Giosafat Barbaro on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Giosafat Barbaro (also Giosaphat or Josaphat) (1413–1494) was a member of the Venetian Barbaro family. He was a diplomat, merchant, explorer and travel writer.''A new general biographical dictionary, Volume 3''

Michela Marangoni, Manlio Pastore Stocchi, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 1996, pg. 120,

Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.39 He became a member of the

Roma, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg. 140 In 1434, he married Nona Duodo, daughter of Arsenio Duodo. Giosafat and Nona had three daughters and a son, Giovanni Antonio.

From 1436 to 1452 Barbaro traveled as a merchant to

From 1436 to 1452 Barbaro traveled as a merchant to

J Fr Michaud; Louis Gabriel Michaud, Paris, Michaud, 1811-28., pg. 327 During this time the

Neal Ascherson, New York, Hill and Wang, 1996, pg. 128, ''Venice & antiquity: the Venetian sense of the past''

Patricia Fortini Brown, New Haven, Conn. ; London : Yale University Press, 1996, pg. 152, Barbaro and six other men, a mix of Venetian and Jewish merchants, hired 120 men to excavate the

Neal Ascherson, New York, Hill and Wang, 1996, pg. 129, The remains of Barbaro's excavation was found in the 1920s by Russian archeologist Alexander Alexandrovich Miller. In 1438, the

Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.319 Later, Barbaro was part of a group that drove off a hundred Circassian raiders. Barbaro visited many cities in the Crimea, including Solcati,

Roma, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg. 110 Giosafat Barbaro did not spend all of the years from 1436 to 1452 in

Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.41 In 1448, he was appointed

Roma, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg. 141 In 1455, Barbaro freed a pair of Tartar men he had found in

Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.44 In 1463, he was appointed

Vittorio Spreti, Arnaldo Forni, 1981, pg. 276 Provveditore Barbaro linked his forces with those of Dukagjini and Nicolo Moneta to form an auxiliary corps of 13,000 men which was sent to relieve the Second Siege of Krujë. After Skanderbeg's death, Barbaro returned to Venice again. In 1469, Giosafat Barbaro was made Provveditore of Scutari, in

Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.305 but he was unable to persuade Persia to attack the Turks.''The Cambridge history of Iran''

William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, New York : Cambridge University Press, 1986, p.377 The ruler of Persia, Uzun Hassan, sent his own envoys to Venice in return. After Negroponte fell to the Turks, Venice, Naples, the

Hugh Murray, Edinburgh, A. Constable and Co; 1820., p.10 He also spoke Turkish and a little Persian.''The Cambridge history of Iran''

William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, New York : Cambridge University Press, 1986, p.378 Barbaro was provided with an escort of ten men and an annual salary of 1800 ducats. His instructions included urging admiral

Nikos Kureas; International Conference Cyprus and the Crusades (1994, Leukosia), pg. 161 In February 1473, Barbaro and the Persian envoy Haci Muhammad left Venice and traveled to The

The

Sir George Francis Hill, Cambridge University Press, 1952, pg. 623 King James had also written to the Venetian Senate, stressing the need to support Persia against the Turks and his navy had cooperated with Admiral Mocenigo in recapturing the coastal towns of Gorhigos and

Sir George Francis Hill, Cambridge University Press, 1952, pg. 624 The Emir of Scandelore fell to the Turks in 1473 in spite of military aid from the Kingdom of Cyprus. The power of Caramania was broken. James II of Cyprus privately told Giosafat Barbaro he felt like he was trapped between two wolves, the Ottoman Sultan and the Egyptian Sultan. The latter was James' liege lord, and not on friendly terms with Venice.''A history of Cyprus, Volume 3''

Sir George Francis Hill, Cambridge University Press, 1952, pg. 626 James II entered into negotiations with the Turks. At first he refused to let the Venetian galleys with their munitions land in the port of

Horatio Forbes Brown, London, K. Paul, Trench & Co, 1887, p.312 Once the Venetian fleet left, there was a revolt by pro-Neapolitan forces, which resulted in the deaths of the Queen's uncle and cousin.''Venetian studies''

Horatio Forbes Brown, London, K. Paul, Trench & Co, 1887, p.377 The

Horatio Forbes Brown, London, K. Paul, Trench & Co, 1887, p.313 Later, Barbaro and the Venetian troops withdrew to one of the galleys. By the time Admiral Mocenigo returned to Cyprus, the rebels were quarreling among themselves and the people of

Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.321 Barbaro and the Persian envoy left Cyprus in February 1474 disguised as Muslim pilgrims.''Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia''

Rome, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg.142 The Papal and Neapolitan envoys did not accompany them.''Mehmed the Conqueror & His Time''

Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.326 Barbaro landed in In the

In the

Hugh Murray, Edinburgh, A. Constable and Co; 1820., p.12 As they neared

M. Th. Houtsma, New York, 1993., pg. 1067 Although Barbaro got on well with Uzun Hassan, he was unable to persuade the ruler to attack the Ottomans again. Shortly afterwards, Hassan's son Ogurlu Mohamed, rose in rebellion, seizing the city of Schiras.''Historical account of discoveries and travels in Asia''

Hugh Murray, Edinburgh, A. Constable and Co; 1820., p.15 Barbaro visited the ruins of

Barbaro visited the ruins of

Patricia Fortini Brown, New Haven, Conn. ; London : Yale University Press, 1996, pg. 156, He also visited Tauris, Soldania, Isph, Cassan (Kascian), The other Venetian ambassador, Ambrosio Contarini, arrived in Persia in August 1474. Uzun Hassan decided that Contarini would return to Venice with a report, while Giosafat Barbaro would stay in Persia.

The other Venetian ambassador, Ambrosio Contarini, arrived in Persia in August 1474. Uzun Hassan decided that Contarini would return to Venice with a report, while Giosafat Barbaro would stay in Persia.

Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.322 By this point only one of Barbaro's entourage was left. While Hassan's sons fought each other for the throne, Barbaro hired an Armenian guide and escaped by way of

Roma, Societá geografica italiana; 1882, pg.143 Barbaro reached Venice in 1479, where he defended himself against complaints that he had spent too much time in Cyprus before going to Persia. Barbaro's report included not just political and military matters, but discussed Persian agriculture, commerce, and customs. Giosafat Barbaro served as Captain of

Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.45 He was also one of the Councilors of Doge

Roma, Societá geografica italiana; 1882, pg.144

Hugh James Rose

Hugh James Rose (1795–1838) was an English Anglican priest and theologian who served as the second Principal of King's College, London.

Life

Rose was born at Little Horsted in Sussex on 9 June 1795 and educated at Uckfield School, where his fa ...

, Henry John Rose

Henry John Rose (3 January 1800 – 31 January 1873) was an English churchman, theologian of High Church views, and scholar who became archdeacon of Bedford.

Life

Born at Uckfield, Sussex, he was a younger son of William Rose (1763–1844), th ...

, 1857, pg. 137 He was unusually well-travelled for someone of his times.''Una famiglia veneziana nella storia: i Barbaro''Michela Marangoni, Manlio Pastore Stocchi, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 1996, pg. 120,

Family

Giosafat Barbaro was born to Antonio and Franceschina Barbaro in apalazzo

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome which ...

on the Campo di Santa Maria Formosa.''Die persische Karte : venezianisch-persische Beziehungen um 1500 ; Reiseberichte venezianischer Persienreisender''Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.39 He became a member of the

Venetian Senate

The Senate ( vec, Senato), formally the ''Consiglio dei Pregadi'' or ''Rogati'' (, la, Consilium Rogatorum), was the main deliberative and legislative body of the Republic of Venice.

Establishment

The Venetian Senate was founded in 1229, or le ...

in 1431.''Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia''Roma, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg. 140 In 1434, he married Nona Duodo, daughter of Arsenio Duodo. Giosafat and Nona had three daughters and a son, Giovanni Antonio.

Travels to Tana

From 1436 to 1452 Barbaro traveled as a merchant to

From 1436 to 1452 Barbaro traveled as a merchant to Tana Tana may refer to:

Places

Africa

* Lake Tana, a lake in Ethiopia (and a source of the Nile River)

* Tana Qirqos, an island in the eastern part of Lake Tana in Ethiopia, near the mouth of the Gumara River

* Tana River County, a county of Coast P ...

on the Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Ker ...

.''Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne''J Fr Michaud; Louis Gabriel Michaud, Paris, Michaud, 1811-28., pg. 327 During this time the

Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragmen ...

was disintegrating due to political rivalries.

In November 1437, Barbaro heard of the burial mound of the last King of the Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

, about 20 miles up the Don River

The Don ( rus, Дон, p=don) is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its ...

from Tana.''Black Sea''Neal Ascherson, New York, Hill and Wang, 1996, pg. 128, ''Venice & antiquity: the Venetian sense of the past''

Patricia Fortini Brown, New Haven, Conn. ; London : Yale University Press, 1996, pg. 152, Barbaro and six other men, a mix of Venetian and Jewish merchants, hired 120 men to excavate the

kurgan

A kurgan is a type of tumulus constructed over a grave, often characterized by containing a single human body along with grave vessels, weapons and horses. Originally in use on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, kurgans spread into much of Central As ...

, which they hoped would contain treasure. When the weather proved too severe, they returned in March 1438, but found no treasure. Barbaro analytically and precisely recorded information about the layers of earth, coal, ashes, millet, and fish scales that composed the mound. Modern scholarship concludes that it was not a burial mound, but a kitchen midden

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and eco ...

that had accumulated over centuries of use.''Black Sea''Neal Ascherson, New York, Hill and Wang, 1996, pg. 129, The remains of Barbaro's excavation was found in the 1920s by Russian archeologist Alexander Alexandrovich Miller. In 1438, the

Great Horde

The Great Horde (''Uluğ Orda'') was a rump state of the Golden Horde that existed from the mid-15th century to 1502. It was centered at the core of the Golden Horde at Sarai. Both the Khanate of Astrakhan and the Khanate of Crimea broke away ...

under Küchük Muhammad

Küchük Muḥammad or Kīchīk Muḥammad (; 28 June 1391 – 1459) was a Mongol Khan of the Golden Horde from 1433 until his death in 1459. He was the son of Tīmūr Khan, possibly by a daughter of the powerful beglerbeg Edigu. His name, "L ...

advanced on Tana. Barbaro went as an emissary to the Tatars to persuade them not to attack Tana.''Mehmed the Conqueror & His Time''Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.319 Later, Barbaro was part of a group that drove off a hundred Circassian raiders. Barbaro visited many cities in the Crimea, including Solcati,

Soldaia

Sudak (Ukrainian & Russian: Судак; crh, Sudaq; gr, Σουγδαία; sometimes spelled Sudac or Sudagh) is a town, multiple former Eastern Orthodox bishopric and double Latin Catholic titular see. It is of regional significance in Crimea, ...

, Cembalo, and Caffa

uk, Феодосія, Теодосія crh, Kefe

, official_name = ()

, settlement_type=

, image_skyline = THEODOSIA 01.jpg

, imagesize = 250px

, image_caption = Genoese fortress of Caffa

, image_shield = Fe ...

. Barbaro also traveled to Russia where he visited Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: Help:IPA/Tatar, ɑzan is the capital city, capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and t ...

(Casan) and Novogorod, "which had already come under the power of the Muscovites" (che gia era venuta in potere de'Moscoviti).''Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia''Roma, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg. 110 Giosafat Barbaro did not spend all of the years from 1436 to 1452 in

Tartary

Tartary ( la, Tartaria, french: Tartarie, german: Tartarei, russian: Тартария, Tartariya) or Tatary (russian: Татария, Tatariya) was a blanket term used in Western European literature and cartography for a vast part of Asia bound ...

In 1446, he was elected to the Council of Forty The Council of Forty ( it, Consiglio dei Quaranta), also known as the ''Quarantia'', was one of the highest constitutional bodies of the Republic of Venice, with both legal and political functions as the supreme court.

Origins and evolution

By some ...

.''Die persische Karte : venezianisch-persische Beziehungen um 1500 ; Reiseberichte venezianischer Persienreisender''Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.41 In 1448, he was appointed

Provveditore The Italian title ''prov ditore'' (plural ''provveditori''; also known in gr, προνοητής, προβλεπτής; sh, providur), "he who sees to things" (overseer), was the style of various (but not all) local district governors in the exten ...

of the trading colonies Modon The Saudi Authority for Industrial Cities and Technology Zones ( ar, الهيئة السعودية للمدن الصناعية ومناطق التقنية), also known simply as MODON ( ar, مُدُن) is a government organization created by the Go ...

and Corone

Corone ( grc, Κορώνη, Korṓnē, crow) may refer to:

* Koroni, also spelled Corone, a town in Greece

* Corone (crow)

In Greek and Roman mythology, Corone ( grc, Κορώνη, Korṓnē, crow ) is a young woman who attracted the atten ...

in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

and served until his resignation the following year. Since there was regular trade between Venice and Tana at this time, it seems likely Barbaro went to Tana to trade and returned to Venice for the winter over this time. Barbaro stopped these travels when the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the long ...

became a client state of the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

. Barbaro returned to Venice in 1452, traveling by way of Russia, Poland, and Germany.''Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia''Roma, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg. 141 In 1455, Barbaro freed a pair of Tartar men he had found in

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, housed them for two months, and sent them home to Tana.

Political career

In 1460, Giosafat Barbaro was elected Council to Tana, but he declined the position.''Die persische Karte : venezianisch-persische Beziehungen um 1500 ; Reiseberichte venezianischer Persienreisender''Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.44 In 1463, he was appointed

Provveditore The Italian title ''prov ditore'' (plural ''provveditori''; also known in gr, προνοητής, προβλεπτής; sh, providur), "he who sees to things" (overseer), was the style of various (but not all) local district governors in the exten ...

of Albania. While there, Barbaro he fought with Lekë Dukagjini

Lekë III Dukagjini (1410–1481), mostly known as Lekë Dukagjini, was a 15th-century member of the Albanian nobility, from the Dukagjini family. A contemporary of Skanderbeg, Dukagjini is known for the ''Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit'', a code of ...

and Skanderbeg

, reign = 28 November 1443 – 17 January 1468

, predecessor = Gjon Kastrioti

, successor = Gjon Kastrioti II

, spouse = Donika Arianiti

, issue = Gjon Kastrioti II

, royal house = Kastrioti

, father ...

against the Turks.''Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare italiana, Volume 7''Vittorio Spreti, Arnaldo Forni, 1981, pg. 276 Provveditore Barbaro linked his forces with those of Dukagjini and Nicolo Moneta to form an auxiliary corps of 13,000 men which was sent to relieve the Second Siege of Krujë. After Skanderbeg's death, Barbaro returned to Venice again. In 1469, Giosafat Barbaro was made Provveditore of Scutari, in

Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and share ...

. He was in command of 1200 cavalry, which he used to support Lekë Dukagjini

Lekë III Dukagjini (1410–1481), mostly known as Lekë Dukagjini, was a 15th-century member of the Albanian nobility, from the Dukagjini family. A contemporary of Skanderbeg, Dukagjini is known for the ''Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit'', a code of ...

. In 1472, Barbaro was back in Venice, where he was one of the 41 senators chosen to act as electors, who selected Nicolo Tron as Doge.

Venetian conflict with the Ottoman Turks

In 1463, the Venetian Senate, seeking allies against theTurks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

, had sent Lazzaro Querini as its first ambassador to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

,''Mehmed the Conqueror & His Time''Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.305 but he was unable to persuade Persia to attack the Turks.''The Cambridge history of Iran''

William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, New York : Cambridge University Press, 1986, p.377 The ruler of Persia, Uzun Hassan, sent his own envoys to Venice in return. After Negroponte fell to the Turks, Venice, Naples, the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, the Kingdom of Cyprus

The Kingdom of Cyprus (french: Royaume de Chypre, la, Regnum Cypri) was a state that existed between 1192 and 1489. It was ruled by the French House of Lusignan. It comprised not only the island of Cyprus, but it also had a foothold on the Ana ...

and the Knights of Rhodes

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

signed an agreement to ally against the Turks.

In 1471, ambassador Querini returned to Venice with Uzun Hassan's ambassador Murad. The Venetian Senate voted to send another ambassador to Persia, choosing Caterino Zeno

Mario Caterino (; born June 14, 1957 in Casal di Principe) is an Italian Camorrista and member in the Casalesi clan from Casal di Principe in the province of Caserta between Naples and Salerno. He was on the "most wanted list" of the Italian m ...

after two other men declined. Zeno, whose wife was the niece of Uzun Hassan's wife, was able to persuade Hassan to attack the Turks. Hassan was successful at first, but there were no simultaneous attacks by any of the western powers and the war turned against Persia.

Ambassador to Persia

In 1472, Giosafat Barbaro was also selected as an ambassador to Persia, due to his experience in the Crimean, Muscovy, andTartary

Tartary ( la, Tartaria, french: Tartarie, german: Tartarei, russian: Тартария, Tartariya) or Tatary (russian: Татария, Tatariya) was a blanket term used in Western European literature and cartography for a vast part of Asia bound ...

.''Historical account of discoveries and travels in Asia''Hugh Murray, Edinburgh, A. Constable and Co; 1820., p.10 He also spoke Turkish and a little Persian.''The Cambridge history of Iran''

William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, New York : Cambridge University Press, 1986, p.378 Barbaro was provided with an escort of ten men and an annual salary of 1800 ducats. His instructions included urging admiral

Pietro Mocenigo

Pietro Mocenigo (1406–1476) was doge of Venice from 1474 to 1476.

He was one of the greatest Venetian admirals and revived the fortunes of the Venetian navy, which had fallen very low after the defeat at the Battle of Negroponte in 1470. In 1 ...

to attack the Ottomans and attempting to arrange naval cooperation from the Kingdom of Cyprus

The Kingdom of Cyprus (french: Royaume de Chypre, la, Regnum Cypri) was a state that existed between 1192 and 1489. It was ruled by the French House of Lusignan. It comprised not only the island of Cyprus, but it also had a foothold on the Ana ...

and the Knights of Rhodes

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

. He was also in charge of three galleys full of artillery, ammunition, and military personnel who were to assist Uzun Hassan.''He Kypros kai hoi Staurophories''Nikos Kureas; International Conference Cyprus and the Crusades (1994, Leukosia), pg. 161 In February 1473, Barbaro and the Persian envoy Haci Muhammad left Venice and traveled to

Zadar

Zadar ( , ; historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian: ); see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited Croatian city. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ser ...

, where they met with representatives of Naples and the Papal court. From there, Barbaro and the others traveled by way of Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

, Modon The Saudi Authority for Industrial Cities and Technology Zones ( ar, الهيئة السعودية للمدن الصناعية ومناطق التقنية), also known simply as MODON ( ar, مُدُن) is a government organization created by the Go ...

, Corone

Corone ( grc, Κορώνη, Korṓnē, crow) may refer to:

* Koroni, also spelled Corone, a town in Greece

* Corone (crow)

In Greek and Roman mythology, Corone ( grc, Κορώνη, Korṓnē, crow ) is a young woman who attracted the atten ...

reaching Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

and then Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, where Barbaro was delayed for a year.

Kingdom of Cyprus

The Kingdom of Cyprus (french: Royaume de Chypre, la, Regnum Cypri) was a state that existed between 1192 and 1489. It was ruled by the French House of Lusignan. It comprised not only the island of Cyprus, but it also had a foothold on the Ana ...

's position off the coast of Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

was in a key position for supplying, not just Uzun Hassan in Persia, but the Venetian allies of Caramania In the 18th and 19th centuries, Karamania (or Caramania) was an exonym used by Europeans for the southern (Mediterranean) coast of Anatolia, then part of the Ottoman Empire (current Turkey). It can also refer to the general south central Anatolian r ...

and Scandelore (present day Alanya) and the Venetian fleet under Pietro Mocenigo

Pietro Mocenigo (1406–1476) was doge of Venice from 1474 to 1476.

He was one of the greatest Venetian admirals and revived the fortunes of the Venetian navy, which had fallen very low after the defeat at the Battle of Negroponte in 1470. In 1 ...

was used to defend communication lines to them. King James II of Cyprus

James II (french: Jacques; c. 1438/1439 or c. 1440 – 10 July 1473) was the penultimate King of Cyprus (usurper), reigning from 1463 until his death.

Archbishop of Nicosia

James was born in Nicosia as the illegitimate son of John II of Cypru ...

had attempted to ally with Caramania and Scandelore, as well as the Sultan of Egypt, against the Turks.''A history of Cyprus, Volume 3''Sir George Francis Hill, Cambridge University Press, 1952, pg. 623 King James had also written to the Venetian Senate, stressing the need to support Persia against the Turks and his navy had cooperated with Admiral Mocenigo in recapturing the coastal towns of Gorhigos and

Selefke

Silifke ( grc-gre, Σελεύκεια, ''Seleukeia'', la, Seleucia ad Calycadnum) is a town and district in south-central Mersin Province, Turkey, west of the city of Mersin, on the west end of Çukurova.

Silifke is near the Mediterranean coast ...

.''A history of Cyprus, Volume 3''Sir George Francis Hill, Cambridge University Press, 1952, pg. 624 The Emir of Scandelore fell to the Turks in 1473 in spite of military aid from the Kingdom of Cyprus. The power of Caramania was broken. James II of Cyprus privately told Giosafat Barbaro he felt like he was trapped between two wolves, the Ottoman Sultan and the Egyptian Sultan. The latter was James' liege lord, and not on friendly terms with Venice.''A history of Cyprus, Volume 3''

Sir George Francis Hill, Cambridge University Press, 1952, pg. 626 James II entered into negotiations with the Turks. At first he refused to let the Venetian galleys with their munitions land in the port of

Famagusta

Famagusta ( , ; el, Αμμόχωστος, Ammóchostos, ; tr, Gazimağusa or ) is a city on the east coast of Cyprus. It is located east of Nicosia and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the Middle Ages (especially under t ...

. When Barbaro and the Venetian ambassador, Nicolo Pasqualigo, attempted to persuade James II to change his mind, the King threatened to destroy the galleys and kill every man on board.

King James II of Cyprus

James II (french: Jacques; c. 1438/1439 or c. 1440 – 10 July 1473) was the penultimate King of Cyprus (usurper), reigning from 1463 until his death.

Archbishop of Nicosia

James was born in Nicosia as the illegitimate son of John II of Cypru ...

died in July 1473, leaving Queen Catherine a pregnant widow. James had appointed a seven-member council, which contained Venetian Andrea Cornaro, a relative of the Queen, as well as Marin Rizzo and Giovanni Fabrice, agents of the Kingdom of Naples who opposed Venetian influence. Queen Catherine gave birth to a son, James II in August 1473., with Admiral Pietro Mocenigo and other Venetian officials acting as godfathers.''Venetian studies''Horatio Forbes Brown, London, K. Paul, Trench & Co, 1887, p.312 Once the Venetian fleet left, there was a revolt by pro-Neapolitan forces, which resulted in the deaths of the Queen's uncle and cousin.''Venetian studies''

Horatio Forbes Brown, London, K. Paul, Trench & Co, 1887, p.377 The

Archbishop of Nicosia

The Latin Catholic archdiocese of Nicosia was created during the Crusades (1095-1487) in Cyprus; later becoming titular. According to the ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' 31 Latin archbishops served beginning in 1196, shortly after the conquest of Cypru ...

, Juan Tafures, the Count of Tripoli

The count of Tripoli was the ruler of the County of Tripoli, a crusader state from 1102 through 1289. Of the four major crusader states in the Levant, Tripoli was created last.

The history of the counts of Tripoli began with Raymond IV of Toulo ...

, the Count of Jaffa, and Marin Rizzo seized Famagusta, capturing the Queen and the newborn King.

Barbaro and Bailo Pasqualigo were protected by the Venetian soldiers that had accompanied Barbaro. The conspirators made several attempts to persuade Barbaro to hand over the soldiers' arms. The Constable of Cyprus sent an agent, while the Count of Tripoli, the Archbishop of Nicosia, and the Constable of Jerusalem made personal visits. After consulting with Bailo Pasqualigo, they decided to disarm the men, but keep the weapons. Barbaro alerted the captains of the Venetian galleys in the harbor. Barbaro also sent dispatches the Senate of Venice, warning them of events.''Venetian studies''Horatio Forbes Brown, London, K. Paul, Trench & Co, 1887, p.313 Later, Barbaro and the Venetian troops withdrew to one of the galleys. By the time Admiral Mocenigo returned to Cyprus, the rebels were quarreling among themselves and the people of

Nicosia

Nicosia ( ; el, Λευκωσία, Lefkosía ; tr, Lefkoşa ; hy, Նիկոսիա, romanized: ''Nikosia''; Cypriot Arabic: Nikusiya) is the largest city, capital, and seat of government of Cyprus. It is located near the centre of the Mesaori ...

and Famagusta

Famagusta ( , ; el, Αμμόχωστος, Ammóchostos, ; tr, Gazimağusa or ) is a city on the east coast of Cyprus. It is located east of Nicosia and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the Middle Ages (especially under t ...

had risen against them. The uprising was suppressed, those ringleaders who did not flee were executed, and Cyprus became a Venetian client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite sta ...

. The Venetian Senate authorized the troops and military that had accompanied Giosafat Barbaro to stay in Cyprus.

Giosafat Barbaro was still in Cyprus in December 1473, and the Venetian Senate sent a letter, telling Barbaro to complete his journey, as well as sending another ambassador, Ambrogio Contarini Ambrogio Contarini (1429 – 1499) was a Venetian nobleman, merchant and diplomat known for an account of his travel to Iran.Bertotti, Filippo (1992), "Contarini, Ambrogio", in: ''Encyclopædia Iranica'', Vol. VI, Fasc. 2, p. 220Online (Accessed Fe ...

to Persia.''Mehmed the Conqueror & His Time''Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.321 Barbaro and the Persian envoy left Cyprus in February 1474 disguised as Muslim pilgrims.''Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia''

Rome, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg.142 The Papal and Neapolitan envoys did not accompany them.''Mehmed the Conqueror & His Time''

Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.326 Barbaro landed in

Caramania In the 18th and 19th centuries, Karamania (or Caramania) was an exonym used by Europeans for the southern (Mediterranean) coast of Anatolia, then part of the Ottoman Empire (current Turkey). It can also refer to the general south central Anatolian r ...

, where the King warned them that the Turks held the territory they would need to travel through. After landing in Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern co ...

, Barbaro's party traveled through Tarsus, Adana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, wh ...

, Orfa, Merdin, Hasankeyf

Hasankeyf ( ar, حصن كيفا, translit=Ḥiṣn Kayfa‘, ku, Heskîf, hy, Հասանքեյֆ, translit=, el, Κιφας, translit=Kifas, lat, Cepha, syr, ܚܣܢܐ ܕܟܐܦܐ, Ḥesno d-Kifo) is a town and district located along the Ti ...

, and Tigranocerta __NOTOC__

Tigranocerta ( el, Τιγρανόκερτα, ''Tigranόkerta''; Tigranakert; hy, Տիգրանակերտ), also called Cholimma or Chlomaron in antiquity, was a city and the capital of the Armenian Kingdom between 77 and 69 BCE. It bore ...

In the

In the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

of Kurdistan

Kurdistan ( ku, کوردستان ,Kurdistan ; lit. "land of the Kurds") or Greater Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural territory in Western Asia wherein the Kurds form a prominent majority population and the Kurdish culture, languag ...

, Barbaro's party was attacked by bandits. He escaped on horseback, but he was wounded and several members of the group, including his secretary and the Persian ambassador were killed, and their goods were plundered.''Historical account of discoveries and travels in Asia''Hugh Murray, Edinburgh, A. Constable and Co; 1820., p.12 As they neared

Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quru River valley in Iran's historic Azerbaijan region between long ridges of vo ...

, Barbaro and his interpreter were assaulted by Turcomans

Turkoman (Middle Turkic: تُركْمانْ, ota, تركمن, Türkmen and ''Türkmân''; az, Türkman and ', tr, Türkmen, tk, Türkmen, Persian: ترکمن sing. ''Turkamān'', pl. ''Tarākimah''), also called Turcoman and Turkman, is a term ...

after refusing to hand over a letter to Uzun Hassan Barbaro and his surviving companions finally reached Hassan's court in April 1474.''E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam''M. Th. Houtsma, New York, 1993., pg. 1067 Although Barbaro got on well with Uzun Hassan, he was unable to persuade the ruler to attack the Ottomans again. Shortly afterwards, Hassan's son Ogurlu Mohamed, rose in rebellion, seizing the city of Schiras.''Historical account of discoveries and travels in Asia''

Hugh Murray, Edinburgh, A. Constable and Co; 1820., p.15

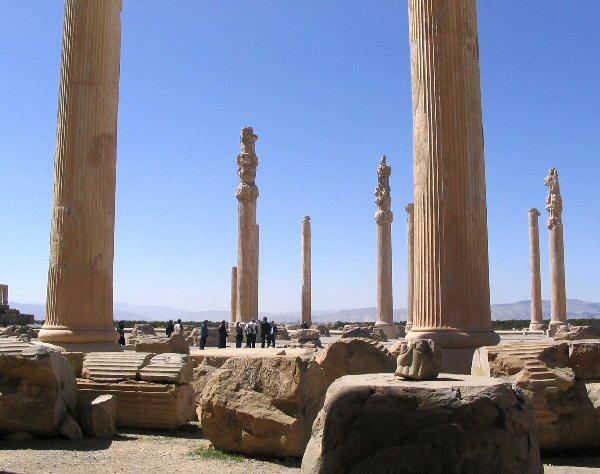

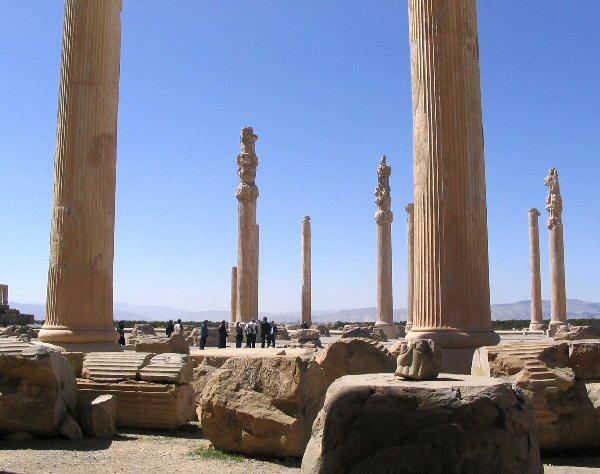

Barbaro visited the ruins of

Barbaro visited the ruins of Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

, which he incorrectly thought were of Jewish origin.''Venice & antiquity: the Venetian sense of the past''Patricia Fortini Brown, New Haven, Conn. ; London : Yale University Press, 1996, pg. 156, He also visited Tauris, Soldania, Isph, Cassan (Kascian),

Como

Como (, ; lmo, Còmm, label= Comasco , or ; lat, Novum Comum; rm, Com; french: Côme) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy. It is the administrative capital of the Province of Como.

Its proximity to Lake Como and to the Alps ...

(Kom), Yezd, Shiraz

Shiraz (; fa, شیراز, Širâz ) is the fifth-most-populous city of Iran and the capital of Fars Province, which has been historically known as Pars () and Persis. As of the 2016 national census, the population of the city was 1,565,572 p ...

and Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

. Giosafat Barbaro was the first European to visit the ruins of Pasargadae

Pasargadae (from Old Persian ''Pāθra-gadā'', "protective club" or "strong club"; Modern Persian: ''Pāsārgād'') was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great (559–530 BC), who ordered its construction and the locatio ...

, where he believed the local tradition that misidentified the tomb of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

as belonging to King Solomon

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ti ...

’s mother.  The other Venetian ambassador, Ambrosio Contarini, arrived in Persia in August 1474. Uzun Hassan decided that Contarini would return to Venice with a report, while Giosafat Barbaro would stay in Persia.

The other Venetian ambassador, Ambrosio Contarini, arrived in Persia in August 1474. Uzun Hassan decided that Contarini would return to Venice with a report, while Giosafat Barbaro would stay in Persia.

Return to Venice

Barbaro was the last Venetian ambassador to leave Persia, after Uzun Hassan died in 1478.''Mehmed the Conqueror & His Time''Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.322 By this point only one of Barbaro's entourage was left. While Hassan's sons fought each other for the throne, Barbaro hired an Armenian guide and escaped by way of

Erzerum

Erzurum (; ) is a city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses the double-headed eagle as ...

, Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

, and Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

.''Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia''Roma, Societá geografica italiana; 1882, pg.143 Barbaro reached Venice in 1479, where he defended himself against complaints that he had spent too much time in Cyprus before going to Persia. Barbaro's report included not just political and military matters, but discussed Persian agriculture, commerce, and customs. Giosafat Barbaro served as Captain of

Rovigo

Rovigo (, ; egl, Ruig) is a city and '' comune'' in the Veneto region of Northeast Italy, the capital of the eponymous province.

Geography

Rovigo stands on the low ground known as Polesine, by rail southwest of Venice and south-southwest ...

and Provveditore The Italian title ''prov ditore'' (plural ''provveditori''; also known in gr, προνοητής, προβλεπτής; sh, providur), "he who sees to things" (overseer), was the style of various (but not all) local district governors in the exten ...

of all Polesine

Polesine (; vec, label=unified Venetian script, Połéxine ) is a geographic and historic area in the north-east of Italy whose limits varied through centuries; it had also been known as Polesine of Rovigo for some time.

Nowadays it corresponds w ...

from 1482 to 1485.''Die persische Karte : venezianisch-persische Beziehungen um 1500 ; Reiseberichte venezianischer Persienreisender''Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.45 He was also one of the Councilors of Doge

Agostino Barbarigo

Agostino Barbarigo (3 June 1419 – 20 September 1501) was Doge of Venice from 1486 until his death in 1501.

While he was Doge, the imposing Clock Tower in the Piazza San Marco with its archway through which the street known as the Merceria le ...

He died in 1494 and was buried in the Church of San Francesco della Vigna

San Francesco della Vigna is a Roman Catholic church in the Sestiere of Castello in Venice, northern Italy.

History

Along with Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, this is one of two Franciscan churches in Venice. The site, originally a vineyard (''v ...

.''Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia''Roma, Societá geografica italiana; 1882, pg.144

Writing

In 1487, Barbaro wrote an account of his travels. In it, he mentions being familiar with the accounts of Niccolò de' Conti andJohn de Mandeville

Sir John Mandeville is the supposed author of ''The Travels of Sir John Mandeville'', a travel memoir which first circulated between 1357 and 1371. The earliest-surviving text is in French.

By aid of translations into many other languages, the ...

.

Barbaro's account of his travels, entitled "'' Viaggi fatti da Vinetia, alla Tana, in Persia''" was first published from 1543 to 1545 by the sons of Aldus Manutius

Aldus Pius Manutius (; it, Aldo Pio Manuzio; 6 February 1515) was an Italian printer and humanist who founded the Aldine Press. Manutius devoted the later part of his life to publishing and disseminating rare texts. His interest in and preser ...

. It is included Giovanne Baptista Ramusio's 1559 "''Collection of Travels''" as "''Journey to the Tanais, Persia, India, and Constantinople''" The scholar and courtier William Thomas translated this work into English for the young King Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

under the title ‘’Travels to Tana and Persia’’ and also includes the account of Barbaro’s fellow ambassador to Persia, Ambrogio Contarini Ambrogio Contarini (1429 – 1499) was a Venetian nobleman, merchant and diplomat known for an account of his travel to Iran.Bertotti, Filippo (1992), "Contarini, Ambrogio", in: ''Encyclopædia Iranica'', Vol. VI, Fasc. 2, p. 220Online (Accessed Fe ...

. This work was republished in London in 1873 by the Hakluyt Society

The Hakluyt Society is a text publication society, founded in 1846 and based in London, England, which publishes scholarly editions of primary records of historic voyages, travels and other geographical material. In addition to its publishing r ...

. and a Russian language edition was published in 1971. In 1583, Barbaro’s account was published by Filippo Giunti

The Giunti were a Florentine family of printers. The first Giunti press was established in Venice by Lucantonio Giunti, who began printing under his own name in 1489. The press of his brother Filippo Giunti (1450–1517) in Florence, active fr ...

in ‘’Volume Delle Navigationi Et Viaggi’’ along with those of Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

and Kirakos Gandzaketsi

Kirakos Gandzaketsi (; c. 1200/1202–1271) was an Armenian historian of the 13th century S. Peter Cowe. Kirakos Ganjakec'i or Arewelc'i // Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History / Edited by David Thomas & Alex Mallet. — BRILL, 2 ...

’s account of the travels of Hethum I, King of Armenia. In 1601, Barbaro’s and Contarini’s accounts were included in Pietro Bizzarri’s ‘’ Rerum Persicarum Historia’’ along with accounts by Bonacursius

Filippo Buonaccorsi, called Callimachus, Callimico, Bonacurarius, Caeculus, Geminianensis (Latin: ''Philippus Callimachus Experiens'', ''Bonacursius''; , 2 May 1437 – 1 November 1496) was an Italian humanist, writer and diplomat active in Po ...

, Jacob Geuder von Heroldsberg, Giovanni Tommaso Minadoi, and Henricus Porsius; which was published in Frankfurt. in 2005, Barbaro’s account was also published in Turkish as ‘’ Anadolu'ya ve İran'a seyahat’’.

Barbaro's account provided more information on Persia and its resources than that of Contarini. He showed skill in observing unfamiliar places and reporting on them. Much of Barbaro's information about the Kipchak Khanate

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragment ...

, Persia, and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

is not found in any other sources.

Giosafat Barbaro's dispatches to the Venetian Senate were compiled by Enrico Cornet and published as ''Lettere al Senato Veneto'' in 1852 in Vienna. Barbaro also discussed his travels in a letter written in 1491 to the Bishop of Padua

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Padua ( it, Diocesi di Padova; la, Dioecesis Patavina) is an episcopal see of the Catholic Church in Veneto, northern Italy. It was erected in the 3rd century.Pietro Barocci.

Travels of Josaphat Barbaro Ambassador from Venice to Tanna in 1436

{{DEFAULTSORT:Barbaro, Giosafat 1413 births 1494 deaths Explorers from the Republic of Venice Republic of Venice merchants Republic of Venice military personnel Italian travel writers 15th-century travel writers Italian male writers Republic of Venice nobility Giosafat Republic of Venice politicians Republic of Venice diplomats Medieval Italian diplomats Medieval travel writers Governors-general 15th-century Italian judges 15th-century diplomats 15th-century Italian businesspeople

In popular culture

He is one of the historical characters who appear inDorothy Dunnett

Dorothy, Lady Dunnett (née Halliday, 25 August 1923 – 9 November 2001) was a Scottish novelist best known for her historical fiction. Dunnett is most famous for her six novel series set during the 16th century, which concern the fictiti ...

's novel ''Caprice and Rondo'' in the House of Niccolò series.

In the game ''Civilization V

''Sid Meier's Civilization V'' is a 4X video game in the ''Civilization'' series developed by Firaxis Games. The game was released on Microsoft Windows on September 21, 2010, on OS X on November 23, 2010, and on Linux on June 10, 2014.

In ...

'' he is a great merchant for the Venetians.

Notes

References

External links

Travels of Josaphat Barbaro Ambassador from Venice to Tanna in 1436

{{DEFAULTSORT:Barbaro, Giosafat 1413 births 1494 deaths Explorers from the Republic of Venice Republic of Venice merchants Republic of Venice military personnel Italian travel writers 15th-century travel writers Italian male writers Republic of Venice nobility Giosafat Republic of Venice politicians Republic of Venice diplomats Medieval Italian diplomats Medieval travel writers Governors-general 15th-century Italian judges 15th-century diplomats 15th-century Italian businesspeople