Great Reform Bill on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

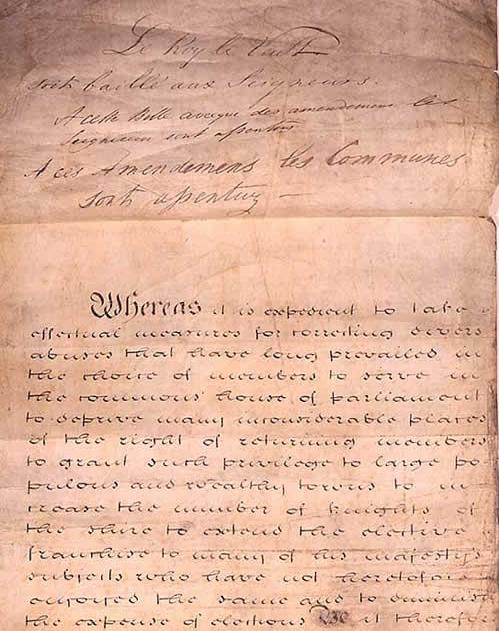

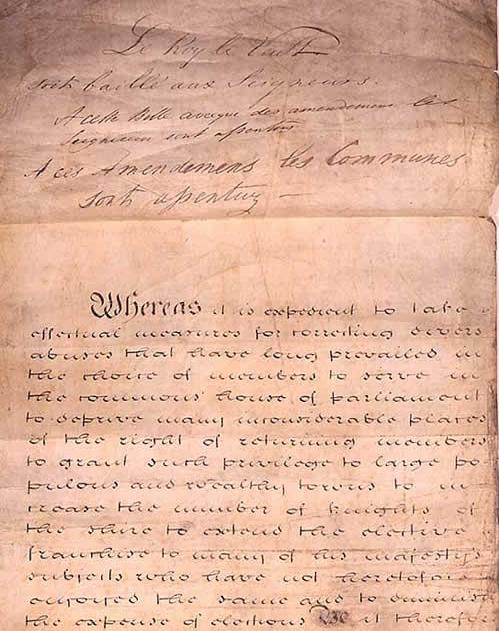

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of

After the

After the

Many constituencies, especially those with small electorates, were under the control of rich landowners, and were known as nomination boroughs or pocket boroughs, because they were said to be in the pockets of their patrons. Most patrons were noblemen or landed gentry who could use their local influence, prestige, and wealth to sway the voters. This was particularly true in rural counties, and in small boroughs situated near a large landed estate. Some noblemen even controlled multiple constituencies: for example, the

Many constituencies, especially those with small electorates, were under the control of rich landowners, and were known as nomination boroughs or pocket boroughs, because they were said to be in the pockets of their patrons. Most patrons were noblemen or landed gentry who could use their local influence, prestige, and wealth to sway the voters. This was particularly true in rural counties, and in small boroughs situated near a large landed estate. Some noblemen even controlled multiple constituencies: for example, the

During the 1640s, England endured a

During the 1640s, England endured a

The death of King George IV on 26 June 1830 dissolved Parliament by law, and a general election was held. Electoral reform, which had been frequently discussed during the preceding parliamentary session, became a major campaign issue. Across the country, several pro-reform "political unions" were formed, made up of both middle and working class individuals. The most influential of these was the Birmingham Political Union, led by Thomas Attwood. These groups confined themselves to lawful means of supporting reform, such as petitioning and public oratory, and achieved a high level of public support.

The Tories won a majority in the election, but the party remained divided, and support for the Prime Minister (

The death of King George IV on 26 June 1830 dissolved Parliament by law, and a general election was held. Electoral reform, which had been frequently discussed during the preceding parliamentary session, became a major campaign issue. Across the country, several pro-reform "political unions" were formed, made up of both middle and working class individuals. The most influential of these was the Birmingham Political Union, led by Thomas Attwood. These groups confined themselves to lawful means of supporting reform, such as petitioning and public oratory, and achieved a high level of public support.

The Tories won a majority in the election, but the party remained divided, and support for the Prime Minister (

After the Reform Bill was rejected in the Lords, the House of Commons immediately passed a motion of confidence affirming their support for Lord Grey's administration. Because parliamentary rules prohibited the introduction of the same bill twice during the same session, the ministry advised the new king,

After the Reform Bill was rejected in the Lords, the House of Commons immediately passed a motion of confidence affirming their support for Lord Grey's administration. Because parliamentary rules prohibited the introduction of the same bill twice during the same session, the ministry advised the new king,

The Reform Act's chief objective was the reduction of the number of nomination boroughs. There were 203 boroughs in England before the Act. The 56 smallest of these, as measured by their housing stock and tax assessments, were completely abolished. The next 30 smallest boroughs each lost one of their two MPs. In addition Weymouth and Melcombe Regis's four members were reduced to two. Thus in total the Act abolished 143 borough seats in England (one of the boroughs to be completely abolished,

The Reform Act's chief objective was the reduction of the number of nomination boroughs. There were 203 boroughs in England before the Act. The 56 smallest of these, as measured by their housing stock and tax assessments, were completely abolished. The next 30 smallest boroughs each lost one of their two MPs. In addition Weymouth and Melcombe Regis's four members were reduced to two. Thus in total the Act abolished 143 borough seats in England (one of the boroughs to be completely abolished,

online

* Brock, Michael. (1973). ''The Great Reform Act.'' London: Hutchinson Press

online

* Butler, J. R. M. (1914). ''The Passing of the Great Reform Bill.'' London: Longmans, Green, and Co. * Cannon, John. (1973). ''Parliamentary Reform 1640–1832.'' New York: Cambridge University Press. * Christie, Ian R. (1962). ''Wilkes, Wyvill and Reform: The Parliamentary Reform Movement in British Politics, 1760–1785.'' New York: St. Martin's Press. * Conacher, J.B. (1971)''The emergence of British parliamentary democracy in the nineteenth century: the passing of the Reform Acts of 1832, 1867, and 1884–1885'' (1971). * * Ertman, Thomas. "The Great Reform Act of 1832 and British Democratization." ''Comparative Political Studies'' 43.8–9 (2010): 1000–1022

online

* Evans, Eric J. (1983). ''The Great Reform Act of 1832.'' London: Methuen and Co. * Foot, Paul (2005). ''The Vote: How It Was Won and How It Was Undermined.'' London: Viking. * Fraser, Antonia (2013). ''Perilous question: the drama of the Great Reform Bill 1832'' London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. * Maehl, William H., Jr., ed. ''The Reform Bill of 1832: Why Not Revolution?'' (1967) 122pp; brief excerpts from primary and secondary sources * Mandler, Peter. (1990). ''Aristocratic Government in the Age of Reform: Whigs and Liberals, 1830–1852.'' Oxford: Clarendon Press. * Morrison, Bruce. (2011)

Channeling the “Restless Spirit of Innovation”: Elite Concessions and Institutional Change in the British Reform Act of 1832.

''World Politics'' 63.04 (2011): 678–710. * Newbould, Ian. (1990). ''Whiggery and Reform, 1830–1841: The Politics of Government.'' London: Macmillan. * O'Gorman, Frank. (1989). ''Voters, Patrons, and Parties: The Unreformed Electoral System of Hanoverian England, 1734–1832.'' Oxford: Clarendon Press. * Phillips, John A., and Charles Wetherell. (1995) "The Great Reform Act of 1832 and the political modernization of England." ''American historical review'' 100.2 (1995): 411–436

in JSTOR

* Phillips, John A. (1982). ''Electoral Behaviour in Unreformed England: Plumpers, Splitters, and Straights.'' Princeton:

excerpt and text search

* Veitch, George Stead. (1913). ''The Genesis of Parliamentary Reform.'' London: Constable and Co. * Warham, Dror. (1995). ''Imagining the Middle Class: The Political Representation of Class in Britain, c. 1780–1840.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Whitfield, Bob. ''The Extension of the Franchise: 1832–1931'' (Heinemann Advanced History, 2001), textbook * Wicks, Elizabeth (2006). ''The Evolution of a Constitution: Eight Key Moments in British Constitutional History.'' Oxford: Hart Pub., pp. 65–82. * Woodward, Sir E. Llewellyn. (1962). ''The Age of Reform, 1815–1870.'' Oxford: Clarendon Press.

* BBC Radio 4, In Our Time

The Great Reform Act

'' hosted by Melvin Bragg, 27 November 2008

Image of the original act on the Parliamentary Archives website

{{authority control United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1832 1832 in law Representation of the People Acts 1832 in politics Election law in the United Kingdom June 1832 events Electoral reform in the United Kingdom

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

(indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electoral system

An electoral system or voting system is a set of rules that determine how elections and referendums are conducted and how their results are determined. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections ma ...

of England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

. It abolished tiny districts, gave representation to cities, gave the vote to small landowners, tenant farmers, shopkeepers, householders who paid a yearly rental of £10 or more, and some lodgers. Only qualifying men were able to vote; the Act introduced the first explicit statutory bar to women voting by defining a voter as a male person.

It was designed to correct abuses – to "take effectual Measures for correcting divers Abuses that have long prevailed in the Choice of Members to serve in the Commons House of Parliament". Before the reform, most members nominally represented borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle A ...

s. The number of electors in a borough varied widely, from a dozen or so up to 12,000. Frequently the selection of Members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MPs) was effectively controlled by one powerful patron: for example Charles Howard, 11th Duke of Norfolk

Charles Howard, 11th Duke of Norfolk (15 March 1746 – 16 December 1815), styled Earl of Surrey from 1777 to 1786, was a British nobleman, peer, and politician. He was the son of Charles Howard, 10th Duke of Norfolk and Catherine Brockho ...

, controlled eleven boroughs. Criteria for qualification for the franchise varied greatly among boroughs, from the requirement to own land, to merely living in a house with a hearth sufficient to boil a pot.

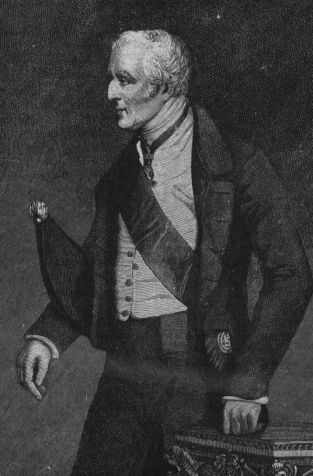

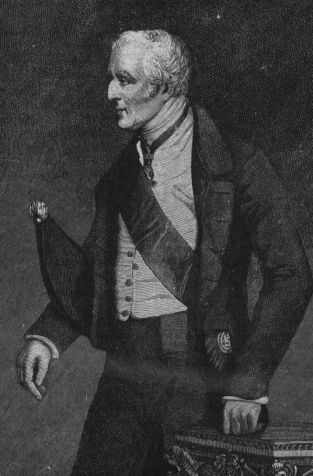

There had been calls for reform long before 1832, but without success. The Act that finally succeeded was proposed by the Whigs, led by Prime Minister Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey (13 March 1764 – 17 July 1845), known as Viscount Howick between 1806 and 1807, was a British Whig politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1830 to 1834. He was a member of the no ...

. It met with significant opposition from the Pittite factions in Parliament, who had long governed the country; opposition was especially pronounced in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

. Nevertheless, the bill was eventually passed, mainly as a result of public pressure. The Act granted seats in the House of Commons to large cities that had sprung up during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, and removed seats from the "rotten borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorate ...

s": those with very small electorates and usually dominated by a wealthy patron. The Act also increased the electorate from about 400,000 to 650,000, making about one in five adult males eligible to vote.

The full title is ''An Act to amend the representation of the people in England and Wales''. Its formal short title

In certain jurisdictions, including the United Kingdom and other Westminster-influenced jurisdictions (such as Canada or Australia), as well as the United States and the Philippines, primary legislation has both a short title and a long title.

T ...

and citation is "Representation of the People Act 1832 (2 & 3 Wm. IV, c. 45)". The Act applied only in England and Wales; the Irish Reform Act 1832 brought similar changes to Ireland. The separate Scottish Reform Act 1832 was revolutionary, enlarging the electorate by a factor of 13 from 5,000 to 65,000.

Unreformed House of Commons

Composition

After the

After the Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 (sometimes incorrectly referred to as a single 'Act of Union 1801') were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ir ...

became law on 1 January 1801, the unreformed House of Commons was composed of 658 members, of whom 513 represented England and Wales. There were two types of constituencies: counties and boroughs. County members were supposed to represent landholders, while borough members were supposed to represent the mercantile and trading interests of the kingdom.

Counties

Counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

were historical national subdivisions established between the 8th and 16th centuries. They were not merely parliamentary constituencies: many components of government (including court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in acco ...

s and the militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

) were organised along county lines. The members of Parliament chosen by the counties were known as knights of the shire

Knight of the shire ( la, milites comitatus) was the formal title for a member of parliament (MP) representing a county constituency in the British House of Commons, from its origins in the medieval Parliament of England until the Redistribution ...

. In Wales each county elected one member, while in England each county elected two members until 1826, when Yorkshire's representation was increased to four, following the disenfranchisement of the Cornish borough of Grampound

Grampound ( kw, Ponsmeur) is a village in Cornwall, England. It is at an ancient crossing point of the River Fal and today is on the A390 road west of St Austell and east of Truro.Ordnance Survey: Landranger map sheet 204 ''Truro & Falmouth'' ...

.

Boroughs

Parliamentary boroughs in England ranged widely in size from small hamlets to large cities, partly because they had evolved haphazardly. The earliest boroughs were chosen in the Middle Ages by county sheriffs, and even a village might be deemed a borough. Many of these early boroughs (such asWinchelsea

Winchelsea () is a small town in the non-metropolitan county of East Sussex, within the historic county of Sussex, England, located between the High Weald and the Romney Marsh, approximately south west of Rye and north east of Hastings. The ...

and Dunwich

Dunwich is a village and civil parish in Suffolk, England. It is in the Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB around north-east of London, south of Southwold and north of Leiston, on the North Sea coast.

In the Anglo-Saxon period, Dunwich was ...

) were substantial settlements at the time of their original enfranchisement, but later went into decline, and by the early 19th century some only had a few electors, but still elected two MPs; they were often known as rotten boroughs. Of the 70 English boroughs that Tudor monarchs enfranchised, 31 were later disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

. Finally, the parliamentarians of the 17th century compounded the inconsistencies by re-enfranchising 15 boroughs whose representation had lapsed for centuries, seven of which were later disenfranchised by the Reform Act. After Newark was enfranchised in 1661, no additional boroughs were enfranchised, and, with the sole exception of Grampound's 1821 disenfranchisement, the system remained unchanged until the Reform Act of 1832. Most English boroughs elected two MPs; but five boroughs elected only one MP: Abingdon, Banbury

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshir ...

, Bewdley

Bewdley ( pronunciation) is a town and civil parish in the Wyre Forest District in Worcestershire, England on the banks of the River Severn. It is in the Severn Valley west of Kidderminster and southwest of Birmingham. It lies on the Riv ...

, Higham Ferrers

Higham Ferrers is a market town and civil parish in the Nene Valley in North Northamptonshire, England, close to the Cambridgeshire and Bedfordshire borders. It forms a single built-up area with Rushden to the south and has an estimated popula ...

and Monmouth. The City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

and the joint borough of Weymouth and Melcombe Regis each elected four members. The Welsh boroughs each returned a single member.

The franchise

Statutes passed in 1430 and 1432, during the reign of Henry VI, standardised property qualifications for county voters. Under these Acts, all owners of freehold property or land worth at least forty shillings in a particular county were entitled to vote in that county. This requirement, known as the forty shilling freehold, was never adjusted for inflation of land value; thus the amount of land one had to own in order to vote gradually diminished over time. The franchise was restricted to males by custom rather than statute; on rare occasions women had been able to vote in parliamentary elections as a result of property ownership. Nevertheless, the vast majority of people were not entitled to vote; the size of the English county electorate in 1831 has been estimated at only 200,000. Furthermore, the sizes of the individual county constituencies varied significantly. The smallest counties, Rutland andAnglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

, had fewer than 1,000 voters each, while the largest county, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

, had more than 20,000. Those who owned property in multiple constituencies could vote multiple times. Not only was this typically legal (since there was usually no need for a property owner to live in a constituency in order to vote there) it was also feasible, even with the technology of the time, since polling was usually held over several days and rarely if ever did different constituencies vote on the same day.

In boroughs the franchise was far more varied. There were broadly six types of parliamentary boroughs, as defined by their franchise:

# Boroughs in which freemen were electors;

# Boroughs in which the franchise was restricted to those paying scot and lot

Scot and lot is a phrase common in the records of English, Welsh and Irish medieval boroughs, referring to local rights and obligations.

The term ''scot'' comes from the Old English word ''sceat'', an ordinary coin in Anglo-Saxon times, equivalen ...

, a form of municipal taxation;

# Boroughs in which only the ownership of a burgage

Burgage is a medieval land term used in Great Britain and Ireland, well established by the 13th century.

A burgage was a town ("borough" or "burgh") rental property (to use modern terms), owned by a king or lord. The property ("burgage tenement ...

property qualified a person to vote;

# Boroughs in which only members of the corporation were electors (such boroughs were perhaps in every case " pocket boroughs", because council members were usually "in the pocket" of a wealthy patron);

# Boroughs in which male householders were electors (these were usually known as " potwalloper boroughs", as the usual definition of a householder was a person able to boil a pot on his/her own hearth);

# Boroughs in which freeholders of land had the right to vote.

Some boroughs had a combination of these varying types of franchise, and most had special rules and exceptions, so many boroughs had a form of franchise that was unique to themselves.

The largest borough, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, had about 12,000 voters, while many of the smallest, usually known as "rotten boroughs", had fewer than 100 each. The most famous rotten borough was Old Sarum

Old Sarum, in Wiltshire, South West England, is the now ruined and deserted site of the earliest settlement of Salisbury. Situated on a hill about north of modern Salisbury near the A345 road, the settlement appears in some of the earliest r ...

, which had 13 burgage plots that could be used to "manufacture" electors if necessary—usually around half a dozen was thought sufficient. Other examples were Dunwich

Dunwich is a village and civil parish in Suffolk, England. It is in the Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB around north-east of London, south of Southwold and north of Leiston, on the North Sea coast.

In the Anglo-Saxon period, Dunwich was ...

(32 voters), Camelford

Camelford ( kw, Reskammel) is a town and civil parish in north Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, situated in the River Camel valley northwest of Bodmin Moor. The town is approximately ten miles (16 km) north of Bodmin and is governed ...

(25), and Gatton (7).

By contrast, France in 1831 had a population of 32 million, about double the 16.5 million in England, Wales and Scotland. But there were only 165,000 French voters (0.52% of the French population), compared to 439,000 in Britain (2.66% of the British population). France adopted universal male suffrage in 1848.

Women's suffrage

The claim for the women's vote appears to have been first made byJeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

in 1817 when he published his ''Plan of Parliamentary Reform in the form of a Catechism'', and was taken up by William Thompson in 1825, when he published, with Anna Wheeler, ''An Appeal of One Half the Human Race, Women, Against the Pretensions of the Other Half, Men, to Retain Them in Political, and Thence in Civil and Domestic Slavery: In Reply to Mr. Mill's Celebrated Article on Government''. In the "celebrated article on Government", James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote ''The History of Brit ...

had stated:

The passing of the Act seven years later enfranchising "male persons" was, however, a more significant event; it has been argued that it was the inclusion of the word "male", thus providing the first explicit statutory bar to women voting, which provided a focus of attack and a source of resentment from which, in time, the women's suffrage movement grew.

Pocket boroughs, bribery

Many constituencies, especially those with small electorates, were under the control of rich landowners, and were known as nomination boroughs or pocket boroughs, because they were said to be in the pockets of their patrons. Most patrons were noblemen or landed gentry who could use their local influence, prestige, and wealth to sway the voters. This was particularly true in rural counties, and in small boroughs situated near a large landed estate. Some noblemen even controlled multiple constituencies: for example, the

Many constituencies, especially those with small electorates, were under the control of rich landowners, and were known as nomination boroughs or pocket boroughs, because they were said to be in the pockets of their patrons. Most patrons were noblemen or landed gentry who could use their local influence, prestige, and wealth to sway the voters. This was particularly true in rural counties, and in small boroughs situated near a large landed estate. Some noblemen even controlled multiple constituencies: for example, the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

controlled eleven, while the Earl of Lonsdale

Earl of Lonsdale is a title that has been created twice in British history, firstly in the Peerage of Great Britain in 1784 (becoming extinct in 1802), and then in the Peerage of the United Kingdom in 1807, both times for members of the Lowth ...

controlled nine. Writing in 1821, Sydney Smith

Sydney Smith (3 June 1771 – 22 February 1845) was an English wit, writer, and Anglican cleric.

Early life and education

Born in Woodford, Essex, England, Smith was the son of merchant Robert Smith (1739–1827) and Maria Olier (1750–1801) ...

proclaimed that "The country belongs to the Duke of Rutland, Lord Lonsdale, the Duke of Newcastle, and about twenty other holders of boroughs. They are our masters!" T. H. B. Oldfield claimed in his ''Representative History of Great Britain and Ireland'' that, out of the 514 members representing England and Wales, about 370 were selected by nearly 180 patrons. A member who represented a pocket borough was expected to vote as his patron ordered, or else lose his seat at the next election.

Voters in some constituencies resisted outright domination by powerful landlords, but were often open to corruption. Electors were bribed individually in some boroughs, and collectively in others. In 1771, for example, it was revealed that 81 voters in New Shoreham (who constituted a majority of the electorate) formed a corrupt organisation that called itself the "Christian Club", and regularly sold the borough to the highest bidder. Especially notorious for their corruption were the "nabob

A nabob is a conspicuously wealthy man deriving his fortune in the east, especially in India during the 18th century with the privately held East India Company.

Etymology

''Nabob'' is an Anglo-Indian term that came to English from Urdu, poss ...

s", or individuals who had amassed fortunes in the British colonies in Asia and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

. The nabobs, in some cases, even managed to wrest control of boroughs from the nobility and the gentry. Lord Chatham, Prime Minister of Great Britain during the 1760s, casting an eye on the fortunes made in India commented that "the importers of foreign gold have forced their way into Parliament, by such a torrent of corruption as no private hereditary fortune could resist".

Movement for reform

Early attempts at reform

During the 1640s, England endured a

During the 1640s, England endured a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

that pitted King Charles I and the Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

against the Parliamentarians. In 1647, different factions of the victorious parliamentary army held a series of discussions, the Putney Debates

The Putney Debates, which took place from 28 October to 8 November 1647, were a series of discussions over the political settlement that should follow Parliament's victory over Charles I in the First English Civil War. The main participants were ...

, on reforming the structure of English government. The most radical elements proposed universal manhood suffrage and the reorganisation of parliamentary constituencies. Their leader Thomas Rainsborough

Thomas Rainsborough, or Rainborowe, 6 July 1610 – 29 October 1648, was an English religious and political radical who served in the Parliamentarian navy and New Model Army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. One of the few contemporaries wh ...

declared, "I think it's clear, that every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government."

More conservative members disagreed, arguing instead that only individuals who owned land in the country should be allowed to vote. For example, Henry Ireton stated, "no man hath a right to an interest or share in the disposing of the affairs of the kingdom ... that hath not a permanent fixed interest in this kingdom." The views of the conservative "Grandees" eventually won out. Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

, who became the leader of England after the abolition of the monarchy in 1649, refused to adopt universal suffrage; individuals were required to own property (real or personal) worth at least £200 in order to vote. He did nonetheless agree to some electoral reform; he disfranchised several small boroughs, granted representation to large towns such as Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

and Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

, and increased the number of members elected by populous counties. These reforms were all reversed, however, after Cromwell's death and the last parliament to be elected in the Commonwealth period in 1659 reverted to the electoral system as it had existed under Charles I.

Following Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 the issue of parliamentary reform lay dormant; James II's attempt to remodel municipal corporations to gain control of their borough seats created an antipathy to any change after the Glorious Revolution. It was revived in the 1760s by the Whig Prime Minister William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

("Pitt the Elder"), who called borough representation "the rotten part of our Constitution" (hence the term "rotten borough"). Nevertheless, he did not advocate an immediate disfranchisement of rotten boroughs. He instead proposed that a third member be added to each county, to countervail the borough influence. The Whigs failed to unite behind the expansion of county representation; some objected to the idea because they felt that it would give too much power to the aristocracy and gentry in rural areas. Ultimately, despite Chatham's exertions, Parliament took no action on his proposals.

The cause of parliamentary reform was next taken up by Lord Chatham's son, William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

(variously described as a Tory and as an "independent Whig"). Like his father, he shrank from proposing the wholesale abolition of the rotten boroughs, advocating instead an increase in county representation. The House of Commons rejected Pitt's resolution by over 140 votes, despite receiving petitions for reform bearing over twenty thousand signatures. In 1783, Pitt became Prime Minister but was still unable to achieve reform. King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

was averse to the idea, as were many members of Pitt's own cabinet. In 1786, the Prime Minister proposed a reform bill, but the House of Commons rejected it on a 174–248 vote. Pitt did not raise the issue again for the remainder of his term.

Aftermath of the French Revolution

Support for parliamentary reform plummeted after the launch of theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

in 1789. Many English politicians became steadfastly opposed to any major political change. Despite this reaction, several Radical Movement

The Radical Movement (french: Mouvement radical, MR), officially the Radical, Social and Liberal Movement (french: link=no, Mouvement radical, social et libéral), was a Social liberalism, social-liberal list of political parties in France, politi ...

groups were established to agitate for reform. A group of Whigs led by James Maitland, 8th Earl of Lauderdale

James Maitland, 8th Earl of Lauderdale (26 January 1759 – 10 September 1839) was Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland and a representative peer for Scotland in the House of Lords.

Early years

Born at Haltoun House near Ratho, the eldest s ...

, and Charles Grey founded an organisation advocating parliamentary reform in 1792. This group, known as the Society of the Friends of the People

The Society of the Friends of the People was an organisation in Great Britain that was focused on advocating for Parliamentary Reform. It was founded by the Whig Party in 1792.

The Society in England was aristocratic and exclusive, in contrast ...

, included 28 MPs. In 1793, Grey presented to the House of Commons a petition from the Friends of the People, outlining abuses of the system and demanding change. He did not propose any specific scheme of reform, but merely a motion that the House inquire into possible improvements. Parliament's reaction to the French Revolution was so negative, that even this request for an inquiry was rejected by a margin of almost 200 votes. Grey tried to raise the subject again in 1797, but the House again rebuffed him by a majority of over 150.

Other notable pro-reform organisations included the Hampden Clubs (named after John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of t ...

, an English politician who opposed the Crown during the English Civil War) and the London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associati ...

(which consisted of workers and artisans). But the "Radical" reforms supported by these organisations (for example, universal suffrage) found even less support in Parliament. For example, when Sir Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartists) of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vo ...

, chairman of the London Hampden Club, proposed a resolution in favour of universal suffrage, equally sized electoral districts, and voting by secret ballot to the House of Commons, his motion found only one other supporter ( Lord Cochrane) in the entire House.

Despite such setbacks, popular pressure for reform remained strong. In 1819, a large pro-reform rally was held in Birmingham. Although the city was not entitled to any seats in the Commons, those gathered decided to elect Sir Charles Wolseley as Birmingham's "legislatorial representative". Following their example, reformers in Manchester held a similar meeting to elect a "legislatorial attorney". Between 20,000 and 60,000 (by different estimates) attended the event, many of them bearing signs such as "Equal Representation or Death". The protesters were ordered to disband; when they did not, the Manchester Yeomenry suppressed the meeting by force. Eighteen people were killed and several hundred injured, the event later to become known as the Peterloo Massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliament ...

. In response, the government passed the Six Acts

Following the Peterloo Massacre on 16 August 1819, the government of the United Kingdom acted to prevent any future disturbances by the introduction of new legislation, the so-called Six Acts aimed at suppressing any meetings for the purpose of ...

, measures designed to quell further political agitation. In particular, the Seditious Meetings Act prohibited groups of more than 50 people from assembling to discuss any political subject without prior permission from the sheriff or magistrate.

Reform during the 1820s

Since the House of Commons regularly rejected direct challenges to the system of representation by large majorities, supporters of reform had to content themselves with more modest measures. The WhigLord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

brought forward one such measure in 1820, proposing the disfranchisement of the notoriously corrupt borough of Grampound

Grampound ( kw, Ponsmeur) is a village in Cornwall, England. It is at an ancient crossing point of the River Fal and today is on the A390 road west of St Austell and east of Truro.Ordnance Survey: Landranger map sheet 204 ''Truro & Falmouth'' ...

in Cornwall. He suggested that the borough's two seats be transferred to the city of Leeds. Tories in the House of Lords agreed to the disfranchisement of the borough, but refused to accept the precedent of directly transferring its seats to an industrial city. Instead, they modified the proposal so that two further seats were given to Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

, the county in which Leeds is situated. In this form, the bill passed both houses and became law. In 1828, Lord John Russell suggested that Parliament repeat the idea by abolishing the corrupt boroughs of Penryn and East Retford

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

, and by transferring their seats to Manchester and Birmingham. This time, however, the House of Lords rejected his proposals. In 1830, Russell proposed another, similar scheme: the enfranchisement of Leeds, Manchester, and Birmingham, and the disfranchisement of the next three boroughs found guilty of corruption; again, the proposal was rejected.

Support for reform came from an unexpected source—a reactionary faction of the Tory Party—in 1829. The Tory government under Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish soldier and Tories (British political party), Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of Uni ...

, responding to the danger of civil strife in largely Roman Catholic Ireland, drew up the Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1829. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic emancipation throughout the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

. This legislation repealed various laws that imposed political disabilities on Roman Catholics, in particular laws that prevented them from becoming members of Parliament. In response, disenchanted ultra-Tories

The Ultra-Tories were an Anglican faction of British and Irish politics that appeared in the 1820s in opposition to Catholic emancipation. The faction was later called the "extreme right-wing" of British and Irish politics.James J. Sack"Ultra torie ...

who perceived a danger to the established religion came to favour parliamentary reform, in particular the enfranchisement of Manchester, Leeds, and other heavily Nonconformist cities in northern England.

Passage of the Reform Act

First Reform Bill

The death of King George IV on 26 June 1830 dissolved Parliament by law, and a general election was held. Electoral reform, which had been frequently discussed during the preceding parliamentary session, became a major campaign issue. Across the country, several pro-reform "political unions" were formed, made up of both middle and working class individuals. The most influential of these was the Birmingham Political Union, led by Thomas Attwood. These groups confined themselves to lawful means of supporting reform, such as petitioning and public oratory, and achieved a high level of public support.

The Tories won a majority in the election, but the party remained divided, and support for the Prime Minister (

The death of King George IV on 26 June 1830 dissolved Parliament by law, and a general election was held. Electoral reform, which had been frequently discussed during the preceding parliamentary session, became a major campaign issue. Across the country, several pro-reform "political unions" were formed, made up of both middle and working class individuals. The most influential of these was the Birmingham Political Union, led by Thomas Attwood. These groups confined themselves to lawful means of supporting reform, such as petitioning and public oratory, and achieved a high level of public support.

The Tories won a majority in the election, but the party remained divided, and support for the Prime Minister (the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister of ...

) was weak. When the Opposition raised the issue of reform in one of the first debates of the year, the Duke made a controversial defence of the existing system of government, recorded in the formal "third-party" language of the time:

He was fully convinced that the country possessed, at the present moment, a legislature which answered all the good purposes of legislation,—and this to a greater degree than any legislature ever had answered, in any country whatever. He would go further, and say that the legislature and system of representation possessed the full and entire confidence of the country. ..He would go still further, and say, that if at the present moment he had imposed upon him the duty of forming a legislature for any country ..he did not mean to assert that he could form such a legislature as they possessed now, for the nature of man was incapable of reaching such excellence at once. .. long as he held any station in the government of the country, he should always feel it his duty to resist eformmeasures, when proposed by others.The Prime Minister's absolutist views proved extremely unpopular, even within his own party. Less than two weeks after Wellington made these remarks, on 15 November 1830 he was forced to resign after he was defeated in a

motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or m ...

. Sydney Smith wrote, "Never was any administration so completely and so suddenly destroyed; and, I believe, entirely by the Duke's declaration, made, I suspect, in perfect ignorance of the state of public feeling and opinion." Wellington was replaced by the Whig reformer Charles Grey, who had by this time the title of Earl Grey.

Lord Grey's first announcement as Prime Minister was a pledge to carry out parliamentary reform. On 1 March 1831, Lord John Russell brought forward the Reform Bill in the House of Commons on the government's behalf. The bill disfranchised 60 of the smallest boroughs, and reduced the representation of 47 others. Some seats were completely abolished, while others were redistributed to the London suburbs, to large cities, to the counties, and to Scotland and Ireland. Furthermore, the bill standardised and expanded the borough franchise, increasing the size of the electorate (according to one estimate) by half a million voters.

On 22 March, the vote on the second reading

A reading of a bill is a stage of debate on the bill held by a general body of a legislature.

In the Westminster system, developed in the United Kingdom, there are generally three readings of a bill as it passes through the stages of becoming ...

attracted a record 608 members, including the non-voting Speaker (the previous record was 530 members). Despite the high attendance, the second reading was approved by only one vote, and further progress on the Reform Bill was difficult. During the committee stage, Isaac Gascoyne

Isaac Gascoyne (21 August 1763 – 26 August 1841) was a British Army officer and Tory politician. He was born at Barking, London Essex on 21 August 1763, the third son of Bamber Gascoyne (senior) and Mary Green and was educated at Felsted Sc ...

put forward a motion objecting to provisions of the bill that reduced the total number of seats in the House of Commons. This motion was carried, against the government's wishes, by 8 votes. Thereafter, the ministry lost a vote on a procedural motion by 22 votes. As these divisions indicated that Parliament was against the Reform Bill, the ministry decided to request a dissolution and take its appeal to the people.

Second Reform Bill

The political and popular pressure for reform had grown so great that pro-reform Whigs won an overwhelming House of Commons majority in the general election of 1831. The Whig party won almost all constituencies with genuine electorates, leaving the Tories with little more than the rotten boroughs. The Reform Bill was again brought before the House of Commons, which agreed to the second reading by a large majority in July. During the committee stage, opponents of the bill slowed its progress through tedious discussions of its details, but it was finally passed in September, by a margin of more than 100 votes. The Bill was then sent up to the House of Lords, a majority in which was known to be hostile to it. After the Whigs' decisive victory in the 1831 election, some speculated that opponents would abstain, rather than openly defy the public will. Indeed, when the Lords voted on the second reading of the bill after a memorable series of debates, many Tory peers did refrain from voting. However, the Lords Spiritual mustered in unusually large numbers, and of 22 present, 21 voted against the Bill. It failed by 41 votes. When the Lords rejected the Reform Bill, public violence ensued. That very evening, riots broke out inDerby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

, where a mob attacked the city jail and freed several prisoners. In Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

, rioters set fire to Nottingham Castle

Nottingham Castle is a Stuart Restoration-era ducal mansion in Nottingham, England, built on the site of a Norman castle built starting in 1068, and added to extensively through the medieval period, when it was an important royal fortress and ...

(the home of the Duke of Newcastle) and attacked Wollaton Hall

Wollaton Hall is an Elizabethan country house of the 1580s standing on a small but prominent hill in Wollaton Park, Nottingham, England. The house is now Nottingham Natural History Museum, with Nottingham Industrial Museum in the outbuilding ...

(the estate of Lord Middleton). The most significant disturbances occurred at Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, where rioters controlled the city for three days. The mob broke into prisons and destroyed several buildings, including the palace of the Bishop of Bristol

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

, the mansion of the Lord Mayor of Bristol, and several private homes. Other places that saw violence included Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

, Leicestershire, and Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

.

Meanwhile, the political unions, which had hitherto been separate groups united only by a common goal, decided to form the National Political Union. Perceiving this group as a threat, the government issued a proclamation pursuant to the Corresponding Societies Act 1799 declaring such an association "unconstitutional and illegal", and commanding all loyal subjects to shun it. The leaders of the National Political Union ignored this proclamation, but leaders of the influential Birmingham branch decided to co-operate with the government by discouraging activities on a national level.

Third Reform Bill

After the Reform Bill was rejected in the Lords, the House of Commons immediately passed a motion of confidence affirming their support for Lord Grey's administration. Because parliamentary rules prohibited the introduction of the same bill twice during the same session, the ministry advised the new king,

After the Reform Bill was rejected in the Lords, the House of Commons immediately passed a motion of confidence affirming their support for Lord Grey's administration. Because parliamentary rules prohibited the introduction of the same bill twice during the same session, the ministry advised the new king, William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

, to prorogue Parliament. As soon as the new session began in December 1831, the Third Reform Bill was brought forward. The bill was in a few respects different from its predecessors; it no longer proposed a reduction in the total membership of the House of Commons, and it reflected data collected during the census that had just been completed. The new version passed in the House of Commons by even larger majorities in March 1832; it was once again sent up to the House of Lords.

Realizing that another rejection would not be politically feasible, opponents of reform decided to use amendments to change the bill's essential character; for example, they voted to delay consideration of clauses in the bill that disfranchised the rotten boroughs. The ministers believed that they were left with only one alternative: to create a large number of new peerages, swamping the House of Lords with pro-reform votes. But the prerogative of creating peerages rested with the king, who recoiled from so drastic a step and rejected the unanimous advice of his cabinet. Lord Grey then resigned, and the king invited the Duke of Wellington to form a new government.

The ensuing period became known as the "Days of May

The Days of May was a period of significant social unrest and political tension in the United Kingdom in May 1832, after the Tories blocked the Third Reform Bill in the House of Lords, which aimed to extend parliamentary representation to the ...

", with so great a level of political agitation that some feared revolution. Some protesters advocated non-payment of taxes, and urged a run on the banks; one day signs appeared across London reading "Stop the Duke; go for gold!" £1.8 million was withdrawn from the Bank of England in the first days of the run (out of about £7 million total gold in the bank's possession). The National Political Union and other organisations sent petitions to the House of Commons, demanding that they withhold supply (cut off funding to the government) until the House of Lords should acquiesce. Some demonstrations called for the abolition of the nobility, and some even of the monarchy. In these circumstances, the Duke of Wellington had great difficulty in building support for his premiership, despite promising moderate reform. He was unable to form a government, leaving King William with no choice but to recall Lord Grey. Eventually the king consented to fill the House of Lords with Whigs; however, without the knowledge of his cabinet, Wellington circulated a letter among Tory peers, encouraging them to desist from further opposition, and warning them of the consequences of continuing. At this, enough opposing peers relented. By abstaining from further votes, they allowed the legislation to pass in the House of Lords, and the Crown was thus not forced to create new peers. The bill finally received royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in oth ...

on 7 June 1832, thereby becoming law.

Results

Provisions

Abolition of seats

The Reform Act's chief objective was the reduction of the number of nomination boroughs. There were 203 boroughs in England before the Act. The 56 smallest of these, as measured by their housing stock and tax assessments, were completely abolished. The next 30 smallest boroughs each lost one of their two MPs. In addition Weymouth and Melcombe Regis's four members were reduced to two. Thus in total the Act abolished 143 borough seats in England (one of the boroughs to be completely abolished,

The Reform Act's chief objective was the reduction of the number of nomination boroughs. There were 203 boroughs in England before the Act. The 56 smallest of these, as measured by their housing stock and tax assessments, were completely abolished. The next 30 smallest boroughs each lost one of their two MPs. In addition Weymouth and Melcombe Regis's four members were reduced to two. Thus in total the Act abolished 143 borough seats in England (one of the boroughs to be completely abolished, Higham Ferrers

Higham Ferrers is a market town and civil parish in the Nene Valley in North Northamptonshire, England, close to the Cambridgeshire and Bedfordshire borders. It forms a single built-up area with Rushden to the south and has an estimated popula ...

, returned only a single MP).

Creation of new seats

In their place the Act created 130 new seats in England and Wales: * 26 English counties were divided into two divisions with each division being represented by two members. * 8 English counties and 3 Welsh counties each received an additional representative. * Yorkshire, which was represented by four MPs before the Act, was given an extra two MPs (so that each of its three ridings was represented by two MPs). * 22 large towns were given two MPs. * Another 21 towns (of which two were in Wales) were given one MP. Thus 65 new county seats and 65 new borough seats were created in England and Wales. The total number of English members fell by 17 and the number in Wales increased by four. The boundaries of the new divisions and parliamentary boroughs were defined in a separate Act, theParliamentary Boundaries Act 1832

The Parliamentary Boundaries Act 1832 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which defined the parliamentary divisions (constituencies) in England and Wales required by the Reform Act 1832. The boundaries were largely those recommen ...

.

Extension of the franchise

The Act also extended the franchise. In county constituencies, in addition to forty-shilling freeholders, franchise rights were extended to owners of land in copyhold worth £10 and holders of long-term leases (more than sixty years) on land worth £10 and holders of medium-term leases (between twenty and sixty years) on land worth £50 and to tenants-at-will paying an annual rent of £50. In borough constituencies all male householders living in properties worth at least £10 a year were given the right to vote – a measure which introduced to all boroughs a standardised form of franchise for the first time. Existing borough electors retained a lifetime right to vote, however they had qualified, provided they were resident in the boroughs in which they were electors. In those boroughs which had freemen electors, voting rights were to be enjoyed by future freemen as well, provided their freemanship was acquired through birth or apprenticeship and they too were resident. The Act also introduced a system ofvoter registration

In electoral systems, voter registration (or enrollment) is the requirement that a person otherwise eligible to vote must register (or enroll) on an electoral roll, which is usually a prerequisite for being entitled or permitted to vote.

The r ...

, to be administered by the overseers of the poor in every parish and township. It instituted a system of special courts to review disputes relating to voter qualifications. It also authorised the use of multiple polling places within the same constituency, and limited the duration of polling to two days. (Formerly, polls could remain open for up to forty days.)

The Reform Act itself did not affect constituencies in Scotland or Ireland. However, there were also reforms there, under the Scottish Reform Act and the Irish Reform Act. Scotland received eight additional seats, and Ireland received five; thus keeping the total number of seats in the House of Commons the same as it had been before the Act. While no constituencies were disfranchised in either of those countries, voter qualifications were standardised and the size of the electorate was increased in both.

Effects

Between 1835 and 1841, local Conservative Associations began to educate citizens about the party's platform and encouraged them to register to vote annually, as required by the Act. Coverage of national politics in the local press was joined by in-depth reports on provincial politics in the national press. Grassroots Conservatives therefore saw themselves as part of a national political movement during the 1830s. The size of the pre-Reform electorate is difficult to estimate. Voter registration was lacking, and many boroughs were rarely contested in elections. It is estimated that immediately before the 1832 Reform Act, 400,000 English subjects (people who lived in the country) were entitled to vote, and that after passage, the number rose to 650,000, an increase of more than 60%. Rodney Mace estimates that before, 1 percent of the population could vote and that the Reform Act only extended the franchise to 7 percent of the population. Tradesmen, such as shoemakers, believed that the Reform Act had given them the vote. One example is the shoemakers of Duns, Scottish Borders,Berwickshire

Berwickshire ( gd, Siorrachd Bhearaig) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in south-eastern Scotland, on the English border. Berwickshire County Council existed from 1890 until 1975, when the area became part of t ...

. They created a banner celebrating the Reform Act which declared, "The battle's won. Britannia's sons are free." This banner is on display at People's History Museum

The People's History Museum (the National Museum of Labour History until 2001) in Manchester, England, is the UK's national centre for the collection, conservation, interpretation and study of material relating to the history of working people ...

in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

.

Many major commercial and industrial cities became separate parliamentary boroughs under the Act. The new constituencies saw party conflicts within the middle class, and between the middle class and working class. A study of elections in the medium-sized borough of Halifax, 1832–1852, concluded that the party organisations, and the voters themselves, depended heavily on local social relationships and local institutions. Having the vote encouraged many men to become much more active in the political, economic and social sphere.

The Scottish Act revolutionised politics in Scotland, with its population of 2 million. Its electorate had been only 0.2% of the population compared to 4% in England. The Scottish electorate overnight soared from 5,000 to 65,000, or 13% of the adult men, and was no longer a private preserve of a few very rich families.

Tenant voters

Most of the pocket boroughs abolished by the Reform Act belonged to the Tory party. These losses were somewhat offset by the extension of the vote to tenants-at-will paying an annual rent of £50. This clause, proposed by the Tory Marquess of Chandos, was adopted in the House of Commons despite opposition from the Government. The tenants-at-will thereby enfranchised typically voted as instructed by their landlords, who in turn normally supported the Tory party. This concession, together with the Whig party's internal divisions and the difficulties faced by the nation's economy, allowed the Tories underSir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

to make gains in the elections of 1835

Events

January–March

* January 7 – anchors off the Chonos Archipelago on her second voyage, with Charles Darwin on board as naturalist.

* January 8 – The United States public debt contracts to zero, for the only time in history. ...

and 1837

Events

January–March

* January 1 – The destructive Galilee earthquake causes 6,000–7,000 casualties in Ottoman Syria.

* January 26 – Michigan becomes the 26th state admitted to the United States.

* February – Charles Dick ...

, and to retake the House of Commons in 1841

Events

January–March

* January 20 – Charles Elliot of the United Kingdom, and Qishan of the Qing dynasty, agree to the Convention of Chuenpi.

* January 26 – Britain occupies Hong Kong. Later in the year, the first census of the i ...

.

A modern historian's examination of votes in the House concluded that the traditional landed interest "suffered very little" by the 1832 Act. They continued to dominate the Commons, while losing a bit of their power to enact laws that focused on their more parochial interests. By contrast, the same study concluded that the 1867 Reform Act

The Representation of the People Act 1867, 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102 (known as the Reform Act 1867 or the Second Reform Act) was a piece of British legislation that enfranchised part of the urban male working class in England and Wales for the first ...

caused serious erosion of their legislative power and the 1874 elections saw great landowners losing their county seats to the votes of tenant farmers in England and especially in Ireland.

Limitations

The Reform Act did not enfranchise the working class since voters were required to possess property worth £10, a substantial sum at the time. This split the alliance between the working class and the middle class. The failure of the 1832 Reform Act to extend the vote beyond those owning property led to the growth of theChartist Movement

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

.

Although it did disenfranchise most rotten borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorate ...

s, a few remained, such as Totnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-southwest of Torquay and abo ...

in Devon and Midhurst

Midhurst () is a market town, parish and civil parish in West Sussex, England. It lies on the River Rother inland from the English Channel, and north of the county town of Chichester.

The name Midhurst was first recorded in 1186 as ''Middeh ...

in Sussex. Also, bribery of voters remained a problem. As Sir Thomas Erskine May observed, "it was too soon evident, that as more votes had been created, more votes were to be sold".

The Reform Act strengthened the House of Commons by reducing the number of nomination boroughs controlled by peers. Some aristocrats complained that, in the future, the government could compel them to pass any bill, simply by threatening to swamp the House of Lords with new peerages. The Duke of Wellington lamented: "If such projects can be carried into execution by a minister of the Crown with impunity, there is no doubt that the constitution of this House, and of this country, is at an end. .. ere is absolutely an end put to the power and objects of deliberation in this House, and an end to all just and proper means of decision." The subsequent history of Parliament, however, shows that the influence of the Lords was largely undiminished. They compelled the Commons to accept significant amendments to the Municipal Reform Bill in 1835, forced compromises on Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It in ...

, and successfully resisted several other bills supported by the public. It would not be until decades later, culminating in the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parlia ...

, that Wellington's fears would come to pass.

Further reform

During the ensuing years, Parliament adopted several more minor reforms. Acts of Parliament passed in 1835 and 1836 increased the number of polling places in each constituency, therefore reduced polling to a single day. Parliament also passed several laws aimed at combatting corruption, including the Corrupt Practices Act 1854, though these measures proved largely ineffectual. Neither party strove for further major reform; leading statesmen on both sides regarded the Reform Act as a final settlement. There was considerable public agitation for further expansion of the electorate, however. In particular, theChartist movement

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

, which demanded universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

for men, equally sized electoral districts, and voting by secret ballot, gained a widespread following. But the Tories were united against further reform, and the Liberal Party (successor to the Whigs) did not seek a general revision of the electoral system until 1852. The 1850s saw Lord John Russell introduce a number of reform bills to correct defects the first act had left unaddressed. However, no proposal was successful until 1867, when Parliament adopted the Second Reform Act.

An area the Reform Act did not address was the issue of municipal and regional government. As a result of archaic traditions, many English counties had enclaves and exclaves, which were mostly abolished in the Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844

The Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844 (7 & 8 Vict. c. 61), which came into effect on 20 October 1844, was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom which eliminated many outliers or exclaves of counties in England and Wales for civil purposes. ...

. Furthermore, many new conurbations and economic areas bridged traditional county boundaries by having been formed in previously obscure areas: the West Midlands conurbation bridged Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire, Manchester and Liverpool both had hinterlands in Cheshire but city centres in Lancashire, while in the south Oxford's developing southern suburbs were in Berkshire and London was expanding into Essex, Surrey and Middlesex. This led to further acts to reorganise county boundaries in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Assessment

Many historians credit the Reform Act 1832 with launching modern democracy in Great Britain.G. M. Trevelyan

George Macaulay Trevelyan (16 February 1876 – 21 July 1962) was a British historian and academic. He was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1903. He then spent more than twenty years as a full-time author. He returned to the ...

hails 1832 as the watershed moment at which the sovereignty of the people' had been established in fact, if not in law". Sir Erskine May notes that the "reformed Parliament was, unquestionably, more liberal and progressive in its policy than the Parliaments of old; more vigorous and active; more susceptible to the influence of public opinion; and more secure in the confidence of the people", but admitted that "grave defects still remained to be considered". Other historians have argued that genuine democracy began to arise only with the Second Reform Act in 1867, or perhaps even later. Norman Gash

Norman Gash (16 January 1912 in Meerut, British Raj – 1 May 2009 in Somerset) was a British historian, best remembered for a two-volume biography of British prime minister Sir Robert Peel. He was professor of modern history at the University ...

states that "it would be wrong to assume that the political scene in the succeeding generation differed essentially from that of the preceding one".

Much of the support for passage in Parliament came from conservatives hoping to head off even more radical changes. Earl Grey argued that the aristocracy would best be served by a cautiously constructive reform program. Most Tories were strongly opposed, and made dire predictions about what they saw as dangerous, radical proposals. However one faction of Ultra-Tories

The Ultra-Tories were an Anglican faction of British and Irish politics that appeared in the 1820s in opposition to Catholic emancipation. The faction was later called the "extreme right-wing" of British and Irish politics.James J. Sack"Ultra torie ...

supported reform measures in order to weaken Wellington's ministry, which had outraged them by granting Catholic emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

.

Historians in recent decades have been polarized over emphasizing or downplaying the importance of the Act. However, John A. Phillips, and Charles Wetherell argue for its drastic modernizing impact on the political system:

:England's frenzy over the Reform Bill in 1831, coupled with the effect of the bill itself upon its enactment in 1832, unleashed a wave of political modernization that the Whig Party eagerly harnessed and the Tory Party grudgingly, but no less effectively, embraced. Reform quickly destroyed the political system that had prevailed during the long reign of George III and replaced it with an essentially modern electoral system based on rigid partisanship and clearly articulated political principle. Hardly "modest" in its consequences, the Reform Act could scarcely have caused a more drastic alteration in England's political fabric.

Likewise Eric Evans concludes that the Reform Act "opened a door on a new political world". Although Grey's intentions were conservative, Evans says, and the 1832 Act gave the aristocracy an additional half-century's control of Parliament, the Act nevertheless did open constitutional questions for further development. Evans argues it was the 1832 Act, not the later reforms of 1867, 1884, or 1918, that were decisive in bringing representative democracy to Britain. Evans concludes the Reform Act marked the true beginning of the development of a recognisably modern political system.Eric J. Evans, ''The Forging of the Modern State: Early Industrial Britain, 1783–1870'' (2nd ed. 1996) p. 229

See also

* 1832 United Kingdom general election * Elections in the United Kingdom § History * List of Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, 1820–39 * List of constituencies enfranchised and disfranchised by the Reform Act 1832 *Reapportionment Act of 1929

The Reapportionment Act of 1929 (ch. 28, , ), also known as the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929, is a combined census and apportionment bill enacted on June 18, 1929, that establishes a permanent method for apportioning a constant 435 seats ...

* Reform Act

In the United Kingdom, Reform Act is most commonly used for legislation passed in the 19th century and early 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. ...