Greek Muslims on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Greek Muslims, also known as Grecophone Muslims, are

Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey: prolegomena to a study of the Ophitic sub-dialect of Pontic.

''Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies''. 11. (1): 117. Because of their gradual

In Turkey, Pontic Greek Muslim communities are sometimes called ''Rum''. However, as with ''Yunan'' (Turkish for "Greek") or the English word "Greek," this term 'is associated in Turkey to be with Greece and/or Christianity, and many Pontic Greek Muslims refuse such identification. The

The term

The term

Turkish-Speaking Christians, Jews and Greek-Speaking Muslims and Catholics in the Ottoman Empire

'. Eren. Istanbul. p. 324. "Neither the younger generations of Ottoman specialists in Greece, nor specialist interested in Greek-speaking Muslims have not been much involved with these works, quite possibly because there is no substantial corpus of them." Today, in various settlements along the Aegean coast, elderly Grecophone Cretan Muslims are still conversant in Cretan Greek. Many in the younger generations are fluent in the Greek language. Often, members of the Muslim Cretan community are unaware that the language they speak is Greek.Philliou, Christine (2008). "The Paradox of Perceptions: Interpreting the Ottoman Past through the National Present". ''Middle Eastern Studies''. 44. (5): 672. "The second reason my services as an interpreter were not needed was that the current inhabitants of the village which had been vacated by apparently Turkish-speaking Christians en route to Kavala, were descended from Greek-speaking Muslims that had left Crete in a later stage of the same population exchange. It was not infrequent for members of these groups, settled predominantly along coastal Anatolia and the Marmara Sea littoral in Turkey, to be unaware that the language they were speaking was Greek. Again, it was not illegal for them to be speaking Greek publicly in Turkey, but it undermined the principle that Turks speak Turkish, just like Frenchmen speak French and Russians speak Russian." Frequently, they refer to their native tongue as Cretan (''Kritika'' ' or ''Giritçe'') instead of Greek.

''The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece: The grounds for the expulsion of a "non-existent" minority community''

European Journal of Turkish Studies. "It's worth mentioning that the Greek speaking Muslim communities, which were the majority population at Yanina and Paramythia, and of substantial numbers in Parga and probably Preveza, shared the same route of identity construction, with no evident differentiation between them and their Albanian speaking co-habitants." Hoca Sadeddin Efendi, a Greek-speaking Muslim from Ioannina in the 18th century, was the first translator of

Asimochori

an

Loksada

in Karditsa. It is possible that they and also the Albanian Muslims were the ones who did not fully understand the Greek Language. Moreover, some Muslims served as interpreters in these transactions.

by Roula Tsokalidou. Proceedings ''II Simposio Internacional Bilingüismo''. Retrieved 4 December 2006 The majority of them are Muslims of Cretan origin. Records suggest that the community left Crete between 1866 and 1897, on the outbreak of the last Cretan uprising against the Ottoman Empire, which ended the

p. 17.

"Kökleri, baba tarafından Çankırı 'sancağı'nın

* Hussein Hilmi Pasha – (1855–1922), Ottoman statesman born on

* Hussein Hilmi Pasha – (1855–1922), Ottoman statesman born on

* Al-Khazini – (flourished 1115–1130) was a Greek Muslim scientist, astronomer, physicist, biologist, alchemist, mathematician and philosopher – lived in

* Al-Khazini – (flourished 1115–1130) was a Greek Muslim scientist, astronomer, physicist, biologist, alchemist, mathematician and philosopher – lived in  *

*

Expulsion and Emigration of the Muslims from the BalkansEGO - European History Online

Mainz

Institute of European History

retrieved: March 25, 2021

pdf

.

www.GreekMuslims.com

Karalahana.com

Trebizond Greek: A language without a tongue

Radio Ocena

Rest in Crimea

Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī {{Ottoman Greece Greek Muslims, People from the Ottoman Empire of Greek descent, Greeks from the Ottoman Empire Ethnic groups in Greece Ethnic groups in Turkey Turkish culture Muslim communities in Europe

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

ethnic origin whose adoption of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

(and often the Turkish language

Turkish ( , ), also referred to as Turkish of Turkey (''Türkiye Türkçesi''), is the most widely spoken of the Turkic languages, with around 80 to 90 million speakers. It is the national language of Turkey and Northern Cyprus. Significant sma ...

and identity) dates to the period of Ottoman rule in the southern Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. They consist primarily of the descendants of the elite Ottoman Janissary

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

corps and Ottoman-era converts to Islam from Greek Macedonia

Macedonia (; el, Μακεδονία, Makedonía ) is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and Greek geographic region, with a population of 2.36 million in 2020. It is ...

(e.g., Vallahades), Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

(Cretan Muslims

The Cretan Muslims ( el, Τουρκοκρητικοί or , or ; tr, Giritli, , or ; ar, أتراك كريت) or Cretan Turks were the Muslim inhabitants of the island of Crete. Their descendants settled principally in Turkey, the Dodecanese ...

), and northeastern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and the Pontic Alps

The Pontic Mountains or Pontic Alps ( Turkish: ''Kuzey Anadolu Dağları'', meaning North Anatolian Mountains) form a mountain range in northern Anatolia, Turkey. They are also known as the ''Parhar Mountains'' in the local Turkish and Pontic G ...

(Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks ( pnt, Ρωμαίοι, Ρωμίοι, tr, Pontus Rumları or , el, Πόντιοι, or , , ka, პონტოელი ბერძნები, ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group i ...

). They are currently found mainly in the west of Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

(particularly the regions of Izmir, Bursa

( grc-gre, Προῦσα, Proûsa, Latin: Prusa, ota, بورسه, Arabic:بورصة) is a city in northwestern Turkey and the administrative center of Bursa Province. The fourth-most populous city in Turkey and second-most populous in the ...

, and Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis ( Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders ...

) and the northeast (particularly in the regions of Trabzon

Trabzon (; Ancient Greek: Tραπεζοῦς (''Trapezous''), Ophitic Pontic Greek: Τραπεζούντα (''Trapezounta''); Georgian: ტრაპიზონი (''Trapizoni'')), historically known as Trebizond in English, is a city on the B ...

, Gümüşhane, Sivas

Sivas (Latin and Greek: ''Sebastia'', ''Sebastea'', Σεβάστεια, Σεβαστή, ) is a city in central Turkey and the seat of Sivas Province.

The city, which lies at an elevation of in the broad valley of the Kızılırmak river, is ...

, Erzincan

Erzincan (; ku, Erzîngan), historically Yerznka ( hy, Երզնկա), is the capital of Erzincan Province in Eastern Turkey. Nearby cities include Erzurum, Sivas, Tunceli, Bingöl, Elazığ, Malatya, Gümüşhane, Bayburt, and Giresun. The ...

, Erzurum

Erzurum (; ) is a city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses the double-headed eagle as ...

, and Kars

Kars (; ku, Qers; ) is a city in northeast Turkey and the capital of Kars Province. Its population is 73,836 in 2011. Kars was in the ancient region known as ''Chorzene'', (in Greek Χορζηνή) in classical historiography (Strabo), part of ...

).

Despite their ethnic Greek origin, the contemporary Grecophone Muslims of Turkey have been steadily assimilated into the Turkish-speaking Muslim population. Sizable numbers of Grecophone Muslims, not merely the elders but even young people, have retained knowledge of their respective Greek dialects, such as Cretan

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and Pontic Greek

Pontic Greek ( pnt, Ποντιακόν λαλίαν, or ; el, Ποντιακή διάλεκτος, ; tr, Rumca) is a variety of Modern Greek indigenous to the Pontus region on the southern shores of the Black Sea, northeastern Anatolia, ...

.Mackridge, Peter (1987).Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey: prolegomena to a study of the Ophitic sub-dialect of Pontic.

''Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies''. 11. (1): 117. Because of their gradual

Turkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

, as well as the close association of Greece and Greeks with Orthodox Christianity

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Chu ...

and their perceived status as a historic, military threat to the Turkish Republic

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

, very few are likely to call themselves ''Greek Muslims''. In Greece, Greek-speaking Muslims are not usually considered as forming part of the Greek nation.Mackridge, Peter (2010). ''Language and national identity in Greece, 1766–1976''. Oxford University Press. p. 65. "Greek-speaking Muslims have not usually been considered as belonging to the Greek nation. Some communities of Greek-speaking Muslims lived in Macedonia. Muslims, most of them native speakers of Greek, formed a slight majority of the population of Crete in the early nineteenth century. The vast majority of these were descended from Christians who had voluntarily converted to Islam in the period following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1669."

In the late Ottoman period, particularly after the Greco-Turkish War (1897), several communities of Grecophone Muslims from Crete and southern Greece were also relocated to Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

, and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, where, in towns like al-Hamidiyah

Al-Hamidiyah ( ar, الحميدية, al-Hamidiyya, gr, Χαμιδιέ) is a town on the Syrian coast, about 3 km from the Lebanese border. The town was founded in a very short time on the direct orders of the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamit I ...

, some of the older generation continue to speak Greek. Historically, Greek Orthodoxy

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

has been associated with being '' Romios'' (i.e., Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

) and Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

with being Turkish, despite ethnicity or language.

Most Greek-speaking Muslims in Greece left for Turkey during the 1920s population exchanges under the Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations

The Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations, also known as the Lausanne Convention, was an agreement between the Greek and Turkish governments signed by their representatives in Lausanne on 30 January 1923, in the aft ...

(in return for Turkish-speaking Christians such as the Karamanlides

The Karamanlides ( el, Καραμανλήδες; tr, Karamanlılar), also known as Karamanli Greeks or simply Karamanlis, are a traditionally Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox people native to the Karaman and Cappadocia regions of Anatolia.

Th ...

). Due to the historical role of the ''millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets a ...

'' system, religion and not ethnicity or language was the main factor used during the exchange of populations. All Muslims who departed Greece were seen as "Turks," whereas all Orthodox people leaving Turkey were considered "Greeks," again regardless of their ethnicity or language.Poulton, Hugh (2000). "The Muslim experience in the Balkan states, 1919‐1991." ''Nationalities Papers''. 28. (1): 46. "In these exchanges, due to the influence of the ''millet'' system (see below), religion not ethnicity or language was the key factor, with all the Muslims expelled from Greece seen as "Turks," and all the Orthodox people expelled from Turkey seen as "Greeks" regardless of mother tongue or ethnicity." An exception was made for the native Muslim Pomaks

Pomaks ( bg, Помаци, Pomatsi; el, Πομάκοι, Pomáki; tr, Pomaklar) are Bulgarian-speaking Muslims inhabiting northwestern Turkey, Bulgaria and northeastern Greece. The c. 220,000 strong ethno-confessional minority in Bulgaria is ...

and Western Thrace Turks

Turks of Western Thrace ( tr, , el, Τούρκοι της Δυτικής Θράκης, Toúrkoi tis Dytikís Thrákis) are ethnic Turks who live in Western Thrace, in the province of East Macedonia and Thrace in Northern Greece.

According ...

living east of the River Nestos in East Macedonia and Thrace

Eastern Macedonia and Thrace ( el, Ανατολική Μακεδονία και Θράκη, translit=Anatolikí Makedonía ke Thráki, ) is one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It consists of the northeastern parts of the cou ...

, Northern Greece

Northern Greece ( el, Βόρεια Ελλάδα, Voreia Ellada) is used to refer to the northern parts of Greece, and can have various definitions.

Administrative regions of Greece

Administrative term

The term "Northern Greece" is widely used ...

, who are officially recognized as a religious minority by the Greek government.

In Turkey, where most Greek-speaking Muslims live, there are various groups of Grecophone Muslims, some autochthonous, some from parts of present-day Greece and Cyprus who migrated to Turkey under the population exchanges or immigration.

Motivations for conversion to Islam

As a rule, theOttomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

did not require the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

or any other non-Islamic group to become Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s. In fact they discouraged it, because the dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

could be more easily exploited in various ways.

Taxation

Dhimmi were subject to the heavyjizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

tax, which was about 20%, versus the Muslim zakat

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is ...

, which was about 3%. Other major taxes were the Defter

A ''defter'' (plural: ''defterler'') was a type of tax register and land cadastre in the Ottoman Empire.

Description

The information collected could vary, but ''tahrir defterleri'' typically included details of villages, dwellings, household ...

and İspençe

İspençe was a land tax levied on non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire.

İspençe was a land-tax on non-Muslims in parts of the Ottoman Empire; its counterpart, for Muslim taxpayers, was the resm-i çift - which was set at slightly lower rate. The ...

and the more severe haraç

Haraç ( hy, խարջ, kharj, mk, арач, arač, gr, χαράτσι, charatsi, sh-Cyrl-Latn, харач, harač) was a land tax levied on non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire.

''Haraç'' was developed from an earlier form of land taxation, ' ...

, whereby a document was issued which stated that "the holder of this certificate is able to keep his head on the shoulders since he paid the Χαράτσι tax for this year..." All these taxes were waived if the person converted to Islam.

Devşirme

Non-Muslims were also subjected to practices likedevşirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

(blood tax), in which the Ottomans took Christian boys from their families and later converted them to Islam with the aim of selecting and training the ablest of them for leading positions in Ottoman society.

Legal system

Another benefit converts received was better legal protection. The Ottoman Empire had two separate court systems, the Islamic court and the non-Islamic court, with the decisions of the former superseding those of the latter. Because non-Muslims were forbidden in the Islamic court, they could not defend their cases and were doomed to lose every time.Career opportunities

Conversion also yielded greater employment prospects and possibilities of advancement in the Ottoman government bureaucracy and military. Subsequently, these people became part of the Muslim community of themillet system

In the Ottoman Empire, a millet (; ar, مِلَّة) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was ...

, which was closely linked to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

ic religious rules. At that time, people were bound to their millets by their religious affiliations (or their confessional communities), rather than by their ethnic origins.Ortaylı, İlber. ''"Son İmparatorluk Osmanlı (The Last Empire: Ottoman Empire)"'', İstanbul, Timaş Yayınları (Timaş Press), 2006. pp. 87–89. . Muslim communities prospered under the Ottoman Empire, and as Ottoman law did not recognize such notions as ethnicity

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

, Muslims of all ethnic backgrounds enjoyed precisely the same rights and privileges.

Avoiding slavery

During theGreek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

, Ottoman Egyptian troops under the leadership of Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt ravaged the island of Crete and the Greek countryside of the Morea

The Morea ( el, Μορέας or ) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The name was used for the Byzantine province known as the Despotate of the Morea, by the Ottom ...

, where Muslim Egyptian soldiers enslaved vast numbers of Christian Greek children and women. Ibrahim arranged for the enslaved Greek children to be forcefully converted to Islam ''en masse''. The enslaved Greeks were subsequently transferred to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, where they were sold. Several decades later in 1843, the English traveler and writer Sir John Gardner Wilkinson

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (5 October 1797 – 29 October 1875) was an English traveller, writer and pioneer Egyptologist of the 19th century. He is often referred to as "the Father of British Egyptology".

Childhood and education

Wilkinson ...

described the state of enslaved Greeks who had converted to Islam in Egypt:

:

A great many Greeks and Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

became Muslims to avoid these hardships. Conversion to Islam is quick, and the Ottoman Empire did not keep extensive documentation on the religions of their individual subjects. The only requirements were knowing Turkish, saying you were Muslim, and possibly getting circumcised. Converts might also signal their conversion by wearing the brighter clothes favored by Muslims, rather than the drab garments of Christians and Jews in the empire.

Greek has a specific verb, ''τουρκεύω'' (''tourkevo''), meaning "to become a Turk." The equivalent in Serbian and other South Slavic languages is ''turčiti'' (imperfective) or ''poturčiti'' (perfective). Fake conversions were common; they explain why many people in the Balkans have Turkish last names with suffixes like ''-oglu''.

Greek Muslims of Pontus and the Caucasus

Geographic dispersal

Pontic Greek

Pontic Greek ( pnt, Ποντιακόν λαλίαν, or ; el, Ποντιακή διάλεκτος, ; tr, Rumca) is a variety of Modern Greek indigenous to the Pontus region on the southern shores of the Black Sea, northeastern Anatolia, ...

(called ''Ρωμαίικα'' ''Roméika'' in the Pontus, not ''Ποντιακά'' ''Pontiaká'' as it is in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

), is spoken by large communities of Pontic Greek

Pontic Greek ( pnt, Ποντιακόν λαλίαν, or ; el, Ποντιακή διάλεκτος, ; tr, Rumca) is a variety of Modern Greek indigenous to the Pontus region on the southern shores of the Black Sea, northeastern Anatolia, ...

Muslim origin, spread out near the southern Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

coast. Grecophone Pontian Muslims are found within Trabzon province

Trabzon Province ( tr, ) is a province of Turkey on the Black Sea coast. Located in a strategically important region, Trabzon is one of the oldest trade port cities in Anatolia. Neighbouring provinces are Giresun to the west, Gümüşhane to th ...

in the following areas:

Today these Greek-speaking Muslims regard themselves and identify as Turks. Nonetheless, a great many have retained knowledge of and/or are fluent in Greek, which continues to be a mother tongue

A first language, native tongue, native language, mother tongue or L1 is the first language or dialect that a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tong ...

for even young Pontic Muslims.Mackridge. ''Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey''. 1987. p. 117. Men are usually bilingual in Turkish and Pontic Greek, while many women are monolingual Pontic Greek speakers.

History

Many Pontic natives were converted to Islam during the first two centuries following the Ottoman conquest of the region. Taking high military and religious posts in the empire, their elite were integrated into the ruling class of imperial society. The converted population accepted Ottoman identity, but in many instances people retained their local, native languages. In 1914, according to the official estimations of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, about 190,000 Grecophone Muslims were counted in the Pontus alone. Over the years, heavy emigration from the Trabzon region to other parts of Turkey, to places such asIstanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

, Sakarya, Zonguldak

Zonguldak () is a city and the capital of Zonguldak Province in the Black Sea region of Turkey. It was established in 1849 as a port town for the nearby coal mines in Ereğli and the coal trade remains its main economic activity. According to the ...

, Bursa

( grc-gre, Προῦσα, Proûsa, Latin: Prusa, ota, بورسه, Arabic:بورصة) is a city in northwestern Turkey and the administrative center of Bursa Province. The fourth-most populous city in Turkey and second-most populous in the ...

and Adapazarı

Adapazarı () is a city in northwestern Turkey and the central district of Sakarya Province. The province itself was originally named Adapazarı as well. Adapazarı is a part of the densely populated region of the country known as the Marmara Re ...

, has occurred.Hakan. ''The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims''. 2013. p. 131. Emigration out of Turkey has also occurred, such as to Germany as guest workers during the 1960s.

endonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

for Pontic Greek is ''Romeyka'', while ''Rumca'' and/or ''Rumcika'' are Turkish exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group ...

s for all Greek dialects spoken in Turkey. Both are derived from ''ρωμαίικα'', literally "Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

" but referring to the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

s.Hakan. ''The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims''. 2013. p. 133. Modern-day Greeks call their language ''ελληνικά'' (''Hellenika''), meaning Greek, an appellation that replaced the previous term ''Romeiika'' in the early 19th century. In Turkey, standard modern Greek

Modern Greek (, , or , ''Kiní Neoellinikí Glóssa''), generally referred to by speakers simply as Greek (, ), refers collectively to the dialects of the Greek language spoken in the modern era, including the official standardized form of the ...

is called ''Yunanca''; ancient Greek is called either ''Eski Yunanca'' or ''Grekçe''.

Religious practice

According to Heath W. Lowry's seminal work on Ottoman tax books (''Tahrir Defteri'', with co-author Halil İnalcık), most "Turks" in Trebizond and thePontic Alps

The Pontic Mountains or Pontic Alps ( Turkish: ''Kuzey Anadolu Dağları'', meaning North Anatolian Mountains) form a mountain range in northern Anatolia, Turkey. They are also known as the ''Parhar Mountains'' in the local Turkish and Pontic G ...

region in northeastern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

are of Pontic Greek origin. Grecophone Pontian Muslims are known in Turkey for their conservative adherence to Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disag ...

of the Hanafi

The Hanafi school ( ar, حَنَفِية, translit=Ḥanafiyah; also called Hanafite in English), Hanafism, or the Hanafi fiqh, is the oldest and one of the four traditional major Sunni schools ( maddhab) of Islamic Law (Fiqh). It is named a ...

school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes co ...

and are renowned for producing many Quranic teachers. Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

orders such as Qadiri and Naqshbandi

The Naqshbandi ( fa, نقشبندی)), Neqshebendi ( ku, نهقشهبهندی), and Nakşibendi (in Turkish) is a major Sunni order of Sufism. Its name is derived from Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari. Naqshbandi masters trace their ...

have a great impact.

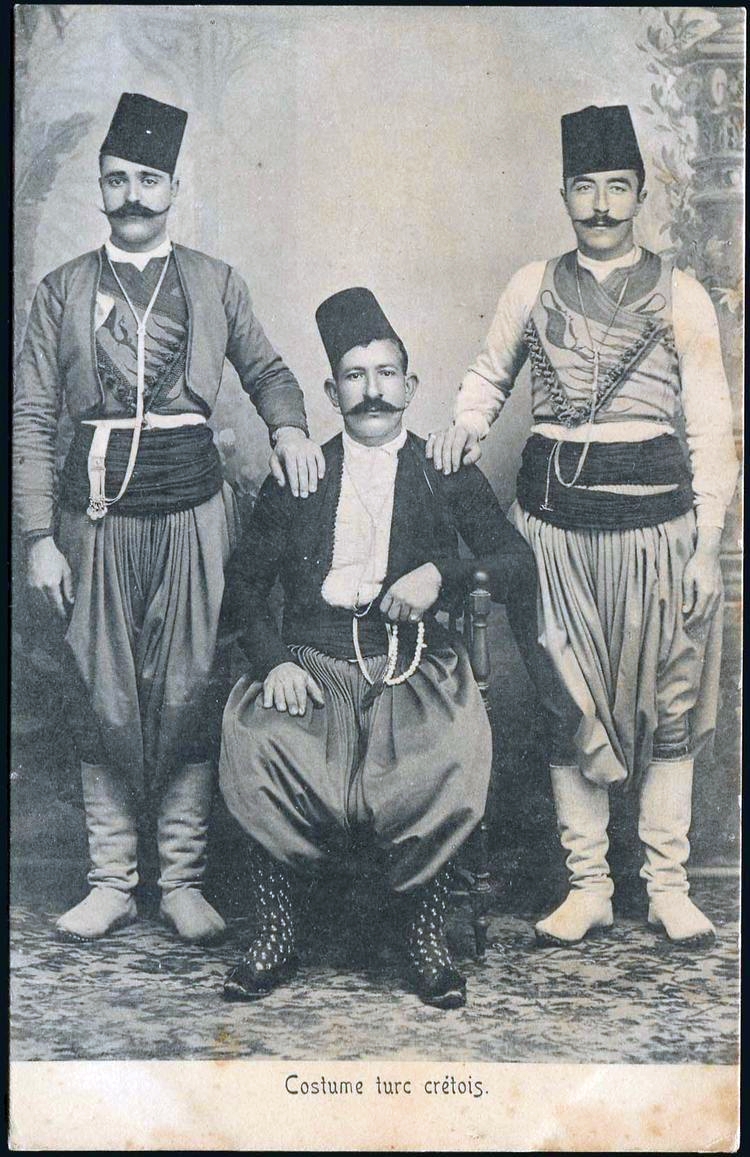

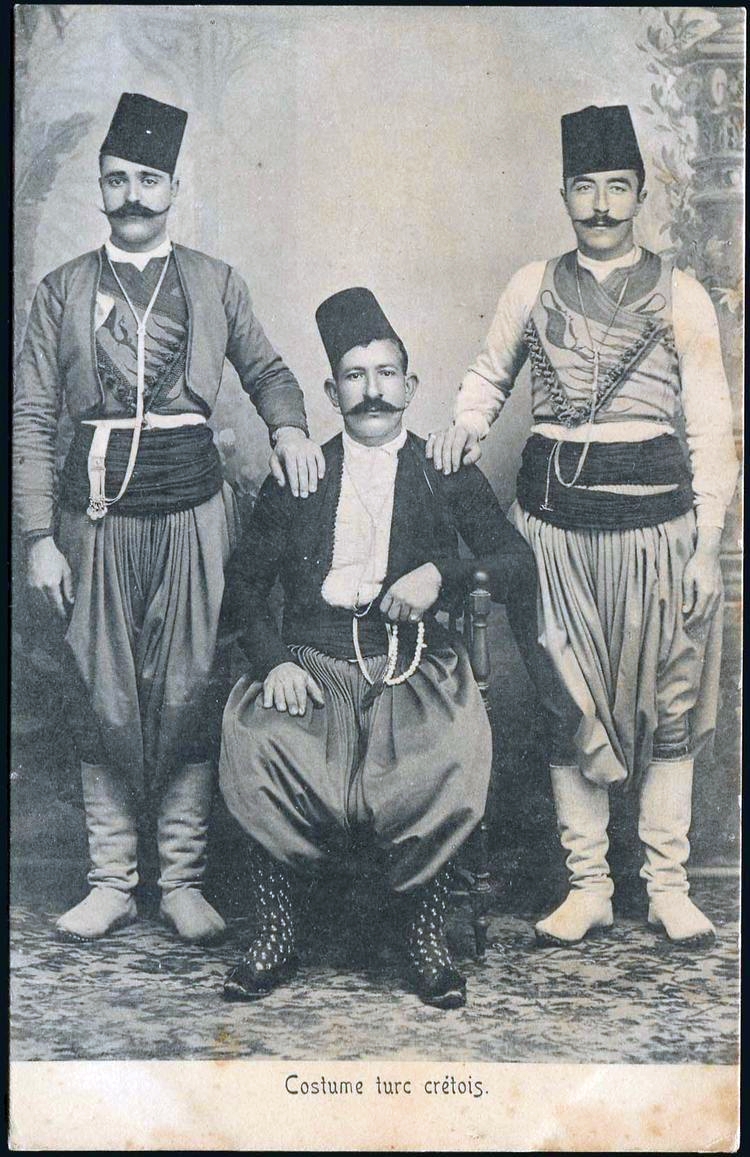

Cretan Muslims

The term

The term Cretan Turks

The Cretan Muslims ( el, Τουρκοκρητικοί or , or ; tr, Giritli, , or ; ar, أتراك كريت) or Cretan Turks were the Muslim inhabitants of the island of Crete. Their descendants settled principally in Turkey, the Dodecanese ...

( tr, Girit Türkleri, gr, Τουρκοκρητικοί) or ''Cretan Muslims'' ( tr, Girit Müslümanları) refers to Greek-speaking MuslimsKatsikas, Stefanos (2012). "Millet legacies in a national environment: Political elites and Muslim communities in Greece (1830s–1923)". In Fortna, Benjamin C., Stefanos Katsikas, Dimitris Kamouzis, & Paraskevas Konortas (eds). ''State-nationalisms in the Ottoman Empire, Greece and Turkey: Orthodox and Muslims, 1830–1945''. Routledge. 2012. p.50. "Indeed, the Muslims of Greece included... Greek speaking (Crete and West Macedonia, known as ''Valaades'')." who arrived in Turkey after or slightly before the start of the Greek rule in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

in 1908, and especially in the context of the 1923 agreement for the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations. Prior to their resettlement in Turkey, deteriorating communal relations between Cretan Greek Christians and Grecophone Cretan Muslims drove the latter to identify with Ottoman and later Turkish identity.

Geographic dispersal

Cretan Muslims have largely settled on the coastline, stretching from the Çanakkale toİskenderun

İskenderun ( ar, الإسكندرونة, el, Αλεξανδρέττα "Little Alexandria"), historically known as Alexandretta and Scanderoon, is a city in Hatay Province on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey.

Names

The city was founded as Ale ...

.Kappler, Matthias (1996). "Fra religione e lingua/grafia nei Balcani: i musulmani grecofoni (XVIII-XIX sec.) e un dizionario rimato ottomano-greco di Creta." ''Oriente Moderno''. 15. (76): 91. "In ogni caso, i musulmani cretesi, costituendo la maggior parte dei musulmani grecofoni, hanno risentito particolarmente dello scambio deile popolazioni del 1923 (anche se molti di loro erano emigrati già dagli anni ‘80 del secolo scorso, e in altre parti della Grecia addirittura subito dopo l’indipendenza), scambio che, come è noto, si basava sul criterio della millet ottomana, cioè sull’appartenenza religiosa, e non su quella linguistica (un’appartenenza "culturale" era impossibile da definirsi). Condividendo la sorte dei cristiani turcofoni venuti dall’Asia minore, i quali mutavano la struttura socio-culturale della Grecia, i musulmani grecofoni hanno dovuto lasciare le loro case, con la conseguenza che ancora fino a pochi anni fa in alcune città della costa anatolica (Çeşme, Izmir, Antalya) era possibile sentir conversare certe persone anziane, apparentemente "turche", in dialetto greco-cretese." Significant numbers were resettled in other Ottoman-controlled areas around the eastern Mediterranean by the Ottomans following the establishment of the autonomous Cretan State in 1898. Most ended up in coastal Syria and Lebanon, particularly the town of Al-Hamidiyah

Al-Hamidiyah ( ar, الحميدية, al-Hamidiyya, gr, Χαμιδιέ) is a town on the Syrian coast, about 3 km from the Lebanese border. The town was founded in a very short time on the direct orders of the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamit I ...

, in Syria, (named after the Ottoman sultan who settled them there), and Tripoli in Lebanon, where many continue to speak Greek as their mother tongue. Others were resettled in Ottoman Tripolitania

The coastal region of what is today Libya was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1912. First, from 1551 to 1864, as the Eyalet of Tripolitania ( ota, ایالت طرابلس غرب ''Eyālet-i Trâblus Gârb'') or '' Bey and Subjects of Tr ...

, especially in the eastern cities like Susa

Susa ( ; Middle elx, 𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗, translit=Šušen; Middle and Neo- elx, 𒋢𒋢𒌦, translit=Šušun; Neo- Elamite and Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭, translit=Šušán; Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼, translit=Šušá; fa, شوش ...

and Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη ('' Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghaz ...

, where they are distinguishable by their Greek surnames. Many of the older members of this last community still speak Cretan Greek in their homes.

A small community of Grecophone Cretan Muslims still resides in Greece in the Dodecanese Islands of Rhodes and Kos. These communities were formed prior to the area becoming part of Greece in 1948, when their ancestors migrated there from Crete, and their members are integrated into the local Muslim population as Turks today.Comerford, Patrick (2000). "Defining Greek and Turk: Uncertainties in the search for European and Muslim identities". ''Cambridge Review of International Affairs''. 13.(2): 250. "Despite the provisions of the Lausanne Treaty, some surprising and unforeseen anomalies were to arise. As yet, the Greek state did not include the Dodecannese, and many of the Muslims from Crete moved to Kos and Rhodes, began to integrate with the local Muslim population. When the Dodecannese were incorporated in the Greek state in 1948, the Turks of Kos and Rhodes found once again that they were citizens of Greece. On many occasions I have passed the dilapidated refugee village of ''Kritika'' "the Cretans" on the coast road out of Rhodes town on the way to the airport; in the town itself, it is easy to pick out Turkish names on the marquees of sandal-makers, or on the names of kafenia and kebab stands. In Kos, the domestic architecture of the bi-ethnic village of Platani can be strongly reminiscent of rural styles in provincial Crete."

Language

Some Grecophone Muslims of Crete composed literature for their community in the Greek language, such as songs, but wrote it in the Arabic alphabet. although little of it has been studied.Dedes, Yorgos (2010). "Blame it on the Turko-Romnioi (''Turkish Rums''): A Muslim Cretan song on the abolition of the Janissaries". In Balta, Evangelia & Mehmet Ölmez (eds.).Turkish-Speaking Christians, Jews and Greek-Speaking Muslims and Catholics in the Ottoman Empire

'. Eren. Istanbul. p. 324. "Neither the younger generations of Ottoman specialists in Greece, nor specialist interested in Greek-speaking Muslims have not been much involved with these works, quite possibly because there is no substantial corpus of them." Today, in various settlements along the Aegean coast, elderly Grecophone Cretan Muslims are still conversant in Cretan Greek. Many in the younger generations are fluent in the Greek language. Often, members of the Muslim Cretan community are unaware that the language they speak is Greek.Philliou, Christine (2008). "The Paradox of Perceptions: Interpreting the Ottoman Past through the National Present". ''Middle Eastern Studies''. 44. (5): 672. "The second reason my services as an interpreter were not needed was that the current inhabitants of the village which had been vacated by apparently Turkish-speaking Christians en route to Kavala, were descended from Greek-speaking Muslims that had left Crete in a later stage of the same population exchange. It was not infrequent for members of these groups, settled predominantly along coastal Anatolia and the Marmara Sea littoral in Turkey, to be unaware that the language they were speaking was Greek. Again, it was not illegal for them to be speaking Greek publicly in Turkey, but it undermined the principle that Turks speak Turkish, just like Frenchmen speak French and Russians speak Russian." Frequently, they refer to their native tongue as Cretan (''Kritika'' ' or ''Giritçe'') instead of Greek.

Religious practice

Grecophone Cretan Muslims are Sunnis of theHanafi

The Hanafi school ( ar, حَنَفِية, translit=Ḥanafiyah; also called Hanafite in English), Hanafism, or the Hanafi fiqh, is the oldest and one of the four traditional major Sunni schools ( maddhab) of Islamic Law (Fiqh). It is named a ...

school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes co ...

, with a highly influential Bektashi

The Bektashi Order; sq, Tarikati Bektashi; tr, Bektaşi or Bektashism is an Islamic Sufi mystic movement originating in the 13th-century. It is named after the Anatolian saint Haji Bektash Wali (d. 1271). The community is currently led by ...

minority who helped shape the folk Islam and religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

of the entire community.

Epirote Muslims

Muslims from the region ofEpirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, known collectively as ''Yanyalılar'' (singular ''Yanyalı'', meaning "person from Ioannina

Ioannina ( el, Ιωάννινα ' ), often called Yannena ( ' ) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus, an administrative region in north-western Greece. According to the 2011 census, the c ...

") in Turkish and ''Τουρκογιαννιώτες'' ''Turkoyanyótes'' in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(singular ''Τουρκογιαννιώτης'' ''Turkoyanyótis'', meaning "Turk from Ioannina") arrived in Turkey in two waves of migration, in 1912 and after 1923. After the exchange of populations, Grecophone Epirote Muslims resettled themselves in the Anatolian section of Istanbul, especially the districts from Erenköy to Kartal, which had previously been populated by wealthy Orthodox Greeks.Yildirim, Onur (2006). ''Diplomacy and displacement: reconsidering the Turco-Greek exchange of populations, 1922–1934''. Taylor & Francis. p. 112. "As we learn from Riza Nur's memoirs, the Anatolian section of Istanbul, especially the districts from Erenköy to Kartal, which had been populated by the wealthiest of the Greek minority, was subjected to the invasion of the Albanian refugees from Janina, who spoke only Greek." Although the majority of the Epirote Muslim population was of Albanian origins, Grecophone Muslim communities existed in the towns of Souli, Margariti

Margariti ( el, Μαργαρίτι; sq, Margëlliç) is a village and a former municipality in Thesprotia, Epirus, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Igoumenitsa, of which it is a municipal unit. The ...

(both majority-Muslim), Ioannina

Ioannina ( el, Ιωάννινα ' ), often called Yannena ( ' ) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus, an administrative region in north-western Greece. According to the 2011 census, the c ...

, Preveza

Preveza ( el, Πρέβεζα, ) is a city in the region of Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula at the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the regional unit of Preveza, which is part of the region of Epiru ...

, Louros

Louros ( el, Λούρος) is a town and a former municipality in the Preveza regional unit, Epirus, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Preveza, of which it is a municipal unit. The seat of the municip ...

, Paramythia

Paramythia ( el, Παραμυθιά) is a town and a former municipality in Thesprotia, Epirus, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Souli, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. The municipal un ...

, Konitsa, and elsewhere in the Pindus

The Pindus (also Pindos or Pindhos; el, Πίνδος, Píndos; sq, Pindet; rup, Pindu) is a mountain range located in Northern Greece and Southern Albania. It is roughly 160 km (100 miles) long, with a maximum elevation of 2,637 metres ...

mountain region. The Greek-speaking Muslim populations who were a majority in Ioannina and Paramythia, with sizable numbers residing in Parga and possibly Preveza, "shared the same route of identity construction, with no evident differentiation between them and their Albanian-speaking cohabitants."Lambros Baltsiotis (2011)''The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece: The grounds for the expulsion of a "non-existent" minority community''

European Journal of Turkish Studies. "It's worth mentioning that the Greek speaking Muslim communities, which were the majority population at Yanina and Paramythia, and of substantial numbers in Parga and probably Preveza, shared the same route of identity construction, with no evident differentiation between them and their Albanian speaking co-habitants." Hoca Sadeddin Efendi, a Greek-speaking Muslim from Ioannina in the 18th century, was the first translator of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

into Turkish. Some Grecophone Muslims of Ioannina composed literature for their community in the Greek language, such as poems, using the Arabic alphabet. The community now is fully integrated into Turkish culture. Last, the Muslims from Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

that were of mainly Albanian origin are described as Cham Albanians

Cham Albanians or Chams ( sq, Çamë; el, Τσάμηδες, ''Tsámidhes''), are a sub-group of Albanians who originally resided in the western part of the region of Epirus in northwestern Greece, an area known among Albanians as Chameria. Th ...

instead.

Macedonian Greek Muslims

The Greek-speaking Muslims who lived in theHaliacmon

The Haliacmon ( el, Αλιάκμονας, ''Aliákmonas''; formerly: , ''Aliákmon'' or ''Haliákmōn'') is the longest river flowing entirely in Greece, with a total length of . In Greece there are three rivers longer than Haliakmon, Maritsa ( e ...

of western Macedonia

Western Macedonia ( el, Δυτική Μακεδονία, translit=Ditikí Makedonía, ) is one of the thirteen regions of Greece, consisting of the western part of Macedonia. Located in north-western Greece, it is divided into the regional uni ...

were known collectively as '' Vallahades''; they had probably converted to Islam ''en masse'' in the late 1700s. The Vallahades retained much of their Greek culture and language. This is in contrast with most Greek converts to Islam from Greek Macedonia

Macedonia (; el, Μακεδονία, Makedonía ) is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and Greek geographic region, with a population of 2.36 million in 2020. It is ...

, other parts of Macedonia, and elsewhere in the southern Balkans, who generally adopted the Turkish language and identity and thoroughly assimilated into the Ottoman ruling elite. According to Todor Simovski's assessment (1972), 13,753 Muslim Greeks lived in Greek Macedonia in 1912.

In the 20th century, the Vallahades were considered by other Greeks to have become ''Turkish'' and were not exempt from the 1922–1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

. The Vallahades were resettled in western Asia Minor, in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece

Büyükçekmece is a district and municipality in the suburbs of Istanbul, Turkey on the Sea of Marmara coast of the European side, west of the city. It is largely an industrial area with a population of 380,000. The mayor is Hasan Akgün ( ...

, and Çatalca

Çatalca (Metrae; ) is a city and a rural district in Istanbul, Turkey. It is the largest district in Istanbul by area.

It is in East Thrace, on the ridge between the Marmara and the Black Sea. Most people living in Çatalca are either farmers ...

or in villages like Honaz near Denizli. Many Vallahades still continue to speak the Greek language, which they call ''Romeïka''Koukoudis, Asterios (2003). ''The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora''. Zitros. p. 198. "In the mid-seventeenth century, the inhabitants of many of the villages in the upper Aliakmon valley-in the areas of Grevena, Anaselitsa or Voio, and Kastoria— gradually converted to Islam. Among them were a number of Kupatshari, who continued to speak Greek, however, and to observe many of their old Christian customs. The Islamicised Greek-speaking inhabitants of these areas came to be better known as "Valaades". They were also called "Foutsides", while to the Vlachs of the Grevena area they were also known as "''Vlăhútsi''". According to Greek statistics, in 1923 Anavrytia (Vrastino), Kastro, Kyrakali, and Pigadtisa were inhabited exclusively by Moslems (i.e Valaades), while Elatos (Dovrani), Doxaros (Boura), Kalamitsi, Felli, and Melissi (Plessia) were inhabited by Moslem Valaades and Christian Kupatshari. There were also Valaades living in Grevena, as also in other villages to the north and east of the town. ... the term "Valaades" refers to Greek-speaking Moslems not only of the Grevena area but also of Anaselitsa. In 1924, despite even their own objections, the last of the Valaades being Moslems, were forced to leave Greece under the terms of the compulsory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. Until then they had been almost entirely Greek-speakers. Many of the descendants of the Valaades of Anaseltisa, now scattered through Turkey and particularly Eastern Thrace (in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece, and Çatalca), still speak Greek dialect of Western Macedonia, which, significantly, they themselves call ''Romeïka'' "the language of the Romii". It is worth noting the recent research carried out by Kemal Yalçin, which puts a human face on the fate of 120 or so families from Anavryta and Kastro, who were involved in the exchange of populations. They set sail from Thessaloniki for Izmir, and from there settled en bloc in the village of Honaz near Denizli." and have become completely assimilated into the Turkish Muslim mainstream as Turks.

Thessalian Greek Muslims

Greek-speaking Muslims lived in Thessaly, mostly centered in and around cities such asLarissa

Larissa (; el, Λάρισα, , ) is the capital and largest city of the Thessaly region in Greece. It is the fifth-most populous city in Greece with a population of 144,651 according to the 2011 census. It is also capital of the Larissa regiona ...

, Trikala

Trikala ( el, Τρίκαλα; rup, Trikolj) is a city in northwestern Thessaly, Greece, and the capital of the Trikala regional unit. The city straddles the Lithaios river, which is a tributary of Pineios. According to the Greek National Stati ...

, Karditsa

Karditsa ( el, Καρδίτσα ) is a city in western Thessaly in mainland Greece. The city of Karditsa is the capital of Karditsa regional unit of region of Thessaly.

Inhabitation is attested from 9000 BC. Karditsa ls linked with GR-30, th ...

, Almyros

Almyros or Halmyros ( el, Αλμυρός, , , ) is a town and a municipality of the regional unit of Magnesia, region of Thessaly, Greece. It lies in the center of prosperous fertile plain known as 'Krokio Pedio', which is crossed by torrents. Alm ...

, and Volos

Volos ( el, Βόλος ) is a coastal port city in Thessaly situated midway on the Greek mainland, about north of Athens and south of Thessaloniki. It is the sixth most populous city of Greece, and the capital of the Magnesia regional unit ...

.

Grecophone Muslim communities existed in the towns and certain villages of Elassona

Elassona ( el, Ελασσόνα; Katharevousa: gr, Ἐλασσών, Elasson) is a town and a municipality in the Larissa regional unit in Greece. During antiquity Elassona was called Oloosson (Ὀλοοσσών) and was a town of the Perrhaebi ...

, Tyrnovos, and Almyros. According to Lampros Koutsonikas, Muslims in the kaza

A kaza (, , , plural: , , ; ota, قضا, script=Arab, (; meaning 'borough')

* bg, околия (; meaning 'district'); also Кааза

* el, υποδιοίκησις () or (, which means 'borough' or 'municipality'); also ()

* lad, kaza

, ...

of Elassona lived in six villages such as Stefanovouno, Lofos, Galanovrysi and Domeniko, as well as the town itself and belonged to the '' Vallahades group.'' Evliya Chelebi, who visited the area in 1660s, also mentioned in his '' Seyahâtnâme'' that they spoke Greek. In the 8th volume of his ''Seyahâtnâme'' he mentions that many Muslims of Thessaly were converts of Greek origin. In particular, he writes that the Muslims of Tyrnovos were converts, and that he could not understand the sect to which the of Muslims of Domokos

Domokos ( el, Δομοκός), the ancient Thaumacus or Thaumace (Θαυμακός, Θαυμάκη), is a town and a municipality in Phthiotis, Greece. The town Domokos is the seat of the municipality of Domokos and of the former Domokos Province ...

belonged, claiming they were mixed with "infidels" and thus relieved of paying the haraç

Haraç ( hy, խարջ, kharj, mk, арач, arač, gr, χαράτσι, charatsi, sh-Cyrl-Latn, харач, harač) was a land tax levied on non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire.

''Haraç'' was developed from an earlier form of land taxation, ' ...

tax . Moreover, Chelebi does not mention at all the 12 so-called Konyar Turkish villages that are mentioned in the 18th-century ''Menâkıbnâme'' of Turahan Bey, such as Lygaria, Fallani, Itea, Gonnoi, Krokio and Rodia, which were referenced by Ottoman registrars in the yearly books of 1506, 1521. and 1570. This indicates that the Muslims of Thessaly are indeed mostly of convert origin. There were also some Muslims of Vlach

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other Easter ...

descent assimilated into these communities, such as those in the village of Argyropouli

Argyropouli ( el, Αργυροπούλι, , rup, Caragioli) is an Aromanian ( Vlach) village and a community

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or iden ...

. After the Convention of Constantinople in 1881, these Muslims started emigrating to areas that are still under Turkish administration including to the villages of Elassona.

Artillery captain William Martin Leake

William Martin Leake (14 January 17776 January 1860) was an English military man, topographer, diplomat, antiquarian, writer, and Fellow of the Royal Society. He served in the British military, spending much of his career in the

Mediterrane ...

wrote in his ''Travels in Northern Greece'' (1835) that he spoke with the Bektashi

The Bektashi Order; sq, Tarikati Bektashi; tr, Bektaşi or Bektashism is an Islamic Sufi mystic movement originating in the 13th-century. It is named after the Anatolian saint Haji Bektash Wali (d. 1271). The community is currently led by ...

Sheikh and the Vezir of Trikala

Trikala ( el, Τρίκαλα; rup, Trikolj) is a city in northwestern Thessaly, Greece, and the capital of the Trikala regional unit. The city straddles the Lithaios river, which is a tributary of Pineios. According to the Greek National Stati ...

in Greek. In fact, he specifically states that the Sheikh used the word "ἄνθρωπος" to define men, and he quotes the Vezir as saying, ''καί έγώ εϊμαι προφήτης στά Ιωάννινα.''. British Consul-General John Elijah Blunt observed in the last quarter of the 19th century, "Greek is also generally spoken by the Turkish inhabitants, and appears to be the common language between Turks and Christians."

Research on purchases of property and goods registered in the notarial archive of Agathagellos Ioannidis between 1882 and 1898, right after the annexation, concludes that the overwhelming majority of Thessalian Muslims who became Greek citizens were able to speak and write Greek. An interpreter was needed only in 15% of transactions, half of which involved women, which might indicate that most Thessalian Muslim women were monolingual and possibly illiterate. However, a sizable population of Circassians

The Circassians (also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe; Adyghe and Kabardian: Адыгэхэр, romanized: ''Adıgəxər'') are an indigenous Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia ...

and Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different Turki ...

were settled in Thessaly in the second half of the 19th century, in the towns of Yenişehir (Larissa), Velestino, Ermiye (Almyros), and villages of Balabanlıin the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different Turki ...

Asimochori

an

Loksada

in Karditsa. It is possible that they and also the Albanian Muslims were the ones who did not fully understand the Greek Language. Moreover, some Muslims served as interpreters in these transactions.

Greek Morean/Peleponnesian Muslims

Greek-speaking Muslims lived in cities, citadels, towns, and some villages close to fortified settlements in the Peleponnese, such asPatras

)

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 =

, demographics1_info2 =

, timezone1 = EET

, utc_offset1 = +2

...

, Rio

Rio or Río is the Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and Maltese word for "river". When spoken on its own, the word often means Rio de Janeiro, a major city in Brazil.

Rio or Río may also refer to:

Geography Brazil

* Rio de Janeiro

* Rio do Sul, a ...

, Tripolitsa, Koroni

Koroni or Corone ( el, Κορώνη) is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is a municipal unit. Known as ''Corone'' ...

, Navarino Navarino or Navarin may refer to:

Battle

* Battle of Navarino, 1827 naval battle off Navarino, Greece, now known as Pylos

Geography

* Navarino, Wisconsin, a town, United States

* Navarino (community), Wisconsin, an unincorporated community, Unit ...

, and Methoni. Evliya Chelebi has also mentioned in his ''Seyahatnâme'' that the language of all Muslims in Morea

The Morea ( el, Μορέας or ) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The name was used for the Byzantine province known as the Despotate of the Morea, by the Ottom ...

was ''Urumşa'', which is demotic Greek

Demotic Greek or Dimotiki ( el, Δημοτική Γλώσσα, , , ) is the standard spoken language of Greece in modern times and, since the resolution of the Greek language question in 1976, the official language of Greece.

"Demotic Greek" ( ...

. In particular, he mentions that the wives of Muslims in the castle of Gördüs were non-Muslims. He says that the peoples of Gastouni

Gastouni ( el, Γαστούνη) is a town and a former municipality in Elis, West Greece, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pineios, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. The municipal unit has ...

speak Urumşa, but that they were devout and friendly nonetheless. He explicitly states that the Muslims of Longanikos were converted Greeks, or ''ahıryan''.

Greek Cypriot Muslims

In 1878 the Muslim inhabitants ofCyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

constituted about one-third of the island's population of 120,000. They were classified as being either Turkish or "neo-Muslim." The latter were of Greek origin, Islamised but speaking Greek, and similar in character to the local Christians. The last of such groups was reported to arrive at Antalya

la, Attalensis grc, Ἀτταλειώτης

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 07xxx

, area_code = (+90) 242

, registration_plate = 07

, blank_name = Licence plate

...

in 1936. These communities are thought to have abandoned Greek in the course of integration. During the 1950s, there were still four Greek speaking Muslim settlements in Cyprus: Lapithiou, Platanissos, Ayios Simeon and Galinoporni that identified themselves as Turks.Beckingham, Charles Fraser (1957). "The Turks of Cyprus." ''Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland''. 87. (2): 170–171. "While many Turks habitually speak Turkish there are 'Turkish', that is, Muslim villages in which the normal language is Greek; among them are Lapithou, Platanisso, Ayios Simeon and Galinoporni. This fact has not yet been adequately investigated. With the growth of national feeling and the spread of education the phenomenon is becoming not only rarer but harder to detect. In a Muslim village the school teacher will be a Turk and will teach the children Turkish. They already think of themselves as Turks, and having once learnt the language, will sometimes use it in talking to a visitor in preference to Greek, merely as matter of national pride. It has been suggested that these Greek-speaking Muslims are descended from Turkish- speaking immigrants who have retained their faith but abandoned their language because of the greater flexibility and commercial usefulness of Greek. It is open to the objection that these villages are situated in the remoter parts of the island, in the western mountains and in the Carpass peninsula, where most of the inhabitants are poor farmers whose commercial dealings are very limited. Moreover, if Greek had gradually replaced Turkish in these villages, one would have expected this to happen in isolated places, where a Turkish settlement is surrounded by Greek villages rather than where there are a number of Turkish villages close together as there are in the Carpass. Yet Ayios Simeon (F I), Ayios Andronikos (F I), and Galinoporni (F I) are all Greek-speaking, while the neighbouring village of Korovia (F I) is Turkish-speaking. It is more likely that these people are descended from Cypriots converted to Islam after 1571, who changed their religion but kept their language. This was the view of Menardos (1905, p. 415) and it is supported by the analogous case of Crete. There it is well known that many Cretans were converted to Islam, and there is ample evidence that Greek was almost the only language spoken by either community in the Cretan villages. Pashley (1837, vol. I, p. 8) ‘soon found that the whole rural population of Crete understands ''only'' Greek. The Aghás, who live in the principal towns, also know Turkish; although, even with them, Greek is essentially the mother-tongue.’" A 2017 study on the genetics of Turkish Cypriots

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( tr, Kıbrıs Türkleri or ''Kıbrıslı Türkler''; el, Τουρκοκύπριοι, Tourkokýprioi) are ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,0 ...

has shown strong genetic ties with their fellow Orthodox Greek Cypriots

Greek Cypriots or Cypriot Greeks ( el, Ελληνοκύπριοι, Ellinokýprioi, tr, Kıbrıs Rumları) are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus, forming the island's largest ethnolinguistic community. According to the 2011 census, 659,115 ...

.

Greek Muslims of the Aegean Islands

Despite not having a majority Muslim population at any time during the Ottoman period, some Aegean Islands such asChios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mast ...

, Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Asia Minor by the nar ...

, Kos

Kos or Cos (; el, Κως ) is a Greek island, part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese by area, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 36,986 (2021 census), ...

, Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, Lemnos

Lemnos or Limnos ( el, Λήμνος; grc, Λῆμνος) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean region. The p ...

and Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Province. With an area of it is the third l ...

, and on Kastellorizo contained a sizable Muslim population of Greek origin. Before the Greek Revolution there were also Muslims on the island of Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poi ...

, but there were no Muslims in Cycladic

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The nam ...

or Sporades

The (Northern) Sporades (; el, Βόρειες Σποράδες, ) are an archipelago along the east coast of Greece, northeast of the island of Euboea,"Skyros - Britannica Concise" (description), Britannica Concise, 2006, webpageEB-Skyrosnotes " ...

island groups. Evliya Chelebi mentions that there were 100 Muslim houses on the island of Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born on the island an ...

in 1660s. On most Islands Muslims were only living in and around the main centers of the islands. Today Greek-speaking Muslims numbering about 5-5,500 live on Kos and Rhodes because Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited ...

Islands then governed by Italy were not a part of Greece and therefore they were exempt from the population exchange. However many migrated after Paris Peace Treaties in 1947.

Crimea

In the Middle Ages the Greek population ofCrimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

traditionally adhered to Eastern Orthodox Christianity

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

, even despite undergoing linguistic assimilation by the local Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace ...

. In 1777–1778, when Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

of Russia conquered the peninsula from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, the local Orthodox population was forcibly deported and settled north of the Azov Sea

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch ...

. In order to avoid deportation, some Greeks chose to convert to Islam. Crimean Tatar-speaking Muslims of the village of Kermenchik (renamed to Vysokoe in 1945) kept their Greek identity and were practising Christianity in secret for a while. In the nineteenth century the lower half of Kermenchik was populated with Christian Greeks from Turkey, whereas the upper remained Muslim. By the time of the Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

ist deportation of 1944, the Muslims of Kermenchik had already been identified as Crimean Tatars, and were forcibly expelled to Central Asia together with the rest of Crimea's ethnic minorities.

Lebanon and Syria

There are about 7,000 Greek-speaking Muslims living in Tripoli,Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

and about 8,000 in Al Hamidiyah, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

.Greek-Speaking Enclaves of Lebanon and Syriaby Roula Tsokalidou. Proceedings ''II Simposio Internacional Bilingüismo''. Retrieved 4 December 2006 The majority of them are Muslims of Cretan origin. Records suggest that the community left Crete between 1866 and 1897, on the outbreak of the last Cretan uprising against the Ottoman Empire, which ended the

Greco-Turkish War of 1897

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, Ατυχής πόλεμος, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

. Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

provided Cretan Muslim

The Cretan Muslims ( el, Τουρκοκρητικοί or , or ; tr, Giritli, , or ; ar, أتراك كريت) or Cretan Turks were the Muslim inhabitants of the island of Crete. Their descendants settled principally in Turkey, the Dodecane ...

families who fled the island with refuge on the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

ine coast. The new settlement was named Hamidiye after the sultan.

Many Grecophone Muslims of Lebanon somewhat managed to preserve their Cretan Muslim identity and Greek language Unlike neighbouring communities, they are monogamous

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time ( serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., pol ...

and consider divorce a disgrace. Until the Lebanese Civil War

The Lebanese Civil War ( ar, الحرب الأهلية اللبنانية, translit=Al-Ḥarb al-Ahliyyah al-Libnāniyyah) was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 120,000 fatalities a ...

, their community was close-knit and entirely endogamous

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting those from others as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships.

Endogamy is common in many cultu ...

. However many of them left Lebanon during the 15 years of the war.

Greek-speaking MuslimsWerner, Arnold (2000). "The Arabic dialects in the Turkish province of Hatay and the Aramaic dialects in the Syrian mountains of Qalamun: two minority languages compared". In Owens, Jonathan, (ed.). ''Arabic as a minority language''. Walter de Gruyter. p. 358. "Greek speaking Cretan Muslims". constitute 60% of Al Hamidiyah's population. The percentage may be higher but is not conclusive because of hybrid relationship in families. The community is very much concerned with maintaining its culture. The knowledge of the spoken Greek language is remarkably good and their contact with their historical homeland has been possible by means of satellite television and relatives. They are also known to be monogamous. Today, Grecophone Hamidiyah residents identify themselves as Cretan Muslims, while some others as Cretan Turks.

By 1988, many Grecophone Muslims from both Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

had reported being subject to discrimination by the Greek embassy because of their religious affiliation. The community members would be regarded with indifference and even hostility, and would be denied visas and opportunities to improve their Greek through trips to Greece.

Central Asia

In theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, after the Seljuq victory over the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

Emperor Romanus IV

Romanos IV Diogenes (Greek: Ρωμανός Διογένης), Latinized as Romanus IV Diogenes, was a member of the Byzantine military aristocracy who, after his marriage to the widowed empress Eudokia Makrembolitissa, was crowned Byzantine Em ...

, many Byzantine Greeks

The Byzantine Greeks were the Greek-speaking Eastern Romans of Orthodox Christianity throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. They were the main inhabitants of the lands of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire), of Constantinople ...