Great Syrian Revolt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great Syrian Revolt ( ar, الثورة السورية الكبرى) or Revolt of 1925 was a general uprising across the State of Syria and

The

The

On 6 May 1916,

On 6 May 1916,

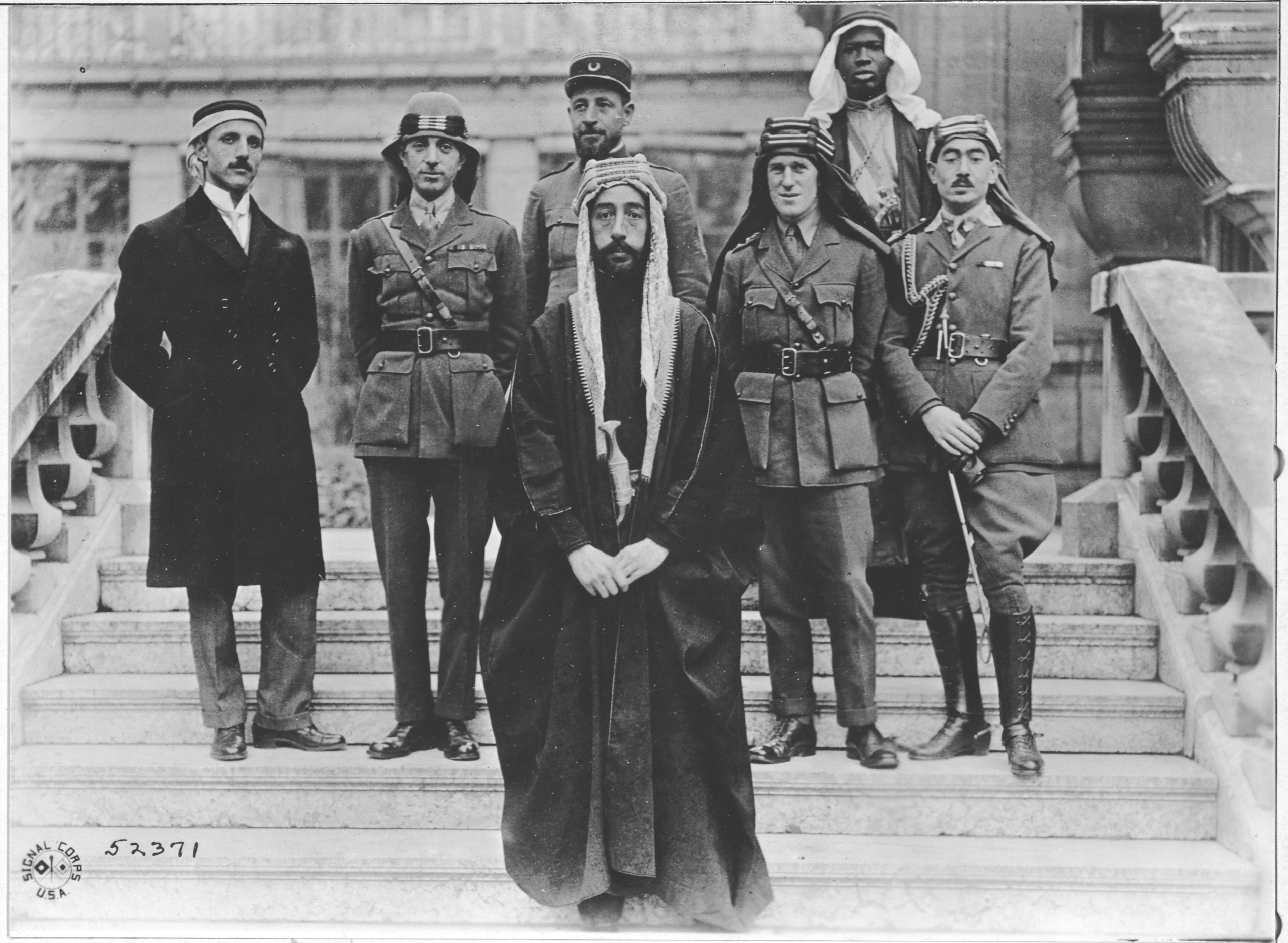

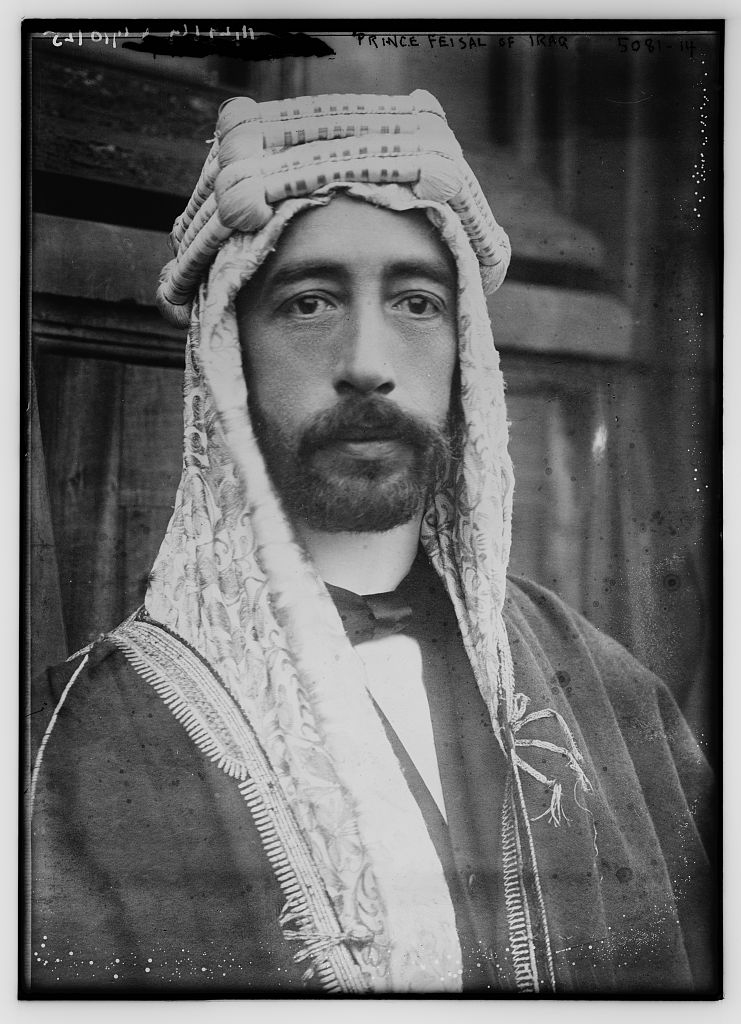

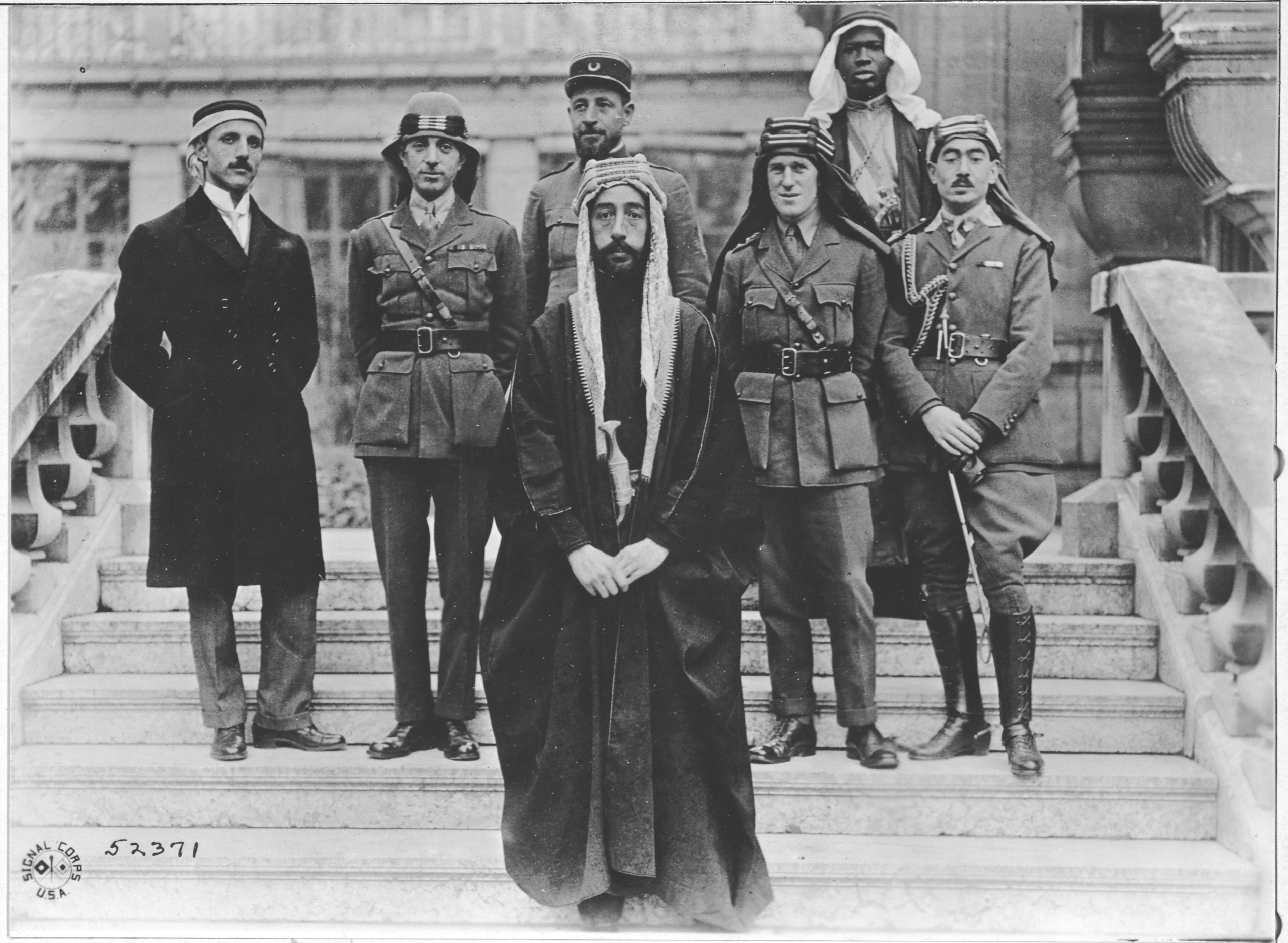

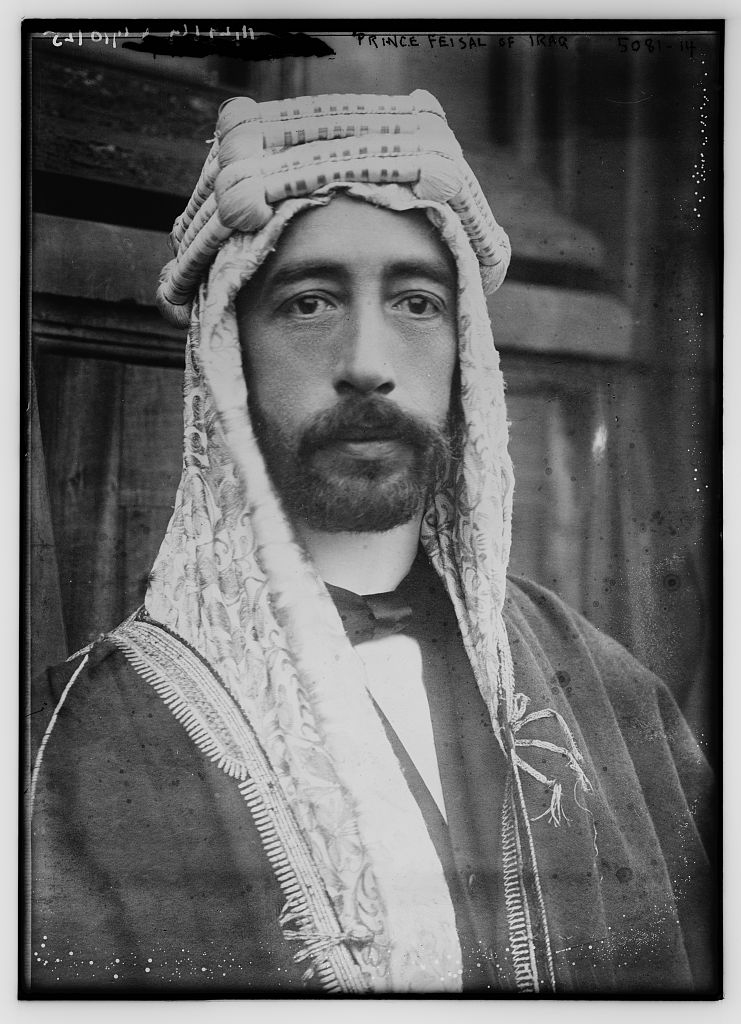

After the demise of Ottoman rule, Prince Faisal announced the establishment of an Arab government in Damascus and assigned the former Ottoman officer in Damascus, Ali Rikabi (Ali Rida Pasha Rikabi) to form and preside it as a military governor.

It included three ministers from the former Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, one from Beirut, one from Damascus and

After the demise of Ottoman rule, Prince Faisal announced the establishment of an Arab government in Damascus and assigned the former Ottoman officer in Damascus, Ali Rikabi (Ali Rida Pasha Rikabi) to form and preside it as a military governor.

It included three ministers from the former Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, one from Beirut, one from Damascus and  Prince Faisal returned to Syria on 23 April 1919 in preparation for the visit of the King–Crane Commission, and he appointed Awni Abd al-Hadi to membership of the peace conference. A sizeable meeting was held under Mohammad Fawzi Al-Azm at the Arab Club Hall in Damascus.

Prince Faisal gave the opening speech in which he explained the purpose and nature of the King–Crane Commission. The King–Crane Commission, which lasted for 42 days, visited 36 Arab cities and listened to 1,520 delegations from different villages all of them demanded independence and unity. On 3 July 1919, the delegation of the Syrian Conference met with the King–Crane Commission. It informed them of their request for the independence of Greater Syria and the establishment of a monarchy.

After the King–Crane Commission concluded its work, its recommendations stated that "the Levant rejects foreign control, and it is proposed to impose the mandate system under the tutelage of the League of Nations, as the Arabs are unanimously agreed that Prince Faisal should be a king on the Arab lands without fragmentation."

The King–Crane Commission delivered its report to the United States President,

Prince Faisal returned to Syria on 23 April 1919 in preparation for the visit of the King–Crane Commission, and he appointed Awni Abd al-Hadi to membership of the peace conference. A sizeable meeting was held under Mohammad Fawzi Al-Azm at the Arab Club Hall in Damascus.

Prince Faisal gave the opening speech in which he explained the purpose and nature of the King–Crane Commission. The King–Crane Commission, which lasted for 42 days, visited 36 Arab cities and listened to 1,520 delegations from different villages all of them demanded independence and unity. On 3 July 1919, the delegation of the Syrian Conference met with the King–Crane Commission. It informed them of their request for the independence of Greater Syria and the establishment of a monarchy.

After the King–Crane Commission concluded its work, its recommendations stated that "the Levant rejects foreign control, and it is proposed to impose the mandate system under the tutelage of the League of Nations, as the Arabs are unanimously agreed that Prince Faisal should be a king on the Arab lands without fragmentation."

The King–Crane Commission delivered its report to the United States President,  In late June 1919, Prince Faisal convened the Syrian National Congress, That was considered as a parliament of the Levant and was composed of 85 members, but France prevented some deputies from coming to Damascus. The conference opened with the presence of 69 deputies and among the most prominent of its member:

In late June 1919, Prince Faisal convened the Syrian National Congress, That was considered as a parliament of the Levant and was composed of 85 members, but France prevented some deputies from coming to Damascus. The conference opened with the presence of 69 deputies and among the most prominent of its member:

# Taj al-Din al-Hasani and Fawzi al-Azm representing Damascus

# Ibrahim Hananu representing the

# Taj al-Din al-Hasani and Fawzi al-Azm representing Damascus

# Ibrahim Hananu representing the

Yusuf al-Azma wanted to preserve the prestige and dignity of Syria's military history, was afraid to record in the history books that the Syrian Army stayed away from fighting and that the military occupation of his capital had happened without resistance. He also wanted to inform the Syrian people that their army carried the banner of resistance against the French occupation from the first moment, and that they would be a beacon for them in their resistance against the military occupation.

General Goabiah's forces consisted of the following:

# an infantry brigade (415)

# 2nd Regiment of Algerian

Yusuf al-Azma wanted to preserve the prestige and dignity of Syria's military history, was afraid to record in the history books that the Syrian Army stayed away from fighting and that the military occupation of his capital had happened without resistance. He also wanted to inform the Syrian people that their army carried the banner of resistance against the French occupation from the first moment, and that they would be a beacon for them in their resistance against the military occupation.

General Goabiah's forces consisted of the following:

# an infantry brigade (415)

# 2nd Regiment of Algerian

After France obtained control over the entire Syrian territories they resorted to the fragmentation of Syria into several independent states or entities:

*

After France obtained control over the entire Syrian territories they resorted to the fragmentation of Syria into several independent states or entities:

*

The outbreak of the revolution had many reasons, the most important of which are:

* The Syrians rejected the French occupation of their country, and sought full independence.

* Tearing Syria into several small states (Aleppo, Druze, Alawites, Damascus).

* The great economic damage caused to the Syrian merchants as a result of the policy adopted by the French in Syria, where the French dominated the economic aspects and linked the Syrian and

The outbreak of the revolution had many reasons, the most important of which are:

* The Syrians rejected the French occupation of their country, and sought full independence.

* Tearing Syria into several small states (Aleppo, Druze, Alawites, Damascus).

* The great economic damage caused to the Syrian merchants as a result of the policy adopted by the French in Syria, where the French dominated the economic aspects and linked the Syrian and

Colonel Catro, who was dispatched by General Gouraud to Jabal al-Druze, sought to isolate the Druze from the Syrian national movement, he signed on 4 March 1921 a treaty with the Druze tribes, which stipulated that Jabal al-Druze would form a particular administrative unit independent of the State of Damascus with a local governor and an elected representative council. In exchange for the Druze's recognition of the French mandate, the result of the treaty appointed Salim al-Atrash as the first ruler of the Jabal Druze State.

The Jabal Druze inhabitants were not comfortable with the new French administration and the first clash with it occurred in July 1922 with the arrest of

Colonel Catro, who was dispatched by General Gouraud to Jabal al-Druze, sought to isolate the Druze from the Syrian national movement, he signed on 4 March 1921 a treaty with the Druze tribes, which stipulated that Jabal al-Druze would form a particular administrative unit independent of the State of Damascus with a local governor and an elected representative council. In exchange for the Druze's recognition of the French mandate, the result of the treaty appointed Salim al-Atrash as the first ruler of the Jabal Druze State.

The Jabal Druze inhabitants were not comfortable with the new French administration and the first clash with it occurred in July 1922 with the arrest of  Salim Al-Atrash died poisoned in Damascus in 1924; the French appointed captain Carbillet as governor of the Jabal Druze State, contrary to the agreement with the Druze, Where he abused the people and exposed them to forced labour and persecution nad sent them to prison. He also worked on the implementation of a policy of divide and conquer by inciting farmers against their feudal lords, especially the Al-Atrash family. This led the people of As-Suwayda to go out in a mass protest against the practices of the French authorities, which accelerated the outbreak of the revolution.

The Druze were fed up with the practices of captain Carbillet, which led them to send a delegation to Beirut on 6 June 1925 to submit a document requesting the

Salim Al-Atrash died poisoned in Damascus in 1924; the French appointed captain Carbillet as governor of the Jabal Druze State, contrary to the agreement with the Druze, Where he abused the people and exposed them to forced labour and persecution nad sent them to prison. He also worked on the implementation of a policy of divide and conquer by inciting farmers against their feudal lords, especially the Al-Atrash family. This led the people of As-Suwayda to go out in a mass protest against the practices of the French authorities, which accelerated the outbreak of the revolution.

The Druze were fed up with the practices of captain Carbillet, which led them to send a delegation to Beirut on 6 June 1925 to submit a document requesting the  High commissioner Sarrail expelled the Jabal Druze State delegation and refused to meet them and notified them that they must leave Beirut quickly and return to their country or he will exile them to

High commissioner Sarrail expelled the Jabal Druze State delegation and refused to meet them and notified them that they must leave Beirut quickly and return to their country or he will exile them to  Shahbandar also met with leader Mohammed Al-Ayyash in Damascus and agreed with him to extend the revolution to the eastern region. Mohammed Al-Ayyash was able to form revolutionary groups to strike the French forces in Deir ez-Zor, and the rebels succeeded in carrying out strikes against the French forces. One of these was killing of French officers in the Ain Albu Gomaa area on the road between Deir ez-Zor and

Shahbandar also met with leader Mohammed Al-Ayyash in Damascus and agreed with him to extend the revolution to the eastern region. Mohammed Al-Ayyash was able to form revolutionary groups to strike the French forces in Deir ez-Zor, and the rebels succeeded in carrying out strikes against the French forces. One of these was killing of French officers in the Ain Albu Gomaa area on the road between Deir ez-Zor and  On 4 October 1925, Al-Qawuqji declared a revolution in Hama and its environs. It would have almost taken over the city had it not been for the heavy bombing of popular neighbourhoods. He went to the desert to provoke the tribes against the French and relieve pressure on the rebels in other regions, and achieved significant victories over the French troops, garrisons and barracks and inflicted heavy losses on them; even the National Revolutionary Council entrusted him with leading the revolution in the Ghouta region and granting him broad powers.

On 11 July 1925, French high commissioner Maurice Sarrail sent a secret letter to his delegate in Damascus asking him to summon some of the leaders of the Jabal al-Druze under the pretext of discussing with them their demands, to arrest them and exile them to Palmyra and Al-Hasakah. This was done and Uqlat al-Qatami, Prince Hamad al-Atrash, Abdul Ghaffar al-Atrash, and Naseeb al-Atrash were exiled to Palmyra, while Barjas al-Homoud, Hosni Abbas, Ali al-Atrash, Yusuf al-Atrash, and Ali Obaid were exiled to Al-Hasakah.

As a result of French policies and practices, Sultan al-Atrash declared the revolution on 21 July 1925 by broadcasting a political and military statement calling on the Syrian people to revolt against the French mandate.

On 4 October 1925, Al-Qawuqji declared a revolution in Hama and its environs. It would have almost taken over the city had it not been for the heavy bombing of popular neighbourhoods. He went to the desert to provoke the tribes against the French and relieve pressure on the rebels in other regions, and achieved significant victories over the French troops, garrisons and barracks and inflicted heavy losses on them; even the National Revolutionary Council entrusted him with leading the revolution in the Ghouta region and granting him broad powers.

On 11 July 1925, French high commissioner Maurice Sarrail sent a secret letter to his delegate in Damascus asking him to summon some of the leaders of the Jabal al-Druze under the pretext of discussing with them their demands, to arrest them and exile them to Palmyra and Al-Hasakah. This was done and Uqlat al-Qatami, Prince Hamad al-Atrash, Abdul Ghaffar al-Atrash, and Naseeb al-Atrash were exiled to Palmyra, while Barjas al-Homoud, Hosni Abbas, Ali al-Atrash, Yusuf al-Atrash, and Ali Obaid were exiled to Al-Hasakah.

As a result of French policies and practices, Sultan al-Atrash declared the revolution on 21 July 1925 by broadcasting a political and military statement calling on the Syrian people to revolt against the French mandate.

Al-Atrash started military attacks on French forces and burned the French Commission's house in

Al-Atrash started military attacks on French forces and burned the French Commission's house in  On 20 August 1925, the People's Party sent a delegation to meet with Sultan al-Atrash and discuss the accession of Damascus to the revolution; the delegation included Tawfiq al-Halabi, Asaad al-Bakri, and Zaki al-Droubi. The presence of the delegation coincided with the presence of Captain Reno, who was negotiating with the rebels on behalf of the French authorities to conclude a peace treaty, and the People's Party delegation managed to convince the rebels not to sign the treaty. In late August 1925, the leaders of the People's Party, including Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar, met with Sultan al-Atrash in the village of Kafr al-Lehaf and agreed to mobilize five hundred rebels to attack Damascus from three axis, but Al-Atrash could not mobilize this number. The military forces that General Ghamlan began to mobilize along the railway in Horan led the rebel leaders to abandon the plan to attack Damascus and devote themselves to the French campaign.

The rebels agreed to march towards the village of

On 20 August 1925, the People's Party sent a delegation to meet with Sultan al-Atrash and discuss the accession of Damascus to the revolution; the delegation included Tawfiq al-Halabi, Asaad al-Bakri, and Zaki al-Droubi. The presence of the delegation coincided with the presence of Captain Reno, who was negotiating with the rebels on behalf of the French authorities to conclude a peace treaty, and the People's Party delegation managed to convince the rebels not to sign the treaty. In late August 1925, the leaders of the People's Party, including Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar, met with Sultan al-Atrash in the village of Kafr al-Lehaf and agreed to mobilize five hundred rebels to attack Damascus from three axis, but Al-Atrash could not mobilize this number. The military forces that General Ghamlan began to mobilize along the railway in Horan led the rebel leaders to abandon the plan to attack Damascus and devote themselves to the French campaign.

The rebels agreed to march towards the village of  In late October 1925, the rebels of the Jabal al-Druze gathered in the northern Almeqren and then marched west, occupying the region of Alblan and then the town of

In late October 1925, the rebels of the Jabal al-Druze gathered in the northern Almeqren and then marched west, occupying the region of Alblan and then the town of

The

The

Ibrahim Hananu was born to a wealthy family in

Ibrahim Hananu was born to a wealthy family in

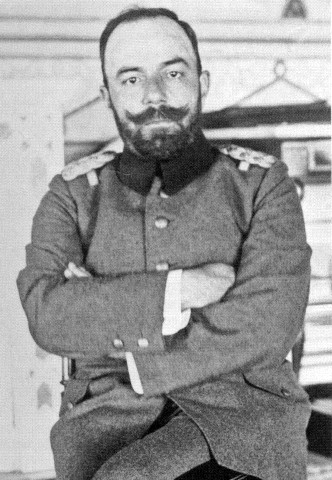

Fawzi al-Qawuqji was an officer in the Syrian army and the leader of the Salvation Army during the 1948 war, was born in the city of Tripoli in the Ottoman Empire, studied at the Military School in Astana, and graduated as an officer in the Ottoman Cavalry Corps in 1912, worked in the service of King Faisal in Damascus.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji lived in Damascus and was distinguished by his rare courage and Arabism that prompted him to fight battles against European colonialism in all Arab regions.

During the French Mandate, he became commander of a cavalry company in Hama, later defected from the Syrian Legion set up by the French in Syria to participate in the Great Syrian Revolution against the French, and on October 4, 1925, he led a revolution in Hama against the French occupation, which he planned jointly with Saeed Al-Termanini and Munir Al-Rayes. The Syrian revolutionaries took control of the city, the third-largest city in Syria, with about 80,000. The revolutionaries cut the telephone lines and attacked and burned the Government House, where they captured some French officers and then besieged the French military positions.

The next day, France bombarded the city with aircraft and artillery for three days. After negotiations, some of the city's notables persuaded al-Qawuqji to withdraw to save the population's blood, and the battles continued in its vicinity. The bombing of Hama resulted in 344 deaths, the vast majority of them civilians, although France claimed that the death toll did not exceed 76, all of whom were revolutionaries. Some sources estimate the number of civilian casualties at about 500, the losses of the French as 400 dead and wounded, and the losses of the rebels 35; the material losses were also great, as 115 shops were destroyed. He was later assigned to lead the revolution in the Ghouta area of Damascus.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji was an officer in the Syrian army and the leader of the Salvation Army during the 1948 war, was born in the city of Tripoli in the Ottoman Empire, studied at the Military School in Astana, and graduated as an officer in the Ottoman Cavalry Corps in 1912, worked in the service of King Faisal in Damascus.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji lived in Damascus and was distinguished by his rare courage and Arabism that prompted him to fight battles against European colonialism in all Arab regions.

During the French Mandate, he became commander of a cavalry company in Hama, later defected from the Syrian Legion set up by the French in Syria to participate in the Great Syrian Revolution against the French, and on October 4, 1925, he led a revolution in Hama against the French occupation, which he planned jointly with Saeed Al-Termanini and Munir Al-Rayes. The Syrian revolutionaries took control of the city, the third-largest city in Syria, with about 80,000. The revolutionaries cut the telephone lines and attacked and burned the Government House, where they captured some French officers and then besieged the French military positions.

The next day, France bombarded the city with aircraft and artillery for three days. After negotiations, some of the city's notables persuaded al-Qawuqji to withdraw to save the population's blood, and the battles continued in its vicinity. The bombing of Hama resulted in 344 deaths, the vast majority of them civilians, although France claimed that the death toll did not exceed 76, all of whom were revolutionaries. Some sources estimate the number of civilian casualties at about 500, the losses of the French as 400 dead and wounded, and the losses of the rebels 35; the material losses were also great, as 115 shops were destroyed. He was later assigned to lead the revolution in the Ghouta area of Damascus.

The revolution achieved great results in the national struggle and the quest for complete independence from France. The most prominent of these results are:

# These big moves greatly destabilized the policy of the French in Syria, and they became fully convinced that the people of Syria would not succumb and that a Syrian national government must be established and yielding to the will of the people and their great revolution. They also became fully convinced of the need to leave Syria and grant it complete independence. Representative Sixt Quantin proposed to return Syria and Lebanon to the custody of the League of Nations to get rid of the blood spilled in them and the expenses. His proposal won two hundred votes out of four hundred and eighty votes.

# The revolution led to the resurrection of the movement calling for the establishment of a royal government in Syria, as supporters of this project see it as the only guarantee for the establishment of sincere and continuous cooperation to implement the Mandate. Ali bin Al Hussein was the candidate for this throne, but the project failed due to the Syrians’ rejection.

# The revolution forced France to reunify Syria after dividing it into four states (Damascus, Aleppo, Jabal Alawites, and Jabal al-Druze).

# It was forced to agree to hold elections in which the national opposition, led by Ibrahim Hananu and Hashim al-Atassi, won.

# France was forced to carry out administrative reforms by removing its high commissioner and its military officers in Syria and appointing replacements for them, as happened, for example, with high commissioner Sarail after the revolutionaries attacked Qasr al-Azm in Damascus, so it set a new civilian delegate, de Jouvenel.

# France was forced to send its most prominent leaders in the First World War, such as General Gamelin, after the increasing strength of the revolutionaries and their victories.

# It paved the way for the final exit of the French from Syria in 1946, as the struggle continued in its political form.

# Damascus was bombed by air for 24 continuous hours, and some villages in Jabal al-Druze were emptied of their residents as a result of their destruction and burning.

# The revolution was a victory for national and patriotic awareness over regionalism and sectarianism, as the most important slogans launched by its leader were a religion for God and the homeland for all.

The revolution achieved great results in the national struggle and the quest for complete independence from France. The most prominent of these results are:

# These big moves greatly destabilized the policy of the French in Syria, and they became fully convinced that the people of Syria would not succumb and that a Syrian national government must be established and yielding to the will of the people and their great revolution. They also became fully convinced of the need to leave Syria and grant it complete independence. Representative Sixt Quantin proposed to return Syria and Lebanon to the custody of the League of Nations to get rid of the blood spilled in them and the expenses. His proposal won two hundred votes out of four hundred and eighty votes.

# The revolution led to the resurrection of the movement calling for the establishment of a royal government in Syria, as supporters of this project see it as the only guarantee for the establishment of sincere and continuous cooperation to implement the Mandate. Ali bin Al Hussein was the candidate for this throne, but the project failed due to the Syrians’ rejection.

# The revolution forced France to reunify Syria after dividing it into four states (Damascus, Aleppo, Jabal Alawites, and Jabal al-Druze).

# It was forced to agree to hold elections in which the national opposition, led by Ibrahim Hananu and Hashim al-Atassi, won.

# France was forced to carry out administrative reforms by removing its high commissioner and its military officers in Syria and appointing replacements for them, as happened, for example, with high commissioner Sarail after the revolutionaries attacked Qasr al-Azm in Damascus, so it set a new civilian delegate, de Jouvenel.

# France was forced to send its most prominent leaders in the First World War, such as General Gamelin, after the increasing strength of the revolutionaries and their victories.

# It paved the way for the final exit of the French from Syria in 1946, as the struggle continued in its political form.

# Damascus was bombed by air for 24 continuous hours, and some villages in Jabal al-Druze were emptied of their residents as a result of their destruction and burning.

# The revolution was a victory for national and patriotic awareness over regionalism and sectarianism, as the most important slogans launched by its leader were a religion for God and the homeland for all.

The Great Syrian Revolution Monument Museum in As-Suwayda tells the revolutionaries’ exploits and heroisms, an article published on the Discover Syria website.

online

* Anne-Marie Bianquis et Elizabeth Picard, ''Damas, miroir brisé d'un orient arabe'', édition Autrement, Paris 1993. * Lenka Bokova, ''La confrontation franco-syrienne à l'époque du mandat – 1925–1927'', éditions l'Harmattan, Paris, 1990 * Général Andréa, ''La Révolte druze et l'insurrection de Damas, 1925–1926'', éditions Payot, 1937 * ''Le Livre d'or des troupes du Levant : 1918–1936.'', Préfacier Huntziger, Charles Léon Clément, Gal. (S. l.), Imprimerie du Bureau typographique des troupes du Levant, 1937.

{{Authority control

Great Syrian Revolt

1925 in Mandatory Syria

1926 in Mandatory Syria

1927 in Mandatory Syria

Conflicts in 1925

Conflicts in 1926

Conflicts in 1927

Mandatory Syria

Military history of Syria

Military history of France

1920s in France

France–Syria relations

France–Lebanon relations

French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon

League of Nations mandates

20th century in Lebanon

20th century in Syria

History of the Levant

Mandate for Syria

Mandate for Syria

Sykes–Picot Agreement

Greater Lebanon

The State of Greater Lebanon ( ar, دولة لبنان الكبير, Dawlat Lubnān al-Kabīr; french: État du Grand Liban), informally known as French Lebanon, was a state declared on 1 September 1920, which became the Lebanese Republic ( ar, ...

during the period of 1925 to 1927. The leading rebel forces comprised fighters of the Jabal Druze State

Jabal al-Druze ( ar, جبل الدروز, french: Djebel Druze) was an autonomous state in the French Mandate of Syria from 1921 to 1936, designed to function as a government for the local Druze population under French oversight.

Nomenclat ...

in southern Syria, joined by Sunni, Druze, Alawite, and Christian factions. The common goal was to end French rule in the newly mandated regions, passed from Turkish to French administration following World War I.

This revolution came in response to the repressive policies pursued by the French authorities under the Mandate for Syria and Lebanon

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

, in dividing Syria into several occupied territories. The new French administration was perceived as being prejudiced against the dominant Arab culture

Arab culture is the culture of the Arabs, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. The various religions the Arab ...

and of intending to change the existing character of the country. In addition resentment was caused by the refusal of the French authorities to set a timetable for the independence of Syria.

This revolution was an extension of the Syrian uprisings that had begun when French colonial forces occupied the coastal regions in early 1920, and continued until late June 1927. While the French army and local collaborators were able to achieve military victory, extensive Syrian resistance obliged the occupying authorities to establish a national government of Syria

Government of the Syrian Arab Republic is the union government created by the constitution of Syria where by the president is the head of state and the prime minister is the head of government. Executive power is exercised by the government. Sy ...

, under which the divided territories were reunited. In addition parliamentary elections were held as a preliminary step towards the final departure of the French from Syria in 1946.

The Arab region after the First World War

The

The First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

led to the collapse or dissolution of the Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

, the Austro-Hungarian, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, and Ottoman empires, the later of which Syria had been part of for centuries. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire encouraged the United Kingdom and France to share its legacy by creating a new colonial concept known as the mandate.

The main idea is that the former geographic possessions of the collapsed states that disappeared at the end of the First World War would be placed under the supervision of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

; in practice this applied to Germany's colonies in Africa and those regions of Ottoman Empire not retained by Turkey.

Based on this, France took over Syria and Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

, while the United Kingdom took Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

and Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

, and these countries are placed under the direct guardianship of these two countries with an official mandate from the League of Nations, with the task of insuring to these new countries the necessary means to enable them to reach a sufficient degree of political awareness and economic development

In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and ...

qualifies them for independence and sovereignty. In the implementation of these plans, negotiations were held between France and the United Kingdom in October 1915 on the determination of the spheres of influence of both countries in the event of the partition of the Ottoman Empire. The secret agreement on the subject was called the Sykes–Picot Agreement after the names of the two negotiators, Britain's Mark Sykes and Frenchman, François Georges-Picot.

Meanwhile, correspondence had been ongoing since 1915 between Sir Henry McMahon

Sir Arthur Henry McMahon (28 November 1862 – 29 December 1949) was a British Indian Army officer and diplomat who served as the High Commissioner in Egypt from 1915 to 1917. He was also an administrator in British India and served twice as ...

and Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca ( ar, شريف مكة, Sharīf Makkah) or Hejaz ( ar, شريف الحجاز, Sharīf al-Ḥijāz, links=no) was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and ...

in the Hejaz, and as a result of the negotiations between the two parties, The British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

presented a written commitment, includes the recognition of the independence of the Arabs and support them, and in exchange for this initial promise, Hussein bin Ali is committed to launching a call for the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

against the Ottomans.

The Great Arab revolution

On 6 May 1916,

On 6 May 1916, Djemal Pasha

Ahmed Djemal ( ota, احمد جمال پاشا, Ahmet Cemâl Paşa; 6 May 1872 – 21 July 1922), also known as Cemal Pasha, was an Ottoman military leader and one of the Three Pashas that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

Djemal w ...

executed fourteen Syrian notables in Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

and Damascus and this was the catalyst for Hussein bin Ali to start the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The aim of the revolution, as stated in the Damascus Charter and in the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence

The McMahon–Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during World War I in which the Government of the United Kingdom agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war in exchange for the Sharif ...

, which was based on the Charter, was removing the Ottoman Empire and establishment of an Arab state or union of Arab states including the Arabian Peninsula, Najd, Hejaz in particular and Greater Syria, except Adana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, wh ...

, which was considered within Syria in the Damascus Charter. With respect for Britain's interests in southern Iraq, a geographical area that begins in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

and ends in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

.

On 10 June 1916, the Arab Revolt began in Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

and in November 1916, Hussein bin Ali declared himself "King of the Arabs," while the superpowers only recognized him as king of the Hejaz. He had 1,500 soldiers and some of armed tribesmen, Hussein bin Ali's army had no guns and Britain provided him with two cannons that accelerated the fall of Jeddah and Taif

Taif ( ar, , translit=aṭ-Ṭāʾif, lit=The circulated or encircled, ) is a city and governorate in the Makkan Region of Saudi Arabia. Located at an elevation of in the slopes of the Hijaz Mountains, which themselves are part of the Sarat M ...

.

Then he went to Aqaba

Aqaba (, also ; ar, العقبة, al-ʿAqaba, al-ʿAgaba, ) is the only coastal city in Jordan and the largest and most populous city on the Gulf of Aqaba. Situated in southernmost Jordan, Aqaba is the administrative centre of the Aqaba Govern ...

, where the second phase of the revolution officially began in late 1917 supported by the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

that occupied Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

on 9 September 1917 and before the end of the year all of the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem

The Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem ( ota, مُتَصَرِّف قدسی مُتَصَرِّفلغ, ; ar, متصرفية القدس الشريف, ), also known as the Sanjak of Jerusalem, was an Ottoman district with special administrative status ...

was under British rule.

In the meantime, the army of Hussein bin Ali was increasing, they were joined by two thousand armed soldiers, led by Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni ( ar, عبد القادر الحسيني), also spelled Abd al-Qader al-Husseini (1907 – 8 April 1948) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and fighter who in late 1933 founded the secret militant group known as the Orga ...

from Jerusalem. Most of the tribesmen from the surrounding areas joined the revolution.

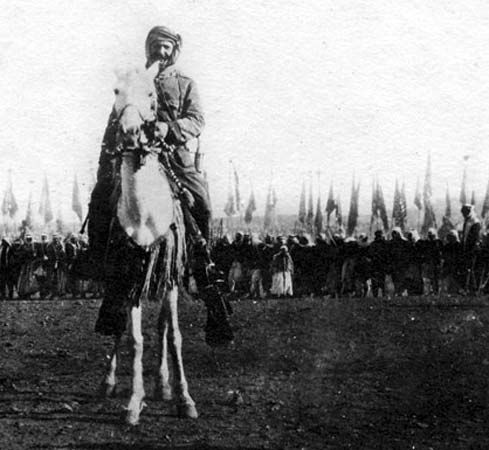

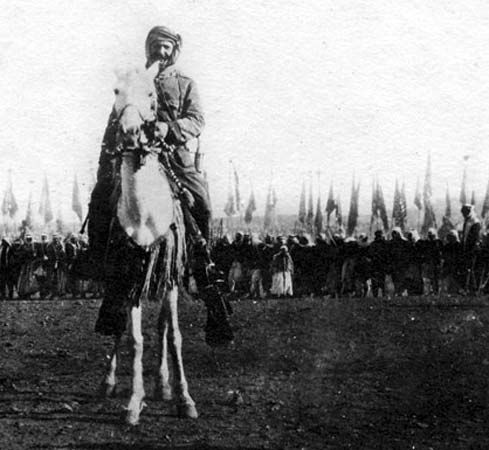

The Sharifian Army

The Sharifian Army ( ar, الجيش الشريفي, links=yes), also known as the Arab Army ( ar, الجيش العربي, links=yes), or the Hejazi Army ( ar, الجيش الحجازي, links=yes) was the military force behind the Arab Revolt wh ...

, was formed under the leadership of Hussein bin Ali and his son Faisal and indirectly commanded by the British officer T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

(Lawrence of Arabia). It headed to Syria and clashed with the Ottoman forces in a decisive battle near Ma'an

Ma'an ( ar, مَعان, Maʿān) is a city in southern Jordan, southwest of the capital Amman. It serves as the capital of the Ma'an Governorate. Its population was approximately 41,055 in 2015. Civilizations with the name of Ma'an have existe ...

. The war resulted in almost destruction of the seventh army and the second Ottoman army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

, Ma'an was liberated on 23 September 1918, followed by Amman on 25 September and the day before 26 September, the Ottoman governor and his soldiers had left Damascus to announcing the end of Ottoman Syria.

The Sharifian Army entered Damascus on 30 September 1918 and on 8 October the British Army entered Beirut and General Edmund Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 – 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World War, in which he led th ...

entered Syria and met with the Sharifian Army in Damascus.

On 18 October, the Ottomans left Tripoli, Lebanon

Tripoli ( ar, طرابلس/ ALA-LC: ''Ṭarābulus'', Lebanese Arabic: ''Ṭrablus'') is the largest city in northern Lebanon and the second-largest city in the country. Situated north of the capital Beirut, it is the capital of the North Gove ...

and Homs and on 26 October 1918, the British and Sharifian Army headed north until they met the last Ottoman forces under the command of Turkish commander Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and a fierce battle happened near to Aleppo in an area later renamed "the English Tomb". On 30 October 1918, the Armistice of Mudros

Concluded on 30 October 1918 and taking effect at noon the next day, the Armistice of Mudros ( tr, Mondros Mütarekesi) ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I. It was signed by th ...

was concluded and Ottoman forces surrendered and the Ottoman Empire abandoned the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, Iraq, Hejaz, 'Asir

The ʿAsir Region ( ar, عَسِيرٌ, ʿAsīr, lit=difficult) is a region of Saudi Arabia located in the southwest of the country that is named after the ʿAsīr tribe. It has an area of and an estimated population of 2,211,875 (2017). It is ...

and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

.

Arab Kingdom of Syria

After the demise of Ottoman rule, Prince Faisal announced the establishment of an Arab government in Damascus and assigned the former Ottoman officer in Damascus, Ali Rikabi (Ali Rida Pasha Rikabi) to form and preside it as a military governor.

It included three ministers from the former Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, one from Beirut, one from Damascus and

After the demise of Ottoman rule, Prince Faisal announced the establishment of an Arab government in Damascus and assigned the former Ottoman officer in Damascus, Ali Rikabi (Ali Rida Pasha Rikabi) to form and preside it as a military governor.

It included three ministers from the former Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, one from Beirut, one from Damascus and Sati' al-Husri

Sāṭi` al-Ḥuṣrī, born Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri,( ar, ساطع الحصري, August 1880 – 1968) was an Ottoman, Syrian and Iraqi writer, educationalist and an influential Arab nationalist thinker in the 20th century.

Early life

Of Sy ...

from Aleppo and the defence minister from Iraq. Trying to imply that this government represents Greater Syria and was not just a government of local Syria, Prince Faisal appointed Major General Shukri al-Ayyubi military governor of Beirut, Jameel Al-Madfaai governor of Amman, Abdulhamid al-Shalaji as commander of Damascus, and Ali Jawdat al-Ayyubi as governor of Aleppo.

Prince Faisal sought to build a Syrian Army capable of establishing security and stability and preserving the state entity to be declared. He asked the British to arm this army, but they refused. In late 1918 Prince Faisal was invited to participate in the Paris Peace Conference that was held after the First World War in Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

. He made calls on both the French and British governments who, while collaborating behind his back in amending the Sykes–Picot Agreement, assured the prince of their good intentions towards Syria.

Faisal proposed at the conference to establish three Arab governments; respectively in Hejaz, Syria and Iraq. However, the United States proposed the mandate system

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

, and sent a referendum committee, the King–Crane Commission, to gauge the political wishes of the people and the French and the British reluctantly agreed.

Prince Faisal returned to Syria on 23 April 1919 in preparation for the visit of the King–Crane Commission, and he appointed Awni Abd al-Hadi to membership of the peace conference. A sizeable meeting was held under Mohammad Fawzi Al-Azm at the Arab Club Hall in Damascus.

Prince Faisal gave the opening speech in which he explained the purpose and nature of the King–Crane Commission. The King–Crane Commission, which lasted for 42 days, visited 36 Arab cities and listened to 1,520 delegations from different villages all of them demanded independence and unity. On 3 July 1919, the delegation of the Syrian Conference met with the King–Crane Commission. It informed them of their request for the independence of Greater Syria and the establishment of a monarchy.

After the King–Crane Commission concluded its work, its recommendations stated that "the Levant rejects foreign control, and it is proposed to impose the mandate system under the tutelage of the League of Nations, as the Arabs are unanimously agreed that Prince Faisal should be a king on the Arab lands without fragmentation."

The King–Crane Commission delivered its report to the United States President,

Prince Faisal returned to Syria on 23 April 1919 in preparation for the visit of the King–Crane Commission, and he appointed Awni Abd al-Hadi to membership of the peace conference. A sizeable meeting was held under Mohammad Fawzi Al-Azm at the Arab Club Hall in Damascus.

Prince Faisal gave the opening speech in which he explained the purpose and nature of the King–Crane Commission. The King–Crane Commission, which lasted for 42 days, visited 36 Arab cities and listened to 1,520 delegations from different villages all of them demanded independence and unity. On 3 July 1919, the delegation of the Syrian Conference met with the King–Crane Commission. It informed them of their request for the independence of Greater Syria and the establishment of a monarchy.

After the King–Crane Commission concluded its work, its recommendations stated that "the Levant rejects foreign control, and it is proposed to impose the mandate system under the tutelage of the League of Nations, as the Arabs are unanimously agreed that Prince Faisal should be a king on the Arab lands without fragmentation."

The King–Crane Commission delivered its report to the United States President, Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

on 28 August 1919, who was ill. The report was ignored after Wilson changed his position because of opposition from senior United States politicians in the Senate (Congress), for violating the isolationist policy followed by the United States since 1833, which requires non-intervention in the affairs of Europe and the non-interference of Europe with the affairs of the United States.

Under pressure, Prince Faisal accepted an agreement with France represented by its prime minister Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

, known as the Faisal Clemenceau Agreement. Among the most prominent of its items:

* The French Mandate for Syria, while the country retains its internal independence, and Syria's cooperation with France about foreign and financial relations, and that Syrian ambassadors abroad reside within the French embassies.

* Recognition of Lebanon's independence under full French tutelage, and the borders to be set by allies without Beirut.

* Organization of the Druze of Hauran and Golan

Golan ( he, גּוֹלָן ''Gōlān''; ar, جولان ' or ') is the name of a biblical town later known from the works of Josephus (first century CE) and Eusebius (''Onomasticon'', early 4th century CE). Archaeologists localize the biblical ...

in a federation within the Syrian state.

In late June 1919, Prince Faisal convened the Syrian National Congress, That was considered as a parliament of the Levant and was composed of 85 members, but France prevented some deputies from coming to Damascus. The conference opened with the presence of 69 deputies and among the most prominent of its member:

In late June 1919, Prince Faisal convened the Syrian National Congress, That was considered as a parliament of the Levant and was composed of 85 members, but France prevented some deputies from coming to Damascus. The conference opened with the presence of 69 deputies and among the most prominent of its member:

# Taj al-Din al-Hasani and Fawzi al-Azm representing Damascus

# Ibrahim Hananu representing the

# Taj al-Din al-Hasani and Fawzi al-Azm representing Damascus

# Ibrahim Hananu representing the Harem District

Harem District ( ar-at, منطقة حارم, manṭiqat Ḥārim) is a district of the Idlib Governorate in northwestern Syria. The administrative centre is the city of Harem

Harem ( Persian: حرمسرا ''haramsarā'', ar, حَرِي ...

# Saadallah al-Jabiri, Reza Al-Rifai, Mar'i Pasha al-Mallah and Dr. Abdul Rahman Kayali representing Aleppo

# Fadel Al-Aboud

Fadel Aboud Al-Hassan or Haj Fadel Al-Aboud ( ar, الحاج فاضل العبود ) was a Syrian leader and head of the Haj Fadel government in eastern Syria after the Ottomans left the region in 1918.

Lineage

Fadel Al-Aboud was born in D ...

representing Deir ez-Zor

, population_urban =

, population_density_urban_km2 =

, population_density_urban_sq_mi =

, population_blank1_title = Ethnicities

, population_blank1 =

, population_blank2_title = Religions

, population_blank2 =

...

and the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers''). Originating in Turkey, the Eup ...

valley area

# Hikmat al-Hiraki representing Maarat al-Numan

Maarat al-Numan ( ar, مَعَرَّةُ النُّعْمَانِ, Maʿarrat an-Nuʿmān), also known as al-Ma'arra, is a city in northwestern Syria, south of Idlib and north of Hama, with a population of about 58,008 before the Civil War (2004 ...

# Abdul Qader Kilani and Khalid Barazi representing Hama

# Amin Husseini and Aref al-Dajani representing Jerusalem

# Salim Ali Salam, Aref Al Nomani, and Jamil Beyhoum representing Beirut

# Rashid Rida

Muḥammad Rashīd ibn ʿAlī Riḍā ibn Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn ibn Muḥammad Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Munlā ʿAlī Khalīfa (23 September 1865 or 18 October 1865 – 22 August 1935 CE/ 1282 - 1354 AH), widely known as Sayyid Rashid Rida ( ar, � ...

and Tawfiq El Bissar representing Tripoli

# Said Taliea and Ibrahim Khatib representing Mount Lebanon

Hashim al-Atassi

Hashim al-Atassi ( ar, هاشم الأتاسي, Hāšim al-ʾAtāsī; 11 January 1875 – 5 December 1960) was a Syrian nationalist and statesman and the President of Syria from 1936 to 1939, 1949 to 1951 and 1954 to 1955.

Background and e ...

was elected president of the Syrian National Congress, and Mar'i Pasha al-Mallah and Yusuf al-Hakim were vice-presidents. The Syrian National Congress decided to reject the Faisal Clemenceau agreement, demanding the unity and independence of Syria, accepting the mandate of the United States and Britain and rejecting the French mandate, but that the concept of the mandate is limited on technical assistance only.

The relationship between Faisal and French General Henri Gouraud was strained, following Faisal's retreat from his agreement with the French and his bias to the people. The Syrian government has requested 30,000 military uniforms to organize the army. On the other hand, the Clemenceau government fell in France and was replaced by the extreme right-wing government of Alexandre Millerand

Alexandre Millerand (; – ) was a French politician. He was Prime Minister of France from 20 January to 23 September 1920 and President of France from 23 September 1920 to 11 June 1924. His participation in Waldeck-Rousseau's cabinet at the s ...

. Later, France disputed the agreement, and In mid-November 1919, British Armed Forces began withdrawing from Syria after a one-year presence.

On 8 March 1920, the Syrian National Congress was held in Damascus under the leadership of Hashim al-Atassi and in the presence of Prince Faisal and members of the government. It lasted for two days with the participation of 120 members and came up with the following decisions:

# The independence of Syria as a country with its natural borders.

# His Royal Highness Prince Faisal bin Al Hussein was unanimously elected constitutional monarch over the country.

# The political system of the state is a civil, parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

, royal.

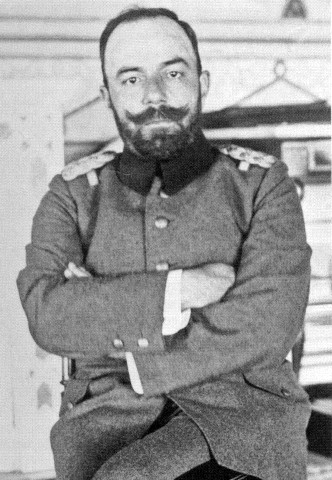

# Appointment of a civil property government, where Ali Reza Al-Rikabi was appointed as the commander-in-Chief of the Government and Yusuf al-Azma

Yusuf al-Azma ( ar, يوسف العظمة, ALA-LC: ''Yūsuf al-ʻAẓmah''; 1883 – 24 July 1920) was the Syrian minister of war in the governments of prime ministers Rida al-Rikabi and Hashim al-Atassi, and the Arab Army's chief of general st ...

as the Syrian Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

The official language becoming Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

instead of Turkish in all government institutions, civil and military official departments, and schools. Replacing the Ottoman lira

The lira (sign: LT) was the currency of Ottoman Empire between 1844 when it was replaced by the Turkish lira. The Ottoman lira remained in circulation until the end of 1927, as the republic was not in a position to issue its own banknotes yet in ...

with the Egyptian pound and later the Syrian pound.

# Rejecting the Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

, Balfour Declaration to make Palestine a national home for Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

.

# Reject British and French tutelage over Arabs.

The Allies refused to recognize the new state and decided in April 1920 at the San Remo conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Villa Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution pas ...

in Italy to divide the country into four areas under which Syria and Lebanon would be subject to the French mandate, the Emirate of Transjordan

The Emirate of Transjordan ( ar, إمارة شرق الأردن, Imārat Sharq al-Urdun, Emirate of East Jordan), officially known as the Amirate of Trans-Jordan, was a British protectorate established on 11 April 1921,

and Palestine to the British Mandate for Palestine. Although the Lebanon and Syrian coasts, as well as Palestine, were not under the military rule of the Arab Kingdom of Syria

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, No ...

, as the Allied armies had been there since the end of the First World War.

The government and the Syrian National Congress rejected the decisions of the San Remo conference and informed the Allied States of its decision between 13 and 21 May 1920. The voices were rising in Syria for an alliance with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

or the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in Russia, and meetings were held.

However, these meetings did not lead to a result because Atatürk was using the Syrians to improve the terms of his negotiations with the French and he turned his back to the Syrians. He concluded an agreement with France known as the Treaty of Ankara (Franklin-Bouillon Agreement) in 1921, which included a waiver of the French occupation authority from the northern Syrian territories and withdrawal of the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed Force ...

, and hand them over to Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

.

Syria under the French Mandate

The proclamation of the establishment of the Arab Kingdom of Syria had internal implications, reflecting tensions within both Syria and Lebanon. Muslims had attacked Christian villages in the Beqaa Valley in response to statements by theMaronite Patriarch

This is a list of the Maronite patriarchs of Antioch and all the East, the primate of the Maronite Church, one of the Eastern Catholic Churches. Starting with Paul Peter Massad in 1854, after becoming patriarch of the Maronite Catholic Patriarch ...

Elias Peter Hoayek

Elias Peter Hoayek ( ar, الياس بطرس الحويّك; 4 December 1843 – 24 December 1931; also spelled Hoyek, Hwayek, Huayek, Juayek, Hawayek, Houwayek) was the 72nd Patriarch of Antioch for the Maronites, the largest Christian Catholic ...

and the Board of Directors of Mount Lebanon, opposing the independence of Lebanon.

On 5 July 1920, Faisal dispatched his advisor Nuri al-Said

Nuri Pasha al-Said CH (December 1888 – 15 July 1958) ( ar, نوري السعيد) was an Iraqi politician during the British mandate in Iraq and the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq. He held various key cabinet positions and served eight terms as ...

to meet with the French General, Henri Gouraud, in Beirut. Nuri al-Said returned to Damascus on 14 July 1920 with a document known as the Gouraud ultimatum and Faisal was given four days to accept it. The ultimatum included five points:

# Acceptance of the French Mandate.

# Adoption of paper money issued by the Bank of Syria and Lebanon in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

.

# Approval of the French occupation of railway stations in Riyaq

Rayaq - Haouch Hala ( ar, رياق), also romanization of Arabic, romanized Rayak, is a Lebanon, Lebanese town in the Beqaa Governorate, Beqaa Mohafazat, Governorate near the city of Zahlé. In the early 20th century and up to 1975 and the outbrea ...

, Homs, Aleppo and Hama.

# Dissolution of the Syrian Army plus the cessation of forced recruitment and attempts to arm.

# Punish of those involved in hostilities against France.

King Faisal gathered his ministers to discuss the matter, and many of them agreed with Gouraud's terms and accepted the ultimatum. However, the position of the Minister of Defence, Yusuf al-Azma, was strongly opposed to accepting the ultimatum, and tried, by all means, to discourage King Faisal from responding to the French threat to dissolve the Syrian Army.

The Syrian government's acceptance of General Gouraud's ultimatum and abandoning the idea of resistance, and demobilizing of the Syrian Army and withdrawing soldiers from the village of Majdal Anjar

Majdal Anjar ( ar, مجدل عنجر; also transliterated Majdel Anjar) is a village of Beqaa Governorate, Lebanon. Majdal Anjar is an overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim town.

History

In 1838, Eli Smith noted ''Mejdel 'Anjar '' as a Sunni Muslim vi ...

was seen to be in violation of the decision of the Syrian National Congress. The general opinion of the people was voiced by loud demonstrations condemning the ultimatum, those who accepted it, and sending King Faisal a letter to Gouraud to accept the terms and dissolve the army.

The French Armed Forces began to march led by General Goabiah (by order of General Gouraud) towards Damascus on 24 July 1920, while the Syrian Army stationed on the border was retreating and dissolving, and when General Gouraud was asked about this, replied that Faisal's letter for approving the ultimatum terms reached him after the deadline.

There was only one choice and that was resistance until death, and this opinion was headed by Minister of Defence, Yusuf al-Azma, who worked to bring together the rest of the army with hundreds of volunteers who chose this resolution and headed to resist the invading French forces that marching towards Damascus.

Yusuf al-Azma wanted to preserve the prestige and dignity of Syria's military history, was afraid to record in the history books that the Syrian Army stayed away from fighting and that the military occupation of his capital had happened without resistance. He also wanted to inform the Syrian people that their army carried the banner of resistance against the French occupation from the first moment, and that they would be a beacon for them in their resistance against the military occupation.

General Goabiah's forces consisted of the following:

# an infantry brigade (415)

# 2nd Regiment of Algerian

Yusuf al-Azma wanted to preserve the prestige and dignity of Syria's military history, was afraid to record in the history books that the Syrian Army stayed away from fighting and that the military occupation of his capital had happened without resistance. He also wanted to inform the Syrian people that their army carried the banner of resistance against the French occupation from the first moment, and that they would be a beacon for them in their resistance against the military occupation.

General Goabiah's forces consisted of the following:

# an infantry brigade (415)

# 2nd Regiment of Algerian Tirailleur

A tirailleur (), in the Napoleonic era, was a type of light infantry trained to skirmish ahead of the main columns. Later, the term "''tirailleur''" was used by the French Army as a designation for indigenous infantry recruited in the French ...

s

# a brigade of Senegalese Tirailleurs

The Senegalese Tirailleurs (french: Tirailleurs Sénégalais) were a corps of colonial infantry in the French Army. They were initially recruited from Senegal,

French West Africa and subsequently throughout Western, Central and Eastern Africa: t ...

# Moroccan Spahi

Spahis () were light-cavalry regiments of the French army recruited primarily from the indigenous populations of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. The modern French Army retains one regiment of Spahis as an armoured unit, with personnel now ...

s Regiment

The French forces totalled nine thousand soldiers, supported by many aircraft, tanks and machine guns, while the Syrian Army did not exceeded 3,000 soldiers most of them volunteers.

On 24 July 1920, the Battle of Maysalun

The Battle of Maysalun ( ar, معركة ميسلون), also called the Battle of Maysalun Pass or the Battle of Khan Maysalun (french: Bataille de Khan Mayssaloun), was a four-hour battle fought between the forces of the Arab Kingdom of Syria an ...

began, when the French artillery began to overcome the Syrian artillery, French tanks began advancing towards the front line of the defending forces, and then French Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

ese soldiers began attacking the left side of the Syrian Army, which was composed mainly of volunteers, and some traitors attacked the Syrian Army from behind and killed many soldiers and robbed their weapons. Despite all, Yusuf al-Azma was unconcerned and remained steadfast and determined.

Yusuf al-Azma had planted land mines on the heads of the valley of Alqarn, a corridor used by the French Army, in the hope that when the tanks attack into, the land mines explode. However, the traitors had already cut off the mines wires, and some of them were caught during the operation, but it was too late. When the tanks approached, Yusuf al-Azma gave the order to detonate the land mines but they did not explode. He examined them and saw that most of them had been disabled. Then he heard an uproar from behind and when he turned, saw many of his armies and volunteers had fled after a bomb fell from one of the aircraft. So he grabbed his rifle and fired at the enemy until he was killed on Wednesday, 24 July 1920.

Policy of the French Mandate in Syria

State of Damascus

The State of Damascus (french: État de Damas; ar, دولة دمشق ') was one of the six states established by the French General Henri Gouraud in the French Mandate of Syria which followed the San Remo conference of 1920 and the defeat of K ...

(1920).

* State of Aleppo

The State of Aleppo (french: État d'Alep; ar, دولة حلب ') was one of the five states that were established by the French High Commissioner of the Levant, General Henri Gouraud, in the French Mandate of Syria which followed the San Remo ...

(1920).

* Alawite State

The Alawite State ( ar, دولة جبل العلويين, '; french: État des Alaouites), officially named the Territory of the Alawites (french: territoire des Alaouites), after the locally-dominant Alawites from its inception until its int ...

(1920).

* The State of Greater Lebanon (1920).

* Jabal Druze State

Jabal al-Druze ( ar, جبل الدروز, french: Djebel Druze) was an autonomous state in the French Mandate of Syria from 1921 to 1936, designed to function as a government for the local Druze population under French oversight.

Nomenclat ...

(1921).

* Sanjak of Alexandretta

The Sanjak of Alexandretta ( ar, لواء الإسكندرونة '', '' tr, İskenderun Sancağı, french: Sandjak d'Alexandrette) was a sanjak of the Mandate of Syria composed of two qadaas of the former Aleppo Vilayet ( Alexandretta and Antio ...

(1921).

The northern Syrian territory was given to Turkey during the Treaty of Ankara on 20 October 1921, and the boundary of the border between the colonial power and Turkey.

To tear the national unity of the country and weaken national resistance to the French mandate, General Gouraud resorted to the policy pursued by General Hubert Lyautey

Louis Hubert Gonzalve Lyautey (17 November 1854 – 27 July 1934) was a French Army general and colonial administrator. After serving in Indochina and Madagascar, he became the first French Resident-General in Morocco from 1912 to 1925. Early in ...

in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

. It is a policy of isolating cohesive religious and ethnic minorities from the mainstream in the country, under the pretext of defending their rights and equity, and incite the rural and Bedouin against urban.

The causes of the revolution

The outbreak of the revolution had many reasons, the most important of which are:

* The Syrians rejected the French occupation of their country, and sought full independence.

* Tearing Syria into several small states (Aleppo, Druze, Alawites, Damascus).

* The great economic damage caused to the Syrian merchants as a result of the policy adopted by the French in Syria, where the French dominated the economic aspects and linked the Syrian and

The outbreak of the revolution had many reasons, the most important of which are:

* The Syrians rejected the French occupation of their country, and sought full independence.

* Tearing Syria into several small states (Aleppo, Druze, Alawites, Damascus).

* The great economic damage caused to the Syrian merchants as a result of the policy adopted by the French in Syria, where the French dominated the economic aspects and linked the Syrian and Lebanese pound

The pound or lira ( ar, ليرة لبنانية ''līra Libnāniyya''; French: ''livre libanaise''; abbreviation: LL in Latin, in Arabic, historically also £L, ISO code: LBP) is the currency of Lebanon. It was formerly divided into 100 pias ...

s to the French franc

The franc (, ; sign: F or Fr), also commonly distinguished as the (FF), was a currency of France. Between 1360 and 1641, it was the name of coins worth 1 livre tournois and it remained in common parlance as a term for this amount of money. It w ...

.

* The military dictatorship practiced by the French generals during their mandate. Fighting the Arab culture of the country and trying to replace it with the French culture and appointing the French to top positions.

* The abolition of freedoms in Syria and the pursuit of nationalists and provoke sectarianism, which led to the discontent of the Syrians. The meeting between the leaders of the Jabal Druze State and the French high commissioner in Syria failed, where the Druze leaders expressed their displeasure with the policy of French General, Gabriel Carbillet, and demanded that another governor replace him. However, the high commissioner insulted them and threatened them with harsh punishment if they stuck to their position. As a result, Sultan al-Atrash declared that a revolution was necessary to achieve independence.

In the opinion of Dr. Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar

Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar ( ar, عبد الرحمن الشهبندر; ALA-LC: ''‘Abd al-Raḥman al-Shahbandar''; November 1879 – July 1940) was a prominent Syrian nationalist during the French Mandate of Syria and a leading opponent of comp ...

, the above reasons are the distant causes of the revolution. The primary reasons are General Carbillet's antagonism to the Al-Atrash

The al-Atrash ( ar, الأطرش ), also known as Bani al-Atrash, is a Druze clan based in Jabal Hauran in southwestern Syria. The family's name ''al-atrash'' is Arabic for "the deaf" and derives from one the family's deaf patriarchs. The a ...

family and attempts to crush their influence and jailed everyone who dealt with them, prompting Sultan al-Atrash to declare a revolution.

The demands of the revolution

The most prominent demands of the revolution: # Unity of the Syrian country with its coast and inside, and the recognition of one Syrian Arab fully independent state # The establishment of a popular government that gathers Syrian National Congress to draw up a fundamental law on the principle of absolute sovereignty of the nation # Withdrawal of the occupying forces from Syria and the formation of a national army to maintain security # Upholding the principles of theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

and human rights in freedom, equality and fraternity.

The course and events of the revolution

Colonel Catro, who was dispatched by General Gouraud to Jabal al-Druze, sought to isolate the Druze from the Syrian national movement, he signed on 4 March 1921 a treaty with the Druze tribes, which stipulated that Jabal al-Druze would form a particular administrative unit independent of the State of Damascus with a local governor and an elected representative council. In exchange for the Druze's recognition of the French mandate, the result of the treaty appointed Salim al-Atrash as the first ruler of the Jabal Druze State.

The Jabal Druze inhabitants were not comfortable with the new French administration and the first clash with it occurred in July 1922 with the arrest of

Colonel Catro, who was dispatched by General Gouraud to Jabal al-Druze, sought to isolate the Druze from the Syrian national movement, he signed on 4 March 1921 a treaty with the Druze tribes, which stipulated that Jabal al-Druze would form a particular administrative unit independent of the State of Damascus with a local governor and an elected representative council. In exchange for the Druze's recognition of the French mandate, the result of the treaty appointed Salim al-Atrash as the first ruler of the Jabal Druze State.

The Jabal Druze inhabitants were not comfortable with the new French administration and the first clash with it occurred in July 1922 with the arrest of Adham Khanjar

Adham Khanjar ( ar, أدهم خنجر) (1890–1922) was a Lebanese Shia Muslim revolutionary and Syrian nationalist who participated in guerilla warfare against the forces of the French occupation of Lebanon and Syria, and the attempt to assassi ...

, who was coming to Sultan al-Atrash carrying a letter to him. The French arrested him for his involvement in the attack on General Gouraud in Hauran, Sultan al-Atrash asked the French commander in As-Suwayda

As-Suwayda ( ar, ٱلسُّوَيْدَاء / ALA-LC romanization: ''as-Suwaydāʾ''), also spelled ''Sweida'' or ''Swaida'', is a mainly Druze city located in southwestern Syria, close to the border with Jordan.

It is the capital of As-Suwayda ...

to hand him over Adham Khanjar and he replied him that Khanjar was on his way to Damascus. So Sultan al-Atrash commissioned a group of his supporters to attack the armed convoy accompanying the detainee, but the French managed to transfer him to Lebanon and on 30 May 1923, executed him in Beirut.

The French destroyed the house of Sultan al-Atrash in Al-Qurayya

Al-Qurayya ( ar, القريا; also spelled al-Qrayya or Kureiyeh) is a town in southern Syria, administratively part of the al-Suwayda Governorate, located south of al-Suwayda. Nearby localities include Bosra to the southwest, Hout to the south ...

in late August 1922 in response to his attack on their forces, then Sultan al-Atrash led the Druze rebels for a year in a guerrilla war against the French forces. France brought a large force to crush the rebels, that forced Sultan al-Atrash to seek refuge in Transjordan in the late summer of 1922. Under British pressure, Sultan al-Atrash gave himself up to the French in April 1923 after agreeing to a truce.

Salim Al-Atrash died poisoned in Damascus in 1924; the French appointed captain Carbillet as governor of the Jabal Druze State, contrary to the agreement with the Druze, Where he abused the people and exposed them to forced labour and persecution nad sent them to prison. He also worked on the implementation of a policy of divide and conquer by inciting farmers against their feudal lords, especially the Al-Atrash family. This led the people of As-Suwayda to go out in a mass protest against the practices of the French authorities, which accelerated the outbreak of the revolution.

The Druze were fed up with the practices of captain Carbillet, which led them to send a delegation to Beirut on 6 June 1925 to submit a document requesting the

Salim Al-Atrash died poisoned in Damascus in 1924; the French appointed captain Carbillet as governor of the Jabal Druze State, contrary to the agreement with the Druze, Where he abused the people and exposed them to forced labour and persecution nad sent them to prison. He also worked on the implementation of a policy of divide and conquer by inciting farmers against their feudal lords, especially the Al-Atrash family. This led the people of As-Suwayda to go out in a mass protest against the practices of the French authorities, which accelerated the outbreak of the revolution.

The Druze were fed up with the practices of captain Carbillet, which led them to send a delegation to Beirut on 6 June 1925 to submit a document requesting the High Commissioner of the Levant The High Commissioner of France in the Levant (french: haut-commissaire de France au Levant; ar, المندوب السامي الفرنسي على سورية ولبنان), named after 1941 the General Delegate of Free France in the Levant (french: ...

, Maurice Sarrail

Maurice Paul Emmanuel Sarrail (6 April 1856 – 23 March 1929) was a French general of the First World War. Sarrail's openly socialist political connections made him a rarity amongst the Catholics, conservatives and monarchists who dominated th ...

, to appoint a Druze governor of the Jabal Druze instead of captain Carbillet because of his practices against the people of the Jabal Druze State. Some of these practices, according to memoirs of Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar, are:

# Allocate several gendarmes

Wrong info! -->