Greyfriars Kirk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Greyfriars Kirk ( gd, Eaglais nam Manach Liath) is a

The congregation of Greyfriars can trace its origin to a 1584 edict of the town council to divide Edinburgh into four parishes. This created a south-west parish with the intention it would meet in the central section of St Giles'. This edict does not appear to have been enforced until 1598, when the south-west parish was allocated to the Upper Tolbooth partition at the west end of St Giles'.

The congregation of Greyfriars can trace its origin to a 1584 edict of the town council to divide Edinburgh into four parishes. This created a south-west parish with the intention it would meet in the central section of St Giles'. This edict does not appear to have been enforced until 1598, when the south-west parish was allocated to the Upper Tolbooth partition at the west end of St Giles'.

The events of 23 July mirrored a similar incident and riot at St Giles' on the same day. Resistance to Charles and

The events of 23 July mirrored a similar incident and riot at St Giles' on the same day. Resistance to Charles and

During the restoration of Old Greyfriars under

During the restoration of Old Greyfriars under

Greyfriars is set among

Greyfriars is set among

Internally, octagonal pillars bear parallel arcades of chamfered pointed arches that run along eight bays; these are interrupted only by a lateral arch that divides the western two bays from the rest of the church. The aisles of these bays are partitioned off to form rooms and the arch frames the

Internally, octagonal pillars bear parallel arcades of chamfered pointed arches that run along eight bays; these are interrupted only by a lateral arch that divides the western two bays from the rest of the church. The aisles of these bays are partitioned off to form rooms and the arch frames the

At its completion, the church consisted of an

At its completion, the church consisted of an

The current three-manual

The current three-manual

Richard Frazer has been minister of Greyfriars since 2003. He was ordained as a minister in 1986 and previously served as minister of St Machar's Cathedral,

Richard Frazer has been minister of Greyfriars since 2003. He was ordained as a minister in 1986 and previously served as minister of St Machar's Cathedral,

parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

, located in the Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

of Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. It is surrounded by Greyfriars Kirkyard

Greyfriars Kirkyard is the graveyard surrounding Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is located at the southern edge of the Old Town, adjacent to George Heriot's School. Burials have been taking place since the late 16th century, and a num ...

.

Greyfriars traces its origin to the south-west parish of Edinburgh, founded in 1598. Initially, this congregation met in the western portion of St Giles'. The church is named for the Observantine Franciscans or "Grey Friars" who arrived in Edinburgh from the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

in the mid-15th century and were granted land for a Friary

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whic ...

at the south-western edge of the burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Bur ...

. In the wake of the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

, the grounds of the abandoned Friary were repurposed as a cemetery

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite or graveyard is a place where the remains of dead people are buried or otherwise interred. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek , "sleeping place") implies that the land is specifically designated as a bu ...

, in which the current church was constructed between 1602 and 1620. In 1638, National Covenant

The National Covenant () was an agreement signed by many people of Scotland during 1638, opposing the proposed reforms of the Church of Scotland (also known as '' The Kirk'') by King Charles I. The king's efforts to impose changes on the church ...

was signed in the Kirk. The church was damaged during the Protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

, when it was used as barracks by troops under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

. In 1718, an explosion destroyed the church tower. During the reconstruction, the church was partitioned to hold two congregations: Old Greyfriars and New Greyfriars. In 1845, fire ravaged Old Greyfriars. After its reconstruction, the minister, Robert Lee, introduced the first organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

and stained glass

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

windows in a Scottish parish church since the Reformation. In 1929, Old and New Greyfriars united and the church was restored as one sanctuary. In the following years, the depopulation of the Old Town saw Greyfriars unite with a number of neighbouring congregations.

The church of Greyfriars is a simple aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, pa ...

d nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

of eight bays

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a na ...

; the style is Survival Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

fused with Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

elements. The church initially consisted of six bays and a west tower. After the explosion of 1718 destroyed the tower, Alexander McGill added two new bays and a Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

north porch to create one building divided into two churches of four bays each. After it was gutted by fire in 1845, David Cousin

David Cousin (19 May 1809 – 14 August 1878) was a Scottish architect, landscape architect and planner, closely associated with early cemetery design and many prominent buildings in Edinburgh. From 1841 to 1872 he operated as Edinburgh’s ...

rebuilt Old Greyfriars with an open, un-aisled interior. Between 1932 and 1938, the interior and arcades were restored by Henry F. Kerr. Notable features of the church include historic stained glass windows by James Ballantine; the 17th century monument to Margaret, Lady Yester; and an original copy of the National Covenant of 1638.

Since the 18th century, the congregations of Greyfriars have been notable for their missionary work within the parish. This continues to the present day through the church's work with the Grassmarket Community Project and the Greyfriars Charteris Centre. Greyfriars holds weekly Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, an ...

services, maintaining a tradition of Gaelic worship in Edinburgh that goes back to the beginning of the 18th century.

History

Edinburgh's Grey Friars

Observatine Franciscans first came to Scotland in 1447 at the invitation ofJames I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

. The six friars, including one Scot, arrived from the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

under the leadership of Cornelius of Zierikzee

Zierikzee () is a small city in the southwest Netherlands, 50 km southwest of Rotterdam. It is situated in the municipality of Schouwen-Duiveland, Zeeland. The city hall of Schouwen-Duiveland is located in Zierikzee, its largest city. Zieri ...

. They settled at the corner of the Grassmarket

The Grassmarket is a historic market place, street and event space in the Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. In relation to the rest of the city it lies in a hollow, well below surrounding ground levels.

Location

The Grassmarket is located direct ...

and Candlemaker Row in either 1453 or 1458. In 1464, the Provost of St Giles' granted the Chapel of St John outwith the West Port to Friar Crannok, Warden of the Grey Friars. The fate of this Chapel is unknown.Bryce 1912, p. 11.

The Friary enjoyed royal patronage and connections: it hosted Mary of Guelders

Mary of Guelders (; c. 1434/1435 – 1 December 1463) was Queen of Scotland by marriage to King James II of Scotland. She ruled as regent of Scotland from 1460 to 1463.

Background

She was the daughter of Arnold, Duke of Guelders, and Cath ...

on her arrival in Edinburgh in 1449 and sheltered Henry VI of England

Henry VI (6 December 1421 – 21 May 1471) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. The only child of Henry V, he succeeded to the English throne ...

during his exile. James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

was particularly close to the Edinburgh Grey Friars: he appointed himself the Observatines' "Royal Protector" and Friar Ranny, Warden of the Edinburgh Grey Friars, served as the King's confessor

Confessor is a title used within Christianity in several ways.

Confessor of the Faith

Its oldest use is to indicate a saint who has suffered persecution and torture for the faith but not to the point of death.Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

in 1558: Reformers stole the statue of Saint Giles

Saint Giles (, la, Aegidius, french: Gilles), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 6th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly lege ...

from the burgh church and the Greyfriars loaned their statue of the saint for use in the Saint Giles' Day procession on 1 September that year. The statue was damaged when Reformers broke up the procession.Bryce 1912, p. 25. When news reached Edinburgh of the advance of the Lords of the Congregation

The Lords of the Congregation (), originally styling themselves "the Faithful", were a group of Protestant Scottish nobles who in the mid-16th century favoured a reformation of the Catholic church according to Protestant principles and a Scot ...

on 28 June 1559, Lord Seton

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or a ...

, Provost of Edinburgh

The Right Honourable Lord Provost of Edinburgh is the convener of the City of Edinburgh local authority, who is elected by the city council and serves not only as the chair of that body, but as a figurehead for the entire city, ex officio the ...

, abandoned his commitment to protect the Grey Friars, leaving their Friary to be ransacked by a mob. The friars sheltered among their allies in the city.Bryce 1912, p. 26. In the summer of 1560, Scotland's Observantine Franciscans, including all but one or two of the Edinburgh Grey Friars, left the country for the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

: these exiles numbered about eighty friars and were led by the Provincial Minister, John Patrick.

Beginnings

By 1565, all the buildings of the Friary had been removed and their stones carried away for use in the construction of the New Tolbooth and to repair St Giles' and its kirkyard walls.Bryce 1912, p. 30. Thekirkyard

In Christian countries a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster-Scots, this can also ...

of St Giles' was, by then, overcrowded and Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

had, in 1562, given the grounds of the Friary to the town council

A town council, city council or municipal council is a form of local government for small municipalities.

Usage of the term varies under different jurisdictions.

Republic of Ireland

Town Councils in the Republic of Ireland were the second ti ...

to use as a burial ground.Dunlop 1988, p. 74.

The congregation of Greyfriars can trace its origin to a 1584 edict of the town council to divide Edinburgh into four parishes. This created a south-west parish with the intention it would meet in the central section of St Giles'. This edict does not appear to have been enforced until 1598, when the south-west parish was allocated to the Upper Tolbooth partition at the west end of St Giles'.

The congregation of Greyfriars can trace its origin to a 1584 edict of the town council to divide Edinburgh into four parishes. This created a south-west parish with the intention it would meet in the central section of St Giles'. This edict does not appear to have been enforced until 1598, when the south-west parish was allocated to the Upper Tolbooth partition at the west end of St Giles'. Robert Rollock

Robert Rollock (c. 15558 or 9 February 1599) was Scottish academic and minister in the Church of Scotland, and the first regent and first principal of the University of Edinburgh. Born into a noble family, he distinguished himself during ...

and Peter Hewat

Peter Hewat (born 17 March 1978) is a former Australian rugby union player now coaching in Japan's Top League for Ricoh Black Rams. He previously played for the NSW Waratahs Central Coast Rays London Irish and Suntory Sungoliath. On 12 April ...

were appointed the first ministers.Dunlop 1988, p. 78.

By the end of the 16th century, St Giles' could no longer accommodate Edinburgh's growing population. In 1599, the town council had discussed and abandoned proposals to construct a new church in the grounds of Kirk o%27 Field

The Collegiate Church of St Mary in the Fields (commonly known as Kirk o' Field) was a pre-Reformation collegiate church in Edinburgh, Scotland. Likely founded in the 13th century and secularised at the Reformation, the church's site is now covered ...

(around modern-day Chambers Street). In 1601, the council decided to build a new church in the southern part of the Greyfriars burying ground. Construction commenced in 1611, using material from the Convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Angl ...

of Catherine of Siena

Catherine of Siena (Italian: ''Caterina da Siena''; 25 March 1347 – 29 April 1380), a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic, was a mystic, activist, and author who had a great influence on Italian literature and on the Catholic Church ...

at Sciennes

Sciennes (pronounced , ) is a district of Edinburgh, Scotland, situated approximately south of the city centre. It is a mainly residential district, although it is also well-known as the site of the former Royal Hospital for Sick Children. M ...

.

The Kirk was first used on 18 February 1619 for the funeral of the William Couper, Bishop of Galloway

The Bishop of Galloway, also called the Bishop of Whithorn, was the eccesiastical head of the Diocese of Galloway, said to have been founded by Saint Ninian in the mid-5th century. The subsequent Anglo-Saxon bishopric was founded in the late 7th ...

; John Spottiswoode, Archbishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews ( gd, Easbaig Chill Rìmhinn, sco, Beeshop o Saunt Andras) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews ( gd, Àrd-easbaig ...

, preached the funeral sermon.Bryce 1912, p. 40. Congregational worship was first held on Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

Day 1620.Steele 1993, p. 5. Though this was a Monday, the minister, Patrick Galloway

Patrick Galloway (c.1551 – 1626) was a Scottish minister, a Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. "The King wold needis have Mr Patrik Galloway to be his minister." He was Moderator of the General Assembly in 1590, and ...

, chose to hold the service on Christmas Day to curry favour with James VI

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, who disapproved of the radical Reformers' opposition to holy days.Steele 1993, p. 9.

Covenant and conflict

At the establishment of theDiocese of Edinburgh

The Diocese of Edinburgh is one of the seven dioceses of the Scottish Episcopal Church. It covers the City of Edinburgh, the Lothians, the Borders and Falkirk. The diocesan centre is St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh. The Bishop of Edinburgh i ...

in 1633, the ministers of Greyfriars were placed on the list of prebendaries

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

of St Giles%27 Cathedral

St Giles' Cathedral ( gd, Cathair-eaglais Naomh Giles), or the High Kirk of Edinburgh, is a parish church of the Church of Scotland in the Old Town of Edinburgh. The current building was begun in the 14th century and extended until the early 1 ...

. In 1637, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

attempted to impose a Service Book on the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

. On 23 July that year, James Fairlie read the new service book in Greyfriars: this caused a tumult, in which Fairlie exchanged curses with the women of the congregation.Bryce 1912, p. 52. Fairlie's colleague, Andrew Ramsay, refused to read the Service Book the following Sunday and was deposed by royal authority.Gray 1940, p. 34.Bryce 1912, p. 53.

The events of 23 July mirrored a similar incident and riot at St Giles' on the same day. Resistance to Charles and

The events of 23 July mirrored a similar incident and riot at St Giles' on the same day. Resistance to Charles and William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

's interference in the Scottish church resulted in the National Covenant

The National Covenant () was an agreement signed by many people of Scotland during 1638, opposing the proposed reforms of the Church of Scotland (also known as '' The Kirk'') by King Charles I. The king's efforts to impose changes on the church ...

. The Covenant was first read by Archibald Johnston of Warriston from the pulpit of Greyfriars; Scotland's nobility and gentry then signed the Covenant inside the church. Copies of the Covenant were carried throughout Edinburgh and Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

to be signed by the masses.Bryce 1912, p. 88. The formation and subsequent ascendancy of the Covenanters led to the Bishops%27 Wars

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars () were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland. Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First ...

, the first conflict of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bi ...

.

In 1650, as troops of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

approached Edinburgh, all able-bodied men of the town were ordered to assemble in the kirkyard. Cromwell took the city after the defeat of the Covenanters

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

at Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and gave its name to an ...

and, between 1650 and 1653, Cromwell's troops occupied the church as a cavalry barracks and caused significant damage.Steele 1993, p. 6.Gray 1940, p. 36. Cromwell himself may have preached in Greyfriars.Steele 1993, p. 11. In 1656, the church was divided by a partition wall in anticipation of the creation of two new parishes in Edinburgh; this never happened and the partition was removed in 1662.

In 1660, General Monck announced in Greyfriars his intention to march south in support of the Restoration. After the Restoration, episcopacy

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

was re-established in the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

: this led to a new period of rebellion for the Covenanters

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

. Robert Traill, the covenanting minister of Greyfriars, was forced into exile and Covenanters were imprisoned in a field adjoining the kirkyard after the Battle of Bothwell Brig

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

in 1679. After the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

, Presbyterian polity

Presbyterian (or presbyteral) polity is a method of church governance ("ecclesiastical polity") typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters, or elders. Each local church is governed by a body of elected elders usually called the session o ...

was re-established in the Church of Scotland. William Carstares, who had served as chaplain and adviser to William II, served as minister of Greyfriars between 1703 and 1707.Steele 1993, p. 11.

Destruction and reconstruction: 1718-1843

From 1706, thetown council

A town council, city council or municipal council is a form of local government for small municipalities.

Usage of the term varies under different jurisdictions.

Republic of Ireland

Town Councils in the Republic of Ireland were the second ti ...

used the tower at the west end of Greyfriars as a gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

store; this exploded at around 1.45 a.m. on Sunday, 7 May 1718, destroying the tower and severely damaging the west end of the church.RCAHMS 1951, p. 46. The congregation met in the chapel of George Heriot%27s School

George Heriot's School is a Scottish independent primary and secondary day school on Lauriston Place in the Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. In the early 21st century, it has more than 1600 pupils, 155 teaching staff, and 80 non-teaching staff. ...

and the "Lower Commonhall" of the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

while the church was repaired.Bryce 1912, pp. 135-136.

Alexander McGill oversaw repairs to the church. A new wall was erected to enclose the eastern four bays

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a na ...

within a month of the explosion. Two new bays were added to the west end: this created a church divided into two equal halves. The work was completed by 31 December 1722 and the costs were met by a local duty on ale

Ale is a type of beer brewed using a warm fermentation method, resulting in a sweet, full-bodied and fruity taste. Historically, the term referred to a drink brewed without hops.

As with most beers, ale typically has a bittering agent to bala ...

.Steele 1993, p. 7.Bryce 1912, p. 137. The following autumn, the town council ordered the formation of a new congregation to occupy the western half of the Kirk and William Robertson was elected its first minister: this was known Wester Greyfriars then as New Greyfriars.Dunlop 1988, p. 84. The original congregation met in the eastern half and became known as Old Greyfriars.Dunlop 1988, pp. 78-79. From the schools' foundations to the late 19th century, New Greyfriars contained lofts for the pupils of the Merchant Maiden Hospital

The Mary Erskine School, popularly known as "Mary Erskine's" or "MES", is an all-girls independent secondary school in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was founded in 1694 and has a roll of around 750 pupils. It is the sister school of the all-boys Stewa ...

and George Heriot%27s School

George Heriot's School is a Scottish independent primary and secondary day school on Lauriston Place in the Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. In the early 21st century, it has more than 1600 pupils, 155 teaching staff, and 80 non-teaching staff. ...

, who had moved from Old Greyfriars; after 1871, the pupils of George Watson%27s College

George Watson's College is a co-educational independent day school in Scotland, situated on Colinton Road, in the Merchiston area of Edinburgh. It was first established as a hospital school in 1741, became a day school in 1871, and was m ...

also attended services in the church.Dunlop 1988, p. 84.Steele 1993, p. 12.Bryce 1912, p. 138.

In 1840, St John's Church on Victoria Street was formed from the parish of Old Greyfriars; the minister of the second charge in Old Greyfriars, Thomas Guthrie

Thomas Guthrie FRSE (12 July 1803 – 24 February 1873) was a Scottish divine and philanthropist, born at Brechin in Angus (at that time also called Forfarshire). He was one of the most popular preachers of his day in Scotland, and was associat ...

, became the first minister of St John’s. At the Disruption of 1843

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

, John Sym, the minister Old Greyfriars, left to join the Free Church

A free church is a Christian denomination that is intrinsically separate from government (as opposed to a state church). A free church does not define government policy, and a free church does not accept church theology or policy definitions fro ...

; although many of his congregation left with him, all the elders remained.Steele 1993, p. 13.Bryce 1912, p. 145

Fire and the "Greyfriars Revolution"

On 19 January 1845, a boiler flue overheated, causing a fire that gutted Old Greyfriars and damaged the roof and furnishings of New Greyfriars. As it happened soon after theDisruption of 1843

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

, some suggested the fire was divine judgement on the established church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

. Hugh Miller

Hugh Miller (10 October 1802 – 23/24 December 1856) was a self-taught Scottish geologist and writer, folklorist and an evangelical Christian.

Life and work

Miller was born in Cromarty, the first of three children of Harriet Wright (''b ...

unsuccessfully argued the congregations should move to St John's Church on Victoria Street and leave Greyfriars as a scenic ruin. The majority of the town council

A town council, city council or municipal council is a form of local government for small municipalities.

Usage of the term varies under different jurisdictions.

Republic of Ireland

Town Councils in the Republic of Ireland were the second ti ...

's members had joined the Free Church and their attempts to frustrate the restoration were one of the reasons it ended up taking twelve years.Bryce 1912, p. 147. The congregation temporarily decamped to the Tolbooth Kirk.

During the restoration of Old Greyfriars under

During the restoration of Old Greyfriars under David Cousin

David Cousin (19 May 1809 – 14 August 1878) was a Scottish architect, landscape architect and planner, closely associated with early cemetery design and many prominent buildings in Edinburgh. From 1841 to 1872 he operated as Edinburgh’s ...

, painted glass was installed at the request of the minister, Robert Lee: this was the first coloured glass to be installed in a building of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

since the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

.Steele 1993, p. 8. After the church reopened in 1857, Lee embarked upon what became known as "the Greyfriars Revolution": he introduced a service book of his own devising and pioneered the practices of standing for praise, kneeling for worship, and saying prepared prayers.Gray 1940, p. 40 These practices were innovative in Scottish Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

and Lee temporarily desisted under pressure from the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the sovereign and highest court of the Church of Scotland, and is thus the Church's governing body.''An Introduction to Practice and Procedure in the Church of Scotland'' by A. Gordon McGillivray, ...

. Later, he resumed the practice of prepared prayers and installed a harmonium

The pump organ is a type of free-reed organ that generates sound as air flows past a vibrating piece of thin metal in a frame. The piece of metal is called a reed. Specific types of pump organ include the reed organ, harmonium, and melodeon. Th ...

in 1863 and an organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

in 1865. Lee died in 1868 before further action could be taken against him.Dunlop 1988, p. 79. Lee proved highly influential in the development of Presbyterian liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

: pipe organs, stained glass, prepared prayers, and standing for praise would all become common in the Church of Scotland during the decades after Lee's death.

20th and 21st centuries

In 1929, the congregations of Old and New Greyfriars united. Between 1932 and 1938, the whole church was restored by Henry F. Kerr and the wall that had divided the two congregations was removed.Dunlop 1988, p. 88. In 1938, the congregation of Lady Yester%27s Kirk united with Greyfriars; the congregation of the New North Church joined Greyfriars in 1941. On 28 February 1979, the congregation of Highland, Tolbooth, St John's united with Greyfriars and the new congregation adopted the name "Greyfriars, Tolbooth, and Highland Kirk". Initially, the congregation used both churches but it was decided in 1981 only to use Greyfriars. Since this union, Greyfriars has maintained the tradition of the Edinburgh's Highland congregation by hosting regularGaelic language

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historicall ...

services.Dunlop 1988, p. 106.

During the 1990s, a church museum was developed in a room in the western part of the church; this was refurbished in 2012. In 2013, Kirk o%27 Field Parish Church

The Greyfriars Charteris Centre is a community centre in the Southside, Edinburgh, Scotland, part of the mission of Greyfriars Kirk. The centre opened in 2016 and occupies the 20th century church buildings which became Kirk o' Field Parish Churc ...

united with Greyfriars and the congregation re-adopted the name "Greyfriars Kirk". Since 2016, the Kirk o' Field buildings have been used by the church as the Greyfriars Charteris Centre.Setting and kirkyard

Greyfriars is set among

Greyfriars is set among Greyfriars Kirkyard

Greyfriars Kirkyard is the graveyard surrounding Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is located at the southern edge of the Old Town, adjacent to George Heriot's School. Burials have been taking place since the late 16th century, and a num ...

, which is bounded to the north by the Grassmarket

The Grassmarket is a historic market place, street and event space in the Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. In relation to the rest of the city it lies in a hollow, well below surrounding ground levels.

Location

The Grassmarket is located direct ...

and to the east by Candlemaker Row. This is the same site given to the Observatine Franciscans during the reign of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

at the edge of the Old Town of Edinburgh. It was then a relatively open space: there were only two tenements at the eastern side of the grounds; now the north and east sides of the kirkyard are enclosed by buildings.Steele 1993, p. 5.Bryce 1912, p. 8. Prior to occupation by the friars, these lands had been owned by the family of the Tours of Inverleith since 1388; the friars' rights to the land were confirmed by James III in 1479.Bryce 1912, p. 9.

The southern and western walls of the Friary's grounds were strengthened between 1513 and 1515 to create part of the Flodden Wall

There have been several town walls around Edinburgh, Scotland, since the 12th century. Some form of wall probably existed from the foundation of the royal burgh in around 1125, though the first building is recorded in the mid-15th century, whe ...

.Bryce 1912, p. 18. At the creation of the burial ground in 1562, a gate was installed at the site of the current north gate of the kirkyard. Since the construction of the Kirk, a causewayed path has connected this to the Kirk's north door. The current gateway on Greyfriars Place opposite the junction of Candlemaker Row and George IV Bridge

George IV Bridge is an elevated street in Edinburgh, Scotland, and is home to a number of the city's important public buildings.

History

A bridge connecting the Royal Mile to the south was first suggested as early as 1817, but was first p ...

was added in 1624. Until 1591, burials were restricted to the northern half of the site; the Upper Yard, where the Kirk now stands, was held by the magistrates and wapinschaws were conducted there.

Architecture

Description

The current church is rectangular in plan, consisting of a singlenave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

of eight bays

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a na ...

with aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, pa ...

s along the whole length of the church on either side. The church's architectural style can be described as "Survival Gothic" – that is, Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It ...

that continued after the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

– fused with Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 152. The exterior walls of the church consist of harled

Harling is a rough-cast wall finish consisting of lime and aggregate, known for its rough texture. Many castles and other buildings in Scotland and Ulster have walls finished with harling. It is also used on contemporary buildings, where it pr ...

rubble

Rubble is broken stone, of irregular size, shape and texture; undressed especially as a filling-in. Rubble naturally found in the soil is known also as 'brash' (compare cornbrash)."Rubble" def. 2., "Brash n. 2. def. 1. ''Oxford English Dictionar ...

with ashlar

Ashlar () is finely dressed (cut, worked) stone, either an individual stone that has been worked until squared, or a structure built from such stones. Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, generally rectangular cuboid, mentioned by Vitruv ...

dressings.Historic Environment Scotland LB27018 The church is 162 feet (49 meters) long by 72 feet (22 meters) wide. Externally, each bay is divided by buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient buildings, as a means of providing support to act against the lateral (s ...

es, each of which is capped by a ball-topped obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

finial

A finial (from '' la, finis'', end) or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the apex of a dome, spire, towe ...

. The buttresses at each corner of the church rest diagonally. The roof rises steeply above the aisles to a short course of wall, above which the roof over the nave continues at a shallower pitch.RCAHMS 1951, p. 47.

Each bay, save the easternmost bays on either side and the westernmost on the south side, has a window. Most of these windows have been enlarged by lowering the sill

Sill may refer to:

* Sill (dock), a weir at the low water mark retaining water within a dock

* Sill (geology), a subhorizontal sheet intrusion of molten or solidified magma

* Sill (geostatistics)

* Sill (river), a river in Austria

* Sill plate, ...

s, which, in three cases, has resulted in the removal of a doorway below. In the third bay from the east on the south side, the remains of the former south doorway are visible. The western three windows on the north side and the westernmost window of the south side are simple lancets with no tracery

Tracery is an architectural device by which windows (or screens, panels, and vaults) are divided into sections of various proportions by stone ''bars'' or ''ribs'' of moulding. Most commonly, it refers to the stonework elements that support the ...

. All the windows of the western half of the church are clusters of lancet lights. The third window from the west on the south side holds three lights and intersecting tracery while, in the second window from the west on the same side, two lancet lights support a light in the shape of a mandorla.

In each of the middle two bays of the north side stands a round-arched doorway with a sculpted angel's head on the keystone. Above the westernmost of these two sits a late-Gothic niche

Niche may refer to:

Science

*Developmental niche, a concept for understanding the cultural context of child development

* Ecological niche, a term describing the relational position of an organism's species

*Niche differentiation, in ecology, the ...

bracket bearing the arms of Edinburgh. These north doors are enclosed by a large, pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

ed Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

porch

A porch (from Old French ''porche'', from Latin ''porticus'' "colonnade", from ''porta'' "passage") is a room or gallery located in front of an entrance of a building. A porch is placed in front of the facade of a building it commands, and form ...

in channelled masonry of three bays and two storeys. The ground level is entered by round-headed arches while three rectangular windows illuminate the upper storey.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 154. Internally, the upper storey of this porch contains two vestries

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquially ...

accessed by a wooden turnpike stair.

The east gable is surmounted by a Classical pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

whose ends and apex are topped by ball-topped obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

finial

A finial (from '' la, finis'', end) or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the apex of a dome, spire, towe ...

s. The pediment contains a small oculus Oculus (a term from Latin ''oculus'', meaning 'eye'), may refer to the following

Architecture

* Oculus (architecture), a circular opening in the centre of a dome or in a wall

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Oculus'' (film), a 2013 American s ...

. The main window is round-arched and consists of a cluster of five lancet lights while the lancet windows in the gable of either aisle hold three lancet lights. Between the apex of the central window and the pediment is a stone marked 1614, which shows the arms of Edinburgh. Below the central window stands the round-arched former doorway of the East church, now built-up.

The west end of the church takes the form of a Dutch gable

A Dutch gable or Flemish gable is a gable whose sides have a shape made up of one or more curves and has a pediment at the top. The gable may be an entirely decorative projection above a flat section of roof line, or may be the termination of a ...

; the pediment is almost identical to that of the east gable while curving skews crown the gables of the aisles. The central section of the east gable is supported by buttresses, which reach to the foot of the pediment. The central window is a large lancet of three lights with intersecting tracery

Tracery is an architectural device by which windows (or screens, panels, and vaults) are divided into sections of various proportions by stone ''bars'' or ''ribs'' of moulding. Most commonly, it refers to the stonework elements that support the ...

. The aisle gable windows hold two lights under "Y"-shaped tracery. Below the central window at the east end is a low, Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

-style semi-octagonal porch

A porch (from Old French ''porche'', from Latin ''porticus'' "colonnade", from ''porta'' "passage") is a room or gallery located in front of an entrance of a building. A porch is placed in front of the facade of a building it commands, and form ...

with a door in each of the three full faces and a pitched roof.

Internally, octagonal pillars bear parallel arcades of chamfered pointed arches that run along eight bays; these are interrupted only by a lateral arch that divides the western two bays from the rest of the church. The aisles of these bays are partitioned off to form rooms and the arch frames the

Internally, octagonal pillars bear parallel arcades of chamfered pointed arches that run along eight bays; these are interrupted only by a lateral arch that divides the western two bays from the rest of the church. The aisles of these bays are partitioned off to form rooms and the arch frames the organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

loft. In these two western bays, a plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "re ...

vault

Vault may refer to:

* Jumping, the act of propelling oneself upwards

Architecture

* Vault (architecture), an arched form above an enclosed space

* Bank vault, a reinforced room or compartment where valuables are stored

* Burial vault (enclosure ...

forms the ceiling while the eastern six bays are covered by a timber barrelled ceiling supported on timber shafts that rise from corbel

In architecture, a corbel is a structural piece of stone, wood or metal jutting from a wall to carry a superincumbent weight, a type of bracket. A corbel is a solid piece of material in the wall, whereas a console is a piece applied to the s ...

s in the wall above each pillar. A boss

Boss may refer to:

Occupations

* Supervisor, often referred to as boss

* Air boss, more formally, air officer, the person in charge of aircraft operations on an aircraft carrier

* Crime boss, the head of a criminal organization

* Fire boss, a ...

rests where each arch between corresponding shafts crosses the longitudinal rib

In vertebrate anatomy, ribs ( la, costae) are the long curved bones which form the rib cage, part of the axial skeleton. In most tetrapods, ribs surround the chest, enabling the lungs to expand and thus facilitate breathing by expanding the ches ...

; these depict emblems of Saint Andrew

Andrew the Apostle ( grc-koi, Ἀνδρέᾱς, Andréās ; la, Andrēās ; , syc, ܐܰܢܕ݁ܪܶܐܘܳܣ, ʾAnd’reʾwās), also called Saint Andrew, was an apostle of Jesus according to the New Testament. He is the brother of Simon Pete ...

, Saint Margaret, and each person of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 155.Steele 1993, p. 19.

Architectural history

The first church

Work on the church had commenced by 1602, when Clement Russell is described as "maister of wark to the Kirk begun in the buriell plaice". In that year, thetown council

A town council, city council or municipal council is a form of local government for small municipalities.

Usage of the term varies under different jurisdictions.

Republic of Ireland

Town Councils in the Republic of Ireland were the second ti ...

also ordered the removal of the buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient buildings, as a means of providing support to act against the lateral (s ...

es and doors of the Convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Angl ...

of Catherine of Siena

Catherine of Siena (Italian: ''Caterina da Siena''; 25 March 1347 – 29 April 1380), a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic, was a mystic, activist, and author who had a great influence on Italian literature and on the Catholic Church ...

at Sciennes

Sciennes (pronounced , ) is a district of Edinburgh, Scotland, situated approximately south of the city centre. It is a mainly residential district, although it is also well-known as the site of the former Royal Hospital for Sick Children. M ...

for use in the construction of the new church.Hay 1957, p. 45. Work appears to have continued in 1603 and 1604, when Patrick Cochrane is referenced as master of works. Thereafter, work appears to have stopped until the town council

A town council, city council or municipal council is a form of local government for small municipalities.

Usage of the term varies under different jurisdictions.

Republic of Ireland

Town Councils in the Republic of Ireland were the second ti ...

moved to recommence work in 1611; but only in December 1612 did they order construction to "gang forward with all convenient expeditioun". A date stone on the east gable is marled 1614 the north east pillar, now replaced, was recorded to have been marked 1613: these suggest significant progress had been made by these dates; however, the church only opened in 1620.Bryce 1912, p. 40.

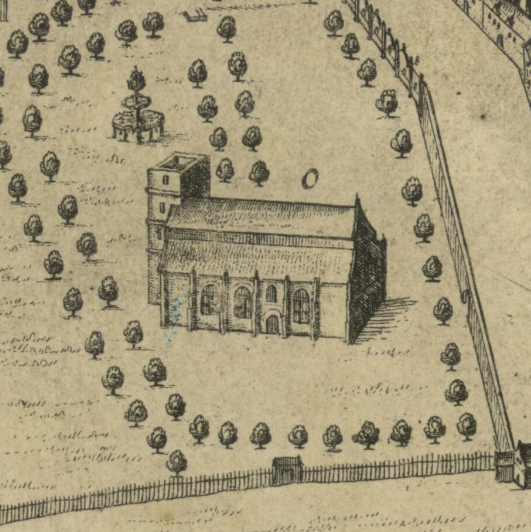

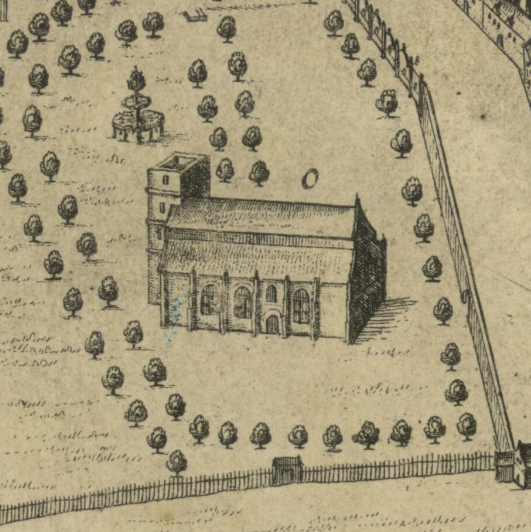

At its completion, the church consisted of an

At its completion, the church consisted of an aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, pa ...

d nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

of six bays

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a na ...

with external buttresses; a squat, square-based tower at the west end; and a curvilinear gable at the east end. Doors stood in the north, south, and east walls and probably in the exterior wall of the tower.Hay 1957, p. 46. Internally, the octagonal pillar

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member. ...

s may have evoked similar pillars in St Giles'. There were originally galleries on the east, west, and probably north sides to face the pulpit, which stood against the middle south pillar. The church was damaged during its occupation by the English Army

The ...

under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

and subsequently repaired. Between 1656 and 1662 a lateral partition wall divided the interior. The galleries were expanded in 1696.

Greyfriars was the first church built in Edinburgh since the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

and it was the largest post-Reformation church building in Scotland until well into the 18th century. According to George Hay, the form of an aisled nave, while "exceptional" in post-Reformation Scotland, did not represent a step back to pre-Reformation practices. The lack of a chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

...

reflected the communal emphasis of Reformed worship while the overall form was "the only formula then known in these islands for a large church".

Rebuilding after 1718

On 2 May 1718, the gunpowder store on the third and fourth floors of the tower ignited. A contemporary record by the Kirk's Session Clerk describes the explosion as having "…Rent the Western Gevell of the Church, broke all the glass windows, and turned the Sclates of the Church, and broke a great deal of the Leadden high roof of the Church". Thetown council

A town council, city council or municipal council is a form of local government for small municipalities.

Usage of the term varies under different jurisdictions.

Republic of Ireland

Town Councils in the Republic of Ireland were the second ti ...

's first step was to enclose the eastern four bays with a wall in which stood a turnpike stair. Galleries were then added to make up for lost space; the former north door was moved one bay east and its keystone was adorned with a carving of an angel's head; plaster ceilings, coombed in the aisles and barrel-vaulted

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

over the nave, were raised. In November 1719, the town council commissioned Alexander McGill to build a new church in the western half with Gilbert Smith as mason. McGill's plans effectively reversed the design of the existing church. The remains of the tower were demolished and two new bays were added to the west end of the damaged bays. This created spaces for two congregations: Old Greyfriars at the East and New Greyfriars at the West. Inside New Greyfriars, galleries on the north, south, and west sides faced a pulpit against the middle south pillar.

McGill created a Dutch gable

A Dutch gable or Flemish gable is a gable whose sides have a shape made up of one or more curves and has a pediment at the top. The gable may be an entirely decorative projection above a flat section of roof line, or may be the termination of a ...

with Classical pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

at the western end and, below this, added the semi-octagonal porch. He also replicated the north door in the bay immediately west. McGill added a near-identical pediment over the east gable and topped the pediments and buttresses with ball-topped obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

finials. In 1722, McGill added the Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

north porch to enclose the north doors; he also recast the curvilinear east gable, adding a Classical pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

to replicate the one at the west end.

Repairs after 1845

On the morning of Sunday, 19 January 1845, fire gutted Old Greyfriars, causing the partial collapse of the arcades and wrecking the furnishings of New Greyfriars.David Bryce

David Bryce FRSE FRIBA RSA (3 April 1803 – 7 May 1876) was a Scottish architect.

Life

Bryce was born at 5 South College Street in Edinburgh, the son of David Bryce (1763–1816) a grocer with a successful side interest in buildi ...

designed new furnishings for New Greyfriars: a tall wainscot

Panelling (or paneling in the U.S.) is a millwork wall covering constructed from rigid or semi-rigid components. These are traditionally interlocking wood, but could be plastic or other materials.

Panelling was developed in antiquity to make ro ...

was installed and north, south, east galleries now faced a canopied pulpit at the west end. New Greyfriars re-opened in 1846.

The restoration of Old Greyfriars took twelve years. Initially, James Smith was appointed architect but was responsible for little more than removing the roof and demolishing the remaining arcades. In 1856 and 1857, David Cousin

David Cousin (19 May 1809 – 14 August 1878) was a Scottish architect, landscape architect and planner, closely associated with early cemetery design and many prominent buildings in Edinburgh. From 1841 to 1872 he operated as Edinburgh’s ...

radically rebuilt Old Greyfriars. In the windows, he inserted ashlar

Ashlar () is finely dressed (cut, worked) stone, either an individual stone that has been worked until squared, or a structure built from such stones. Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, generally rectangular cuboid, mentioned by Vitruv ...

pierced by "Early English" lancet lights. He created a simple, triangular gable at the east end with a new lancet of three lights between the top of the central window and the apex of the gable. The arcades were not reconstructed, leaving an open interior covered by a single-span timber ceiling beneath a steeply pitched roof. In its time, Cousin's restoration of Old Greyfriars was "acclaimed as a sign that Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

had admitted Art as a handmaid of religion". Around the time of the 1930s restoration, however, Andrew Landale Drummond would criticise the "effect of bleak though ornate ugliness". A re-ordering of Old Greyfriars' interior was undertaken by Herbert Honeyman in 1912.

1932 onwards

The present appearance of the church dates from a restoration of 1932 to 1938 overseen by Henry F. Kerr. Kerr removed the partition wall to reunite the interior and reconstructed thearcade

Arcade most often refers to:

* Arcade game, a coin-operated game machine

** Arcade cabinet, housing which holds an arcade game's hardware

** Arcade system board, a standardized printed circuit board

* Amusement arcade, a place with arcade games

* ...

in the eastern four bays. He maintained the plaster vaulted ceiling over the two western bays and separated these from the rest of the church by a lateral arch.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 155. Over the remaining six bays, he installed a barreled ceiling of California redwood

''Sequoia sempervirens'' ()''Sunset Western Garden Book,'' 1995:606–607 is the sole living species of the genus '' Sequoia'' in the cypress family Cupressaceae (formerly treated in Taxodiaceae). Common names include coast redwood, coastal ...

.Dunlop 1988, p. 78. The woodwork of New Greyfriars was used to form a gallery under the western arch. In 1989, this was replaced by a new organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

loft, accessed by a staircase made from redundant pitch pine

''Pinus rigida'', the pitch pine, is a small-to-medium-sized pine. It is native to eastern North America, primarily from central Maine south to Georgia and as far west as Kentucky. It is found in environments which other species would find unsuit ...

pews.

Kerr replaced David Cousin

David Cousin (19 May 1809 – 14 August 1878) was a Scottish architect, landscape architect and planner, closely associated with early cemetery design and many prominent buildings in Edinburgh. From 1841 to 1872 he operated as Edinburgh’s ...

's pitched roof over Old Greyfriars with a two-stage roof in continuity with that over the western half of the church. He also recreated the pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

over the eastern gable.Features

Stained glass

The windows of the eastern four bays of the church are the oldest stained glass windows in aChurch of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

building: when they were added at the direction of Robert Lee in 1857, they were the first coloured windows in a Scottish parish church since the Reformation. These windows are effectively grisaille

Grisaille ( or ; french: grisaille, lit=greyed , from ''gris'' 'grey') is a painting executed entirely in shades of grey or of another neutral greyish colour. It is particularly used in large decorative schemes in imitation of sculpture. Many g ...

with abstract patterning except the east window, which also incorporates medallions depicting the Prodigal Son, the Wise and Foolish Virgins, the Good Samaritan, and the Pharisee and the Publican. Windows of this period commemorate John Erskine, Robert Traill, George Buchanan

George Buchanan ( gd, Seòras Bochanan; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth century Scotland produced." ...

, William Robertson, and John Inglis. These windows were all executed by Ballantine and Allen except the Anderson memorial window in the north aisle, which is by Francis Barnett.Steele 1993, p. 21.Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 155.

Further west along the south aisle, the Saint John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

window was removed from Highland, Tolbooth, St John's in 1979. It had been presented there in 1945 by David Young Cameron

Sir David Young Cameron (28 June 1865 – 16 September 1945) was a Scottish painter and, with greater success, etcher, mostly of townscapes and landscapes in both cases. He was a leading figure in the final decades of the Etching Reviv ...

to commemorate St John's Church. Next to this is a window by Marjorie Kemp in memory of Helen Pearl Gardiner; this depicts Saint Helen and Saint Margaret. The central window of the west end shows the morning of the Resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. In a number of religions, a dying-and-rising god is a deity which dies and is resurrected. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions, whic ...

; it was executed by Ballantine and Gardiner in 1898.Steele 1993, p. 23. A millennium window depicting an abstract Celtic cross

The Celtic cross is a form of Christian cross featuring a nimbus or ring that emerged in Ireland, France and Great Britain in the Early Middle Ages. A type of ringed cross, it became widespread through its use in the stone high crosses e ...

was designed by Douglas Hogg and added in 2000.

Organs

The current three-manual

The current three-manual organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

stands at the west end of the church and was built by Peter Collins of Melton Mowbray

Melton Mowbray () is a town in Leicestershire, England, north-east of Leicester, and south-east of Nottingham. It lies on the River Eye, known below Melton as the Wreake. The town had a population 27,670 in 2019. The town is sometimes promo ...

in 1989.Steele 1993, p. 16. The organ possesses almost 3,400 pipes, which are arranged in towering cases with trumpets '' en chamade''. Carved details on the cases by Derek Riley show Scottish plants and animals, a Franciscan Friar

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

, and Greyfriars Bobby

Greyfriars Bobby (4 May 1855 – 14 January 1872) was a Skye Terrier or Dandie Dinmont Terrier who became known in 19th-century Edinburgh for spending 14 years guarding the grave of his owner until he died on 14 January 1872. The story continu ...

. Along the frieze

In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor ...

of the towers runs the penultimate phrase of Psalm 150

Psalm 150 is the 150th and final psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "Praise ye the . Praise God in his sanctuary". In Latin, it is known as "Laudate Dominum in sanctis eius". In Psalm 150, the psalmist ...

: "''Laudate Dominum onme quod spirat''" ("Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord"). A chamber organ

Carol Williams performing at the United States Military Academy West Point Cadet Chapel.">West_Point_Cadet_Chapel.html" ;"title="United States Military Academy West Point Cadet Chapel">United States Military Academy West Point Cadet Chapel.

...

stands in the north aisle: this was built around 1845 by David Hamilton of Edinburgh and purchased in 1968.

The first organ in Greyfriars was a harmonium

The pump organ is a type of free-reed organ that generates sound as air flows past a vibrating piece of thin metal in a frame. The piece of metal is called a reed. Specific types of pump organ include the reed organ, harmonium, and melodeon. Th ...

installed against the west wall of Old Greyfriars in 1863, during the ministry of Robert Lee. This was the first successful attempt to introduce an organ in a Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

building. The harmonium was replaced in 1865 with a two-manual pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurized air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in sets called ''ranks' ...

by D. & T. Hamilton of Edinburgh. This was rebuilt and enlarged to three manuals in 1883 by Brindley & Foster