Gus Hall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gus Hall (born Arvo Kustaa Halberg; October 8, 1910 – October 13, 2000) was the General Secretary of the

Hall was born Arvo Kustaa Halberg in 1910 in Cherry Township,

Hall was born Arvo Kustaa Halberg in 1910 in Cherry Township,

/ref> Hall became an organizer for the

in the

Now a major American communist leader in the post-war era, Hall caught the attention of United States officials. On July 22, 1948, Hall and 11 other Communist Party leaders were indicted under the

Now a major American communist leader in the post-war era, Hall caught the attention of United States officials. On July 22, 1948, Hall and 11 other Communist Party leaders were indicted under the

in Russian) Hall ran for president four times — in 1972, 1976, 1980, and 1984 — the last two times with Angela Davis. Of the four elections, Hall received the largest number of votes in 1976, largely because of the

Accessed April 27, 2010 Owing to the great expense of running, the difficulty in meeting the strenuous and different election law provisions in each state, and the difficulty in getting media coverage, the CPUSA decided to suspend running national campaigns while continuing to run candidates at the local level. While ceasing presidential campaigns, the CPUSA did not renew support for the Democratic party. The 1980s were a politically difficult decade for Hall and the CPUSA, as one of Hall's trusted confidants and the deputy head of the CPUSA,

"Gus Hall"

''The Times'', Oct. 18, 2000. * Tuomas Savonen, ''Minnesota, Moscow, Manhattan. Gus Hall's life and political line until the late 1960s'' Helsinki: The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters, 2020.

Gus Hall Communist Party Meeting Recordings

a

the Newberry Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hall, Gus 1910 births 2000 deaths 20th-century American politicians Activists for African-American civil rights American anti-capitalists American communists American expatriates in the Soviet Union American people of Finnish descent American anti-racism activists American anti-poverty advocates Burials at Forest Home Cemetery, Chicago Candidates in the 1972 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1976 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1980 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1984 United States presidential election COINTELPRO targets Collaborators with the Soviet Union Communist Party USA politicians Deaths from diabetes International Lenin School alumni American trade union leaders Members of the Communist Party USA Military personnel from Minnesota Minnesota socialists People convicted under the Smith Act People from St. Louis County, Minnesota Politicians from Youngstown, Ohio Recipients of the Order of Lenin United States Navy personnel of World War II United States Navy sailors United Steelworkers people

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Rev ...

(CPUSA) and a perennial candidate

A perennial candidate is a political candidate who frequently runs for elected office and rarely, if ever, wins. Perennial candidates' existence lies in the fact that in some countries, there are no laws that limit a number of times a person can ...

for president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

. He was the Communist Party nominee in the 1972, 1976, 1980

Events January

* January 4 – U.S. President Jimmy Carter proclaims a grain embargo against the USSR with the support of the European Commission.

* January 6 – Global Positioning System time epoch begins at 00:00 UTC.

* January 9 – In ...

, and 1984

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

presidential elections. As a labor leader, Hall was closely associated with the so-called " Little Steel" Strike of 1937, an effort to unionize the nation's smaller, regional steel manufacturers. During the Second Red Scare, Hall was indicted under the Smith Act and was sentenced to eight years in prison. After his release, Hall led the CPUSA for over 40 years, often taking an orthodox Marxist–Leninist stance.

Background and early political activism

Hall was born Arvo Kustaa Halberg in 1910 in Cherry Township,

Hall was born Arvo Kustaa Halberg in 1910 in Cherry Township, St. Louis County, Minnesota

St. Louis County is a county located in the Arrowhead Region of the U.S. state of Minnesota. As of the 2020 census, the population was 200,231. Its county seat is Duluth. It is the largest county in Minnesota by land area, and the largest i ...

, a rural community on northern Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

's Mesabi Iron Range

The Mesabi Iron Range is a mining district in northeastern Minnesota following an elongate trend containing large deposits of iron ore. It is the largest of four major iron ranges in the region collectively known as the Iron Range of Minnesot ...

. He was the son of Matt (Matti) and Susan (Susanna) Halberg. Hall's parents were Finnish immigrants from the Lapua region, and were politically radical: they were involved in the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(IWW) and were early members of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) in 1919. The Mesabi Range was one of the most important immigration settlements for Finns, who were often active in labor militancy and political activism. Hall's home language was Finnish, and he conversed with his nine siblings in that language for the rest of his life. He did not know political terminology in Finnish and used mostly English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

when meeting with visiting Finnish Communists.

Hall grew up in a Communist home and was involved early on in politics. According to Hall, after his father was banned from working in the mines for joining an IWW strike, the family grew up in near-starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

in a log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a less finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first generation home building by settlers.

Eur ...

built by Halberg.

At 15, to support the impoverished ten-child family, Hall left school and went to work in the North Woods lumber camps, mines and railroads. Two years later in 1927, he was recruited to the CPUSA by his father.Gus Hall obituary – World Socialist Web Site/ref> Hall became an organizer for the

Young Communist League

The Young Communist League (YCL) is the name used by the youth wing of various Communist parties around the world. The name YCL of XXX (name of country) originates from the precedent established by the Communist Youth International.

Examples of Y ...

(YCL) in the upper Midwest

The Upper Midwest is a region in the northern portion of the U.S. Census Bureau's Midwestern United States. It is largely a sub-region of the Midwest. Although the exact boundaries are not uniformly agreed-upon, the region is defined as referring ...

. In 1931, an apprenticeship in the YCL qualified Hall to travel to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

to study for two years at the International Lenin School

The International Lenin School (ILS) was an official training school operated in Moscow, Soviet Union, by the Communist International from May 1926 to 1938. It was resumed after the Second World War and run by the Communist Party of the Soviet Uni ...

in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

.

Move to Minneapolis

After his studies, Hall moved toMinneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

to further the YCL activities there. He was involved in hunger marches, demonstrations on behalf of farmers, and various strikes during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. In 1934, Hall was jailed for six months for taking part in the Minneapolis Teamster's Strike, led by Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

Farrell Dobbs. After serving his sentence, Hall was blacklisted

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, ...

and was unable to find work under his original name. He changed his name to Gus Hall, derived from Kustaa (Gustav) Halberg.''Gus Hall''in the

American National Biography

The ''American National Biography'' (ANB) is a 24-volume biographical encyclopedia set that contains about 17,400 entries and 20 million words, first published in 1999 by Oxford University Press under the auspices of the American Council of Le ...

The change was confirmed in court in 1935.

Ohio activism

In late 1934, Hall went toOhio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

's Mahoning Valley. Following the call for organizing in the steel industry, Hall was among a handful hired at a steel mill

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-fini ...

in Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio, and the largest city and county seat of Mahoning County. At the 2020 census, Youngstown had a city population of 60,068. It is a principal city of the Youngstown–Warren metropolitan area, whi ...

. During 1935–1936, he was involved in the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

(CIO) and was a founding organizer of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC), which was set up by the CIO. Hall stated that he and others persuaded John L. Lewis, who was one of the founders of the CIO, that steel could be organized.

Marriage and family

In Youngstown, Hall met Elizabeth Mary Turner (1909–2003), a woman of Hungarian background. They were married in 1935. Elizabeth was a leader in her own right, among the first women steelworkers and a secretary of SWOC. They had two children, Barbara (Conway) (born 1938) and Arvo (born 1947)."Little Steel" strike and war service

Hall was a leader of the 1937 "Little Steel" strike, so called because it was directed againstRepublic Steel

Republic Steel is an American steel manufacturer that was once the country's third largest steel producer. It was founded as the Republic Iron and Steel Company in Youngstown, Ohio in 1899. After rising to prominence during the early 20th Centu ...

, Bethlehem Steel

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation was an American steelmaking company headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. For most of the 20th century, it was one of the world's largest steel producing and shipbuilding companies. At the height of its succ ...

and the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company

The Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company, based in Youngstown, Ohio, was an American steel manufacturer. Officially, the company was created on November 23, 1900, when Articles of Incorporation of the Youngstown Iron Sheet and Tube Company were fi ...

, as opposed to the industry giant U.S. Steel. It had previously entered into a contract with SWOC without a strike. The strike was ultimately unsuccessful, and marred by the deaths of workers at Republic plants in Chicago and Youngstown. Hall was arrested for allegedly transporting bomb-making materials intended for Republic's plant in Warren, Ohio

Warren is a city in and the county seat of Trumbull County, Ohio, United States. Located in Northeast Ohio, northeastern Ohio, Warren lies approximately northwest of Youngstown, Ohio, Youngstown and southeast of Cleveland. The population was 39 ...

. He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor and was fined $500. SWOC became the United Steelworkers of America (USWA) in 1942. Philip Murray, USWA founding president, once commented that Hall's leadership of the strike in Warren and Youngstown was a model of effective grassroots organizing.

After the 1937 strike, Hall focused on party activities instead of union work, and became the leader of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Rev ...

(CPUSA) in Youngstown in 1937. His responsibilities in the party grew rapidly, and in 1939 he became the CPUSA leader for the city of Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the United States, U.S. U.S. state, state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along ...

. Hall ran on the CPUSA ticket for Youngstown councilman and also for governor of Ohio

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

, but received few votes. In 1940 Hall was convicted of fraud and forgery in an election scandal and spent 90 days in jail.

Hall volunteered for the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

when World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

broke out, serving as a machinist

A machinist is a tradesperson or trained professional who not only operates machine tools, but also has the knowledge of tooling and materials required to create set ups on machine tools such as milling machines, grinders, lathes, and drilling ...

in Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

. During the first years of the war in Europe, the CPUSA held an isolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entan ...

stance, as the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

were cooperating based on the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

. When Hitler broke the treaty by invading the USSR in June 1941, the CPUSA began to officially support the war effort. During his naval service, Hall was elected in absence to the National Committee of the CPUSA. He was honorably discharged from the Navy on March 6, 1946.

Seen as a Moscow loyalist, Hall's reputation in the party rose after the war. In 1946 he was elected to the national executive board of the party under the new general secretary, Eugene Dennis, a pro-Soviet Marxist–Leninist, who had replaced Earl Browder

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CPUSA during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s.

Durin ...

after the latter's expulsion from the party.

Indictment during the Red Scare and rise to the head of the CPUSA

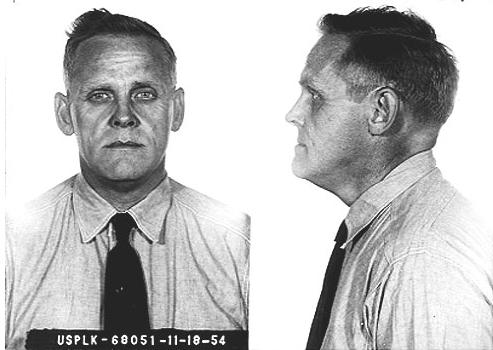

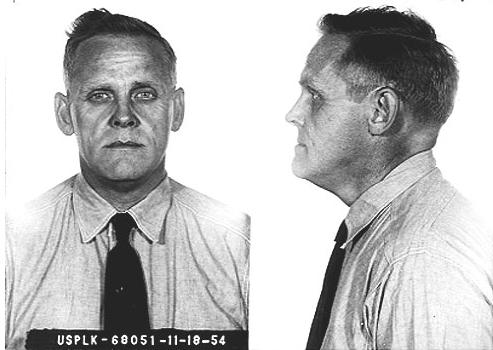

Now a major American communist leader in the post-war era, Hall caught the attention of United States officials. On July 22, 1948, Hall and 11 other Communist Party leaders were indicted under the

Now a major American communist leader in the post-war era, Hall caught the attention of United States officials. On July 22, 1948, Hall and 11 other Communist Party leaders were indicted under the Alien Registration Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of t ...

, popularly called the Smith Act, on charges of "conspiracy to teach and advocate the overthrow of the U.S. government by force and violence", although his conviction was based entirely on Hall's advocacy of Marxist thought. Hall's initial prison sentence lasted for five years.

Released on bail, Hall rose to the secretariat of the CPUSA. When the Supreme Court upheld the Smith Act (June 4, 1951), Hall and three other men skipped bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countries, ...

and went underground. Hall's attempt to flee to Moscow failed when he was picked up in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

on October 8, 1951. He was sentenced to three more years and eventually served over five and a half years in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. In prison he distributed party leaflets and lifted weights. He was located in a cell adjacent to that of George Kelly, a notorious gangster of the prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

era. The Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

later reversed some convictions under the Smith Act as unconstitutional.

In the early 1960s, Hall was in danger of facing yet another indictment, this time under the Internal Security Act of 1950, known as the McCarran Act, but the Supreme Court found the Act partly unconstitutional, and the government abandoned its charges. The act required "Communist action" organizations to register with the government, it excluded party members from applying for United States passports or holding government jobs. Because of the Act, Hall's driver's license was revoked by the State of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.

After his release, Hall continued his activities. He began to travel around the United States, ostensibly on vacation but gathering support to replace Dennis as the general secretary. He accused Dennis of cowardice for not going underground as ordered in 1951 and also claimed Dennis had used funds reserved for the underground for his own purposes. Hall's rise to the position of general secretary was generally unexpected by the American Communist circles (the post was expected to go to either Henry Winston or Gil Green, both important figures in the YCL), although Hall had held the office of acting general secretary briefly in the early 1950s after Dennis's arrest. In 1959, Hall was elected CPUSA general secretary and afterward received the Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (russian: Орден Ленина, Orden Lenina, ), named after the leader of the Russian October Revolution, was established by the Central Executive Committee on April 6, 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration ...

.

General Secretary of the CPUSA

The McCarthyCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

era had taken a heavy toll on the Communist Party USA, as many American members were called to testify to congressional committees

A congressional committee is a legislative sub-organization in the United States Congress that handles a specific duty (rather than the general duties of Congress). Committee membership enables members to develop specialized knowledge of the ...

. In addition, due to the Soviet invasion of Hungary

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

in 1956, many members became disenchanted and left the party. They were also moved by the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

's dismissal of Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the the ...

. In the United States, the rise of the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights ...

and the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

in 1968 created hostility between leftists and the CPUSA, marginalizing it.

Hall, along with other party leaders who remained, sought to rebuild the party. He led the struggle to reclaim the legality of the Communist Party and addressed tens of thousands in Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, and California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

. Envisioning a democratization of the American Communist movement, Hall spoke of a " broad people's political movement" and tried to ally his party with radical campus groups, the anti-Vietnam War movement

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War (before) or anti-Vietnam War movement (present) began with demonstrations in 1965 against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War and grew into a broad social move ...

, organizations active in the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, and the new rank-and-file trade union movements in an effort to build the CPUSA among the young " baby boomer" generation of activists. Ultimately, Hall failed to forge a lasting alliance with the New Left.

Hall had a reputation of being one of the most convinced supporters of the actions and interests of the Soviet Union outside the USSR's political sphere of influence. From 1959 onward, Hall spent some time in Moscow each year and was one of the most widely known American politicians in the USSR, where he was received by high-level Soviet politicians such as Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and 1 ...

.

Hall spoke regularly on campuses and talk shows as an advocate for socialism in the United States. He argued for socialism in the United States to be built on the traditions of U.S.-style democracy rooted in the United States Bill of Rights

The United States Bill of Rights comprises the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. Proposed following the often bitter 1787–88 debate over the ratification of the Constitution and written to address the objections ra ...

. He would often say Americans didn't accept the Constitution without a Bill of Rights and wouldn't accept socialism without a Bill of Rights. He professed deep confidence in the democratic traditions of the American people. He remained a prolific writer on current events, producing a great number of articles and pamphlets, of which many were published in the magazine '' Political Affairs''.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Hall also made frequent appearances on Soviet television

Television in the Soviet Union was owned, controlled and censored by the state. The body governing television in the era of the Soviet Union was the Gosteleradio committee, which was responsible for both the Soviet Central Television and the All ...

, always supporting the position of the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

regime. Hall guided the CPUSA in accordance with the party line of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

" Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspape ...

(CPSU), rejecting any liberalization efforts such as Eurocommunism

Eurocommunism, also referred to as democratic communism or neocommunism, was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more rel ...

. He also dismissed the radical new revolutionary movements that criticized the official Soviet party line of " Peaceful coexistence" and called for a world revolution. After the Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the breaking of political relations between the China, People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union caused by Doctrine, doctrinal divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications ...

, Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

likewise was condemned, and all Maoist sympathizers were expelled from the CPUSA in the early 1960s.

Hall defended the Soviet invasions of Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, and supported the Stalinist principle of " Socialism in One Country". In the early 1980s, Hall and the CPUSA criticized the Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dicti ...

movement in Poland. In 1992, the Moscow daily ''Izvestia

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in 1917, it was a newspaper of record in the Soviet Union until the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, and describes i ...

'' claimed that the CPUSA had received over $40 million in payments from the Soviet Union, contradicting Hall's long-standing claims of financial independence. The former KGB General Oleg Kalugin declared in his memoir that the KGB had Hall and the American Communist Party "under total control" and that he was known to be siphoning off "Moscow money" to set up his own horse-breeding farm. The writer and J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

biographer Curt Gentry has noted that a similar story about Hall was planted in the media through the FBI's secret COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO ( syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program; 1956–1971) was a series of covert and illegal projects actively conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrati ...

campaign of disruption and disinformation against radical opposition groups.Gentry, Curt (1991). ''J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets''. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 443. .

Presidential candidate and later years

In the1964 United States presidential election

The 1964 United States presidential election was the 45th quadrennial presidential election. It was held on Tuesday, November 3, 1964. Incumbent Democratic United States President Lyndon B. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater, the Republican nomi ...

, Hall's party supported Lyndon B. Johnson, saying it was necessary to prevent the victory of the conservative Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

. During the 1972 presidential election, the CPUSA withdrew its support from the Democratic Party and nominated Hall as its candidate.Obituary at Newsru.comin Russian) Hall ran for president four times — in 1972, 1976, 1980, and 1984 — the last two times with Angela Davis. Of the four elections, Hall received the largest number of votes in 1976, largely because of the

Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

bringing protest votes for minor parties. Hall ranked only in eighth place among the presidential candidates.1976 Presidential General Election ResultsAccessed April 27, 2010 Owing to the great expense of running, the difficulty in meeting the strenuous and different election law provisions in each state, and the difficulty in getting media coverage, the CPUSA decided to suspend running national campaigns while continuing to run candidates at the local level. While ceasing presidential campaigns, the CPUSA did not renew support for the Democratic party. The 1980s were a politically difficult decade for Hall and the CPUSA, as one of Hall's trusted confidants and the deputy head of the CPUSA,

Morris Childs

Morris H. Childs (born Moishe Chilovsky; June 10, 1902– June 5, 1991) was a Ukrainian-American political activist and American Communist Party functionary who became a Soviet espionage agent (1929) and then a double agent for the Federal Bureau ...

, was revealed in 1980 to be a longtime Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice ...

informant

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a “snitch”) is a person who provides privileged information about a person or organization to an agency. The term is usually used within the law-enforcement world, where informant ...

. Although Childs was taken into the United States Federal Witness Protection Program and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

in 1987, Hall continued to deny that Childs had been a spy. Also, Henry Winston, Hall's African-American deputy, died in 1986. The black party base questioned the fact that the leadership was exclusively white.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in 1991, the party faced another crisis. In a press conference that year, Hall warned of witch hunts and McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, comparing that country unfavorably with North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

. Hall led a faction of the party that stood against Glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

and Perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

and, for the hardliners of the CPSU, accused Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Com ...

and Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

of "demolishing" socialism. Hall supported Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

and Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

but criticized the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

for failing to oppose the West. In late 1991, members wanting reform founded the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism

The Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (CCDS) is a democratic socialist group in the United States that originated in 1991 as the Committees of Correspondence, a moderate grouping in the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Named afte ...

, a group critical of the direction in which Hall was taking the party. When they were unable to influence the leadership, they left the party and Hall purged them from the membership, including such leaders as Angela Davis and Charlene Mitchell.

During the last years of his life, Hall lived in Yonkers, New York

Yonkers () is a city in Westchester County, New York, United States. Developed along the Hudson River, it is the third most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City and Buffalo. The population of Yonkers was 211,569 as en ...

, with his wife, Elizabeth. Along with following political events, Hall engaged in hobbies that included art collecting, organic gardening

Organic horticulture is the science and art of growing fruits, vegetables, flowers, or ornamental plants by following the essential principles of organic agriculture in soil building and conservation, pest management, and heirloom variety prese ...

, and painting. In 2000, shortly before his death, Hall resigned the post of party chairman in favor of Sam Webb

Samuel Webb (born June 4, 1945) is an American activist and political leader, who served as the Chairman of the Communist Party USA from 2000 to 2014, succeeding the party's longest running leader Gus Hall. Webb did not accept nomination to be ...

and was appointed honorary chairman. in German In 1994, Michael Myerson, who had left the CPUSA along with Herbert Aptheker, Angela Davis, Gil Green, and Charlene Mitchell, accused Hall of living a "good bourgeois life" including "an estate in fashionable Hampton Bays."

Gus Hall died on October 13, 2000, at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

from diabetes mellitus

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

complications. He was buried in the Forest Home Cemetery near Chicago.

Criticism

When theTrotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and its leaders in the Midwest Teamsters were prosecuted under the Smith Act in Minnesota in 1941, some Communist Party members supported the government actions. Later, Hall admitted it was a mistake for the party to not openly fight against imprisonment of SWP members under the Smith Act. The Trotskyist movement held strong negative opinions against Hall; upon his death, the trotskyist World Socialist Web Site denounced him for what they perceived as his incompetence, loyalty to the Soviet Union and accused abandonment of the working class.

At times, some Soviet officials criticized Hall by accusing him of poor leadership of the CPUSA. Young American communists were advised to distance themselves from CPUSA, as the party was under intense FBI surveillance, and these officials believed that under such conditions the party could not be successful.

Many conservatives saw Hall as a threat to the United States, with J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

describing him as "a powerful, deceitful, dangerous foe of Americanism." An inflammatory anti-Christian

Anti-Christian sentiment or Christophobia constitutes opposition or objections to Christians, the Christian religion, and/or its practices. Anti-Christian sentiment is sometimes referred to as Christophobia or Christianophobia, although these terms ...

statement was falsely ascribed to Hall, earning him the hostility of some Christian groups, including Jerry Falwell

Jerry Laymon Falwell Sr. (August 11, 1933 – May 15, 2007) was an American Baptist pastor, televangelism, televangelist, and conservatism in the United States, conservative activist. He was the founding pastor of the Thomas Road Baptist Church, ...

's Moral Majority. In a 1977 speech, future U.S. president Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

planned to quote this alleged 1961 statement as proof of the evils of communism: "I dream of the hour when the last congressman is strangled to death on the guts of the last preacher — and since the Christians seem to love to sing about the blood, why not give them a little of it? Slit the throats of their children nddraw them over the mourner's bench and the pulpit and allow them to drown in their own blood, and then see whether they enjoy singing those hymns." The statement, which Reagan ultimately excised from his speech because he claimed he did not have the "nerve" to say it, was falsely claimed to have been said by Hall at the funeral oration of former CPUSA party chairman William Z. Foster.Kiron K. Skinner, Martin Anderson, Annelise Anderson, eds., Reagan, In His Own Hand (New York, 2002), 34; David C. Wills, The First War on Terrorism: Counter-Terrorism Policy During the Reagan Administration (Lanham, MD, 2003), 22.

Works

* ''Peace can be won!, report to the 15th Convention, Communist Party, U.S.A.'', New York: New Century Publishers, 1951. * ''Our sights to the future: keynote report and concluding remarks at the 17th National Convention of the Communist Party, U.S.A.'', New York: New Century Publishers, 1960. * ''Main Street to Wall Street: End the Cold War!'', New York: New Century Publishers, 1962. * ''Which way U.S.A. 1964? The communist view.'', New York: New Century Publishers, 1964. * ''On course: the revolutionary process; report to the 19th National Convention of the Communist Party, U.S.A. by its general secretary'', New York: New Outlook Publishers and Distributors, 1969. *'' Ecology: Can We Survive Under Capitalism?'',International Publishers

International Publishers is a book publishing company based in New York City, specializing in Marxist works of economics, political science, and history.

Company history

Establishment

International Publishers Company, Inc., was founded in 1924 ...

, New York 1972.

* ''Imperialism today; an evaluation of major issues and events of our time'', New York, International Publishers, 1972

* ''The energy rip-off: cause & cure'', International Publishers, New York 1974, .

* ''The crisis of U.S. capitalism and the fight-back: report to the 21st convention of the Communist Party, U.S.A.'', New York: International Publishers, 1975.

* ''Labor up-front in the people's fight against the crisis: report to the 22nd convention of the Communist Party, USA'', New York: International Publishers, 1979.

* ''Basics: For Peace, Democracy, and Social Progress'', International Publishers, New York. 1980.

* ''For peace, jobs, equality: prevent "The Day after", defeat Reaganism: report to the 23rd Convention of the Communist Party, U.S.A.'', New York: New Outlook Publishers and Distributors, 1983.

* ''Karl Marx: beacon for our times'', International Publishers, New York 1983, .

* ''Fighting racism: selected writings'', International Publishers, New York 1985, .

* ''Working class USA: the power and the movement'', International Publishers, New York 1987, .

Notes and references

Further reading

* Joseph Brandt (ed.), ''Gus Hall: Bibliography'' New York: New Century Publishers, 1981. * Fiona Hamilton"Gus Hall"

''The Times'', Oct. 18, 2000. * Tuomas Savonen, ''Minnesota, Moscow, Manhattan. Gus Hall's life and political line until the late 1960s'' Helsinki: The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters, 2020.

Gus Hall Communist Party Meeting Recordings

a

the Newberry Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hall, Gus 1910 births 2000 deaths 20th-century American politicians Activists for African-American civil rights American anti-capitalists American communists American expatriates in the Soviet Union American people of Finnish descent American anti-racism activists American anti-poverty advocates Burials at Forest Home Cemetery, Chicago Candidates in the 1972 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1976 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1980 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1984 United States presidential election COINTELPRO targets Collaborators with the Soviet Union Communist Party USA politicians Deaths from diabetes International Lenin School alumni American trade union leaders Members of the Communist Party USA Military personnel from Minnesota Minnesota socialists People convicted under the Smith Act People from St. Louis County, Minnesota Politicians from Youngstown, Ohio Recipients of the Order of Lenin United States Navy personnel of World War II United States Navy sailors United Steelworkers people