Glenn Hammond Curtiss on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American

Between 1908 and 1910, the AEA produced four aircraft, each one an improvement over the last. Curtiss primarily designed the AEA's third aircraft, Aerodrome #3, the famous '' June Bug'', and became its test pilot, undertaking most of the proving flights. On July 4, 1908, he flew to win the

Between 1908 and 1910, the AEA produced four aircraft, each one an improvement over the last. Curtiss primarily designed the AEA's third aircraft, Aerodrome #3, the famous '' June Bug'', and became its test pilot, undertaking most of the proving flights. On July 4, 1908, he flew to win the

In August 1909, Curtiss took part in the ''

In August 1909, Curtiss took part in the ''

Curtiss custom built floats and adapted them onto a Model D so it could take off and land on water to prove the concept. On February 24, 1911, Curtiss made his first amphibious demonstration at North Island by taking off and alighting on both land and water. Back in Hammondsport, six months later in July 1911, Curtiss sold the U.S. Navy their first aircraft, the A-1 ''Triad''. The A-1, which was primarily a seaplane, was equipped with retractable wheels, also making it the first amphibious aircraft. Curtiss trained the Navy's first pilots and built their first aircraft. For this, he is considered in the US to be "The Father of Naval Aviation". The Triad was immediately recognized as so obviously useful, it was purchased by the U.S. Navy, Russia, Japan, Germany, and Britain. Curtiss won the Collier Trophy for designing this aircraft."The Curtiss Company"

Curtiss custom built floats and adapted them onto a Model D so it could take off and land on water to prove the concept. On February 24, 1911, Curtiss made his first amphibious demonstration at North Island by taking off and alighting on both land and water. Back in Hammondsport, six months later in July 1911, Curtiss sold the U.S. Navy their first aircraft, the A-1 ''Triad''. The A-1, which was primarily a seaplane, was equipped with retractable wheels, also making it the first amphibious aircraft. Curtiss trained the Navy's first pilots and built their first aircraft. For this, he is considered in the US to be "The Father of Naval Aviation". The Triad was immediately recognized as so obviously useful, it was purchased by the U.S. Navy, Russia, Japan, Germany, and Britain. Curtiss won the Collier Trophy for designing this aircraft."The Curtiss Company"

''US Centennial of Flight Commemoration'', 2003. Retrieved: January 28, 2011. Around this time, Curtiss met retired British naval officer

As 1916 approached, the United States was feared to be drawn into the conflict. The Army's

As 1916 approached, the United States was feared to be drawn into the conflict. The Army's

Curtiss and his family moved to Florida in the 1920s, where he founded 18 corporations, served on civic commissions, and donated extensive land and water rights. He co-developed the city of

Curtiss and his family moved to Florida in the 1920s, where he founded 18 corporations, served on civic commissions, and donated extensive land and water rights. He co-developed the city of

''aviation-history.com''. Retrieved: July 20, 2010. The Glenn Curtiss House, after years of disrepair and frequent vandalism, is being refurbished to serve as a museum in his honor. His frequent hunting trips into the Florida

at the

''Bell and Baldwin: Their Development of Aerodromes and Hydrodromes at Baddeck, Nova Scotia''

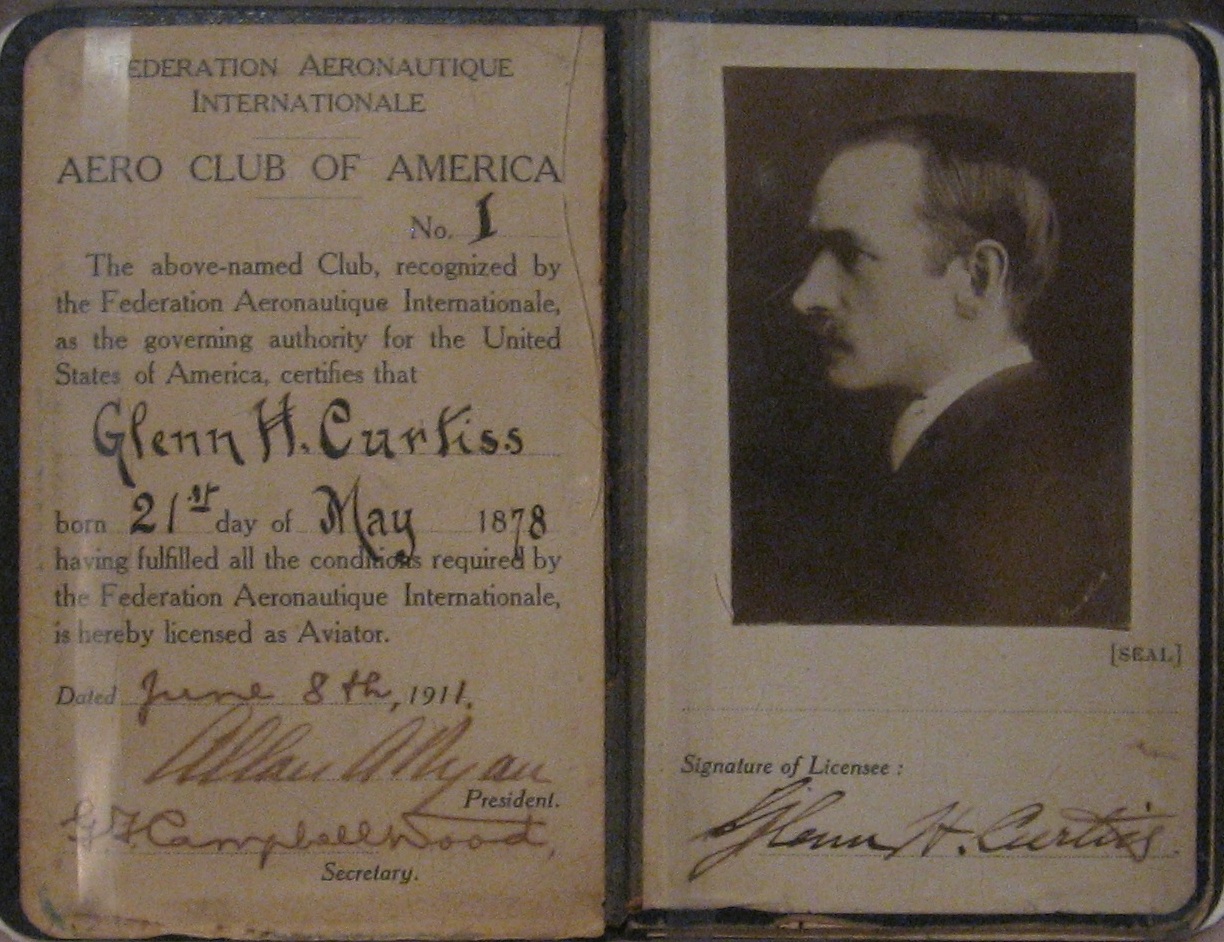

Toronto: *1911 Pilot license #1 issued for his ''June Bug'' flight

*1911 Ailerons patented

*1911 Developed first successful pontoon aircraft in US

*1911 Hydroplane A-1 Triad purchased by US. Navy (US Navy's first aircraft)

*1911 Developed first retractable landing gear on his hydroaeroplane

*1911 His first aircraft sold to U.S. Army on April 27

*1911 Created first military flying school

*1912 Developed and flew the first flying boat on Lake Keuka

*1912 First ship catapult launching on October 12 (Lt. Ellyson)Studer 1937, p. 258.

*1912 Created the first flying school in Florida at Miami Beach

*1911 Pilot license #1 issued for his ''June Bug'' flight

*1911 Ailerons patented

*1911 Developed first successful pontoon aircraft in US

*1911 Hydroplane A-1 Triad purchased by US. Navy (US Navy's first aircraft)

*1911 Developed first retractable landing gear on his hydroaeroplane

*1911 His first aircraft sold to U.S. Army on April 27

*1911 Created first military flying school

*1912 Developed and flew the first flying boat on Lake Keuka

*1912 First ship catapult launching on October 12 (Lt. Ellyson)Studer 1937, p. 258.

*1912 Created the first flying school in Florida at Miami Beach

*1914 Curtiss made a few short flights in the

*1914 Curtiss made a few short flights in the  *1923 (circa) Created first airboats

*1925 Built his Miami Springs mansion

*1926 Developed

*1923 (circa) Created first airboats

*1925 Built his Miami Springs mansion

*1926 Developed

"At Dayton"

''

''The Illustrated Directory of Motorcycles''.

St. Paul: Minnesota: MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company, 2002. . * Dizer, John T. ''Tom Swift & Company''. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 1982. . * FitzGerald-Bush, Frank S. ''A Dream of Araby: Glenn Curtiss and the Founding of Opa-locka''. Opa-locka, Florida: South Florida Archaeological Museum, 1976. * Harvey, Steve. ''It Started with a Steamboat: An American Saga''. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2005. . * Hatch, Alden. ''Glenn Curtiss: Pioneer of Aviation''. Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2007. . * House, Kirk W. ''Hell-Rider to King of the Air''. Warrendale, Pennsylvania: SAE International, 2003. . * Mitchell, Charles R. and Kirk W. House. ''Glenn H. Curtiss: Aviation Pioneer''. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001. . * Roseberry, C.R. ''Glenn Curtiss: Pioneer of Flight''. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1972. . * Shulman, Seth. ''Unlocking the Sky: Glenn Hammond Curtiss and the Race to Invent the Airplane''. New York:

"Speed Limit"

''Time'', October 29, 1923. * Studer, Clara. ''Sky Storming Yankee: The Life of Glenn Curtiss''. New York: Stackpole Sons, 1937. * Trimble, William F. ''Hero of the Air: Glenn Curtiss and the Birth of Naval Aviation''. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2010. .

Glenn Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, NY

National Aviation Hall of Fame: Glenn Curtiss

Retrieved May 26, 2011 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Curtiss, Glenn 1878 births 1930 deaths 19th-century American inventors 20th-century American inventors Aircraft designers Alexander Graham Bell American aerospace engineers American aviation record holders American male cyclists American motorcycle designers Aviation history of the United States Aviation pioneers Aviators from New York (state) Bicycle messengers Collier Trophy recipients Deaths from appendicitis International Motorsports Hall of Fame inductees Members of the Early Birds of Aviation Motorcycle land speed record people National Aviation Hall of Fame inductees People from Hammondsport, New York Cyclists from New York (state)

aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air craft such as hot a ...

and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early as 1904, he began to manufacture engines for airships. In 1908, Curtiss joined the Aerial Experiment Association

The Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) was a Canadian-American aeronautical research group formed on 30 September 1907, under the leadership of Dr. Alexander Graham Bell.

The AEA produced several different aircraft in quick succession, with eac ...

, a pioneering research group, founded by Alexander Graham Bell at Beinn Bhreagh, Nova Scotia

( ) is the name of the former estate of Alexander Graham Bell, in Victoria County, Nova Scotia. It refers to a peninsula jutting into Cape Breton Island's scenic Bras d'Or Lake approximately southeast of the village of Baddeck, forming the ...

, to build flying machines.

Curtiss won a race at the world's first international air meet in France and made the first long-distance flight in the U.S. His contributions in designing and building aircraft led to the formation of the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, which later merged into the Curtiss-Wright Corporation

The Curtiss-Wright Corporation is a manufacturer and services provider headquartered in Davidson, North Carolina, with factories and operations in and outside the United States. Created in 1929 from the consolidation of Curtiss, Wright, and v ...

. His company built aircraft for the U.S. Army and Navy, and, during the years leading up to World War I, his experiments with seaplanes led to advances in naval aviation. Curtiss civil and military aircraft were some of the most important types in the interwar and World War II eras.

Birth and early career

Glenn Curtiss was born in Hammondsport in theFinger Lakes

The Finger Lakes are a group of eleven long, narrow, roughly north–south lakes located south of Lake Ontario in an area called the ''Finger Lakes region'' in New York, in the United States. This region straddles the northern and transitional ...

region of New York in 1878. His mother was Lua Curtiss née Andrews and his father was Frank Richmond Curtiss a harness maker who had arrived in Hammondsport with Glenn's grandparents in 1876. Glenn's paternal grandparents were Claudius G. Curtiss, a Methodist Episcopal

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

clergyman

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, and Ruth Bramble. Glenn Curtiss had a younger sister, Rutha Luella, also born in Hammondsport.

Although his formal education extended only to eighth grade, his early interest in mechanics and inventions was evident at his first job at the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company (later Eastman Kodak Company

The Eastman Kodak Company (referred to simply as Kodak ) is an American public company that produces various products related to its historic basis in analogue photography. The company is headquartered in Rochester, New York, and is incorpor ...

) in Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a city in the U.S. state of New York, the seat of Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, and Yonkers, with a population of 211,328 at the 2020 United States census. Located in W ...

.Roseberry 1972, p. 10. He invented a stencil machine adopted at the plant and later built a rudimentary camera to study photography.

Marriage and family

On March 7, 1898, Curtiss married Lena Pearl Neff (1879–1951), daughter of Guy L. Neff and Jenny M. Potter, in Hammondsport, New York. They had two children: Carlton N. Curtiss (1901–1902) and Glenn Hammond Curtiss (1912–1969)Bicycles and motorcycles

Curtiss began his career as aWestern Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company cha ...

bicycle messenger, a bicycle racer, and bicycle-shop owner. In 1901, he developed an interest in motorcycles when internal-combustion engines became more available. In 1902, Curtiss began manufacturing motorcycles with his own single-cylinder engines. His first motorcycle's carburetor was adapted from a tomato soup can containing a gauze screen to pull the gasoline up by capillary action

Capillary action (sometimes called capillarity, capillary motion, capillary rise, capillary effect, or wicking) is the process of a liquid flowing in a narrow space without the assistance of, or even in opposition to, any external forces li ...

. In 1903, he set a motorcycle land speed record

The motorcycle land-speed record is the fastest speed achieved by a motorcycle on land. It is standardized as the speed over a course of fixed length, averaged over two runs in opposite directions. AMA National Land Speed Records requires 2 passes ...

at for one mile (1.6 km). When E.H. Corson of the Hendee Mfg Co (manufacturers of Indian motorcycles

Indian Motorcycle (or ''Indian'') is an American brand of motorcycles owned and produced by American automotive manufacturer Polaris Inc.Cambridge, Maryland

Cambridge is a city in Dorchester County, Maryland, United States. The population was 13,096 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Dorchester County and the county's largest municipality. Cambridge is the fourth most populous city in Mary ...

.

On January 24, 1907, Curtiss set an unofficial world record of , on a V-8-powered motorcycle of his own design and construction in Ormond Beach, Florida

Ormond Beach is a city in central Florida in Volusia County. The population was 43,080 at the 2020 census. Ormond Beach lies directly north of Daytona Beach and is a principal city of the Deltona–Daytona Beach–Ormond Beach, FL Metropolita ...

. The air-cooled F-head

The intake/inlet over exhaust, or "IOE" engine, known in the US as F-head, is a four-stroke internal combustion engine whose valvetrain comprises OHV inlet valves within the cylinder head and exhaust side-valves within the engine block.V.A.W H ...

engine was intended for use in aircraft. He remained "the fastest man in the world", the title the newspapers gave him, until 1911,Roseberry 1972, p. 57. and his motorcycle record was not broken until 1930. This motorcycle is now in the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. Curtiss's success at racing strengthened his reputation as a leading maker of high-performance motorcycles and engines.

Aviation pioneer

Curtiss, motor expert

In 1904, Curtiss became a supplier of engines for the California "aeronaut" Tom Baldwin. In that same year, Baldwin's ''California Arrow'', powered by a Curtiss 9 HP V-twin motorcycle engine, became the first successful dirigible in America.Roseberry 1972, p. 41. In 1907, Alexander Graham Bell invited Curtiss to develop a suitable engine for heavier-than-air flight experimentation. Bell regarded Curtiss as "the greatest motor expert in the country"Roseberry 1972, p. 71. and invited Curtiss to join hisAerial Experiment Association

The Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) was a Canadian-American aeronautical research group formed on 30 September 1907, under the leadership of Dr. Alexander Graham Bell.

The AEA produced several different aircraft in quick succession, with eac ...

(AEA).

AEA aircraft experiments

Between 1908 and 1910, the AEA produced four aircraft, each one an improvement over the last. Curtiss primarily designed the AEA's third aircraft, Aerodrome #3, the famous '' June Bug'', and became its test pilot, undertaking most of the proving flights. On July 4, 1908, he flew to win the

Between 1908 and 1910, the AEA produced four aircraft, each one an improvement over the last. Curtiss primarily designed the AEA's third aircraft, Aerodrome #3, the famous '' June Bug'', and became its test pilot, undertaking most of the proving flights. On July 4, 1908, he flew to win the Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

Trophy and its $2,500 prize. This was considered to be the first pre-announced public flight of a heavier-than-air flying machine in America. The flight of the ''June Bug'' propelled Curtiss and aviation firmly into public awareness. On June 8, 1911, Curtiss received U.S. Pilot's License #1 from the Aero Club of America

The Aero Club of America was a social club formed in 1905 by Charles Jasper Glidden and Augustus Post, among others, to promote aviation in America. It was the parent organization of numerous state chapters, the first being the Aero Club of New ...

, because the first batch of licenses were issued in alphabetical order; Wilbur Wright received license #5. At the culmination of the Aerial Experiment Association's experiments, Curtiss offered to purchase the rights to Aerodrome #3, essentially using it as the basis of his Curtiss No. 1

The Curtiss No. 1 also known as the Curtiss Gold Bug or Curtiss Golden Flyer was a 1900s American early experimental aircraft, the first independent aircraft designed and built by Glenn Curtiss.

Development

After his success with designing airc ...

, the first of his production series of pusher aircraft.

The pre-war years

Aviation competitions

After a 1909 fall-out with the AEA, Curtiss joined with A. M. Herring (and backers from theAero Club of America

The Aero Club of America was a social club formed in 1905 by Charles Jasper Glidden and Augustus Post, among others, to promote aviation in America. It was the parent organization of numerous state chapters, the first being the Aero Club of New ...

) to found the Herring-Curtiss Company

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (1909 – 1929) was an American aircraft manufacturer originally founded by Glenn Hammond Curtiss and Augustus Moore Herring in Hammondsport, New York. After significant commercial success in its first decade ...

in Hammondsport. During the 1909–1910 period, Curtiss employed a number of demonstration pilots, including Eugene Ely

Eugene Burton Ely (October 21, 1886 – October 19, 1911) was an American aviation pioneer, credited with the first shipboard aircraft take off and landing.

Background

Ely was born in Williamsburg, Iowa, and raised in Davenport, Iowa. Having c ...

, Charles K. Hamilton

Charles Keeney Hamilton (May 30, 1885 – January 22, 1914) was an American pioneer aviator nicknamed the "crazy man of the air". He was, in the words of the U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, "known for his dangerous dives, spectacular cras ...

, J.A.D. McCurdy

John Alexander Douglas McCurdy (2 August 1886 – 25 June 1961) was a Canadian aviation pioneer and the 20th Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia from 1947 to 1952.

Early years

Son of inventor Arthur Williams McCurdy and born in Baddeck, Nova S ...

, Augustus Post

Augustus Thomas Post Jr. (8 December 1873 – 4 October 1952) was an American adventurer who distinguished himself as an automotive pioneer, balloonist, early aviator, writer, actor, musician and lecturer. Post pursued an interest in transp ...

, and Hugh Robinson. Aerial competitions and demonstration flights across North America helped to introduce aviation to a curious public; Curtiss took full advantage of these occasions to promote his products. This was a busy period for Glenn Curtiss.

In August 1909, Curtiss took part in the ''

In August 1909, Curtiss took part in the ''Grande Semaine d'Aviation

The ''Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne'' was an 8-day aviation meeting held near Reims in France in 1909, so-named because it was sponsored by the major local champagne growers. It is celebrated as the first international public flying e ...

'' aviation meeting at Reims, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, organized by the Aéro-Club de France

The Aéro-Club de France () was founded as the Aéro-Club on 20 October 1898 as a society 'to encourage aerial locomotion' by Ernest Archdeacon, Léon Serpollet, Henri de la Valette, Jules Verne and his wife, André Michelin, Albert de Dion, ...

. The Wrights, who were selling their machines to customers in Germany at the time, decided not to compete in person. Two Wright aircraft (modified with a landing gear) were at the meet, but they did not win any events. On August 28, 1909, flying his No. 2 biplane, Curtiss won the overall speed event, the Gordon Bennett Cup, completing the 20-km (12.5-mile) course in just under 16 minutes at a speed of , six seconds faster than runner-up Louis Blériot.

On May 29, 1910, Curtiss flew from Albany to New York City to make the first long-distance flight between two major cities in the U.S. For this flight, which he completed in just under four hours including two stops to refuel, he won a $10,000 prize offered by publisher Joseph Pulitzer

Joseph Pulitzer ( ; born Pulitzer József, ; April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911) was a Hungarian-American politician and newspaper publisher of the '' St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' and the ''New York World''. He became a leading national figure in ...

and was awarded permanent possession of the Scientific American Trophy.

In June 1910, Curtiss provided a simulated bombing demonstration to naval officers at Hammondsport. Two months later, Lt. Jacob E. Fickel demonstrated the feasibility of shooting at targets on the ground from an aircraft with Curtiss serving as pilot. One month later, in September, he trained Blanche Stuart Scott, who was possibly the first American woman pilot. The fictional character Tom Swift

Tom Swift is the main character of six series of American juvenile science fiction and adventure novels that emphasize science, invention, and technology. First published in 1910, the series totals more than 100 volumes. The character was ...

, who first appeared in 1910 in ''Tom Swift and His Motor Cycle

''Tom Swift and His Motor Cycle, or, Fun and Adventure on the Road'', is Volume 1 in the original Tom Swift novel series published by Grosset & Dunlap.

Plot summary

Tom Swift, in his first adventure, has purchased a motorcycle and immediately ...

'' and ''Tom Swift and His Airship

''Tom Swift and His Airship'', or, The Stirring Cruise of the Red Cloud, is Volume 3 in the original Tom Swift novel series published by Grosset & Dunlap.

Plot summary

In Tom Swift and His Airship, Tom Swift has finished his latest invention- ...

'', has been said to have been based on Glenn Curtiss.Dizer 1982, p. 35. The Tom Swift books are set in a small town on a lake in upstate New York.

Patent dispute

A patent lawsuit by the Wright brothers against Curtiss in 1909 continued until it was resolved during World War I. Since the last Wright aircraft, the Wright Model L, was a single prototype of a "scouting" aircraft, made in 1916, the U.S. government, desperately short of combat aircraft, pressured both firms to resolve the dispute. Of nine suits Wright brought against Curtiss and others and the three suits brought against them, the Wright Brothers eventually won every case in courts in the United States.Naval aviation

On November 14, 1910, Curtiss demonstration pilotEugene Ely

Eugene Burton Ely (October 21, 1886 – October 19, 1911) was an American aviation pioneer, credited with the first shipboard aircraft take off and landing.

Background

Ely was born in Williamsburg, Iowa, and raised in Davenport, Iowa. Having c ...

took off from a temporary platform mounted on the forward deck of the cruiser USS ''Birmingham''. His successful takeoff and ensuing flight to shore marked the beginning of a relationship between Curtiss and the Navy that remained significant for decades. At the end of 1910, Curtiss established a winter encampment at San Diego to teach flying to Army and Naval personnel. Here, he trained Lt. Theodore Ellyson

Theodore Gordon Ellyson, USN (27 February 1885 – 27 February 1928), nicknamed "Spuds", was the first United States Navy officer designated as an aviator (" Naval Aviator No. 1"). Ellyson served in the experimental development of aviation ...

, who became U.S. Naval Aviator #1, and three Army officers, 1st Lt. Paul W. Beck

Paul Ward Beck (1 December 18764 April 1922) was an officer in the United States Army, an aviation pioneer, and one of the first military pilots. Although a career Infantry officer, Beck twice was part of the first aviation services of the U.S. ...

, 2nd Lt. George E. M. Kelly, and 2nd Lt. John C. Walker, Jr., in the first military aviation school. ( Chikuhei Nakajima, founder of Nakajima Aircraft Company

The was a prominent Japanese aircraft manufacturer and aviation engine manufacturer throughout World War II. It continues as the car and aircraft manufacturer Subaru.

History

The Nakajima Aircraft company was Japan's first aircraft manufactur ...

, was a 1912 graduate.) The original site of this winter encampment is now part of Naval Air Station North Island

Naval Air Station North Island or NAS North Island , at the north end of the Coronado peninsula on San Diego Bay in San Diego, California, is part of the largest aerospace-industrial complex in the United States Navy – Naval Base Coronado (N ...

and is referred to by the Navy as "The Birthplace of Naval Aviation".

Through the course of that winter, Curtiss was able to develop a float (pontoon) design that enabled him to take off and land on water. On January 26, 1911, he flew the first seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

from the water in the United States. Demonstrations of this advanced design were of great interest to the Navy, but more significant, as far as the Navy was concerned, was Eugene Ely successfully landing his Curtiss pusher (the same aircraft used to take off from the ''Birmingham'') on a makeshift platform mounted on the rear deck of the battleship USS ''Pennsylvania''. This was the first arrester-cable landing on a ship and the precursor of modern-day carrier operations. On January 28, 1911, Ellyson took off in a Curtiss “grass cutter” to become the first Naval aviator.

Curtiss custom built floats and adapted them onto a Model D so it could take off and land on water to prove the concept. On February 24, 1911, Curtiss made his first amphibious demonstration at North Island by taking off and alighting on both land and water. Back in Hammondsport, six months later in July 1911, Curtiss sold the U.S. Navy their first aircraft, the A-1 ''Triad''. The A-1, which was primarily a seaplane, was equipped with retractable wheels, also making it the first amphibious aircraft. Curtiss trained the Navy's first pilots and built their first aircraft. For this, he is considered in the US to be "The Father of Naval Aviation". The Triad was immediately recognized as so obviously useful, it was purchased by the U.S. Navy, Russia, Japan, Germany, and Britain. Curtiss won the Collier Trophy for designing this aircraft."The Curtiss Company"

Curtiss custom built floats and adapted them onto a Model D so it could take off and land on water to prove the concept. On February 24, 1911, Curtiss made his first amphibious demonstration at North Island by taking off and alighting on both land and water. Back in Hammondsport, six months later in July 1911, Curtiss sold the U.S. Navy their first aircraft, the A-1 ''Triad''. The A-1, which was primarily a seaplane, was equipped with retractable wheels, also making it the first amphibious aircraft. Curtiss trained the Navy's first pilots and built their first aircraft. For this, he is considered in the US to be "The Father of Naval Aviation". The Triad was immediately recognized as so obviously useful, it was purchased by the U.S. Navy, Russia, Japan, Germany, and Britain. Curtiss won the Collier Trophy for designing this aircraft."The Curtiss Company"''US Centennial of Flight Commemoration'', 2003. Retrieved: January 28, 2011. Around this time, Curtiss met retired British naval officer

John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Colonel John Cyril Porte, (26 February 1884 – 22 October 1919) was a British flying boat pioneer associated with the First World War Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.

Early life and career

Porte was born on 26 Feb ...

, who was looking for a partner to produce an aircraft with him to win the '' Daily Mail'' prize for the first transatlantic crossing

Transatlantic crossings are passages of passengers and cargo across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe or Africa and the Americas. The majority of passenger traffic is across the North Atlantic between Western Europe and North America. Centuries ...

. In 1912, Curtiss produced the two-seat ''Flying Fish

The Exocoetidae are a family of marine fish in the order Beloniformes class Actinopterygii, known colloquially as flying fish or flying cod. About 64 species are grouped in seven to nine genera. While they cannot fly in the same way a bird d ...

'', a larger craft that became classified as a flying boat because the hull sat in the water; it featured an innovative notch (known as a "step") in the hull that Porte recommended for breaking clear of the water at takeoff

Takeoff is the phase of flight in which an aerospace vehicle leaves the ground and becomes airborne. For aircraft traveling vertically, this is known as liftoff.

For aircraft that take off horizontally, this usually involves starting with a ...

. Curtiss correctly surmised that this configuration was more suited to building a larger long-distance craft that could operate from water, and was also more stable when operating from a choppy surface. With the backing of Rodman Wanamaker, Porte and Curtiss produced the ''America'' in 1914, a larger flying boat with two engines, for the transatlantic crossing.

World War I and later

World War I

With the start ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Porte returned to service in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, which subsequently purchased several models of the ''America'', now called the H-4, from Curtiss. Porte licensed and further developed the designs, constructing a range of Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town in Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest Containerization, container port in the United Kingdom. Felixstowe is approximately 116km (72 miles) northea ...

long-range patrol aircraft, and from his experience passed along improvements to the hull to Curtiss. The later British designs were sold to the U.S. forces, or built by Curtiss as the F5L. The Curtiss factory also built a total of 68 "Large Americas", which evolved into the H-12, the only American designed and built aircraft to see combat in World War I.

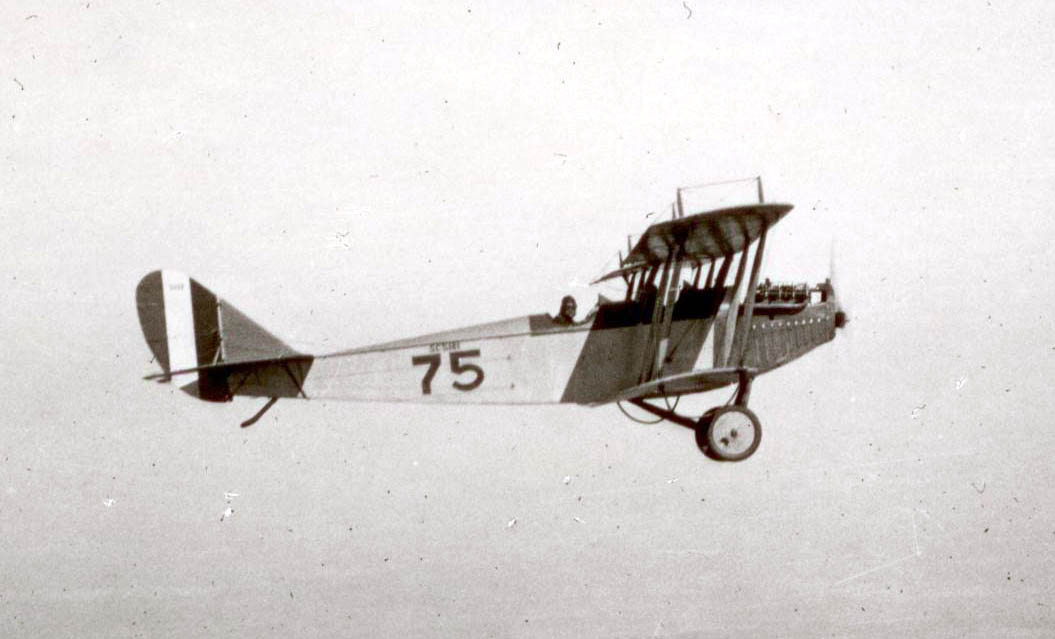

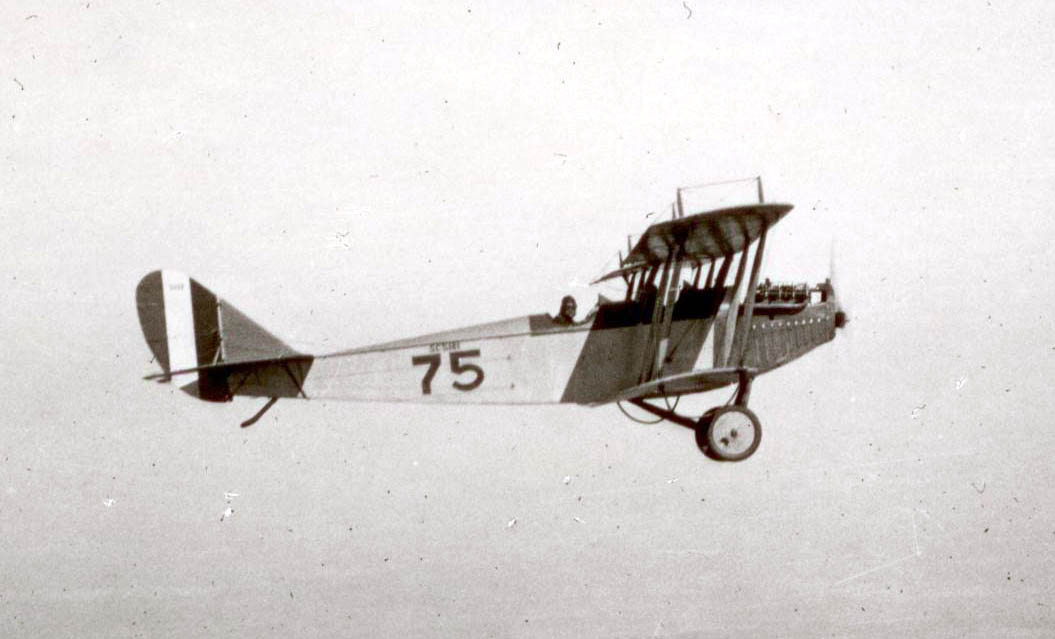

As 1916 approached, the United States was feared to be drawn into the conflict. The Army's

As 1916 approached, the United States was feared to be drawn into the conflict. The Army's Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps

The Aviation Section, Signal Corps, was the aerial warfare service of the United States from 1914 to 1918, and a direct statutory ancestor of the United States Air Force. It absorbed and replaced the Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps, and con ...

ordered the development of a simple, easy-to-fly-and-maintain, two-seat trainer. Curtiss created the JN-4 "Jenny" for the Army, and the N-9 seaplane version for the Navy. They were some of the most famous products of the Curtiss company, and thousands were sold to the militaries of the United States, Canada, and Britain. Civilian and military aircraft demand boomed, and the company grew to employ 18,000 workers in Buffalo and 3,000 workers in Hammondsport.

In 1917, the U.S. Navy commissioned Curtiss to design a long-range, four-engined flying boat large enough to hold a crew of five, which became known as the Curtiss NC

The Curtiss NC (Curtiss Navy Curtiss, nicknamed "Nancy boat" or "Nancy") was a flying boat built by Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company and used by the United States Navy from 1918 through the early 1920s. Ten of these aircraft were built, the mos ...

. Three of the four NC flying boats built attempted a transatlantic crossing in 1919. Thus NC-4

The NC-4 was a Curtiss NC flying boat that was the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, albeit not non-stop. The NC designation was derived from the collaborative efforts of the Navy (N) and Curtiss (C). The NC series flying boats w ...

became the first aircraft to be flown across the Atlantic Ocean, (a feat quickly overshadowed by the first non-stop atlantic crossing by Alcock and Brown,) while NC-1 and NC-3 were unable to continue past the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

. NC-4 is now on permanent display in the National Museum of Naval Aviation

The National Naval Aviation Museum, formerly known as the National Museum of Naval Aviation and the Naval Aviation Museum, is a military and aerospace museum located at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.

Founded in 1962 and moved to its curr ...

in Pensacola, Florida.

Post-World War I

Peace brought cancellation of wartime contracts. In September 1920, the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company underwent a financial reorganization. Glenn Curtiss cashed out his stock in the company for $32 million and retired to Florida. He continued on as a director of the company, but served only as an adviser on design. Clement M. Keys gained control of the company, which later became the nucleus of a large group of aviation companies.Later years

Curtiss and his family moved to Florida in the 1920s, where he founded 18 corporations, served on civic commissions, and donated extensive land and water rights. He co-developed the city of

Curtiss and his family moved to Florida in the 1920s, where he founded 18 corporations, served on civic commissions, and donated extensive land and water rights. He co-developed the city of Hialeah

Hialeah ( ; ) is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. With a population of 223,109 as of the 2020 census, Hialeah is the sixth-largest city in Florida. It is the second largest city by population in the Miami metropolitan area, whi ...

with James Bright and developed the cities of Opa-locka

Opa-locka is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 16,463, up from 15,219 in 2010. The city was developed by Glenn Curtiss. Developed based on a ''One Thousand and One Nights'' theme, Op ...

and Miami Springs, where he built a family home, known variously as the Miami Springs Villas House, Dar-Err-Aha, MSTR No. 2, or Glenn Curtiss House."The Life and Times of Glenn Hammond Curtiss"''aviation-history.com''. Retrieved: July 20, 2010. The Glenn Curtiss House, after years of disrepair and frequent vandalism, is being refurbished to serve as a museum in his honor. His frequent hunting trips into the Florida

Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region of tropical wetlands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orlando with the Kissim ...

led to a final invention, the Adams Motor "Bungalo", a forerunner of the modern recreational vehicle trailer (named after his business partner and half-brother, G. Carl Adams). Curtiss later developed this into a larger, more elaborate fifth-wheel vehicle, which he manufactured and sold under the name Aerocar. Shortly before his death, he designed a tailless aircraft with a V-shaped wing and tricycle landing gear that he hoped could be sold in the price range of a family car.

The Wright Aeronautical

Wright Aeronautical (1919–1929) was an American aircraft manufacturer headquartered in Paterson, New Jersey. It was the successor corporation to Wright-Martin. It built aircraft and was a supplier of aircraft engines to other builders in the ...

Corporation, a successor to the original Wright Company, ultimately merged with the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company on July 5, 1929, forming the Curtiss-Wright

The Curtiss-Wright Corporation is a manufacturer and services provider headquartered in Davidson, North Carolina, with factories and operations in and outside the United States. Created in 1929 from the consolidation of Curtiss, Wright, and v ...

company, shortly before Curtiss's death.

Controversies

Curtiss, working with the head of the Smithsonian Institution Charles Walcott, sought to discredit the Wrights and rehabilitate the reputation of Samuel Langley, a former head of the Smithsonian, who failed in his attempt at powered flight. Secretly, Curtiss extensively modified Langley's 1903 aerodrome (aircraft) then demonstrated in 1914 that it could fly. In turn, the Smithsonian endorsed the false statement that "Professor Samuel P. Langley had actually designed and built the first man-carrying flying machine capable of sustained flight." Walcott ordered the plane modified by Curtiss to be returned to its original 1903 condition before going on display at the Smithsonian to cover up the deception. In 1928 the Smithsonian Board of Regents reversed its position and acknowledged that the Wright Brothers deserved the credit for the first flight.Death

Traveling to Rochester to contest a lawsuit brought by former business partner August Herring, Curtiss suffered an attack ofappendicitis

Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms. Severe complications of a ru ...

in court. He died on July 23, 1930, in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, of complications from an appendectomy. His funeral service was held at St. James Episcopal Church in his home town, Hammondsport, with interment in the family plot at Pleasant Valley Cemetery in Hammondsport.

Awards and honors

By an act of Congress on March 1, 1933, Curtiss was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, which now resides in theSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. Curtiss was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame

The National Aviation Hall of Fame (NAHF) is a museum, annual awards ceremony and learning and research center that was founded in 1962 as an Ohio non-profit corporation in Dayton, Ohio, United States, known as the "Birthplace of Aviation" with it ...

in 1964, the International Aerospace Hall of Fame in 1965, the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America

The Motorsports Hall of Fame of America (MSHFA) is hall of fame that honors motorsports competitors and contributors from the United States from all disciplines, with categories for Open Wheel, Stock Cars, Powerboats, Drag Racing, Motorcycles, ...

in 1990,Glenn Curtissat the

Motorsports Hall of Fame of America

The Motorsports Hall of Fame of America (MSHFA) is hall of fame that honors motorsports competitors and contributors from the United States from all disciplines, with categories for Open Wheel, Stock Cars, Powerboats, Drag Racing, Motorcycles, ...

the Motorcycle Hall of Fame

The AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum is an offshoot of the American Motorcyclist Association, recognizing individuals who have contributed to motorcycle sport, motorcycle construction, or motorcycling in general. It also displays motorcycle ...

in 1998, and the National Inventors Hall of Fame

The National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) is an American not-for-profit organization, founded in 1973, which recognizes individual engineers and inventors who hold a U.S. patent of significant technology. Besides the Hall of Fame, it also oper ...

in 2003. The Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum has a collection of Curtiss's original documents as well as a collection of airplanes, motorcycles and motors. LaGuardia Airport

LaGuardia Airport is a civil airport in East Elmhurst, Queens, New York City. Covering , the facility was established in 1929 and began operating as a public airport in 1939. It is named after former New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia ...

was originally called Glenn H. Curtiss Airport when it began operation in 1929.

Other Curtiss honors include: Naval Aviation Hall of Honor; OX-5 Aviation Pioneers Hall of Fame; Empire State Aviation Hall of Fame; Niagara Frontier Aviation and Space Hall of Fame; International Air & Space Hall of Fame; Long Island Air & Space Hall of Fame; Great Floridians 2000; Steuben County (NY) Hall of Fame; Hammondsport School Lifetime Achievements Wall of Fame; Florida Aviation Hall of Fame; Smithsonian Institution Langley Medal; Top 100 Stars of Aerospace and Aviation; Doctor of Science (''honoris causa''), University of Miami.

The Glenn H. Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport is dedicated to Curtiss's life and work.

There is a Curtiss Avenue in Hammondsport, NY, along with the Glenn Curtiss Elementary School. Carson, CA has Glenn Hammond Curtiss Middle School and Glenn Curtiss Street. Glenn H. Curtiss Road is in San Diego, CA, and Glenn Curtiss Boulevard in East Meadow/Uniondale, NY (Long Island). Glenn Curtiss Drive is in Addison, TX, and Curtiss Parkway in Miami Springs, FL. Buffalo, NY has a Curtiss Park and a Curtis Parkway (named for Glenn despite the incorrect spelling). The Curtiss E-Library in Hialeah, FL was originally the Lua A. Curtiss Branch Library, named for Glenn's mother.

Curtiss appeared on the cover of ''Time'' in 1924, on a U. S. airmail stamp

An airmail stamp is a postage stamp intended to pay either an airmail fee that is charged in addition to the surface rate, or the full airmail rate, for an item of mail to be transported by air.

Airmail stamps should not be confused with airma ...

, and on a Micronesian stamp. Curtiss airplanes appear on 15 U. S. stamps (including the first air mail stamps), and on the stamps of at least 17 other countries.

Timeline

*1878 Birth in Hammondsport, New York *1898 Marriage *1900 Manufactures Hercules bicycles *1901 Motorcycle designer and racer *1903 American motorcycle champion *1903 Unofficial one-milemotorcycle land speed record

The motorcycle land-speed record is the fastest speed achieved by a motorcycle on land. It is standardized as the speed over a course of fixed length, averaged over two runs in opposite directions. AMA National Land Speed Records requires 2 passes ...

on Hercules V8 at Yonkers, New York

Yonkers () is a city in Westchester County, New York, United States. Developed along the Hudson River, it is the third most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City and Buffalo. The population of Yonkers was 211,569 as en ...

*1904 Thomas Scott Baldwin

Thomas Scott Baldwin (June 30, 1854 – May 17, 1923) was a pioneer balloonist and U.S. Army major during World War I. He was the first American to descend from a balloon by parachute.

Early career

Thomas Scott Baldwin was born on June 30, 18 ...

mounts Curtiss motorcycle engine on a hydrogen-filled dirigible

*1904 Set 10-mile world speed record

*1904 Invented handlebar throttle control; also credited to the 1867–1869 Roper steam velocipede

The Roper steam velocipede was a steam-powered velocipede built by inventor Sylvester H. Roper of Roxbury, Boston, Massachusetts, United States sometime from 1867–1869. It is one of three machines which have been called the first motorcycle, a ...

*1905 Created G.H. Curtiss Manufacturing Company, Inc.

*1906 Curtiss writes the Wright brothers offering them an aeronautical motor

*1907 Curtiss joins Alexander Graham Bell in experimenting in aircraft

*1907 Set world motorcycle land speed record

The motorcycle land-speed record is the fastest speed achieved by a motorcycle on land. It is standardized as the speed over a course of fixed length, averaged over two runs in opposite directions. AMA National Land Speed Records requires 2 passes ...

of de Cet 2003, p. 116.

*1907 Set world motorcycle land speed record

The motorcycle land-speed record is the fastest speed achieved by a motorcycle on land. It is standardized as the speed over a course of fixed length, averaged over two runs in opposite directions. AMA National Land Speed Records requires 2 passes ...

at in his V8 motorcycle in Ormond Beach, Florida

Ormond Beach is a city in central Florida in Volusia County. The population was 43,080 at the 2020 census. Ormond Beach lies directly north of Daytona Beach and is a principal city of the Deltona–Daytona Beach–Ormond Beach, FL Metropolita ...

*1908 First Army dirigible flight with Curtiss as flight engineer

*1908 One of several claimants for the first flight of a powered aircraft controlled by ailerons (manned glider flights with ailerons having been accomplished in 1904, unmanned flights even earlier)Parkin, John H''Bell and Baldwin: Their Development of Aerodromes and Hydrodromes at Baddeck, Nova Scotia''

Toronto:

University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press founded in 1901. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university cale ...

, 1964, pg. 65.Ransom, Sylvia and Jeff, James. Bibb County, Georgia, U.S.: Bibb County School District. April 2002, pp. 106-107.

*1908 Lead designer and pilot of " June Bug" on July 4

*1909 Sale of Curtiss's "Golden Flyer" to the New York Aeronautic Society for US$5,000.00, marks the first sale of any aircraft in the U.S., triggers Wright Brothers lawsuits.

*1909 Won first international air speed record with in Rheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

*1909 First U.S. licensed aircraft manufacturer.

*1909 Established first flying school in United States and exhibition company

*1910 Long distance flying record of from Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York C ...

to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

*1910 First simulated bombing runs from an aircraft at Keuka Lake

*1910 First firearm use from aircraft, piloted by Curtiss

*1910 First radio communication with aircraft in flight in a Curtiss biplane

*1910 Curtiss moved to California and set up a shop and flight school at the Los Angeles Motordrome

The Los Angeles Motordrome was a circular wood board race track. It was located in Playa del Rey, California, and opened in 1910. In addition to automobile racing, it was used for motorcycle competition and aviation activities.

The Motordr ...

, using the facility for sea plane experiments

*1910 Trained Blanche Stuart Scott, the first American female pilot

*1910 First successful takeoff from a United States Navy ship (Eugene Burton Ely

Eugene Burton Ely (October 21, 1886 – October 19, 1911) was an American aviation pioneer, credited with the first shipboard aircraft take off and landing.

Background

Ely was born in Williamsburg, Iowa, and raised in Davenport, Iowa. Having ...

, using Curtiss Plane)

*1911 First landing on a ship (Eugene Burton Ely, using Curtiss Plane) (2 Months later)

*1911 The Curtiss School of Aviation, established at Rockwell Field

Rockwell Field is a former United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) military airfield, located northwest of the city of Coronado, California, on the northern part of the Coronado Peninsula across the bay from San Diego, California.

This airfield ...

in February

*1914 Curtiss made a few short flights in the

*1914 Curtiss made a few short flights in the Langley Aerodrome

The Langley Aerodrome was a pioneering but unsuccessful manned, tandem wing-configuration powered flying machine, designed at the close of the 19th century by Smithsonian Institution Secretary Samuel Langley. The U.S. Army paid $50,000 for the p ...

, as part of an unsuccessful attempt to bypass the Wright Brothers' patent on aircraft

*1915 Start production run of "Jennys" and many other models including flying boats

*1915 Curtiss started the Atlantic Coast Aeronautical Station

A Curtiss Jenny on a training flight

Curtiss Flying School at North Beach California in 1911

The Curtiss Flying School was started by Glenn Curtiss to compete against the Wright Flying School of the Wright brothers. The first example was locat ...

on a 20-acre tract east of Newport News (VA) Boat Harbor in the Fall of 1915 with Captain Thomas Scott Baldwin

Thomas Scott Baldwin (June 30, 1854 – May 17, 1923) was a pioneer balloonist and U.S. Army major during World War I. He was the first American to descend from a balloon by parachute.

Early career

Thomas Scott Baldwin was born on June 30, 18 ...

as head.

*1917 Opens "Experimental Airplane Factory" in Garden City, Long Island

*1919 Curtiss NC-4 flying boat crosses the Atlantic

*1919 Commenced private aircraft production with the Oriole

*1921 Developed Hialeah, Florida

Hialeah ( ; ) is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. With a population of 223,109 as of the 2020 census, Hialeah is the sixth-largest city in Florida. It is the second largest city by population in the Miami metropolitan area

...

, including Hialeah Park Race Track

*1921 Donated his World War I training field to the Navy

*1922 Opened Hialeah Park Race Track

The Hialeah Park Race Track (also known as the Hialeah Race Track or Hialeah Park) is a historic racetrack in Hialeah, Florida. Its site covers 40 square blocks of central-east side Hialeah from Palm Avenue east to East 4th Avenue, and from East ...

with his business partner James H. Bright

*1923 Developed Miami Springs, Florida

Miami Springs is a city located in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The city was founded by Glenn Hammond Curtiss, "The Father of Naval Aviation", and James Bright, during the famous "land boom" of the 1920s and was originally named Country Club Estat ...

and created a flying school and airport

*1923 (circa) Created first airboats

*1925 Built his Miami Springs mansion

*1926 Developed

*1923 (circa) Created first airboats

*1925 Built his Miami Springs mansion

*1926 Developed Opa-locka, Florida

Opa-locka is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 16,463, up from 15,219 in 2010. The city was developed by Glenn Curtiss. Developed based on a ''One Thousand and One Nights'' theme, Op ...

and airport facility

*1928 Created the Curtiss Aerocar Company in Opa-locka, Florida.House 2003, p. 213.

*1928 Curtiss towed an Aerocar from Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

in 39 hours

*1930 Death in Buffalo, New York

*1930 Buried in Pleasant Valley Cemetery in Hammondsport, New York

*1964 Inducted in the National Aviation Hall of Fame

The National Aviation Hall of Fame (NAHF) is a museum, annual awards ceremony and learning and research center that was founded in 1962 as an Ohio non-profit corporation in Dayton, Ohio, United States, known as the "Birthplace of Aviation" with it ...

*1990 Inducted in the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America

The Motorsports Hall of Fame of America (MSHFA) is hall of fame that honors motorsports competitors and contributors from the United States from all disciplines, with categories for Open Wheel, Stock Cars, Powerboats, Drag Racing, Motorcycles, ...

in the air-racing category

See also

* Charles M. Olmsted *American Trans-Oceanic Company

American Trans-Oceanic Company was an airline based in the United States.

History

Rodman Wanamaker published a letter in 1916 stating the founding of the American Trans-Oceanic Company to capitalize on the 1914 effort to fly across the Atlan ...

*Curtiss Model T

The Wanamaker Triplane or Curtiss Model T, retroactively renamed Curtiss Model 3 was a large experimental four-engined triplane patrol flying boat of World War I. It was the first four-engined aircraft built in the United States. Only a single ...

*Curtiss Autoplane

The Curtiss Autoplane, invented by Glenn Curtiss in 1917, is widely considered the first attempt to build a roadable aircraft. Although the vehicle was capable of lifting off the ground, it never achieved full flight.

Development and design

The ...

*Schneider Trophy

The Coupe d'Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, also known as the Schneider Trophy, Schneider Prize or (incorrectly) the Schneider Cup is a trophy that was awarded annually (and later, biennially) to the winner of a race for seaplanes and flyin ...

*Curtiss & Bright Curtiss & Bright were developers in the Florida cities of Hialeah, Miami Springs and Opa-locka.

Aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss formed many corporations; "Curtiss & Bright" refers to the partnership between Curtiss and James Bright.

A number of ...

*Opa-locka Company

The Opa-locka Thematic Resource Area is a group of thematically-related historic sites in Opa-locka, Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. The area comprises 20 surviving Moorish Revival buildings which are listed on the National Registe ...

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

"At Dayton"

''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'', October 13, 1924.

* Casey, Louis S. ''Curtiss: The Hammondsport Era, 1907–1915''. New York: Crown Publishers, 1981. .

* Curtiss, Glenn and Augustus Post. ''The Curtiss Aviation Book''. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1912.

* de Cet, Mirco''The Illustrated Directory of Motorcycles''.

St. Paul: Minnesota: MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company, 2002. . * Dizer, John T. ''Tom Swift & Company''. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 1982. . * FitzGerald-Bush, Frank S. ''A Dream of Araby: Glenn Curtiss and the Founding of Opa-locka''. Opa-locka, Florida: South Florida Archaeological Museum, 1976. * Harvey, Steve. ''It Started with a Steamboat: An American Saga''. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2005. . * Hatch, Alden. ''Glenn Curtiss: Pioneer of Aviation''. Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2007. . * House, Kirk W. ''Hell-Rider to King of the Air''. Warrendale, Pennsylvania: SAE International, 2003. . * Mitchell, Charles R. and Kirk W. House. ''Glenn H. Curtiss: Aviation Pioneer''. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001. . * Roseberry, C.R. ''Glenn Curtiss: Pioneer of Flight''. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1972. . * Shulman, Seth. ''Unlocking the Sky: Glenn Hammond Curtiss and the Race to Invent the Airplane''. New York:

HarperCollins

HarperCollins Publishers LLC is one of the Big Five English-language publishing companies, alongside Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Macmillan. The company is headquartered in New York City and is a subsidiary of News ...

, 2002. .

"Speed Limit"

''Time'', October 29, 1923. * Studer, Clara. ''Sky Storming Yankee: The Life of Glenn Curtiss''. New York: Stackpole Sons, 1937. * Trimble, William F. ''Hero of the Air: Glenn Curtiss and the Birth of Naval Aviation''. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2010. .

External links

Glenn Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, NY

National Aviation Hall of Fame: Glenn Curtiss

Retrieved May 26, 2011 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Curtiss, Glenn 1878 births 1930 deaths 19th-century American inventors 20th-century American inventors Aircraft designers Alexander Graham Bell American aerospace engineers American aviation record holders American male cyclists American motorcycle designers Aviation history of the United States Aviation pioneers Aviators from New York (state) Bicycle messengers Collier Trophy recipients Deaths from appendicitis International Motorsports Hall of Fame inductees Members of the Early Birds of Aviation Motorcycle land speed record people National Aviation Hall of Fame inductees People from Hammondsport, New York Cyclists from New York (state)