb struck 'Y' turret and started a fire inside the turret that took 20 minutes to quench. A near miss ruptured her portside bulge over an area and caused a 1.5 degree list that was easily corrected by pumping oil. Casualties were five dead and six wounded. She reached Alexandria later that day, but she was too large for the floating dock there and had to be sent elsewhere for repairs. She sailed south through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

to Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of the British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital city status. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town ...

, Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

, where her damage was inspected. It proved to be worse than expected and ''Barham'' had to be repaired at Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

, as she was unfit to make the trans-Atlantic crossing for repair in the United States. Repairs were completed six weeks later on 30 July and the ship returned to Alexandria in August where she resumed her role as flagship of the 1st Battle Squadron.

Sinking

On the afternoon of 24 November 1941, the 1st Battle Squadron, ''Barham'', ''Queen Elizabeth'', and ''Valiant'', with an escort of eight destroyers, departed Alexandria to cover the 7th and 15th Cruiser Squadrons as they hunted for Italian convoys in the Central Mediterranean. The following morning, the , commanded by ''

On the afternoon of 24 November 1941, the 1st Battle Squadron, ''Barham'', ''Queen Elizabeth'', and ''Valiant'', with an escort of eight destroyers, departed Alexandria to cover the 7th and 15th Cruiser Squadrons as they hunted for Italian convoys in the Central Mediterranean. The following morning, the , commanded by ''Oberleutnant zur See

''Oberleutnant zur See'' (''OLt zS'' or ''OLZS'' in the German Navy, ''Oblt.z.S.'' in the '' Kriegsmarine'') is traditionally the highest rank of Lieutenant in the German Navy. It is grouped as OF-1 in NATO.

The rank was introduced in the Imp ...

'' Hans-Diedrich von Tiesenhausen

Hans-Diedrich von Tiesenhausen (22 February 1913 – 17 August 2000) was a German naval commander during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross of Nazi Germany.

Career