Gustavus Swift on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gustavus Franklin Swift, Sr. (June 24, 1839 – March 29, 1903) was an American business executive. He founded a meat-packing empire in the Midwest during the late 19th century, over which he presided until his death. He is credited with the development of the first practical ice-cooled railroad car, which allowed his company to ship dressed meats to all parts of the country and abroad, ushering in the "era of cheap beef." Swift pioneered the use of

A number of attempts were made during the mid-19th century to ship agricultural products via rail car. As early as 1842 the

A number of attempts were made during the mid-19th century to ship agricultural products via rail car. As early as 1842 the

The meat packing plants of Chicago were among the first to utilize

The meat packing plants of Chicago were among the first to utilize

"Development of the U.S. Meat Industry"

— Kansas State University Department of Animal Sciences and Industry *Buenker, John D. (2000

"Swift, Gustavus Franklin"

— American National Biography Online *Chandler, Alfred D. (1959)

''Integration and Diversification as Business Strategies — An Historical Analysis''

( PDF) —

"Swift and Company"

— ''The Handbook of Texas Online'' *Swift & Company (1920). ''The Meat Packing Industry in America''. Swift & Company, Chicago. * *White, John H. (1986) ''The Great Yellow Fleet''. Golden West Books,

Thomas W. Goodspeed (1921) "Gustavus Franklin Swift."

Annie May Swift Hall

at Northwestern University.

Scheduled To Close: Swift & Co. Plant Was a Boon to SSF

from City of South San Francisco official website

Gustavus Franklin Swift

— American National Business Hall of Fame (2002).

Swift & Company

official website {{DEFAULTSORT:Swift, Gustavus 1839 births 1903 deaths Businesspeople in the meat packing industry 19th-century American businesspeople University of Chicago people Northwestern University trustees American people in rail transportation South Omaha, Nebraska People from Bourne, Massachusetts Businesspeople from Chicago Burials at Mount Hope Cemetery (Chicago)

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

by-products for the manufacture of soap, glue, fertilizer

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

, various types of sundries, and even medical products.

Swift donated large sums of money to such institutions as the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

, and YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams (philanthropist), Georg ...

. He established Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

's "School of Oratory" in memory of his daughter, Annie May Swift, who died while a student there. When he died in 1903, his company was valued at between US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

125 million and $135 million, and had a workforce of more than 21,000. "The House of Swift" slaughtered as many as two million cattle, four million hogs, and two million sheep a year. Three years after his death, the value of the company's capital stock topped $250 million. He and his family are interred in a mausoleum in Mount Hope Cemetery in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

.

Biography

Swift was born on June 24, 1839 inSagamore, Massachusetts

Sagamore is a census-designated place (CDP) in the town of Bourne in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 3,623 at the 2010 census.

"Sagamore" was one of the words used by northeastern Native Americans to design ...

, the 9th of 12 offspring of William Swift and Sally Crowell. His parents were descendants of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

settlers who went to New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

in the 17th century. The family (which included Gustavus’ brothers Noble and Edwin) lived and worked on a farm in the Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

town of West Sandwich, Massachusetts

Sandwich is a town in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, and is the oldest town on Cape Cod. The town motto is ''Post tot Naufracia Portus'', "after so many shipwrecks, a haven". The population was 20,259 at the 2020 census.

History

Cape Cod ...

where they raised and slaughtered cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

, sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated ...

, and hogs. This is where he got the idea of packing meat.

As a young boy, Swift took little interest in his studies and left the nearby country school after eight years. During that period he was employed in several jobs, finally finding full-time work in his elder brother Noble's butcher

A butcher is a person who may slaughter animals, dress their flesh, sell their meat, or participate within any combination of these three tasks. They may prepare standard cuts of meat and poultry for sale in retail or wholesale food establishm ...

shop at the age of fourteen. Two years later, in 1855, he opened his own cattle and pork

Pork is the culinary name for the meat of the domestic pig (''Sus domesticus''). It is the most commonly consumed meat worldwide, with evidence of pig husbandry dating back to 5000 BCE.

Pork is eaten both freshly cooked and preserved; ...

butchering business with the help of one of his uncles who gave him $400. Swift purchased livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to animal ...

at the market in Brighton and drove them to Eastham, a ten-day journey. A shrewd businessman, he purportedly followed the somewhat common practice of denying his herds water during the last miles of the trip so that they would drink large quantities of liquid once they reached their final destination, effectively boosting their weights. Swift married Annie Maria Higgins of North Eastham in 1861. Annie gave birth to eleven children, nine of whom reached adulthood. In 1862, Swift and his new bride opened a small butcher shop and slaughterhouse. Seven years later Gustavus and Annie moved the family to the Brighton neighborhood of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, where in 1872 Swift became partner in a new venture, ''Hathaway and Swift''. Swift and partner James A. Hathaway (a renowned Boston meat dealer) initially relocated the company to Albany, then almost immediately thereafter to Buffalo.

An astute cattle-buyer, Swift followed the market steadily westward. On his recommendation, Hathaway and Swift moved once more in 1875, this time to join the influx of meat packers setting up shop in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

's sprawling Union Stock Yards

The Union Stock Yard & Transit Co., or The Yards, was the meatpacking district in Chicago for more than a century, starting in 1865. The district was operated by a group of railroad companies that acquired marshland and turned it into a central ...

. Swift established himself as one of the dominant figures of "The Yards", and his distinctive delivery wagons became familiar fixtures on Chicago's streets. In 1878 his partnership with Hathaway and ''Swift Bros and Company'' was formed in partnership with younger brother Edwin. The company became a driving force in the Chicago meat packing industry

The meat-packing industry (also spelled meatpacking industry or meat packing industry) handles the slaughtering, processing, packaging, and distribution of meat from animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep and other livestock. Poultry is generally no ...

, and was incorporated in 1885 as '' Swift & Co.'' with $300,000 in capital stock and Gustavus Swift as president. It is from this position that Swift led the way in revolutionizing how meat was processed, delivered, and sold.

He died on March 29, 1903, at his home 4848 Ellis Avenue in Chicago.

Chicago and the birth of the meat-packing industry

Following the end of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Chicago emerged as a major railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

center, making it an ideal point for the distribution of livestock raised on the Great Plains to Eastern markets. Getting the animals to market required herds to be driven distances of up to to railhead

In the UK, railheading refers to the practice of travelling further than necessary to reach a rail service, typically by car. The phenomenon is common among commuters seeking a more convenient journey. Reasons for railheading include, but are ...

s in Kansas City, Missouri, where they were loaded into stock car

Stock car racing is a form of automobile racing run on oval tracks and road courses measuring approximately . It originally used production-model cars, hence the name "stock car", but is now run using cars specifically built for racing. It ori ...

s and transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipelin ...

ed live (on the hoof) to regional processing

Processing is a free graphical library and integrated development environment (IDE) built for the electronic arts, new media art, and visual design communities with the purpose of teaching non-programmers the fundamentals of computer programming ...

centers. Driving cattle across the plains led to tremendous weight loss, and a number of animals died in transit. Upon arrival at the local processing facility, livestock were either slaughtered by wholesalers and delivered fresh to nearby butcher shops for retail sale, smoked, or packed for shipment in barrels of salt.

Certain inefficiencies were inherent in the process of transporting live animals by rail, particularly due to the fact that approximately 60% of the animal's mass is inedible. Many animals weakened by the long drive died in transit, further increasing the per-unit shipping cost. Swift's solution to these problems was to devise a method to ship dressed meats from his packing plant in Chicago to the East.

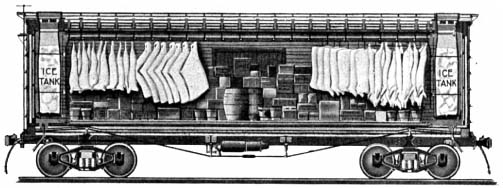

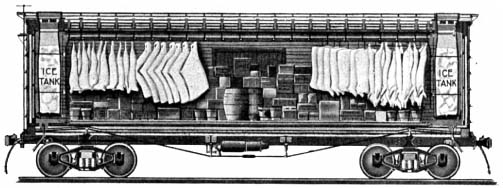

Advent of the refrigerator car

A number of attempts were made during the mid-19th century to ship agricultural products via rail car. As early as 1842 the

A number of attempts were made during the mid-19th century to ship agricultural products via rail car. As early as 1842 the Western Railroad of Massachusetts

The Boston and Albany Railroad was a railroad connecting Boston, Massachusetts to Albany, New York, later becoming part of the New York Central Railroad system, Conrail, and CSX Transportation. The line is currently used by CSX for freight. Pass ...

was reported in the June 15 edition of the ''Boston Traveler'' to be experimenting with innovative freight car

A railroad car, railcar (American and Canadian English), railway wagon, railway carriage, railway truck, railwagon, railcarriage or railtruck (British English and UIC), also called a train car, train wagon, train carriage or train truck, is a ...

designs capable of carrying all types of perishable goods without spoilage. The first known refrigerated boxcar or "reefer" entered service on the Northern Railroad (or NRNY, which became part of the Rutland Railroad

The Rutland Railroad was a railroad in the northeastern United States, located primarily in the state of Vermont but extending into the state of New York at both its northernmost and southernmost ends. After its closure in 1961, parts of the ...

) in June 1851. This "icebox on wheels" was a limited success in that it was only able to function in cold weather. That same year, the Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad

The Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad was founded in 1849 as the Northern Railroad running from Ogdensburg to Rouses Point, New York. The railroad was leased by rival Central Vermont Railroad for several decades, ending in 1896. It was pur ...

(O&LC) began shipping butter to Boston in purpose-built freight cars, utilizing ice to cool the contents.

The first consignment of dressed beef to leave the Chicago stockyards was in 1857, and was carried in ordinary boxcar

A boxcar is the North American ( AAR) term for a railroad car that is enclosed and generally used to carry freight. The boxcar, while not the simplest freight car design, is considered one of the most versatile since it can carry most ...

s retrofitted with bins filled with ice. Placing the meat directly against ice resulted in discoloration and affected the taste, hence proved impractical. During the same period Swift experimented by moving cut meat using a string of ten boxcars which ran with their doors removed, and made a few test shipments to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

during the winter months over the Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway (; french: Grand Tronc) was a railway system that operated in the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and in the American states of Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The rail ...

(GTR). The method proved too limited to be practical. Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

's William Davis patented a refrigerator car that employed metal racks to suspend the carcasses above a frozen mixture of ice and salt. He sold the design in 1868 to George H. Hammond, a Detroit meat-packer, who built a set of cars to transport his products to Boston using ice from the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

for cooling. The loads had the unfortunate tendency of swinging to one side when the car entered a curve at high speed, and the use of the units was discontinued after several derailments. In 1878 Swift hired engineer Andrew Chase to design a ventilated car that was well-insulated, and positioned the ice in a compartment at the top of the car, allowing the chilled air to flow naturally downward.

The meat was packed tightly at the bottom of the car to keep the center of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force ma ...

low and to prevent the cargo from shifting. Chase's design proved to be a practical solution to providing temperature-controlled carriage of dressed meats, and allowed Swift & Company to ship their products all over the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, and internationally. This radically altered the meat business. Swift's attempts to sell this design to the major railroads were unanimously rebuffed as the companies feared that they would jeopardize their considerable investments in stock cars

Stock car racing is a form of automobile racing run on oval tracks and road courses measuring approximately . It originally used production-model cars, hence the name "stock car", but is now run using cars specifically built for racing. It ori ...

and animal pens if refrigerated meat transport gained wide acceptance. In response, Swift financed the initial production run on his own, then — when the American railroads refused his business — he contracted with the GTR (a railroad that derived little income from transporting live cattle) to haul them into Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

and then eastward through Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. In 1880, the Peninsular Car Company

The Peninsular Car Company was a railroad rolling stock manufacturer, founded by Charles L. Freer and Frank J. Hecker in 1885.

In 1892, the company merged with Michigan Car Company, the Russel Wheel and Foundry Company, the Detroit Car Wheel C ...

(subsequently purchased by American Car & Foundry) delivered to Swift the first of these units, and the Swift Refrigerator Line (SRL) was created. Within a year the Line's roster had risen to nearly 200 units, and Swift was transporting an average of 3,000 carcasses a week to Boston. Competing firms such as Armour and Company

Armour & Company was an American company and was one of the five leading firms in the meat packing industry. It was founded in Chicago, in 1867, by the Armour brothers led by Philip Danforth Armour. By 1880, the company had become Chicago's mo ...

quickly followed. By 1920 the SRL owned and operated 7,000 ice-cooled rail cars. The General American Transportation Corporation assumed ownership of the line in 1930.

Live cattle and dressed beef deliveries to New York (ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s):

The subject cars travelled on the Erie

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 a ...

, Lackawanna, New York Central, and Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

railroads.

Source: ''Railway Review'', January 29, 1887, p. 62.

"Everything but the squeal"

In response to public outcries to reduce the amount of pollutants generated by his packing plants, Swift sought innovative ways to use previously discarded portions of the animals his company butchered. This practice led to the wide scale commercial production of such diverse products as oleomargarine,soap

Soap is a salt of a fatty acid used in a variety of cleansing and lubricating products. In a domestic setting, soaps are surfactants usually used for washing, bathing, and other types of housekeeping. In industrial settings, soaps are use ...

, glue, fertilizer

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

, hairbrushes, buttons, knife handles, and pharmaceutical

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field an ...

preparations such as pepsin

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides. It is produced in the gastric chief cells of the stomach lining and is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, w ...

and insulin. Low-grade meats were canned in products like pork and beans

Pork and beans is a culinary dish that uses pork and beans as its main ingredients. Numerous variations exist, usually with a more specific name, such as Fabada Asturiana, Olla podrida, or American canned pork and beans.

American canned por ...

.

The absence of federal

Federal or foederal (archaic) may refer to:

Politics

General

*Federal monarchy, a federation of monarchies

*Federation, or ''Federal state'' (federal system), a type of government characterized by both a central (federal) government and states or ...

inspection led to abuses. Sausages might incorporate sawdust, and meat that had spoiled was sometimes packed and sold. (Swift once bragged that his slaughterhouses had become so sophisticated that they used "everything but the squeal.") Transgressions such as these were first documented in Upton Sinclair's fictional novel ''The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers we ...

'', the publication of which shocked the nation and led to the passing of the Federal Meat Inspection Act

The Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906 (FMIA) is an American law that makes it illegal to adulterate or misbrand meat and meat products being sold as food, and ensures that meat and meat products are slaughtered and processed under strictly r ...

of 1906.Kutner

Vertical integration

The meat packing plants of Chicago were among the first to utilize

The meat packing plants of Chicago were among the first to utilize assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in se ...

(or in this case, disassembly-line) production techniques. Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

states in his autobiography ''My Life and Work'' that it was a visit to a Chicago slaughterhouse which opened his eyes to the virtues of employing a moving conveyor system and fixed work stations in industrial applications. These practices symbolize the concept of "rationalized organization of work" to this day.

Swift adapted the methods of the industrial revolution to meat packing operations, which resulted in huge efficiency by allowing his plants to produce on a massive scale. The work was divided into myriad specific sub-tasks, which were carried out under the direction of supervisory personnel. Swift & Co. was broken down organizationally into various divisions, each one responsible for conducting a different aspect of the business of "bringing meat from the ranch to the consumer". By developing a vertically integrated

In microeconomics, management and international political economy, vertical integration is a term that describes the arrangement in which the supply chain of a company is integrated and owned by that company. Usually each member of the supply ...

company, Swift was able to control the sale of his meats from the slaughterhouse to the local butcher shop.Chandler, p. 70

Swift devoted a great deal of time to indoctrinating employees and teaching them the company's methods and policies. He also motivated his employees to focus on the company's profit goals by adhering to a strict policy of promotion from within. The innovations that Swift championed not only revolutionized the meat packing industry, but also played a vital role in establishing the modern American business system, with an emphasis on mass production, functional specialization, managerial expertise, national distribution networks, and adaptation to technological innovation.

Notes

References

*Boyle, Elizabeth and Rodolfo Estrada. (1994"Development of the U.S. Meat Industry"

— Kansas State University Department of Animal Sciences and Industry *Buenker, John D. (2000

"Swift, Gustavus Franklin"

— American National Biography Online *Chandler, Alfred D. (1959)

''Integration and Diversification as Business Strategies — An Historical Analysis''

( PDF) —

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

*Kutner, Jon Jr"Swift and Company"

— ''The Handbook of Texas Online'' *Swift & Company (1920). ''The Meat Packing Industry in America''. Swift & Company, Chicago. * *White, John H. (1986) ''The Great Yellow Fleet''. Golden West Books,

San Marino, California

San Marino is a residential city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. It was incorporated on April 25, 1913. At the 2010 census the population was 13,147. The city is one of the wealthiest places in the nation in terms of househo ...

.

Further reading

*Lowe, David Garrard (2000) ''Lost Chicago''. Watson-Guptill Publications, New York . * Neilson, Helen Louise Swift (1937) ''My Father and My Mother''. The Lakeside Press, Chicago. * Swift, Louis Franklin andArthur Van Vlissingen Arthur Van Vlissingen Jr. (November 22, 1894 - October 20, 1986) was an American writer and bureau chief for '' Business Week'' and ''Newsweek,'' noted as editor of the ''Factory and Industrial Management'' journal."Writer Arthur Van Vlissingen : He ...

(1927) ''The Yankee of the Yards: The Biography of Gustavus Franklin Swift''. A.W. Shaw and Company, Chicago— provides a history of Chicago's meat packing industry from the viewpoint of the son of the founder of the largest packing company in the world.Thomas W. Goodspeed (1921) "Gustavus Franklin Swift."

External links

Annie May Swift Hall

at Northwestern University.

Scheduled To Close: Swift & Co. Plant Was a Boon to SSF

from City of South San Francisco official website

Gustavus Franklin Swift

— American National Business Hall of Fame (2002).

Swift & Company

official website {{DEFAULTSORT:Swift, Gustavus 1839 births 1903 deaths Businesspeople in the meat packing industry 19th-century American businesspeople University of Chicago people Northwestern University trustees American people in rail transportation South Omaha, Nebraska People from Bourne, Massachusetts Businesspeople from Chicago Burials at Mount Hope Cemetery (Chicago)