Gundestrup cauldron on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD,Nielsen, S; Andersen, J; Baker, J; Christensen, C; Glastrup, J; et al. (2005). "The Gundestrup cauldron: New scientific and technical investigations”, ''Acta Archaeologica, 76'': 1–58. Jouttijärvi, Arne (2009), "The Gundestrup Cauldron: Metallurgy and Manufacturing Techniques”, ''Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 24'': 960–966. or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD,Nielsen, S; Andersen, J; Baker, J; Christensen, C; Glastrup, J; et al. (2005). "The Gundestrup cauldron: New scientific and technical investigations”, ''Acta Archaeologica, 76'': 1–58. Jouttijärvi, Arne (2009), "The Gundestrup Cauldron: Metallurgy and Manufacturing Techniques”, ''Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 24'': 960–966. or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early

The Gundestrup cauldron was discovered by peat cutters in a small peat bog called Rævemose (near the larger Borremose bog) on 28 May 1891. The Danish government paid a large reward to the finders, who subsequently quarreled bitterly amongst themselves over its division. Palaeobotanical investigations of the peat bog at the time of the discovery showed that the land had been dry when the cauldron was deposited, and the peat gradually grew over it. The manner of stacking suggested an attempt to make the cauldron inconspicuous and well-hidden. Another investigation of Rævemose was undertaken in 2002, concluding that the peat bog may have existed when the cauldron was buried.

The cauldron was found in a dismantled state with five long rectangular plates, seven short plates, one round plate (normally termed the "base plate"), and two fragments of tubing stacked inside the curved base.

In addition, there is a piece of iron from a ring originally placed inside the silver tubes along the rim of the cauldron. It is assumed that there is a missing eighth plate because the circumference of the seven outer plates is smaller than the circumference of the five inner plates.

A set of careful full-size replicas have been made. One is in the

The Gundestrup cauldron was discovered by peat cutters in a small peat bog called Rævemose (near the larger Borremose bog) on 28 May 1891. The Danish government paid a large reward to the finders, who subsequently quarreled bitterly amongst themselves over its division. Palaeobotanical investigations of the peat bog at the time of the discovery showed that the land had been dry when the cauldron was deposited, and the peat gradually grew over it. The manner of stacking suggested an attempt to make the cauldron inconspicuous and well-hidden. Another investigation of Rævemose was undertaken in 2002, concluding that the peat bog may have existed when the cauldron was buried.

The cauldron was found in a dismantled state with five long rectangular plates, seven short plates, one round plate (normally termed the "base plate"), and two fragments of tubing stacked inside the curved base.

In addition, there is a piece of iron from a ring originally placed inside the silver tubes along the rim of the cauldron. It is assumed that there is a missing eighth plate because the circumference of the seven outer plates is smaller than the circumference of the five inner plates.

A set of careful full-size replicas have been made. One is in the

The Gundestrup cauldron is composed almost entirely of silver, but there is also a substantial amount of gold for the gilding, tin for the solder and glass for the figures' eyes. According to experimental evidence, the materials for the vessel were not added at the same time, so the cauldron can be considered as the work of artisans over a span of several hundred years. The quality of the repairs to the cauldron, of which there are many, is inferior to the original craftsmanship.

Silver was not a common material in Celtic art, and certainly not on this scale. Except sometimes for small pieces of jewellery, gold or bronze were more usual for prestige metalwork. At the time that the Gundestrup cauldron was created, silver was obtained through

The Gundestrup cauldron is composed almost entirely of silver, but there is also a substantial amount of gold for the gilding, tin for the solder and glass for the figures' eyes. According to experimental evidence, the materials for the vessel were not added at the same time, so the cauldron can be considered as the work of artisans over a span of several hundred years. The quality of the repairs to the cauldron, of which there are many, is inferior to the original craftsmanship.

Silver was not a common material in Celtic art, and certainly not on this scale. Except sometimes for small pieces of jewellery, gold or bronze were more usual for prestige metalwork. At the time that the Gundestrup cauldron was created, silver was obtained through

The workflow of the manufacturing process consisted of a few steps that required a great amount of skill. Batches of silver were melted in crucibles with the addition of copper for a subtler alloy. The melted silver was cast into flat ingots and hammered into intermediate plates. For the relief work, the sheet-silver was annealed to allow shapes to be beaten into high repoussé; these rough shapes were then filled with pitch from the back to make them firm enough for further detailing with punches and tracers. The pitch was melted out, areas of pattern were gilded, and the eyes of the larger figures were inlaid with glass. The plates were probably worked in a flat form and later bent into curves to solder them together.

It is generally agreed that the Gundestrup cauldron was the work of multiple silversmiths. Using scanning electron microscopy, Benner Larson has identified 15 different punches used on the plates, falling into three distinct tool sets. No individual plate has marks from more than one of these groups, and this fits with previous attempts at stylistic attribution, which identify at least three different silversmiths. Multiple artisans would also explain the highly variable purity and thickness of the silver.

The workflow of the manufacturing process consisted of a few steps that required a great amount of skill. Batches of silver were melted in crucibles with the addition of copper for a subtler alloy. The melted silver was cast into flat ingots and hammered into intermediate plates. For the relief work, the sheet-silver was annealed to allow shapes to be beaten into high repoussé; these rough shapes were then filled with pitch from the back to make them firm enough for further detailing with punches and tracers. The pitch was melted out, areas of pattern were gilded, and the eyes of the larger figures were inlaid with glass. The plates were probably worked in a flat form and later bent into curves to solder them together.

It is generally agreed that the Gundestrup cauldron was the work of multiple silversmiths. Using scanning electron microscopy, Benner Larson has identified 15 different punches used on the plates, falling into three distinct tool sets. No individual plate has marks from more than one of these groups, and this fits with previous attempts at stylistic attribution, which identify at least three different silversmiths. Multiple artisans would also explain the highly variable purity and thickness of the silver.

The silverworking techniques used in the cauldron are unknown from the Celtic world, but are consistent with the renowned Thracian sheet-silver tradition. The scenes depicted are not distinctively Thracian, but certain elements of composition, decorative motifs, and illustrated items (such as the shoelaces on the antlered figure) identify it as Thracian work.

Taylor and Bergquist have postulated that the Celtic tribe known as the

The silverworking techniques used in the cauldron are unknown from the Celtic world, but are consistent with the renowned Thracian sheet-silver tradition. The scenes depicted are not distinctively Thracian, but certain elements of composition, decorative motifs, and illustrated items (such as the shoelaces on the antlered figure) identify it as Thracian work.

Taylor and Bergquist have postulated that the Celtic tribe known as the

File:Gundestrupkarret3.jpg, Interior plate E

File:Boar-helmeted figure on the Gundestrup Cauldron.jpg, Boar-helmeted figure

File:Detail 3 from Gundestrupkarret.jpg, Detail

File:Figures with horns on the Gundestrup Cauldron.jpg, The

File:Torque à tampons Somme-Suippe Musée Saint-Remi 120208.jpg,

For many years, some scholars have interpreted the cauldron's images in terms of the

For many years, some scholars have interpreted the cauldron's images in terms of the

The antlered figure in plate A has been commonly identified as

The antlered figure in plate A has been commonly identified as

google books

*"Laings", Lloyd Laing and Jennifer Laing. ''Art of the Celts: From 700 BC to the Celtic Revival'', 1992, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), *"Megaws" = Megaw, Ruth and Vincent, ''Celtic Art'', 1989, Thames and Hudson, *"NMD"

"The Gundestrup Cauldron"

2019 revised version

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gundestrup Cauldron 2nd-century BC works 1st-century BC works 1891 archaeological discoveries Archaeological discoveries in Denmark Germanic archaeological artifacts Celtic art Pre-Roman Iron Age Thracian archaeological artifacts Silver objects Treasure troves in Denmark Dogs in art Deer in art Cattle in art Cauldrons Magic items Ancient art in metal

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD,Nielsen, S; Andersen, J; Baker, J; Christensen, C; Glastrup, J; et al. (2005). "The Gundestrup cauldron: New scientific and technical investigations”, ''Acta Archaeologica, 76'': 1–58. Jouttijärvi, Arne (2009), "The Gundestrup Cauldron: Metallurgy and Manufacturing Techniques”, ''Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 24'': 960–966. or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD,Nielsen, S; Andersen, J; Baker, J; Christensen, C; Glastrup, J; et al. (2005). "The Gundestrup cauldron: New scientific and technical investigations”, ''Acta Archaeologica, 76'': 1–58. Jouttijärvi, Arne (2009), "The Gundestrup Cauldron: Metallurgy and Manufacturing Techniques”, ''Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 24'': 960–966. or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early Roman Iron Age

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain,

roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, northern Germany, Poland and the Netherlands.

The regi ...

. The cauldron

A cauldron (or caldron) is a large pot (kettle) for cooking or boiling over an open fire, with a lid and frequently with an arc-shaped hanger and/or integral handles or feet. There is a rich history of cauldron lore in religion, mythology, and ...

is the largest known example of European Iron Age

In Europe, the Iron Age is the last stage of the prehistoric period and the first of the protohistoric periods,The Junior Encyclopædia Britannica: A reference library of general knowledge. (1897). Chicago: E.G. Melvin. (seriously? 1897 "Junior ...

silver work (diameter: ; height: ). It was found dismantled, with the other pieces stacked inside the base, in 1891, in a peat bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; a ...

near the hamlet of Gundestrup in the Aars

Aars or Års, () is a Danish town with a population of 8,474 (1 January 2022)Himmerland

Himmerland is a peninsula in northeastern Jutland, Denmark. It is delimited to the north and the west by the Limfjord, to the east by the Kattegat, and to the south by the Mariager Fjord. The largest city is Aalborg; smaller towns include Hobro, ...

, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

().Bergquist, A K & Taylor, T F (1987), "The origin of the Gundestrup cauldron", ''Antiquity 61'': 10–24.Taylor, Timothy (1992), "The Gundestrup cauldron", ''Scientific American, 266'': 84–89. It is now usually on display in the National Museum of Denmark

The National Museum of Denmark (Nationalmuseet) in Copenhagen is Denmark's largest museum of cultural history, comprising the histories of Danish and foreign cultures, alike. The museum's main building is located a short distance from Strøget ...

in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, with replicas at other museums; during 2015–16, it was in the UK on a travelling exhibition called ''The Celts''.

The cauldron is not complete, and now consists of a rounded cup-shaped bottom making up the lower part of the cauldron, usually called the base plate, above which are five interior plates and seven exterior ones; a missing eighth exterior plate would be needed to encircle the cauldron, and only two sections of a rounded rim at the top of the cauldron survive. The base plate is mostly smooth and undecorated inside and out, apart from a decorated round medallion in the centre of the interior. All the other plates are heavily decorated with repoussé work, hammered from beneath to push out the silver. Other techniques were used to add detail, and there is extensive gilding

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

and some use of inlaid pieces of glass for the eyes of figures. Other pieces of fittings were found. Altogether the weight is just under 9 kilograms.

Despite the fact that the vessel was found in Denmark, it was probably not made there or nearby; it includes elements of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

ish and Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

origin in the workmanship, metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

, and imagery. The techniques and elements of the style of the panels relate closely to other Thracian silver, while much of the depiction, in particular of the human figures, relates to the Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

, though attempts to relate the scenes closely to Celtic mythology

Celtic mythology is the body of myths belonging to the Celtic peoples.Cunliffe, Barry, (1997) ''The Ancient Celts''. Oxford, Oxford University Press , pp. 183 (religion), 202, 204–8. Like other Iron Age Europeans, Celtic peoples followed a ...

remain controversial. Other aspects of the iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

derive from the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

.

Hospitality on a large scale was probably an obligation for Celtic elites, and although cauldrons were therefore an important item of prestige metalwork, they are usually much plainer and smaller than this. This is an exceptionally large and elaborate object with no close parallel, except a large fragment from a bronze cauldron also found in Denmark, at Rynkeby; however the exceptional wetland deposits in Scandinavia have produced a number of objects of types that were probably once common but where other examples have not survived. It has been much discussed by scholars, and represents a fascinatingly complex demonstration of the many cross-currents in European art, as well as an unusual degree of narrative for Celtic art

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and styli ...

, though we are unlikely ever to fully understand its original meanings.

Discovery

The Gundestrup cauldron was discovered by peat cutters in a small peat bog called Rævemose (near the larger Borremose bog) on 28 May 1891. The Danish government paid a large reward to the finders, who subsequently quarreled bitterly amongst themselves over its division. Palaeobotanical investigations of the peat bog at the time of the discovery showed that the land had been dry when the cauldron was deposited, and the peat gradually grew over it. The manner of stacking suggested an attempt to make the cauldron inconspicuous and well-hidden. Another investigation of Rævemose was undertaken in 2002, concluding that the peat bog may have existed when the cauldron was buried.

The cauldron was found in a dismantled state with five long rectangular plates, seven short plates, one round plate (normally termed the "base plate"), and two fragments of tubing stacked inside the curved base.

In addition, there is a piece of iron from a ring originally placed inside the silver tubes along the rim of the cauldron. It is assumed that there is a missing eighth plate because the circumference of the seven outer plates is smaller than the circumference of the five inner plates.

A set of careful full-size replicas have been made. One is in the

The Gundestrup cauldron was discovered by peat cutters in a small peat bog called Rævemose (near the larger Borremose bog) on 28 May 1891. The Danish government paid a large reward to the finders, who subsequently quarreled bitterly amongst themselves over its division. Palaeobotanical investigations of the peat bog at the time of the discovery showed that the land had been dry when the cauldron was deposited, and the peat gradually grew over it. The manner of stacking suggested an attempt to make the cauldron inconspicuous and well-hidden. Another investigation of Rævemose was undertaken in 2002, concluding that the peat bog may have existed when the cauldron was buried.

The cauldron was found in a dismantled state with five long rectangular plates, seven short plates, one round plate (normally termed the "base plate"), and two fragments of tubing stacked inside the curved base.

In addition, there is a piece of iron from a ring originally placed inside the silver tubes along the rim of the cauldron. It is assumed that there is a missing eighth plate because the circumference of the seven outer plates is smaller than the circumference of the five inner plates.

A set of careful full-size replicas have been made. One is in the National Museum of Ireland

The National Museum of Ireland ( ga, Ard-Mhúsaem na hÉireann) is Ireland's leading museum institution, with a strong emphasis on national and some international archaeology, Irish history, Irish art, culture, and natural history. It has thre ...

in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, and several are in France, including the Musée gallo-romain de Fourvière at Lyon and the Musée d'archéologie nationale

The National Archaeological Museum (French: Musée d'Archéologie nationale) is a major French archaeology museum, covering pre-historic times to the Merovingian period (450–750 CE). It is housed in the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye in the ' ...

at Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the centre of Paris.

Inhabitants are called ''Saint-Germanois'' or ''Saint-Ge ...

.

Reconstruction

Since the cauldron was found in pieces, it had to be reconstructed. The traditional order of the plates was determined by Sophus Müller, the first of many to analyze the cauldron. His logic uses the positions of the tracesolder

Solder (; NA: ) is a fusible metal alloy used to create a permanent bond between metal workpieces. Solder is melted in order to wet the parts of the joint, where it adheres to and connects the pieces after cooling. Metals or alloys suitable ...

located at the rim of the bowl. In two cases, a puncture mark penetrating the inner and outer plates also helps to establish the order. In its final form, the plates are arranged in an alternation of female-male depictions, assuming the missing eighth plate is of a female. Not all analysts agree with Müller's ordering, however. Taylor has pointed out that aside from the two cases of puncturing, the order cannot be determined from the solder alignments. His argument is that the plates are not directly adjacent to each other, but are separated by a 2 cm gap; thus, the plates in this order cannot be read with certainty as the true narrative, supposing one exists. However Larsen (2005: 16, fig. 12) indicates, not only did his study vindicate the order for the inner plates established, by Muller, Klindt-Jensen, and Olmsted, but the order of the outer plates is also established by the rivet holes, the solder alignments, and the scrape marks.

Metallurgy

The Gundestrup cauldron is composed almost entirely of silver, but there is also a substantial amount of gold for the gilding, tin for the solder and glass for the figures' eyes. According to experimental evidence, the materials for the vessel were not added at the same time, so the cauldron can be considered as the work of artisans over a span of several hundred years. The quality of the repairs to the cauldron, of which there are many, is inferior to the original craftsmanship.

Silver was not a common material in Celtic art, and certainly not on this scale. Except sometimes for small pieces of jewellery, gold or bronze were more usual for prestige metalwork. At the time that the Gundestrup cauldron was created, silver was obtained through

The Gundestrup cauldron is composed almost entirely of silver, but there is also a substantial amount of gold for the gilding, tin for the solder and glass for the figures' eyes. According to experimental evidence, the materials for the vessel were not added at the same time, so the cauldron can be considered as the work of artisans over a span of several hundred years. The quality of the repairs to the cauldron, of which there are many, is inferior to the original craftsmanship.

Silver was not a common material in Celtic art, and certainly not on this scale. Except sometimes for small pieces of jewellery, gold or bronze were more usual for prestige metalwork. At the time that the Gundestrup cauldron was created, silver was obtained through cupellation

Cupellation is a refining process in metallurgy where ores or alloyed metals are treated under very high temperatures and have controlled operations to separate noble metals, like gold and silver, from base metals, like lead, copper, zinc, arse ...

of lead/silver ores. By comparing the concentration of lead isotopes with the silverwork of other cultures, it has been suggested that the silver came from multiple ore deposits, mostly from Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic northern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and western Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

in the pre-Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

period. The lead isotope studies also indicate that the silver for manufacturing the plates was prepared by repeatedly melting ingots and/or scrap silver. Three to six distinct batches of recycled silver may have been used in making the vessel. Specifically, the circular "base plate" may have originated as a phalera, and it is commonly thought to have been positioned in the bottom of the bowl as a late addition, soldered in to repair a hole. By an alternative theory, this phalera was not initially part of the bowl, but instead formed part of the decorations of a wooden cover.

The gold can be sorted into two groups based on purity and separated by the concentration of silver and copper. The less pure gilding

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

, which is thicker, can be considered a later repair, as the thinner, purer inlay adheres better to the silver. The adherence of the overall gold is quite poor. The lack of mercury from the gold analysis suggests that a fire-gilding technique was not used on the Gundestrup cauldron. The gilding appears to have instead been made by mechanical means, which explains the function of closely spaced punch marks on the gilded areas.

An examination of lead isotopes similar to the one used on the silver was employed for the tin. All of the samples of tin soldering are consistent in lead-isotope composition with ingots from Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

in western Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

. The tin used for soldering the plates and bowl together, as well as the glass eyes, is very uniform in its high purity.

Finally, the glass inlays of the Gundestrup cauldron have been determined through the use of X-ray fluorescence radiation to be of a soda-lime type composition. The glass contained elements that can be attributed to calcareous sand and mineral soda, typical of the east coast of the Mediterranean region. The analyses also narrowed down the production time of the glass to between the second century BC and first century AD.

Flow of raw material

The workflow of the manufacturing process consisted of a few steps that required a great amount of skill. Batches of silver were melted in crucibles with the addition of copper for a subtler alloy. The melted silver was cast into flat ingots and hammered into intermediate plates. For the relief work, the sheet-silver was annealed to allow shapes to be beaten into high repoussé; these rough shapes were then filled with pitch from the back to make them firm enough for further detailing with punches and tracers. The pitch was melted out, areas of pattern were gilded, and the eyes of the larger figures were inlaid with glass. The plates were probably worked in a flat form and later bent into curves to solder them together.

It is generally agreed that the Gundestrup cauldron was the work of multiple silversmiths. Using scanning electron microscopy, Benner Larson has identified 15 different punches used on the plates, falling into three distinct tool sets. No individual plate has marks from more than one of these groups, and this fits with previous attempts at stylistic attribution, which identify at least three different silversmiths. Multiple artisans would also explain the highly variable purity and thickness of the silver.

The workflow of the manufacturing process consisted of a few steps that required a great amount of skill. Batches of silver were melted in crucibles with the addition of copper for a subtler alloy. The melted silver was cast into flat ingots and hammered into intermediate plates. For the relief work, the sheet-silver was annealed to allow shapes to be beaten into high repoussé; these rough shapes were then filled with pitch from the back to make them firm enough for further detailing with punches and tracers. The pitch was melted out, areas of pattern were gilded, and the eyes of the larger figures were inlaid with glass. The plates were probably worked in a flat form and later bent into curves to solder them together.

It is generally agreed that the Gundestrup cauldron was the work of multiple silversmiths. Using scanning electron microscopy, Benner Larson has identified 15 different punches used on the plates, falling into three distinct tool sets. No individual plate has marks from more than one of these groups, and this fits with previous attempts at stylistic attribution, which identify at least three different silversmiths. Multiple artisans would also explain the highly variable purity and thickness of the silver.

Origins

The silverworking techniques used in the cauldron are unknown from the Celtic world, but are consistent with the renowned Thracian sheet-silver tradition. The scenes depicted are not distinctively Thracian, but certain elements of composition, decorative motifs, and illustrated items (such as the shoelaces on the antlered figure) identify it as Thracian work.

Taylor and Bergquist have postulated that the Celtic tribe known as the

The silverworking techniques used in the cauldron are unknown from the Celtic world, but are consistent with the renowned Thracian sheet-silver tradition. The scenes depicted are not distinctively Thracian, but certain elements of composition, decorative motifs, and illustrated items (such as the shoelaces on the antlered figure) identify it as Thracian work.

Taylor and Bergquist have postulated that the Celtic tribe known as the Scordisci

The Scordisci ( el, Σκορδίσκοι) were a Celtic Iron Age cultural group centered in the territory of present-day Serbia, at the confluence of the Savus (Sava), Dravus (Drava), Margus (Morava) and Danube rivers. They were historically no ...

commissioned the cauldron from native Thracian silversmiths. According to classical historians, the Cimbri

The Cimbri (Greek Κίμβροι, ''Kímbroi''; Latin ''Cimbri'') were an ancient tribe in Europe. Ancient authors described them variously as a Celtic people (or Gaulish), Germanic people, or even Cimmerian. Several ancient sources indicate that ...

, a Teutonic tribe, went south from the lower Elbe region and attacked the Scordisci in 118 BC. After withstanding several defeats at the hands of the Romans, the Cimbri retreated north, possibly taking with them this cauldron to settle in Himmerland, where the vessel was found.

According to Olmsted (2001) the art style of the Gundestrup cauldron is that utilized in Armorican coinage dating to 75-55 BC, as exemplified in the billon coins of the Coriosolites. This art style is unique to northwest Gaul and is largely confined to the region between the Seine and the Loire, a region in which, according to Caesar, the wealthy sea-faring Veneti played a dominant and hegemonic role. Agreeing with this area of production, determined by the art style, is the fact that the “lead isotope compositions of the undestrupcauldron plates” mostly included “the same silver as used in northern France for the Coriosolite coins” (Larsen 2005: 35). Not only does the Gundestrup cauldron enlighten us about this coin-driven art style, where the larger-metalwork smiths were also the mint-masters producing the coins, but the cauldron also portrays cultural items, such as swords, armor, and shields, found and produced in this same cultural area, confirming the agreement between art style and metal analysis. If as Olmsted (2001) and Hachmann (1990) suggest, the Veneti also produced the silver phalerae, found on the Isle of Sark, as well as the Helden phalera, then there are a number of silver items of the type exemplified by the Gundestrup cauldron originating in northwest France, dating to just before the Roman conquest.

Nielsen believes that the question of origin is the wrong one to ask and can produce misleading results. Because of the widespread migration of numerous ethnic groups like the Celts and Teutonic peoples and events like Roman expansion and subsequent Romanization, it is highly unlikely that only one ethnic group was responsible for the development of the Gundestrup cauldron. Instead, the make and art of the cauldron can be thought of as the product of a fusion of cultures, each inspiring and expanding upon one another. In the end, Nielsen concludes that, based on accelerator datings from beeswax found on the back of the plates, the vessel was created within the Roman Iron Age. However, as an addendum to Nielson article indicates (2005: 57), results from the Leibniz Lab on the same bee's wax dated some 400 years earlier.

Iconography

Base plate

The decorated medallion on the circular base plate depicts a bull. Above the back of the bull is a female figure wielding a sword; three dogs are also portrayed, one over the bull's head and another under its hooves. Presumably all of these figures are in combat; the third dog beneath the bull and near its tail seems to be dead, and is only faintly shown inengraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a Burin (engraving), burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or Glass engraving, glass ...

, and the bull may have been brought down. Below the bull is scrolling

In computer displays, filmmaking, television production, and other kinetic displays, scrolling is sliding text, images or video across a monitor or display, vertically or horizontally. "Scrolling," as such, does not change the layout of the text ...

ivy that draws from classical Greco-Roman art. The horns of the bull are missing, but there is a hole right through the head where they were originally fitted; they were perhaps gold. The head of the bull rises entirely clear of the plate, and the medallion is considered the most accomplished part of the cauldron in technical and artistic terms.

Exterior plates

Each of the seven exterior plates centrally depicts a bust. Plates a, b, c, and d show bearded male figures, and the remaining three are female. *On plate a, the bearded man holds in each hand a much smaller figure by the arm. Each of those two reach upward toward a small boar. Under the feet of the figures (on the shoulders of the larger man) are a dog on the left side and a winged horse on the right side. *The figure on plate b holds in each hand a sea-horse or dragon. *On plate c, a male figure raises his empty fists. On his right shoulder is a man in a "boxing" position, and on his left shoulder, there is a leaping figure with a small horseman underneath. *Plate d shows a bearded figure holding a stag by the hind quarters in each hand. *The female figure on plate e is flanked by two smaller male busts. *A female figure holds a bird in her upraised right hand on plate f. Her left arm is horizontal, supporting a man and a dog lying on its back. Two birds of prey are situated on either side of her head. Her hair is being plaited by a small woman on the right. *On plate g, the female figure has her arms crossed. On her right shoulder, a scene of a man fighting a lion is shown. On her left shoulder is a leaping figure similar to the one on plate c.Interior plates

*Plate A shows an antlered male figure seated in a central position, often identified asCernunnos

In ancient Celtic and Gallo-Roman religion, Cernunnos or Carnonos was a god depicted with antlers, seated cross-legged, and is associated with stags, horned serpents, dogs and bulls. He is usually shown holding or wearing a torc and somet ...

. In his right hand, Cernunnos holds a torc

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some had hook and ring closures and a few had ...

, and with his left hand he grips a horned serpent a little below the head. To the left is a stag with antlers that are very similar to the human/divine figure. Surrounding the scene are other canine, feline, and bovine animals, some but not all facing the male figure, as well as a human riding a dolphin. Between the antlers of the god is an unknown motif, possibly a plant or a tree, but most likely just the standard background decoration.

*On plate B, the large bust of a torc-wearing female is flanked by two six-spoke

A spoke is one of some number of rods radiating from the center of a wheel (the hub where the axle connects), connecting the hub with the round traction surface.

The term originally referred to portions of a log that had been riven (split l ...

d wheels, what seem to be two elephants, and two griffins. A feline or hound is underneath the bust. In northwest Gaulish coinage from 150 to 50 BC, such wheels often indicate a chariot, so the scene could be seen as a goddess in an elephant biga (Olmsted 1979; 2001: 125–126).

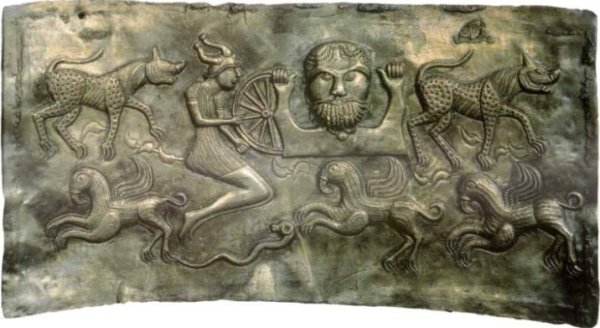

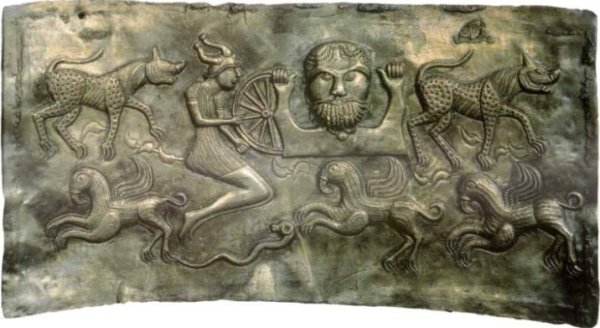

*The large bust of a bearded figure holding on to a broken wheel is at the centre of plate C. A smaller, leaping figure with a horned helmet

Horned helmets were worn by many people around the world. Headpieces mounted with animal horns or replicas were also worn from ancient times, as in the Mesolithic Star Carr. These were probably used for religious ceremonial or ritual purposes, ...

is also holding the rim of the wheel. Under the leaping figure is a horned serpent. The group is surrounded by three griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late Latin, Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail ...

s facing left below, and above, two strange animals who look like hyena

Hyenas, or hyaenas (from Ancient Greek , ), are feliform carnivoran mammals of the family Hyaenidae . With only four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the Carnivora and one of the smallest in the clas ...

s, facing right. The wheel's spokes are rendered asymmetrically, but judging from the lower half, the wheel may have had twelve spokes.

*Plate D depicts a bull-slaying scene, with the same composition repeated three times across the plate; the only place where such repetition appears on the cauldron. Three large bulls are arranged in a row, facing right, and each of them is attacked by a man with a sword. A feline and a dog, both running to the left, appear respectively over and below each bull. After the Stowe version of the "Tain", Medb's men run forward to kill the Donn bull after his fight with Medb's "white-horned" bull, whom he kills.

*On the lower half of plate E, a line of warrior

A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracies, class, or caste.

History

Warriors seem to have been p ...

s bearing spears and shields march to the left with, bringing up the rear a warrior with no shield, a sword, and a boar-crested helmet that resembles helmets from later Germanic cultures. Behind him are three carnyx

The ancient carnyx was a wind instrument of the Iron Age Celts, used between c. 200 BC and c. AD 200. It was a type of bronze trumpet with an elongated S shape, held so that the long straight central portion was vertical and the short mouthpiec ...

players. In front of this group a dog leaps up, perhaps holding them back. Behind the dog, at the left side of the scene, a figure over twice the size of the others holds a man upside down, apparently with ease, and apparently is about to immerse him in a barrel or cauldron. On the upper half, warriors on horseback with crested helmets and spears ride away to the right, with at the right a horned serpent, fitted in above the tops of the carnyxes, who is perhaps leading them. The two lines are below and above what appears to be a tree, still in leaf, lying sideways. This is now most often interpreted as a scene where fallen warriors are dipped into a cauldron to be reborn into their next life, or afterlife. This can be paralleled in later Welsh literature.

carnyx

The ancient carnyx was a wind instrument of the Iron Age Celts, used between c. 200 BC and c. AD 200. It was a type of bronze trumpet with an elongated S shape, held so that the long straight central portion was vertical and the short mouthpiec ...

players

Interpretation and parallels

Bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

4th-century BC buffer-type Celtic torc

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some had hook and ring closures and a few had ...

from France

File:CarnyxDeTintignac2.jpg, Carnyx head from the recently discovered Tintignac

Tintignac is a hamlet near Naves in the Corrèze region of France. It is primarily known for the archaeological remains of a sanctuary where Gallic and Gallo-Roman artefacts have been found, including seven carnyces (war trumpets) and ornamented ...

group

File:Museum of ScotlandDSCF6355.jpg, Torrs Pony-cap and Horns

The Torrs Horns and Torrs Pony-cap (once together known as the Torrs Chamfrein) are Iron Age bronze pieces now in the National Museum of Scotland, which were found together, but whose relationship is one of many questions about these "famous and ...

File:Celtic Helmet from Satu Mare, Romania.jpg, Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

helmet from Satu Mare

Satu Mare (; hu, Szatmárnémeti ; german: Sathmar; yi, סאטמאר or ) is a city with a population of 102,400 (2011). It is the capital of Satu Mare County, Romania, as well as the centre of the Satu Mare metropolitan area. It lies in the ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

with raven

A raven is any of several larger-bodied bird species of the genus ''Corvus''. These species do not form a single taxonomic group within the genus. There is no consistent distinction between "crows" and "ravens", common names which are assigned t ...

crest, around 4th century BC

File:Letnitsa treasure.png, Thracian plaque with the Thracian horseman

The Thracian horseman (also "Thracian Rider" or "Thracian Heros") is a recurring motif depicted in reliefs of the Hellenistic and Roman periods in the Balkans—mainly Thrace, Macedonia, Thessaly and Moesia—roughly from the 3rd century BC to ...

File:Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, schatten uit Limburg, sierschijf van Helden 1.JPG, Thracian disc found in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

File:Cylinder Seal, Achaemenid, modern impression 05.jpg, Achaemenid

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

seal impression with Master of Animals motif; the Persian king subduing two Mesopotamian lamassu

''Lama'', ''Lamma'', or ''Lamassu'' (Cuneiform: , ; Sumerian: lammař; later in Akkadian: ''lamassu''; sometimes called a ''lamassus'') is an Assyrian protective deity.

Initially depicted as a goddess in Sumerian times, when it was called ''La ...

File:Chalice-crater Louvre CA491.jpg, Griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late Latin, Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail ...

on an Ancient Greek vase

Ancient Greek pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it (over 100,000 painted vases are recorded in the Corpus vasorum antiquorum), it has exe ...

For many years, some scholars have interpreted the cauldron's images in terms of the

For many years, some scholars have interpreted the cauldron's images in terms of the Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

pantheon, and Celtic mythology

Celtic mythology is the body of myths belonging to the Celtic peoples.Cunliffe, Barry, (1997) ''The Ancient Celts''. Oxford, Oxford University Press , pp. 183 (religion), 202, 204–8. Like other Iron Age Europeans, Celtic peoples followed a ...

as it is presented in much later literature in Celtic languages

The Celtic languages ( usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward ...

from the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

. Others regard the latter interpretations with great suspicion. Much less controversially, there are clear parallels between details of the figures and Iron Age Celtic artefacts excavated by archaeology.

Other details of the iconography clearly derive from the art of the ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

, and there are intriguing parallels with ancient India and later Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

deities and their stories. Scholars are mostly content to regard the former as motifs borrowed purely for their visual appeal, without carrying over anything much of their original meaning, but despite the distance some have attempted to relate the latter to wider traditions remaining from Proto-Indo-European religion

Proto-Indo-European mythology is the body of myths and deities associated with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the hypothetical speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language. Although the mythological motifs are not directly attested � ...

.

Celtic archaeology

Among the most specific details that are clearly Celtic are the group ofcarnyx

The ancient carnyx was a wind instrument of the Iron Age Celts, used between c. 200 BC and c. AD 200. It was a type of bronze trumpet with an elongated S shape, held so that the long straight central portion was vertical and the short mouthpiec ...

players. The carnyx war horn was known from Roman descriptions of the Celts in battle and Trajan's Column

Trajan's Column ( it, Colonna Traiana, la, Columna Traiani) is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, that commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision of the architect Ap ...

, and a few pieces are known from archaeology, their number greatly increased by finds at Tintignac

Tintignac is a hamlet near Naves in the Corrèze region of France. It is primarily known for the archaeological remains of a sanctuary where Gallic and Gallo-Roman artefacts have been found, including seven carnyces (war trumpets) and ornamented ...

in France in 2004. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

wrote around 60–30 BC (Histories, 5.30):

:''"Their trumpets again are of a peculiar barbarian kind; they blow into them and produce a harsh sound which suits the tumult of war''"

Another detail that is easily matched to archaeology is the torc

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some had hook and ring closures and a few had ...

worn by several figures, clearly of the "buffer" type, a fairly common Celtic artefact found in Western Europe, most often France, from the period the cauldron is thought to have been made.

Other details with more tentative Celtic links are the long swords carried by some figures, and the horned and antlered helmets or head-dresses and the boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The species is no ...

crest worn on their helmet by some warriors. These can be related to Celtic artefacts such as a helmet with a raptor

Raptor or RAPTOR may refer to:

Animals

The word "raptor" refers to several groups of bird-like dinosaurs which primarily capture and subdue/kill prey with their talons.

* Raptor (bird) or bird of prey, a bird that primarily hunts and feeds on ...

crest from Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, the Waterloo Helmet

The Waterloo Helmet (also known as the Waterloo Bridge Helmet) is a pre-Roman Celtic bronze ceremonial horned helmet with repoussé decoration in the La Tène style, dating to circa 150–50 BC, that was found in 1868 in the River Thames by W ...

, Torrs Pony-cap and Horns

The Torrs Horns and Torrs Pony-cap (once together known as the Torrs Chamfrein) are Iron Age bronze pieces now in the National Museum of Scotland, which were found together, but whose relationship is one of many questions about these "famous and ...

and various animal figures including boars, of uncertain function. The shield bosses, spurs and horse harness also relate to Celtic examples.

The antlered figure in plate A has been commonly identified as

The antlered figure in plate A has been commonly identified as Cernunnos

In ancient Celtic and Gallo-Roman religion, Cernunnos or Carnonos was a god depicted with antlers, seated cross-legged, and is associated with stags, horned serpents, dogs and bulls. He is usually shown holding or wearing a torc and somet ...

, who is named (the only source for the name) on the 1st-century Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context ...

Pillar of the Boatmen

The Pillar of the Boatmen (french: Pilier des nautes) is a monumental Roman column erected in Lutetia (modern Paris) in honour of Jupiter by the guild of boatmen in the 1st century AD. It is the oldest monument in Paris and is one of the earliest ...

, where he is shown as an antlered figure with torcs hanging from his antlers. Possibly the lost portion below his bust showed him seated cross-legged as the figure on the cauldron is. Otherwise there is evidence of a horned god

The Horned God is one of the two primary deities found in Wicca and some related forms of Neopaganism.

The term ''Horned God'' itself predates Wicca, and is an early 20th-century syncretic term for a horned or antlered anthropomorphic god partl ...

from several cultures.

The figure holding the broken wheel in plate C is more tentatively thought to be Taranis

In Celtic mythology, Taranis (Proto-Celtic: *''Toranos'', earlier ''*Tonaros''; Latin: Taranus, earlier Tanarus) is the god of thunder, who was worshipped primarily in Gaul, Hispania, Britain, and Ireland, but also in the Rhineland and Danube r ...

, the solar or thunder "wheel-god" named by Lucian

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer

Pamphleteer is a historical term for someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (and therefore ...

and represented in a number of Iron Age images; there are also many wheels that seem to have been amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects ...

s.

Near East and Asia

The many animals depicted on the cauldron includeelephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae an ...

s, a dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

, leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant species in the genus '' Panthera'', a member of the cat family, Felidae. It occurs in a wide range in sub-Saharan Africa, in some parts of Western and Central Asia, Southern Russia, a ...

-like felines, and various fantastic animals, as well as animals that are widespread across Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

, such as snakes, cattle, deer, boars and birds. Celtic art

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and styli ...

often includes animals, but not often in fantastic forms with wings and aspects of different animals combined. There are exceptions to this, some when motifs are clearly borrowed, as the boy riding a dolphin is borrowed from Greek art, and others that are more native, like the ram-headed horned snake who appears three times on the cauldron.Green, 135–139 The art of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

often shows animals, most often powerful and fierce ones, many of which are also very common in the ancient Near East, or the Scythian art

Scythian art is the art associated with Scythian cultures, primarily decorative objects, such as jewellery, produced by the nomadic tribes of the area known as Scythia, which encompassed Central Asia, parts of Eastern Europe east of the Vistula Ri ...

of the Eurasian steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Transnistri ...

, whose mobile owners provided a route for the very rapid transmission of motifs and objects between the civilizations of Asia and Europe.

In particular, the two figures standing in profile flanking the large head on exterior plate F, each with a bird with outstretched wings just above their head clearly resemble a common motif in ancient Assyrian

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

and Persian art

Persian art or Iranian art () has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences f ...

, down to the long garments they wear. Here the figure is usually the ruler, and the wings belong to a symbolic representation of a deity protecting him. Other plates show griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late Latin, Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail ...

s borrowed from Ancient Greek art of that of the Near East. On several of the exterior plates the large heads, probably of deities, in the centre of the exterior panels, have small arms and hands, either each grasping an animal or human in a version of the common Master of Animals motif, or held up empty at the side of the head in a way suggesting inspiration from this motif.

Celtic mythology

Apart from Cernunnos and Taranis, discussed above, there is no consensus regarding the other figures, and many scholars reject attempts to tie them in to figures known from much later and geographically distant sources. Some Celticists have explained the elephants depicted on plate B as a reference toHannibal's crossing of the Alps

Hannibal's crossing of the Alps in 218 BC was one of the major events of the Second Punic War, and one of the most celebrated achievements of any military force in ancient warfare.Lancel, Serge, ''Hannibal'', p71/ref> Hannibal managed to l ...

.

Because of the double-headed wolfish monster attacking the two small figures of fallen men on plate b, parallels can be drawn to the Welsh character Manawydan

Manawydan fab Llŷr is a figure of Welsh mythology, the son of Llŷr and the brother of Brân the Blessed and Brânwen. The first element in his name is cognate with the stem of the name of the Irish sea god Manannán mac Lir, and likely originate ...

or the Irish Manannán, a god of the sea and the Otherworld. Another possibility is the Gaulish version of Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

, who was not only a warrior, but one associated with springs and healing besides.Olmsted, Garrett S (1979), "The Gundestrup cauldron : its archaeological context, the style and iconography of its portrayed motifs and their narration of a Gaulish version of Táin Bó Cúailnge", ''Collection Latomus 162'' atomus: Bruxelle 1979

Olmsted relates the scenes of the cauldron to those of the Táin Bó Cuailnge, where the antlered figure is Cú Chulainn

Cú Chulainn ( ), called the Hound of Ulster (Irish: ''Cú Uladh''), is a warrior hero and demigod in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology, as well as in Scottish and Manx folklore. He is believed to be an incarnation of the Irish god Lugh, ...

, the bull of the base plate is Donn Cuailnge

In the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology Donn Cúailnge, the Brown Bull of Cooley, was an extremely fertile stud bull over whom the Táin Bó Cúailnge (Cattle Raid of Cooley) was fought.

Prologue

A ninth century ''rémscéla'' or foretale recount ...

, and the female and two males of plate e are Medb

Medb (), later spelled Meadhbh (), Méibh () and Méabh (), and often anglicised as Maeve ( ), is queen of Connacht in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. Her husband in the core stories of the cycle is Ailill mac Máta, although she had seve ...

, Ailill

Ailill (Ailell, Oilioll) is a male name in Old Irish. It is a prominent name in Irish mythology, as for Ailill mac Máta, King of Connacht and husband of Queen Medb, on whom Shakespeare based the Fairy Queen Mab. Ailill was a popular given name in ...

, and Fergus mac Róich

Fergus mac Róich (literally " manliness, son of great stallion") is a character in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. Formerly the king of Ulster, he is tricked out of the kingship and betrayed by Conchobar mac Nessa, becomes the ally and lo ...

. Olmsted also toys with the idea that the female figure flanked by two birds on plate f could be Medb with her pets or Morrígan, the Irish war goddess who often changes into a carrion bird. Olmsted (1979, 1994) sees Cernunnos as Gaulish version of Irish Cu Chulainn. As Olmsted (1979) indicates, the scene on the upper right of plate A, a lion, a boy on a dolphin, and a bull, can be interpreted after the origin of the bulls of the Irish "Tain", who take on similar animal forms, fighting each other in each form, as indicated in the two lions fighting on the lower right of plate A.

Plate B could be interpreted after a Gaulish version of the beginning of the Irish "Tain", where Medb sets out to get the Donn bull after making a circuit around her army in her chariot to bring luck to the "Tain".

Olmsted (1979) interprets the scene on Plate C as a Gaulish version of the Irish Tain incidents where Cu Chulainn kicks in the Morrigan's ribs when she comes at him as an eel and then confronts Fergus with his broken chariot wheel.

Olmsted (1979) interprets the scene with warriors on the lower part of Plate "E" as a Gaulish version of the "Aided Fraich" episode of the "Tain" where Fraech and his men leap over the fallen tree, and then Fraech wrestles with his father Cu Chulainn and is drowned by him, while his magic horn blowers play "the music of sleeping" against Cu Chulainn. In the "Aided Fraich" episode, Fraech's body is then taken into the underworld by weeping ''banchuire'' to be healed by his aunt and wife Morrigan. This incident is depicted on outer plate f, which is adjacent and opposite to plate E.

Both Olmsted and Taylor agree that the female of plate f might be Rhiannon

Rhiannon is a major figure in the Mabinogi, the medieval Welsh story collection. She appears mainly in the First Branch of the Mabinogi, and again in the Third Branch. She is a strong-minded Otherworld woman, who chooses Pwyll, prince of Dyfe ...

of the Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () are the earliest Welsh prose stories, and belong to the Matter of Britain. The stories were compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, create ...

. Rhiannon is famous for her birds, whose songs could "awaken the dead and lull the living to sleep". In this role, Rhiannon could be considered the Goddess of the Otherworld.

Taylor presents a more pancultural view of the cauldron's images; he concludes that the deities and scenes portrayed on the cauldron are not specific to one culture, but many. He compares Rhiannon, whom he thinks is the figure of plate f, with Hariti

Hārītī (Sanskrit), also known as , ja, text=鬼子母神, translit=Kishimojin, is both a revered goddess and demon, depending on the Buddhist tradition. She is one of the Twenty-Four Protective Deities of Mahayana Buddhism.

In her posit ...

, an ogress of Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

n mythology. In addition, he points to the similarity between the female figure of plate B and the Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

goddess Lakshmi

Lakshmi (; , sometimes spelled Laxmi, ), also known as Shri (, ), is one of the principal goddesses in Hinduism. She is the goddess of wealth, fortune, power, beauty, fertility and prosperity, and associated with ''Maya'' ("Illusion"). Alo ...

, whose depictions are often accompanied by elephants. Wheel gods are also cross-cultural with deities like Taranis and Vishnu

Vishnu ( ; , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.

Vishnu is known as "The Preserver" within t ...

, a god from Hinduism.

See also

* Celtic polytheism *Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

* Pashupati seal

*Gutasaga

Gutasaga (''Gutasagan'') is a saga regarding the history of Gotland before its Christianization. It was recorded in the 13th century and survives in only a single manuscript, the Codex Holm. B 64, dating to , kept at the National Library of Sweden ...

Notes

References

* Green, Miranda, ''Celtic Art, Reading the Messages'', 1996, The Everyman Art Library, * Koch, John ed., "Gundestrup cauldron" in ''Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia'', 2006, ABC-CLIO, , 9781851094400google books

*"Laings", Lloyd Laing and Jennifer Laing. ''Art of the Celts: From 700 BC to the Celtic Revival'', 1992, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), *"Megaws" = Megaw, Ruth and Vincent, ''Celtic Art'', 1989, Thames and Hudson, *"NMD"

"The Gundestrup Cauldron"

National Museum of Denmark

The National Museum of Denmark (Nationalmuseet) in Copenhagen is Denmark's largest museum of cultural history, comprising the histories of Danish and foreign cultures, alike. The museum's main building is located a short distance from Strøget ...

, web section, accessed on 1 February 2016

*Olmsted, Garrett (2001), "Celtic Art in Transition during the First Century BC", ''Archaeolingua'': Volume 12: 2001: .

*Sandars, Nancy K., ''Prehistoric Art in Europe'', Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art), 1968 (nb 1st edn.)

Further reading

*Kaul, Fleming (ed), ''Thracian Tales on the Gundestrup Cauldron'', 1991, Najade Press, , 9789073835016 *Garrett S. Olmsted, ''The Gods of the Celts and the Indo-Europeans'', Inndbrucker Beitrage zur Kulterwissenschaft: Volume 92: 1994: , 97890738350162019 revised version

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gundestrup Cauldron 2nd-century BC works 1st-century BC works 1891 archaeological discoveries Archaeological discoveries in Denmark Germanic archaeological artifacts Celtic art Pre-Roman Iron Age Thracian archaeological artifacts Silver objects Treasure troves in Denmark Dogs in art Deer in art Cattle in art Cauldrons Magic items Ancient art in metal