Great Locomotive Chase on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great Locomotive Chase (also known as Andrews' Raid or the Mitchel Raid) was a military raid that occurred April 12, 1862, in northern

After the Union capture of Fort Henry and

After the Union capture of Fort Henry and

James J. Andrews was a Kentucky-born civilian serving as a secret agent and scout in

James J. Andrews was a Kentucky-born civilian serving as a secret agent and scout in

James J. Andrews, a civilian scout and part-time spy, proposed a daring raid to Mitchel that would destroy the Western and Atlantic Railroad as a useful reinforcement and supply link to Chattanooga from Atlanta and the rest of Georgia. He recruited the men known later as the Andrews Raiders. These were the civilian William Hunter Campbell and 22 volunteer Union soldiers from three Ohio regiments: the

James J. Andrews, a civilian scout and part-time spy, proposed a daring raid to Mitchel that would destroy the Western and Atlantic Railroad as a useful reinforcement and supply link to Chattanooga from Atlanta and the rest of Georgia. He recruited the men known later as the Andrews Raiders. These were the civilian William Hunter Campbell and 22 volunteer Union soldiers from three Ohio regiments: the

The raid began on April 12, 1862, when the regular morning passenger train from Atlanta, with the locomotive ''

The raid began on April 12, 1862, when the regular morning passenger train from Atlanta, with the locomotive '' Thus delayed at the junction town of Kingston, as the first of the southbound freight evacuation trains approached, Andrews inquired of that train's conductor why his train was carrying a red marker flag on its rear car. Andrews was told that Confederate Railway officials in Chattanooga had been notified by Confederate Army officials that Mitchel was approaching Chattanooga from Stevenson, Alabama, intending to either capture or lay

Thus delayed at the junction town of Kingston, as the first of the southbound freight evacuation trains approached, Andrews inquired of that train's conductor why his train was carrying a red marker flag on its rear car. Andrews was told that Confederate Railway officials in Chattanooga had been notified by Confederate Army officials that Mitchel was approaching Chattanooga from Stevenson, Alabama, intending to either capture or lay

With the ''Texas'' still chasing the ''General'' tender-first, the two trains steamed through

With the ''Texas'' still chasing the ''General'' tender-first, the two trains steamed through

Confederate forces charged all the raiders with "acts of unlawful belligerency"; the civilians were charged as

Confederate forces charged all the raiders with "acts of unlawful belligerency"; the civilians were charged as

On March 20, the recently released raiders arrived in Washington DC, and the following day Pittenger wrote a letter to

On March 20, the recently released raiders arrived in Washington DC, and the following day Pittenger wrote a letter to

Both ''The General'' and ''The Texas'' survived the war and have been preserved in museums. ''The General'' is located at the

Both ''The General'' and ''The Texas'' survived the war and have been preserved in museums. ''The General'' is located at the

West Point website

* * * * * * * *

Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History

in Kennesaw, GA. Home of ''The General''.

Atlanta History Museum

Home of ''The Texas''.

Railfanning.org: The Andrews Raid

New Georgia Encyclopedia: Andrews Raid

The Tale of the Texas - Our American Stories

{{Authority control Rail transportation in Georgia (U.S. state) 1862 in Georgia (U.S. state) 1862 in rail transport Raids of the American Civil War Railway weapons Battles and conflicts without fatalities Military operations of the American Civil War in Georgia (U.S. state) April 1862 events

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. Volunteers from the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

, led by civilian scout James J. Andrews, commandeered a train, '' The General'', and took it northward toward Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020 ...

, doing as much damage as possible to the vital Western and Atlantic Railroad

The Western & Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia (W&A) is a railroad owned by the State of Georgia and currently leased by CSX, which CSX operates in the Southeastern United States from Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

It was fo ...

(W&A) line from Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

to Chattanooga as they went. They were pursued by Confederate forces at first on foot, and later on a succession of locomotive

A locomotive or engine is a rail transport vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. If a locomotive is capable of carrying a payload, it is usually rather referred to as a multiple unit, motor coach, railcar or power car; the ...

s, including '' The Texas'', for .

Because the Union men had cut the telegraph wires, the Confederates could not send warnings ahead to forces along the railway. Confederates eventually captured the raiders and quickly executed some as spies, including Andrews; some others were able to flee. The surviving raiders were the first to be awarded the newly-created Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

by the US Congress for their actions. As a civilian, Andrews was not eligible.

Military situation

After the Union capture of Fort Henry and

After the Union capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson was a fortress built early in 1862 by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to control the Cumberland River, which led to the heart of Tennessee, and thereby the Confederacy. The fort was named after Confederate general Da ...

in February, Confederate General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, figh ...

withdrew his forces from central Tennessee to reorganize. As part of this withdrawal, Johnston evacuated Nashville on February 23, surrendering this important industrial center to Union Brig. Gen.

The Book of Genesis (from Greek ; Hebrew: בְּרֵאשִׁית ''Bəreʾšīt'', "In hebeginning") is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its first word, ( "In the beginning"). ...

Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell (March 23, 1818November 19, 1898) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two great Civil War battles— Shiloh and Per ...

's Department of the Ohio

The Department of the Ohio was an administrative military district created by the United States War Department early in the American Civil War to administer the troops in the Northern states near the Ohio River.

1st Department 1861–1862

Gener ...

army and making it the first Confederate state capital to fall to the Union. After taking Nashville, Buell showed little inclination for further offensive operations, especially towards the pro-Union region of East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 count ...

. On March 11, Buell's army was merged into the new Department of the Mississippi under General Henry Halleck. In late March, Halleck ordered Buell southwest to reinforce Grant's army near Pittsburgh Landing on the Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other name ...

. Buell departed, leaving a 7,000-man garrison in Nashville along with Maj. Gen. Ormsby Mitchel's 10,000-man 3rd Division. Mitchel had earlier assisted in the capture of Nashville and accepted the surrender of the city. With the withdrawal of both Confederate and Union forces towards western Tennessee, central Tennessee became an economy of force operation. Facing minimal Confederate resistance, Mitchel moved his division southeast out of Nashville on March 18 towards Murfreesboro

Murfreesboro is a city in and county seat of Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 152,769 according to the 2020 census, up from 108,755 residents certified in 2010. Murfreesboro is located in the Nashville metropol ...

, arriving on March 20.

The first raid: March

James J. Andrews was a Kentucky-born civilian serving as a secret agent and scout in

James J. Andrews was a Kentucky-born civilian serving as a secret agent and scout in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

, for Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell (March 23, 1818November 19, 1898) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two great Civil War battles— Shiloh and Per ...

in the spring of 1862. Sometime before Buell departed Nashville in late March, Andrews presented him with a plan to take eight men to steal a train

In rail transport, a train (from Old French , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles that run along a railway track and transport people or freight. Trains are typically pulled or pushed by locomotives (often ...

in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, and drive it north. Buell would later confirm in August 1863 that he authorized this expedition. According to Andrews, a train engineer in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

was willing to defect to the Union with his train, if Andrews could supply a volunteer train crew to assist running the train, tearing up track, and burning bridges. The main target was the railway bridge at Bridgeport, Alabama, although future Andrews Raider William Pittenger believed Andrews also intended to target several other bridges in Georgia and Tennessee. The volunteers for this first raid all came from General Mitchel's division, which was encamped at Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Murfreesboro is a city in and county seat of Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 152,769 according to the 2020 census, up from 108,755 residents certified in 2010. Murfreesboro is located in the Nashville metropol ...

. Moving south forty miles on foot to the Confederate railhead

In the UK, railheading refers to the practice of travelling further than necessary to reach a rail service, typically by car. The phenomenon is common among commuters seeking a more convenient journey. Reasons for railheading include, but are ...

at Tullahoma, the raiders were then able to travel by train down to Marietta, Georgia

Marietta is a city in and the county seat of Cobb County, Georgia, United States. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 60,972. The 2019 estimate was 60,867, making it one of Atlanta's largest suburbs. Marietta is the fourth largest ...

. There, Andrews discovered the engineer had been pressed into service elsewhere. Andrews asked if any of the raiders knew how to operate a locomotive; when none did, he called the raid off. Two raiders were also confronted by Confederate soldiers while trying to cut the telegraph lines, but successfully pretended to be overworked wiremen. The raiders then returned north to Union lines, arriving about a week after they had departed. Andrews spent several additional days conducting reconnaissance on the Western and Atlantic Railroad before also departing back north to federal lines. None of the original raiders would volunteer for the second raid. One added that "he felt all the time he was in the enemy’s country as though he had a rope around his neck."

Background

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Ormsby M. Mitchel, commanding Federal troops in middle Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

, sought a way to contract or shrink the extent of the northern and western borders of the Confederacy by pushing them permanently away from and out of contact with the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. This could be done by first a southward and then an eastward penetration from the Union base at Nashville, which would seize and sever the Memphis & Charleston Railroad

The Memphis and Charleston Railroad, completed in 1857, was the first railroad in the United States to link the Atlantic Ocean with the Mississippi River. Chartered in 1846, the gauge railroad ran from Memphis, Tennessee to Stevenson, Alabama t ...

between Memphis and Chattanooga (at the time there were no other railway links between the Mississippi river and the east) and then capture the water and railway junction of Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

, Tennessee, thereby severing the Western Confederacy's contact with both the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys.

At the time, the standard means of capturing a city was by encirclement to cut it off from supplies and reinforcements, then would follow artillery bombardment and direct assault by massed infantry. However, Chattanooga's natural water and mountain barriers to its east and south made this nearly impossible with the forces that Mitchel had available. When the Union Army threatened Chattanooga, the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

would (from its naturally protected rear) first reinforce Chattanooga's garrison from Atlanta. When sufficient forces had been deployed to Chattanooga to stabilize the situation and hold the line, the Confederates would then launch a counterattack from Chattanooga with the advantage of a local superiority of men and materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

. It was this process that the Andrews raid sought to disrupt. If he could somehow block railroad reinforcement of the city from Atlanta to the southeast, Mitchel could take Chattanooga. The Union Army would then have rail reinforcement and supply lines to its rear, leading west to the Union-held stronghold and supply depot of Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and ...

.

Planning

James J. Andrews, a civilian scout and part-time spy, proposed a daring raid to Mitchel that would destroy the Western and Atlantic Railroad as a useful reinforcement and supply link to Chattanooga from Atlanta and the rest of Georgia. He recruited the men known later as the Andrews Raiders. These were the civilian William Hunter Campbell and 22 volunteer Union soldiers from three Ohio regiments: the

James J. Andrews, a civilian scout and part-time spy, proposed a daring raid to Mitchel that would destroy the Western and Atlantic Railroad as a useful reinforcement and supply link to Chattanooga from Atlanta and the rest of Georgia. He recruited the men known later as the Andrews Raiders. These were the civilian William Hunter Campbell and 22 volunteer Union soldiers from three Ohio regiments: the 2nd

A second is the base unit of time in the International System of Units (SI).

Second, Seconds or 2nd may also refer to:

Mathematics

* 2 (number), as an ordinal (also written as ''2nd'' or ''2d'')

* Second of arc, an angular measurement unit, ...

, 21st

21 (twenty-one) is the natural number following 20 and preceding 22.

The current century is the 21st century AD, under the Gregorian calendar.

In mathematics

21 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being 1, 3 and 7, and a defici ...

, and 33rd Ohio Infantry

The 33rd Ohio Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

The 33rd Ohio Infantry Regiment was organized at Portsmouth, Ohio, from August 5 through September 13, 1861. It was mustered ...

. Andrews instructed the men to arrive in Marietta, Georgia

Marietta is a city in and the county seat of Cobb County, Georgia, United States. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 60,972. The 2019 estimate was 60,867, making it one of Atlanta's largest suburbs. Marietta is the fourth largest ...

, by midnight of April 10, but heavy rain caused a one-day delay. They traveled in small parties in civilian attire to avoid arousing suspicion. All but two (Samuel Llewellyn and James Smith) reached the designated rendezvous point at the appointed time. Llewellyn and Smith joined a Confederate artillery unit, as they had been instructed to do in such circumstances. Andrews' proposal was a combined operation; General Mitchel and his forces would first move on Chattanooga; then, the Andrews’ Raid would promptly destroy the rail line between Chattanooga and Atlanta. These essentially simultaneous actions would bring about the capture of Chattanooga. Andrews' Raid was intended to deprive the Confederates of the integrated use of the railways to respond to a Union advance, using their interior lines of communication.

The plan was to steal a train on its run north towards Chattanooga, stopping to damage or destroy track, bridges, telegraph wires, and track switches behind them, so as to prevent the Confederate Army from being able to move troops and supplies from Atlanta to Chattanooga. The raiders planned to cross through the Federal siege lines on the outskirts of Chattanooga and rejoin Mitchel's army.

Because railway dining car

A dining car (American English) or a restaurant car (British English), also a diner, is a railroad passenger car that serves meals in the manner of a full-service, sit-down restaurant.

It is distinct from other railroad food service cars that do ...

s were not yet in common use, railroad timetables included water, rest, and meal stops. They planned to steal a train just north of Atlanta at Big Shanty, Georgia (now Kennesaw

Kennesaw is a suburban city northwest of Atlanta in Cobb County, Georgia, United States, located within the greater Atlanta metropolitan area. Known from its original settlement in the 1830s until 1887 as Big Shanty, it became Kennesaw under its ...

). They chose Big Shanty because they thought Big Shanty did not have a telegraph office and the stop would also be used to refuel and take on water for the steep grade further north.

The chase

Big Shanty to Kingston

The raid began on April 12, 1862, when the regular morning passenger train from Atlanta, with the locomotive ''

The raid began on April 12, 1862, when the regular morning passenger train from Atlanta, with the locomotive ''General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

'', stopped for breakfast at the Lacy Hotel. They took the ''General'' and the train's three boxcar

A boxcar is the North American (AAR) term for a railroad car that is enclosed and generally used to carry freight. The boxcar, while not the simplest freight car design, is considered one of the most versatile since it can carry most ...

s, which were behind the tender in front of the passenger cars. The passenger cars were left behind. Andrews had previously obtained from the work crew a crowbar for tearing up track.

The train's conductor, William Allen Fuller

William Allen Fuller (April 15, 1836 – December 28, 1905) was a conductor on the Western & Atlantic Railroad during the American Civil War era. He was most noted for his role in the 1862 Great Locomotive Chase, a daring sabotage mission a ...

, and two other men, chased the stolen train, first on foot, then by a handcar

A handcar (also known as a pump trolley, pump car, rail push trolley, push-trolley, jigger, Kalamazoo, velocipede, or draisine) is a railroad car powered by its passengers, or by people pushing the car from behind. It is mostly used as a railway ...

belonging to a work crew shortly north of Big Shanty. Locomotives of the time normally averaged , with short bursts of speed of about . In addition, the terrain north of Atlanta is very hilly, and the ruling grades are steep. Even today, average speeds are rarely greater than between Chattanooga and Atlanta. Since Andrews intended to stop periodically to perform acts of sabotage, a determined pursuer, even on foot, could conceivably have caught up with the train before it reached Chattanooga.

At Etowah, the raiders passed the older and smaller locomotive Yonah which was on a siding that led to the nearby Cooper Iron Works. Andrews considered stopping to attack and destroy that locomotive so it could not be used by pursuers, but given the size of its work party (even though unarmed) relative to the size of the raiding party, he judged that any firefight would be too long and too involved, and would alert nearby troops and civilians.

As the raiders had stolen a regularly scheduled train on a railroad with only one track, they needed to keep to that train's timetable. If they reached a siding ahead of schedule, they had to wait there until scheduled southbound trains passed them before they could continue north. Andrews claimed to the station masters he encountered that his train was a special northbound ammunition movement ordered by General Beauregard in support of his operations against the Union forces threatening Chattanooga. This story was sufficient for the isolated station masters Andrews encountered (as he had cut the telegraph wires to the south), but it had no impact upon the train dispatchers and station masters north of him, whose telegraph lines to Chattanooga were working. These dispatchers were following their orders to dispatch and control the special train movements southward at the highest priority.

Thus delayed at the junction town of Kingston, as the first of the southbound freight evacuation trains approached, Andrews inquired of that train's conductor why his train was carrying a red marker flag on its rear car. Andrews was told that Confederate Railway officials in Chattanooga had been notified by Confederate Army officials that Mitchel was approaching Chattanooga from Stevenson, Alabama, intending to either capture or lay

Thus delayed at the junction town of Kingston, as the first of the southbound freight evacuation trains approached, Andrews inquired of that train's conductor why his train was carrying a red marker flag on its rear car. Andrews was told that Confederate Railway officials in Chattanooga had been notified by Confederate Army officials that Mitchel was approaching Chattanooga from Stevenson, Alabama, intending to either capture or lay siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

to the city, and as a result of this warning, the Confederate Military Railways had ordered the Special Freight movements. The red train marker flag on the southbound train meant that there was at least one additional train behind the one which Andrews had just encountered, and that Andrews had no "authority for movement" until the last train of that sectional movement had passed him. The raiders being delayed at Kingston for over an hour, this gave Fuller all the time he needed to close the distance.

Kingston to Adairsville

The raiders finally pulled out of Kingston only moments before Fuller's arrival. They still managed north of Kingston again to cut the telegraph wire and break a rail. Meanwhile, moving north on the handcar, Fuller had spotted the locomotive '' Yonah'' at Etowah and commandeered it, chasing the raiders north all the way to Kingston. There, Fuller switched to the locomotive ''William R. Smith,'' which was on a sidetrack leading west to the town ofRome, Georgia

Rome is the largest city in and the county seat of Floyd County, Georgia, United States. Located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, it is the principal city of the Rome, Georgia, metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses all ...

and continued north towards Adairsville.

Two miles south of Adairsville, however, the pursuers were stopped by the broken track, forcing Fuller and his party to continue the pursuit on foot. Beyond the damaged section, he took command of the southbound locomotive ''Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

'' south of Calhoun, where Andrews had passed it, running it backwards. The ''Texas'' train crew had been bluffed by Andrews at Calhoun into taking the station siding, thereby allowing the ''General'' to continue northward along the single-track main line. Fuller, when he met the ''Texas'', took command of her, picked up eleven Confederate troops at Calhoun, and continued his pursuit, tender-first, northward.

Adairsville to Ringgold

The raiders now never got far ahead of Fuller and never had enough time to stop and take up a rail to halt the ''Texas''. Destroying the railway behind the hijacked train was a slow process. The raiders were too few in number and were too poorly equipped with the proper railway track tools and demolition equipment, and the rain that day made it difficult to burn the bridges. As well, railway officials in Chattanooga had sufficient time to evacuate engines and rolling stock to the south, hauling critical railroad supplies away from the Union threat, so as to prevent their either being captured by General Mitchel or trapped uselessly inside Chattanooga during a Union siege of the city. With the ''Texas'' still chasing the ''General'' tender-first, the two trains steamed through

With the ''Texas'' still chasing the ''General'' tender-first, the two trains steamed through Dalton

Dalton may refer to:

Science

* Dalton (crater), a lunar crater

* Dalton (program), chemistry software

* Dalton (unit) (Da), the atomic mass unit

* John Dalton, chemist, physicist and meteorologist

Entertainment

* Dalton (Buffyverse), minor ch ...

and Tunnel Hill. The raiders continued to sever the telegraph wires, but they were unable to burn bridges or damage Tunnel Hill. The wood they had hoped to burn was soaked by rain. Just before the raiders cut the telegraph wire north of Dalton, Fuller managed to send off a message from there alerting the authorities in Chattanooga of the approaching stolen engine.

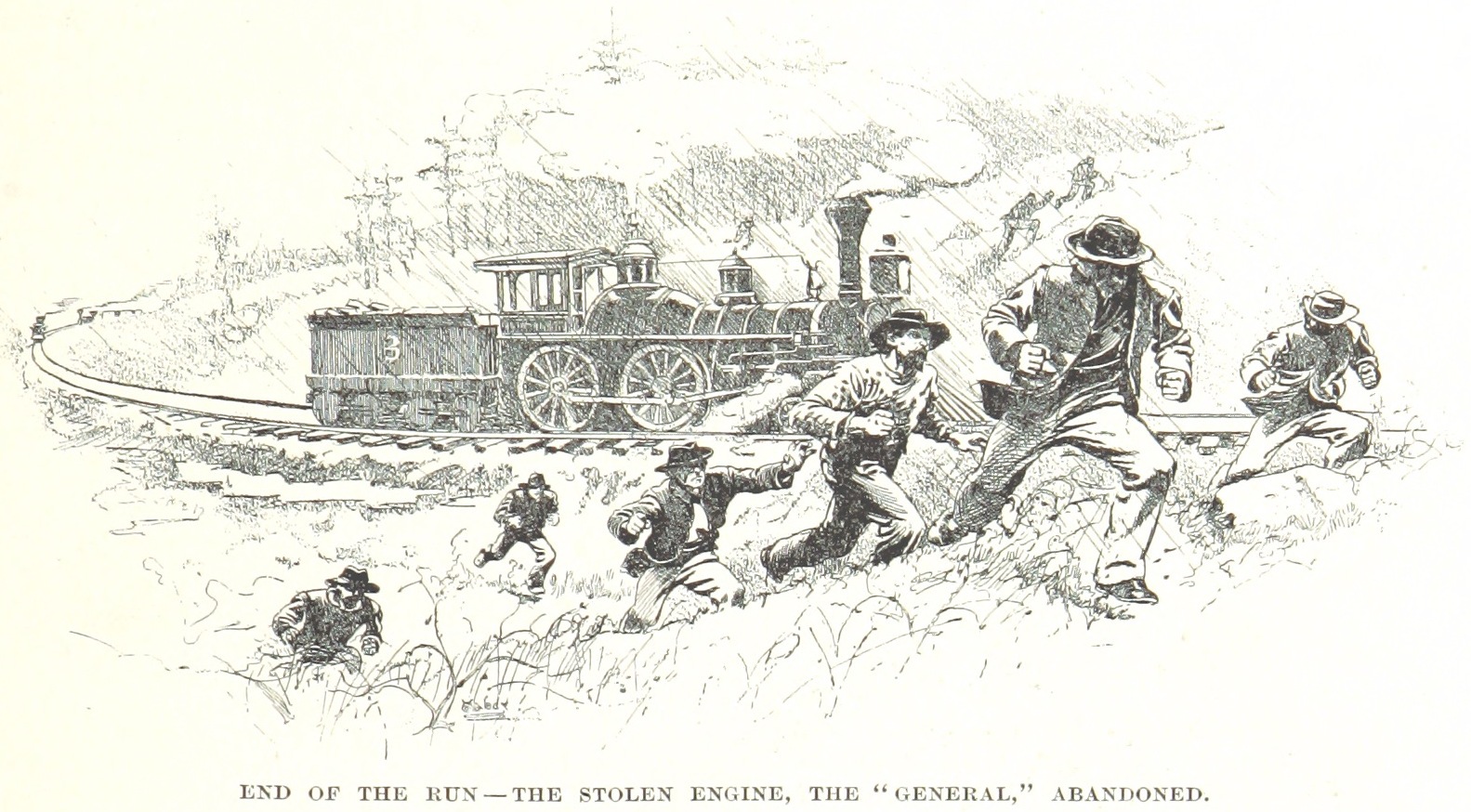

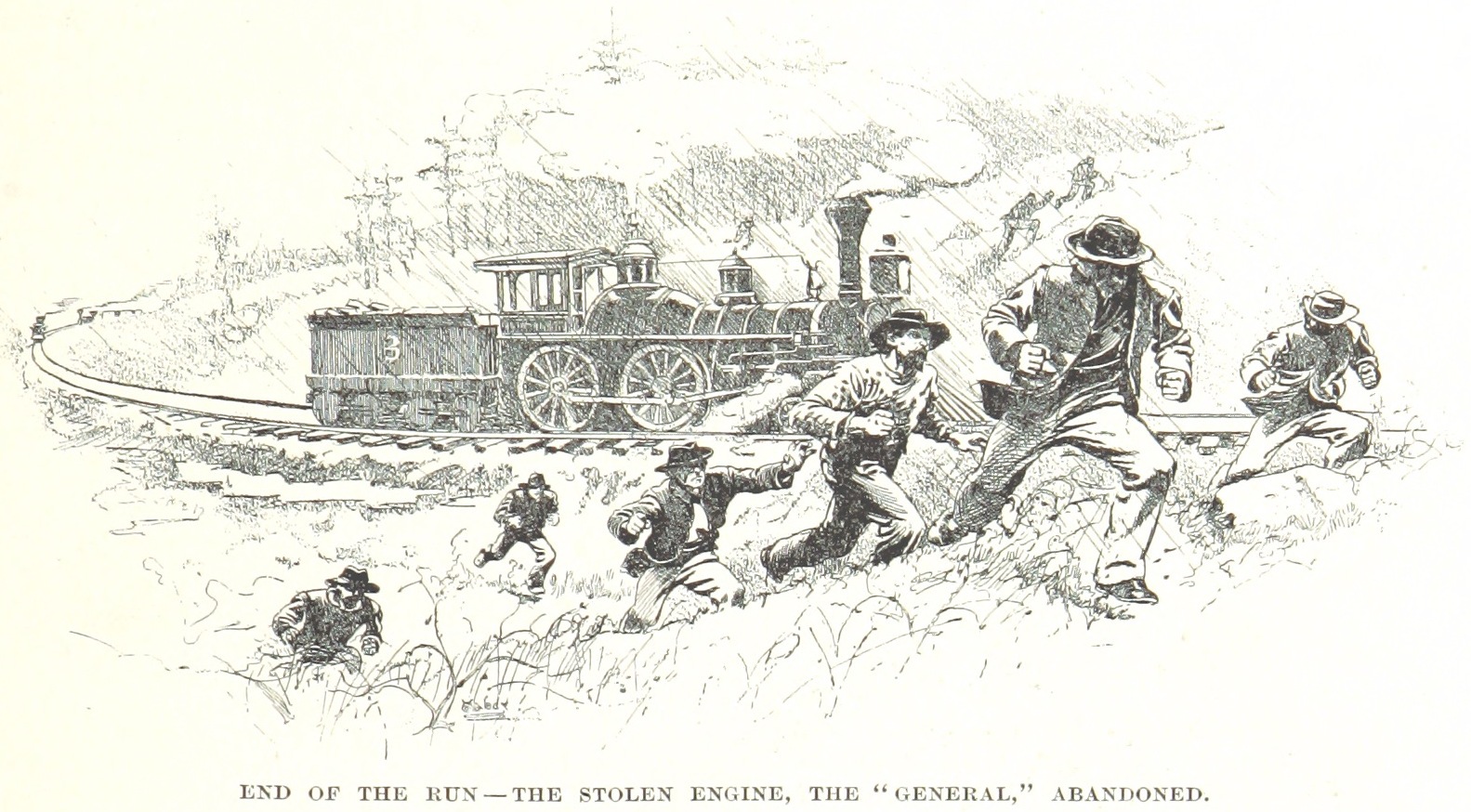

Finally, at milepost

A milestone is a numbered marker placed on a route such as a road, railway line, canal or boundary. They can indicate the distance to towns, cities, and other places or landmarks; or they can give their position on the route relative to ...

116.3, north of Ringgold, Georgia

Ringgold is a city in and the county seat of Catoosa County, Georgia, United States. Its population was 3,414 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Chattanooga, Tennessee–GA Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Ringgold was founded in 184 ...

, just 18 miles from Chattanooga, with the locomotive out of fuel, Andrews's men abandoned the ''General'' and scattered. Andrews and all of his men were caught within two weeks, including the two who had missed the hijacking. And Mitchel's attack on Chattanooga ultimately failed.

Aftermath

Trials and executions

Confederate forces charged all the raiders with "acts of unlawful belligerency"; the civilians were charged as

Confederate forces charged all the raiders with "acts of unlawful belligerency"; the civilians were charged as unlawful combatant

An unlawful combatant, illegal combatant or unprivileged combatant/belligerent is a person who directly engages in armed conflict in violation of the laws of war and therefore is claimed not to be protected by the Geneva Conventions.

The Internat ...

s and spies. All the prisoners were tried in military courts, or courts-martial. Tried in Chattanooga, Andrews was found guilty. He was executed by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

on June 7 in Atlanta. On June 18, seven others who had been transported to Knoxville and convicted as spies were returned to Atlanta and also hanged; their bodies were buried unceremoniously in an unmarked grave. They were later reburied in Chattanooga National Cemetery.

Escape and exchange

Writing about the exploit, Corporal William Pittenger said that the remaining raiders worried about also being executed. They attempted to escape and eight succeeded. Traveling for hundreds of miles in pairs, they all made it back safely to Union lines, including two who were aided by slaves and Union sympathizers and two who floated down theChattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chatt ...

until they were rescued by the Union blockade

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlanti ...

vessel USS ''Somerset'' in the Gulf of Mexico. The remaining six were held as prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

and exchanged for Confederate prisoners on March 17, 1863.

Medal of Honor

On March 20, the recently released raiders arrived in Washington DC, and the following day Pittenger wrote a letter to

On March 20, the recently released raiders arrived in Washington DC, and the following day Pittenger wrote a letter to Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin M. Stanton detailing their mission to Georgia. On March 24, they were interviewed by Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, who was able to corroborate details of their mission with testimony from the raiders who had escaped in 1862. On March 25, they were invited to Stanton's office at the Department of War War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

{{u ...

. After a brief conversation, Stanton announced that the raiders would receive the newly approved Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

. Private Jacob Parrott

Jacob Wilson Parrott (July 17, 1843 – December 22, 1908) was an American soldier and carpenter. He was the first recipient of the Medal of Honor, a new military award first presented by the United States Department of War to six Union Army ...

, who had been physically abused as a prisoner, was awarded the first. The others were Sergeant Elihu H. Mason, Corporals William Pittenger and William H. H. Reddick, and Privates William Bensinger

William Bensinger (January 14, 1840, to December 19, 1918) was an American soldier who fought for the Union in the American Civil War. On March 25, 1863, he was the second person given the country's highest award for bravery during combat, the M ...

and Robert Buffum

Robert Buffum (July 7, 1828 to July 20, 1871) was an American soldier who fought in the American Civil War. Buffum was the third person to receive the country's highest award for bravery during combat, the Medal of Honor, for his action during th ...

. Stanton also offered them all commissions as First Lieutenants. After the ceremony the six raiders were taken to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

to meet President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, which became a tradition for all Medal of Honor recipients. Later, all but three of the other soldiers who had participated in the raid also received the Medal of Honor, with posthumous awards to families for those who had been executed. As civilians, Andrews and Campbell were not eligible. In 2008, the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

passed a bill which would retroactively award the Medal of Honor to two of the three remaining raiders, Charles Perry Shadrack and George Davenport Wilson. However, as of 2020 it has not been acted upon. All the Medals of Honor presented to the Andrews Raiders used identical text.

Citation:

Legacy

Both ''The General'' and ''The Texas'' survived the war and have been preserved in museums. ''The General'' is located at the

Both ''The General'' and ''The Texas'' survived the war and have been preserved in museums. ''The General'' is located at the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History

The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History is a museum in Kennesaw, Georgia, that contains a collection of artifacts and relics from the American Civil War, as well as from railroads of the state of Georgia and surrounding regions. T ...

, in Kennesaw, Georgia, close to where the chase began. ''The Texas'' is at the Atlanta History Center

Atlanta History Center is a history museum and research center located in the Buckhead district of Atlanta, Georgia. The Museum was founded in 1926 and currently consists of nine permanent, and several temporary, exhibitions. Atlanta History Cen ...

.

The first account of the chase was published a year after the event in 1863 by William Pittenger, one of the Andrews Raiders, under the title of ''Daring and Suffering''. It would be republished in 1881 as ''Capturing a Locomotive'' and 1889 as ''The Great Locomotive Chase''. The book was a major success and was widely praised. Two decades later, one newspaper would claim it “was in half the old soldier households in the country.” In 1926, silent film actor Buster Keaton

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton (October 4, 1895 – February 1, 1966) was an American actor, comedian, and filmmaker. He is best known for his silent film work, in which his trademark was physical comedy accompanied by a stoic, deadpan expression ...

was given a copy of Pittenger's memoirs, and created the loosely-based silent film comedy '' The General''. In 1956, Walt Disney Productions

The Walt Disney Company, commonly known as Disney (), is an American multinational mass media and entertainment conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios complex in Burbank, California. Disney was originally founded on October 1 ...

released the dramatic film ''The Great Locomotive Chase

''The Great Locomotive Chase'' is a 1956 American adventure western film produced by Walt Disney Productions, based on the Great Locomotive Chase that occurred in 1862 during the American Civil War. Filmed in CinemaScope and in color, the fi ...

'', also based on Pittenger's memoirs, starring Fess Parker

Fess Elisha Parker Jr. (born F. E. Parker Jr.;Weaver, Tom.Sci-Fi Swarm and Horror Horde: Interviews with 62 Filmmakers p. 148 (McFarland 2012). August 16, 1924 – March 18, 2010),(March 18, 2010Daniel Boone Actor Fess Parker Dies at 85" ''CBS ...

as Andrews and Jeffrey Hunter

Jeffrey Hunter (born Henry Herman McKinnies Jr.; November 25, 1926 – May 27, 1969) was an American film and television actor and producer known for his roles in films such as ''The Searchers'' and ''King of Kings''. On television, Hunter ...

as Fuller and filmed on the Tallulah Falls Railway

The Tallulah Falls Railway, also known as the Tallulah Falls Railroad, "The TF" and "TF & Huckleberry," was a railroad based in Tallulah Falls, Georgia, U.S. which ran from Cornelia, Georgia to Franklin, North Carolina. It was commissioned by t ...

in North Carolina. Walt Disney

Walter Elias Disney (; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film p ...

, who personally supervised parts of the production, also rented the 4-4-0 locomotives ''William Mason William, Willie, or Willy Mason may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*William Mason (poet) (1724–1797), English poet, editor and gardener

*William Mason (architect) (1810–1897), New Zealand architect

*William Mason (composer) (1829–1908), Ame ...

'' to play ''The General'', the ''Inyo Inyo may refer to:

Places California

* Inyo County, California

* Inyo National Forest, USA

* The Inyo Mountains

* The Mono–Inyo Craters

Other uses

* Japanese for yin and yang

Yin and yang ( and ) is a Chinese philosophical concep ...

'' to play ''The Texas'', and ''Lafayette'' to play ''The Yonah''.

Since at least 1979, the city of Adairsville has held The Great Locomotive Chase Festival, a three-day festival in October which commemorates the event.

In 2000, composer Robert W. Smith wrote a concert piece named for and inspired by the incident.

In 2019, the raid was featured on Comedy Central show ''Drunk History

''Drunk History'' is an American educational comedy television series produced by Comedy Central, based on the Funny or Die web series created by Derek Waters and Jeremy Konner in 2007. They and Will Ferrell and Adam McKay are the show's ...

'' in the episode "Behind Enemy Lines", narrated by Jon Gabrus

Jon Gabrus (born January 31, 1982) is an American actor and comedian, best known for his work on ''Guy Code'', the podcast ''Comedy Bang! Bang!'', and TVLand's '' Younger''. He is a performer at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre and hosts th ...

, with John Francis Daley

John Francis Daley (born July 20, 1985) is an American actor, film director, producer, screenwriter, and musician. He is known for playing high school freshman Sam Weir on the NBC comedy-drama '' Freaks and Geeks'' and FBI criminal profiler D ...

portraying Andrews and Martin Starr

Martin James Pflieger Schienle (born July 30, 1982), professionally known as Martin Starr, is an American actor and comedian. He is known for the television roles of Bill Haverchuck on the short-lived comedy drama '' Freaks and Geeks'' (1999–2 ...

as Fuller.

Monument and markers

The Ohio monument dedicated to the Andrews Raiders is located at the Chattanooga National Cemetery. There is a scale model of the ''General'' on top of the monument, and a brief history of the Great Locomotive Chase. The ''General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

'' is now in the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History

The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History is a museum in Kennesaw, Georgia, that contains a collection of artifacts and relics from the American Civil War, as well as from railroads of the state of Georgia and surrounding regions. T ...

, Kennesaw, Georgia, while the ''Texas'' is on display at the Atlanta History Center

Atlanta History Center is a history museum and research center located in the Buckhead district of Atlanta, Georgia. The Museum was founded in 1926 and currently consists of nine permanent, and several temporary, exhibitions. Atlanta History Cen ...

.

One marker indicates where the chase began, near the Big Shanty Museum (now known as Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History) in Kennesaw, while another shows where the chase ended at Milepost 116.3, north of Ringgold — not far from the recently restored depot at Milepost 114.5.

Historic sites along the 1862 chase route include the following:

* marker near Big Shanty Museum

* Big Shanty Village Historic District

* Camp McDonald

* Acworth Downtown Historic District

* Tarleton Moore House

* Grand Theater (Cartersville, Georgia)

* Old Bartow County Courthouse, now the Bartow History Museum, built so close to the railroad that court was interrupted when any train passed, not built until 1869

* Adairsville Historic District

* the Calhoun Depot, built in 1852–53, at Calhoun, 10 miles north of Adairsville. with

* Calhoun Downtown Historic District

* William Taylor House (Resaca, Georgia), associated with northern Georgia soldiers who fought for the Union in the Civil War, though house not built until 1913

* Masonic Lodge No. 238, not built until 1915

* Dalton Commercial Historic District

* Western and Atlantic Depot, Dalton, Georgia

* Crown Mill Historic District

* Western and Atlantic Railroad Tunnel at Tunnel Hill

The Chetoogeta Mountain Tunnel () refers to two different railroad tunnels passing through Chetoogeta Mountain in Tunnel Hill, Georgia, United States.

The first tunnel, known as the Western and Atlantic Railroad Tunnel at Tunnel Hill, was comp ...

* Ringgold Gap Battlefield, gap between White Oak Mountain and Taylor Ridge through which railway runs, site of November 1863 battle protecting Confederate retreat after Battle of Missionary Ridge

The Battle of Missionary Ridge was fought on November 25, 1863, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign of the American Civil War. Following the Union victory in the Battle of Lookout Mountain on November 24, Union forces in the Military Division o ...

at Chattanooga

* Ringgold Depot

The Ringgold Depot, on what is now U.S. Route 41 in Ringgold, Georgia, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

It is a stone depot built as a station on the Western and Atlantic Railroad around 1850. Its sandstone wall ...

* Ringgold Commercial Historic District

* marker at milepost 116.3

Kennesaw House, 21 Depot St. (c.1845), a hotel on the L&N railway in Marietta, Georgia

Marietta is a city in and the county seat of Cobb County, Georgia, United States. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 60,972. The 2019 estimate was 60,867, making it one of Atlanta's largest suburbs. Marietta is the fourth largest ...

, is a contributing building in the Northwest Marietta Historic District

The Northwest Marietta Historic District is a historic district in Marietta, Georgia that was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. It includes Late Victorian, Greek Revival, Plantation Plain, and other architecture.

Th ...

. In 1862 this was the Fletcher House hotel where the Andrews Raiders stayed the night before commandeering '' The General''. with

There is a historical marker in downtown Atlanta, at the corner of 3rd and Juniper streets, at the site where Andrews was hanged.

See also

* East Tennessee bridge burnings * Henry P. Haney *List of Andrews Raiders

Participants in the Great Locomotive Chase, or Andrews's Raid, 1862.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Andrews

United States Army lists

Recipients of United States military awards and decorations

Lists of American military personnel

American Civil ...

* Samuel P. Carter

Samuel Perry "Powhatan" Carter (August 6, 1819 – May 26, 1891) was a United States naval officer who served in the Union Army as a brevet major general during the American Civil War and became a rear admiral in the postbellum United States Na ...

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at thWest Point website

* * * * * * * *

External links

Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History

in Kennesaw, GA. Home of ''The General''.

Atlanta History Museum

Home of ''The Texas''.

Railfanning.org: The Andrews Raid

New Georgia Encyclopedia: Andrews Raid

The Tale of the Texas - Our American Stories

{{Authority control Rail transportation in Georgia (U.S. state) 1862 in Georgia (U.S. state) 1862 in rail transport Raids of the American Civil War Railway weapons Battles and conflicts without fatalities Military operations of the American Civil War in Georgia (U.S. state) April 1862 events